Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

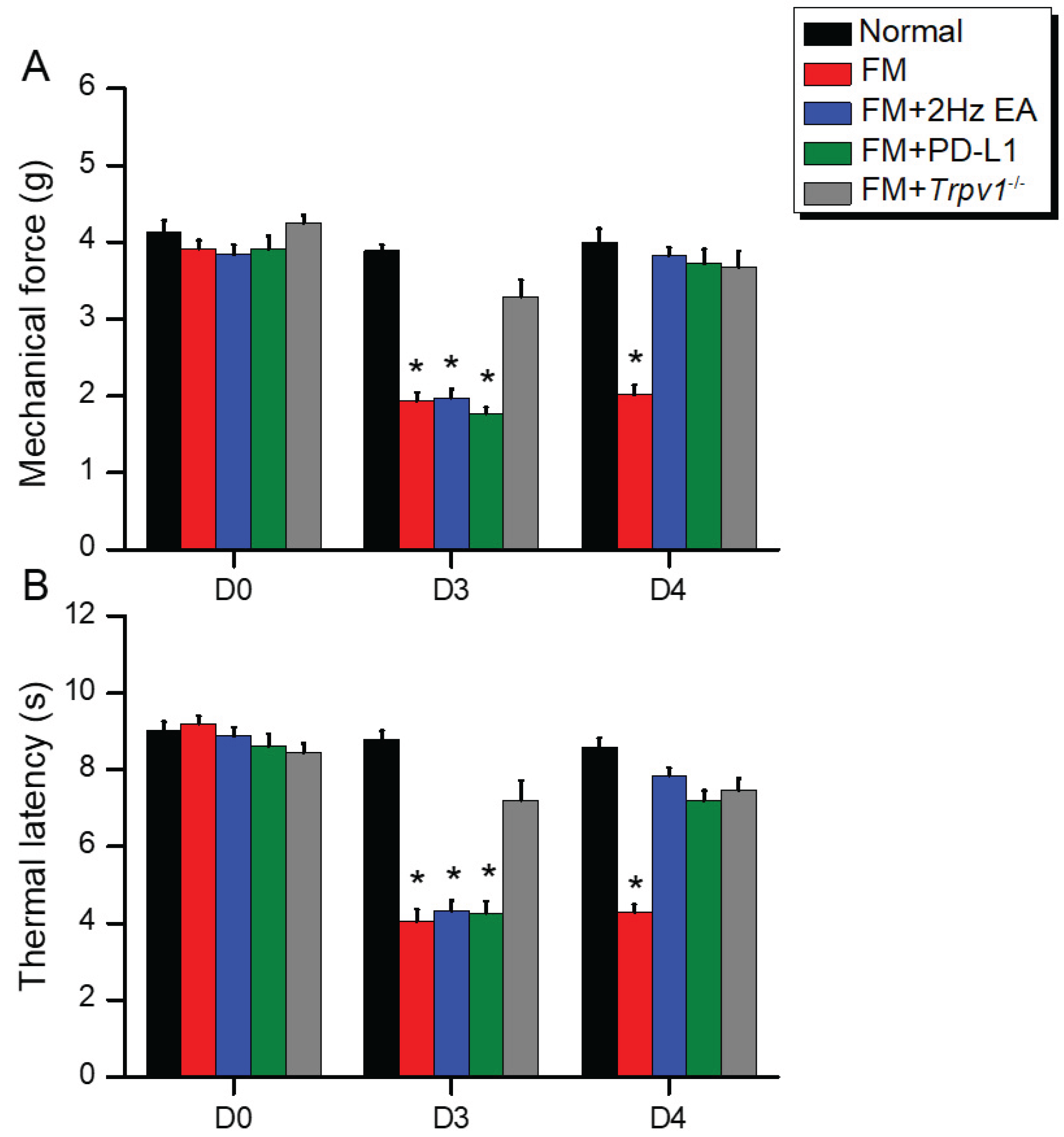

2.1. Intermittent Cold Stress Successfully Induced Mechanical and Thermal Hyperalgesia Alleviated by EA, ICV PD-L1, or Trpv1 Deletion

