1. Introduction

Diseases transmitted through ticks are now regarded as an emerging problem around the globe. One such important and commonly known cosmopolitan tick-borne rickettsia disease is Canine Ehrlichiosis, with the first official report coming from Algeria in 1935 (Donatien and Lestoquard, 1935). This disease is prevalent in both tropical and sub-tropical climates because of the hot and humid conditions that favour its occurrence, referred to as tropical canine pancytopenia. Ehrlichia canis, an obligate intracytoplasmic gram-negative pleomorphic rickettsia organism of family Anaplasmataceae (Selim et al., 2020), is the primary etiological agent for canine ehrlichiosis. Transmission mainly occurs by Riphicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick (Azevedo et al., 2011). Among all the Ehrlichia species, E. canis is studied primarily in its widespread prevalence in the canine population (Oliveira et al., 2000; Lorsirigool and Pumipuntu, 2020). Most of the clinical signs in affected dogs were non-specific and overlapping, making clinical diagnosis difficult.

The animals having an acute phase show symptoms like lethargy, fever, dullness, nasal bleeding, petechial haemorrhage, myalgia, bruising, and loss in weight, along with conditions including hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, ascites, nephritis and other cardiorespiratory and haematological disorders (Silva et al., 2016; Selim et al., 2020). The most common haematological finding in Canine Ehrlichiosis is anaemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia (Silva et al., 2016). During the chronic stage, pancytopenia becomes the most characteristic finding, probably due to the destruction and impairment of bone marrow function (Selim et al., 2021). Affected dogs show altered serum biochemical parameters predominantly indicative of hepatic (Niwetpathomwat et al., 2006) and renal dysfunction (Silva et al., 2016). On ultrasonography, hyperechogenicity of the liver is observed in most of the positive cases, along with hepatomegaly (Angkanaporn et al., 2022). Ehrlichiosis is a multi-systemic disease; necropsy of the affected dogs revealed hepatomegaly, generalised lymphadenopathy, contracted kidney and petechial to ecchymotic haemorrhages in visceral organs (Lakkawar et al., 2003; Waner and Harrus, 2013).

Diagnosis of Ehrlichiosis was most often made by demonstrating morulae within the cytoplasm of monocytes through blood smear examination, whose sensitivity and specificity depend upon loads of parasites in the blood (Parmar et al., 2013). Detection of intracytoplasmic E. canis morulae in monocytes is more accessible during the acute stage of infection but quite tricky in sub-acute and chronic stages (Parmar et al., 2013). Haemato-biochemical alterations and ultrasonographic changes can help support the clinical signs and assist in reaching a preliminary diagnosis (Oliveira et al., 2000; Bai et al., 2017). Detection of DNA of E. canis through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from blood and tissue is regarded as the most sensitive and confirmatory diagnosis (Nakaghi et al., 2008). There is a scarcity of available literature on Canine Ehrlichiosis in Odisha. Given the widespread and growing prevalence of CME, a multisystemic disease in dogs that poses a significant threat to canines globally, this study aims to assess various epidemiological risk factors, haemato-biochemical alterations, pathological changes along with molecular confirmation of E. canis to raise awareness among pet owners and veterinarians in the state.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Area and Ethical Approach

During the time point between March and December 2022, pet dogs (n=178) presented to the Veterinary Clinical Complex (VCC) of the Veterinary College of the State (OUAT), located at Smart City Bhubaneswar, Odisha (20.1863° N, 85.6223° E of India) were screened for Canine ehrlichiosis. Blood samples were collected after obtaining due consent from the pet owners for clinical investigations and stored at -80º C for further molecular confirmation through PCR. Blood and buffy coat smears were prepared and stained with Giemsa protocol to observe morulae in leucocytes through direct microscopy for initial screening, besides the history of tick infestations and other clinical signs related to Ehrlichiosis.

2.2. Epidemiological Risk Factors

A questionnaire was prepared to record the details of presented dogs from the pet owners related to their ages, sex, breed, type of housing, etc., which was later analysed statistically by applying the Chi-square test using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA) to find out the level of significant association between each risk factors influencing the occurrence of Canine Ehrlichiosis.

2.3. Haemato-Biochemical Examinations

Blood collected from 178 dogs (Control-122, Affected-56) for routine haematology and serum biochemical study, processed through the automatic haematological analyser (Medonic M51, Sweden) and by the automated serum biochemical analyser (CPC, i-track, USA) present at the veterinary clinical complex (VCC) in the college. The data recorded for various haemato-biochemical parameters were analysed by using SAS software (Local, W32_7PRO) through student’s t-test to observe any differences between infected and control groups. A p≤ 0.05 value was accepted as statistically significant.

2.4. Molecular Confirmation through PCR, Sequencing, and Phylogenetic Study

Molecular detection of

Ehrlichia canis organism was performed by targeting the p28 gene using conventional PCR (Nakaghi

et al., 2010). DNA was isolated from whole blood using a QIAamp DNA mini kit. The 16s rRNA gene of

Ehrlichia spp. was amplified in the thermal cycler using a reaction mixture containing specially designed primers to amplify the 843 bp fragment from the p28 gene. The primers used were ECp28-F (f) 5’-ATGAATTGCAAAAAAATTCTTATA-3’ and ECp28-R (r) 5’-TTAGAAGTTAAA TCTTCC TCC-3’. Temperature time Protocol in the Proflex PCR system (Invitrogen, USA) was listed in

Table 1. The product obtained from PCR was taken as the representative sample for

Ehrlichia canis parasite and was sent for sequencing at ILS (Institute of Life Science) Bhubaneswar. Sequencing was performed using Sanger method in Automated DNA sequences. Bio Edit programme was used for trimming the sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the sequencing results. The analysis was performed through BLAST using the website

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST. The sequences were aligned with similar sequences from India and other countries retrieved from the NCBI database using MEGAX software, followed by phylogenetic tree construction using the neighbour-joining method with a bootstrap value of 1000 (Kumar et al., 2018).

2.5. Ultrasonography

Two-dimensional B-mode ultrasonography was conducted among positively screened dogs (n=56) using LOGIQ F8 Expert in the imaging unit located in the veterinary clinical complex. One 8C curvilinear probe was used in most patients with a frequency range of 3.0 – 10.0 MHz. Ultrasonographic images are primarily intended to observe any systemic alterations like hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, presence or absence of ascitic fluid, etc., in affected dogs, which will be helpful in correlating with other haemato-biochemical alterations.

