1. Introduction

Hydrogels and microcapsules represent two especially robust “soft” (U ~ kT) platforms increasingly integrated into fiber-based materials for advanced functionality, responsiveness, biocompatibility, sustainability, and biodegradability. Hydrogels are three-dimensional polymer motifs which can absorb and retain significant amounts of water (superhydrogels can absorb even 100s-1000x their mass), which endow them with the superior capacity for applications requiring moisture control, potential biocompatibility (due to “soft” character), and stimuli responsiveness (can be triggered easily by ionicity, pH, pressure, etc.). When incorporated into fibrous systems, they may provide tailored swelling behavior, controlled drug release, and even self-healing. Such versatility is further enhanced by the ability to tune mechanical strength, degradation rate, and interaction with biological tissues, which can be particularly valuable in biomedical fabric and wound healing.

Microcapsules offer a complementary strategy by encapsulating active agents within polymeric shells which have the potential to be embedded into or onto fibers. These capsules, similar to hydrogels, enable controlled release mechanisms triggered by subtle environmental changes, mechanical stress, or chemical stimuli. In fiber-based systems, microcapsules have been used to deliver fragrances, antimicrobials, and therapeutics, while protecting sensitive guest molecules from degradation. Techniques such as coaxial electrospinning and layer-by-layer assembly have allowed precise control over size, shell thickness, and permeability, making them ideal candidates for advanced functionality in smart textiles and filtration media.

Many advanced materials today have been labeled with the monicker of “smart”, but its meaning requires careful dissection to ensure its meaningfulness. In the context of textiles, “smart” refers to an ability to “sense” environmental parameters and generate a logical response; for example, a textile embedded with temperature-sensitive hydrogel fibers may be able to detect higher than normal skin temperature and respond by releasing a cooling agent or changing porosity to increase breathability. Similarly, fabrics integrated with microcapsules containing antimicrobial agents might rupture upon sensing increased acidity resulting from a bacterial load for targeted protection. These examples clearly demonstrate how “smart” is a term that encompasses an activity in health monitoring, environmental adaptation, and therapeutic delivery beyond passive wearables.

Smart textiles are therefore engineered to sense, react, and adapt to external stimuli. This responsiveness is achieved through integration of hydrogels, microcapsules, conductive polymers, or shape-memory alloys resulting in a new class of materials capable of dynamic behavior such as self-cleaning, drug release, or real-time feedback. In biomedical applications, smart textiles are developed for monitoring healing progress of wounds, to track vital signs, and to release medication in response to inflammation. In sports and fitness, they enable real-time performance tracking and thermal regulation. Environmental uses include filtration fabrics that adjust porosity.

Smart textiles nevertheless face challenges in durability, washability, power management, and comfort. Research is continually attempting to develop energy-efficient sensing mechanisms, biodegradable responsivity, and manufacturing scalability. In general, they are poised to redefine the interface between materials and human experience transforming garments into intelligent systems for optimized health.

Hydrogels, though inherently stimuli-responsive due to their dynamic behavior, are not always leveraged for their stimuli-responsive properties. For example, hydrogels are commonly utilized in extended-release systems in which the hydrogel experiences slow dissolution or mechanical rupture, releasing loaded material without taking advantage of the intelligent behavior of the hydrogel. In this sense, many hydrogel systems lacking environmental sensing and response behavior in their design are inaccurately labelled as “smart”. However, hydrogels can be utilized for tailored responsive release of loaded materials in response to many different stimuli, as explored in this review. Therefore, highly intelligent systems are possible using hydrogel materials.

In a similar manner, microcapsules are not necessarily stimuli-responsive, or “smart”. Microencapsulation is often used for protection of active agents using non-permeable shells that are designed not to rupture. Additionally, microencapsulation is commonly used for extended release by the gradual degradation of the microcapsule shells, not necessarily in response to specific stimuli. Often, the driving mechanism of active compound release from microcapsules is mechanical rupture caused by friction or pressure encountered during the product lifetime. While mechanical force could be considered an environmental stimulus, it is non-specific, often resulting in premature release of encapsulated ingredients. For more tailored release activity, microcapsules must be designed to respond to specific environmental stimuli which the microcapsules will not be exposed to until active ingredient release is desired. Herein lies the importance of stimuli-responsive microcapsules.

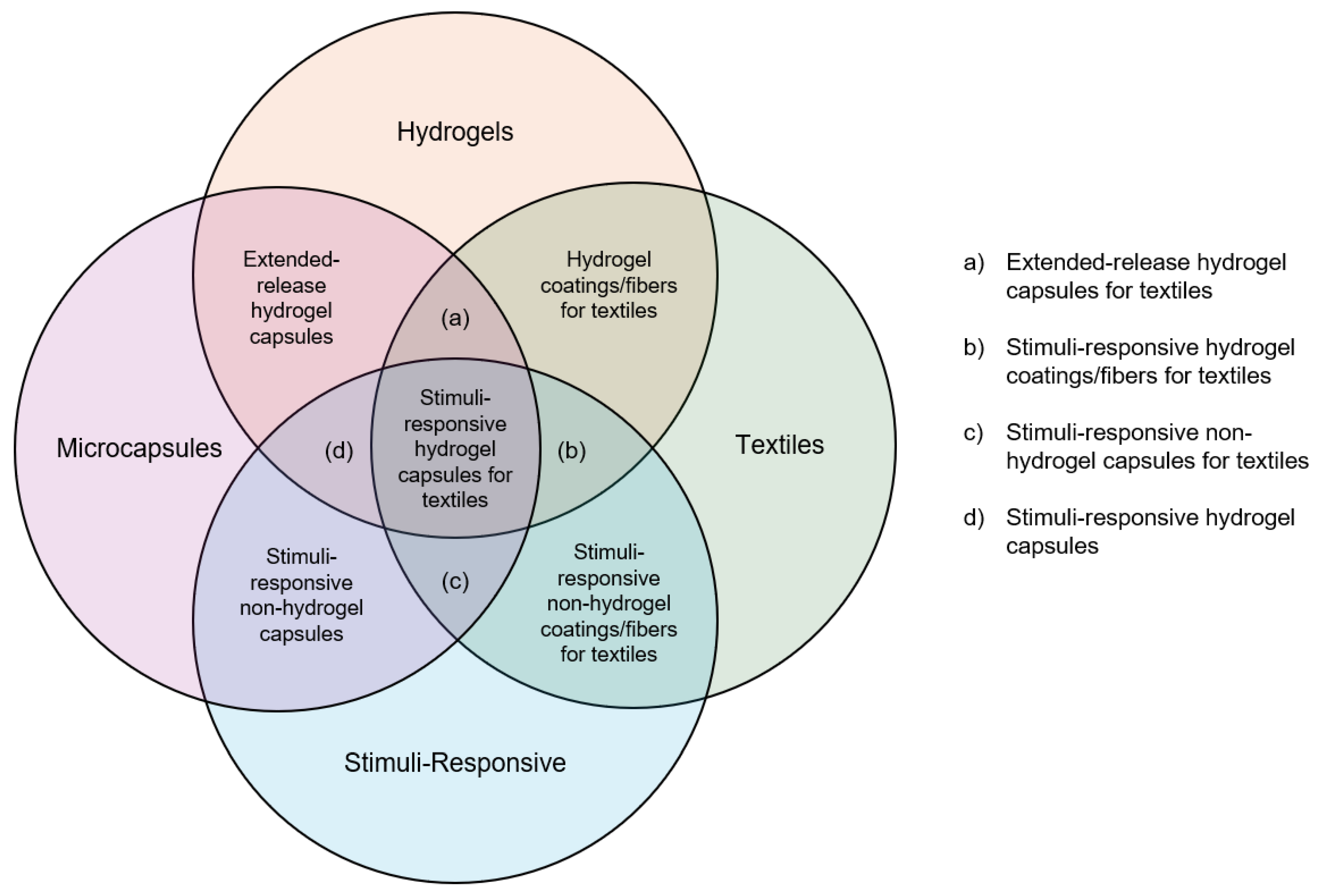

Figure 1 depicts the relationships between the areas of microcapsules, hydrogels, textiles, and stimuli-responsive behavior. Evidently, there are many areas of overlap, and these fields of research are intertwined. These research areas each offer great potential and cutting-edge research. However, much research falls in the outer lobes of the diagram, while very few works fall into the very inner category of stimuli-responsive hydrogel microcapsules for textiles. This review aims to provide an overview of the broad research areas, delve into the areas of overlap, and eventually come to a crux at the area of research where all areas intersect. At this core, as explored in this review, lies much potential for innovation.

2. Current Research

2.1. Hydrogels

2.1.1. Hydrogel Theory

Hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of crosslinked hydrophilic polymeric chains that swell in water to a defined water/mass equilibrium depending on the strength of the interaction [

1]. Indeed, they have been known to swell up to thousands of times their dry weight [

2]. When these hydrogels are dehydrated to a collapsed state, they may be referred to as “xerogels” which provide some unique functionality which we will discuss further in our review [

3].

Long term integrity may be encouraged in hydrogels with crosslinking network junctions, which may be observed during polymerization, as is the case with interpenetrating polymeric networks (IPNs), or post-polymerization, as in the gelation process of polyelectrolytes with multivalent ions. Hydrogels can be formed by various crosslink types, which can be broadly grouped into chemical and physical categories.

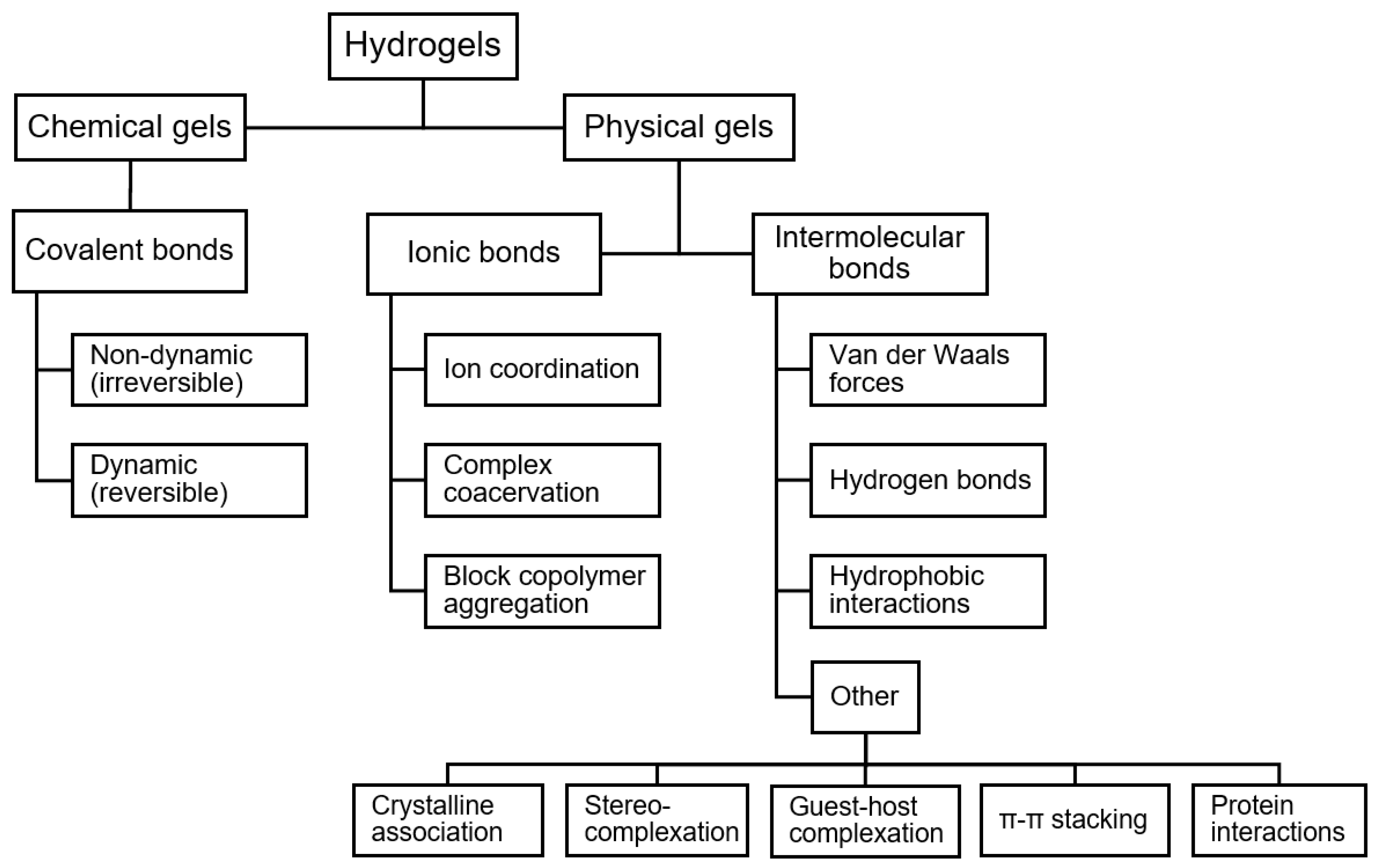

Figure 2.

Types of crosslinking in hydrogels.

Figure 2.

Types of crosslinking in hydrogels.

Chemical Gels

Hydrogels crosslinked by chemical, i.e., covalent, bonds are referred to as “chemical gels”. The covalent bonding in chemical gels constitute strong network interactions that yield strong gels, which generally exhibit superior mechanical properties and are more resistant to degradation than physical gels [

4]. The synthesis of chemical gels involves modification of polymer chemical structure and usually utilizes toxic agents that must be washed from the material to remove residue.

