1. Introduction

Schistosomiasi

s is the most important trematode/blood fluke infection of humans [

1]. Two major schistosome species are prevalent in the African region, namely

S. mansoni and

S. haematobium, causing intestinal and urogenital schistosomiasis, respectively [

2,

3]. Tanzania is endemic for both

S. mansoni and

S. haematobium, where the prevalence of human schistosomiasis ranges from 12.7 to 87.6% [

4]. The country is the second after Nigeria, among countries with the highest burden of schistosomiasis in Sub-Saharan Africa [

4]. The prevalence of schistosomiasis is highest in rural communities with limited access to clean and safe water, proper sanitation, and hygiene facilities [

4]. Schistosomiasis transmission is determined by water contamination by viable schistosome eggs , the presence of snail intermediate hosts, in which the ciliated miracidia stage can penetrate and develop into infective cercariae, and ongoing human water contact activities [

5].

S. mansoni infection is associated with hepatosplenic disease characterized by hepatosplenomegaly and progressive periportal fibrosis (PPF), which can lead to portal hypertension and its related sequelae such as ascites, liver surface irregularities, oesophageal varices and haematemesis [

6,

7,

8], while

S. haematobium infection is associated with anaemia, nutritional deficiencies and lesions of the urogenital tract such as kidneys, urinary bladder and ureters, and cervis in women. Chronic, untreated infections can lead to cancers of the urinary bladder, such as squamous cell carcinoma [

9].

Worldwide, it is estimated that approximately 779 million people are at risk of schistosomiasis, where 250 million people are mainly from Sub-Saharan Africa [

3,

10]. Annual mortality from schistosomiasis is highly controversial, and estimates vary between 10,000 and 200,000 people worldwide [

11].

Preventive chemotherapy (PC) using mass drug administration (MDA) of praziquantel targeting primary school-aged children within the school environment is the main strategy for controlling schistosomiasis in Tanzania [

12]. However, the adult and pre-school-aged children population at any level of transmission risk is excluded from mass PC [

13]. The major drawback of this approach is leaving out other community members who are out of the school environment, such as pre-school children and adult community members. Adult community members not involved in mass preventive chemotherapy carry the highest burden of hepatosplenic disease [

6]. In addition, untreated community members maintain transmission of the disease in the environment and serve as a source of infection to treated school children [

6]. To reach the global targets of eliminating schistosomiasis as a public health problem by 2030 and responding positively to the global sustainable development goals (SDGs) of not “leaving anyone behind” and the concept of integration of intervention measures [

14], public health interventions should be integrated and reach the entire community.

Fasciolosis is caused by the liver fluke of the genus

Fasciola [

15].

Fasciola parasites have a two-host life cycle with an intermediate host (gastropod) and a final ruminant host (e.g., cattle, sheep, and buffalo). Two species are known to infect humans, namely

Fasciola hepatica (

F. hepatica) and

Fasciola gigantica (

F. gigantica), with the latter being less widespread globally but more pathogenic than

F. hepatica [

16,

17]. Humans are infected by eating raw or undercooked liver or raw, poorly washed aquatic plants with metacercaria and or drinking field water contaminated with metacercaria. Acute symptoms of

Fasciola infection include abdominal pain, loss of appetite, and fever. Chronic infections can lead to hepatomegaly and portal cirrhosis [

15].

Approximately 2.4 million people worldwide are infected with fascioliasis, while 180 million people are at risk of infection [

18]. Overall, trematode infections affect more than 10% of the world population; an estimated 14 million DALYs are lost annually due to trematode infections [

19]. Human Fascioliasis is known to be endemic throughout Africa. However, most reports come from Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Nigeria, and South Africa [

20]. Except for schistosomiasis, the impact of most human trematodes is commonly understudied [

21].

Fascioliasis and schistosomiasis are emerging snail-borne zoonotic infections with a great spreading capacity linked to animal and human movements, climate change, and anthropogenic modifications of freshwater environments. Larger-scale control interventions have been implemented in Tanzania, including mass drug administration using praziquantel (PZQ) targeting school-aged children. However, evidence has shown that the problem persists partly because adult and pre-school-aged children are excluded from treatment [

13]. However, there have not been any larger-scale control interventions against Fascioliasis in Tanzania, and the disease is not included in the Tanzania NTD Control Master Plan [

22]. On the other hand, very few studies on human fasciolosis have been conducted in Tanzania, despite the known higher prevalence of the disease in animals [

23] and the fact that the disease is zoonotic, as animals share the same environment and water bodies with humans [

23]. Further, human fascioliasis in Tanzania is not routinely diagnosed in health facilities, which might result in many ‘hidden’ cases. Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the burden of zoonotic schistosomiasis and fascioliasis, focusing on two ecological zones in Tanzania, to generate evidence that will guide the planning and implementation of targeted disease control interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

