* Corresponding authors. E-mail: qintian@icdc.cn (Tian Qin)

1. Introduction

Ticks, being the second most significant arthropod vectors after mosquitoes, surpass other hematophagous species in their ability to transmit a diverse range of pathogens. They have been documented to carry 83 viral species, 31 bacterial species, and 32 protozoan species (Dantas-Torres et al., 2012). Tick bites can cause human diseases, most of which are important natural infectious diseases and zoonotic diseases, such as fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, tick-borne typhus, forest encephalitis, tick-borne hemorrhagic fever, Q fever, Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and Bartonella infection. Annually, tick-borne pathogens cause more than 100,000 cases of human disease globally (de la Fuente et al., 2008).

Rhipicephalus microplus, formerly known as Boophilus microplus, belongs to Ixodidae family. Its life cycle consists of four stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult. Each stage requires blood meal to undergo molting to complete the metamorphosis process (Deng and Jiang, 1992). R. microplus exhibites a single-host life cycle and predominantly infests bovine animals, earning it the common name “bovine lice” in China. Over the past few decades, it has been widely regarded as the most economically significant ectoparasite affecting cattle worldwide (Schetters et al., 2016), particularly in tropical and subtropical regions (Almazán et al., 2012). It can carry and transmit a wide range of human and animal pathogens. Some of these pathogens include severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, Babesia bovis, Ehrlichia ruminantium, Ehrlichia canis, and spotted fever group Rickettsia, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Anaplasma marginale, and Anaplasma capra, and is therefore considered to be an important vector of infectious diseases that threaten human and animal health (Zhao et al., 2021). Furthermore, about 80% of the world’s cattle population is affected by ticks and tick-borne pathogens, which causes severe economic losses due to the costs associated with parasite control, as well as due to reduced fertility, body weight, and milk production (Narladkar, 2018;Valente et al., 2024).

