1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a chronic condition characterized by widespread, severe, and sustained pain, the cause of which remains unknown. The pain typically affects muscles, ligaments, tendons, and soft tissues, particularly in the shoulders, back, chest, arms, and legs. Symptoms often appear between the ages of 20 and 50 years and are exacerbated by cold weather, depression, anxiety, and inflammation [

1,

2]. Although several drugs are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for symptom relief, such as duloxetine, pregabalin, and milnacipran, no curative treatments exist for fibromyalgia. Therapeutic interventions are thus limited to symptom management and health promotion, which may include exercise, medication, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and other supportive therapies like music therapy. Fibromyalgia is highly comorbid with conditions such as depression, anxiety, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, osteoarthritis, and other chronic pain disorders [

3,

4,

5].

While the precise cause of FM remains unclear, recent studies have highlighted abnormalities in brain, immune, and endocrine functions, including glial activation. Brain dysfunction in FM may involve deficits in endogenous analgesic systems, such as the endogenous cannabinoid (CB) system [

6,

7], which is crucial for maintaining human health. Cannabinoids were first isolated from cannabis leaves, and endocannabinoids have been found in various tissues throughout the body. These molecules bind to cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2). Both receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains that activate downstream signaling cascades via Gi and Go proteins. However, CB1 and CB2 receptors exhibit distinct tissue distributions: CB1 receptors are mainly expressed in the central nervous system, while CB2 receptors are predominantly found in immune cells. Activation of CB1 receptors inhibits adenylate cyclase, leading to reduced intracellular cAMP and PKA activity. This pathway results in the inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels and the activation of potassium channels [

6,

7,

8], resulting in reduced neuronal excitability. Additionally, CB1 receptors modulate mitogen-activated protein kinase such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-jun N-terminal kinase, and p38. Alternatively, CB2 receptors primarily regulate immune signaling and may influence neuroinflammation through microglial cells [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Acupuncture is an ancient Chinese procedure used to treat a wide variety of ailments, particularly pain. It is based on the theory that there are 14 meridians through with qi (energy) flows along specific channels to maintain energy balance. These meridians are connected to ~365 accessible acupoints. Acupuncture needling involves inserting very fine steel needles into the skin or muscles at various acupoints to treat specific afflictions, with pain relief being one of the most common indications. For instance, acupuncture is used to relieve chemotherapy-induced pain, dental pain, labor pain, lower back pain, and fibromyalgia, among other conditions [

10,

11,

12]. We recently reported that acupuncture in mice can increase the concentrations of adenosine triphosphate, interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, glutamate, substance P, and histamine in the regional microenvironment of acupoints [

13]. These potential therapeutic effects may be enhanced by concomitant electrical stimulation or electroacupuncture (EA). Lin and colleagues (2020) reported that EA treatment attenuated fibromyalgia pain and that this analgesic effect was associated with reduced plasma concentrations of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ [

14]. We further demonstrated that EA reduced pain levels in a mouse model of inflammatory pain, possibly through effects on adenosine and opioid receptor signaling [

15,

16]. Additionally, EA has been shown to decrease inflammatory, neuropathic, and FM-related pain in numerous other mouse models. Acupuncture has also been used effectively to alleviate obesity-induced depression by regulating inflammatory cytokines and the TRPV1 pathway [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Given that depression is a major comorbidity in FM patients, this underscores the potential utility of EA for comprehensively mitigating FM symptoms. However, the fundamental cellular mechanisms underlying the effects of EA on FM remain poorly understood.

In the current study, we examined whether FM-associated pain and EA-induced analgesia are associated with CB1 signaling in a mouse model. To this end, we measured both mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in FM model mice and subsequently examined the expression levels of CB1 and related signaling factors in the cerebellum, a region strongly implicated in FM pain. Our hypothesis is that EA can alleviate FM symptoms by promoting CB1 signaling in the cerebellum. We report that 2-Hz EA but not sham EA attenuated mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in FM model mice and reversed both CB1 receptor downregulation and pain-related signaling factor hyperactivity in the cerebellum of FM mice. Moreover, intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of the CB1 agonist AEA replicated the effects of EA, while ICV injection of a CB1 antagonist significantly diminished EA-induced analgesia. This study supports the efficacy of EA for managing FM pain and highlights the CB1 receptor as a major therapeutic target.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

Female C57B/L6 mice (18–20 g, approximately 8–12 weeks old) were purchased from BioLasco Taiwan Co., Ltd. (Yilan, Taiwan) and housed 3 or 4 per cage at an ambient temperature of 25°C and 60% humidity, under a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m.). Sample size calculation indicated that at least nine mice per group were required for alpha = 0.05 and 80% statistical power. All animal experiments were approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee of China Medical University (permit number CMUIACUC-2023-071) and conducted according to the Guide for the Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences Press).

2.2. Modeling Fibromyalgia

Mice were randomly assigned into four groups: a normal control group (normal), an ICS-induced fibromyalgia pain model group (FM), an ICS-induced fibromyalgia pain with 2-Hz EA group (2-Hz EA), and an ICS-induced fibromyalgia pain with sham EA group (sham EA). The fibromyalgia model was induced by exposing individual mice to a 4°C environment for 30 min, followed by a return to 25°C for 30 min each day, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. (6 cycles) for 3 consecutive days. Mice in the normal group were maintained at room temperature throughout this period.

2.3. Electroacupuncture

Mice were first anesthetized using sequential administration of 5% isoflurane for induction and 1% for maintenance. Two 1-inch-long stainless steel acupuncture needles (32G, Taiwan Yuguang Co., Ltd.) were inserted into the bilateral ST36 acupoints (located 3–4 mm below the patella, between the fibula and tibia, anterior to the tibialis anterior muscle). Electrical stimulation was delivered as 150-μs square pulses at a frequency of 2 Hz and an intensity of 1 mA using a Trio 300 stimulator (Ito, Japan). Muscle twitching was observed, but no adverse effects were noted. These EA treatment sessions were conducted on days 3 and 4 following FM model induction. Sham EA were performed as EA without electrical stimulation.

2.4. Mechanical and Thermal Nociception Tests

Mechanical and thermal nociception thresholds were measured on day 0 (before FM modeling) and again on days 3 and 4 after FM modeling. Mice were placed individually in a Plexiglas box (9.5 × 11 × 6.5 cm3) with an iron mesh floor situated within a dark, noise-free room at ~25°C and allowed to habituate for 30 min. Mechanical nociception was then measured by applying a series of von Frey hair to the right hind plantar surface three times, with a 10-min interval between each measurement series (IITC Life Science Inc., USA). Thermal nociception was measured using the Hargreaves test for thermal withdrawal latency. The test was performed in individual Plexiglas enclosures after 30 min of acclimatization. An IITC plantar analgesia instrument (IITC Life, Sciences, SERIES8, model 390G) was used to measure the latency to right hindfoot withdrawal from a radiant heat source placed under a tempered glass plate, directed at the rear area of the paw. Each test was repeated three times for each mouse. The device was programed to stop after 20 s to prevent thermal tissue damage.

2.5. Western Blotting

Cerebellar tissues were excised, placed on ice, and stored at −80°C until protein extraction. Retrieved tissues were homogenized in cold radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.02% NaN3, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (AMRESCO). Total proteins were separated by 8% SDS-Tris glycine gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes for western blotting. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20), then incubated with primary antibody in TBS-T with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-goat antibodies (1:5000). Target protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate kit (PIERCE) and captured on a LAS-3000 Fujifilm imaging system (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd.). The intensities of specific target bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ software (Bethesda, MD, USA) and normalized to the intensity of an internal control band (β-actin or α-tubulin).

2.6. Immunofluorescence

Mice were euthanized under 5% isoflurane and intracardially perfused with normal saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was immediately dissected and post-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 3 days. The tissues were submerged in 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight for cryoprotection, embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Frozen tissue segments were cut into 20-mm sections using a cryostat and placed on glass slides. Sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with a blocking solution consisting of 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.02% sodium azide for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, sections were incubated overnight in saline with 1% BSA containing primary antibodies (1:200, Alomone) against the CB1 receptor and pERK. Tissue sections were then incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), Alexa 594-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-goat IgG (H + L), and peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-mouse IgG (H + L) for 2 h at room temperature, mounted with cover slips, and examined using fluorescence microscopy ().

