1. Introduction

WRKY transcription factors (TFs) represent one of the largest and most important families of regulatory proteins in plants [

1]. These proteins can be classified into three major types (I, II and III) by the presence of WRKY domains (WRKYGQK) at N-termini and the configuration of zinc-finger-like motifs at C-termini [

2]. Type I contains one or two WRKY domains without zinc-finger motifs, Type II possesses WRKY domains and C2H2-type zinc-finger motifs (C-X4-5-C-X22-23-H-X-H), and Type III contains WRKY domains and C2HC-type zinc-finger motifs (C-X7-C-X23-H-X-C) [

3]. These domains enable WRKY proteins to specifically bind to W-box (TTGAC[T/C]) cis-elements in target gene promoters, allowing them to regulate diverse biological processes [

2,

3].

Extensive researches have demonstrated that WRKY TFs play a pivotal role in modulating responses to both biotic [

4,

5,

6,

7] and abiotic stresses [

8,

9,

10], as well as in developmental processes [

5,

11] and hormone signaling pathways [

6,

12,

13]. The investigations on molecular mechanisms of WRKY in model plants showed that WRKY proteins often function through protein-protein interactions, particularly with Valine-glutamine motifs (VQ-motif) containing proteins. For example,

AtVQ10 interacts with

AtWRKY8 in Arabidopsis jointly enhance resistance to

Botrytis cinerea [

14,

15]. Similar mechanisms have been observed in crops, where

MdWRKY75 in apple confers resistance to

Fusarium solani by regulating

MdERF114 expression [

5], and

VqWRKY31 in grape enhances resistance to

Erysiphe necator through salicylic acid signaling [

4]. In contrast, a more complicated module (

JrPHL8-JrWRKY4-JrSTH2L) in walnut is involved into defense to

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [

7].

Camellia oleifera, a native species to China, is widely used as a woody oil crop with highly valuable oil in seeds [

16]. However, anthracnose disease caused by the fungal pathogen

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides poses a significant threat to yield and quality, leading to substantial economic losses [

17]. Current management strategies relying on chemical fungicides are neither sustainable nor completely effective. Recently, the release of reference genomes for different ploidy

C. oleifera [

18,

19,

20], provides an opportunity to study its WRKY family, like analyses conducted in cotton and soybean [

21,

22]. These studies in other polypoid species revealed lineage-specific expansions and functional diversification of WRKY families driven by whole-genome duplication (WGD).

Despite their established importance in plant defense, the WRKY transcription factors in C. oleifera remains poorly characterized. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a comprehensive study aiming to: (1) identify and classify WRKY genes in the tetraploid C. oleifera genome; (2) analyze their structural features and evolutionary patterns; (3) investigate their expression profiles in response to C. gloeosporioides infection using resistant (CL150) and susceptible (CL102) cultivars; and (4) explore their potential roles in anthracnose resistance. Our findings provide valuable insights for establishing molecular breeding strategies to enhance disease resistance in this species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

Two clonal varieties of Camellia oleifera Abel. with different anthracnose resistance, CL150 (resistant) and CL102 (susceptible), were selected for this study. Two-year-old cuttings of both varieties were cultivated in a climate chamber. Pathogen inoculation was performed following the procedure described by Yang [

23]. Briefly,

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium for 5-7 days to make 5 mm fungus cake. Prior to inoculation, young leaves were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol followed by rinsing with sterile distilled water. Two wounds were created per leaf on either side of the midvein using a sterile needle, and each wound site was treated with 10 μL of 1% sterile glucose solution before applying a fungal disc. Control leaves received sterile PDA plugs without fungal inoculation. The post-inoculated symptom on leaves has been shown in the previous study [

16]. Three biological replicates were employed per treatment (inoculated and control) for each variety, resulting in 12 experimental samples in total (2 varieties × 2 treatments × 3 replicates). Leaf samples (500 mg) were collected at 72 hours post-inoculation (hpi) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA extraction.

2.2. Identification of WRKY Genes in Tetraploid C. oleifera Genome

The WRKY gene family was systematically identified using a dual-approach strategy combining hidden Markov model (HMM)-based searches and homology-based verification. First, the WRKY domain model (PF03106) and the protein sequences for model building (97 reviewed proteins, accessed on April 8, 2025) were obtained from InterPro database, and the complete protein sequences of tetraploid C. oleifera were retrieved from CNCB database (accession: GWHERBT00000000). Next, the HMMER software (v3.3.2) [

24] was employed to scan the

C. oleifera proteome for potential WRKY genes using the PF03106 profile with stringent parameters (-E 1e-20, --domE 1e-20). To ensure accuracy, the candidate WRKY proteins were further validated via BLASTP analysis (NCBI BLAST+ v2.12.0) against the 97 protein sequences with the parameter -evalue 1e-20. Only sequences consistently identified by both HMMER and BLASTP were retained as high-confidence WRKY genes for subsequent analysis.

2.3. Characterization and Classification of WRKY Genes

The identified WRKY genes were further analyzed to confirm the presence of conserved domains, including WRKY motif and zinc-finger structures, using InterProScan (v5.52-86.0) [

25] with default parameters. Subsequently, the WRKY genes were classified into three major types (Type I, II, and III) based on their domain architecture: Type I (lacking zinc-finger domains), Type II (containing C2H2 zinc-finger motifs), and Type III (featuring C2HC zinc-finger motifs). This classification was performed using an in-house shell script. To elucidate gene structure diversity, exon-intron organization and untranslated regions (UTRs) were determined using the tetraploid C. oleifera genome annotation file (GFF3 file).

