1. Introduction

Ticks and rodents are globally recognized as primary vectors and reservoirs for a wide spectrum of zoonotic pathogens, respectively, posing significant and escalating threats to both human and animal health [

1]. Understanding the specific pathogens circulating within local tick and rodent populations is fundamental for effective public health surveillance and disease prevention strategies.

Haemaphysalis longicornis, the Asian longhorned tick, is a vector of major medical and veterinary importance. Native to East Asia, including eastern China, Japan, and Korea, this species has demonstrated remarkable ecological adaptability, establishing invasive populations in Australia, New Zealand, and the eastern United States [

2,

3,

4]. Its capacity for parthenogenetic reproduction can lead to rapid population establishment and massive host infestations [

2].

H. longicornis is a competent vector for over 30 human pathogens, including multiple species of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia (SFGR), agents of anaplasmosis, and viruses such as

Dabie bandavirus (the causative agent of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome, SFTS) [

4]. In China, SFGR species like

Rickettsia japonica and

Rickettsia heilongjiangensis are significant causes of tick-borne rickettsioses [

5,

6].

Concurrently, wild rodents play a critical role in the enzootic cycles of numerous pathogens. The Daurian ground squirrel (

Spermophilus dauricus) is an ecologically significant, burrowing rodent species widely distributed across the grasslands and agricultural landscapes of northern China [

7]. It is a known host for ectoparasites and can be involved in the circulation of pathogens of major public health concern, such as

Yersinia pestis, the agent of plague [

8]. The unique life history of

S. dauricus, including hibernation and extensive burrowing, creates distinct ecological niches that may influence its exposure to and carriage of various microorganisms [

9].

While most pathogen surveillance programs focus on a single host or vector type, a comprehensive understanding of regional zoonotic risks requires a broader assessment of pathogen landscapes across different, ecologically important host species. Such parallel investigations, even if not conducted in the same immediate locality, can provide complementary insights into the distinct pathogen spectra maintained by different components of the ecosystem. Therefore, this study was designed with two parallel objectives: (1) to determine the prevalence and genetic characteristics of SFGR and other selected pathogens in questing H. longicornis ticks from two geographically separate provinces, Liaoning (Northeast) and Anhui (East-Central China); and (2) to conduct targeted molecular screening for pathogens in S. dauricus rodents from Heilongjiang Province, a key area of their distribution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

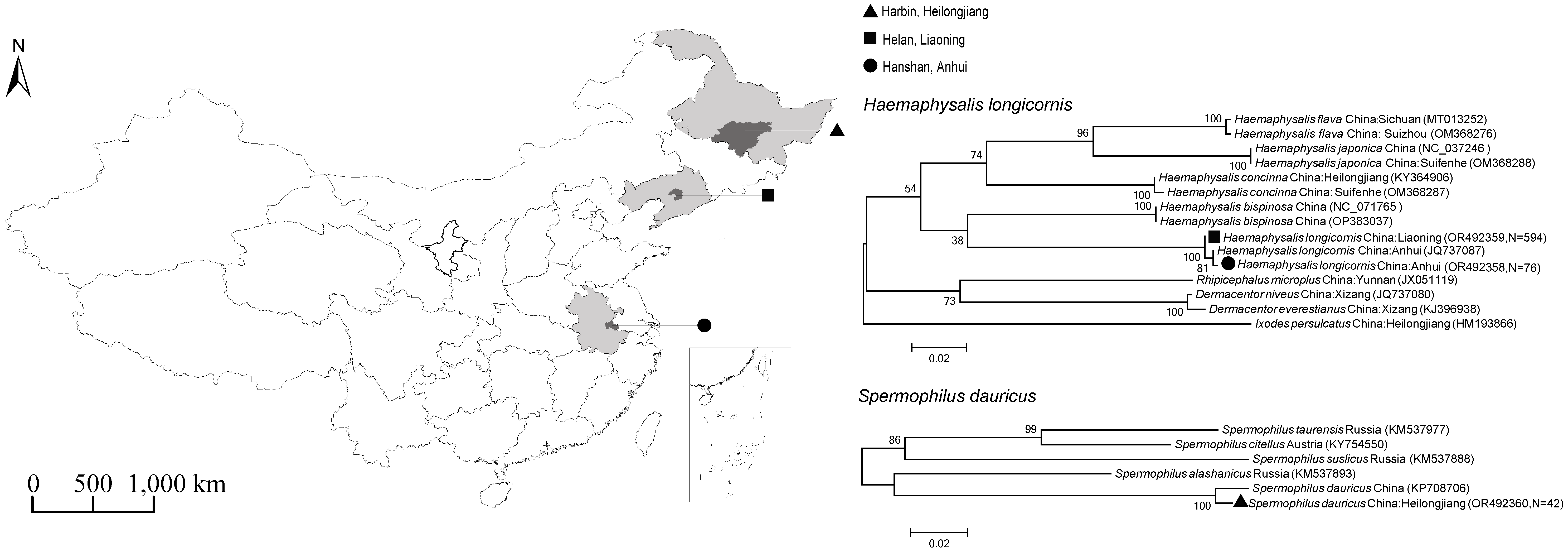

Questing ticks were collected from vegetation by flagging with a 1-m² corduroy cloth in woodland and grassland habitats in Helan Town, Liaoning Province (June 2021) and Hanshan County, Anhui Province (August 2022). In parallel, wild rodents were captured using traps placed near burrow entrances in the suburbs of Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province (June 2021). Geographic coordinates and habitat characteristics of all collection sites were recorded (

