1. Introduction

Trypanosomiasis caused by

Trypanosoma vivax is a major constraint to livestock production in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and Latin America [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The parasite is transmitted either cyclically by tsetse flies (

Glossina spp.) in endemic areas of Africa or mechanically by hematophagous flies, such as

Tabanus spp. and

Stomoxys calcitrans, as well as through iatrogenic practices in tsetse-free regions [

3,

4,

7]. The disease is characterized by fever, anemia, weight loss, reduced fertility, and decreased milk and meat productivity, with severe economic losses for rural communities [

3,

4].

Although cattle are traditionally considered the primary domestic hosts of

T. vivax, water buffaloes (

Bubalus bubalis) are increasingly recognized as susceptible and clinically affected [

5,

8]. Buffaloes are essential for meat and dairy production in several tropical countries, and in regions such as the Brazilian Amazon, particularly on Marajó Island, they represent the main livestock resource [

9,

10,

11]. Outbreaks of acute trypanosomiasis in buffaloes have been associated with high morbidity and mortality, while chronic and subclinical infections make this species reservoirs, silently sustaining the transmission of the parasite, in the region, to other susceptible ruminants [

7,

12]. This dual role of buffaloes as productive animals and potential carriers highlights the importance of understanding the epidemiological (

Table 1) and immunopathological aspects of

T. vivax in this species.

Pathogenesis in buffaloes remains incompletely understood but involves complex host–parasite interactions. Antigenic variation mediated by variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs) allows immune evasion, contributing to persistent parasitemia and relapses [

14,

15,

16]. In addition, profound anemia, immunosuppression, and occasional neurological signs have been described, with direct consequences for productivity and animal welfare [

5,

8]. Despite advances in molecular biology, diagnostic limitations remain a challenge in endemic regions, particularly for detecting chronic carriers and differentiating

T. vivax from other trypanosomes [

3,

4].

Therapeutic and control strategies are also limited. Diminazene aceturate and isometamidium chloride remain the main trypanocides available, but reports of treatment failure and resistance are increasing, especially in cattle [

8,

13,

17,

18]. Preventive measures rely primarily on vector control and improved management practices, yet these approaches are often difficult to sustain in Amazonian floodplain environments [

16]. Furthermore, there is no effective vaccine available, despite ongoing research exploring invariant antigens and novel immunization strategies [

19,

20].

Despite substantial progress, several knowledge gaps still limit progress toward evidence-based management in buffalo herds. First, immuno-pathological models and longitudinal studies specifically designed for water buffaloes remain scarce, which constrains mechanistic understanding of chronic carriage and relapse dynamics. Second, the global epidemiological contribution of buffaloes as reservoirs is likely underestimated due to underdiagnosis of low-parasitemia infections and limited surveillance in mixed-species production systems. Third, robust, buffa-lo-specific economic assessments are still limited, hindering accurate quantification of losses and cost-effectiveness analyses of integrated control strategies. To our knowledge, this is the first review specifically dedicated to T. vivax in water buffaloes integrating molecular, epidemiological, diagnostic, and control perspectives with emphasis on the Amazon biome. Given these challenges, a comprehensive review focusing on T. vivax in water buffaloes is timely and necessary. By synthesizing available knowledge on pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and integrated control, with particular emphasis on the Amazon Biome, this article aims to provide veterinarians, researchers, and policymakers with critical insights for surveillance and sustainable disease management in buffalo production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

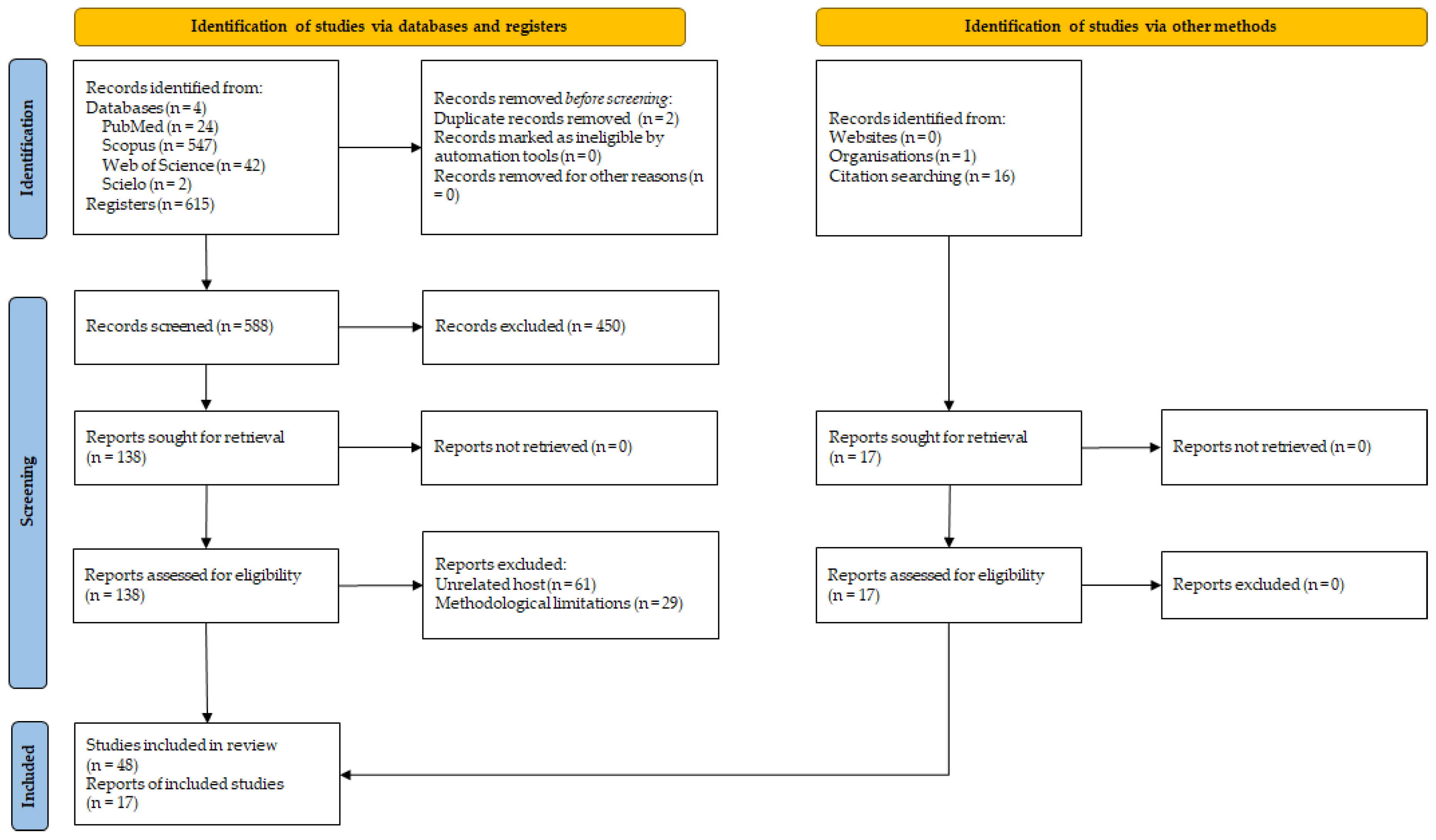

This review was designed as a narrative synthesis strengthened by a structured scoping methodology, guided by the SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) tool and adapted to the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – Scoping Reviews) framework [

21,

22]. A comprehensive search was conducted between January and December 2025 in PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science and SciELO, complemented by manual screening the reference lists of included studies to minimize omission of relevant evidence. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH/DeCS) and free-text keywords, using the Boolean string (“

Trypanosoma vivax” or “

T. vivax”) and (“buffaloes” or “buffalo” or “water buffaloes” or “

Bubalus bubalis”), with publications restricted to the years 2000–2025.

No language restrictions were initially applied, but only studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish were eligible. Inclusion criteria comprised original studies (experimental, clinical, epidemiological, molecular, or diagnostic) or well-documented outbreak reports directly addressing T. vivax infection in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis), whether naturally or experimentally infected, and providing information on pathogenesis, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, control, or economic impact. Exclusion criteria were studies exclusively on cattle, small ruminants, or wildlife without relevance to buffaloes; reports lacking confirmatory parasitological, serological, or molecular evidence; duplicates; inaccessible full texts; and non–peer-reviewed conference abstracts.