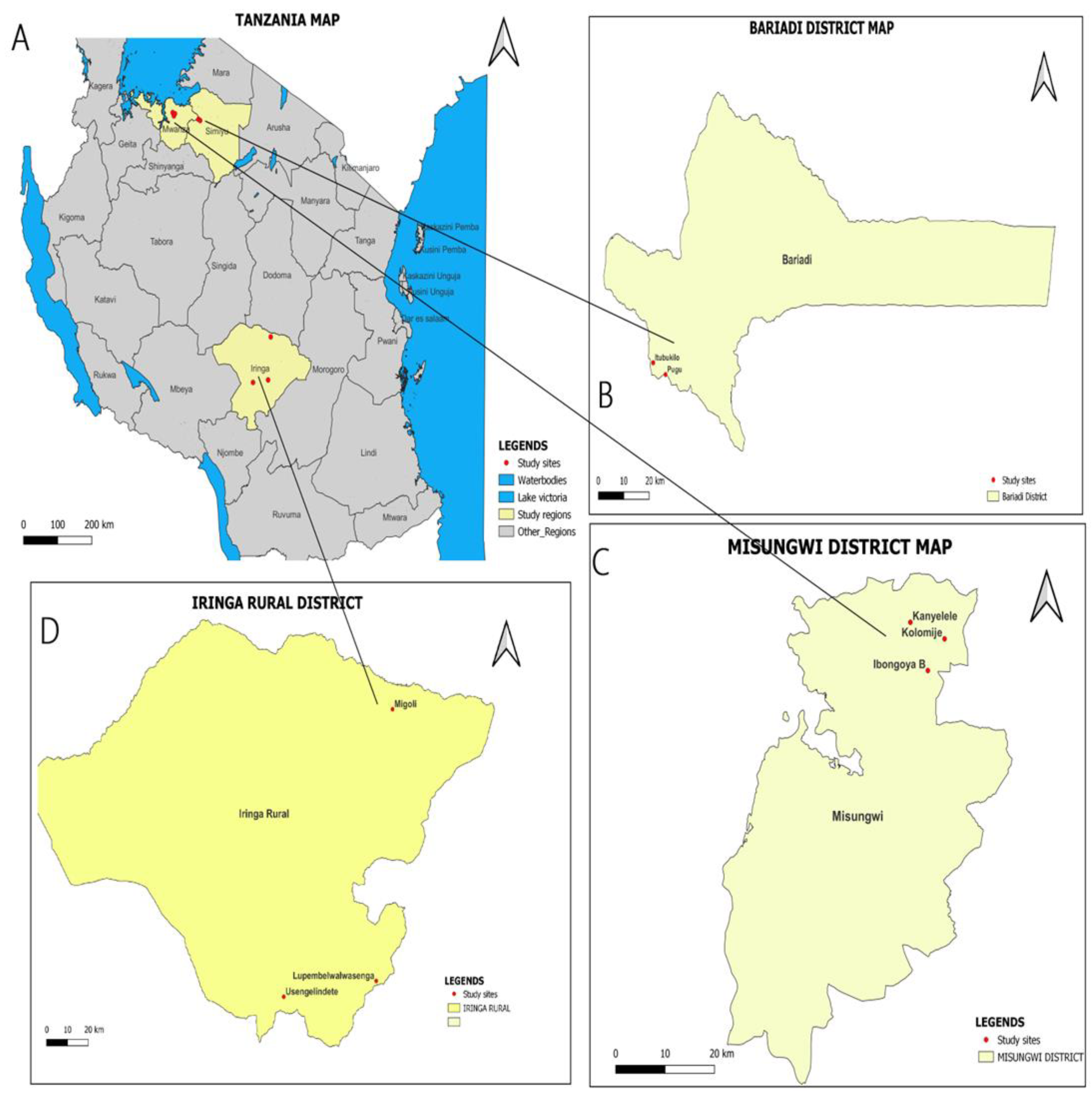

This was a cross-sectional study, conducted from March to May 2023 in Misungwi, Bariadi, and Iringa Districts, Tanzania. Misungwi district is located in Mwanza region, while Bariadi district is located in Simiyu region within the Lake Zone area of Tanzania. Iringa district is located in Iringa region in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Within the Misungwi district, the study was carried out in Kanyelele, Koromije, and Ibongoya B villages. In the Bariadi district, the study was conducted in Pugu and Itubukilo A villages. On the other hand, in the Iringa rural district, the study was conducted in Lupembelwasenga, Usengelindeti, and Migori villages (See

Figure 1). The study districts and villages were selected purposively based on the available human population, previous reports of

Fasciola infections in cattle, schistosomiasis and fascioliasis disease history, and disease epidemiology described in routine reports from the respective local District Medical offices. The location and climatic characteristics of the study districts have been described elsewhere [

23]

2.2. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

This study recruited pre-school children (≤6 years), school-aged children (7–17 years), and adults (≥ 18 years) in selected villages located along Lake Victoria and the Southern Highlands zones of Tanzania. In this study, children aged ≤17 years and adults ≥ 18 years living in the study villages, who were either male or female and had signed parent/guardian informed consent.

