1. Introduction

The increasing number of domestic and stray dogs in large cities has become an increasingly pressing issue. This phenomenon is linked to rising population density, characteristics of urban environments, and insufficient control over animal reproduction. In addition to social and ecological aspects, this trend has significant epidemiological implications, as dogs can act as carriers of various infectious and parasitic diseases.

Cities with high population density create favorable conditions for the transmission of zoonotic infections between dogs and humans. Unauthorized dumps, lack of veterinary control, and overcrowding of animals contribute to the spread of viruses, bacteria, and parasites.

Dogs, especially stray ones, become reservoirs for pathogens that can be transmitted to humans through bites, contact with fur, or contaminated excretions. Deteriorating sanitary conditions and lack of vaccination increase the risks of outbreaks.

Studying the role of dogs in the spread of infections is crucial for developing effective preventive measures. Dog population control and mandatory vaccination can help reduce the risks of diseases among both humans and animals. The rising number of dogs in large cities requires a comprehensive approach, including sanitary control measures, epidemiological monitoring, and animal population regulation. Only through the combination of these strategies can we minimize the threat of zoonotic infections and create a safe environment for both people and animals. A study of dogs and cats in Italy found infections in domestic animals with zoonotic parasites, including T. canis, T. cati, T. vulpis, Ancylostomatidae, and G. duodenalis assemblage [

1].

In West Africa, specifically in Nigeria, stray dogs were found to be infected with Ancylostoma caninum, with an infection rate of 62.5%, Toxocara canis at 20.8%, Dipylidium caninum at 18.7%, and Strongyloides stercoralis at 2.0% [

2]. A study conducted in the capital of Argentina, covering 219 dogs from socioeconomically disadvantaged areas of Buenos Aires with a high level of unmet basic needs, revealed the presence of antibodies to Brucella canis in 7.3% of the animals. Additionally, in three cases, B. canis was found to be excreted in bacterial form. These findings highlight a potential epidemiological threat to the population at risk of infection [

3].

In Canada, cases of human infection with Echinococcus multilocularis have been reported, with transmission occurring via infected dogs. A study was conducted to assess the prevalence of this infestation and related risk factors among domestic dogs in Calgary, Alberta. The study, which involved collecting and analyzing fecal samples from dogs while considering potential risk factors, found that 13 out of 696 samples collected in August and September 2012 tested positive for E. multilocularis by PCR analysis, with an infestation rate ranging from 2.4% to 95% [

4].

In the north of Russia, in the city of Novosibirsk, an assessment of the prevalence of Opisthorchis felineus infestation was carried out among 103 cats and 101 dogs taken from shelters in various city districts as well as rural settlements along the Ob River. It was found that the infestation rate of Opisthorchis in cats ranged from 12.6% to 95%, significantly higher than that in dogs, where the infestation rate ranged from 4.0% to 95% [

5].

In Western Kazakhstan, foci of opisthorchiasis are most prevalent among the population and carnivorous animals in river basins that provide favorable conditions for mollusks and carp species. It has been established that in the coastal villages along the Ural River, the prevalence of O. felineus infestation in dogs was on average 89.7%, with an intensity of 19.6 individuals per dog. In cats, the prevalence was on average 97.9%, with an intensity of 34.4 individuals per cat [

6].

The highest prevalence of echinococcosis has been recorded in the southern regions of Kazakhstan. An analysis of zoonotic helminthiasis cases from January to May 2015 found that echinococcosis was diagnosed in 65 individuals across the country. Among these, 42 cases (64.6%) were registered among rural residents, who have more direct contact with the primary carriers of the infection—dogs. In the structure of the affected population, 14 children (21.5%) under the age of 14 and 5 adolescents (7.7%) aged 15-17 were identified [

7].

The epizootiological situation in the Western Kazakhstan region regarding parasitic and infectious diseases in dogs within the urban environment remains tense. According to various studies, several species of helminths from the classes Trematoda, Cestoda, and Nematoda have been identified in dogs, which continues to be a significant concern [

8,

9,

10].

The widespread occurrence of parasitic and infectious diseases among dogs is driven by the growing population of stray animals. These animals act as reservoirs for pathogens of infectious and parasitic diseases, and their uncontrolled movement throughout the city contributes to the further spread of these pathogens. An additional factor exacerbating the epizootiological situation is the insufficient level of veterinary control, as well as the poor conditions for the care of domestic (yard) dogs and the complete absence of such conditions in stray animals.

The aim of this study is to investigate the role of stray dogs in the transmission of infectious and parasitic diseases that pose a threat to both human and animal health in the city of Uralsk.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in 2024 at the veterinary clinic and laboratory of the Testing Center at Zhangir Khan West Kazakhstan Agrarian Technical University (Zhangir Khan University), located in the city of Uralsk, Kazakhstan.

All procedures were carried out in compliance with the requirements of the following regulatory documents: the "European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes" (Strasbourg, 1986); the Commission Recommendation 2007/526/EC of June 18, 2007, on the housing and care of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes; the "Guidelines for the Ethical Review of Biomedical Research" (WHO, Geneva, 2000), which regulate the care and use of laboratory animals [

11].

The scientific research aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 3, "Good Health and Well-being," as the spread of infectious and parasitic diseases among dogs in urban environments has epidemiological significance and may pose a risk to public health. The results of this study may contribute to the development of preventive and control measures aimed at reducing the threat of zoonotic infections [

12].

2.1. Clinical Research

Stray dogs were captured from various districts of the city of Uralsk. The captured animals were registered in the unified database for dogs and cats of the West Kazakhstan region and the Uralsk metropolis on the portal "rfid07.kz," after which they were chipped and underwent medical screening.

Clinical examination was performed in accordance with established veterinary standards. The general health status of the dogs was assessed, visible mucous membranes (oral, nasal, conjunctiva, and in females, the vagina) were inspected, body temperature was measured, and pulse and respiratory rates were determined. All parameters were recorded in an electronic database. Over the course of the year, 1,213 stray dogs from different districts of the Uralsk metropolis were captured. Biological samples (blood, urine, and feces) were collected from the captured animals to detect infectious and parasitic disease pathogens using molecular-genetic and helminthological methods (

Table 1).

2.2. Detection of Infectious Agents P. multocida, Leptospira spp., C. trachomatis, and Brucella spp. in Canine Blood and Urine Samples Using PCR

Materials and Reagents: PCR detection was performed using the ScreenMix kit (Evrogen), nuclease-free water, ethidium bromide (EtBr), 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer, agarose, and biological samples collected from dogs, including blood, serum, feces, and urine.

2.2.1. DNA extraction for parasitic pathogens was carried out using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen).

2.2.2. PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Gene for Bacterial Pathogen Detection:

Amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was performed using oligonucleotide primers: forward primer 16S rRNA-F and reverse primer 16S rRNA-R. The resulting amplicon was 1500 base pairs in length. The PCR reaction was set up in a 25 μL volume, consisting of 2.5 μL of 5× ScreenMix (Evrogen), 0.5 μL each of forward and reverse primers, 3 μL of DNA template, and 6 μL of nuclease-free water. The PCR thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 minutes; 30 cycles of denaturation at 96 °C for 15 seconds, annealing at 58 °C for 20 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 90 seconds; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 1 minute. Amplified products were stored at 4 °C indefinitely after the reaction.