The initial search identified 615 records, which were reduced to 588 after duplicate removal. Following title and abstract screening, 450 records were excluded, leaving 138 full texts assessed. Of these, 90 were excluded due to unsuitable host species or methodological limitations. Additionally, 17 studies were identified through other sources, including organizations and screening searching, resulting in a total of 65 studies that met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review. Two reviewers independently screened the articles, and disagreements were determined through consensus. For each study, the following data were extracted: year of publication, country or region, study design, host species, sample size, diagnostic method, main outcomes, and specific relevance to buffalo’s trypanosomiasis.

The results were summarized descriptively and categorized into etiopathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical signs and necropsy findings, diagnosis, and control and prophylaxis. Tables and figures were employed, where appropriate, to facilitate comparison and clarity across studies. The screening and selection process are depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1). A scoping approach was selected because the available literature is highly heterogeneous in study design, diagnostic platforms, ecological contexts, and outcome reporting, which precludes a meaningful quantitative synthesis. Accordingly, mapping the breadth of evidence and critically contextualizing findings across regions and production systems was considered more appropriate than a classic systematic review with metanalysis.

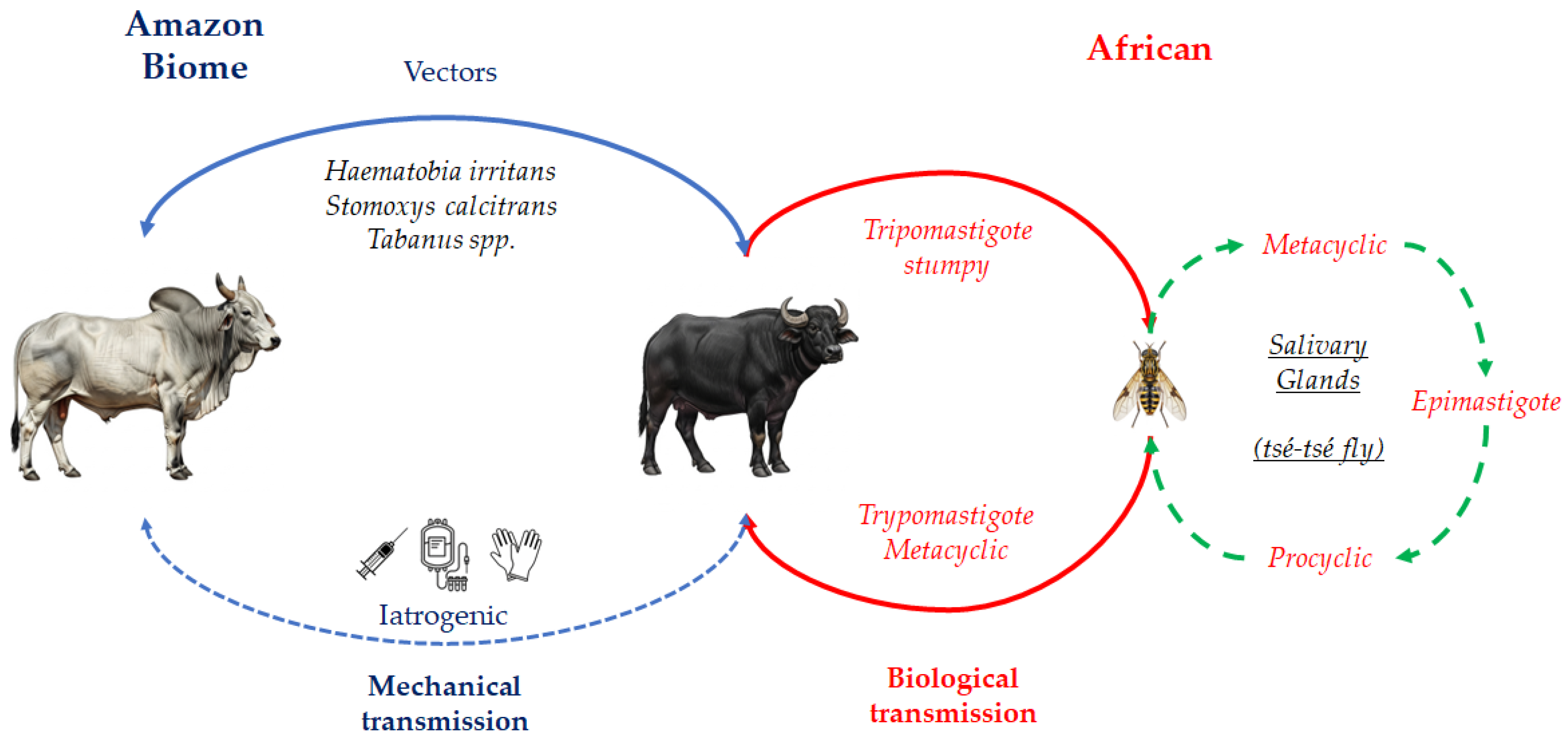

3. Etiopathogenesis

Trypanosoma vivax is a flagellated protozoan belonging to the class Kinetoplastida, family Trypanosomatidae, genus

Trypanosoma, and subgenus Duttonella [

2,

23]. This parasite can be transmitted in two main ways: biological transmission, which occurs in Africa, and mechanical transmission, which predominates in South America [

3,

13]. In the biological cycle,

T. vivax belongs to the Salivaria section, as the parasite develops in the salivary glands of the tsetse fly (

Glossina spp.), the main invertebrate host in Africa [

3,

13,

15]. Interestingly, Glossina flies, although central to biological transmission, may also contribute to mechanical spread. In Latin America, however, biting flies such as

Tabanus spp

., Haematobia irritans and

Stomoxys calcitrans are the most important mechanical vectors [

3]. Additionally, iatrogenic transmission has been reported, particularly through the reuse of contaminated needles and syringes during medical procedures or vaccination [

24]. Of special concern in buffalo dairy systems is the frequent use of shared needles for oxytocin administration in lactating buffalo cows prior to or during milking, which represents a critical biosecurity gap.

The life cycle of

T. vivax (

Figure 2) alternates between an invertebrate vector and a vertebrate host [

20]. In tsetse flies, the parasite develops exclusively in the proboscis, without undergoing a procyclic stage in the insect midgut and salivary glands [

25]. This characteristic distinguishes

T. vivax from other trypanosomes, such as

T. brucei and

T. congolense, which develop as procyclic forms in the tsetse gut [

15,

26]. Within the proboscis, trypomastigotes differentiate into epimastigotes and subsequently into metacyclic trypomastigotes, the infective stage transmitted to vertebrate hosts via insect bites [

13,

16]. This restricted developmental cycle may explain why mechanical transmission by other hematophagous flies is feasible in the Americas [

26,

27]. Once transmitted, metacyclic trypomastigotes enter the host’s bloodstream, where they initially express metacyclic variant surface glycoproteins (mVSGs), providing the first defense against host antibodies [

14,

15,

16]. Inside the mammalian host, the trypomastigotes differentiate into three forms: slender, intermediate, and stumpy [

20]; these parasites rapidly transform into bloodstream trypomastigotes, which proliferate by binary fission and disseminate through blood, lymph nodes, and occasionally the cerebrospinal fluid. Their invasion of multiple tissues underlies the diverse clinical signs of animal trypanosomiasis [

16,

20,

28].

In mechanical transmission, vectors remain infective only for a limited period, and thus the frequency of fly bites combined with the level of parasitemia in the reservoir host are decisive factors for successful transmission [

13,

29]. The prepatent period of

T. vivax infection varies depending on both the host species and the parasite isolate, and parasitemia often follows irregular daily fluctuations [

13]. Another way of mechanical transmission can occur through the use of reused needles or syringes in the herd to collect blood samples or administer medications. This is a common management condition on farms in Brazil, but not recommended. Blood transfusions and the use of tools that scarify the skin of buffaloes also have the potential to transmit

T. vivax, but this is not a significant epidemiological condition. Reused needles or syringes used across multiple animals can become contaminated, facilitating the spread of

T. vivax. Research indicates that infection rates can reach 30% via subcutaneous injection, 50% through intramuscular injection, and up to 80% via intravenous injection when contaminated needles are involved. Notably,

T. vivax can remain viable in certain substances such as foot-and-mouth disease vaccines for up to 20 hours, posing a significant risk during veterinary procedures [

20].