2.7. CB1 Receptor Agonist and Antagonist Administration

The effects of CB1 agonist and antagonist injections on nociception were examined in adult C57BL/6 female mice (n = 6 per group). The CB1 agonist AEA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered by ICV injection at 100 μM, while the CB1 antagonist AM251 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered ICV injection at 5 µg per mouse in 10 µL of saline under light isoflurane anesthesia (1%).

2.8. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 software. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Group means were compared by analysis of variance followed by post hoc Tukey’s tests for pairwise comparisons. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Attenuation of Intermittent Cold Stress-Induced Fibromyalgia-Like Pain by Electroacupuncture

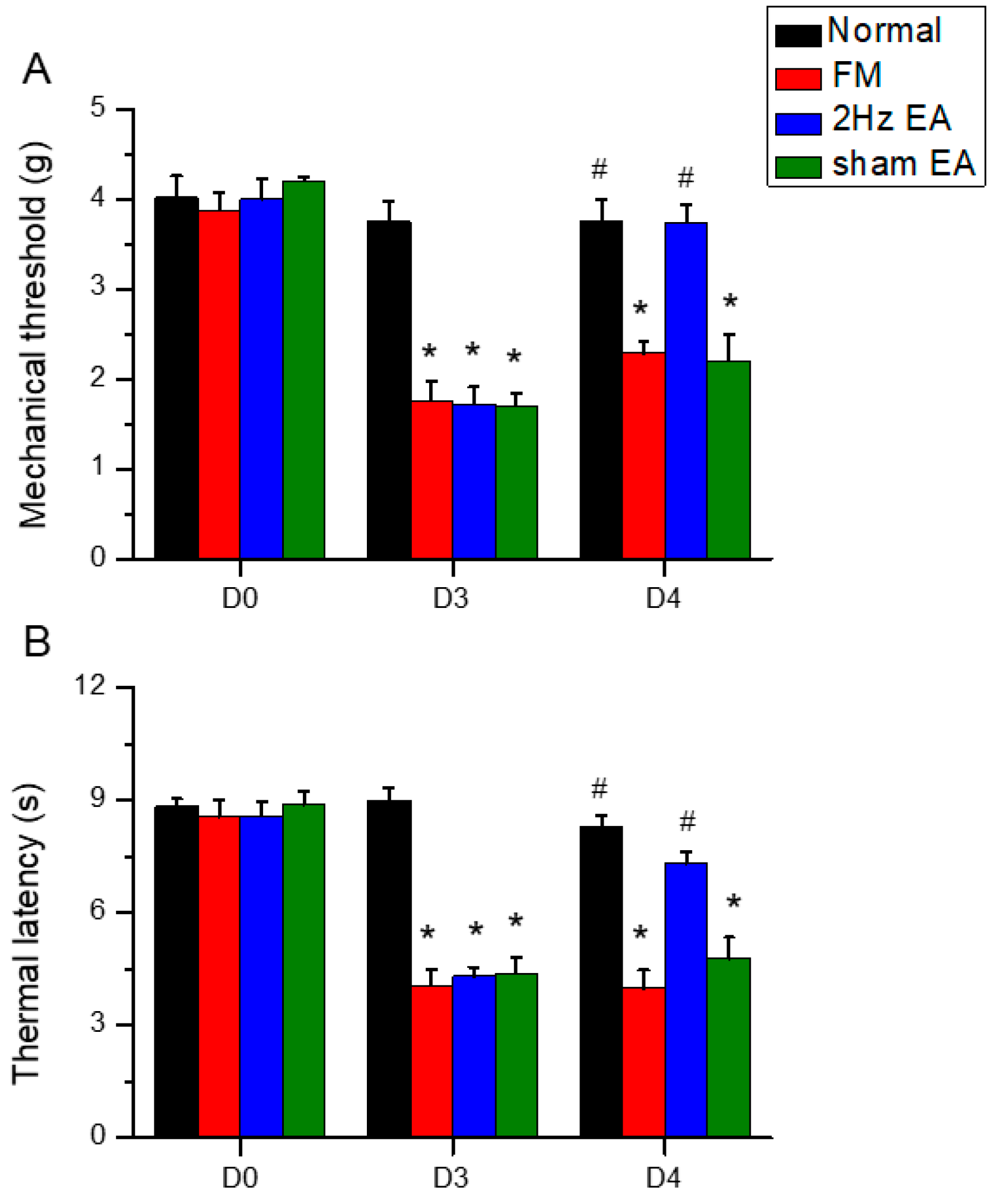

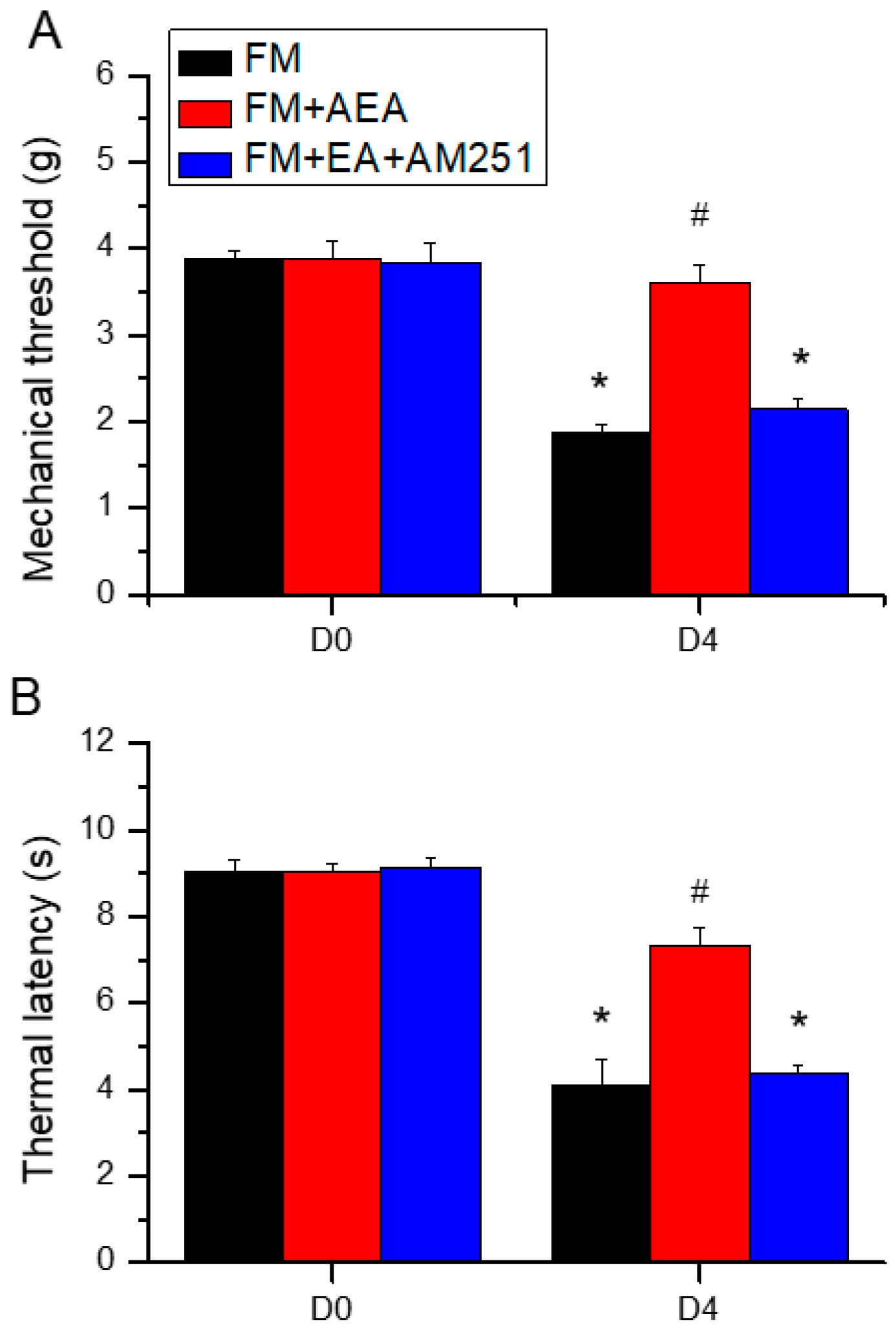

We first examined whether 2-Hz EA could significantly attenuate mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in FM model mice during the initial transition from acute to chronic pain (the subacute phase). To confirm successful induction of the FM model, we compared von Frey hair responses and Hargraves thermal withdrawal responses between ICS-exposed and ICS-unexposed mice. Both mechanical pain thresholds (

