1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia pain had been predicted to increase owing to lack of medicines for the symptoms and the illness. Fibromyalgia is challenging particularly because it is difficult to ascertain the cause of pain due to deficient diagnosis, symptomatology, and lack of meaningful biomarkers. So far, there is no standard therapy and no other alternatives to help fibromyalgia patients [

1]. A recent study suggested that fibromyalgia patients had predominantly higher salivary cortisol concentrations than healthy subjects, which were risk factors for insomnia, stress, anxiety, and depression [

2]. Neuroinflammation has also been involved in fibromyalgia progression [

3]. Further, Cordón et al. identified that fibromyalgia patients had decreasing inner retinal neurons, suggesting neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration associated with fibromyalgia severity and a worsened quality of life [

4]. In addition, fibromyalgia patients were found to have central sensitization in the central nervous system, including the brain and spinal cord, with increased pain sensation. Despite medications such as pregabalin, duloxetine, and milnacipran being approved by the US FDA for fibromyalgia pain relief, they have low patient satisfaction and side effects [

5]. Furthermore, a healthy lifestyle including practice of Tai chi, meditation, exercise, or yoga can help fibromyalgia patients to relax muscles, lower stress, and reduce pain syndromes [

6,

7,

8].

Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), also known as CD274, regulates cellular immune responses in dendritic cells, lymphocytes, and endothelial cells. PD-L1 is present in tumor cell membranes and can bind to the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) expressed in T cells. Accordingly, PD-L1/PD-1 signaling modulates immune function within the tumor microenvironment [

9,

10]. A recent article reported that interferon gamma (IFN-γ) significantly induced PD-L1 expression in tumor cells responding to cancer progression [

11]. Furthermore, interleukin (IL)-17 and TNF-α can independently control PD-L1 by activating AKT, nuclear factor-κB (NFκB), and extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK) signaling in cancer cells [

12]. In addition, IFN-γ inhibition can attenuate PD-L1 expression via the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)/ (TNF receptor associated factor 6) TRAF6 pathway [

13]. Thus, several drugs including atezolizumab, avelumab, nivolumab, and metformin aiming to inhibit the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway have been developed for cancer treatment. The latter can attenuate PD-L1 and exhibit antitumoral effects by stimulating endoplasmic-reticulum-linked deprivation [

14].

The communication between neurons and glial cells, mainly microglia (Iba1-positive) and astrocytes (GFAP-positive), in pain signaling is crucial for the development of chronic pain. In case of injury or pathophysiological situations, allodynia or hyperalgesia co-occur with irritable microglia or astrocyte activation. Overactivated microglia are considered proinflammatory M1 that can further increase the levels of inflammatory cytokines such as ILs, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and chemokines to initiate allodynia and hyperalgesia and cause chronic pain [

15,

16]. High mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) can be released increase by microglia or astrocyte in response to inflammation, and bind to inflammatory receptors such as the receptor for advanced glycation end products and toll-like receptors, further activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase and NFκB signaling pathways [

17,

18]. Astrocytic marker S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B) was also indicated to be activated in the brain areas, resulting in several chronic pain models. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) can participate in innate and adaptive immune responses. It has an extracellular domain to sense extracellular inflammatory mediators such as S100B, HMGB1, and lipopolysaccharide, which can trigger a series of downstream pathways responding to the induction, transduction, and maintenance of chronic pain. Activation could further trigger MyD88 to increase TRAF6 and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPS)/NKκB and the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ [

19,

20].

Acupuncture, an ancient element of Chinese medicine, was first used in Asia over 3 thousand years for disease relief, especially in pain management. Given its well-known therapeutic effect as well as low side effects, acupuncture is practiced worldwide to treat back, low back, and dental pain, headaches, tennis elbow, and fibromyalgia. Modern acupuncture involves inserting a very fine steel needle into a specific point called acupoint. Manual acupuncture involves inserting a fine needle into the acupoint with lifting and rotating to ensure the occurrence of the de-qi, suggesting successful manipulation. Electroacupuncture (EA) is reported to be therapeutically effective and consistent. A recent double-blinded, randomized controlled trial demonstrated that acupuncture could relieve chronic pain and major depression disorder [

21]. Further, EA can initiate antinociceptive efficacy in various mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain, as well as fibromyalgia [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The evidenced EA efficacy is considered to occur through increased opioid, dopamine, cannabinoid, and adenosine receptors. EA can also attenuate the release of proinflammatory IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IFN-γ. In addition, we previously demonstrated that EA could reduce mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia by suppressing TRPV1 signaling [

25].