4. Epidemiology

4.1. Geographic Distribution and Transmission Routes

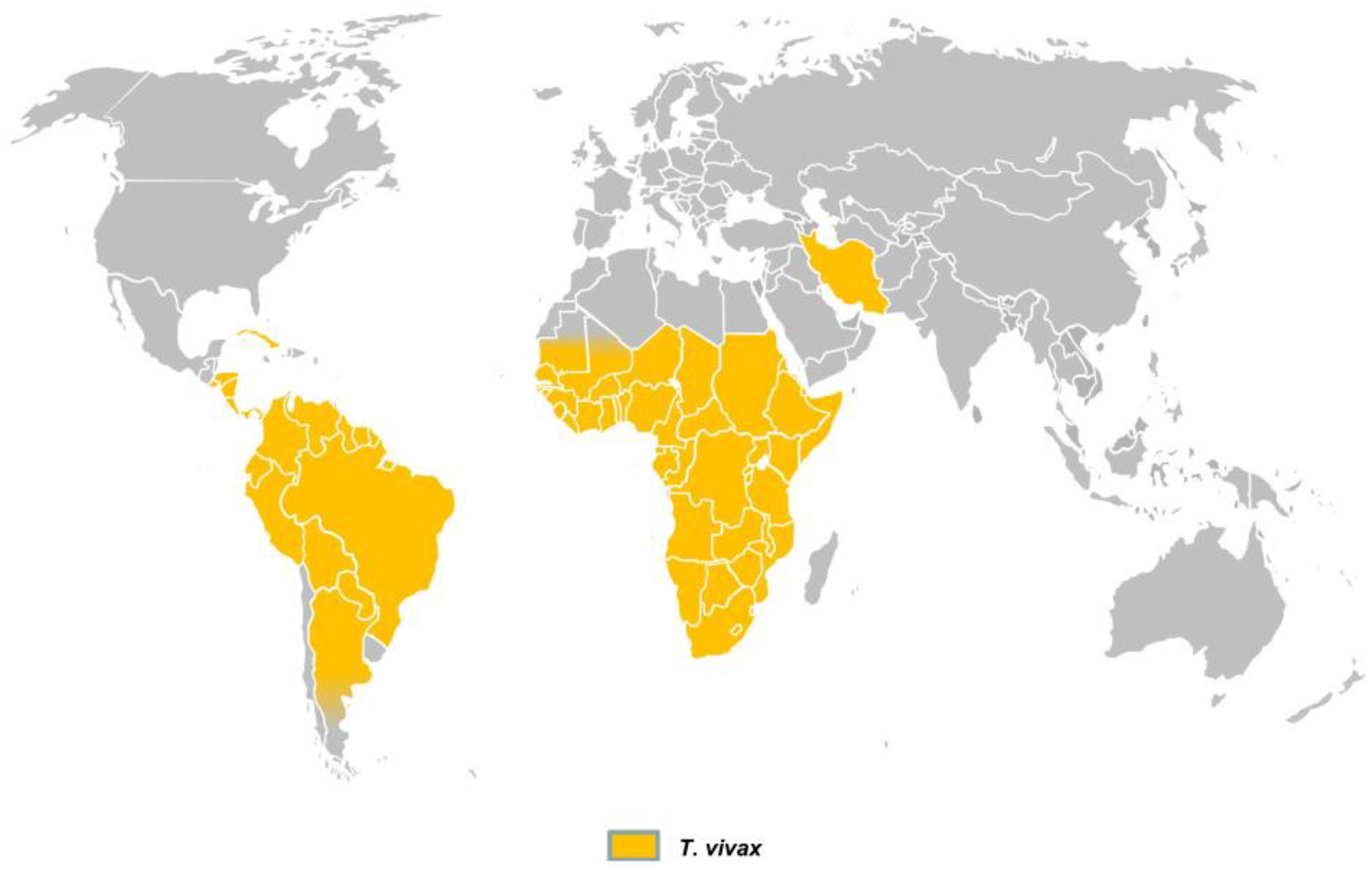

Trypanosoma vivax is originally from Africa, where its biological cycle involves cyclical transmission by tsetse flies (

Glossina spp.). However, the parasite has now spread to Latin America and the Caribbean [

7,

20], where mechanical transmission represents the critical factor for its dissemination and persistence in regions without tsetse flies [

13,

30]. In a comprehensive review on the diagnosis of animal trypanosomoses, Desquesnes et al. [

2] presented the global distribution of

T. vivax (

Figure 3), which currently includes most countries in South and Central America, large areas of sub-Saharan Africa, and, more recently, reports from Iran. In Central and South America, mechanical transmission is mainly associated with biting flies such as

Tabanus spp.,

Stomoxys calcitrans and

Haematobia irritans [

3,

31]. Although

T. vivax DNA has also been detected in ticks (

Amblyomma cajennense,

Rhipicephalus microplus) and in the buffalo louse

Haematopinus tuberculatus, there is no scientific evidence to date that these ectoparasites play an epidemiological role in transmission and in the state of Pará, Brazil, especially on Marajó Island, high infestation on buffaloes by this louse is common [

4].

4.2. Reservoir Role and Endemic Stability

This parasite infects both wild and domestic ungulates, including buffaloes, cattle, sheep, and goats [

13,

32], as well as camels, donkeys and even suids [

2,

31]. In Africa, several wild ruminants, especially the African buffalo (

Syncerus caffer), are considered important reservoirs. In contrast, no wild reservoirs have been reported in South America [

8,

31]. Among domestic species, buffaloes often act as healthy carriers, similar to cattle and goats, particularly when chronically infected [

8,

33]. These changes in parasitemia are associated with the host’s immune reaction, the antigenic shifts in the surface variant glycoproteins of trypanosomes, seasonal variations and parasite traits [

34,

35]. These asymptomatic animals are epidemiologically relevant because they can silently disseminate

T. vivax into herds and regions where no clinical cases are apparent [

3,

31], principally from endemic regions without prior quarantine or performing diagnostic tests. Pérez et al. [

5] further demonstrated that buffaloes and cattle may present high infection rates, acting as subclinical carriers, and that co-infections with other trypanosomes, such as

T. theileri, can occur.

4.3. Seasonality, Risk Factors, and Prevalence Heterogeneity

Several South American countries, including Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, and Bolivia, are now regarded as endemic areas for

T. vivax [

5,

8]. Amazonian lowlands, Venezuelan Llanos and the Brazilian Pantanal are considered regions of enzootic stability of

T. vivax infections [

36]. In the Brazilian Amazon, particularly in the Lower Amazon region and Marajó Island, the combination of buffalo and cattle rearing under floodplain (

várzea) and upland pasture systems at high stocking densities creates favorable conditions for intense exposure to hematophagous flies, maintaining trypanosomiasis endemicity [

5]. Flooded environments in

várzea pastures further increase vector density, thereby reinforcing transmission [

16]. Under such endemic conditions, buffaloes often harbor chronic, low to moderate parasitemia, controlled by continuous immune exposure, characterizing a state of enzootic stability [

5,

8,

27,

37,

38,

39]. Conversely, the climate variations seen in recent years may disturb this enzootic balance and trigger outbreaks in endemic areas [

39]. Furthermore, the prevalence of

T. vivax infection varies according to regions and different properties, ranging from 1.93% to 79.31% of infected buffalo (

Table 2) [

3,

4,

5,

8,

32,

39]. The highest prevalence values are in the rainy season (p<0.05), when biting flies are highly abundant, but there are reports of outbreaks in the dry season, in areas with severe drought (stress) [

8].

Interestingly, Serra et al. [

3] observed no statistical differences in antibody detection rates against

T. vivax across buffalo age groups, which contrasts with cattle, where older animals are generally more susceptible [

40,

41,

42]. Similarly, no significant age and sex-related differences were described in buffaloes [

43], but only one report indicates that younger buffaloes infected by

Trypanosoma sp., under 12 months of age, are more severely impacted [

44]. No differences between age and sex are common in other species [

40,

45,

46].