2.6. Identification of Ticks through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The ticks were collected by forceps without damaging mouthparts and appendages and were put in labeled sterile plastic vials. In some cases, an attempt was made for Scanning electron microscopy (S-3400, Hitachi) in the Central Instrumentation Facility (CIF) of OUAT for further identification. A 5.00 KV voltage and distance varying from 9.8 mm to 10.0mm with magnification ranging from X40 SE to X 250 SE were used during scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

2.7. Pathology

Necropsy was conducted for three dogs who died during the study period to record the characteristic morbid changes. Demonstrative tissue samples were collected and fixed in 10% neutral formalin for further processing in the Department of Veterinary Pathology to observe histopathological changes.

3. Results

Out of the total dogs (n=178) screened, 56 were found positive either through peripheral blood and buffy coat examinations or molecular confirmation through PCR, giving a prevalence rate of 31.46%. Three ehrlichiosis-positive dogs succumbed even after due treatment, giving a mortality rate of 1.68% and a case fatality rate of 5.35%. Preliminary screening through direct microscopy by observing the presence of any dark blue compact inclusions or morulae in leucocytes of the Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears and buffy coat smears recorded an overall prevalence of 3.93% (n=7) and 10.11% (n=18) respectively. Most of the morula stages were prominent in monocytes (

Figure 1A); however, it was also present in the cytoplasm of lymphocytes and neutrophils (

Figure 1B), as observed in the present study.

3.1. Epidemiological Risk Factors

Details of epidemiological risk factors and their association with the occurrence of canine ehrlichiosis are listed in

Table 2. Statistical analysis through the

Chi-square test showed a non-significant (p ≥0.05) association for the breed, sex, housing pattern, body weight, and season in incidences of ehrlichiosis in dogs, which were corroborative through their odds ratio, as indicated in

Table 2. However, the occurrence of canine ehrlichiosis significantly varied among different age groups of dogs.

Clinical Signs

Typical signs manifested in positively screened dogs were epistaxis (46.4%,

Figure 2A), hind limb oedema (16.07%), distended abdomen suggestive of ascites (26.78%) with some non-typical signs like corneal opacity (

Figure 2B), uveitis and icteric sclera. However, most of the dogs showed non-specific symptoms like fever (75%), lethargy (100%), in-appetence (69.64%), diarrhoea (8.92%), dullness, etc., making the diagnosis a challenge for the field veterinarians. In one severely affected case, facial oedema (

Figure 2C), haemoptysis, and melena were also noticed. Physical examinations of hair coat in most affected dogs revealed mild to moderate tick infestations (

Figure 2D).

3.2. Haemato-Biochemical Parameters

A comparative analysis was done for the haematological parameters among the dogs screened positive (n=56), with the dogs found negative for Ehrlichia (n=122), as depicted in

Table 3. Statistical analysis through

Student’s t-test showed that there was a significant decrease (p ≤ 0.05) in the values of Hb, TLC, PCV, platelet count along with neutrophilia and relative leukopenia observed through differential leucocyte count (DLC) in the ehrlichiosis affected dogs. The serum biochemical alterations observed in the present study are presented in Table 4.

Student’s t-test showed a significant (P≤ 0.05) decrease in the albumin levels with a relative increase in the globulin level and an overall reduction in total protein levels. Other biochemical parameters, including BUN, creatinine, AST, and ALT, observed an increase in the levels indicating liver and kidney anomalies in diseased dogs.

Urine Examination

A detailed chemical examination of urine samples collected from dogs screened positive for Ehrlichiosis (n=56) recorded proteinuria (69.64%, n=39) and haematuria (10.71%) as a consistent finding. Urine samples from most cases (83.92%, n=47) also showed positive for bile salt and protein levels in affected dogs. There was no change in the pH of the urine samples both in affected and control dogs, which shows an acidic reaction to pH paper.

3.3. Ultrasonography

Hepatomegaly (n=7, 12.5%) and distended gall bladder were observed during ultrasonography, corroborating hepatopathy in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs. Enlargement of the hepatic artery and vein was noticed through ultrasonography in affected dogs. Dogs suffering from ascites (n=4, 7.14%) showed the presence of hypoechoic to anechoic fluid with floating organs in the abdominal cavity. Splenomegaly was a significant finding, consistently seen in 79% of the affected dogs. Ultrasonography of the kidneys in affected dogs showed mild to moderate hyperechogenic structures suggestive of nephropathy leading to hyperechogenicity, a persistent finding in 25% (n=14) of the positive cases.

3.4. Pathology

3.4.1. Gross Pathology

The dogs died had poor and rough body coats with the presence of ticks on their skin, pale to icteric conjunctiva, petechiae to ecchymotic haemorrhages, and/or congested oral mucosae (

Figure 3A) with evidence of nasal bleeding/epistaxis, and presence of scabs in the muzzle. Oedema in the right hind limb was noticed in two carcasses (

Figure 3B). Some of the most typical gross lesions included an enlarged spleen and liver. One out of the total 3 dogs who died also had blood-tinged ascitic fluid in the abdominal cavity. The eyes in affected dogs showed a cloudy appearance, as evidenced during the necropsy. There was hepatomegaly as well as congestion with a distended gall bladder in two cases. At the same time, in one, the liver was icteric with foci of yellow discoloration (

Figure 3C). Frothy exudates were found in the upper respiratory tract of the two dogs, with lungs showing typically pneumonic and consolidation. Generalized ecchymotic haemorrhages were present in the liver parenchyma. Kidneys were nodular, contracted with few necrotic patches on the cortical surface along with firm consistency. Capsules do not easily peel off while removed from the cortex, showing granularity on the cortical surfaces suggestive of nephritis. Most lymph nodes, such as the popliteal, mediastinal, etc., were typically enlarged and congested. Other organs like the gall bladder and urinary bladder were distended and revealed mild to moderate haemorrhages in the serosa surface (

Figure 3D). There were petechiae to ecchymotic haemorrhages in different organs like the intestine, heart, and lungs, as well as on the intestinal serosa surface.

