Submitted:

24 June 2024

Posted:

25 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Material

2.2. Library Construction and Sequencing

2.3. miRNA Identification

2.4. Differential Expression Analysis

2.5. miRNA Target Gene Prediction and Enrichment Analysis

2.6. miRNA-Gene-KEGG Network Regulation and Target Gene Function Analysis

3. Results

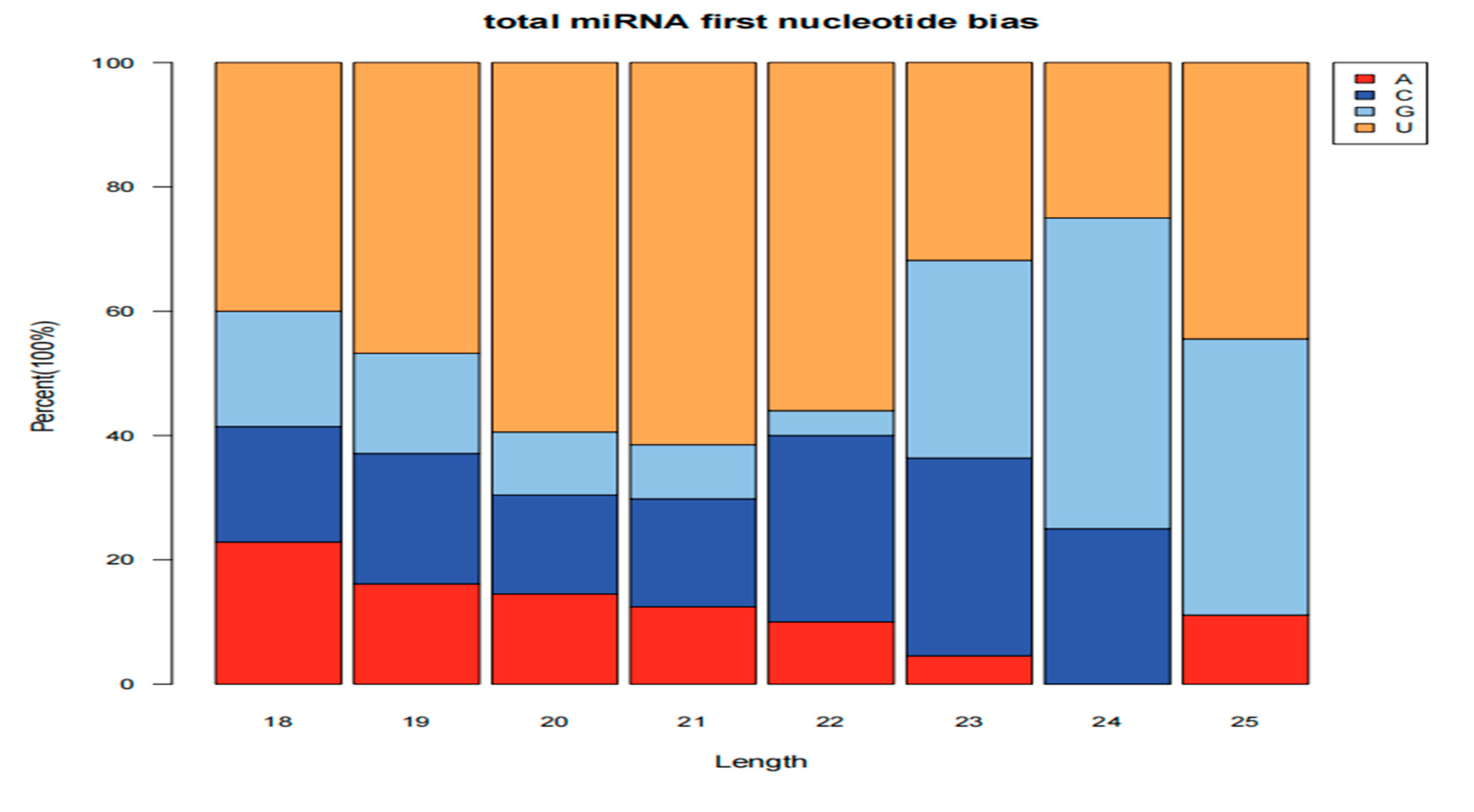

3.1. Identification of miRNAs of Lirianthe Delavayi

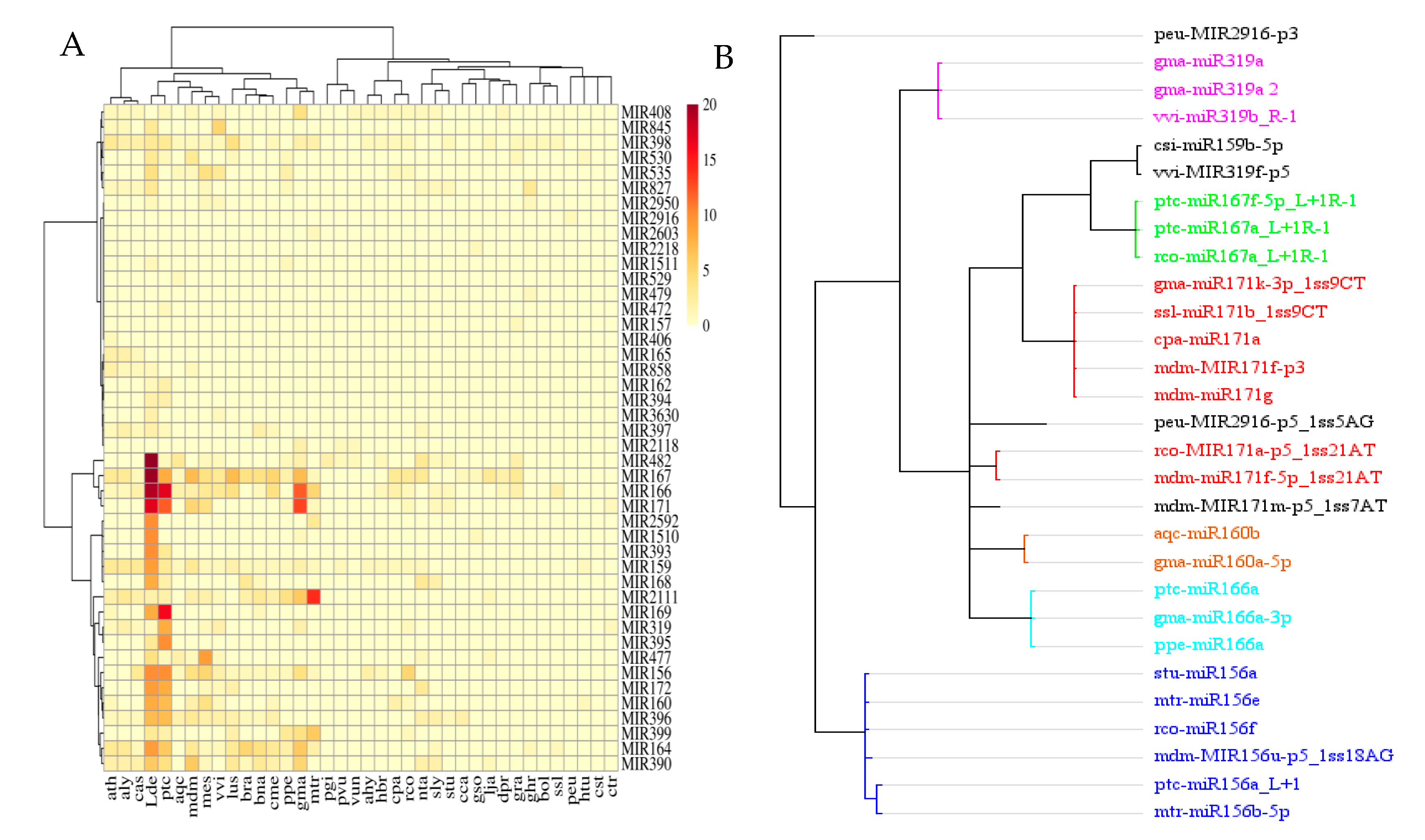

3.1.1. miRNA Family Analysis of Lirianthe delavayi

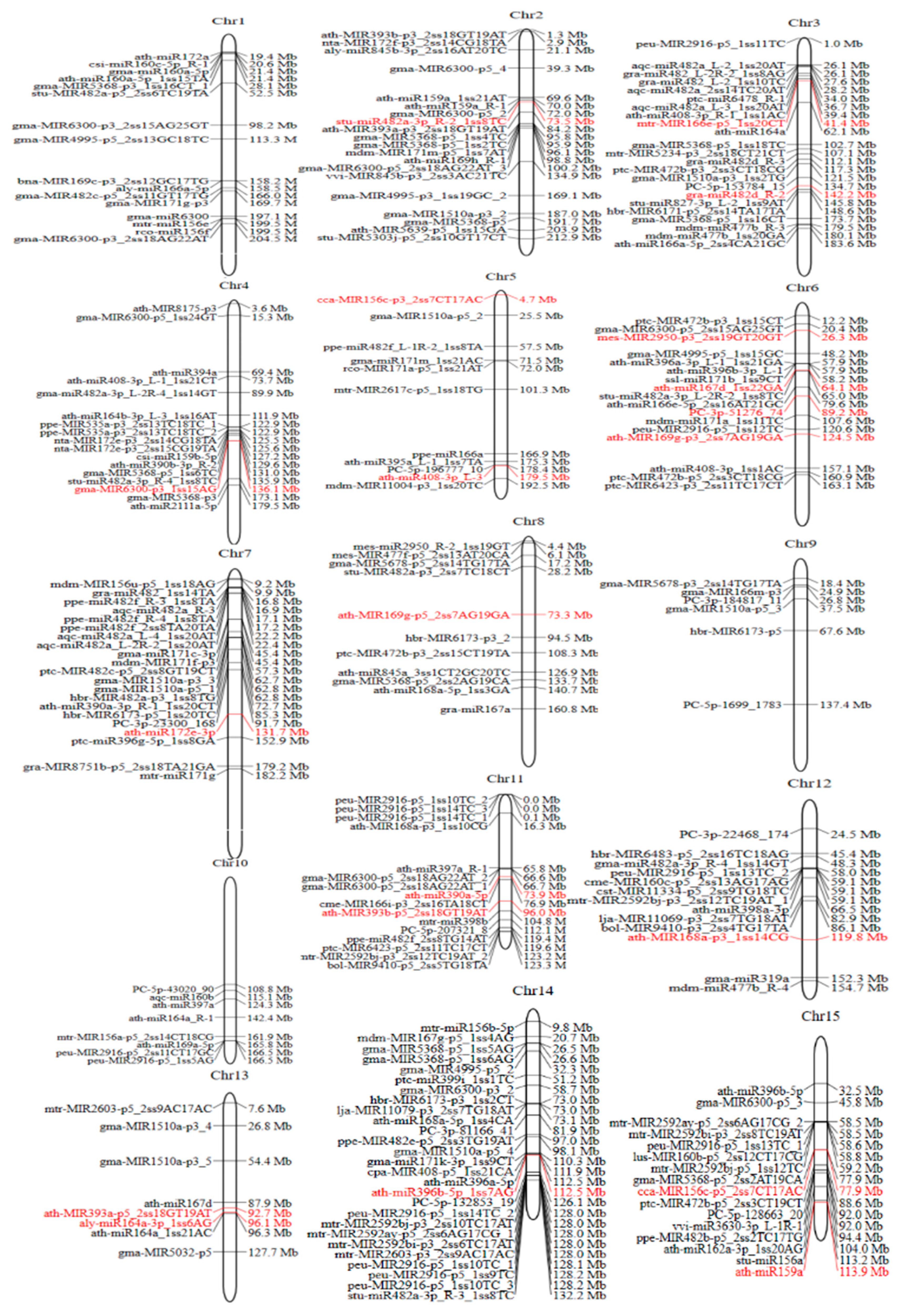