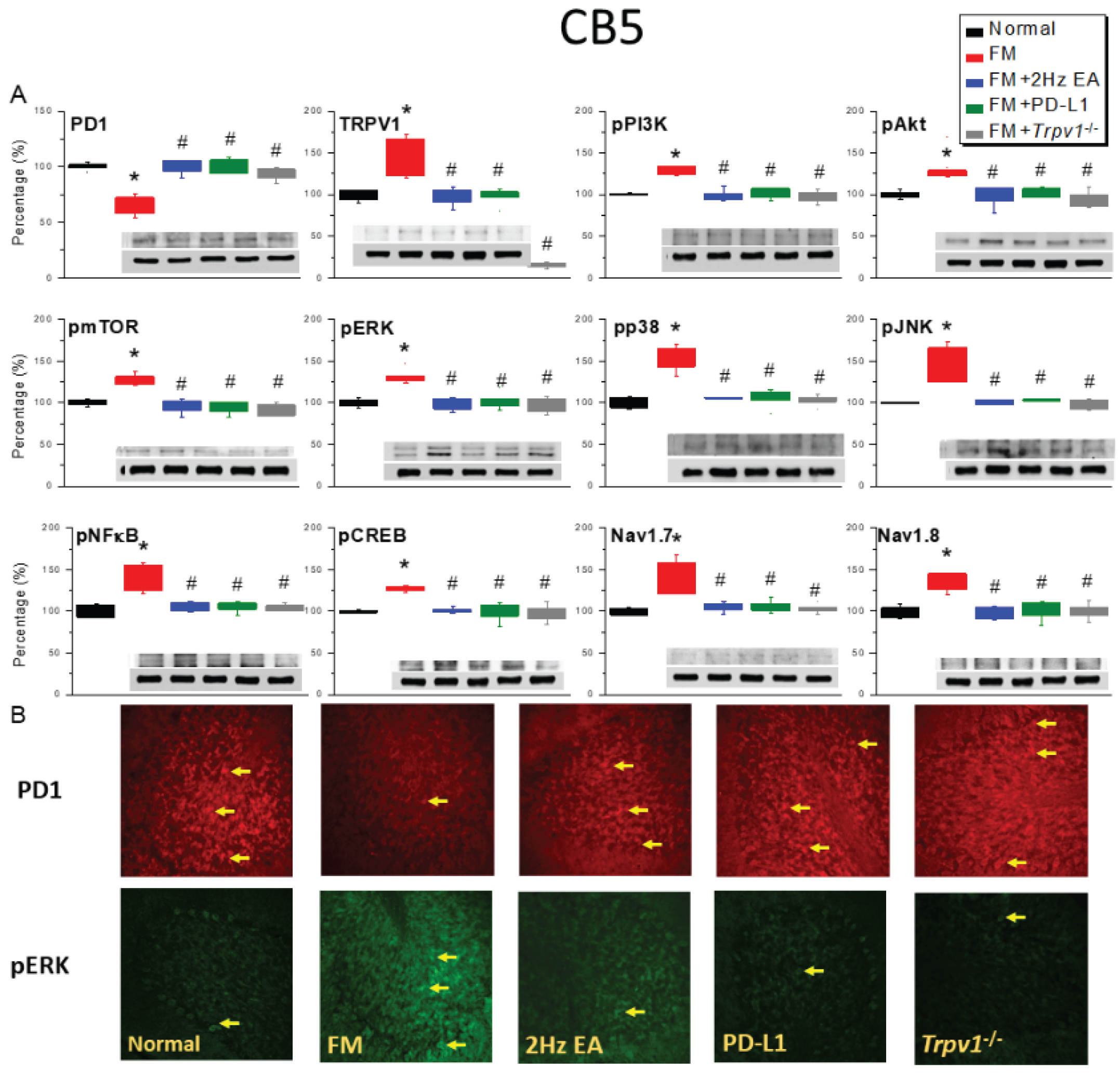

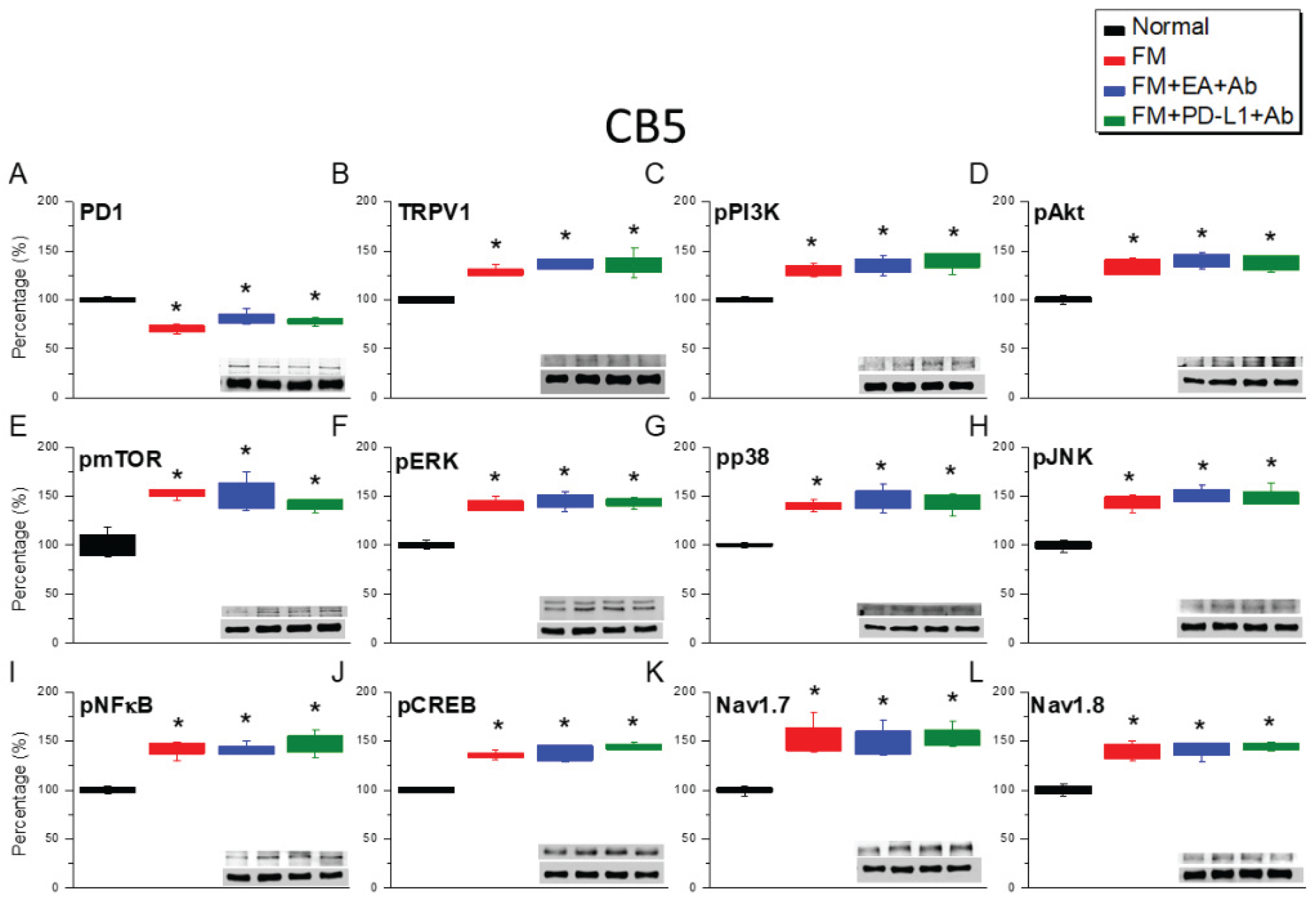

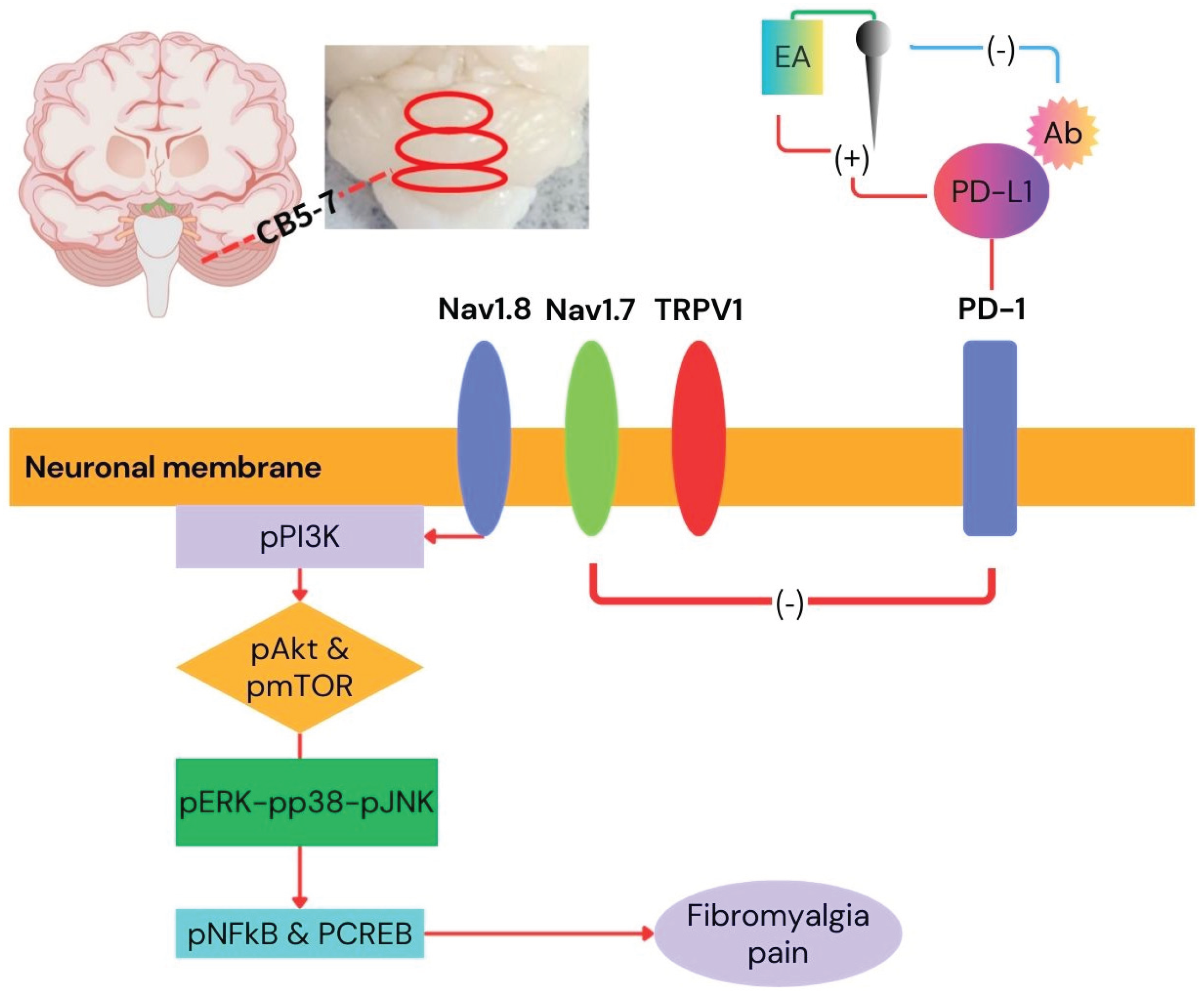

2.2. PD-1 Was Attenuated and Nociceptive TRPV1 Signaling Increased in the CB5 Region of FM Mice: These Phenomena Were Reversed by EA, ICV PD-L1 Injection, or Trpv1 Deletion

