1. Introduction

Kiwifruit

(Actinidia chinensis, Ach), also called the Chinese gooseberry, is a perennial horticultural crop species, it is rich in vitamin C, minerals, dietary fiber, and other nutrients for health benefits, so it has enormous nutritional and economic value [

1]. But biotic and abiotic stresses have adversely affected its growth and yield. The bacterial canker of kiwifruit is caused by the bacterial pathogen

Pseudomonas syringae pv.

actinidiae (Psa), is a severe threat to kiwifruit production [

2]. This disease was first reported on

Actinidiae chinensis var.

deliciosa in Shizuoka, Japan in 1984, Psa can degrade lignins and phenols, which are destructive to its growth, it has been reported in the main kiwifruit-producing countries, including China, Chile, and European countries so far [3-5]. The kiwifruit cultivars are generally sensitive to Psa, such as the current master cultivars in New Zealand and China, ‘Hort 16A’ and ‘HongYang’, respectively, however, some kiwifruits, such as

Actinidia eriantha (Ace) cv. ''HuaTe', has been proven to be resistant to Psa in contrast to

Actinidia chinensis cv. ‘HongYang’. Psa can be colonized on the surface of kiwifruit, such as leaves, flowers, and stems, and enters the vine through natural stomata and wounds followed by systemic infection. The infection with Psa in kiwifruit is usually in a short time. Pathogen stress is destructive and economically damaging for kiwifruit, so it is of great significance to study the stress resistance mechanism in Kiwifruit.

As a typical post-transcriptional modification, RNA editing is mainly manifested as nucleotide insertion/deletion or conversion [

2]. Plant RNA editing occurs mainly in plastids and mitochondria, and plays a key role in post-transcriptional regulation [6-8]. In flowering plants, RNA editing usually converts 400-500 C-to-U (Cytosine-to-Uracil) in mitochondria’s transcripts and 30-40 C-to-U in plastids’ transcripts [

9]. RNA editing plays important roles in various plant developmental processes, such as organelle biogenesis, adaptation to environmental changes, and signal transduction [

10,

11]. RNA editing is an important process to maintain essential functions of encoded proteins at the RNA level, for example, pigment deficiency in tobacco cybrids is caused by the editing failure of the plastid ATP synthase alpha-subunit (atpA) mRNA [

12]. Dynamic response of plant RNA editing to environmental factors was detected in previous studies [13-15]. In several recent studies, RNA editing was proven to be responsive to pathogen stress and affect disease resistance [16-18].

Plant RNA editing is mainly mediated by RNA editing complexes, including the pentatricopeptide repeat proteins (PPRs), organelle RNA recognition motif-containing proteins (ORRMs), protoporphyrinogen IX oxidases (PPOs), and RNA editing factor interacting proteins (RIPs)/multiple organellar RNA editing factors (MORFs) [

10,

19,

20]. PPRs directly interact with mRNA to determine the specificity of RNA editing, and a PPR protein specifically recognizes one or several editing sites [

21]. PPRs are characterized by the tandem repeats of a degenerate 35 amino acid sequence. The tandem repeats often range from 2 to 27 copies in the recently recognized eukaryotic PPR gene family. Based on domain assembling structure, the PPR gene family is classified into two subfamilies, the P subfamily, and the PLS subfamily. In general, the P-type PPRs function in most aspects of organelle gene expression, while the PLS-type PPRs mainly function in RNA editing [

22]. The P-type subfamily is characterized by PPR motifs adjacent to each other without gaps. Most of the reported P-type PPRs play roles in organelle RNA stabilization and splicing, whereas P-type PPRs involved in both RNA splicing and editing have rarely been reported. However, the PLS subfamily consists of PPR motifs interspaced by two PPR-like motifs, the short PPR-like motif (PPR-like S) composed of 31 amino acids and the long PPR-like motif (PPR-like L) composed of 35-36 amino acids. Based on the motifs identified in the C terminal, PLS-type PPRs are divided into three subclasses, PPR-E, PPR-E+, and PPR-DYW, and function as critical factors in the C-to-U editing of mRNAs. The DYW domain in PPR–DYW proteins provide the cytidine deaminase activity for RNA C-to-U editing and PPR-E+ proteins recruit an atypical PPR-DYW protein to function in RNA editing [

23]. Approximately 200 PLS-type PPRs are involved in RNA editing in plastids and mitochondria in

Arabidopsis thaliana [

21].

PPRs are extensively distributed across plant lineages, containing more than 400 family members, and have been extensively identified in many different plants, with 450, 477, and 486 members of PPRs predicted in diploid Arabidopsis, rice, and foxtail genomes, respectively [

24]. PPRs function as organellar-specific RNA-binding proteins and play an essential role in multiple organelle functions and biological processes. Besides male fertility restoration, PPRs are involved in mediating many aspects of gene expression, RNA exons splicing, editing, stability, and translation of RNAs [25-27]. Defects in their functions often lead to organelle dysfunction, growth defects, embryo development defects, and biotic and abiotic stress sensitivity [23,28-32]. OsPPR11 was proven to be essential for chloroplast development and function by affecting group II intron splicing in rice [

33]. Maize PPR-E proteins mediate RNA C-to-U editing in mitochondria by recruiting the Trans deaminase PCW1 [

23]. In addition to the plant developmental process, PPRs have been reported to be involved in the responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. For instance, in Arabidopsis, several PPRs such as SOAR1, PGN, SLG1, and PPR96, have been shown to participate in responses to abiotic stresses. Engineering PPRs can be potentially applicable for synthetic and RNA biology and harnessed for the manipulation of intron splicing and/or stabilization of organellar RNA molecules, and these redesigned PPRs will be a potential means to improve plants' fitness to developmental and environmental cues.