3.1.2. Chromosomal Localization of Identified miRNAs in Lirianthe delavayi

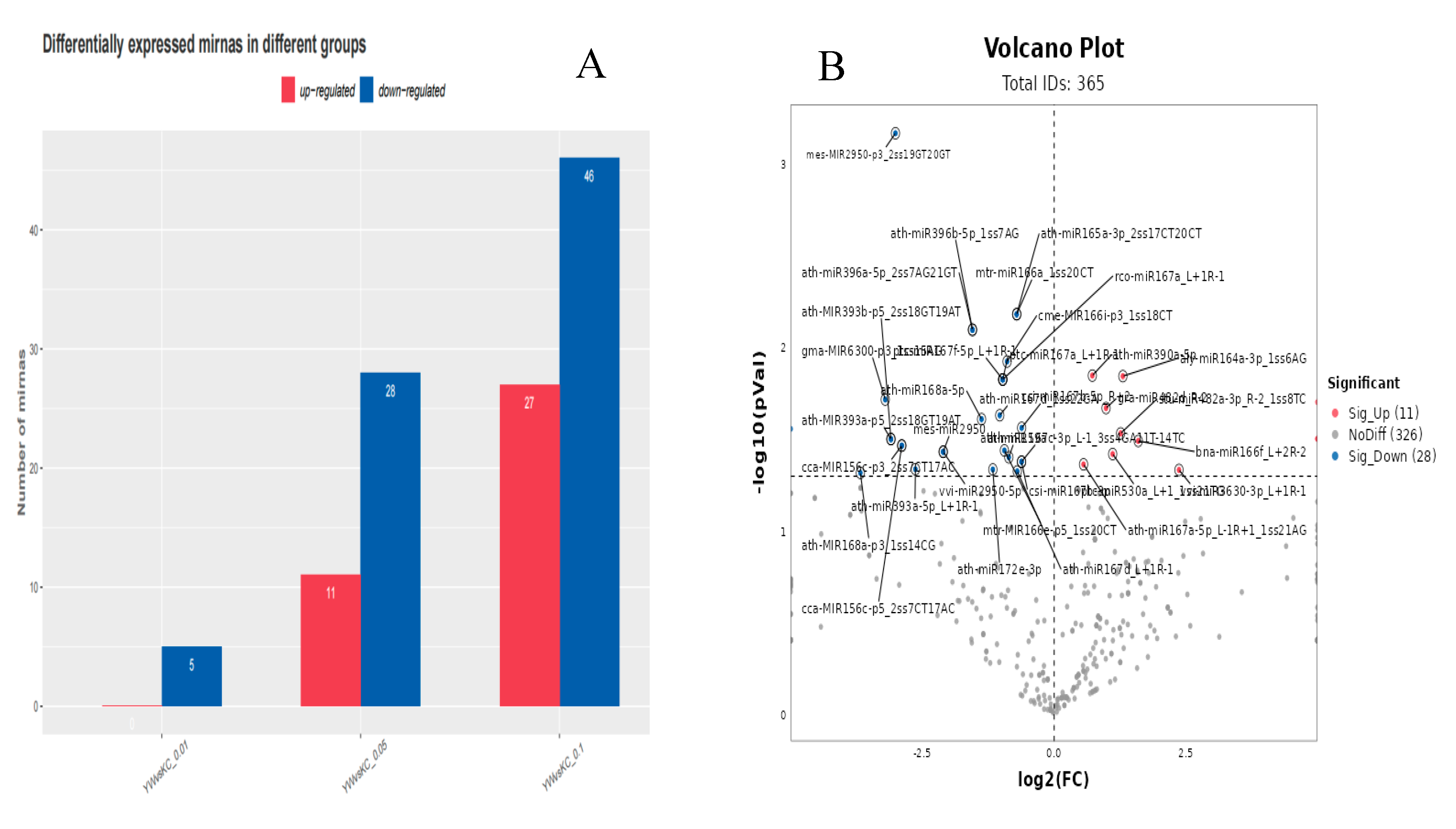

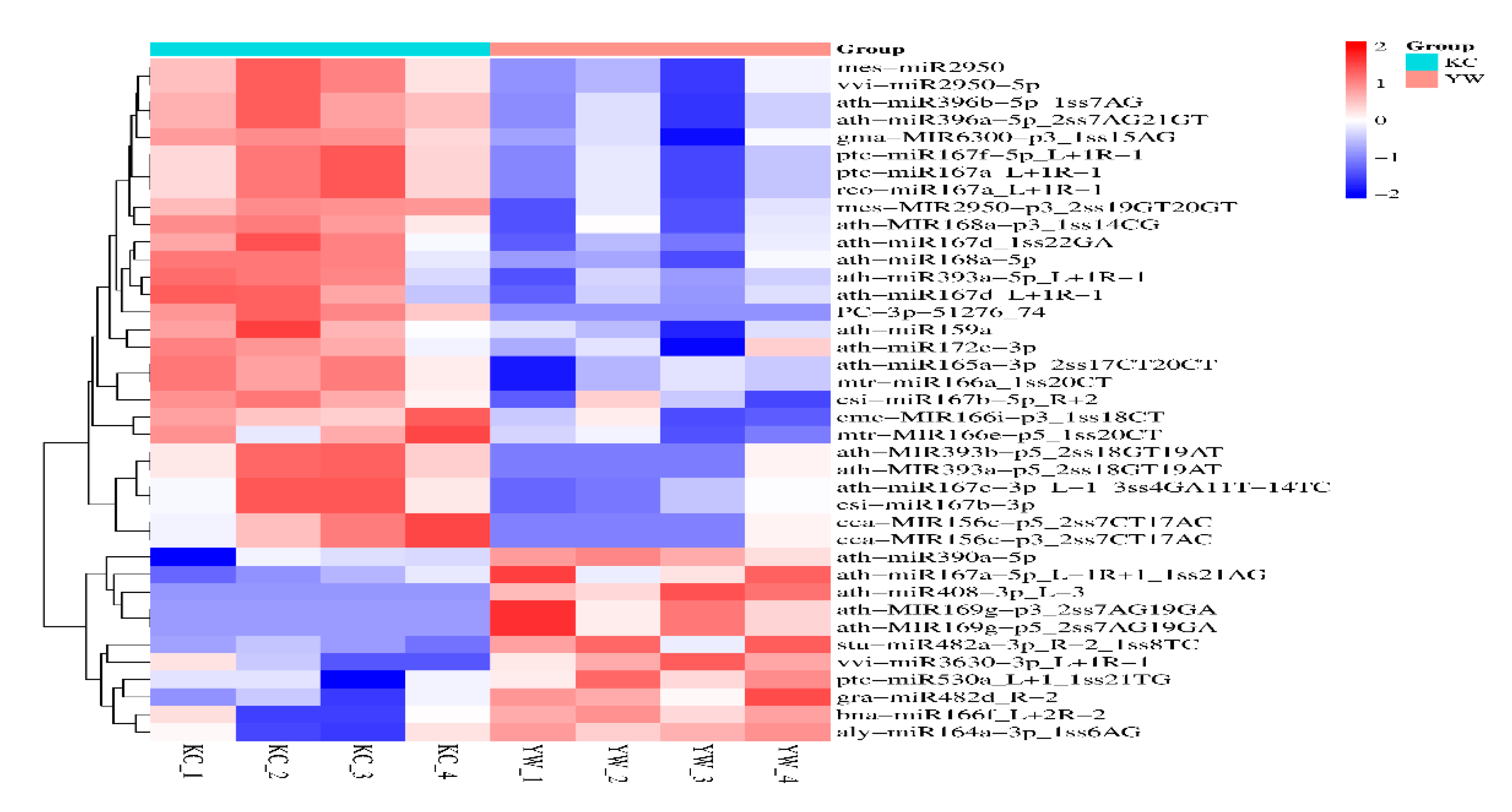

3.2. Differential Expression Analysis of miRNAs in Lirianthe delavayi

3.3. Prediction and Functional Analysis of Target Genes of DEMs in L. delavayi

3.3.1. Target Gene Prediction of DEMs