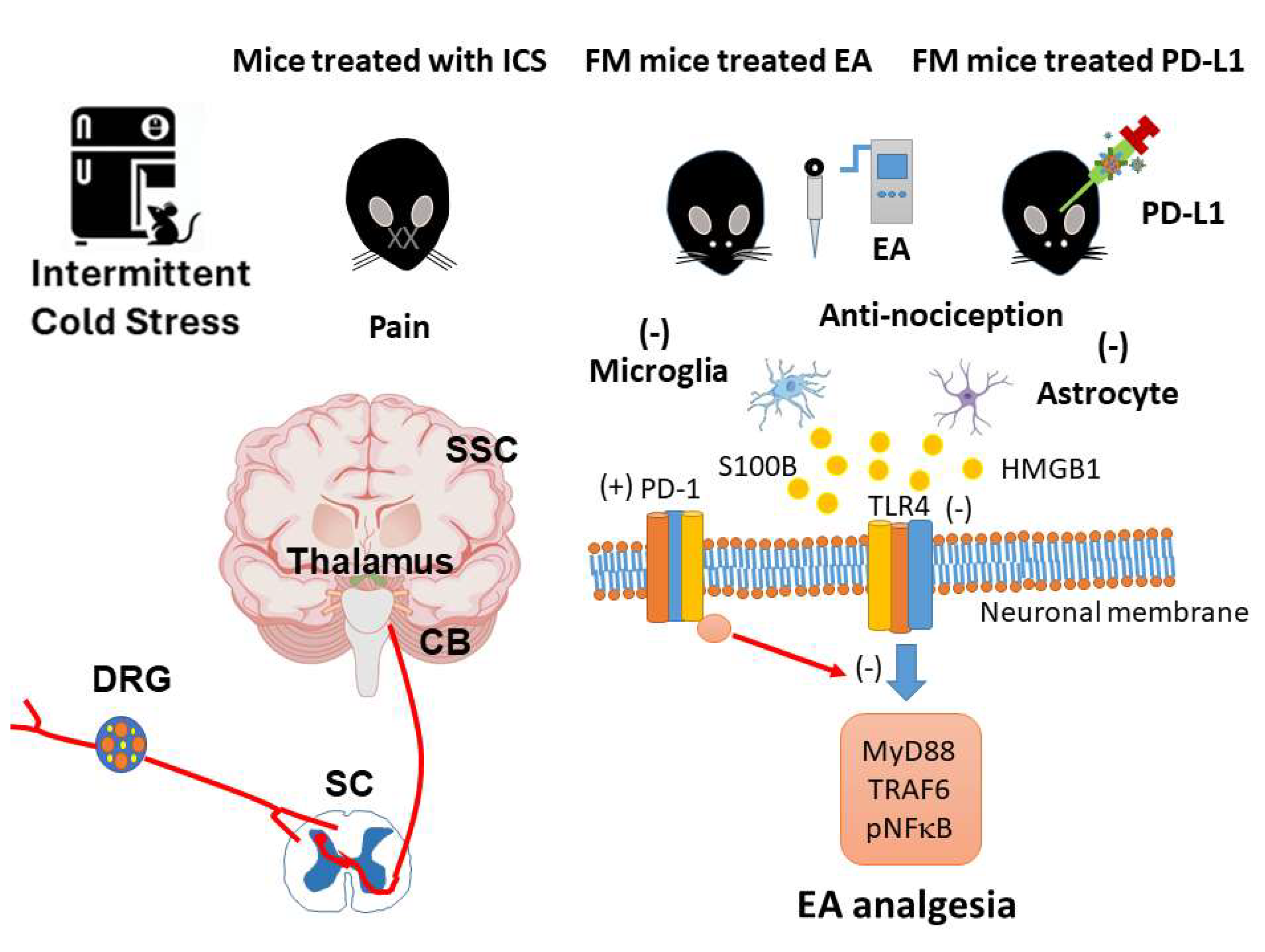

In the present study, we found the association of PD-L1/PD-1 present on the microglia/astrocytes with TLR4 and its allied signaling pathways in a mouse model of fibromyalgia pain induced by intermittent cold stress (ICS). Our results indicate that microglia or astrocyte numbers were increased in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) of fibromyalgia mice. Simultaneous results were observed for the neurotransmitters HMGB1 and S100B. Next, we observed reduced expression of the PD-1 receptor in the DRG of fibromyalgia mice. Levels of TLR4 and downstream molecules such as MyD88, TRAF6, and pNFκB, all increased in the DRG of fibromyalgia mice. These phenomena were all reversed in mice receiving EA treatment but not in i.c.v. PD-L1 injected mice, suggesting a central effect. Similar results were obtained in the spinal cord (SC), thalamus, somatosensory cortex (SSC), and cerebellum (CB). EA treatment or i.c.v. PD-L1 injection significantly reversed those effects. Our results provide novel insights into the relationship between EA analgesia and the PD-L1/ PD-1 pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice and Fibromyalgia Pain Model

Female C57B/L6 mice aged 8–12 weeks obtained from BioLasco Taiwan Ltd (Yilan, Taiwan) were used in the current study. Mouse weight was 18–20 g and they were kept in a specific pathogen-free environment before the experiments. After arrival, the mice were placed in a home cage under a 12-h light/dark cycle (light 6 a.m. to 6 p.m.). The temperature was maintained at 25ºC with 60% moisture. The experiments were approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee of China Medical University (Permit no. CMUIACUC-2024-076), Taiwan according to the Guide for the usage of Laboratory Animals (National Academy Press). Mice were randomly divided into four groups: normal (Normal); cold stress-induced fibromyalgia pain (FM); cold stress-induced fibromyalgia pain with EA (FM+EA); and cold stress-induced fibromyalgia pain with i.c.v. injection with PD-L1 (FM+PD-L1). To develop the mouse FM model, mice were kept in a 4ºC environment, while normal mice remained at 25ºC. At 10 a.m. the next day, FM mice were transferred to 25°C for 30 min, before being taken back at 4ºC for 30 min. This procedure was performed until 4 p.m., when they were moved again overnight from 4 p.m. during the first 3 days.

2.2. Nociceptive Behavior Examinations

Mice were placed in separate Plexiglas boxes perforated overhead, placed on an elevated horizontal wire mesh stand, covered with a dark cloth, maintained in a silent environment, at room temperature (25ºC), and allowed to habituate for 30 min before starting the behavioral test. The experiments were only conducted when the mice were calm, all feet were placed on the surface, and without grooming or sleeping. The von Frey filament measuring instrument (IITC Life Science Inc., USA) was used to increase the pain pressure in the center of the right plantar hind paw of the mice. The maximum pressure was achieved when the right hind paw was lifted using the plastic tip and the mouse reflexively withdrew the hind paw. We allowed for 3-min breaks between stimuli. The results were recorded as mechanical sensitivity. The Hargreaves’ test was used for measuring mice thermal sensitivity and preparations were similar to those as the von Frey test. The subjects were placed in an animal enclosure that separated the mice to limit interaction and covered using a dark cloth. After allowing 30 min of habituation, the experiments were initiated. The IITC Plantar Analgesia Meter (IITC Life, Sciences, SERIES8, Model 390G) was used to measure the withdrawal latency time of mice subjected to radiant heat applied on the surface, targeting the center of the right hind paw.

