1. Introduction

In recent years, food systems have faced challenges due to climate change, rapid human population growth, accelerating urbanization, and epidemic surges. As a result, the global food security gained significant priority from scientific communities worldwide [

1,

2]. One of the most critical obstacles to global food security is food waste. In this line, current studies revealed that roughly 33% of total food production, corresponding to 1.3 billion tons, is discarded every year. Notably, 14% of food loss arises during post-harvest and distribution phases, while 17% is wasted through retail and consumption, representing

$750 billion/year in economic losses [

3,

4].

Owing to its perishable nature, (3-6 days shelf life), bread holds the most frequently thrown away food. Globally, ≈ 10% equivalent to 900.000 tons of bread is wasted across the entire supply chain including production, transport and consumption [

5,

6]. Meanwhile, the high demand of newly made bread exacerbates its overproduction generating daily waste [

7]. Bread’s rich nutrient composition could contribute to rapid quality loss. This latter was induced by chemical, physical and especially molds deterioration. Additionally, during the baking the starch is converted into a digestible gelatinized, susceptible to fungal attack [

8,

9].

In Tunisia, bread is a staple food and consumed daily. According to the National Institute of Consumption (INC), 42 kg of bread are wasted per household, amounting of around 113,000 tons of Tunisian bread are discarded annually [

10]. In fact, a study on “Bread consumption by Tunisian families”, proved that over 900,000 loaves are thrown daily with an estimated cost of

$50 million which affect the country’s economy [

11].

Current bread waste disposal management approaches, such as incineration, landfilling, and anaerobic digestion could pose diverse environmental issues like soil contamination and generating greenhouse gases. Further, incineration could provoke air pollution through toxic emissions, odors, and disease vectors [

12]. In response to these environmental challenges, nations admit an urgent necessity to conversion to a zero-waste strategy by 2025. Therefore, developing waste valorization technologies is essential as a core component of sustainable waste management, while concurrently improving economic rationality [

13]. In this context, innovative solutions have been investigated, including transforming stale bread into succinic acid [

14], feed animal [

15], 2,3-butanediol (BDO) [

16], bioethanol [

2], lactic acid [

17] brewing adjunct for craft beer [

18] and compost to enrich soil health [

19]. Beyond these applications, efforts have been concentrated on leveraging the nutritional profile of WB, which is made up of 10% protein and 70% carbohydrate. As an upcycled substrate, these substances performs a valued reserve for microbial processes and enzymatic synthesis, which could enhance the efficiency and eco-friendliness of biotechnological claims [

20]. Montemurroet al. [

21] used WB as substrate to generate polyhydroxyalkanoates by

Haloferax mediterranei. Similarly, Benabda et al., [

22] employed BW to enhance the microbial proliferation of

Rhizopus oryzae for the amylase and protease synthesis. Additionally, Jung et al. [

23] utilized the glucose derived from the BW enzymatic hydrolysis to the

Euglena gracilis cultivation of microalga, leading to the production of paramylon valued in medicines and cosmetics sectors. In addition to these diverse applications, the food processing industry provides openings to repurpose BW within the framework of a circular economy. For bakeries, exploiting cost-effective BW not only safeguards competitive product pricing but also removes disposal costs. In contrast, they can generate additional revenue from the selling of loaf waste [

4]. For instance, Guerra-Oliveira et al. [

24] studied the conversion of BW to make sugar snap cookies. Furthermore, BW can be transformed into sugar hydrolysate to replace sucrose in the sweeteners and confections, as bulking agents in bakery products, or processed into fructose syrup [

15,

25]. In addition, Immonem et al. [

8] revealed that BW slurry increases the viscoelasticity of the dough, decreases the water absorption by 13%, and obtains less hard bread compared to the control.

Aligned with a zero-waste industrial strategy, this study investigates the valorisation of Tunisian WB through four distinct applications: (1) as an alternative feedstock to replace conventional culture media for selected bacterial strains; (2) as a substitute for commercial starch in screening amylolytic microorganisms; (3) as a fermentation substrate to enhance amylase production; and (4) for the generation of sugar syrup via enzymatic hydrolysis using amylase (Amy-BSS) (

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

1. Waste bread preparation and characterization

WB was collected from household food waste and local bakeries (Sfax government) after its shelf life had expired or in the case of returns. The discarded bread exhibited no indications of mold, was sliced into roughly 1 cm³ pieces, and left to dry at room temperature for four days. Afterwards, the slices were blended into a fine powder using a laboratory blender and stored at 4°C until needed. The nutritional composition of the WB was assessed using analytical techniques. The moisture level was evaluated with a KERN DAB desiccator, while the ash content was performed via combustion in a muffle furnace (FLLI GALLI G/P model). Water activity was determined using a Rotronic RO-HP23-AW meter. The lipid, starch and proteins were analyzed using MPA FT-NIR spectroscopy. The gluten levels were ascertained through the Perten Glutomatic 2000 system. Finaly, the color parameters of the WB (L*, a* and b*) were recorded with Konica Minolta colorimeter. The outcomes are expressed as a percentage of dry matter.

2. Micro-organisms, medium preparation and growth conditions

Reference microorganisms namely Echerichia coli DH5α, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus were chosen for their ability to grow in conventional Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Their proliferation was tested and compared in both conventional LB (C.LB) and non-conventional media (NC1 and NC2):

1. C.LB (g/L): 10 soya peptone, 5 yeast extract, 5 NaCl

2. NC1 (g/L): 1 soya peptone, 0.5 yeast extract 0.5 NaCl, 20g waste bread

3. NC2 (g/L): 20g waste bread with no additional nutrients

14h pre-culture of each micro-organism was prepared in C.LB and used to inoculate the test media (NC1 and NC2) in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks at an initial optical density (OD) of 0.4 for 24 hours at 37°C and 200 rpm. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the OD at 600nm using a spectrophotometer. WB supernatants were used as blank for NC1 and NC2 fermentation media.

BSS strain isolated from a Tunisian biotope was used to produce amylase. Preliminary biochemical tests confirmed its classification as Bacillus species. Hence, its designation as Bacillus sp. BSS. The pre-culture was performed in basic LBS medium (C.LB+1% soluble starch) at 30°C for overnight at 180 rpm. The bacterial cultures (OD = 0.2) were conducted following the experimental matrix (16 experiments with 1 central point) and incubated for 19h at 30°C in rotary shaker.

Four amylolytic Bacillus strain (B1-B4) and E.coli DH5α (serving as negative control) were streaked in duplicate on solid WB medium (SWB) forming by C.LB +1% WB+ 1.8% agar) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Following the incubation period, the plated were treated with 1% Lugol iodine solution (1g I2 + 2g KI) for 10 minutes. The presence of starch hydrolysis zones indicated the amylase production [

26]. A positive control (plate containing LBS medium) was used to verify the effectiveness of waste bread as a starch substitute for amylase activity screening.

4. Amylase activity assay

Amylase activity of Bacillus BSS was assessed using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS). The reaction mixture consists of 0.5 ml of 1% starch (Sigma), 0.45 ml of phosphate buffer (pH =7; 0.1M) and 0.05 ml of crude enzyme, was kept at 60°C for 10 min. After incubation, 1.5 ml of DNS was added to stop the enzymatic reaction. The mixture was boiled for 10 min and 15 ml of deionized water was introduced. An independent control was prepared by mixing the substrate and DNS solution followed by the enzyme to remove all reducing sugars from the fermentation. The production of reduced sugars was determined at 550 nm. One unit of amylase activity is defined as the quantity of enzyme that extricated 1 µmol of reducing sugar per minute under the given conditions. The α-amylase activity was measured as follows:

α-amylase activity (U/ml/min) = (1)

In which 180 = molecular weight of glucose and K = conversion coefficient of the DNS which is 1.8

5. Waste Bread Enzymatic hydrolysis assay

Enzymatic hydrolysis of WB was conducted using crude amylase produced from Bacillus sp.BSS. A total of 9 experiments were carried out following a designed matrix. All experiments were carried out in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks that contained 20 ml of the various bread suspensions mixed with the enzymatic solution. After each experimental run, samples were collected and centrifuged at 8000×g for 15 minutes. The reducing sugars present in 1 ml of the hydrolyzed waste bread supernatant were measured by the DNS method, with glucose serving as the standard.

6. Fractional factorial design (FFD)

The

fractional factorial plan designed with Minitab version 2019 (64-bit, LLC Minitab), was chosen due its fewer required experiments compared to the other designs simplicity. Thus, it can conserve both time and resources. In this study, a FFD

was investigated for enhancing amylase production by Bacillus BSS (y1) and the

plan for evaluating the hydrolysis rate of WB using Amy-BSS (y2). The respective experimental variables for each response (y1 and y2) are detailed in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

The fractional factorial design led to the derivation of the subsequent empirical equation [

27]:

(2)

where β0, βi and βij are the regression coefficients for the constant, linear and interaction coefficients. y is the response, and are the independent variables and ε is the experimental error. In FFD, the interaction effects among three or more variables are presumed to be inconsequential.

7. Statistical analysis and model adequacy

The adequacy of the regression model was assessed through multiple statistical parameters. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s test (F-value) assessed the overall model significance. Individual variable relevance and bi-interactions were judged using p-value and Student’s test (t-test) at a 95% confidence range. The coefficient of determination R², including the R²-predicted and R²-adjusted indicates the goodness of model fit, with values closer to 100% suggesting higher prediction accuracy. The experimental designs were carried out in consistent conditions within a single block of measurements, and the sequence of the experiments was kept non-randomized to reduce the impact of uncontrolled variables. All the experiments were conducted in n=3 ± standard deviation (SD).