2.2.3. Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) for the Detection of Pasteurella multocida

To amplify the DNA of Pasteurella multocida, the following primers were used: forward primer 5′-ATC CGC TAT TTA CCC AGT GG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCT GTA AAC GAA CTC GCAC-3′, yielding a 456 bp PCR product. The 25 µL reaction mixture included: 2.5 µL of 10× buffer, 1 µL each of forward and reverse KMT primers, 0.2 µL of Assu Prime Taq polymerase, 3 µL of DNA template, and 17.3 µL of nuclease-free water. The amplification protocol was as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55 °C for 30 seconds, and extension at 68 °C for 1 minute. A final extension was performed at 68 °C for 10 minutes.

2.2.4. PCR Detection of Leptospira spp.

The detection of Leptospira spp. was carried out using the following primers: forward primer G1 (5′-CTG AAT CGC TGT ATA AAA GT-3′) and reverse primer G2 (5′-GGA AAA CAA ATG GTC GGA AG-3′), yielding a 285 bp product. The reaction was performed using the ScreenMix PCR kit (Evrogen). The reaction mixture consisted of 5 µL of 5× ScreenMix, 1 µL each of 10 mM forward and reverse primers, 5 µL of genomic DNA (5–50 ng/µL), and nuclease-free water up to a total volume of 25 µL. PCR amplification was conducted on an Applied Biosystems thermal cycler (USA) using the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 48 °C for 45 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 30 seconds; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 minutes.

2.2.5. PCR Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis

For the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, the primers NRO (5′-CTC AAC TGT AAC TGC GTA TTT-3′) and NLO (5′-ATG AAA AAA CTC TTG AAA TCG-3′) were used, amplifying a 1087 bp product. The ScreenMix kit (Evrogen) was used for PCR setup. The reaction mixture included 5 µL of 5× ScreenMix, 1 µL each of 10 mM forward and reverse primers, 5 µL of genomic DNA (5–50 ng/µL), and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 µL. Amplification was conducted using an Applied Biosystems thermal cycler with the following protocol: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 minutes; 49 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 minute, annealing at 55 °C for 1 m.

2.2.6. PCR Detection of Brucella spp.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was employed to detect Brucella spp. DNA amplification was carried out using a forward primer (ATC CGC TAT TTA CCC AGT GG) and a reverse primer (GCT GTA AAC GAA CTC GC AC), producing an amplicon of 527 base pairs. The reaction mixture consisted of 2.5 µL of 10× PCR buffer, 1 µL of the forward primer KMTa, 1 µL of the reverse primer KMT1s, 0.2 µL of Assu Prime Taq polymerase, 3 µL of template DNA, and 17.3 µL of nuclease-free water, resulting in a final volume of 25 µL. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 68°C for 1 minute. A final extension step was performed at 68°C for 10 minutes.

2.3. Detection of Infectious Disease Pathogens (P. multocida, Leptospira spp., C. trachomatis, Brucella spp., L. monocytogenes, Mycobacterium spp.) in Canine Serum Samples Using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.3.1. ELISA-Based Protocol for the Detection of Antibodies Against Infectious Agents

To detect antibodies against bacterial pathogens in canine serum samples, a commercial diagnostic ELISA kit titled “Diagnostic kit for the detection of individual specific IgG antibodies to bacteria in the serum (plasma) of carnivores (dogs, cats) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)” was used. The analysis was performed on serum samples collected from stray dogs. The procedure strictly followed the manufacturer's instructions and was carried out as follows:

Initially, all required reagents and consumables were prepared, including the diagnostic kit and a microplate pre-coated with bacterial antigens. Blood samples were collected, and serum was obtained via centrifugation to remove cellular components. A volume of 100 µL of each serum sample was added to the wells of the microplate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes to allow antigen–antibody binding.

Following incubation, the wells were washed multiple times to remove unbound substances. Then, enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-IgG) were added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for another 30 minutes. After this second incubation, the wells were washed again, and a chromogenic substrate (TMB) was added. In the presence of antigen–antibody complexes, the substrate underwent a colorimetric change. The substrate incubation was carried out at room temperature for 15–30 minutes. To terminate the reaction, a stop solution was added, resulting in a color change that could be quantitatively measured.

The optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Positive samples exhibited a distinct color change, while negative samples did not. Internal controls were included in each run to ensure assay validity and result reliability. Throughout the procedure, the ELISA protocol provided by the manufacturer was meticulously followed to prevent errors and ensure accurate, reproducible results [

13].

2.4. Detection of Parasitic Pathogens Toxocara canis and Echinococcus granulosus in Canine Fecal Samples by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

2.4.1. PCR Amplification for Toxocara canis Detection

To detect Toxocara canis, species-specific primers were used: forward primer Tcan1 (5′-AGTATGATGGGCGCGCCAAT-3′) and reverse primer NC2 (5′-TAGTTTCTTTTCCTCCGCT-3′). The expected PCR product size was 380 bp. The amplification was carried out using the ScreenMix kit (Evrogen, Russia). The reaction mixture contained 5 µL of 5X ScreenMix, 1 µL each of the forward and reverse primers (10 µM), 5 µL of genomic DNA (5–50 ng/µL), and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 µL. PCR amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 seconds, annealing at 58 °C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 °C for 30 seconds; with a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 minutes.

2.4.2. PCR Amplification for Echinococcus granulosus Detection

For the detection of Echinococcus granulosus, the following primers were used: forward primer Eg1121a (5′-GAATGCAAGCAGCAGATG-3′) and reverse primer Eg1122a (5′-GAGATGAGTGAGAAGGAGTG-3′), producing an amplicon of 133 bp. Amplification was carried out using the ScreenMix kit (Evrogen, Russia). The reaction mixture included 5 µL of 5X ScreenMix, 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 5 µL of genomic DNA (5–50 ng/µL), and nuclease-free water to a total volume of 25 µL. The PCR was conducted in a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) using the following cycling parameters: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55 °C for 1 minute, and extension at 72 °C for 1 minute; with a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 minutes.

2.4.3. Electrophoretic Analysis of PCR Products

For electrophoretic analysis, 5 µL of each PCR product was mixed with a DNA marker and subjected to electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel containing 0.5 µg/mL ethidium bromide (EtBr) in 1× Tris–acetate–EDTA (TAE) buffer at 120 V for 20 minutes. The amplified products were visualized and documented using a gel documentation system [

14].

2.5. Detection of E. granulosus and T. canis Antibodies in Canine Serum by ELISA

Serological detection of E. granulosus and T. canis infections in canine serum samples was also conducted using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), following the procedure described previously and in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

2.6. Detection of Parasitic Pathogens in Dog Feces by Fulleborn’s Flotation Method Using a Helminth Egg Counting Chamber

To detect helminth eggs, fecal samples (3 g) were placed into a mortar, mixed with 5 mL of a flotation solution composed of table salt (specific gravity 1.25) and ammonium nitrate (specific gravity 1.38), and homogenized with a pestle. While stirring, additional flotation solution was added to obtain a uniform suspension. The mixture was filtered through a metal sieve into a 30 mL plastic container and allowed to settle for 5–10 minutes. Using a sterile metal loop, 3–5 drops of the supernatant (one from the center and the rest from the periphery) were placed into a well of the lower plate of a helminth egg counting chamber, which was then covered with the upper plate. The flotation solution was carefully added with a pipette to avoid overflow. After one minute, helminth eggs floated and adhered to the lower surface of the upper plate. The chamber was then placed under a microscope, and all eggs in the well were counted.

The total number of eggs was divided by the number of drops in the chamber, and the resulting value was multiplied by a correction factor of 38 (reflecting the number of loopfuls covering the surface area of the suspension in the container). The final result corresponded to the number of eggs per 3 grams of feces. The loop, mortar, pestle, and sieve were thoroughly washed between samples to avoid cross-contamination [

15,

16].