Figure 1). All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

2.2. Host Species Identification

All ticks and rodents were first identified to the species level based on morphological keys. To confirm morphological identification, DNA was extracted from a representative subset of ticks and all rodent liver samples, and the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (

COI) gene was amplified by nested PCR and sequenced, using primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 [

10].

2.3. Sample Processing and Pooling Strategy

A total of 1,004 ticks were processed. To optimize detection sensitivity for low-prevalence pathogens, a pooling strategy was employed. Questing adult ticks (n=503) were processed individually (503 pools). Questing nymphs (n=501) were combined into pools of up to three individuals, resulting in 167 nymphal pools. In total, 670 tick pools were analyzed. For rodents (n=42), liver tissue was aseptically dissected and used for subsequent analyses.

2.4. Tick Surface Decontamination and Homogenization

Prior to homogenization, individual ticks or tick pools were surface-sterilized to minimize contamination from external microbes. Each sample was washed sequentially by vortexing in 70% ethanol for 30 seconds, followed by 1% sodium hypochlorite for 30 seconds, and finally rinsed three times in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove residual disinfectants [

11,

12,

13]. Each sterilized tick pool or rodent liver sample was homogenized in 1 mL of sterile PBS using a TissueLyser II (QIAGEN, Germany). An aliquot of the homogenate (300 µl) was reserved for bacterial culture, while the remainder was used for nucleic acid extraction.

2.5. Nucleic Acid Extraction

Total DNA and RNA were co-extracted from 200 µl of each tissue homogenate using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Nucleic acids were eluted in a final volume of 120 µl (2 x 60 µl elutions) to maximize yield. The concentration and purity of the extracted nucleic acids were measured using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), and samples were stored at -40°C.

2.6. Molecular Detection of Pathogens

All nucleic acid samples were first screened for

Dabie bandavirus (SFTSV) using a one-step RT-PCR targeting the S segment [

14,

15]. For bacterial detection, samples were initially screened with universal primers targeting the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene [

16]. Samples positive for the 16S rRNA gene were then subjected to a series of nested PCR assays targeting specific genes for pathogens of interest (

Table 1). Specifically, tick samples were tested for

Rickettsia spp. (targeting

rrs,

gltA,

17kDa,

ompA,

ompB,

sca4) and

Coxiella-like endosymbionts (CLE) (targeting 16S rRNA,

groEL,

rpoB). Rodent samples were tested for

Legionella spp. (targeting 16S rRNA,

groEL,

mip). All PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on 1.0% agarose gels. Amplicons of the expected size were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) and sent for bidirectional Sanger sequencing.

2.7. Bacterial Culture and Identification

An aliquot of the tissue homogenate from each sample, was plated onto cysteine heart agar blood (CHAB) medium supplemented with antibiotics (colistin, amphotericin, lincomycin, methicillin, ampicillin) to select for specific bacterial groups. Plates were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and monitored daily. Individual colonies were isolated, sub-cultured for purity, and identified by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene amplified from colony material.

2.8. Phylogenetic and Data Analysis

Obtained nucleotide sequences were compared against the GenBank database using BLASTn. For phylogenetic inference, sequences were aligned with reference sequences using MUSCLE. Initial phylogenetic trees for individual genes were constructed using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA 11 software. To provide more robust phylogenetic placement for key pathogens, "supertrees" were constructed from concatenated sequences of multiple genes using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. This multi-gene approach increases the confidence of the phylogenetic inference. The pathogen prevalence in pooled tick samples was calculated as the Minimum Infection Rate (MIR), estimated using the formula: MIR=(Number of positive pools/Total number of ticks tested)×100.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection and Host Identification

A total of 1,004 ticks were collected from Liaoning (n=882) and Anhui (n=122) provinces, and 42 rodents were collected from Heilongjiang province (

Figure 1). Morphological and

COI gene sequence analysis confirmed that all ticks were

H. longicornis and all rodents were

S. dauricus. The obtained

COI sequences showed >99.9% identity to reference sequences [

17] in GenBank (

Figure 1).

