Submitted:

19 August 2024

Posted:

21 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

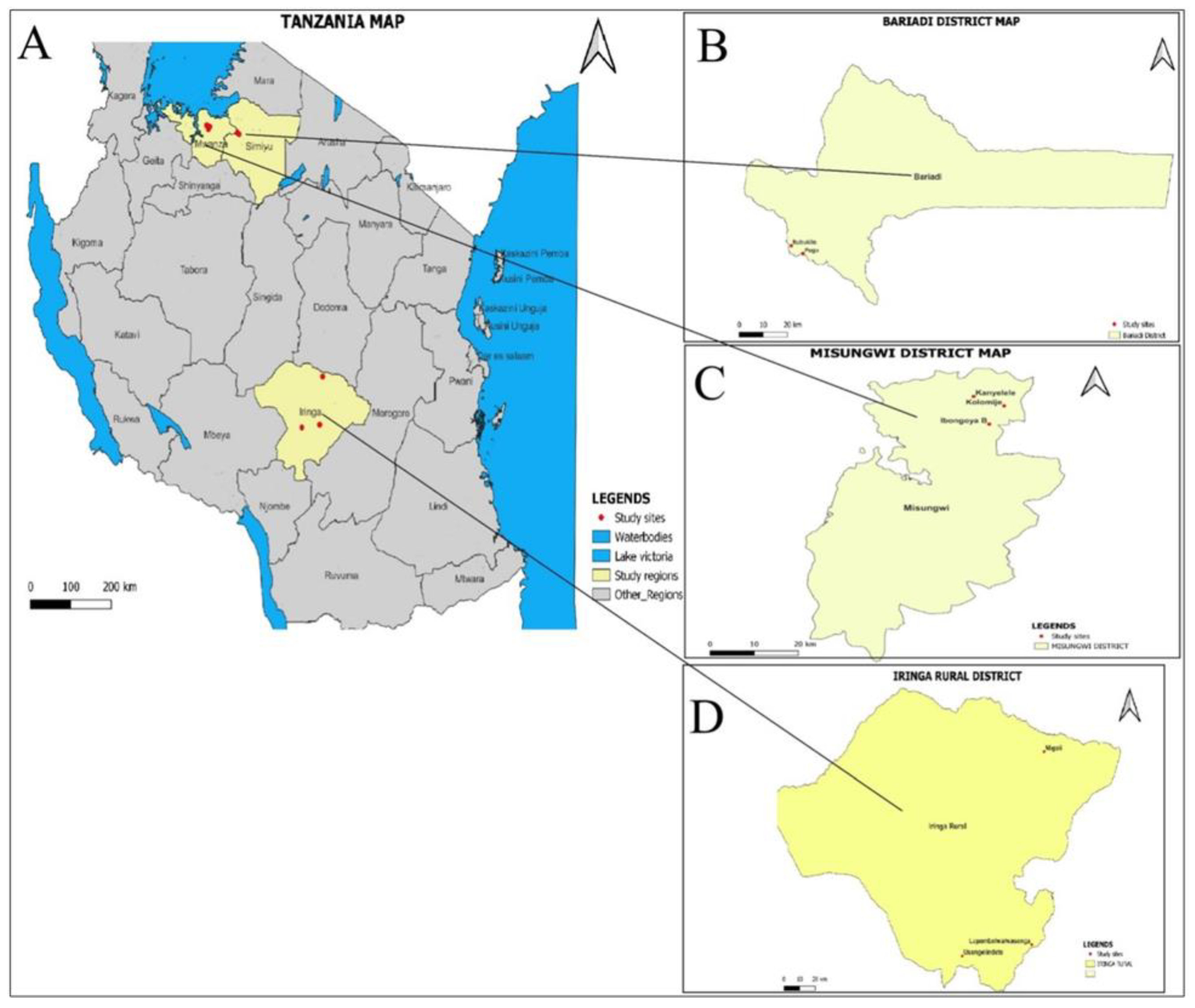

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Design and Sampling Procedure