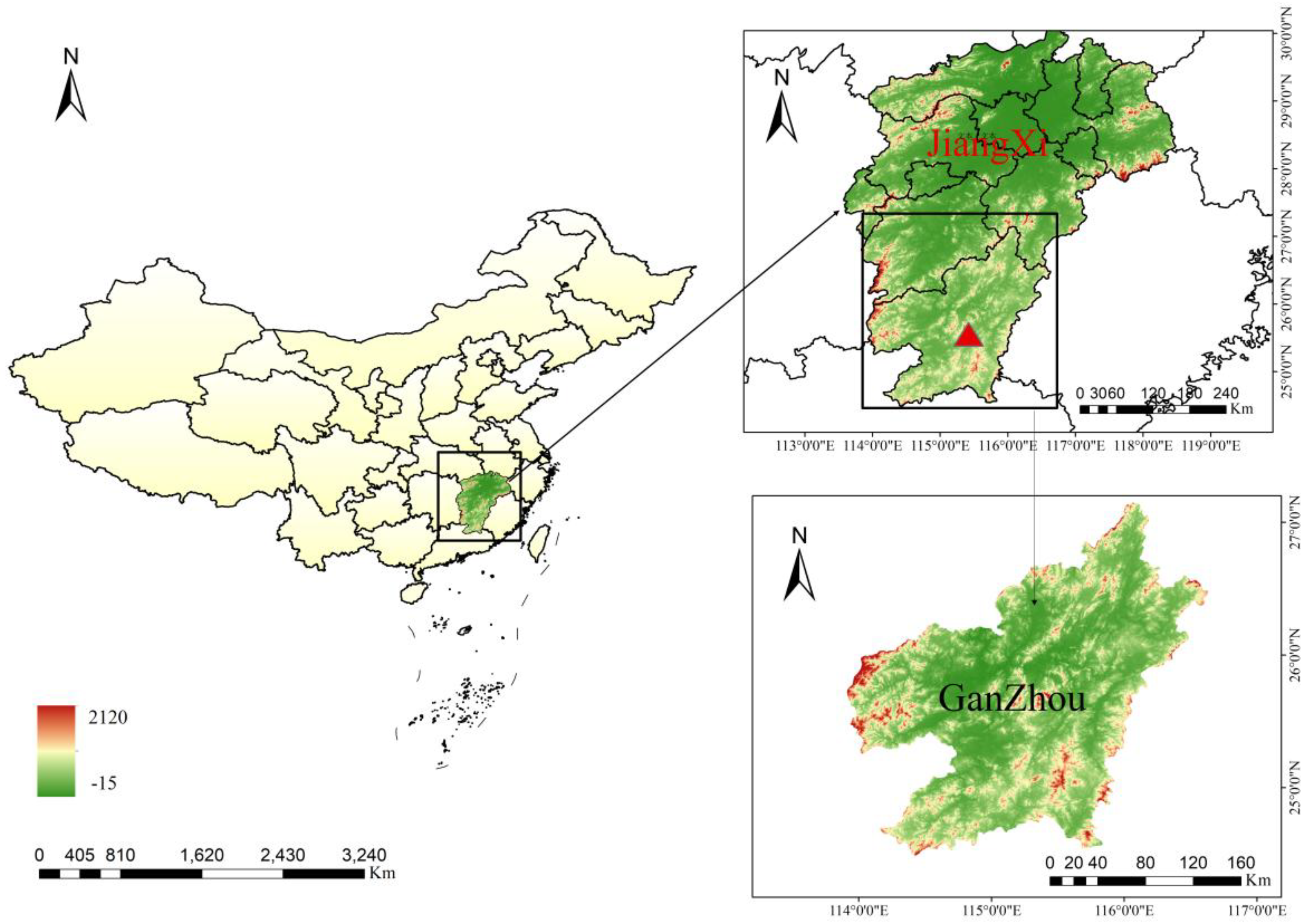

Rickettsiales bacteria, including the spotted fever group of Rickettsia (SFGR), Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia, are recognized as important tick-borne pathogens (Rochlin and Toledo, 2020). Importantly, as urbanization progresses, the risk of human and animal contact with tick species gradually increases (Piotrowski and Rymaszewska, 2020). Thus, it is crucial to enhancing the surveillance of tick-borne pathogens. Ganzhou city is located in the south of Jiangxi Province, located at the southern edge of the subtropical zone in the middle subtropics, and belongs to the subtropical hilly and mountainous area with a humid monsoon climate, which provides suitable habitats for the survival and reproduction of ticks (Chen et al., 2010). Its terrain is mainly composed of mountains, hills, and basins. Livestock often become heavily infested with ticks when they graze in the fields. Therefore, this study performed molecular biological detection on ticks collected from cattle in Ganzhou city during the period from 2022 to 2023, aiming to understand the diversity of Rickettsiales bacteria carried by ticks in this area, and provide scientific basis for the prevention and control of tick-borne Rickettsial diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tick Collection and Identification

From March to September in 2022, a total of 392 ticks were collected from 30 cattle in Ganzhou, Jiangxi Province (latitude 24°29′N - 27°09′N, longitude 113°54′E - 116°38′E). This included 8 yellow cattle and 22 dairy cows. All ticks were first identified basedon morphological differences in their capitulum and body by atrained technician using light microscopy (Azmat et al., 2018). The tick species were further confirmed by PCR amplification of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene (Cao et al., 2000). All ticks were stored at −80°C prior to DNA extraction.

2.2. DNA Extraction

First, the ticks were cleaned successively with benzalkonium bromide at the working concentration, 75% ethanol, and Sucrose-Phosphate-Glutamate (SPG). Subsequently, each tick was placed into a centrifuge tube containing 200 μL of SPG, and homogenization was achieved using a grinding instrument. Finally, DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All DNA samples were stored at -20℃.

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction

Nested and semi-nested PCR were used to detect pathogens, namely

Rickettsia,

Anaplasma, and

Ehrlichia.

Rickettsia spp. was detected by nested PCR as described previously using primers targeting a conserved region of the

16S rRNA gene, resulting in a PCR product of approximately 900 bp (Guo et al., 2016). The DNA samples were also screened for Anaplasmataceae bacteria as described previously, amplifying a 500 bp fragment of the

16S rRNA gene (Jafar Bekloo et al., 2018). The primers were custom-synthesized by Beijing DIA-UP Biotechnology Co., LTD. The target fragment was verified by agar-gel electrophoresis and further confirmed by Sanger sequencing at Tianyi Huiyuan Biotechnology Company (Beijing, China). The obtained

16S rRNA gene sequences were compared with reference sequences in the GenBank Database for initial species determination. To precisely determine the bacterial species and analyze the genetic diversity of detected strains, nearly complete

16S rRNA gene sequences (1000 bp), and partial sequences of

gltA (961 bp),

groEL(1021bp)and

ompA (700 bp) were obtained for representative

Rickettsia strains using primers described previously (Jafar Bekloo, et al., 2018). For

Anaplasma and

Ehrlichia, the

16S rRNA,

gltA, and

groEL genes were amplified using nested primers (Guo, et al., 2016;Yang et al., 2017;Jafar Bekloo, et al., 2018). The PCR products were subjected to sequencing in both directions. All sequences have been uploaded to the GenBank Database and the accession numbers are shown in

Table S1.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

The sequences were edited and assembled using the SeqMan software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA; SeqMan Pro 12.1.0). Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analyses were performed to compare with the sequences available in GenBank. Additionally, the neighbor - joining (NJ) method was adopted for multiple sequence alignments, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA 7.0. To evaluate the reliability of the results, 1000 bootstrap replications were carried out.