3.4.2. Histopathology

Microscopic lesions in liver parenchyma mainly predominated by vacuolar to fatty degenerations, necrosis of hepatocytes around the central vein (

Figure 4A), severe diffuse tri-adenitis in the portal triads along with centrilobular degeneration, and sinusoidal congestion. Multifocal necrosis and degenerations were clearly evident around the central veins of the liver. The liver showed hepatitis with pan-lobular hepatic and fatty degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes with disorganization of hepatic chords. The kidney also showed periglomerular oedema and focal necrosis with cellular infiltration. The corticomedullary junctions showed plasma cell infiltration. There was also evidence of glomerular necrosis with increased bowman’s space and condensed glomerular tuft. Necrosis of renal tubular epithelial cells with desquamation and the presence of homogenous proteinaceous casts in renal tubules were noticed (

Figure 4B). Infiltrations of mononuclear cells in the inter-tubular spaces and fibrotic proliferation were observed in microscopy. There was the presence of a homogenous proteinaceous pink colour renal tubular cast with intertubular congestion. Besides, there were sub-capsular infiltrations as well as perivascular infiltrations of inflammatory cells, vasculitis with thickened arterioles with proliferation of arteriolar wall. Lungs were characterized by interstitial pneumonia with marked fibrosis in the alveolar septum as well as in and around the lung tissue. There was interstitial congestion and thickening of interalveolar septa. There was alveolar degeneration and necrosis along with interstitial congestion and oedema of interstitial spaces (

Figure 4C). In the lymph nodes, medullary oedema was prominent, along with plasma cytolysis and follicular hyperplasia. In some cases, we noticed lymphoid follicular depletion as a significant histologic finding in affected dogs. Histological lesions related to diffuse haemosiderosis were detected in splenic sections (

Figure 4D).

3.5. Identification of Ticks through Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The scanning electron microscopic study of the ticks collected from the Ehrlichiosis screened dogs revealed the presence of

Rhipicephalus sanguineus, determined by the presence of hexagonal basis capitulum (

Figure 5A), brevirostrate mouth parts, coxa 1 with two spurs, presence of festoons, anal plates and anal grooves surrounding anus posteriorly (

Figure 5B).

3.6. Molecular Confirmation through PCR

All 56 dogs that tested positive through blood and buffy coat smear examinations and clinical examinations had their blood samples sent for PCR examination for molecular conformation of the

Ehrlichia organism. Among the various diagnostic procedures, the sensitivity and specificity of PCR were highest, revealing 49 positives, showing a prevalence of 87.5%. After DNA extraction following the protocol, the extracted DNA was amplified using

Ehrlichia canis-specific primers targeting the p28 gene in the thermocycler. The PCR products were analysed using agarose gel electrophoresis; the bands were visualized at 843 bp, indicating the presence of the parasite (

Figure 6).

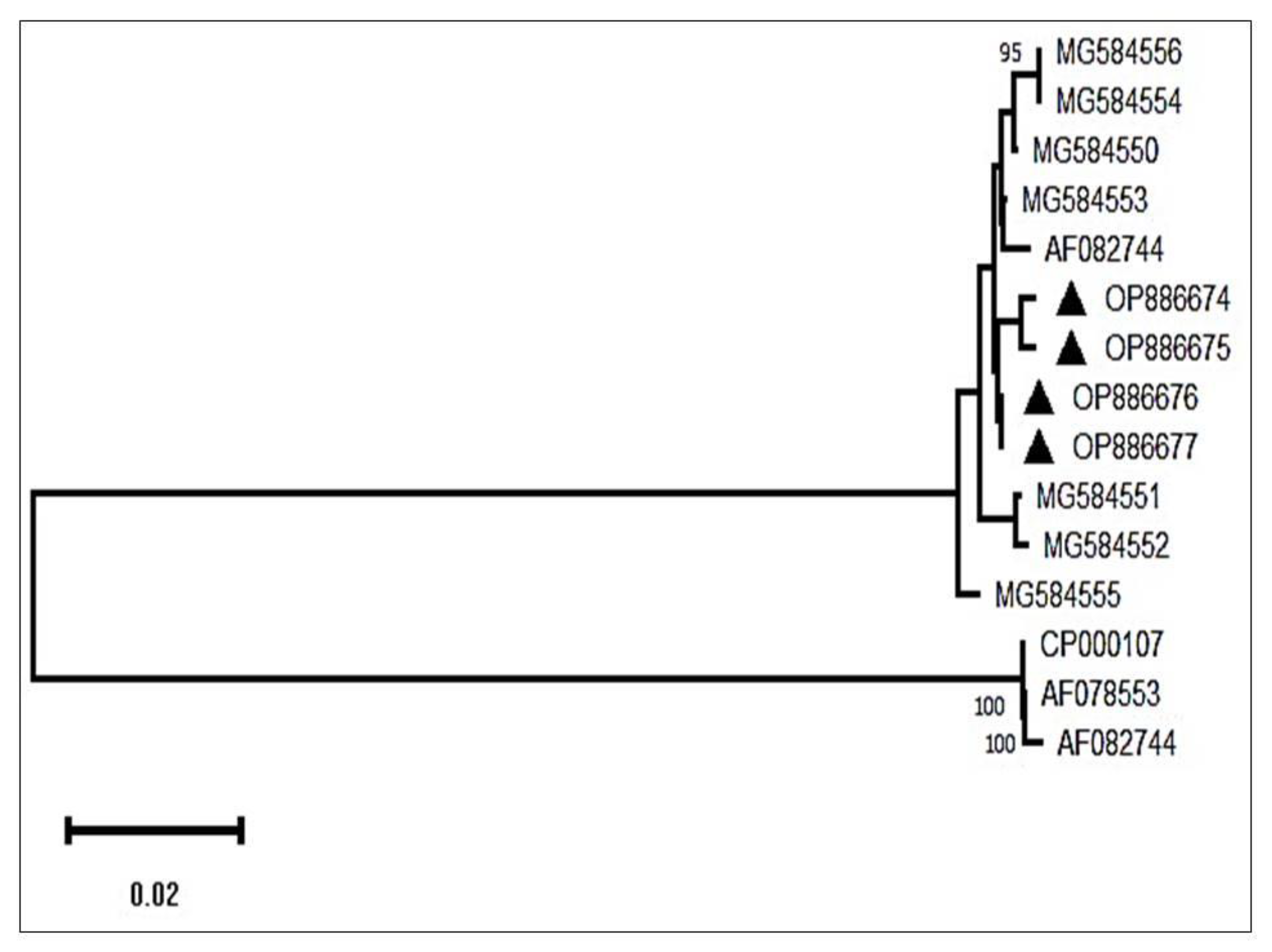

3.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

Using BLAST analysis, the sequences were retrieved from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database targeting the P28 gene of the parasite. A phylogenetic tree constructed to study the evolutionary relationship revealed that the isolates obtained formed a completely different clade than the existing ones. The isolates of the present investigation revealed similarity with the isolate derived from USA with 100% similarity. The sequence results were sent to the NCBI database, and the following accession numbers were allotted, such as OQ383671-OQ383674 and OQ383671-OQ383674, depicted as a black triangle in the Phylogenetic tree (

Figure 7).