2.4. Chromosomal Localization and Phylogenetic Analysis

The physical locations of all identified WRKY genes were extracted from the tetraploid C. oleifera genome annotation file and visualized on their respective chromosomes using the RIdeogram package (v0.2.0) [

26], enabling comprehensive analysis of their distribution patterns. For phylogenetic analysis, the full-length WRKY protein sequences were aligned using ClustalW (v2.1) [

27] with default parameters. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was then constructed using MEGA11 software [

28] with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.5. RNA-Seq and Differential Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from leaf samples using the Trizol reagent, and RNA-seq libraries were prepared and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq platform. Raw sequencing reads have been deposited in the NCBI (accession number PRJNA775660). For data analysis, raw reads were first processed using fastp (v0.23.2) [

29] to remove adapters and low-quality bases with default parameters. The resultant clean reads were then mapped to the tetroploid

C. oleifera genome using BWA-MEM (v0.7.17) [

30] with default parameters followed by gene expression quantification with featureCounts [

31]. Differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 [

32], with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 as the criteria for significantly differential expression.

2.6. Functional Annotation and Network Analysis

Due to the limited functional annotation available for the tetraploid

C. oleifera genome, we employed a comparative genomics approach using the relatively well-annotated genome of

Camellia sinensis var. Longjing 43 as a reference. The complete proteome and corresponding GO and KEGG annotations for

C. sinensis were retrieved from the Tea Plant Genome Database (

https://tpia.teaplants.cn/download.html). For functional annotation transfer, we performed protein sequence similarity searches using BLASTP (v2.12.0+) with an E-value 1e-20. The top hits (minimum identity >40%, coverage >50%) were used to assign putative GO and KEGG terms to

C. oleifera genes based on their orthologous relationships with

C. sinensis genes. This homology-based annotation approach generated a preliminary functional annotation database for tetraploid

C. oleifera. The GO and KEGG annotation analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was subsequently performed using the clusterProfiler package (v4.0.5) [

33]. Statistical significance was assessed using Fisher's exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction (FDR < 0.01).

3. Results

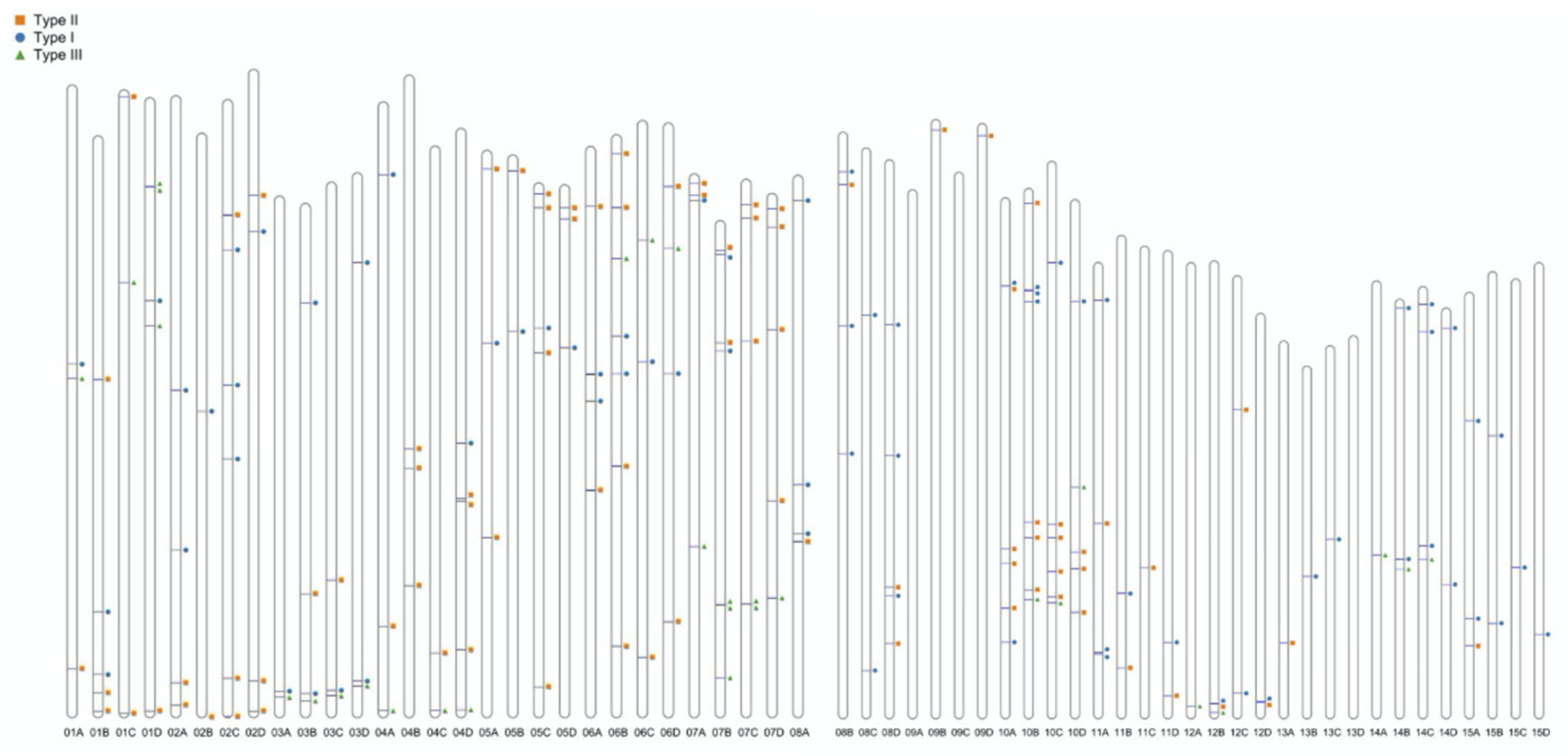

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Chromosomal Distribution of WRKY Genes

