Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

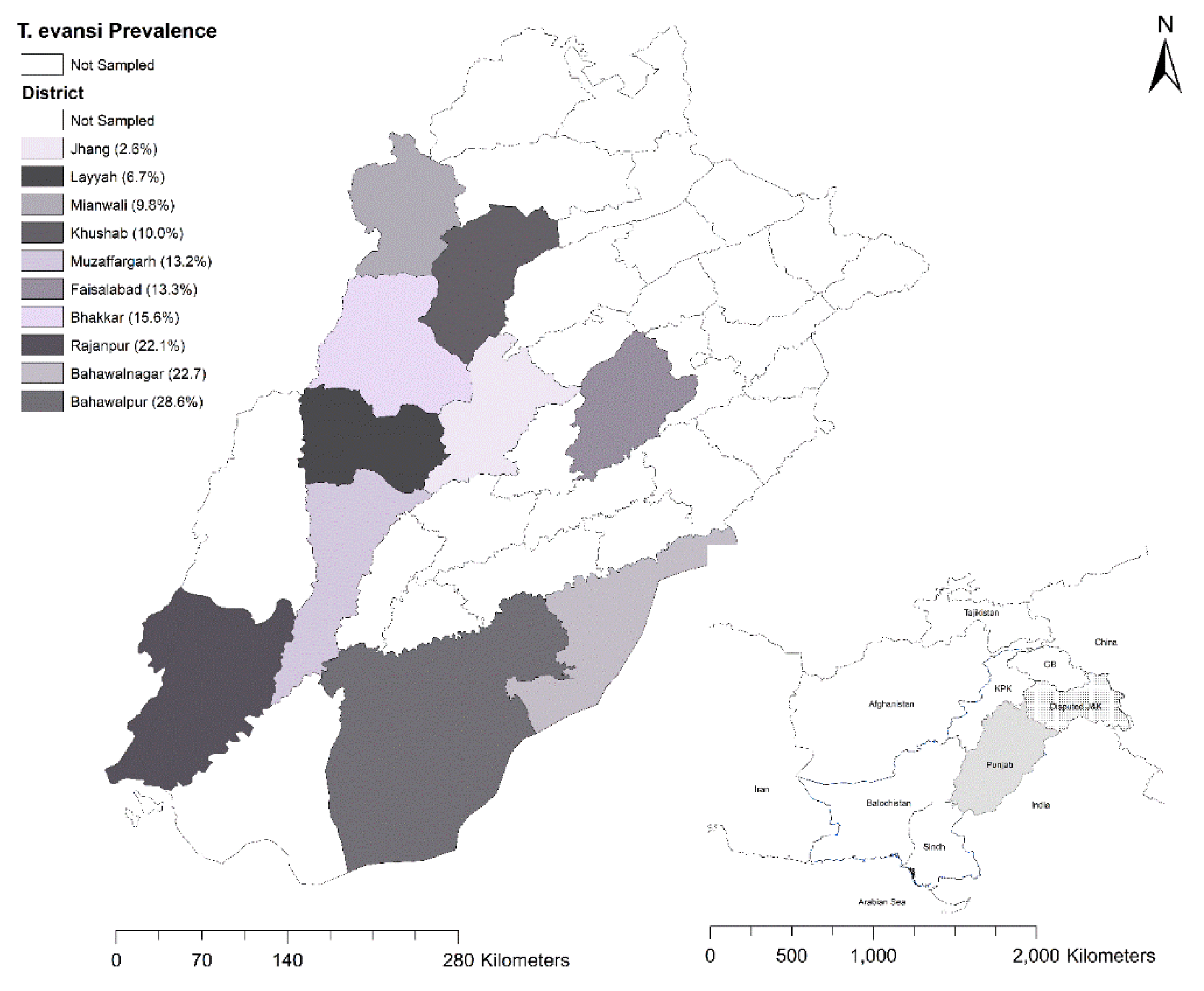

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

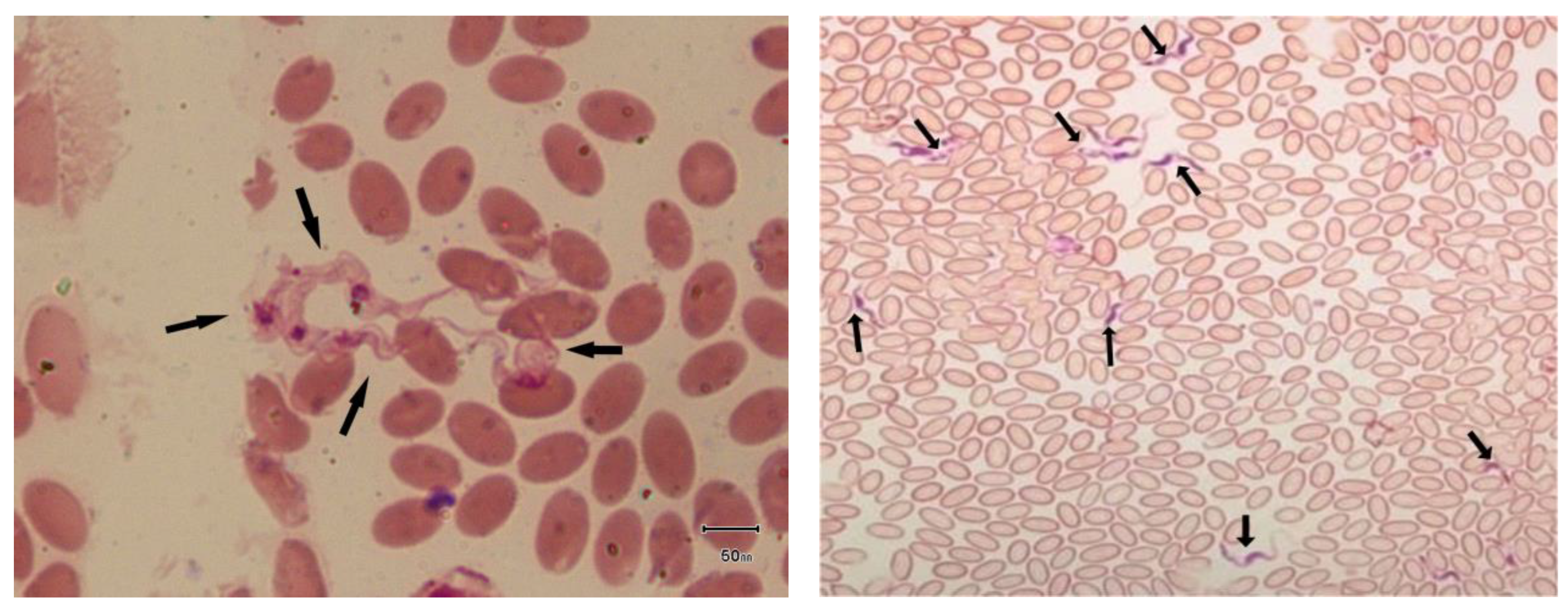

2.2. Microscopic Examination

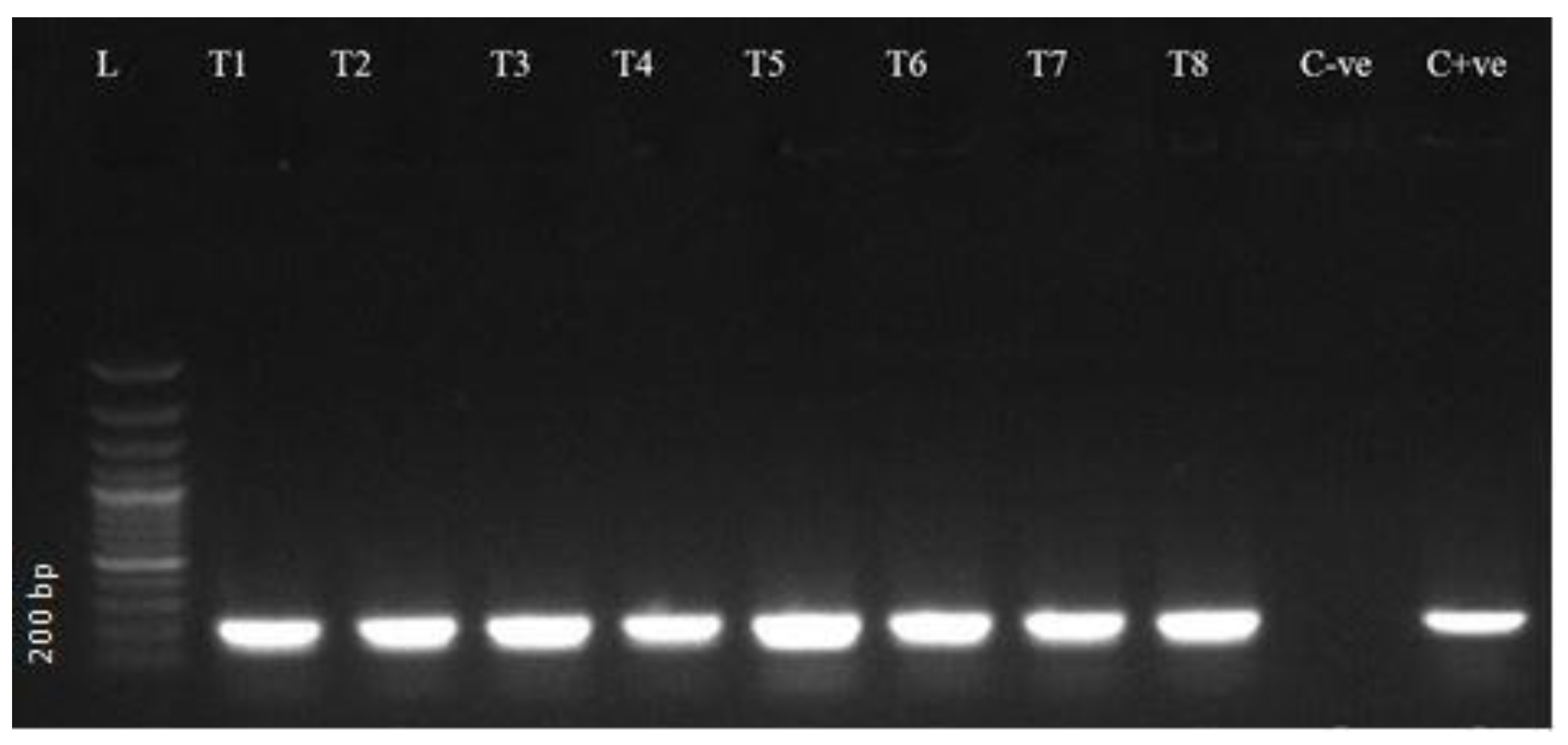

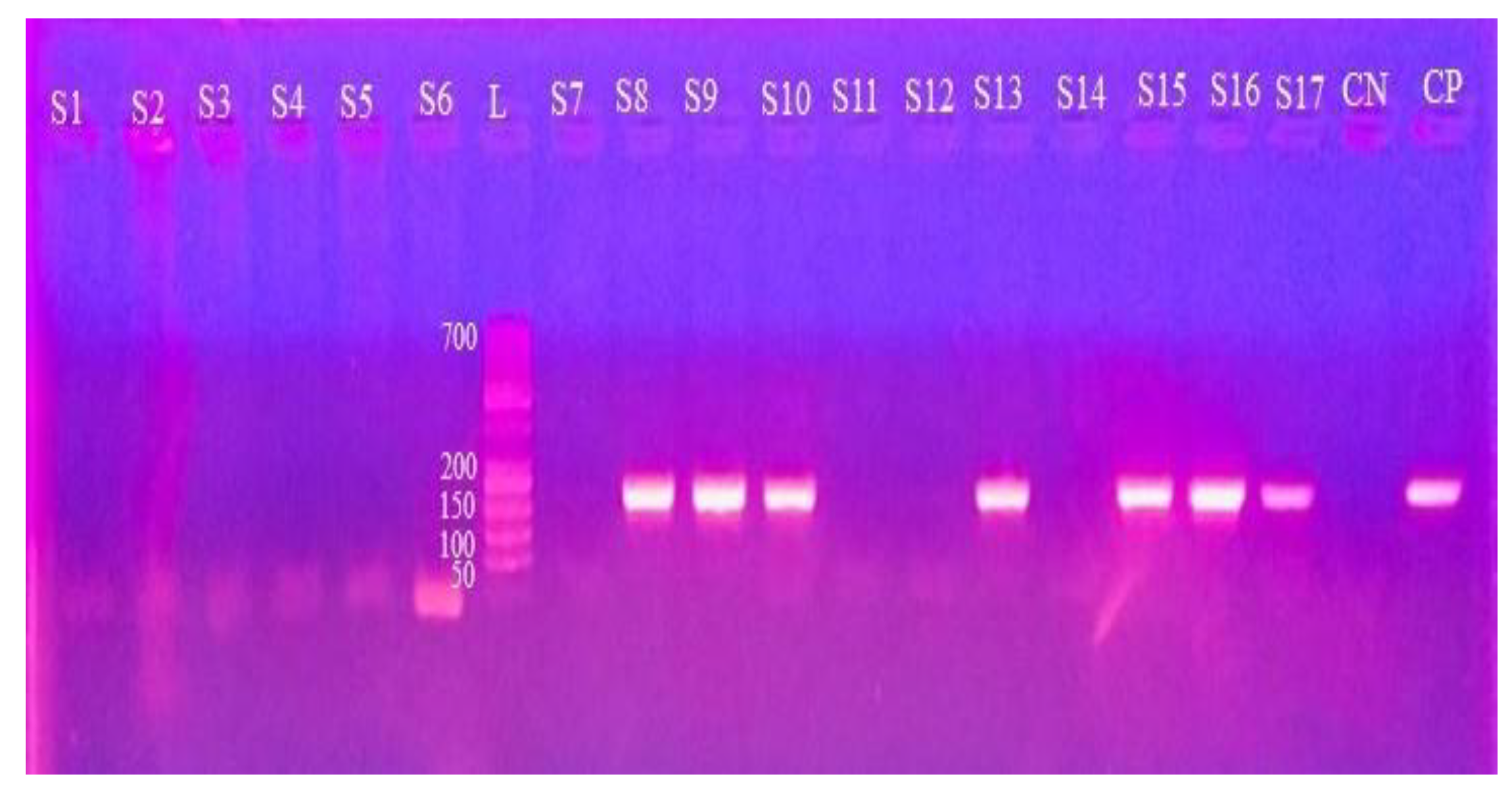

2.3. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

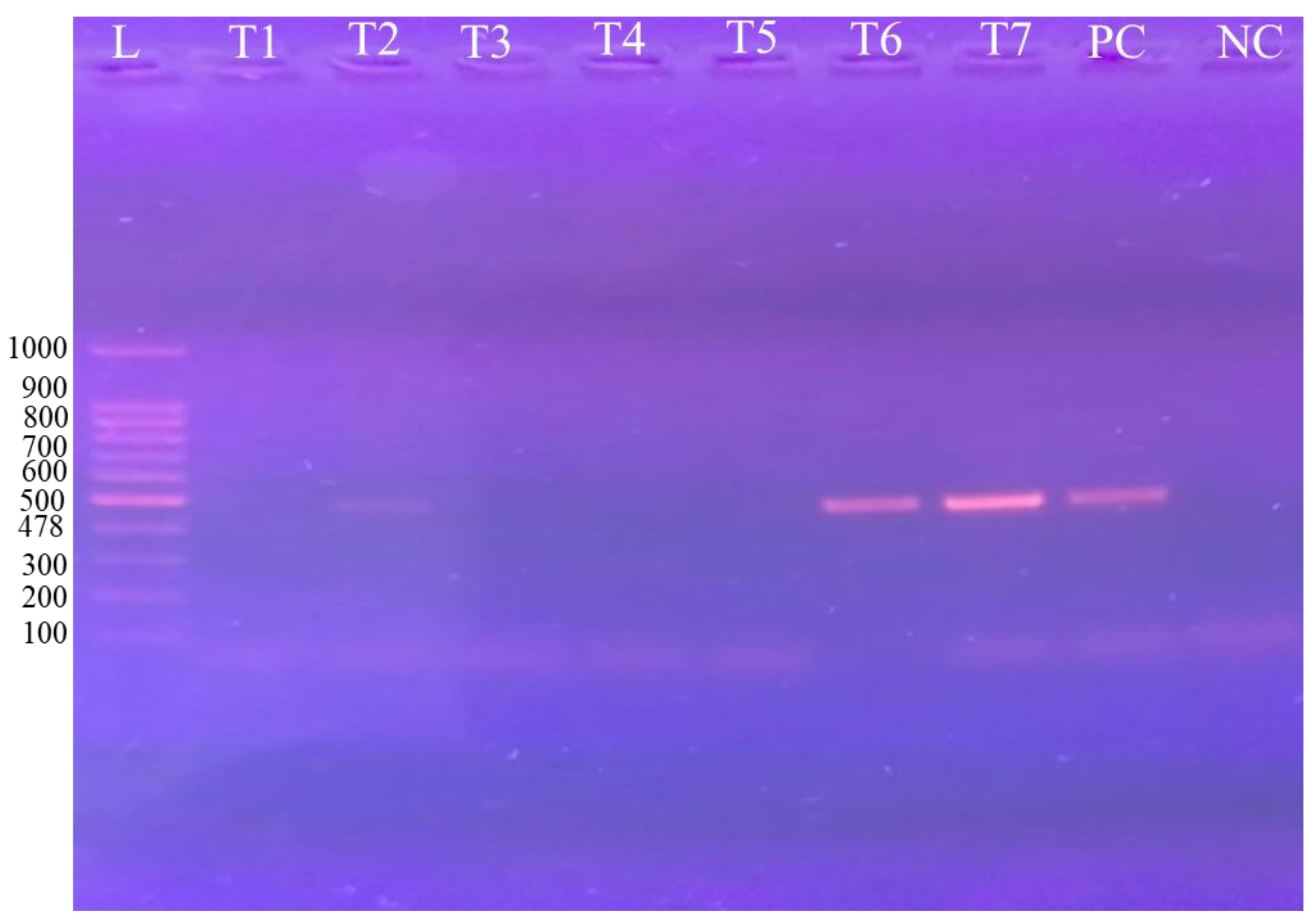

2.4. Gel Electrophoresis

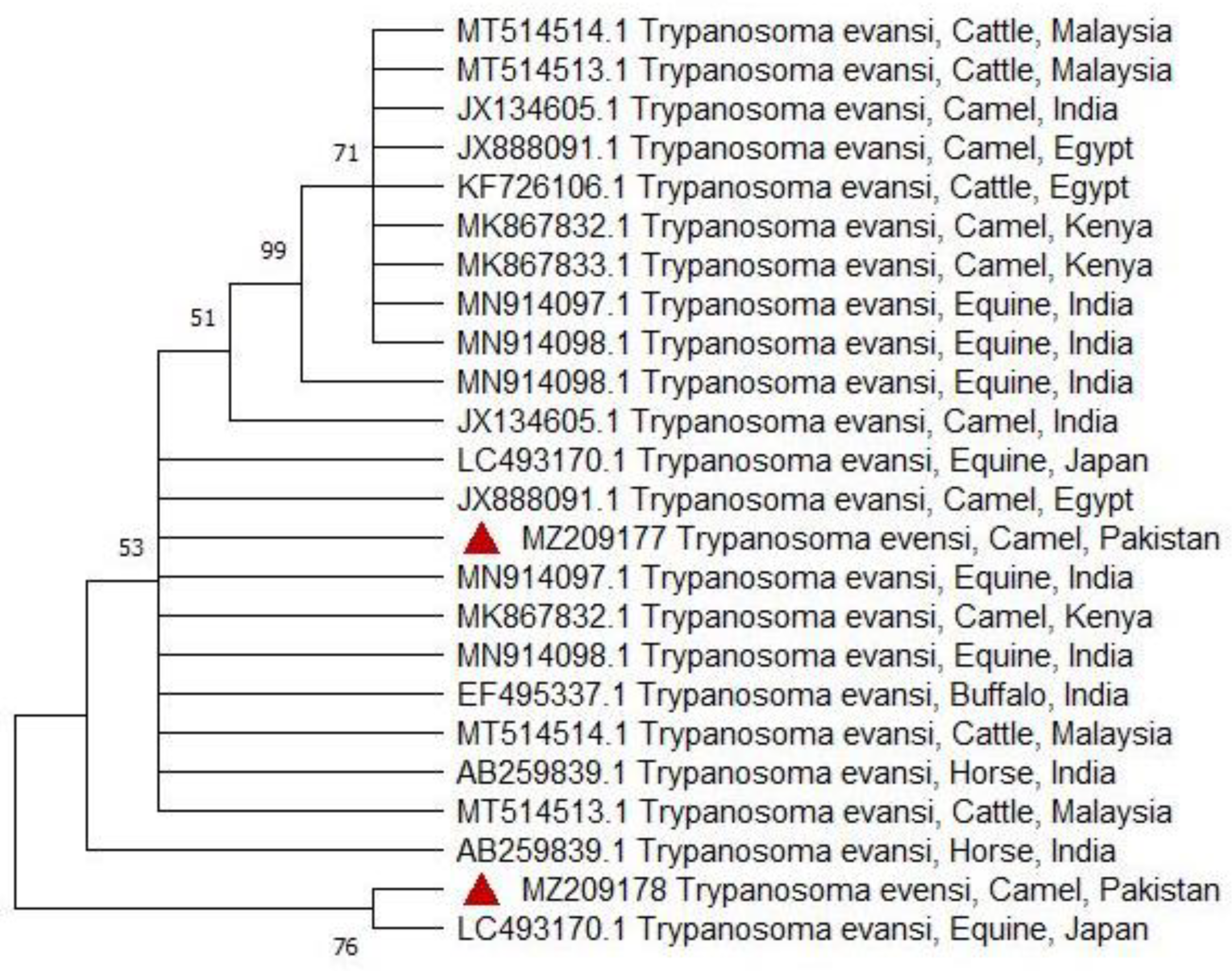

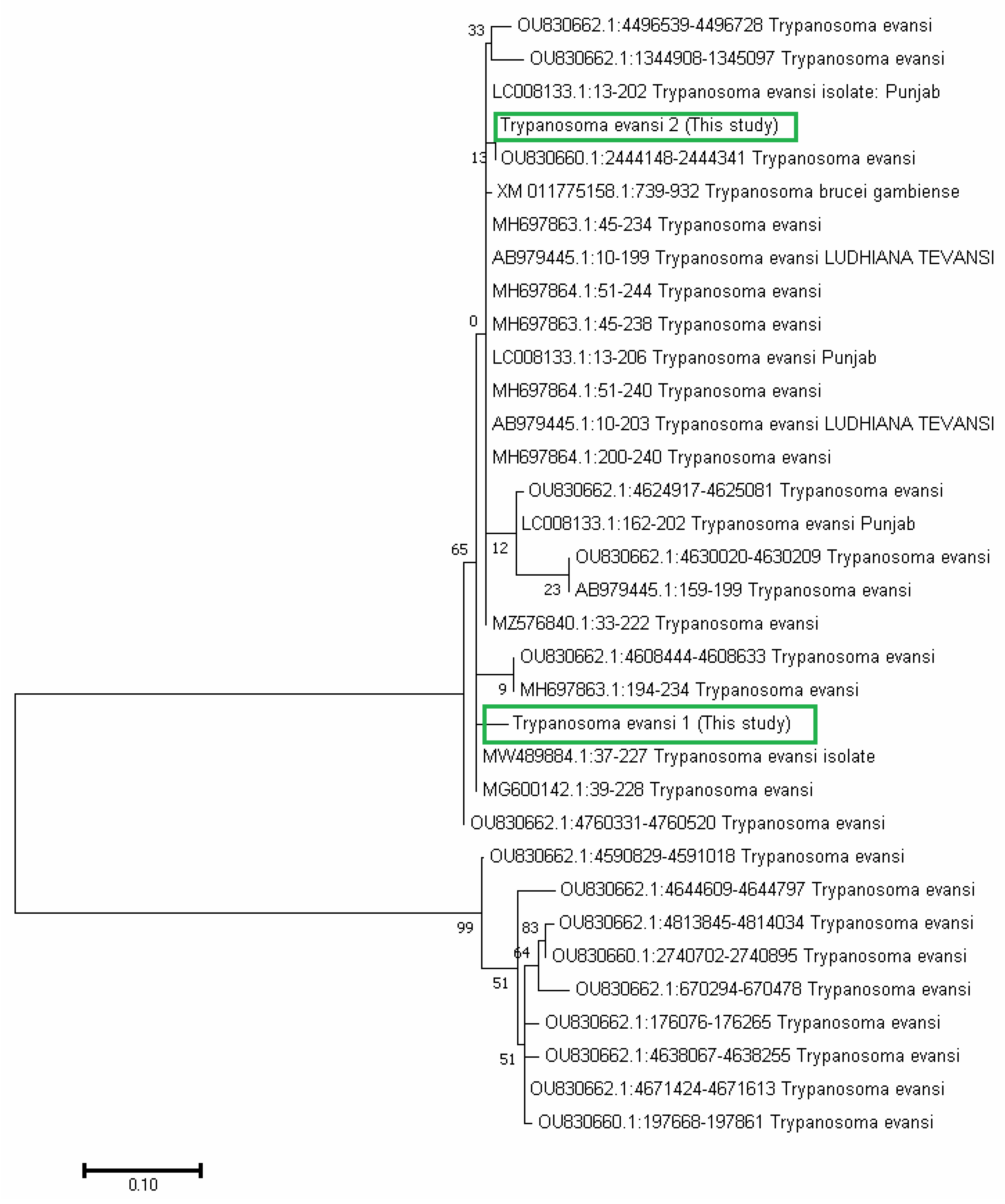