3. Results

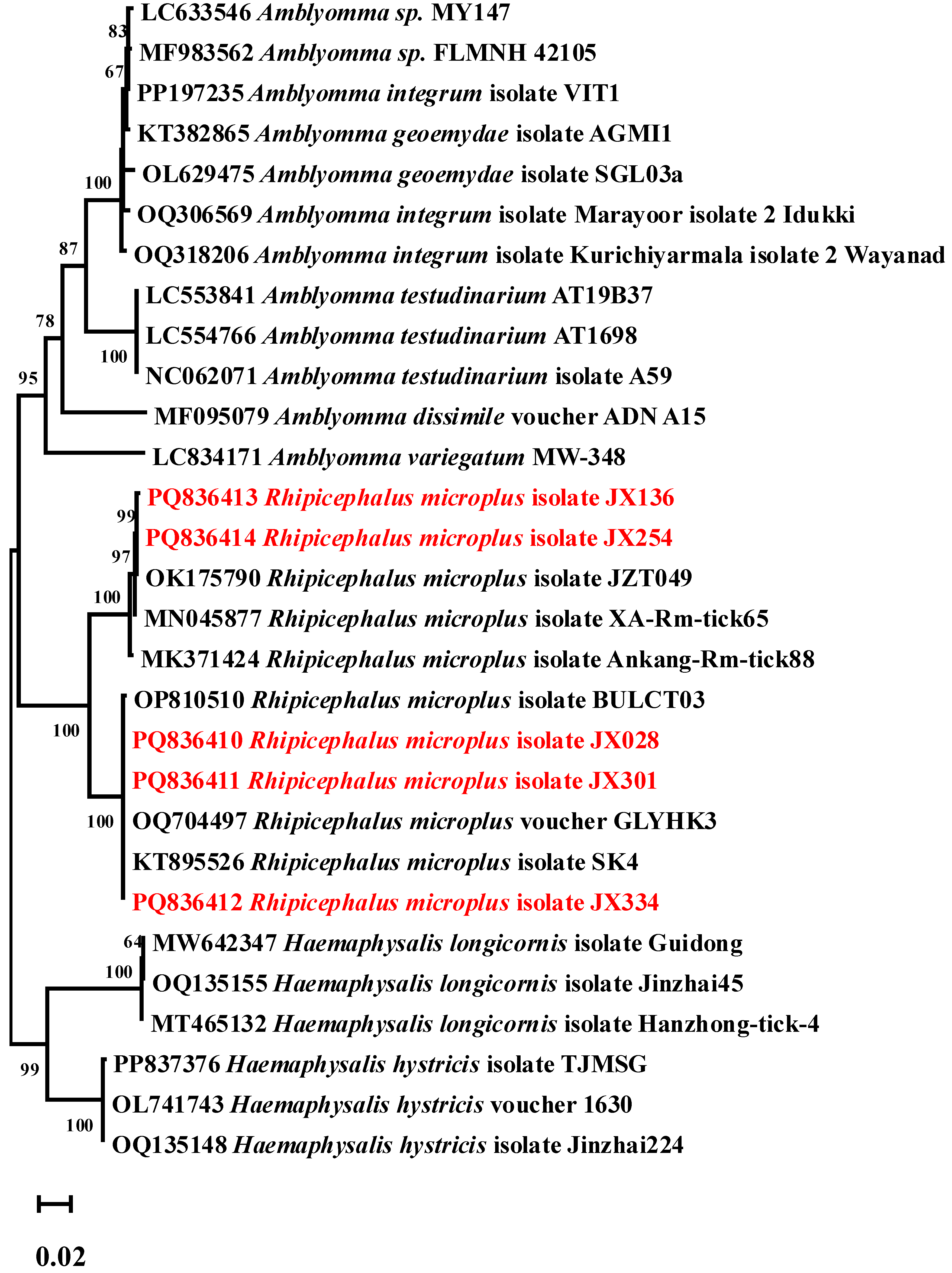

3.1. Tick Identification

A total of 392 ticks were collected in Ganzhou city, Jiangxi Province, from 2022 to 2023, including 97 nymphs (24.7%) and 295 adults (75.3%). Engorgement analysis indicated 257 semi-engorged (65.6%) and 135 fully engorged specimens (34.4%) (

Figure 1,

Table S2). All of them were collected from the body surface of cattle, including 8 yellow cattle and 22 dairy cows. Through morphological identification and molecular biological testing, it was determined that all the ticks belonged to the

Rhipicephalus microplus (100%, 392/392). The phylogenetic tree constructed based on the

COI gene sequence is shown in

Figure 2. The

R. microplus isolate JX136 and JX354 showed 100% identity (Query cover: 100%, E-value: 0.0) with previously reported

R. microplus (OK175790). The

R. microplus isolates JX028, JX301, and JX334 also clustered within the same branch in the phylogenetic tree (Query cover: 100%, E-value: 0.0). Five representative

COI gene sequences were selected and submitted to GenBank, with accession numbers PQ836410-PQ836414.