Through a comprehensive analysis combining HMMER and BLASTP approaches, a total of 192 WRKY genes were identified in the C. oleifera genome. These genes unevenly distributed along the chromosomes and across the genoome with exception of three chromosomes (no WRKY genes were identified on Chr09A, Chr09C and Chr13D), and these genes also unevenly distribute across the

C. oleifera chromosomes (

Figure 1,

Table 1). Specifically, Chr10 (all four homologous copies: -A, -B, -C and -D) had the highest number of WRKY genes (n=25), representing approximately 12.4% of the total WRKY genes. In contrast, Chr09 and Chr13 (-A, -B, -C and -D) showed the lowest density, harboring only 2-3 genes each (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

3.2. Conserved Domain and Gene Structure Analysis

In general, WRKY proteins were characterized for two typical structures: WRKY domain and zinc-finger configuration. Based on their structural characteristics, these genes were classified into three major groups (Type I, II and III). Of them, Type I (74 genes, 39% of total) contains single core WRKY domain without zinc-finger motifs; Type II (87 genes, 45% of total) are featured with one or two WRKY domains coupled with C2H2-type zinc-fingers; Type III (31 genes, 16% of total) possesses single WRKY domains and distinct C2HC-type zinc-fingers (

Figure 2A). The gene structure analysis showed that the size of WRKY genes varied significantly (1,281 - 23,094 bp) with an average length of around 4,728 bp, and no WRKY gene is intron-less (

Figure 2B). Furthermore, no new distinct pattern was found for gene structure among the types (

Figure 2B).