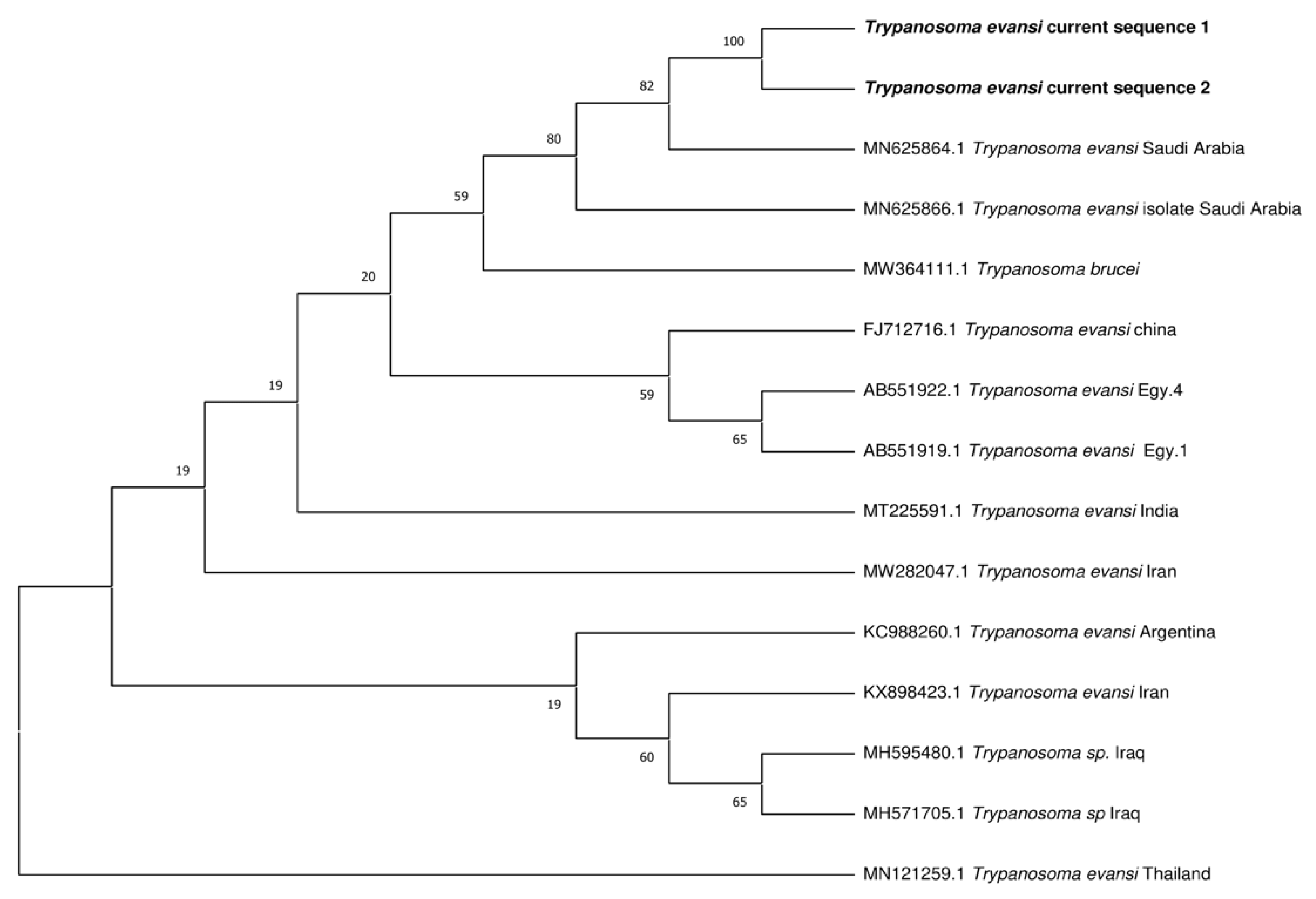

2.5. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

| Accession No/ ID | Parasite spp. |

|---|---|

| ON868415 | Trypanosoma evansi |

| ON868416 | Trypanosoma evansi |

| ON868417 | Trypanosoma evansi |

| ON868418 | Trypanosoma evansi |

| MZ209177 | Trypanosoma evansi |

| MZ209178 | Trypanosoma evansi |

2.6. Serum Biochemistry

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microscopic Findings

| District | Camel Population (LSC 2018) |

