Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

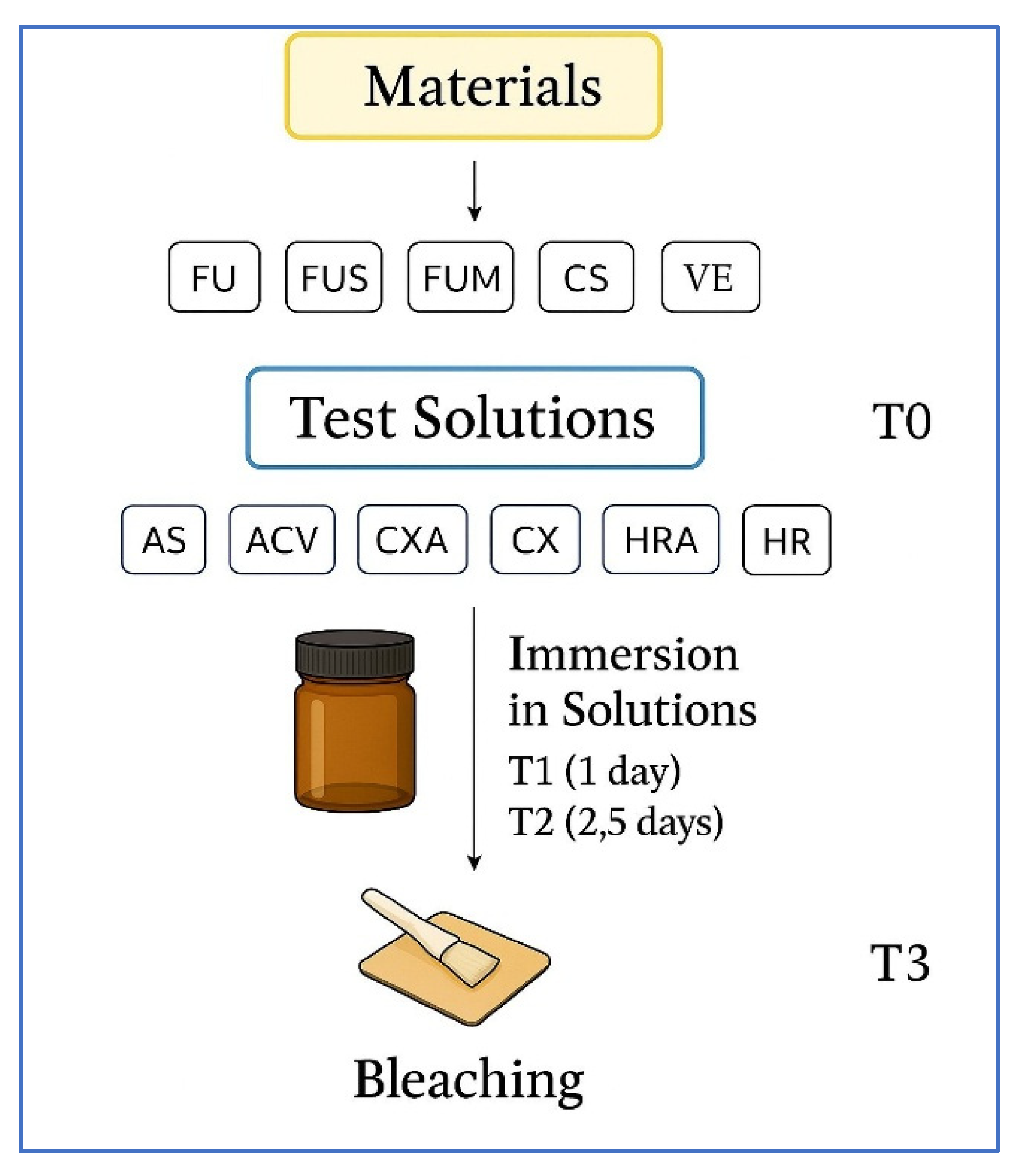

2.1. Design of the Study

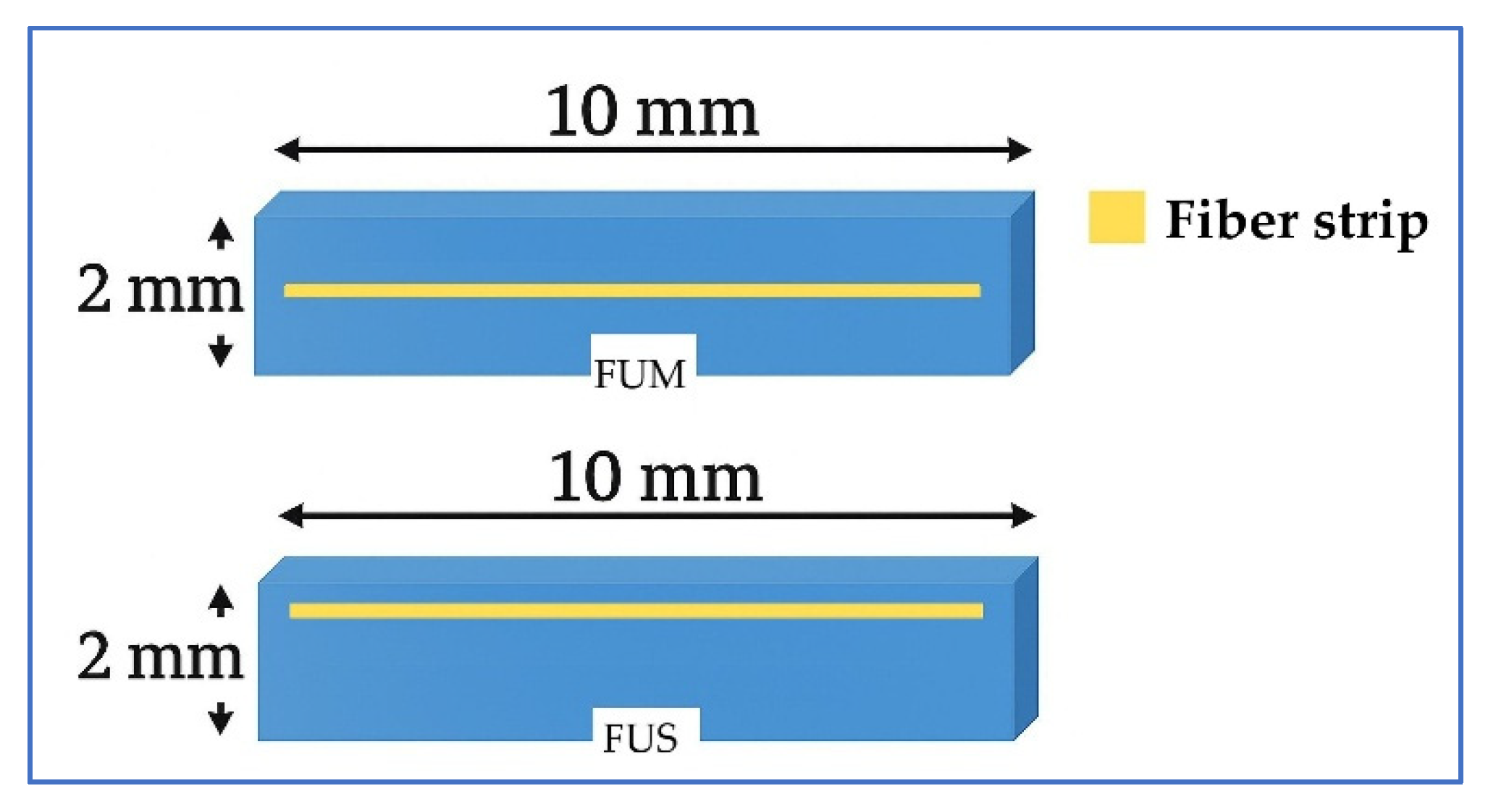

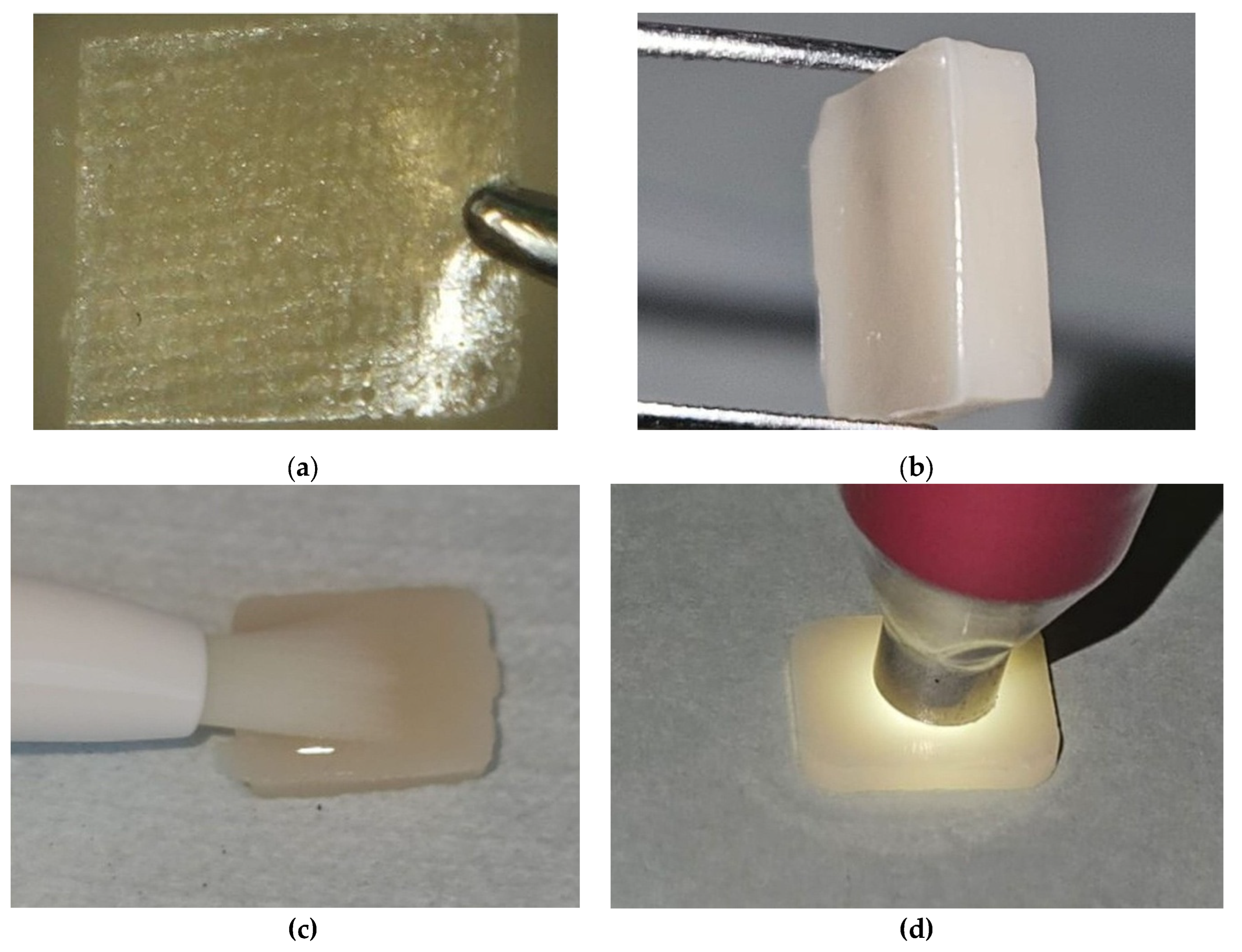

2.2. Preparation of Specimens

2.3. Immersion in Solutions and Bleaching

