1. Introduction

Engine oil is indispensable for sustaining the operation of an internal combustion engine. Its functions extend far beyond simple lubrication, encompassing the reduction of friction and wear between moving parts, efficient dissipation of heat generated during combustion, prevention of corrosive processes and the suspension of contaminants to maintain engine cleanliness [

1]. The sustained integrity of these critical functions is paramount for ensuring effective engine operation, prolonging reliability and maximizing the overall lifespan of the machinery.

Despite its vital role in many biological and industrial processes, water stands as one of the most profoundly destructive contaminants in engine lubrication systems. Its detrimental impact is often considered second only to that of abrasive particulate matter [

2]. Even at relatively low concentrations, such as 0.1% to 0.2% (equivalent to 1000-2000 ppm), water can significantly compromise the intended purpose and overall effectiveness of lubricants, frequently leading to mechanical asset failure or a marked reduction in operational efficiency. This danger is often underestimated because the initial, dissolved phase of water contamination is not readily detectable through visual inspection [

2]. Thus, water can accumulate to harmful levels before any visible milky appearance, indicative of emulsified water, signals a severe issue. Further complicating visual detection is the observation that used engine oils possess a greater capacity to hold dissolved water – up to three to four times more than fresh oil. This progressive degradation can effectively mask the early signs of contamination, allowing the problem to advance unnoticed [

3].

Water can infiltrate engine oil through a variety of mechanisms, ranging from inherent operational processes to system failures and, at times, human error.

Table 1 illustrates these contamination mechanisms.

States of Water in Engine Oil

Water does not exist as a singular entity within engine oil; rather, it manifests in three distinct phases, each possessing varying degrees of visibility and detrimental impact on the lubricant and engine.

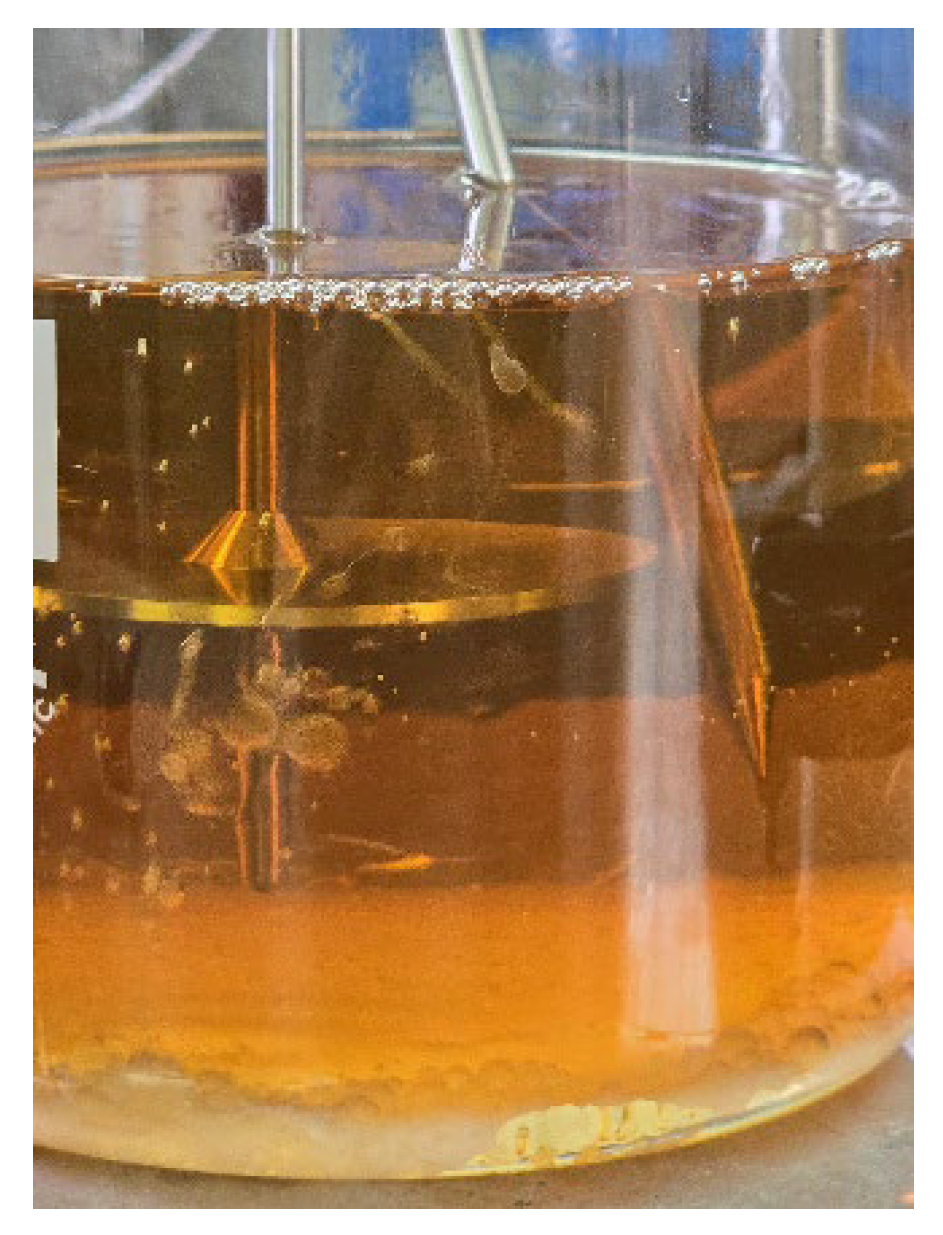

Figure 1.

Appearance of the emulsion formed by water in engine oil.

Figure 1.

Appearance of the emulsion formed by water in engine oil.

Dissolved water represents the initial phase of water contamination, where individual water molecules are molecularly dispersed throughout the oil, akin to humidity in the atmosphere. In this state, water is entirely invisible to the naked eye. The maximum amount of water an oil can hold in a dissolved state, known as its saturation point, is influenced by factors such as the specific oil type (e.g., mineral versus synthetic formulations), temperature, and ambient atmospheric pressure. For many industrial oils, this dissolved capacity can range from 200 to 600 ppm (0.02% to 0.06%) [

3]. Notably, aged oils often exhibit a significantly increased capacity to hold dissolved water, sometimes three to four times more than new oil. Despite its invisibility, dissolved water is inherently harmful, as it actively accelerates the oxidation process of the oil and contributes to the depletion of critical additives [

5].

When water exceeds the oil’s saturation point, it forms microscopic droplets that create a stable emulsion, giving the oil a cloudy, milkshake-like appearance [

4]. Emulsified water is more harmful than dissolved water due to its physical presence and higher reactivity. Engine oils contain dispersants to suspend soot, but these also stabilize water emulsions [

3], making separation more difficult than in industrial lubricants formulated with demulsifiers. As a result, gravity separation is often ineffective, and removal typically relies on engine heat or more aggressive methods [

6].

If the water concentration continues to increase beyond the emulsified state, the water will physically separate from the oil and, due to its higher density (for most mineral oils and PAO synthetics), settle as a distinct layer at the bottom of the sump or reservoir [

5]. The presence of free water signifies a severe contamination issue that has overwhelmed the oil's capacity to hold water in solution or emulsion. Free water is highly damaging, leading to direct corrosion of metallic components and creating an environment conducive to microbial proliferation [

7]. While free water is visually apparent and often drainable, its presence signals a critical need for immediate intervention.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the detrimental effects of water contamination in engine oil, with a particular focus on its influence on oil properties and engine performance. This study explores the origins, physical states and complex effects of water contamination on the chemical and physical characteristics of engine oil. Furthermore, an experimental analysis was conducted to assess the influence of water content on the viscosity of used engine oil.

2. Results

The following results quantify how incremental water additions (0-10%) reshape the temperature-dependent viscosity of used diesel, gasoline, and LPG engine oils, and document the onset of emulsification and early vaporization across 10-100 °C. The data obtained, together with those from the technical data sheets of the new oils, are presented in

Table 2.

After collecting the experimental data, they were processed, resulting in a series of graphs, as follows:

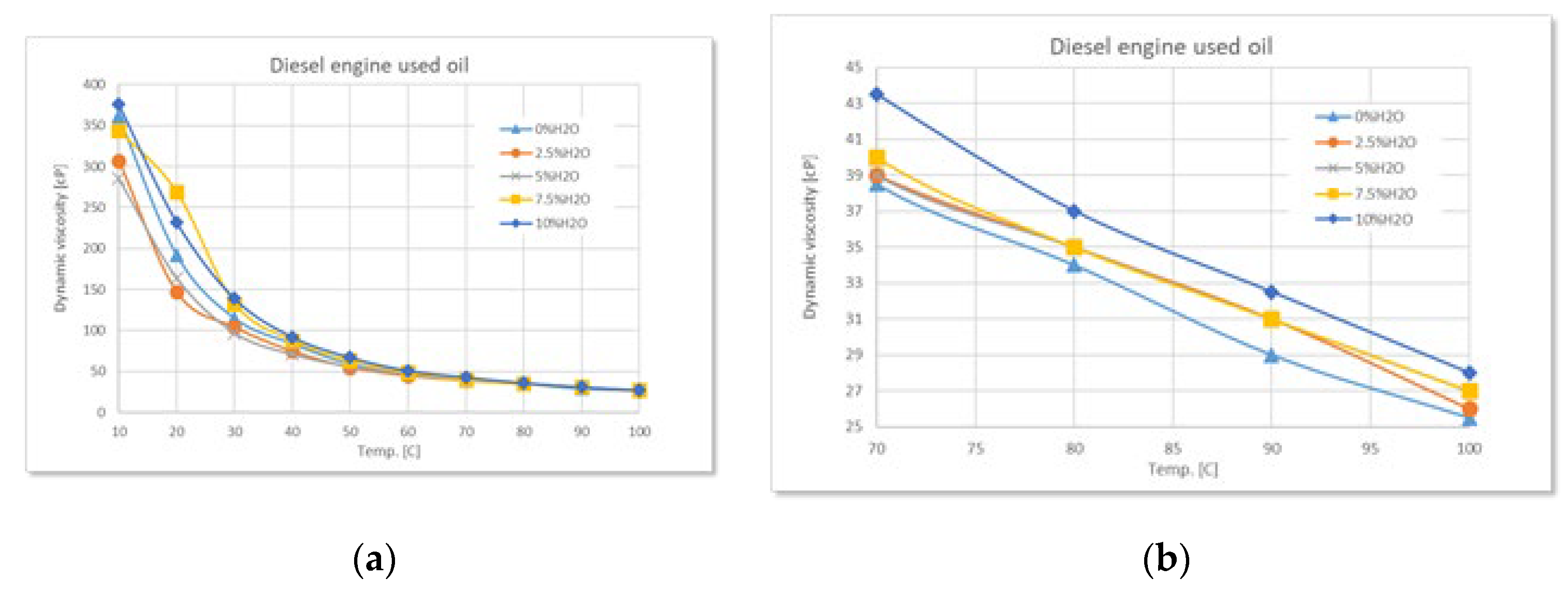

Figure 2.

Variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at different degrees of water contamination for used diesel engine oil: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 2.

Variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at different degrees of water contamination for used diesel engine oil: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

In the case of used oil from a diesel engine, water contamination has a noticeable effect on the increase of dynamic viscosity, especially at low temperatures (below 50°C). At water concentrations of 7.5% and 10%, the viscosity is significantly higher compared to uncontaminated oil. At high temperatures, the differences between viscosity curves tend to reduce.

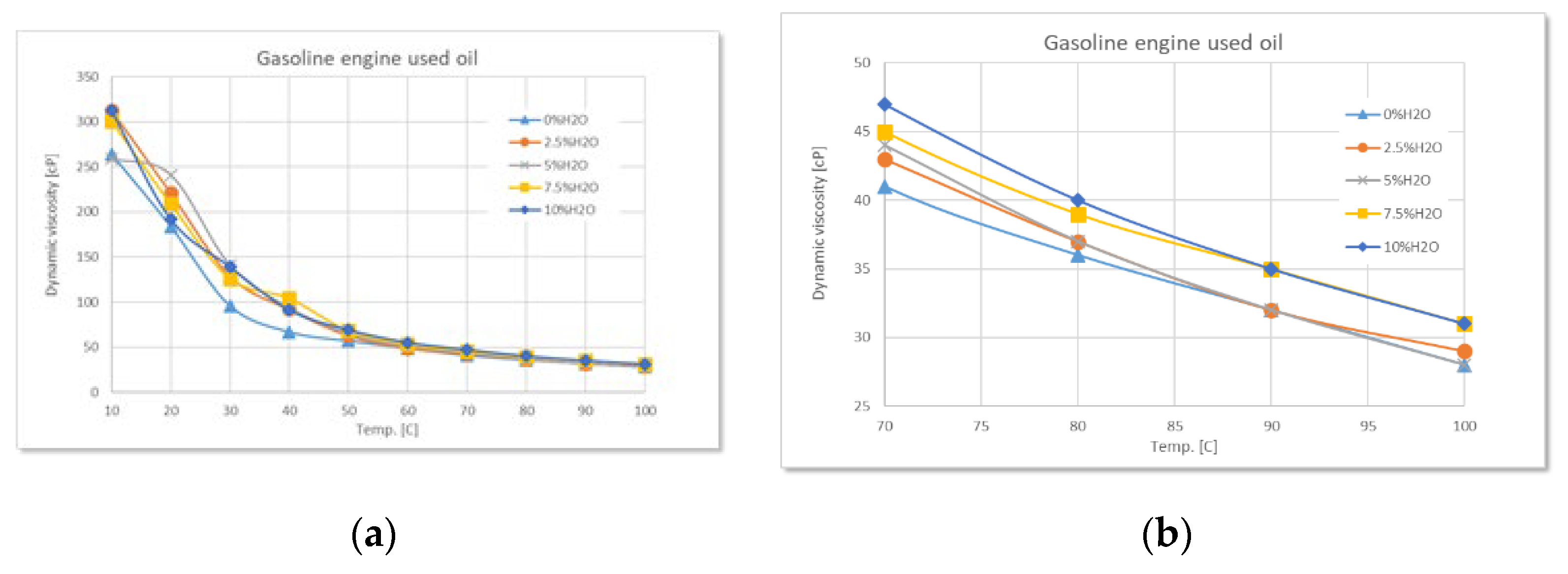

Figure 3.

Variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at different degrees of water contamination for used gasoline engine oil: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 3.

Variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at different degrees of water contamination for used gasoline engine oil: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Used oil from gasoline engines exhibits a similar, but less pronounced behavior. Although water contamination leads to an increase in viscosity at low temperatures, the magnitude of this effect is lower than in the case of diesel engines. This difference can be explained by a lower content of solid residues and oxidation products in the oil from gasoline-powered engines.

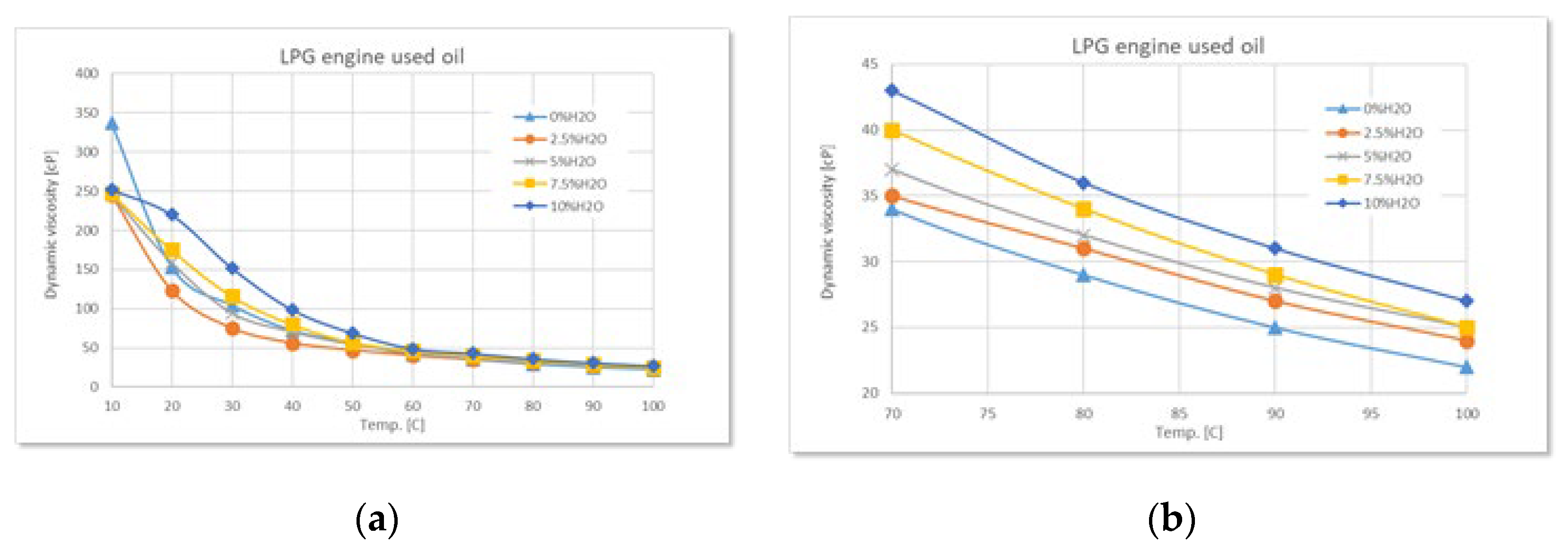

Figure 4.

Variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at different degrees of water contamination for used LPG engine oil: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 4.

Variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at different degrees of water contamination for used LPG engine oil: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

In the case of the LPG engine, the influence of water contamination is lower compared to the other two engine types, and the viscosity remains relatively constant at high temperatures. This suggests a “cleaner” chemical composition of the oil residues, which interact less with water.

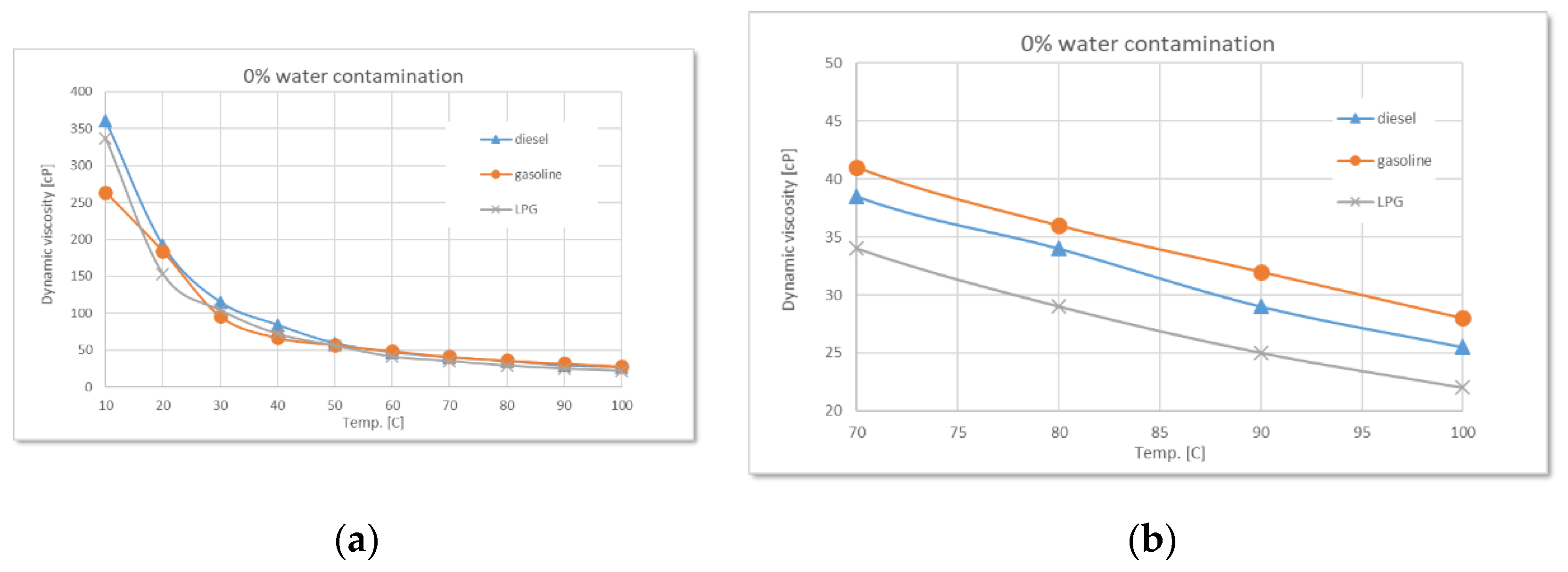

Figure 5.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 0% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 5.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 0% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

The comparative analysis of uncontaminated oils (0% water) revealed that used diesel engine oil has the highest viscosity, followed by gasoline engine oil, while LPG engine oil shows the lowest values. This reflects the differences in combustion regime, operating temperature, and the level of specific contaminants associated with each engine type.

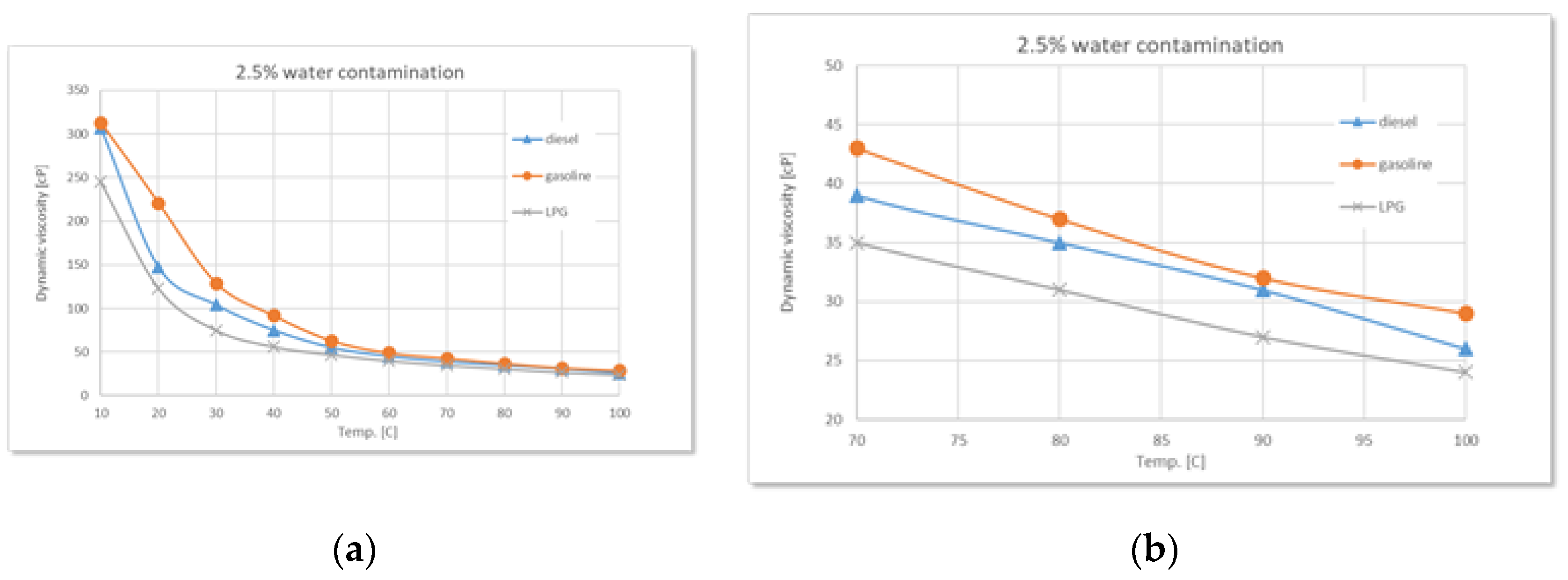

Figure 6.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 2.5% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 6.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 2.5% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

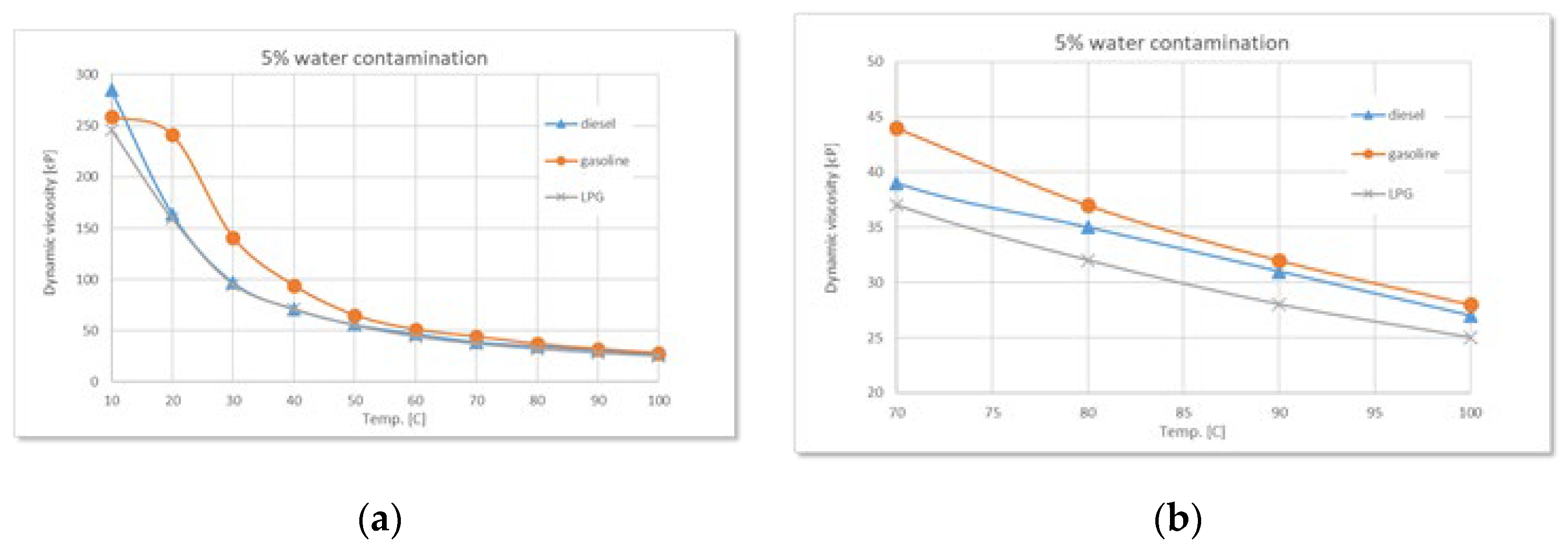

Figure 7.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 5% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 7.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 5% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

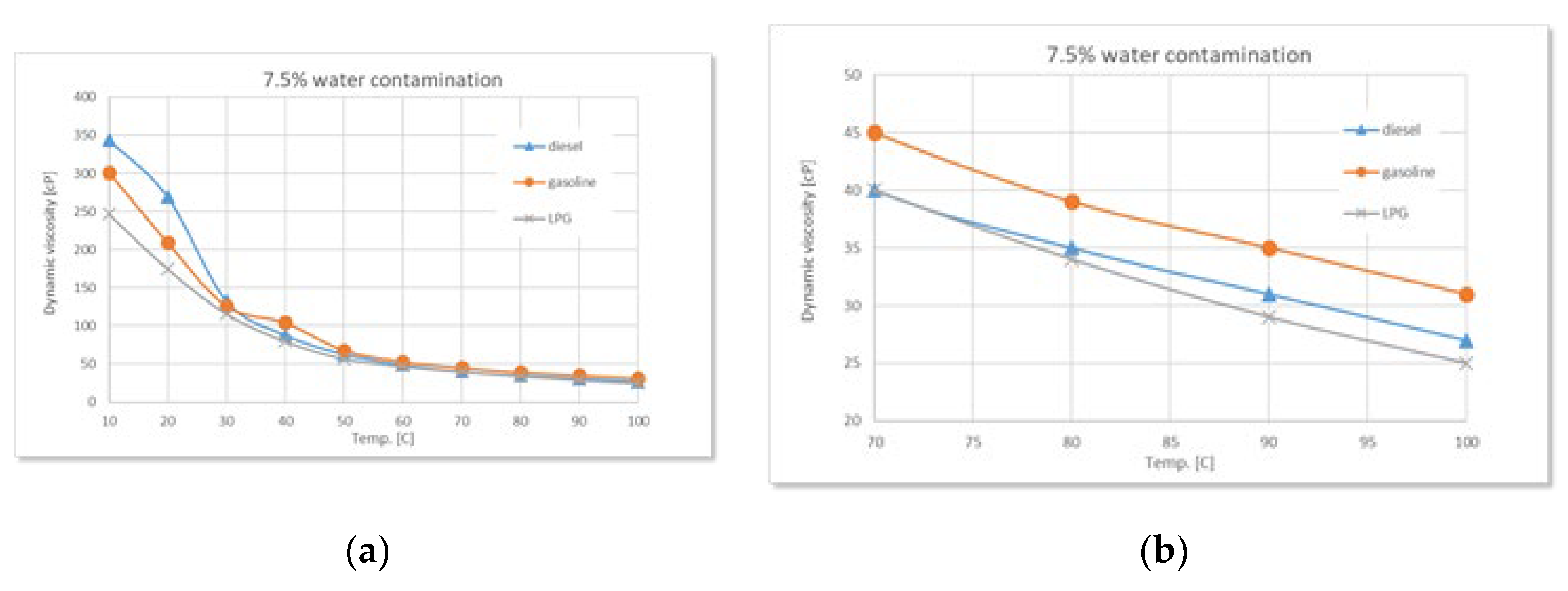

Figure 8.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 7.5% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 8.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 7.5% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

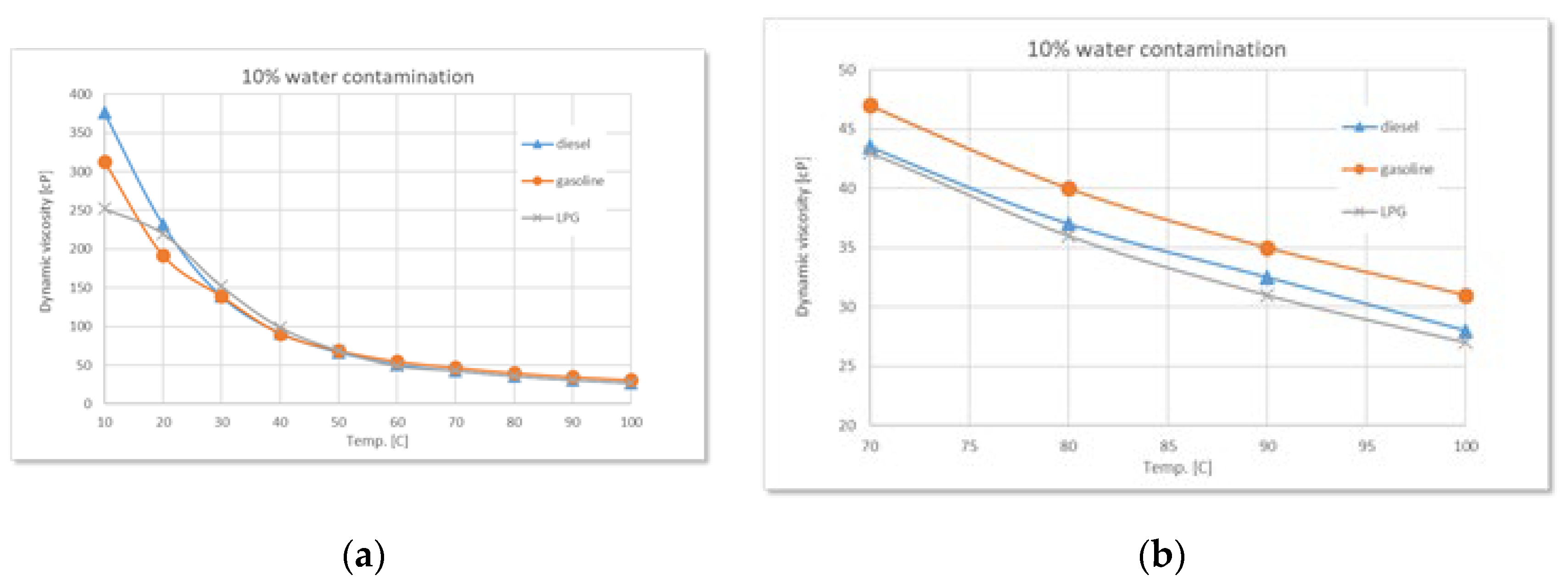

Figure 9.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 10% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

Figure 9.

Comparative variation of dynamic viscosity with temperature at 10% water contamination: (a) full range-temperature; (b) detailed temperature.

3. Discussion

Previous studies show that water contamination fundamentally alters the physical and chemical properties of engine oil, severely compromising its ability to perform its essential functions. Thus, the presence of water significantly diminishes the oil's overall effectiveness and lubricity. Water, with a viscosity of approximately 1 cSt, is vastly less viscous than engine oil. When water is present between rubbing surfaces, it effectively dilutes the oil, leading to a reduction in its viscosity and film strength. This compromised film results in increased metal-to-metal contact and improper lubrication [

11]. For example, a water contamination level as low as 1% can reduce the life expectancy of a journal bearing by as much as 90% [

12]. Even a mere 0.4% water content can cause the oil to become pasty and exhibit thixotropic behavior, almost solidifying at ambient temperatures, indicating a severe alteration in its physical properties.

This presents a complex scenario regarding viscosity changes. While initial water dilution may reduce effective viscosity at lubrication points, as stable emulsions form, the apparent bulk viscosity of the oil can dramatically increase [

2]. This leads to a "thixotropic" behavior or a "black mayonnaise" consistency. This dual effect means that water contamination can simultaneously lead to insufficient film strength (due to dilution at critical contact points) and lubricant starvation (due to overall thickening and restricted flow through passages and filters) [

13].

Water significantly accelerates the oxidation of the base oil, a process that is particularly exacerbated in the presence of heat and catalytic metals such as copper, lead, and tin [

7]. This can increase the rate of oxidation progression by a factor of ten, leading to premature aging of the oil. Oxidation is a primary driver of oil aging, resulting in profound changes to its physical and chemical characteristics.

Furthermore, water compromises the oil's inherent thermal stability. High operating temperatures can degrade hydrodynamic lubrication properties and accelerate both wear and oxidation. The presence of water intensifies these detrimental effects. This creates a destructive cycle: water promotes oxidation, which in turn generates organic acids and releases wear metals [

14]. These wear metals then act as catalysts, further accelerating oxidation in the presence of water, leading to the formation of more acids and increased wear. This positive feedback loop means that even initial contamination can rapidly escalate into severe degradation, underscoring the critical importance of early detection and intervention to disrupt this cascading destructive process.

Water directly diminishes the effectiveness of the intricate additive package formulated into engine oil. Many critical additives, including anti-wear agents, extreme-pressure additives, phenolic antioxidants, detergents, dispersants, and rust inhibitors, are highly susceptible to chemical degradation via hydrolysis or can be physically washed away by excessive moisture. The depletion of these vital additives compromises the oil's engineered protective properties, leading to an increase in wear, corrosion, and the accelerated formation of sludge [

7]. The implication is that even if the base oil is not immediately destroyed, the functional performance of the lubricant is severely degraded, leading to premature oil changes and increased operational costs.

The presence of water in engine oil is not merely a physical dilution phenomenon; it actively participates in and catalyzes complex chemical reactions that lead to severe and progressive degradation of the lubricant.

Table 3 illustrates the interconnectedness of different degradation mechanisms.

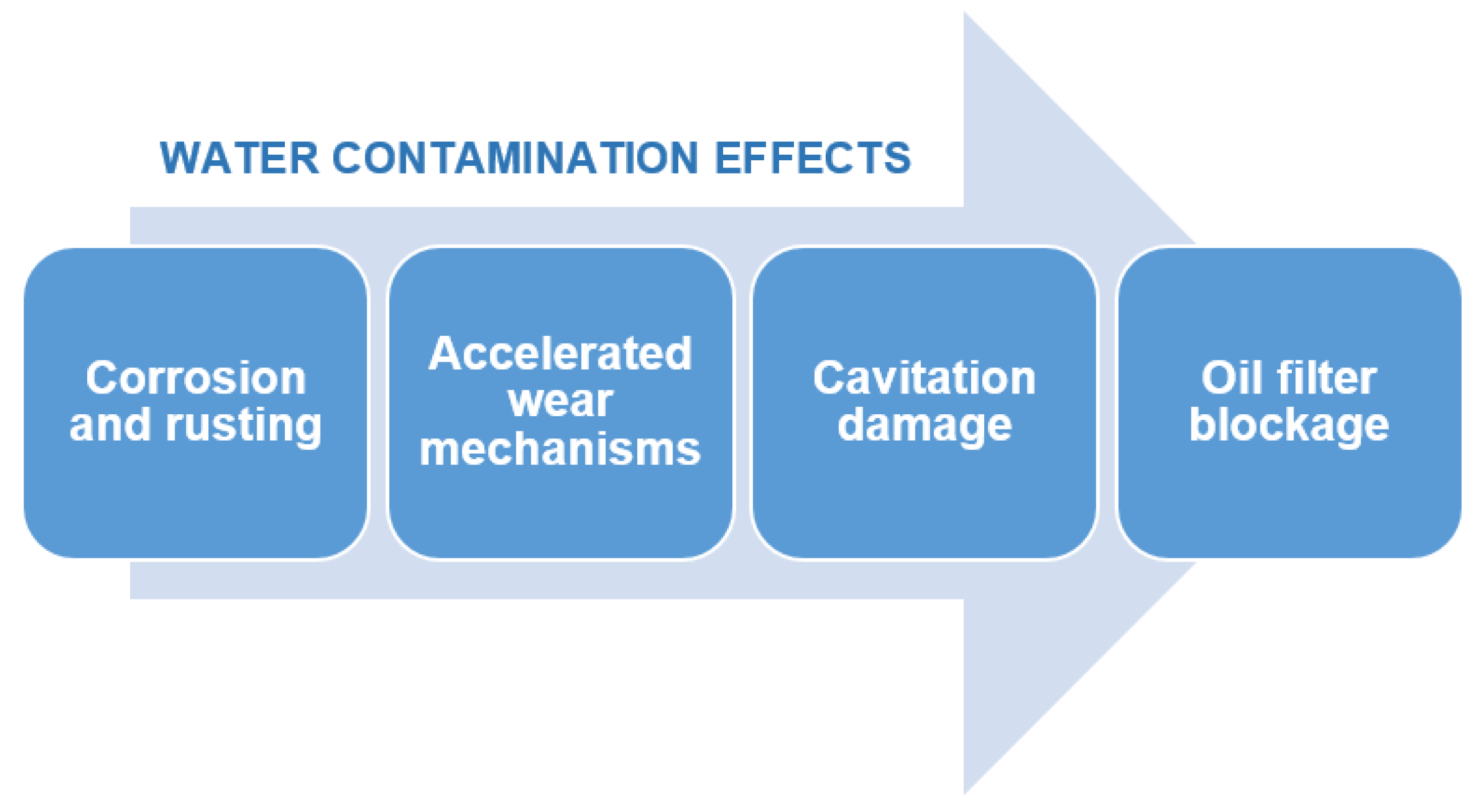

The impact of these degradation mechanisms is illustrated in

Figure 10.

It has been observed that water rarely acts in isolation within engine oil. Its presence frequently exacerbates the detrimental effects of other common contaminants, leading to complex and often accelerated synergistic degradation pathways.

Fuel dilution occurs when unburned fuel passes the piston rings and mixes with engine oil, reducing its viscosity and protective performance. Although the combined effect of water and fuel dilution hasn’t been precisely quantified, both contaminants individually weaken oil viscosity and film strength. When present together, they likely compound these effects, drastically lowering the oil’s load-bearing capacity and increasing wear. This "double whammy" effect severely impairs lubrication, promoting boundary lubrication and harmful metal-to-metal contact [

16].

Soot from diesel combustion enters engine oil through blowby, increasing viscosity and contributing to sludge formation. While dispersants in the oil are designed to manage soot, high soot levels combined with contaminants like water and glycol can quickly degrade dispersant effectiveness [

17]. Water, in particular, directly weakens dispersants, allowing soot particles to agglomerate into larger, abrasive clusters. This results in increased abrasive wear, faster sludge formation, and clogged filters, highlighting water’s indirect but significant role in worsening the effects of other oil contaminants [

17].

Coolant contamination, usually caused by issues like a blown head gasket, introduces both glycol and water into engine oil, resulting in several severe effects [

4]. Glycol drastically thickens the oil, forming a gel-like substance known as "black mayonnaise," which restricts oil flow and causes lubricant starvation. It also creates a highly acidic environment by forming corrosive acids such as glycolic and formic acid, leading to rapid metal corrosion, particularly on copper components. Additionally, glycol undermines the oil's additive package and forms abrasive "oil balls" that cause surface erosion and fatigue. It also contributes to premature filter clogging [

13]. Thus, glycol represents one of the most damaging oil contaminants and a serious threat to engine health.

During the experiments performed, as the water content increases (2.5%, 5%, 7.5%, 10%), a clear trend of rising dynamic viscosity is observed for all types of used oil, with the highest sensitivity in the case of diesel. At 2.5% water, the effect is still moderate, but at higher concentrations the differences become evident. Diesel engine oil remains the most sensitive to contamination, followed by gasoline, and finally LPG.

The experimental data confirm the theoretical considerations mentioned above regarding the states of water, regardless of the type of used oil. Thus, controlled water contamination involves three stages:

Stage 1 - in the low-temperature range, a sharp decrease in dynamic viscosity is observed with increasing temperature, regardless of the degree of contamination. This is due to the phenomenon of relative slippage between the oil and water layers.

Stage 2 - as the temperature increases, gradual absorption of water into the oil occurs, accompanied by a slight increase in viscosity with higher water contamination levels.

Stage 3 - finally, a phenomenon of oil oversaturation with water takes place, leading to the formation of colloidal structures or stable emulsions that interfere with the free flow of oil and alter its rheological properties - an irreversible process.

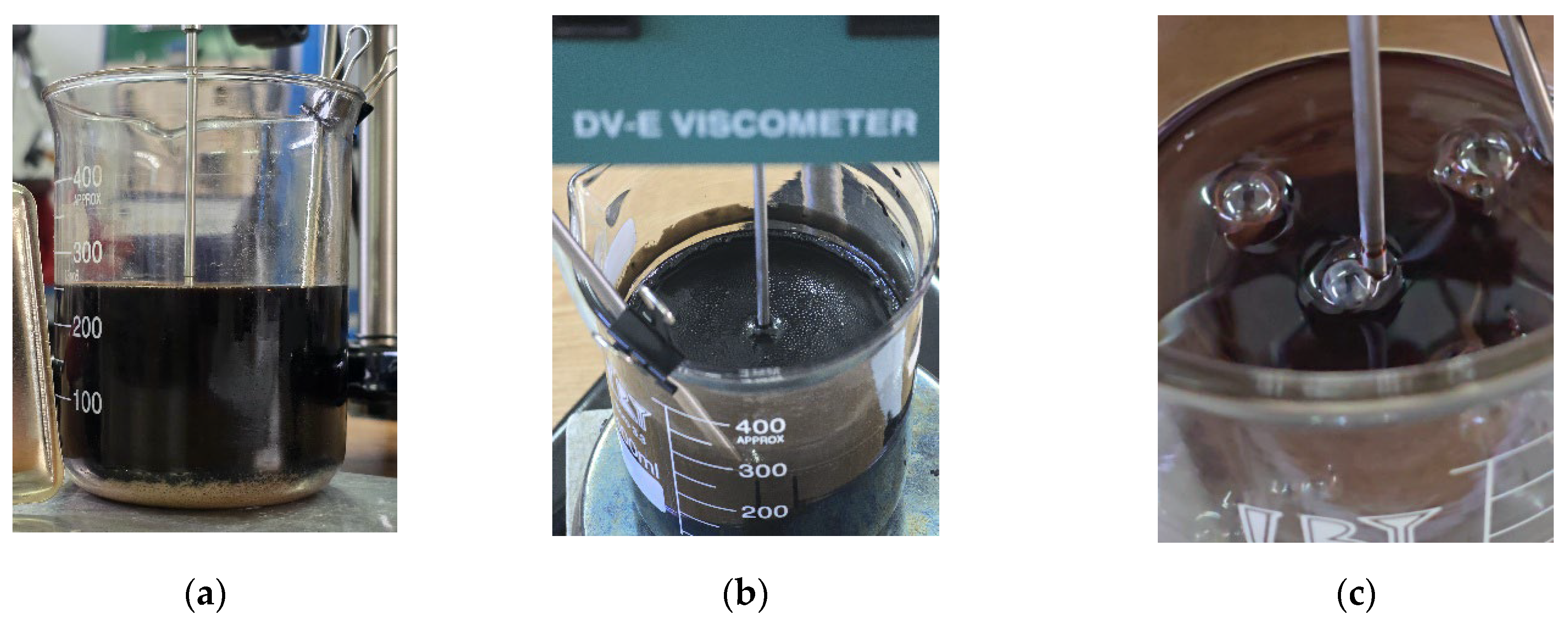

Around 100°C, the viscosity differences between samples with different levels of contamination become increasingly smaller, while the amount of sedimented emulsion (

Figure 11 a) increases with the degree of water contamination. Overall, the detailed graphs show that, regardless of the type of used oil, dynamic viscosity increases with higher levels of water contamination, a phenomenon clearly caused by emulsion formation.

Additionally, as the temperature rises, the onset of water vapor bubble formation is observed at around 80°C on the free surface of the oil - bubbles resulting from the initial boiling of water (

Figure 11 b). The higher the level of water contamination, the greater the number of these bubbles. As the temperature continues to rise, the water vaporization process intensifies. Near 100°C, large-diameter bubbles begin to appear, caused by the boiling of water from the sedimented layer (

Figure 11 c).

4. Materials and Methods

In order to properly understand how water contamination influences the viscosity of used engine oil, there has been conducted an experimental investigation, exploring the mechanisms by which water disrupts the oil's rheological behavior. In this regard, a controlled water contamination of used engine oil was carried out, coming from 3 engines: gasoline, diesel and LPG, with the following percentages of water: 0%, 2.5%, 5%, 7.5% and 10%.

The equipment used consists of a Brookfield DV-E viscometer, with the help of which the values of dynamic viscosities [cP] were determined at various temperatures. A thermometer was used to know the temperature level of the oil, which was heated on an electric hot plate (

Figure 12). The temperature ranges within which the experimental data were taken is from 10°C increasing towards 100°C.

Thus, from the temperature of 10°C, the measurements were started, at increasing temperatures, from 10 to 10°C until the temperature of 100°C was reached. Measurements were made by placing the Berzelius beaker on the hot plate on the viscometer which was turned on and set.

Measurements were made on the dynamic viscosity of used engine oil before water contamination. The engines that used the oils studied are: Renault 1.5 dCi, 110 HP (diesel, 2016), Renault 1.6 16V, 110 HP (gasoline, 2014), Renault 1.6 + LPG, 102 HP (LPG, 2010). The used oils were collected after approximately 15 000 km of driving.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, from a theoretical standpoint, the study has illustrated how water infiltrates engine oil via multiple pathways, ranging from condensation due to cold engine operation to serious mechanical failures such as head gasket leaks. More importantly, water can exist in three distinct states: dissolved, emulsified, and free, each contributing in unique and increasingly severe ways to the degradation of the lubricant. The chemical and physical consequences include not only a decline in viscosity performance but also additive depletion, accelerated oxidation, and formation of sludge and varnish, culminating in increased wear and possible engine failure.

The experimental part of the study offers a clear view of how water contamination alters the rheological behavior of used engine oil. By gradually adding known amounts of water (ranging from 0% to 10%) to oil samples taken from diesel, gasoline, and LPG engines, and measuring their viscosity between 10°C and 100°C, the study outlines how temperature and water content interact to change oil flow properties. At lower temperatures, especially below 50°C, water contamination causes a significant increase in viscosity, more prominently in diesel engine oil. This is due to the formation of emulsions and the development of gel-like structures that resist flow. As the temperature approaches 100°C, viscosity values across all samples begin to align, due to water evaporation. However, this does not fully restore the oil’s original structure, as the chemical alterations caused by emulsification remain.

Among the tested oils, diesel showed the greatest sensitivity to water, likely because of a higher content of soot and oxidation byproducts that react more intensely with moisture. Gasoline oil followed a similar, but less marked pattern, while LPG oil exhibited the least change, suggesting a cleaner degradation profile and reduced interaction with water. The results also confirm a stepwise contamination process: initial thinning of the oil, followed by emulsion formation and gradual thickening, and ultimately the development of stable colloidal structures that can permanently alter the oil’s behavior and reduce its performance.

The results obtained highlight the need for strict control of water contamination of engine oil in service, especially in the case of diesel engines, where the effects on rheological properties can be considerable. Maintaining viscosity within the optimal range is essential for the correct functioning of the lubrication system and for preventing accelerated wear of mechanical components.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.R. and I.I.; methodology, S.A.R.; investigation, D.M.A.; resources, D.M.A.; data curation, S.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A.R.; visualization, D.M.A.; supervision, I.I. and S.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCV |

Positive Crankcase Ventilation |

| PAO |

Poly Alpha Olefin |

| LPG |

Liquefied Petroleum Gas |

| TAN |

Total Acid Number |

References

- Bastiampillai, N. Statistical Analysis and Modelling of Engine Oil Degradation; Umeå University: Umeå, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Xing, S. Impact of oil-water emulsions on lubrication performance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harika, E.; Bouyer, J.; Fillon, M.; Hélène, M. Effects of water contamination of lubricants on hydrodynamic lubrication: Rheological and thermal modeling. J. Tribol. 2013, 135, 041707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodtke, M.; Frost, J.; Litwin, W. Effect of water contamination of an environmentally acceptable lubricant based on synthetic esters on the wear and hydrodynamic properties of stern tube bearing. Tribol. Int. 2025, 205, 110562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkner, J.; Baese, M.; Lebel, A.; Pflaum, H.; Voelkel, K.; Pointner-Gabriel, L.; Besser, C.; Schneider, T.; Stahl, K. Influence of water contamination, iron particles, and energy input on the NVH behavior of wet clutches. Lubricants 2023, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armioni, D.M.; Rațiu, S.A.; Gidali, A. Study on the determination of the degree of decrease in the dielectricity of engine oils following water contamination. Ingineria Automobilului 2024, 72, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, K.; Wang, L. The effect of water content on engine oil monitoring based on physical and chemical indicators. Sensors 2024, 24, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ELF Evolution FULL-TECH FE 5W-30. Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.diesel-electric.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/TDS_ELF_EVOLUTION-FULL-TECH-FE-5W-30_BUZ_202202_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- ELF Evolution 900 SXR 5W-40. Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.diesel-electric.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/TDS_ELF_EVOLUTION-900-SXR-5W-40_BUV_202202_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- ELF Evolution 300 CNG 20W-50. Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://total-cdn-lmdb.afineo.io/tdsV2/TDS_ELF_EVOLUTION-300-CNG-20W-50_TQ7_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Rațiu, S.A.; Alexa, V.; Josan, A.; Cioată, V.G.; Kiss, I. Study of temperature dependent viscosity of different types of engine used oils. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1426, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Doll, G.L. Effects of water contamination on micropitting and rolling contact fatigue of bearing steels. J. Tribol. 2023, 145, 011501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmunem, O.M.; Abdul-Munaim, A.M.; Aller, M.M.; Preu, S.; Watson, D.G. THz-TDS for detecting glycol contamination in engine oil. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewole, B.Z.; Olojede, J.O.; Owolabi, H.A.; Obisesan, O.R. Characterization and suitability of reclaimed automotive lubricating oils reprocessed by solvent extraction technology. Recycling 2019, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.A. al Sheikh; Salehi, F.M.; Farooq, U.; Morina, A. Additives depletion by water contamination and its influences on engine oil performance. Tribol. Lett. 2024, 72, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.K.A.; Ezzat, F.M.H.; Abd El-Gawwad, K.A.; Salem, M.M.M. Effect of lubricant contaminants on tribological characteristics during boundary lubrication reciprocating sliding. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.04448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agocs, A.; Frauscher, M.; Ristic, A.; Dörr, N. Impact of soot on internal combustion engine lubrication—oil condition monitoring, tribological properties, and surface chemistry. Lubricants 2024, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).