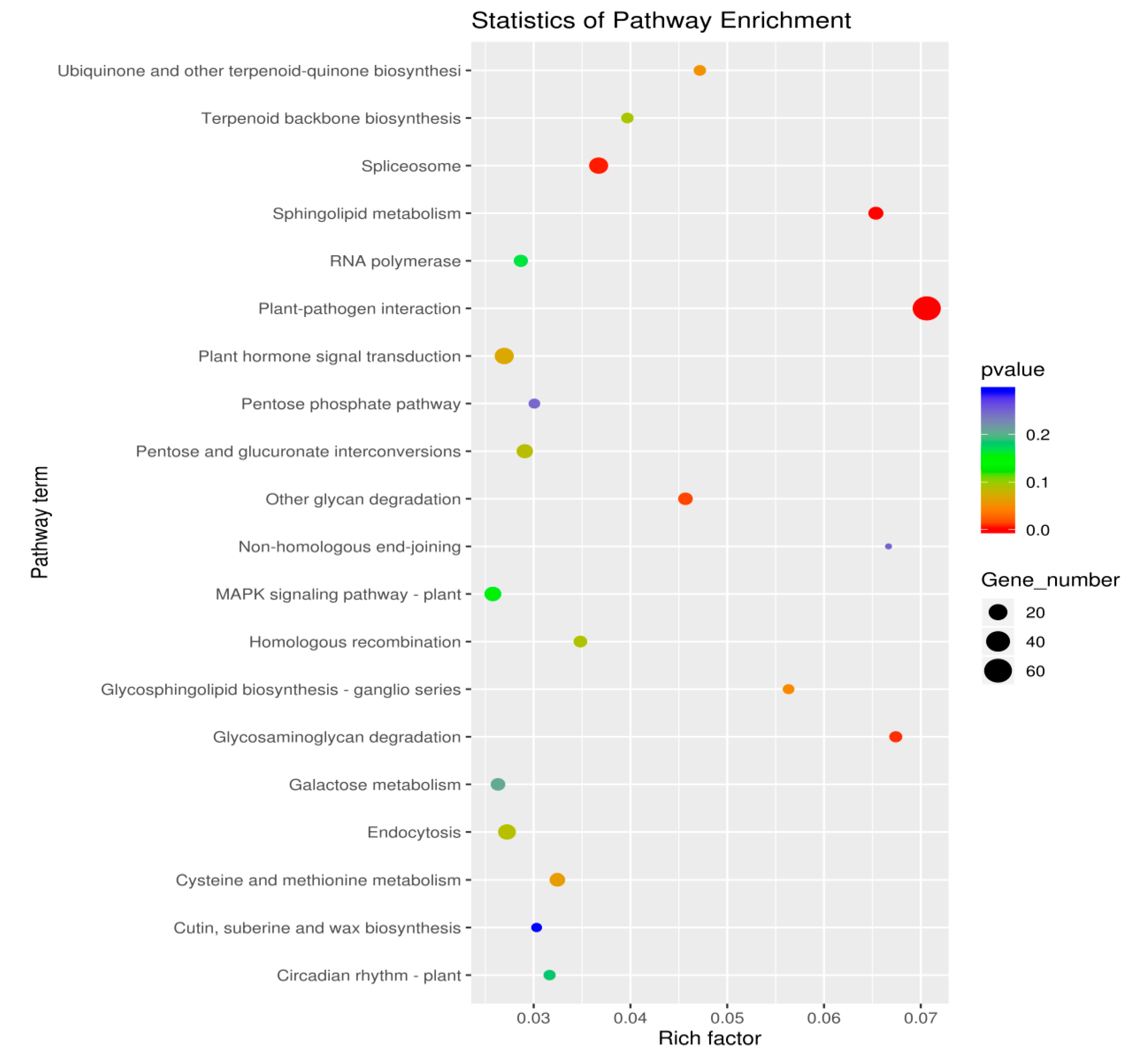

3.3.2. KEGG Enrichment Analysis

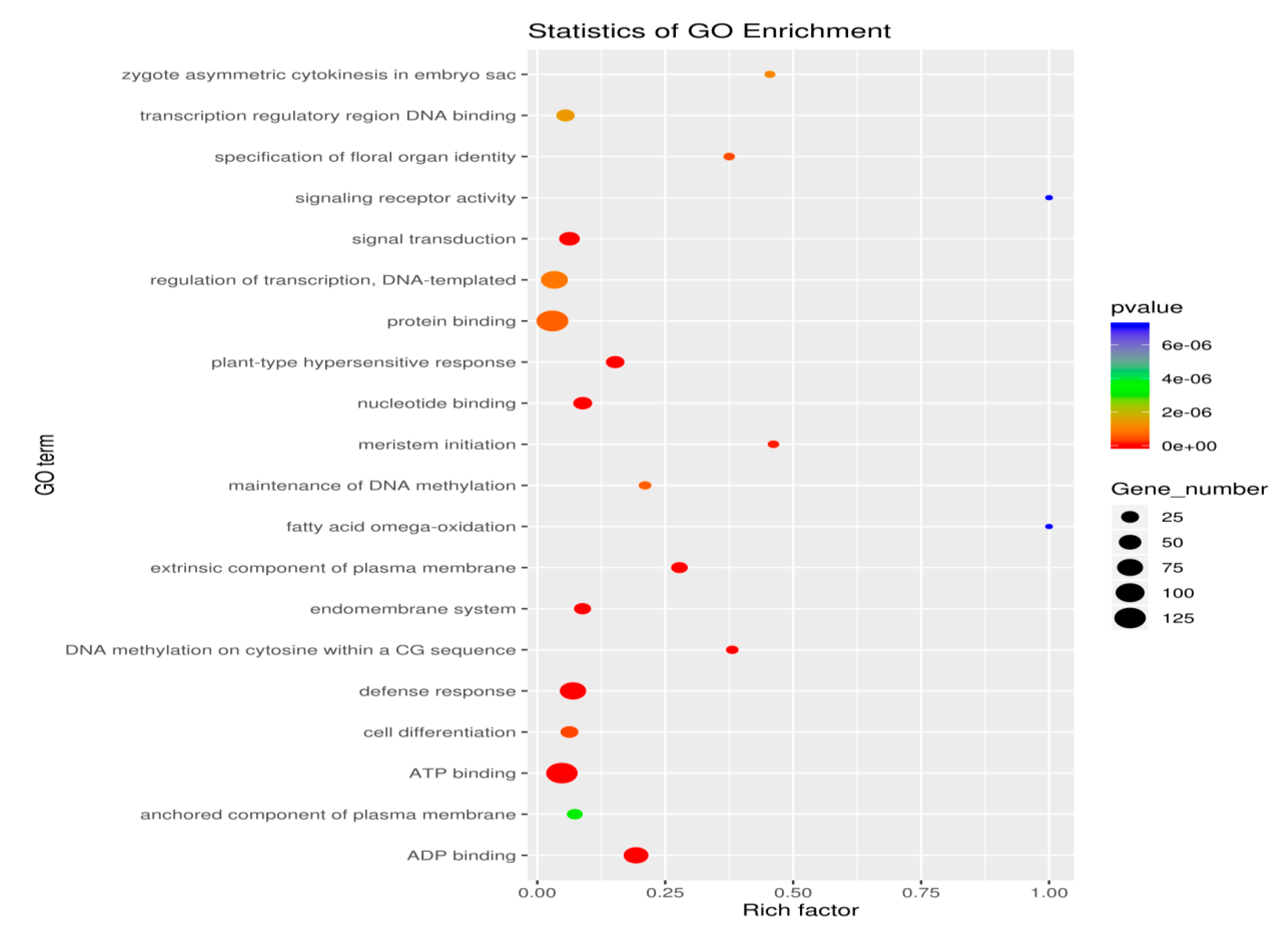

3.3.3. GO Enrichment Analysis

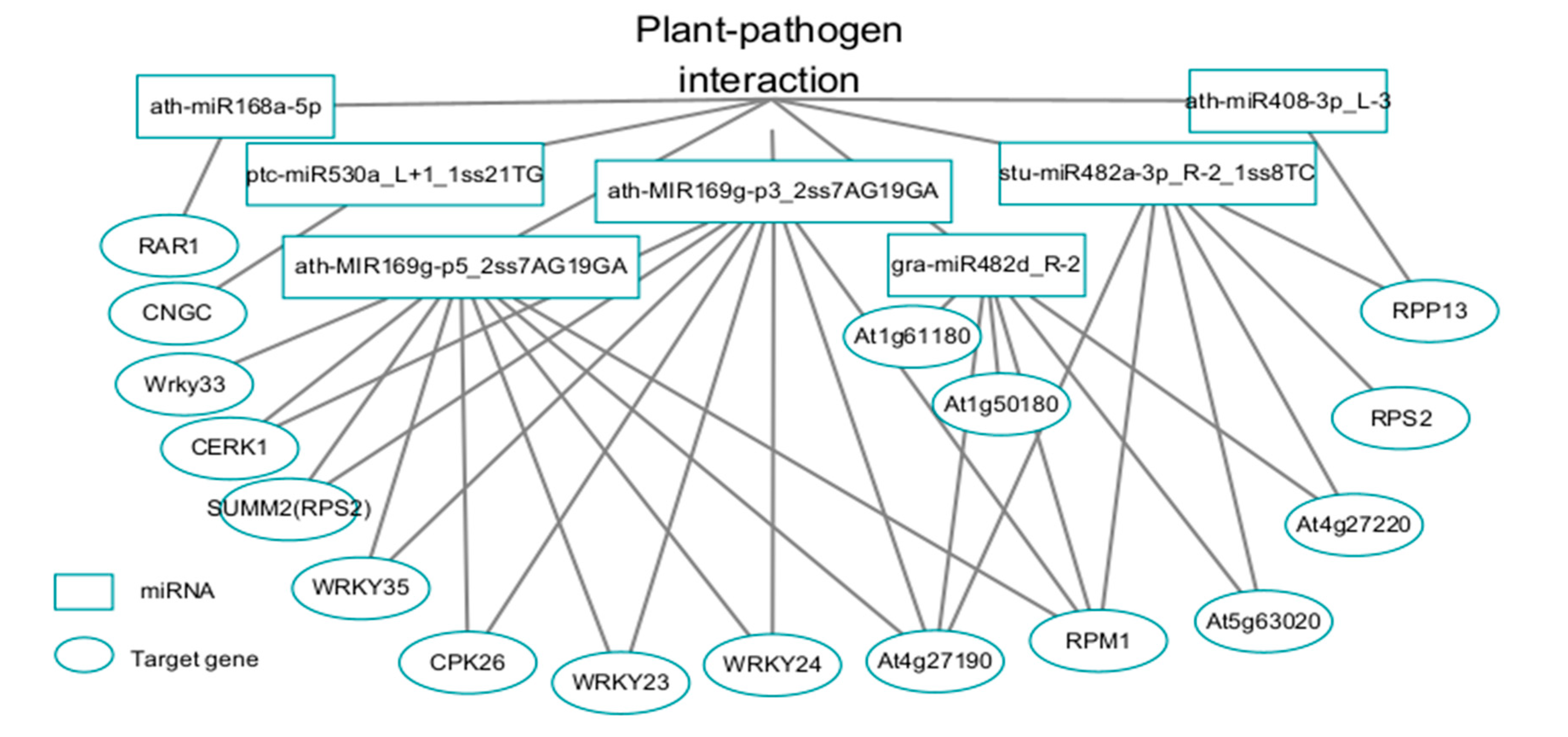

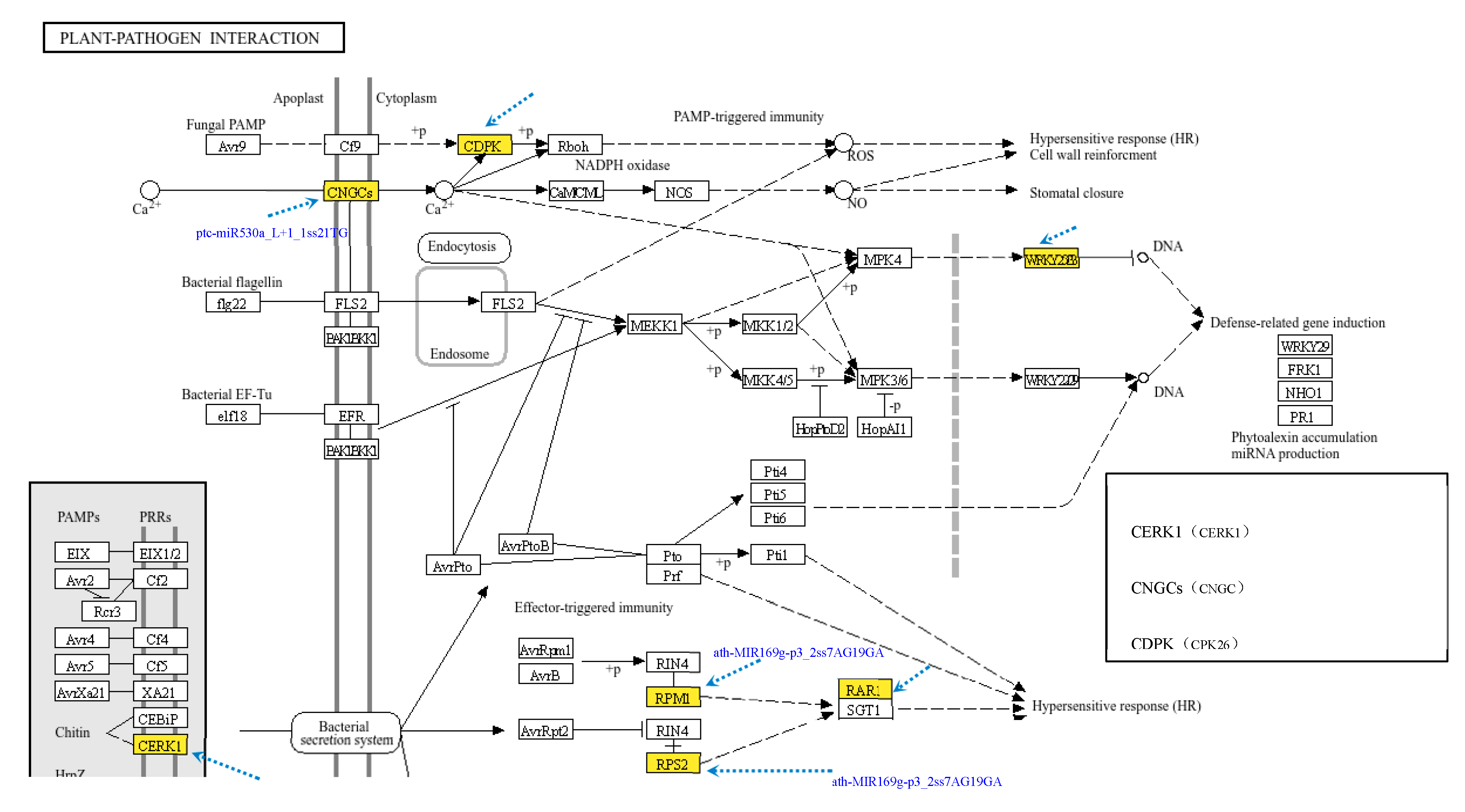

3.4. Analysis of miRNAs and Target Genes Involved in the Plant‒Pathogen Interaction Pathway

3.4.1. Analysis of DEMs in the Plant‒Pathogen Interaction Pathway

3.4.2. Analysis of DEMs and Target Gene Function and Regulation in the Plant‒Pathogen Interaction Pathway

4. Discussion

4.1. Identification and Survey of miRNAs of L. delavayi

4.1. Major Regulatory Pathways of DEMs during the Cultivation of L. delavayi

4.1. Regulation of DEMs and Their Target Genes in the Plant‒Pathogen Interaction Pathway

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chinese Botanical Society; Chinese Academy of Sciences. China flora. Science Press: China, 1996; 30 volumes, Part I.112.