However, the function of PPRs in kiwifruit, especially their roles in disease resistance remains unclear, and the underlying response mechanisms particularly regarding the roles of RNA editing events are not fully understood. Accordingly, we studied PPRs in the kiwifruit genome based on public transcriptome data. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the expression pattern of PPRs and RNA editing profiles under pathogens infection. We observed apparent responses of RNA editing extent and PPR gene expression to infection and identified candidate upstream transcription factors that may regulate plant immunity by modulating the PPRs gene expression. Our results provide insight into the fascinating properties and biological functions of PPRs in response to pathogens stress in kiwifruit and will help elucidate the roles of RNA editing in plant immunity.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Synteny Analysis of PPRs Members in Two Kiwifruit Species

We searched the

Ach genome with known 450

Arabidopsis PPRs as queries, 644 and 497 putative

Ach proteins were identified from HMM [

34] and BLASTP searches, respectively, and 497 overlapping PPRs that were both identified were kept as PPRs of

Ach. Similarly, 499 putative

Ace PPRs were identified. Based on their phylogenetic relationship from full-length amino acid sequences (

Figure 1), all the PPRs were classified into four clades, including P-, and PLS- types (E-type, E+-type, and DYW-type ), with 251, 91, 95, and 60 in

Ach, and 247, 74, 102, 76 in

Ace, respectively. P-type PPRs were the most and DYW-type PPRs were the least in

Ach, while P-type PPRs were the most and E class were the least in

Actinidia eriantha (

Table 1). A combination of TargetP2.0 [

35] and Predotar4.0 [

36] was used to predict the subcellular localization of PPRs. The results showed that 40.64% were localized in mitochondria or chloroplasts in

Ach, with 28.37% of the PPRs located in mitochondria, and 12.27% in chloroplasts. For

Ace, 43.88% were located in

Ace mitochondria or chloroplasts, with 32.06% of the PPRs located in mitochondria, and 11.82% were located in chloroplasts. The number of amino acids in

Ach ranged from 91 to 1871. The number of amino acids in

Ace ranged from 111 to 1738 (

Table S1 and S2). Chromosomal localization results revealed that kiwifruit PPRs were widely distributed on all of the chromosomes (

Figure S1).

Synteny analysis within the kiwifruit genome using MCScanX software was further conducted to determine their duplication events and possible collinear blocks between genomes, as shown in

Figure 1. The collinearity analysis of the PPR protein of

Ach and

Arabidopsis thaliana showed that 166

Ach PPRs showed syntenic relationships with 156 PPRs of

Arabidopsis thaliana, while 136

Ace PPRs showed syntenic relationships with 134 PPRs in

Arabidopsis thaliana, involving all the four types of PPRs, indicating the evolution conservation of PPRs. Synteny analysis within the genomes showed that kiwifruit PPRs shared a high homologous conservation. The origins of duplicated genes in the kiwifruit genome were further classified into five classes, including whole genome/segmental (match genes in syntenic blocks), tandem (continuous repeat), proximal (in the nearby chromosomal region but not adjacent) or dispersed (other modes than segmental, tandem and proximal) duplications. The results showed that the origins of duplicated PPRs in

Ach were classified into 11 singletons, 24 dispersed, 8 proximal, 9 tandem, and 445 segmental (

Table S1). PPRs in

Ace shared the same distribution, which indicated that the expansion of kiwifruit PPRs mainly resulted from segmental duplication that was accompanied by whole genome duplication.

The Ka/Ks values were calculated for the paralogous PPRs to explore the selection pressure during the evolution, about 60 pairs of paralogous PPRs were obtained from MCScanX [

37] for each kiwifruit species, and all the Ka/Ks values of these gene paralogs were less than one, suggesting that these genes evolved under purifying selection. In addition, we obtained the orthologous PPRs between

Ach and

Ace, a total of 306 pairs were obtained from MCScanX, and only two pairs exhibited Ka/Ks with more than one, including pairs

Actinidia00869-

DTZ79_13g12210, and

Actinidia08538-

DTZ79_28g04010, the former belongs to P-type, and the latter belongs to E+ type PPRs. This observation indicated that PPRs evolved slowly after the speciation of

Ach and

Ace.

Figure 1.

The phylogenetic relationships and self-collinearity of PPRs in Actinidia chinensis (Ach) and Actinidia eriantha (Ace). A total of 497 and 499 PPRs in

Ach and

Ace were used for phylogenetic tree construction by the maximum likelihood (ML) method [

38], respectively. All the PPRs were classified into four groups; different groups are shaded by different colors, green, blue, purple, and yellow areas indicating P-, E-, E+-, and DYW- types of PPRs, respectively. (a) The phylogenetic relationships of PPRs in

Ach. (b) The phylogenetic relationships of PPRs in

Ace. (c) Interchromosomal relationships of PPRs in

Ach. (d) Interchromosomal relationships of PPRs in

Ace. The red lines highlight the syntenic PPRs pairs.

Figure 1.

The phylogenetic relationships and self-collinearity of PPRs in Actinidia chinensis (Ach) and Actinidia eriantha (Ace). A total of 497 and 499 PPRs in

Ach and

Ace were used for phylogenetic tree construction by the maximum likelihood (ML) method [

38], respectively. All the PPRs were classified into four groups; different groups are shaded by different colors, green, blue, purple, and yellow areas indicating P-, E-, E+-, and DYW- types of PPRs, respectively. (a) The phylogenetic relationships of PPRs in

Ach. (b) The phylogenetic relationships of PPRs in

Ace. (c) Interchromosomal relationships of PPRs in

Ach. (d) Interchromosomal relationships of PPRs in

Ace. The red lines highlight the syntenic PPRs pairs.

2.2. PPRs Play Roles in Fruit Development and Ripening

Based on RNA-seq data [

39] during the fruit development and maturation of

Ach, we examined the gene expression profiles of PPRs in kiwifruit during different periods. After preliminary screening, a total of 260 PPRs showed expression during fruit development and maturation for

Ach. Most PPRs were highly expressed in the development stage and lowly expressed after harvest, and a small part of PPRs were highly expressed in the maturity stage. 16 PPRs exhibited differentially expression at different time points (

Figure 2). In terms of subfamily classification of PPRs, the expression of PLS-type PPRs was higher in the development stage, while the expression of P-type PPRs was highly expressed in the maturity stage. Module-feature clustering was conducted based on the expression of PPRs during fruit development and maturation of kiwifruit, based on weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) results, PPRs were divided into four modules (turquoise, blue, brown, and grey), consisting of 188, 7, 5, and 60 PPRs, respectively (

Table S3). The results showed that the turquoise module gene expression was mostly associated with traits such as glucose, quinic acid, and linalool, gene expression of PPRs in this module negatively correlated with the contents of sugars (such as glucose) and esters (such as ethyl butyrate), and positively correlated with the contents of alcohols (such as linalool) and acids (such as quinic acid) (

Figure 2). In other words, during the fruit development and maturation stage, PPRs in the turquoise module negatively regulated the synthesis of the content of glucose, other sugars and ethyl butyrate, and other esters, but positively regulated the synthesis of quinic acid, linalool, etc. In terms of the relationships between different modules, the turquoise module was positively correlated with the brown module gene, and negatively correlated with the blue module gene, while the gray module was not associated with any other modules.