3.2. Pathogen Prevalence

Molecular screening revealed the presence of several bacterial pathogens and endosymbionts, while no samples tested positive for Dabie bandavirus (SFTSV). The prevalence of all detected microbes is summarized in

Table 2. In

H. longicornis ticks, the overall MIR for SFGR was 1.4% (14/1,004). Geographically, the detected species differed:

Ca. R.

jingxinensis was found exclusively in Liaoning, with an MIR of 2.0% (12/594 positive pools), while

R. heilongjiangensis was found only in Anhui, with an MIR of 2.6% (2/76 positive pools).

Coxiella-like endosymbionts (CLE) were detected in both locations, with an overall MIR of 2.0% (20/1,004).

Notably, the MIR of CLE was substantially higher in Anhui (17.1%) compared to Liaoning (1.2%). Four tick pools were co-infected with both an SFGR species and CLE. In S. dauricus rodents, the most significant finding was the detection of L. pneumophila DNA in 2 of 42 (4.8%) liver samples from Heilongjiang.

3.3. Supplementary Culture-Based Findings

Bacterial culture from tissue homogenates yielded several isolates, primarily from the genera Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, and Bacillus from tick samples, and Staphylococcus and Enterococcus from rodent samples. These bacteria were identified via 16S rRNA sequencing of the isolates. As these organisms are common environmental microbes or commensals, and their detection via culture does not distinguish between internal colonization and potential residual surface contaminants surviving sterilization, their pathogenic significance in this context was not further investigated.

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of Detected Pathogens

Multi-gene phylogenetic analyses provided robust identification and revealed the genetic relationships of the detected pathogens.

