Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

28 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

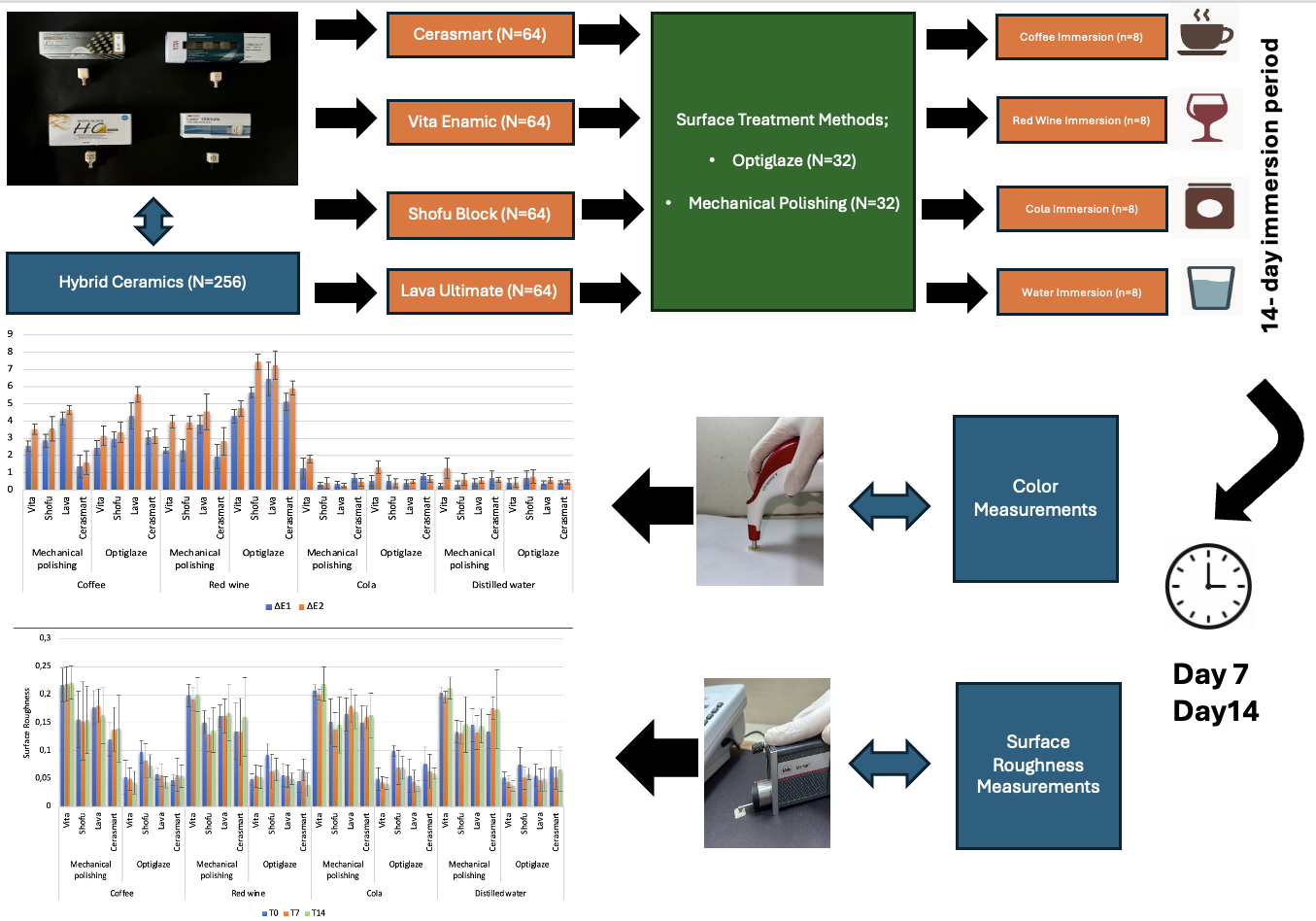

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size Calculation

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.3. Surface Finishing Procedures

2.4. Immersion Procedure

2.5. Color Measurements

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bis-EMA |

Bisphenol A Ethoxylate Dimethacrylate |

| Bis-GMA |

Bisphenol A Glycidyl Methacrylate |

| CAD/CAM |

Computer-Aided Design / Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CIE |

