Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Equipment

2.2. Experimental Materials

2.3. Experimental Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Physical and Chemical Analysis of the Lubricating Oil

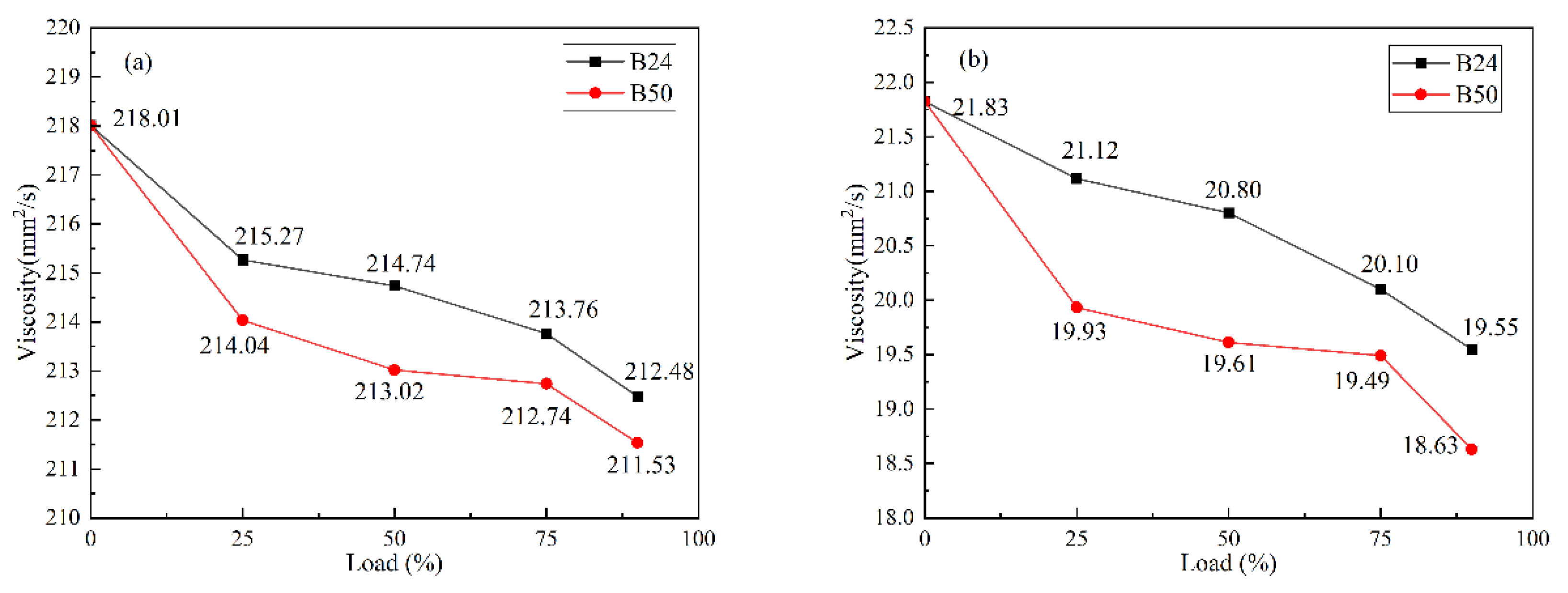

3.1.1. Kinematic Viscosity

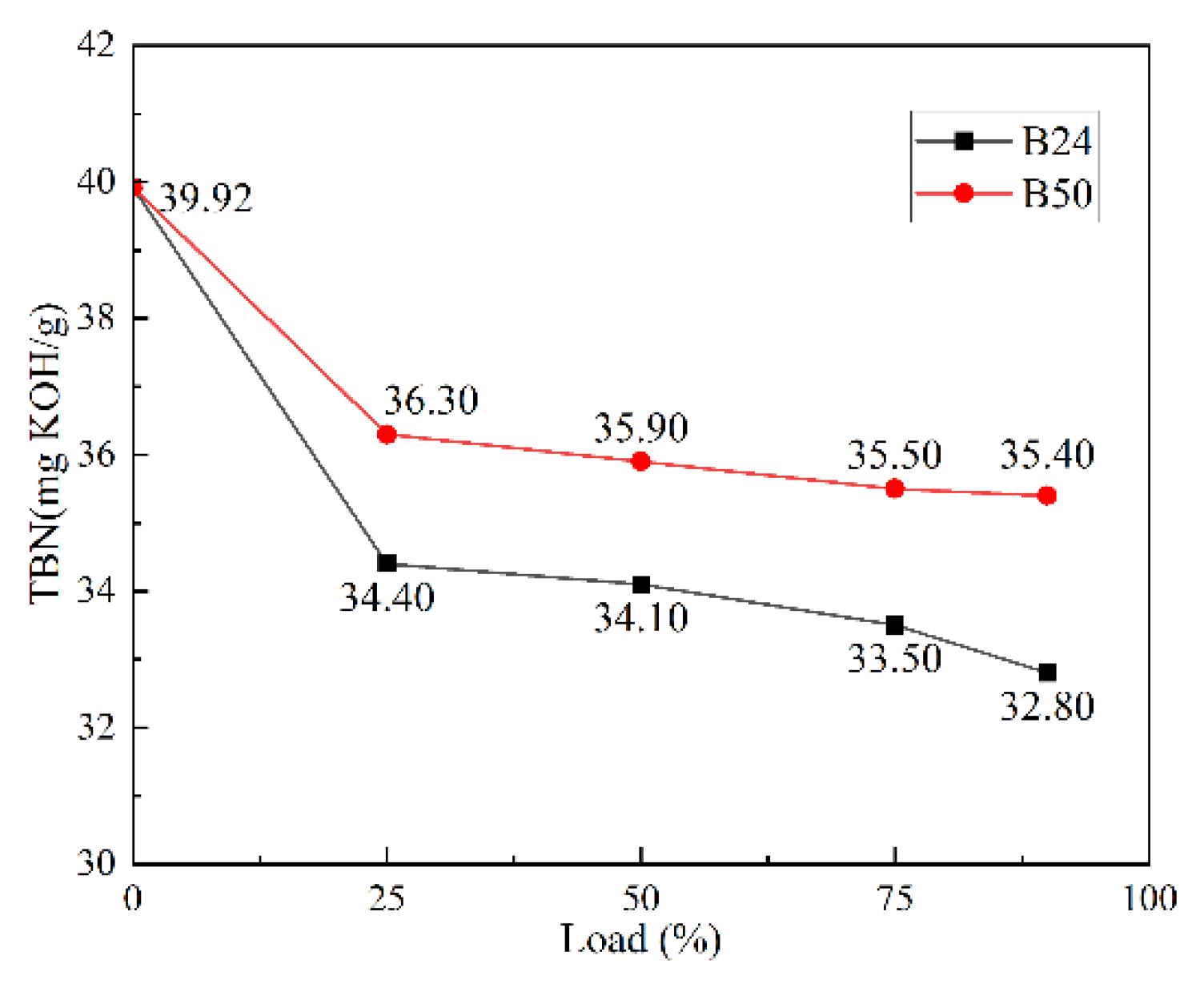

3.1.2. Total Base Number

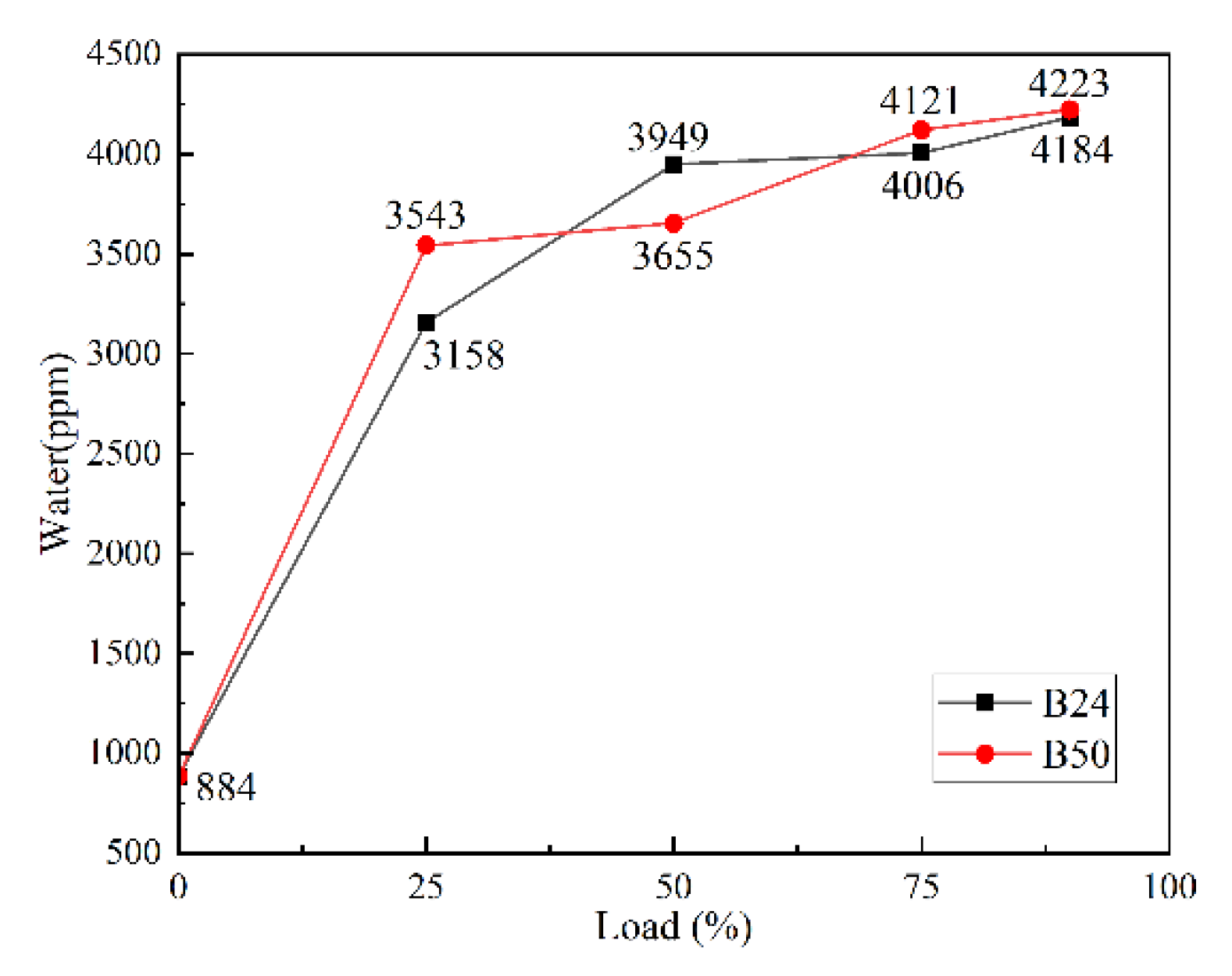

3.1.3. Water Content

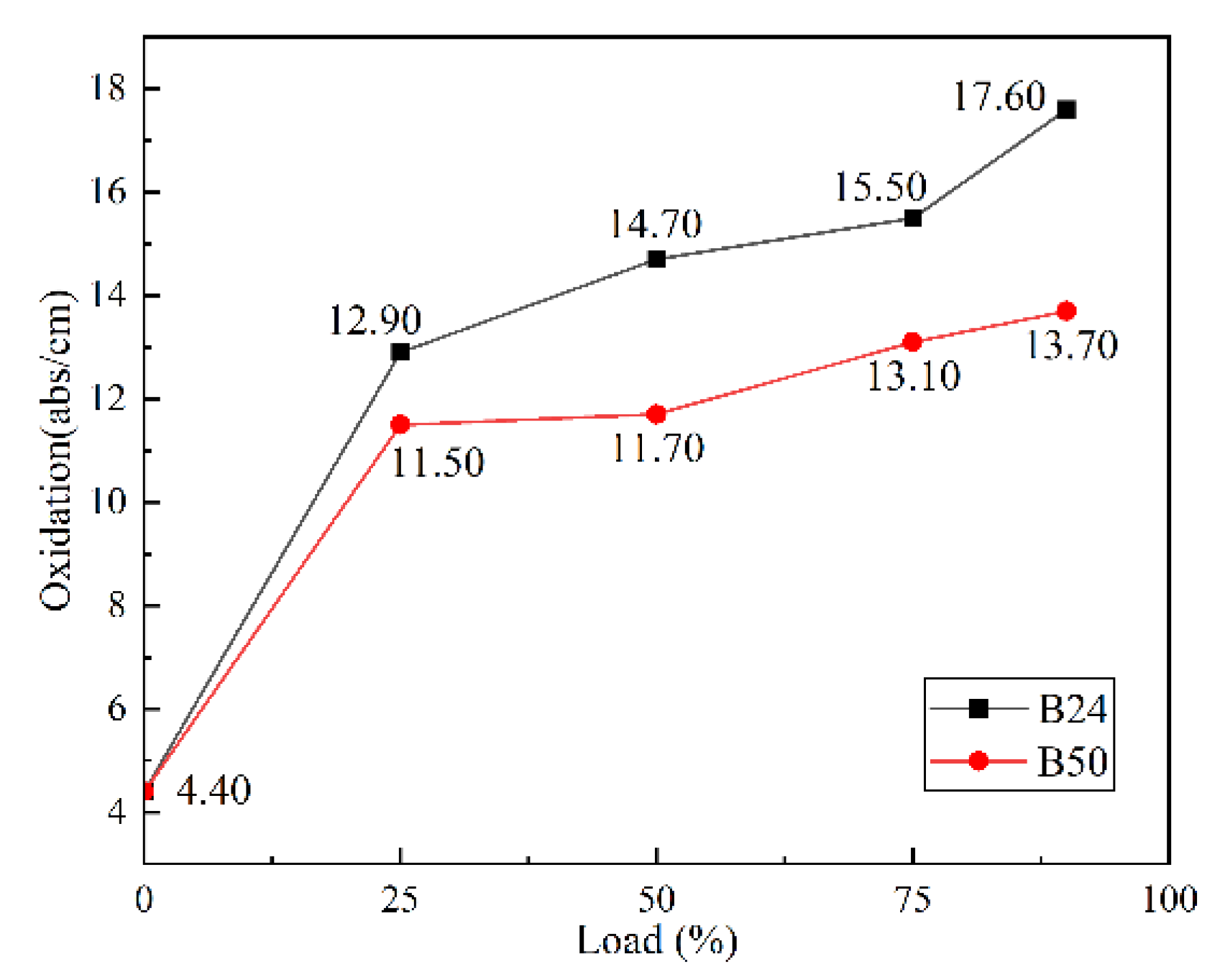

3.1.4. Oxidatition

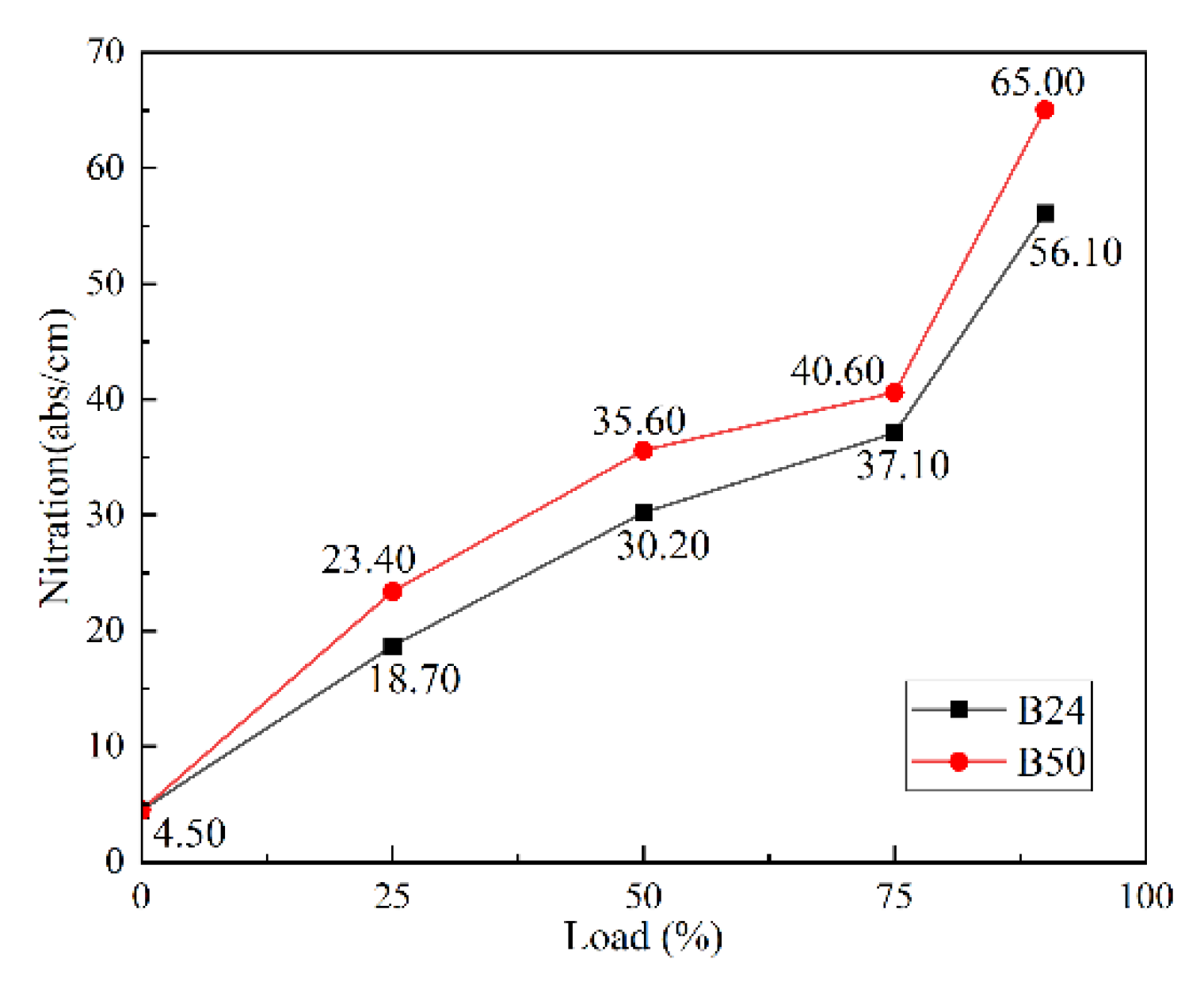

3.1.5. Nitration

3.2. Wear Element Analysis of the Lubricating Oil

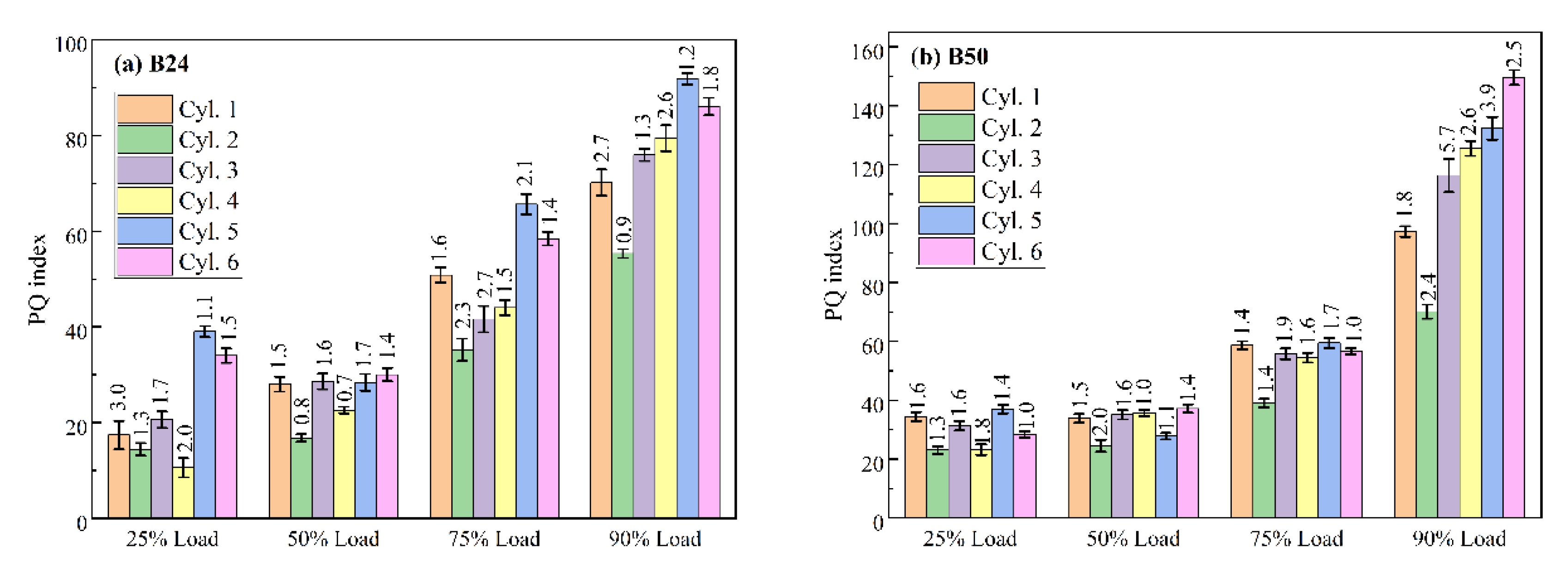

3.2.1. PQ Index

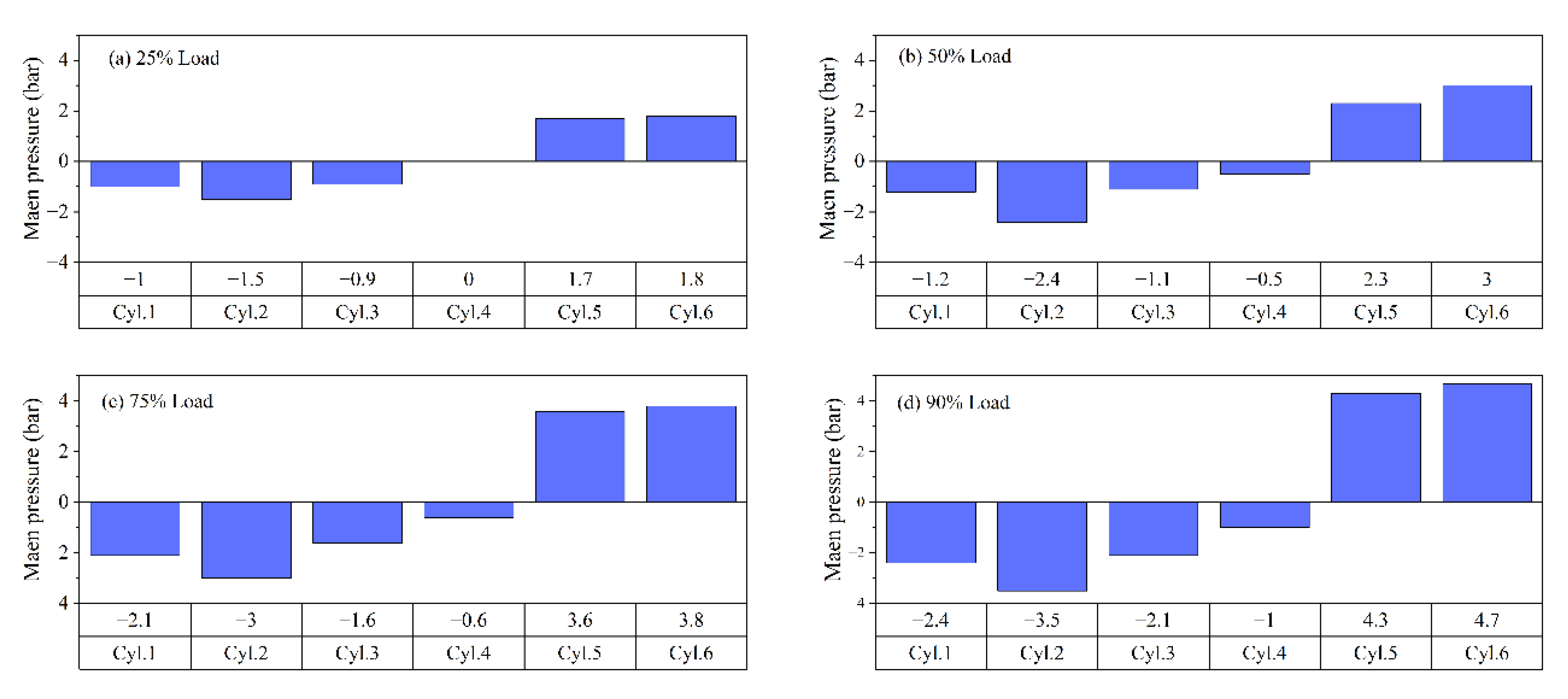

3.2.2. Spectral Analysis

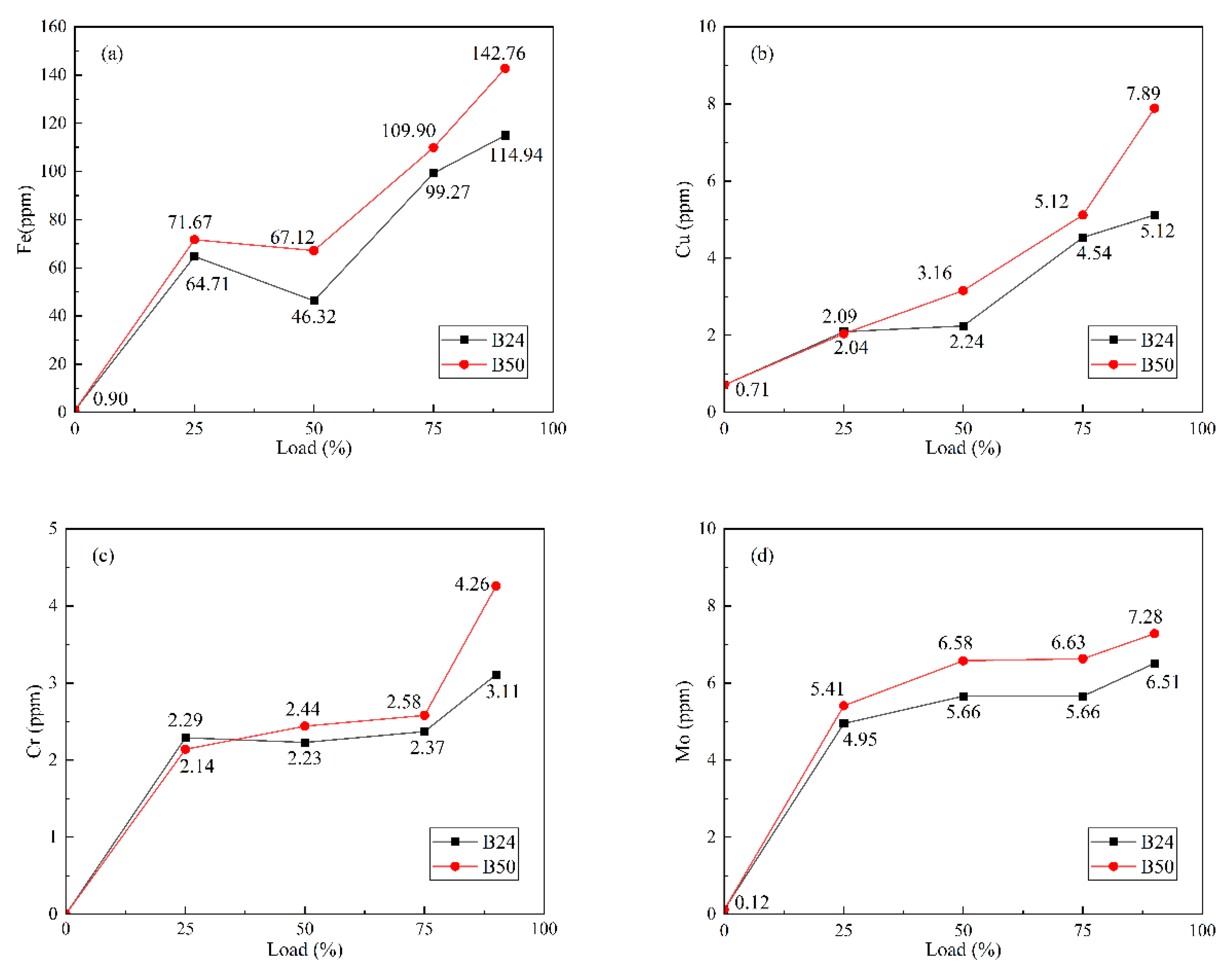

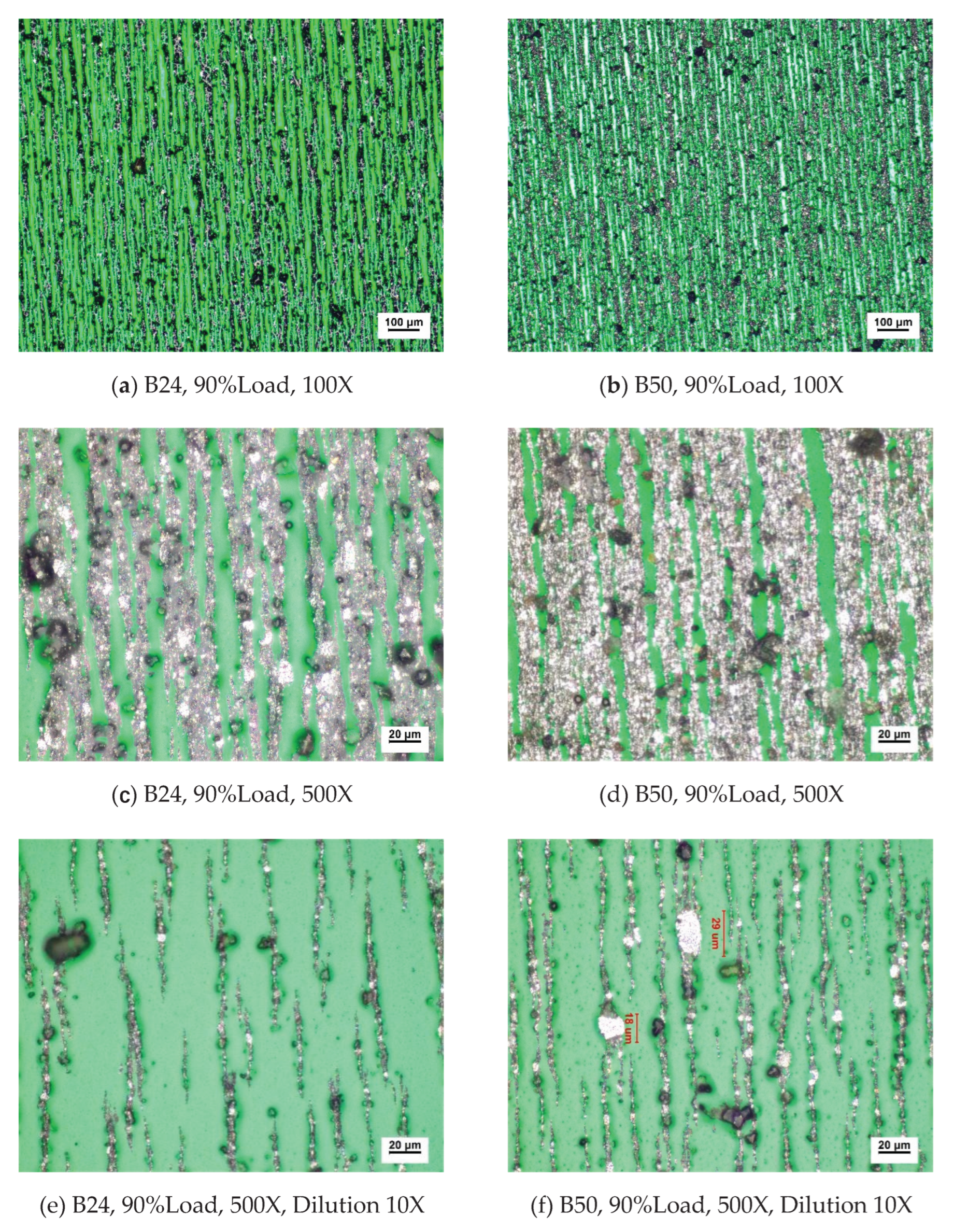