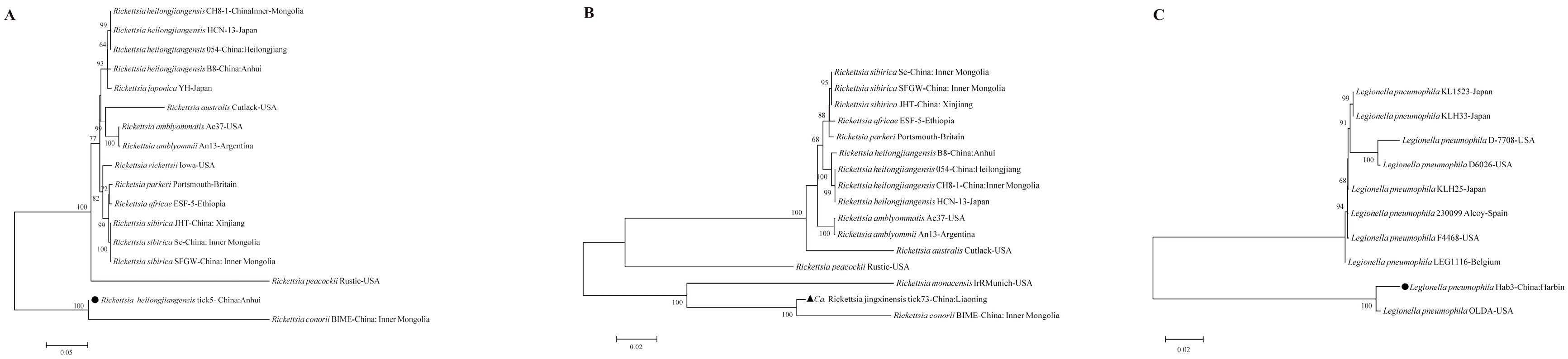

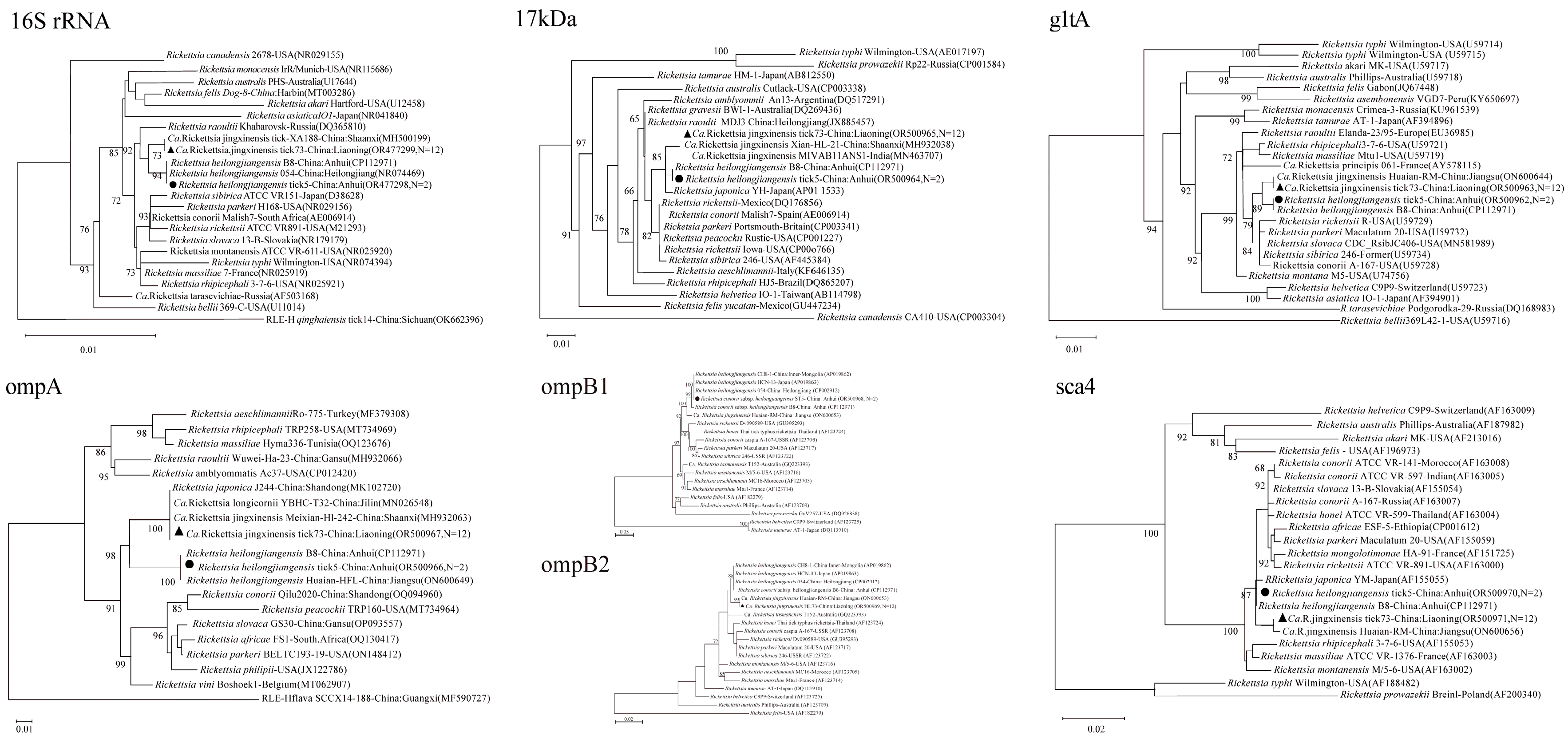

Rickettsia spp.: The six targeted genes (

rrs,

17kDa,

gltA,

ompA,

ompB,

sca4) from the

Ca. R.

jingxinensis isolates from Liaoning (represented by isolate tick73), showed high homology to strains previously reported from Shaanxi, Jilin, and Jiangsu provinces, forming a well-supported clade within the

R. japonica subgroup of SFGR (

Figure 2) [

25,

26]. The two

R. heilongjiangensis isolates from Anhui (represented by tick5) were genetically very close to each other. For five of their genes, they showed highest homology to strain B8, which was isolated from a human patient in Anhui [

27]. However, their

ompB gene sequences were 100% identical to strain 054 from Heilongjiang, suggesting potential genetic links between geographically distant populations (

Figure 2) [

28]. The ML supertree analysis, based on concatenated gene sequences, strongly supported these classifications, placing the Anhui isolate within the

R. heilongjiangensis cluster and the Liaoning isolate within a broader SFGR clade that includes

R. conorii (

Figure 5A,B).