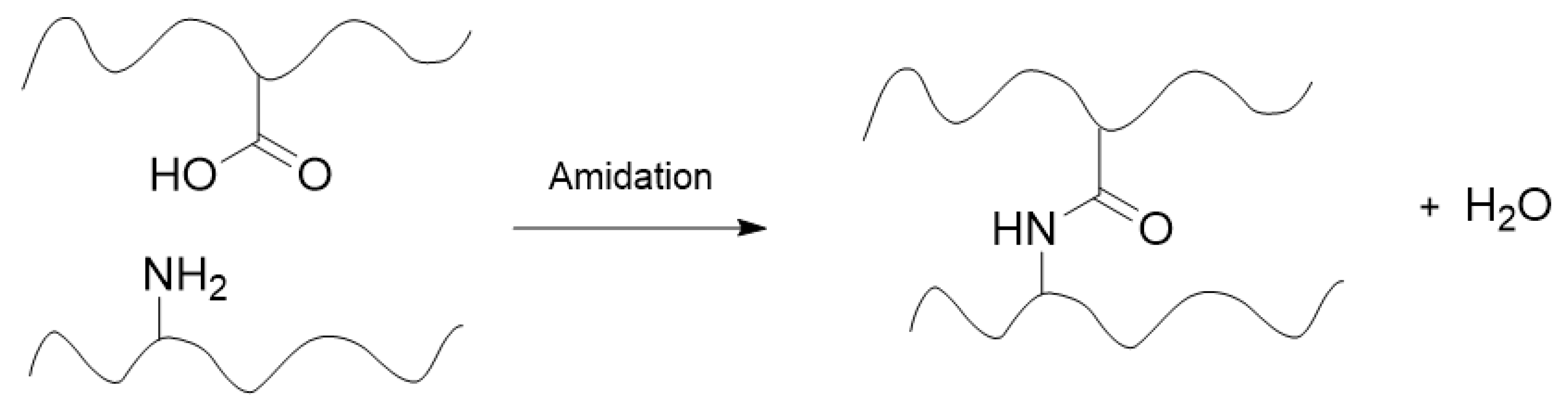

The covalent crosslinks may be non-dynamic, irreversible bonds formed by addition, condensation, free radical, anionic, or cationic polymerization, or via electromagnetic radiation [

5]. This can involve a variety of reaction types, including, but not limited to, Michael addition, amidation, and click chemistry [

6]. Traditional chemical gels are crosslinked with permanent covalent bonds, and as such, chemical gels are often referred to as “irreversible gels”. However, chemical gels may also be crosslinked by dynamic, reversible covalent bonds such as those formed through Diels-Alder, Schiff base, disulfide, boronic ester, and other reactions [

6]. This constitutes a subcategory of chemical gels not correctly described as “irreversible gels” due to their dynamic covalent crosslinks. These gels are useful for self-healing applications due to their adaptable nature [

7].

Figure 3.

Example of a chemical crosslinking reaction between two polymer chains within a hydrogel matrix.

Figure 3.

Example of a chemical crosslinking reaction between two polymer chains within a hydrogel matrix.

Chemical gels are generally more heterogenous than physical gels due to several factors. The first source of heterogeneity in chemical gels is the formation of clusters of high crosslinking density during gelation, which experience relatively low degrees of swelling. Another source of inconsistent composition is voids or macropores, filled with water, within the network structure, which result from phase separation during gelation. Thirdly, defects in hydrogel structure are caused by polymeric free chain ends and chain loops [

2].

Physical Gels

“Physical gels” are hydrogels crosslinked by additive physical interactions, including ionic bonds, intermolecular forces, and other interactions. The interactions in physical gels are thermally reversible and are strongly dependent on environmental conditions, making these materials more suitable for applications such as self-healing where the crosslinks must rearrange over a short time scale [

7]. These gels generally exhibit poorer mechanical properties than chemical gels and are less resistant to degradation due to weaker network interactions constituted by lower energy bonds [

4]. The synthesis of physical gels does not involve chemical structure alteration and is generally a less toxic process than the synthesis of chemical gels.

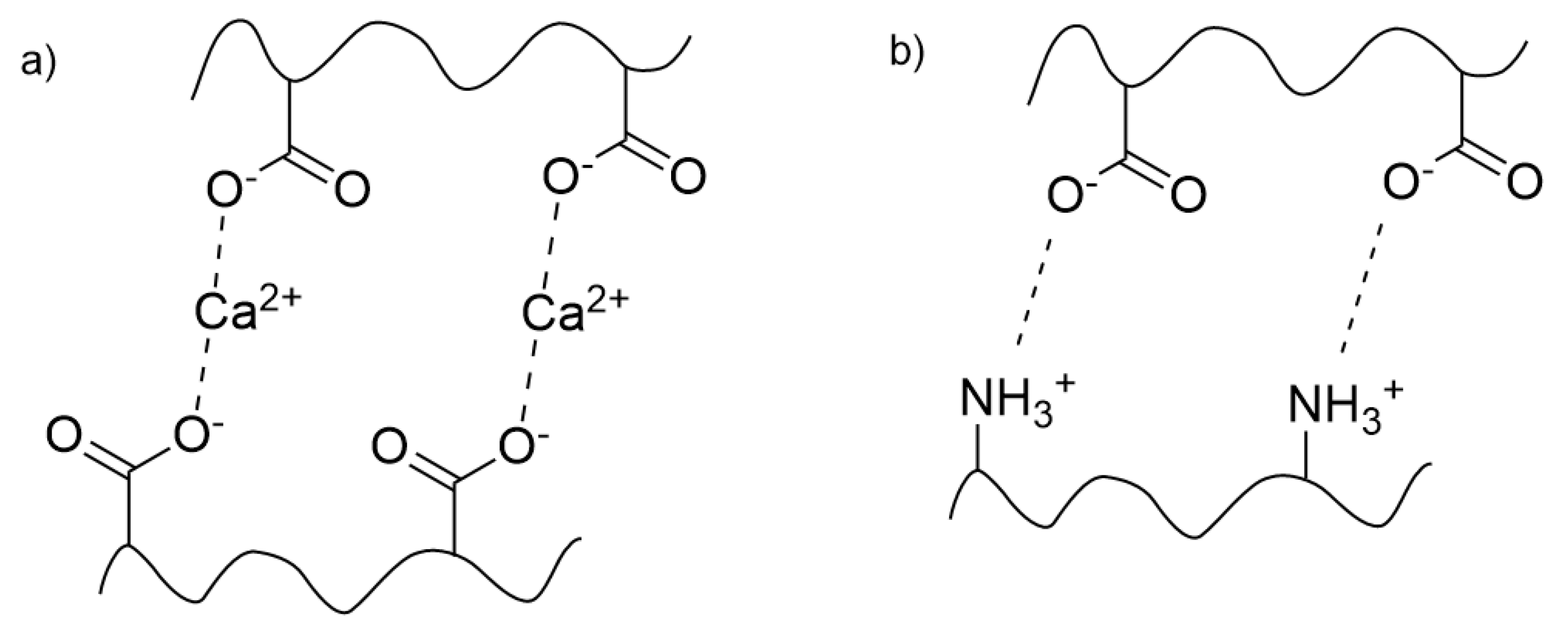

Hydrogels with ionic crosslinks are held together by electrostatic attraction between charged species and can be referred to as “ionomers”. Common types of ionic crosslinking in hydrogels are ion coordination, complex coacervation, and block copolymer aggregation. Ion coordination occurs between charged polymers and oppositely charged metal ions or small molecules such as polyoxoanions, low molecular weight organic acids, or multicarboxylates [

8]. Ionotropic gels, such as alginate crosslinked by calcium ions, are examples of hydrogels crosslinked by metal-ion coordination. Ionotropic gels are composed of a polyelectrolyte (a polymer containing repeating ionic moieties) mixed with an oppositely charged multivalent ion [

2]. Complex coacervates, also known as polyion complexes or polyelectrolyte complexes, are crosslinked by complex coacervation. These gels are mixtures of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes that exhibit liquid-liquid phase separation and coalesce into a polymer-rich phase in water [

9]. Block copolymer aggregation occurs in triblock or multiblock gels, where ionic blocks aggregate into micelle-like domains with bridges or interlocking loops that serve as crosslinks in the gel network [

10].

Figure 4.

Examples of ionic crosslinking in physical hydrogels; a) an ionotropic gel (in this case, involving metal ion coordination) and b) a complex coacervate.

Figure 4.

Examples of ionic crosslinking in physical hydrogels; a) an ionotropic gel (in this case, involving metal ion coordination) and b) a complex coacervate.

Hydrogels can also be crosslinked by intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonds, Van der Waals forces, or hydrophobic interactions between polymer chains. Other possible physical interactions include crystalline domain association, stereo-complexation, guest-host inclusion complexation, π-π stacking, and protein interactions [

11,

12]. Crystalline domain association occurs due to strong cooperative intermolecular forces within crystalline domains that serve as junctions, as observed in freeze-thawed PVA hydrogels [

13]. Stereo-complexation involves stereoselective interactions between sterically complementary stereoregular polymers, such as two opposite enantiomeric polymers or a pair of isotactic and syndiotactic polymers [

14]. Guest-host inclusion complexation occurs when a guest molecule binds to the internal cavity of a macrocyclic host and these interactions serve as physical crosslinks, as observed in cyclodextrin-PEG inclusion complex gels [

12,

15]. In π-π stacking, structures containing aromatic groups, such as graphene oxide sheets, self-assemble to promote interactions between overlapping π clouds [

16]. Protein interactions encompass a wide range of associative effects that can occur between proteins in hydrogels synthesized with artificial proteins. Secondary structures can experience ordered association between β-sheets or α-helices, or collapse based on environmental conditions, resulting aggregation of disorder proteins into soft networks [

17,

18]. Self-interacting domains such as coiled-coil motifs or leucine zippers, as well as specific binding sites, can act as junctions in protein hydrogels [

12,

19,

20].

Physical gels are generally more homogenous than chemical gels, but heterogeneity can result from domains of chain entanglements or strong ionic/intermolecular associations, hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions, or the presence of free chain ends and chain loops that also cause defects in chemical gels [

2,

4].

Hydrogel Composition

Hydrogels may be homopolymeric, copolymeric, physical blends, or IPNs (crosslinked polymeric networks formed in the presence of another crosslinked polymeric network) [

1]. The morphology of hydrogel networks can range between amorphous, semicrystalline, supramolecular, and colloidally aggregated. The structure of hydrogels depends on many factors including monomers, solvent, and synthesis method [

1]. Therefore, hydrogels are a broad class of materials that can exhibit a variety of crosslinking types, compositions, structures, and morphologies, resulting in diverse, tailorable behavior and a breadth of potential applications.

Hydrogels are usually synthesized with a hydrophilic monomer reacted via bulk, solution, or inverse dispersion with some kind of initiator and crosslinking agent [

21]. Many different monomers have been used to create hydrogels; a summary of common hydrogel monomers is shown in

Table 1. Other monomers are possible to incorporate, including hydrophobic monomers if copolymerized with hydrophilic ones.

The properties of hydrogels vary greatly, but in general, they can be described as soft, hydrated, superabsorbent, viscoelastic materials that are insoluble in water. They may be neutral, cationic, anionic, or ampholytic, depending on the polymer used and the pH of the environment. They experience low interfacial tension with aqueous media and good diffusion, usually containing macropores greater than 50 nm in size [

6,

22]. Hydrogels are nontoxic, biocompatible, bioadhesive, and mucoadhesive, making them suitable for medical use.

Water in Hydrogels

The water present in hydrogels can be classified as bound water, free water, or semi-bound water. Bound water consists of primary bound water, which is attached via hydrogen bonding to polar moieties on the polymer chains, and secondary bound water, which interacts with the hydrophobic moieties on the polymer chains [

23]. Primary bound water is the first interaction formed when hydrating a xerogel, followed by secondary bound water [

2]. Bound water may only be removed with high temperature [

23]. Free water fills the voids and macropores in the polymeric network, and the space in between polymer chains (water physically entrapped between hydrated polymer chains is often referred to as interstitial water) [

2,

23]. Free water is easily removable with mechanical force – for example, compression or centrifugation [

23]. Semi-bound water exhibits intermediate characteristics of both free and bound water [

23]. The water molecules in hydrogels rapidly interchange between bound and free states [

2].

The swelling capacity of a hydrogel is dependent on the space available within the polymer network [

21]. The forces responsible for the swelling behavior of hydrogels can be categorized into three driving forces: polymer-water interactions, osmotic forces, and electrostatic forces. Polymer-water interactions are attractive forces that occur between hydrophilic groups on the polymer chains and water molecules [

21]. More hydrophilic polymers experience stronger polymer-water interactions and therefore form stronger bonds with water [

21]. Osmotic forces are generated by the free counterions present in ionic hydrogels, which create an ion concentration differential between the hydrogel and the external environment [

21]. This results in osmotic pressure that drives the hydrogel towards a state of infinite dilution [

2]. Electrostatic forces are repulsive forces between ionic groups of polyelectrolytes, which cause an expansion in volume that results in the absorption of water [

21]. These swelling forces sum to balance the elastic forces created by crosslinking, resulting in an equilibrium that explains the insolubility of hydrogels in water [

21].

The swelling mechanism of hydrogels can be described as a two-step process involving diffusion of water followed by relaxation of the polymer chains. The rate of swelling is influenced by the rate of diffusion of water, which depends on solvent molecular weight, solution temperature, and hydrogel porosity [

21]. In the relaxation step, amorphous regions of hydrogels undergo stress relaxation induced by osmotic swelling pressure. Water molecules form hydrogen bonds with the polymer chains, reducing the attractive forces between adjacent chains and thereby plasticizing the polymer network such that the polymer chains can slide past each other to accommodate swelling [

24]. Limited relaxation can occur in highly crosslinked hydrogels due to limited chain movement and therefore relaxation becomes the rate-determining step for the swelling mechanism of these hydrogels [

21].

Xerogels are dehydrated hydrogels that have collapsed into dense, porous networks upon ambient evaporative drying. The properties of xerogels, including moderate porosity, high surface area, tunability, biocompatibility, and mechanical stability, provide unique functionality [

25]. For example, in biomedicine, their porosity can be leveraged for active ingredient loading for drug delivery and is optimal for cell proliferation in tissue engineering scaffolds [

26]. The properties of xerogels have also made them materials of interest for catalysts, adsorbents, and sensors [

27].