2.4. Color and Surface Measurements

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

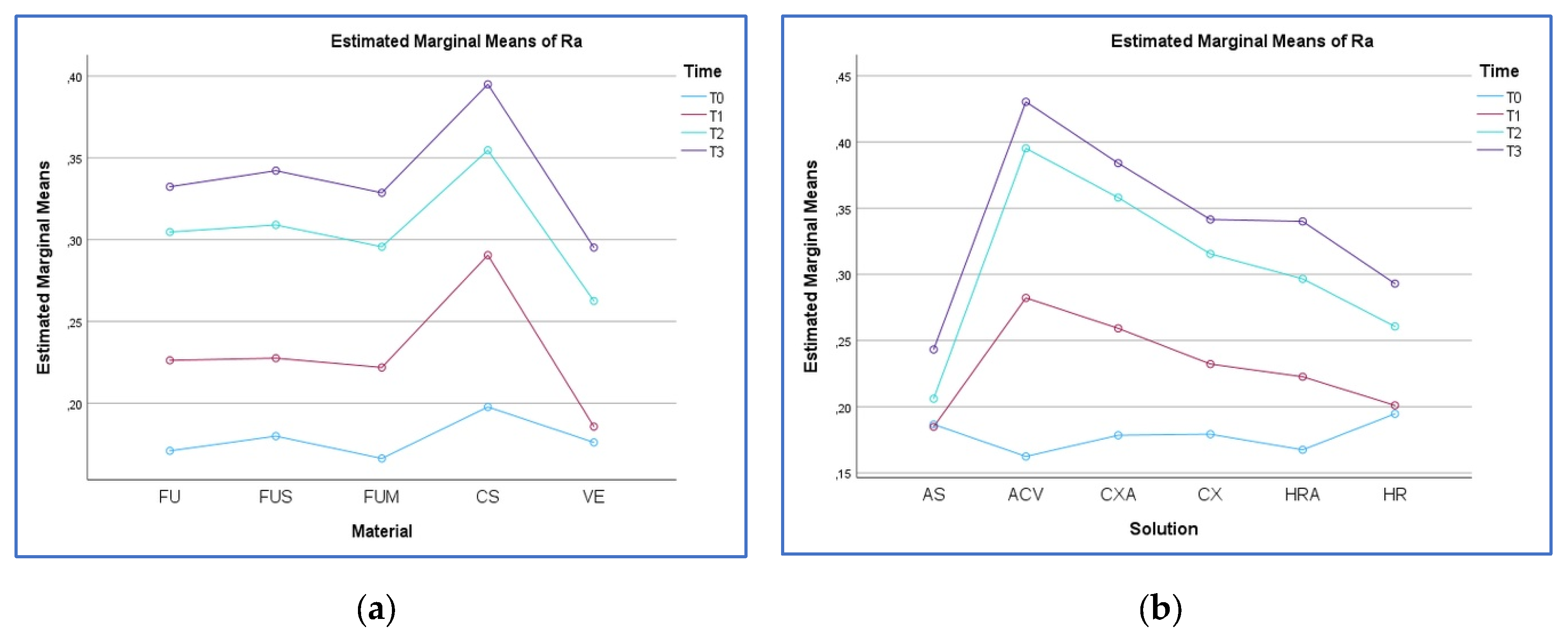

3.1. Surface Roughness Analysis

3.2. ∆E00 Analysis

3.3. ∆WID Analysis

3.4. SEM Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RC | Resin composite |

| Bis-GMA | Bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate |

| TEGDMA | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

| Bis-EMA | Bisphenol A ethoxylate dimethacrylate |

| CAD/CAM | Computer-aided design / computer-aided manufacturing |

| RNC | Resin nanoceramic |

| PICN | Polymer-infiltrated ceramic network |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| ACV | Apple cider vinegar |

| CP | Carbamide peroxide |

| HP | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HPS | Hydrogen peroxide superior |