2.3. Western Blot Analysis

The DRG, SC, thalamus, SSC, and CB of the mice were fleshy excise to extract proteins. Protein extracts were prepared, then, 10% radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) lysis buffer (Fivephoton Biochemicals, RIPA-50), 100 μL of a protease inhibitor (Bionovas, FC0070-0001), and 100 μL of phosphatase inhibitor (Bionovas, FC0050-0001) were added to the lysate. After homogenization, the mixture was centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min at 4ºC in an adjustable centrifuge. A total of 10 μL of extracted tissue sample was subjected to 8% or 12% SDS Tris-glycine gel electrophoresis, according to the protein size. A current electrophoresis power supply (PowerPac, Singapore) was used to run the gels in two sections: section 1 for 40 min at 50 V and section 2 for 1 h and 50 min at 100 V. A semidry transfer machine (Trans-Blot SD Cell, USA) transferred the gels onto PVDF membranes at 15 V for 45 min. The transferred membranes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline Tween (PBST with 0.05% Tween20) and blocked with bovine serum albumin for 30 min at 4ºC. Thereafter, the membranes were cultured with primary antibodies in PBST with 1% BSA and incubated overnight at 4ºC. Then, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at 1:5000, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratory, goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratory)), for 2 h at 25ºC. Finally, we used an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate kit (PIERCE) to visualize the protein bands on the membranes with LAS-3000 Fujifilm (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The image density levels of specific protein bands were quantified using NIH Image J 1.54h software (Bethesda, MD, USA). α-Tubulin was used as internal controller.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, a statistical program. All statistical data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SEM). Differences among groups were analyzed using an ANOVA test, followed by a post hoc Tukey’s test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Growing scientific evidence indicates that the immune checkpoint PD-L1 could be stimulated in cancer cells to inhibit T cell function through activation of the PD-1 receptor. Less is known about how the PD-1 signaling pathway can regulate pain signaling, especially in neuromodulation. A recent article reported that healthy tissue DRGs could release PD-L1 to notably inhibit either acute or chronic pain. Local PD-L1 injection can produce reliable antinociception in healthy mice through activation of PD-1. In addition, PD-L1 inhibition via neutralization or PD-1 receptor considerably initiated mechanical allodynia, suggesting its role in pain control. Genetic deletion of

Pd1 resulted in thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia. The released PD-L1 then binds to the PD-1 receptor of DRG nociceptive neurons, resulting in the phosphorylation of Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 (SHP-1). Phosphorylated SHP-1 next suppresses sodium channels and induces neuronal hyperpolarization over triggering potassium channels [

27]. TLRs expressed in primary nociceptive neurons, are important modulators of the immune system to regulate pain sensation via regulating ion channels; however, its relationship with PD-L1 is unelucidated.

Wang et al. reported that the immune therapy nivolumab, a monoclonal antibody drug against PD-1, has a therapeutic effect in tumor suppression. They then utilized the genetic knockout of the PD-1 receptor (

Pd1−/−) to demonstrate the defense of lung cancer cell-induced bone destruction. Mice lacking the PD-1 receptor showed higher nociceptive responses than healthy mice. In addition, this study determined that PD-L1 and chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) were simultaneously increased in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer cells also exhibited increased the expression of chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) in the mouse primary sensory neurons. The antagonism of CCR2 next produced significant attenuation of bone cancer pain [

28]. Spinal cord injury (SCI) causes motor disability and neuropathic pain, that is difficult to treat. PD-L1 increased after SCI in the microglia present at the epicenter of the injury site. Mice without PD-L1 showed more serious neuropathic pain due to increased polarization of M1-like microglia compared with normal mice. Furthermore, PD-L1 attenuated neuropathic pain after SCI by inhibiting pp38 and pERK1/2 [

29]. Shi et al. observed PD-L1 and PD-1 immuno-positive signals in normal trigeminal ganglia neurons. They then determined that the mRNA and protein levels of PD-L1 and PD-1 were considerably increased after the acute nitroglycerin-induced mouse migraine model. Furthermore, they indicated that the inhibition of the PD-1 receptor potentiated acute nitroglycerin-induced migraine. Likewise, this phenomenon was simultaneously go along with amplified calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, and TNF-α expression in the trigeminal ganglia of neuropathic pain mice [

30]. Our findings are consistent in that EA or PD-L1 could reliably alleviate FM pain through the PD-1 receptor to attenuate the microglia/astrocyte signaling pathway.t

Clinically, after stroke, patents often experience thalamic pain, which is a neuropathic pain syndrome; an increase in cases of this type of neuralgia has been observed. A recent study declared that collagenase IV was injected into the right thalamus of the mice to induce thalamic pain, and dexmetatomidine (a selective α2 adrenergic receptor agonist) relieved the thalamic pain. The increased levels of Iba1, GFAP, and TLR4/NF-κB signaling in thalamic pain mice were reverted by intraperitoneal injection of dexmetatomidine [

31]. In neuropathic pain, targeting ion channels are on the rise for new drug development through the modulation of pain sensation, signal transduction, and management. Transient receptor potential channel melastatin 2 (TRPM2) was stated to adjust the Ca

2+ concentration and had a crucial effect in pain signaling, osmosis, and temperature sensing. A recent study indicated that TLR4 is one of the main receptors responding to inflammatory conditions. TLR4 activation resulted in higher oxidative stress and expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, etc. The potentiated molecules further activate TRPM2, which results in over influx of Ca

2+ to induce neuronal damage [

32]. Converting M1, increased proinflammatory factors, or M2, neuroprotective effects, and the microglial phenotype was reported as an encouraging healing approach for acute and chronic pain. A recent article declared that the antiinflammatory dietary flavonoid kaempferol had an analgesic effect in a mouse chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain model. Their data indicated that kaempferol reliably relieved neuropathic pain accompanied by reduced proinflammatory cytokine production. They showed that kaempferol reliably reduced the neuropathic pain-induced overexpression ofTLR4/NF-κB in the SC of rats. Kaempferol can attenuate neuropathic pain by promoting microglial polarization from the M1 to M2 phenotype [

33].