History and Applications

Early research on crosslinked polymeric networks, focused on reaction kinetics and mechanical property analysis, began in the mid-1930s in Germany and work on “natural hydrocolloids” began in the late-1930s [

1]. The first commercial application of hydrogels was hard contact lenses made with poly(methyl methacrylate) in the late-1930s [

28]. The pioneer of hydrogel theory was Paul Flory (Nobel Prize 1974), who focused on thermodynamic and statistical mechanical analysis [

29]. For example, Flory-Rehner theory describes hydrogel equilibrium swelling behavior by ascribing two contributors to Gibbs free energy: a mixing term resulting from polymer-solvent interactions and an elastic term resulting from network chain stretching [

30]. This theory has since been modified, for example to include an ionic interaction term, but has served as the basis for modern study of hydrogel swelling behavior along with other aspects of Flory’s work [

31]. In 1960, Wichterle and Lim pioneered the study of crosslinked poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate) hydrogels, specifically for biomedical uses such as contact lenses [

32]. The first application of hydrogels for wound dressings was crosslinked collagen-glycosaminoglycan seeded with dermal and epidermal cells as an extracellular matrix analog by Yannas et al. in 1989 [

33].

Nowadays, hydrogels are popular materials used for many common applications, including surface coatings; hygiene products such as diapers and sanitary products; cosmetics; gelling agents in food; biosensors for biomedical, pharmaceutical, and environmental applications; water treatment; and soil amendment [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. They are still used for contact lenses and wound dressings [

41,

42]. They are also widely used for tissue engineering, including soft tissue fillers for breast reconstruction, artificial corneal substitutes, and composite living fibers [

43,

44,

45]. Additionally, hydrogels are popular materials for advanced drug delivery, enhancing oral, transdermal, and in-situ drug delivery technology [

46,

47,

48].

2.1.2. Responsive Behavior of Hydrogels

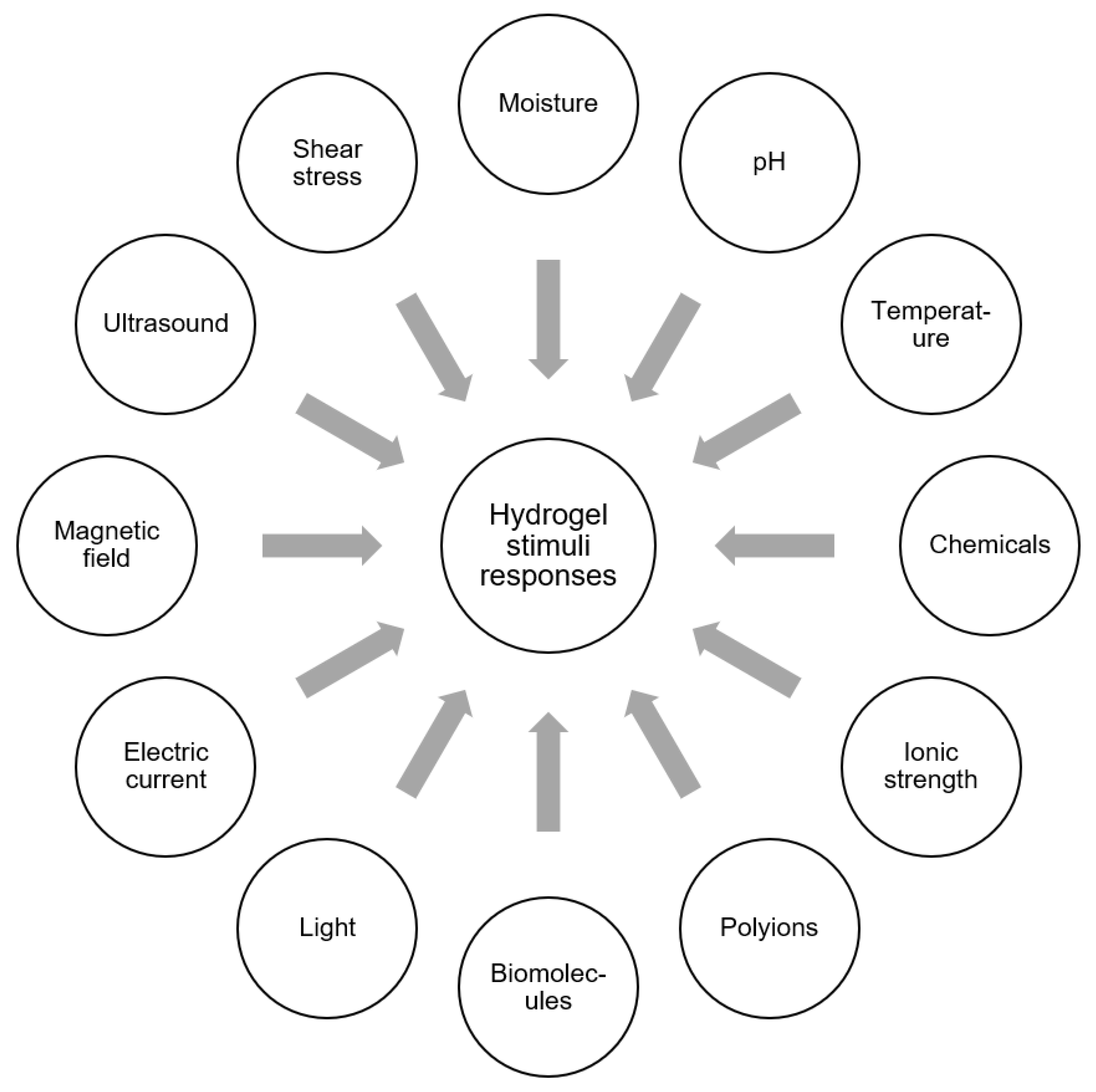

Hydrogels exhibit responsive behavior which can be triggered by a wide range of stimuli, depending on the polymer used. Hydrogels may be responsive to one or more stimuli and therefore represent highly dynamic systems that can be tailored to respond to various environmental conditions. This adaptability can be leveraged for many different applications, including those requiring feedback-adaptive behavior or “on-off” switchability. A summary of stimuli that have been demonstrated to illicit a response in hydrogels or hydrogel composite materials is shown in

Figure 5. In some cases, dual-responsive or multi-responsive hydrogels have also been developed to respond to two or more of these stimuli. For example, IPNs can display dual responsivity due to independent responses from each individual network.

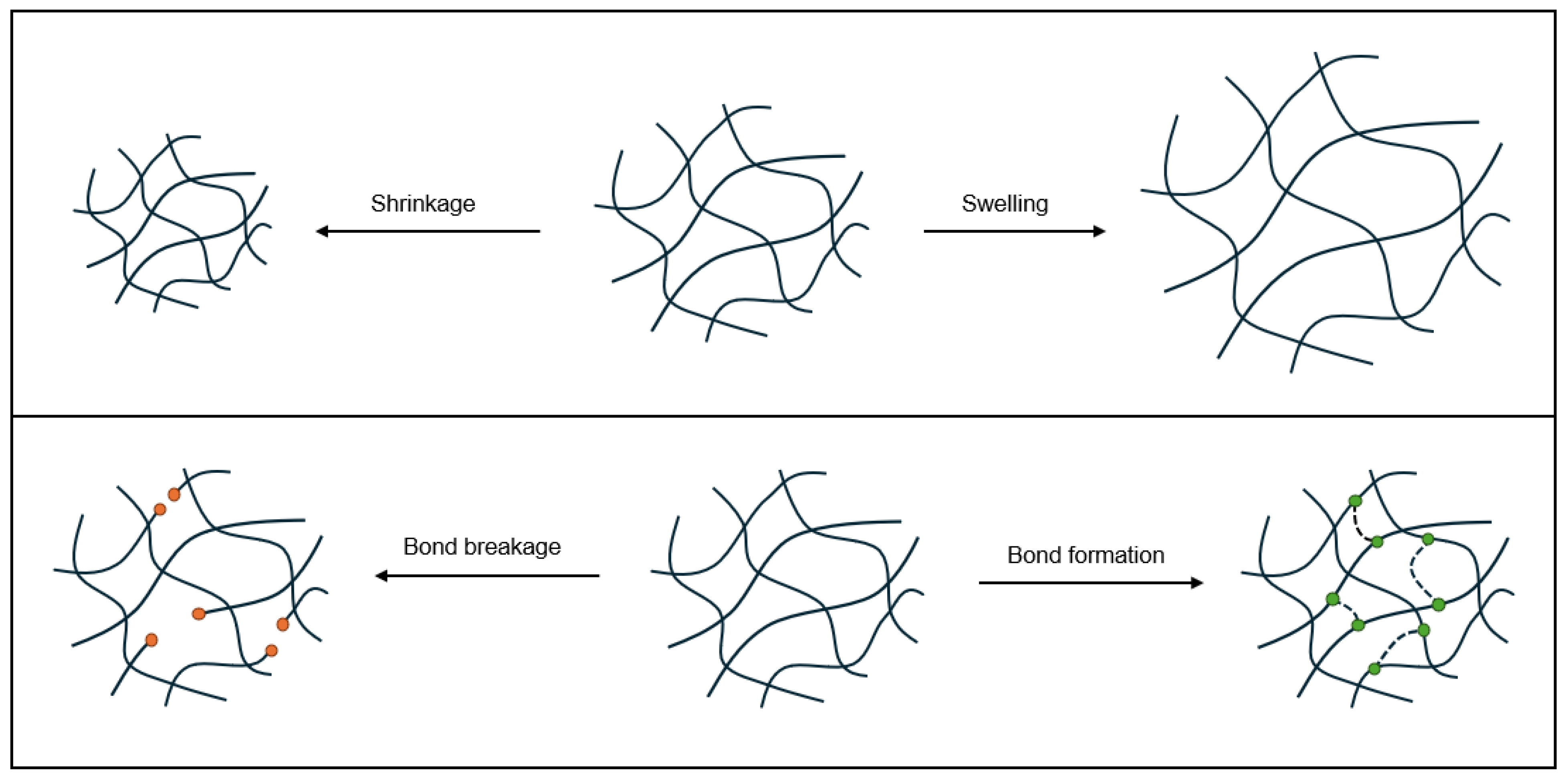

Under ideal conditions, stimuli responses in hydrogels are reversible [

28]. There are two mechanisms that are largely responsible for all stimuli responses in hydrogels: shrinkage or swelling, and a change in crosslinking density. These two mechanisms are shown in

Figure 6. Shrinkage or swelling in hydrogels may be isotropic, i.e., a direct and uniform decrease or increase in volume, or anisotropic, which can result in shape morphing of the hydrogel (rolling, twisting, bending, folding, etc.). Anisotropic shrinking or swelling can be caused by layers or zones of different polymers with different sensitivities or thresholds for swelling [

49]; for example, polymers with different swelling rates, or shape memory polymers combined with non-shape memory polymers. Anisotropic shrinking or swelling behavior can also result from gradients of crosslinking density, which influences the swelling rate [

50]. The latter aforementioned mechanism of stimuli response – a change in crosslinking density – can be caused by reversible bond formation or breakage, or isomerization of chains or groups involved in crosslinking. Crosslinking density is proportional to mesh size, a measure of porosity in hydrogels, equal to the average linear distance between crosslinks [

1].

Moisture

Moisture is the most obvious stimulus that causes a response in hydrogels. The swelling behavior of hydrogels is described in Section 1.1.1. In short, absorption of water swells the hydrogel network, and desorption of water shrinks the network. The moisture-responsivity of hydrogels causes a high susceptibility of hydrogel materials to respond to environmental humidity changes, which can be a challenge for material and product development [

51]. However, many hydrogel materials are developed specifically for their moisture-responsive behavior, which can be desirable in many applications, including moisture-management materials, humidity sensors, soft actuators, and drug delivery [

52,

53,

54,

55].

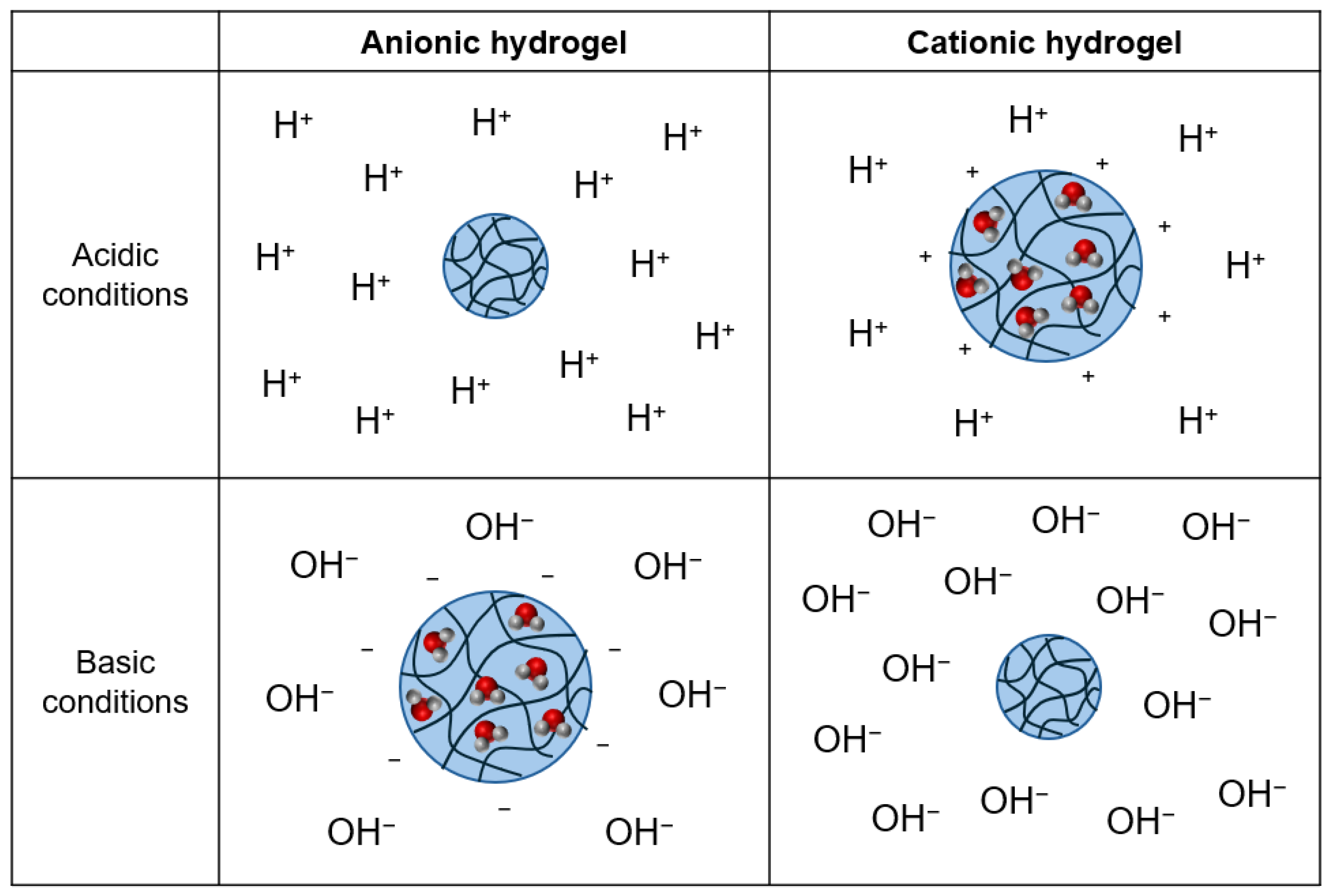

pH

pH-responsive behavior is observed in ionic hydrogels as ionization of pendant groups creates a build-up of charge along polymer chains [

1,

56]. This generates electrostatic repulsion between the charged groups [

57]. pH-responsive behavior can also occur in nonionic hydrogels containing hydrogen bonded crosslinks as ionization of hydrogen bond donor and/or acceptor groups causes dissociation of the crosslinks [

58]. In both systems, electrostatic repulsive forces and osmotic pressure are generated that swell or shrink the hydrogel and absorb or expel water to reduce the osmotic pressure differential [

1,

56]. This phenomenon is depicted for both anionic and cationic hydrogels in

Figure 7.