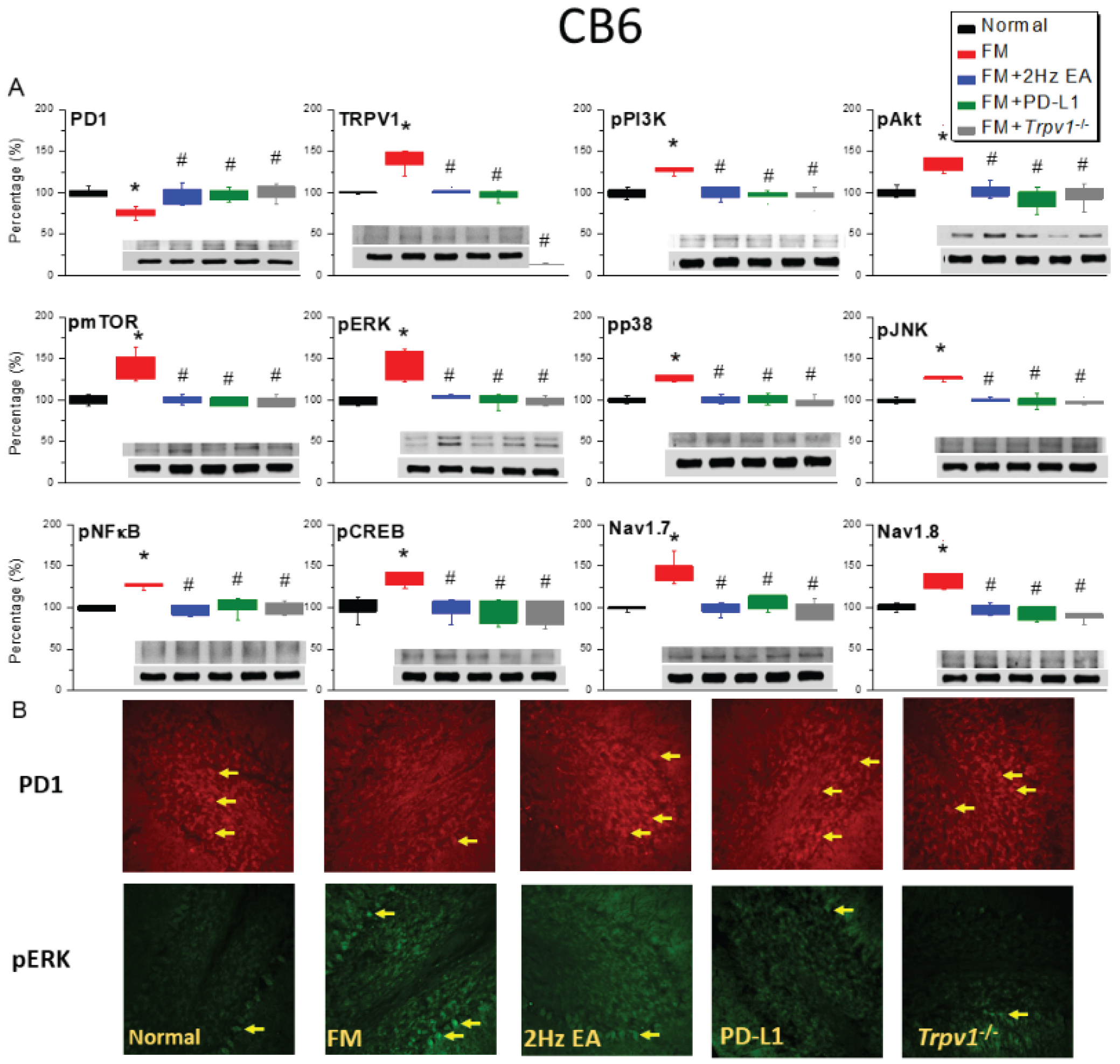

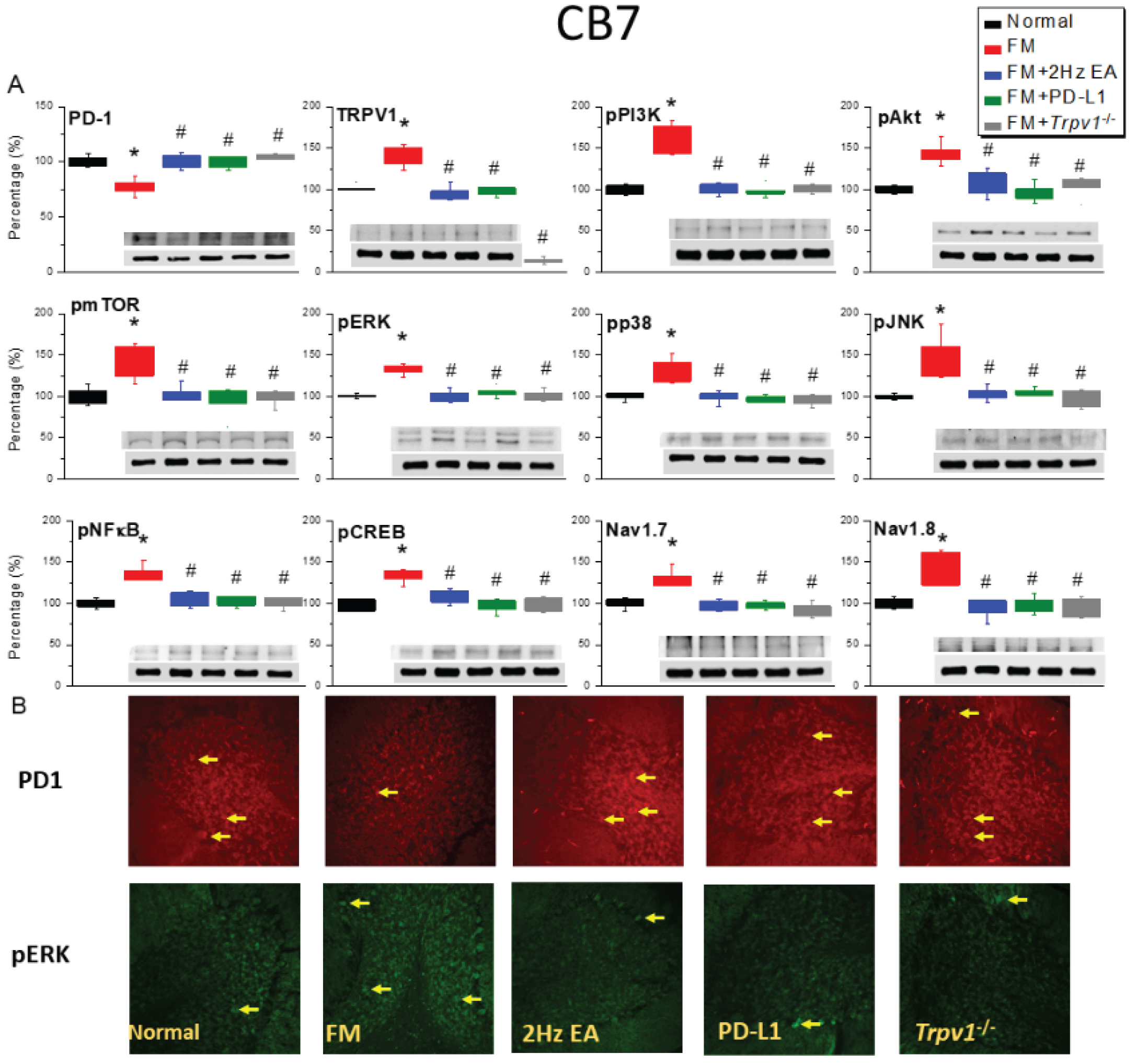

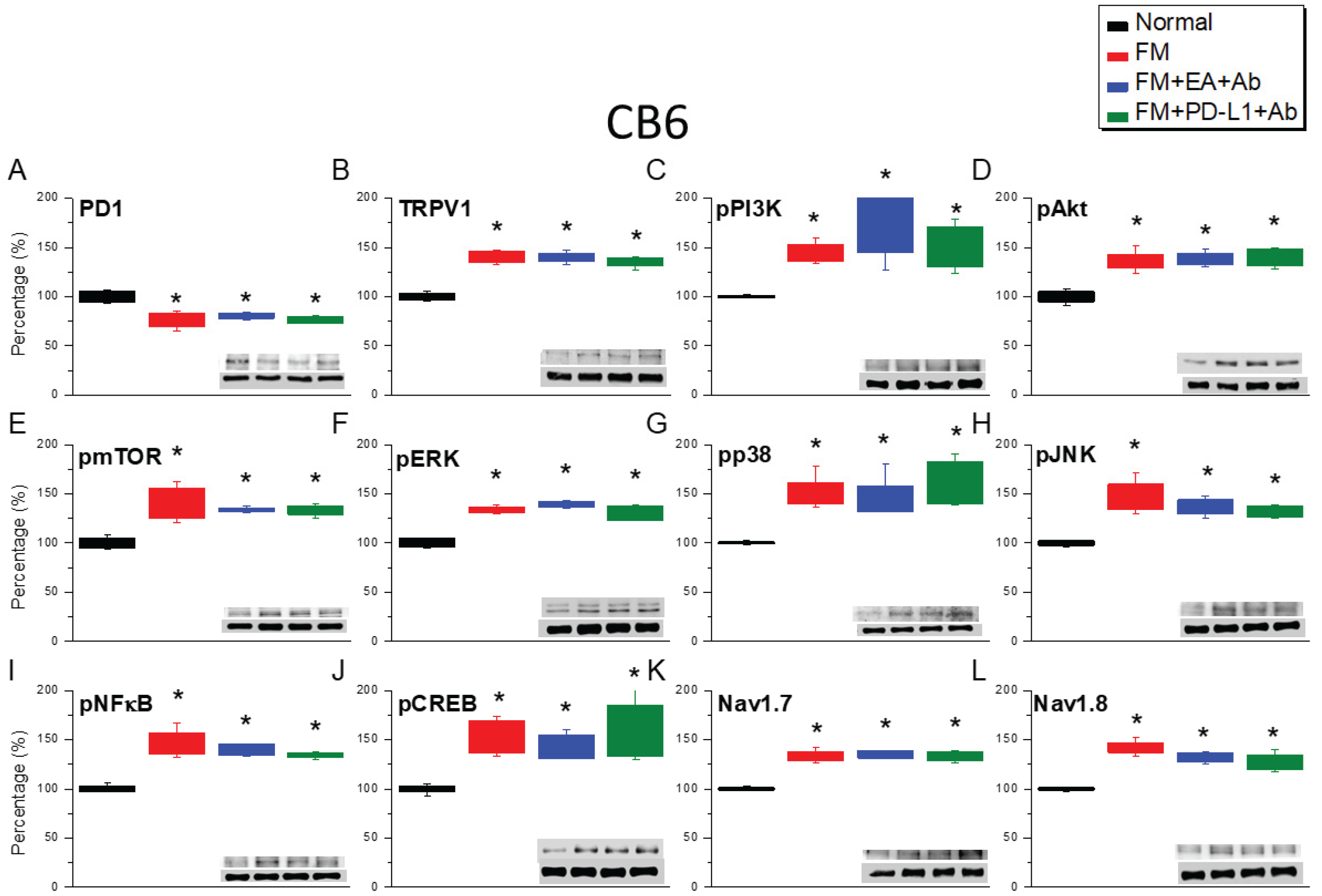

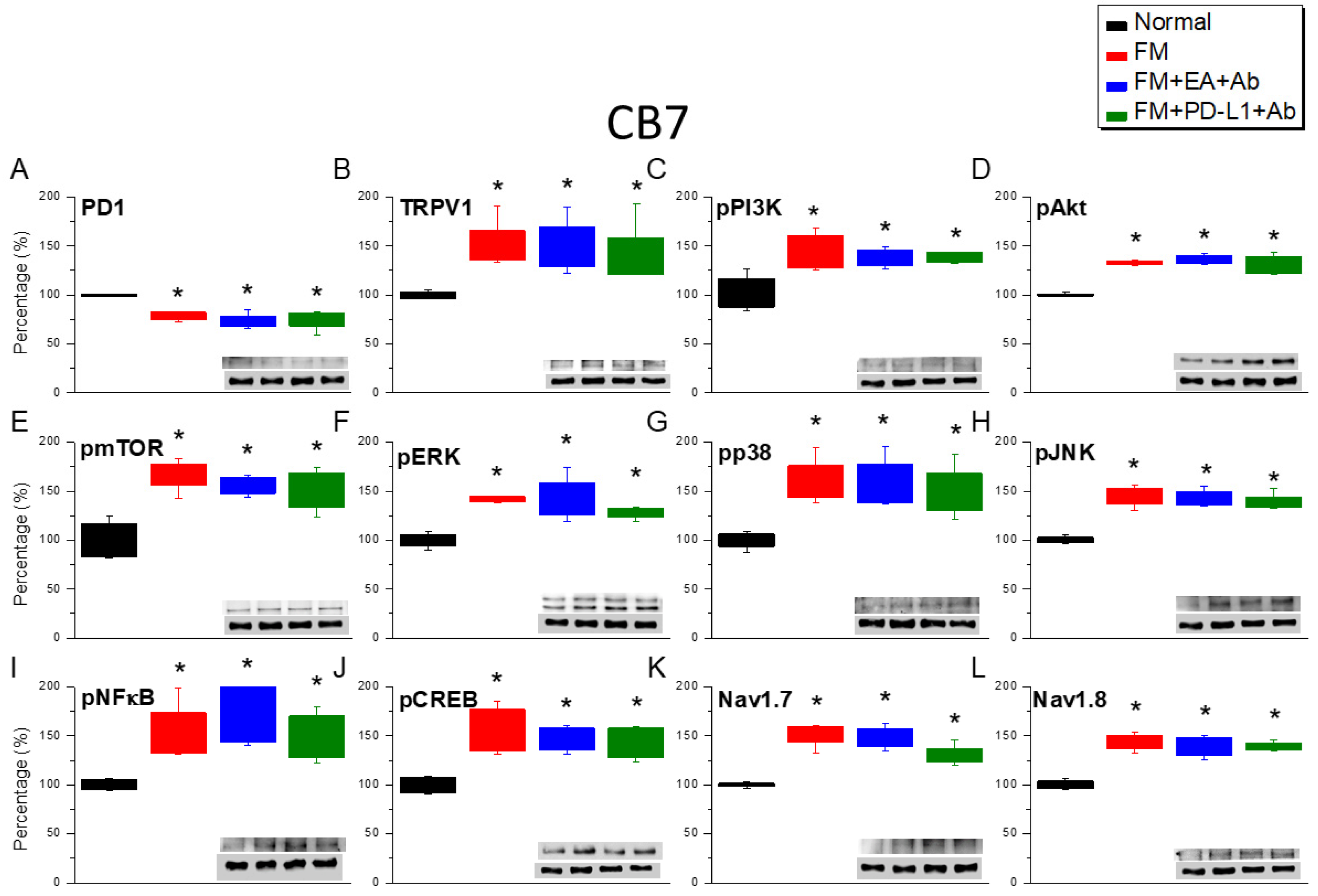

2.3. Effects of EA, ICV PD-L1 Injection, and Trpv1 