8. Material cost calculation (Techno-economic assessment)

The available price on the Sigma Aldrich website (accessed on April 16, 2025) was used to estimate the cost of additional ingredients for media. The cost assessment was derived by computing the required material quantity, as detailed below:

(3)

(4)

(5)

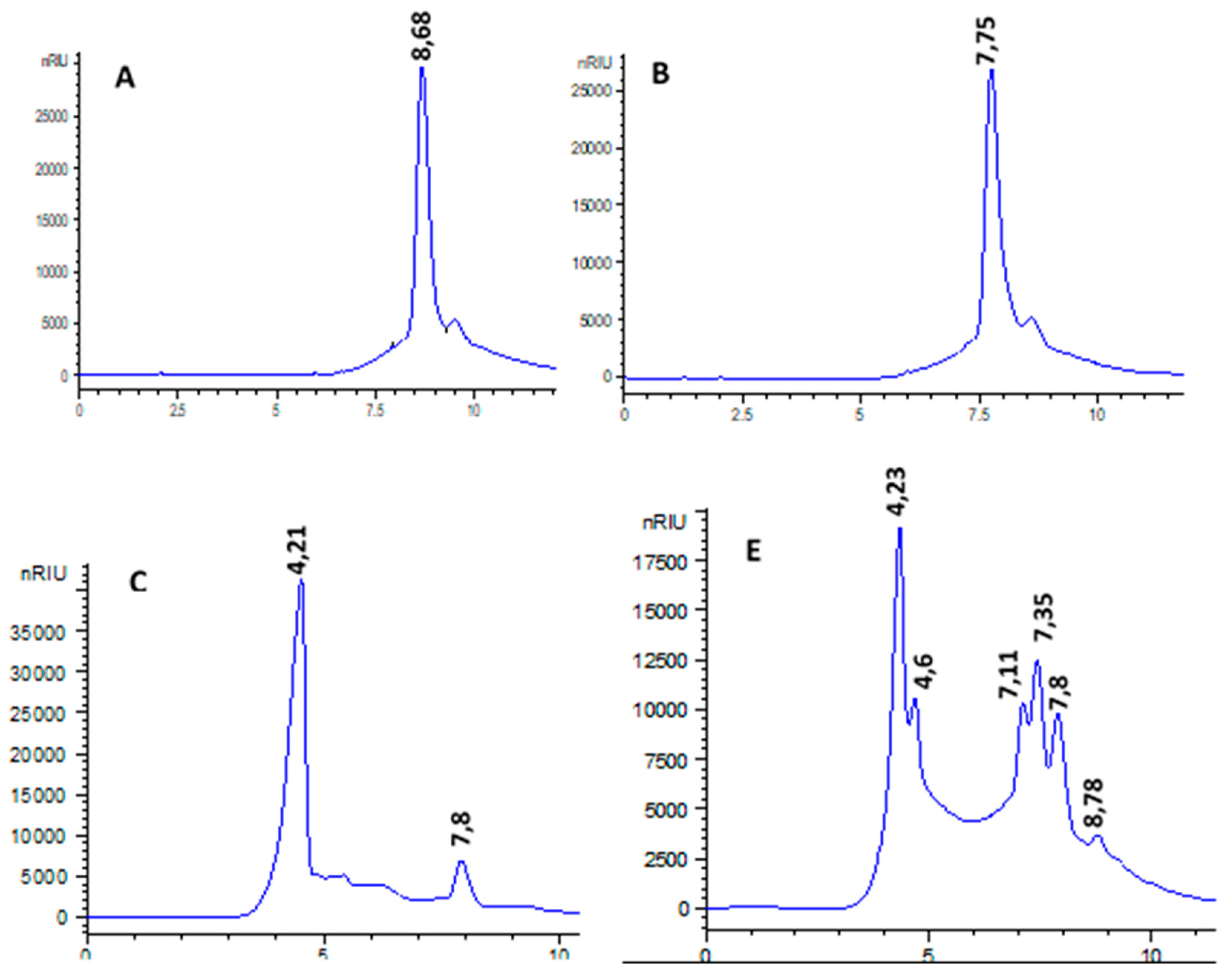

9. High performance liquid chromatography HPLC

The products of starch hydrolysis from waste bread (1%) after 1h, 2h and 3h of hydrolysis were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC Agilent 1100). The samples were halted by boiling for 5 minutes, filtered through a 0.22 mm membrane and applied to the HPLC system carbohydrate column (Shodex sugar KS-802H901093; 8mm × 300mm). Isocratic water was the mobile phase with an elution rate of 1ml per min throughout the analysis. Detection was performed using the Retractive index detector (Waters RI 401). The hydrolysis products were assigned by comparison with standard glucose, maltose and unhydrolysed WB.

3. Results

1. Waste Bread characterization

The proximate analysis of the waste bread is summarized in

Table 3. The WB showed a moisture content of 17.17% and water activity of 0.761, suggesting moderate microbial stability. Starch is the dominant component (61.41%) with an intermediate protein quantity (8.88%). The light color of WB (L> 75) with minor yellow-red tints (a*= 2.67, b*= 15.81) indicates negligible heat deterioration. These characteristics highlight the expired bread’s potential as a feedstock for microbial fermentation, enzymatic hydrolysis, and nutrients recovery.

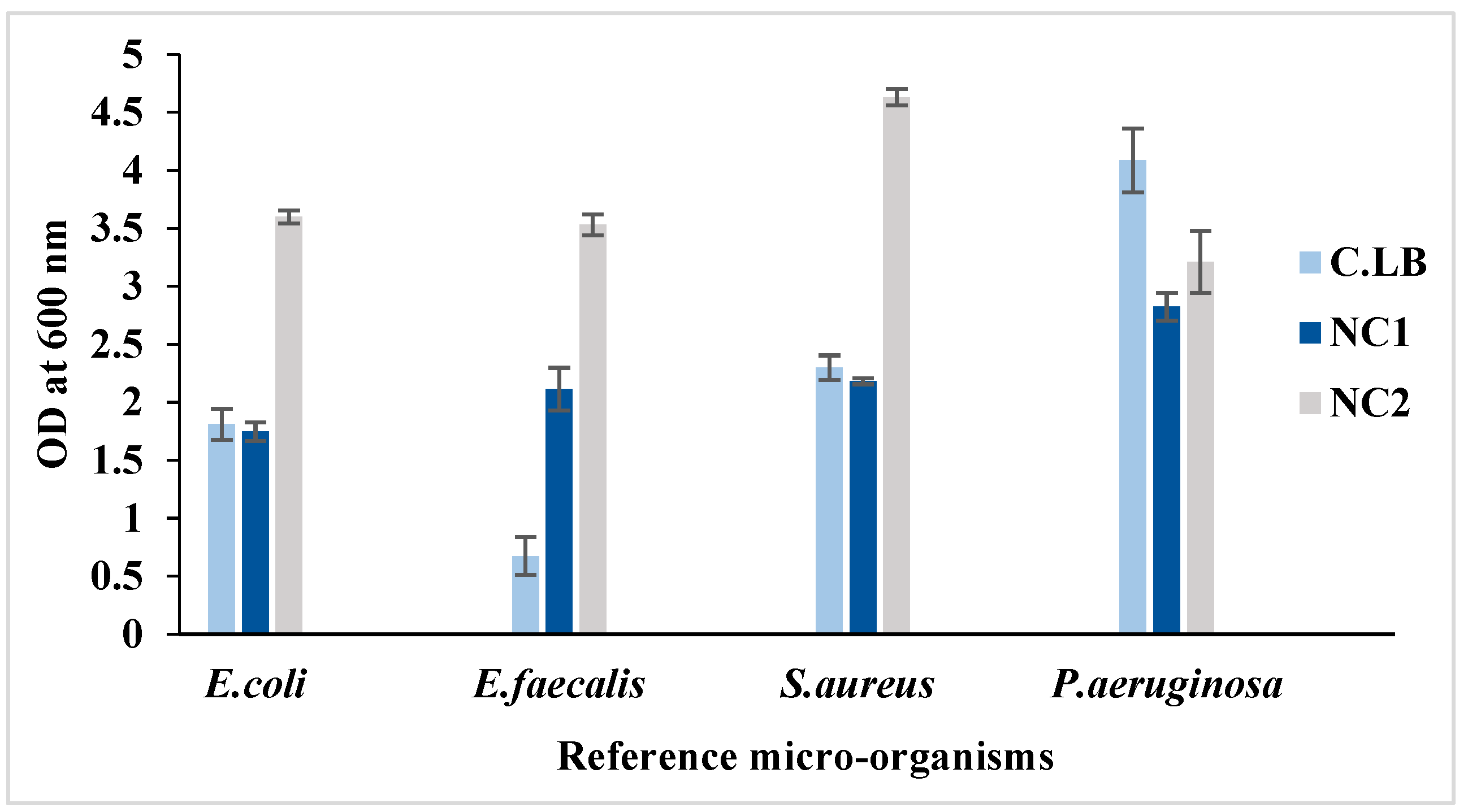

2. Waste Bread for bacterial growth

In this study, two types of bread waste-based medium (NC1 and NC2) were formulated to test bacterial proliferation. The growth of E

. coli, E. faecalis,

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa was assessed after 24h of incubation at 37°C. Microbial growth was investigated in diluted culture media. In

Figure 2, it can be observed that E. coli displayed a twofold increase in NC2 medium (3.6) compared to CLB (1.81). Strikingly,

E. faecalis demonstrated a fivefold enhancement in NC2 (3.53 vs. 0.675 in CLB), while S. aureus exhibited the highest growth rate in NC2 (4.63), surpassing its growth in both CLB and NC1. Though P. aeruginosa thrived best in CLB (4.085), it also showed considerable growth in WB (OD 3.21). These results imply that WB effectively meets the nutritional needs of various bacterial strains, making it a promising alternative culture medium. Notably, the NC1 formulation resulted in only modest growth rates for all microorganisms tested.