Internationale de l’Eclairage |

| PICN |

Polymer-Infiltrated Ceramic Network |

| RNC |

Resin Nano-Ceramic |

| TEGDMA |

Triethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate |

| UDMA | Urethane Dimethacrylate |

References

- Nassani, M.Z.; Ibraheem, S.; Shamsy, E.; Darwish, M.; Faden, A.; Kujan, O. A survey of dentists’ perception of chair-side CAD/CAM technology. Healthcare. 2021, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, C.-E.; Jivănescu, A.; Pop, D.; Stoica, E.T.; Flueras, R.; Talpoş-Niculescu, I.-C.; Cosoroabă, R.M.; Popovici, R.-A.; Olariu, I. Exploring the properties and indications of chairside CAD/CAM materials in restorative dentistry. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, G.; Camurri Piloni, A.; Nicolin, V.; Turco, G.; Di Lenarda, R. Chairside CAD/CAM materials: Current trends of clinical uses. Biology 2021, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-S.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Ahn, J. Comparison of mechanical properties of chairside CAD/CAM restorations fabricated using a standardization method. Materials. 2021, 14, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, H.; Hamama, H.H.; El-Wassefy, N.; Mahmoud, S.H. Clinical performance of resin-matrix ceramic partial coverage restorations: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 3807–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfouzan, A.F.; Alnafaiy, S.M.; Alsaleh, L.S.; Bawazir, N.H.; Al-Otaibi, H.N.; Al Taweel, S.M.; Alshehri, H.A.; Labban, N. Effects of background color and thickness on the optical properties of CAD-CAM resin-matrix ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 497.e491–497.e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S., Jr.; Sartori, N.; Phark, J.-H. Ceramic-reinforced polymers: CAD/CAM hybrid restorative materials. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2016, 3, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderico, C.M.; Picolo, M.Z.D.; Kury, M.; Azevedo, V.L.B.; Giannini, M.; Cavalli, V. Alternative surface treatments strategies for bonding to CAD/CAM resin-matrix ceramics. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facenda, J.C.; Borba, M.; Corazza, P.H. A literature review on the new polymer-infiltrated ceramic-network material (PICN). J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadır, H.S.; Bayraktar, Y. Evaluation of the repair capacities and color stabilities of a resin nanoceramic and hybrid CAD/CAM blocks. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2020, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodeyama, M.; Ikeda, H.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Masaki, C.; Hosokawa, R.; Shimizu, H. Printable PICN composite mechanically compatible with human teeth. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahrous, A.I.; Salama, A.A.; Shabaan, A.A.; Abdou, A.; Radwan, M.M. Color stability of two different resin matrix ceramics: Randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health. 2023, 23, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, N.; Gultekin, P.; Turp, V.; Akgungor, G.; Sen, D.; Mijiritsky, E. Evaluation of five CAD/CAM materials by microstructural characterization and mechanical tests: A comparative in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.; Pahinis, K.; Saltidou, K.; Dionysopoulos, D.; Tsitrou, E. Evaluation of the surface characteristics of dental CAD/CAM materials after different surface treatments. Materials. 2020, 13, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-A.; Lee, H.-A.; Chang, J.; Moon, W.; Chung, S.H.; Lim, B.-S. Color stability of dental reinforced CAD/CAM hybrid composite blocks compared to regular blocks. Materials. 2020, 13, 4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, M.; Maawadh, A.; Labban, N.; Shono, N.; Alebdi, A.; Alhijji, S.; BinMahfooz, A.M. Color change, biaxial flexural strength, and fractographic analysis of resin-modified CAD/CAM ceramics subjected to different surface finishing protocols. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozen, F.; Demirkol, N.; Oz, O.P. Effect of surface finishing treatments on the color stability of CAD/CAM materials. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2020, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Alfaraj, A.; Chu, T.M.G.; Yang, C.C.; Lin, W.S. Color stability of CAD-CAM hybrid ceramic materials following immersion in artificial saliva and wine. J. Prosthodont. 2025, 34, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolone, G.; Mandurino, M.; De Palma, F.; Mazzitelli, C.; Scotti, N.; Breschi, L.; Gherlone, E.; Cantatore, G.; Vichi, A. Color stability of polymer-based composite CAD/CAM blocks: A systematic review. Polymers 2023, 15, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, M.A.; Abdelhamid, A.M.; ElSamahy, M.; Abolgheit, S.; Hanno, K.I. Effect of aging on dimensional accuracy and color stability of CAD-CAM milled and 3D-printed denture base resins: A comparative in-vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanat-Ertürk, B. Color stability of CAD/CAM ceramics prepared with different surface finishing procedures. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, G.; Subaşı, M.G.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of thermocycling on the surface properties of resin-matrix CAD-CAM ceramics after different surface treatments. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 117, 104401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagsoz, O.; Demirci, T.; Demirci, G.; Sagsoz, N.P.; Yildiz, M. The effects of different polishing techniques on the staining resistance of CAD/CAM resin-ceramics. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkut, B.; Bud, M.; Kukey, P.; Sancakli, H.S. Effect of surface sealants on color stability of different resin composites. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2022, 95, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, D.; Tekçe, N.; Fidan, S.; Demirci, M.; Tuncer, S.; Balcı, S. The effects of various polishing procedures on surface topography of CAD/CAM resin restoratives. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motro, P.F.K.; Kursoglu, P.; Kazazoglu, E. Effects of different surface treatments on stainability of ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2012, 108, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.A.; Simionato, A.A.; Moss, O.B.; Faria, A.C.L.; Rodrigues, R.C.S.; Ribeiro, R.F. Impact of high-consumption beverages on the color, and surface roughness and microhardness of resin-matrix ceramics. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025, 62, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerliyurt, K.; Sarıkaya, I. Color stability of hybrid ceramics exposed to beverages in different combinations. BMC Oral Health. 2022, 22, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravina, R.D.; Ghinea, R.; Herrera, L.J.; Bona, A.D.; Igiel, C.; Linninger, M.; Sakai, M.; Takahashi, H.; Tashkandi, E.; Mar Perez, M.D. Color difference thresholds in dentistry. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2015, 27, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, E.G.; Smidt, L.N.; Fracasso, L.M.; Burnett, L.H., Jr.; Spohr, A.M. The effect of milling and postmilling procedures on the surface roughness of CAD/CAM materials. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 29, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H. The effect of surface roughness on ceramics used in dentistry: A review of literature. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, M.; Maawadh, A.; Labban, N.; Alnafaiy, S.M.; Alotaibi, H.N.; BinMahfooz, A.M. Effect of different surface treatments on the surface roughness and gloss of resin-modified CAD/CAM ceramics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, N.; Karaoğlanoğlu, S.; Oktay, E.A.; Ersöz, B. Superficial effects of different finishing and polishing systems on the surface roughness and color change of resin-based CAD/CAM blocks. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 23, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, O.; Dede, D.Ö.; Köroğlu, A.; Yılmaz, B. Influence of surface sealant agents on the surface roughness and color stability of artificial teeth. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N.; Oguz, E. Influence of different finishing-polishing procedures and thermocycle aging on the surface roughness of nano-ceramic hybrid CAD/CAM material. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, S.; Tekçe, N.; Kopuz, D.; Özcelik, E.Y.; Kolaylı, F.; Tuncer, S.; Demirci, M. Effect of surface roughness and biofilm formation on the color properties of resin-infiltrated ceramic and lithium disilicate glass-ceramic CAD-CAM materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 935.e931–935.e938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareem, A.S.A.; Abdel-Fattah, W.M.; El Gayar, M.I.L. Evaluation of color stability and surface roughness of smart monochromatic resin composite in comparison to universal resin composites after immersion in staining solutions. BMC Oral Health. 2025, 25, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, A.U.; Yilmaz, F.; Kulunk, T.; Guler, E.; Kurt, S. Effects of different drinks on stainability of resin composite provisional restorative materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2005, 94, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghinea, R.; Pérez, M.M.; Herrera, L.J.; Rivas, M.J.; Yebra, A.; Paravina, R.D. Color difference thresholds in dental ceramics. J. Dent. 2010, 38, e57–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Polo, C.; Muñoz, M.P.; Luengo, M.C.L.; Vicente, P.; Galindo, P.; Casado, A.M.M. Comparison of the CIELab and CIEDE2000 color difference formulas. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, S.; Yap, A.; Rosa, V.; Tan, K.; Teoh, K. Effect of staining beverages on color and translucency of CAD/CAM composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, E9–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A.; Ardu, S.; Bortolotto, T.; Krejci, I. Stain susceptibility of composite and ceramic CAD/CAM blocks versus direct resin composites with different resinous matrices. Odontology 2017, 105, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barutçugil, Ç.; Bilgili, D.; Barutcigil, K.; Dündar, A.; Büyükkaplan, U.Ş.; Yilmaz, B. Discoloration and translucency changes of CAD-CAM materials after exposure to beverages. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 122, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajangta, N.; Angkananuwat, C.; Leelaponglit, S.; Saelor, P.; Ngamjarrussriwichai, N.; Klaisiri, A. The effect of whitening and daily dentifrices on red wine staining in different types of composite resins. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llena, C.; Fernández, S.; Forner, L. Color stability of nanohybrid resin-based composites, ormocers and compomers. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, S.; Taibah, S.; Elnaghy, A. Effect of staining beverages and bleaching on optical properties of a CAD/CAM nanohybrid and nanoceramic restorative material. BMC Oral Health. 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, R.; Burrow, M.; Tyas, M. Influence of food-simulating solutions and surface finish on susceptibility to staining of aesthetic restorative materials. J. Dent. 2005, 33, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermann, A.; Vehling, D.; Eichberger, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Impact of storage media and temperature on color stability of tooth-colored CAD/CAM materials for final restorations. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2019, 17, 2280800019836832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermanli, E.; Bayazit, E.O. Color stability of CAD/CAM resin-nanoceramic vs. direct composite materials. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, S329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenković, D.D.; Tango, R.N.; Todorović, A.; Karasan, D.; Sailer, I.; Paravina, R.D. Staining and aging-dependent changes in color of CAD-CAM materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiceanu, G.; Bejan, F.R.; Vasiliu, R.D.; Porojan, S.D.; Porojan, L. The evaluation of water sorption effects on surface characteristics and color changes in direct and CAD/CAM subtractively processed resin composites. Materials 2025, 18, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoush, R.A.; Salim, N.A.; Silikas, N.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Long-term hydrolytic stability of CAD/CAM composite blocks. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 130, e12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirinejad, S.; Panahandeh, N.; Torabzadeh, H. Properties of composite resins early after curing: Color stability, degree of conversion, and dimensional stability. Int. J. Dent. 2025, 3702687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material | Material type | Manufacturer | Composition |