3.3. Ferrography Analysis of the Lubricating Oil

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2023 IMO strategy on reduction of ghg emissions from ships. Annex 15 Resolution MEPC. 377(80) (adopted on 7 July 2023).

- Lindstad, E.; Polic, D.; Rialland, A.; Sandaas, I.; Stokke, T. Reaching IMO 2050 GHG Targets Exclusively Through Energy Efficiency Measures. J. Ship Prod. Des. 2023, 39, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.; Kuropyatnyk, O.; Matieiko, O.; Razinkin, R.; Stoliaryk, T.; Volkov, O. Ensuring Operational Performance and Environmental Sustainability of Marine Diesel Engines through the Use of Biodiesel Fuel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.; Karianskyi, S.; Madey, V.; Sagin, A.; Stoliaryk, T.; Tkachenko, I. Impact of Biofuel on the Environmental and Economic Performance of Marine Diesel Engines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chountalas, T.D.; Founti, M.; Tsalavoutas, I. Evaluation of biofuel effect on performance & emissions of a 2-stroke marine diesel engine using on-board measurements. Energy. 2023, 278, 127845. [Google Scholar]

- Shaafi, T.; Velraj, R. Influence of alumina nanoparticles, ethanol and isopropanol blend as additive with diesel-soybean biodiesel blend fuel: Combustion, engine performance and emissions. Renew. Energ. 2015, 80, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Lin, C.Y. Strategies for the Low Sulfur Policy of IMO—An Example of a Container Vessel Sailing through a European Route. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvounis, P.; Theotokatos, G.; Patil, C.; Xiang, L.; Ding, Y. Parametric investigation of diesel–methanol dual fuel marine engines with port and direct injection. Fuel. 2025, 381, 133441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazdauskas, M.; Lebedevas, S. Optimization of Combustion Cycle Energy Efficiency and Exhaust Gas Emissions of Marine Dual-Fuel Engine by Intensifying Ammonia Injection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.R.; Novella, R.; Climent, H.; Arnau, F.J.; Calvo, A.; Thorsen, L. Computational Analysis of an Ammonia Combustion System for Future Two-Stroke Low-Speed Marine Engines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ge, C.; Zhang, B.F.; Ma, X.; Guo, R.; Lu, X.Q. The degeneration mechanism of lubricating oil in the ammonia fuel engine. Tribol. Int. 2025, 202, 110333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, C.J.; Turnock, S.R.; Hudson, D.A. Route to zero emission shipping: Hydrogen, ammonia or methanol. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2021, 46, 28282–28297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obalalu, A.M.; Memon, M.A.; Olayemi, O.A.; Olilima, J.; Fenta, A. Enhancing heat transfer in solar-powered ships: a study on hybrid nanofluids with carbon nanotubes and their application in parabolic trough solar collectors with electromagnetic controls. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzak, S.A.; Hossain, S.M.Z.; Usama, A.; Hossain, M.M. Cleaner biodiesel production from waste oils (cooking/vegetable/frying): Advances in catalytic strategies. Fuel. 2025, 134901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, E.; Canakci, M.; Sanli, H. Biodiesel production from vegetable oil and waste animal fats in a pilot plant. Waste Manage. 2014, 34, 2146–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visan, N.A.; Carlanescu, R.; Niculescu, D.C.; Chiriac, R. Study on the cumulative effects of using a high efficiency turbocharger and biodiesel B20 fuelling on performance and emissions of a large marine diesel engine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, J.X.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, G.H. Numerical method for predicting emissions from biodiesel blend fuels in diesel engines of inland waterway vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Products from petroleum, synthetic and renewable sources - Fuels (class F) - Specifications of marine fuels. International Standard ISO 8217, Seventh edition, 2024–05.