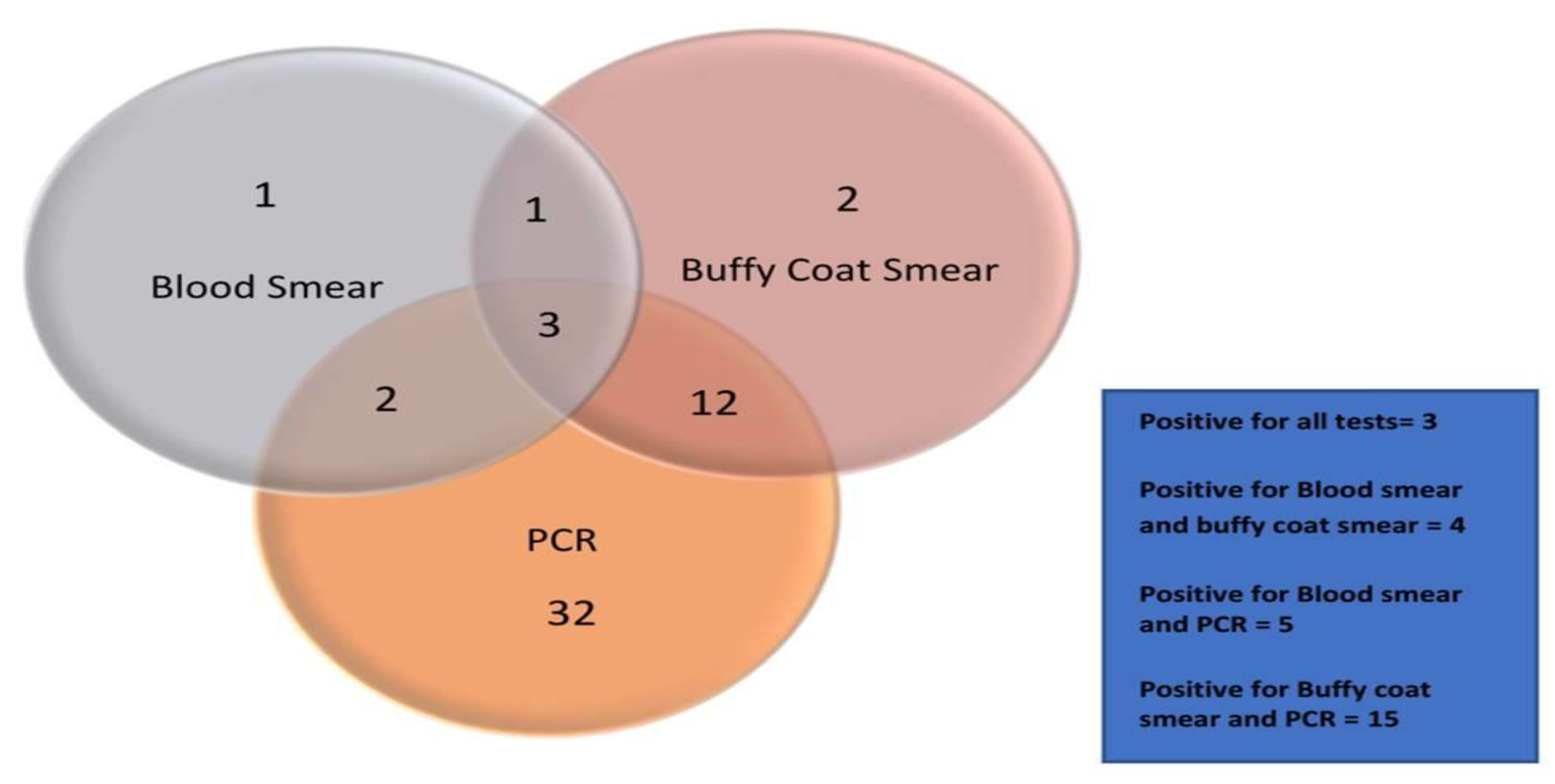

3.8. Comparative Analysis of the Tests

Out of the total 178 dogs under study, 56 canine blood samples were screened positive using one of the three diagnostic procedures. Out of 56 positively screened samples, only seven samples were screened positive by blood smear examination (12.5%), while eighteen samples with buffy coat smear examination (32.14%) and forty-nine samples from PCR (87.5%) were identified positive respectively (Chart-1). A relationship had been studied among the tests. Four of the positively screened samples had been positive for both blood smear and buffy coat smear (7.14%). Only five samples were positive by blood smear and PCR (8.92%). Similarly, fifteen samples were screened positive by both buffy coat smear and PCR (26.78%), whereas only three were identified positive with all three tests conducted (5.35%).

4. Discussion

The present study recorded a higher prevalence rate of 31.46% Canine Ehrlichiosis in and around Bhubaneswar, Odisha with a mortality rate of 1.68% and case fatality rate is of 5.35% which corroborates with the findings of Angkanaporn et al. (2022). The tropical climate at Bhubaneswar mostly favours vector development as well as transmission among susceptible population (Costa Jr et al., 2007) attributing a higher prevalence. The low sensitivity of detecting the morulae through blood smear examination, as evident in the present study might be associated with low parasitaemia and variability in the stage of infection in the host body (Parmar et al., 2013). Guedes et al. (2015) mentioned that morula is, however visible only in the acute phase of the disease during higher parasitaemia. This statement justifies the lower positivity rates obtained during our study by the blood and buffy coat smear examinations. Although most of the morula stages are visible in the monocyte hence the name is canine monocytic Ehrlichiosis, however according to our findings, morula stages were also evident in neutrophils and lymphocytes as well. Similar findings were reported by Selim et al. (2020).

Although there is no strict age-based predilection, the younger animals are more susceptible due to the less developed immune response and a sudden decrease in the maternal antibodies after 3 months of age (Milanjeet et al., 2014). Our findings of higher occurrences in males could be justified because males have a bigger sample size and are more prone to more tick infestation due to their aggressive behavioural attributes as stated by Okubanjo et al. (2014). Pet owners mostly prefer to keep male dogs attributed to the higher prevalence’s of Ehrlichiosis in present study (Bai et al., 2017). The reason why the heavier breeds are more prone to the occurrence of Ehrlichiosis could be endorsed to the fact that the larger breed dogs have more surface area and good body condition and have less immunity than the local non-descript breed due to which they frequently suffer from tick infestation and eventually become prone to Ehrlichiosis. Out of other heavy breeds, the German Shepherd is the most susceptible due to their inherent breed inability of blast formation and leucocyte migration inhibition factor as stated by Bharadwaj et al. (2013); Himalini et al. (2015) and Bhadesiya and Rawal (2015).