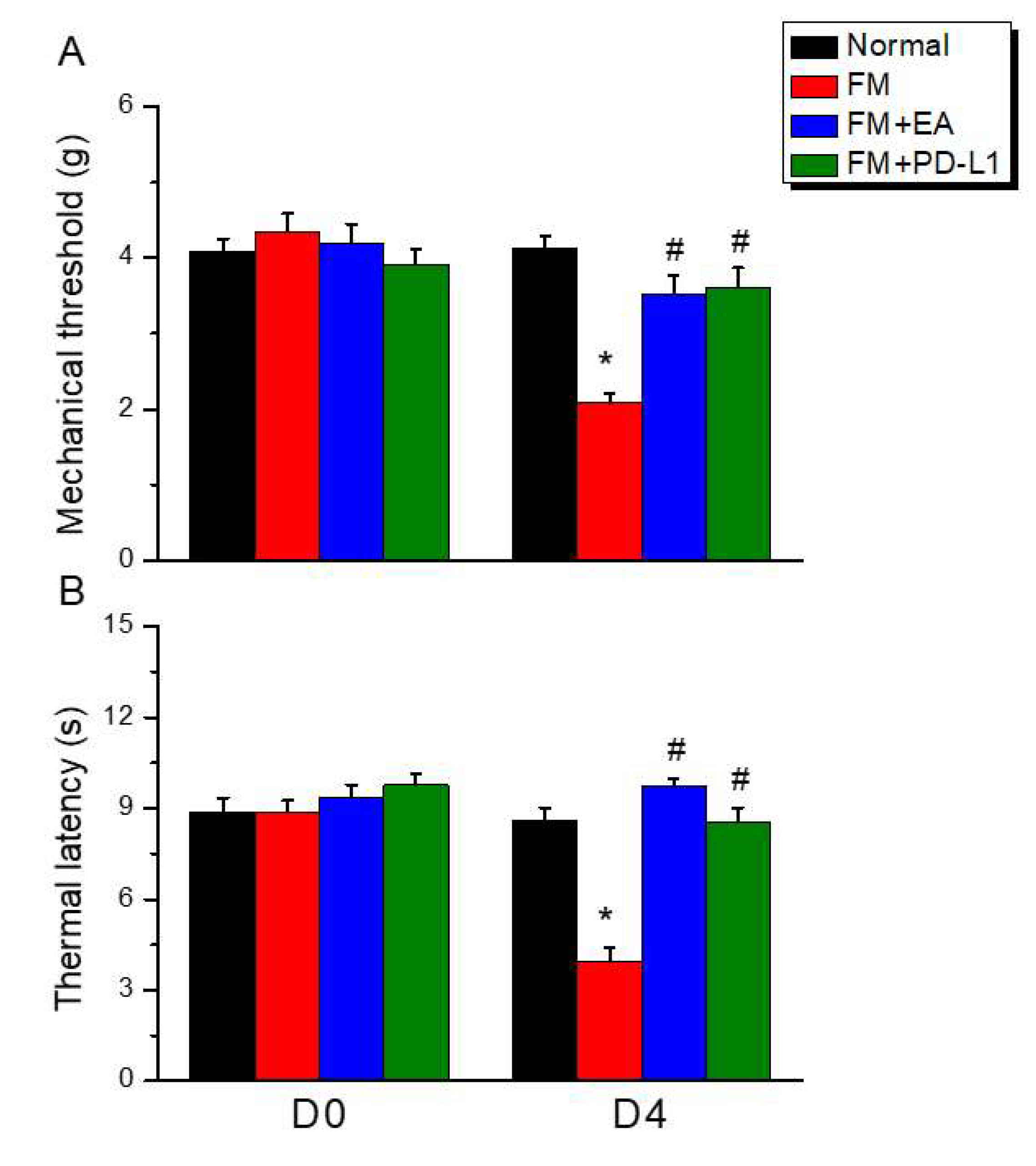

Figure 1.

Electroacupuncture or PD-L1 i.c.v. inoculation reduced the fibromyalgia pain after ICS. (A) Mechanical hyperalgesia verified using the von Frey test. (B) Thermal hyperalgesia determined using the Hargraves’ analysis. Normal: normal mice; FM: fibromyalgia mice; FM+EA: fibromyalgia mice treated with EA; FM+PD-L1: fibromyalgia mice treated with PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs Normal. #P < 0.05 vs FM group.

Figure 1.

Electroacupuncture or PD-L1 i.c.v. inoculation reduced the fibromyalgia pain after ICS. (A) Mechanical hyperalgesia verified using the von Frey test. (B) Thermal hyperalgesia determined using the Hargraves’ analysis. Normal: normal mice; FM: fibromyalgia mice; FM+EA: fibromyalgia mice treated with EA; FM+PD-L1: fibromyalgia mice treated with PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs Normal. #P < 0.05 vs FM group.

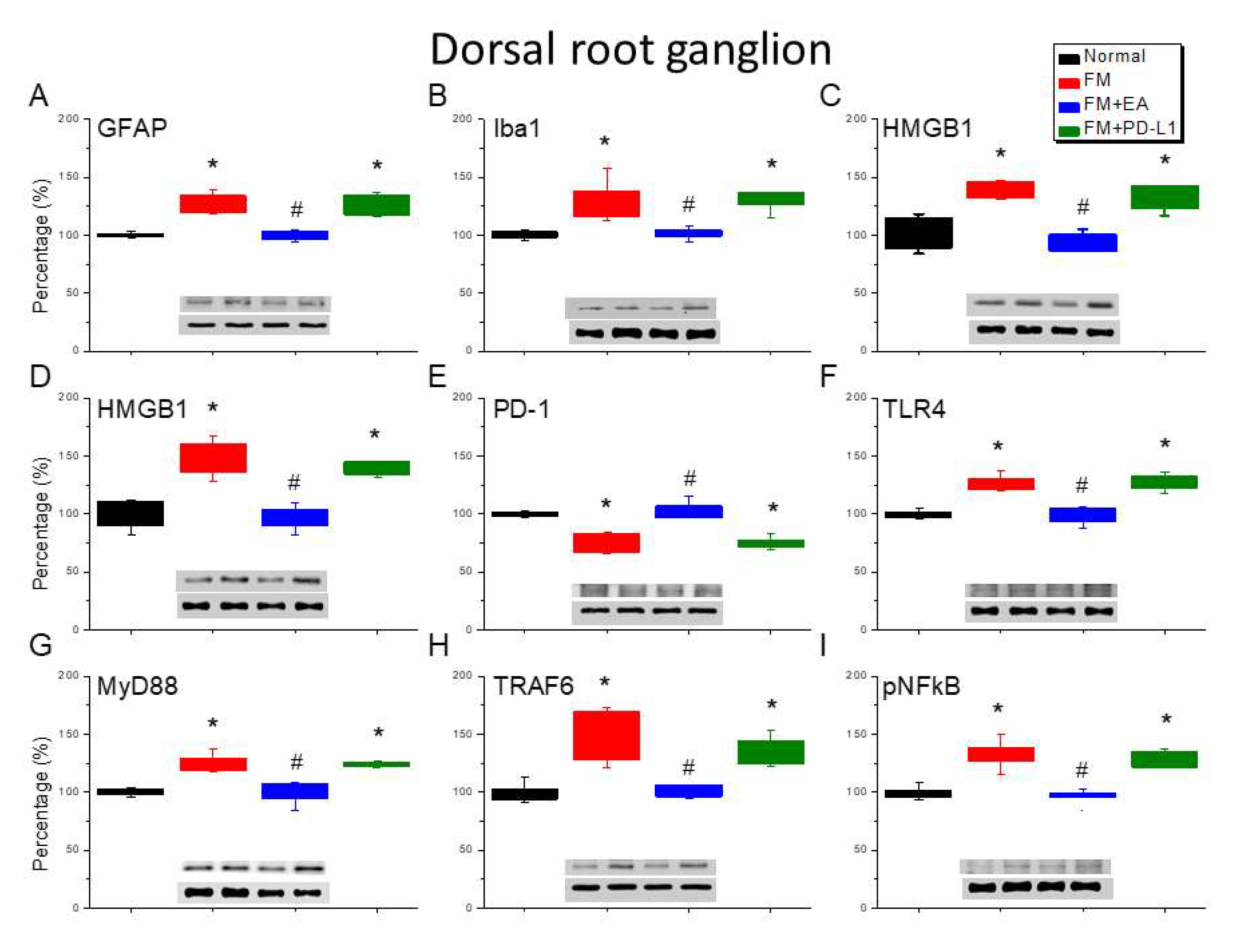

Figure 2.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the DRG of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 2.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the DRG of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