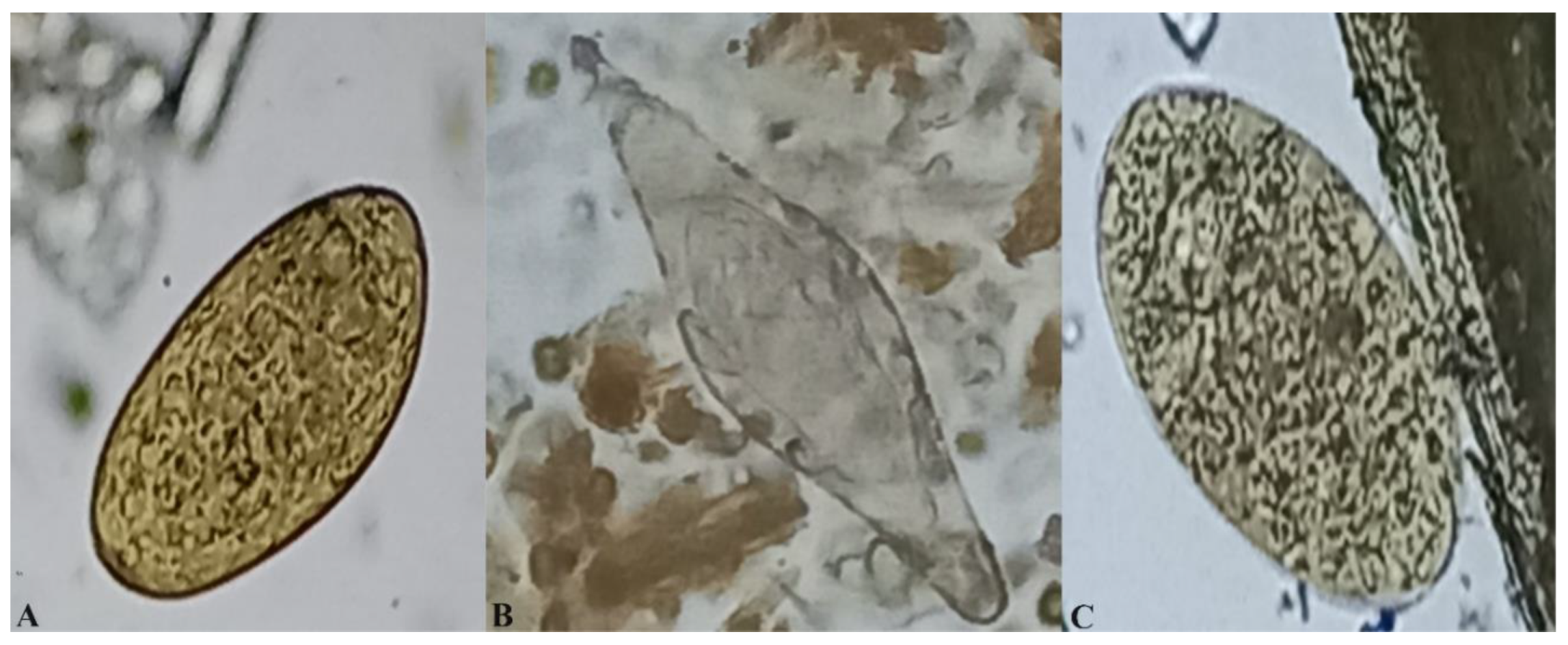

2.3. Coprological Examination

2.4. Mapping of Study Villages and Study Farms

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Animal Population Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence of F. gigantica, Paramphistomes and S. bovis