Figure 1A, red column, day 4: 2.29 ± 0.13 g, n = 9) and thermal pain withdrawal latencies (

Figure 1B, red column, day 4: 4.01 ± 0.47 g, n = 9) were significantly lower in model mice. Bilateral 2-Hz EA reliably increased mechanical pain thresholds (reduced mechanical hyperalgesia:

Figure 1A, blue column, day 4: 3.74 ± 0.19 g, n = 9) and prolonged thermal latency (reduced thermal hyperalgesia:

Figure 1B, blue column, day 4: 7.33 ± 0.3 g, n = 9), while sham EA had no effect, consistent with our previous studies.

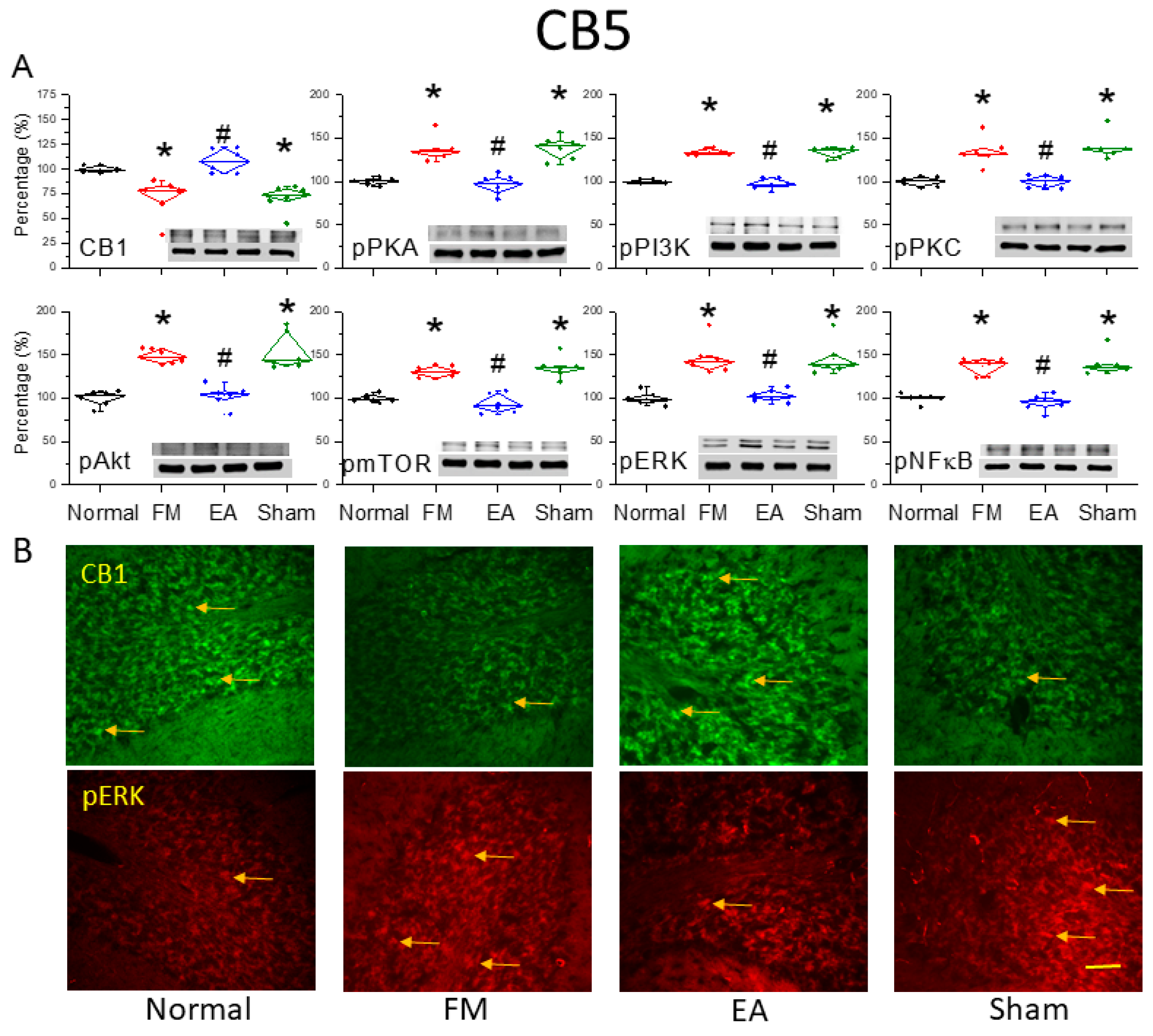

3.2. Reduced Expression of CB1 and Enhanced Activation of Pain-Related Signaling Factors in the Cerebellar C5 Region of FM Model Mice Were Reversed by 2-Hz EA

Western blotting of cerebellar lysates harvested from the four treatment groups (normal, FM, FM + 2-Hz EA, FM + sham EA) revealed reduced expression of CB1 receptors (Fig 2A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6) and increased expression of phosphorylated (activated) PKA (pPKA) in the CB5 region of FM model mice (

Figure 2A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6) compared to normal controls. However, 2-Hz EA but not sham EA dramatically reversed these expression changes (

Figure 2A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Similarly, expression levels of pPI3K and pPKC were elevated in the CB5 region of FM mice (

Figure 2A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), and these changes were reversed by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA (

Figure 2A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Phosphorylation levels of the downstream kinases pAkt and pmTOR were also higher in the FM group compared to the normal control group (

Figure 2A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), and 2-Hz EA but not sham EA reliably downregulated pAkt and pmTOR expression (

Figure 2A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Additionally, pERK expression was significantly increased in the CB5 region of FM mice (

Figure 2A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6) and was reversed by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA (

Figure 2A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). The transcription factor pNF-κB, a major mediator of stress responses, was also upregulated in FM mice and downregulated by 2-Hz EA (

Figure 2A, n = 6). These results suggest that the observed antinociceptive effects of 2-Hz EA are mediated by reduced ICS-induced kinase–pNF-κB signaling and concomitant suppression of target genes involved in hyperalgesia. Western blot results were further supported by immunohistochemistry of cerebellar tissues harvested from the four treatment groups (Figure. 2B). ICS-induced FM reduced CB1 receptor immunoexpression in CB5, while 2-Hz EA but not sham EA reversed this effect on CB1 receptor expression. Similarly, increased pERK immunoexpression in the FM group was reversed by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA.