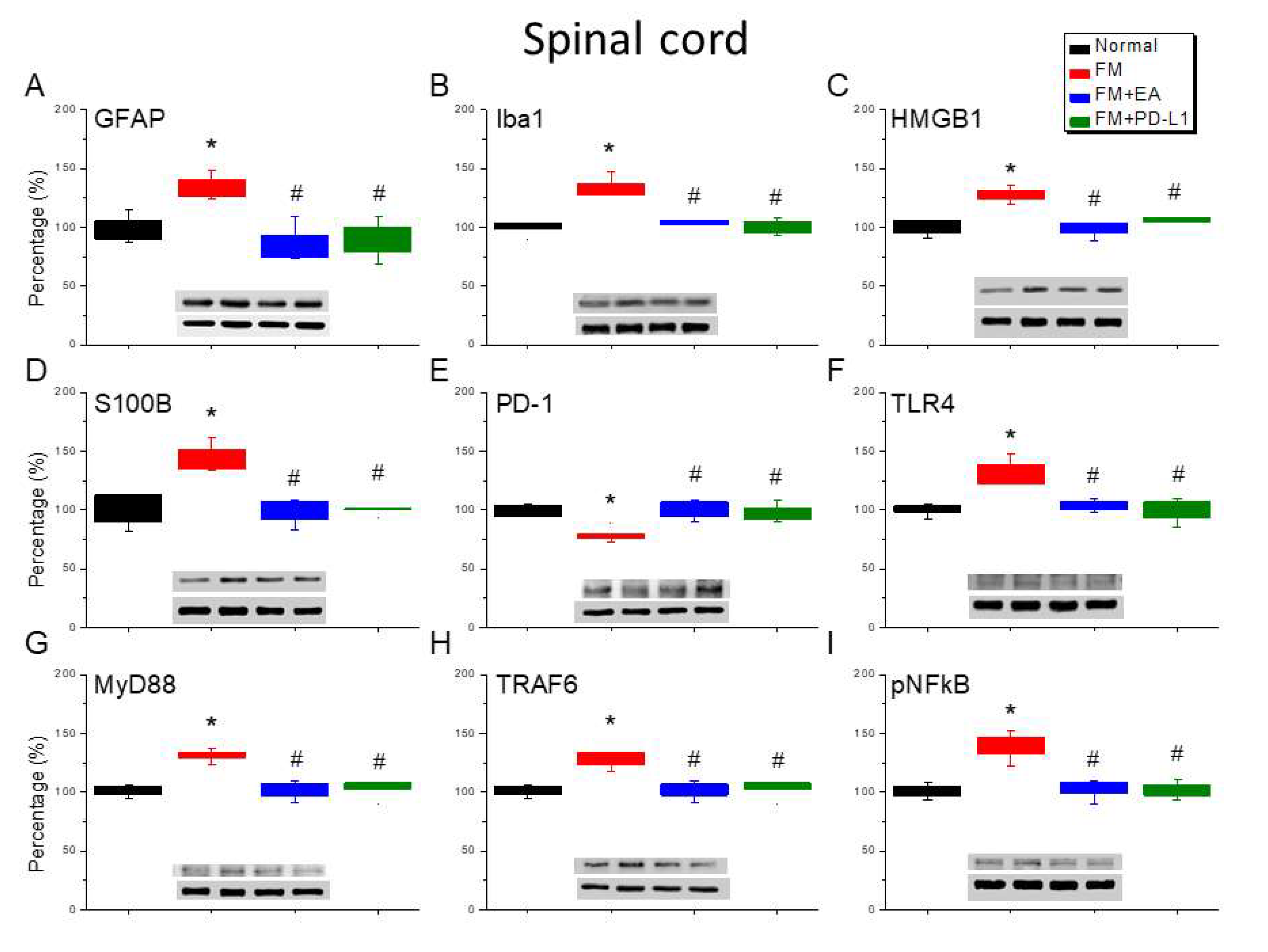

Figure 3.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the spinsl cord (SC) of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 3.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the spinsl cord (SC) of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