| ∆E00 | Color change |

| ∆WID | Whiteness index change |

| CS | Cerasmart 270 |

| VE | Vita Enamic |

| FU | Filtek Universal |

| FUM | Filtek Universal with mid-layer fiber strip |

| FUS | Filtek Universal with superficial fiber strip |

| GF | Glass fiber |

| ES | everStick NET |

| AS | Artificial saliva |

| CXA | Chlorhexidine- and alcohol-containing mouthwash |

| CX | Chlorhexidine- and alcohol-free mouthwash |

| HRA | Herbal and alcohol-containing mouthwash |

| HR | Herbal and alcohol-free mouthwash |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| T | Time point |

| WID | Whiteness change index |

| Ra | Average surface roughness |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| PT | Perceptibility threshold for color change |

| AT | Acceptability threshold for color change |

| WPT | Perceptibility threshold for whiteness index change |

| WAT | Acceptability threshold for whiteness index change |

| PF | Polyethylene fiber |

References

- Aydınoǧlu, A.; Erdem Hepşenoǧlu, Y.; Yalçın, C.Ö.; Saǧır, K.; Ölçer Us, Y.; Eroǧlu, Ş.E.; Hazar Yoruç, A.B. Assessing Toxicological Safety of EverX Posterior and Filtek Ultimate: An In-Depth Extractable and Leachable Study Under ISO 10993-17 and 10993-18 Standards. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 9903–9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Bhardwaj, B.; Nag, M. Resin based restorative dental materials: characteristics and future perspectives. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2019, 55, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic-Stankovic, T. , Karadzic, B.; Komlenic, V.; Stasic, J.; Petrovic, V.; Ilic, J.; Miletic, V. Effects of whitening gels on color and surface properties of a microhybrid and nanohybrid composite. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy Vaizoğlu, G.; Ulusoy, N.; Güleç Alagöz, L. Effect of Coffee and Polishing Systems on the Color Change of a Conventional Resin Composite Repaired by Universal Resin Composites: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2023, 16, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, L.; Bortolotto, T.; Krejci, I. Comparative in vitro wear resistance of CAD/CAM composite resin and ceramic materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yu, P.; Arola, D.D.; Min, J.; Gao, S. A comparative study on the wear behavior of a polymer infiltrated ceramic network (PICN) material and tooth enamel. Dent Mater. 2017, 33, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.; Bogra, P.; Bansal, R.; Grover, V.; Gupta, S. Comparative Evaluation of Color Stability and Surface Roughness of Bulk-Fill and Nanohybrid Composites Following Long-Term Mouthrinse Exposure: An In Vitro Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e84320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElEmbaby, A. El-S. The effects of mouth rinses on the color stability of resin-based restorative materials. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2014, 26, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, N.; Laflouf, M. Effectiveness of Apple Cider Vinegar and Mechanical Removal on Dental Plaque and Gingival Inflammation of Children With Cerebral Palsy. Cureus 2022, 14, e26874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagnik, D.; Serafin, V.; J Shah, A. Antimicrobial activity of apple cider vinegar against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans; downregulating cytokine and microbial protein expression. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hannig, M. Vinegar inhibits the formation of oral biofilm in situ. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giti, R.; Jebal, R. How could mouthwashes affect the color stability and translucency of various types of monolithic zirconia? An in-vitro study. PloS One 2023, 18, e0295420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, S.; Davoudi, A.; Momtazi, H. In vitro comparative effects of alcohol-containing and alcohol-free mouthwashes on surface roughness of bulk-fill composite resins. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookes, Z.L.S.; Bescos, R.; Belfield, L.A.; Ali, K.; Roberts, A. Current uses of chlorhexidine for management of oral disease: a narrative review. J. Dent. 2020, 103, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, K.; Özdemir, E.; Gönüldaş, F. Effect of immune-boosting beverage, energy beverage, hydrogen peroxide superior, polishing methods and fine-grained dental prophylaxis paste on color of CAD-CAM restorative materials. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha Mallick, R.; Sarangi, P.; Suman, S.; Sekhar Sahoo, S.; Bajoria, A.; Sharma, G. An In Vitro Analysis of the Effects of Mouthwashes on the Surface Properties of Composite Resin Restorative Material. Cureus 2024, 16, e65021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ccahuana, L.; Álvarez-Vidigal, E.; Arriola-Guillén, E.; Aguilar-Gálvez, D. Effect of pediatric mouthwashes on the color stability of dental restorations with composite resins. In vitro comparative study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, e897–e902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavex Bite&White In-Office System. Available online: https://www.cavex.nl/producten/whitening-and-oral-care-en/whitening-en/cavex-bitewhite-in-office-systeem/?lang=en (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Yılmaz, K.; Özdemir, E.; Gönüldaş, F. Effects of immersion in various beverages, polishing and bleaching systems on surface roughness and microhardness of CAD/CAM restorative materials. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasany, R.; Jamjoon, F. Z.; Kendirci, M. Y.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of Printing Layer Thickness on Optical Properties and Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed Resins: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 37, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadipour, H.S.; Farajzadeh, M.; Toutouni, H.; Gazerani, A.; Sekandari, S. Fracture Resistance of Fiber-Reinforced vs. Conventional Resin Composite Restorations in Structurally Compromised Molars: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Dent. 2025, 5169253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, L.B.; Pereira da Silva, L.; Manarte-Monteiro, P. Fracture Resistance of Fiber-Reinforced Composite Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Polymers 2023, 15, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando Cascales, Á.; Andreu Murillo, A.; Ferrando Cascales, R.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Sauro, S.; Carreras-Presas, C.M.; Hirata, R.; Lijnev, A. Revolutionizing Restorative Dentistry: The Role of Polyethylene Fiber in Biomimetic Dentin Reinforcement-Insights from In Vitro Research. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozakar Ilday, N.; Celik, N.; Bayindir, Y.Z.; Seven, N. Effect of water storage on the translucency of silorane-based and dimethacrylate-based composite resins with fibres. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M. del M.; Saleh, A.; Yebra, A.; Pulgar, R. Study of the variation between CIELAB delta E* and CIEDE2000 color-differences of resin composites. Dent. Mater. J. 2007, 26, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M. del M.; Ghinea, R.; Rivas, M.J.; Yebra, A.; Ionescu, A.M.; Paravina, R.D.; Herrera, L. J. Development of a customized whiteness index for dentistry based on CIELAB color space. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessa, N.A. Effect of mouthwashes on the microhardness of aesthetic composite restorative materials. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2023, 46, e1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker Kader, I.; Yuzbasioglu, E.; Smail, F.S.; Ilhan, C. How do various mouth rinses influence the color stability of CAD-CAM resin-based restorative materials? J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 1584.e1–1584.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N. Accelerated versus Slow In Vitro Aging Methods and Their Impact on Universal Chromatic, Urethane-Based Composites. Materials 2023, 16, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Swaaij, B.W.M.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A.; Timmerman, M.F.; Ruben, J. Fluoride, pH Value, and Titratable Acidity of Commercially Available Mouthwashes. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellis, R.P.; Barbour, M.E.; Jones, S.B.; Addy, M. Effects of pH and acid concentration on erosive dissolution of enamel, dentine, and compressed hydroxyapatite. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 118, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.P.; Zhang, L. Effect of veneering techniques on color and translucency of Y-TZP. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 19, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, R.C.; Ramos, A.C.; Dos Santos Nunes Reis, J.M.; Dovigo, L.N.; Salomon, J.G.O.; Del Mar Pérez, M.; Fonseca, R.G. Effect of polishing and bleaching on color, whiteness, and translucency of CAD/CAM monolithic materials. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2025, 37, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.; Zinelis, S.; Papavasiliou, G.; Kamposiora, P. Effect of aging on color, gloss and surface roughness of CAD/CAM composite materials. J. Dent. 2023, 130, 104423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, V.; Miller, N.C.; Ding, R.; Beschorner, K. E.; Jacobs, T.D.B. Evaluating scanning electron microscopy for the measurement of small-scale topography. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2024, 12, 10.1088–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, C.M.; Lambrechts, P.; Quirynen, M. Comparison of surface roughness of oral hard materials to the threshold surface roughness for bacterial plaque retention: a review of the literature. Dent. Mater. 1997, 13, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.S.; Billington, R.W.; Pearson, G.J. The in vivo perception of roughness of restorations. Br. Dent. J. 2004, 196, 42–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintze, S.D.; Forjanic, M.; Rousson, V. Surface roughness and gloss of dental materials as a function of force and polishing time in vitro. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, K.; Tekçe, N.; Tuncer, S.; Serim, M. E.; Demirci, M. Evaluation of the surface hardness, roughness, gloss and color of composites after different finishing/polishing treatments and thermocycling using a multitechnique approach. Dent. Mater. J. 2016, 35, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, É.F.; Girundi, A.L.G.; Alexandrino, L.D.; Morel, L.L.; de Almeida, M.V.R.; Dos Santos, V.R.; Fraga, S.; da Silva, W.J.; Mengatto, C.M. Effects of disinfection with a vinegar-hydrogen peroxide mixture on the surface characteristics of denture acrylic resins. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 28, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferracane, J.L. Hygroscopic and hydrolytic effects in dental polymer networks. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willershausen, I.; Weyer, V.; Schulte, D.; Lampe, F.; Buhre, S.; Willershausen, B. In vitro study on dental erosion caused by different vinegar varieties using an electron microprobe. Clin. Lab. 2014, 60, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontefract, H.; Hughes, J.; Kemp, K.; Yates, R.; Newcombe, R.G.; Addy, M. The erosive effects of some mouthrinses on enamel. A study in situ. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2001, 28, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, N.E. , Oğuz, E.İ. The Effect of Erosive Media on Color Stability, Gloss, and Surface Roughness of Monolithic CAD/CAM Materials Subjected to Different Polishing Methods. Sci. Rep. 2015, 15, 23774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, T.M.; Abdelnabi, A.; Othman, M.S.; Bayoumi, R.E.; Abdelraouf, R.M. Effect of Different Mouthwashes on the Surface Microhardness and Color Stability of Dental Nanohybrid Resin Composite. Polymers 2023, 15, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy Vaizoğlu, G. Effect of Bleaching on Surface Roughness of Universal Composite Resins After Chlorhexidine-Induced Staining. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravina, R.D.; Pérez, M.M.; Ghinea, R. Acceptability and perceptibility thresholds in dentistry: A comprehensive review of clinical and research applications. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais Sampaio, G.A.; Rangel Peixoto, L.; Vasconcelos Neves, G.; Nascimento Barbosa, D.D. Effect of mouthwashes on color stability of composite resins: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gömleksiz, S.; Okumuş, Ö.F. The effect of whitening toothpastes on the color stability and surface roughness of stained resin composite. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazar, A.; Hazar, E. Effects of different antiviral mouthwashes on the surface roughness, hardness, and color stability of composite CAD/CAM materials. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2024, 22, 22808000241248886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festuccia, M.S.; Garcia, L. da F.; Cruvinel, D.R.; Pires-De-Souza, F. de C. Color stability, surface roughness and microhardness of composites submitted to mouthrinsing action. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erturk-Avunduk, A.T.; Delikan, E.; Cengiz-Yanardag, E.; Karakaya, I. Effect of whitening concepts on surface roughness and optical characteristics of resin-based composites: An AFM study. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosharraf, R.; Torkan, S. Fracture Resistance of Composite Fixed Partial Dentures Reinforced with Pre-impregnated and Non-impregnated Fibers. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2012, 6, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncdemir, A.R.; Güven, M.E. Effects of Fibers on Color and Translucency Changes of Bulk-Fill and Anterior Composites after Accelerated Aging. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2908696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caydamli, Y.; Heudorfer, K.; Take, J.; Podjaski, F.; Middendorf, P.; Buchmeiser, M. R. Transparent Fiber-Reinforced Composites Based on a Thermoset Resin Using Liquid Composite Molding (LCM) Techniques. Materials 2021, 14, 6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, H.; Saiki, O.; Nogawa, H.; Hiraba, H.; Okazaki, T.; Matsumura, H. Surface roughness and gloss of current CAD/CAM resin composites before and after toothbrush abrasion. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A.; Beleidy, M.; El-Din, Y.A. Biocompatibility and Surface Roughness of Different Sustainable Dental Composite Blocks: Comprehensive In Vitro Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 34258–34267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatas, O.; Ilday, N.O.; Bayindir, F.; Celik, N.; Seven, N. Effect of fiber reinforcement on color stability of composite resins. J. Conserv. Dent. 2020, 23, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attin, T.; Hannig, C.; Wiegand, A.; Attin, R. Effect of bleaching on restorative materials and restorations--a systematic review. Dent. Mater. 2004, 20, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meniawi, M.; Şirinsükan, N.; Can, E. Color stability, surface roughness, and surface morphology of universal composites. Odontology Advance online publication. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijken, J.W.; Sunnegårdh-Grönberg, K. Fiber-reinforced packable resin composites in Class II cavities. J. Dent. 2006, 34, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Brand | Code | Description | Composition | pH | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Material |