- National compilation group of Chinese herbal medicine. National Compilation of Chinese Herbal Medicine, People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1996.

- Zhu, R.-J. A good tree species for courtyard greening--Lirianthe delavayi. Yunnan Forestry 1985, 01, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.; He, T.-T. Application of Southern Breeding Technology in the Development of Garden Ornamental Plant Resources. Molecular Plant Breeding 2024, 22, 3811–3816. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Adaptation of plants to the environment and utilization of environmental resources. China Resources Comprehensive Utilization 2018, 36, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Chen, L.-Q. Research progress on the regulation of lotus plant type. Journal of Southwest Forestry University (Natural Science) 2024, 44, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, Y.-Y.; LUO, P.; Cui, Y.-Y. Molecular regulation of flower repetalisation in angiosperms. Journal of Botany 2024, 59, 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Chao, J.-T.; Cui, M.-M.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Zong, P.; Sun, Y.-H. Bioinformatics prediction of aubergine microRNAs with their target genes. Hereditas. 2011, 33, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Llave, C. Cleavage of Scarecrow-like mRNA Targets Directed by a Class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science 2002, 297, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasschau, K.D.; Xie, Z.; Allen, E.; Llave, C.; Chapman, E.J.; Krizan, K.A.; Carrington, J.C. P1/HC-Pro, a Viral Suppressor of RNA Silencing, Interferes with Arabidopsis Development and miRNA Function. Developmental Cell 2003, 4, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-M. MicroRNA biogenesis and function in plants. FEBS Lett 2005, 579, 5923–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.H.; Pan, X.P.; Anderson, T.A. Identification of 188 conserved maize microRNAs and their targets. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 3753–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, X.; Qi, Y. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plant-environment interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 489–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, F. Small RNA Sequencing Revealed that miR4415, a Legume-Specific miRNA, was Involved in the Cold Acclimation of. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 870446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Z.-J.; Li, C.-H.; Han, X.-L.; Shen, F.-F. Identification of conserved microRNAs and their target genes in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Gene 2008, 414, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, Q.-L.; Jin, C.-Z.; Lai, L.-Y.; Feng, J.-L.; Chen, S.-N.; Chen, J.-H. Tobacco microRNAs prediction and their expression infected with Cucumber mosaic virus and Potato virus X. Mol Biol Rep 2010, 38, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, T.P.; Xie, F.L.; Freistaedter, A.; Burklew, C.E.; Zhang, B.H. Identification and characterization of microRNAs and their target genes in bobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Plant 2010, 232, 1289–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, R.; Guan, Q.; Shen, C.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, R. Integrated sRNA-seq and RNA-seq analysis reveals the regulatory roles of miRNAs in the low-temperature responses of Canarium album. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajad, S.; Dai, Q.; Yang, J.; Song, J. Identification of miRNAs involved in male fertility and pollen development in Brassica oleracea var. capitata L. by High-Throughput Sequencing. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Jin, X. Genome-Wide identification of selenium-responsive microRNAs in tea Plant (Camellia sinensis LO Kuntze)[J]. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Mao, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, L. MicroRNA identification and integrated network analyses for age-dependent flavonoid biosynthesis in Ginkgo biloba. Forests 2023, 14, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.-H.; Han, X.-W.; Liu, Q.; Dorjee, T.; Zhou, Y.J.; Sun, H.-G.; Gao, F. Joint Analysis of Small RNA and mRNA Sequencing Unveils miRNA-Mediated Regulatory Network in Response to Methyl Jasmonate in Apocynum venetum L. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.M.; Slavov, G.T.; Rodgers-Melnick, E.; Martin, J.; Ranjan, P.; Muchero, W.; Brunner, A.M.; Schackwitz, W.; Gunter, L.; Chen, J.G. Population genomics of Populus trichocarpa identifies signatures of selection and adaptive trait associations. Nature Genetics 2014, 46, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stief, A.; Altmann, S.; Hoffmann, K.; Pant, B.D.; Scheible, W.R.; Baurle, I. Arabidopsis miR156 Regulates Tolerance to Recurring Environmental Stress through SPL Transcription Factors. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L. ; Regulation of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem and lateral organ formation by microRNA miR166g and its AtHD-ZIP target genes. Development 2005, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Val-Torregrosa, B.; Mireia, B.; Segundo, B.S. Crosstalk between Nutrient Signaling Pathways and Immune Responses in Rice. Agriculture 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Xie, B.; Guan, P.; Jiang, N.; Cui, J. New insight into the molecular mechanism of miR482/2118 during plant resistance to pathogens. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1026762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumbur, B.; Gao, F.; Liu, Q.; Feng, D.; Bing, J.; Dorjee, T.; Zhou, Y. The Characterization of R2R3-MYB Genes in Ammopiptanthusnanus uncovers that the miR858-AnaMYB87 Module mediates the accumulation of anthocyanin under osmotic stress. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma Y.-M. wild and cultivated adzuki bean mirnas genome-wide identification and comparative analysis Beijing agronomy courtyard 2016.

- Wu, N.-N.; Zeng, Z.-Y.; Xu, Q.-B.; Zhang, H.-B.; Xu, T. Artificial Cultivation Changes Foliar Endophytic Funga Community of the Ornamental Plant Lirianthe delavayi. Microorganisms 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutz, K.O.; Heilkenbrinker, A.; L€onne, M.; Walter, J.G.; Stahl, F. Transcriptome analysis using next-generation sequencing. Curr Opin Biotech 2013, 24, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Yin, H.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Sang, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, J .; Zhuo, R. Integration of small RNAs, degradome and transcriptome sequencing in hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii uncovers a complex regulatory network and provides insights into cadmium phytoremediation. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2016.