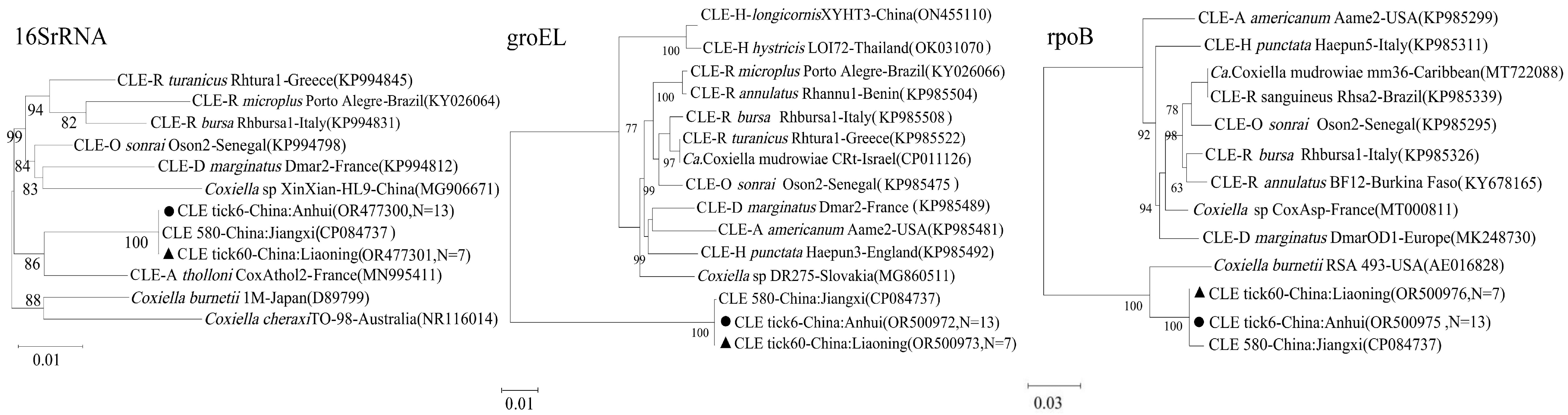

Coxiella-like Endosymbionts (CLE): The CLE sequences (16S rRNA,

groEL,

rpoB) from both Liaoning and Anhui were nearly identical to each other and clustered tightly with a CLE strain previously identified from Jiangxi province, indicating a conserved lineage of this endosymbiont in

H. longicornis across eastern China (

Figure 3).

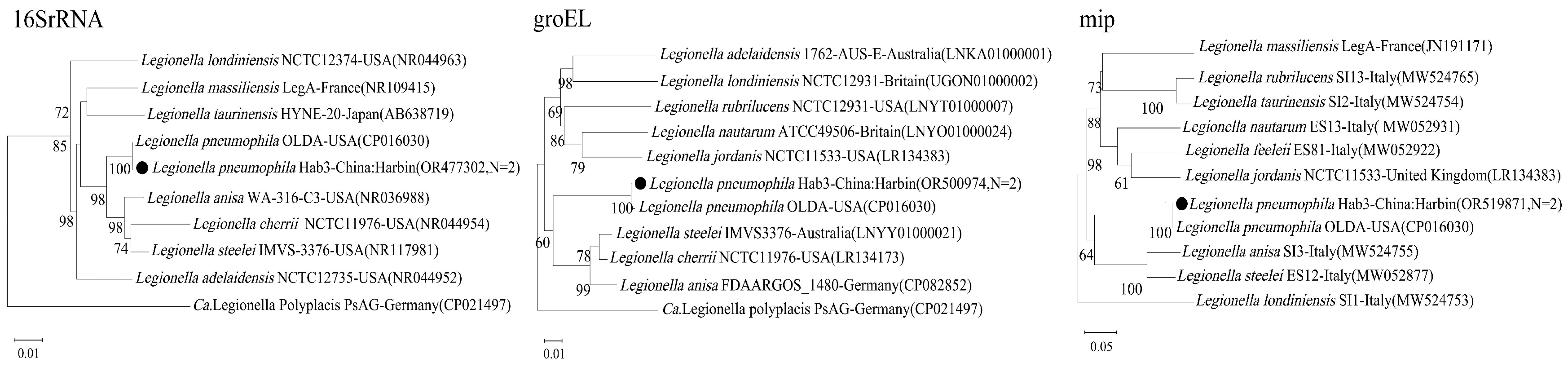

Legionella pneumophila: The sequences of the three target genes (16S rRNA,

groEL,

mip) from the two positive

S. dauricus samples (represented by Hab3) were highly homologous to the reference strain OLDA, a well-characterized human clinical isolate from the USA (

Figure 4). The

mip gene, a key virulence factor, showed 100% nucleotide identity. The concatenated gene supertree analysis confirmed this relationship with very high confidence (100% bootstrap support), underscoring the potential pathogenic nature of the strain detected in the ground squirrels (

Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees based on the nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA, groEL and mip genes of Legionella pneumophila. Bootstrap values >60% based on 1000 replicates are shown at the nodes, using neighbor-joiningmethod. ● represents Legionella pneumophila detected in this study.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic trees based on the nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA, groEL and mip genes of Legionella pneumophila. Bootstrap values >60% based on 1000 replicates are shown at the nodes, using neighbor-joiningmethod. ● represents Legionella pneumophila detected in this study.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic supertrees based on the concatenated gene sequences of Rickettsia and Legionella pneumophila, respectively. A 16S rRNA+17kDa+gltA+ompA+ompB1+sca4 for Rickettsia. B 16S rRNA+17kDa+gltA+ompA+ompB2+sca4 for Rickettsia. C 16S rRNA+groEL+mip for L.pneumophila. Bootstrap values >60% based on 1000 replicates are shown at the nodes, using maximum likelihood method. ▲ and represents detected pathogens in this study.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic supertrees based on the concatenated gene sequences of Rickettsia and Legionella pneumophila, respectively. A 16S rRNA+17kDa+gltA+ompA+ompB1+sca4 for Rickettsia. B 16S rRNA+17kDa+gltA+ompA+ompB2+sca4 for Rickettsia. C 16S rRNA+groEL+mip for L.pneumophila. Bootstrap values >60% based on 1000 replicates are shown at the nodes, using maximum likelihood method. ▲ and represents detected pathogens in this study.