Tested | Microscopy | PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Prev. % (95% CI) |

Positive | Prev. % (95% CI) |

|||

| Jhang | 1265 | 39 | 0 | 0 (0-9) | 1 | 2.6 (0.1-13.5) |

| Faisalabad | 687 | 15 | 1 | 6.7 (0.2-31.9) | 2 | 13.3 (1.7-40.5) |

| Bhakkar | 5310 | 90 | 7 | 7.8 (3.2-15.4) | 14 | 15.6 (8.8-24.7) |

| Mianwali | 1886 | 41 | 2 | 4.9 (0.6-16.5) | 4 | 9.8 (2.7-23.1) |

| Khushab | 3712 | 40 | 2 | 5 (0.6-16.9) | 4 | 10 (2.8-23.7) |

| Rajanpur | 7594 | 86 | 12 | 13.9 (7.4-23.1) | 19 | 22.1 (13.9-32.3) |

| Muzaffargarh | 1687 | 38 | 4 | 10.5 (2.9-24.8) | 5 | 13.2 (4.4-28.1) |

| Bahawalpur | 1078 | 14 | 2 | 14.3 (1.8-42.8) | 4 | 28.6 (8.4-58.1) |

| Bahawalnagar | 681 | 22 | 2 | 9.1 (1.1-29.2) | 5 | 22.7 (7.8-45.4) |

| Layyah | 3155 | 15 | 1 | 6.7 (0.2-31.9) | 1 | 6.7 (0.2-31.9) |

| Total | 27055 | 400 | 33 | 8.3 (5.7-11.4) | 59 | 14.8 (11.4-18.6) |

3.2. Molecular Detection Through PCR

3.3. Comparison of the Diagnostic Performance

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.5. Risk Factors Associated with T. evansi Prevalence

3.6. Serum Biochemical Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T. evansi | Trypanosoma evansi |

| FAT | Fisher’s Exact Test |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| CI | 95% binomial exact confidence interval |

| PC | Positive control |

| NC | Negative control |

| CP | Control positive |

| CN | Control negative |

| MS | Microscopy |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| GSBS | Giemsa-stained blood smears |