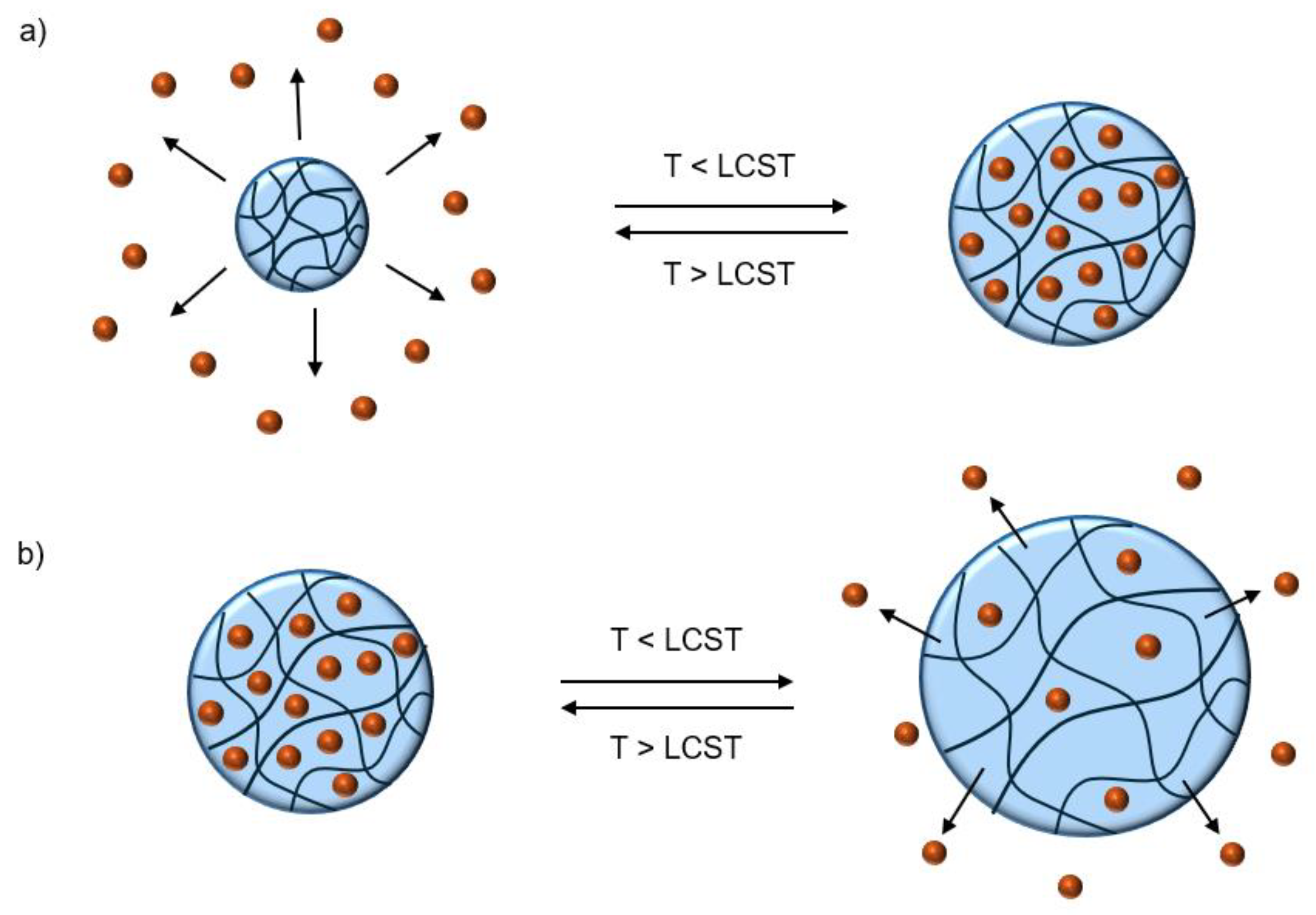

Temperature

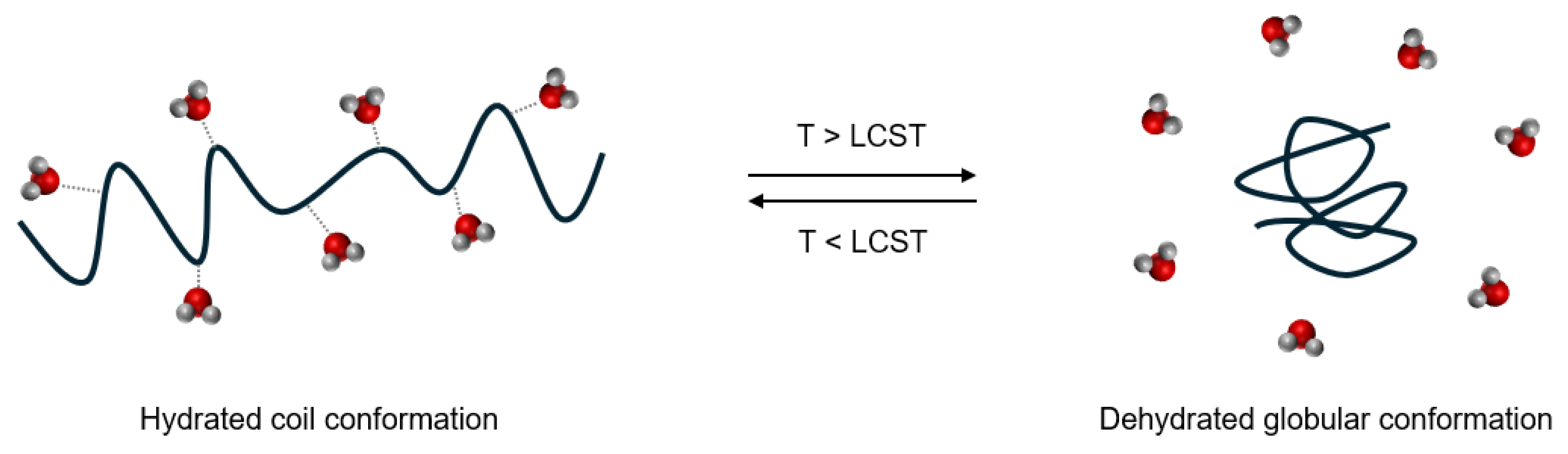

Temperature responsive behavior is observed in hydrogels made with thermoresponsive polymers. These hydrogels experience a shift in aqueous solubility of the polymer backbone in water, resulting in shrinking/swelling of the network [

1]. In its hydrated coil state, the polymer backbone is hydrated by water molecules to increase its aqueous solubility. The hydration shells come at a high entropic cost since water molecules must coordinate with hydrophobic groups on the polymer backbone. As temperature increases, these hydrogen bonds are disrupted until the network collapses into a dehydrated globular state, expelling water from within [

1]. For inverse temperature responsive polymers, the temperature at which this occurs is referred to as the “lower critical solution temperature” (LCST). This conformational change is depicted in

Figure 8. Common examples of inverse temperature responsive polymers are N-alkyl substituted polymers such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) and poly(N,N-dimethylallylamine) (PDEAAm). The LCST of these polymers can be increased by copolymerization with hydrophilic monomers or decreased by copolymerization with hydrophobic monomers [

59]. Other inverse temperature responsive polymers include chitosan, poly(vinyl methyl ether), poly(vinyl caprolactones), poly(ethylene oxide)–poly(propylene oxide), and poly(ethylene glycol).

Responsive PNIPAAm hydrogels have been widely applied for responsive release in drug delivery systems since the 1990s; the technology of which has since been applied to the development of self-regulating insulin delivery systems and targeted laser-triggered cancer treatment [

60,

61,

62]. PNIPAAm hydrogels can undergo thermally induced in situ gelation, a behavior which has been utilized in injectable scaffolding systems for drug delivery and tissue engineering [

63]. PNIPAAm hydrogels have also been applied to interfaces for cell sheet engineering applications, providing thermo-switchable adhesion for cell culturing [

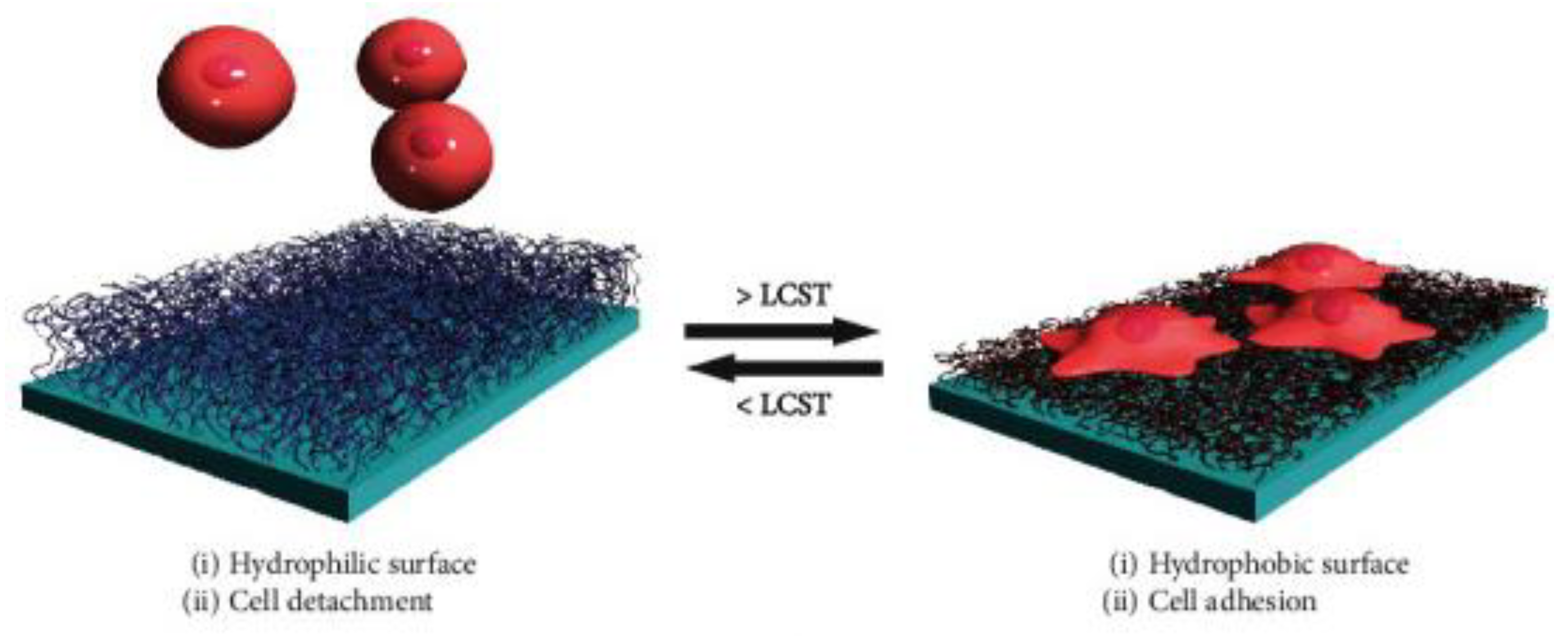

64]. The responsive behavior, driven by temperature induced hydrophilicity changes, of such a culture surface is shown in

Figure 9 [

65]. Beyond biomedicine, PNIPAAm hydrogels have been used for sensors and indicators for a wide variety of small molecules, macromolecules, and biomolecules, and more recently volatile organic compounds in gaseous environments [

66,

67]. Emerging applications in soft actuators and robotics are also being developed using PNIPAAm hydrogels [

68,

69].

Normal temperature responsive polymers are much less common but include polyacrylamide (PAM) and poly(acrylic acid) (PAA). In this case, the hydrogen bonds between acrylamide and acrylic acid do not allow the formation of a hydrated gel, so the network is collapsed. There is a high entropic cost of the separation of water and polymer phases in this dehydrated state, so as temperature increases, the network “unzips” to allow the absorption of water [

1]. The temperature at which this occurs is referred to as the “upper critical solution temperature” (UCST).

In addition to the temperature response mechanism described above, physical hydrogels can experience a sol-gel phase transition in response to temperature [

57]. The liquid (sol) phase is hydrated and hydrophilic in nature, which the solid (gel) phase is dehydrated and hydrophobic [

28]. Phase separation occurs, i.e., the polymer solution transitions from isotropic and anisotropic, at the critical solution temperature [

22].