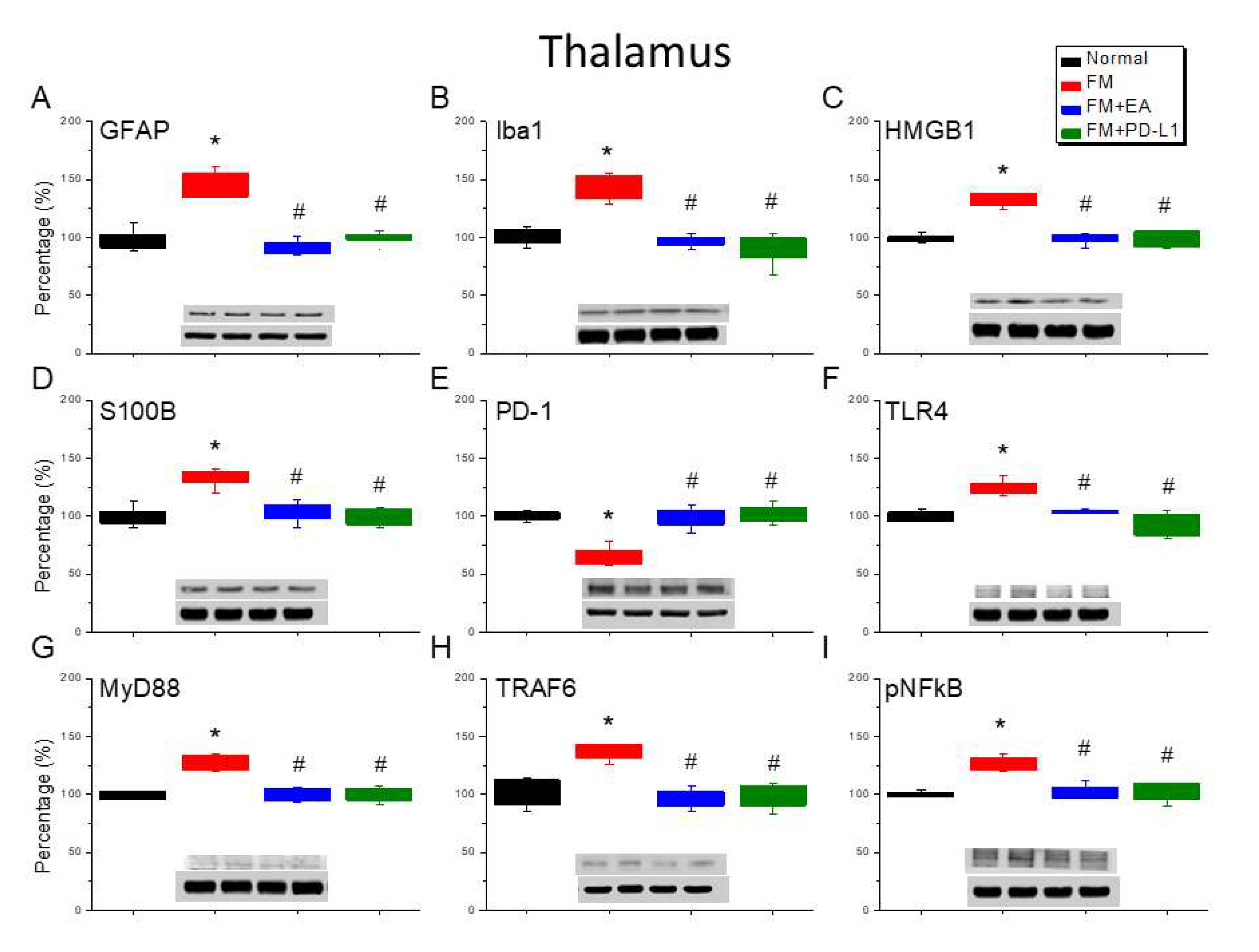

Figure 4.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the thalamus of mice in all groups including four lanes of A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 4.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the thalamus of mice in all groups including four lanes of A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

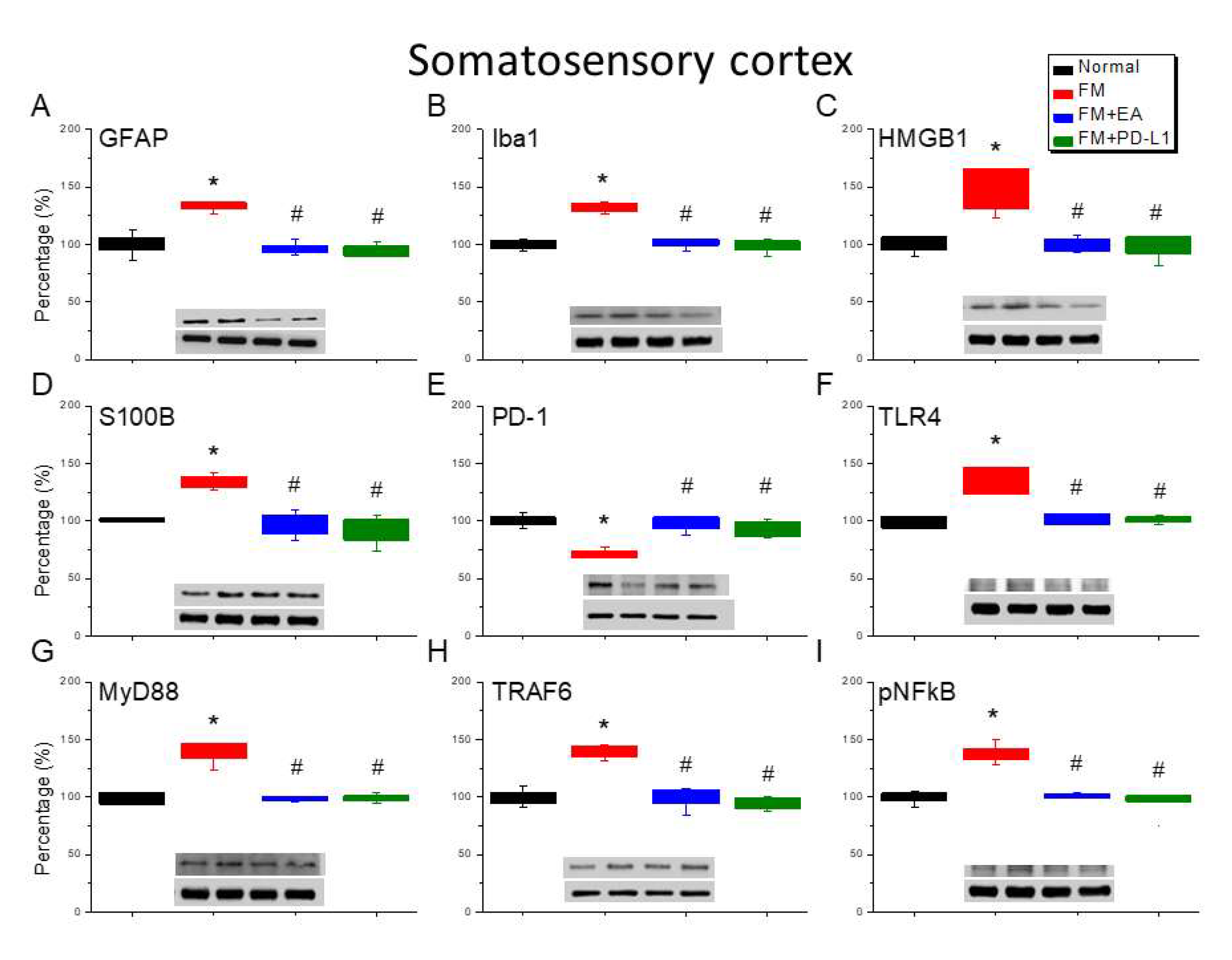

Figure 5.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the somatosensory cortex of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 5.