4. Discussion

This study employed a parallel surveillance approach, to provide a snapshot of the pathogen landscape in H. longicornis ticks and S. dauricus rodents from three distinct provinces in China. While the disconnected sampling design precludes direct inference on local transmission cycles between these specific hosts, it yields valuable, complementary data on the distinct pathogen profiles each host carries, thereby contributing to a broader regional risk assessment.

Our findings confirm the presence of at least two SFGR species circulating in

H. longicornis ticks in China, with a notable geographic separation:

Ca. R.

jingxinensis in Liaoning and

R. heilongjiangensis in Anhui.

Ca. R.

jingxinensis, first described in China in 2016, has since been reported in multiple provinces, and our multi-gene analysis supports its genetic linkage with strains from other regions like Shaanxi and Jiangsu [

25,

26]. Similarly, the detection of

R. heilongjiangensis in Anhui, a pathogen typically associated with northeastern China, and its genetic similarity to a local human patient isolate (strain B8) [

27], reinforces its endemicity and public health relevance in this eastern-central province.

The overall MIR of SFGR in questing

H. longicornis was low (1.4%). This is consistent with findings from other studies on free-living, unfed ticks, where pathogen prevalence is often significantly lower than in ticks collected directly from animal hosts [

29]. For instance, a meta-analysis of SFGR in China reported an average prevalence of 11.5% in questing ticks, but this rate can be highly variable depending on location and tick species [

29]. In contrast, prevalence in ticks feeding on livestock can be extremely high, sometimes exceeding 70-90% [

26,

30]. Our low MIR provides an important baseline for the risk of human exposure from questing ticks in these specific environments, but it also highlights that host-associated ticks likely play a more significant role in amplifying and maintaining these pathogens.

The most striking and novel finding of this study is the detection of

L. pneumophila DNA in the liver tissue of

S. dauricus rodents.

L. pneumophila is an environmental bacterium, typically found in aquatic systems, soil, and biofilms, and is the primary cause of Legionnaires' disease in humans, transmitted via inhalation of contaminated aerosols [

31,

32,

33]. It is not considered a rodent-borne pathogen, and animals are generally thought to be accidental hosts with no established reservoir role [

34,

35,

36]. While experimental infections in rodents (mice, guinea pigs) can induce pneumonia-like disease, natural infections are rarely documented [

37,

38,

39].

The detection of

L. pneumophila in the liver, a deep organ, suggests a systemic infection rather than mere external contamination. We hypothesize that

S. dauricus, as a burrowing animal, has intimate and frequent contact with soil and moist subterranean environments, which are known habitats for

Legionella species [

31,

40]. The rodents likely acquired the bacteria from their environment, for example, through inhalation of contaminated dust within their burrows or ingestion of contaminated water. This pathway is plausible, as soil, particularly compost and potting mix, is a recognized source of

Legionella exposure for humans, especially for the species

L. longbeachae [

41,

42]. Although less common,

L. pneumophila has also been isolated from soil and compost materials [

43].

Crucially, the L. pneumophila strain we detected shares extremely high genetic identity with the human pathogenic strain OLDA, particularly in the virulence-associated mip gene. This indicates that the environmental strains circulating in the rodents' habitat are potentially virulent to humans. Therefore, our finding does not necessarily establish S. dauricus as a classic transmission reservoir for L. pneumophila. Instead, it positions these rodents as highly effective environmental sentinels or biological samplers. Their tissues could serve as a valuable and previously unrecognized matrix, for surveying the presence and pathogenic potential of environmental microbes like Legionella in terrestrial ecosystems, offering a new avenue for public health surveillance.

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the geographically disconnected sampling sites for ticks and rodents, prevent any conclusions about direct pathogen transmission between these host populations. Our framework is one of parallel, not integrated, surveillance. Second, the sample size for rodents (n=42) was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the prevalence data for L. pneumophila. Third, our detection of pathogens was based on nucleic acid amplification (DNA), which confirms the presence of the organism's genetic material but does not prove viability or infectivity, except in the case of the cultured bacteria. Finally, the use of nymph pooling for MIR calculation provides a cost-effective estimate of prevalence but is less precise than individual testing.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study provides a valuable, dual-focused snapshot of pathogen distribution in key host species in China. We provide updated, multi-gene-supported epidemiological data on the presence and genetic diversity of Ca. R. jingxinensis and R. heilongjiangensis in H. longicornis ticks. More significantly, we report the novel and unexpected detection of pathogenic L. pneumophila DNA in the liver of S. dauricus ground squirrels. This latter finding opens a new perspective on using wild rodents as sentinels for environmental pathogens, and highlights a previously unrecognized ecological niche for Legionella. Continued surveillance, ideally integrating sampling of vectors, reservoirs, and their environment, is warranted to fully understand regional zoonotic risks.