- Vedachalam, S.; Baquerizo, N.; Dalai, A.K. Review on impacts of low sulfur regulations on marine fuels and compliance options. Fuel. 2022, 310, 122243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, D.; Choo, S.; Pham, H.T. Estimation of the non-greenhouse gas emissions inventory from ships in the port of incheon. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.X.; Huang, J.L.; Luo, J.B.; Hu, D.; Yin, Z.B. Performance enhancement and emission reduction of a diesel engine fueled with different biodiesel-diesel blending fuel based on the multi-parameter optimization theory. Fuel. 2022, 314, 122753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Tan, C.K.; Fouda, A.; Gad, M.S.; Osayed, A.E.; Hashem, A.F. Diesel engine performance, emissions and combustion characteristics of biodiesel and its blends derived from catalytic pyrolysis of waste cooking oil. Energies. 2020, 13, 5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.M.; El-Nagar, A.A.; ElKelawy, M.; Bastawissi, H.A.E. Solubility and stability enhancement of ethanol in diesel fuel by using tri-n-butyl phosphate as a new surfactant for CI engine. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarangan, D.; Sobati, M.A.; Shahnazari, S.; Ghobadian, B. Physical properties, engine performance, and exhaust emissions of waste fish oil biodiesel/bioethanol/diesel fuel blends. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nghia, N.T. , Khoa, N.X., Cho, W., Lim, O. A study the effect of biodiesel blends and the injection timing on performance and emissions of common rail diesel engines. Energies. 2022, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.F.; Jiang, G.H.; Cui, L.; Wu, G.; Zhong, S.S. Combustion analysis of low-speed marine engine fueled with biofuel. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2023, 22, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.F.; Jiang, G.H.; Wu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.Y. Effects of blended biodiesel and heavy oil on engine combustion and black carbon emissions of a low-speed two-stroke engine. Pol. Marit. Res. 2024, 1, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagin, S.; Kuropyatnyk, O.; Matieiko, O.; Razinkin, R.; Stoliaryk, T.; Volkov, O. Ensuring operational performance and environmental sustainability of marine diesel engines through the use of biodiesel fuel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A.; Agarwal, A.K. Experimental investigations of effect of Karanja biodiesel on tribological properties of lubricating oil in a compression ignition engine. Fuel. 2014, 130, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, K.N.; Raj, R.T.K. Effect of pongamia oil methyl ester–diesel blend on lubricating oil degradation of di compression ignition engine. Fuel. 2016, 165, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizer, I.; Eskici, B. Investigation on the combustion characteristics and lubrication of biodiesel and diesel fuel used in a diesel engine. Fuel. 2020, 278, 118363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B.; Jia, B. Development of a Marine Two-Stroke Diesel Engine MVEM with In-Cylinder Pressure Trace Predictive Capability and a Novel Compressor Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, K.; Özmen, G. Design and performance evaluation of low-speed marine diesel engine selective catalytic reduction system. Process Saf. Environ. 2021, 155, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAN Energy Solutions: Service Letter SL2020-694/JUSV. Cylinder and system oils MAN B&W low-speed two-stroke engines. May 2020.

- MAN Energy Solutions: Service Letter: SL2023-738/IKCA. Sampling of scavenge drain oil Adjust feed rate factor in service, and monitor piston ring and cylinder liner wear. June 2023.

- Alam, A.K. The detection of adhesive wear on cylinder liners for slow speed diesel engine through tribology, temperature, eddy current and acoustic emission measurement and analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, The Newcastle University, Tyne, England, December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ragupathi, K.; Mani, I. Durability and lube oil contamination study on diesel engine fueled with various alternative fuels: a review. Energ. Source. Part A. 2021, 43, 932–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghia, N.T. , Khoa, N.X., Cho, W., Lim, O. A study the effect of biodiesel blends and the injection timing on performance and emissions of common rail diesel engines. Energies. 2022, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Moreno, F.; Monne, C.; Morea, J.; Terradillos, J. Biodiesel improves lubricity of new low sulphur diesel fuels. Renew. Energ. 2011, 36, 2918–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.F.; Fu, X.; Li, C.J.; Niu, G.Y.; Duan, F.J.; Chen, X.L.; Hao, H.D. A novel double disc electrode excitation method for oil elemental analysis in rotating disc electrode-optical emission spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2025, 40, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Chauhan, S.R.; Goel, V.; Gupta, A.K. Impact of binary biofuel blend on lubricating oil degradation in a compression ignition engine. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2019, 141, 032203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.C.; Chavarette, F.R.; Outa, R.; Godoi, L.H.A. Assistance of analytical ferrography in the interpretation of wear test results carried out with biolubricants. Tribol. Int. 2024, 197, 109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NO. | Project | Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Engine type | MAN 6S35MEB |