- Xiang, L.; Muhammad, S.; Jinwen, W.; Lan, W.; Xiangdong, L.; Yonggen, L. Comparative Small RNA Analysis of Pollen Development in Autotetraploid and Diploid Rice. Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 499. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.-J.; Ma, Yi.-Ke.; Tong, C.; Meng, W.; Xiu-Jie, W. PsRobot: a web-based plant small RNA meta-analysis toolbox. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 22–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment[J]. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, D480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, B.; Huang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, H.; Wang, S. Small RNA sequencing provides insights into molecular mechanism of flower development in Rhododendron pulchrum Sweet. Scientific reports 2023, 13, 17912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelson; Louise, V.; Napier; Johnathan; A.; Molino; Diana; Faure; Jean-Denis. Plant sphingolipids: Their importance in cellular organization and adaptation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular & Cell Biology of Lipids 2016, 1861, 1329–1335.

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Lan, J.-X.; Wang, S.-Y. Research progress on early signal events of plant defense response. Acta PhytoPhysiologica Sinica 2023, 59, 829–838. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.X.; Yang, Q.L.; Kang, H.W. ; Endosymbiont Buchnera assists aphids in suppressing host plant defense responses. Journal of plant protection 2024, 51, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Debabrata, D.; Kumar, V.A.; Gaurab, G. Amino acid substitution in the conserved motifs of a hypothetical R-protein in sesame imparts a significant effect on ADP binding position and hydrogen bond interaction. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2021, 113101588. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Yang, H.; Mi, K.; Guddat, L.W.; Rao, Z. Conformational Changes in a Macrolide Antibiotic Binding Protein From Mycobacterium smegmatis Upon ADP Binding. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12780954–780954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.; Eastlund, A.; Fischer, C.; Jardine, P. Kinetics of ATP/ADP Binding to the gp16 ATPase. Biophysical journal 2022, 1211909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, H.S. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide gated channel (CNGC) gene family in plants. Plant Physiology Communications 2007, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y. Research progress of calcium-dependent protein kinases in plants. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University 2017, 40, 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H.; Miao, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Xia, C.; Zeng, W.; Sun, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, C. WRKY33-mediated indolic glucosinolate metabolic pathway confers resistance against Alternaria brassicicola in Arabidopsis and Brassica crops. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2022, 64, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, E.; Liu, J. CERK1, more than a coreceptor in plant–microbe interactions. New Phytologist, 2022.

- Alam, M.; Tahir, J.; Siddiqui, A.; Magzoub, M.; Shahzad-Ul-Hussan, S.; Mackey, D.; Afzal, A.J. RIN4 homologs from important crop species differentially regulate the Arabidopsis NB-LRR immune receptor, RPS2. Plant cell reports 2021, 40, 2341–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minsoo Y., J M M,A H E R.A conserved glutamate residue in RPM1-INTERACTING PROTEIN4 is ADP-ribosylated by the Pseudomonas effector AvrRpm2 to activate RPM1-mediated plant resistance.[J]. The Plant cell,2022, 34(12):.

- Prachumporn, N.; Anis, A.; Suthathip, K. Phosphorylation of CAD1, PLDdelta, NDT1, RPM1 Proteins Induce Resistance in Tomatoes Infected by Ralstonia solanacearum. Plants 2022, 11, 726–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Ohnishi, K.; Hikichi, Y.; Kiba, A. Molecular chaperons and cochaperons, Hsp90, RAR1, and SGT1 negatively regulate bacterial wilt disease caused by Ralstonia solanacearum in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant signaling behavior, 2015, 10, 970410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao; Qunqun; Wu; Jiajie; Pei; Hongcui; Lv; Bo; Fu; Daolin. The HSP90-RAR1-SGT1-based protein interactome in barley and stripe rust. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2015, 9111–19.

- Zhou, Z.; et al. Resequencing 302 wild and cultivated accessions identifies genes related to domestication and improvement in soybean. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Lozano, R.; Kim, J.H.; Bae, D.N.; Jeong, S.C. The patterns of deleterious mutations during the domestication of soybean. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, R.K.; Thudi, M.; Roorkiwal, M.; et al. Resequencing of 429 chickpea accessions from 45 countries provides insights into genome diversity, domestication and agronomic traits. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.I.; Bi, I.V.; Schroeder, S.G.; Yamasaki, M.; Doebley, J.F.; McMullen, M.D.; Gaut, B.S. The effects of artificial selection on the maize genome. Science 2005, 308, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauser, G.; Marti, G.; Villard, N.; Doyen, G.A.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Induction and detoxification ofmaize 1,4-benzoxazin-3-ones by insect herbivores. PlantJournal 2011, 68, 901–911. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts, P. Crop domestication as a long-term selection experiment. Plant Breeding Reviews 2004, 24, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Purugganan, M.D.; Fuller, D.Q. The nature of selection during plant domestication. Nature 2009, 457, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittner·Eddy, P.D.; Crute, L.R.; Holub, E.B.; Beynon, J.L. RPP13 is a simple locus in Arabidopsis thaliana for alleles that specify downy mildew resistance to different avirulence determinants in Peronospora parasitica. Plant 2000, 21, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

| miR_name | miR_seq | up/down | fold_change (KC/YW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ath-miR168a-5p | TCGCTTGGTGCAGGTCGGGAA | up | 1.38 |

| ath-MIR169g-p3_2ss7AG19GA | CATGATGATGATGATTACA | down | -inf |

| ath-MIR169g-p5_2ss7AG19GA | CATGATGATGATGATTACA | down | -inf |

| ath-miR408-3p_L-3 | CACTGCCTCTTCCCTGGC | down | -inf |

| stu-miR482a-3p_R-2_1ss8TC | TTTCCAACTCCACCCATTCC | down | -2.40 |

| gra-miR482d_R-2 | TTTCCTATGCCCCCCATTCC | down | -1.98 |

| ptc-miR530a_L+1_1ss21TG | CTGCATTTGCACCTGCACCTG | down | -2.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).