3.4. Distillation Profile

All marine diesel samples analyzed have recovered 65% v/v at 250 °C. The 85% v/v recovery was achieved at 350 °C, and also the T95 value was below the 360 °C. Examining the dataset the recovery of 250 °C ranged from 29.5% v/v to 48% v/v, the 350 °C recovery from 87% to 97.5% v/v, and T95 fluctuated from 343 °C to 354 °C. Thus, the sample examined were in accordance even with the specification limits of ELOT EN 590 automotive diesel specifications, showing that the fuels are operational.

The samples were assessed by their volatility, and three behavioural families were recorded. The most volatile group contains the following nine samples with the following encoding: 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20, 29 and 34. In this family, the samples start to boil in a low temperature as shown by T10 value since it was between 168 °C and 204 °C, such as 11 (168 °C), 12 (174 °C), 13 (193 °C), 14 (205 °C), 15 (188 °C), 19 (206 °C), 20 (210 °C), 29 (198 °C) and 34 (198 °C). These values imply an excellent behavior of fuel at low temperatures satisfying an easy engine start-up at low temperatures and smoothness in engine warm-up, although the volatility in high front-end recovery may set risks for fuel vaporization in higher temperatures climate conditions. Regarding the Sample 34, its T10 value is recorded at 198 °C, which is rather light, but showing a T50 value of 260 °C, indicating the mid-range fractions. This sample is classified at this group, since the profile of distillation curve is characterized by the early initial boiling point.

The other broad behavioral family is the mid-range family, including the following samples: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 16, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32 and 33. The dataset shown that T10 values are between 193 °C and 220 °C. The T90 values lied in the range of 315 °C and 341 °C and T95 were between 347 °C and 354 °C. The yield at 250 °C was from 30% v/v to 44 % v/v and at 350 °C was from 95% v/v to 97 % v/v recovery. These fuels include a light fraction satisfying engine cold start-up, a mid-section fraction showing stable combustion and a heavy-end fraction supporting an adequate flash point and stability during storage. In the case of sample 4, the T10 values were at 170 °C, which is a rather low value, but it lies in this category because the other characteristics belong to the mid-range pattern.

A heavier-front fraction includes samples 7, 8, 27 and 28. Evaporation starts up in the range of 205 to 217 °C. Specifically, the sample 7 at 216 °C, sample 8 at 217 °C, sample 27 at 217 °C and sample 28 at 217 °C. The half of the fuel has distilled in the range of 254–278 °C, such as 254 °C for sample 7, 254 °C for sample 8, 278 °C for sample 27 and 278 °C for sample 28. The recovery at 250°C was recorded between 30 % and 32 % v/v, specifically 32 % v/v for sample 7 and 30.5 % v/v for sample 8. As well as the recovery at 350 °C was in the range of 94.5–96 % v/v, showing 94.5 % v/v for sample 7 and 96 % v/v for sample 8, 27 and 28. T90 values were between 334 °C to 339 °C and T95 between 347 °C to 354 °C. It is worth noticing that the higher values of initial boiling temperatures enhance the flash point indication and the fuel thermal stability, being a significant advantage for vessels which demand long-term fuel storage.

Sample 30 is characterized as an outlier. Although the T95 value was recorded at 354 °C, the yield 350 °C was at only 87 % v/v, being the lowest value noted in the dataset, implying an abnormal percentage of high heavy-tail fraction, which may be justified by the water ingress, or any contamination from residual oil or incomplete refining processes. If this marine diesel fuel is used without treatment, the exhaust gases may produce smoke, formation of soot and injectors fouling and deposits on combustion chambers. In such fuel, the treatment demands blending with a lighter fuel.