2.6.1. Collection of Biological Samples from Dogs

Blood Sampling: Prior to blood collection, dogs were physically restrained to minimize stress and prevent injury to both animals and personnel. Venipuncture was performed under sterile conditions from the subcutaneous metacarpal vein. Whole blood was collected in 5 mL sterile plastic vacuum tubes (vacutainers) containing K₂-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) as an anticoagulant, identified by purple caps. Tubes were gently inverted 5–8 times immediately after collection to prevent clotting. Samples were stored at +2 to +8°C to prevent hemolysis and preserve the cellular components.

2.6.2. Serum Collection.

For serum preparation, blood was collected in anticoagulant-free VACUETTE tubes using the same venipuncture method. Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting serum was transferred into sterile tubes using an automatic pipette and stored at –20°C until analysis [

17].

2.6.3. Urine Collection.

Urine was obtained by urethral catheterization. Samples were transferred to sterile containers and stored at +4°C until analysis.

For males, after restraining the dog in a standing position, the preputial area was cleaned with an antiseptic. A sterile-lubricated catheter was carefully inserted into the urethra and advanced toward the bladder. The presence of urine in the catheter confirmed correct placement.

For females, dogs were restrained in a lateral position. External genitalia were disinfected with an antiseptic. The urethral opening was located on the ventral wall of the vagina, approximately 1–2 cm from the vaginal orifice, often using a vaginal speculum for visualization. The catheter was inserted gently into the urethra until urine flow was observed, confirming access to the bladder [

18].

2.6.4. Fecal Sampling.

Fresh fecal samples were obtained by rectal swabbing using sterile cotton-tipped applicators, inserted 2–3 cm into the rectum, then carefully withdrawn and transferred to sterile containers for storage and analysis. Samples were stored at –20°C until examination.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Epidemiological Data and Helminth Infections in Stray Dogs in Uralsk, Kazakhstan (2020–2024).

An analysis of the data provided by the Veterinary Department of the West Kazakhstan Region and the Uralsk City Territorial Inspection for Veterinary Control and Supervision for the period from 2020 to 2024 revealed that a total of 7368 dogs were microchipped, underwent health screening, and were registered in the electronic information database within the city of Uralsk. During the same period, a consistent upward trend in the number of stray dogs was observed. Specifically, 1214 stray dogs were registered in 2020, 1033 in 2021, 1765 in 2022, 1645 in 2023, and 1711 in 2024.

Throughout the study period, two cases of rabies were confirmed among stray dogs, in addition to helminth infestations. A total of eight helminth species were identified, belonging to three taxonomic classes: Trematoda, Cestoda, and Nematoda.

The following helminths were detected:

Trematoda: Opisthorchis felineus — with a mean prevalence (extensity of invasion, EI) of 29.9%.

Cestoda: Echinococcus granulosus — mean EI of 15.0%; Dipylidium caninum — mean EI of 54.9%.

Nematoda: Toxascaris leonina — mean EI of 69.9%; Toxocara canis — mean EI of 72.0%; Ancylostoma caninum — mean EI of 75.0%; Uncinaria stenocephala — EI of 100.0%; Dirofilaria repens — mean EI of 29.4%.

According to the Uralsk City Department of Sanitary and Epidemiological Control, several cases of zoonotic infections among the human population were recorded between 2020 and 2024, including brucellosis (average of 2.2 cases/year), echinococcosis (13.2 cases/year), microsporia (9.4 cases/year), and trichophytosis (0.4 cases/year).

This analysis suggests that the rising population and infection rates of stray dogs in Uralsk significantly influence the city’s epidemiological situation, posing additional risks to public health. These findings indicate the presence of zoonotic diseases among both animals and humans.

In response, we initiated an independent investigation in 2024 to assess and verify the prevalence of infectious and parasitic diseases among stray dogs within the city. As part of this study, biological samples—including blood, serum, urine, and feces—were collected from stray dogs captured in various districts of Uralsk, following clinical examination, for subsequent laboratory analysis.

3.2. Investigation of Infectious Disease Prevalence in Stray Dogs

3.2.1. PCR-Based Detection of Infectious Agents in Canine Blood Samples

PCR analysis of blood samples collected from stray dogs revealed amplification products of approximately 1500 base pairs, indicating the presence of bacterial pathogen DNA in the tested samples.

To further identify the specific microorganisms present, PCR assays using species-specific primers were performed to detect DNA of the causative agents of

leptospirosis (Leptospira spp.),

pasteurellosis (Pasteurella multocida),

brucellosis (Brucella spp.), and

chlamydiosis (Chlamydia spp.). The results showed no amplification

of Leptospira, Pasteurella, or Chlamydia DNA in any of the blood samples. However, Brucella spp. DNA was detected in five samples, indicating the presence of the brucellosis pathogen (

Table 2).

For further identification of Brucella spp., AMOS-PCR was performed, enabling the differentiation of Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, Brucella suis, and Brucella canis. Based on the amplification results, no DNA of B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. ovis, or B. suis was detected in canine blood samples. However, B. canis DNA was identified in five samples.

3.2.2. PCR-Based Detection of Infectious Diseases in Canine Urine Samples

To confirm the results obtained from blood testing for infectious diseases in dogs, urine samples were analyzed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with pathogen-specific primers targeting bacterial DNA. The presence of bacterial DNA in the analyzed samples indicated ongoing infectious processes.

To identify the detected microorganisms, PCR was further performed on the positive samples using primers specific for Leptospira spp. (leptospirosis), Pasteurella multocida (pasteurellosis), Brucella spp. (brucellosis), and Chlamydia spp. (chlamydiosis). Amplification results revealed no detectable DNA of Leptospira spp., P. multocida, or Chlamydia spp. in the canine urine samples. However, DNA of Brucella spp., the causative agent of brucellosis, was detected in five samples.

To further characterize the

Brucella isolates, AMOS-PCR was employed, which allows for the differentiation of

Brucella abortus,

Brucella melitensis,

Brucella ovis,

Brucella suis, and

Brucella canis. Based on the amplification results, no DNA of

B. abortus,

B. melitensis,

B. ovis, or

B. suis was detected. Conversely,

B. canis DNA was identified in all five samples (

Table 3).

Thus, no amplification of DNA from the pathogens responsible for leptospirosis, pasteurellosis, and chlamydiosis was detected in the blood and urine samples of dogs using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). However, the presence of Brucella canis DNA was identified in five blood and urine samples during further identification. The PCR analysis results from various biological materials confirmed the reproducibility and reliability of the detected data. Brucella canis DNA was found in both blood and urine samples.

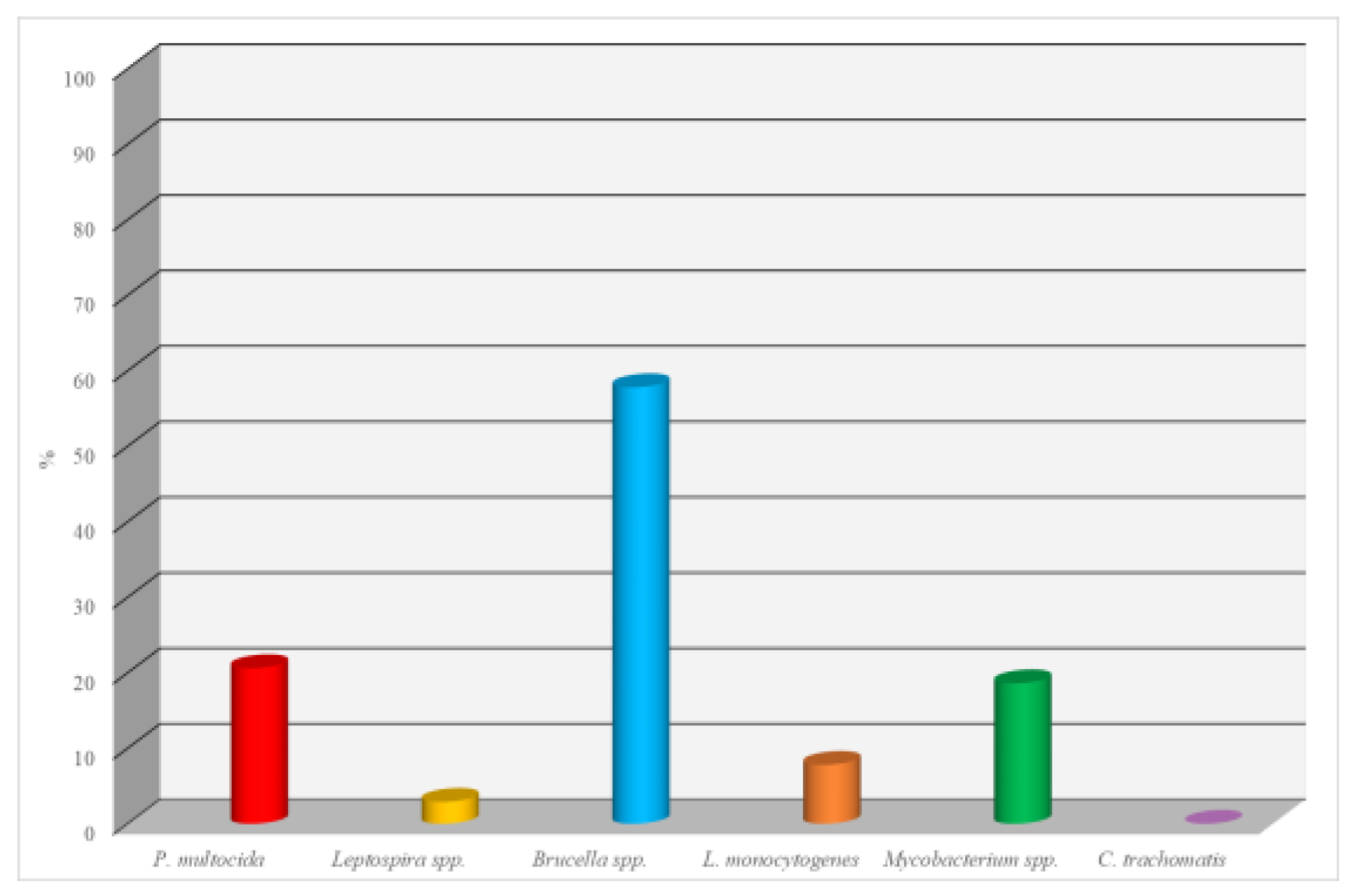

3.2.3. Results of Serum Samples from Dogs for the Detection of Infectious Diseases by ELISA

A total of 102 dog serum samples were examined for the presence of antibodies against various infectious agents using the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). The results for each pathogen are as follows:

Pasteurella multocida: Of the 102 samples tested, 21 (20.6%) showed a positive reaction. This indicates a relatively high level of infection with this microorganism, which can cause respiratory diseases, as well as skin and soft tissue lesions.

Leptospira spp.: A positive result was obtained in only 3 cases, corresponding to 2.9%. This low percentage may indicate limited spread of leptospirosis within the studied population.

Brucella spp.: The highest number of positive results was observed for Brucella spp., with 59 out of 102 samples testing positive (57.8%). This suggests a potentially high epidemiological significance of brucellosis in the dog population, especially considering the zoonotic nature of the disease.

Listeria monocytogenes: Eight samples tested positive, accounting for 7.8%. This level of infection may be attributed to the presence of the bacteria in the environment or food, posing a potential risk to both animals and humans.

Mycobacterium spp.: Nineteen positive reactions were observed, representing 18.6% of the samples. This result suggests the presence of mycobacterial infections in the dog population, potentially associated with atypical mycobacteria or tuberculosis pathogens.

Chlamydia trachomatis: No positive results were detected, indicating a 0% prevalence. This may suggest either the absence of circulation of this pathogen among the examined animals or its minimal epidemiological role within the studied population (see

Figure 1).

Thus, PCR analysis of blood and urine samples from dogs did not detect DNA of the pathogens responsible for leptospirosis, pasteurellosis, and chlamydiosis. At the same time, the presence of Brucella canis DNA was identified.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing of dog serum revealed the presence of antibodies to six infectious agents. The highest number of positive results was observed for Brucella spp. A moderate level of seropositivity was recorded for Pasteurella multocida and Mycobacterium spp. Lower positive results were noted in the tests for Listeria monocytogenes and Leptospira spp. No antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis were detected, indicating the absence of this pathogen in the examined sample.

The obtained data indicate the presence of Brucella spp. pathogens in the dogs, as well as evidence of past infections with Pasteurella multocida, Mycobacterium spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Leptospira spp., as confirmed by the detected antibodies.

