Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Mice and FM Pain Initiation

Electroacupuncture

Nociceptive Behavior Tests

Western Blot

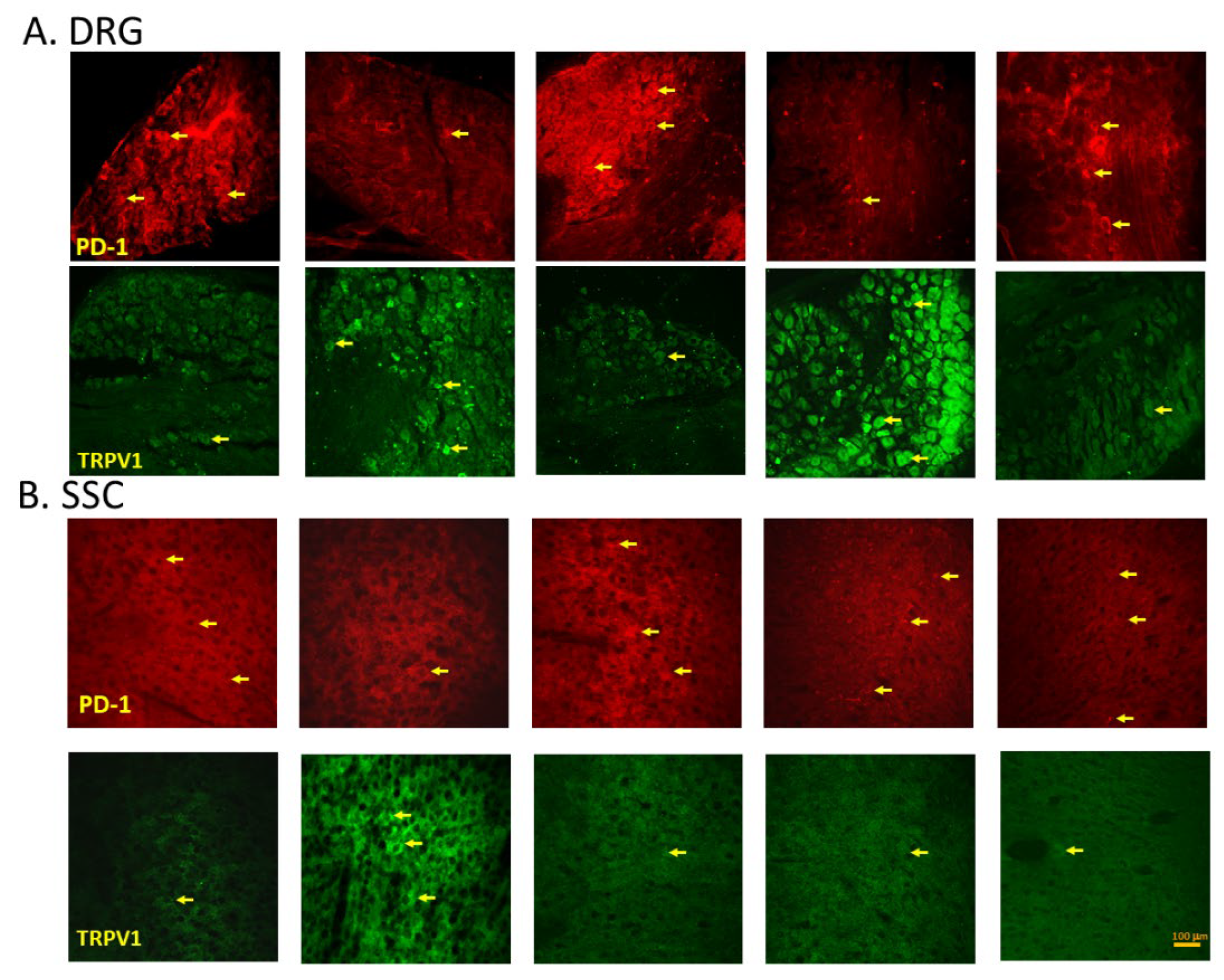

Immunofluorescence

Intracerebroventricular Injection

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

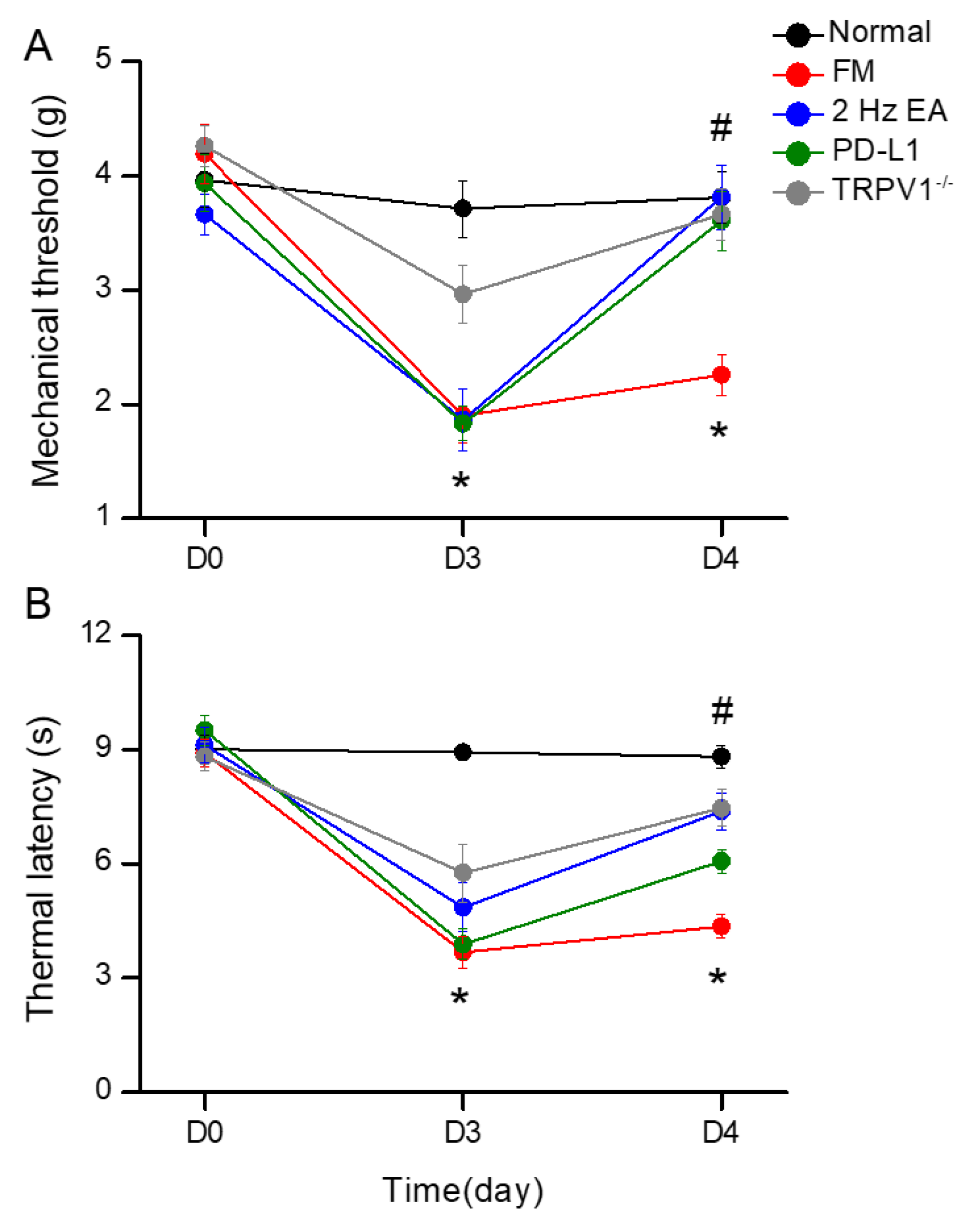