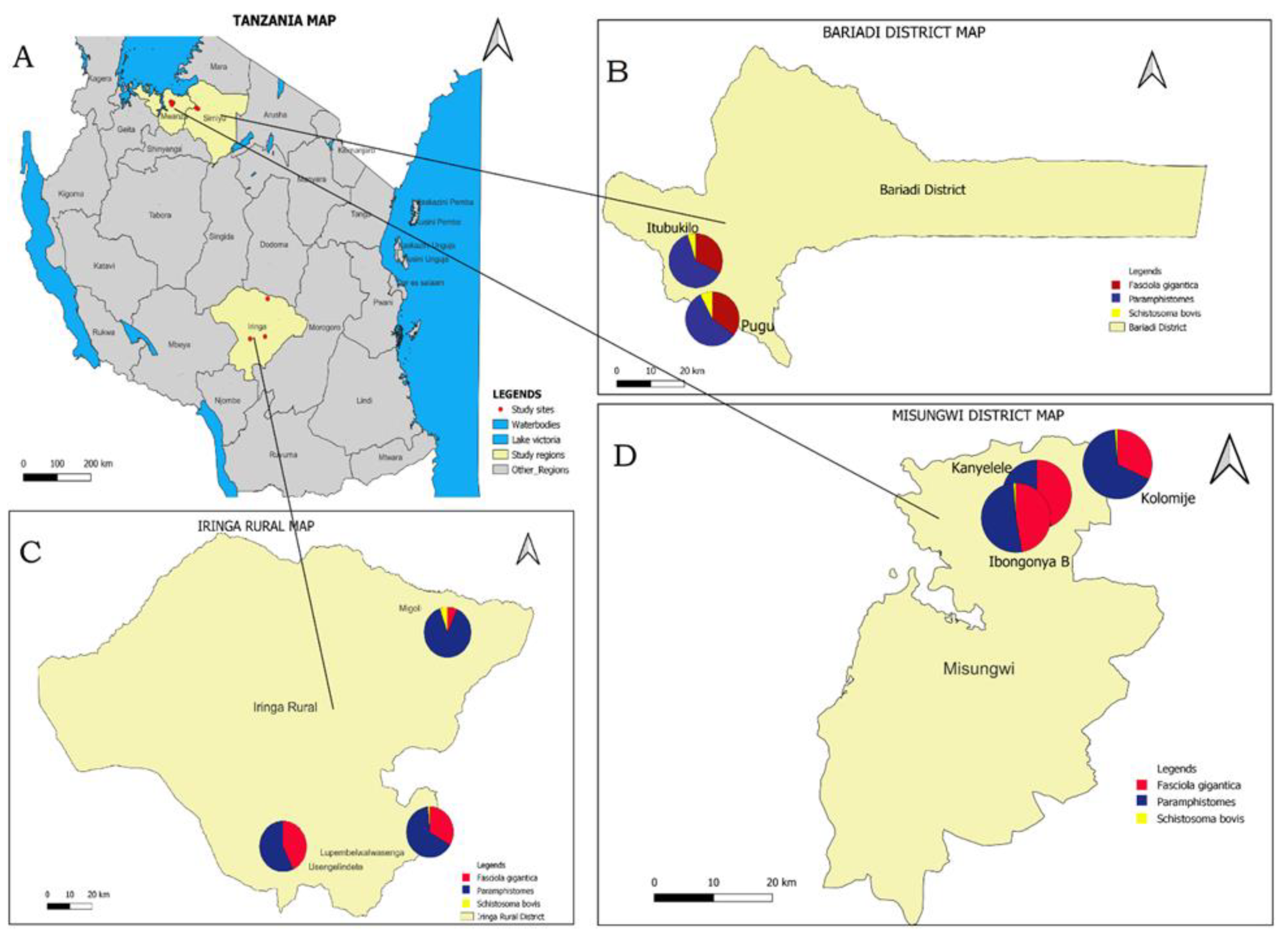

3.3. Spatial Distribution of Infections with F. gigantica, Paramphistomes and S. bovis

3.4. Fecal Egg Count

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mage, C.; Bourgne, H.; Toullieu, J.M.; Rondelaud, D.; Dreyfuss, G. Fasciola hepatica and Paramphistomum daubneyi: changes in prevalences of natural infections in cattle and in Lymnaeatruncatula from central France over the past 12 years. Veterinary research 2002, 33, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swai, E.S.; Ulicky, E. An evaluation of the economic losses resulting from condemnation of cattle livers and loss of carcass weight due to fasciolosis: a case study from Hai town abattoir, Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. Domesticated ruminants Res Rural Dev 2009, 21, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, G.M.; Armour, J.; Duncan, J.; Dunn, A.; Jennings, F.W. "Veterinary parasitology 2003, 2nd ed. Black well science Ltd." 252.