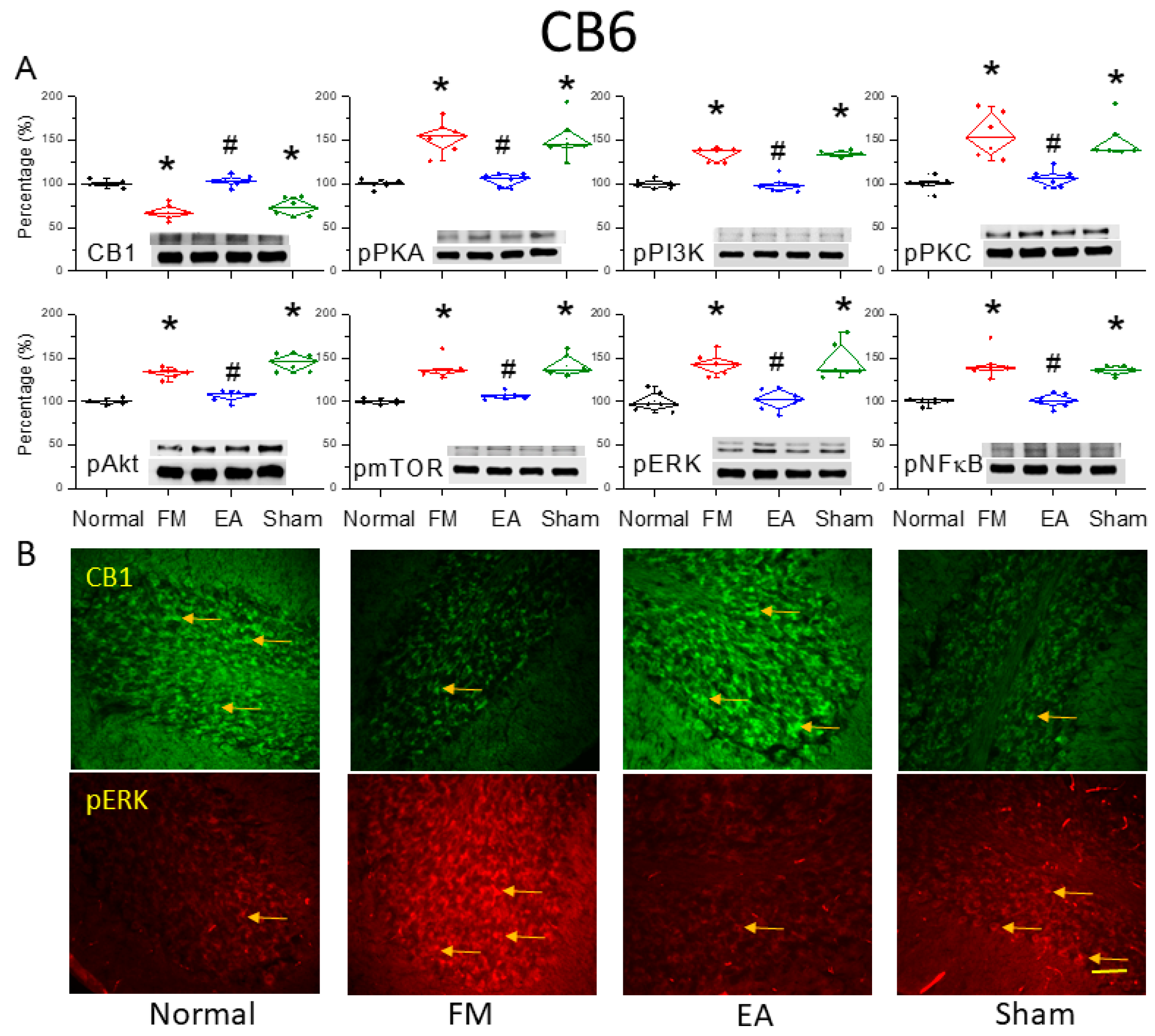

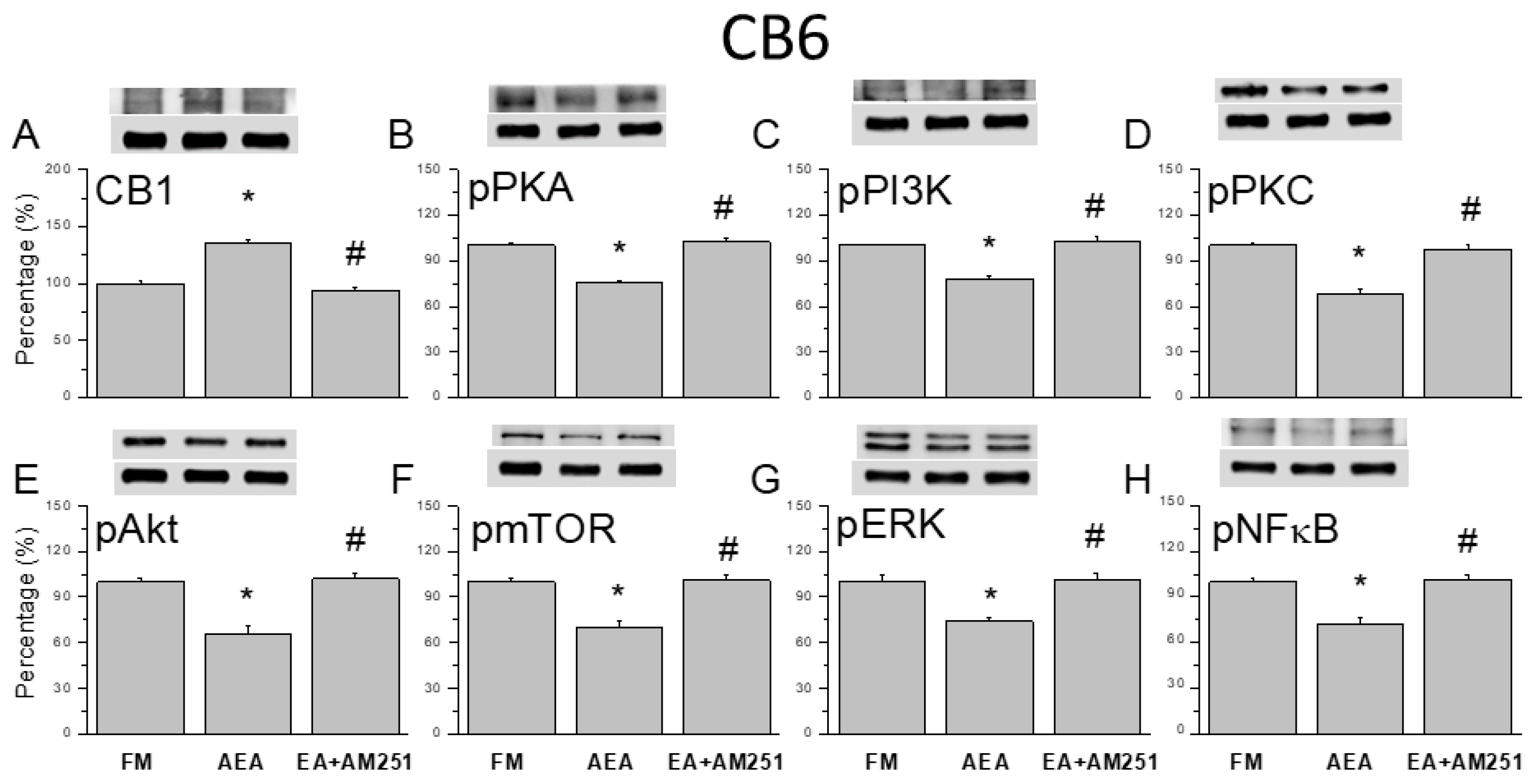

3.3. Reversal of CB1 Receptor Downregulation and ERK Upregulation in the Cerebellar CB6 Region by 2-Hz EA

We also examined whether 2-Hz EA reversed CB1 receptor downregulation in the CB6 region, a crucial region mediating FM-associated pain. After 4 days of ICS, CB6 tissues were collected and processed for western blotting of CB1 and related kinases. Consistent with results in CB5, CB1 receptor expression was downregulated in CB6 after ICS (

Figure 3A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), while 2-Hz EA but not sham EA for 2 continuous days significantly reversed this effect (

Figure 3A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Augmented pPKA, pPI3K and pPKC were also found in the CB6 region of FM model mice (

Figure 3A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6) compared to normal controls. Though, 2-Hz EA but not sham EA intensely reversed these expression changes (

Figure 3A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Similarly, expression levels of pAkt and pmTOR were also higher in the FM group compared to the normal control group (

Figure 3A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), and 2-Hz EA but not sham EA consistently attenuated pAkt and pmTOR expression (

Figure 3A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). As well, pERK expression was meaningfully augmented in the CB6 region of FM mice (

Figure 3A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6) and was diminished by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA (

Figure 3A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). The transcription factor pNF-κB was also increased in FM mice and alleviated by 2-Hz EA (

Figure 3A, n = 6). Immunohistochemical staining confirmed reduced CB1 receptor labeling in the FM and FM + sham EA groups compared to controls, while CB1 receptor immunoexpression levels were substantially higher in the FM + 2-Hz EA group. Similar results were observed for pERK expression, which was reduced in FM and FM + sham EA groups but reversed by 2-Hz EA.