T. vivax prevalence in buffaloes varies considerably but tends to increase during rainy seasons, correlating with the greater transmission of

T. vivax due to the increase in the population of hematophagous flies during the rainy season and higher animal density [

8,

27,

37]. Although many infections remain asymptomatic, clinical disease may be triggered or reactivated by stressors such as thermal stress, poor nutrition, pregnancy, and lactation, or by co-infections with pathogens such as

Babesia spp. and

Anaplasma spp. [

5,

8]. These stressors compromise immune control, facilitating parasitemia escalation and leading to severe or even fatal outcomes of trypanosomiasis in buffalo herds [

8].

On the other hand, certain cattle breeds have been reported to possess natural resistance to trypanosomiasis referred to as trypanotolerant including

Bos taurus N’Dama, Muturu, and Dahomey, predominantly found in West Africa. In regions with a high risk of infection, these trypanotolerant cattle are able to maintain growth and reproductive performance [

13]. In African buffaloes, studies have shown that resistance to trypanosomiasis developed through evolutionary adaptation, involving the production of specific antibodies against variant surface glycoproteins (VSG) and the generation of trypanocidal H₂O₂ molecules that lead to the elimination of the parasite from the bloodstream [

47,

48]. Additionally, a study examining the expression patterns of IFN-γ and miRNA-125b in dairy buffaloes (

Bubalus bubalis) with and without

T. vivax infection revealed distinct gene expression profiles between infected and uninfected genotypes. Buffaloes positive for

T. vivax carrying the AA and GA genotypes appeared more susceptible to infection, exhibiting elevated IFN-γ levels and reduced miRNA-125b expression. In contrast, uninfected buffaloes with the GG genotype showed increased resistance to

T. vivax, characterized by higher expression of both IFN-γ and miRNA-125b, likely due to the G allele enhancing their regulatory interaction [

48].

A local example from the municipality of Soure on Marajó Island is provided in the Supplementary materials. The methodology and results are detailed and illustrated with figures in the

Supplementary Materials (

Figures S1 and S2), where they serve as illustrative examples rather than central evidence and do not form part of the evidence base for this review, thereby preserving consistency in the review structure.

4.4. Economic Impact and Evidence Gaps

Besides the destructive effects on animal health, trypanosomiasis results in significant financial losses for the dairy buffaloes industry, due to loss of condition, milk yield reduction and other factors [

49]

. In cattle, annual losses due to trypanosomiasis in Africa are estimated at USD 5 billion, with approximately USD 30 million spent on treatments [

7,

50,

51]. In Brazil, particularly in the Pantanal wetland a region with seasonal flooding comparable to Marajó Island losses exceeding USD 160 million have been estimated [

7,

52]. Although similar data are lacking for buffalo production, the analogy raises concern, especially for small to medium-scale farmers who dominate buffalo husbandry in the Amazon. In these settings, uncontrolled outbreaks of

T. vivax could seriously threaten the economic sustainability of buffalo farming.

5. Clinical Signs and Necropsy Findings

In endemic areas of

Trypanosoma vivax, water buffaloes may remain asymptomatic or develop a chronic course of infection with insidious progression of clinical signs. The most common manifestations include intermittent fever, progressive weight loss, anemia, and reproductive disorders such as abortion [

5,

8,

13]. The anemia, according to Guegan et al. [

53], implying an ex vivo assay to measure erythrophagocytosis throughout infection, demonstrated that trans-sialidase enzymes, released in the early stages, induce desalination of erythrocytes, leading to their phagocytosis and contributing to anemia. Furthermore, the same authors showed that erythrophagocytosis is responsible to the initial significant decline in hematocrit in the acute phase of infection. Concomitant stress factors, including nutritional deficits or co-infections, have been reported to exacerbate the clinical course and increase the likelihood of symptomatic disease [

8]. Importantly, the clinical presentation in buffaloes is generally similar to that observed in cattle and other ruminants, as seen sheep, indicating comparable patterns of disease expression across species [

13,

54,

55].

A well-documented outbreak described by Garcia et al. [

8] in buffaloes from the Venezuelan Llanos highlighted the occurrence of neurological involvement, which is less frequently reported in bovines. The most severely affected animals exhibited depression, muscle tremors, and severe ataxia, often characterized by dragging of the forelimbs. In this outbreak, the mortality rate reached 7% of the herd, considered high for trypanosomiasis, and cases persisted for nine months after the onset of clinical disease. The prolonged impact was likely aggravated by nutritional stress, stable fly infestations, and lack of preventive health measures, such as strategic deworming and ectoparasite control, which may have favored the severity of clinical signs and contributed to the observed mortality.

Regarding necropsy findings, carcasses of buffaloes clinically affected by

T. vivax trypanosomiasis are frequently described as edematous and markedly anemic [

13,

56]. In cattle, postmortem lesions are generally nonspecific and may include petechiae on serous membranes, lymphadenomegaly, splenomegaly, serous atrophy of fat, and evidence of systemic anemia [

16]. These observations highlight the need for confirmatory laboratory testing, as necropsy findings alone are not pathognomonic for the disease but may support clinical suspicion when correlated with epidemiological context and diagnostic results.

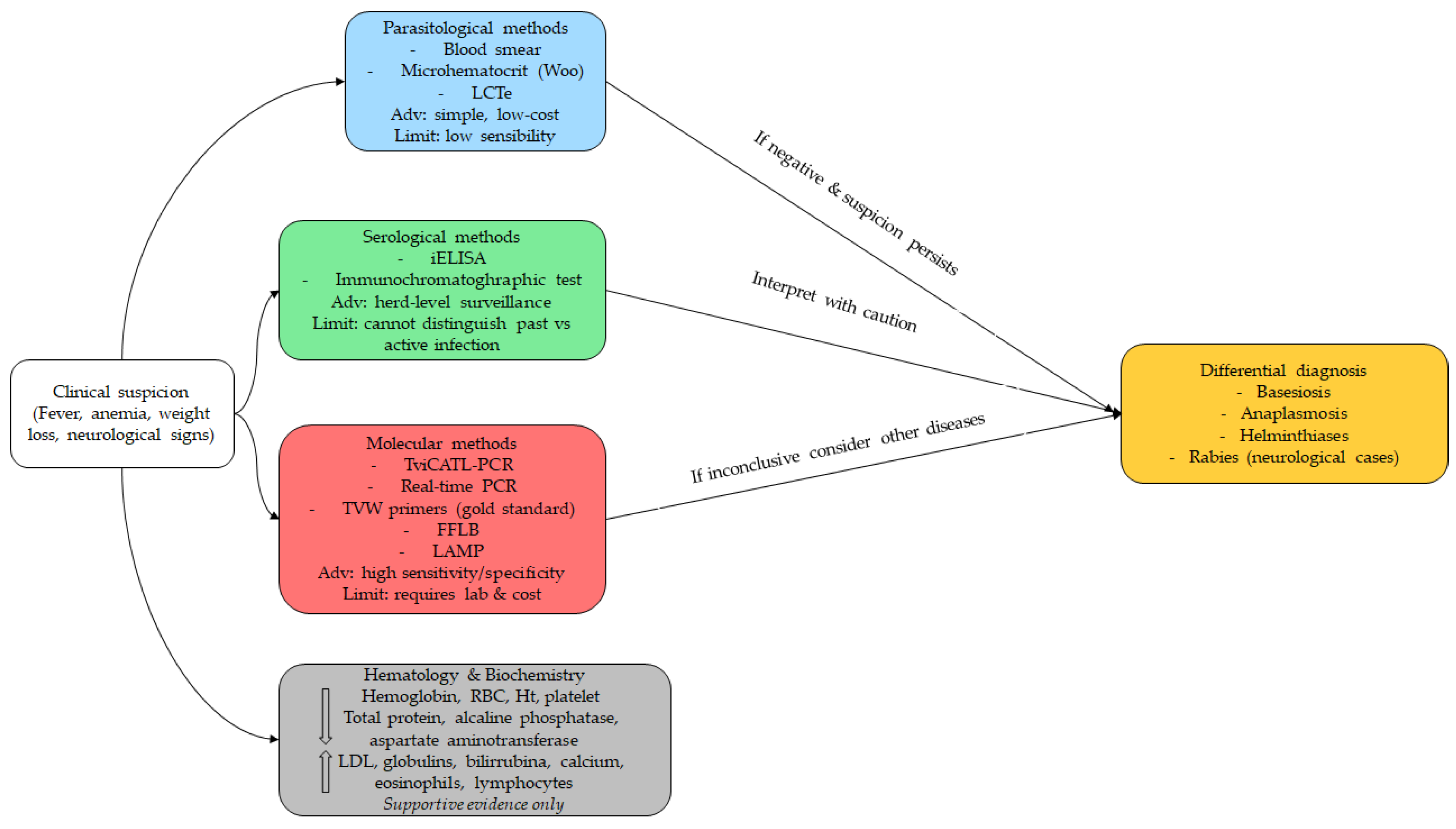

6. Diagnosis

6.1. Parasitological and Concentration Techniques

The diagnosis of trypanosomiasis caused by

Trypanosoma vivax in water buffaloes can be established through a combination of clinical examination and parasitological, serological, and molecular methods (