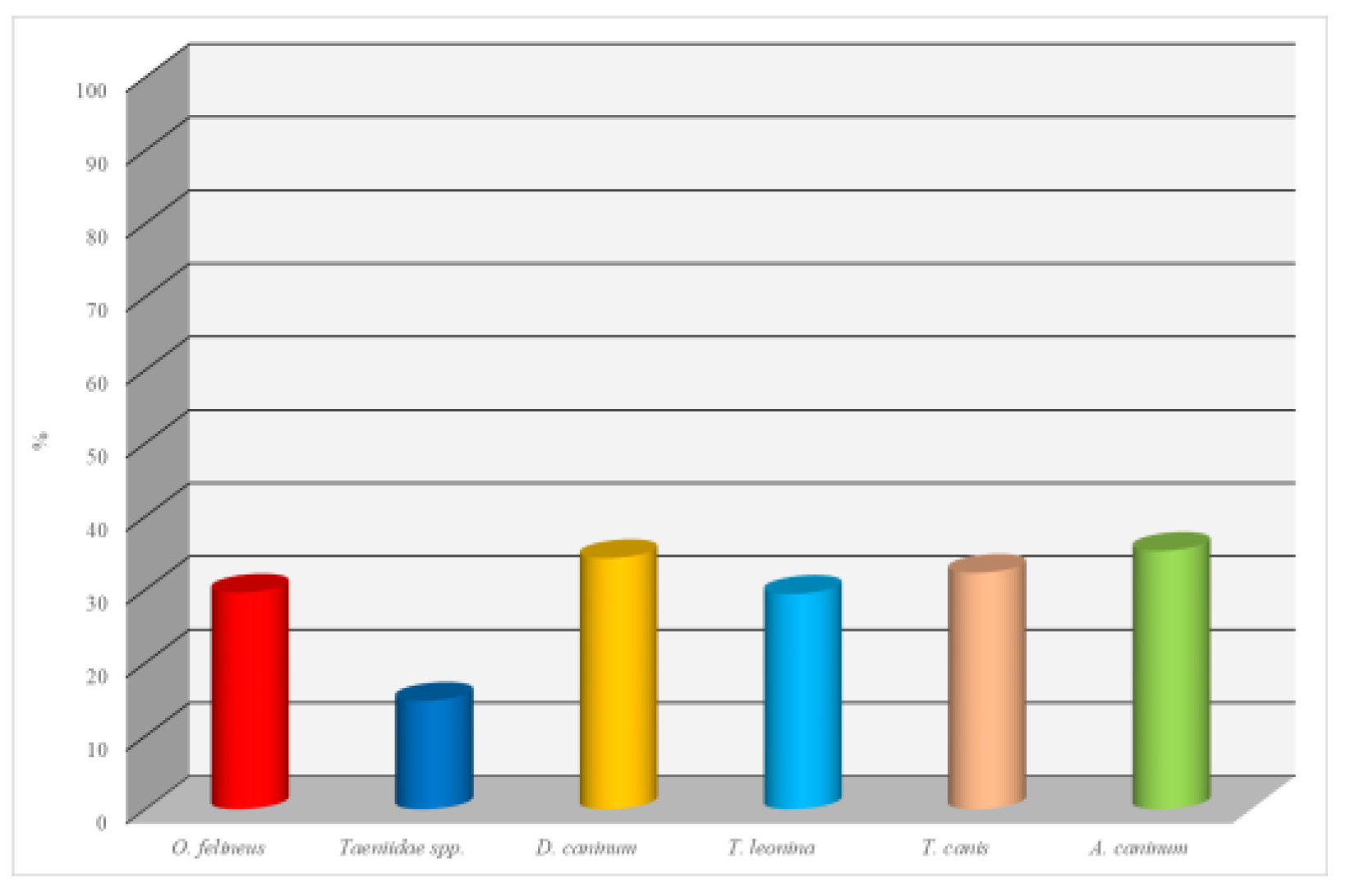

3.2.4. Results of Parasitological Examination of Fecal Samples from Stray Dogs Using the Fülleborn Flotation Method.

A total of 102 fecal samples collected from stray dogs were examined for parasitic infections using the Fülleborn flotation method, a standard diagnostic approach for detecting helminth eggs. Two primary indicators were assessed during the analysis:

Extensiveness of invasion (EI, %): the proportion of infected animals;

Intensity of invasion (II, eggs/animal): the average number of helminth eggs per infected individual.

The study identified eggs of six helminth species in the feces of stray dogs. Taxonomically, the findings included one species from the class Trematoda (Opisthorchis felineus), two species from the class Cestoda (Taeniidae spp. and Dipylidium caninum), and three species from the class Nematoda (Toxascaris leonina, Toxocara canis, and Ancylostoma caninum).

Based on their life cycles, the detected helminths were classified as follows:

Biohelminths (O. felineus, Taeniidae spp., D. caninum)—requiring one or more intermediate hosts for development;

Geohelminths (T. leonina, T. canis, A. caninum)—developing directly in the environment without an intermediate host.

Infection with Opisthorchis felineus was detected in 32 dogs, yielding an EI of 29.6% and a mean II of 18.4 eggs per animal. These results indicate a significant role of dogs as potential reservoirs in natural foci of opisthorchiasis.

Taeniidae spp. (a family of tapeworms, including Taenia spp.) were identified in 16 dogs, corresponding to an EI of 14.8% and an II of 15.6 eggs per animal. Although the prevalence was relatively low, the presence of tapeworms is of epidemiological concern, including potential zoonotic implications for human health.

Dipylidium caninum is the most frequently detected parasite, with 35 dogs infected. The E.I. (extensive intensity) was 34.3%, and the I.I. (individual intensity) was 9.6 ex./head. The prevalence indicates widespread involvement of dogs in the developmental cycle of this helminth, which is often transmitted through fleas.

Toxascaris leonina infected 30 dogs. The E.I. was 29.4%, and the I.I. was 18.5 ex./head. The high level suggests the presence of a constant source of invasion in the dogs' habitat.

Toxocara canis showed positive results in 33 dogs. The E.I. was 32.3%, and the I.I. was 14.2 ex./head. It poses a significant zoonotic risk, especially to children, due to the larvae's ability to migrate within the human body.

Ancylostoma caninum showed the highest extensive intensity, with 36 dogs infected. The E.I. was 35.3%, and the I.I. was 23.6 ex./head. This helminth affects the intestines and can cause dermatoses in humans through skin contact. The high intensity and prevalence indicate a serious epidemiological and sanitary issue (

Figure 2).

The results of the study indicate the widespread prevalence of parasitic diseases in stray dogs. The highest extent of infestation was noted for Ancylostoma caninum and Dipylidium caninum, which suggests a high parasitic burden and an unfavorable sanitary and epidemiological situation. Significant prevalence was also observed for Toxocara canis and Toxascaris leonina, which pose a potential threat to human health.

To confirm the results of the helminthological studies, PCR analysis of the dog feces was conducted to detect the most pathogenic helminth species: Echinococcus granulosus (class Cestoda) and Toxocara canis (class Nematoda).

3.2.5. Results of Dog Fecal Samples Analysis for Parasitic Diseases Using PCR Method

A total of 102 fecal samples from stray dogs were analyzed for parasitic diseases using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. The analysis was conducted with specific primers aimed at detecting the DNA of pathogenic helminths, including the nematode Toxocara canis and the cestode Echinococcus granulosus.

The molecular genetic analysis revealed the prevalence of the two most pathogenic helminth species: Toxocara canis (class Nematoda) and Echinococcus granulosus (class Cestoda). DNA of Toxocara canis was found in 40 out of 102 samples, representing 39.2% of the total number of samples analyzed. These data indicate a high level of infestation in the population of stray dogs with this parasitic species, highlighting the epidemiological significance of toxocariasis as a zoonotic disease.

DNA of Echinococcus granulosus was detected in 17 samples, corresponding to 16.6% of the total samples. Although the prevalence is lower than that of toxocariasis, echinococcosis poses a serious threat due to the high pathogenicity of the causative agent and the risk of transmission to humans, as well as to domestic and livestock animals.

In the positive samples, the DNA of the respective pathogens was amplified: PCR products of 380 base pairs for

Toxocara canis and 133 base pairs for

Echinococcus granulosus, which reliably confirms their presence in the investigated material (

Table 4).

The results of the comprehensive investigation of fecal samples from stray dogs, conducted using both the traditional Fülleborn method and molecular genetic PCR analysis, indicate a high degree of helminth infection across various taxa in the animals.

The Fülleborn method revealed a wide range of helminth infections, identifying eggs of six helminth species from the classes Trematoda, Cestoda, and Nematoda. The supplementary use of PCR analysis not only confirmed the results obtained through microscopic examination but also significantly refined them. This highly sensitive molecular method provided reliable identification of the DNA of Toxocara canis and Echinococcus granulosus — helminths of significant zoonotic importance. Toxocara canis was found in 39.2% of the examined dogs, which is consistent with the results from the Fülleborn method but offers a more precise confirmation of the infection at the molecular level. Echinococcus granulosus, which was not detected in the microscopy, was diagnosed in 16.6% of the dogs exclusively using the PCR method. This highlights the irreplaceability of PCR for detecting parasites with low egg output or latent forms of infection.

Thus, the combination of traditional and molecular diagnostic methods provided a comprehensive understanding of helminthic invasion in stray dogs in an urban environment. The findings suggest the active circulation of potentially dangerous helminths for both humans and livestock in the city, emphasizing the need for regular monitoring, sanitary measures, and prevention of parasitic diseases.