- Mas-Coma, S.; Valero, M.A.; Bargues, M.D. Fasciola, lymnaeids and human fascioliasis, with a global overview on disease transmission, epidemiology, evolutionary genetics, molecular epidemiology and control. Advances in parasitology 2009, 69, 41–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss, G.; Alarion, N.; Vignoles, P.; Rondelaud. D. A retrospective study on the metacercarial production of Fasciola hepatica from experimentally infected Galba truncatula in central France. Parasitology Research 2006, 98, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Ai, L.; Xu, X.N.; Jiao, J.; Zhu, T.; Su, H.; Zang, W.; Luo, J.; Guo, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhou, X. “An Outbreak of Human Fascioliasis Gigantica in Southwest China.” PLoS ONE, 2023, 8.

- Keyyu, J.D.; Monrad, J.; Kyvsgaard, N.C.; Kassuku, A.A. Epidemiology of F. gigantica and amphistomes in cattle on traditional, small-scale dairy and large-scale dairy farms in the southern highlands of Tanzania. Trop Anim Health Pro 2005, 37, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.M.; Makundi, A.E.; Namuba, F.V.; Kassuku, A.A.; Keyyu, J.; Hoey, E.M.; Prodohl, P.; Stothard, J.R.; Trudgett, A. The distribution of Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica within southern Tanzania–constraints associated with the intermediate host. Parasitology 2008, 135, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassuku, A.A.; Christensen, N.O.; Monrad, J.; Nansen, P.; Knudsen, J. Epidemiological studies of S. bovisinIringa Region, Tanzania. Acta Trop 1986, 43, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlau, E.A. Liver fluke survey in zebu cattle of Iringa Region, Tanzania and first finding of the small fluke Dicrocoeliumhospes/Loos. Bull Epizootic Dis Afr 1970, 18:21–28.

- Mas-Coma, S.; Bargues, M.D.; Valero, M.A. Human fascioliasis infection sources, their diversity, incidence factors, analytical methods and prevention measures Parasitology 2018,145, 1665–99.

- Lai, Y.S.; Biedermann, P.; Ekpo, U.F.; Garba, A.; Mathieu, E, Midzi, N. ; Pauline, M. P.; N'Goran, E.K.; Raso, G.; Assaré, R.K.; Sacko, M.; Schur, N.; Talla, I.; Tchuenté, L.T.; Touré, S.; Winkler, M.S.; Utzinger, J,; Vounatsou, P. Spatial distribution of schistosomiasis and treatment needs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and geostatistical analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2015, 15, 927–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kouadio, J.N.; Evack, J.G.; Achi, L.Y.; Fritsche, D.; Ouattara, M.; Silué, K.D.; Bonfoh, B.; Hattendorf, J.; Utzinger, J.; Zinsstag, J.; Balmer, O.; N’Goran, E.K. “Prevalence and Distribution of livestockSchistosomiasis and Fascioliasis in Côte d’Ivoire: Results from a Cross-Sectional Survey. ” BMC Veterinary Research 2020, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schillhorn van Veen, T.W.; Folaranmi, D.O.B.; Usman, S.; Ishaya, T. Incidence of liver fluke infections (Fasciola gigantic and Dicrocoeliumhospes) in ruminants in Northern Nigeria. Tropical Animal Health and Production 1980, 12, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.S. Freshwater Snails of Africa and their Medical Importance,1994 2nd Edn. Taylor and Francis Ltd, London.

- Mungube, E.O.; Bauni, S.M.; Tenhagen, B.A.; Wamae, L.W.; Nginyi, J.M.; Mugambi, J.M. The prevalence and economic significance of F. giganticaand Stilesia hepatica in slaughtered animals in the semiarid coastal Kenya. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2006, 38, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Lond Engl 2018, 392, 1859–922.

- Saleha, A.A. Liver fluke disease (fascioliasis): epidemiology, economic impact and public health significance Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1991, 22(Suppl), 361–4.

- You, H.; Cai, P.; Tebeje, B.; Li, Y.; McManus, D. Schistosome vaccines for domestic animals. Trop Med Infect Dis 2018, 3, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Ibrahim, N.; Tafese, W.; Deneke, Y. Prevalence of bovine fasciolosis in municipal abattoir of Haramaya, Ethiopia. Food SciQualManag 2016, 48, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nonga, H.E.; Mwabonimana, M.F.; Ngowi, H.A.; Mellau, L.S.; Karimuribo, E.D. “A Retrospective Survey of Liver Fasciolosis and Stilesiosis in Domesticated ruminants Based on Abattoir Data in Arusha, Tanzania. ” Tropical Animal Health and Production 2009, 41, 1377–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzalawahe, J.; Hannah, R.; Kassuku, A.A.; Stothard, J.R.; Coles, G.C.; Eisler, M.C. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Trematocides against F. gigantica and Amphistomes Infections in Cattle, Using Fecal Egg Count Reduction Tests in Iringa Rural and Arumeru Districts, Tanzania.” Parasites and Vectors 2018, 11, 384. [Google Scholar]

- Hyera, J.M.K. Prevalence, seasonal variation and economic significance of fascioliasis in cattle as observed at Iringa abattoir between 1976–1980. Bull Anim Health Pro Afr 1984, 32, 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- Komba, E.V.G.; Mkupasi, E.M.; Mbyuzi, A.O.; Mshamu, S.; Luwumba, D.; Busagwe, Z.; Mzula, A. Sanitary practices and occurrence of zoonotic conditions in cattle at slaughter in Morogoro Municipality, Tanzania: implications for public health. Tanzania J Health Res 2012, 14, 131–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellau, L.S.B.; Nonga, H.E.; Karimuribo, E.D. A slaughterhouse survey of liver lesions in slaughtered cattle, sheep and goats at Arusha, Tanzania. Res J Vet Sci 2010, 3, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msanga, J.F. Prevalence and economic importance of F. gigantica and Stilesia hepatica in Sukuma land, Tanzania. Tanzania Vet Bull 1985, 7, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Swai, E.S.; Mtui, P.F.; Mbise, A.N.; Kaaya, E.; Sanka, P.; Loomu, P.M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasite infections in Maasai cattle in Ngorongoro District, Tanzania. Domesticated ruminants Res Rural Dev 2006, 18, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Makundi, A.E.; Kassuku, A.A.; Maselle, R.M.; Boa, M.E. Distribution, prevalence and intensity of S. bovis in cattle in Iringa District, Tanzania. Vet Parasitol 1998, 75, 59–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzania Climate, Retrieved from The Global Historical Weather and Climate Data, https://weatherandclimate.com/tanzania (accessed 29 May 2024).

- Mahoo, H. Improving research strategies to assist scaling-up of pro-poor management of natural resources in semiarid areas 2005, 82pp.

- Tanzania Climate, Retrieved from The Global Historical Weather and Climate Data, https://weatherandclimate.com/tanzania (accessed 29 May 2024).

- Nzalawahe, J.; Kassuku, A.A.; Stothard, J.R.; Coles, G.C.; Eisler, M.C. “Trematode Infections in Cattle in Arumeru District, Tanzania are Associated with Irrigation” Parasites & Vectors 2014, 7, 107. 7.

- Thrusfield, M. Veterinary epidemiology. 2018, John Wiley & Sons. Fourth edition.

- Sirois, M. Principles and practice of veterinary technology 2016, 4th edition. St. Louis, Missouri.

- Soulsby, E.J.L. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals 1982, 7th Ed. London: Baillere Tindall.