Deletion on Cold Stress-Induced Fibromyalgia Pain in the CB6 and CB7

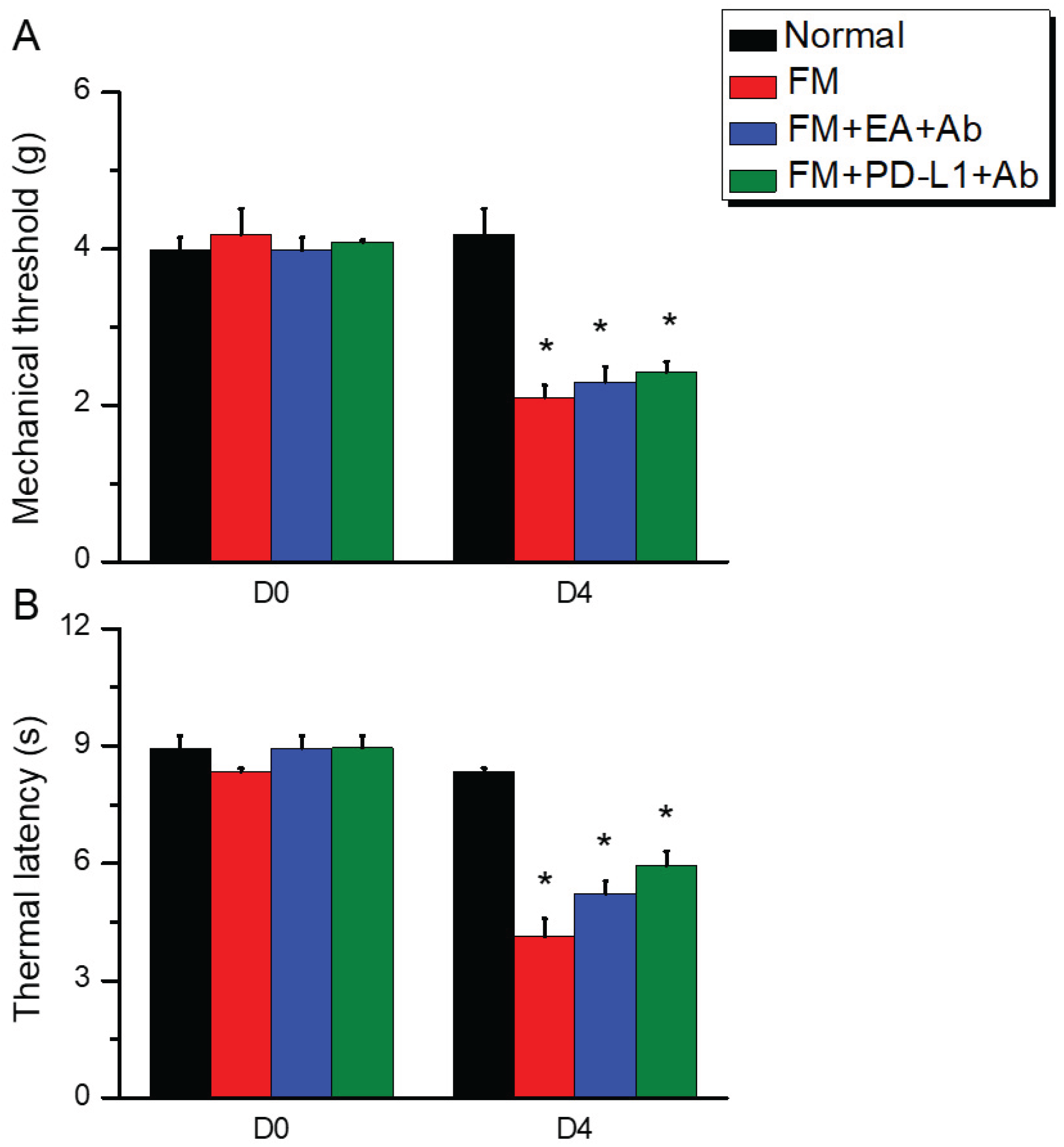

2.4. ICV PD-L1 Neutralizing Antibodies Reversed the Analgesic Effects of EA or PD-L1 in Fibromyalgia Mice

2.5. The Analgesic Effect of EA or PD-L1 Injection Was Reversed by PD-L1 Neutralizing Antibody Injection

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Fibromyalgia Pain Induction

4.2. Electroacupuncture

4.3. Nociceptive Behavior Measurements

4.4. Western Blot Analysis

4.5. Immunofluorescence

4.6. Intracerebroventricular Injection

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Main Findings and Implications