EA, PD-L1 Injection, or Trpv1 Deletion Care for FM Pain in a Mouse Model

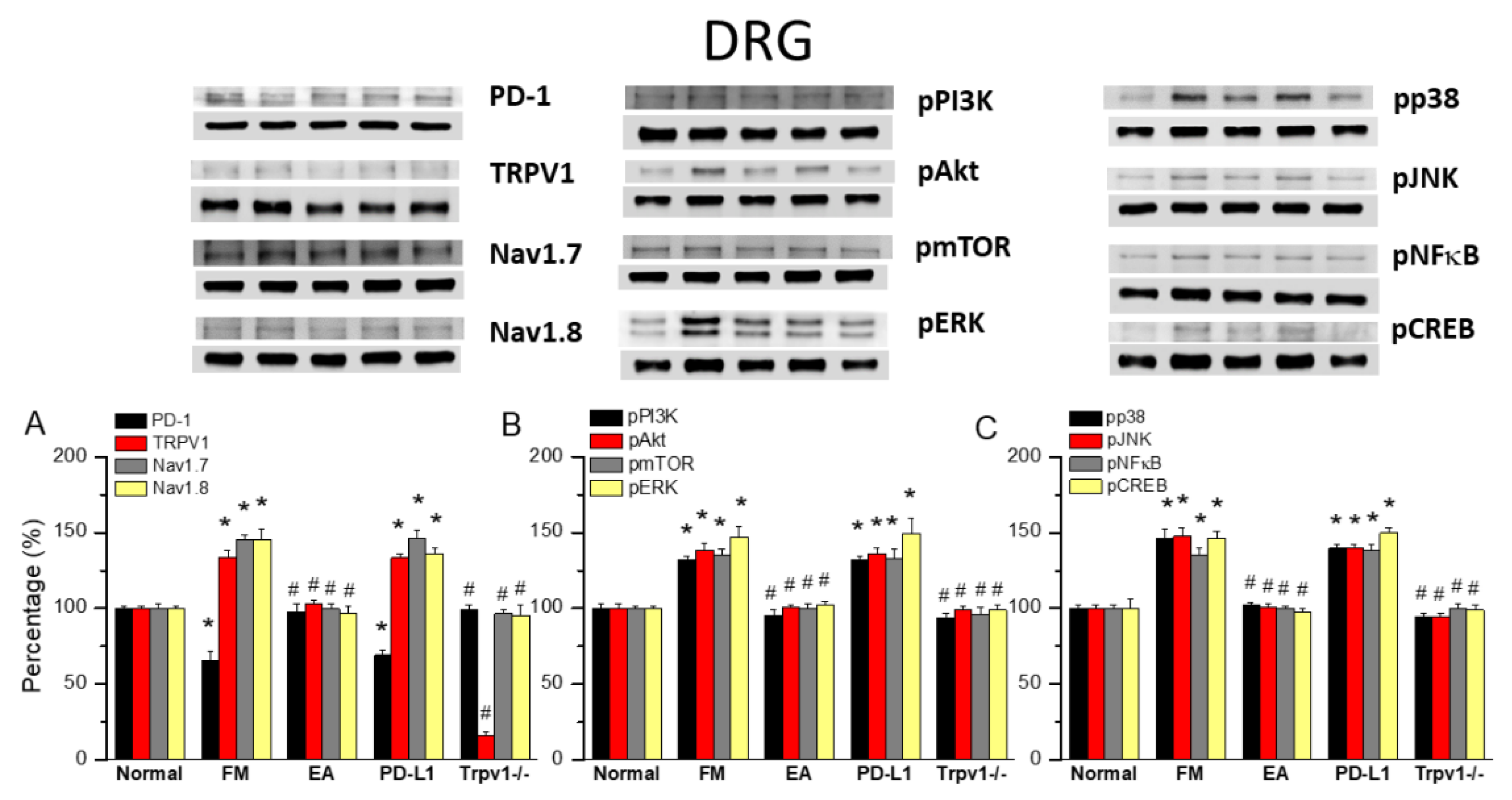

EA Controlled PD1-TRPV1 Pain