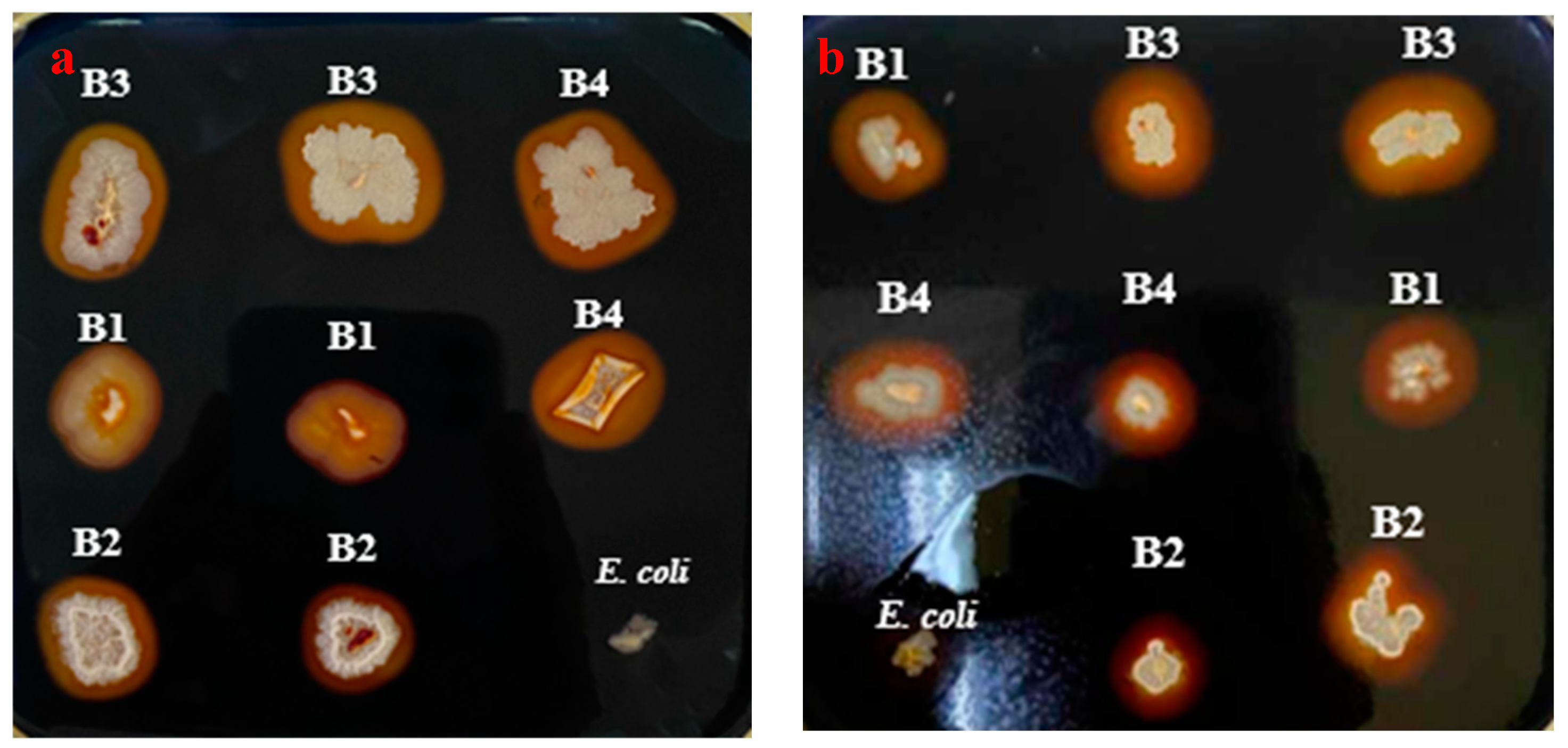

3. Waste Bread for amylolytic strains screening

To assess the amylolytic potential of

Bacillus strains (B1-B4), waste bread plates (SWB) were employed as the only supplier of starch in the screening assay. After an overnight incubation at 37°C, plates were flooded with iodine solution, revealing various transparent halos around positive bacterial colonies, indicative of starch hydrolysis (

Figure 3 a,b). However, quantitative analysis demonstrates a relevant difference in enzymatic activity between SWB and LBS plates. Notably, hydrolysis zone diameters in the LBS plate were larger for all the

Bacillus strains (B1: 0.55, B2: 0.45, B3: 0.7, and B4: 0.65 cm) respectively, against (0.25, 0.35, 0.6, and 0.55 cm) in the SWB plate. Despite these variations, using waste bread as a substrate for amylolytic strain screening preserved detection sensitivity, as the patterns of clearance zones stayed like those seen in commercial starch agar.

4. Fractional factorial design (FFD)

4.1. The for the Optimization of Amylase Production

Two levels were assigned to each variable as indicated in

Table 1. A total of 16 trials plus 1 central points were conducted to determine how the five chosen factors influence the amylase production. The measured response of the Amy-BSS activities is indicated in table 4. Amylase activity varied depending on the fermentation conditions ranging from 3.76 U/ml to 8.75 U/ml. The best enzymatic activity was achieved in trials 1 and 6 with 8.75 U/ml and 8.78 U/ml, respectively. It’s worth noting that the initial activity of the Amy-BSS in non-optimized medium (conventional LBS) was recorded as 0.69 U/ml. An improvement of ≈ 13 times -folds proves the efficiency of this experimental plan.

Table 4.

Matrix of design in coded levels for amylase production with experimental values.

Table 4.

Matrix of design in coded levels for amylase production with experimental values.

| Run order |

Yeast extract (A) |

Soya peptone (B) |

NaCl (C) |

Waste bread (D) |

Wheat starch (E) |

Amy-BSS activity (U/ml) |

| 1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

8.75 ± 0.32 |

| 2 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

7.58 ± 0.53 |

| 3 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

5.95 ± 0.57 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

8.35 ± 0.36 |

| 5 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

7.53 ± 0.45 |

| 6 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

8.87 ± 0.36 |

| 7 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

3.76 ± 0.20 |

| 8 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

7.42 ± 0.28 |

| 9 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

5.85 ± 0.85 |

| 10 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

5.11 ± 0.60 |

| 11 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

5.41 ± 0.53 |

| 12 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

5.57 ± 0.36 |

| 13 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4.62 ± 0.36 |

| 14 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

8.27 ± 0.50 |

| 15 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

6.73 ± 0.39 |

| 16 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

4.59 ± 0.42 |

| 17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5.70 ± 0.10 |

To determine the significant effect of the main variables and their two-way interactions, ANOVA was performed. The significance of variables is judged by its p-value close to 0 indicates high significance. From

Table 5, all the main factors are significant having the same p-value =0 except for the NaCl which had p value of 0.46 > 0.05. Conversely, yeast extract (A), soya peptone (B), waste bread (D) and wheat starch (E) showed a different F-values of 46.79; 70.21; 131.72 and 27.03 respectively.

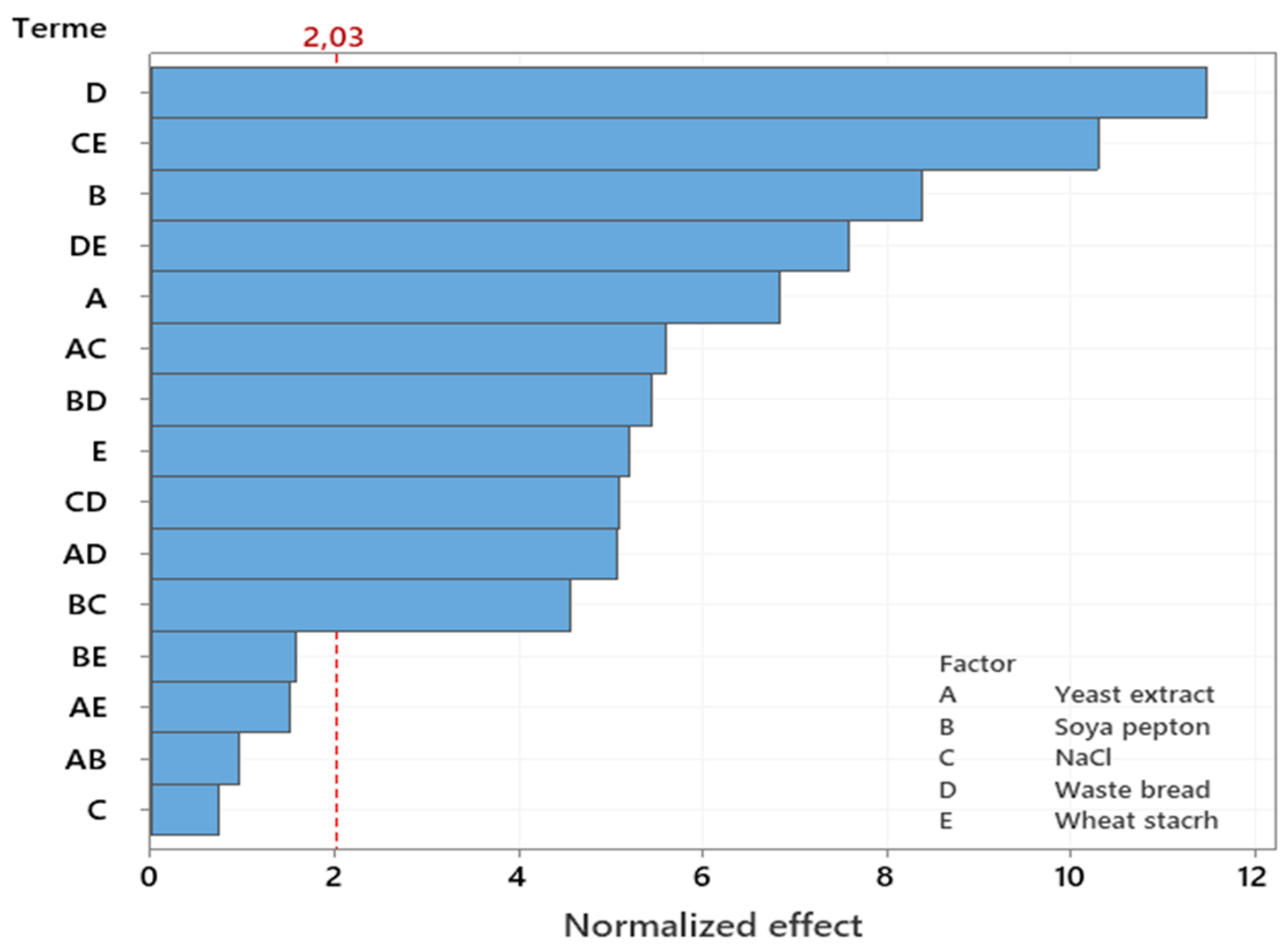

This enables the use of a Pareto chart to visually analyze the impact of the most influential factor. The vertical line on the Pareto chart represents the minimum effect size that is statistically significant for a 5% significance level, while the lengths of the horizontal bars correspond to the level of significance for each effect. Any effect or interaction that surpasses the vertical line is deemed significant. The Pareto chart (

Figure 4) clearly reveals the high influence of WB on the improving of Amy-BSS production following the soya peptone (A), yeast extract (B) and wheat starch (E). WB had the greatest effect on enzyme production owing to its high starch content, which is a perfect inducer of amylase synthesis. Although the NaCl (C) itself was not significant. In contrast, its interaction with yeast extract (A×C), soya peptone (B×C), waste bread (D×C) and wheat starch (E×C) significantly affected the enzymatic production. Thus, these interactions were ranked by

F-value as follows: (C×E), (A×C), (C×D) and (B×C) with

F-values of 105.83>31.29>25.86>20.82 respectively (table 5), suggesting their substantial contribution to the response (y

1).

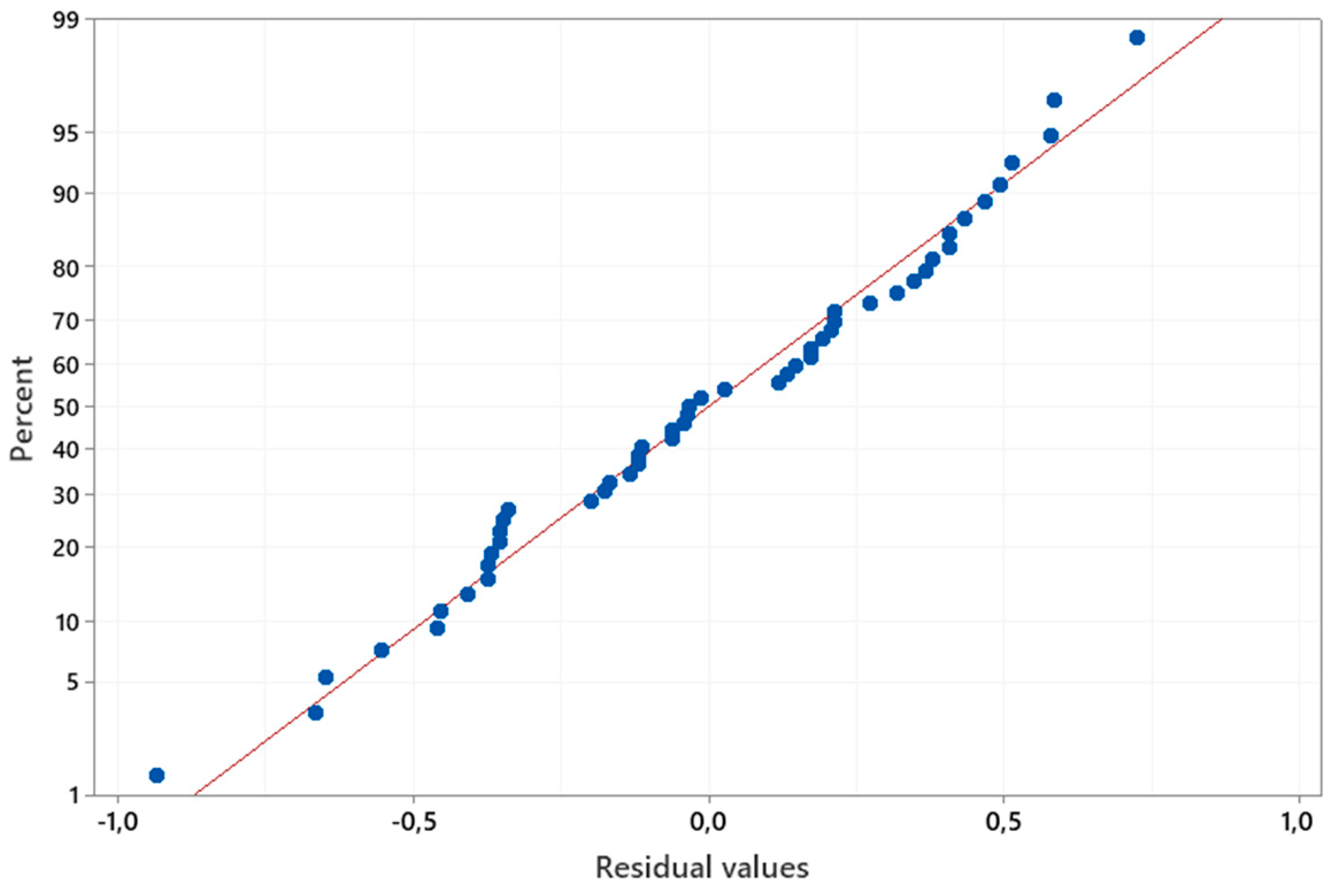

The ranking of the main and interaction effects regarding their impact on amylase production aligned with the normal probability plot of standardized effects (

Figure 5). Additionally, the plot indicates that all data points are normally distributed around a mean of zero and adhere to a straight line.

The mathematical model corresponding to this design is given by the equation:

y1= 5.61 + 2.36 A – 4.79 B + 3.08 C + 0.666 D + 7.75 E + 1.01 A×B + 5.86 B×C -2.658 B×D + 1.6 A×E - 4.78 B×C +2.852 B×D -1.66 B×E + 2.665 C×D -10.78 C×E – 0.823

The goodness of fit was evaluated using ANOVA, which yielded an F-value of 36.75 and a p-value of 0. Moreover, the coefficient of determination R2 equal to 0.9453 means that 94.53% of the observed variation is attributed to the variable effects. Thus, it can be concluded that the predicted model (R2pred= 87.7%) fits well with the experimental data (R2adj = 91.96%). This set of results demonstrates clearly the validity of the model.

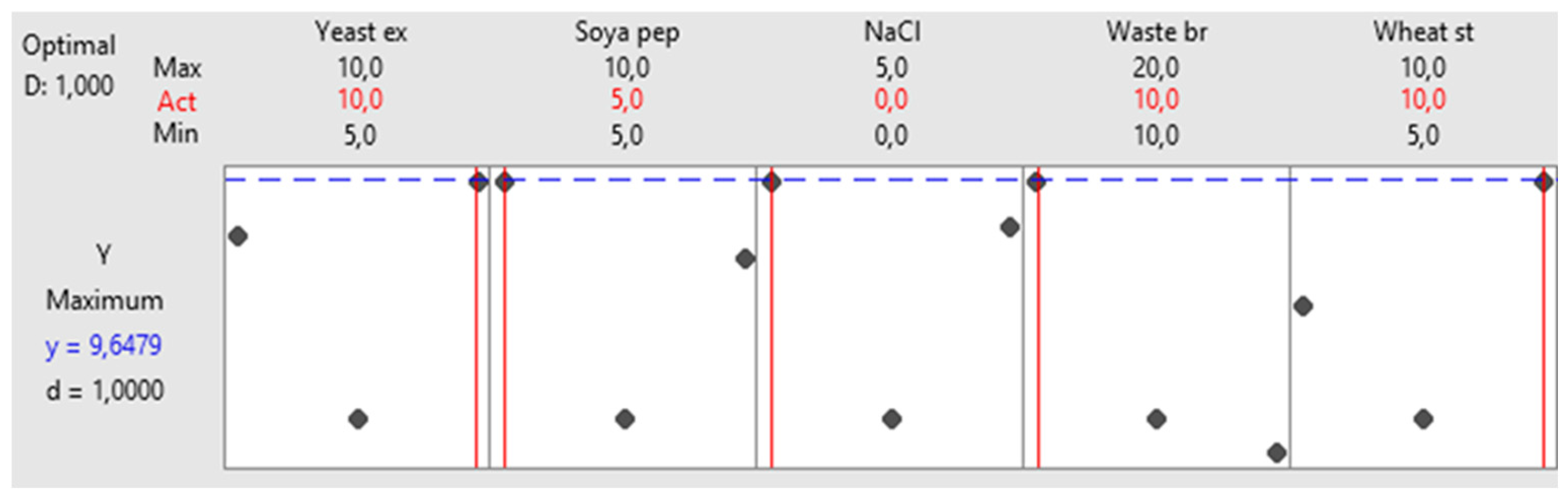

Figure 6 shows the optimized levels for the chosen variables. It is observed that the ideal values for yeast extract, soya peptone, NaCl, waste bread and wheat starch are 10,5,0,10 and 10 g/L, respectively, achieving an amylase activity of 9.64 U/ml with a desirability of d=1. To ensure the reproducibility of this composition, three independent experiments were executed. An amylase activity of 8.96 ± 0.32 U/ml was obtained, close to the predicted value, confirming the suitability of the method.

4.2. The for the Enzymatic Waste Bread Hydrolysis

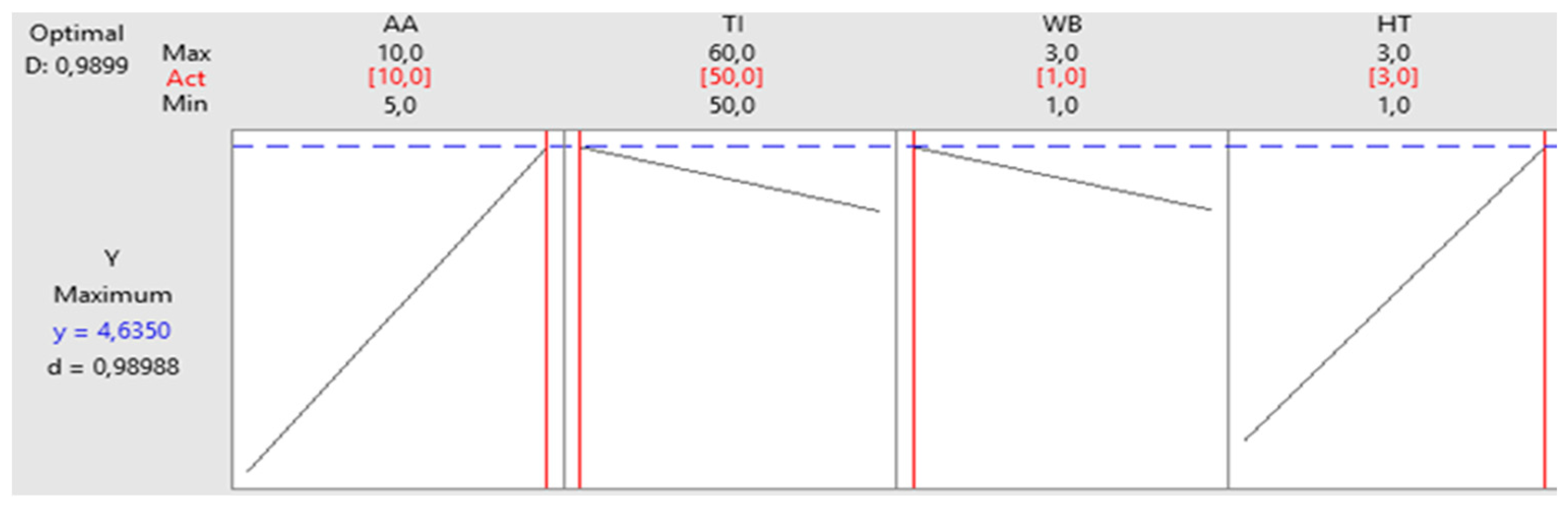

Optimal conditions for enzymatic hydrolysis of WB by Amy-BSS was defined by 2_V^(4-1) fractional factorial design. Four parameters amylolytic activity (X1), incubation temperature (X2), waste bread concentration (X3) and hydrolysis time (X4) were varied at two different levels to investigate their effects and interactions on reducing sugar yield.

Table 6 groups the measured experimental responses corresponding to the 8 tests runs. The highest amount of released sugar was 4.635 g/L obtained in run 2 using the 10 U of Amy-BSS, 50°C incubation temperature, 1% of WB and during 3 hours of hydrolysis time.

This result was confirmed as optimal as demonstrated by

Figure 7, which shows the highest reducing sugar under this condition.

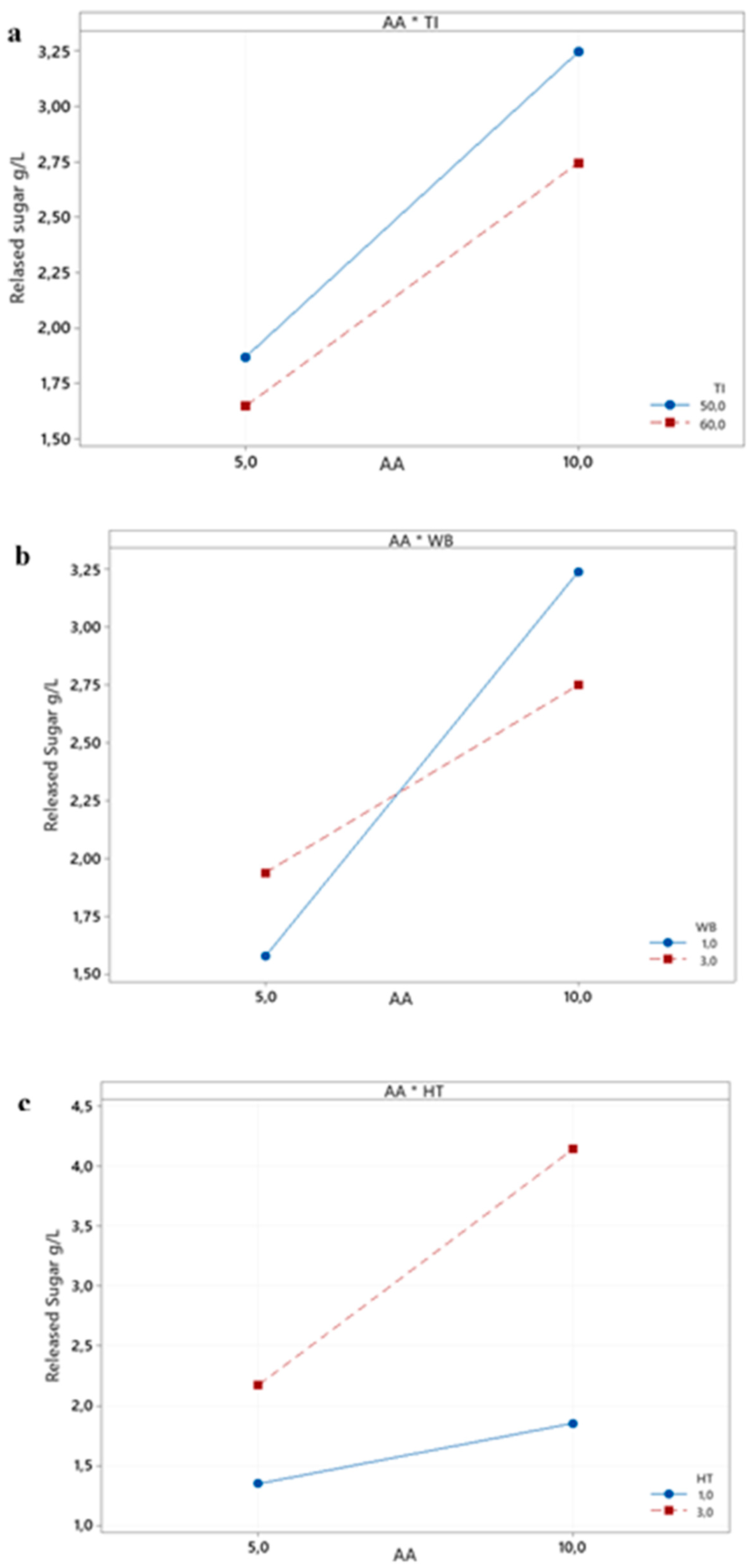

*AA: amylase activity, TI: temperature of incubation, WB: waste bread, HT: hydrolysis time

The statistical significance of each individual factor and their combinations at α = 5% were evaluated using ANOVA. As shown in

Table 7, the main (X1, X2, X3, X4) and interaction effects (X1×X2), (X1×X3), and (X1×X4) are statistically significant (p = 0). Among these, hydrolysis time (X4) was identified as the most influential factor, as indicated by the highest F-value (4962.75). Additionally, its interaction with amylolytic activity (X1×X4) showed the most significant interaction, with an F-value of 1103.06.

The interaction plot, shown in

Figure 8, displays the fitted meaning of the reducing sugar yield versus combinations of X

1 with X

2, X

3, and X

4. The analysis results indicate that the lines are not parallel, confirming that the interactions are statistically significant.

A first-order polynomial model was used to describe the correlation between the four tested variables and the hydrolysis yield. The fit of the data is described as follows:

y2 = -0.367 +0.4320 X1 + 0.00575 X2 + 0.60701 X3 – 0.3221 X4 – 0.005583 (X1×X2) – 0.08525 (X1×X2) + 0.14658 (X1×X3) + 0.14658 (X1×X4)

The validity of the adjusted model was assessed based on the results in

Table 7. The regression analysis indicates that the model is highly significant, with a very low p-value (p = 0) and a high F-value (1226.51).

y2= -0.367 +0.4320 X1 +0.00575 X2 + 0.60701 X3 – 0.3221 X4 – 0.005583 (X1×X2) – 0.08525 (X1×X2) + 0.14658 (X1×X3) + 0.14658 (X1×X4)

Meanwhile, the coefficient of determination (R² = 99.83%) indicates that only 0.17% of the total variability was not explained by the model, suggesting that the considered variables were sufficient to make reliable predictions. Additionally, the small difference between the adjusted R² (99.74%) and the estimated R² (99.59%) demonstrates a strong correlation between the estimated and experimental data.

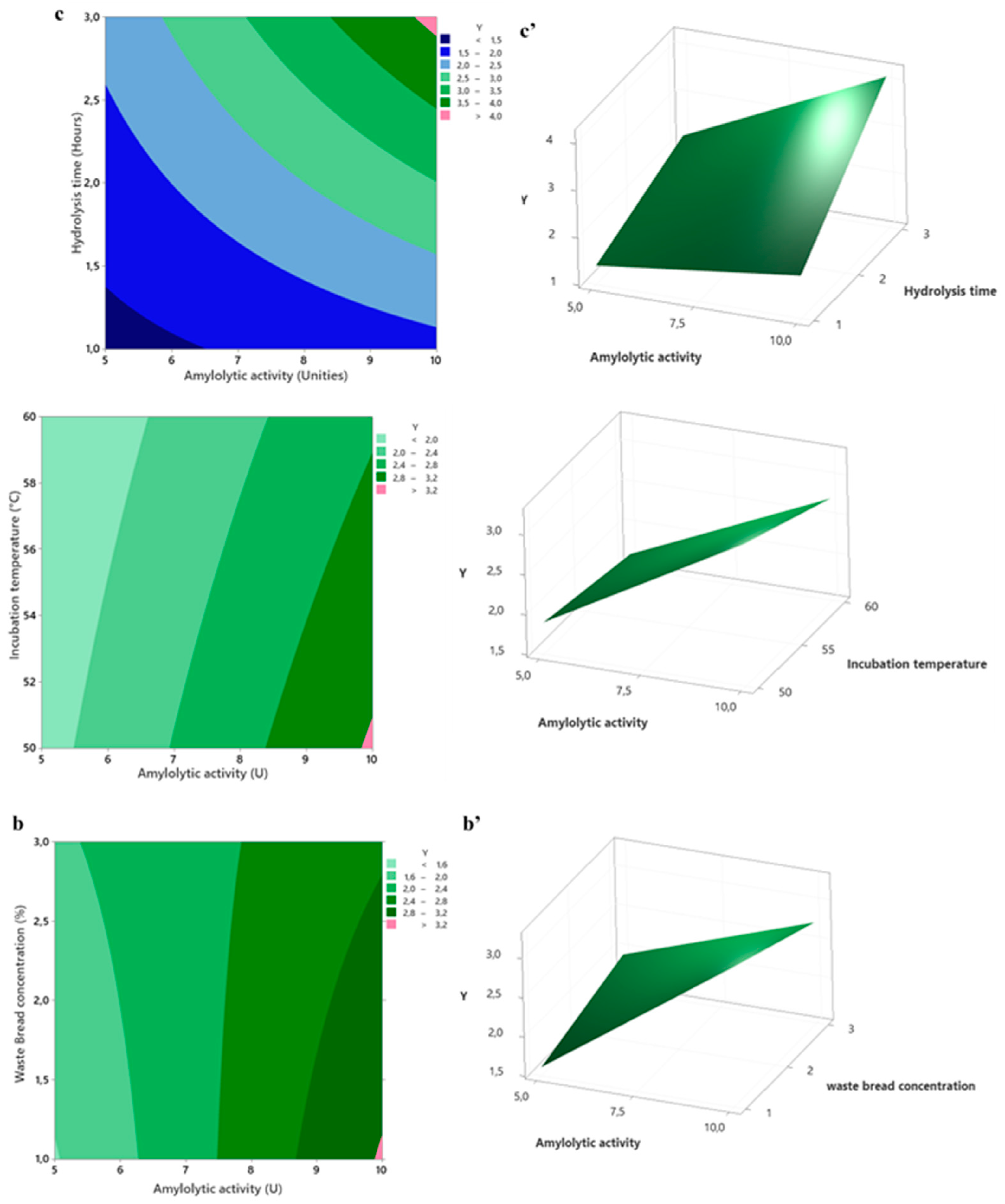

The influence of the selected variables can be visualized by the contour and surface plots (

Figure 8). These graphs are powerful tools for understanding the influence of these variables and the observed data. In this study, the plots were generated by holding two of the independent variables as a constant at level 0, while the two other variables were changing.

Figure 9(a) and (b) illustrate the interaction between the (amylase units × incubation temperature) and (Amylase units × waste bread concentrations), respectively. The results indicate that both the WB concentration and the total activity of Amy-BSS significantly influence the final hydrolysis yield. The highest yield of fermentable sugars (>3.2 g/L shown in the bottom corner pink area) was achieved when amylase activity ranged from 5 U to 10 U with a substrate concentration of 1%. This concentration enhances enzyme accessibility to starch bonds, promoting efficient hydrolysis. A similar trend is observed in the interaction between amylase activity and temperature (

Figure 9.b). To achieve a high yield of reducing sugars, 50°C was found to be more effective than 60°C. This may be due to the risk of enzyme denaturation at higher temperatures. Importantly, this result highlights an added benefit: operating at 50°C requires less energy for heating, making the process more cost-effective.

Figure 9.c shows that the hydrolysis rate is highest in the top corner of the contour plot, where a high concentration of Amy-BSS (10 U) is combined with an extended hydrolysis time (3 hours). This result can be explained by the fact that when the amylase concentration is low, the reaction rate is limited due to the reduced number of enzyme molecules available to act on the starch substrate.

However, the three interactions surface plots (

Figure 9a', b', and c') display a flawlessly flat plane devoid of curvature. This finding implies that the two factors combined effect is just the total of their separate effects

5. High performance liquid chromatography HPLC

HPLC analysis revealed that glucose, and other sugars with a degree of polymerization (DP) ≥ 3 were the final products of WB starch. It appears that the amylase generated by Bacillus sp.BSS is an endoamylase. Indeed, its action on WB starch primarily produces oligosaccharides with a DP≥3, along with a fraction of glucose and maltose.

Figure 10.

Hydrolysis products of 3% WB using 10U of amyBSS. (A): glucose solution 5 mg/mL; (B), maltose solution 5 mg/mL; (C): 3% of unhydrolysed WB; (D): Hydrolysed WB by amyBSS.

Figure 10.

Hydrolysis products of 3% WB using 10U of amyBSS. (A): glucose solution 5 mg/mL; (B), maltose solution 5 mg/mL; (C): 3% of unhydrolysed WB; (D): Hydrolysed WB by amyBSS.

4. Discussion

The growing global population has led to an increase in food quantities, resulting in a surge in food waste (FW). This is an aftermath of an absolute linear economy model. Unless nowadays, the circular economy has gained traction as a sustainable alternative. It enables FW recycling in the industrial process via new technologies. This approach aligns with the concept ‘cradle to cradle” where the recycled materials retain their features and can be re-introduced to the environment without harm [

28]. Bread ranks as the most discarded food waste globally due to its rapid spoilage. Its valorization through multiple biological approaches offers a promising pathway for circular economy forward.

To develop effective valorization approaches, a comprehensive waste stream analysis is required. Hence, characterization study (

Table 3) shows that WB contains 61.41% starch, which is in accordance with Kumar et al. [

4], who reported a content of 50-70%. Additionally, the moisture content (17.17 %) and water activity (0.761) are critical parameters affecting bread stability. In food processing, moisture content influences preservation, storage, packaging, and transportation. Thus, the high level leads to mold growth within 3-7 days. Our outcomes are in close agreement with Gobbetti et al. [

29], who reported a water activity of about 0.97. Notably, the ash quantity, 0.64%, was significantly lower than 6.74% observed by Abidin et al. [

30].

Given its rich starch content and nutrient profile, WB serves as an attractive low-cost substrate for fermentation [

31]. In general, bacterial cultivations are achieved successfully using conventional medium, such as Luria Bertani broth (LB). However, LB is exorbitant due to the elevated-cost components such as yeast extract, soya peptone and beef extract which are the basic nitrogen additives [

13]. The development of an alternative growth media using WB aims to balance between cost effective medium and good biomass yields. The used strains (

E. coli, E. faecalis, S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa ) were routinely cultured in LB. Interestingly, our results have shown superior microbial growth in the novel formulated media (NC1 and NC2) compared to LB. This result validates WB as cheaper nitrogen source for growth medium. Our findings are in concordance with Verni et al. [

5] who confirm WB’s efficacy as a nutrient rich growth medium for starter yeasts and fungi surpassing classical media. Meanwhile, lactic acid bacteria [

13] and fungi [

32] showed also significant microbial growth on the WB-based medium. Conversely, some researchers have used enzymatic pretreatment of WB before it was incorporated in the fermentation media. For instance, Carsanba et al. [

33] treat WB with amylase, glucoamylase and protease before it use to cultivate

Yarrowia lipolytica strain K57. However, such pretreatments boost the cost of the fermentation procedure, which opposes the goal of waste recovery for cost savings. Above all, when comparing CLB with NC1, we showed that the costs of the fermentation medium could be reduced by 90 %, and with NC2, the expenses could be eliminated completely. Additionally, expired bread can successfully substitute pure starch for screening amylolytic bacteria, as was previously shown. Further, using SWB instead of LBS reduces costs by 46.68% (

Table 8).

Habitually, the production of α-amylase has relied on submerged fermentation using starch as an exclusive carbon and energy supplier. However, this conventional source faces significant economic challenges, as the cost of the carbon source constitutes a major portion of amylase production expenses. This restriction often makes the process unfeasible economically [

31]. To address this challenge, exploring agro-waste as a substitute substrate is one of the solutions. These wastes naturally occurred carbon storage acting as an energy source throughout microbial fermentation [

34]. This results in a promising option for economical industrial amylase production. The use of agricultural waste such moong husk + soybean cake, rice bran and groundnut shell have been reported as media supplements in α-amylase production for

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens KCP2,

Bacillus tequilensis TB5,

Aspergillus, respectively [

35,

36,

37]. Recently, WB has sparked as a promising fermentation feedstock for enzymatic synthesis due to its richness in carbohydrate, calories, proteins and essential vitamins [

38]. This nutritional profile has been investigated in this study as ideal energy and carbon sources for Amy-BSS production.

To further optimize and reduce the cost of amylase production, a fractional factorial design was employed in this study to systematically evaluate the effects of key process variables. Unlike full factorial or response surface designs, it requires fewer experimental runs while still revealing valuable insights into key variables. When executing 17 runs (

Table 4), it has been found that WB significantly improves Amy-BSS production from 0.69 U/ml to 8.96 U/ml. This enhancement confirms that WB is a valuable carbon/substrate source. Furthermore, based on the optimized response (

Figure 5), it was demonstrated that a low level of soy peptone was sufficient, reducing the need for a high quantity of nitrogen sources due to the compensatory effect of WB. Additionally, the absence of NaCl needed for Amy-BSS production suggests that

Bacillus BSS’s sodium requirement was met by the inherent salt quantity present in the WB. Moreover, bread contains the key amino acids (nicotinic acid, thiamine, biotin, and pantothenic acids), as reported by Abd-Elhalim et al. [

39]. These elements support

Bacillus Bss growth while minimizing dependence on synthetic amino acid supplementation. The re-purpose of WB lowers Amy-BSS production cost, further preserving bacterial biomass yield. The biggest advantage of WB is its independence from harvest season, unlike the other agro residues contributing to the circular economy year-round.

Alternatively, to apply waste bread in food processing, its modification through hydrolysis is crucial. Hydrolysis breaks the complex configuration of WB starch into fermentable sugars that can be easily converted into valuable food supplements. As opposed to lignocellulosic waste, WB is a more efficient source of fermentative sugars due to its high starch quantity [

33]. Notably, sugar generated from WB is without inhibitors, commonly found in the lignocellulosic compounds [

2]. Nevertheless, the starch WB can be hydrolyzed using enzymatic or acid hydrolysis [

40]. Commonly, dilute acid hydrolysis through either HCl or H₂SO₄ has been applied to cleave glycosidic bonds, yielding lower molecular carbohydrates [

41]. However, chemical hydrolysis demands excessive energy input, corrosive substances, and severe operating settings, which can generate harmful byproducts. In contrast, enzymatic pretreatment provides a more sustainable and eco-friendly method. Enzymes are highly effective in cleaving starch under mild conditions (40 to 50°C). Therefore, enzymatic hydrolysis consumes and hydrolyzes with no toxic substance compared to the chemical approach [

17,

42]. Commercial enzymes, namely α-amylase (Grindamyl A14000), amyloglucosidase (Grindamyl PlusSweet), maltogenic amylase (MALT), and protease (Corolase 7089), were investigated for the enzymatic hydrolysis of WB as reported by Rosa-Sibakov et al. [

15]. Yet, to make an economical process, substituting commercial enzymes with house laboratory enzymes is crucial. Therefore, we have prioritized the use of Amy-BSS for this purpose. As evidenced by the 2_V^(4-1) frational factorial design, the reducing sugar yield through WB hydrolysis was signifincanlty depend on hydrolysis time, Amy-BSS unities, WB ration and incubation temperature. Our results proved that fermentable sugar production increased with longer time and higher Amy-BSS unities which is in accordance with Abidin et al. [

30]. In addition, Mihajlovski et al. [

43] reported that hydrolysis yield was influenced by fermentation time and WB concentration. In contrast, in our findings, 1% of WB is optimal because higher substrate increases viscosity, thereby restricting Amy-BSS action. Further, incubation temperature (50°) showed a positive effect which contradicts the Kahlouche et al. [

44] results.

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the fermentable sugars produced through Amy-BSS activity were primarily glucose, along with sugars having a DP≥3 , demonstrate promising potential for reuse in new bread-making applications. It has been demonstrated that certain strains, including

Bacillus species and

Leuconostoc mesentroides, may convert waste bread into mannitol, a sugar alcohol used in the food sector [

45]. Mihajlovski et al. [

43] identified maltose, glucose maltotriose as main sugars products generated during WB hydrolysis using enzymes from

Hymenobacter sp. CKS3. In a in a nutshell, by substituting conventional sugar with sugar syrup from enzymatic WB hydrolysis, the food industry, especially bakers, can drastically lower production costs. These syrups can completely replace standard sugars in the making of bread, boost shelf-life through improved hygroscopicity and crumb tenderization, as well as flavor and crust color via Maillard reactions [

15]. Such practical incorporation of bread waste-derived components offers bakeries a scalable solution to align production with both financial and environmental goals.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant potential of Tunisian WB as a valuable substrate for various value-added bioprocesses, supporting its role in progressing of the circular economy. WB-based media formulations established extraordinary cost-effectiveness, reducing the expenses of traditional LB media by 90% while simultaneously boosting microbial growth by at least twofold. Furthermore, incorporating just 1% WB efficiently replaced commercial starch in the screening of amylolytic strains, confirming its suitability as a sustainable alternative. Through process optimization using fractional factorial design (FFD), amylase activity of the Amy-BSS strain was enhanced by 15 times, reaching 8.96 U/mL, and the WB was confirmed as the most powerful factor. Additionally, enzymatic hydrolysis of WB using Amy-BSS under mild conditions (50°C for 3 hours) yielded 4.6 g/L of fermentable sugars, underlining WB's efficiency as a source material for bio-based product generation.

Collectively, these findings finalized that the Tunisian WB was a robust and cost-efficient reserve for biotechnological innovation, assisting to sustainable waste management and the progress of circular bioeconomy strategies.

Author Contributions

Sameh Ben Mabrouk: Conceptualization, Inversigation, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft; Bouthaina Ben Hadj Hmida: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft Wejdene Sallami and Salma Dhaoudi: Methodology; Theodoros Varzakas, Slim Smaoui writing, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Mr. Bouassida Hichem from Tunisian food production company (STPA) for his help on the WB composition analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tamasiga, P.; Ouassou, E.H.; Onyeaka, H.; Bakwena, M.; Happonen, A.; Molala, M. Forecasting disruptions in global food value chains to tackle food insecurity: The role of AI and big data analytics – A bibliometric and scientometric analysis. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hafyan, R.H.; Mohanarajan, J.; Uppal, M.; Kumar, V.; Narisetty, V.; Maity, S.K.; Sadhukhan, J.; Gadkari, S. Bread waste valorization: a review of sustainability aspects and challenges. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1334801. [CrossRef]

- Aït-Kaddour, A.; Hassoun, A.; Tarchi, I.; Loudiyi, M.; Boukria, O.; Cahyana, Y.; ...; Khwaldia, K. Transforming plant-based waste and by-products into valuable products using various "Food Industry 4.0" enabling technologies: A literature review. Sci. Total Environ 2024, 176872.

- Kumar, V.; Brancoli, P.; Narisetty, V.; Wallace, S.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Dubey, B. K.; ... ; Taherzadeh, M. J. Waste bread – a potential feedstock for sustainable circular biorefineries. Bioresour Technol 2023, 369, 128449.

- Verni, M.; Minisci, A.; Convertino, S.; Nionelli, L.; Rizzello, C.G. Wasted Bread as Substrate for the Cultivation of Starters for the Food Industry. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 293. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Soni, R.; Singh, L.P.; Mor, R.S. A Simulation Approach for Waste Reduction in the Bread Supply Chain. Logistics 2023, 7, 2. [CrossRef]

- Asqardokht-Aliabadi, A.; Sarabi-Aghdam, V.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Hosseinzadeh, N. Postbiotics in the Bakery Products: Applications and Nutritional Values. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 17, 292–314. [CrossRef]

- Immonen, M.; Maina, N.H.; Wang, Y.; Coda, R.; Katina, K. Waste bread recycling as a baking ingredient by tailored lactic acid fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 327, 108652. [CrossRef]

- Narisetty, V.; Cox, R.; Willoughby, N.; Aktas, E.; Tiwari, B.; Matharu, A.S.; ...; Kumar, V. Recycling bread waste into chemical building blocks using a circular biorefining approach. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 4842–4849.

- African Manager. Available online: https://en.africanmanager.com/113000-tons-of-bread-is-thrown-away-in-tunisia-every-year/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Ben Rejeb, I.; Baraketi, S.; Charfi, I.; Khwaldia, K.; Gargouri, M. Valorization of bread waste, a nonconventional feedstock for starch extraction using different methods: a comparative study. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 1485–1498. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.K.; Singh, R.; Shrivastava, M.; Darjee, S.; Mageshwaran, V.; Phurailtpam, L.; Rohatgi, B. Microbial production of α-amylase from agro-waste: An approach towards biorefinery and bio-economy. Energy Nexus 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Iosca, G.; Turetta, M.; De Vero, L.; Bang-Berthelsen, C.H.; Gullo, M.; Pulvirenti, A. Valorization of wheat bread waste and cheese whey through cultivation of lactic acid bacteria for bio-preservation of bakery products. LWT 2023, 176. [CrossRef]

- Gadkari, S.; Kumar, D.; Qin, Z.-H.; Lin, C.S.K.; Kumar, V. Life cycle analysis of fermentative production of succinic acid from bread waste. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 861–871. [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Sibakov, N.; Sorsamäki, L.; Immonen, M.; Nihtilä, H.; Maina, N.H.; Siika-Aho, M.; Katina, K.; Nordlund, E. Functionality and economic feasibility of enzymatically hydrolyzed waste bread as a sugar replacer in wheat bread making. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16378. [CrossRef]

- Narisetty, V.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Lin, C.S.K.; Tong, Y.W.; Show, P.L.; Bhatia, S.K.; Misra, A.; Kumar, V. Fermentative production of 2,3-Butanediol using bread waste - A green approach for sustainable management of food waste. Bioresour Technol 2022, 358, 127381.

- Cox, R.; Narisetty, V.; Nagarajan, S.; Agrawal, D.; Ranade, V.V.; Salonitis, K.; ...; Kumar, V. High-level fermentative production of lactic acid from bread waste under non-sterile conditions with a circular biorefining approach and zero waste discharge. Fuel 2022, 313, 122976.

- Dall'Acqua, K.; Klein, M.P.; Tech, B.I.; Fontana, A.; Crepalde, L.T.; Wagner, R.; ...; Sant'Anna, V. Understanding the utilization of wasted bread as a brewing adjunct for producing a sustainable wheat craft beer. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 66.

- Cacace, C.; Rizzello, C.G.; Brunetti, G.; Verni, M.; Cocozza, C. Reuse of wasted bread as soil amendment: bioprocessing, effects on alkaline soil and escarole (Cichorium endivia) production. Foods 2022, 11, 189.

- Sigüenza-Andrés, T.; Pando, V.; Gómez, M.; Rodríguez-Nogales, J.M. Optimization of a Simultaneous Enzymatic Hydrolysis to Obtain a High-Glucose Slurry from Bread Waste. Foods 2022, 11, 1793. [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.; Salvatori, G.; Alfano, S.; Martinelli, A.; Verni, M.; Pontonio, E.; ...; Rizzello, C.G. Exploitation of wasted bread as substrate for polyhydroxyalkanoates production through the use of Haloferax mediterranei and seawater. Front. Microbiol 2022, 13, 1000962.

- Benabda, O.; M’hir, S.; Kasmi, M.; Mnif, W.; Hamdi, M. Optimization of Protease and Amylase Production by Rhizopus oryzae Cultivated on Bread Waste Using Solid-State Fermentation. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.M.; Jung, S.; Song, H.; ...; Choi, Y.E. Zero-waste strategy by means of valorization of bread waste. J. Clean. Prod 2022, 365, 132795.

- Guerra-Oliveira, P.; Belorio, M.; Gómez, M. Waste Bread as Main Ingredient for Cookie Elaboration. Foods 2021, 10, 1759. [CrossRef]

- Riaukaite, J.; Basinskiene, L.; Syrpas, M. Bioconversion of waste bread to glucose fructose syrup as a value-added product. FOODBALT Conference Proceedings 2019, 120-124.

- Andualem, B. Isolation and screening of amylase producing thermophilic spore forming Bacilli from starch rich soil and characterization of their amylase activities using submerged fermentation. Int. Food Res. J 2014 21(2).

- Beldjoudi, S.; Kouachi, K.; Bourouina-Bacha, S.; Lafaye, G.; Soualah, A. Kinetic study of methyl orange decolorization by the Fenton process based on fractional factorial design. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2020, 130, 1123–1140. [CrossRef]

- Dymchenko, A.; Geršl, M.; Gregor, T. Trends in waste bread utilisation. Trends Food Sci.Technol 2023, 132, 93-102.

- Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Calasso, M.; Archetti, G.; Rizzello, C.G. Novel insights on the functional/nutritional features of the sourdough fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 103–113. [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.Z.; Hassan, S.R.; (AdBiC), U.M.K.A.I.B.C. Kinetic Studies of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Pre-Treatment of Waste Bread Under Preliminary Conditions. J. Eng. Sci. Res. 2023, 7, 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Ibenegbu, C.C.; Leak, D.J. Simultaneous saccharification and ethanologenic fermentation (SSF) of waste bread by an amylolytic Parageobacillus thermoglucosidasius strain TM333. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Svensson, S.E.; Bucuricova, L.; Ferreira, J.A.; Filho, P.F.S.; Taherzadeh, M.J.; Zamani, A. Valorization of Bread Waste to a Fiber- and Protein-Rich Fungal Biomass. Fermentation 2021, 7, 91. [CrossRef]

- Carsanba, E.; Agirman, B.; Papanikolaou, S.; Fickers, P.; Erten, H. Valorisation of Waste Bread for the Production of Yeast Biomass by Yarrowia lipolytica Bioreactor Fermentation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 687. [CrossRef]

- Werle, L.B.; Abaide, E.R.; Felin, T.H.; Kuhn, K.R.; Tres, M.V.; Zabot, G.L.; Kuhn, R.C.; Jahn, S.L.; Mazutti, M.A. Gibberellic acid production from Gibberella fujikuroi using agro-industrial residues. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, B.; Prajapati, V.; Patel, K.; Trivedi, U. Kitchen waste for economical amylase production using Bacillus amyloliquefaciens KCP2. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 26, 101654. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.S.; Beliya, E.; Tiwari, S.; Patel, K.; Gupta, N.; Jadhav, S. Production of biocatalyst α-amylase from agro-waste ‘rice bran’ by using Bacillus tequilensis TB5 and standardizing its production process. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 26. [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, M.; Fari, H. I.; Tiamiyu, B. B.; Salam, O. L. Optimizing α-amylase production from locally isolated Aspergillus species using selected agro waste as substrate. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Commun 2022, 15, 424-430.

- Zain, M.Z.M.; Shori, A.B.; Baba, A.S. Potential Functional Food Ingredients in Bread and their Health Benefits. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 12, 6533–6542. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhalim, B. T.; Gamal, R. F.; El-Sayed, S. M.; Abu-Hussien, S. H. Optimizing alpha-amylase from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens on waste bread for effective industrial wastewater treatment and textile desizing through response surface methodology. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 19216.

- Mazaheri, D. Valorization of Zymomonas mobilis for bioethanol production from waste bread: optimization of the enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation processes. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2025. [CrossRef]

- Torabi, S.; Satari, B.; Hassan-Beygi, S.R. Process optimization for dilute acid and enzymatic hydrolysis of waste wheat bread and its effect on aflatoxin fate and ethanol production. Biomass- Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 11, 2617–2625. [CrossRef]

- Banu, J.R.; Merrylin, J.; Usman, T.M.; Kannah, R.Y.; Gunasekaran, M.; Kim, S.-H.; Kumar, G. Impact of pretreatment on food waste for biohydrogen production: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 18211–18225. [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovski, K.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S. Enzymatic hydrolysis of waste bread by newly isolated Hymenobacter sp. CKS3: Statistical optimization and bioethanol production. Renew. Energy 2020, 152, 627–633. [CrossRef]

- Kahlouche, F.Z.; Zerrouki, S.; Bouhelassa, M.; Rihani, R. Experimental optimization of enzymatic and thermochemical pretreatments of bread waste by central composite design study for bioethanol production. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 3436–3450. [CrossRef]

- Sadeqi, V.; Astani, A.; Khanafari, A. Investigating the possibility of microbial production of mannitol from waste bread. Iran. J. Health Saf. Environ 2016, 3(3), 587-591.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the different use of Tunisian waste bread investigated in this study.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the different use of Tunisian waste bread investigated in this study.

Figure 2.

Bacterial growth of the reference microorganisms in different culture media (C.LB, NC1 and NC2).

Figure 2.

Bacterial growth of the reference microorganisms in different culture media (C.LB, NC1 and NC2).

Figure 3.

Screening assay of amylolytic strains after incubation at 37°C for overnight (a) Bacillus strains incubated on SWB plate (b) Bacterial colonies on LBS plate.

Figure 3.

Screening assay of amylolytic strains after incubation at 37°C for overnight (a) Bacillus strains incubated on SWB plate (b) Bacterial colonies on LBS plate.

Figure 4.

Standard Pareto chart of the normalized effect for the Amy-BSS production.

Figure 4.

Standard Pareto chart of the normalized effect for the Amy-BSS production.

Figure 5.

Normal probability plot for the occurred data.

Figure 5.

Normal probability plot for the occurred data.

Figure 6.

Optimal factors setting for the optimized response of Amy-BSS production.

Figure 6.

Optimal factors setting for the optimized response of Amy-BSS production.

Figure 7.

Optimized response Design and data responses resulting for the plan.

Figure 7.

Optimized response Design and data responses resulting for the plan.

Figure 8.

The interactions plot of the enzymatic WB hydrolysis (a) (Amylase unities × Temperature of incubation) (b) (Amylase unities ×WB concentration) (c) (Amylase unities ×Hydrolysis time).

Figure 8.

The interactions plot of the enzymatic WB hydrolysis (a) (Amylase unities × Temperature of incubation) (b) (Amylase unities ×WB concentration) (c) (Amylase unities ×Hydrolysis time).

Figure 9.

The contour and surface plots for the WB enzymatic hydrolysis. Contour plots (a) (X1×X2), (b) (X1×X2) and (c) (X1×X4), Surface plots (a’) (X1×X2), (b’) (X1×X2) and (c’) (X1×X4).

Figure 9.

The contour and surface plots for the WB enzymatic hydrolysis. Contour plots (a) (X1×X2), (b) (X1×X2) and (c) (X1×X4), Surface plots (a’) (X1×X2), (b’) (X1×X2) and (c’) (X1×X4).

Table 1.

Levels of factors assessed in the optimization of amylase production (

Table 1.

Levels of factors assessed in the optimization of amylase production (

| Variables (g/L) |

Level -1 |

Level 0* |

Level 1 |

| A : Yeast extract |

5 |

7.5 |

10 |

| B : Soya peptone |

5 |

7.5 |

10 |

| C : NaCl |

0 |

2.5 |

5 |

| D : Waste Bread |

10 |

15 |

20 |

| E : Wheat starch |

5 |

7.5 |

10 |

Table 2.

Variables and experimental domains in the WB hydrolysis (

Table 2.

Variables and experimental domains in the WB hydrolysis (

| Variables |

Unity |

Level -1 |

Level 1 |

| X1 : Amylolytic activity |

Unities (U) |

5 |

10 |

| X2 : Incubation temperature |

°C |

50 |

60 |

| X3 : Waste Bread concentration |

% |

1 |

3 |

| X4 : Hydrolysis time |

Hours (h) |

1 |

3 |

Table 3.

Compositional analysis of Tunisian White Bread waste.

Table 3.

Compositional analysis of Tunisian White Bread waste.

| Property |

Quantity per % |

| Moisture |

17.17 |

| Ash |

0.64 |

| Water Activity |

0.761 |

| Lipids |

2 |

| Starch |

61.41 |

| Proteins |

8.88 |

| Gluten |

Wet gluten 17.59 %

Dry gluten 8.08

Gluten index 59 % |

| Instrumental color |

Lightness (L*) 74.98

Red-green (a*) 2.67

Yellow-bleu (b*) 15.81 |

Table 5.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the plan.

Table 5.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the plan.

| Source |

DL |

F-value |

p-value |

| Model |

16 |

36.75 |

0 |

| Main factors |

5 |

55.26 |

0 |

| Yeast extract (A) |

1 |

46.79 |

0 |

| Soya peptone (B) |

1 |

70.21 |

0 |

| NaCl (C) |

1 |

0.56 |

0.46 |

| Waste bread (D) |

1 |

131.72 |

0 |

| Wheat starch (E) |

1 |

27.03 |

0 |

| Interaction 2 factors |

10 |

30.24 |

0 |

| A×B |

1 |

0.93 |

0.342 |

| A×C |

1 |

31.29 |

0 |

| A×D |

1 |

25.73 |

0 |

| A×E |

1 |

2.32 |

0.137 |

| B×C |

1 |

20.82 |

0 |

| B×D |

1 |

29.60 |

0 |

| B×E |

1 |

2.52 |

0.122 |

| C×D |

1 |

25.86 |

0 |

| C×E |

1 |

105.83 |

0 |

| D×E |

1 |

57.52 |

0 |

Table 6.

Design and data responses resulting to the plan.

Table 6.

Design and data responses resulting to the plan.

| Run |

Amylase activity |

Incubation temperature |

Waste bread |

Hydrolysis time |

Hydrolysis yield |

| 1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1.277 ± 0.099 |

| 2 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

4.635 ± 0.049 |

| 3 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1.877 ± 0.012 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

-1 |

1.847 ± 0.015 |

| 5 |

-1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

2.460 ± 0.078 |

| 6 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

-1 |

1.857 ± 0.051 |

| 7 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

-1 |

1.417 ± 0.006 |

| 8 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3.643 ± 0.023 |

Table 7.

ANOVA for the Released sugar by Amy-BSS.

Table 7.

ANOVA for the Released sugar by Amy-BSS.

| Sorce variation |

DL |

F-value |

p-value |

| Model |

7 |

1126.51 |

0 |

| Main factors |

4 |

1945.07 |

0 |

| Amylolytic activity (X1) |

1 |

3146.82 |

0 |

| Incubation temperature (X2) |

1 |

267.98 |

0 |

| Waste bread (X3) |

1 |

8.57 |

0 |

| Hydrolysis time (X4) |

1 |

4962.70 |

0 |

| Interaction 2 factors |

3 |

472.41 |

0 |

| X1×X2 |

1 |

40.01 |

0 |

| X1×X3 |

1 |

373.09 |

0 |

| X1×X4 |

1 |

1103.06 |

0 |

Table 8.

Cost comparison of different used culture media.

Table 8.

Cost comparison of different used culture media.

| Media |

Media components |

Component cost (€/100g) |

Component used (g/L) |

Cost per unit (€) |

Total cost (€) |

| CLB |

Peptone Soya |

28 |

10 |

2.8 |

5.14 |

| Yeast extract |

33.68 |

5 |

1.68 |

| NaCl |

13.2 |

5 |

0.66 |

| NC1 |

Peptone Soya |

28 |

1 |

0.28 |

0.514 |

| Yeast extract |

33.68 |

0.5 |

0.168 |

| NaCl |

13.2 |

0.5 |

0.066 |

| Waste bread |

0 |

10 |

0 |

| NC2 |

Waste bread |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| LBS |

Peptone Soya |

28 |

10 |

2.8 |

9.64 |

| Yeast extract |

33.68 |

5 |

1.68 |

| NaCl |

13.2 |

5 |

0.66 |

| Soluble starch |

45 |

10 |

4.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).