- Pfukenyi, D.M.; Monrad, J.; Mukaratirwa, S. Epidemiology and control of trematode infections in cattle in Zimbabwe: a review. J S Afr Vet Assoc 2005, 76, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeneneh, A.; Kebede, H.; Fentahun, T.; Chanie, M. Prevalence of cattle flukes infection at Andassa domesticated ruminants research center in north‒west of Ethiopia. Veterinary Research Forum 2012, 3, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dorchies, P.H. Flukes: Old parasites but new emergence. Proceedings of the XXIV World Buiatrics Congress 2006, Vol. 16 Consultada.

- Hansen, J.; Perry, B. The epidemiology, diagnosis and control of helminth parasites of ruminants, a hand book. Nairobi, Kenya: International Laboratory for Research on Animal Disease (ILRAD) 1994.

- Rolfe, P.F.; Boray, J.C.; Nichols, P.; Collins, G.H. Epidemiology of paramphistomosis in cattle. International Journal of Parasitology 1991, 21, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkamu, S. Study on prevalence and associated risk factors for bovine and human schistosomiasis in Bahir Dar and its surrounding areas. J Anim Res 2016, 6, 967–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.A. Schistosomamattheei in sheep: the host-parasite relationship. Res Vet Sci 1974, 17, 263–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakiso, B.; Menkir, S.; Desta, M. On farm study of bovine fasciolosis in Lemo district and its economic loss due to liver condemnation at Hossana municipal abattoir, southern Ethiopia. Int J CurrMicrobiolAppl Sci, 2014, 3, 1122–32. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. The Epidemiology of helminth parasites.1993 2nd ed. p. 1–30.

- Keyyu, J.D.; Kassuku, A.A.; Msalilwa, L.P.; Monrad, J.; Kyvsgaard, N.C. Cross-sectional prevalence of helminth infections in cattle on traditional, small-scale and largescale dairy farms in Iringa district, Tanzania. Vet Res Commun 2006, 30, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzalawahe, J.; Kassuku, A.A.; Russell, S.J.; Coles, G.C.; Eisler, M.C. Associations between trematode infections in cattle and freshwater snails in highland and lowland areas of Iringa. Parasitology 2015, 142, 1430–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembely, S.; Galvin, T.J.; Craig, T.M.; Traore, S. Liver fluke infections of cattle in Mali. An abattoir survey on prevalence and geographic distribution. Trop Anim Health Prod 1988, 20, 117–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elelu, N.; Ambali, A.; Coles, G.C.; Eisler, M.C. Cross-sectional study of F. gigantica and other trematode infections of cattle in Edu local government area, Kwara state, north-Central Nigeria. Parasit Vectors 2016, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cattle N=739 |

Goats N=319 |

Sheep N=309 |

Total N=1367 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) |

++ |

%(95%CI) |

|

| F.gigantica | 289 | 39.1 (35.6-42.7) | 75 | 23.5 (19.0-28.6) | 116 | 37.5 (32.1-43.2) | 480 | 35.1 (32.6-37.7) |

| paramphistomes | 484 | 65.5(61.9-68.9) | 155 | 48.6 (43.0-54.2) | 184 | 59.6 (53.8-65.1) | 823 | 60.2 (57.6-62.8) |

| S.bovis | 24 | 3.3 (2.1-4.8) | 7 | 2.2(0.9-4.5) | 12 | 3.9 (2.0-6.7) | 43 | 3.1(2.3-4.2) |

| F. gigantica+ paramhistomes | 247 | 33.4 (30.0-37.0) | 65 | 20.4(16.1-25.2) | 94 | 30.4(25.3-35.9) | 406 | 29.7(27.3-32.2) |

| F. gigantica+ S.bovis | 16 | 2.2 (1.2-3.5) | 5 | 1.6(0.5-3.6) | 11 | 3.6 (1.8-6.3) | 32 | 2.3 (1.6-3.3) |

| Paramphistomes + S. bovis | 23 | 3.1(1.9-4.6) | 7 | 2.2(0.9-4.5) | 11 | 3.6 (1.8-6.3) | 41 | 3.0 (2.2-4.0) |

| F. gigantica+ paramphistomes + S. bovis | 16 | 2.2 ((1.2-3.5) | 5 | 1.6 (0.5-3.6) | 10 | 3.2(1.6-5.9) | 31 | 2.3(1.5-3.2) |