Changing protein levels of PD-1 on pain-related molecules in the somatosensory cortex of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

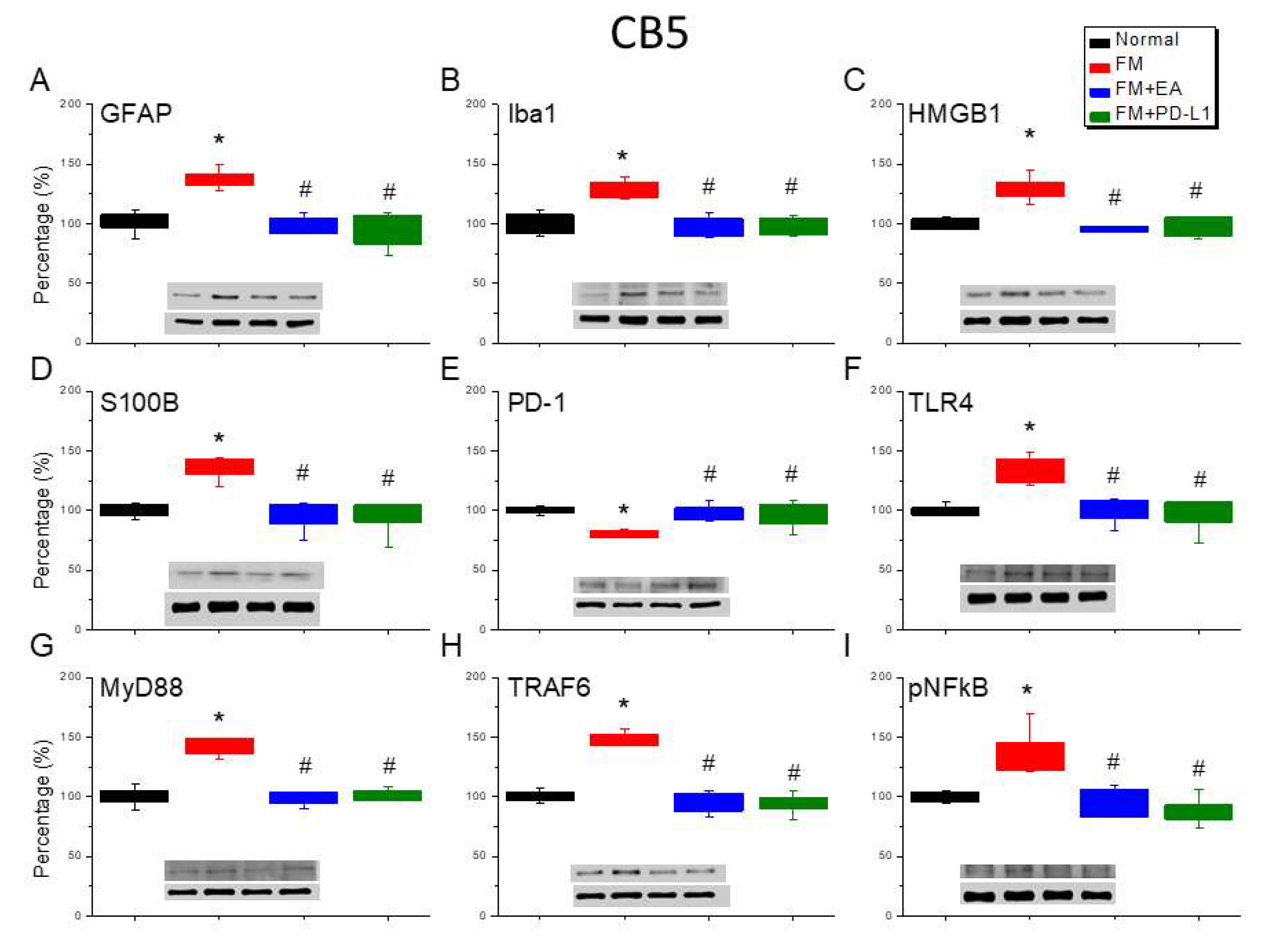

Figure 6.

Altering protein levels of PD-1 on pain-linked proteins in the CB5 of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 6.

Altering protein levels of PD-1 on pain-linked proteins in the CB5 of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