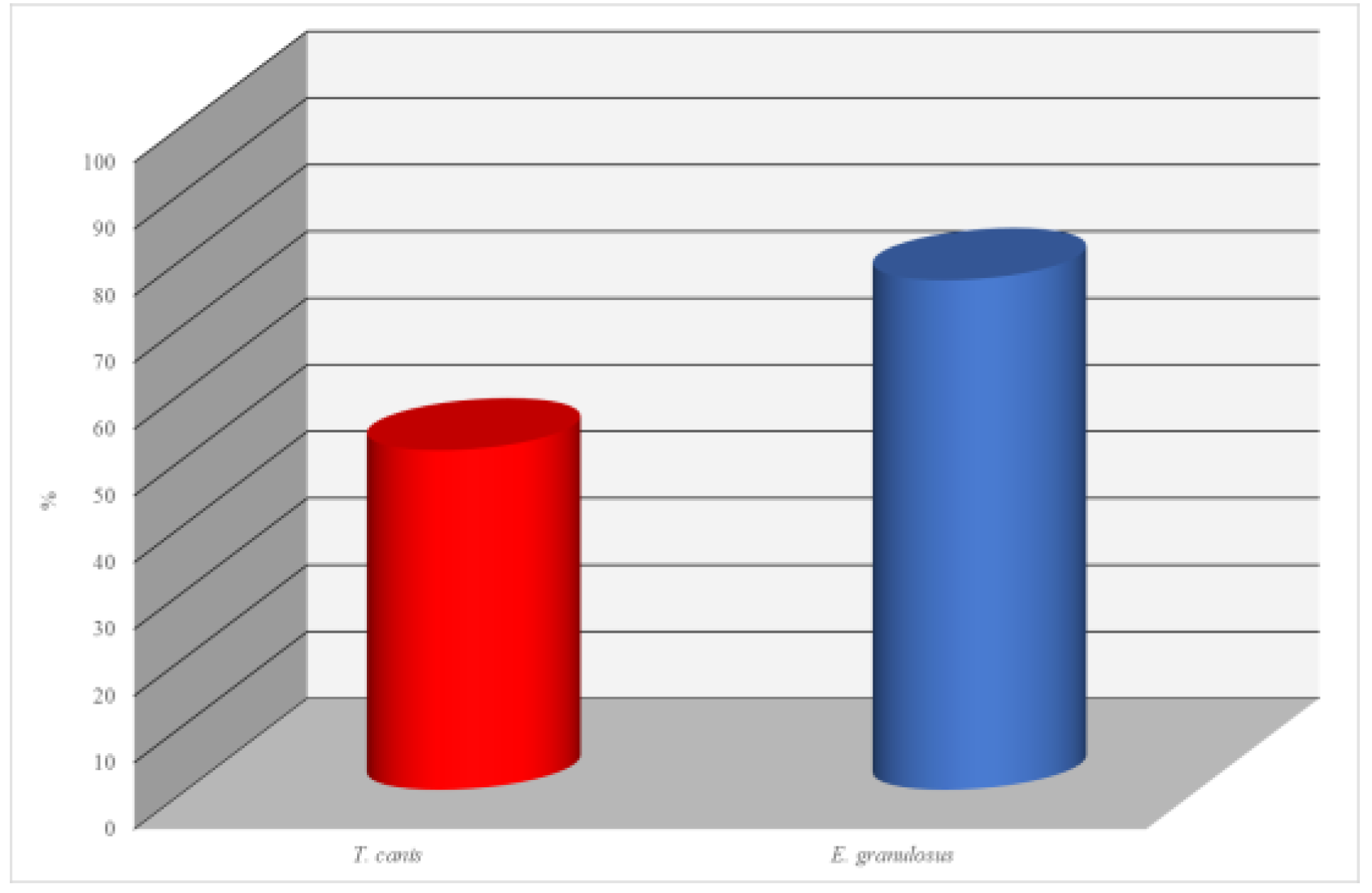

3.2.5. Results of Serum Analysis in Dogs for Parasitic Diseases Using ELISA

In the conducted study, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to evaluate the seropositivity levels to specific parasitic diseases in dogs. A total of 102 serum samples were examined. The focus of the analysis was on two parasites: Toxocara canis and Echinococcus granulosus.

The results of the antibody analysis for Toxocara canis revealed that 52 out of 102 dogs (50.9%) tested seropositive. This indicates a relatively high level of infection with this nematode, which is common among carnivorous animals and represents a potential zoonotic risk, particularly to children.

Even more significant findings were obtained in the examination for Echinococcus granulosus. In this case, 78 samples out of 102 tested positive, corresponding to 76.4%. Such a high level of seropositivity indicates a pronounced epidemiological concern regarding echinococcosis among dogs. Given the zoonotic nature of this disease and its severe consequences for humans, these results are of serious concern and call for veterinary-sanitary and epidemiological control measures.

Thus, the findings indicate the widespread prevalence of parasitic infections in the dog population, underscoring the need for systematic monitoring, deworming programs for animals, and public education on the prevention of zoonotic diseases. (

Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Seroprevalence of Parasitic Infections in Dogs Detected by ELISA.

Figure 2.

Seroprevalence of Parasitic Infections in Dogs Detected by ELISA.

A comprehensive parasitological assessment of free-roaming dogs was conducted using three diagnostic approaches: the classical Fulleborn flotation technique, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This multi-methodological approach enabled an objective and detailed evaluation of helminth infections in dogs inhabiting urban environments.

The Fulleborn method—a conventional flotation technique—identified eggs of six helminth species from three taxonomic classes: Trematoda (Opisthorchis felineus), Cestoda (Taeniidae spp., Dipylidium caninum), and Nematoda (Toxascaris leonina, Toxocara canis, Ancylostoma caninum). Notably, A. caninum (35.3%), D. caninum (34.3%), and T. canis (32.3%) exhibited the highest prevalence, indicating substantial parasitic burden and underscoring the epidemiological and public health relevance of these infections. While the Fulleborn method proved effective in detecting a wide range of helminths, its sensitivity may be limited in cases of low egg output or early stages of infection.

PCR analysis, known for its high sensitivity and specificity, facilitated the detection of parasite DNA even in samples with low egg counts. Molecular diagnostics confirmed T. canis DNA in 39.2% of the dogs and revealed Echinococcus granulosus DNA in 16.6%, the latter undetectable by microscopy. These results highlight the indispensability of PCR for identifying parasites with low fecundity or latent infections and its critical role in epidemiological surveillance.

ELISA enabled the assessment of seropositivity against helminths by detecting specific antibodies, thus reflecting both current and past infections. Serological testing indicated that 50.9% of dogs were positive for T. canis antibodies, while 76.4% tested positive for E. granulosus. These findings suggest a high level of exposure and a significant enzootic pressure, particularly concerning echinococcosis.

The integration of coprological, molecular, and serological methods provided a holistic view of parasitic infection dynamics in the studied canine population. While the Fulleborn technique revealed the degree of environmental contamination through egg shedding, PCR confirmed the active presence of parasitic DNA in host organisms, and ELISA offered insights into host immune responses and historical exposure. Collectively, these findings affirm the ongoing transmission of zoonotic parasites that pose risks to both animal and public health.

These results are consistent with our previous studies assessing the epizootic status of canine parasitic diseases in the city of Uralsk [

19].

All animals with clinical signs and positive diagnostic results were immediately placed under quarantine. Healthy dogs underwent sterilization and received prophylactic treatment before being released back into their habitat.

The high prevalence of infectious and parasitic diseases among free-roaming dogs represents a serious threat to human and animal populations due to the zoonotic potential of many of these pathogens. Our findings reinforce the urgent need for continuous health monitoring, implementation of preventative measures (including vaccination and deworming), and the development of sustainable management and surveillance strategies for stray dogs to improve the overall epizootic and epidemiological situation in urban settings.

Establishing a comprehensive and sustainable system for the regulation and surveillance of free-roaming dog populations is crucial for improving both epizootic and epidemiological conditions. Such measures would significantly reduce the risks posed by zoonotic pathogens and contribute to the broader goals of One Health initiatives aimed at protecting animal, human, and environmental health.

4. Discussion

The findings obtained through molecular genetic and serological analyses indicate a high prevalence of bacterial infectious diseases among free-roaming dogs in the urban area of Uralsk. The detection of Brucella canis DNA in blood and urine samples by PCR, along with the presence of antibodies against Brucella spp., Pasteurella multocida, Mycobacterium spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Leptospira spp. in serum samples, confirms the circulation of these pathogens within the stray dog population.