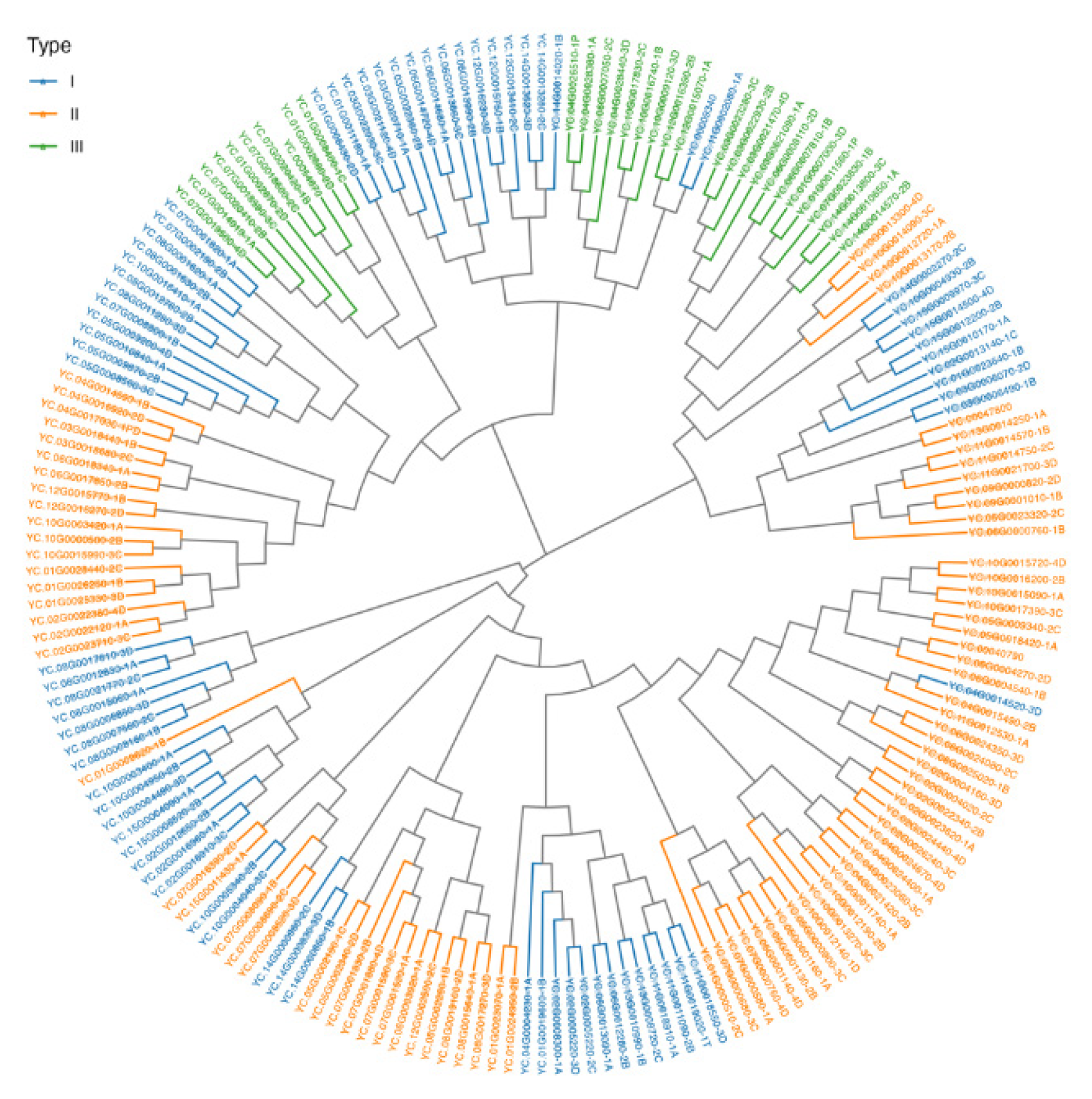

3.3. Phylogenetic Relationship of the WRKY Genes

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the full coding proteins to illustrate the relationship among WRKY genes, which have been categorized into three types (I, II, III) based on domain analysis. The tree was composed of three major clusters, where the genes belonging to different types were grouped into, and the genes belonging to the same type were grouped into one sub-cluster (

Figure 3). In specific, Type I genes (blue) exhibit significant sub-clustering, indicating recent diversification. Type II genes (orange) show some overlap with Type I, probably suggesting ancient duplication events. Type III genes (green) are more divergent, hinting at unique functional adaptations (

Figure 3).

3.4. Gene Expression Pattern of WRKY and Response to Anthracnose Infection

To examine the expression pattern of WRKY genes in response to biotic stress, two C. oleifera cultivars with contrasting disease resistance, anthracnose-resistant CL150 and susceptible CL102, were selected for expression profiling under control and pathogen stress. After obviously low expressed WRKY genes were removed, a total of 156 genes were investigated. In general, 156 WRKY genes showed different expression pattern and can be classified into six clusters. Two clusters (I and IV, in

Figure 4) displayed moderate and stable expression levels across two cultivars under two conditions, indicating a constitute expression pattern. Cluster II showed relatively higher expression levels in both cultivars and up-regulated under pathogen challenge, suggesting a potential role in defense mechanisms (

Figure 4). Two clusters (III and VI) exhibited no expression across two cultivars under control but slightly up-regulated in response to pathogen attack, which could contribute to disease defense. Additionally, the genes in Cluster V performed constant but low expression levels across two cultivars and conditions (

Figure 4).

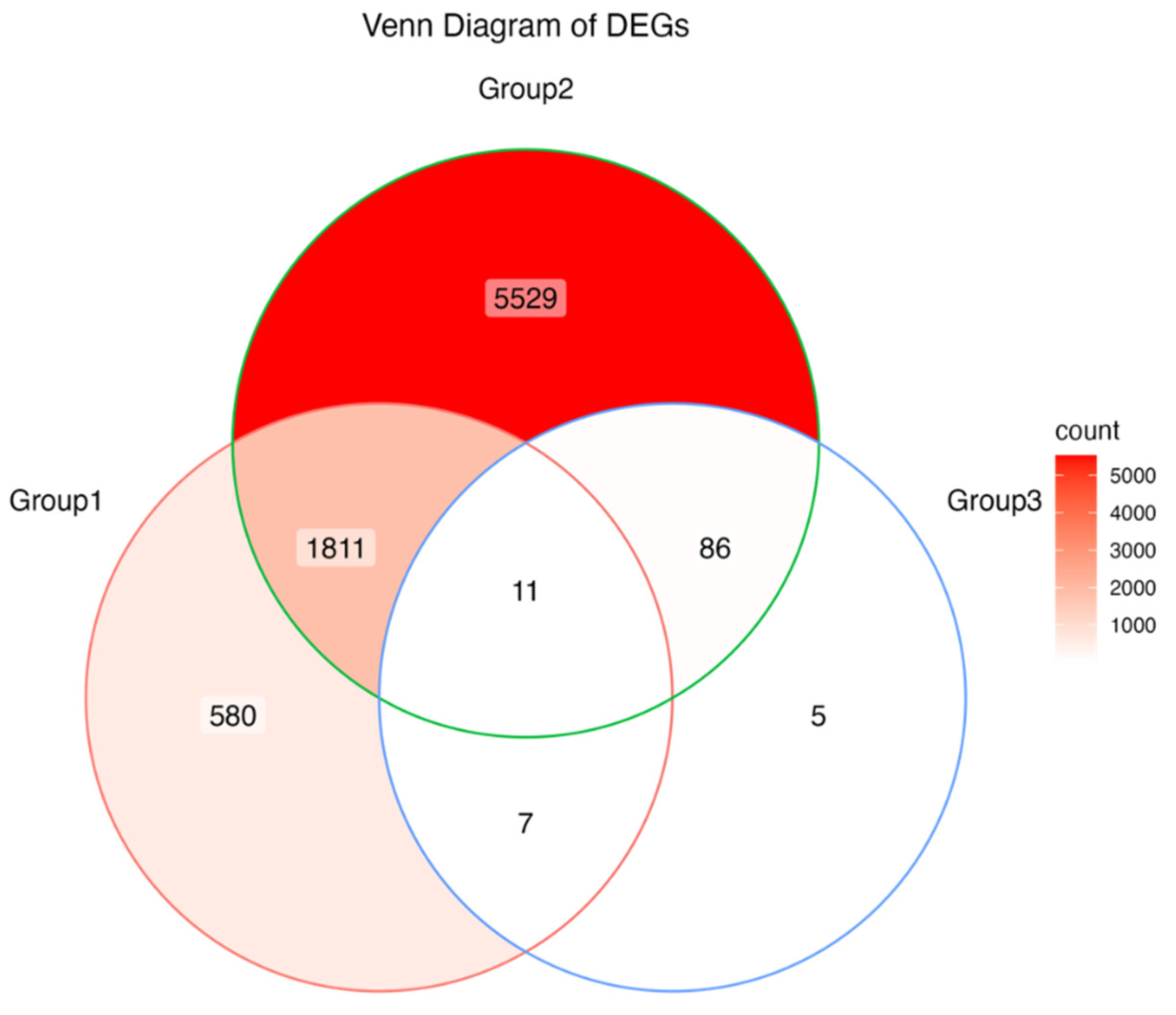

3.5. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Under Anthracnose Stress