References

- Ahmad, S.; Kour, G.; Singh, A.; Gulzar, M. Animal Genetic Resources of India - An Overview. International Journal of Livestock Research 2019, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, A.; Mustafa, M.I.; Lateef, M.; Yaqoob, M.; Younas, M. Production Potential of Camel and Its Prospects in Pakistan. Punjab Univ. J. Zool 2013, 28, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassani, W.E. Camel Milk: Nutritional Composition, Therapeutic Properties, and Benefits for Human Health. Open Vet J 2024, 14, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kula, J.; Nejash, A.; Golo, D.; Makida, E. Camel Trypanosomiasis: A Review on Past and Recent Research in Africa and Middle East. Am. J. Sci. Res 2017, 12, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Djetchi, M.K.; Ilboudo, H.; Koffi, M.; Kaboré, J.; Kaboré, J.W.; Kaba, D.; Courtin, F.; Coulibaly, B.; Fauret, P.; Kouakou, L.; et al. The Study of Trypanosome Species Circulating in Domestic Animals in Two Human African Trypanosomiasis Foci of Côte d’Ivoire Identifies Pigs and Cattle as Potential Reservoirs of Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olani, A.; Habtamu, Y.; Wegayehu, T.; Anberber, M. Prevalence of Camel Trypanosomosis (Surra) and Associated Risk Factors in Borena Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Parasitol Res 2016, 115, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Khan, A.; Abbas, R.Z.; Ghaffar, A.; Abbas, G.; Rahman, T.; Ali, F. Clinico-Hematological and Biochemical Studies on Naturally Infected Camels with Trypanosomiasis. Pak. J. Zool 2016, 48, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Abera, Z.; Box, P.O.; Usmane, A.; Ayana, Z. Review on Camel Trypanosomosis: Its Epidemiology and Economic Importance. Acta Parasitol. Glob 2015, 6, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Aregawi, W.G.; Agga, G.E.; Abdi, R.D.; Büscher, P. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Global Distribution, Host Range, and Prevalence of Trypanosoma Evansi. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.D.; Herrera, G.; Hernández, C.; Cruz-Saavedra, L.; Muñoz, M.; Flórez, C.; Butcher, R. Evaluation of the Analytical and Diagnostic Performance of a Digital Droplet Polymerase Chain Reaction (DdPCR) Assay to Detect Trypanosoma Cruzi DNA in Blood Samples. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0007063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidambasi, K.O.; Masiga, D.K.; Villinger, J.; Carrington, M.; Bargul, J.L. Detection of Blood Pathogens in Camels and Their Associated Ectoparasitic Camel Biting Keds, Hippobosca Camelina: The Potential Application of Keds in Xenodiagnosis of Camel Haemopathogens. AAS Open Res 2019, 2, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, S.; Chaudhry, H.R.; Chaudhry, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Ali, M.; Jamil, T.; Sial, N.; Shahzad, M.I.; Basheer, F.; Akhter, S.; et al. Prevalence of Common Diseases in Camels of Cholistan Desert, Pakistan. Journal of Infection and Molecular Biology 2014, 2, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobia, M.; Mirza, I.S.; Sonia, T.; Abul, H.; Hafiz, M.A.; Muhammad, D.; Muhammad, F.Q. Prevalence and Characterization of Trypanosoma Species from Livestock of Cholistan Desert of Pakistan. Trop Biomed 2018, 35, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.U.; Muhammad, G.; Gutierrez, C.; Iqbal, Z.; Shakoor, A.; Jabbar, A. Prevalence of Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Equines and Camels in the Punjab Region, Pakistan. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006, 1081, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehseen, S.; Jahan, N.; Qamar, M.F.; Desquesnes, M.; Shahzad, M.I.; Deborggraeve, S.; Büscher, P. Parasitological, Serological and Molecular Survey of Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Dromedary Camels from Cholistan Desert, Pakistan. Parasit Vectors 2015, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Aimen, U.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, A.; Khan, I.; Safiullah; Abidullah; Imdad, S.; Waseemullah; Khan, A. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF TRYPANOSOMIASIS IN THE DROMEDARY CAMELS RAISED IN DERA ISMAIL KHAN, KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, PAKISTAN. Agrobiological Records 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Badshah, F.; Khan, M.S.; Ibáñez-Arancibia, E.; De los Ríos-Escalante, P.R.; Khan, N.U.; Naeem, S.; Manzoor, A.; Tahir, R.; Mubashir, M.; et al. Prevalence of Trypanosomiasis Caused by Trypanosoma Evansi (Kinetoplastea, Trypanosomatidae) in Domestic Ruminants from Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Vet World 2024, 17, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Pakistan Livestock Census 2006; 2006;

- Thrusfield, M.; Christley, R.; Brown, H.; Diggle, P.J.; French, N.; Howe, K.; Kelly, L.; O’Connor, A.; Sargeant, J.; Wood, H. Veterinary Epidemiology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781118280249. [Google Scholar]

- Modrý, D.; Hofmannová, L.; Mihalca, A.D.; Juránková, J.; Neumayerová, H.; D’Amico, G. Field and Laboratory Diagnostics of Parasitic Diseases of Domestic Animals: From Sampling to Diagnosis 2017.