Furthermore, we used the turquoise module to screen hub PPRs that own a high degree in the module, which can better represent the overall expression level of this module gene and be more correlated with characteristics (

Figure 2). The PPRs with module member closeness greater than 0.8 were selected as the hub genes. After screening, there were 72, 4, 7, and 11 hub genes related to glucose, quinic acid, linalool, and ethyl butanoate, respectively. Some hub PPRs are hub genes associated with multiple biomarkers' characteristic metabolites. For example,

Actinidia20495.t1 was a hub gene in regulating the synthesis of glucose, linalool, and ethyl butanoate.

Actinidia15159.t1 was a hub gene in regulating the synthesis of glucose, quinic acid, and linalool.

Actinidia14816.t1 and the other three genes were hub genes in regulating the synthesis of glucose and linalool.

Actinidia07826.t1 and the other eight genes were hub genes of glucose and ethyl butanoate.

Actinidia19198.t1 is a hub gene in regulating the synthesis of quinic acid and linalool.

Actinidia05956.t1 is a hub gene in regulating the synthesis of glucose and quinic acid. The PPRs which regulated glucose synthesis were closely related to themselves. Module membership-gene characteristics associated with glucose, quinic acid, linalool, and ethyl butyrate in kiwifruit were shown in

Figure S2. In conclusion, we hypothesized that

Actinidia20495.t1 and

Actinidia15159.t1 were involved in the fruit development and maturation of kiwifruit, they may play roles in the synthesis of sugar and acid compounds, as well as other changes of content of alcohols, such as linalool and esters, ethyl butyrate in kiwifruit during development and ripening.

2.3. Different PPRs Expression and RNA Editing Patterns in Response to Psa Infection in Two Kiwifruit Species

Based on RNA-seq data [

40] in resistant (‘HuaTe’,

Ace) and susceptible (‘HongYang’,

Ach) kiwifruits during early infection of

Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae (Psa), we examined the expression of PPRs between two different kiwifruit species (

Figure 3). After Psa infection, tens of PPRs were differentially expressed in both ‘HongYang’ and ‘HuaTe’. A total of 45 differentially expressed PPRs were identified in two kiwifruits, there were 8 differentially expressed PPRs shared in both kiwifruits, 26 specific to ‘HuaTe’ and 10 specific to ‘HongYang’. The shared 8 differentially expressed PPRs were

Actinidia05776,

Actinidia08478,

Actinidia18849,

Actinidia19198,

Actinidia24301,

Actinidia25020,

Actinidia28434,

Actinidia29423, which were labeled in

Table S4. 18 out of 45 differentially expressed PPRs were identified in ‘HongYang’, there were 4, 10, 13 and 10 differentially expressed PPRs at 12 hours after infection (hai), 24 hai, 48 hai and 96 hai, respectively. While there were more differentially expressed PPRs, with 34 in ‘HuaTe’ (

Table S4), 10, 14, 21, and 20 differentially expressed genes were detected at 12 hai, 24 hai, 48 hai, and 96 hai respectively, furthermore, the fold changes of differentially expressed PPRs in ‘HuaTe’ were larger than that of ‘HongYang’. For both kiwifruits, the number of differentially expressed PPRs was the most at 48 hai after infection, indicating the critical immune response occurred at this time point. In terms of the up-down-regulation trend of genes, more differentially down-regulated PPRs were found in both kiwifruits than differentially up-regulated PPRs especially in ‘HuaTe’. For ‘HuaTe’, the number of differentially down-regulated PPRs were 5, 10, 14, and 12 at 12 hai, 24 hai, 48 hai, and 96 hai, respectively, while the up-regulated PPRs in ‘HuaTe’ were 5, 4, 7, 8 at 12 hai, 24 hai, 48 hai and 96 hai, respectively. For ‘HongYang’, the number of differentially down-regulated PPRs were 4, 6, 9, 6 at 12 hai, 24 hai, 48 hai, and 96 hai, respectively, while the up-regulated PPRs in ‘HuaTe’ were 0, 4, 4, 4 at 12 hai, 24 hai, 48 hai and 96 hai, respectively. These observations indicated the down-regulation expression is the overall tendency in response to Psa infection. We took five of the differentially expressed PPRs as illustrations, they were all down-regulated in ‘HuaTe’ after Psa infection but expressed stably in ‘HongYang’ (

Figure 3b). For example,

Actinidia18966.t1 and

Actinidia05278.t1 were differentially expressed at 24 hai, 48 hai, and 96 hai only in ‘HuaTe’. Thus, in comparison with ‘HongYang’, ‘HuaTe’ demonstrated more differentially expressed PPRs, especially down-regulated tendencies. Therefore, we speculated that the down-regulation of PPRs may be related to the resistance of ‘HuaTe’ to Psa.

Given the different expression patterns of PPRs between two kiwifruits in response to Psa infection, we further examined their corresponding RNA editing events in the chloroplast (

Table S5), as shown in

Figure 3c. A total of 61 RNA editing sites occurred in 29 genes were detected in this study. We observed that a wide reduction or loss of editing efficiency was detected in samples after Psa infection, especially in ‘HuaTe’. We selected six RNA editing sites with obviously reduced editing efficiency to illustrate this point, such as ndhB-277, rps2-83,matK-152, ndhD-293, petL-2, and rpoB-184, editing in site ndhD-293, petL-2 was reduced at 12 hai, whereas editing in sites of ndhB-277, rps2-83 was completely lost at 12 hai, however, in ‘HongYang’, these notable reductions of editing were not detected. In addition, the differentially expressed PPRs were mostly located in chloroplast, which might thereby affect these chloroplast RNA editing. Taken together, the above results showed that PPRs were responsive to Psa infection, and exhibited significantly different expression levels between resistant and susceptible kiwifruit, suggesting the roles of PPRs in plant immunity. Compared with ‘HongYang’, resistant kiwifruit ‘HuaTe’ demonstrated a more dramatic response to Psa infection in not only RNA editing level but also gene expression of PPRs. Under pathogen attack, similar to

MORF genes, PPRs were also prone to be down-regulated, thereby reducing the RNA editing level to trigger a series of defense responses.