| 2 | Engine stroke | 2 stroke |

| 3 | Cylinder bore (mm) | 350 |

| 4 | Engine speed (r/min) | 142 |

| 5 | Engine power (kW) | 3570 |

| 6 | Piston stroke (mm) | 1500 |

| 7 | Torque (kN) | 240 |

| 8 | Firing order | 1-5-3-4-2-6 |

| Property | 180LSFO | B24 | B50 | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) @15℃ | 958.0 | 936.2 | 911.2 | ISO 12185 |

| Kinematic viscosity (mm2/s) @40℃ | 168.6 | 47.40 | 13.51 | ISO 3104 |

| Flash point (℃) | >90.0 | >90.0 | >90.0 | ISO 2719 |

| Pour point (℃) | -6 | -6 | -6 | ISO 3016 |

| Acid number(mg KOH/g) | 1.58 | 1.37 | 0.52 | ASTM D664 |

| Ash (%, m/m) | 0.04 | 0.029 | 0.008 | ISO 6245 |

| Water content (%, v/v) | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.06 | ISO 3733 |

| Net heat of combustion (MJ/kg) | 40.87 | 40.00 | 39.59 | ASTM D240 |

| Carbon (%, m/m) | 86.5 | 84.6 | 82.0 | ASTM D6728 |

| Hydrogen (%, m/m) | 11.1 | 11.0 | 11.2 | ASTM D6728 |

| Nitrogen (%, m/m) | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.51 | ASTM D6728 |

| Oxygen (%, m/m) | 0.8 | 3.30 | 6.1 | ASTM D6728 |

| Sulphur (%, m/m) | 0.47 | 0.378 | 0.253 | ISO 8754 |

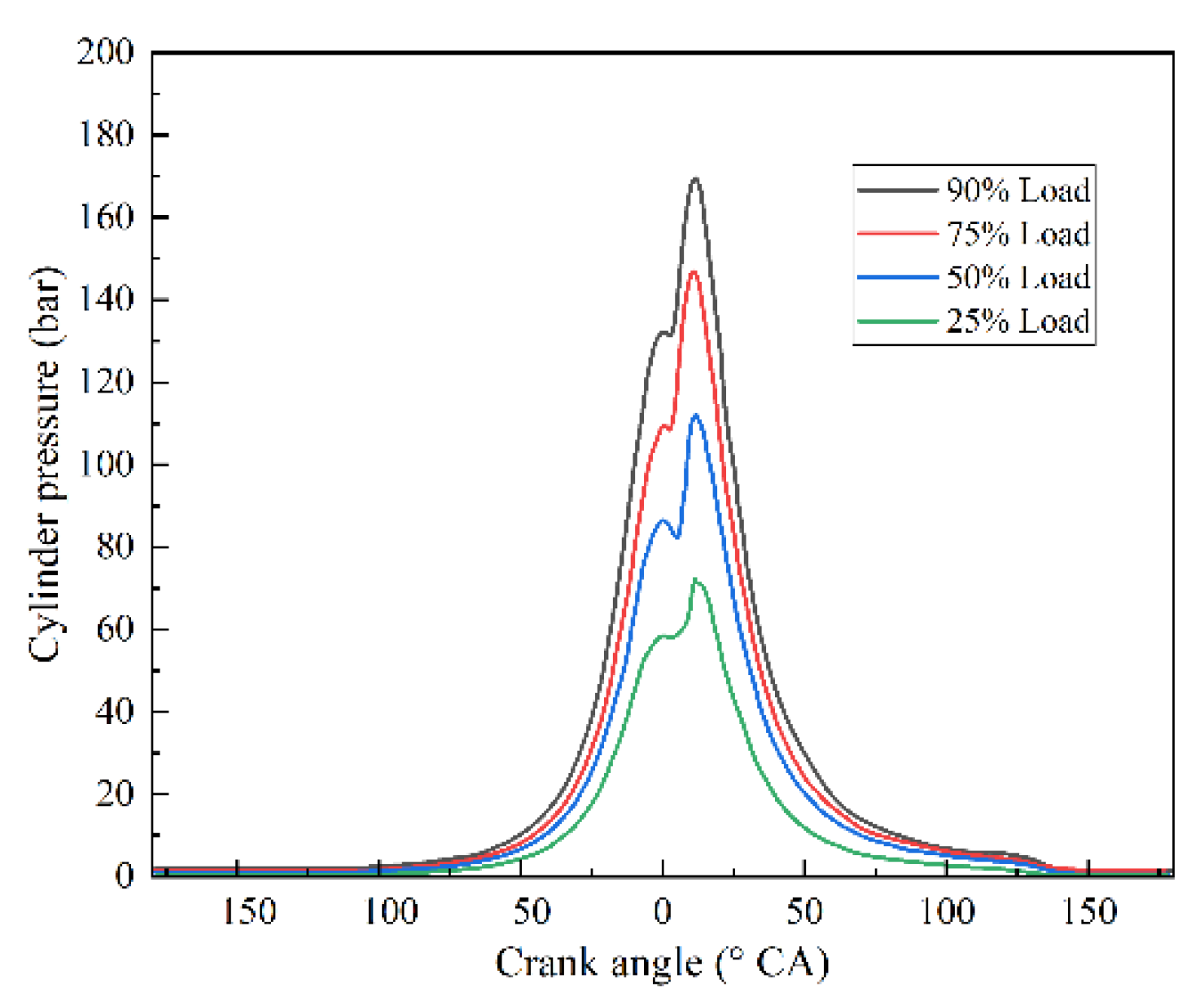

| Property | 25% Load | 50% Load | 75% Load | 90% Load |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine speed (rpm) | 90 | 112 | 130 | 138 |

| Scavenging air pressure (bar) | 0.32 | 0.89 | 1.35 | 1.85 |

| Max. compressed air pressure (bar) | 73.3 | 110.6 | 147.1 | 166.4 |

| Output power (kW) | 883 | 1769 | 2546 | 3272 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).