| Cerasmart | Resin nanoceramic | GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan | Bis-MEPP, UDMA, DMA (29 wt%) Silica and barium glass nanoparticles (Silica (20 nm), barium glass (300 nm)) (71 wt%) |

| Lava Ultimate | Resin nanoceramic | 3M, St Paul, MN, USA |

Bis-GMA, UDMA, Bis-EMA, TEGDMA (20 wt%) SiO2 (20 nm), ZrO2 (4–11 nm), aggregated ZrO2/SiO2 microcluster (80 wt%) |

| Shofu Block HC |

Resin nanoceramic | Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan |

UDMA + TEGDMA (39 wt%) Silica-based glass and silica (61 wt%) |

| Vita Enamic | Polymer-infiltrated ceramic network | Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany | UDMA, TEGDMA, (14 wt%) fine-structure feldspar ceramic, (86 wt%) |

| Material | Surface Finishing | Beverage | Code |

| Cerasmart | Optiglaze | Cola | Cs-Og-Co |

| Cerasmart | Optiglaze | Red wine | Cs-Og-Rw |

| Cerasmart | Optiglaze | Coffee | Cs-Og-Cf |

| Cerasmart | Optiglaze | Water | Cs-Og-W |

| Cerasmart | Mechanihal polishing | Cola | Cs-Mp-Co |

| Cerasmart | Mechanical polishing | Red wine | Cs-Mp-Rw |

| Cerasmart | Mechanical polishing | Coffee | Cs-Mp-Cf |

| Cerasmart | Mechanical polishing | Water | Cs-Mp-W |

| Lava Ultimate | Optiglaze | Cola | Lu-Og-Co |

| Lava Ultimate | Optiglaze | Red wine | Lu-Og-Rw |

| Lava Ultimate | Optiglaze | Coffee | Lu-Og-Cf |

| Lava Ultimate | Optiglaze | Water | Lu-Og-W |

| Lava Ultimate | Mechanihal polishing | Cola | Lu-Mp-Co |

| Lava Ultimate | Mechanihal polishing | Red wine | Lu-Mp-Rw |

| Lava Ultimate | Mechanihal polishing | Coffee | Lu-Mp-Cf |

| Lava Ultimate | Mechanihal polishing | Water | Lu-Mp-W |

| Shofu Block | Optiglaze | Cola | Sh-Og-Co |

| Shofu Block | Optiglaze | Red wine | Sh-Og-Rw |

| Shofu Block | Optiglaze | Coffee | Sh-Og-Cf |

| Shofu Block | Optiglaze | Water | Sh-Og-W |

| Shofu Block | Mechanihal polishing | Cola | Sh-Mp-Co |

| Shofu Block | Mechanihal polishing | Red wine | Sh-Mp-Rw |

| Shofu Block | Mechanihal polishing | Coffee | Sh-Mp-Co |

| Shofu Block | Mechanihal polishing | Water | Sh-Mp-W |

| Vita Enamic | Optiglaze | Cola | Ve-Og-Co |

| Vita Enamic | Optiglaze | Red wine | Ve-Og-Rw |

| Vita Enamic | Optiglaze | Coffee | Ve-Og-Cf |

| Vita Enamic | Optiglaze | Water | Ve-Og-W |

| Vita Enamic | Mechanihal polishing | Cola | Ve-Mp-Co |

| Vita Enamic | Mechanihal polishing | Red wine | Ve-Mp-Rw |

| Vita Enamic | Mechanihal polishing | Coffee | Ve-Mp-Cf |

| Vita Enamic | Mechanihal polishing | Water | Ve-Mp-W |

| Source | Degree of Freedom | F-Value | p-Value |

| Material (M) | 3 | 54.797 | 0.001 |

| Beverage (B) | 3 | 1499.317 | 0.001 |