2.4. Upstream Transcription Factors Associated with PPRs in Kiwifruit

To investigate the underlying pathway that may regulate the PPRs expression in kiwifruit, we selected the differentially expressed PPRs at 48 hai and obtained their upstream transcription factors (TFs) from the PlantRegMap database, and only kept ones that demonstrated differential expression at 48 hai. Finally, the regulatory network of PPRs and upstream TFs was constructed, consisting of 9 differentially expressed PPRs and 12 upstream transcription factors in ‘HongYang’, 10 differentially expressed PPRs and 17 upstream transcription factors in ‘HuaTe’, respectively, as shown in

Figure 4. These upstream TFs were up or down-regulated at 48 hai, and positively or negatively regulated the gene expression of PPRs in ‘HongYang’ and ‘HuaTe’. There were two shared upstream TFs (

Actinidia00657,

Actinidia36651) that regulated the expression of differentially expressed PPRs (

Actinidia25020,

Actinidia28434) in both ‘HongYang’ and ‘HuaTe’, indicating their common regulatory function. One TF gene

Actinidia00657, encoding dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2C (DREB2A), was down-regulated in both ‘HongYang’ and ‘HuaTe’, and negatively regulated the expression of the PPR gene

Actinidia25020 at 48 hai, another upstream TF gene

Actinidia36651, encoding DELLA protein (GAI1) that acts as a repressor of the gibberellin (GA) signaling pathway, was up-regulated in both ‘HongYang’ and ‘HuaTe’ and positively regulated the expression of PPR gene

Actinidia28434. Those differentially expressed transcription factors may participate in the upstream regulation of PPR gene expression and RNA editing in response to pathogen stress.

3. Discussion

Kiwifruit is a perennial horticultural crop species with high nutritional and economic value. However, various diseases bring a serious threat to kiwifruit. RNA C-to-U editing is widespread in vascular plants and plays an essential role in organellar gene expression and plant growth and development. PPRs are extensively distributed across plant lineages, containing more than 400 family members, and function as organellar-specific RNA-binding proteins [

41], they are also important subunits of RNA editsome and play a crucial role in RNA editing regulation. Some PPRs in

Arabidopsis thaliana, such as SOAR1 [

42] and PPR96 [

43], are involved in response to stress. However, the function of PPRs and their response to stress in kiwifruit have been rarely reported. In this study, we studied the structure, classification, and expression of the PPRs family in two representative kiwifruit species (

Ach, and

Ace) with different disease resistance. A total of 497 and 499 PPRs were identified in '‘HongYang’' and '‘HuaTe’' respectively. The results showed that the expansion of kiwifruit PPRs mainly resulted from segmental duplication. The comparable family numbers in two kiwifruits indicated the expansion of the PPR gene family occurred before the species differentiation. The vast majority of kiwifruit PPRs are predicted to be localized to mitochondria or chloroplasts, which is consistent with the studies of PPRs in other plants.

Based on RNA-Seq data during the fruit development and maturation of kiwifruit, we found that the PPRs were differentially expressed at different time points, indicating the roles of PPRs in fruit development. In addition, further transcriptome analysis was conducted based on RNA-seq data in resistant (‘HuaTe’, Ace) and susceptible (‘HongYang’, Ach) kiwifruits during early infection of Psa, we examined the expression of PPRs between two different kiwifruits. For both kiwifruits, the number of differentially expressed PPRs was the most at 48 hai after infection, indicating the critical immune response occurred at this time point. The results showed that PPRs genes were also responsive to Psa infection, indicating their roles in plant immunity. Further comparison of differentially expressed genes of PPRs revealed that more differentially down-regulated PPRs were found than differentially up-regulated PPRs in both kiwifruits, especially in ‘HuaTe’. In addition, more differentially expressed PPRs were found in ‘HuaTe’ than in 'HongYang’, the fold change of differentially expressed PPRs in ‘HuaTe’ was also larger than that of ‘HongYang’. We further examined their corresponding RNA editing events in chloroplast and found that a wide reduction or loss of editing efficiency was detected in samples after Psa infection, especially in ‘HuaTe’. From the results, we hypothesized that PPRs may play roles in regulating RNA editing and disease resistance response in kiwifruit. Several transcription factors that regulate the expression of kiwifruit PPRs were also identified in our study, such as DREB2A, and GAI1. Those differentially expressed transcription factors may participate in the upstream regulation of PPR gene expression and RNA editing in response to both development and stresses.

In our previous studies [

17], we observed that

MORF genes in ‘HuaTe’ and ‘HongYang’ were differentially expressed after pathogen infection,

MORF2.1,

MORF9.1, and

MORF7 in ‘HuaTe’ were significantly down-regulated, which is similar to the expression of PPRs analyzed in this study. We further identified upstream TFs of

PPR (

Figure 3b) and

MORF genes (

MORF2.1,

MORF9.1, and

MORF7) in kiwifruit (

Figure S3), the regulatory network consists of 49 edges and 24 nodes, among which 9 TFs were differentially expressed, and 6 out of them were significantly up-regulated. Transcription factor

Actinidia17974.t1 co-regulated

PPR and

MORF genes,

Actinidia17974.t1 encodes

Transcription factor IIIA, which regulates 5S rRNA levels during development. Other TFs belong to the C2H2 zinc finger gene family or BCR-BPC gene family, and function in transcription factor activity, sequence-specific DNA binding activity, 5SrRNA binding activity, developmental process, and metal ion binding function. Interestingly, most of the differentially expressed TFs only occurred in ‘HuaTe’, such as