To explore potential WRKY genes associated with resistance to anthracnose, different expression analysis was conducted on two cultivars under both control and pathogen treatment. A total of 12 samples including biological replicates were investigated for expression level. First, the principal component analysis (PCA) on all samples demonstrated that both genotypes/cultivars and treatment effect contribute to the variation of gene expression levels (

Supplementary Figure S1). Second, a total of 1,822 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were detected in response to anthracnose by both cultivars (

Figure 5). Functional enrichment analysis revealed that these genes mainly function as enzymes such as hydroxylase and oxidase (

Supplementary Figure S2). Furthermore, a large proportion of them were found to be involved into the defense related biological processes such as cysteine biosynthetic process from serine (GO:0006535), glutathione metabolic process (GO:0006749), hydrogen peroxide catabolic process (GO:0042744) as well as defense response to bacterium (GO:0042742) (

Supplementary Figure S2).

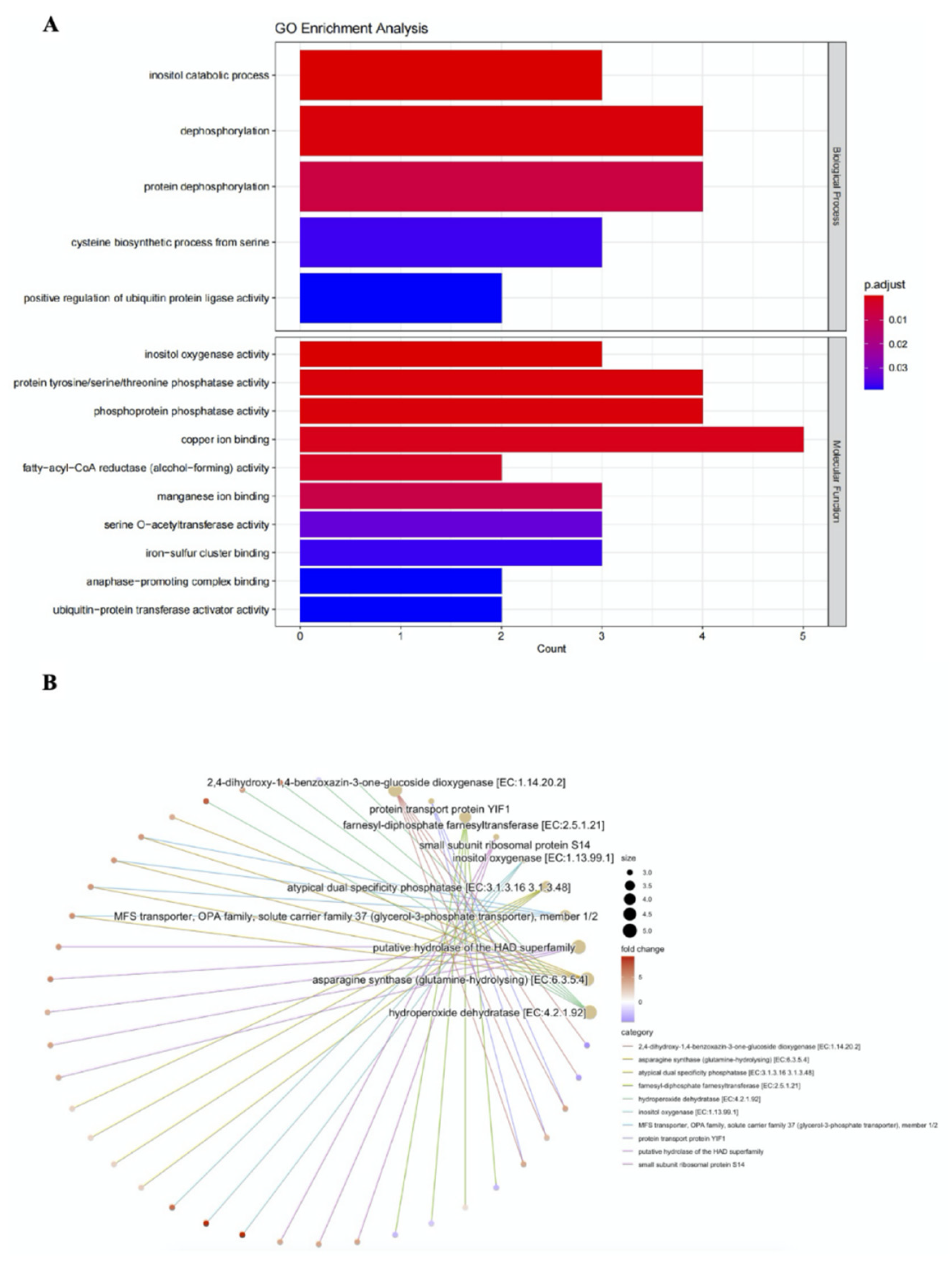

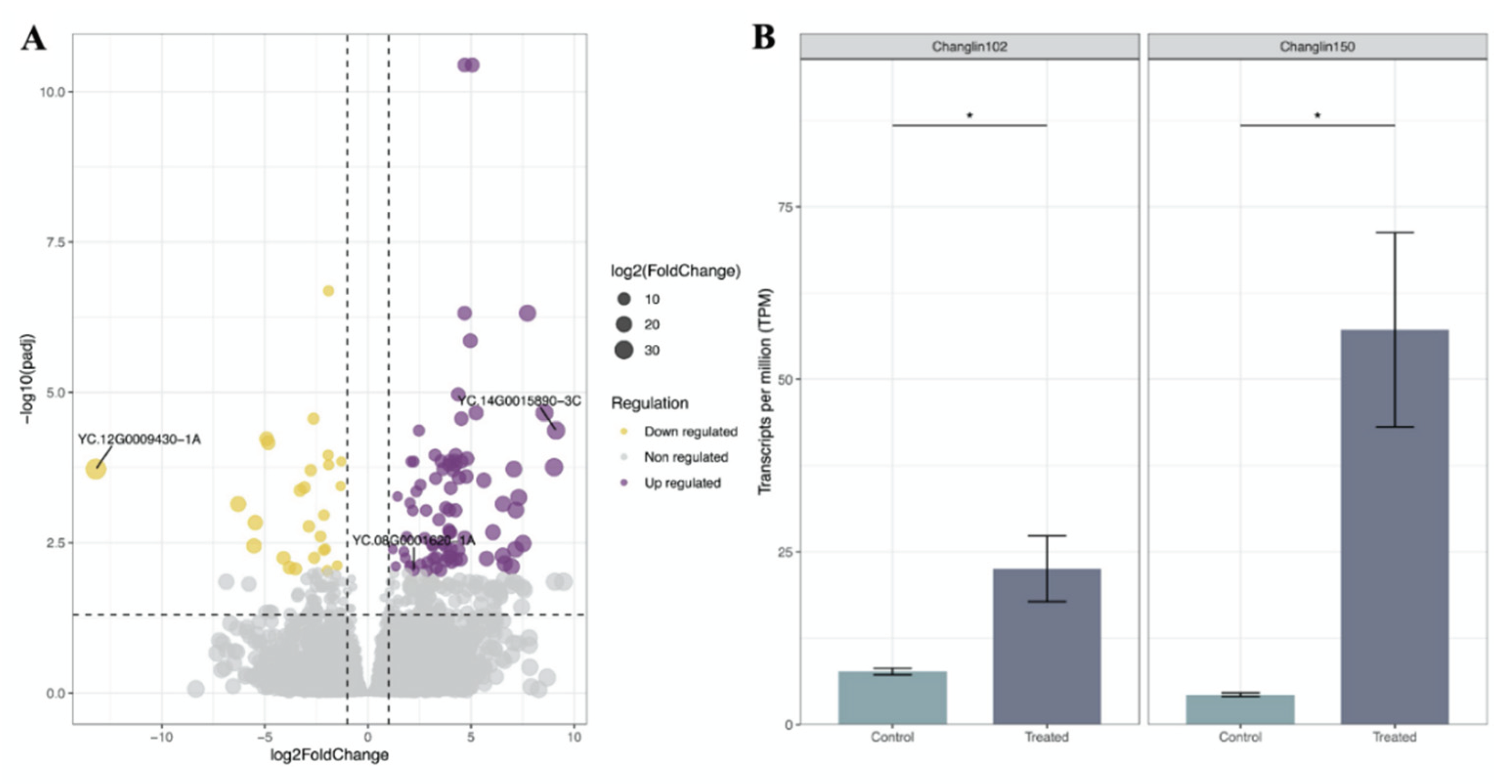

3.6. A Candidate WRKY Gene Involved into Resistance to Anthracnose