Table 3 and

Figure 4) [

2,

5]. Among parasitological tests, the blood smear remains the most widely used due to its simplicity, especially by the Woo technique [

56,

57], field applicability, and low cost. The first record of

T. vivax in the Brazilian Amazon was reported through blood smears from buffaloes on Marajó Island in 1972 by Shaw and Lainson [

12]. Peripheral blood samples collected from the tail base or ear tip are recommended for buffaloes [

3]. However, this method has significant limitations in terms of sensitivity and specificity, particularly in animals with low parasitemia or in asymptomatic carriers [

3,

4]. As an additional option with the use of peripheral blood samples, the “Lysis and Concentration Technique” (LCTe) enhances the chances of visualization in low parasitemia, because enhances the concentration of hemoprotozoa by eliminating red blood cells. Moreover, LCTe is highly cost-effective and simple to put both in laboratories and in field settings [

58].

6.2. Serological Surveillance

Serological techniques provide higher sensitivity in herd-level surveillance. Serra et al. [

3] reported that 79.31% (92/116) of buffaloes were seropositive by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA), while 76.72% (89/116) tested positive with an immunochromatographic assay (Imunotest®). These findings demonstrate that buffaloes are frequently exposed to

T. vivax, even at parasitemia levels undetectable by blood smears. Furthermore, antibody responses may persist for extended periods after infection, allowing detection even in animals with transient or subclinical infections [

44,

45]. The iELISA has been extensively applied in cattle and is considered highly sensitive, particularly in naturally infected animals [

60].

6.3. Molecular Diagnostics and Field-Adapted Platforms

Molecular methods have advanced the diagnosis of

T. vivax in buffaloes and their vectors [

3,

4] and are effective in identifying active infections during the chronic stage, when low parasitemia levels limit the effectiveness of traditional parasitological methods [

39]. Currently, three buffalo-derived sequences are deposited in GenBank (accessions OR339796, MK801872, MK801874), showing close phylogenetic relationships [

3]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is regarded as one of the most sensitive and specific diagnostic tools, requiring only small volumes of blood and being applicable to samples preserved at room temperature [

5,

8,

61]. Furthermore, real-time PCR can be applied to hosts and vectors with high sensitivity and specificity [

1]. Despite its advantages, false-negative outcomes may still arise when parasitemia is extremely low, as seen in chronic infections, when excessive DNA is added to the PCR reaction, or in the presence of inhibitory substances. Conversely, false-positive results can occur due to contamination from other positive samples [

1,

39]. As disadvantages

, PCR requires well-equipped laboratories, trained personnel, and high-quality DNA preparations with appropriate primers. Although more costly than parasitological methods, PCR offers substantial improvements in diagnostic accuracy [

2]. Specific assays include the TviCATL-PCR, described by Cortez et al. [

62], and the Fluorescent Fragment Length Barcoding (FFLB) test, both of which can successfully detect

T. vivax in buffaloes, even in ethanol-preserved samples without refrigeration [

5]. In addition, Desquesnes et al. [

2] highlighted the TVW primers as the gold standard for

T. vivax molecular detection.

Additionally, the Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) is notable as methodology using nucleic acid isothermal amplification assays in the detection of

T. vivax in blood samples of buffaloes naturally infected in the Brazilian Amazon, indicating that it represents a practical alternative to conventional molecular methods, with promising applications in epidemiological surveillance and effective clinical diagnosis [

39]. In LAMP, the isothermal amplification process permits diagnosis using basic equipment, such as a dry block heater or water bath, making it suitable for use in field diagnostics [

59]. Nevertheless, additional research is necessary to optimize LAMP protocols, simplifying result interpretation and supporting their integration into routine laboratory practice [

39].

6.4. Hematological and Biochemical Supportive Findings

Hematological and biochemical alterations further support the diagnosis of

T. vivax trypanosomiasis in buffaloes. Common findings include severe reductions in hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, red blood cell counts, creatinine, urea, and alkaline phosphatase, along with increased leukocyte counts, lactate dehydrogenase activity, globulin levels, and both total and indirect bilirubin [

63,

64,

65,

66]. In another way, natural

Trypanosoma spp. in water buffaloes’ infection resulted in statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), decreasing red blood cells, hemoglobin, pack cell volume, platelets and reduced concentrations of total protein, alkaline phosphatase, and aspartate aminotransferase. On the other hand, increases in eosinophils, lymphocites and serum calcium [

67]

.

Despite these advances, several diagnostic challenges persist, such as: (i) the need for adequately trained technical teams and fully equipped laboratories; (ii) limited availability of standardized commercial reagents; (iii) restricted access to advanced laboratory tests in endemic regions; and (iv) high costs of molecular assays [

2]. Therefore, progress in the diagnosis of buffalo trypanosomiasis relies on the development of more affordable, rapid, and field-adapted methods, particularly in resource-limited endemic countries.

6.5. Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis is also essential, as

T. vivax infections share clinical similarities with other diseases. During acute febrile phases, trypanosomiasis should be distinguished from babesiosis and anaplasmosis, since

T. vivax infections rarely produce jaundice or hemoglobinuria, and parasitological examination allows differentiation [

13]. In chronic forms characterized by emaciation, lymphadenopathy, and absence of fever, the main differentials are helminthiases, which can be confirmed through parasitological testing. For neurological cases, rabies must be carefully excluded, given its public health importance. Unlike trypanosomiasis, rabies is not associated with anemia or weight loss, and its confirmation requires specific laboratory techniques such as direct immunofluorescence, PCR, mouse inoculation, or histopathology.

7. Control and Prophylaxis

7.1. Principles of Integrated Control in Buffalo Herds

Global control programs for trypanosomiasis generally integrate three main pillars: vector control, diagnosis, and treatment. In the context of

T. vivax, disease management in buffaloes requires restricting the movement of clinically affected animals, systematic herd monitoring, and timely therapeutic intervention. Supportive measures are also critical to improve the efficacy of trypanocidal drugs, such as avoiding animal transportation and pasture changes during the acute phase, while ensuring adequate nutrition and balanced supplementation [

5,

8,

13].

7.2. Chemotherapy, Treatment Failures, and Resistance

The principal trypanocidal drugs used in buffaloes, cattle, sheep, and goats are diminazene aceturate and isometamidium chloride [

8,

13,

60]. In Brazil, these two compounds are the only licensed trypanocides authorized by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA) [

60]. Nevertheless, intensive use has already led to reports of drug resistance [

17,

18]. Another option, although less frequently employed, is homidium bromide or chloride [

16]. In an outbreak of

T. vivax in Venezuela [

8], affected buffalo herds were successfully treated with isometamidium chloride (1.0 mg/kg body weight, intramuscularly), in combination with supportive therapy consisting of multivitamin supplementation and hematinic drugs. Treatment reduced mortality and prevented new symptomatic cases, confirming both the etiological role of

T. vivax and the effectiveness of the drug in that context. In addition, the latest trypanocide to be developed is melarsomine dihydrochloride. Nonetheless, this trypanocide causes nervous signs in buffaloes (0.75 mg/kg body weight, intramusculary), in a transient side effect [

63]. A synthesis of these treatments is described in the

Table 4.

7.3. Biosecurity and Iatrogenic Transmission Prevention

From a preventive perspective, quarantine of newly introduced animals, although not a widespread practice, is an essential biosecurity measure to avoid introduction of

T. vivax into non-endemic regions. Likewise, proper handling of needles and syringes during vaccination or drug administration is fundamental to prevent iatrogenic transmission [

3]. In West Africa, the presence of so-called trypanotolerant breeds of cattle, particularly the N’Dama, has been reported as an important strategy to reduce trypanocide usage [

16]. However, to date, no trypanotolerant breeds have been described among water buffaloes.