Higher occurrences of Ehrlichiosis in the Labrador breed in present study attributed to heavy hair coat which often go un-noticed to most of the pet owners thus making them more susceptible for easy stay and transmission of the disease (Himalini et al., 2018). The heavyweight of any animal makes them more vulnerable to parasitic and mainly ticks infestation due to its larger body area, which further acts as a good source of nutrition for the parasite. Our observations about housing conditions were in agreement with the findings reported by Bhadesia and Raval (2015) attributed to maximum tick exposure in outside environment. Riphicephalus ticks are more common in urban areas, which correlates with our findings (Labruna & Pereira, 2001 and O’Dwyer, 2000). These observations could be justified since the tick population thrives best during the hot and humid conditions favouring tick development by increasing the chances of laying and hatching eggs and nymphal moulting (Dantas-Torres F. 2010). The symptoms observed in our study were in agreement with Tuna et al. (2019) and Haritha et al. (2018). The symptoms like fever are consistently found in the majority of dogs because of an increased production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) by antigen-presenting cells and B-cells or exogenous pyrogen products of the rickettsia organism, as stated by Rungsipipat et al. (2009).

Most of the affected animals in our study showed normocytic normochromic type of anaemia attributed to immune-mediated disorders and suppression of bone marrow, as reported by Thongsahuas et al. (2020) and Siarkou et al. (2007). Anaemia observed in the acute stage is credited to increased platelet consumption, vasculitis, and splenic sequestration; however, in the chronic stage, it occurs mainly due to bone marrow hypoplasia leading to pancytopenia, as justified by Angkanaporn et al. (2022). The increased value of ALT and AST is indicative of hepatic involvement in the pathogenesis of Canine Ehrlichiosis. Further, the elevated levels of BUN and creatinine justified the renal apathy during the course of the disease. Hypergammaglobulinemia is a consistent feature of Canine Ehrlichiosis, however the levels of globulin do not correlate with the levels of antibodies of E. canis indicating that most of the globulins responsible for the total increase in gamma globulin were not antibody to E. canis (Buhles et al., 1974). Serum biochemical alterations related to increased BUN and creatinine levels corroborate with nephropathy in the present study.

It was found that Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Brown dog tick) was an important vector responsible for the transmission of this disease in this area, morphologically identified through a Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) study. Present findings corroborate earlier researchers such as Kottadamane et al. (2017) and Neave et al. (2022). Bhubaneswar climatic condition is more or less similar to the tropical climates with hot and humid conditions favouring the tick multiplication and disease transmission among susceptible dogs (Angkanaporn et al., 2022).

Hepatomegaly, gall bladder distension, and the presence of clear/ sludge bile were observed as a typical finding because of the anorectic condition of the affected dogs in canine ehrlichiosis (Kumar et al. 2012). Ultra-sonographic findings recorded in the present study corroborated earlier reports of Angkanaporn et al. (2022). The necropsy lesions were consistent with the findings reported by Behera et al. (2012). Splenomegaly as a characteristic finding similar to our observations owing to the fact that spleen act as a significant organ for harbouring Ehrlichia infected macrophages which eventually leads to destruction of platelets (Faria et al. 2011). Similar findings in histopathological analysis were also reported by Mylonakis et al. (2010) and Waner et al. (2013).

The PCR has been proven to be the most accurate, quick, and convenient method of diagnosis with the highest specificity and sensitivity as compared to the other approaches used (Sukasawat et al. 2000). Nakaghi et al. (2008) stated the high specificity of PCR can be accounted for its ability to detect Ehrlichia DNA with ricketsaemia as low as one infected monocyte in 1036 cells.