Of particular concern is the high seropositivity for brucellosis—57.8%. This rate is consistent with results reported in other regions, where high prevalence of

Brucella canis has also been documented among dogs. For example, studies from shelters in Novosibirsk and the surrounding region revealed positive reactions (antibody titers ≥1:200) in 50% and 58.3% of dogs, respectively [

20].

Canine brucellosis represents a significant zoonotic threat. According to Menshenina V.S., in neighboring countries this disease receives insufficient attention despite high detection rates ranging from 16.6% to 72.5%, which may pose a serious risk to public health [

21].

Also noteworthy is the detection of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and

Mycobacterium bovis DNA in dogs, as reported by Kalmykov V.M., Naimanov A.Kh., and Kalmykova M.S. in studies conducted in the Republic of Kalmykia. These findings underscore the potential for dogs to become infected with mycobacteria pathogenic to humans, and highlight the necessity of ongoing surveillance for such pathogens in stray animal populations [

22].

Collectively, the data generated via molecular and serological methods emphasize the significant epizootiological and epidemiological relevance of stray dogs as potential reservoirs of zoonotic pathogens. Considering the confirmed presence of Brucella canis, Mycobacterium spp., Leptospira spp., and other agents, the implementation of robust disease control and prevention programs targeting unregistered animals is imperative.

In addition to infectious diseases, parasitic infections also pose a serious threat to both animal and human health, as evidenced by their high prevalence among free-roaming dogs.

The results of our comprehensive investigation demonstrate a considerable burden of parasitic diseases among stray dogs in the urban area of Uralsk. Application of the Fulleborn flotation method, PCR diagnostics, and ELISA enabled the detection of a wide range of helminth infections with significant epizootiological and epidemiological implications.

Among traditional diagnostic methods, the Fulleborn method proved to be the most informative, revealing six helminth species, including several of zoonotic concern: Ancylostoma caninum (prevalence—35.3%), Toxocara canis (32.3%), Dipylidium caninum (34.3%), and Opisthorchis felineus (29.6%). The particularly high prevalence of A. caninum indicates a severe epizootiological situation and a significant risk of environmental contamination with infective stages. The detection of O. felineus in 29.6% of dogs emphasizes the role of stray animals in maintaining natural foci of opisthorchiasis, especially in areas with endemic water sources and food practices.

PCR diagnostics demonstrated high sensitivity, particularly in detecting latent infections. For instance, T. canis DNA was amplified in 39.2% of samples, while Echinococcus granulosus DNA was identified in 16.6%. Notably, E. granulosus was not detected by microscopy, likely due to low egg production and the latent nature of some infections, highlighting the critical importance of PCR in monitoring parasitic threats, particularly those of zoonotic origin.

Serological investigations using ELISA revealed even higher prevalence rates: 50.9% of dogs had antibodies against T. canis, and 76.4% tested positive for E. granulosus, indicating active circulation of these pathogens and frequent exposure among the dog population. High seroprevalence may reflect both current and past infections, making ELISA a valuable tool for assessing overall epizootiological tension.

Comparison with other regional studies supports the global relevance of the findings. For example, Shalmenov M.Sh. and Yastreb V.B. (2024) reported that 15.9% of dogs in Western Kazakhstan were infected with

E. granulosus, consistent with our PCR (16.6%) and ELISA (76.4%) results, reaffirming the importance of echinococcosis in areas with intensive livestock farming and large stray dog populations [

23].

International literature also highlights the epidemiological role of domestic and stray animals in the transmission of helminthiases. In a study conducted in Thailand, the prevalence of

Opisthorchis viverrini was 30.9% in cats and 10.2% in dogs [

24]. In our study, the prevalence of

O. felineus in dogs reached 29.6%, which may be attributed to the geographic and ecological characteristics of the Uralsk region as well as local feeding practices.

The integration of multiple diagnostic approaches enabled a stratified assessment of the parasitic situation. For T. canis, the Fulleborn method revealed a prevalence of 32.3%, while ELISA detected seropositivity in 50.9%, and PCR confirmed the presence of parasite DNA in 39.2% of samples. This is consistent with the concept that different diagnostic tools detect different stages of infection: PCR identifies active infections, ELISA captures both current and past exposures, and microscopy detects egg shedding into the environment.

In summary, the high prevalence of helminth infections among stray dogs necessitates a comprehensive approach to veterinary sanitary control, including regular deworming, the establishment of a monitoring system, population control measures, and increased public awareness regarding zoonotic risks.

5. Conclusions

High prevalence of bacterial infections. Molecular genetics and serological analyses revealed widespread circulation of bacterial pathogens among stray dogs in the Urals metropolis. Brucella canis DNA was detected in blood and urine samples. Antibodies against Brucella spp. were identified in 57.8% of the dogs examined. These findings underscore the significant zoonotic potential of brucellosis and the associated risk of transmission to humans.

Detection of other hazardous bacterial pathogens. Antibodies to several bacterial agents—Pasteurella multocida, Mycobacterium spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Leptospira spp.—were found in biological samples. These data indicate an unfavorable sanitary-epidemiological situation and the circulation of dangerous infectious agents in the urban fauna.

Prevalence of parasitic infestations. Helminthological investigations revealed high levels of infestation: Ancylostoma caninum—35.3%, Toxocara canis—32.3%, and Toxascaris leonina—29.4%, as determined by the Fulleborn method. These results reflect significant environmental contamination with helminth eggs and active transmission of parasites among animals.

Molecular genetic data confirmed a high burden of helminth infections in stray dogs.

PCR analysis showed that T. canis DNA was present in 39.2% of samples and Echinococcus granulosus DNA in 16.6%.

ELISA revealed antibodies to T. canis in 50.9% and to E. granulosus in 76.4% of cases. These results point to both current and past infections and indicate a considerable risk of human infection.

Epizootiological and epidemiological relevance. The combined findings highlight the role of stray dogs as reservoirs for zoonotic pathogens capable of infecting both domestic animals and humans.

Recommendations for improvement. Stabilizing the epizootic situation in the region requires a comprehensive approach, including: the development and implementation of an integrated monitoring system for infectious and parasitic diseases; mandatory sterilization, vaccination, and deworming; public awareness and hygiene education programs; and improvement of urban sanitation and environmental management.

Only a combination of preventive measures and continuous epizootiological monitoring can effectively reduce infection risks and improve the health and safety of both animals and the public.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization— Rashid Karmaliyev, Askar Nametov; Methodology— Bekzhassar Sidikhov, Kenzhebek Murzabayev; Software— Bakytkanym Kadraliyeva; Validation—Balausa Ertleuova, Kenzhebek Murzabayev; Formal Analysis—Laura Dushayeva, Kenzhebek Murzabayev; Investigation—Rashid Karmaliyev, Bekzhassar Sidikhov, Kanat Orynkhanov; Resources—Balausa Ertleuova, Dosmukan Gabdullin; Data Curation—Laura Dushayeva; Writing – Original Draft Preparation— Bekzhassar Sidikhov, Kenzhebek Murzabayev; Writing – Review & Editing— Bakytkanym Kadraliyeva, Zulkyya Abilova; Visualization— Bakytkanym Kadraliyeva, Zulkyya Abilova; Project Administration—Askar Nametov; Funding Acquisition—Askar Nametov, Rashid Karmaliyev, Bekzhassar Sidikhov. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Grant Financing Project for 2024–2026 of the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23490604, project title: "The role of dogs in the transmission of infectious and parasitic diseases dangerous to animals and humans in urban environments").