Actinidia10847.t1,

Actinidia26001.t1,

Actinidia17974.t1, and

Actinidia39948.t1, these four transcription factors only respond to pathogen infection in ‘HuaTe’ while do not in ‘HongYang’. We speculated that these transcription factors may play roles in pathogen resistance. Both

PPR and

MORF genes tended to be down-regulated in response to Psa infection and resulted in the loss and reduction of RNA editing especially in ‘HuaTe’ with higher resistance to Psa. Taken together, the expression response of

PPR and

MORF genes to pathogen and the difference between resistant and susceptible kiwifruit suggested the roles of RNA factors in plant immunity. Compared with ‘HongYang’, resistant kiwifruit demonstrated a more dramatic response to Psa infection in not only RNA editing level but also gene expression. Therefore, we speculated that

PPRs and

MORF genes play a role together in the process of pathogen infection. Under pathogen attack, similar to

MORF genes, PPRs were also prone to be down-regulated, thereby reducing the RNA editing level to trigger a series of defense responses. Our results provide insight into the molecular evolution of PPR and their roles in pathogens stress in kiwifruit.

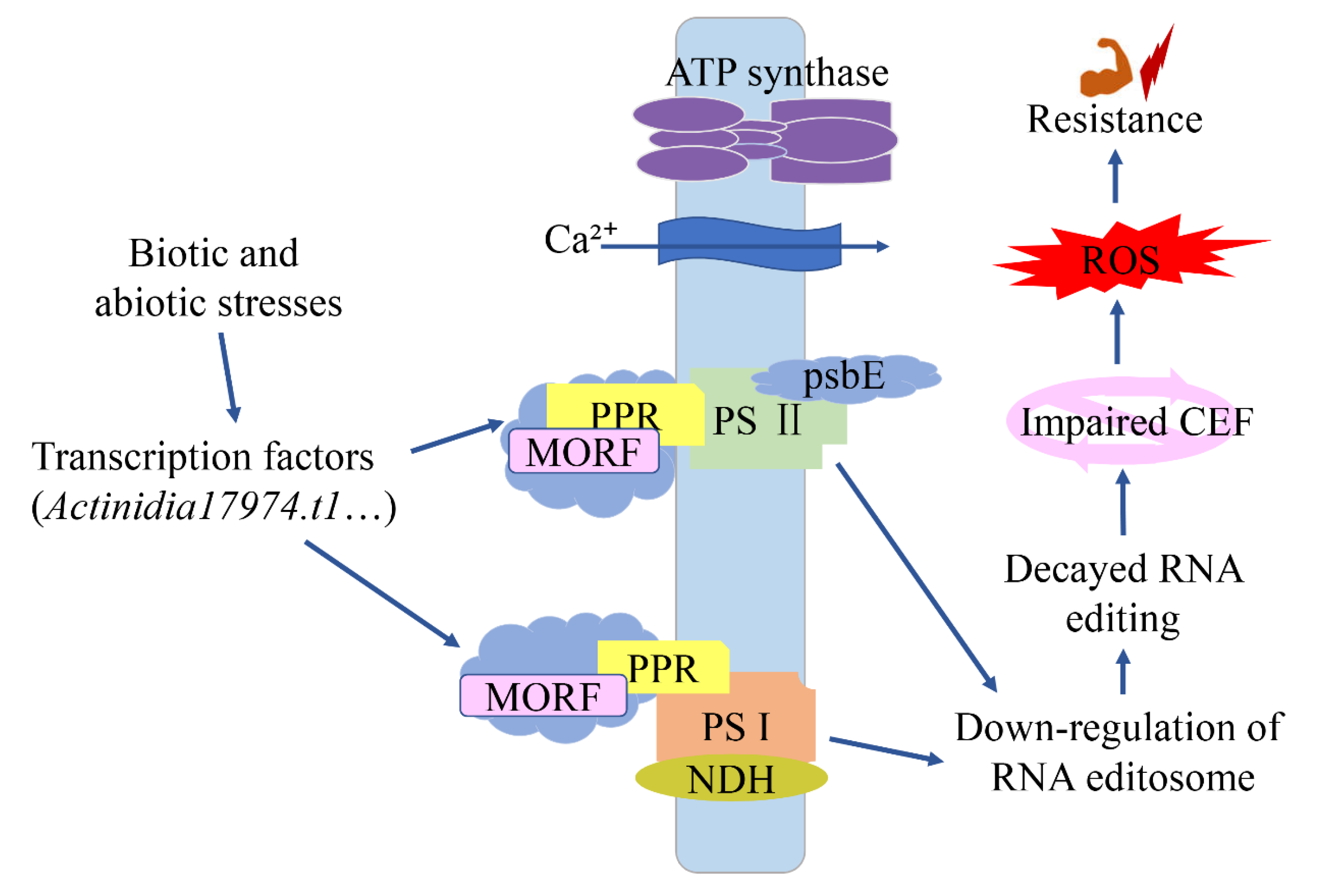

Mitochondria and chloroplasts, as intracellular energy conversion sites, play a key role in plant-pathogen interactions. They are also important sources of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Reactive oxygen species act as a key defense molecule in plant immune response [

44]. However, how mitochondrial and chloroplast proteins regulate the plant immune system remains unclear. Increasing molecular evidence suggested that many PPRs were involved in responses to a variety of biological and abiotic stresses. In

Arabidopsis thaliana, PPR40 is known to provide signaling connections between mitochondrial electron transport elements, and knockout of the

PPR40 gene leads to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), increased lipid peroxidation, and superoxide dismutase activities [

45]. In our study, the comparison of resistant and susceptible kiwifruit also confirmed this hypothesis. After pathogen infection, down-regulated expression of

PPRs and

MORF genes (

MORF9.1, MORF7, and

MORF2.1) and decreased RNA editing were detected in resistant kiwifruit. The affected genes (such as

ndhB,

ndhD, and

cemA) are mainly in the photosynthetic system and play a role in DNA-RNA transcription and RNA splicing.

ndhB encodes the B subunit of the chloroplast NADH dehydrogenase-like complex (NDH), which is involved in the cyclic electron flow (CEF) of photosystem I. Therefore, we speculated that the reduced editing efficiency of these genes may trigger impaired CEF, leading to the activation of reactive oxygen-mediated retrograde signaling and significantly enhanced disease resistance to pathogens (

Figure 5).