Signaling in the Peripheral DRG of FM Mice

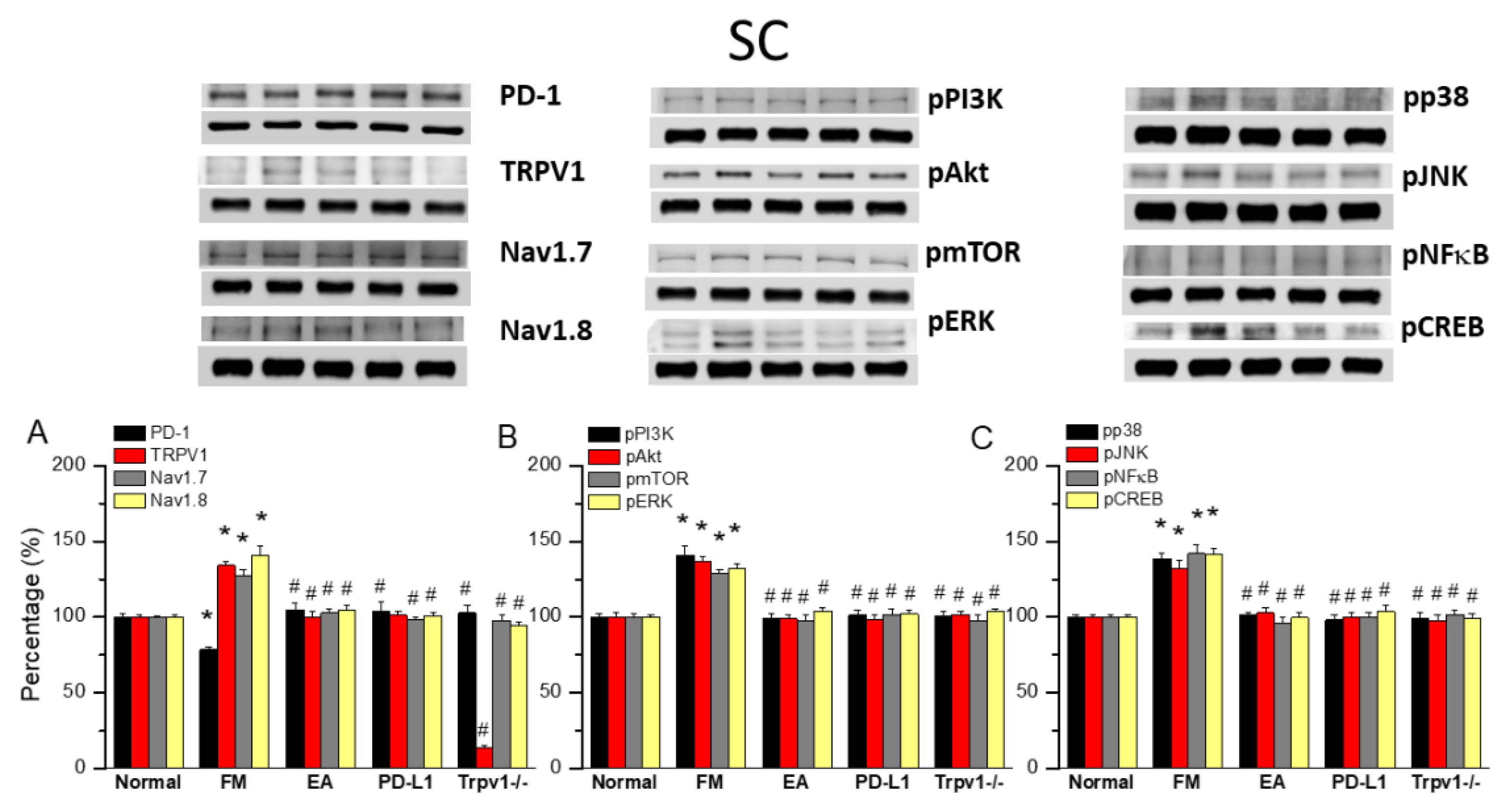

EA at ST36 Diminished Cold Stress-Induced FM Pain Through TRPV1-CB1 in the SCDH