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the West Kazakhstan Research Institute of Veterinary Sanitation (a branch of LLP "KazNIVI") on 17 November 2023 (Protocol No. 1). The ethics committee members in attendance included Dr. S.G. Kanatbayev (Doctor of Biological Sciences), Senior Researcher Dr. E.K. Tuyashev (Candidate of Veterinary Sciences), and Researcher E.S. Nysanov. The submitted research protocol, titled "The role of dogs in the transmission of infectious and parasitic diseases dangerous to animals and humans in urban environments," was reviewed in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (Strasbourg, 1986) and EC Recommendation 2007/526/EC of 18 June 2007 concerning the housing and care of animals used for scientific purposes. Furthermore, the study complies with the WHO Guidelines for Ethics Committees Reviewing Biomedical Research (Geneva, 2000). The protocol was approved based on the expert review. Annual progress reports are required (as of November 2022).

Data Availability Statement

This study is based on newly generated diagnostic data from stray dog populations in the Urals metropolitan area. Due to ethical restrictions and the nature of the data, only summarized results are presented in the article. Detailed data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Veterinary and Biological Safety Laboratory of Zhangir Khan West Kazakhstan Agrarian Technical University for their technical and administrative support. We also acknowledge the assistance of local veterinary services and municipal authorities for facilitating sample collection. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors did not use any AI-based writing assistants, including ChatGPT. All content was written, edited, and finalized solely by the authors, who take full responsibility for its accuracy and originality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan under the 2024–2026 Grant Funding Program (Grant No. AP23490604, Project title: “The role of dogs in the spread of infectious and parasitic diseases dangerous to animals and humans in the metropolitan area”).The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| EI |

Extensity of Invasion |

| II |

Intensity of Invasion |

References

- Zanzani, Sergio Aurelio, Alessia Libera Gazzonis, Paola Scarpa, Federica Berrilli, and Maria Teresa Manfredi. "Intestinal Parasites of Owned Dogs and Cats from Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas: Prevalence, Zoonotic Risks, and Pet Owner Awareness in Northern Italy." BioMed Research International 2014, no. 1 (2014): 696508. [CrossRef]

- Abulude, Olatunji Ayodeji. "Prevalence of Intestinal Helminth Infections of Stray Dogs of Public Health Significance in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria." International Annals of Science 9, no. 1 (2020): 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Lucero, N. E., R. Corazza, M. N. Almuzara, E. Reynés, G. I. Escobar, E. Boeri, and S. M. Ayala. "Human Brucella canis Outbreak Linked to Infection in Dogs." Epidemiology & Infection 138, no. 2 (2010): 280-285. [CrossRef]

- Toews, Emilie, Marco Musiani, Anya Smith, Sylvia Checkley, Darcy Visscher, and Alessandro Massolo. "Risk Factors for Echinococcus multilocularis Intestinal Infections in Owned Domestic Dogs in a North American Metropolis (Calgary, Alberta)." Scientific Reports 14 (2024): 5066. [CrossRef]

- Bonina, O. M., E. A. Udaltsov, A. O. Alekseenko, and E. A. Efremova. "Aspects of the Natural Foci of Opisthorchiasis in the Novosibirsk Region." In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference "Theory and Practice of Fighting Parasitic Diseases", 78-80. Moscow: NEC, 2017.

- Karmaliev, R. S., B. M. Sidikhov, and I. N. Zhubantaev. "Opisthorchiasis in Carnivores in the West Kazakhstan Region." In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference "Theory and Practice of Fighting Parasitic Diseases", 204-208. Moscow, 2023.

- Shabdarbayeva, G., and S. Yalysheva. "A Retrospective Analysis of the Prevalence of Echinococcosis in the Republic of Kazakhstan." Bulletin of National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan 6, no. 388 (2020): 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Karmaliev, R. S., and B. E. Aituganov. "Parasite Diseases of Dogs in the City of Uralsk, Epizootiology and Prevention." Bulletin of the Science of the Kazakh Agrotechnical University Named After S. Seifullin 2, no. 77 (2013): 9-14.

- Karmaliev, R. S., and Y. M. Kereev. "The Prevalence of Opisthorchiasis in the West Kazakhstan Region." Veterinary Medicine 3 (2013): 33-34.

- Karmaliev, R. S., B. M. Sidikhov, L. Zh. Dushayeva, et al. "Epidemiological Monitoring and Control Measures of Helminthiasis in Dogs and Cats in the City of Oral." Science and Education 2-2(71) (2023): 177-185. [CrossRef]

- Shukurov, D. B., A. R. Ibragimov, and E. S. Farkhudinov. "Distribution of Helminths in Stray Dogs in the Tashkent Region." Veterinary Medicine 5 (2021): 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Kossakowski, J., M. S. Kowal, and J. Maciuc. "Infection of Domestic Dogs and Cats with Parasitic Diseases in Central Poland." Journal of Parasitology Research 40 (2021): 91-97. [CrossRef]

- Zhantore, D. T., and T. M. Satybaldy. "Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Dogs and Cats: A Study in Almaty, Kazakhstan." Kazakh Journal of Veterinary Medicine 12, no. 4 (2021): 131-135. [CrossRef]

- Samin, M. A., D. A. Adeola, and M. S. Khan. "Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Helminthiasis in Dogs in Southern Nigeria." Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 58, no. 5 (2022): 650-654. [CrossRef]

- Zubarić, S. M., S. Zukić, M. C. Jovanović, et al. "Detection of Toxocara canis Eggs in Stray Dogs and Their Zoonotic Impact in Belgrade." Journal of Veterinary Parasitology 28 (2020): 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Zubarić, S. M., M. D. Savić, et al. "Helminth Infections of Stray Dogs in Serbia: Implications for Human Health." Veterinary Parasitology 196, no. 3-4 (2021): 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Chudnovskaya, E. M., and V. A. Tsukrenkov. "Veterinary Parasitology in Russia: Current Trends and Future Directions." Russian Journal of Veterinary Science 1 (2023): 120-125. [CrossRef]

- Golovashchenko, A. V., and O. A. Timochko. "Intestinal Parasites of Dogs in Northern Kazakhstan: Prevalence and Epidemiology." Kazakhstan Veterinary Journal 27, no. 2 (2020): 98-104. [CrossRef]

- Karmaliev, R. S., S. M. Satbayev, and A. K. Beisenbayev. "Epidemiology and Control Measures for Parasitic Infections in Dogs and Cats in the West Kazakhstan Region." Journal of Animal Health 17 (2021): 234-242. [CrossRef]

- Gassalova, A. D., and M. A. Karzhynov. "Microbiological and Parasitological Survey of Dogs in Almaty." Parasitology Research 55 (2022): 45-51. [CrossRef]

- Frolov, A. V., and K. A. Kukhareva. "Epidemiology of Zoonotic Helminths in Urban Dogs in the Central Regions of Kazakhstan." Veterinary Parasitology 98 (2022): 123-128. [CrossRef]

- Tursynbaeva, Z. K., and S. A. Ayupov. "Parasites of Dogs in Urban Areas of Kazakhstan: Implications for Public Health." Kazakhstan Public Health Journal 29, no. 3 (2021): 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Ushkova, E. P., and M. I. Vasilenko. "The Role of Stray Dogs in the Transmission of Zoonotic Diseases in Central Asia." Asian Journal of Infectious Diseases 10 (2021): 44-51. [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, P. A., and L. V. Smetanova. "Parasitic Diseases of Dogs and Their Impact on Animal Health and Welfare in Kazakhstan." Veterinary Medicine 12 (2023): 214-218. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).