7.4. Vector Control in Floodplain and Tropical Systems

Vector control requires consideration of the target species, its ecological niche, climatic conditions, and agroecological context [

16]. Holmes [

16] describes several environmentally acceptable tactics for tsetse fly control and eradication, including: (I) the Sequential Aerosol Technique (SAT), involving four to five applications of ultra-low volume, non-persistent insecticides by GPS-guided aircraft, with excellent results in savanna ecosystems; (II) the live bait technique, consisting of insecticide application to livestock via spraying, which also protects against other ectoparasites; (III) the artificial bait system, involving insecticide-impregnated traps or target fabrics in blue and black, capable of suppressing up to 95% of fly populations; and (IV) the sterile insect technique, in which sterilized males are released to interrupt reproduction, used when other strategies fail to achieve sufficient suppression.

7.5. Vaccine Prospects and Translational Challenges

In parallel, research efforts have advanced toward the development of vaccines. A recent study reported a candidate vaccine targeting the invariant surface glycoprotein IFX of

T. vivax, which induced protective immunity in a murine model [

19]. Nonetheless, vaccine development against trypanosomes faces significant obstacles, including parasite antigenic variation, host immunosuppression, and the lack of robust experimental models. Even so, current research highlights promising avenues, such as the identification of invariant proteins and the use of innovative technologies including mRNA vaccines and gene editing platforms [

3].

8. Conclusions

This review represents the first comprehensive synthesis dedicated specifically to Trypanosoma vivax infection in water buffaloes, with a particular emphasis on the Amazon Biome where buffalo husbandry is of major economic and cultural importance. By collating data from Africa and Latin America, this work demonstrates that buffaloes are not merely incidental hosts but central actors in the epidemiology of T. vivax, capable of developing acute, subacute, and chronic infections while simultaneously serving as long-term reservoirs that perpetuate parasite transmission.

The novelty of this review lies in its integrated perspective: it bridges molecular pathogenesis, field epidemiology, diagnostic innovations, therapeutic challenges, and control strategies, while contextualizing these issues in Amazonian floodplain systems where vector dynamics and management practices create unique conditions for disease persistence. This synthesis therefore fills a critical gap in the literature, moving beyond the traditional cattle-centered paradigm and establishing buffaloes as an important species in the study of trypanosomiasis.

Nevertheless, substantial gaps remain. The immunological mechanisms of chronic carriage in buffaloes are poorly understood; the molecular basis of emerging trypanocide resistance requires urgent investigation; field-adapted diagnostic tools remain limited; and the true economic impact of buffalo trypanosomiasis is largely undocumented. Addressing these gaps will demand multidisciplinary research that integrates parasitology, molecular biology, immunology, epidemiology, and socio-economics, framed within a One Health approach.

By consolidating fragmented evidence and highlighting future research priorities, this review provides veterinarians, researchers, and policymakers with a robust reference point to inform surveillance and sustainable disease management strategies. More broadly, it underscores that controlling T. vivax in buffaloes is not only essential for animal health and productivity, but also for safeguarding food security, rural livelihoods, and the ecological sustainability of livestock systems in tropical environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: Schematic diagram illustrating the methodology of the investigation of

Trypanosoma vivax infection on Marajó Island; Figure S2: A 1.5% agarose gel demonstrating the presence of

T. vivax. Lane L corresponds to the 100 base pair molecular weight marker (100 bp DNA Ladder). Lanes 1 to 72 are PCR products (amplicons) derived by DNA from blood samples corresponding to 72 different buffaloes. Lane C+ corresponds to the positive control, which represents the amplicon formed by DNA from a buffalo blood sample known to be positive for

T. vivax. Lane C- corresponds to the negative control, which represents the amplicon formed by ultrapure sterilized water instead of a sample DNA. Lane 46 represents the buffalo sample positive for

T. vivax, amplifying at the 177 bp position on the agarose gel, similar to C+.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.d.M.C.L., D.V.d.O.B. and F.M.S.; methodology, A.d.M.C.L., D.V.d.O.B. and F.M.S.; validation, F.M.S., A.M.S. and H.d.A.B.; formal analysis, A.d.M.C.L., D.V.d.O.B. and F.M.S.; investigation, A.d.M.C.L., D.V.d.O.B. and F.M.S.M.; data curation, A.d.M.C.L., D.V.d.O.B., F.M.S.M., A.M.S., H.d.A.B. and F.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.d.M.C.L., D.V.d.O.B. and F.M.S.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M.S., H.d.A.B. and F.M.S.; supervision, F.M.S.; project administration, F.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol number Nº 6261300323 (ID 002208), approval date: 27 April 2023, was approved by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Para (CEUA/UFPA).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPESPA (Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas do Estado do Pará), and CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Desquesnes, M.; Sazmand, A.; Gonzatti, M.; Boulangé, A.; Bossard, G.; Thévenon, S.; Gimonneau, G.; Truc, P.; Herder, S.; Ravel, S.; et al. Diagnosis of Animal Trypanosomoses: Proper Use of Current Tools and Future Prospects. Parasit Vectors 2022, 15, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Gonzatti, M.; Sazmand, A.; Thévenon, S.; Bossard, G.; Boulangé, A.; Gimonneau, G.; Truc, P.; Herder, S.; Ravel, S.; et al. A Review on the Diagnosis of Animal Trypanosomoses. Parasit Vectors 2022, 15, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Serra, T.B.R.; Dos Reis, A.T.; Silva, C.F.D.C.; Soares, R.F.S.; Fernandes, S. de J.; Gonçalves, L.R.; da Costa, A.P.; Machado, R.Z.; Nogueira, R. de M.S. Serological and Molecular Diagnosis of Trypanosoma vivax on Buffalos (Bubalus Bubalis) and Their Ectoparasites in the Lowlands of Maranhão, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria 2024, 33, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Dyonisio, G.H.S.; Batista, H.R.; Da Silva, R.E.; De Freitas E Azevedo, R.C.; De Oliveira Jorge Costa, J.; De Oliveira Manhães, I.B.; Tonhosolo, R.; Gennari, S.M.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Marcili, A. Molecular Diagnosis and Prevalence of Trypanosoma vivax (Trypanosomatida: Trypanosomatidae) in Buffaloes and Ectoparasites in the Brazilian Amazon Region. J Med Entomol 2021, 58, 403–407. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, H.A.G.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Pivat, I.H.V.; Fuzato, A.C.R.; Camargo, E.P.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Teixeira, M.M.G. High Trypanosoma vivax Infection Rates in Water Buffalo and Cattle in the Brazilian Lower Amazon. Parasitol Int 2020, 79, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L.J.; Vezza, L.; Rowan, T.; Hope, J.C. Animal African Trypanosomiasis: Time to Increase Focus on Clinically Relevant Parasite and Host Species. Trends Parasitol 2016, 32, 599–607. [CrossRef]

- Fetene, E.; Leta, S.; Regassa, F.; Büscher, P. Global Distribution, Host Range and Prevalence of Trypanosoma vivax: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasit Vectors 2021, 14, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.A.; Ramírez, O.J.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Sánchez, R.G.; Bethencourt, A.M.; Del M. Pérez, G.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Teixeira, M.M.G. Trypanosoma vivax in Water Buffalo of the Venezuelan Llanos: An Unusual Outbreak of Wasting Disease in an Endemic Area of Typically Asymptomatic Infections. Vet Parasitol 2016, 230, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.D.; Possidonio, B.I. de O.; dos Santos, J.B.; Oliveira, H.G. da S.; Sousa, A.I. de J.; Barbosa, C.C.; Beuttemmuller, E.A.; Silveira, N. da S. e. S.; Brito, M.F.; Salvarani, F.M. Leucoderma in Buffaloes (Bubalus Bubalis) in the Amazon Biome. Animals 2023, 13, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.S.; Silva, J.A.R. da; Silva, W.C. da; Silva, É.B.R. da; Belo, T.S.; Sousa, C.E.L.; Rodrigues, T.C.G. de C.; Silva, A.G.M. e.; Prates, J.A.M.; Lourenço-Júnior, J. de B. A Review of the Nutritional Aspects and Composition of the Meat, Liver and Fat of Buffaloes in the Amazon. Animals 2024, 14, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.R. da; Garcia, A.R.; Almeida, A.M. de; Bezerra, A.S.; Lourenço Junior, J. de B. Water Buffalo Production in the Brazilian Amazon Basin: A Review. Trop Anim Health Prod 2021, 53, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.J.; Lainson, R. Trypanosoma vivax in Brazil. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1972, 66, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Osório, A.L.A.R.; Madruga, C.R.; Desquesnes, M.; Soares, C.O.; Ribeiro, L.R.R.; Costa, S.C.G. Trypanosoma (Duttonella) Vivax: Its Biology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Introduction in the New World-A Review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008, 103, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kolev, N.G.; Ramsdell, T.K.; Tschudi, C. Temperature Shift Activates Bloodstream VSG Expression Site Promoters in Trypanosoma Brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2018, 226, 20–23. [CrossRef]