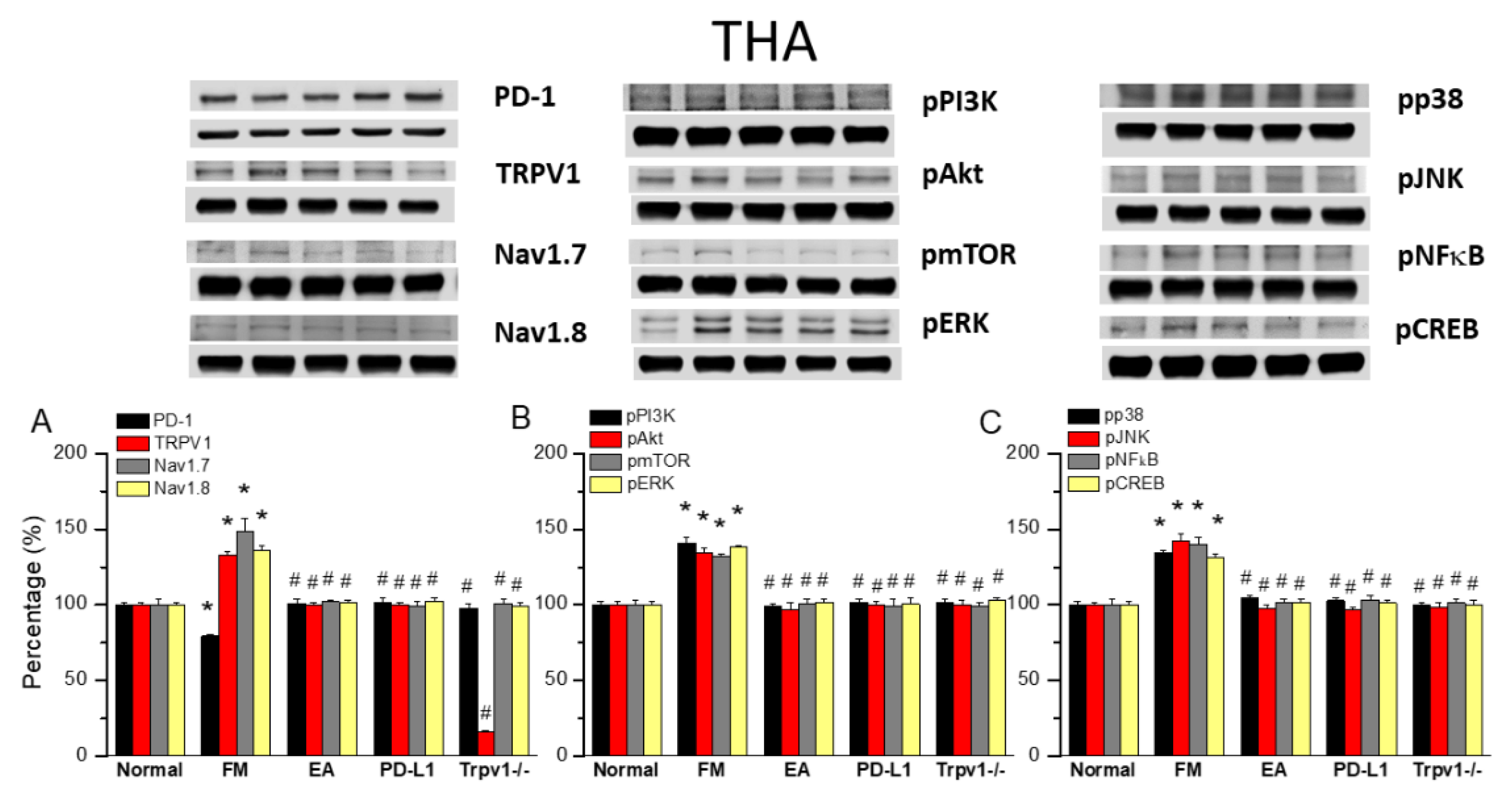

EA at ST36 Altered FM Pain and Regulated PD-1 Signaling Pathway in the Thalamus

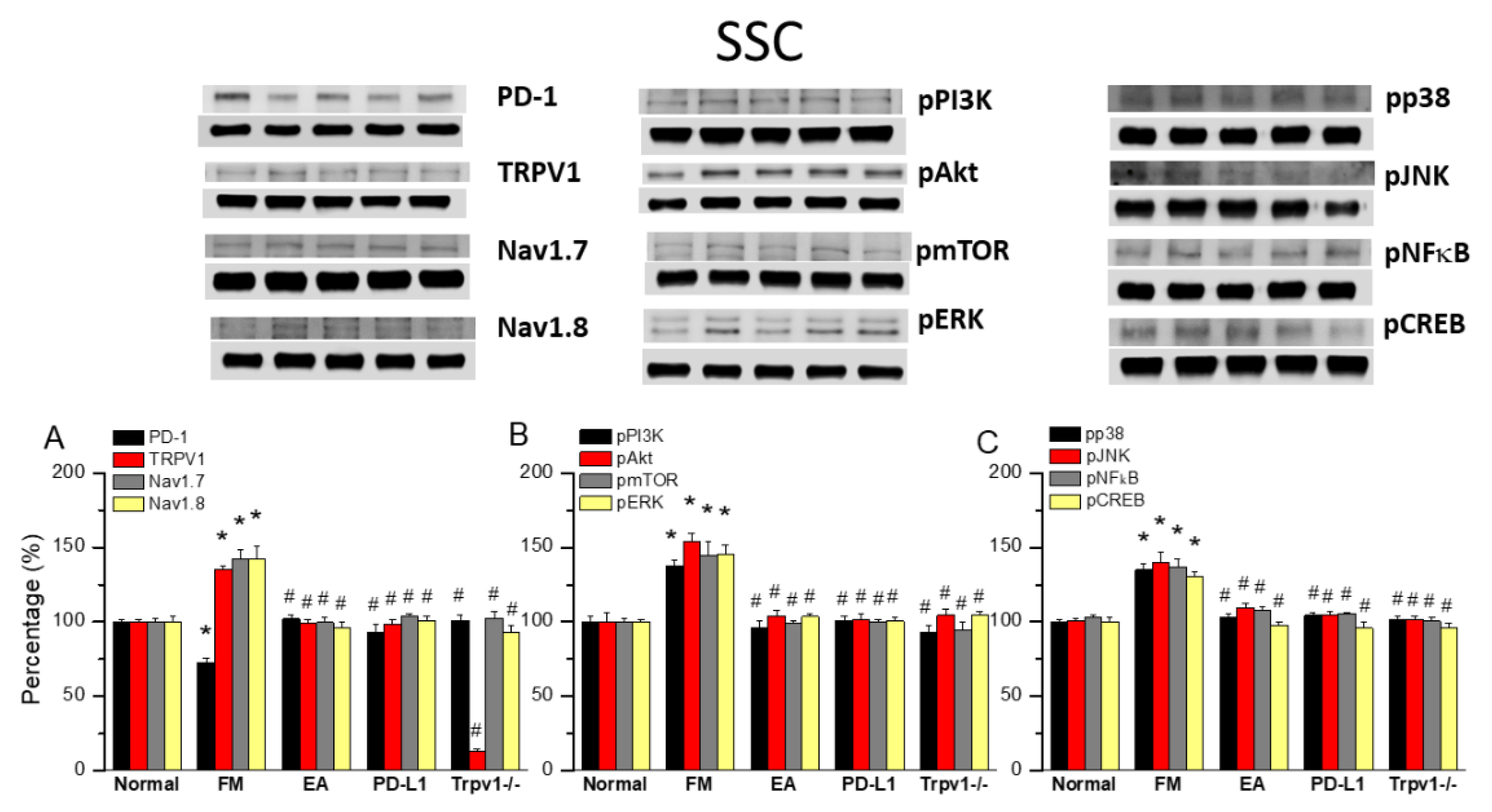