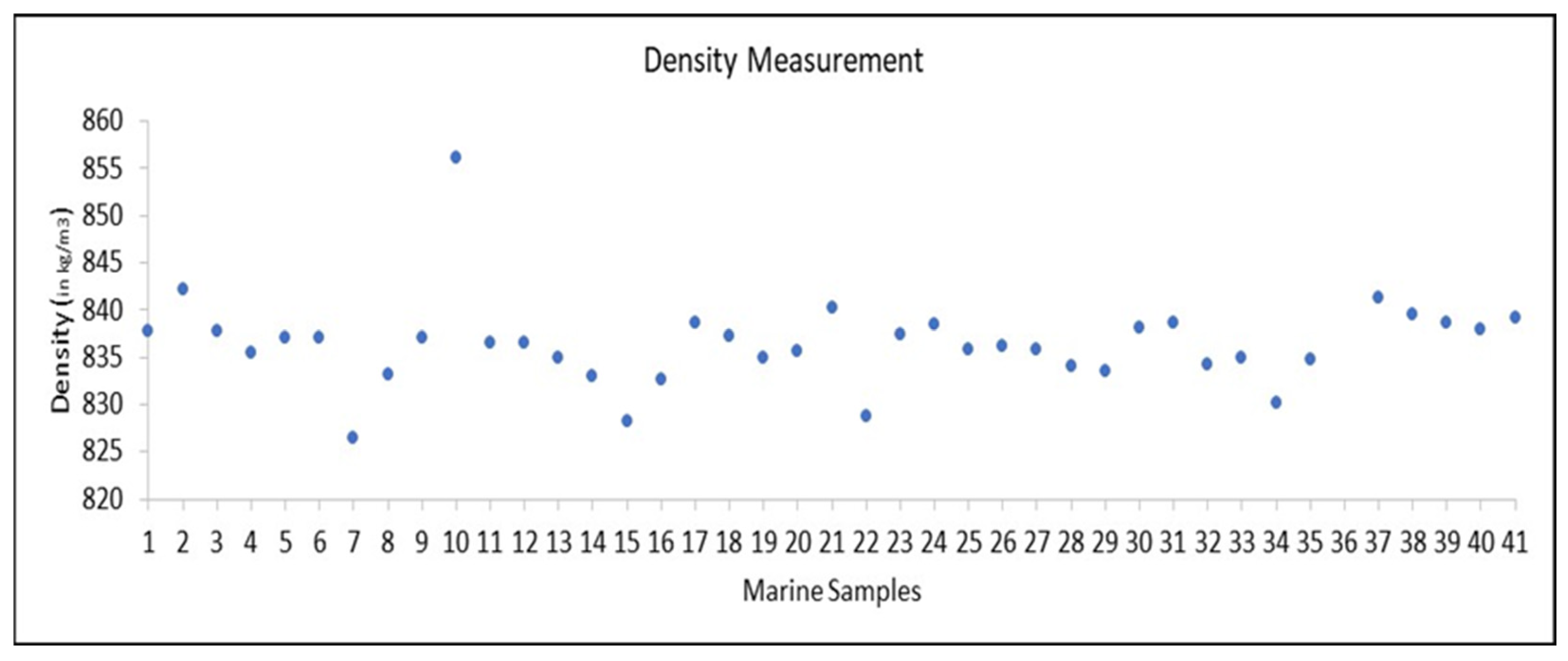

Regarding the other samples from 35 to 41 they were not succumbed to the determination of the characteristics of distillation profile. It is worth noticing that the other physicochemical properties such as density measurement, viscosity, water content and flash-point determination were within DFA specifications as determined in the National and International Standard ELOT ISO 8217:2024. Their organoleptic appearance was good without the sediment formation. It is logical to conclude that the missing samples were within the specification limits.

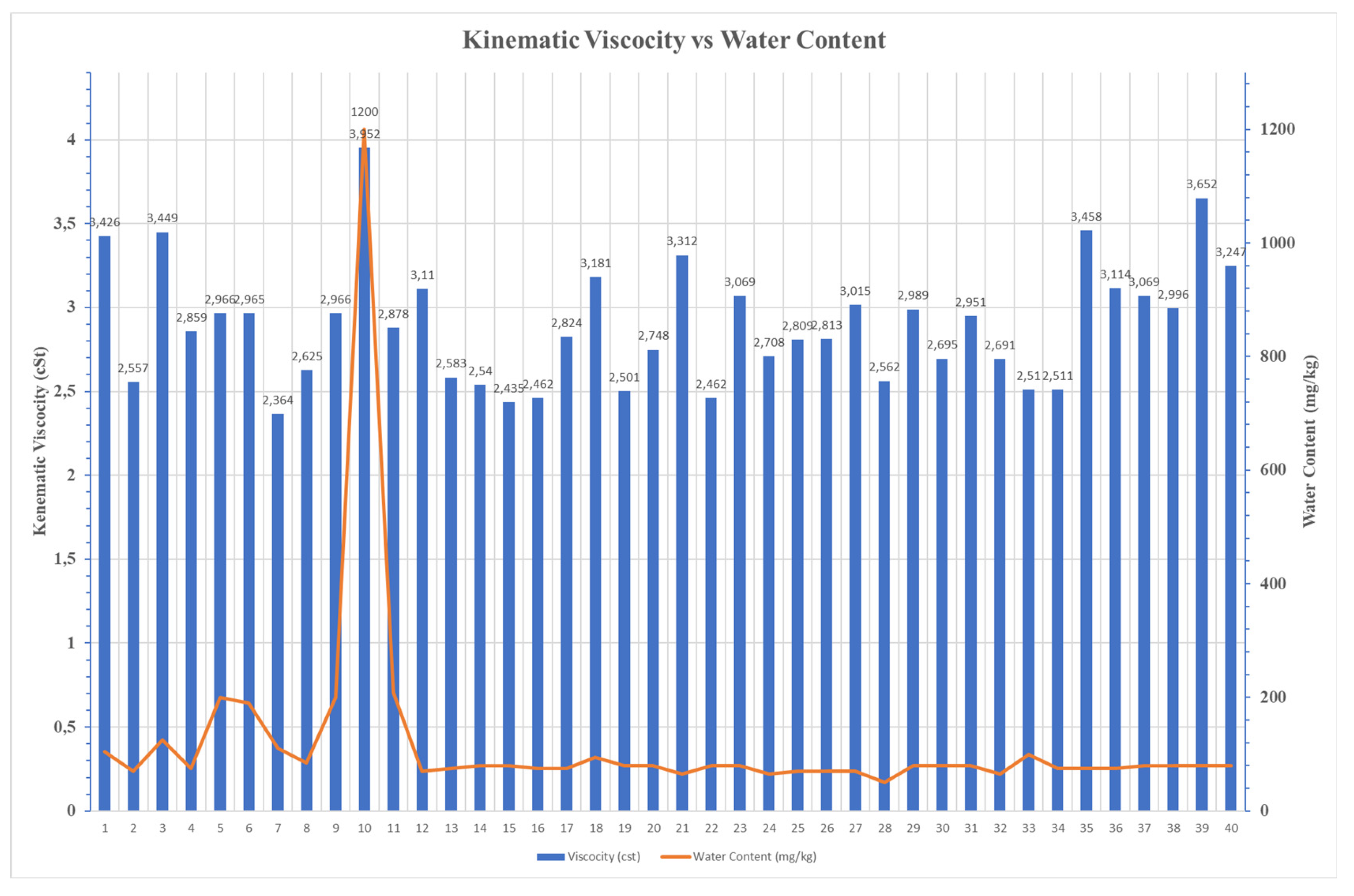

Summarizing, except from the heavy-tailed marine diesel fuel as Sample 30, and sample 10 which was with a significant water content of 1200 mg/kg, the rest samples showed conventional distillation characteristics for DFA fuel, attributing to an adequate cold-start performance, combustion smoothness, thermal stability and storage stability, being in compliance with the ELOT ISO 8217 for marine diesel fuels.