Chemicals and Biomolecules

Hydrogels can be tailored to interact with many different chemicals or biomolecules. Hydrogels are commonly developed to behave in response to glucose because of its biological significance and the potential medical applications of these hydrogels. There are several methods of creating glucose-responsive hydrogels. Hydrogels containing glucose oxidase will oxidize glucose to gluconic acid, causing a localized change in pH that can swell the hydrogel [

20]. Alternatively, hydrogels containing phenylboronic acid will complex with glucose, generating negatively charged boronic esters that can result in swelling of the hydrogel [

1]. Another method involves incorporating concanavalin A into a hydrogel with glucose-containing polymer chains, causing crosslinking that results in a reversible sol-gel transition controlled by glucose concentration [

57].

Enzyme-responsive hydrogels can be created by incorporating peptide chains as crosslinks in the hydrogel network or as bonds between the core and shell of a microcapsule. The peptides are digested by specific enzymes, resulting in responsive degradation of the hydrogel [

1]. Additionally, products of enzymatic degradation can trigger swelling or shrinking of a hydrogel [

23].

Responsivity to other chemicals can be created with the use of molecularly imprinted polymers, wherein binding sites are created in the hydrogel by synthesizing the network in the presence of a template molecule [

1]. An alternative method involves electron donor-acceptor complex formation between specific chemical species and the hydrogel [

23].

Ionic Strength and Polyions

Hydrogels can exhibit ionic strength responsivity due to ionization of the polymer backbone or pendant groups, causing a change in the swelling equilibrium [

70]. At high ionic strengths, gelators in the hydrogel can bind preferentially with salt ions, resulting in a decrease in crosslinking density in the hydrogel network [

71]. In cases of solute-loaded hydrogels e.g., for drug delivery, increased ionic strength shields charges in the polymer network, reducing electrostatic repulsion or attraction between the hydrogel and the solute. This leads to diffusion of the solute into the environment [

1].

Polyelectrolyte gels, in addition to ionic strength, exhibit responsive behavior to the presence of polyions. Immersing a polyelectrolyte gel, which is a charged hydrogel network, into a polyionic solution of opposite charge results in electrostatic complexation that expels water from the network, causing shrinking of the hydrogel network [

72].

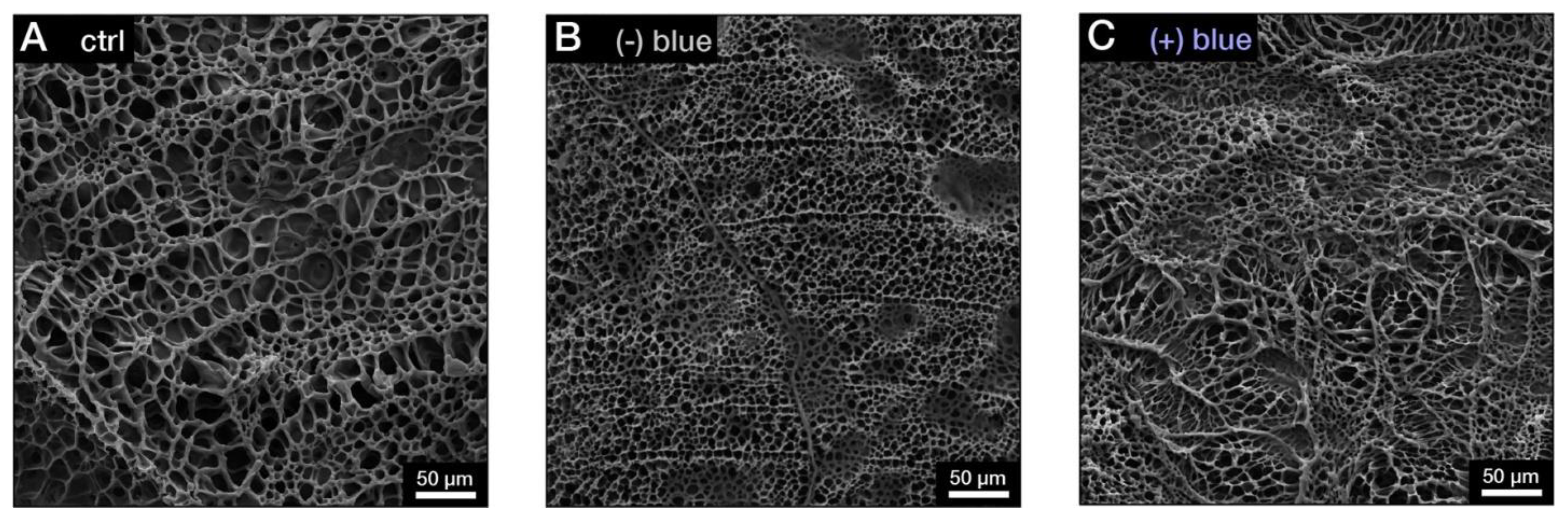

Light

Incorporating photosensitive monomers into hydrogels as pendant groups or crosslinkers, or incorporating photosensitive nanoparticles into the hydrogel structure, can yield light-responsive hydrogels. Photosensitive compounds undergo changes in response to light that disrupt the hydrogel network. These changes can include isomerization, such as a cis-trans shift, cyclization, or ring-opening. Azobenzene and spiropyran, discussed in

Section 2.2.4, undergo photoinduced isomerization. The photosensitive response of hydrogels containing azobenzene crosslinker is visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in

Figure 10 [

73]. Other changes include degradation, which involves the breaking of covalent bonds, or dimerization, which involves the formation of a bond between two units. Photolabile moieties include o-nitrobenzyl ether derivates, coumarin derivatives, allyl disulfides, and Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes [

74,

75]. Another mechanism of photo-responsivity is photothermal conversion, whereby light-absorbing compounds convert photo energy into thermal energy, resulting in thermoresponsive shrinking or swelling of the hydrogel. The compounds can include near-infrared absorbers such as polydopamine (PDA) or ultraviolet absorbers such as metal and metal oxide nanoparticles e.g., SiO

2 and TiO

2 [

76,

77].

Electric Current

All polyelectrolyte gels are electrically responsive. Nonionic hydrogels can be coupled with dielectric liquids or electrically responsive particles to create electrically responsive hydrogels [

1]. The electric response of a hydrogel is proportional to its charge density and inversely proportional to its degree of crosslinking, and influenced by the properties of the surrounding medium (dielectric constant, pH, ionic strength, etc.) [

1]. An applied electric field attracts the charged moieties in the hydrogel network and the free counterions in the surrounding media in opposite directions. This stress gradient causes the hydrogel network to contract, constrained by crosslinking, and the movement of counterions creates both local pH changes and osmotic potential that carries water molecules with the counterions, further shrinking the hydrogel network [

78].

Magnetic Field

Magnetic-responsive hydrogels can be created by incorporating magnetic microparticles or nanoparticles into hydrogels. Magnetic hydrogels can induce several response modes, including locomotion, deformation, and thermogenesis [

79].

Ultrasound

Ultrasound-responsive hydrogels can result from the transfer of acoustic energy into thermal or non-thermal energy. In the thermal response mechanism, ultrasound waves can cause localized heating that results in swelling or shrinking of thermoresponsive hydrogels [

23]. The non-thermal response mechanism involves the generation of mechanical energy as oscillations or forces that create acoustic cavitation or acoustic radiation [

80].

Shear Stress

Hydrogels exhibit viscoelastic mechanical behavior. Shear stress triggers shear-thinning or shear-thickening behavior in hydrogels, resulting in shear-responsive dissociation and re-association of the network [

1,

81].

2.1.3. Bulk Hydrogels for Smart Textiles

Hydrogels can be applied to fabrics to incorporate stimuli-responsive behavior into textile materials. Hydrogels can undergo gelation directly on the surface of the fabric by soaking the fabric in a polymer solution followed by soaking in a crosslinking solution [

3]. Other methods of incorporating hydrogels into textile systems include coating or finishing fabrics with hydrogels, incorporating hydrogel micro or nanoparticles (micro or nanogels) into fabrics, or functionalizing fibers with hydrogels. Textile surface modification is reviewed in more detail in

Section 2.3.2.

A common application of hydrogel textiles is comfort textiles, which leverage the shrinking and swelling or sol-gel transition of hydrogels to regulate temperature of the wearer. In its swollen state, the hydrogel blocks pores in the textile material, thereby trapping body vapor and retaining heat under the garment [

23]. Conversely, when the hydrogel is in its shrunken state, the textile material is more porous and breathable, allowing the release of body vapor and heat into the external environment. An example of a thermoregulating textile material is the cotton material finished with PNIPAAm/chitosan microgels by Kulkarni et al. using a simple pad-dry-cure application method [

82]. The material demonstrated dual responsive behavior towards temperature and pH. At high temperatures, the hydrogel microparticles collapsed and allowed increased water uptake. This behavior was modulated by pH due to the incorporation of chitosan into the hydrogel. Another example is the PEG–PCL–PEG copolymer coated absorbent nonwoven fabric developed by Bin Fei’s group at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, which exhibited a thermoresponsive sol-gel transition [

83]. Gelation was triggered around skin temperature, causing the coating to transition from hydrophilic to hydrophobic and creating pores that served as capillary channels for water transport. This system facilitated unidirectional moisture wicking away from the skin at body temperature.

Another common application for hydrogel textiles is active compound delivery in a variety of product types, including medical textiles, cosmetotextiles, and hygiene textiles [

22]. Hydrogels serve to allow controlled or extended release in these systems, whereby the active compounds are incorporated into the hydrogel network and exposure of the hydrogel to stimuli triggers shrinking of the hydrogel network, causing release of the active compounds [

23]. An example of such a system is the cellulose fabric grafted with PNIPAAm/PU hydrogel and chitosan developed by Hu et al. at Hong Kong Polytechnic University for antibacterial facial masks [

84]. The masks were loaded with functional components such as vitamins and aloe extract that released at body temperature upon shrinking of the hydrogel network. Additionally, rinsing of the masks allowed for purification and subsequent reabsorption of nutrients for reuse. Another example is the Pluronic F127/carboxymethylcellulose sodium composite hydrogel developed by Chi-Wai Kan’s group at Hong Kong Polytechnic University for hydrogel functionalized fabrics to treat atopic dermatitis [

85]. The material served dual functionality of moisture supply and controlled transdermal drug delivery of Cortex Moutan (CM) extract, a traditional Chinese medicine. Thermoresponsive sol-gel transition of the porous hydrogel structure facilitated diffusional release of CM while the hydrogel’s high moisture content provided moisture to skin.

Antibacterial fabrics are another common application of hydrogel textiles. For example, Wang et al. at Eastern Liaoning University developed cotton fabric modified with PNIPAAm/chitosan hydrogel IPN with a double-dip-double-nip process [

86]. The fabric demonstrated antibacterial activity, with bacterial reduction against

E. coli and

S. aureus of more than 99%, and thermoresponsive hydrophobicity. Chitosan has natural antibacterial properties and is therefore a useful natural polysaccharide for medical textile applications [

87]. Reversible wettability can also be achieved with hydrogel textile systems, as demonstrated by Jiang et al. at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who developed cotton fabric grafted with PNIPAAm and 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane [

88]. The fabric showed temperature-responsive superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic behavior.

Hydrogel textiles can also be used for water filtration, including oil-water separation and pollutant adsorption. For example, Lin Feng’s group at Tsinghua University developed temperature and pH-responsive mesh coated with PDMAEMA for oil/water separation [

89]. The mesh allowed water to permeate at temperatures below 55 °C (pH 7) or pH < 13 (T = 25 °C) and allowed oil to permeate at temperatures above 55 °C or pH > 13, enabling orderly permeation and separate collection of water and oil. Li et al. at Zhejiang Ocean University developed cotton fabric coated with PDA/chitosan that functioned as an oil and heavy-metal ion removal membrane [

90]. The superhydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic material adsorbed Cu(II) from wastewater with 99% efficiency.

Evidently, the applications of hydrogel-treated textiles are broad. However, bulk hydrogel treatments such as coating can negatively influence the original properties of the textile material such as stiffness or tensile strength [

28]. Additionally, textiles treated with bulk hydrogels experience slow solvent diffusion, and therefore slow swelling kinetics that can result in slow response times in smart textiles [

3]. This has prompted a diversification of hydrogel application methods for textiles, expanding into other forms such as micro/nanogels and microcapsules.

2.2. Microencapsulation

2.2.1. Introduction to Microencapsulation

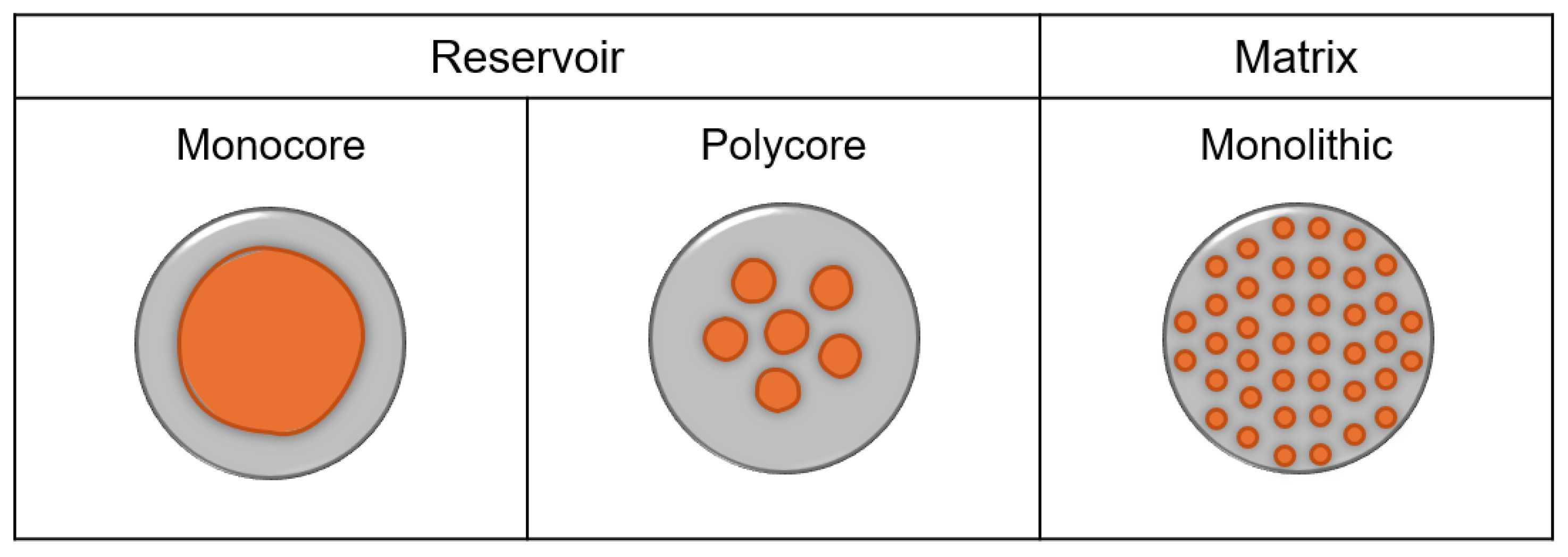

Microencapsulation is the process of entrapping active substances in solid, liquid, or gaseous form within an inert shell, producing particles within which the core material is protected from the external environment [

91,

92]. By definition, the size of microparticles is 1 – 999 µm, but the term is often used to refer to particles of up to mm scale [

93]. Microcapsules can be classified as reservoir, including monocore and polycore structures, or monolithic matrix, which contain evenly dispersed encapsulating and encapsulated phases and are sometimes referred to as microspheres [

93]. These microcapsule types are shown in

Figure 11. Microcapsules can display a range of release characteristics, such as permeation, dissolution, mechanical rupture, thermal release, pH and osmotic release, photolytic release, biodegradation, delayed release, and isolation (non-release) [

93]. Microcapsule shells can be permeable, allowing core material release to be controlled by shell thickness and pore size, semi-permeable, whereby the shell is impermeable to the core material, but permeable to low molecular weight compounds, or impermeable, which requires shell rupture for core material release [

92]. Smart microcapsules utilize stimuli-responsive material as shell materials or grafted onto pores in the shells to allow for stimuli-controlled release of core material.