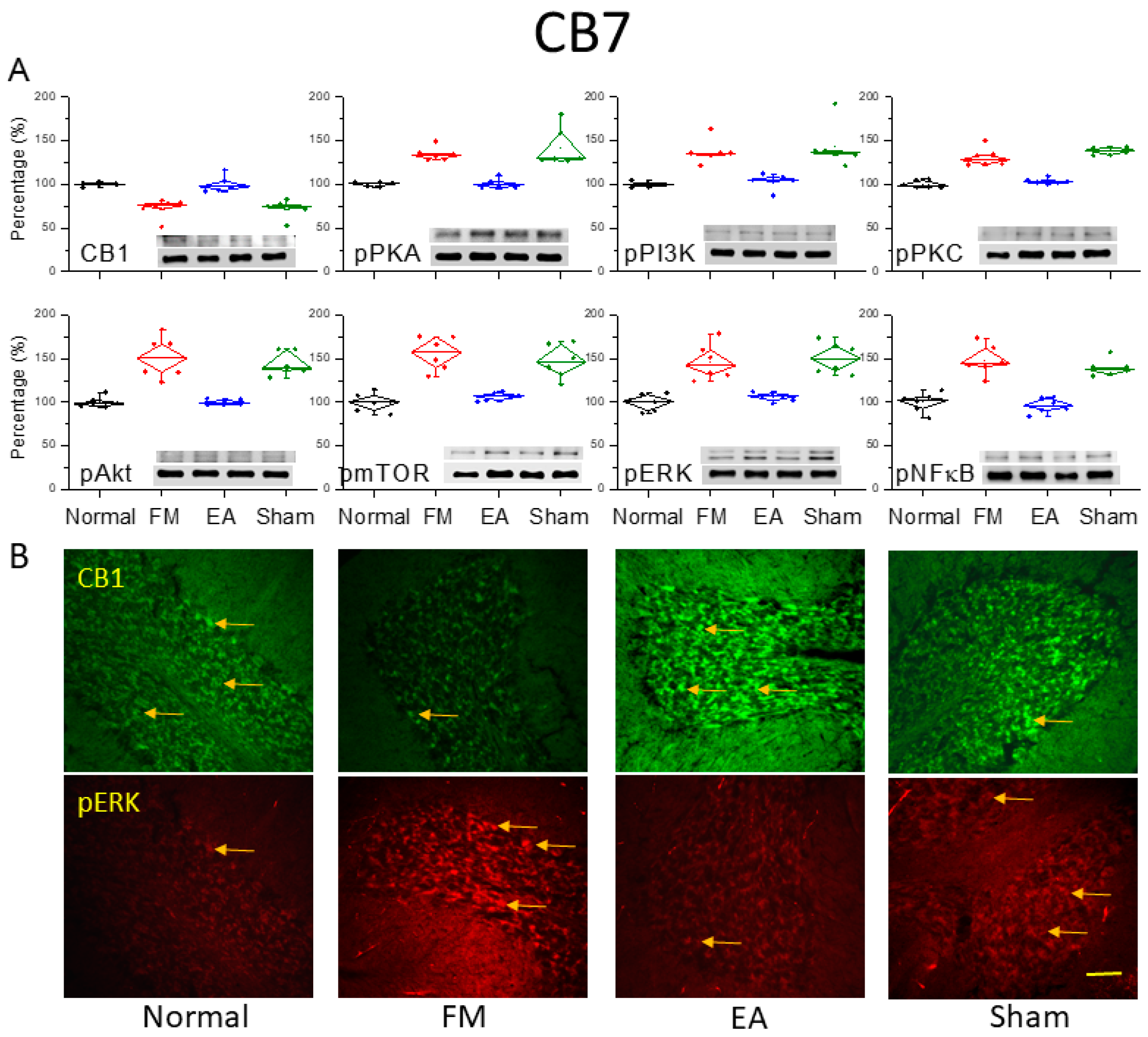

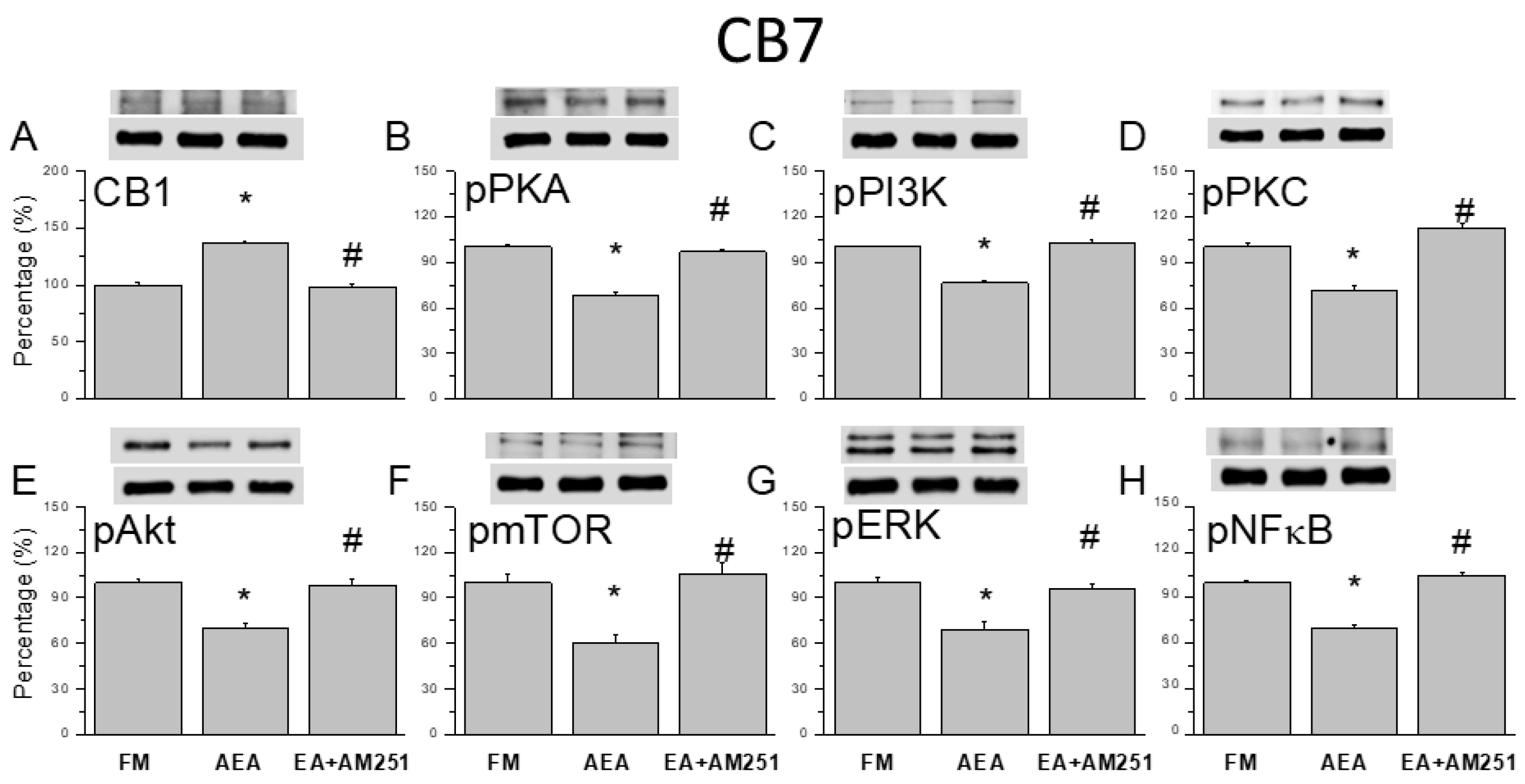

3.4 Reversal of CB1 Receptor Downregulation and Pain-Associated Kinase Upregulation by 2-Hz EA in the Cerebellar CB7 Region