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Strategies

The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula:

, where P is the prevalence (%) of human schistosomiasis of 21% [

24], the desired absolute precision (d) of 2%, and the Standard normal deviate (Z) corresponding to the level of significance of 1.96 at a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used. These values were inserted into the formula, and the total sample size of 1593 was obtained.

The sampling strategy used in this study has been described elsewhere [

25]. A random selection of 150–200 preschool and school-aged children from the list of registered students in the school attendance book was made on the day of sample collection. Briefly, the selection of preschool and school-aged children to participate in the study was determined by the probability proportional to the size of the school and the class population. Systematic sampling techniques were used, with the class registers used as the sampling frame. After obtaining the sampling interval and a start point from a table of random numbers, the required number of children was selected from each class. For the selection of adults, in each school/village, 50 adults were invited to participate in the study.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Collection of participants’ demographic information

A data collection form was used to collect demographic information (age, sex, village, district, and height) for preschool, school-aged children, and adults. The structured questionnaire for preschools was administered to their caregivers (parents/guardians). The data collection form was translated to Kiswahili and back-translated to English before data entry.

2.4.2. Examination for Schistosoma mansoni using the Kato Katz technique

Duplicate Kato Katz [

26] thick smears were prepared from a single stool sample collected from each participant (preschools, school-aged children, and adults). A template of 41.7 mg was used to make the thick smears, which were examined by two independent laboratory technicians trained on the KK technique.

S. mansoni ova appeared yellowish white with a lateral spine shape against a greenish background. For quality assurance, 20% of all the positive and negative KK thick smears were re-examined by a third laboratory technician blinded to the results of the other two technicians.

2.4.3. Examination for Schistosoma haematobium infection using the urine filtration method

A single urine sample was collected from pre-school, school-aged children, and adults who participated in the study. The urine filtration method [

26] was used to screen urine samples, and light microscopy was used to examine urine filters to determine the presence of

S. haematobium eggs [

27].

Schistosoma haematobium eggs-stained orange with a terminal spine shape. Each sample was examined independently by two medical laboratory technicians. At the end of each fieldwork day, 20% of all positive and negative samples were re-examined by a third laboratory technician blinded to the results of the other two technicians.

2.4.4. Examination for Fasciola sp. infection using the Formal-Ether Concentration Method

The Formal-Ether Concentration method was used according to Uga et al. [

28] and Sato et al. [

29] with some modifications. Before observation, 10g of the collected stool samples were homogenized in the collection tube. After homogenization, samples were separated into 1 g and prepared for sedimentation. The pellet mixtures were mixed with 7 mL 10% formalin in a 15 mL conical bottom polypropylene tube (Falcon®-type tube). Three milliliters of ether were added, and the solution was shaken vigorously for at least 60 seconds, occasionally releasing the air pressure in the tube. The mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 15000 rpm. The ring of the floating residue and then the formalin were decanted. The sedimentation process was repeated twice to clarify the sediment. The remaining pellet was suspended in formol-saline up to 200 μL, from this suspension, 30μL was examined on a slide under a light microscope, completely and systematically. Two slides (coverslip of 24×32 mm) were examined under a light microscope on the same day for each sediment sample.

Fasciola sp. eggs were confirmed by egg morphology measurement, where an average of fifty eggs from each positive sample were measured and an average size was calculated.

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

Data were double-entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet for simple cleaning before being exported to STATA version 17 for further management and analysis. Continuous variables (age, egg intensities) were summarized using mean (SD) and median (IQR), as appropriate. The categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages/proportions. The Pearson Chi-square (χ2) test was used to examine associations between the prevalence of human zoonotic fascioliasis and schistosomiasis at different levels of predictor variables. An independent sample t-test for two groups and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for more than two groups were used to assess the difference in mean egg counts of

S. mansoni by sex and age groups. However, the arithmetic mean egg counts were obtained from the counts of four KK smears and multiplied by 24 to get the individuals’ eggs per gram of feces. The intensity of

S.mansoni infection was categorized according to WHO criteria, 1–99epg, 100–399epg, and ≥ 400epg, defined as low, moderate and heavy intensities infections, respectively [

30]. For

S. haematobium, infection intensities were classified into two categories as per WHO recommendation, light infection (< 50 eggs/10 ml of urine) and heavy infection (≥ 50 eggs/10 ml of urine) [

31].

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The National Health Research Ethics Committee (NATREC) of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) approved the study (ethics clearance certificate number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/360). The Methods used to collect the presented data followed the recommended standard operating procedures (SOPs). The study received further permission from regional and district authorities of the Misungwi, Bariadi, and Iringa rural districts, Tanzania. Parents and guardians of preschool and school-aged children received information through the village government and school leadership, respectively. Written informed assent and consent forms were obtained from children and parents/guardians before participation in the study. Furthermore, children provided verbal assent to ensure that their participation was voluntary. If a parent or guardian refused, the child’s name was removed from the list of participants. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. Those participants diagnosed with either S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and Fasciola were treated with PZQ at 40 mg/kg and Triclabendazole at 10mg/kg, respectively, following WHO recommendations.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

A total of 1,557 participants were recruited from Bariadi (400), Iringa (563), and Misungwi District Councils (594), respectively. Of these participants, 353 were adults (22.7%), 804 were school-aged children (51.6%), and 400 were preschool children (25.7%). The median age for school and preschool children was 12 (IQR 6-15), with more than half of the study participants 812 (52.2%) were females (

Table 1).