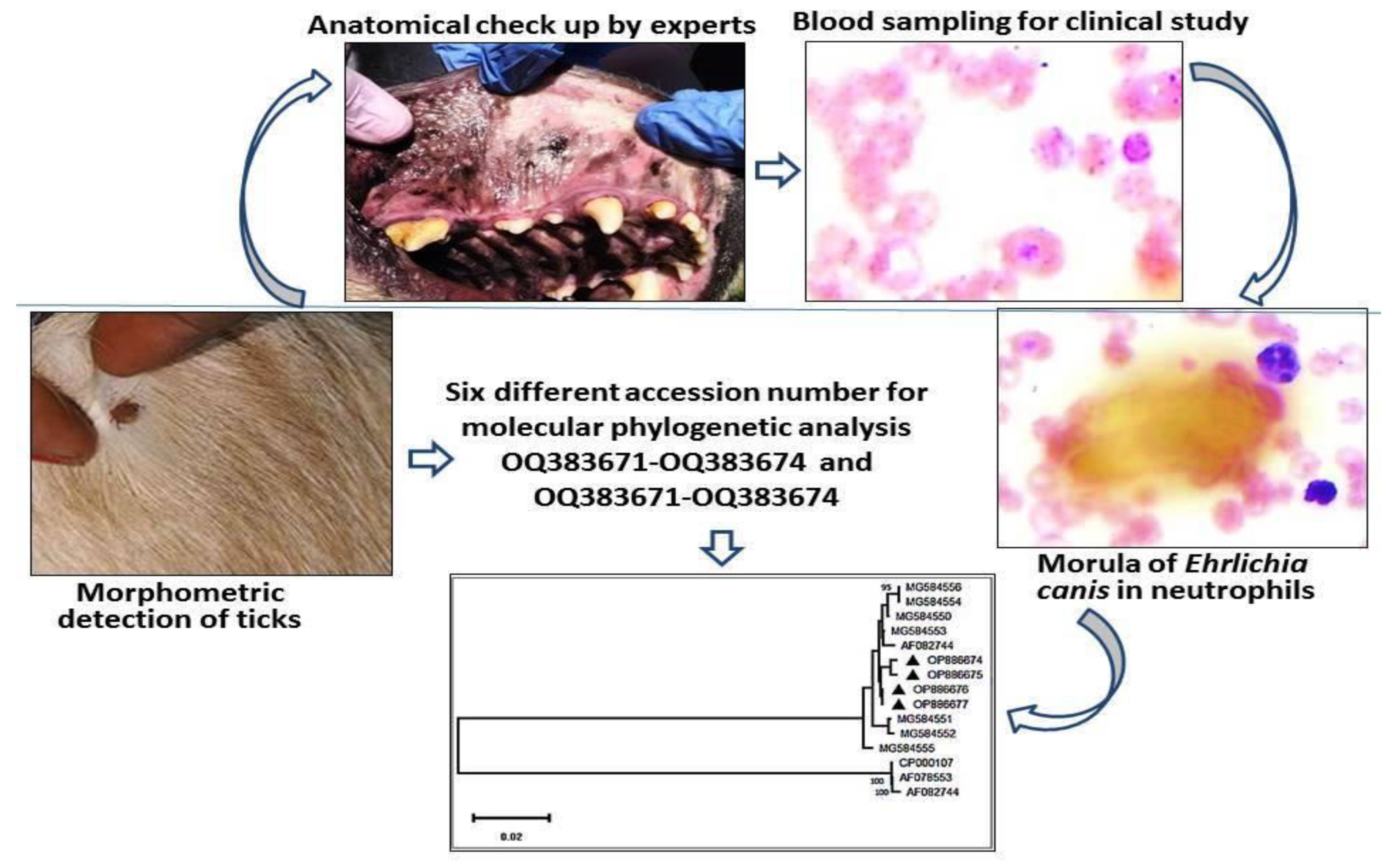

5. Conclusion

Tick-borne diseases in dogs impede the health of dogs and cause detrimental effects on their overall performance and immunity. Early detection of the disease with suitable veterinary care may limit unnecessary veterinary expenses along with increasing the survivability of the dogs. This molecular report recorded as the first-ever detailed investigative approach on this important emerging disease with relatively higher prevalence in Bhubaneswar of Eastern India needs the proper attention of all the stakeholders to mitigate further spread and enrich the scientific literature about the disease in this corner of the globe. Apart from the conventional screening through blood smear examination, a molecular approach like PCR should be advocated owing to its sensitivity and specificity (

Figure 9).

Supplementary Materials

Submitted along with the ms.

Author Contributions

BRP and PKR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. AC: Methodology, Data acquisition, Data curation, Statistics, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. SKP, BPM, MD, SB, MKJ, BPS and DKS- Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

No funding received to conduct the present work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As animal sacrifice has not been conducted, and the treating veterinarian has collected blood sample at the dawn and dusk, in a manner that minimizes pain and stress to the animal in the presence and verbal consent of the owner, solely for the purpose of investigation and diagnosis, there was no necessity for an ethical permission. Clinical samples were collected by the registered Veterinarians from the presented dogs in the Veterinary Clinical Complex of the college for investigation of the disease conditions for suggesting suitable therapeutic regimen. Accordingly, the samples were processed. Permission was not required to conduct research on the collected sample as they were used for diagnostic purpose. Due consent was obtained from the pet owners during sampling. Necessary permission about the above fact was obtained from Animal Ethical Committee of Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology to carry out the work.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the owners of the dogs to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All data associated in this article are included in article/supp. material/referenced in article. Any individual data shall be provided by the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

Help rendered by the Publication Cell, OUAT is acknowledged. Encouragement rendered by Prof. Pravat Kumar Raul, Honorable Vice Chancellor, OUAT is duly acknowledged. Help rendered by the publication guidance cell of Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology is acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no competitive interest.

References

- Angkanaporn, K.; Sanguanwai, J.; Baiyokvichit, T.O.; Vorrachotvarittorn, P.; Wongsompong, M.; Sukhumavasi, W. Retrospective analysis of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis in Thailand with emphasis on hematological and ultrasonographic changes. Veter- World 2022, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, S.S.; Aguiar, D.M.; Aquino, S.F.; Orlandelli, R.C.; Fernandes, A.R.F.; Uchôa, I.C.P. Soroprevalência e fatores de risco associados à soropositividade para Ehrlichia canis em cães do semiárido da Paraíba. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science 2011, 48, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Goel, P.; Jhambh, R.; Kumar, P.; Joshi, V.G. Molecular prevalence and haemato-biochemical profile of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis in dogs in and around Hisar, Haryana, India. J. Parasit. Dis. 2017, 41, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Hoque, M.; Sharma, K.; Saravanan, M.; Monsang, S.W.; Mohanta, R.K. Abdominal Ultrasonography of Dogs with Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis. Indian Veterinary Journal 2012, 89, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadesiya, C.M.; Raval, S.K. Hematobiochemical changes in ehrlichiosis in dogs of Anand region, Gujarat. Veter- World 2015, 8, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, R.K. Therapeutic management of acute canine monocytic ehrlichiosis. Indian Veterinary Journal 2013, 90, 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Buhles, W.C., Jr.; Huxsoll, D.L.; Ristic, M. Tropical canine pancytopenia: Clinical, hematologic, and serologic response of dogs to Ehrlichia canis infection, tetracycline therapy and challenge inoculation. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1974, 130, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.M., Jr.; Rembeck, K.; Ribeiro, M.F.B.; Beelitz, P.; Pfister, K.; Passos, L.M.F. Sero-prevalence and risk indicators for Canine Ehrlichiosis in three rural areas of Brazil. Veterinary Journal 2007, 174, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres, F. Biology and ecology of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Parasites Vectors 2010, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.L.M.; Munhoz, T.D.; João, C.F.; Vargas-Hernández, G.; André, M.R.; Pereira, W.A.B.; Machado, R.Z.; Tinucci-Costa, M. Ehrlichia canis (Jaboticabal strain) induces the expression of TNF-α in leukocytes and splenocytes of experimentally infected dogs. Rev. Bras. De Parasitol. Veter- 2011, 20, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, P.E.B.; Oliveira, T.N.d.A.; Carvalho, F.S.; Carlos, R.S.A.; Albuquerque, G.R.; Munhoz, A.D.; Wenceslau, A.A.; Silva, F.L. Canine ehrlichiosis: prevalence and epidemiology in northeast Brazil. Rev. Bras. De Parasitol. Veter- 2015, 24, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritha, G.S.; Nirosha, M.; Shaik, S.; Venkatesh, K.; Kumari, K.N. Clinical and hemato-biochemical studies on ehrlichiosis and babesiosis in canines. Intas Polivet 2018, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Himalini, S.R.; Bharadwaj, R.K.; Gupta, A.K. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Ehrlichia canis in dogs of Jammu region. Journal of Animal Research 2018, 8, 923–927. [Google Scholar]