After the final behavioral examinations on day 4, we dissected the CB7 region from all groups to assess protein expression levels using western blotting and immunofluorescence (Figure. 4). ICS induction significantly decreased CB1 receptor expression in CB7 on day 4 (

Figure 4A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6). However, 2-Hz EA but not sham EA augmented CB1 receptor expression in ICS-exposed mice (

Figure 4A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). In addition, pPKA, pPI3K, and pPKC levels were consistently elevated in ICS-exposed mice (

Figure 4A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), and these effects were diminished by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA (

Figure 4A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Similar to aforementioned areas, the expression levels of pAkt, pmTOR, and pERK were significantly greater in ICS-initiated FM mice than in control mice (

Figure 4A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), and these effects were reversed by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA (

Figure 4A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Induction of the FM-like condition also increased pNF-κB expression in the CB7, consistent with a critical role for this area in FM pain development (

Figure 4A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6). This effect was reversed by 2-Hz EA but not sham EA (

Figure 4A,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). In agreement with western blotting, immunofluorescence staining (

Figure 4B) revealed reduced CB1 immunoexpression and increased pERK immunoexpression in the FM and FM + sham EA groups compared to controls, with reversal of these effects by 2-Hz EA.

3.5. ICV Injection of a CB1 Agonist Reversed ICS-Induced Hyperalgesia, While a CB1 Antagonist Blocked the Analgesic Effect of 2-Hz EA

Before ICS induction, there were no substantial differences in responses to mechanical or thermal stimulation. In ICS-treated FM mice, mechanical thermal hypersensitivity were observed, as previously described. Both mechanical (

Figure 5A, red column, day 4: 3.61 ± 0.21 g, n = 9) and thermal hyperalgesia (

Figure 5B, red column, day 4: 7.35 ± 0.4 s, n = 9) were significantly diminished by ICV injection of the CB1 agonist AEA, indicating that CB1 receptor stimulation alone can recapitulate the analgesic effects of 2-Hz EA. Moreover, the analgesic effect of 2-Hz EA was abolished by ICV injection of the CB1 antagonist AM251 (

Figure 5A & B, blue column, day 4: mechanical, 2.14 ± 0.13 g & thermal, 4.4 ± 0.14 s, n = 9). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that the antinociceptive effects of 2-Hz EA are mediated by activation of central CB1 receptors.

3.6. ICV Injection of a CB1 Agonist Reversed ICS-Induced CB1 Receptor Downregulation and Upregulation of Nociceptive Signaling Factors in All Three Cerebellar Regions

Following assessment of CB1 agonist and 2-Hz EA with antagonist effects on ICS-induce hyperalgesia, we performed western blotting to examine the corresponding changes in CB1 receptor and nociceptive signaling molecule expression levels in cerebellar regions CB5, CB6, and CB7. Surprisingly, downregulation of the CB1 receptor following FM modeling was reversed by ICV injection of the agonist AEA in CB5, CB6, and CB7 (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8A, *

P < 0.05, n = 6). Conversely, ICV injection of the antagonist AM251 reversed upregulation of the CB1 receptor. Additionally, AEA injection reversed ICS-induced upregulation of pPKA, pPI3K, and pPKC (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, B-D, *

P < 0.05, n = 6), while ICV injection of the CB1 antagonist AM251 reversed the analgesic effects of 2-Hz EA (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, B-D,

#P < 0.05, n = 6). Qualitatively similar results were observed for the downstream nociceptive signaling factors pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB. Expression levels were downregulated in all cerebellar regions examined by ICV injection of AEA (

Figure 6, n = 6).

4. Discussion

A recent clinical trial demonstrated the efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) for reducing FM pain and improving patients’ quality of life. Particularly, two-thirds of FM patients in the rTMS group reported at least a 30% reduction in their visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores, and the entire rTMS treatment group demonstrated a significant time × group interaction in VAS scores from baseline to follow-up. These effects were observed after only three sessions of rTMS over the DLPFC [

26]. Thus, various forms of electrical stimulation appear to reduce subjective FM-associated pain. Wang et al. reported that cannabis-based medicinal products improved sleep, anxiety, and quality of life in 306 FM patients from the UK medical cannabis registry [

27]. Although the precise etiology of FM remains unclear, traumatic experiences may be a common precipitating factor. Mir´o et al. reported a higher incidence of traumatic experiences in FM patients, along with more PTSD-like symptoms compared to healthy controls, including insomnia, anxiety, depression, and functional impairment [

28].

Recently, Mazza et al. reported that cannabis improved FM symptoms in patients resistant to currently pharmacological therapies, as measured by the numerical rating scale, Oswestry disability index, hospital anxiety and depression scale, widespread pain index, severity score, and side effects evaluation [

29]. This further supports the potential of targeting CB1 receptors in FM therapy. Similarly, Sagy et al. found that medical cannabis was safe and effective for the treatment of FM symptoms, with side effects including dizziness, dry mouth, and gastrointestinal symptoms [

30]. A recent study also reported that the myofascial technique reduced pain, central sensitization, and negative emotional symptoms while improving sleep quality among FM patients [

31]. Similarly, Martínez-Pozas et al. observed reduced mechanical hyperalgesia in chronic musculoskeletal pain patients following orthopedic manual therapy [

32]. While additional studies are required to assess the contributions of cannabinoid receptor signaling to these effects, our findings align with these reports, particularly regarding the potential therapeutic role of cannabinoid receptor activation in FM management. Albrecht et al. provided compelling in vivo evidence that microglial activation in the anterior and posterior middle cingulate cortices contributes to the onset of FM, as indicated by upregulation of the glial activation marker translocator protein (TSPO) [

33]. Herein, we report that CB1 receptor activation, either through EA or AEA, significantly relieved FM pain and reversed the upregulation of related nociceptive protein kinases in the cerebellum of FM model mice. Further, this response was recapitulated by CB1 agonist injection and blocked by CB1 antagonist injection, suggesting that CB1 receptor signaling in the cerebellum plays an important therapeutic role in FM. Clinical trials are warranted to facilitate the translation of this strategy into medical practice.

Kawamura et al. combined electrophysiological with immunofluorescence analyses to demonstrate that the CB1 receptor is the main cannabinoid receptor at presynaptic excitatory synapses in the mouse cerebellum. Moreover, CB-dependent inhibition of excitatory transmission at cerebellar Purkinje cells was abolished in

Cb1−/− mice, which exhibited very low CB1 expression as confirmed by immunochemical staining [

34]. A recent study also reported that endogenous cannabinoids can relieve inflammatory and neuropathic pain by stimulating CB1 and CB2 receptors, respectively, further supporting cannabinoids as promising analgesic agents. Accordingly, CB1 analogs, CB2 analogs, and modulators of various CB biosynthetic and catabolic enzymes are currently under development as treatments. Consistent with the current findings, CB1 receptor agonists and inhibitors of endocannabinoid catalytic enzymes have yielded consistent analgesic effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models, although FM mouse models were not specifically examined. Nonetheless, such compounds have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating cancer, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain [

35], strongly suggesting their therapeutic potential in FM management. Fanton et al. reported a positive relationship between anti-satellite glia cell IgG expression and FM severity. In addition, FM patients with high serum anti-SGC IgG concentrations exhibited pain-associated glial activation in the thalamus and rostral anterior cingulate cortex. Taken together, these results suggest that anti-SGC IgG levels is a useful diagnostic and prognostic tool for FM, potentially leading to novel antibody-based treatments [

36].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that ICS can induce fibromyalgia-like mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in mice by suppressing CB1 receptor signaling and promoting nociceptive signaling in cerebellar CB5-7 regions. Furthermore, both the hyperalgesic and molecular effects of ICS were reversed by 2-Hz electroacupuncture (but not sham EA). These results provide strong support for the therapeutic utility of EA and other strategies that induce endocannabinoid signaling in the cerebellum for the management of FM.