| Overall Prevalence | 527 | 71.3 (67.9-74.5) | 165 | 51.7(46.1-57.3) | 206 | 66.7(61.1-71.9) | 898 | 65.7(63.1-68.2) |

| F.gigantica | Paramphistomes | S. bovis | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | Goat | Sheep | Cattle | Goat | Sheep | Cattle | Goat | Sheep | ||||||||||

| Region | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) | ++ | %(95%CI) |

| SIMIYU | 89 | 43(36.2-50.0) | 42 | 37.8(28.8-47.5) | 52 | 48.1(38.4-58.0) | 174 | 84.1(78.3-88.8) | 71 | 64.0(54.3-72.9) | 81 | 75(65.7-82.8) | 16 | 7.7(4.4-12.2) | 5 | 4.5(1.5-10.2) | 12 | 11.1(0.6-18.6) |

| IRINGA | 110 | 35.7 (30.4-41.3) | 3 | 2.6 (0.5-7.4) | 23 | 20.7(13.6-29.4) | 186 | 60.4(54.7-65.9) | 40 | 34.8((26.1-44.2) | 57 | 51.4(41.7-60.9) | 6 | 2(0.7-4.2) | 1 | 0.9(0.0-4.7) | 0 | 0(0.0-0.3) |

| MWANZA | 90 | 40.2 (33.7-46.9) | 30 | 32.3(22.9-42.7) | 41 | 45.6(35.0-56.4) | 124 | 55.4(48.6-62.0) | 44 | 47.3(36.9-57.9) | 46 | 51.1(40.3-61.8) | 2 | 0.9(0.1-3.2) | 1 | 1.1(0.0-5.8) | 0 | 0(0.0-0.4) |

| F.gigantica | Paramphistomes | S. bovis | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 311 | 114 | 36.7 | 207 | 66.6 | 6 | 1.93 | |||||||||

| Female | 428 | 175 | 40.9 | 1.17 | 0.87-1.59 | 0.303 | 277 | 64.7 | 0.86 | 0.63-1.19 | 0.368 | 18 | 4.21 | 1.93 | 0.75-4.98 | 0.171 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 6-24 months | 195 | 71 | 36.4 | 104 | 53.3 | 1 | 0.51 | |||||||||

| 24+ months | 543 | 218 | 40.2 | 1.16 | 0.83-1.64 | 0.380 | 379 | 69.8 | 1.98* | 1.40-2.78 | <0.001 | 23 | 4.24 | 8.5* | 1.12-64.19 | 0.038 |

| Breed | ||||||||||||||||

| Cross | 12 | 6 | 50 | 2 | 16.7 | 1 | 8.33 | |||||||||

| Local | 727 | 283 | 38.9 | 0.61 | 0.19-1.92 | 0.395 | 482 | 66.3 | 8.19* | 1.76-38.09 | 0.007 | 23 | 3.16 | 0.25 | 0.03-2.21 | 0.211 |

| F.gigantica | Paramphistomes | S. bovis | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 267 | 69 | 25.8 | 135 | 50.6 | 7 | 2.6 | |||||||||

| Female | 52 | 6 | 11.5 | 0.83 | 0.47-1.46 | 0.512 | 20 | 38.5 | 1.19 | 0.73-1.95 | 0.486 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.97 | 0.18-5.12 | 0.972 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 6-24 months | 124 | 23 | 18.6 | 59 | 47.6 | 1 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| 24+ months | 195 | 52 | 26.7 | 1.59 | 0.92-2.77 | 0.099 | 96 | 49.2 | 1.07 | 0.68-1.68 | 0.764 | 6 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 0.46-32.82 | 0.210 |

| Breed | ||||||||||||||||

| Cross | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Local | 319 | 75 | 23.5 | NA | 155 | 48.6 | NA | 7 | 2.2 | NA | ||||||

| F. gigantica | Paramphistomes | S. bovis | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | ++ | % | AOR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 108 | 42 | 38.9 | 69 | 63.9 | 3 | 2.7 | |||||||||