PPR and

MORF genes may regulate plant-pathogen interactions by controlling the degree of RNA editing, particularly the composition of the NDH complex.

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Genome-Wide Identification of PPRs in Ach and Ace

The genome and annotation files of

Ach and

Ace were downloaded from NCBI (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), with version ‘ASM966300v1’ and ‘White_v1.0’, respectively. Using the previously identified 30 PPRs in

Arabidopsis as a reference [

46], including PP438_ARATH, PP264_ARATH, etc. of the P-type and PP320_ARATH and PP207_ARATH, etc. of the PLS-type. We used two search strategies to obtain kiwifruit PPRs. First, we implemented BLASTP searches of the complete genome with an E-value cut-off of 0.00001 to reduce false positives. Second, Hidden Markove Model (HMM) profiles of PPRs in

Arabidopsis were constructed and used to search against the two kiwifruit protein databases by using HMMER software with an E-value cut-off of 0.001 [

34]. Subsequently, we verified all sequences by checking the existence of PFAM (

http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) domains PF01535, sequences containing less than 2 P motifs were excluded.

4.2. Subcellular Localization and Physical Localization

TargetP [

47] and Predotar [

36] were used to predict the putative subcellular localization of kiwifruit PPRs. In addition, the physical localization information of the PPRs on the corresponding chromosome was obtained according to the annotation documents, and a sketch map of the gene's physical location was drawn by using TBtools [

48].

4.3. Synteny Analysis and Detection of Tandemly/segmentally Duplicated PPRs

We performed self-blast by comparing protein-coding genes against their genome using BLASTP with an E-value cut-off of 0.00001, all BLASTP hits were used as inputs for the software MCScanX [

37] (Multiple Collinearity Scan toolkit) to identify possible collinear blocks within genomes of

Ach and

Ace. Based on the self-blast results, the tandemly/segmentally duplicated PPRs for each species were detected. The command of ‘Duplicate_gene_classifier’ was used to classify origins of the duplicate genes of ONE genome into whole genome/segmental (match genes in syntenic blocks), tandem (continuous repeat), proximal (in the nearby chromosomal region but not adjacent) or dispersed (other modes than segmental, tandem and proximal) duplications. All intra/inter-genomic synteny relationships were visualized with Tbtools [

48].

4.4. Expression Analysis of PPR Genes in Ach and Ace

To examine the expression profiles of kiwifruit PPRs, we performed transcriptome analysis based on two sets of RNAseq data. For

Ach, RNA-seq data of fruit samples were retrieved from the NGDC database (

https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/) under the accession number PRJCA003268 [

39]. Six developmental periods (40, 60, 80, 100, 120, and 140 days after pollination) and six maturity periods (4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 days after harvest of ripe fruit) were selected for ‘HongYang’, each time point consists of three replicates. For

Ach and

Ace, RNA-seq data of leaves in response to

Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae (Psa) during early infection was also retrieved with accession number PRJNA514180 [

40]. Transcriptome analysis was implemented by the protocol in a previous study [

17]. Gene expression levels were measured by FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). EdgeR was used to determine the differentially expressed genes. Heatmaps with all samples were plotted using the 'pheatmap’ function in R.

4.5. Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

Based on RNA-seq data of fruit samples from

Ach, WGCNA [

49] was used to find the co-expression modules and key PPRs related to fruit development and maturation, the soft threshold β was set 16. First, the adjacency matrix of PPR expression was transformed into a topological overlap matrix (TOM). The characteristic genes were calculated and hierarchical clustering (mergeCutHeight value is 0.25) was used to identify the key modules. Module signature genes (ME) and module members (MM) were used to distinguish important modules associated with fruit development and maturation. ME shows the first main component in a module and describes the module's representation pattern. MM represents the relationship between genes and module-characteristic genes and refers to the reliability of genes as part of the module.

4.6. Identification of RNA Editing Sites

First, the RNAseq data were mapped against the chloroplast genome reference using the HISAT2 software with default parameters [

50]. The 'bcftools' tool was used to identify variants/SNPs and generate VCF files [

51]. Thus RNA editing sites were filtered out based on the results of the variant. Based on the SNP-calling results (in “VCF” format) and genome annotation files (in “tbl” format), RNA editing sites were identified by using REDO tool [

52]. As a comprehensive application tool, REDO can accurately identify plant RNA editing sites based on variant results from RNA-seq data. A series of comprehensive rule-dependent and statistical filters were implemented in the REDO tool to reduce the false positives. We manually examined all mismatches to further minimize false positive sites. For each site, RNA editing efficiency was quantified by the proportion of edited transcripts in total covered transcripts.

4.7. Identification of Upstream Regulatory Transcription Factors

PlantRegMap database was used to retrieve the transcriptional regulatory map of kiwifruit [

53]. The transcriptional regulations in PlantRegMap were identified from the literature and ChIP-seq data, or inferred by combining transcript factors (TF) binding motifs and regulatory elements data, this tool was used to infer potential regulatory interactions between TF and target genes, found the TFs which possess overrepresented targets in the input gene set. Finally, the regulatory transcription factors were annotated based on blast results against reference proteins in Uniprot, the regulatory interactions were further drawn using Cytoscape [

54].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study analyzed the chromosomal positions, phylogenetic relationships, and evolution of PPRs in Ach and Ace, and provided their expression patterns at different stages of fruit development and under pathogen stress. The results showed that PPRs were differentially expressed at different stages of fruit development and maturation, indicating the role of PPRs in the fruit development and maturation of kiwifruit. The difference in expression and RNA editing profiles of PPRs between resistant and susceptible kiwifruit were also observed after pathogen infection, indicating the roles of the PPRs in stress response. Similar to MORF genes, the PPRs were also associated with resistance and affected RNA editing sites that occurred in chloroplasts. It is suggested that RNA editing involving PPR and MORF genes may be related to chloroplast-mediated immunity. The results of this study will provide a reference for further elucidation of the molecular mechanism of plant immunity and resistance breeding of kiwifruit.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 (XLSX): Table S1. Detailed information for PPRs in the Ach genome. Additional file 1: Table S2. Detailed information for PPRs in the Ace genome. Table S3: Detailed information of PPRs modules during the fruit development and maturation of Ach. Table S4: Differentially expressed PPRs in response to Psa infection. Table S5: Detailed information of identified RNA editing sites in the plasmid of kiwifruit. Additional file 2 (DOCX): Figure S1. Chromosomal locations of PPR genes in kiwifruit. Figure S2. Module membership-gene characteristics associated with glucose, quinic acid, linalool, and ethyl butyrate in kiwifruit. Figure S3. Expression and interaction network of upstream transcription factors that regulated kiwifruit PPR genes and the MORF genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and A.Z.; methodology, Y.X.; software, Y.X.; validation, A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X., and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.X., F.L. and A.Z.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, A.Z.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32070682, the National Science & Technology Innovation Zone Project, grant numbers 1716315XJ00200303 and 1816315XJ00100216, and CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the Bioinformatics Group of Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China for the discussion and suggestion to improve the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