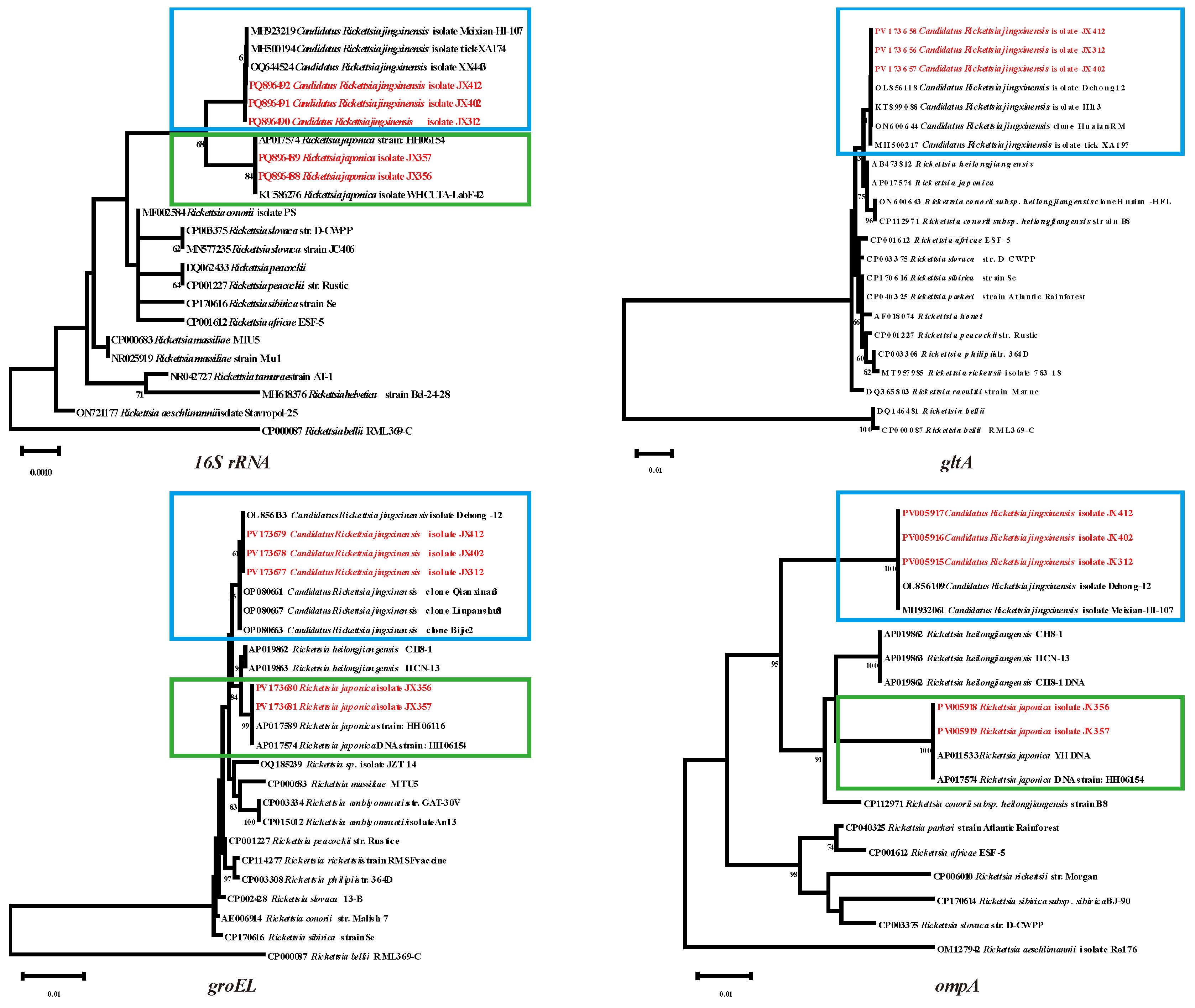

3.2. Rickettsia Bacteria Detected in Ticks

To gain a better understanding of the phylogenetic relationships between the

Rickettsia spp. in this study and those described previously, nucleotide alignments and analysis of

Rickettsia spp. were carried out based on the

16S rRNA, gltA, groEL and

ompA genes. In the

16S rRNA phylogenetic tree, the

Candidatus Rickettsia jingxinensis isolate JX312, JX402 and JX412 in the blue box exhibited 100% homology to the same branch

Ca. R. jingxinesis. Similarly,

Rickettsia japonica isolate JX356 and JX357 in the green boxes with known

R. japonica strains. The sequences of

gltA,

groEL, and

ompA for

Ca. R. jingxinensis were identical to those of

Ca. R. jingxinensis isolate Dehong (OL856118-120). Although

gltA fragments were not amplified in

R. japonica samples, the

groEL and

ompA gene fragments showed high homology (Query cover: 100%, E-value: 0.0) with the

R. japonica strain HH06154. Based on the comprehensive analysis of four genes, it was determined that two species of

Rickettsia were detected in this tick species, including

Ca. R. jingxinensis and

R. japonica. Their positive rates were 3.8% (15/392) and 9.2% (36/392), respectively (

Figure 3).