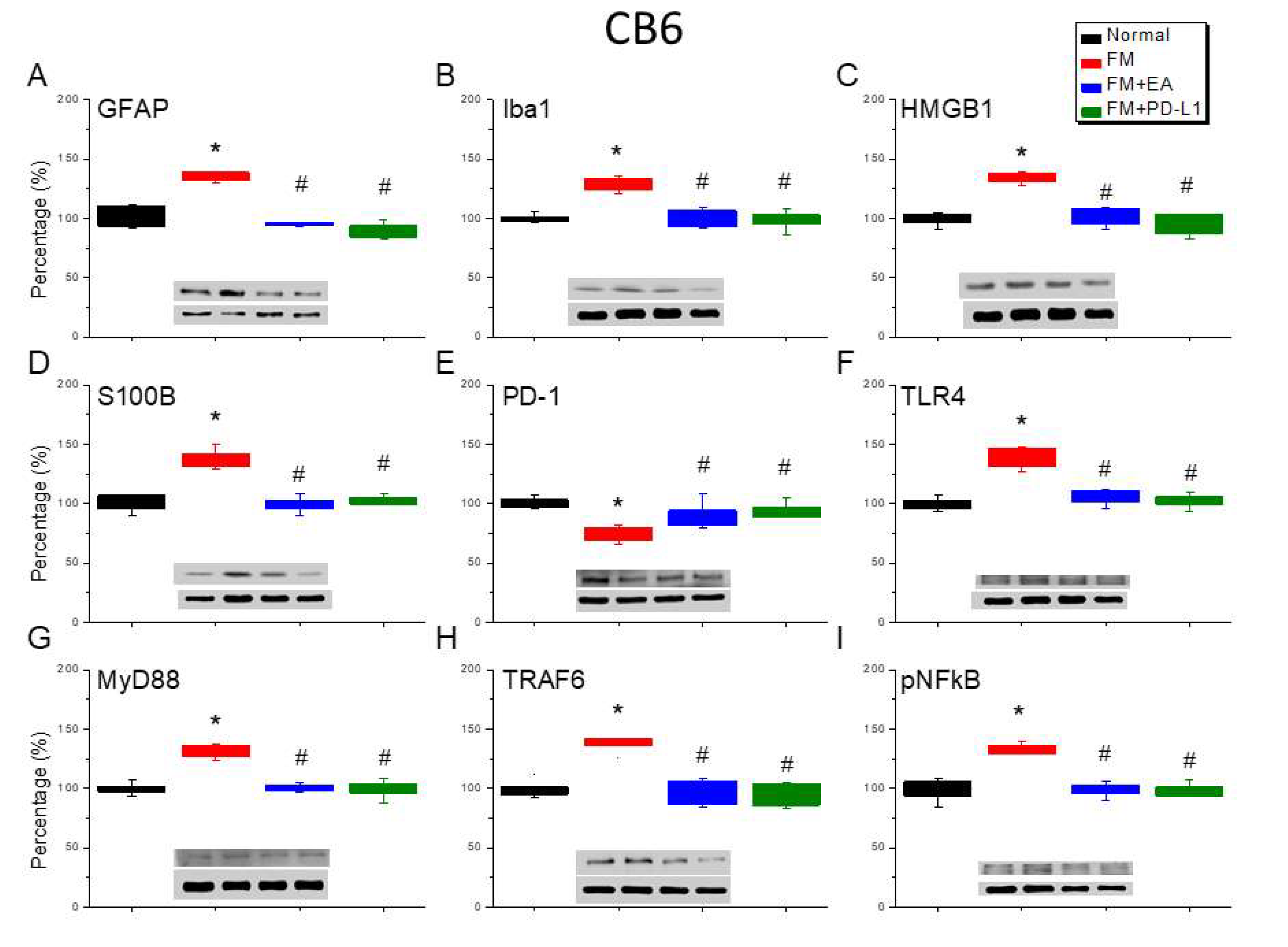

Figure 7.

Varying protein concentrations of PD-1 on pain-associated proteins in the CB6 of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 7.

Varying protein concentrations of PD-1 on pain-associated proteins in the CB6 of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

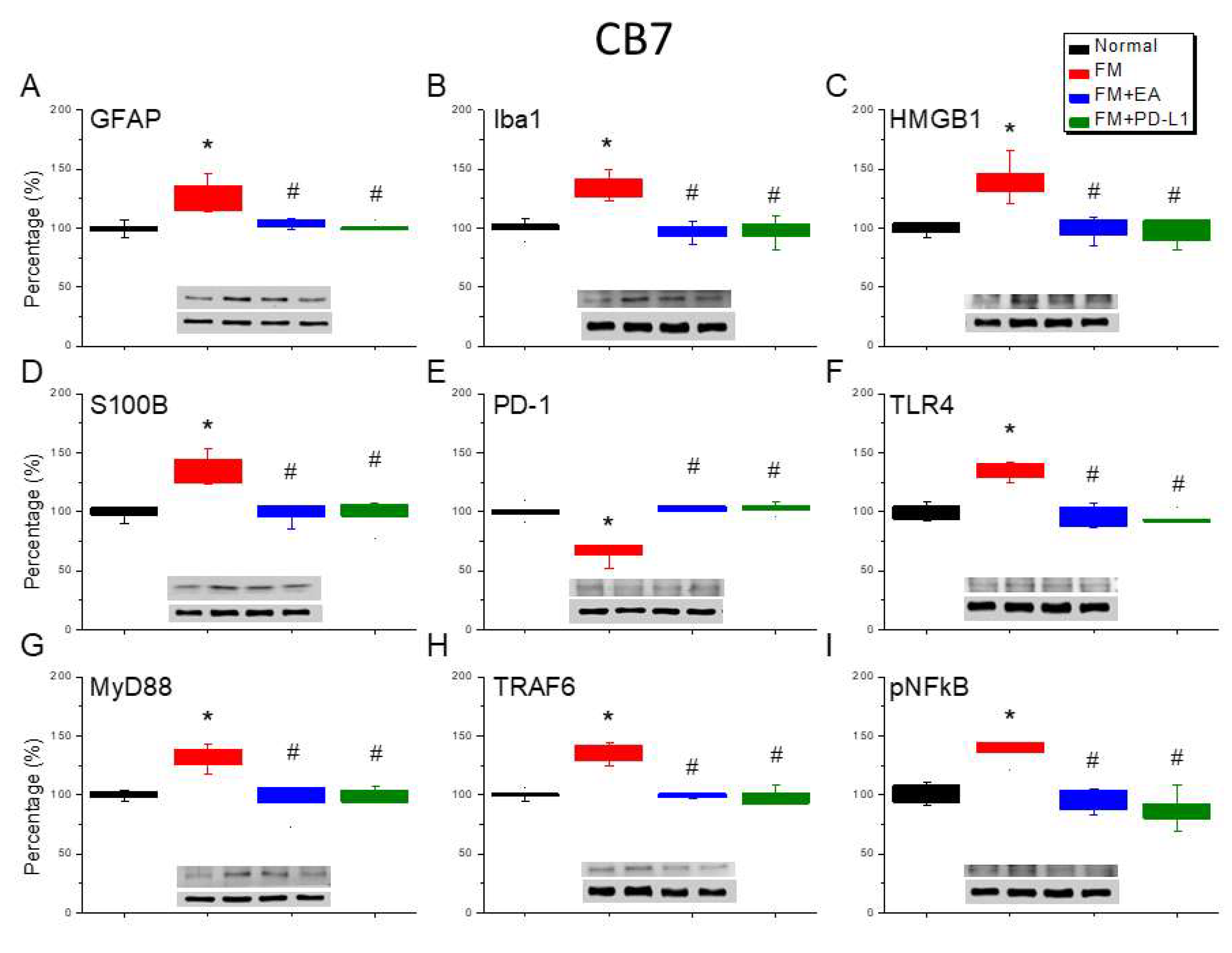

Figure 8.

Modifying protein levels of PD-1 on pain-associated proteins in the CB7 of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 8.

Modifying protein levels of PD-1 on pain-associated proteins in the CB7 of mice in all groups including four lanes of (A) GFAP, (B) Iba1, (C) S100B, (D) HMGB1, (E) PD-1, (F) TLR4, (G) MyD88, (H) TRAF6, (I) pNF-κB protein levels in Normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + PD-L1. *P < 0.05 vs the normal group, #P < 0.05 vs the FM group.

Figure 9.

The role of EA on PD-1 signaling pathway in mice fibromyalgia model. Abbreviations: EA = Electroacupuncture; TLR4 = Toll-like receptor 4; PD-L1 = Programmed cell death ligand 1; PD-1 = Programmed cell death protein 1; MyD88 = Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; TRAF6 = TNF Receptor Associated Factor 6; pNF-kB = phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells.

Figure 9.

The role of EA on PD-1 signaling pathway in mice fibromyalgia model. Abbreviations: EA = Electroacupuncture; TLR4 = Toll-like receptor 4; PD-L1 = Programmed cell death ligand 1; PD-1 = Programmed cell death protein 1; MyD88 = Myeloid differentiation primary response 88; TRAF6 = TNF Receptor Associated Factor 6; pNF-kB = phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells.