Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Strain, Cultivation and Maintenance Conditions

2.2. Effect of Nitrogen and Carbon Sources on γ-PGA Production in B.licheniformis DPC6338

2.3. Determination of Significant Medium Components Using Fractional Factorial Design

2.4. Optimisation of the Concentration of Medium Components for γ-PGA Production in B.licheniformis DPC6338 Using Central Composite Design (CCD)

2.5. Determination of Culture Conditions Using OFAT

2.6. Bioreactor Experiments

2.7. Analytical Methods

2.7.1. Purification of γ-PGA

2.7.2. Quantitative Determination and Characterisation of γ- PGA Produced by Bacillus licheniformis DPC 6338

2.7.3. Other Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

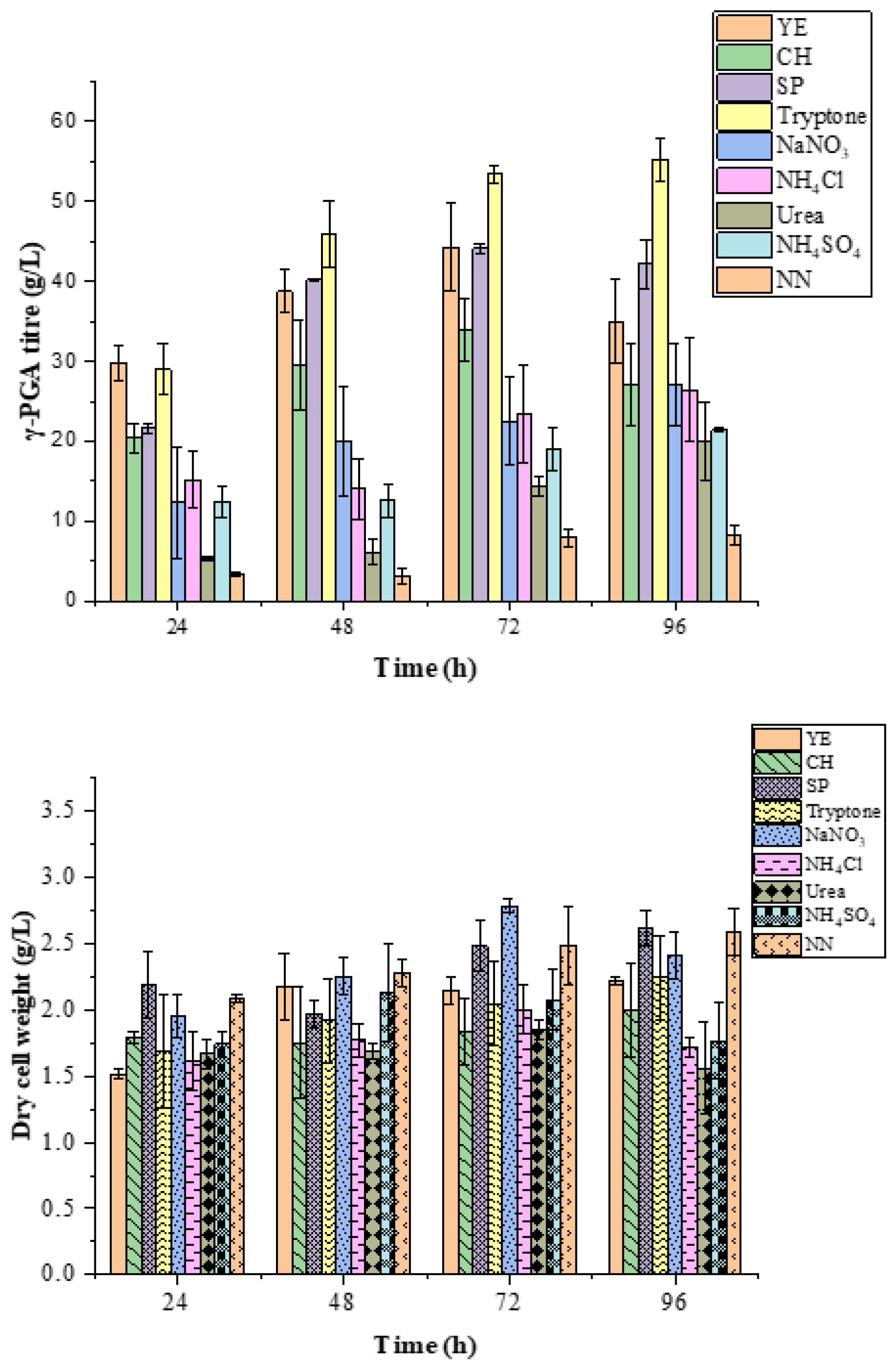

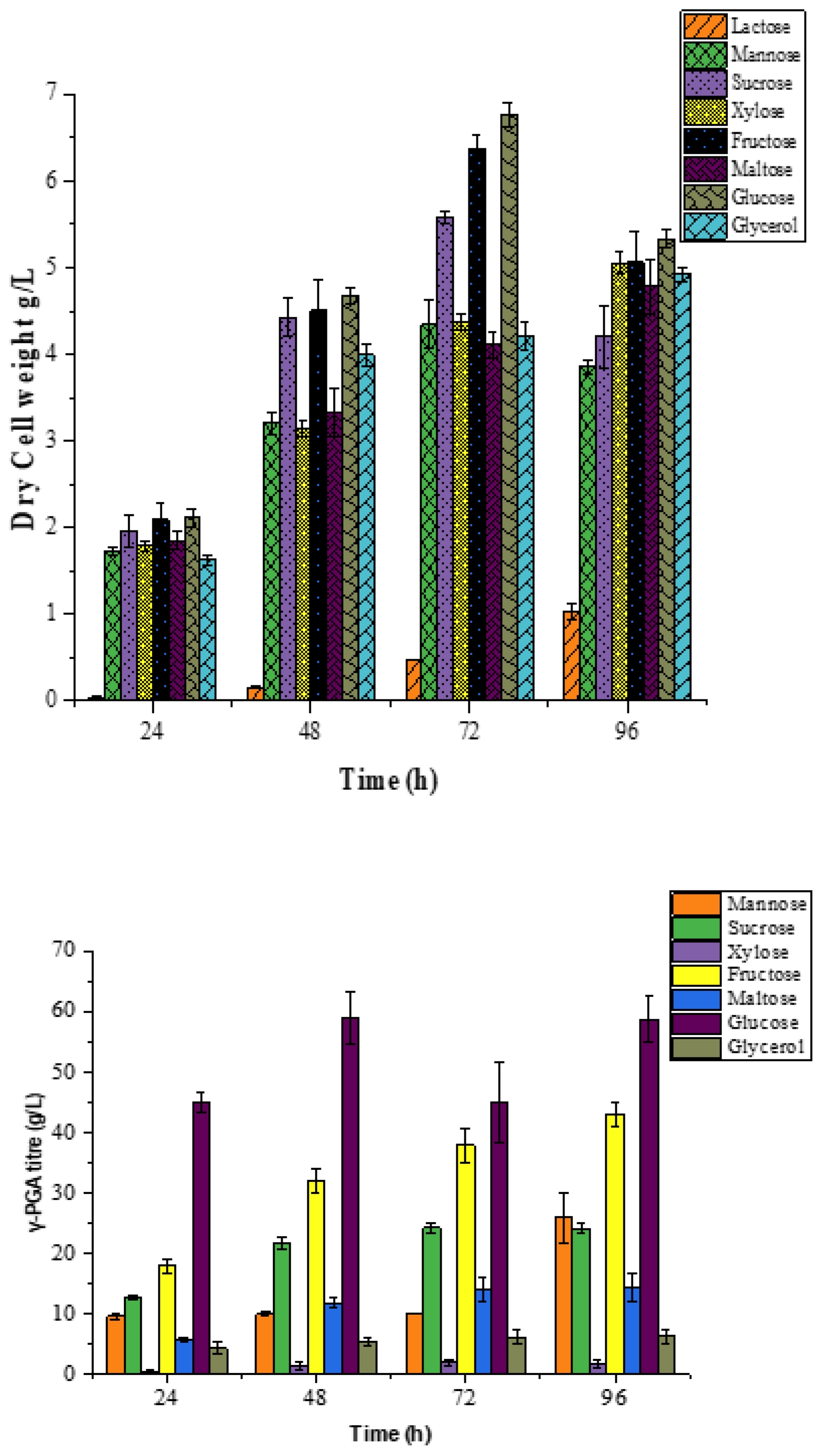

3.1. Effect of Nitrogen and Carbon Source on Biomass Growth and PGA Titre

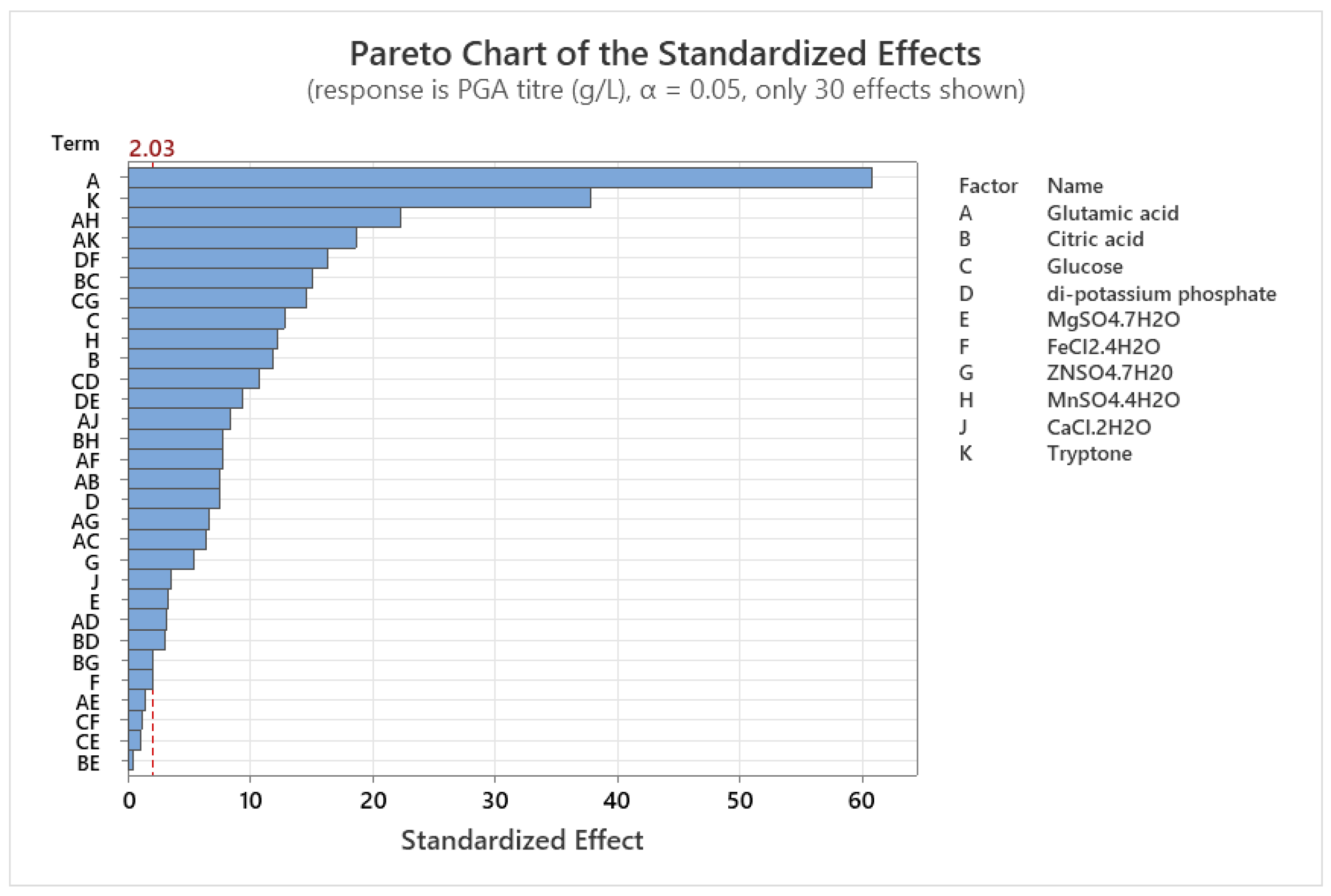

3.2. Screening of Significant Medium Components Using Fractional Factorial Design (FFD)

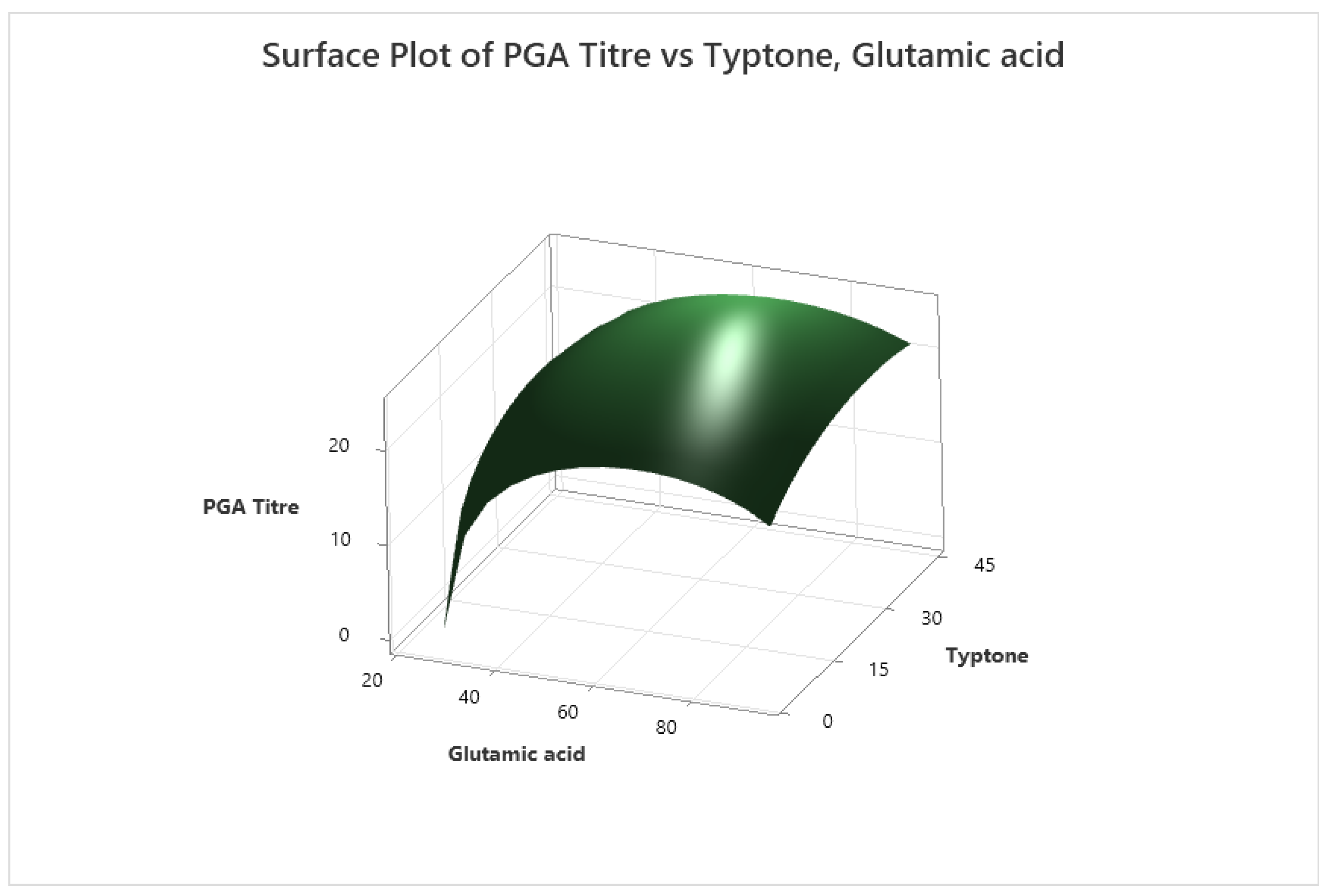

3.3. Optimisation of Medium Composition with Central Composite Design CCD

3.4. Numerical Optimization and Validation

3.5. Effect of Culture Conditions Using OFAT

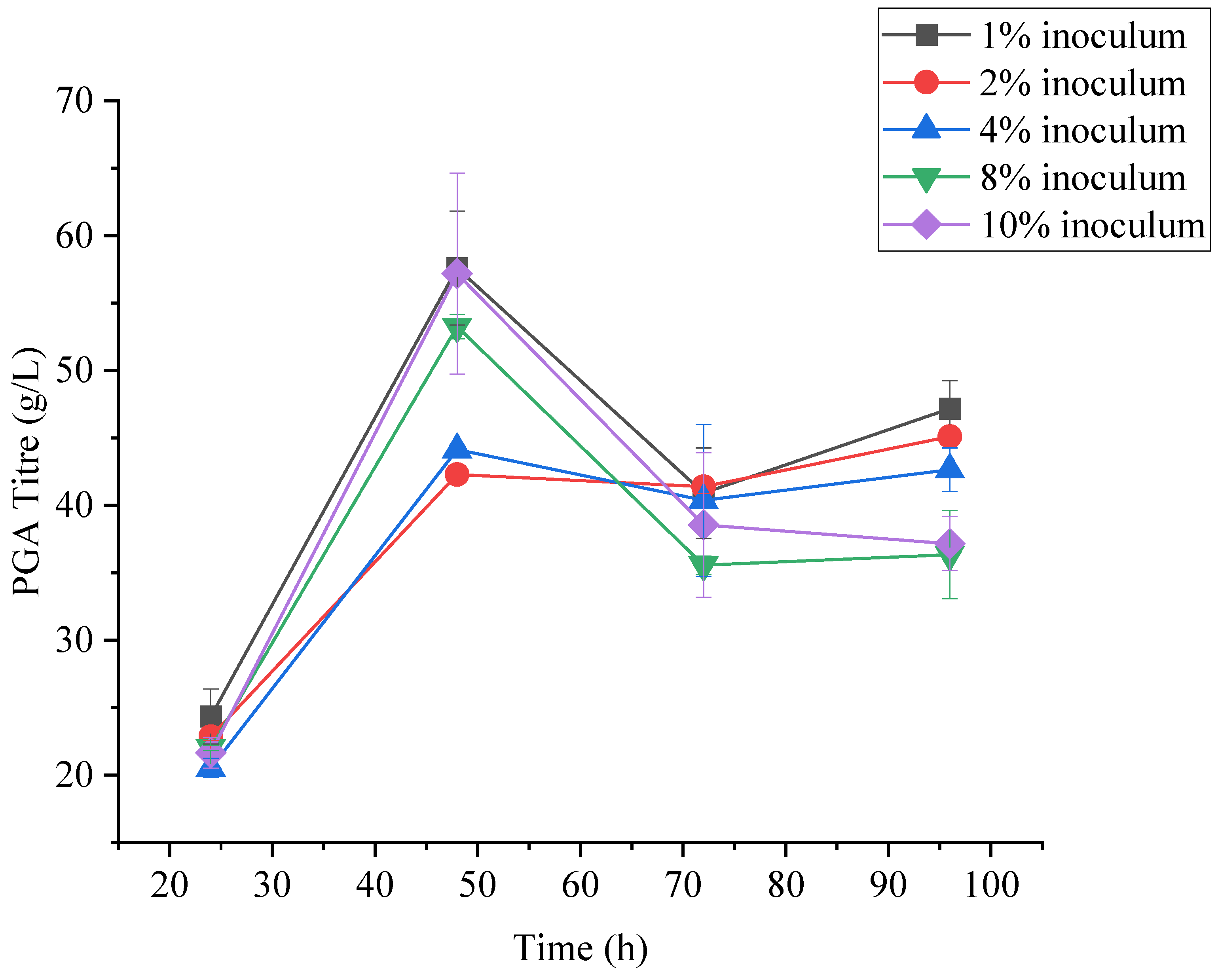

3.5.1. Effect of Inoculum Concentration

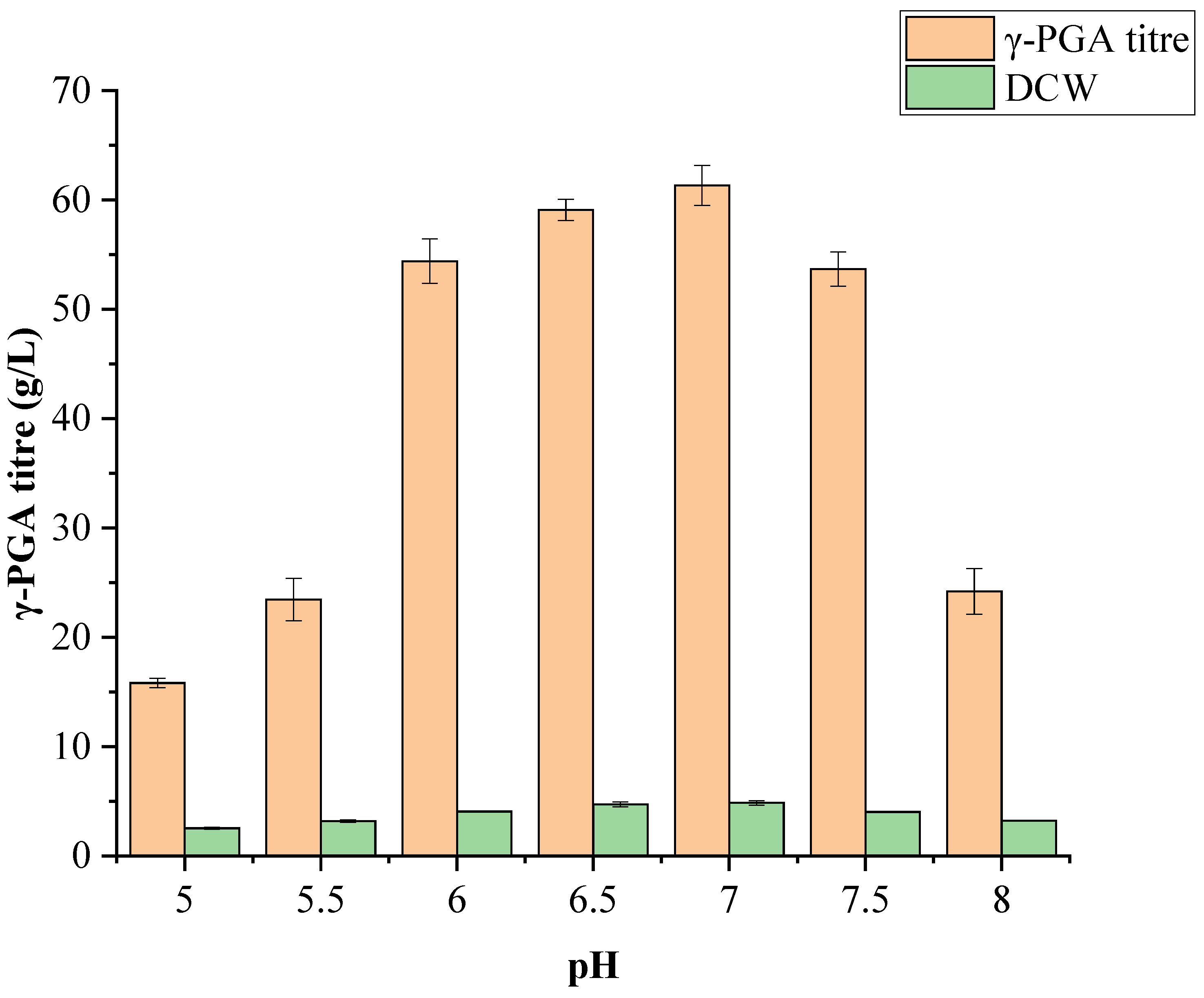

3.5.2. Effect of pH

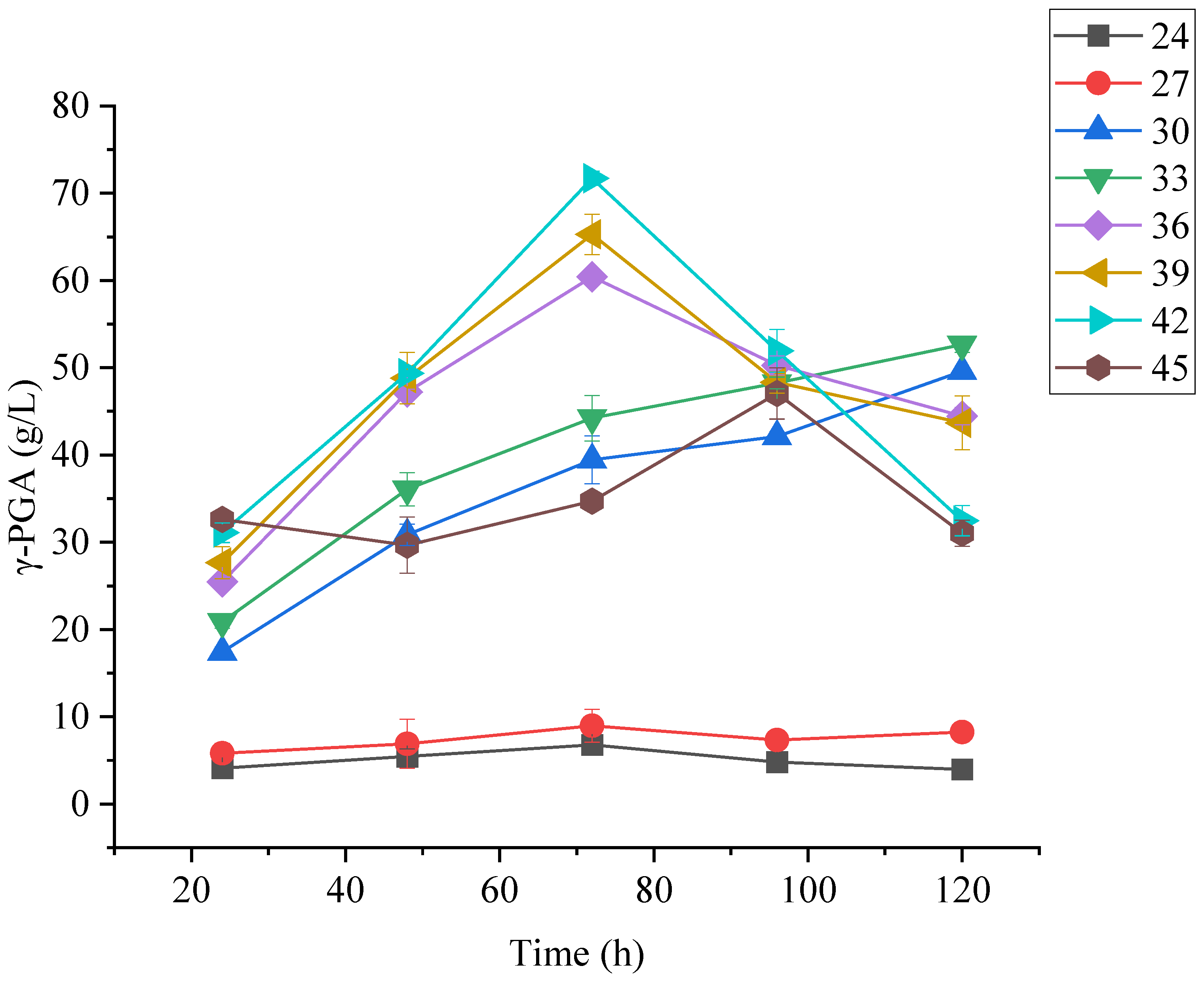

3.5.3. Effect of Temperature

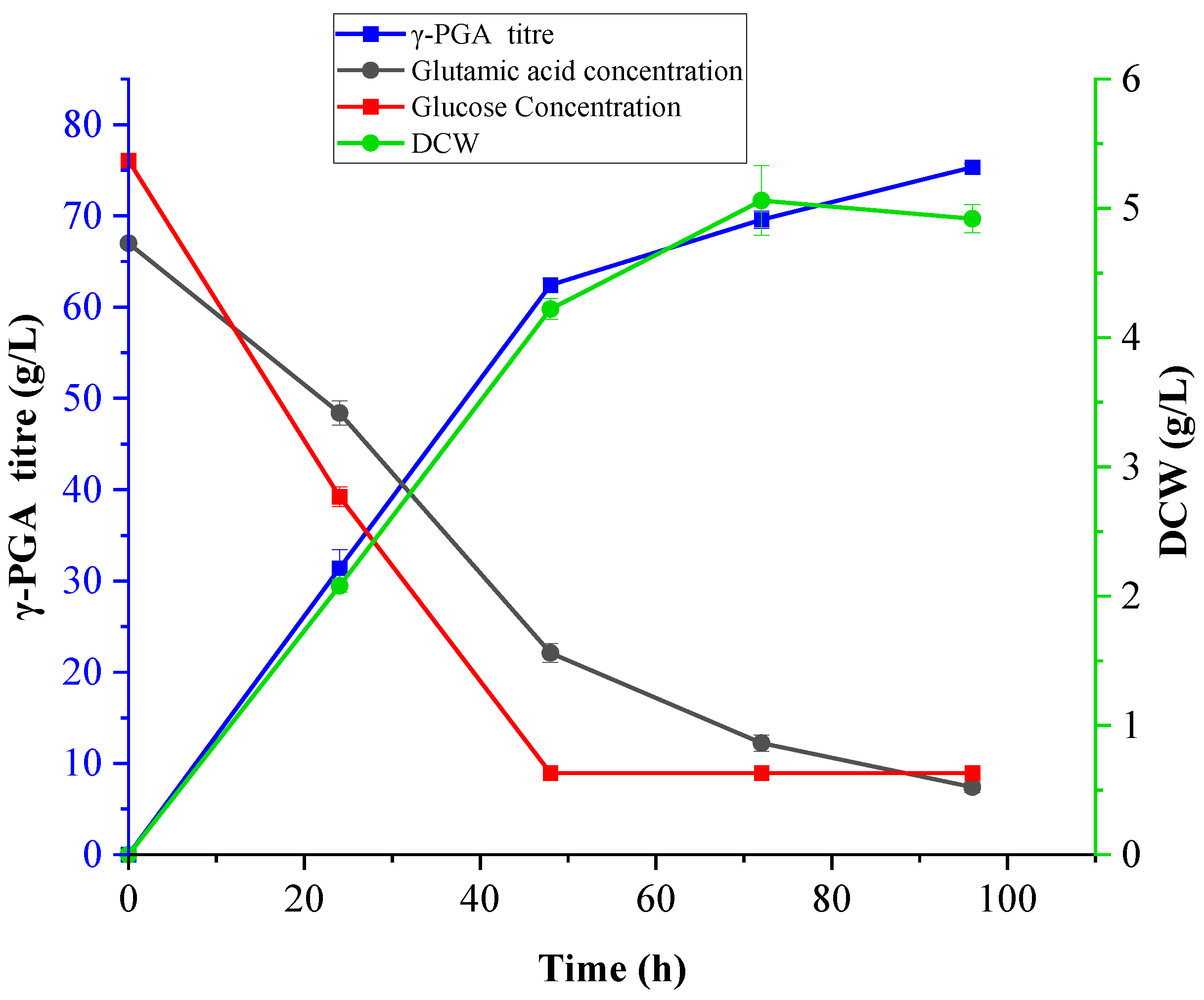

3.6. Production of γ-PGA Under Optimised Conditions at Shake Flask and Bioreactor Scale

| Screening medium | Optimised medium | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | γ-PGA titre g/L |

γ-PGA productivity g/L/h | γ-PGA titre g/L | γ-PGA productivity g/L/h |

| 24 | 54.91 ± 4.11 | 2.29 | 56.25 ±4.17 | 2.34 |

| 48 | 84.08 ± 5.19 | 1.75 | 81.36 ± 3.92 | 1.70 |

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murakami, S.; Aoki, N.; Matsumura, S. Bio-based biodegradable hydrogels prepared by crosslinking of microbial poly (γ-glutamic acid) with L-lysine in aqueous solution. Polymer journal 2011, 43, 414-420. [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Rehm, B.H. Bacterial biopolymers: from pathogenesis to advanced materials. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020, 18, 195-210. [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, A.; Bhat, A.; Irorere, V.U.; Hill, D.; Williams, C.; Radecka, I. Poly-γ-glutamic acid: production, properties and applications. Microbiology 2015, 161, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.; Navale, G.R.; Dharne, M.S. Poly-gamma-glutamic acid biopolymer: A sleeping giant with diverse applications and unique opportunities for commercialization. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13, 4555-4573. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Qiu, H.; Zhao, M.; Zou, W.; Li, S. Microbial synthesis of poly-γ-glutamic acid: current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2016, 9, 134. [CrossRef]

- Okuofu, S.I.; O’Flaherty, V.; McAuliffe, O. Production of Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Exploring the State of the Art. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2024, 109250. [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, K.; Alsulami, F.S.; Neyaz, L.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Poly (γ) glutamic acid: A unique microbial biopolymer with diverse commercial applicability. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1348411. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, F.; Chen, Y.; Jin, C.; Guo, J.-H.; Chai, Y. Poly-γ-Glutamic Acids Contribute to Biofilm Formation and Plant Root Colonization in Selected Environmental Isolates of Bacillus subtilis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, Volume 7 - 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Pan, Z.; Chen, Z.; He, N. Stress response regulation to extracellular polymeric substances biosynthesis in Bacillus licheniformis. Microbial Cell Factories 2025, 24, 222. [CrossRef]

- Deol, R.; Louis, A.; Glazer, H.L.; Hosseinion, W.; Bagley, A.; Chandrangsu, P. Poly-gamma-glutamic acid secretion protects Bacillus subtilis from zinc and copper intoxication. Microbiology spectrum 2022, 10, e01329-01321. [CrossRef]

- Mark, S.S.; Crusberg, T.C.; Dacunha, C.M.; Di Iorio, A.A. A heavy metal biotrap for wastewater remediation using poly-gamma-glutamic acid. Biotechnol Prog 2006, 22, 523-531. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Tong, T.; Wang, R.; Qiu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Sun, L.; Xu, H.; Lei, P. Secretion of poly-γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus atrophaeus NX-12 enhanced its root colonization and biocontrol activity. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, Volume 13 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Hagihara, H.; Takimura, Y.; Kataoka, M. Production and molecular weight variation of poly-γ-glutamic acid using a recombinant Bacillus subtilis with various Pgs-component ratios. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2024, 88, 1217-1224. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.H.; Huang, K.Y.; Kunene, S.C.; Lee, T.Y. Poly-γ-glutamic Acid Synthesis, Gene Regulation, Phylogenetic Relationships, and Role in Fermentation. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yang, L.; Chen, Z.; Xia, W.; Chen, Y.; Cao, M.; He, N. Molecular weight control of poly-γ-glutamic acid reveals novel insights into extracellular polymeric substance synthesis in Bacillus licheniformis. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 2024, 17, 60. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Zhao, T.; Zheng, G.; Qiao, C. Effects of Fe2+ addition to sugarcane molasses on poly-γ-glutamic acid production in Bacillus licheniformis CGMCC NO. 23967. Microbial Cell Factories 2023, 22, 37, . [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, D.; Yoshioka, M.; Ashiuchi, M. Bacillus subtilis pgsE (Formerly ywtC) stimulates poly-γ-glutamate production in the presence of zinc. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2011, 108, 226-230. [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.-Y.; Jung, S.; Yun, J.-S.; Kim, J.-N.; Wee, Y.-J.; Jang, H.-G.; Ryu, H.-W. Influences of cultural medium component on the production of poly(γ-glutamic acid) byBacillus sp. RKY3. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2005, 10, 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Völker, F.; Hoffmann, K.; Halmschlag, B.; Maaß, S.; Büchs, J.; Blank, L.M. Citrate Supplementation Modulates Medium Viscosity and Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid Synthesis by Engineered B. subtilis 168. Engineering in Life Sciences 2025, 25, e70009. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.70009.

- Feng, J.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, G.; Wang, L.; Chen, A.; Xie, X.; Huang, X.; Hu, W. Improved production of poly-γ-glutamic acid with low molecular weight under high ferric ion concentration stress in Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945a. Process Biochemistry 2017, 56, 30-36. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Wang, H.; Jia, H.; Ni, H.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tu, Q. Production and Characterization of Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid by Bacillus velezensis SDU. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 917. [CrossRef]

- Tork, S.E.; Aly, M.M.; Alakilli, S.Y.; Al-Seeni, M.N. Purification and characterization of gamma poly glutamic acid from newly Bacillus licheniformis NRC20. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2015, 74, 382-391. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Liu, Y.; Shu, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, Z. Production of ultra-high-molecular-weight poly-γ-glutamic acid by a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis strain and genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Biotechnology Journal 2024, 19, 2300614. [CrossRef]

- Okuofu, S.I.; Nayak, J.K.; Khan, A.A.; O’Flaherty, V.; McAuliffe, O. NADES pretreatment of ryegrass pressed cake for biosugar and γ–PGA production. Industrial Crops and Products 2025, 237, 122307, . [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh Kouchesfahani, M.; Bahrami, A.; Babaeipour, V. Poly-γ-glutamic acid overproduction of Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945a by developing a novel optimum culture medium and glutamate pulse feeding using different experimental design approaches. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry 2024, 71, 565-583. [CrossRef]

- Mahaboob Ali, A.A.; Momin, B.; Ghogare, P. Isolation of a novel poly-γ-glutamic acid-producing Bacillus licheniformis A14 strain and optimization of fermentation conditions for high-level production. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology 2020, 50, 445-452. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, I.B.; Lele, S.S.; Singhal, R.S. Enhanced production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) from Bacillus licheniformis NCIM 2324 in solid state fermentation. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2008, 35, 1581-1581. [CrossRef]

- Manocha, B.; Margaritis, A. A novel Method for the selective recovery and purification of γ-polyglutamic acid from Bacillus licheniformis fermentation broth. Biotechnology progress 2010, 26, 734-742. [CrossRef]

- Halmschlag, B.; Völker, F.; Hanke, R.; Putri, S.P.; Fukusaki, E.; Büchs, J.; Blank, L.M. Metabolic engineering of B. subtilis 168 for increased precursor supply and poly-γ-glutamic acid production. Frontiers in Food Science and Technology 2023, 3, 1111571, . [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Asada, Y.; Aida, T. Production of γ-Polyglutamic Acid by Bacillus licheniformis A35 under Denitrifying Conditions. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry 1989, 53, 2369-2375. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.H.; Reddy, L.V.; Dimitris, C.; Kim, Y.M.; Wee, Y.J. Optimized Production of Poly(γ-Glutamic acid) By Bacillus sp. FBL-2 through Response Surface Methodology Using Central Composite Design. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 29, 1061-1070. [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Shouwen, C.; Ziniu, Y. Optimization of process parameters for poly γ-glutamate production under solid state fermentation from Bacillus subtilis CCTCC202048. Process Biochemistry 2005, 40, 3075-3081. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Fu, X.; Zhou, D.; Gao, J.; Bai, W. Engineering of a newly isolated Bacillus tequilensis BL01 for poly-γ-glutamic acid production from citric acid. Microbial Cell Factories 2022, 21, 276. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cai, Y.; Wang, D. Enhanced Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid Production by a Newly Isolated Bacillus halotolerans F29. J Microbiol 2024, 62, 695-707. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hwang, J.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.-H.; Joe, M.-H. A newly isolated Bacillus siamensis SB1001 for mass production of poly-γ-glutamic acid. Process Biochemistry 2020, 92, 164-173. [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Xu, Z.; Cen, P. Optimization of γ-polyglutamic acid production by Bacillus subtilis ZJU-7 using a surface-response methodology. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2006, 11, 251-257. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Liang, Z.; Li, Z.; Bian, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z.; Chen, G. Regulation of poly-γ-glutamic acid production in Bacillus subtilis GXA-28 by potassium. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2016, 61, 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, J.; Qu, Y.B.; Lun, S.Y. [Effects of metal ions on gamma-poly (glutamic acid) synthesis by Bacillus licheniformis]. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2001, 17, 706-709.

- Ju, W.-T.; Song, Y.-S.; Jung, W.-J.; Park, R.-D. Enhanced production of poly-γ-glutamic acid by a newly-isolated Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnology Letters 2014, 36, 2319-2324. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Gu, L.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, H.; Zha, J.; Yin, D.; Qian, J.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. Coculture Corynebacterium glutamicum and Bacillus licheniformis for producing poly-γ-glutamic acid from glucose. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2025, 109, 259. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, R.M.; Samir, R.; Gomaa, O.M.; ElHifnawi, H.N.; Ramadan, M.A. Production and optimization of polyglutamic acid from Bacillus licheniformis: effect of low levels of gamma radiation. AMB Express 2025, 15, 93. [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.G.; Joseph, E.; Yadav, R.; Rajput, V.; Nisal, A.; Dharne, M.S. Production of poly-gamma-glutamic acid (γ-PGA) from sucrose by an osmotolerant Bacillus paralicheniformis NCIM 5769 and genome-based predictive biosynthetic pathway. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Shu, L.; Chen, H.; Duan, X.; Zeng, W. Poly-γ-glutamic acid production from untreated sugarcane molasses by non-sterilized repeated-batch fermentation with Bacillus subtilis GLS-8. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2025, 24, 100900. [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Reddy, L.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Wee, Y. Poly-(Υ-glutamic acid) production and optimization from agro-industrial bioresources as renewable substrates by Bacillus sp. FBL-2 through response surface methodology. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.B.; Cantarelli, V.V.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Production and optimization of poly-γ-glutamic acid by Bacillus subtilis BL53 isolated from the Amazonian environment. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 2014, 37, 469-479. [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Hu, Q. Optimization of Fermentation Conditions for γ-PGA Production by Bacillus subtilis QM3. Open Access Library Journal 2024, 11, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Chen, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, B.; Dong, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Che, Z.; Liang, Z. Production of poly-γ-glutamic acid by a thermotolerant glutamate-independent strain and comparative analysis of the glutamate dependent difference. AMB Express 2017, 7, 213. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Feng, X.; Li, S.; Chen, F.; Xu, H. Effects of oxygen vectors on the synthesis and molecular weight of poly(γ-glutamic acid) and the metabolic characterization of Bacillus subtilis NX-2. Process Biochemistry 2012, 47, 2103-2109. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, F.; Xu, L.; Luo, M.; Liu, H. Production of ultra-high molecular weight poly-γ-glutamic acid with Bacillus licheniformis P-104 and characterization of its flocculation properties. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2013, 170, 562-572. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T.; Mu, W.; Miao, M.; Hua, Y. High-level production of poly(γ-glutamic acid) by a newly isolated glutamate-independent strain, Bacillus methylotrophicus. Process Biochemistry 2015, 50, 329-335. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh Kouchesfahani, M.; Bahrami, A.; Babaeipour, V. Poly-γ-glutamic acid overproduction of Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945(a) by developing a novel optimum culture medium and glutamate pulse feeding using different experimental design approaches. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2024, 71, 565-583. [CrossRef]

| Factors | Low, −1; | High, +1 | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 20 | 60 | g/L |

| Glutamic acid | 10 | 50 | g/L |

| Citric acid | 5 | 15 | g/L |

| Tryptone | 5 | 20 | g/L |

| K2HPO4 | 0.5 | 2 | g/L |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.5 | 2 | g/L |

| FeCl3·6H2O | 0.02 | 0.1 | g/L |

| CaCl2·2H2O | 0.1 | 0.5 | g/L |

| MnSO4·H2O | 0.1 | 0.5 | g/L |

| ZnSO4·7H2O | 0.5 | 2 | g/L |

| Run Order | Glutamic acid | Citric acid | Glucose | K2HPO4 | MgSO4 .7H2O |

FeCl2. 4H2O |

ZnSO4. 7H20 |

MnSO4. 4H2O |

CaCl. 2H2O |

Tryptone | PGA titre (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 6.85 |

| 2 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 3.64 |

| 3 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 8.77 |

| 4 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 6.22 |

| 5 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.1 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 2.14 |

| 6 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 2.61 |

| 7 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 6.96 |

| 8 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 12.40 |

| 9 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.74 |

| 10 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 4.49 |

| 11 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 4.52 |

| 12 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 0.06 |

| 13 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 2.62 |

| 14 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 5.46 |

| 15 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 2.08 |

| 16 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 19.51 |

| 17 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.58 |

| 18 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 5.10 |

| 19 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 0.22 |

| 20 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 6.86 |

| 21 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 20.65 |

| 22 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 8.07 |

| 23 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 20.84 |

| 24 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 6.28 |

| 25 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 3.54 |

| 26 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 2.30 |

| 27 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 2.03 |

| 28 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 16.87 |

| 29 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 2.31 |

| 30 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.74 |

| 31 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 7.90 |

| 32 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 1.32 |

| 33 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 7.80 |

| 34 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.70 |

| 35 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 15.93 |

| 36 | 30.00 | 10.00 | 40.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.06 | 1.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 12.50 | 9.48 |

| 37 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 19.33 |

| 38 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 4.64 |

| 39 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 20.89 |

| 40 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 0.16 |

| 41 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 0.83 |

| 42 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.67 |

| 43 | 30.00 | 10.00 | 40.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.06 | 1.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 12.50 | 7.95 |

| 44 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 7.00 |

| 45 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 0.50 |

| 46 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 20.71 |

| 47 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 15.94 |

| 48 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 14.74 |

| 49 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 0.66 |

| 50 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.500 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 8.92 |

| 51 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 2.36 |

| 52 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.71 |

| 53 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 0.46 |

| 54 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 3.16 |

| 55 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 6.47 |

| 56 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 7.06 |

| 57 | 30.00 | 10.00 | 40.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.06 | 1.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 12.50 | 9.20 |

| 58 | 30.00 | 10.00 | 40.00 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.06 | 1.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 12.50 | 8.15 |

| 59 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 19.97 |

| 60 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 7.45 |

| 61 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 12.14 |

| 62 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 16.38 |

| 63 | 50.00 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 7.87 |

| 64 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 20.00 | 1.86 |

| 65 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.83 |

| 66 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 0.27 |

| 67 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 60.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.00 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 5.00 | 0.44 |

| 68 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5.00 | 0.35 |

| Model Summary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | R-sq | R-sq(adj) | R-sq(pred) | ||

| 0.587236 | 99.56% | 99.15% | 98.37% | ||

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 32 | 2714.85 | 84.84 | 246.02 | 0.000 |

| Linear | 10 | 1967.56 | 196.76 | 570.56 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid | 1 | 1276.67 | 1276.67 | 3702.14 | 0.000 |

| Citric acid | 1 | 48.28 | 48.28 | 140.02 | 0.000 |

| Glucose | 1 | 56.52 | 56.52 | 163.91 | 0.000 |

| K2HPO4 | 1 | 19.42 | 19.42 | 56.33 | 0.000 |

| MgSO4.7H2O | 1 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 11.10 | 0.002 |

| FeCl2.4H2O | 1 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 4.01 | 0.053 |

| ZnSO4.7H2O | 1 | 10.21 | 10.21 | 29.60 | 0.000 |

| MnSO4.4H2O | 1 | 52.06 | 52.06 | 150.98 | 0.000 |

| CaCl.2H2O | 1 | 4.38 | 4.38 | 12.71 | 0.001 |

| Tryptone | 1 | 494.79 | 494.79 | 1434.81 | 0.000 |

| 2-Way Interactions | 21 | 730.63 | 34.79 | 100.89 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid*Citric acid | 1 | 19.45 | 19.45 | 56.40 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid*Glucose | 1 | 14.09 | 14.09 | 40.85 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid* K2HPO4 | 1 | 3.49 | 3.49 | 10.13 | 0.003 |

| Glutamic acid* MgSO4.7H2O | 1 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 2.04 | 0.163 |

| Glutamic acid* FeCl2.4H2O | 1 | 20.55 | 20.55 | 59.58 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid* ZnSO4.7H2O | 1 | 15.50 | 15.50 | 44.95 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid* MnSO4.4H2O | 1 | 171.53 | 171.53 | 497.40 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid* CaCl.2H2O | 1 | 24.38 | 24.38 | 70.70 | 0.000 |

| Glutamic acid*Tryptone | 1 | 119.90 | 119.90 | 347.68 | 0.000 |

| Citric acid*Glucose | 1 | 78.88 | 78.88 | 228.73 | 0.000 |

| Citric acid* K2HPO4 | 1 | 3.27 | 3.27 | 9.49 | 0.004 |

| Citric acid* MgSO4.7H2O | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.649 |

| Citric acid* FeCl2.4H2O | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.755 |

| Citric acid* ZnSO4.7H2O | 1 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 4.37 | 0.044 |

| Citric acid* MnSO4.4H2O | 1 | 21.12 | 21.12 | 61.24 | 0.000 |

| Glucose* K2HPO4 | 1 | 39.55 | 39.55 | 114.69 | 0.000 |

| Glucose* MgSO4.7H2O | 1 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 1.04 | 0.314 |

| Glucose* FeCl2.4H2O | 1 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 1.27 | 0.268 |

| Glucose* ZnSO4.7H2O | 1 | 73.63 | 73.63 | 213.51 | 0.000 |

| K2HPO4* MgSO4.7H2O | 1 | 30.37 | 30.37 | 88.08 | 0.000 |

| K2HPO4* FeCl2.4H2O | 1 | 91.82 | 91.82 | 266.28 | 0.000 |

| Curvature | 1 | 16.66 | 16.66 | 48.32 | 0.000 |

| Error | 35 | 12.07 | 0.34 | ||

| Total | 67 | 2726.92 |

| Coded term | Uncoded term | Effect | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | P-Value | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 6.5916 | 0.0734 | 89.80 | 0.000 | |||

| A | Glutamic acid | 8.9326 | 4.4663 | 0.0734 | 60.85 | 0.000 | Significant |

| B | Citric acid | -1.7372 | -0.8686 | 0.0734 | -11.83 | 0.000 | Significant |

| C | Glucose | 1.8795 | 0.9398 | 0.0734 | 12.80 | 0.000 | Significant |

| D | K2HPO4 | 1.1018 | 0.5509 | 0.0734 | 7.51 | 0.000 | Significant |

| E | MgSO4.7H2O | -0.4891 | -0.2446 | 0.0734 | -3.33 | 0.002 | Significant |

| F | FeCl2.4H2O | -0.2941 | -0.1470 | 0.0734 | -2.00 | 0.053 | Not Significant |

| G | ZnSO4.7H2O | 0.7988 | 0.3994 | 0.0734 | 5.44 | 0.000 | Significant |

| H | MnSO4.4H2O | 1.8039 | 0.9019 | 0.0734 | 12.29 | 0.000 | Significant |

| J | CaCl.2H2O | -0.5234 | -0.2617 | 0.0734 | -3.56 | 0.001 | Significant |

| K | Tryptone | 5.5610 | 2.7805 | 0.0734 | 37.88 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AB | Glutamic acid*Citric acid | -1.1025 | -0.5513 | 0.0734 | -7.51 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AC | Glutamic acid*Glucose | 0.9383 | 0.4692 | 0.0734 | 6.39 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AD | Glutamic acid* K2HPO4 | 0.4672 | 0.2336 | 0.0734 | 3.18 | 0.003 | Significant |

| AE | Glutamic acid* MgSO4.7H2O | -0.2094 | -0.1047 | 0.0734 | -1.43 | 0.163 | Not Significant |

| AF | Glutamic acid* FeCl2.4H2O | -1.1332 | -0.5666 | 0.0734 | -7.72 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AG | Glutamic acid* ZnSO4.7H2O | 0.9843 | 0.4921 | 0.0734 | 6.70 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AH | Glutamic acid* MnSO4.4H2O | 3.2742 | 1.6371 | 0.0734 | 22.30 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AJ | Glutamic acid* CaCl.2H2O | -1.2344 | -0.6172 | 0.0734 | -8.41 | 0.000 | Significant |

| AK | Glutamic acid*Tryptone | 2.7374 | 1.3687 | 0.0734 | 18.65 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BC | Citric acid*Glucose | 2.2203 | 1.1101 | 0.0734 | 15.12 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BD | Citric acid* K2HPO4 | 0.4523 | 0.2262 | 0.0734 | 3.08 | 0.004 | Significant |

| BE | Citric acid* MgSO4.7H2O | 0.0675 | 0.0337 | 0.0734 | 0.46 | 0.649 | Not Significant |

| BF | Citric acid* FeCl2.4H2O | -0.0461 | -0.0230 | 0.0734 | -0.31 | 0.755 | Not Significant |

| BG | Citric acid* ZnSO4.7H2O | -0.3068 | -0.1534 | 0.0734 | -2.09 | 0.044 | Significant |

| BH | Citric acid* MnSO4.4H2O | 1.1489 | 0.5744 | 0.0734 | 7.83 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CD | Glucose* K2HPO4 | 1.5722 | 0.7861 | 0.0734 | 10.71 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CE | Glucose* MgSO4.7H2O | -0.1500 | -0.0750 | 0.0734 | -1.02 | 0.314 | Not Significant |

| CF | Glucose* FeCl2.4H2O | -0.1654 | -0.0827 | 0.0734 | -1.13 | 0.268 | Not Significant |

| CG | Glucose* ZnSO4.7H2O | -2.1452 | -1.0726 | 0.0734 | -14.61 | 0.000 | Significant |

| DE | K2HPO4* MgSO4.7H2O | 1.3778 | 0.6889 | 0.0734 | 9.38 | 0.000 | Significant |