PPRs: Pentatrico peptide repeat proteins; MORF: Multiple organelle RNA editing factors; Psa: Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae; C-to-U: cytidines substituting uridines; RNA-seq: RNA sequencing; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; WGS: whole-genome re-sequencing; cox1: cytochrome oxidase subunit 1; nad: NADH dehydrogenase; rps: ribosomal protein gene; rps14: 30S ribosomal gene; ccmB: cytochrome c maturation gene; hai: hour after inoculation; HMM: Hidden Markove Model; CEF: cyclic electron flow; PS Ⅰ: photosystem Ⅰ complex; PS Ⅱ: photosystem Ⅱ complex; Ach: Actinidia chinensis, Ace: Actinidia eriantha. TFs: transcript factors.

References

- Park, Y.S.; Im, M.H.; Ham, K.S.; Kang, S.G.; Park, Y.K.; Namiesnik, J.; Leontowicz, H.; Leontowicz, M.; Katrich, E.; Gorinstein, S. Nutritional and pharmaceutical properties of bioactive compounds in organic and conventional growing kiwifruit. Plant foods for human nutrition 2013, 68, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petriccione, M.; Di Cecco, I.; Arena, S.; Scaloni, A.; Scortichini, M. Proteomic changes in Actinidia chinensis shoot during systemic infection with a pandemic Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae strain. J Proteomics 2013, 78, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Xia, H.; Zhong, C.; Li, L.; Zeng, C. Genomic characterization of two nickie-like bacteriophages that infect the kiwifruit canker phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Arch Virol 2022, 167, 1713–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Dai, D.; Lv, L.; Ahmed, T.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; An, Q.; Sun, G.; Li, B. Advancements in the Use of Bacteriophages to Combat the Kiwifruit Canker Phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorillo, A.; Frezza, D.; Di Lallo, G.; Visconti, S. A Phage Therapy Model for the Prevention of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae Infection of Kiwifruit Plants. Plant Dis 2023, 107, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Bentolila, S.; Hanson, M.R. The Unexpected Diversity of Plant Organelle RNA Editosomes. Trends in plant science 2016, 21, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentolila, S.; Oh, J.; Hanson, M.R.; Bukowski, R. Comprehensive high-resolution analysis of the role of an Arabidopsis gene family in RNA editing. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkott, B.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tsuji-Tsukinoki, S.; Knie, N.; Knoop, V. Chloroplast RNA editing going extreme: more than 3400 events of C-to-U editing in the chloroplast transcriptome of the lycophyte Selaginella uncinata. RNA 2014, 20, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giege, P.; Brennicke, A. RNA editing in Arabidopsis mitochondria effects 441 C to U changes in ORFs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 15324–15329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Meng, S.; Su, W.; Bao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yin, W.; Liu, C.; Xia, X. Genome-Wide Analysis of Multiple Organellar RNA Editing Factor Family in Poplar Reveals Evolution and Roles in Drought Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chateigner-Boutin, A.L.; Small, I. Plant RNA editing. RNA biology 2010, 7, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz-Linneweber, C.; Kushnir, S.; Babiychuk, E.; Poltnigg, P.; Herrmann, R.G.; Maier, R.M. Pigment deficiency in nightshade/tobacco cybrids is caused by the failure to edit the plastid ATPase alpha-subunit mRNA. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1815–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, Y.; Mulligan, R.M. Heat stress results in incomplete C-to-U editing of maize chloroplast mRNAs and correlates with changes in chloroplast transcription rate. 2001, 40, 209–213. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Tao, T.; Luo, Z.; Yan, S.G.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.Q.; Liu, G.L.; Xia, H.; Luo, L.J. RNA Editing Responses to Oxidative Stress between a Wild Abortive Type Male-Sterile Line and Its Maintainer Line. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X. Dynamic response of RNA editing to temperature in grape by RNA deep sequencing. Funct Integr Genomics 2020, 20, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Xiong, Y.; Fang, J.; Liu, K.; Peng, H.; Zhang, X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of peach multiple organellar RNA editing factors reveals the roles of RNA editing in plant immunity. BMC Plant Biol 2022, 22, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Fang, J.; Jiang, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, K.; Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, A. Genome-Wide Analysis of Multiple Organellar RNA Editing Factor (MORF) Family in Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) Reveals Its Roles in Chloroplast RNA Editing and Pathogens Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Andrade, J.; Ramirez, V.; Lopez, A.; Vera, P. Mediated plastid RNA editing in plant immunity. Plos Pathog 2013, 9, e1003713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, M.; Zehrmann, A.; Verbitskiy, D.; Kugelmann, M.; Hartel, B.; Brennicke, A. Multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) family proteins are required for RNA editing in mitochondria and plastids of plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 5104–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Tang, W.; Hedtke, B.; Zhong, L.; Liu, L.; Peng, L.; Lu, C.; Grimm, B.; Lin, R. Tetrapyrrole biosynthetic enzyme protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase 1 is required for plastid RNA editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 2023–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, A.; Small, I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2014, 65, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Kang, H. Engineering of pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in organellar gene regulation. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1144298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Huang, Z.Q.; Ma, B.; Yang, Y.Z.; Xiu, Z.H.; Wang, L.; Tan, B.C. Maize PPR-E proteins mediate RNA C-to-U editing in mitochondria by recruiting the trans deaminase PCW1. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutmann, B.; Royan, S.; Schallenberg-Rudinger, M.; Lenz, H.; Castleden, I.R.; McDowell, R.; Vacher, M.A.; Tonti-Filippini, J.; Bond, C.S.; Knoop, V.; et al. The Expansion and Diversification of Pentatricopeptide Repeat RNA-Editing Factors in Plants. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, T.; Zhao, P.