- Kottadamane, M.R.; Dhaliwal, P.S.; Singla, L.D.; Bansal, B.K.; Uppal, S.K. Clinical and haematobiochemical response in canine monocytic ehrlichiosis seropositive dogs of Punjab. Veterinary World 2017, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, A.; Varshney, A.C.; Tyagi, S.P.; Kanwar, M.S.; Sharma, S.K. Diagnostic Imaging of Canine Hepatobiliary Affections: A Review. Veter- Med. Int. 2012, 2012, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labruna, M.B.; Pereira, M.D.C. Carrapato em cães no Brasil. Clínica Veterinária 2001, 6, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkawar, A.W.; Nair, M.G.; Varshney, K.C.; Sreekrishnan, R.; Rao, V.N. Pathology of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis in a German Shepherd dog. Slovenian Veterinary Research (Slovenia) 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lorsirigool A and Pumipuntu, N. A retrospective study of dogs infected with Ehrlichia canis from 2017-2019 in the Thonburi area of Bangkok province, Thailand. International Journal of Veterinary Science 2020, 9, 578–580. [Google Scholar]

- Milanjeet, M.; Singh, H.; Singh, N.; Singh, C.; Rath, S. Molecular prevalence and risk factors for the occurrence of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis. Veter- Med. 2014, 59, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, M.E.; Harrus, S.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. An update on the treatment of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis). Veter- J. 2019, 246, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, M.; Kritsepi-Konstantinou, M.; Dumler, J.; Diniz, P.P.; Day, M.; Siarkou, V.; Breitschwerdt, E.; Psychas, V.; Petanides, T.; Koutinas, A. Severe Hepatitis Associated with Acute Ehrlichia canis Infection in a Dog. J. Veter- Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaghi, A.C.H.; Machado, R.Z.; Costa, M.T.; André, M.R.; Baldani, C.D. Canine ehrlichiosis: clinical, hematological, serological and molecular aspects. Cienc. Rural. 2008, 38, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaghi, A.C.H.; Machado, R.Z.; Ferro, J.A.; Labruna, M.B.; Chryssafidis, A.L.; André, M.R.; Baldani, C.D. . Sensitivity evaluation of a single-step PCR assay using Ehrlichia canis p28 gene as a target and its application in diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2010, 19, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwetpathomwat, A.; Assarasakorn, S.; Techangamsuwan, S.; Suvarnavibhaja, S.; Kaewthamasorn, M. Canine dirofilariasis and concurrent tick-borne transmitted diseases in Bangkok, Thailand. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2006, 15, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, L.H. Diagno’stico de hemoparasitos e carrapatos de ca˜es procedentes de a’reas rurais procedentes de treˆs mesorregio˜es do estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro-UFRRJ, Serope’dica (RJ), Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Okubanjo, K.; Pyle, R.L.; Reddy, A.M. Rickettsia canis in Hyderabad. Indian Veterinary Journal 2014, 35, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, D.; Nishimori, C.T.; Costa, M.T.; Machado, R.Z.; Castro, M.B. Anti-Ehrlichia canis antibodies detection by “Dot-ELISA” in naturally infected dogs. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2000, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, C.; Pednekar, R.; Jayraw, A.; Gatne, M. Comparative diagnostic methods for canine ehrlichiosis. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences 2013, 37, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungsipipat, A.; Oda, M.; Kumpoosiri, N.; Wangnaitham, S.; Poosoonthontham, R.; Komkaew, W.; Suksawat, F.; Ryoji, Y. Clinicopathological study of experimentally induced canine monocytic ehrlichiosis. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.; Abdelhady, A.; Alahadeb, J. Prevalence and first molecular characterization of Ehrlichia canis in Egyptian dogs. Pakistan Veterinary Journal 2020, 41, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siarkou, V.I.; Mylonakis, M.E.; Bourtzi-Hatzopoulou, E.; Koutinas, A.F. Sequence and phylogenetic anal¬ysis of the 16S rRNA gene of Ehrlichia canis strains in dogs with clinical monocytic ehrlichiosis. Veterinary Microbiology 2007, 125, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.S.; Pinho, F.A.; Prianti, M.G.; Braga, J.F.; Pires, L.; França, S.A.; Silva, S.M. Renal histopathological changes in dogs naturally infected with Ehrlichia canis. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Pathology 2016, 9, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thongsahuan, S.; Chethanond, U.; Wasiksiri, S.; Saechan, V.; Thongtako, W.; Musikacharoen, T. Hematological profile of blood parasitic infected dogs in Southern Thailand. Veter- World 2020, 13, 2388–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuna, G.E.; Bakirci, S.; Dinler, C.; Karagenc, T.; Ulutas, B. Monocytic ehrlichiosis in Aegean region dogs: Clinical and haematological findings. Ataturk Universitesi Veteriner Bilimleri Dergisi 2019, 14, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waner, T.; Harrus, S. Canine monocytic ehrlichi¬osis-from pathology to clinical manifestations. Israel Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2013, 68, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Occurrence of Ehrlichia canis in blood cells of buffy coat smear dogs in eastern India. A) Presence of morula of Ehrlichia canis in neutrophils in blood smear, B) Presence of morula of Ehrlichia canis in monocytes in buffy coat smear.

Figure 1.

Occurrence of Ehrlichia canis in blood cells of buffy coat smear dogs in eastern India. A) Presence of morula of Ehrlichia canis in neutrophils in blood smear, B) Presence of morula of Ehrlichia canis in monocytes in buffy coat smear.

Figure 2.

Clinical symptoms of Ehrlichiosis in eastern Indian dogs. A) Epistaxis / Nasal bleeding in affected dogs, B) Corneal opacity in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, C) Oedema in affected dogs, D) Presence of ticks on hair coat of affected dogs.

Figure 2.

Clinical symptoms of Ehrlichiosis in eastern Indian dogs. A) Epistaxis / Nasal bleeding in affected dogs, B) Corneal opacity in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, C) Oedema in affected dogs, D) Presence of ticks on hair coat of affected dogs.

Figure 3.

Pathophysiological manifestation in dogs under Ehrlichiosis in eastern India. A) Congested oral mucosae in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, B) Hind limb oedema in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, C) Enlarged and icteric liver in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, D) Haemorrhagic urinary bladder mucosae in Ehrlichiosis affected dogs.

Figure 3.

Pathophysiological manifestation in dogs under Ehrlichiosis in eastern India. A) Congested oral mucosae in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, B) Hind limb oedema in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, C) Enlarged and icteric liver in Ehrlichiosis-affected dogs, D) Haemorrhagic urinary bladder mucosae in Ehrlichiosis affected dogs.

Figure 4.