Funding

This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (Grant No. 7242188) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81874275).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, and were approved under the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project No. 81874275.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this study are available within the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations

Not applicable.

References

- Zhao, G.P.; Wang, Y.X.; Fan, Z.W.; Ji, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Li, X.L.; Zhou, S.X.; Li, H.; Liang, S.; et al. Mapping Ticks and Tick-Borne Pathogens in China. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, J.; Cui, X.; Jia, N.; Wei, J.; Xia, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; et al. Distribution of Haemaphysalis Longicornis and Associated Pathogens: Analysis of Pooled Data from a China Field Survey and Global Published Data. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e320–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.B.; Occi, J.; Bonilla, D.L.; Egizi, A.M.; Fonseca, D.M.; Mertins, J.W.; Backenson, B.P.; Bajwa, W.I.; Barbarin, A.M.; Bertone, M.A.; et al. Multistate Infestation with the Exotic Disease–Vector Tick Haemaphysalis Longicornis — United States, August 2017–September 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1310–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey, T.; Occi, J.L.; Robbins, R.G.; Egizi, A. Discovery of Haemaphysalis Longicornis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) Parasitizing a Sheep in New Jersey, United States. J. Med. Entomol. 2018, 55, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, Z.; Gong, P.; Wang, W.; Zhao, N.; Jin, X.; Sun, X.; Lu, J.; Lin, X.; Zhou, H.; Wen, B.; et al. The increasing prevalence of Japanese spotted fever in China: A dominant rickettsial threat. J. Infect. 2024, 90, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasama, K.; Fujita, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Ooka, T.; Gotoh, Y.; Ogura, Y.; Ando, S.; Hayashi, T. Genomic Features of Rickettsia Heilongjiangensis Revealed by Intraspecies Comparison and Detailed Comparison With Rickettsia Japonica. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, G.; Lin, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, A.; Wang, Y.; et al. The ecological study of Daurian ground squirrel (Spermophilus dauricus) in the agricultural ecosystem of northern China. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2012, 32, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.L.; Li, C.; Bai, Q.M.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Yang, H.Y.; He, J.Y.; Yan, Y.F.; Hai, R.; Yu, X.J. Plague surveillance in Spermophilus dauricus in Inner Mongolia, China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 13, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, H.V.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R. Seasonal restructuring of the ground squirrel gut microbiota over the annual hibernation cycle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 304, R33–R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Moutailler, S.; Popovici, I.; Devillers, E.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Eloit, M.; Ferte, H. Diversity of the tick-associated bacterial communities: impact of the sterilization method. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetruy, F.; Buysse, M.; Lejal, E.; Koadima, O.; Diancourt, L.; Santos, A.; Rose, T.; Durand, P.; Mediannikov, O.; Paddock, C.D.; et al. Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of the genus Amblyomma, vectors of Rickettsia species in the French Antilles. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprong, H.; Fonville, M.; van Leeuwen, A.D.; van der-Lelie, D.; van Wieren, S.E.; Gort, G.; Takken, W.; Heyman, P.; van-Vliet, A.J.H. Ticks and tick-borne pathogens in the expanding range of wild boar (Sus scrofa) in the Netherlands. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014, 14, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.-L.; Zhao, L.; Zhai, S.; Chi, Y.; Cui, F.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; et al. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome, Shandong Province, China, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, R.; Karaoz, U.; Volegova, M.; MacKichan, J.; Kato-Maeda, M.; Miller, S.; Lynch, K. Use of 16S rRNA Gene for Identification of a Broad Range of Clinically Relevant Bacterial Pathogens. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.Z.; Wu, S.Q.; Zhang, Y.N.; Chen, Y.; Feng, C.Y.; Yuan, X.F.; Jia, G.L.; Deng, J.H.; Wang, C.X.; Wang, Q.; et al. Assessment of four DNA fragments (COI, 16S rDNA, ITS2, 12S rDNA) for species identification of the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsoi, A.B.P.; Bitencourth, K.; De Oliveira, S.V.; Amorim, M.; Gazêta, G.S. Human Parasitism by Amblyomma Parkeri Ticks Infected with Candidatus Rickettsia Paranaensis, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2339–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, P.H.; Huang, Y.; Du, J.; Cui, N.; Yang, Z.D.; Tang, F.; Fu, F.X.; Li, X.M.; Cui, X.M.; et al. Isolation and Identification of Rickettsia Raoultii in Human Cases: A Surveillance Study in 3 Medical Centers in China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.C.; Chong, S.T.; Klein, T.A.; Jiang, J.; Richards, A.L.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, S.Y. Molecular Detection of Rickettsia Species in Ticks Collected from the Southwestern Provinces of the Republic of Korea. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; An, H.; Lee, J.S.; O’Guinn, M.L.; Kim, H.C.; Chong, S.T.; Zhang, Y.; Song, D.; Burrus, R.G.; Bao, Y.