In order to investigate DEGs distinct to the resistant material (CL150), a further analysis was performed to compare CL102 and CL150 subjected to the disease, the number of 109 DEGs were detected and showed distinct expression pattern (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Figure S3). These genes mainly function as phosphatase, oxygenase and transcriptional factor involved in the biological processes including inositol catabolism and protein dephosphorylation (

Figure 6A). Furthermore; KEGG analysis revealed most of these genes are responsible for the pathways such as hydroperoxide dehydration, glutamine-hydrolysing and dioxygenation of glucoside (

Figure 6B). Regarding to expression regulation, 83 genes of 109 DEGs (76%) were up-regulated by 1.2-9.1 folds with the gene

YC.14G0015890-3C showing the highest increase in expression level (

Figure 7A). Conversely, 26 genes were down-regulated by 1.3-13.2 folds with the gene

YC.12G0009430-1A showing the most significant decrease in expression level (

Figure 7A).

Of the 109 DEGs, 11 core DEGs (ten of them up-regulated) were observed, representing a group of cultivar-independent DEGs because they were significantly regulated in both cultivars under the disease stress (

Figure 5). Furthermore, the function enrichment showed that four of them are associated with reduction of oxygen (

Table 2). Interestingly, one WRKY gene (

YC.08G0001620-1A, Type I) among those 11 core genes exhibited a significant up-regulation in CL150 (fold-change = 2.2, padj = 9.1e-03) compared to that of CL102, although it was also up-regulated in response to the disease stress (

Figure 7B).