Histological studies in dogs under Ehrlichiosis. A) Photomicrograph showing vacuolar degenerations, fatty changes, necrosis of hepatocytes around the central vein, B) Photomicrograph showing necrosis of renal tubular epithelial cells with desquamation and presence of proteinaceous materials in renal tubules (H&E-40X), C) Photomicrograph showing alveolar degeneration, necrosis along with interstitial congestion and oedema of interstitial spaces (H&E-40X), D) Photomicrograph showing diffuse haemosiderosis in the spleen (H&E-10X).

Figure 4.

Histological studies in dogs under Ehrlichiosis. A) Photomicrograph showing vacuolar degenerations, fatty changes, necrosis of hepatocytes around the central vein, B) Photomicrograph showing necrosis of renal tubular epithelial cells with desquamation and presence of proteinaceous materials in renal tubules (H&E-40X), C) Photomicrograph showing alveolar degeneration, necrosis along with interstitial congestion and oedema of interstitial spaces (H&E-40X), D) Photomicrograph showing diffuse haemosiderosis in the spleen (H&E-10X).

Figure 5.

Rhipicephalus sanguineus in dog population under Ehrlichiosis. A) Hexagonal basis capitulum and Festoons of R. sanguineus, B) Anal plates, anal group and anus of R. sanguineus.

Figure 5.

Rhipicephalus sanguineus in dog population under Ehrlichiosis. A) Hexagonal basis capitulum and Festoons of R. sanguineus, B) Anal plates, anal group and anus of R. sanguineus.

Figure 6.

PCR product showing the bands through agarose gel electrophoresis at 843bp.

Figure 6.

PCR product showing the bands through agarose gel electrophoresis at 843bp.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree showing accession numbers of Ehrlichia canis of Bhubaneswar, Odisha.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree showing accession numbers of Ehrlichia canis of Bhubaneswar, Odisha.

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of various diagnostic methods.

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of various diagnostic methods.

Figure 9.

Concluding remark with a roundtrip suggestion to the pet owners to go with the pathogenesis of the ticks present in dogs if they any systems.

Figure 9.

Concluding remark with a roundtrip suggestion to the pet owners to go with the pathogenesis of the ticks present in dogs if they any systems.

Table 1.

Temperature time Protocol in Proflex PCR system (Invitrogen, USA).

Table 1.

Temperature time Protocol in Proflex PCR system (Invitrogen, USA).

| Events |

Temperature |

Time |

Cycles |

| Initial Denaturation |

95°C |

5 minutes |

1 cycle |

| Denaturation, Annealing and extension |

95°C |

30 seconds |

35 cycles |

| 55°C |

1 minute |

| 72°C |

2 minutes |

| Extension |

72°C |

5 minutes |

cycle |

Table 2.

Detailed epidemiological risk factors in canine ehrlichiosis.

Table 2.

Detailed epidemiological risk factors in canine ehrlichiosis.

| Variable |

N |

Positive |

Prevalence (%) |

OR |

95% CI |

Chi square |

P Value |

| Gender |

Male |

115 |

38 |

33.04 |

* |

- |

>0.9 |

|

| Female |

57 |

18 |

31.57 |

1.06 |

0.50-2.24 |

0.9 |

| Age (years) |

<1 |

51 |

23 |

45.09 |

* |

- |

0.045 |

|

| 1 to 2 |

36 |

12 |

33.33 |

0.37 |

0.14-0.89 |

0.030 |

| >2 |

79 |

21 |

26.58 |

0.39 |

0.17-0.87 |

0.022 |

| Ticks |

Absent |

38 |

12 |

31.57 |

* |

- |

>0.9 |

|

| Present |

140 |

44 |

31.42 |

0.88 |

0.38-2.06 |

0.8 |

| Housing |

Kaccha House with Field |

51 |

16 |

31.37 |

* |

- |

>0.9 |

|

| Pukka house with close confinement |

22 |

7 |

31.81 |

0.89 |

0.27-2.83 |

0.9 |

| Pukka house with access to open field |

105 |

33 |

31.42 |

1 |

0.47-2.19 |

>0.9 |

| Body weight (kg) |

<10 |

16 |

5 |

31.25 |

* |

- |

>0.9 |

|

| 10 to 20 |

29 |

9 |

31.03 |

1.08 |

0.28-4.51 |

>0.9 |

| >20 |

133 |

42 |

31.57 |

0.88 |

0.28-3.11 |

0.8 |

| Season |

Rainy |

54 |

17 |

31.48 |

* |

- |

>0.9 |

|

| Summer |

98 |

31 |

31.63 |

1.16 |

0.54-2.54 |

0.7 |

| Winter |

26 |

8 |

30.76 |

1.03 |

0.34-2.98 |

>0.9 |

| Breed |

G.S |

44 |

14 |

31.81 |

* |

- |

>0.9 |

|

| Labrador |

39 |

12 |

30.76 |

1 |

0.38-2.67 |

>0.9 |

| Golden Retriever |

28 |

9 |

32.14 |

0.97 |

0.33-2.78 |

>0.9 |

| Alsatian |

25 |

8 |

32 |

0.93 |

0.30-2.79 |

>0.9 |

| Doberman |

19 |

6 |

31.57 |

1.11 |

0.31-3.74 |

0.9 |

| Spitz |

13 |

4 |

30.76 |

0.8 |

0.18-3.13 |

0.8 |

| Beagle |

10 |

3 |

30 |

0.99 |

0.18-4.42 |

>0.9 |

Table 3.

Haematological alterations in dogs affected with Ehrlichiosis.

Table 3.

Haematological alterations in dogs affected with Ehrlichiosis.

| Parameters |

Ehrlichiosis Negative (N=122) |

Ehrlichiosis Positive (N=56) |

| Hb (g/dl) |

14.07±0.30a

|

6.33±0.22b

|

| TEC (×106 µl) |

7.43±1.04a

|

3.47±0.19b

|

| PCV (%) |

44.10±0.88a

|

19.33±0.74b

|

| TLC (×103 µl) |

10.87±0.63a

|

9.40±0.13b

|

| PLT |

532.20±38.68a

|

74.40±4.31b

|

| MCV (fl) |

59.81±1.24a

|

64.14±0.38b

|

| MCH (Pg) |

22.17±0.13a

|

23.07±0.08b

|

| MCHC (%) |

33.46±0.38a

|

38.23±0.21b

|

| N (%) |

57.20±0.38a

|

78.37±0.83b

|

| L (%) |

36.70±0.35a

|

16.50±0.79b

|

| E (%) |

4.47±0.26a

|

1.53±0.93b

|

| M (%) |

1.63±0.89a

|

3.60±0.13b

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).