3.2. Prevalence and Infection Intensity of Schistosoma haematobium Infection

The overall prevalence of

S. haematobium based on the urine filtration technique was 4.9% (95% CI: 0.4–6.1%) (

Table 2). The prevalence of

S. haematobium was higher in adults (≥18 years), 5.1% [95% CI: 3.3–8.0%] compared with other age groups. However, this difference was not statistically significant (ꭓ

2=0.20, P=0.905 (

Table 2). Moreover, the prevalence of

S. haematobium was significantly higher in males, 7.7% [ꭓ

2=23.81, 0.000], than in females (

Table 2). Concerning

S. haematobium infection intensity, 3.2% (50/1557) and 1.7% (26/1557) of the participants had light and heavy infection intensity, respectively. The overall geometric mean eggs/10 ml of urine was 25.7 eggs/10 ml (95% CI: 17.3-38.1) with no significant differences among males and females (t=0.53, P=0.60) (

Table 3).

3.3. Prevalence and Intensity of Schistosoma mansoni Infection

The prevalence of

S. mansoni infection was 1.2% (95% CI: 0.7–1.9%) with no age difference but with a significant difference among sex groups 1.8% [ꭓ

2 =4.47, 0.034. The prevalence of

S. mansoni was higher in precshool children (≤6 years) compared with other age groups. However, this difference was not statistically significant (ꭓ

2=1.48, P=0.477 (

Table 2). Moreover, the prevalence of

S. mansoni was significantly higher in males, 1.8% [ꭓ

2=4.47, 0.034], than in females (

Table 2). The overall geometric mean number of epg per gram of faeces (epg) was 2.94 epg (95% CI: 1.9-4.5). No difference in mean epg of faeces was observed among sex and age groups (t = -0.01, P = 0.33, and f = 0.73, P = 0.17, respectively)(

Table 3)

3.4. Prevalence and Intensity of Fasciola Infection

The overall prevalence of

Fasciola infection was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.4–1.5%). The highest prevalence of Fasciola infection was observed in adults (≥18 years) 1.4% [95% 0.6–3.4%] but no significant difference among age groups [ꭓ

2=3.47, 0.176]. There was no significant differences in prevalence among males and females [ꭓ

2=3.56, 0.059] (

Table 2).

Figure 2.

Microscopic view of Fasciola eggs showing size measurement.

Figure 2.

Microscopic view of Fasciola eggs showing size measurement.