| Surface finishing (SF) | 1 | 215.061 | 0.001 |

| Immersion time (IT) | 1 | 557.177 | 0.001 |

| M x IT | 3 | 33.492 | 0.001 |

| B x IT | 3 | 107.48 | 0.001 |

| SF x IT | 1 | 6.409 | 0.012 |

| M x B x IT | 9 | 11.094 | 0.001 |

| M x SF x IT | 3 | 16.273 | 0.001 |

| B x SF x IT | 3 | 3.956 | 0.009 |

| M x B x SF x IT | 9 | 5.57 | 0.001 |

| 1 week | 2 week | ||||

| Beverage | Surface finishing | Material | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | p |

| Coffee | Mechanical polishing | Vita | 2.54±0.30Aa | 3.54±0.29Ab | 0.001 |

| Shofu | 2.87±0.38Aa | 3.56±0.70Ab | 0.002 | ||

| Lava | 4.16±0.37Ba | 4.66±0.24Bb | 0.001 | ||

| Cerasmart | 1.39±0.66Ca | 1.60±0.69Ca | 0.116 | ||

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Optiglaze | Vita | 2.45±0.42Aa | 3.16±0.55Ab | 0.001 | |

| Shofu | 2.96±0.43Aa | 3.36±0.61Ab | 0.029 | ||

| Lava | 4.30±0.77Ba | 5.56±0.45Bb | 0.001 | ||

| Cerasmart | 3.05±0.38Aa | 3.13±0.44Aa | 0.182 | ||

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Red wine | Mechanical polishing | Vita | 2.31±0.18Aa | 3.97±0.37Ab | 0.001 |

| Shofu | 2.32±0.61Aa | 3.92±0.38Ab | 0.001 | ||

| Lava | 3.82±0.51Ba | 4.55±1.04Ab | 0.008 | ||

| Cerasmart | 1.94±0.70Aa | 2.84±0.80Bb | 0.001 | ||

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Optiglaze | Vita | 4.28±0.39Aa | 4.74±0.46Ab | 0.002 | |

| Shofu | 5.66±0.30BCa | 7.44±0.45Bb | 0.001 | ||

| Lava | 6.44±0.96Ca | 7.24±0.83Bb | 0.001 | ||

| Cerasmart | 5.12±0.50Ba | 5.92±0.40Cb | 0.001 | ||

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Cola | Mechanical polishing | Vita | 1.27±0.60Aa | 1.82±0.23Ab | 0.027 |

| Shofu | 0.31±0.12Ba | 0.42±0.33Ba | 0.260 | ||

| Lava | 0.34±0.16Ba | 0.26±0.11Ba | 0.309 | ||

| Cerasmart | 0.71±0.24Ba | 0.46±0.22Bb | 0.001 | ||

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Optiglaze | Vita | 0.54±0.31ABa | 1.33±0.36Ab | 0.003 | |

| Shofu | 0.54±0.33ABa | 0.40±0.25Ba | 0.221 | ||

| Lava | 0.41±0.17Aa | 0.50±0.12Ba | 0.114 | ||

| Cerasmart | 0.80±0.16Ba | 0.65±0.20Ba | 0.134 | ||

| p | 0.036 | 0.001 | |||

| Water | Mechanical polishing | Vita | 0.25±0.13Aa | 1.28±0.58Ab | 0.002 |

| Shofu | 0.33±0.21Aa | 0.61±0.34Ba | 0.070 | ||

| Lava | 0.44±0.21ABa | 0.57±0.18Ba | 0.283 | ||

| Cerasmart | 0.70±0.41Ba | 0.60±0.15Ba | 0.474 | ||

| p | 0.010 | 0.001 | |||

| Optiglaze | Vita | 0.40±0.26Aa | 0.45±0.28Aa | 0.139 | |

| Shofu | 0.71±0.41Aa | 0.77±0.40Aa | 0.548 | ||

| Lava | 0.39±0.13Aa | 0.59±0.17Ab | 0.005 | ||

| Cerasmart | 0.43±0.11Aa | 0.47±0.12Aa | 0.606 | ||

| p | 0.057 | 0.082 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).