- Hoare, C.A. The Trypanosomes of Mammals: A Zoological Monograph. Medical Journal of Australia 1973, 1, 140–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Ijaz, M.; Farooqi, S.H.; Rashid, M.I.; Khan, A.; Masud, A.; Aqib, A.I.; Hussain, K.; Mehmood, K.; Zhang, H. First Molecular Evidence of Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis in Pakistan. Acta Trop 2018, 180, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, D.M.; Al-Turaiki, I.M.; Altwaijry, N.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alanazi, A.D. Molecular Identification of Trypanosoma evansi Isolated from Arabian Camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Riyadh and Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Animals 2021, 11, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruvot, M.; Kamyingkird, K.; Desquesnes, M.; Sarataphan, N.; Jittapalapong, S. A Comparison of Six Primer Sets for Detection of Trypanosoma Evansi by Polymerase Chain Reaction in Rodents and Thai Livestock. Vet Parasitol 2010, 171, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njiru, Z.K.; Constantine, C.C.; Guya, S.; Crowther, J.; Kiragu, J.M.; Thompson, R.C.A.; Davila, A.M.R. The Use of ITS1 RDNA PCR in Detecting Pathogenic African Trypanosomes. Parasitol Res 2005, 95, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudan, V.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Shanker, D.; Verma, A.K. First Report of Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of RoTat 1. 2 VSG of Trypanosoma Evansi from Equine Isolate. Trop Anim Health Prod 2017, 49, 1793–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K.; Hosmer, D.W. Purposeful Selection of Variables in Logistic Regression. Source Code Biol Med 2008, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y. Molecular Investigation of Important Protozoal Infections in Yaks. The Pakistan Veterinary Journal 2021, 41, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazmand, A. Paleoparasitology and Archaeoparasitology in Iran: A Retrospective in Differential Diagnosis. Int J Paleopathol 2021, 32, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawoz, M.; Jaafar, S.; Alahi, F.; Babur, C. Seroprevalence of Camels Listeriosis, Brucellosis and Toxoplasmosis from Kirkuk Province-Iraq. The Pakistan Veterinary Journal 2021, 41, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.; Alafari, H.A.; Attia, K.; AlKahtani, M.D.F.; Albohairy, F.M.; Elsohaby, I. Prevalence and Animal Level Risk Factors Associated with Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Dromedary Camels. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, K.; Monia, L.; Ameni, B.S.; Haikel, H.; Imed, B.S.; Walid, C.; Bouabdella, H.; Bassem, B.H.M.; Hafedh, D.; Samed, B.; et al. Serological Survey and Associated Risk Factors’ Analysis of Trypanosomiasis in Camels from Southern Tunisia. Parasite Epidemiol Control 2022, 16, e00231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadioli, F.A.; Barnabé, P. de A. ; Machado, R.Z.; Teixeira, M.C.A.; André, M.R.; Sampaio, P.H.; Fidélis Junior, O.L.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Marques, L.C. First report of Trypanosoma vivax outbreak in dairy cattle in São Paulo state, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2012, 21, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Dávila, A. Applications of PCR-Based Tools for Detection and Identification of Animal Trypanosomes: A Review and Perspectives. Vet Parasitol 2002, 109, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Saeed, Z.; Gulsher, M.; Shaikh, R.S.; Ali, M.; Ahmad, A.N.; Hussain, I.; Akhtar, M.; Iqbal, F. A Report on the Molecular Detection and Seasonal Prevalence of Trypanosoma Brucei in Dromedary Camels from Dera Ghazi Khan District in Southern Punjab (Pakistan. Trop. Biomed 2016, 33, 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Birhanu, H.; Gebrehiwot, T.; Goddeeris, B.M.; Büscher, P.; Van Reet, N. New Trypanosoma Evansi Type B Isolates from Ethiopian Dromedary Camels. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10, e0004556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ereqat, S.; Nasereddin, A.; Al-Jawabreh, A.; Al-Jawabreh, H.; Al-Laham, N.; Abdeen, Z. Prevalence of Trypanosoma evansi in livestock in Palestine. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan-Kadle, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Nyingilili, H.S.; Yusuf, A.A.; Vieira, T.S.W.J.; Vieira, R.F.C. Parasitological, Serological and Molecular Survey of Camel Trypanosomiasis in Somalia. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamman, S.A.; Dakul, D.A.; Yohanna, J.A.; Dogo, G.A.; Reuben, R.C.; Ogunleye, O.O.; Tyem, D.A.; Peter, J.G.; Kamani, J. Parasitological, Serological, and Molecular Survey of Trypanosomosis (Surra) in Camels Slaughtered in Northwestern Nigeria. Trop Anim Health Prod 2021, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boushaki, D.; Adel, A.; Dia, M.L.; Büscher, P.; Madani, H.; Brihoum, B.A.; Sadaoui, H.; Bouayed, N.; Kechemir Issad, N. Epidemiological Investigations on Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Dromedary Camels in the South of Algeria. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Afaleq, A.I.; Elamin, E.A.; Fatani, A.; Homeida, A.G.M. Epidemiological Aspects of Camel Trypanosomosis in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Camel Practice and Research 2015, 22, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naga, T.; Barghash, S. Blood Parasites in Camels (Camelus Dromedarius) in Northern West Coast of Egypt. J Bacteriol Parasitol 2016, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, G.; Jabbar, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Athar, M.; Saqib, M. A Preliminary Passive Surveillance of Clinical Diseases of Cart Pulling Camels in Faisalabad Metropolis (Pakistan). Prev Vet Med 2006, 76, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, T.; Tipu, M.Y.; Aslam, A.; Ahmed, S.; Abid, S.A.; Iqbal, A.; Akhtar, N.; Saleem, M.; Mushtaq, A.; Umar, S. Hematobiochemical Disorder in Camels Suffering from Different Hemoparasites. Pak J Zool 2019, 51, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, B.; Gadahi, J.A.; Shah, G.; Dewani, P.; Arijo, A.G. Field Investigation on the Prevalence of Trypanosomiasis in Camels in Relation to Sex, Age, Breed and Herd Size. Pak. Vet. J 2010, 30, 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood, N.; Tunio, M.; Dad, R. Effect of Season and Topography on the Prevalence of Trypanosoma Evansi in Camels of District Khushab of Punjab Province, Pakistan. Journal of Animal Health and Production 2023, 11, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Hafeez, M.A.; Lateef, M.; Awais, M.; Wajid, A.; Shah, B.A.; Ali, S.; Asif, Z.; Ahmed, M.; Kakar, N.; et al. Parasitological, Molecular, and Epidemiological Investigation of Trypanosoma Evansi Infection among Dromedary Camels in Balochistan Province. Parasitol Res 2023, 122, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazmand, A.; Rasooli, A.; Nouri, M.; Hamidinejat, H.; Hekmatimoghaddam, S. Serobiochemical Alterations in Subclinically Affected Dromedary Camels with Trypanosoma Evansi in Iran. Pak. Vet. J 2011, 31, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Habeeba, S.; Khan, R.A.; Zackaria, H.; Yammahi, S.; Mohamed, Z.; Sobhi, W.; AbdelKader, A.; Alhosani, M.A.; Muhairi, S. Al Comparison of Microscopy, Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosoma Evansi, and Real-Time PCR in the Diagnosis of Trypanosomosis in Dromedary Camels of the Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE. J Vet Res 2022, 66, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitoun, A.M.A. ; Safaa, ; Malek, S. ; Khaled, ; El-Khabaz, A.S.; Abd-El-Hameed, S.G. SOME STUDIES ON TRYPANOSOMIASIS IN IMPORTED CAMELS. Assiut Vet Med J 2016, 63, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, S.S.; Megahed, G.; Al-Hakami, A.M.; Tolba, M.E.M.; Karar, Y.F.M. Impact of Trypanosomiasis on Male Camel Infertility. Front Vet Sci 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghash, S.M.; Abou El-Naga, T.R.; El-Sherbeny, E.A.; Darwish, A.M. Prevalence of Trypanosoma Evansi in Maghrabi Camels (Camelus Dromedarius) in Northern-West Coast, Egypt Using Molecular and Parasitological Methods. Acta Parasitol. Glob 2014, 5, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshekar, F.; Yakhchali, M.; Shariati-Sharifi, F. Trypanosoma Evansi Infection and Major Risk Factors for Iranian One-Humped Camels (Camelus Dromedarius). Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2017, 41, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.A.; Robertson, I.; Mohamed, A. Prevalence and Distribution of Trypanosoma Evansi in Camels in Somaliland. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019, 51, 2371–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argungu, S.; Bala, A.; Liman, B. Pattern of Trypanosoma Evansi Infection among Slaughtered Camels (Camelus Dromedarius) in Sokoto Central Abattoir. . J Zool BioSci Res 2015, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ngaira, J.; Bett, B.; Karanja, S.; Njagi, E. Evaluation of Antigen and Antibody Rapid Detection Tests for Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Camels in Kenya. Vet Parasitol 2003, 114, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Malki, J.S.; Hussien, N.A. Molecular Characterization of Trypanosoma Evansi, T. Vivax and T. Congolense in Camels (Camelus Dromedarius) of KSA. BMC Vet Res 2022, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharusi, A.H.; Elshafie, E.I.; Ali, K.E.M.; AL-Sinadi, R. ; N. , B.; AL-Saifi, F. Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma Evansi Infections among Dromedary Camels (Camelus Dromedaries) in North Al-Sharqiya Governorate, Sultanate of Oman. Journal of Agricultural and Marine Sciences 2025, 26, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, G.; Abebe, R. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Trypanosomosis in Dromedary Camels in the Pastoral Areas of the Guji Zone in Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Holzmuller, P.; Lai, D.H.; Dargantes, A.; Lun, Z.R.; Jittaplapong, S. Trypanosoma Evansi and Surra: A Review and Perspectives on Origin, History, Distribution, Taxonomy, Morphology, Hosts, and Pathogenic Effects. Biomed Res Int 2013.

- Ngaira, J.; Bett, B.K.; Karanja, S. Animal-Level Risk Factors for Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Camels in Eastern and Central Parts of Kenya. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2002.