4. Discussion

4.1. Expansion and Evolutionary Dynamics of the WRKY Family

The number of WRKY genes in C. oleifera (n=192) exceeds that of diploid species like Arabidopsis thaliana (n=72) and Oryza sativa (n=101) [

34], suggesting lineage-specific expansion, likely driven by whole-genome duplication (WGD) events common in polyploid plants [

35]. Although the WGD led to a wide distribution for WRKY genes in the tetraploid C. oleifera genome, hotspots are still present for gene localization like other polyploid species like soybean and cotton [

21,

22]. For instance, Chr10 (-A, -B, -C and -D) harbor the highest density of WRKY genes (n=25), indicating a consequence of segmental duplication. Conversely, the absence of WRKY genes on Chr09A, Chr09C, and Chr13D may reflect chromosomal rearrangements post-polyploidization. Although the number of WRKY genes carried on each chromosome varies considerably (n=3 to 25), the number of WRKY genes in each subgenome shows little variation (n=44 to 54). This phenomenon reflects dosage-balance constraints that maintain a constant functional reservoir of this key transcription factor family during polyploidization, as shown in

Liriodendron chinense [

36].

The mixed clusters of various WRKY types (e.g. Type II genes overlapping with Type I), showed in the phylogenetic tree, suggests ancient duplication events followed by subfunctionalization. Similar patterns in

Oryza sativa [

37] and

Populus trichocarpa [

38] have been linked to adaptive evolution under biotic stress. The distinct divergence of Type III genes, forming a separate clade, may reflect unique selective pressures, potentially linked to co-evolution with pathogen [

39].

4.2. Expression Dynamics on Anthracnose Resistance

The expression pattern of WRKY genes in resistant (CL150) and susceptible (CL102) cultivars underscores their roles in disease response. The genes in Cluster III and Cluster VI, up-regulated under pathogen challenge, likely participate in defense signaling, like WRKY18/40/60 in Arabidopsis, which activate jasmonate/ethylene pathways [

40]. The highly induced expression of Cluster II genes under stress suggests roles in pathogen recognition or early defense. Notably, the candidate gene

YC.08G0001620-1A (Type I), showed significant up-regulation in both resistant and susceptible cultivars. The conserved up-regulation of

YC.08G0001620-1A in

C. oleifera implies a conserved role in priming defense responses, potentially through transcriptional activation of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes.

4.3. Candidate Genes and Process to Anthracnose Resistance

The 109 cultivar-specific DEGs, particularly the 11 core DEGs, highlight core regulatory hubs in anthracnose resistance. The strong enrichment into activities like DNA-binding and oxidoreductase, implying that

YC.08G0001620-1A may be potentially as a master regulator to coordinate reductase of reactive oxygen species (ROS), a similar mechanism in rapeseed where expression of one WRKY gene

BnaWGR1 induced an accumulation of ROS both in tobacco and Arabidopsis [

41]. To validate its role, further studies are required for functional characterization via CRISPR knockout or overexpression in model systems, as demonstrated for

Vitis vinifera in powdery mildew resistance [

42].