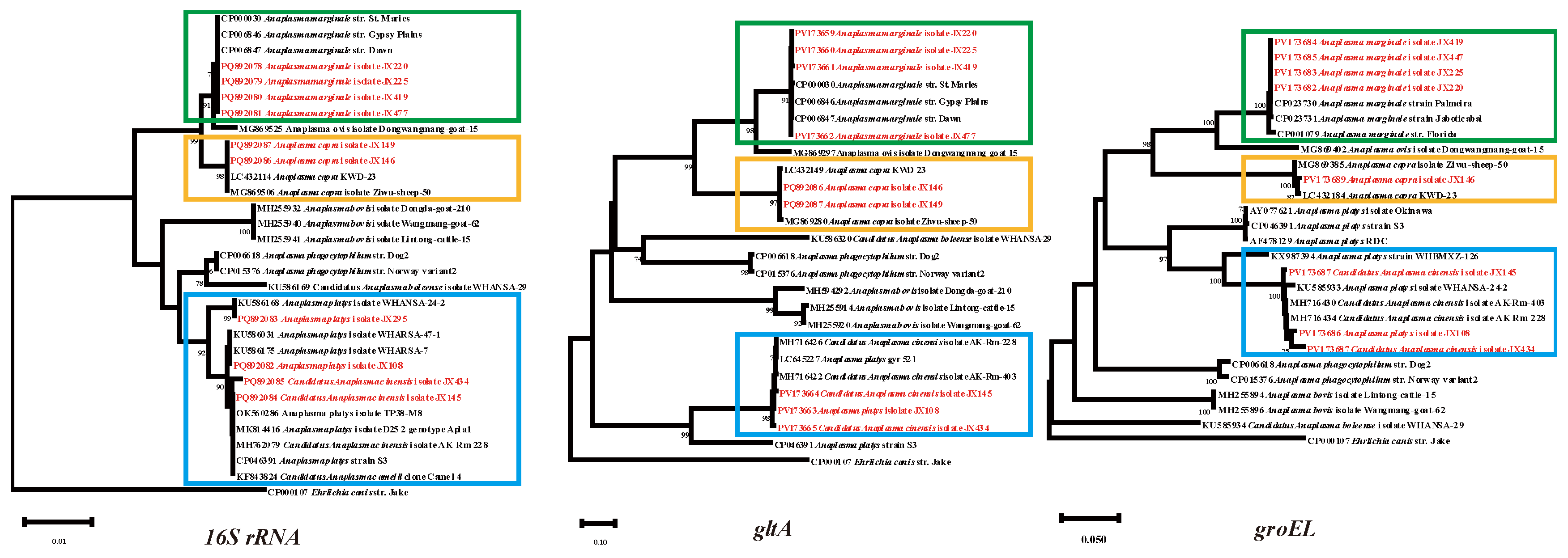

3.3. Anaplasma Bacteria Detected in Ticks

Four

Anaplasma species were identified in the ticks with a combined positive rate of 13.3% (52/392):

A. platys (0.5%, 2/392),

Ca. A. cinensis (0.5%, 2/392),

A. marginale (11.7%, 46/392), and

A. capra (0.5%, 2/392).

A. platys detected in the current study was classified into two genotypes in the phylogenetic tree based on the

16S rRNA genes. Isolates JX108 and JX295 were most closely related to WHARSA-47-1 and WHARSA-24-2 respectively. The sequences of the three genes shared 99.46–100% identity with

A. platys strains from other provinces of China. In the phylogenetic tree constructed based on

16srRNA,

gltA, and

groEL genes, although JX145 and JX434 clustered with both

A. platys and

Ca. A. cinensis, a detailed analysis revealed that three genes were together with

Ca. A. cinensis isolate AK-Rm-228 (MH762079, MH716426, MH716434), so they were identified as

Ca. A. cinensis. As a widely - distributed animal pathogen,

A. marginale shared 99.87 - 100% homology with other

A. marginale strains on the same branch of the phylogenetic tree. Its prevalence was the highest among the

Anaplasma species detected, reaching 11.7%, which accounted for 88% of the total positive rate for

Anaplasma. One group of

A. capra was closest to

A. capra KWD-23 (LC432184), with 99.85-100% identity according to the

16S rRNA,

gltA, and

groEL (

Figure 4).

3.4. Ehrlichia Bacteria Detected in Ticks

Of the 392 ticks screened in Ganzhou city, 70 (17.9%) tested positive for

Ehrlichia including two species:

E. minasensis and

Ehrlichia sp. The

16S rRNA,

gltA, and

groEL sequences of

E. minasensis strains (

E. minasensis isolate JX206 and

E. minasensis isolate JX424) showed 100% identity with

E. minasensis isolate JZT254 (from Jinzhai County, Anhui Province). The

16S rRNA sequences of the randomly selected

Ehrlichia sp. strains had three different nucleotides and they were divided into different clades in the phylogenetic tree. The group in which

Ehrlichia sp. isolate JX104 was located exhibited 99.82% - 100% homology with other

Ehrlichia in the same branch. Its

16S rRNA,

gltA, and

groEL sequences showed 99.1%, 100%, and 100% homology to

Ehrlichia sp. strain WHBMXZ-43, respectively. The

16S rRNA gene sequences of the other group of

Ehrlichia sp. (

Ehrlichia sp. isolate JX312 and JX319) shared 99.91% and 99.65% homology with

Ehrlichia sp. BL157-4 and

Ehrlichia sp. ERm58, respectively. The

gltA sequences were closely related to

Ehrlichia sp. ERm58 with 94.50% homology. The

groEL gene sequences of

Ehrlichia sp. isolate JX319 were 100% identical to those of

Ehrlichia sp. isolate JZT43 (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Rhipicephalus microplus is distributed in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and East and South Africa (Kamani et al., 2017). It has been found that R. microplus has been reported and recorded in a total of 56 countries worldwide, of which 463 coordinates have been reported in China (Xiao, 2022). Studies have shown that there are 18 species of ticks in Jiangxi Province, which belong to 2 families and 6 genera (Tian et al., 2023). As an important vector organism, the study on the R. microplus in Ganzhou City, Jiangxi Province is not comprehensive, and its pathogen spectrum needs to be further studied. In this study, 2 Rickettsia, 4 Anaplasma, and 2 Ehrlichia species in total were detected and characterized in Ganzhou city, Jiangxi Province.

The detection of Rickettsia in ticks has important implications not only for identifying infected ticks, but also for assessing the risk of transmission to humans (Philippe Parola, 2001). In the present study, two Rickettsia spp. (R. japonica and Ca. R. jingxinesis) were detected in the ticks. R. japonica, the causative agent of Japanese spotted fever (JSF), is transmitted by the bite of arthropods (mainly ticks) and was first diagnosed in Japan in 1984 (Mahara et al., 1985). In recent years, the geographical distribution of R. japonica in ticks in China has been expanding, which indicates an increased risk of disease to human health. In addition, delays in JSF diagnosis and treatment can lead to death (Teng et al., 2023). In this study, we obtained 16S rRNA, groEL and ompA gene fragments of R. japonica, which were 100% homologous to the existing gene fragments in the database, revealing the potential risk of JSF to the local human. Ca. R. jingxinensis, named after its geographical origin, is widespread in China (Liu et al., 2016). The Ca.R. jingxinensis variant R. sp. XY118 has been found in tick-bitten patients, which suggests that Ca.R. jingxinensis is a potential human pathogen and provides a basis for monitoring its infection in humans (Li et al., 2020).

Anaplasmosis is a priority disease in the Terrestrial Animal Health Code of the World Organization for Animal Health(

https://www.defesa.agricultura.sp.gov.br/informativo/defesa-agrosp-no-016-novembro20/organizacao-mundial-de-saude-animal/). In the present study, four bacterial species belonging to the genus

Anaplasma were identified:

A. platys,

A. marginale,

A. capra and Ca. A. cinensis.

A. platys was first described as a canine pathogen that infects the host’s platelets, and was identified as the etiological agent for canine cyclic thrombocytopenia, affecting cats and some ruminants such as cattle, goats, camels, buffalo, and red deer (Harvey et al., 1978). Although the

R. sanguineus tick is thought to be the primary vector of

A. platys transmission, its DNA has also been detected in other tick species. In 2013, the first case obtained DNA fragment of

A. platys from a blood sample of a female veterinarian (Maggi et al., 2013). In 2014, another study reported two case reports of

A. platys detection in two women from Venezuela (Arraga-Alvarado et al., 2014).

A. marginale is widely distributed throughout the world and is an important animal pathogen that can cause bovine anaplasmosis, which is characterized by fever, anemia, jaundice, abortion, wasting and other symptoms, transplacental routes have also been reported (Kocan et al., 2004;Aubry and Geale, 2011;Garcia et al., 2022). In our study, the positive rate of

A. marginale was as high as 11.7%, which is worthy of concern.

A. capra has attracted widespread concern since it was first identified in goats and patients in China in 2015 (Li et al., 2015). And there are model predictions that this zoonotic pathogen could spread to wider areas, so its public health and veterinary implications warrant further study (Lin et al., 2023).

Ca. A. cinensis is a new unclassified

Anaplasma species genetically related to

A. platys, which was first identified in ticks in southeastern Shaanxi Province (Guo et al., 2019). The epidemiology of anaplasmosis in humans caused by these two

Anaplasma species should be evaluated in future studies.

The genus Ehrlichia belongs to the family Anaplasmataceae and consists of six recognized species of bacteria: E. canis, E. chaffeensis, E. muris, E. ewingii, E. ruminantium, and E. minasensis (Dumler et al., 2001;Aguiar et al., 2019). Ehrlichia minasensis, an Ehrlichia closely related to E. canis, was initially reported in Canada and Brazil (Gajadhar et al., 2010;Zweygarth et al., 2013). This bacterium has now been reported in Pakistan, Malaysia, China, Ethiopia, South Africa, and the Mediterranean island of Corsica, suggesting that E. minasensis has a wide geographical distribution (Cabezas-Cruz et al., 2019). In this study, the positive rate of E. minasensis was 1.5%, suggesting that E. minasensis is circulating among cattle in Ganzhou city. Sero-epidemiological investigation of local cattle is needed to understand the prevalence of E. minasensis in infected animals. In the present study, uncultured strains belonging to two Ehrlichia spp. (Ehrlichia sp. JX104, JX148, JX162, JX194, and JX196 and Ehrlichia sp. JX312, and JX319) were detected in this study. Ehrlichia sp. JX104, JX148, JX162, JX194, and JX196 were more closely related to Ehrlichia sp. strain WHBMXZ-43 identified in R. microplus from Wuhan, China. Ehrlichia sp. JX312, and JX319 were clustered together with Ehrlichia sp. EmR58 found in African ticks. Despite the absence of documented clinical manifestations caused by these Ehrlichia strains in human populations, this study raises substantial concerns regarding potential zoonotic hazards, particularly given the expanding recognition of arthropod-borne infectious agents as emerging disease threats. Current epidemiological evidence corroborates that numerous microbial species initially classified as non-pathogenic have subsequently been implicated in human pathogenesis. This paradigm shift underscores the critical need for proactive assessment of microbial virulence factors, even when preliminary pathogenicity data remain inconclusive. Such dual-directional research holds particular significance for public health preparedness, given the accelerated geographic expansion of tick populations and their associated microbial communities under current climate change scenarios.

Rickettsia,

Anaplasma and

Ehrlichia were detected in

R. microplus in the study area, indicating a risk to livestock workers and farmers, especially in rural areas (

Table S3). In addition, it may be associated with economic losses and food security by affecting livestock. Therefore, understanding all aspects of these bacteria, such as their ecology, genetic diversity and pathogenicity, is essential to mitigate the associated risks locally.

There are also some limitations in our study. First of all, the host species involved in the sample was single, so it is necessary to expand the host species in subsequent studies. Second, a positive PCR test for the pathogen of the collected bovine parasitic ticks could not distinguish whether the DNA template of the pathogen came from an infected tick or cattle blood degraded in the tick intestine, and further investigation of tick-borne pathogens in local cattle and free ticks is still needed.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our study revealed a diversity of pathogenic Rickettsial species in R. microplus ticks from Jiangxi Province, suggesting a potential threat to humans and animals in China. Our results may contribute to the current understanding of the biodiversity of Rickettsiales bacteria circulating in this region.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 GenBank numbers of sequences obtained in this study. Table S2 Statistical table of developmental stage and blood-soaked state of ticks. Table S3 The positive rate and quantity of Rickettsiales bacteria detected in this study.

Author Contributions

Jia He: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Meng Yang: Investigation, Formal analysis. Tian Qin: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Zhongqiu Teng: Visualization, Methodology. Peng Wang: Investigation, Formal analysis. Junrong Liang: Resources, Conceptualization. Yusheng Zou: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wen Wang: Supervision, Investigation. Na Zhao: Formal analysis.

Data availability statement: All the sequence files are available from the NCBI database (the accession numbers are shown in

Table S1).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Laboratory of Intelligent Tracking and Forecasting for Infectious Diseases of China [grant numbers 2024NITFID504 and 2024NITFID402]; Youth Fund for Enhancing Capability of Infectious Disease Surveillance and Prevention [grant number No. 102393240020020000003].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguiar D.M., Araujo J.P., Jr., Nakazato L., Bard E., Cabezas-Cruz A. 2019. Complete Genome Sequence of an Ehrlichia minasensis Strain Isolated from Cattle. Microbiology resource announcements. 8(15). [CrossRef]

- Almazán C., Moreno-Cantú O., Moreno-Cid J.A., Galindo R.C., Canales M., Villar M., de la Fuente J. 2012. Control of tick infestations in cattle vaccinated with bacterial membranes containing surface-exposed tick protective antigens. Vaccine. 30(2), 265-272. [CrossRef]

- Arraga-Alvarado C.M., Qurollo B.A., Parra O.C., Berrueta M.A., Hegarty B.C., Breitschwerdt E.B. 2014. Case report: Molecular evidence of Anaplasma platys infection in two women from Venezuela. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 91(6), 1161-1165. [CrossRef]

- Aubry P., Geale D.W. 2011. A review of bovine anaplasmosis. Transbound Emerg Dis. 58(1), 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Azmat M., Ijaz M., Farooqi S.H., Ghaffar A., Ali A., Masud A., Saleem S., Rehman A., Ali M.M., Mehmood K., Khan A., Zhang H. 2018. Molecular epidemiology, associated risk factors, and phylogenetic analysis of anaplasmosis in camel. Microbial pathogenesis. 123(377-384. [CrossRef]

- Cabezas-Cruz A., Zweygarth E., Aguiar D.M. 2019. Ehrlichia minasensis, an old demon with a new name. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 10(4), 828-829. [CrossRef]

- Cao W.C., Zhao Q.M., Zhang P.H., Dumler J.S., Zhang X.T., Fang L.Q., Yang H. 2000. Granulocytic Ehrlichiae in Ixodes persulcatus ticks from an area in China where Lyme disease is endemic. Journal of clinical microbiology. 38(11), 4208-4210. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z., Yang X., Bu F., Yang X., Yang X., Liu J. 2010. Ticks (acari: ixodoidea: argasidae, ixodidae) of China. Exp Appl Acarol. 51(4), 393-404. [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Torres F., Chomel B.B., Otranto D. 2012. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a One Health perspective. Trends in parasitology. 28(10), 437-446. [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente J., Estrada-Pena A., Venzal J.M., Kocan K.M., Sonenshine D.E. 2008. Overview: Ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 13(6938-6946. [CrossRef]

- Deng G., Jiang Z. 1992. Economic Insects of China. Insect knowledge.

- Dumler J.S., Barbet A.F., Bekker C.P., Dasch G.A., Palmer G.H., Ray S.C., Rikihisa Y., Rurangirwa F.R. 2001. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and 'HGE agent' as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology. 51(Pt 6), 2145-2165. [CrossRef]

- Gajadhar A.A., Lobanov V., Scandrett W.B., Campbell J., Al-Adhami B. 2010. A novel Ehrlichia genotype detected in naturally infected cattle in North America. Veterinary parasitology. 173(3-4), 324-329. [CrossRef]

- Garcia A.B., Jusi M.M.G., Freschi C.R., Ramos I.A.S., Mendes N.S., Bressianini do Amaral R., Gonçalves L.R., André M.R., Machado R.Z. 2022. High genetic diversity and superinfection by Anaplasma marginale strains in naturally infected Angus beef cattle during a clinical anaplasmosis outbreak in southeastern Brazil. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases. 13(1), 101829. [CrossRef]

- Guo W.P., Tian J.H., Lin X.D., Ni X.B., Chen X.P., Liao Y., Yang S.Y., Dumler J.S., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y.Z. 2016. Extensive genetic diversity of Rickettsiales bacteria in multiple mosquito species. Scientific reports. 6(38770. [CrossRef]

- Guo W.P., Zhang B., Wang Y.H., Xu G., Wang X., Ni X., Zhou E.M. 2019. Molecular identification and characterization of Anaplasma capra and Anaplasma platys-like in Rhipicephalus microplus in Ankang, Northwest China. BMC infectious diseases. 19(1), 434. [CrossRef]

- Harvey J.W., Simpson C.F., Gaskin J.M. 1978. Cyclic thrombocytopenia induced by a Rickettsia-like agent in dogs. The Journal of infectious diseases. 137(2), 182-188. [CrossRef]

- Jafar Bekloo A., Ramzgouyan M.R., Shirian S., Faghihi F., Bakhshi H., Naseri F., Sedaghat M., Telmadarraiy Z. 2018. Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia spp. Isolated from Various Ticks in Southeastern and Northwestern Regions of Iran. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases (Larchmont, N.Y.). 18(5), 252-257. [CrossRef]

- Kamani J., Apanaskevich D.A., Gutiérrez R., Nachum-Biala Y., Baneth G., Harrus S. 2017. Morphological and molecular identification of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus in Nigeria, West Africa: a threat to livestock health. Experimental & Applied Acarology. 73(2), 283-296. [CrossRef]