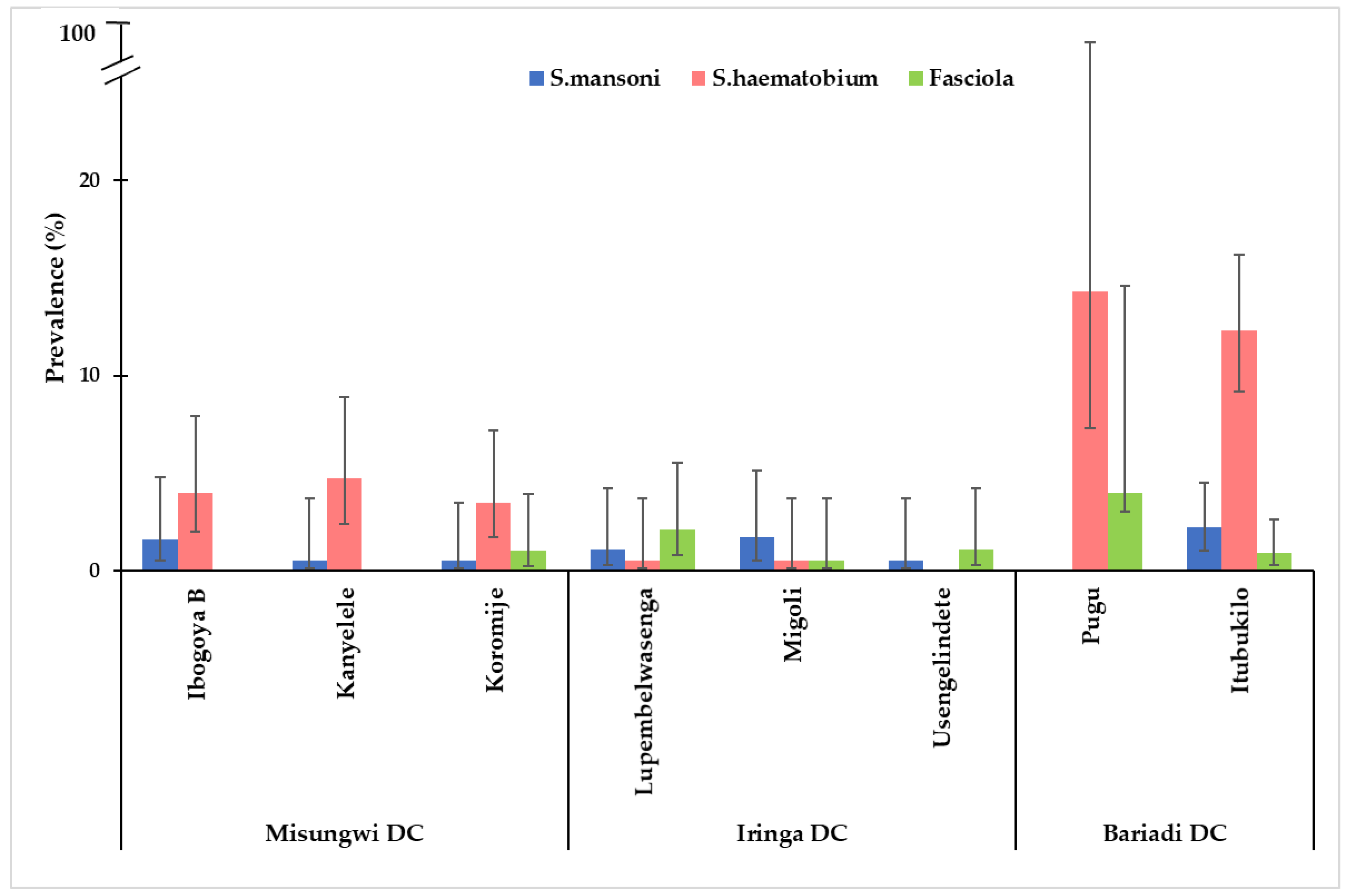

3.5. The Distribution of S. haematobium, S. mansoni, and Fasciola Infection Across Study Villages from Each District

Overall, infections of schistosomiasis and

Fasciola by villages were highly observed in the Bariadi district, with the highest prevalence of

S. haematobium infection observed in Pugu and Itubukilo villages (14.3% and 12.3%), respectively. Likewise, the prevalence of

S.mansoni was highest in Itubukilo village (2.2%) compared to other villages in other districts (

Figure 3). The

S. haematobium infection was more prevalent in all the villages in the Misungwi district compared to other districts. However, there were no

Fasciola infections observed in Ibongoya B and Kanyelele villages of the Misungwi district. Villages from the Iringa district had a lower prevalence of these infections compared to villages from other districts. Generally,

S. haematobium infection was the most prevalent trematode infection across all districts, while

S. mansoni infections were relatively low compared to other infections in all districts, and

Fasciola infection was the least prevalent trematode infection across all three districts (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The present study examined the burden and distribution of human zoonotic trematode infections, namely schistosomiasis and fascioliasis, among different age groups in two ecological zones of Tanzania. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide clear evidence of the presence and transmission of fascioliasis, urogenital and intestinal schistosomiasis among different age groups in the Lake Victoria and Southern Highlands ecological zones of Tanzania. The current study found the prevalence of

S. haematobium at 4.9%,

S. mansoni at 1.2%, and

Fasciola infection at 0.9%, indicating that these infections are prevalent in the study areas [

32].

The prevalence of

Fasciola,

S. haematobium, and

S. mansoni seems to vary across districts and villages, with the highest overall prevalence observed in districts/villages located on the Lake Victoria ecological zone compared to districts/villages on the southern highlands of Tanzania. These findings on the endemicity of

S. haematobium, S. mansoni and

Fasciola infections along Lake Victoria and the Southern highlands of Tanzania are consistent with previous research findings from Tanzania [

24,

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, this is the first study of its kind to report the presence of

Fasciola infection in Lake Victoria and the Southern highlands of Tanzania. The variation in prevalence from one epidemiological setting to another can be explained by the abundance and competence of the snail intermediate hosts, human activities leading to water contact activities such as rice farming, livestock rearing system and level of environmental contamination with human faeces [

37,

38]The overall prevalence of

S. haematobium in the studies population was comparable to reports of previous studies conducted in Zanzibar 5.4% [

39], Mtera [

36], and Masasi [

40]. However, the observed prevalence was higher than the 0.83% reported by Mazigo [

24] in the Southern highlands, Nyasa district. In contrast, the observed prevalence of

S. haematobium in the present study remained lower than that of 32.8% in Morogoro municipality [

41] and North-western Tanzania, 34.8% [

37]. The variation in prevalence of

S. haematobium from one epidemiological setting to another can be explained by the focal distribution of

S. haematobium, abundance and competence of the snail intermediate hosts, proximity of the villages/communities to transmission sites such as the lake and effectiveness of avaulable control intervention such as MDA and level of environmental contamination with human feaces [

25,

37,

38]. The observed prevalence of

S. haematobium was significantly lower in pre-school and school-aged children than in adults. Further, males were more infected with

S. haematobium than other groups, consistent with the findings from studies in Ethiopia and Senegal [

42,

43], which showed that males have a higher mean intensity of

S. haematobium infection than females. This might be due to the kinds of games males prefer, such as swimming in ponds, rivers, and lakes than their counterparts.

The overall prevalence of

S. mansoni was lower compared to the prevalence recorded in the previous studies among pre-school and school-aged children along the shoreline of Lake Victoria in north-western Tanzania and elsewhere probably due to the effective community response to the control interventions, the abundance and competence of the snail intermediate hosts, proximity of the villages/communities to transmission sites. [

24,

35,

44,

45].

The prevalence of

S. mansoni infection was associated with age group in line with previous studies, whereby it was shown that young participants had a higher prevalence compared to older age groups [

46]. This is a common observation in

S. mansoni endemic communities where the age prevalence curve shows that

S. mansoni prevalence and infection intensities usually peak at the age groups 6–19 years, thereafter, decline with increased age [

47]. The present study also noted that

S. mansoni infection starts at very young ages (<6 years), meaning that children are exposed at a very young age, which in turn calls for inclusion of the young age group in the treatment programme [

45,

48].

The overall prevalence of fascioliasis observed in the present study was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.4–1.5%). ) which is lower compared to studies conducted in Arusha [

49,

50] and elsewhere [

51,

52,

53]. These variations could be attributed to differences in ecological conditions, participants’ dietary habits, hygienic conditions, and the diagnostic test used. Further, poor fecal egg yield has been reported in patients presenting to health facilities with acute infections and abdominal symptoms [

54,

55]. The epidemiological classification set for human fascioliasis, areas are considered hypo-endemic, meso-endemic, and hyper-endemic when the prevalence of

Fasciola infection is below 1%, between 1 and 10%, and greater than 10%, respectively [

56]. Hence, the Lake Victoria and Southern highlands ecological zone of Tanzania could be regarded as the hypo-endemic region for human fascioliasis. Overall, there is underreporting of fascioliasis in humans, attributed to a lack of prioritization in both clinical and research settings in developing countries, including Tanzania, which in turn calls for a paradigm shift and prioritization of human fascioliasis as a public health problem. The current study had limitations such as small study area coverage, such that the findings might not be representative of other areas in the country, because the prevalence and distribution of schistosomiasis and human fascioliasis vary across localities based on ecology and population dynamics of snail intermediate hosts.

5. Conclusions

The present study showed that human zoonotic schistosomiasis and fascioliasis are prevalent among pre-school, school-aged children, and adults in the Lake Zone and Southern Highlands of Tanzania. The findings serve as a wake-up call for the Ministry of Health and the NTD control program in Tanzania to recognize fascioliasis as a disease of priority and incorporate Fasciola diagnosis in our routine health services, and include preschool children and adults in mass preventive chemotherapy programmes. Furthermore, there is a need for increased research focus, surveillance, and resource allocation for human fascioliasis, which remains underreported despite its economic and public health significance.

Author Contributions

GSM, SK, JN, AK, YS, GPM, MES, AS, and BJV conceptualized and designed the study; GSM, SK, YS, and JN planned and conducted the field work; GSM and JN collected and examined the fecal specimens; GSM, GPM analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; and GSM, GPM, JN, YS, AK, SK, MES, AS, and BJV revised and improved the final version of the manuscript. The authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research reported in this publication was funded partly by the PREPARE4VBD project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101000365. MES and ASS are grateful to the Knud Højgaards Foundation for its support to The Research Platform for Disease Ecology, Health and Climate (grant number 16-11-1898 and 20-11-0483).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was a part of a project called “PREPARE4VBDs” aimed at identifying, predicting, and preparing for emerging vector-borne diseases. The study adhered to the ethical approval guidelines set forth by the Medical Research Coordination Committee (MRCC) of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), which serves as the national ethics review board in Tanzania (ethics clearance certificate number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/3860).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all stud participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Regional Commissioners of Mwanza, Simiyu, and Iringa regions, the District Executive Directors and the District Medical Officers of Bariadi, Misungwi, and Iringa Rural districts and the Village and Subvillage leaders for their cooperation during field data collection. All participants are highly acknowledged. Salim Bwata, Revocatus Silayo, Aruni Haruya, Martin Anditi, and Kalebu Kihongosi are highly acknowledged for their technical assistance during field and laboratory work.

Conflicts of Interest

No competing interests were declared.

References

- Gryseels, B.; Polman, K.; Clerinx, J.; Kestens, L. Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet 2006, 368, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.G.P.; Bartley, P.B.; Sleigh, A.C.; Olds, R.; Li, Y.; Williams, G.M.; McManus, D.P. Schistosomiasis. New Eng J Med 2002, 346, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, P.; Keiser, J.; Bos, R.; Tanner, M.; Utzinger, J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006, 6, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazigo, H. D.; et al. Epidemiology and control of human schistosomiasis in Tanzania. Parasit. Vectors. 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senghor, B.; Diaw, O.T.; Doucoure, S.; Seye, M.; Diallo, A.; Talla, I.; et al. , Impact of annual Praziquantel treatment on urogenital schistosomiasis in a seasonal transmission focus in Central Senegal. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chofle, A. A.; et al. Oesophageal varices, schistosomiasis, and mortality among patients admitted with haematemesis in Mwanza, Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis 2014, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazigo, H. D.; et al. Periportal fibrosis, liver and spleen sizes among S. mansoni mono or co-infected individuals with human immunodeficiency virus-1 in fishing villages along Lake Victoria shores, North-Western, Tanzania. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malenganisho, W. L.; et al. Schistosoma mansoni morbidity among adults in two villages along Lake Victoria shores in Mwanza District, Tanzania. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg 2008, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, M. J.; et al. Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. ActaTrop. 2003, 86, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P. J.; Brindley, P. J.; Jeffery, M. B.; King, C. H.; Pearce, E. J.; and Jacobson, J. ‘Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases’, The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2008,118, 1311.

- WHO. Schistosomiasis: Progress Report 2001–2011, Strategic Plan 2012–2020 2013https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2011.10.006 (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2012).

- WHO (2017a) Field use of molluscicides in schistosomiasis control programs: an operational manual for program managers. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254641.

- Faust, C. L.; Osakunor, D.N.M.; Downs. JA.; Kayuni, S.; Stothard, J.R.; Lamberton, P.H.L.; et al. Schistosomiasis Control: Leave No Age Group Behind. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 582–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ending the Neglect to Attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A Road Map for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021–2030, WHO. 2020.

- Toledo, R.; and Fried, B. Digenetic Trematodes, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer-Verlag, New York. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Coma, S.; Valero, MA.; Bargues, MD. Climate change effects on trematodiases, with emphasis on zoonotic fascioliasis and schistosomiasis. Vet Parasitol. 2009, 163, 264–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyyu J., D.; Monrad, J.; Kyvsgaard N., C.; Kassuku, A. A. Epidemiology of Fasciola gigantica and Amphistomes in cattle on traditional, small-scale dairy and large-scale dairy farms in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2005, 37, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degheidy, N. S and Al-Malki, J. S. Epidemiological studies of fasciolosis in humans and animals at Taif, Saudi Arabia. World Appl Sci J 2012, 19, 1099104. [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo, A. Helminth Infections and Their Impact on Global Public Health, Clinical Infectious Diseases 2015. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, K.; Bargues, M. D.; and Neill, S. O. ‘Fasciolosis: A worldwide parasitic disease of importance in travel medicine’, Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. Elsevier Ltd, 2014, 12, 636–649. [CrossRef]

- Harhay, M. O.; Horton, J.; and Olliaro, P. L. ‘Epidemiology, and control of human gastrointestinal parasites in children,’ Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy, 2010, 8, 219–234. [CrossRef]

- Tanzania Ministry of Health. Strategic Master Plan for the Neglected Tropical Diseases Control Program July 2021–June 2026 Tanzania Mainland; Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2021; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Materu, G.S.; Nzalawahe, J.; Sengupta, M.E.; Stensgaard, A.-S.; Katakweba, A.; Vennervald, B.J.; Kinung’hi, S. Prevalence, Distribution and Risk Factors for Trematode Infections in Domesticated Ruminants in the Lake Victoria and Southern Highland Ecological Zones of Tanzania: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazigo, H.D.; Uisso, C.; Kazyoba, P.; Nshala, A.; Mwingira, U.J. Prevalence, Infection Intensity and Geographical Distribution of Schistosomiasis among Pre-School and School Aged Children in Villages Surrounding Lake Nyasa, Tanzania. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odiere, M. R.; et al. High prevalence of schistosomiasis in Mbita and its adjacent islands of Lake Victoria, western Kenya. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesbrough, M. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 191–220. ISBN 978-0-511-34935-5. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Basic Laboratory Methods in Medical Parasitology. (World Health Organization, 1991).

- Uga, S.; Tanaka, K.; Iwamoto, N. Evaluation and modification of the formalin-ether sedimentation technique. Trop Biomed. 2010, 177–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sato, C.; Rai, S.K.; Uga, S. Re-evaluation of the formalin-ether sedimentation method for the improvement of parasite egg recovery efficiency. Nepal Med Coll J 2014, 16, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2002, 912.

- Montresor, A.; Crompton, D.W.T.; Hall, A.; Bundy, D.A.P.; Savioli, L. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis and Schistosomiasis at Community Level (World Health Organization,

Geneva, 1998).

- World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis: Progress Report 2001–2011 and Strategic Plan 2012–2020. 2010, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/78074.