Author Contributions

HC Lin, HY Liao, and HC Hsu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Investigation. KT Chuang and YW Lin: Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: NSTC 113-2314-B-039-047, CMUHCH-CMU-113-003, and the "Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University" from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest for all authors.

References

- Andres-Rodriguez, L.; Borras, X.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Perez-Aranda, A.; Angarita-Osorio, N.; Moreno-Peral, P.; Montero-Marin, J.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; Carvalho, A.F.; Maes, M.; et al. Peripheral immune aberrations in fibromyalgia: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocyigit, B.F.; Akyol, A. Fibromyalgia syndrome: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Reumatologia 2022, 60, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, D.S.; Forsberg, A.; Sandstrom, A.; Bergan, C.; Kadetoff, D.; Protsenko, E.; Lampa, J.; Lee, Y.C.; Hoglund, C.O.; Catana, C.; et al. Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia - A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 75, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyorfi, M.; Rupp, A.; Abd-Elsayed, A. Fibromyalgia Pathophysiology. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosek, E.; Martinsen, S.; Gerdle, B.; Mannerkorpi, K.; Lofgren, M.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Fransson, P.; Schalling, M.; Ingvar, M.; Ernberg, M.; et al. The translocator protein gene is associated with symptom severity and cerebral pain processing in fibromyalgia. Brain Behav Immun 2016, 58, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, M.S.; Nass, S.R.; Gabella, K.M.; Kinsey, S.G. The endocannabinoid system modulates stress, emotionality, and inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2014, 42, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecha, M.; Feliu, A.; Carrillo-Salinas, F.J.; Rueda-Zubiaurre, A.; Ortega-Gutierrez, S.; de Sola, R.G.; Guaza, C. Endocannabinoids drive the acquisition of an alternative phenotype in microglia. Brain Behav Immun 2015, 49, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluny, N.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Sharkey, K.A. Cannabinoid signalling regulates inflammation and energy balance: the importance of the brain-gut axis. Brain Behav Immun 2012, 26, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, D.A.; Yudowski, G.A. Cannabinoid Receptors in the Central Nervous System: Their Signaling and Roles in Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2016, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lopez-Alcalde, J.; Zhang, L.; Siebenhuner, A.R.; Witt, C.M.; Barth, J. Acupuncture for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 12504–12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, B.; Erwood, K.; Ncomanzi, S.; Fischer, V.; O'Brien, D.; Lee, A. Management strategies for adult patients with dental anxiety in the dental clinic: a systematic review. Aust Dent J 2022, 67 Suppl 1, S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Ge, J.; Liu, S. The immunomodulatory mechanisms for acupuncture practice. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1147718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.; Cheng, C.M.; Yen, C.M.; Lin, Y.W. Paper-Based Detection Device for Microenvironment Examination: Measuring Neurotransmitters and Cytokines in the Mice Acupoint. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.W.; Chou, A.I.W.; Su, H.; Su, K.P. Transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) modulates the therapeutic effects for comorbidity of pain and depression: The common molecular implication for electroacupuncture and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 89, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.Y.; Hsieh, C.L.; Huang, C.P.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Attenuates CFA-induced Inflammatory Pain by suppressing Nav1.8 through S100B, TRPV1, Opioid, and Adenosine Pathways in Mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.Y.; Hsieh, C.L.; Huang, C.P.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Attenuates Induction of Inflammatory Pain by Regulating Opioid and Adenosine Pathways in Mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 15679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I.H.; Yen, C.M.; Hsu, H.C.; Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Chemogenetics Modulation of Electroacupuncture Analgesia in Mice Spared Nerve Injury-Induced Neuropathic Pain through TRPV1 Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.T.; Yang, C.C.; Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Reduces Fibromyalgia Pain via Neuronal/Microglial Inactivation and Toll-like Receptor 4 in the Mouse Brain: Precise Interpretation of Chemogenetics. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.W.; Hsieh, C.L.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.W. Effects of electroacupuncture in a mouse model of fibromyalgia: role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and related mechanisms. Acupunct Med 2017, 35, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hsieh, C.L.; Lin, Y.W. Role of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 in Electroacupuncture Analgesia on Chronic Inflammatory Pain in Mice. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 5068347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghowsi, M.; Qalekhani, F.; Farzaei, M.H.; Mahmudii, F.; Yousofvand, N.; Joshi, T. Inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and hypertension as mediators for adverse effects of obesity on the brain: A review. Biomedicine (Taipei) 2021, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Effects and Mechanisms of Electroacupuncture on Chronic Inflammatory Pain and Depression Comorbidity in Mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020, 2020, 4951591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Electroacupuncture Attenuates Chronic Inflammatory Pain and Depression Comorbidity through Transient Receptor Potential V1 in the Brain. Am J Chin Med 2021, 49, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inprasit, C.; Lin, Y.W. TRPV1 Responses in the Cerebellum Lobules V, VIa and VII Using Electroacupuncture Treatment for Inflammatory Hyperalgesia in Murine Model. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.C.; Hsieh, C.L.; Wu, S.Y.; Lin, Y.W. Toll-like receptor 2 plays an essential role in electroacupuncture analgesia in a mouse model of inflammatory pain. Acupunct Med 2019, 37, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forogh, B.; Haqiqatshenas, H.; Ahadi, T.; Ebadi, S.; Alishahi, V.; Sajadi, S. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) versus transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in the management of patients with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Neurophysiol Clin 2021, 51, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Erridge, S.; Holvey, C.; Coomber, R.; Usmani, A.; Sajad, M.; Guru, R.; Holden, W.; Rucker, J.J.; Platt, M.W.; et al. Assessment of clinical outcomes in patients with fibromyalgia: Analysis from the UK Medical Cannabis Registry. Brain Behav 2023, 13, e3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miro, E.; Martinez, M.P.; Sanchez, A.I.; Caliz, R. Clinical Manifestations of Trauma Exposure in Fibromyalgia: The Role of Anxiety in the Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Fibromyalgia Status. J Trauma Stress 2020, 33, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M. Medical cannabis for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: a retrospective, open-label case series. J Cannabis Res 2021, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagy, I.; Bar-Lev Schleider, L.; Abu-Shakra, M.; Novack, V. Safety and Efficacy of Medical Cannabis in Fibromyalgia. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas-Yague, E.; Martinez-Pozas, O.; Gozalo-Pascual, R.; Munoz Blanco, E.; Lopez Panos, R.; Jimenez-Ortega, L.; Cuenca-Zaldivar, J.N.; Sanchez Romero, E.A. Comparative effectiveness of Maitland Spinal Mobilization versus myofascial techniques on pain and symptom severity in women with Fibromyalgia syndrome: A quasi-randomized clinical trial with 3-month follow up. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2024, 73, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Pozas, O.; Sanchez-Romero, E.A.; Beltran-Alacreu, H.; Arribas-Romano, A.; Cuenca-Martinez, F.; Villafane, J.H.; Fernandez-Carnero, J. Effects of Orthopedic Manual Therapy on Pain Sensitization in Patients With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: An Umbrella Review With Meta-Meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2023, 102, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, D.S.; Forsberg, A.; Sandstrom, A.; Bergan, C.; Kadetoff, D.; Protsenko, E.; Lampa, J.; Lee, Y.C.; Hoglund, C.O.; Catana, C.; et al. Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia - A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 75, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, Y.; Fukaya, M.; Maejima, T.; Yoshida, T.; Miura, E.; Watanabe, M.; Ohno-Shosaku, T.; Kano, M. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is the major cannabinoid receptor at excitatory presynaptic sites in the hippocampus and cerebellum. J Neurosci 2006, 26, 2991–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donvito, G.; Nass, S.R.; Wilkerson, J.L.; Curry, Z.A.; Schurman, L.D.; Kinsey, S.G.; Lichtman, A.H. The Endogenous Cannabinoid System: A Budding Source of Targets for Treating Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanton, S.; Menezes, J.; Krock, E.; Sandstrom, A.; Tour, J.; Sandor, K.; Jurczak, A.; Hunt, M.; Baharpoor, A.; Kadetoff, D.; et al. Anti-satellite glia cell IgG antibodies in fibromyalgia patients are related to symptom severity and to metabolite concentrations in thalamus and rostral anterior cingulate cortex. Brain Behav Immun 2023, 114, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (elevated pain thresholds) in a mouse model of fibromyalgia (FM) induced by intermittent cold stress (ICS) was reversed by electroacupuncture (EA). (A) Mechanical pain threshold in normal control, FM, FM with 2-Hz EA (2-Hz EA), and FM with sham EA (sham EA) groups as measured by von Frey filament tests. (B) Thermal pain thresholds in the same groups as measured using Hargreaves test for thermal withdrawal latency. Pain thresholds were reduced by ICS and this hyperalgesia was completely reversed by 2-Hz FM but not sham FM. * P < 0.05 compared to the normal group. # P < 0.05 compared to the FM group. n = 9.