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Haemaphysalis Longicornis-Borne Rickettsiae, Republic of Korea and China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 1606–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, O.; Noël, V.; McCoy, K.D.; Bonazzi, M.; Sidi-Boumedine, K.; Morel, O.; Vavre, F.; Zenner, L.; Jourdain, E.; Durand, P.; et al. The Recent Evolution of a Maternally-Inherited Endosymbiont of Ticks Led to the Emergence of the Q Fever Pathogen, Coxiella Burnetii. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascale, M.R.; Salaris, S.; Mazzotta, M.; Girolamini, L.; Fregni Serpini, G.; Manni, L.; Grottola, A.; Cristino, S. New Insight Regarding Legionella Non-Pneumophila Species Identification: Comparison between the Traditional Mip Gene Classification Scheme and a Newly Proposed Scheme Targeting the rpoB Gene. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e01161-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaia, V.; Fry, N.K.; Harrison, T.G.; Peduzzi, R. Sequence-Based Typing of Legionella pneumophila Serogroup 1 Offers the Potential for True Portability in Legionellosis Outbreak Investigation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 2932–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhang, L.; Hu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Xin, Y.; Liu, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y. Genetic and Phylogenetic Characterization of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in Ticks from Jiangsu Province, Eastern China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 954785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, W.; Teng, Z.; Zhao, N.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, D.; Ma, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, J.; He, J.; et al. Molecular Detection of Rickettsiales and a Potential Novel Ehrlichia Species Closely Related to Ehrlichia Chaffeensis in Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from Shaanxi Province, China, in 2022 to 2023. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1331434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhang, L.; Hu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Xin, Y.; Liu, B.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y. Complete Genome Sequencing and Comparative Genomic Analyses of a New Spotted-Fever Rickettsia Heilongjiangensis Strain B8. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2153085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wen, B. Complete Genome Sequence of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 4284–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, W.; Jia, Z.; Wang, X.; Huo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Q. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Meng, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Tian, J.H.; Tang, G.P.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Li, M.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; et al. High Diversity and Prevalence of Rickettsial Agents in Rhipicephalus microplus Ticks from Livestock in Karst Landscapes of Southwest China. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowbotham, T.J. Preliminary Report on the Pathogenicity of Legionella Pneumophila for Freshwater and Soil Amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 1980, 33, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatt, S.P.; Parkinson, M.D.; Pace, E.; Hoffman, P.; Dolan, D.; Lauderdale, P.; Zajac, R.A.; Melcher, G.P. Nosocomial Legionnaires’ Disease: Aspiration as a Primary Mode of Disease Acquisition. Am. J. Med. 1993, 95, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, B.S. The molecular ecology of legionellae. Trends Microbiol. 1996, 4, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Kwaik, Y.; Gao, L.Y.; Stone, B.J.; Venkataraman, C.; Harb, O.S. Invasion of Protozoa by Legionella Pneumophila and Its Role in Bacterial Ecology and Pathogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 3127–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, B.S.; Benson, R.F.; Besser, R.E. Legionella and Legionnaires' Disease: 25 Years of Investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 506–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winn, W.C., Jr. Legionella and the Clinical Microbiologist. Infect. Control 1986, 7, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, A.; Fitzgeorge, R.B.; Broster, M.; Hambleton, P.; Dennis, P.J. Experimental Transmission of Legionnaires' Disease by Aerosol Infection in Guinea-Pigs. J. Hyg. 1978, 80, 389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, W.C., Jr.; Glavin, F.L.; Vogl, D.P.; Jones, G.L.; Beaty, H.N. The Pathology of Legionnaires' Disease. Fourteen Fatal Cases from the 1977 Outbreak in Vermont. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1979, 103, 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, D.W.; Tsai, T.R.; Orenstein, W.; Parkin, W.E.; Beecham, H.J.; Sharrar, R.G.; Harris, J.; Mallison, G.F.; Martin, S.M.; McDade, J.E.; et al. Legionnaires' Disease: Description of an Epidemic of Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1977, 297, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heijnsbergen, E.; Schalk, J.A.C.; Euser, S.M.; Brandsema, P.S.; den Boer, J.W.; de Roda Husman, A.M. Confirmed and Potential Sources of Legionella Reviewed. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4797–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Legionellosis Associated with Potting Soil---California, Oregon, and Washington, May--June 2000. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2000, 49, 777–778. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Health. Stay safe from legionnaires' disease when gardening. Available online: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/news/Pages/20221126_00.aspx (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Casati, S.; Gioria-Guscio, M.; Gaia, V.; Tonolla, M.; Peduzzi, R. Legionella spp. and Free-Living Amoebae in Composts from a Wide Variety of Sources. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).