- Mueller, A.; Fuss, A.; Ziegler, U.; Kaatano, G.M.; Mazigo, H.D. Intestinal Schistosomiasis of Ijinga Island, North-Western Tanzania: Prevalence, Intensity of Infection, Hepatosplenic Morbidities and Their Associated Factors. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, T.; et al. Geographical and behavioral risks associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection in an area of complex transmission. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, A.; Fuss, A.; Mazigo, H.D.; Ruganuza, D.; Müller, A. Prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni, soil-transmitted helminths intestinal protozoa in orphans and street children in Mwanza city, Northern Tanzania. Infection 2023, 51, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngasala, B.; Jumaa, H.; Mwaiswelo, R.O. The usefulness of indirect diagnostic tests for Schistosoma haematobium infection after repeated rounds of mass treatment with praziquantel in Mpwapwa and Chakechake districts in Tanzania. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 90, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handzel, T.; et al. Geographic distribution of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in Western Kenya: Implications for anthelminthic mass treatment. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 69, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odiere, M. R.; et al. Geographical distribution of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths among school children in informal settlements in Kisumu City, Western Kenya. Parasitology 2011, 138, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, S.; et al. Urogenital schistosomiasis elimination in Zanzibar: accuracy of urine filtration and haematuria reagent strips for diagnosing light intensity Schistosoma haematobium infections. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, L.C.; Lupenza, E.T.; Zacharia, A.; Ngasala, B.E. Urogenital schistosomiasis prevalence, knowledge, practices and compliance to MDA among school-age children in an endemic district, southern East Tanzania. Parasite Epidemiology and Control 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkya, T.E. Prevalence and risk factors associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection among school pupils in an area receiving annual mass drug administration with praziquantel: a case study of Morogoro municipality, Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research 2023, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleta, S.; Alemu, A.; Getie, S.; Mekonnen, Z.; Geleta, B.E. Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among the abobo primary school children in Gambella Regional State, southwestern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senghor, B.; Diallo, A.; Sylla, S.N.; Doucour’e, S.; Ndiath, M.O.; Gaayeb, L.; Djuikwo-Teukeng, F.F.; et al. , Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among school children in the district of Niakhar, region of Fatick, Senegal. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazigo, H. D.; et al. Co-infections with Plasmodium falciparum, Schistosoma mansoni and intestinal helminths among school-children in endemic areas of northwestern Tanzania. Parasit. Vectors 2010, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruganuza, D. M.; Mazigo, H. D.; Waihenya, R.; Morona, D.; Mkoji, G. M. Schistosoma mansoni among pre-school children in Musozi village, Ukerewe Island, North-Western-Tanzania: prevalence and associated risk factors. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnkugwe, R.H.; Minzi, O.S.; Kinung’hi, S.M.; Kamuhabwa, A.A.; Aklillu, E. Prevalence and Correlates of Intestinal Schistosomiasis Infection among School-Aged Children in North-Western Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, R.; Farghaly, A.; El Masry, A.; G. , El-Sayed, M. K.; Hussein, M. H. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Egypt: Patterns of Schistosoma mansoni infection and morbidity in Kafer El-Sheikh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000, 62, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabetereine, N.B.; et al. Adult resistance to Schistosoma mansoni: Age-dependence of re-infection remains in communities with diverse exposure patterns. Parasitology 1999, 118, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukambagire, A. S.; Mchaile, D.; N and Nyindo, M. Diagnosis of human fascioliasis in Arusha region, northern Tanzania by microscopy and clinical manifestations in patients. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015, 15, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugho, E.A.; Nagagi, Y.P.; Lyaruu, L.J.; Mosha, V.V.; Senyael, N.; Mwita, M.M.; Mabahi, R.W.; Temba, V.M.; Hebel, M.; Nyati, M.; et al. Inverted Patterns of Schistosomiasis and Fascioliasis and Risk Factors Among Humans and Livestock in Northern Tanzania. Pathogens 2025, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, J.G.; Gonzalez, C.; Curtale, F.; Muñoz-Antoli, C.; Valero, M.A.; Bargues, M. D et al. Hyperendemic fascioliasis associated with schistosomiasis in villages in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 69, 429–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quy, T.; Yeatman, H.; Flood, V.M.; Chuong, N.; Tuan, B. Prevalence and risks of fascioliasis among adult cohorts in Binh Dinh and Quang Ngai provinces- central Viet Nam. VJPH. 2015, 2015. 3, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cabada, M.M.; Goodrich, M.R.; Graham, B.; Villanueva-Meyer, P.G.; Deichsel, E.L.; Lopez, M.; et al. Prevalence of intestinal helminths, anemia, and malnutrition in Paucartambo, Peru. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015, 37, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Valero, M.A.; Perez-Crespo, I.; Periago, M.V.; Khoubbane, M.; Mas-Coma, S. Fluke Egg Characteristics for the Diagnosis of Human and Animal Fascioliasis by Fasciola Hepatica and F. gigantica. Acta Trop. 2009, 111, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyindo, M.; Lukambagire, A.H. Fascioliasis: An Ongoing Zoonotic Trematode Infection. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 786195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas-Coma, S. Human fascioliasis: epidemiological patterns in human endemic areas of South America, Africa and Asia. Southeast Asian J. Trop Med Public Health. 2004, 35 (Suppl 1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).