3.7. Elemental Contamination - ICP-OES Analysis

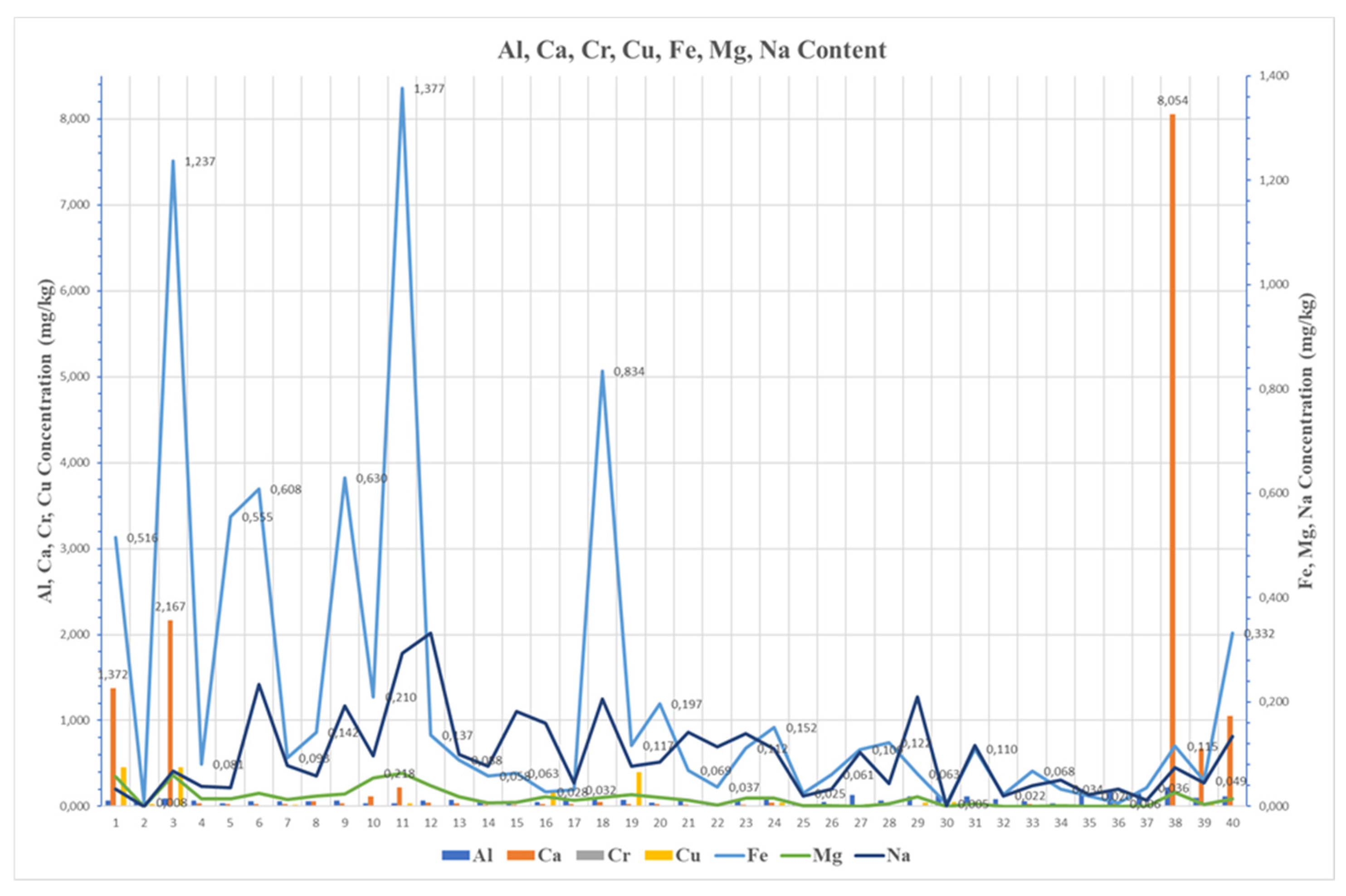

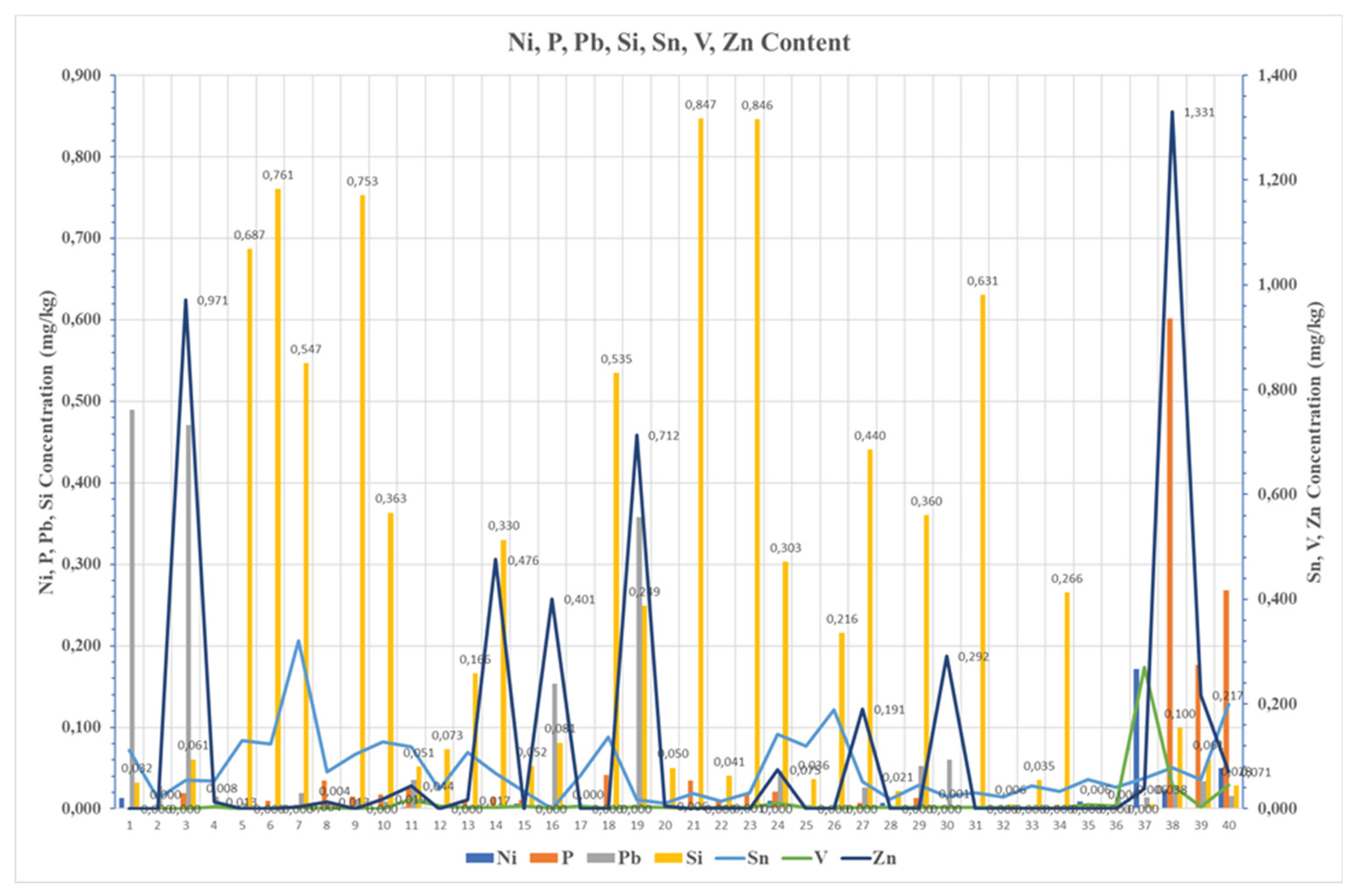

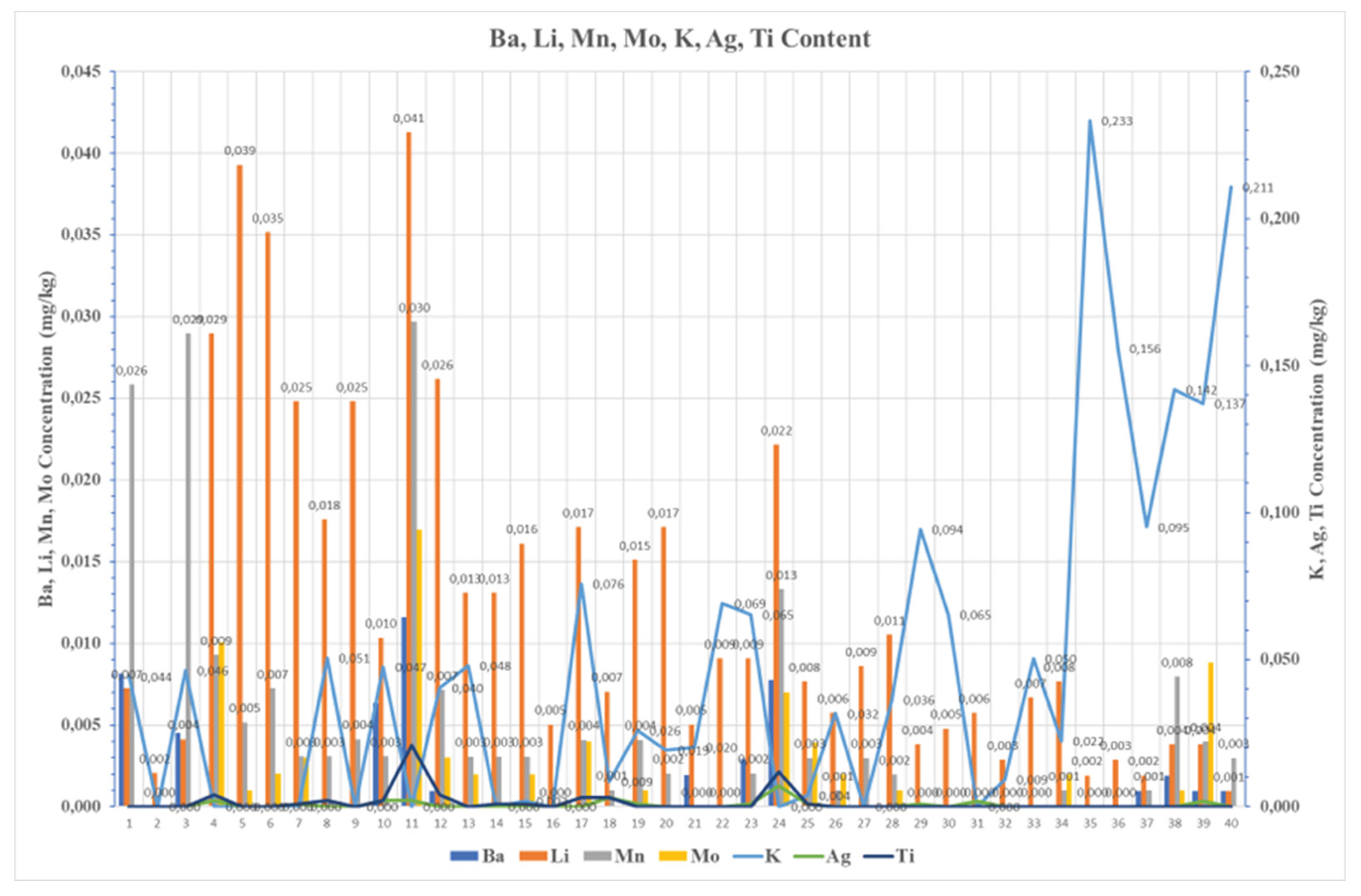

The measurements of the marine diesel fuel samples via Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) highlighted a variety of metals by recording not only the high-quality excellent fuels, but also those influenced by strong contamination, degradation pathways, or poor handling.