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Mai, T.; Zou, Y.; et al. Research Progress of PPR Proteins in RNA Editing, Stress Response, Plant Growth and Development. Front Genet 2021, 12, 765580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Xiu, Z.H.; Meeley, R.; Tan, B.C. Empty Pericarp5 Encodes a Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein That Is Required for Mitochondrial RNA Editing and Seed Development in Maize. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, E.; Tasaka, M.; Shikanai, T. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for RNA editing in chloroplasts. Nature 2005, 433, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C.; Mizrahi, R.; Edris, R.; Tang, H.; Zer, H.; Colas des Francs-Small, C.; Finkel, O.M.; Zhu, H.; Small, I.D.; Ostersetzer-Biran, O. MSP1 encodes an essential RNA-binding pentatricopeptide repeat factor required for nad1 maturation and complex I biogenesis in Arabidopsis mitochondria. New Phytol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Dong, J.; Lu, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, D.; Yu, H.; Ye, S.; Bu, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; et al. A cytosolic pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for tapetal plastid development by regulating OsGLK1 transcript levels in rice. New Phytol 2022, 234, 1678–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Z.; Liu, X.Y.; Tang, J.J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Tan, B.C. GRP23 plays a core role in E-type editosomes via interacting with MORFs and atypical PPR-DYWs in Arabidopsis mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2210978119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Li, C.; Guan, J.; Liang, W.H.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yao, S.; He, L.; Wei, X.D.; et al. The PPR-Domain Protein SOAR1 Regulates Salt Tolerance in Rice. Rice 2022, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.A.; Molloy, D.P.; Luo, Z.F.; Su, Y.; Li, H.O.; Liu, Q.; Wang, R.Z.; Xiao, L.T. The PPR protein RARE1-mediated editing of chloroplast accD transcripts is required for fatty acid biosynthesis and heat tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Commun 2022, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Li, Z.; Shen, L.; Li, Q.; Zhu, L.; Ren, D.; Hu, J.; et al. OsPPR11 encoding P-type PPR protein that affects group II intron splicing and chloroplast development. Plant Cell Rep 2023, 42, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W200–W204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boos, F.; Mühlhaus, T.; Herrmann, J.M. Detection of Internal Matrix Targeting Signal-like Sequences (iMTS-Ls) in Mitochondrial Precursor Proteins Using the TargetP Prediction Tool. Bio-protocol 2018, 8, e2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, I.; Peeters, N.; Legeai, F.; Lurin, C. Predotar: A tool for rapidly screening proteomes for N-terminal targeting sequences. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Molecular biology and evolution 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shu, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, K.; Xie, Y.; Li, M.; Ma, T.; et al. Integrative analyses of metabolome and genome-wide transcriptome reveal the regulatory network governing flavor formation in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). New Phytol 2022, 233, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Sun, L.; Lin, M.; Chen, J.; Qi, X.; Hu, C.; Fang, J. Comparative transcriptome analysis of resistant and susceptible kiwifruits in response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. Actinidiae during early infection. Plos One 2019, 14, e0211913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.L.; Giang, K.; Mulligan, R.M. Molecular evolution of pentatricopeptide repeat genes reveals truncation in species lacking an editing target and structural domains under distinct selective pressures. BMC evolutionary biology 2012, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Bi, C.; Mei, C.; Jiang, S.C.; Wang, X.F.; Lu, Z.J.; Zhang, D.P. Arabidopsis exoribonuclease USB1 interacts with the PPR-domain protein SOAR1 to negatively regulate abscisic acid signaling. Journal of experimental botany 2020, 71, 5837–5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.M.; Zhao, J.Y.; Lu, P.P.; Chen, M.; Guo, C.H.; Xu, Z.S.; Ma, Y.Z. The E-Subgroup Pentatricopeptide Repeat Protein Family in Arabidopsis thaliana and Confirmation of the Responsiveness PPR96 to Abiotic Stresses. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirsadeghi, S.; Robson, C.A.; Vanlerberghe, G.C. The role of the mitochondrion in plant responses to biotic stress. Physiologia Plantarum 2007, 129, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsigmond, L.; Rigó, G.; Szarka, A.; Székely, G.; Otvös, K.; Darula, Z.; Medzihradszky, K.F.; Koncz, C.; Koncz, Z.; Szabados, L. Arabidopsis PPR40 connects abiotic stress responses to mitochondrial electron transport. Plant Physiol 2008, 146, 1721–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loiacono, F.V.; Walther, D.; Seeger, S.; Thiele, W.; Gerlach, I.; Karcher, D.; Schottler, M.A.; Zoschke, R.; Bock, R. Emergence of Novel RNA-Editing Sites by Changes in the Binding Affinity of a Conserved PPR Protein. Mol Biol Evol 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boos, F.; Muhlhaus, T.; Herrmann, J.M. Detection of Internal Matrix Targeting Signal-like Sequences (iMTS-Ls) in Mitochondrial Precursor Proteins Using the TargetP Prediction Tool. Bio Protoc 2018, 8, e2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Molecular plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC bioinformatics 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; McCarthy, S.A. BCFtools/csq: haplotype-aware variant consequences. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2037–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Aljohi, H.A.; Alromaih, S.A.; Alanazi, I.O.; Lin, Q.; Yu, J.; Hu, S. REDO: RNA Editing Detection in Plant Organelles Based on Variant Calling Results. Journal of computational biology : a journal of computational molecular cell biology 2018, 25, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, F.; Yang, D.C.; Meng, Y.Q.; Jin, J.; Gao, G. PlantRegMap: charting functional regulatory maps in plants. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, D1104–D1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, M.; Lopes, C.T.; Fong, D.; Kucera, M.; Cheung, M.; Siper, M.C.; Huck, G.; Dong, Y.; Sumer, O.; Bader, G.D. Cytoscape.js 2023 update: a graph theory library for visualization and analysis. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).