Microencapsulation has a multitude of benefits in industrial or commercial applications. An inherent advantage of microencapsulation is that the core material is shielded from contact with the environment that may otherwise cause unwanted chemical reactions, such as degradation, oxidation, or polymerization, and exposure to conditions such as moisture, heat, alkalinity, or acidity is prevented [

94,

95]. Microcapsules can control the release of the active compound from a product, resulting in better performance, lower costs, enhanced shelf-life, and other benefits [

93]. Stimuli-responsive and location-targeted release are also possible for highly specific and tailorable delivery systems. Besides customizable release profiles, microencapsulation can be used for permanent encapsulation, which can improve the solubility and dispersibility of the core material for better processability [

92]. Microcapsules can convert liquid compounds to free-flowing solids that are easier to handle, reducing clumping, improving mixing, increasing production speed, and expanding production capabilities [

93,

94]. The smaller size of microparticles allows for higher dispersion and therefore better control over the encapsulated material in a formulation [

93]. Additionally, microencapsulation can offer protection against hazardous or toxic materials for employees, users, and the environment [

93]. Encapsulating compounds in a shell material can mask unpleasant odors or tastes in food or pharmaceutical formulations or provide enzyme or microorganism immobilization capabilities [

92]. The multitude of benefits of microencapsulation technology has resulted in the utilization of this technique across food, agriculture, cosmetic, biomedical, and textile industries.

The first commercial instance of microencapsulation in a coating formulation was for the development of carbonless copy paper by Green and Lowell at National Cash Register Co. in the 1950s [

96]. The transfer film coating contained hydrocolloid microcapsules filled with oil that was released by rupture of the capsules. Nowadays, microencapsulation technology is widespread across textiles, agricultural formulations, paints and coatings, bulk chemicals, cosmetics, hygiene products, medical textiles, home care products, foods, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals [

91,

97]. Most people unknowingly benefit from microencapsulation technology daily – laundry detergents and fabric softeners contain microencapsulated fragrances for long-lasting scent, oral medications use microencapsulation for extended drug release or protection of labile ingredients such as probiotic bacteria, and many food products contain microencapsulated ingredients for consumer nutrition or food stability and preservation [

98,

99,

100].

2.2.2. Microencapsulation Techniques

The process of microencapsulation involves three general steps: capsule formation, capsule wall hardening, and isolation of the capsules [

93]. There are many possible techniques, which can be broadly categorized into chemical and physical processes. Physical processes can be further categorized into physico-chemical and physico-mechanical processes. A summary of microencapsulation techniques is shown in

Table 2. The techniques vary in process conditions and demands, encapsulation efficiency, shell thickness and permeability, capsule stability and release kinetics, and scalability. The appropriate technique for a certain application depends on the wall and core materials and the desired capsule properties, as well as production constraints.

Chemical microencapsulation processes involve covalent bond formation and include in-situ and interfacial polymerization techniques. In-situ polymerization is characterized by a lack of reactants in the core material [

101]. Suspension, dispersion, and emulsion polymerization are examples of radical in-situ polymerization techniques, whereby polymer shells are formed directly onto dispersed core particles by carrying out a polymerization reaction in the surrounding continuous phase. In suspension polymerization, the core material is dispersed in an immiscible aqueous continuous phase with monomer and initiator droplets, stabilized by macromolecular stabilizers, and vigorous agitation promotes polymerization to form capsules [

102]. In dispersion polymerization, the continuous phase is a poor solvent, such that swollen polymer particles precipitate to form capsules. In emulsion polymerization, an insoluble monomer is emulsified above critical micelle concentration in an aqueous continuous phase containing a soluble initiator and a surfactant, producing monomer-swollen micelles that form latex particles. Polycondensation can be an in-situ or interfacial process. This technique involves step-growth polymerization whereby a polymer shell forms around liquid or dispersed core material, either by deposition from a homogeneous solution (dispersion polycondensation) or by reaction at the interface between two immiscible phases (interfacial polycondensation) [

103].

Physico-chemical processes involve physical forces and phase changes rather than covalent bonds for the formation of capsule coatings. Coacervation is the first reported industrially-adopted microencapsulation technique and involves phase separation of a polymer solution, by concentration of coacervated particles, into a polymer-rich phase (coacervate) and a poor polymer phase (coacervation medium) [

92,

104]. In simple coacervation, a single polymer and a desolvation agent are used, while in complex coacervation, two oppositely charged polymers form a complex to create the shell. Layer-by-layer assembly involves repeated immersion of the core material into electrically charged particles, such as a polyelectrolyte solution, nanoparticles, ionic dyes, or metal ions, to build a shell [

92]. Sol-gel encapsulation forms a polymeric network shell through staged polymerization of a liquid-phase precursor that transitions to solid phase, trapping core material in the process [

105]. Supercritical fluid processes utilize supercritical fluids as solvent, antisolvent, or solute (swelling agent) of the shell material to induce controlled precipitation around the core material [

92]. Various techniques can be used, including rapid expansion of a supercritical fluid, gas anti-solvent, or particles from gas-saturated solution.

Physico-mechanical processes are equipment-driven and rely on mechanical forces. In spray-drying, an emulsion of core material particles in a solution of shell material is sprayed into a hot chamber such that the aqueous component evaporates and the shell material dries onto the core material particles [

104]. In fluid-bed coating, a coating material is sprayed onto a fluidized bed containing solid core material particles [

92]. The spinning-disk process involves a polymer solution containing suspended core material particles being poured into a rotating apparatus, from which coated particles are cast out by centrifugal force [

92]. Centrifugal extrusion involves co-extruding liquid core and wall materials through concentric nozzles on a rotating extrusion head to form a material rod, from which droplets break off as it is passed through a heat exchanger [

104].

Another method of microencapsulation is liposome entrapment. Fatty acid-based vesicles can self-assemble from lipids (commonly phospholipids) using various techniques, such as thin-film hydration, sonication, and extrusion [

94,

101]. Hydrophilic compounds are trapped within the core and hydrophobic material is trapped within the bilayer.

2.2.3. Materials

It is possible to use many different materials to produce microcapsules and the appropriate material depends on the desired properties and applications of the product. The shell material must be able to form a stable film that is chemically compatible and non-reactive (inert) with the core material and facilitates release of the core material under specific conditions. Properties of a good shell material include low viscosity, pliable, non-toxic, and water/solvent soluble or meltable. Additionally, the material should be economical, and the formed capsule should be easy to isolate from the reaction medium. A summary of synthetic and natural materials used in microencapsulation is shown in

Table 3.

Natural polymers can offer environmental benefits such as biodegradability, renewability, and non-toxicity. Additionally, many natural polymers offer higher selectivity, reactivity, and efficiency compared to synthetic polymers [

95]. They can also have superior properties with regards to high surface area, ease of synthesis, and high elasticity. Many are also bioactive or naturally antibacterial, and their biocompatibility and high bioadhesivity makes them suitable for medical applications [

106]. Additionally, when applied to textiles, biopolymeric microcapsules do not change textile properties such as breathability, softness, or structural integrity [

95]. However, biopolymeric microcapsules are more susceptible to unwanted degradation via natural media, mechanical agitation, photodegradation, or other mechanisms.

The core material of microcapsules can contain many active compounds. These include perfumes, fragrances, deodorants, and laundry compounds for sustained scent release in functional fabrics [

107,

108]; dyes, inks, and pigments to prevent leaching or allow active coloration [

101,

109]; insect repellents for protective textiles [

110]; flame retardants to enhance fire safety in materials [

111]; fertilizers and pesticides for slow-release in agriculture [

76]; and antimicrobials, antioxidants, antibiotics, antiseptics, antibodies, and drugs for bioactive textiles or intelligent packaging [

112,

113,

114]. Cosmetic ingredients such as vitamins, moisturizers, retinoids, steroids, caffeine, and plant extracts can be encapsulated to improve stability and skin penetration in cosmetic formulations or for application to cosmetotextiles [

97]. Catalysts, monomers, crosslinkers, curing agents, and plasticizers can be used for self-healing materials and advanced manufacturing [

115]. Phase change materials, like paraffins, are also commonly microencapsulated to regulate temperature by absorbing or releasing heat through phase changes and to control heat flux [

93,

116].

2.2.4. Release Mechanisms

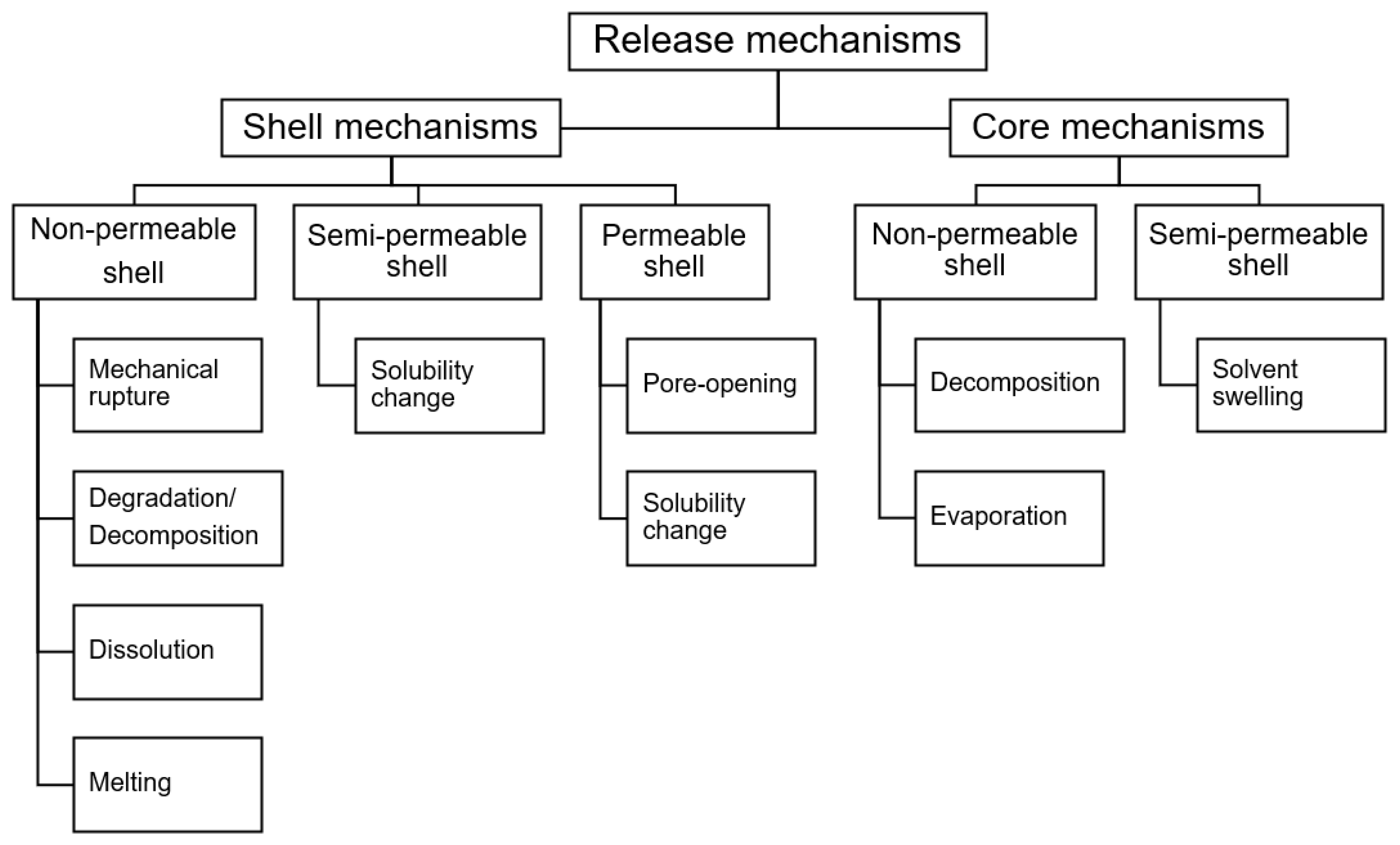

Release of the core material from microcapsules can be the result of a wide range of mechanisms. In general, release can be triggered by a change in the shell material or by a change in the core material. There are different release mechanisms depending on the nature of the shell – non-permeable, semi-permeable, or permeable – and these are summarized in

Figure 12. Exposure to various stimulus can trigger one or more of these release mechanisms to occur, allowing the core material to release into the external environment. Microcapsules that respond to specific stimuli with appropriate sensitivity, reaction rate, and release profile are desirable for commercial applications such as fragrance release, drug delivery, smart sensors, self-healing coatings, and functional textiles.