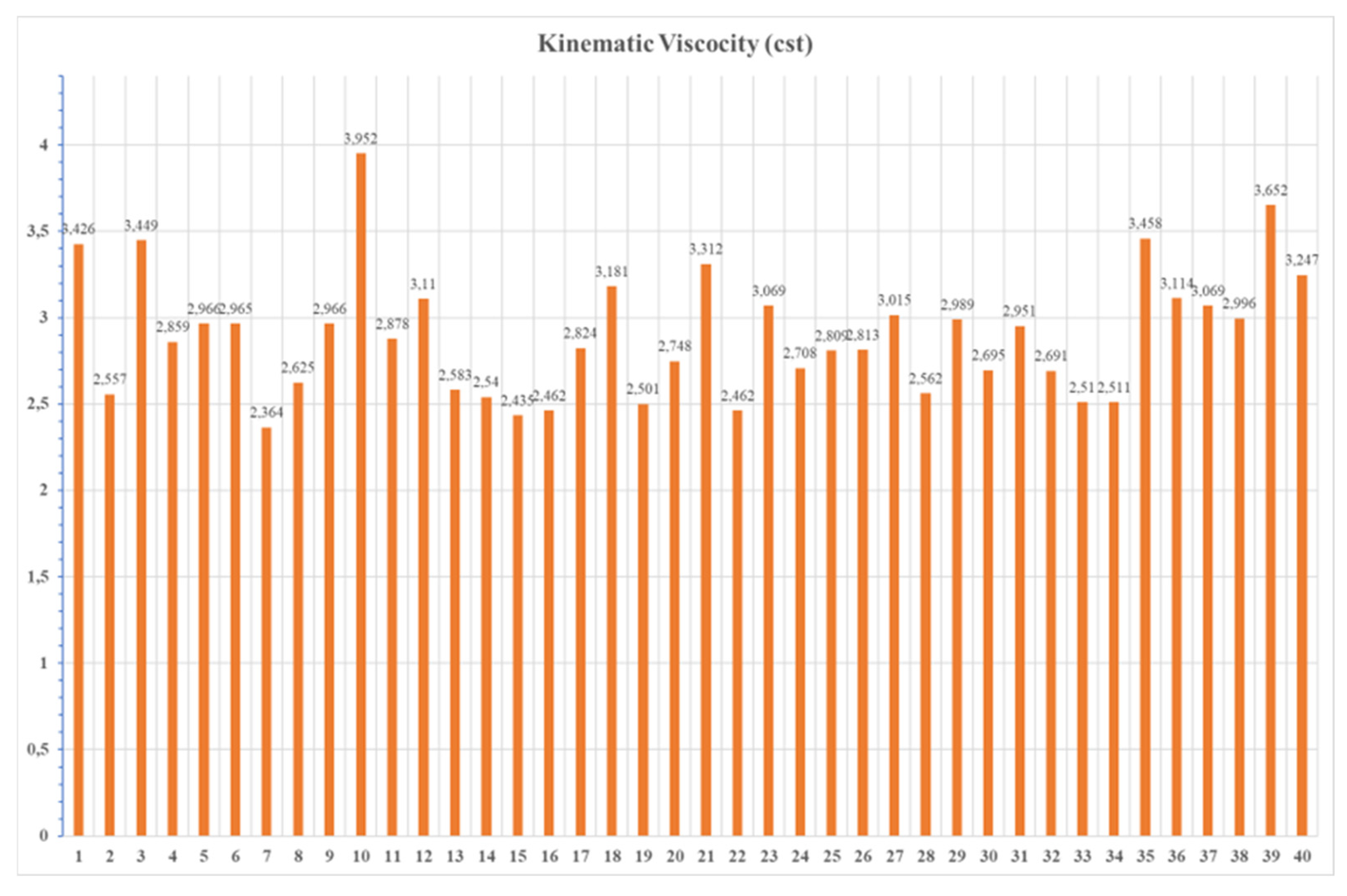

In the current work, it was observed from the samples’ analysis that higher viscosity is an indicator of fuel behavior. The higher fuel viscosity is strongly correlated with a high concentration of metal content, recommending that the physical fuel properties can serve as a reliable indicator of its chemical purity and contamination level.

This before-mentioned correlation is confirmed by the SPSS analysis, a statistical analysis through showing a significant positive relationship between viscosity and total contamination (r = 0.361, p = 0.022), as well as moderate to strong associations between viscosity values and key metallic compounds as Copper (r = 0.152), Iron (r = 0.299), Magnesium (r = 0.419), and Lead (r = 0.551). The correlation coefficient (R-value) measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between the two variables, ranging from -1 (perfect negative) to +1 (perfect positive), with 0 indicating no relationship. The p-value indicates the statistical significance of this relationship, determining the probability that the observed correlation is due to chance. A p-value below the chosen 5% (0.05) significance level suggests the correlation is statistically significant and likely not a random occurrence.

These findings may be justified by the statement that while the metal contents elevated, the internal resistance of the fuel increases, giving as result a greater viscosity. This phenomenon was strongly confirmed in the case of transition metals and elements which are used as additives. This phenomenon can be explained by the physicochemical behavior of metal ions in hydrocarbon matrices: multivalent ions such as Fe³⁺, Cu²⁺, and Al³⁺ form hydrated complexes and interact with polar compounds or organic ligands, increasing molecular interactions and fluid resistance.