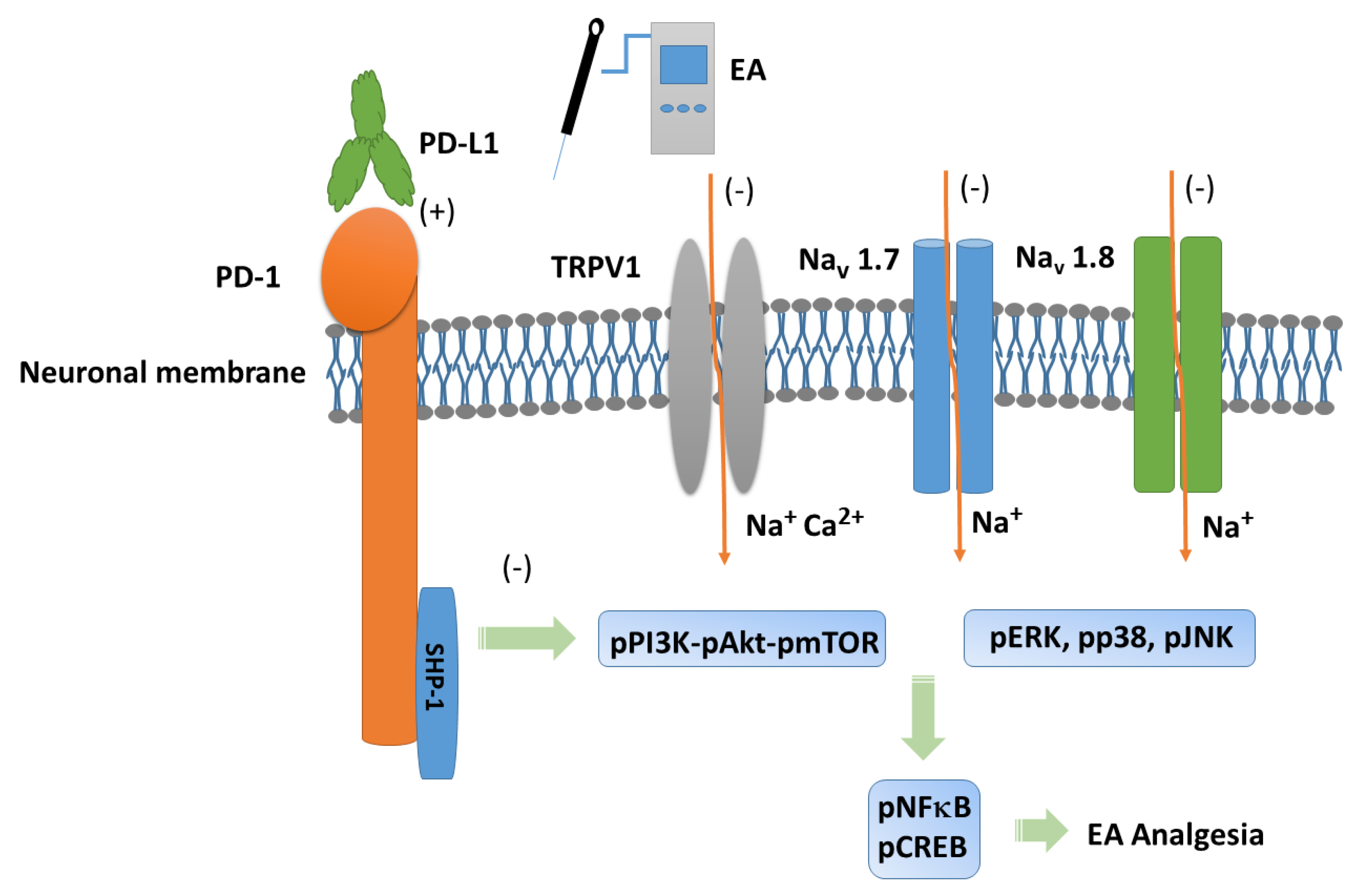

TRPV1 and Related Factors were Inhibited in the SSC after ICS and Recovered by 2 Hz EA and Trpv1 Deletion