An extensive study was conducted for identification of the WRKY transcription factor family in the tetraploid C. oleifera genome and further identified a key WRKY candidate (YC.08G0001620-1A), as a regulatory factor associated with anthracnose resistance. However, critical questions remain unresolved: (1) whether this WRKY gene confers broad-spectrum resistance against multiple pathogens or is specific to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, and (2) which downstream functional genes or regulatory modules interact with this transcription factor to orchestrate defense responses. Addressing these questions will require further investigations employing such as multi-omics approaches (e.g., CHIP-Seq and co-expression network analysis) combined with functional validation in model systems.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the WRKY gene family in C. oleifera and identifies a potential candidate gene (YC.08G0001620-1A) for anthracnose resistance. Future studies should focus on its functional characterization through genetic transformation and biochemical assays to elucidate its role in disease resistance. Additionally, further investigation of other differentially expressed genes may reveal additional mechanisms underlying anthracnose resistance in C. oleifera. This research contributes to the understanding of the molecular basis of disease resistance in C. oleifera and provides valuable information for breeding programs aimed at improving anthracnose resistance in this important oil crop.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and J.P.; methodology, J.C. and K.O.; formal analysis, D.J. and Y.X.; investigation, J.C.; resources, Y.D.; data curation, Y.D. and Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C. and K.O.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and J.P.; visualization, Y.X.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financially supported by Hubei Natural Science Foundation (2025AFB961), Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (2025BBB010) and Foundation of Hubei Academy of Forestry (2025-ZZLX-A08).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the NCBI repository (accession: PRJNA775660).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Yongqing Cao at Research Institute of Subtropical Forestry (RISF), Chinese Academy of Forestry (CAF) for providing plant materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, S. Review: WRKY transcription factors: Understanding the functional divergence. Plant Sci. 2023, 334, 111770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eulgem, T.; Rushton, P.J.; Robatzek, S.; Somssich, I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushton, P.J.; et al. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci 2010, 15, 247–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; van Nocker, S.; Tu, M.; Fang, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Overexpression of VqWRKY31 enhances powdery mildew resistance in grapevine by promoting salicylic acid signaling and specific metabolite synthesis. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. MdERF114 enhances the resistance of apple roots to Fusarium solani by regulating the transcription of MdPRX63. Plant Physiol 2023, 192, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. VqWRKY56 interacts with VqbZIPC22 in grapevine to promote proanthocyanidin biosynthesis and increase resistance to powdery mildew. New Phytol 2023, 237, 1856–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, A.; Yu, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Liang, Q.; Yang, K.; Fang, H. JrPHL8-JrWRKY4-JrSTH2L module regulates resistance to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in walnut. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Jia, H.; Chen, X.; Hao, L.; An, H.; Guo, X. The Cotton WRKY Transcription Factor GhWRKY17 Functions in Drought and Salt Stress in Transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana Through ABA Signaling and the Modulation of Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liang, D.; Bian, X.; Shen, M.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, W.; Ma, B.; Lin, Q.; Lv, J.; Chen, X.; et al. GmWRKY54 improves drought tolerance through activating genes in abscisic acid and Ca2+ signaling pathways in transgenic soybean. Plant J. 2019, 100, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q.; Hou, X.; Di, D.; Su, B.; Wang, S.; Sun, P. Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes IgWRKY50 and IgWRKY32 from Iris germanica enhance drought resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 983600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhu, W.; Xiao, D.; Liu, T.; Hou, X.; Li, Y. BcNAC056 Interacts with BcWRKY1 to Regulate Leaf Senescence in Pak Choi. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, W.; Song, Q.; Xuan, Y.; Li, K.; Cheng, L.; Qiao, H.; Wang, G.; Zhou, C. A WRKY transcription factor, TaWRKY40-D, promotes leaf senescence associated with jasmonic acid and abscisic acid pathways in wheat. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Debnath, P.; Sane, A.P.; Sane, V.A. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) WRKY23 enhances salt and osmotic stress tolerance by modulating the ethylene and auxin pathways in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 195, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Pan, J.; Hu, Y.; Yu, D. Arabidopsis VQ10 interacts with WRKY8 to modulate basal defense against Botrytis cinerea. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, C.; Qiao, H.; Song, S.; Yang, R.; Sun, L.; Ma, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. SlVQ15 interacts with jasmonate-ZIM domain proteins and SlWRKY31 to regulate defense response in tomato. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S. Comparison of Oil Content and Fatty Acid Profile of Ten NewCamellia oleiferaCultivars. J. Lipids 2016, 2016, 3982486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Xu, X.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, L.; Huang, J.; Li, D.-W. Identification and Characterization ofColletotrichumSpecies Associated with Anthracnose Disease ofCamellia oleiferain China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. The tetraploid Camellia oleifera genome provides insights into evolution, agronomic traits, and genetic architecture of oil Camellia plants. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 115032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, Z.; Wang, G.; Hu, L.; Cheng, J.; Ge, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, Q.; et al. The complex hexaploid oil-Camellia genome traces back its phylogenomic history and multi-omics analysis of Camellia oil biosynthesis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2890–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, W.; He, Z.; Lyu, H.; Wang, X.; Ye, C.; Xun, C.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Haplotype-resolved genome assembly of the tetraploid Youcha tree Camellia meiocarpa Hu. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, L.; Zhang, X.; Pang, C.; Song, M.; Wei, H.; Fan, S.; Yu, S. Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY gene family in cotton. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2014, 289, 1103–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, N.; Hu, R.; Xiang, F. Genome-wide identification of soybean WRKY transcription factors in response to salt stress. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, P.; Yao, X.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lin, P.; Wang, K. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Reveals Key Metabolites Involved in Camellia oleifera Defense against Anthracnose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.-Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Z.; Lv, D.; Ge, Y.; Shi, J.; Weijers, D.; Yu, G.; Chen, J. RIdeogram: drawing SVG graphics to visualize and map genome-wide data on the idiograms. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2020, 6, e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecher, G.; Tamura, K.; Kumar, S. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1237–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows—Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. feature Counts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah-Zawawi, M.-R.; Ahmad-Nizammuddin, N.-F.; Govender, N.; Harun, S.; Mohd-Assaad, N.; Mohamed-Hussein, Z.-A. Comparative genome-wide analysis of WRKY, MADS-box and MYB transcription factor families in Arabidopsis and rice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Yu, H.; Hu, H.; Sun, E.; Cai, M.; Dou, Z.; Dong, H.; Zuo, C. Evolutional, expressional and functional analysis of WRKY gene family reveals that PbeWRKY16 and PbeWRKY31 contribute to the Valsa canker resistance in Pyrus betulifolia. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 222, 109719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhu, S.; Xu, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Hao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yang, L.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the Liriodendron chinense WRKY gene family and its diverse roles in response to multiple abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.-S.; Han, M.; Lee, S.-K.; Cho, J.-I.; Ryoo, N.; Heu, S.; Lee, Y.-H.; Bhoo, S.H.; Wang, G.-L.; Hahn, T.-R.; et al. A comprehensive expression analysis of the WRKY gene superfamily in rice plants during defense response. Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Kong, X.; Yang, L.; Fu, M.; Zhang, S. Genome-Wide Identification of WRKY Family Genes and the Expression Profiles in Response to Nitrogen Deficiency in Poplar. Genes 2022, 13, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, G.; Xu, H.; Xiao, S.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Hu, Y. The large soybean (Glycine max) WRKY TF family expanded by segmental duplication events and subsequent divergent selection among subgroups. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lai, Z.; Shi, J.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xu, X. Roles of arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40 and WRKY60 transcription factors in plant responses to abscisic acid and abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 281–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ye, C.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.-Q.; Yang, B. An oilseed rape WRKY-type transcription factor regulates ROS accumulation and leaf senescence in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis through modulating transcription of RbohD and RbohF. Planta 2018, 247, 1323–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Cui, K.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wen, Y.-Q. Transcription factors VviWRKY10 and VviWRKY30 co-regulate powdery mildew resistance in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).