| Female | 199 | 73 | 36.7 | 0.89 | 0.55-1.46 | 0.650 | 115 | 57.8 | 0.76 | 0.46-1.24 | 0.265 | 9 | 4.5 | 1.63 | 0.43-6.17 | 0.472 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 6-24 months | 112 | 30 | 26.8 | 56 | 50.0 | 2 | 1.8 | |||||||||

| 24+ months | 195 | 85 | 43.6 | 2.11* | 1.28-3.51 | 0.004 | 128 | 65.7 | 1.93* | 1.20-3.10 | 0.007 | 10 | 5.1 | 2.94 | 0.63-13.71 | 0.168 |

| Breed | ||||||||||||||||

| Cross | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Local | 309 | 116 | 37.5 | NA | 184 | 59.6 | NA | 12 | 3.9 | NA | ||||||

| Variable name | N | Fasciola | Paramphistomes | Schistosome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 311 | 2.5(0.87) | 0.362 | 3.0(0.92) | 0.833 | 0.7(0.00) | 0.223 |

| Female | 428 | 2.4(0.80) | 3.0(0.07) | 0.8(0.06) | |||

| Animal age | |||||||

| Weaners | 195 | 2.3(0.13) | 0.186 | 3.0(0.13) | 0.921 | 0.7(0.00) | |

| Adult | 543 | 2.4(0.07) | 3.1(0.06) | 0.8(0.05) | |||

| Breed type | |||||||

| Local | 727 | 2.4(0.06) | 0.673 | 3.0(0.05) | 0.937 | 0.8(0.05) | |

| Cross breed | 12 | 2.2(0.20) | 2.9(1.15) | 1.4(0.00) | |||

| Animal body condition | |||||||

| Fat | 191 | 2.3(0.12) | 0.435 | 2.9(0.09) | 0.234 | 0.6(0.00) | |

| Medium | 309 | 2.5(0.06) | 2.8(0.06) | 0.8(0.05) | |||

| Lean | 239 | 2.4(0.07) | 3.1(0.09) | 1.1(0.17) | |||

| Overall | 739 | 2.4(0.06) | 3.0(0.06) | 0.8(0.05) | |||

| Goat | Sheep | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Fasciola | Paramphistomes | Schistosome | N | Fasciola | Paramphistomes | Schistosome | ||||||

| Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | Mean (SE) | P value | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 88 | 2.6(0.28) | 0.791 | 2.5(0.16) | 0.606 | 0.6(0.00) | 0.576 | 108 | 2.8(0.18) | 0.379 | 2.8(0.15) | 0.743 | 0.9(0.23) | 0.731 |

| Female | 231 | 2.5(0.15) | 2.6(0.11) | 0.8(0.13) | 202 | 2.6(0.15) | 2.9(0.12) | 0.8(0.10) | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| Weaners | 124 | 3.0(0.28) | 0.011 | 2.6(0.13) | 0.987 | 1.4 | 115 | 2.9(0.29) | 0.101 | 2.8(0.17) | 0.947 | 0.7(0.00) | 0.417 | |

| Adult | 195 | 2.3(0.14) | 2.6(0.12) | 0.7(0.00) | 195 | 2.5(0.11) | 2.9(0.11) | 0.9(0.11) | ||||||

| BCS | ||||||||||||||

| Lean | 8 | 2.1 | 3.1(1.33) | 20 | 2.5(0.6) | 2.7(0.43) | 0.7(0.00) | |||||||

| Medium | 247 | 2.5(0.13) | 2.7(0.09) | 0.028 | 0.8(0.66) | 216 | 2.7(0.13) | 0.765 | 2.7(0.11) | 0.067 | 0.9(0.11) | |||

| Fat | 64 | 0.7 | 1.9(0.26) | 71 | 2.2(0.16) | 3.2(0.17) | ||||||||

| Overall | 319 | 2.5(0.14) | 2.6(0.09) | 0.8(0.10) | 309 | 2.6(0.11) | 2.9(0.10) | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).