EA, Intracerebral PD-L1 Injection or TRPV1 Loss Mitigated FM in the DRG or SSC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.; Kang, X.; Chen, K. S.; Jehng, T.; Jones, L.; Chen, J.; Huang, X. F.; Chen, S. Y., An engineered oncolytic virus expressing PD-L1 inhibitors activates tumor neoantigen-specific T cell responses. Nat Commun 2020, 11, (1), 1395. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kim, Y. H.; Li, H.; Luo, H.; Liu, D. L.; Zhang, Z. J.; Lay, M.; Chang, W.; Zhang, Y. Q.; Ji, R. R., PD-L1 inhibits acute and chronic pain by suppressing nociceptive neuron activity via PD-1. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, (7), 917-926. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. N.; Pavone, K. J.; Naranjo, M., Multimodal General Anesthesia: Theory and Practice. Anesth Analg 2018, 127, (5), 1246-1258. [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Angeles, M.; Morales-Lazaro, S. L.; Juarez-Gonzalez, E.; Rosenbaum, T., TRPV1: Structure, Endogenous Agonists, and Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (10). [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, A. P.; Voets, T.; Iadarola, M. J.; Szallasi, A., Targeting TRP channels for pain relief: A review of current evidence from bench to bedside. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2024, 75, 102447. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Carvajal, A.; Fernandez-Ballester, G.; Ferrer-Montiel, A., TRPV1 in chronic pruritus and pain: Soft modulation as a therapeutic strategy. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 930964. [CrossRef]

- Inprasit, C.; Lin, Y. W., TRPV1 Responses in the Cerebellum Lobules V, VIa and VII Using Electroacupuncture Treatment for Inflammatory Hyperalgesia in Murine Model. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (9). [CrossRef]

- Lottering, B.; Lin, Y. W., TRPV1 Responses in the Cerebellum Lobules VI, VII, VIII Using Electroacupuncture Treatment for Chronic Pain and Depression Comorbidity in a Murine Model. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (9). [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I. H.; Lin, Y. W., Electroacupuncture Reduces Fibromyalgia Pain by Attenuating the HMGB1, S100B, and TRPV1 Signalling Pathways in the Mouse Brain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 2022, 2242074. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H. Y.; Lin, Y. W., Electroacupuncture reduces cold stress-induced pain through microglial inactivation and transient receptor potential V1 in mice. Chin Med 2021, 16, (1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H. C.; Hsieh, C. L.; Wu, S. Y.; Lin, Y. W., Toll-like receptor 2 plays an essential role in electroacupuncture analgesia in a mouse model of inflammatory pain. Acupunct Med 2019, 37, (6), 356-364. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H. C.; Hsieh, C. L.; Lee, K. T.; Lin, Y. W., Electroacupuncture reduces fibromyalgia pain by downregulating the TRPV1-pERK signalling pathway in the mouse brain. Acupunct Med 2020, 38, (2), 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H. Y.; Lin, Y. W., Electroacupuncture Attenuates Chronic Inflammatory Pain and Depression Comorbidity through Transient Receptor Potential V1 in the Brain. Am J Chin Med 2021, 49, (6), 1417-1435. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Hsieh, C. L.; Lin, Y. W., Role of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 in Electroacupuncture Analgesia on Chronic Inflammatory Pain in Mice. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 5068347. [CrossRef]

- Lottering, B.; Lin, Y. W., Functional characterization of nociceptive mechanisms involved in fibromyalgia and electroacupuncture. Brain Res 2021, 1755, 147260. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. W.; Chou, A. I. W.; Su, H.; Su, K. P., Transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) modulates the therapeutic effects for comorbidity of pain and depression: The common molecular implication for electroacupuncture and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 89, 604-614. [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, R.; Paola, R. D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D., Fibromyalgia: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment Options Update. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (8). [CrossRef]

- Janssen, L. P.; Medeiros, L. F.; Souza, A.; Silva, J. D., Fibromyalgia: A Review of Related Polymorphisms and Clinical Relevance. An Acad Bras Cienc 2021, 93, (suppl 4), e20210618. [CrossRef]

- Assavarittirong, C.; Samborski, W.; Grygiel-Gorniak, B., Oxidative Stress in Fibromyalgia: From Pathology to Treatment. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 1582432. [CrossRef]