- Ismail-Hamdi, S.; Hamdi, N.; Chandoul, W.; Smida, B. Ben; Romdhane, S. Ben Microscopic and Serological Survey of Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Tunisian Dromedary Camels (Camelus Dromedarius). Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasalary, M.; Arbabi, M.; Pashei, S.; Abdigoudarzi, M. Fauna of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) and their seasonal infestation rate on Camelus dromedarius (Mammalia: Camelidae) in Masileh region, Qom province, Iran. Persian J. Acarol 2017, 6, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, Z.I.; Iqbal, J. Incidence, Biochemical and Haematological Alterations Induced by Natural Trypanosomosis in Racing Dromedary Camels. Acta Trop 2000, 77, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.R.; Senapati, S.; Sahoo, S.C.; Das, M.; Sahoo, G.; Patra, R. Trypanosomiasis Induced Oxidative Stress and Hemato-Biochemical Alteration in Cattle. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud 2017, 5, 721–727. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, B.S.; Kumari, K.N.; Sivajothi, S.; Rayulu, V.C. Haemato-Biochemical and Thyroxin Status in Trypanosoma Evansi Infected Dogs. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2016, 40, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivajothi, S.; Rayulu, V.C.; Sudhakara Reddy, B. Haematological and Biochemical Changes in Experimental Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Rabbits. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2015, 39, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi-hamedani, M.; Ghazvinian, K.; Darvishi, M.M. Hematological and Serum Biochemical Aspects Associated with a Camel (Camelus Dromedarius) Naturally Infected by Trypanosoma Evansi with Severe Parasitemia in Semnan, Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2014, 4, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Singh, V.K.; Kumari, P.; Nakade, U.P.; Garg, S.K. Trypanosoma Evansi Induces Detrimental Immuno-Catabolic Alterations and Condition like Type-2 Diabetes in Buffaloes. Parasitol Int 2018, 67, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.S.; Wolkmer, P.; Costa, M.M.; Tonin, A.A.; Eilers, T.L.; Gressler, L.T.; Otto, M.A.; Zanette, R.A.; Santurio, J.M.; Lopes, S.T.A.; et al. Biochemical Changes in Cats Infected with Trypanosoma Evansi. Vet Parasitol 2010, 171, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer | Primer Sequence (5’ To 3’) |

Expected Product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS1CF/BR | F:(CCGGAAGTTCACCGATATTG) R:(TTGCTGCGTTCTTCAACGAA) | 480 | Metwally et al., 2021 |

| pMUTec | F: (TGCAGACGACCTGACGTACT) R:(CTCCTAGAAGCTTCGGTGTCCT) |

227 | Pruvot et al., 2010 |

| RoTat 1.2 | F:(GCGGGGTGTTTAAAGCAATA) R: (ATTAGTGCTGCGTGTGTTCG) |

205 | Njiru et al., 2005 |

| PCR | Microscopy | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| Negative | Count | 316 | 25 | 341 |

| Expected Count | 312.9 | 28.1 | 341.0 | |

| Positive | Count | 51 | 8 | 59 |

| Expected Count | 54.1 | 4.9 | 59.0 | |

| Total | Count | 367 | 33 | 400 |

| Expected Count | 367.0 | 33.0 | 400.0 | |

| Comparison | Observed Agreement | SE | Kappa Value | 95% CI of Kappa | Χ2 p-value | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Vs MS | 81.00% | 0.057 | 0.076 | -0.357, 0.188 | 0.108 | Slight |

| Variable | Category | Pos./Tested | Prev. % (95% CI) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial Zones | Northern & Central | 25/225 | 11.1 (7.3-16) | Ref. | χ2 = 5.416 p = 0.020 |

| Southern | 34/175 | 19.4 (13.8-26.1) | 1.93 (1.10-3.38) | ||

| Gender | Female | 46/251 | 18.3 (13.7-23.7) | 2.35 (1.22-4.51) | χ2 = 6.855 p = 0.009 |

| Male | 13/149 | 8.7 (4.7-14.5) | Ref. | ||

| Age Groups | < 2 Y | 10/87 | 11.5 (5.7-20.1) | Ref. | χ2 = 1.488 p = 0.475 |

| 2-5 Y | 21/149 | 14.1 (8.9-20.7) | 1.26 (0.57-2.82) | ||

| > 5 Y | 28/164 | 17.1 (11.7-23.7) | 1.59 (0.75-3.59) | ||

| Tick Infestation | No | 16/192 | 8.3 (4.8-13.2) | Ref. | χ2 = 12.090 p = 0.001 |

| Yes | 43/208 | 20.7 (15.4-26.8) | 2.87 (1.56-5.29) | ||

| Wall Cracks | No | 37/276 | 13.4 (9.6-18) | Ref. | χ2 = 1.279 p = 0.258 |

| Yes | 22/124 | 17.7 (11.5-25.6) | 1.39 (0.78-2.48) | ||

| Contact with other Livestock | No | 16/134 | 11.9 (7-18.7) | Ref. | χ2 = 1.265 p = 0.261 |

| Yes | 43/266 | 16.2 (12-21.2) | 1.42 (0.77-2.63) | ||

| Physical appearance | Emaciated | 51/307 | 16.6 (12.6-21.3) | 2.12 (0.97-4.64) | χ2 = 3.642 p = 0.056 |

| Normal | 8/93 | 8.6 (3.8-16.2) | Ref. | ||

| Housing Management | Sand based | 42/214 | 19.6 (14.5-25.6) | 2.43 (1.33-4.43) | χ2 = 8.702 p = 0.003 |

| Soil based | 17/186 | 9.1 (5.4-14.2) | Ref. | ||

| Fly Control | No | 42/296 | 14.2 (10.4-18.7) | Ref. | χ2 = 0.285 p = 0.594 |

| Yes | 17/104 | 16.4 (9.8-24.9) | 1.18 (0.64-2.18) | ||

| Location of Feed & Water | Indoor | 13/125 | 10.4 (5.7-17.1) | Ref. | χ2 = 2.736 p = 0.098 |

| Outdoor | 46/275 | 16.7 (12.5-21.7) | 1.73 (0.89-3.33) | ||

| Purpose | Draught | 33/190 | 17.4 (12.3-23.5) | 1.49 (0.85-2.60) | χ2 = 1.973 p = 0.160 |

| Production | 26/210 | 12.4 (8.2-17.6) | Ref. | ||

| Herd Size | <= 3 | 27/153 | 17.7 (12-24.6) | Ref. | χ2 = 2.127 p = 0.546 |

| 4 to 6 | 11/99 | 11.1 (5.7-19) | 0.58 (0.28-1.24) | ||

| 7 to 10 | 12/87 | 13.8 (7.3-22.9) | 0.75 (0.36-1.56) | ||

| > 10 | 9/61 | 14.8 (7-26.2) | 0.81 (0.36-1.84) |

| Variable Name | Exposure Variable | Comparison | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial Zones | Southern Punjab | Northern & Central Punjab | 1.9 | 1.05-3.35 | 0.034 |

| Gender | Female | Male | 2.2 | 1.11-4.24 | 0.023 |

| Tick Infestation | Yes | No | 2.6 | 1.37-4.79 | 0.003 |

| Housing Management | Sand Based | Soil Based | 2.2 | 1.16-3.99 | 0.01 |

| Parameters | Positive (n=59) | Negative (n=341) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Protein (g/dl) | 05.51 ± 0.05 | 06.77 ±0.08 | <0.01 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 02.77 ± 0.04 | 03.65±0.04 | <0.01 |

| Globulin (g/dl) | 02.57 ± 0.06 | 03.12 ±0.08 | <0.01 |

| A\G Ratio | 01.13 ± 0.04 | 01.18 ±0.03 | 0.319 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).