- Kocan K.M., de la Fuente J., Blouin E.F., Garcia-Garcia J.C. 2004. Anaplasma marginale (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae): recent advances in defining host-pathogen adaptations of a tick-borne rickettsia. Parasitology. 129 Suppl(S285-300. [CrossRef]

- Li H., Li X.M., Du J., Zhang X.A., Cui N., Yang Z.D., Xue X.J., Zhang P.H., Cao W.C., Liu W. 2020. Candidatus Rickettsia xinyangensis as Cause of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiosis, Xinyang, China, 2015. Emerging infectious diseases. 26(5), 985-988. [CrossRef]

- Li H., Zheng Y.C., Ma L., Jia N., Jiang B.G., Jiang R.R., Huo Q.B., Wang Y.W., Liu H.B., Chu Y.L., Song Y.D., Yao N.N., Sun T., Zeng F.Y., Dumler J.S., Jiang J.F., Cao W.C. 2015. Human infection with a novel tick-borne Anaplasma species in China: a surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis. 15(6), 663-670. [CrossRef]

- Lin Z.T., Ye R.Z., Liu J.Y., Wang X.Y., Zhu W.J., Li Y.Y., Cui X.M., Cao W.C. 2023. Epidemiological and phylogenetic characteristics of emerging Anaplasma capra: A systematic review with modeling analysis. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 115(105510. [CrossRef]

- Liu H., Li Q., Zhang X., Li Z., Wang Z., Song M., Wei F., Wang S., Liu Q. 2016. Characterization of rickettsiae in ticks in northeastern China. Parasit Vectors. 9(1), 498. [CrossRef]

- Maggi R.G., Mascarelli P.E., Havenga L.N., Naidoo V., Breitschwerdt E.B. 2013. Co-infection with Anaplasma platys, Bartonella henselae and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in a veterinarian. Parasit Vectors. 6(103. [CrossRef]

- Mahara F., Koga K., Sawada S., Taniguchi T., Shigemi F., Suto T., Tsuboi Y., Ooya A., Koyama H., Uchiyama T., et al. 1985. The first report of the rickettsial infections of spotted fever group in Japan: three clinical cases. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 59(11), 1165-1171. [CrossRef]

- Narladkar B.W. 2018. Projected economic losses due to vector and vector-borne parasitic diseases in livestock of India and its significance in implementing the concept of integrated practices for vector management. Veterinary World. 11(2), 151-160. [CrossRef]

- Philippe Parola D.R. 2001. Ticks and Tickborne Bacterial Diseases in Humans: An Emerging Infectious Threat. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 32(6), 897–928.

- Piotrowski M., Rymaszewska A. 2020. Expansion of Tick-Borne Rickettsioses in the World. Microorganisms. 8(12), 1906. [CrossRef]

- Rochlin I., Toledo A. 2020. Emerging tick-borne pathogens of public health importance: a mini-review. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 69(6), 781-791. [CrossRef]

- Schetters T., Bishop R., Crampton M., Kopáček P., Lew-Tabor A., Maritz-Olivier C., Miller R., Mosqueda J., Patarroyo J., Rodriguez-Valle M., Scoles G.A., de la Fuente J. 2016. Cattle tick vaccine researchers join forces in CATVAC. Parasites & Vectors. 9(105. [CrossRef]

- Teng Z., Gong P., Wang W., Zhao N., Jin X., Sun X., Zhou H., Lu J., Lin X., Wen B., Kan B., Xu J., Qin T. 2023. Clinical Forms of Japanese Spotted Fever from Case-Series Study, Zigui County, Hubei Province, China, 2021. Emerging infectious diseases. 29(1), 202-206. [CrossRef]

- Tian J.H., Li K., Zhang S.Z., Xu Z.J., Wu H.X., Xu H.B., Lei C.L. 2023. Tick (Acari: Ixodoidea) fauna and zoogeographic division of Jiangxi Province, China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 14(2), 102099. [CrossRef]

- Valente D., Carolino N., Gomes J., Coelho A.C., Espadinha P., Pais J., Carolino I. 2024. A study of knowledge, attitudes, and practices on ticks and tick-borne diseases of cattle among breeders of two bovine Portuguese autochthonous breeds. Veterinary parasitology, regional studies and reports. 48(100989. [CrossRef]

- Xiao P. 2022. Analysis of spatial distribution and infectious pathogen prevalence of micro-fanehead ticks.

- Yang J., Liu Z., Niu Q., Liu J., Han R., Guan G., Hassan M.A., Liu G., Luo J., Yin H. 2017. A novel zoonotic Anaplasma species is prevalent in small ruminants: potential public health implications. Parasites & Vectors. 10(1), 264. [CrossRef]

- Zhao G.P., Wang Y.X., Fan Z.W., Ji Y., Liu M.J., Zhang W.H., Li X.L., Zhou S.X., Li H., Liang S., Liu W., Yang Y., Fang L.Q. 2021. Mapping ticks and tick-borne pathogens in China. Nat Commun. 12(1), 1075. [CrossRef]

- Zweygarth E., Schöl H., Lis K., Cabezas Cruz A., Thiel C., Silaghi C., Ribeiro M.F., Passos L.M. 2013. In vitro culture of a novel genotype of Ehrlichia sp. from Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis. 60 Suppl 2(86-92. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).