- Farag, H. M.; Yunusa, I.; Goswami, H.; Sultan, I.; Doucette, J. A.; Eguale, T., Comparison of Amitriptyline and US Food and Drug Administration-Approved Treatments for Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, (5), e2212939. [CrossRef]

- Peck, M. M.; Maram, R.; Mohamed, A.; Ochoa Crespo, D.; Kaur, G.; Ashraf, I.; Malik, B. H., The Influence of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines and Genetic Variants in the Development of Fibromyalgia: A Traditional Review. Cureus 2020, 12, (9), e10276. [CrossRef]

- Menzies, V.; Lyon, D. E., Integrated review of the association of cytokines with fibromyalgia and fibromyalgia core symptoms. Biol Res Nurs 2010, 11, (4), 387-94. [CrossRef]

- Ghowsi, M.; Qalekhani, F.; Farzaei, M.H.; Mahmudii, F.; Yousofvand, N.; Joshi, T. Inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and hypertension as mediators for adverse effects of obesity on the brain: A review. Biomedicine 2021, 11, 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Qi, L.; Yang, W.; Fu, M.; Jing, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Q., A neuroanatomical basis for electroacupuncture to drive the vagal-adrenal axis. Nature 2021, 598, (7882), 641-645. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rosas, R.; Yehia, G.; Pena, G.; Mishra, P.; del Rocio Thompson-Bonilla, M.; Moreno-Eutimio, M. A.; Arriaga-Pizano, L. A.; Isibasi, A.; Ulloa, L., Dopamine mediates vagal modulation of the immune system by electroacupuncture. Nat Med 2014, 20, (3), 291-5. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, I. H.; Liao, H. Y.; Cheng, C. M.; Yen, C. M.; Lin, Y. W., Paper-Based Detection Device for Microenvironment Examination: Measuring Neurotransmitters and Cytokines in the Mice Acupoint. Cells 2022, 11, (18). [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S. T.; Wei, T. H.; Yang, Y. W.; Lu, M. K.; San, S.; Tsai, C. H.; Lin, Y. W., Transient receptor potential V1 modulates neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease dementia: Molecular implications for electroacupuncture and rivastigmine. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2021, 24, (10), 1336-1345.

- Lu, K. W.; Yang, J.; Hsieh, C. L.; Hsu, Y. C.; Lin, Y. W., Electroacupuncture restores spatial learning and downregulates phosphorylated N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Acupunct Med 2017, 35, (2), 133-141. [CrossRef]

- Inprasit, C.; Huang, Y. C.; Lin, Y. W., Evidence for acupoint catgut embedding treatment and TRPV1 gene deletion increasing weight control in murine model. Int J Mol Med 2020, 45, (3), 779-792. [CrossRef]

- Choowanthanapakorn, M.; Lu, K. W.; Yang, J.; Hsieh, C. L.; Lin, Y. W., Targeting TRPV1 for Body Weight Control using TRPV1(-/-) Mice and Electroacupuncture. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17366. [CrossRef]

- Yen, L. T.; Hsieh, C. L.; Hsu, H. C.; Lin, Y. W., Targeting ASIC3 for Relieving Mice Fibromyalgia Pain: Roles of Electroacupuncture, Opioid, and Adenosine. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 46663. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H. Y.; Hsieh, C. L.; Huang, C. P.; Lin, Y. W., Electroacupuncture Attenuates Induction of Inflammatory Pain by Regulating Opioid and Adenosine Pathways in Mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, (1), 15679. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. L.; Cao, Q. L.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H. Z.; Zhang, Y. Q., Inhibition of TRPV1 by SHP-1 in nociceptive primary sensory neurons is critical in PD-L1 analgesia. JCI Insight 2020, 5, (20). [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Sun, K.; Zhu, J.; Li, F.; Lin, F.; Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Ren, C.; Lu, L.; Zhao, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J., PD-L1 Improves Motor Function and Alleviates Neuropathic Pain in Male Mice After Spinal Cord Injury by Inhibiting MAPK Pathway. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 670646. [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Han, Y.; Wang, D.; Guo, P.; Wang, J.; Ren, T.; Wang, W., PD-L1 and PD-1 expressed in trigeminal ganglia may inhibit pain in an acute migraine model. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, (3), 288-298. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yan, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, P., The Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1/Programmed Cell Death-1 Pathway Mediates Pregnancy-Induced Analgesia via Regulating Spinal Inflammatory Cytokines. Anesth Analg 2021, 133, (5), 1321-1330. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Lu, M.; Yao, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, G., An analgesic peptide H-20 attenuates chronic pain via the PD-1 pathway with few adverse effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, (31), e2204114119. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).