Study Strengths, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Honjo, T. Seppuku and autoimmunity. Science 1992, 258, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.A.; Boaru, D.L.; De Leon-Oliva, D.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; Garcia-Montero, C.; Rios, L.; Garrido-Gil, M.J.; Barrena-Blazquez, S.; Minaya-Bravo, A.M.; Rios-Parra, A.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 axis: implications in immune regulation, cancer progression, and translational applications. J Mol Med (Berl) 2024, 102, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kim, Y.H.; Li, H.; Luo, H.; Liu, D.L.; Zhang, Z.J.; Lay, M.; Chang, W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Ji, R.R. PD-L1 inhibits acute and chronic pain by suppressing nociceptive neuron activity via PD-1. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado-Priego, L.N.; Cueto-Urena, C.; Ramirez-Exposito, M.J.; Martinez-Martos, J.M. Fibromyalgia: A Review of the Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Multidisciplinary Treatment Strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamou, M.; Kremers, F.A.C.; Samaritakis, K.A.; Roggen, E.L. Identifying microRNAs Possibly Implicated in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, J.; Imamura, M.; Robertson, C.; Whibley, D.; Aucott, L.; Gillies, K.; Manson, P.; Dulake, D.; Abhishek, A.; Tang, N.K.Y.; et al. Effects of Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Interventions for the Management of Sleep Problems in People With Fibromyalgia: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2025, 77, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstrom, A.H.C.; Konsman, J.P.; Kosek, E. Cytokines in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Chronic Pain in Humans: Past, Present, and Future. Neuroimmunomodulation 2024, 31, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Dou, B.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Du, S.; Li, J.; Yao, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Gong, Y.; et al. Effects and mechanisms of acupuncture analgesia mediated by afferent nerves in acupoint microenvironments. Front Neurosci 2023, 17, 1239839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rosas, R.; Yehia, G.; Pena, G.; Mishra, P.; del Rocio Thompson-Bonilla, M.; Moreno-Eutimio, M.A.; Arriaga-Pizano, L.A.; Isibasi, A.; Ulloa, L. Dopamine mediates vagal modulation of the immune system by electroacupuncture. Nat Med 2014, 20, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Qi, L.; Yang, W.; Fu, M.; Jing, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Q. A neuroanatomical basis for electroacupuncture to drive the vagal-adrenal axis. Nature 2021, 598, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.; Cheng, C.M.; Yen, C.M.; Lin, Y.W. Paper-Based Detection Device for Microenvironment Examination: Measuring Neurotransmitters and Cytokines in the Mice Acupoint. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Optogenetic modulation of electroacupuncture analgesia in a mouse inflammatory pain model. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Attenuates Chronic Inflammatory Pain and Depression Comorbidity through Transient Receptor Potential V1 in the Brain. Am J Chin Med 2021, 49, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I.H.; Yen, C.M.; Hsu, H.C.; Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Chemogenetics Modulation of Electroacupuncture Analgesia in Mice Spared Nerve Injury-Induced Neuropathic Pain through TRPV1 Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, I.H.; Lin, M.C.; Hsu, H.C.; Chae, Y.; Su, Y.K.; Lin, Y.W. Chemogenetic Modulation of Electroacupuncture Analgesia in a Mouse Intermittent Cold Stress-Induced Fibromyalgia Model by Activating Cerebellum Cannabinoid Receptor 1 Expression and Signaling. Life (Basel) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Park, H.J.; Liao, H.Y.; Chuang, K.T.; Lin, Y.W. Accurate Chemogenetics Determines Electroacupuncture Analgesia Through Increased CB1 to Suppress the TRPV1 Pathway in a Mouse Model of Fibromyalgia. Life (Basel) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.A.; Hsu, H.C.; Lin, M.C.; Chen, T.S.; Lin, W.C.; Huang, H.M.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Regulates Cannabinoid Receptor 1 Expression in a Mouse Fibromyalgia Model: Pharmacological and Chemogenetic Modulation. Life (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghowsi, M.; Qalekhani, F.; Farzaei, M.H.; Mahmudii, F.; Yousofvand, N.; Joshi, T. Inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and hypertension as mediators for adverse effects of obesity on the brain: A review. Biomedicine 2021, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.W.; Chou, A.I.W.; Su, H.; Su, K.P. Transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) modulates the therapeutic effects for comorbidity of pain and depression: The common molecular implication for electroacupuncture and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 89, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgren, M.; Sandstrom, A.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Mannerkorpi, K.; Gerdle, B.; Ernberg, M.; Fransson, P.; Kosek, E. The effects of a 15-week physical exercise intervention on pain modulation in fibromyalgia: Increased pain-related processing within the cortico-striatal- occipital networks, but no improvement of exercise-induced hypoalgesia. Neurobiol Pain 2023, 13, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Loggia, M.L.; Cahalan, C.; Garcia, R.G.; Vangel, M.G.; Wasan, A.D.; Edwards, R.R.; Napadow, V. Fibromyalgia is characterized by altered frontal and cerebellar structural covariance brain networks. Neuroimage Clin 2015, 7, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosch, B.; Hagena, V.; Herpertz, S.; Diers, M. Brain morphometric changes in fibromyalgia and the impact of psychometric and clinical factors: a volumetric and diffusion-tensor imaging study. Arthritis Res Ther 2023, 25, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Lin, C.; Yang, M.; Gu, J.; Jin, O. Alterations of the resting-state brain network connectivity and gray matter volume in patients with fibromyalgia in comparison to ankylosing spondylitis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 29960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.T.; Yang, C.C.; Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Reduces Fibromyalgia Pain via Neuronal/Microglial Inactivation and Toll-like Receptor 4 in the Mouse Brain: Precise Interpretation of Chemogenetics. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Zhang, T.; Ma, L.; Zhao, W.; Huang, S.; Wang, K.; Shu, S.; Chen, X. PD-L1/PD-1 pathway: a potential neuroimmune target for pain relief. Cell Biosci 2024, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, C.W.S.; Maganin, A.G.M.; Adjafre, B.; Mendes, A.S.; Silva, C.E.A.; Quadros, A.U.; Luiz, J.P.M.; Silva, C.M.S.; Silva, N.R.; Oliveira, F.F.B.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibition Enhances Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain by Suppressing Neuroimmune Antinociceptive Signaling. Cancer Immunol Res 2022, 10, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ma, Y.; Song, X.; Wu, Y.; Jin, P.; Chen, G. PD-1: A New Candidate Target for Analgesic Peptide Design. J Pain 2023, 24, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Lu, M.; Yao, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, G. An analgesic peptide H-20 attenuates chronic pain via the PD-1 pathway with few adverse effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2204114119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Han, Y.; Wang, D.; Guo, P.; Wang, J.; Ren, T.; Wang, W. PD-L1 and PD-1 expressed in trigeminal ganglia may inhibit pain in an acute migraine model. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).