Figure 1.

Mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (elevated pain thresholds) in a mouse model of fibromyalgia (FM) induced by intermittent cold stress (ICS) was reversed by electroacupuncture (EA). (A) Mechanical pain threshold in normal control, FM, FM with 2-Hz EA (2-Hz EA), and FM with sham EA (sham EA) groups as measured by von Frey filament tests. (B) Thermal pain thresholds in the same groups as measured using Hargreaves test for thermal withdrawal latency. Pain thresholds were reduced by ICS and this hyperalgesia was completely reversed by 2-Hz FM but not sham FM. * P < 0.05 compared to the normal group. # P < 0.05 compared to the FM group. n = 9.

Figure 2.

Downregulation of the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor and upregulation of pain-associated signaling factors by ICS and reversal by 2-Hz EA in the cerebellar CB5 region. (A) Densitometric analysis of target protein bands (CB1, pPKA, pPI3K, pPKC, pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB) on western blots of cerebellar tissues from normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + sham EA group mice. * P < 0.05 vs. the normal group, # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of cerebellar CB5 slices from the same groups showing CB1 (green) and pERK (red) immunofluorescence. Yellow arrows indicate immune-positive signals. Bar = 100 μm. Typical results for n = 3 mice per group.

Figure 2.

Downregulation of the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor and upregulation of pain-associated signaling factors by ICS and reversal by 2-Hz EA in the cerebellar CB5 region. (A) Densitometric analysis of target protein bands (CB1, pPKA, pPI3K, pPKC, pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB) on western blots of cerebellar tissues from normal, FM, FM + EA, and FM + sham EA group mice. * P < 0.05 vs. the normal group, # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of cerebellar CB5 slices from the same groups showing CB1 (green) and pERK (red) immunofluorescence. Yellow arrows indicate immune-positive signals. Bar = 100 μm. Typical results for n = 3 mice per group.

Figure 3.

Downregulation of the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor and upregulation of pain-associated signaling factors by ICS and reversal by 2-Hz EA in the cerebellar CB6 region. (A) Densitometric analysis of target protein bands (CB1, pPKA, pPI3K, pPKC, pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB). * P < 0.05 vs. the normal group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group. (B) Immunofluorescence intensities of CB1 (green) and pERK (red) in the mouse CB6 region. Yellow arrows indicate immune-positive signals. Bar = 100 μm. Typical results for n = 3 mice per group.

Figure 3.

Downregulation of the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor and upregulation of pain-associated signaling factors by ICS and reversal by 2-Hz EA in the cerebellar CB6 region. (A) Densitometric analysis of target protein bands (CB1, pPKA, pPI3K, pPKC, pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB). * P < 0.05 vs. the normal group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group. (B) Immunofluorescence intensities of CB1 (green) and pERK (red) in the mouse CB6 region. Yellow arrows indicate immune-positive signals. Bar = 100 μm. Typical results for n = 3 mice per group.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor and upregulation of pain-associated signaling factors by ICS and reversal by 2-Hz EA in the cerebellar CB7 region. (A) Densitometric analysis of target protein bands (CB1, pPKA, pPI3K, pPKC, pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB). * P < 0.05 vs. the normal group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group. (B) Immunofluorescence intensities of CB1 (green) and pERK (red) in the mouse CB7 region. Yellow arrows indicate immune-positive signals. Bar = 100 μm. Typical results from n = 3 mice per group.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of the cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor and upregulation of pain-associated signaling factors by ICS and reversal by 2-Hz EA in the cerebellar CB7 region. (A) Densitometric analysis of target protein bands (CB1, pPKA, pPI3K, pPKC, pAkt, pmTOR, pERK, and pNF-κB). * P < 0.05 vs. the normal group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group. (B) Immunofluorescence intensities of CB1 (green) and pERK (red) in the mouse CB7 region. Yellow arrows indicate immune-positive signals. Bar = 100 μm. Typical results from n = 3 mice per group.

Figure 5.

Recapitulation of EA-induced analgesia by intracerebroventricular injection of a CB1 agonist and blockade of EA-induced analgesia by a CB1 antagonist in FM model mice. (A) Mechanical thresholds and (B) thermal latency thresholds of FM group mice (black bars), FM mice treated with the CB1 agonist AEA (red bars), and FM mice receiving EA with the CB1 antagonist AM251 (blue bars). * P < 0.05 vs. baseline. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 9 mice per group.

Figure 5.

Recapitulation of EA-induced analgesia by intracerebroventricular injection of a CB1 agonist and blockade of EA-induced analgesia by a CB1 antagonist in FM model mice. (A) Mechanical thresholds and (B) thermal latency thresholds of FM group mice (black bars), FM mice treated with the CB1 agonist AEA (red bars), and FM mice receiving EA with the CB1 antagonist AM251 (blue bars). * P < 0.05 vs. baseline. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. Mean ± SEM of n = 9 mice per group.

Figure 6.

Effects of the CB1 agonist and antagonist on expression levels of CB1 and associated signaling factors in the cerebellar CB5 region. Expression levels were compared among FM, FM + AEA, FM + EA + AM251 groups by western blot. (A–H) Densitometric analyses of (A) CB1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, and (H) pNF-kB expression. * P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM + AEA group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group.

Figure 6.

Effects of the CB1 agonist and antagonist on expression levels of CB1 and associated signaling factors in the cerebellar CB5 region. Expression levels were compared among FM, FM + AEA, FM + EA + AM251 groups by western blot. (A–H) Densitometric analyses of (A) CB1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, and (H) pNF-kB expression. * P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM + AEA group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group.

Figure 7.

Effects of the CB1 agonist and antagonist on expression levels of CB1 and associated signaling factors in the cerebellar CB6 region. Expression levels were compared among FM, FM + AEA, FM + EA + AM251 groups by western blot. (A–H) Densitometric analyses of (A) CB1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, and (H) pNF-kB expression. * P < 0.05 vs. the FM group and # P < 0.05 vs. the FM + AEA group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group.

Figure 7.

Effects of the CB1 agonist and antagonist on expression levels of CB1 and associated signaling factors in the cerebellar CB6 region. Expression levels were compared among FM, FM + AEA, FM + EA + AM251 groups by western blot. (A–H) Densitometric analyses of (A) CB1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, and (H) pNF-kB expression. * P < 0.05 vs. the FM group and # P < 0.05 vs. the FM + AEA group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group.

Figure 8.

Effects of the CB1 agonist and antagonist on expression levels of CB1 and associated signaling factors in the cerebellar CB7 region. Expression levels were compared among FM, FM + AEA, FM + EA + AM251 groups by western blot. (A–H) Densitometric analyses of (A) CB1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, and (H) pNF-kB expression. * P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM + AEA group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group.

Figure 8.

Effects of the CB1 agonist and antagonist on expression levels of CB1 and associated signaling factors in the cerebellar CB7 region. Expression levels were compared among FM, FM + AEA, FM + EA + AM251 groups by western blot. (A–H) Densitometric analyses of (A) CB1, (B) pPKA, (C) pPI3K, (D) pPKC, (E) pAkt, (F) pmTOR, (G) pERK, and (H) pNF-kB expression. * P < 0.05 vs. the FM group. # P < 0.05 vs. the FM + AEA group. Mean ± SEM of n = 6 mice per group.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).