Mechanical Force

External applied mechanical forces such as friction, shear, or pressure can cause shell rupture. Additionally, internal pressure can be generated by contraction of the shell material or decomposition, evaporation, or swelling of the core material. Internal pressure created by any of these mechanisms can cause microcapsules to burst, releasing contents to the environment.

Chemicals and Biomolecules

Exposure to solvent can cause dissolution of a non-permeable shell or diffusion through a semi-permeable shell that causes core swelling and subsequent shell rupture. A change in pH can cause hydrolysis of pH-sensitive moieties in the shell, such as hydrazone, acetal, and β-carboxylic amide functional groups [

59]. This can alter crosslinking density and degrade the shell material. Additionally, pH can cause swelling or shrinking in hydrogel materials, as discussed in

Section 2.1.2. Therefore, microcapsules with hydrogel shells can experience a change in shell permeability based on pH. Similarly, high ionic strength can cause shrinking of polyelectrolytes shells [

117]. Swollen permeable and semi-permeable shells have a higher rates of release/diffusion, while the permeability of shrunken shells is decreased [

57]. Enzymatic activity can trigger the release of core material from microcapsules via enzymatic reduction, dissociation, or digestion that causes degradation of the shell [

118,

119]. Shell degradation can also be caused by oxidative cleavage of certain functional groups, such as boronic esters/acids and thioketals/thioacetals, by reactive oxygen species [

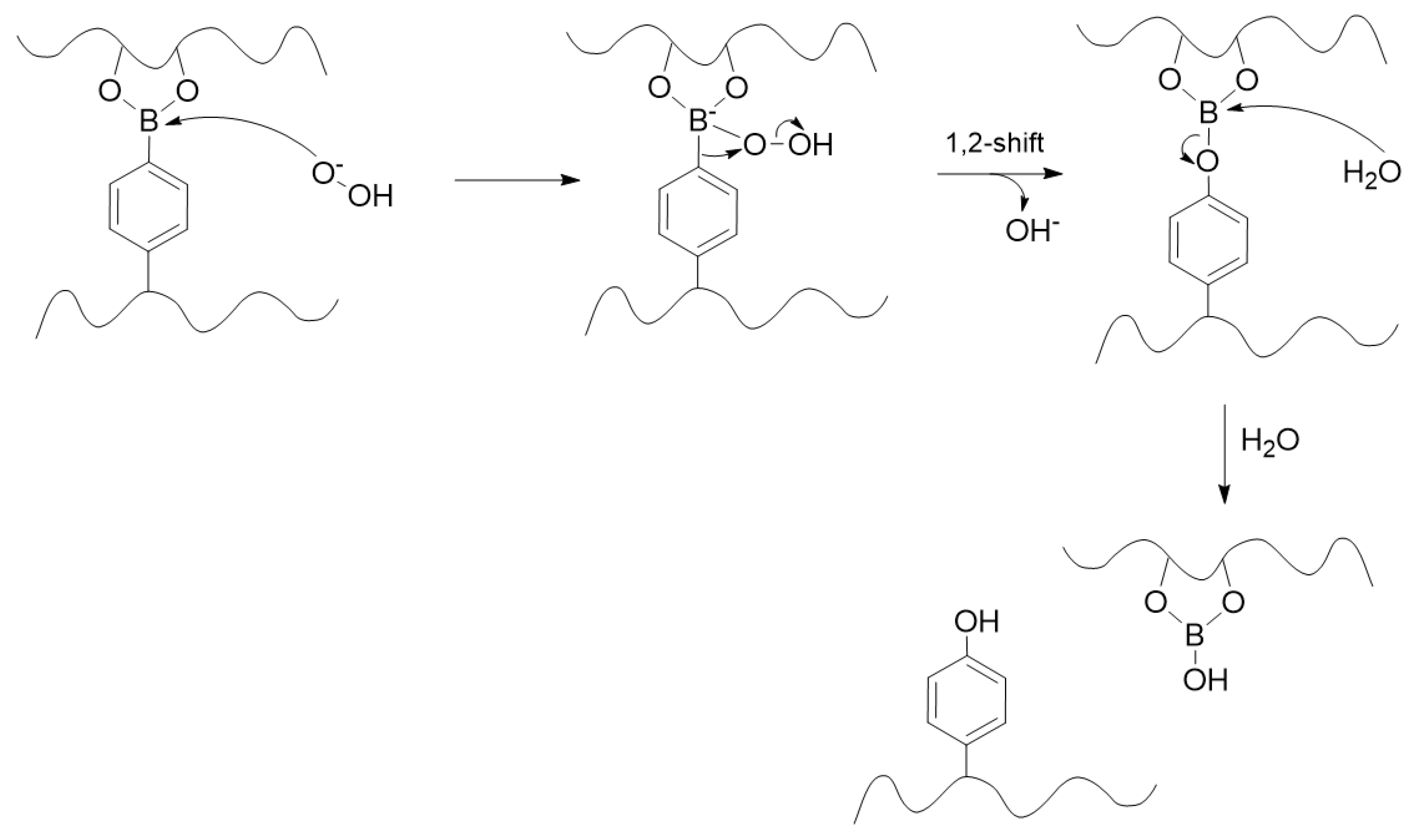

59].

Figure 13.

Example of chemical degradation of a polymer shell material by reactive oxygen species – oxidative cleavage of boronic ester crosslinks by hydrogen peroxide.

Figure 13.

Example of chemical degradation of a polymer shell material by reactive oxygen species – oxidative cleavage of boronic ester crosslinks by hydrogen peroxide.

Temperature

Shells composed of thermosensitive polymers undergo changes in permeability depending on temperature. For example, a shell made of PNIPAAm will be permeable below LCST when it is swollen, but above LCST, the chains will collapse such that the shell shrinks and its permeability decreases [

120]. This can be attributed to a change in the hydration state of PNIPAAm, which has hydrophilic character below LCST and hydrophobic character above LCST [

59]. Another approach is to graft thermosensitive polymers onto pores of permeable shells, which will lead to the inverse response. Below LCST, the polymer chains will be swollen, acting as a barrier to block diffusion through the pores. Above LCST, the polymer will collapse, opening the pores and allowing diffusion/release of the core material [

121]. Other temperature-related responses are melting or burning of the shell material [

104,

122].

Light

Shells composed of photosensitive compounds can undergo various release mechanisms. Upon exposure to UV light, azobenzene photoisomerizes from trans (nonpolar) to cis (polar) conformation. Shells containing azobenzene dissociate upon UV exposure [

59]. Spiropyran (nonpolar) photoisomerizes to merocyanine (Zwitterionic) under UV light; therefore, shells containing spiropyran rupture or increase in permeability when exposed to UV [

123]. Photolabile moieties such as o-nitrobenzyl ether derivates, coumarin derivatives, allyl disulfides, and Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes will undergo bond cleavage in response to light, resulting in degradation of the shell [

74,

75]. Temperature-induced changes in shells made of thermosensitive polymers can be triggered by photothermal conversion by light absorbing compounds or localized heating from laser irradiation [

76,

77,

124].

Electric and Magnetic Fields

Directional movement or oscillation of charged/magnetic species in shell materials can cause disintegration of the shells, releasing core material [

125].

2.2.5. Modifying Release Behavior

Responsive release behavior can be tailored to fit specific applications by altering the composition of the microcapsules. Shells with higher porosity will have higher rates of release because the core compound can diffuse through the pores. Shells composed of higher molecular weight polymers contain more dense polymeric networks and therefore smaller pores, resulting in slower release of core material [

126]. Increased shell thickness, achieved by increasing the mass of shell material or by using layer-by-layer assembly, will also lower release rate [

91]. Chemical interactions can also modify release behavior. For example, chemical incompatibility between shell and core materials will reduce permeation of the core material and will preferentially lead to wetting of the shell wall by the external continuous phase. Additionally, microcapsules with core conditions similar to the environmental conditions to which the capsules are exposed will exhibit higher release rates [

116]. In microcapsules with responsive polymers grafted onto pores in the shell material, higher graft density will result in slower rate of release.

For shells composed of hydrogel, higher crystallinity or crosslinking density will result in lower rates of release due to limited swelling capacity of the hydrogel [

116]. The hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of the hydrogel network impacts its affinity towards water, influencing release rate in aqueous systems [

1]. The choice and ratio of crosslinking agent also influence the swelling behavior of the shell; for example, alginate crosslinked with calcium ions will have stronger crosslinks than alginate crosslinked with magnesium ions due to stronger interactions with the guluronic acid groups in the polymer chains [

127].

2.3. Microencapsulation in Textiles

2.3.1. Role of Microcapsules in Textiles

Microencapsulation can extend the useful life of active textiles by controlling the release of active compounds. Furthermore, fibers can directly absorb microcapsules without impacting the original feel or properties of the material, unlike bulk coatings and finishes. These reasons, combined with the many benefits of microencapsulation discussed in

Section 2.2.1, have led to the development of microcapsules for textile applications over the past several decades.

In 1971, Lockheed Missiles and Space Co. was contracted by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to evaluate microencapsulated phase change materials (PCMs) for thermoregulating spacesuits [

128]. PCM textile coatings and fibers were later developed for NASA by the Triangle Research and Development Corporation (TRDC) and this technology was adopted by Outlast Technologies in the 1990s for thermoregulating consumer apparel including ski gear and bedding [

129]. Academic research of microencapsulation for textile materials was pioneered by Gordon Nelson in the 1990s, who developed microcapsules using yeast for textile treatment [

130]. Meanwhile, microencapsulation was adopted to encapsulate fragrances and skin softeners in clothing, then expanded to include vitamins, dyes, insect repellents, medicinal ingredients, and mothproofing agents [

131,

132].

2.3.2. Integration of Microcapsules into Textile Materials

Microcapsules can be applied to many different textile substrates, including natural fibers such as cotton, wool, silk, or flax, and synthetic fibers such as polyester or polyamides [

116]. The most common method of integrating microcapsules into textile materials is surface application, which includes various processes, such as coating, spraying, padding, printing, stamping, impregnation, and exhaustion [

95]. Coating involves deposition of microcapsules onto fabric using a coating medium, which can be solution, foam, paste, melt, powder, or granulate. Spraying involves application of microcapsules through a spray nozzle. In the padding process, fabric is placed into a bath containing microcapsules, then passed through squeeze rolls to remove excess solution. In printing, fabric is passed through a rotary screen attached to a rotary roll with printing paste containing microcapsules. Microcapsules can also be applied to fabric during the rinse cycle when washing [

116].

To improve bonding between fabric substrate and microcapsules, crosslinkers are often added to the application medium. Crosslinkers – commonly polycarboxylic acids – form covalent bonds between the fibers and microcapsule walls [

93]. Another method is pre-activation of the fabric so that reactive shells can bond covalently or ionically to the fibers [

116]. Pre-activation is suitable for charged fibers like chitosan and can impart ionic character to uncharged fibers. This can be achieved through chemical functionalization or plasma pretreatment. Chemical functionalization is a chemical method whereby charged functional groups are imparted onto the fibers. Anionic character can be generated through carboxymethylation via treatment with caustic soda then an aqueous sodium salt of monochloroacetic acid [

133]. Cationic character can be generated through aminisation, which involves dying the fabric with a reactive dye and subsequent reductive cleavage of the dye molecules to form aromatic amines. Alternatively, plasma pretreatment is a physical method of forming active sites (radicals, ions, etc.) on the fiber surface using gases such as air, nitrogen, or argon [

28,

134]. Etches are created in the fabric, increasing the roughness and surface area of the fibers to increase uptake [

23]. This method is generally regarded as more environmentally friendly than chemical pre-activation methods because there are no chemicals or solvents involved and the process is conducted at low temperatures.

Binders, including starch, acrylic, polyurethane, or silicone, can be used to increase the longevity of the microcapsules through wear and wash cycles [

116]. A binder acts as a film that forms atop the textile substrate, within which the microcapsules are embedded. Therefore, the microcapsules do not bind directly to the fabric, which can help preserve the surface characteristics of the fabric [

132]. When the microcapsules are fully embedded within the film, a sustained release profile is achieved, while partial embedment increases susceptibility of the microcapsules to mechanical or environmental triggers and results in a more “burst”-like release profile [

116]. Binders, however, can hinder release of the core compound from microcapsules [

93].

Surface application of microcapsules to textiles requires curing of the application medium. This process traditionally uses heat, exposing the fabric to temperatures of 130–170 °C for 1–10 minutes [

135]. However, high temperatures can damage microcapsules, particularly if the core material swells or volatilizes causing rupture of the microcapsule walls. An alternative curing method is UV curing, whereby a UV-curable resin containing oligomers, monomers, photoinitiators, and microcapsules is applied to the fabric. UV light polymerizes the resin components to fix the capsules within a continuous film layer on the fabric. This method is generally more durable than heat curing.

Functionalized fibers are an alternative method of incorporating microcapsules into textile materials, involving direct incorporation of the microcapsules between fibers or within the fibrous structure, rather than surface application. Various techniques can be used to achieve functionalized fibers. Microcapsules can be incorporated into the fibers during the spinning process, for example, by mixing into the spinning dope or polymer melt during wet or melt spinning [

132]. Composite fibers can also be accomplished with electrospinning or microfluidic techniques [

136,

137]. A common functionalized fiber structure is core-sheath, with either the core or the sheath containing microcapsules. Fiber diameter and microcapsule loading rate influence the release behavior of microcapsules from functionalized fibers.

2.3.3. Microencapsulation for Stimuli-Responsive Textiles

Microcapsules have been applied to textiles in a broad range of applications. Specifically, microcapsules with stimuli-responsive release behavior are reviewed in a textile context. A summary of the main applications and materials is provided in

Table 4, including references to studies that explicitly outline stimuli-responsive behavior of their microcapsules. As discussed in

Section 2.3.1, one of the earliest applications of microcapsules to textiles was for thermoregulating fabrics. In an early academic publication using this technology, Kim and Cho at Yonsei University applied octadecane-containing microcapsules with urea shells to polyester fabrics [

138]. This continues to be a common use of microencapsulation technology for smart textiles, utilizing microencapsulated PCMs to absorb, store, release, and deposit thermal energy from the textiles during phase changes [

139]. This technology has been applied to sportswear, extreme weather gear, ski boots, motorcycle helmets, automotive seat covers, protective garments, firefighter suits, medical textiles, bandages, and bedding [

140].

Another type of stimuli-responsive microcapsules in which the active compound itself is stimuli-responsive, rather than demonstrating stimuli-responsive release, is utilized in thermochromic and photochromic textiles. In such applications, thermochromic or photochromic dyes/pigments are encapsulated and applied to fabrics for stimuli-responsive coloration. This can be useful in environmental or healthcare monitoring, as well as smart fashion applications. Chowdhury et al. applied four encapsulated thermochromic pigments with different activation temperatures to conductive fabrics and applied voltage to increase temperature, yielding gradual color changes with the shifting reflectance spectra [

141]. More recently, Yang et al. at Xi’an Polytechnic University developed reversible dual-responsive color-changing fabrics using thermochromic microcapsules that responded to color and humidity changes due to the inclusion of humidity-sensitive discoloration materials [

142].

Fragrance release is common application of stimuli-responsive microcapsule release technology in textiles, with patented processes first emerging in the early 1990s. In 2009, Rodrigues et al. produced abrasion-release PUU microcapsules that retained fragrance up to 9000 abrasion cycles in laboratory impregnated fabrics and 3000 abrasion cycles in industrially impregnated fabrics [

98]. A recent study by Huo et al. developed dual-responsive microcapsules for thermal regulation and controlled fragrance release in textiles [

143]. The microcapsules contained PCMs and essential oils within a lotus seedpod-like dual-chamber structure that allowed stable fragrance diffusion through its micropores due to its thermoregulating ability. Extended release of fragrances in textiles has been thoroughly researched and adopted, but stimuli-responsive release is less common. In 2020, Lu et al. at the Chinese Academy of Sciences developed cationic liposomes with thermosensitive fragrance release behavior for application to silk [

144]. The liposomes, synthesized from self-assembly of poly[N-isopropylacrylamide-co-2-(dimethylamino)ethyl acrylate-phenylboronic acid], lipid molecules, cholesterol, and eugenol, interacted electrostatically with silk’s negative surface character. Chen et al. at Jiangnan University developed ethyl cellulose/silica hybrid microcapsules loaded with fragrance oil and grafted with UV absorbers and methacrylic acid [

145]. The microcapsules were added to waterborne polysiloxane resins for fabric coating, yielding fabrics with slow aromatic release and UV resistant properties.

Cosmetotextiles have also adopted microencapsulation technology to improve product lifetime. Among pioneering commercial cosmetotextiles utilizing microcapsules was the Skintex

® line from German textile chemical company Cognis. The Skintex

® range included moisturizing, cooling, energizing, relaxing, and mosquito repelling agents encapsulated with chitosan, with release triggered by friction with skin and enzymes present on skin [

97]. Other companies with early adoption of similar technology include Specialty Textile Product (BioCap biocapsule products) and Woolmark Development International Ltd. (Sensory Perception Technology). Microencapsulation technology is now widely used throughout moisturizers, sunscreens, retinoids, antioxidants, and products aimed at anti-aging, depigmenting, fighting inflammation, with cosmetotextiles being used to deliver such formulations [

146]. Many of these products are mechanically-responsive, but systems responding to other environmental triggers such as pH, temperature, humidity have been developed [

122,

147]. Academic studies are not included in

Table 4 because this area is dominated by product research and development the industrial sector.

Drug delivery textiles are another area of application for microcapsules, for products such as medical fabrics, wound dressings, sutures and tissue scaffolds [

146]. Electrospun functionalized fibers are particularly appropriate for tissue engineering due to the high level of control over fiber orientation and material properties afforded by electrospinning [

136]. Surface application of microcapsules to hospital garments can deliver antibacterial or other beneficial agents to patients or healthcare professionals during wear. Özsevinç and Alkan developed mechanical-responsive PU microcapsules containing medicinal lavender oil for neurological damage prevention for application to fabrics for palliative care or cancer patients [

148]. Zhao et al. at Tiangong University coated cotton fabric with hollow poly(allylamine hydrochloride)/poly(styrene sulfonate) microcapsules loaded with Rhodamine B as a model drug for pH-responsive release, based on the increased permeability of the polyelectrolyte shells at low pH [

149].

Table 4.

Summary of textile applications using stimuli-responsive microencapsulation technology.

Table 4.

Summary of textile applications using stimuli-responsive microencapsulation technology.

| Application |

Active compounds |

Reviews |

Studies |

| Thermoregulation |

Phase change materials (PCMs) |

[140,150] |

[138,143] |

| Colorants |

Dyes, pigments, thermo/photochromic compounds |

[101,132] |

[141,142] |

| Fragrance release |

Fragrance oils, perfumes, deodorants |

[125] |

[144,145] |

| Cosmetotextiles |

Moisturizers, vitamins, sunscreens, retinoids, antioxidants, cooling agents, antiaging agents, depigmenting agents, anticellulite agents, subcutaneous fat controllers |

[97,146,147] |

|

| Drug delivery |

Drugs, antibacterials, antifungals, essential oils, pain relief, blood circulation stimulants, itch suppression, decontamination/self-cleaning agents |

[112,151] |

[148,149] |

2.4. Hydrogel Microcapsules in Textiles

2.4.1. Introduction to Hydrogel Microcapsules

Hydrogel microcapsules can have hydrogel shells or cores. In either case, the hydrogel imparts stimuli-responsive behavior to the microcapsule. It is important to distinguish between hydrogel microcapsules, which contain a core surrounded by a shell, and microgels or nanogels, which are merely micro/nanosized hydrogel particles or spheres. In many respects, hydrogel microcapsules behave the same as any other microcapsule, protecting the core material from the environment and allowing for controlled or responsive release. However, traditional microcapsules made with rigid polymers do not exhibit swelling behavior, while hydrogel microcapsules are water-swollen and more sensitive to environmental stimuli. Therefore, hydrogel microcapsules are more responsive and can be more useful for targeted release behavior. In microcapsules with hydrogel shells, solute diffusion across a hydrogel membrane is dependent on solute size and concentration gradient, as well as hydrogel structure, pore size, and degree of swelling [

1]. In microcapsules with hydrogel cores, swelling of the core can cause shell rupture and release of active core compounds.

The high biocompatibility of hydrogel materials makes hydrogel microcapsules highly suitable for biomedicine. The first reported application of hydrogel microcapsules was investigation into treatment of diabetes with alginate encapsulated islet cells by Lim and Sun in 1980 [

152]. Hydrogel microcapsules are often used for tissue scaffolding by encapsulating cells due to their ability to mimic the composition of the extracellular matrix for cell growth [

153]. Stimuli-responsive behavior can then release cells for collection or replating. Hydrogel microcapsules are also used for cell transplantation, isolating implant cells from the external environment while allowing small molecules needed for cell survival to permeate through the hydrogel membrane [

154]. Host antibodies and immune cells cannot permeate the microcapsule membrane, removing the need for patient immunosuppressive therapy during transplantation [

153]. Additionally, transplanted cells can express therapeutic bioactive molecules as they remain sustained and protected within the host, avoiding the need to modify the host genome to treat disease [

155]. Location-targeted cell or drug delivery is also possible with stimuli-responsive hydrogel microcapsules, protecting the active compound from the harsh environment of the stomach and releasing it in the intestinal tract, for example [

156]. Sustained or stimuli-responsive drug delivery with hydrogel microcapsules can improve therapeutic efficiency [

157]. Therefore, it is evident that hydrogel microcapsules provide great utility in biomedical applications.

2.4.2. Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogel Microcapsules

Hydrogel microcapsules display a combination of the stimuli-responsive behavior of hydrogel materials described in

Section 2.1.2 and the microcapsule release mechanisms described in

Section 2.2.4. This behavior can be leveraged for a variety of applications, including the biomedical applications explored above, and may be tailored to fit specific requirements. This can be done through modifying the permeability of hydrogel shells with crosslinking or changing the strength of interactions within the shell, for example, by changing polymer hydrophobicity or incorporating polyions into the network [

58,

117,

158]. Many of the approaches for modifying the release behavior of traditional microcapsules can also be applied to hydrogel microcapsules. The tunability of hydrogel microcapsule release behavior is demonstrated in the PNIPAAm/ PEGDA hydrogel microcapsules with a thin oil layer developed by Jeong et al. [

159]. At high temperature, simultaneous shrinking of the hydrogel shell and expansion of the aqueous core layer increased internal microcapsule pressure, thereby destabilizing the oil layer and allowing release of core material. The release behavior was customized by modifying the shell thickness and crosslinking density, allowing precise control of release temperature. Furthermore, incorporation of gold nanorods allowed for non-invasive stimulation of release with near-infrared light illumination, through photothermal conversion effects.

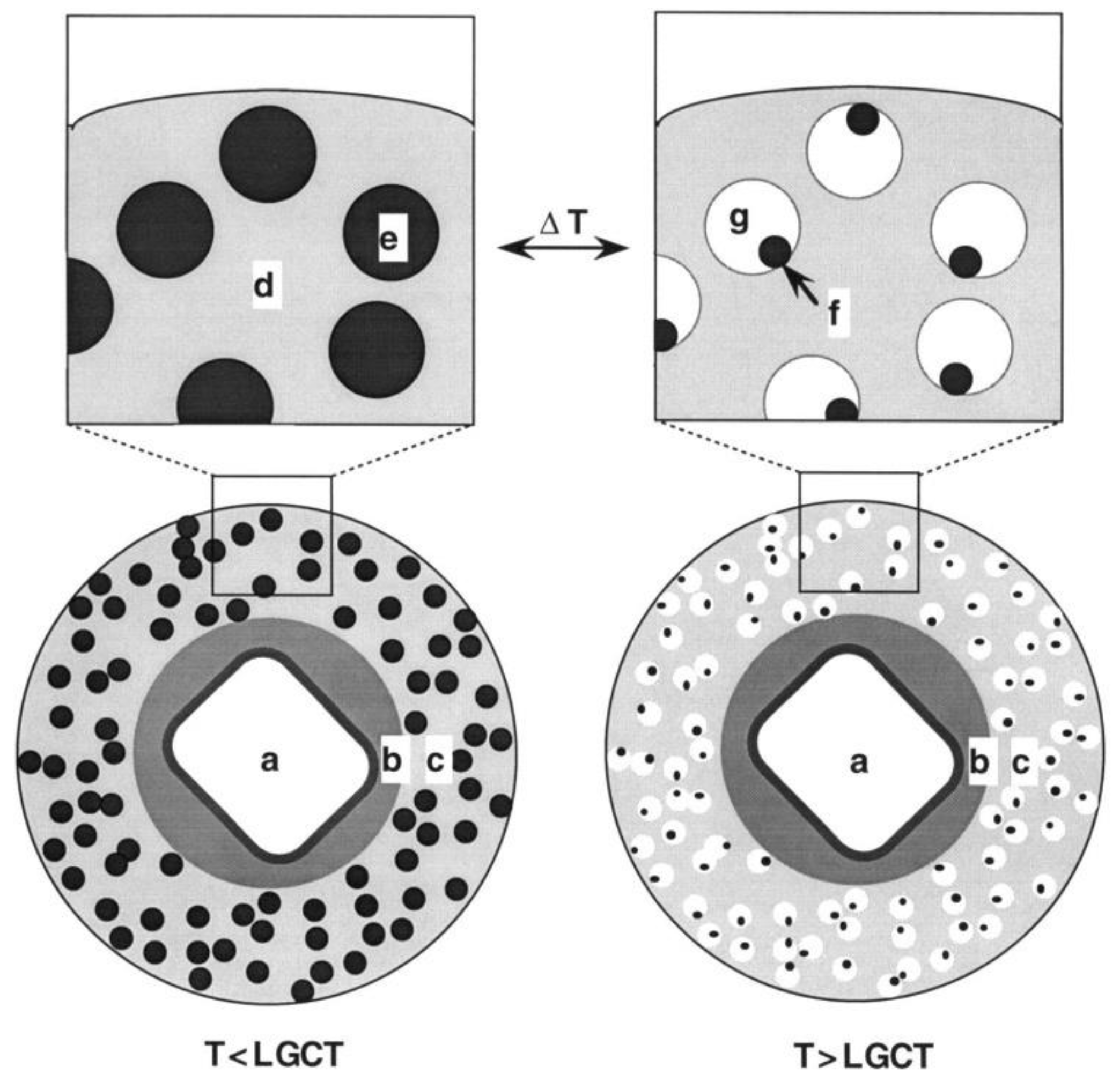

Ichikawa and Fukumori developed hydrogel microcapsules for thermosensitive drug release with “on-off” pulsatile controllability [

160]. The shells were composed of an ethylcellulose matrix containing nano-sized hydrogel particles with PNIPAAm shells. The hydrogel nanoparticles experienced thermally induced shrinking at high temperatures, leaving voids in the microcapsule shells through which the drug could diffuse. An illustration of the microcapsule design depicting behavior above and below lower gel collapse temperature (LGCT) is shown in

Figure 14. This temperature dependent release could be switched between “on” and “off” states within the order of a minute and was reversible and reproducible. pH-sensitive release is highly relevant for oral drug delivery applications due to the differences in pH throughout the digestive tract. Jeon et al. at Pohang University of Science and Technology recently achieved pH-responsive release of proteins from hydrogen-bonded PPO/PMAA hydrogel microcapsules [

126]. The microcapsules released encapsulated proteins above pH of 5 upon ionization of PMAA and consequential rapid dissociation of the shells. The microcapsules were stable at high salt concentrations and release behavior was tunable by modifying PMAA molecular weight.

Multi-stimuli-responsive hydrogel microcapsules have also been developed for drug delivery. Wei et al. at Sichuan University fabricated microcapsules with shells composed of chitosan with embedded superparamagnetic nanoparticles and PNIPAAm/PAAm sub-microspheres [