- Magez, S.; Esteban, J.; Torres, P.; Oh, S.; Radwanska, M.; Bruschi, F. Salivarian Trypanosomes Have Adopted Intricate Host-Pathogen Interaction Mechanisms That Ensure Survival in Plain Sight of the Adaptive Immune System. pathogens 2021, 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, P. Tsetse-Transmitted Trypanosomes – Their Biology, Disease Impact and Control. J Invertebr Pathol 2013, 112, S11–S14. [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.; de Koning, H.P.; Mäser, P.; Horn, D. Drug Resistance in African Trypanosomiasis: The Melarsoprol and Pentamidine Story. Trends Parasitol 2013, 29, 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Nuryady, M.M.; Widayanti, R.; Nurcahyo, R.W.; Fadjrinatha, B.; Ahmad Fahrurrozi, Z.S. Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Multidrug-Resistant Protein-Encoding Genes in Trypanosoma Evansi Isolated from Buffaloes in Ngawi District, Indonesia. Vet World 2019, 12, 1573–1577. [CrossRef]

- Autheman, D.; Crosnier, C.; Clare, S.; Goulding, D.A.; Brandt, C.; Harcourt, K.; Tolley, C.; Galaway, F.; Khushu, M.; Ong, H.; et al. An Invariant Trypanosoma vivax Vaccine Antigen Induces Protective Immunity. Nature 2021, 595, 96–100. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.H.; Alves, F.P.; Teixeira, S.M.R. Animal Trypanosomiasis: Challenges and Prospects for New Vaccination Strategies. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—a Scale for the Quality Assessment of Narrative Review Articles. Res Integr Peer Rev 2019, 4, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health Diseases, Infections and Infestations Listed by WOAH Available online: https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-diseases/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Bastos, T.S.A.; Faria, A.M.; Madrid, D.M. de C.; De Bessa, L.C.; Linhares, G.F.C.; Fidelis Junior, O.L.; Sampaio, P.H.; Cruz, B.C.; Cruvinel, L.B.; Nicaretta, J.E.; et al. First Outbreak and Subsequent Cases of Trypanosoma vivax in the State of Goiás, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria 2017, 26, 366–371. [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.P.; Schuster, S.; Cren-Travaillé, C.; Bertiaux, E.; Cosson, A.; Goyard, S.; Perrot, S.; Rotureau, B. The Cyclical Development of Trypanosoma vivax in the Tsetse Fly Involves an Asymmetric Division. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2016, 6, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.P.; Goyard, S.; Xia, D.; Foth, B.J.; Sanders, M.; Wastling, J.M.; Minoprio, P.; Berriman, M. Global Gene Expression Profiling through the Complete Life Cycle of Trypanosoma vivax. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Dia, M.L. Mechanical Transmission of Trypanosoma vivax in Cattle by the African Tabanid Atylotus Fuscipes. Vet Parasitol 2004, 119, 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Silvester, E.; McWilliam, K.; Matthews, K. The Cytological Events and Molecular Control of Life Cycle Development of Trypanosoma brucei in the Mammalian Bloodstream. Pathogens 2017, 6, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Biteau-Coroller, F.; Bouyer, J.; Dia, M.L.; Foil, L. Development of a Mathematical Model for Mechanical Transmission of Trypanosomes and Other Pathogens of Cattle Transmitted by Tabanids. Int J Parasitol 2009, 39, 333–346. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Florentin, A.S.; Bethencourt, A.M.; Reyna-Bello, A.; Chávez-Larrea, M.A.; Pereira, C.L.; Bengaly, Z.; Sheferaw, D.; et al. From Intact to Highly Degraded Mitochondrial Genes in Trypanosoma vivax: New Insights into Introduction from Africa and Adaptation to Exclusive Mechanical Transmission in South America. Parasitologia 2024, 4, 390–404. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.M.; Batista, J.S.; Lima, J.M.; Freitas, F.J.; Barros, I.O.; Garcia, H.A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Camargo, E.P.; Teixeira, M.M. Field and Experimental Symptomless Infections Support Wandering Donkeys as Healthy Carriers of Trypanosoma vivax in the Brazilian Semiarid, a Region of Outbreaks of High Mortality in Cattle and Sheep. Parasit Vectors 2015, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Dávila, A.M.R.; Herrera, H.M.; Schlebinger, T.; Souza, S.S.; Traub-Cseko, Y.M. Using PCR for Unraveling the Cryptic Epizootiology of Livestock Trypanosomosis in the Pantanal, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2003, 117, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Berthier, D.; Brenière, S.F.; Bras-Gonçalves, R.; Lemesre, J.-L.; Jamonneau, V.; Solano, P.; Lejon, V.; Thévenon, S.; Bucheton, B. Tolerance to Trypanosomatids: A Threat, or a Key for Disease Elimination? Trends Parasitol 2016, 32, 157–168. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.S.; Castilho Neto, K.J.G. de A.; Duffy, C.W.; Richards, P.; Noyes, H.; Ogugo, M.; Rogério André, M.; Bengaly, Z.; Kemp, S.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; et al. Variant Antigen Diversity in Trypanosoma vivax Is Not Driven by Recombination. Nat Commun 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Jaimes-Dueñez, J.; Triana-Chávez, O.; Mejía-Jaramillo, A.M. Spatial-Temporal and Phylogeographic Characterization of Trypanosoma Spp. in Cattle (Bos Taurus) and Buffaloes (Bubalus Bubalis) Reveals Transmission Dynamics of These Parasites in Colombia. Vet Parasitol 2018, 249, 30–42. [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.L.M.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Coatnoan, N.; Cosson, A.; Cadioli, F.A.; Garcia, H.A.; Gerber, A.L.; Machado, R.Z.; Minoprio, P.M.C.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; et al. A Comparative in Silico Linear B-Cell Epitope Prediction and Characterization for South American and African Trypanosoma vivax Strains. Genomics 2019, 111, 407–417. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.; Garcia, M.E.; Pérez, G.; Bethencourt, A.; Zerpa, E.; Pérez, H.; Mendoza-León, A. Trypanosomiasis in Venezuelan Water Buffaloes: Association of Packed-Cell Volumes with Seroprevalence and Current Trypanosome Infection. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2006, 100, 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Bengaly, Z.; Minervino, A.H.; Riet-Correa, F.; Machado, R.Z.; Paiva, F.; Batista, J.S.; Neves, L.; et al. Microsatellite Analysis Supports Clonal Propagation and Reduced Divergence of Trypanosoma vivax from Asymptomatic to Fatally Infected Livestock in South America Compared to West Africa. Parasit Vectors 2014, 7, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Barros Moura, A.C.; Silva Filho, E.; Machado Barbosa, E.; Assunção Pereira, W.L. Comparative Analysis of PCR, Real-Time PCR and LAMP Techniques in the Diagnosis of Trypanosoma vivax Infection in Naturally Infected Buffaloes and Cattle in the Brazilian Amazon. Pak Vet J 2024, 44, 123–128. [CrossRef]

- Takeet, M.I.; Fagbemi, B.O.; Donato, M. De; Yakubu, A.; Rodulfo, H.E.; Peters, S.O.; Wheto, M.; Imumorin, I.G. Molecular Survey of Pathogenic Trypanosomes in Naturally Infected Nigerian Cattle. Res Vet Sci 2013, 94, 555–561. [CrossRef]

- Dayo, G.K.; Bengaly, Z.; Messad, S.; Bucheton, B.; Sidibe, I.; Cene, B.; Cuny, G.; Thevenon, S. Prevalence and Incidence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in an Agro-Pastoral Area of Southwestern Burkina Faso. Res Vet Sci 2010, 88, 470–477. [CrossRef]

- Adam, Y.; Marcotty, T.; Cecchi, G.; Mahama, C.I.; Solano, P.; Bengaly, Z.; Van den Bossche, P. Bovine Trypanosomosis in the Upper West Region of Ghana: Entomological, Parasitological and Serological Cross-Sectional Surveys. Res Vet Sci 2012, 92, 462–468. [CrossRef]

- Tamasaukas, R.; Roa, N.; Cobo, M. Trypanosomosis Due to Trypanosoma vvax in Two Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis) Farms of Guárico State, Venezuela. Revista Científica 2006, XVI, 575–578.