| DF | K2HPO4* FeCl2.4H2O | 2.3956 | 1.1978 | 0.0734 | 16.32 | 0.000 | Significant |

| Ct Pt | 2.104 | 0.303 | 6.95 | 0.000 | Significant |

| Run Order | Glutamic acid | Tryptone | Glucose | γ-PGA Titre |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40.00 | 12.00 | 100.00 | 20.74 ± 0.60 |

| 2 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 22.89 ± 2.06 |

| 3 | 40.00 | 36.00 | 100.00 | 21.08 ± 1.21 |

| 4 | 40.00 | 12.00 | 50.00 | 19.56 ± 2.13 |

| 5 | 60.00 | 3.82 | 75.00 | 18.12 ± 0.55 |

| 6 | 40.00 | 36.00 | 50.00 | 20.70 ± 0.20 |

| 7 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 23.30 ± 4.96 |

| 8 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 117.05 | 23.05 ± 1.96 |

| 9 | 26.36 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 15.86 ± 0.40 |

| 10 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 32.96 | 25.08 ± 0.59 |

| 11 | 80.00 | 36.00 | 50.00 | 24.05 ± 0.30 |

| 12 | 93.64 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 21.42 ± 2.63 |

| 13 | 80.00 | 36.00 | 100.00 | 22.18 ± 1.83 |

| 14 | 80.00 | 12.00 | 100.00 | 22.58 ± 1.33 |

| 15 | 80.00 | 12.00 | 50.00 | 21.73 ± 0.20 |

| 16 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 23.32 ± 1.67 |

| 17 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 24.37 ± 2.02 |

| 18 | 60.00 | 44.18 | 75.00 | 24.37 ± 0.63 |

| 19 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 23.54 ± 0.20 |

| 20 | 60.00 | 24.00 | 75.00 | 23.60 ± 1.04 |

| Model Summary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | R-sq | R-sq(adj) | R-sq(pred) | ||

| 1.07895 | 88.20% | 77.58% | 17.23% | ||

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

| Model | 9 | 87.0311 | 9.6701 | 8.31 | 0.001 |

| Linear | 3 | 38.0033 | 12.6678 | 10.88 | 0.002 |

| Glutamic acid | 1 | 23.2282 | 23.2282 | 19.95 | 0.001 |

| Typtone | 1 | 14.1703 | 14.1703 | 12.17 | 0.006 |

| Glucose | 1 | 0.6048 | 0.6048 | 0.52 | 0.488 |

| Square | 3 | 46.6228 | 15.5409 | 13.35 | 0.001 |

| Glutamic acid*Glutamic acid | 1 | 38.5913 | 38.5913 | 33.15 | 0.000 |

| Typtone*Typtone | 1 | 7.3758 | 7.3758 | 6.34 | 0.031 |

| Glucose*Glucose | 1 | 1.1429 | 1.1429 | 0.98 | 0.345 |

| 2-Way Interaction | 3 | 2.4051 | 0.8017 | 0.69 | 0.579 |

| Glutamic acid*Typtone | 1 | 0.0242 | 0.0242 | 0.02 | 0.888 |

| Glutamic acid*Glucose | 1 | 0.8321 | 0.8321 | 0.71 | 0.418 |

| Typtone*Glucose | 1 | 1.5488 | 1.5488 | 1.33 | 0.276 |

| Error | 10 | 11.6413 | 1.1641 | ||

| Lack-of-Fit | 5 | 10.4284 | 2.0857 | 8.60 | 0.017 |

| Pure Error | 5 | 1.2129 | 0.2426 | ||

| Total | 19 | 98.6724 | |||

| Response Surface Regression: PGA Titre versus Glutamic acid, Tryptone, Glucose | |||||

| Term | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | P-Value | VIF |

| Constant | 23.491 | 0.440 | 53.38 | 0.000 | |

| Glutamic acid | 1.304 | 0.292 | 4.47 | 0.001 | 1.00 |

| Typtone | 1.019 | 0.292 | 3.49 | 0.006 | 1.00 |

| Glucose | -0.210 | 0.292 | -0.72 | 0.488 | 1.00 |

| Glutamic acid*Glutamic acid | -1.636 | 0.284 | -5.76 | 0.000 | 1.02 |

| Typtone*Typtone | -0.715 | 0.284 | -2.52 | 0.031 | 1.02 |

| Glucose*Glucose | 0.282 | 0.284 | 0.99 | 0.345 | 1.02 |

| Glutamic acid*Typtone | 0.055 | 0.381 | 0.14 | 0.888 | 1.00 |

| Glutamic acid*Glucose | -0.323 | 0.381 | -0.85 | 0.418 | 1.00 |

| Typtone*Glucose | -0.440 | 0.381 | -1.15 | 0.276 | 1.00 |

| S | R-sq | R-sq(adj) | R-sq(pred) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.985652 | 82.38% | 77.68% | 55.50% | |||

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value | |

| Model | 4 | 68.123 | 17.0308 | 17.53 | 0.000 | |

| Linear | 2 | 29.535 | 14.7674 | 15.20 | 0.000 | |

| Glutamic acid | 1 | 16.602 | 16.6022 | 17.09 | 0.001 | |

| Typtone | 1 | 12.933 | 12.9325 | 13.31 | 0.002 | |

| Square | 2 | 38.589 | 19.2943 | 19.86 | 0.000 | |

| Glutamic acid*Glutamic acid | 1 | 33.707 | 33.7068 | 34.70 | 0.000 | |

| Typtone*Typtone | 1 | 7.425 | 7.4249 | 7.64 | 0.014 | |

| Error | 15 | 14.573 | 0.9715 | |||

| Lack-of-Fit | 10 | 12.932 | 1.2932 | 3.94 | 0.072 | |

| Pure Error | 5 | 1.641 | 0.3282 | |||

| Total | 19 | 82.696 | ||||

| Regression coefficients | ||||||

| Term | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | P-Value | VIF | |

| Constant | 9.185 | 0.341 | 26.92 | 0.000 | ||

| Glutamic acid | 1.103 | 0.267 | 4.13 | 0.001 | 1.00 | |

| Typtone | 0.973 | 0.267 | 3.65 | 0.002 | 1.00 | |

| Glutamic acid*Glutamic acid | -1.522 | 0.258 | -5.89 | 0.000 | 1.01 | |

| Typtone*Typtone | -0.714 | 0.258 | -2.76 | 0.014 | 1.01 | |

| Time interval (h) | Δ γ-PGA (g/L) | Productivity (g/L·h) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 – 24 | 31.41 | 1.31 |

| 24 – 48 | 31.03 | 1.29 |

| 48 – 72 | 7.16 | 0.30 |

| 72 – 96 | 5.76 | 0.24 |

|

Strain |

γ-PGA Titre (g/L) | Productivity (g/L·h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis MJ80 | 75.5 (3L fermenters) 68.7 (300 L fermenters) |

~1.04 0.95 |

[39] |

| Bacillus licheniformis P-104 | 41.6 | 1.07 | [49] |

| Bacillus halotolerans F29 | 50.9 | 1.33 | [49] |

| Bacillus velezensis SDU | 23.1 | 0.77 | [21] |

| Bacillus subtilis ZJU-7 | 54.4 | Not reported | [36] |

| Bacillus licheniformis NCIM 2324 | 35.75 | Not reported | [27] |

| Bacillus licheniformis A14 | 37.8 | Not reported | [26] |

| Bacillus methyotrophicus SK19.001 | 35.34 | Not reported | [50] |

| Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945 | 66.1 | Not reported | [51] |

| Bacillus subtilis GXD-20 | 22.29 | Not reported | [43] |

| Bacillus tequilensis BL01 | 25.73 | 0.48 | [33] |

| Bacillus licheniformis DPC6338 | ~ 81 - 84 (bioreactor) 75 (shake flask) |

~ 1.75 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).