Additionally, suspended oxides of metals, colloidal particles, and categories of insoluble byproducts from degradation stages attribute to the increase of contamination load and to the thickening of the fuel, strengthening the correlation of rheological properties and elemental content. The strongest correlations between total contamination and higher viscosity values were observed for:

• Phosphorus (r = 0.722, p < 0.001),

• Calcium (r = 0.679, p < 0.001), and

• Zinc (r = 0.595, p < 0.001).

All these metallic compounds are components of lubricating oil as additives, particularly they are included into Zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZDDP). According to the current results, there is a rather strong correlation between Phosphorus and Calcium (r = 0.895, p < 0.001), denoting a contamination from possibly engine lube oil, which may happened due to handling transfer issues by cross-contamination from inadequate cleaning of tanks.

This statement is most evident in sample No. 39, which exhibited extreme levels of Calcium (8.054 mg/kg), Phosphorus (0.602 mg/kg), and Zinc (1.331 mg/kg), making it a clear outlier with severely compromised fuel quality. Thus, such contamination set operational risks, involving the formation, injector coking, and catalyst poisoning, all of which are exacerbated by the observed increased viscosity in the sample. Similarly, Samples 40 and 41 showed elevated levels of the same additive-related elements, confirming a recurring contamination issue that demands strict quality control and handling protocols.

The presence of Copper and Lead was nearly perfectly correlated (r = 0.996, p < 0.001), indicating a shared origin, most likely corrosion from Brass, Bronze, or Bearing materials in fuel system components, a process that also contributes to increased particulate load and viscosity. Similar pattern was observed for Iron, Magnesium, and Manganese indicated through a mutual relationship between higher values of viscosity and contamination, implying mechanical wear, rust, suspended particulates.

Silicon and Sodium frequently appeared together in increased concentrations. Their presence in sample No. 5, 6, 21, and 23, showed environmental contamination from airborne dust and potential seawater ingress likely due to poor sealing of tanks or poor storage.

Particularly, Sodium showed strong correlation with magnesium and other alkali metals, highlighting its origin from marine environments. On the contrary, sample No. 2 showed a minimal content of trace metals, indicating high purity fuels and simultaneously good practices during handling. As well as sample No 1, which was collected from the bottoms of the tank, presented a high calcium and copper content, implying the presence of additives and corrosion pathway. In case of Sample 3, a similar pattern was observed. An increased content of Calcium, Iron, and Barium was noticed, which is explained by additive use and mechanical wear, whereas sample No. 4 demonstrated low metal concentration and balanced properties, reflecting a satisfying fuel quality. As well as samples No 5 and 6 showed elevated Silicon, Iron, and Sodium, implying again environmental contamination. Sample No. 7 showed low density and high Tin and Silicon, implying light fuel fractions and a possible influence of additives into its composition, while sample No. 8 showed a moderate influence of metallic compounds such as Sodium and Potassium, which may be explained by detergent residues agents. Similar observations were in Samples No. 9 and No. 18 both exhibited high iron, silicon, and sodium, making strong concerns about wear and environmental exposure.

Sample No. 10 revealed high water concentration of (1,200 mg/kg), promoting in this way the formation of emulsions in marine fuel and simultaneously the microbial growth, leading to fuel instability and increased viscosity. Similarly, sample No. 11 showed high Iron, Sodium, and Chromium, indicating corrosion and wear. Sample No. 12 showed low contamination and acceptable quality, while samples No. 13 and 14 had elevated concentration of silicon and zinc, indicating dust ingress and corrosion from galvanized components. samples such as No. 15 and No. 17 showed extremely low metal content, showing excellent fuel quality. On the other hand, sample No. 16 showed elevated content of Copper and Vanadium which is possible explained as a type of wear maybe by heat exchanger contamination.

The recurring presence of Iron, Silicon, and Sodium in multiple samples reinforces issues correlated to wear of mechanical components and environmental exposure, all of them contribute to an elevated viscosity and poor fuel performance. Overall, the dataset presented in the current work shows that the viscosity value is not only a physical property but a significant medium showing contamination in a severe form, specifically when it is correlated with elemental analysis.

Similarly, samples No. 40 and 41 showed elevated levels of the same additive-related elements, confirming a recurring contamination issue that demands strict quality control and handling protocols. The presence of Copper and Lead was nearly perfectly correlated (r = 0.996, p < 0.001), indicating a shared origin, most likely corrosion from brass, bronze, or bearing materials in fuel system components, a process that also contributes to increased particulate load and viscosity. Iron, magnesium, and manganese showed strong mutual correlations and were linked to both viscosity and contamination, suggesting contributions from mechanical wear, rust, or suspended particulates.

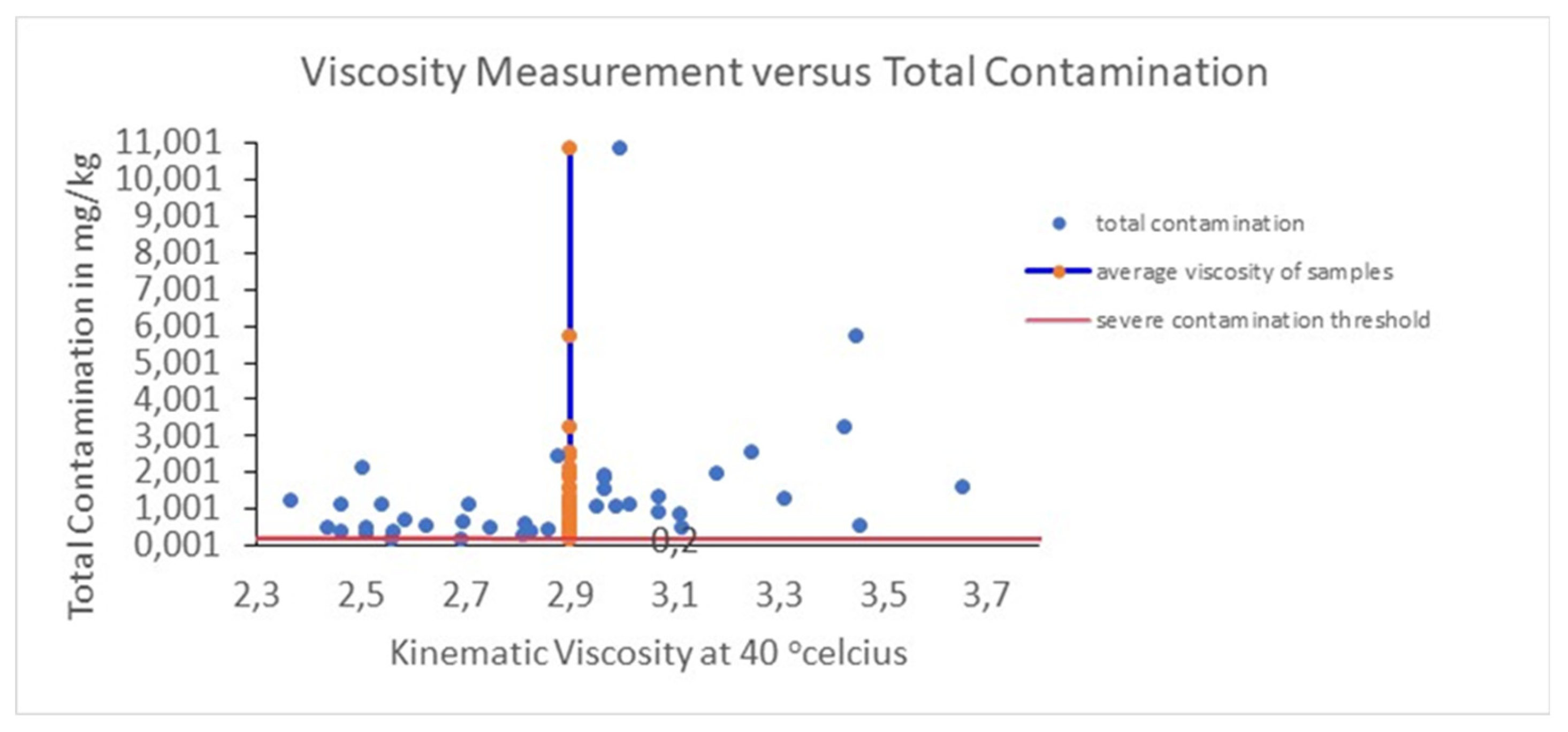

The statistical analysis is in alignment with the observations in

Figure 5, which depicts the viscosity measurements against total contamination from metallic compounds. In

Figure 5 a red horizontal line represents the lower limit of significant contamination of 0.2 mg/kg. This is the threshold value which was determined by the injection system manufacturers for the automotive industry. Although there were two samples which were below the threshold, the rest surpassed the limit of metallic contamination of 0.2 mg/kg, setting risk in engine performance, reaching in one case even above 10 mg/kg. This finding underscores that the increase of viscosity is correlated with the metals presence and compounds used as fuel additives. All these contaminants influence the fuel chemical composition through promoting intermolecular interactions and driving to the thickening of fuel.

Thus, the statistical analysis and the graph verify that kinematic viscosity determined at 40 °C can be used as an indicator related with the purity of marine diesel. The monitoring of viscosity in a parallel way with elemental analysis provides the ability to detect in an early stage any kind of cross-contamination or adulteration with lubricating oil during handling, transportation and dispersion, as well as degradation of infrastructure-related issues, satisfying an integrated process in order to guarantee the quality of fuel and the performance of engine.

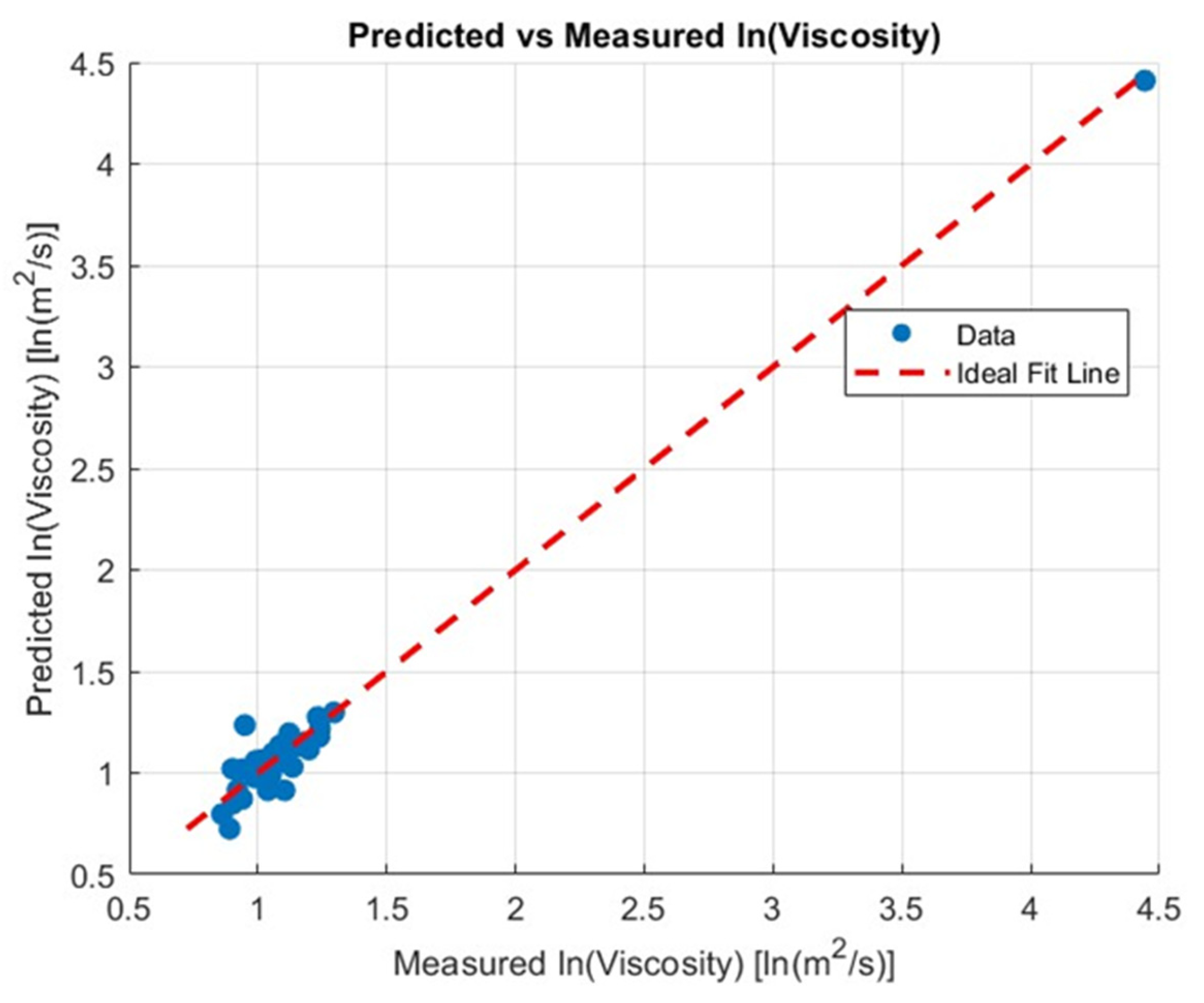

The nonlinear model presented in 2.12 was fitted to the measured viscosity data. The predicted viscosity values show good agreement with the experimental measurements, as illustrated in

Figure 6, where measured versus predicted viscosities are plotted on a logarithmic scale. The scatter plot indicates that the model captures the trends of the data across the studied concentration ranges. Table Y summarizes the estimated model coefficients (α,b_i) along with the coefficient of determination (R^2=0.99863), which demonstrates the model’s accuracy in reproducing the observed viscosities. These results confirm that the proposed model provides a physically meaningful approximation for predicting the viscosity of different compositions within the tested ranges.

The findings show that Biodiesel - FAME concentration in marine diesel fuel is a factor, but the results indicated that the foremost drivers of fuel degradation and contamination are the housekeeping and environmental conditions during storage period and the corresponding compatibility of the infrastructure. This statement was verified through outliers which were faced such as introduction of water, contamination from lube oil, or the heavy ends presence as shown by the distillation curve characteristics. These issues elicited from handling and transportation and storage protocols and not exclusively by the FAME blend itself.

The thorough examination of samples showed that a significant example was the case of sample No. 10. An extreme concentration of water at 1,200 mg/kg verified that poor storage conditions can set risks for fuel chemical composition. Specifically, the water presence accelerates the hydrolysis of esters involved into FAME chemical composition, driving corrosive free fatty acids and glycerol, simultaneously promoting the electrochemical corrosion and facilitating a medium for microbial growth (MIC).

A similar finding was in the case of Sample 33 noticing a substandard parameter as flash point measurement. The flash point value measured at (58°C), suggesting risks regarding safety. This finding indicated that it is not an issue concerning fuel degradation FAME presence, but the results demonstrated contamination with lighter fractions of fuel, implying improper blending or cross-contamination during fuel handling and distribution.

The most compelling evidence for infrastructure-driven contamination elicits from Sample 39. In sample 39, significant important levels of metallic components such as Ca, Zn, and P are indicators of contamination from lube oil. This finding verifies that it is not a failure of the fuel chemical composition but an issue regarding the fuel handling system. This failure may be explicit by the poor cleaning of system distribution such as tanks or pipelines, which were earlier used for lube oil. This type of contamination sets operational risks, such as the fouling of injectors, the formation of ash, and the poisoning of the after-treatment exhaust catalysts. In the present study a strong correlation was recorded through the presence of these metallic elements and an increased viscosity (as shown in

Table 1). Also, this finding suggests a practical tool for early investigation and detection since an increased viscosity in stored fuel may imply cross-contamination from lube-oil.

Another significant factor for fuel degradation is environmental exposure. Specifically, the Silicon and Sodium presence into samples 21 and 23 underscored this influence. These types of compounds are not components into fuel composition but pollutants coming from the environment, implying improper storage conditions highlighting that storage tanks are poorly sealed against seawater and dust particles. This finding is associated with problems in infrastructure and issues concerning the maintenance protocols.

The sample No.38 shown a visible sediment indicating a serious stability issue. The Sediment formation suggests a long-term oxidation which is promoted by the trace metals presence or the growth of microbes. This finding verifies that storage management is another critical parameter. This sediment is the consequence of long-term storage conditions, having fuel without stabilizers or biocides.

Overall, the current study suggests that the risks of fuel degradation and contamination are managed not by eliminating the biodiesel-FAME concentration, but by controlling the environment during storage conditions and by ensuring the compatibility of fuel with the infrastructure. Thus, the FAME content of 7% v/v is not the primary cause of the problems which are encountered. Concentrations of metallic compounds higher than > 0.2mg/kg, according to the car manufacturers’ investigation, leads to engine damage such as injector fouling, soot formation. All the marine samples investigated are depicted in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 regarding the metallic compounds content in their chemical composition. Cornering

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 are represented by the figures showing contaminants’ concentration higher than 0,2 mg/kg in each sample examined.