- Zapata, R.; Mesa, J.; Mejía, J.; Reyes, J.; Ríos, L.A. Frecuencia de Infección Por Trypanosoma Sp. En Búfalos de Agua (Bubalus Bubalis) En Cuatro Hatos Bufaleros de Barrancabermeja, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias 2009, 22, 25–32.

- Fikru, R.; Goddeeris, B.M.; Delespaux, V.; Moti, Y.; Tadesse, A.; Bekana, M.; Claes, F.; De Deken, R.; Büscher, P. Widespread Occurrence of Trypanosoma vivax in Bovines of Tsetse- as Well as Non-Tsetse-Infested Regions of Ethiopia: A Reason for Concern? Vet Parasitol 2012, 190, 355–361. [CrossRef]

- Biryomumaisho, S.; Rwakishaya, E.K.; Melville, S.E.; Cailleau, A.; Lubega, G.W. Livestock Trypanosomosis in Uganda: Parasite Heterogeneity and Anaemia Status of Naturally Infected Cattle, Goats and Pigs. Parasitol Res 2013, 112, 1443–1450. [CrossRef]

- Black, S.J.; Seed, J.R.; Murphy, N.B. Innate and Acquired Resistance to African Trypanosomiasis. J Parasitol 2001, 87, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.L.; Barra, E.C.; Paredes, L.J.; Barbosa, E.M.; Casseb, A.R.; Silva, C.S.; Filho, S.T.; Filho, E.S. Hemoparasites Effect on Interferon-Gamma and MiRNA 125b Expression in Bubalus Bubalis. Iraqi Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2024, 38, 71–76. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Verma, M.K.; Rahman, J.U.; Singh, A.K.; Patidar, S.; Jakhar, J. An Overview of the Various Methods for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Controlling of Trypanosomiasis in Domestic, Pet, and Wild Animals. Biological Forum-An International Journal 2021, 13, 389.

- Vieira, O.L.E.; Macedo, L.O. de; Santos, M.A.B.; Silva, J.A.B.A.; Mendonça, C.L. de; Faustino, M.A. da G.; Ramos, C.A. do N.; Alves, L.C.; Ramos, R.A.N.; Carvalho, G.A. de Detection and Molecular Characterization of Trypanosoma (Duttonella) Vivax in Dairy Cattle in the State of Sergipe, Northeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2017, 26, 516–520. [CrossRef]

- Angara T-E.E, A.T.-E.E.; Ismail A. A, I.A.A.; Ibrahim A.M, I.A.M. An Overview on the Economic Impacts of Animal Trypanosomiasis. Glob J Res Anal 2012, 3, 275–276. [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.W.; Dávila, A.M.R. Trypanosoma vivax – out of Africa. Trends Parasitol 2001, 17, 99–101. [CrossRef]

- Guegan, F.; Plazolles, N.; Baltz, T.; Coustou, V. Erythrophagocytosis of Desialylated Red Blood Cells Is Responsible for Anaemia during Trypanosoma vivax Infection. Cell Microbiol 2013, 15, 1285–1303. [CrossRef]

- Galiza, G.J.N.; Garcia, H.A.; Assis, A.C.O.; Oliveira, D.M.; Pimentel, L.A.; Dantas, A.F.M.; Simões, S. V.D.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Riet-Correa, F. High Mortality and Lesions of the Central Nervous System in Trypanosomosis by Trypanosoma vivax in Brazilian Hair Sheep. Vet Parasitol 2011, 182, 359–363. [CrossRef]

- Cadioli, F.A.; Barnabé, P. de A.; Machado, R.Z.; Teixeira, M.C.A.; André, M.R.; Sampaio, P.H.; Fidélis Junior, O.L.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Marques, L.C. First Report of Trypanosoma vivax Outbreak in Dairy Cattle in São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet 2012, 21, 118–124.

- Monzón, C.M.; Mancebo, O.A.; Jiménez, J.N. Trypanosoma vivax En Búfalos (Bubalus Bubalis) En Formosa, Argentina. Revista Veterinaria Argentina 2010, XXVII, 1–8.

- Woo, P.T.K.; Rogers, D.J. A Statistical Study of the Sensitivity of the Haematocrit Centrifuge Technique in the Detection of Trypanosomes in Blood. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1974, 68, 319–326. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, T.R.; Bomfim, S.R.M.; Cavalcanti, F.B.P.; Lopes, W.D.Z.; Utsonomiya, Y.T.; Cadioli, F.A. “Lysis and Concentration Technique” Improves the Parasitological Diagnosis of Trypanosoma vivax. Vet Parasitol 2023, 323, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Soroka, M.; Wasowicz, B.; Rymaszewska, A. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): The Better Sibling of PCR? Cells 2021, 10, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Castilho Neto, K.J.G.D.A.; Garcia, A.B. da C.F.; Junior, O.L.F.; Nagata, W.B.; André, M.R.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Machado, R.Z.; Cadioli, F.A. Follow-up of Dairy Cattle Naturally Infected by Trypanosoma vivax after Treatment with Isometamidium Chloride. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria 2021, 30, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.; Garcia, M.-E.; Perez, H.; Mendoza-Leon, A. The Detection and PCR-Based Characterization of the Parasites Causing Trypanosomiasis in Water-Buffalo Herds in Venezuela. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2005, 99, 359–370. [CrossRef]

- Cortez, A.P.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Garcia, H.A.; Neves, L.; Batista, J.S.; Bengaly, Z.; Paiva, F.; Teixeira, M.M.G. Cathepsin L-like Genes of Trypanosoma vivax from Africa and South America – Characterization, Relationships and Diagnostic Implications. Mol Cell Probes 2009, 23, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Dargantes, A.; Lai, D.-H.; Lun, Z.-R.; Holzmuller, P.; Jittapalapong, S. Trypanosoma Evansi and Surra: A Review and Perspectives on Transmission, Epidemiology and Control, Impact, and Zoonotic Aspects. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Hilali, M.; Abdel-Gawad, A.; Nassar, A.; Abdel-Wahab, A. Hematological and Biochemical Changes in Water Buffalo Calves (Bubalus Bubalis) Infected with Trypanosoma Evansi. Vet Parasitol 2006, 139, 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, M.A.; Mingala, C.N.; Tubalinal, G.A.S.; Gaban, P.B. V.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y. Emerging Infectious Diseases in Water Buffalo: An Economic and Public Health Concern. In Emerging Infectious Diseases in Water Buffalo - An Economic and Public Health Concern; InTechOpen: London, 2018.

- García, H.A.; García, M.E.; Zerpa, H.A.; Pérez, G.; Contreras, C.E.; Pivat, I. V.; Mendoza-León, A. Detección Parasitológica y Molecular de Infecciones Naturales Por Trypanosoma Evansi y Trypanosoma vivax En Búfalos de Agua (Bubalus Bubalis) y Chiguires (Hydrochoerus Hydrochaeris) En Los Estados Apure, Cojedes y Guárico, Venezuela. Rev. Fac. Cs. Vets 2003, 44, 131–144.

- Jaramillo, I.-L.; Tobon, J.C.; Agudelo, P.M.; Ruiz, J.D. Biochemical Blood Profile in Water Buffalo: Alterations Related to Natural Infection by Trypanosoma Spp. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y de Zootecnia 2023, 70, 30–44. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).