Cerasmart 270 |

CS |

Resin nanoceramic blocks |

Inorganic phase (71 wt%): Silica nanoparticles, barium glass ceramic particles, glass phase containing strontium and aluminum, nanoceramic filler. Organic phase (29 wt%): UDMA, Bis-MEPP, DMA, other auxiliary dimethacrylates | GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan | |

|

Vita Enamic |

VE |

Polymer-infiltrated ceramic network blocks | Inorganic phase (86 wt%): Feldspathic ceramic network (SiO₂, Al₂O₃, Na₂O, K₂O), zirconia, sodium aluminosilicate glass. Organic phase (14 wt%): UDMA, TEGDMA, Bis-GMA, PMMA, and other dimethacrylates | VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany | ||

|

Filtek Universal |

FU |

Nanohybrid RC for universal use | Inorganic fillers (76.5 wt%): Zirconia/silica nanoparticles, spherical silica nanoparticles (~20 nm), aggregate structures (0.6–1.4 µm). Organic resin matrix (23.5 wt%): Bis-GMA, UDMA, TEGDMA, Bis-EMA | 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA | ||

| everStick NET | ES | PMMA-based glass fiber strip | Fiber phase (44–46 vol%): E-glass fiber (7–10 µm). Polymer matrix (54–56 vol%): Bis-GMA, PMMA | GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan | ||

|

Solution |

Testonic Artificial Saliva |

AS |

Artificial saliva (ISO 7491:2000) | Sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride, bicarbonate and phosphate ions, viscosity enhancers, preservatives |

6.8 |

Colin Kimya, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Kühne Apple Vinegar | ACV | Apple cider vinegar | Acetic acid, plant extract (apple), antioxidant | 4.1 | Carl Kühne KG, Hamburg, Germany | |

| Andorex Mouthwash |

CXA |

CHX/alcohol mouthwash | 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate, benzydamine hydrochloride, Patent Blue V, glycerol, polysorbate 20, tartrazine (E102), ethanol, purified water | 5.2 | Humanis Health, Istanbul, Turkey | |

| Klorhex Plus Mouthwash |

CX |

CHX/no alcohol mouthwash | 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate, flurbiprofen, Patent Blue V (E131), sorbitol, glycerol, purified water | 5.5 | Drogsan GmbH, Ankara, Turkey | |

| One Drop Only |

HRA |

CHX/alcohol mouthwash | Aqua, menthol, thymol, eugenol, benzyl benzoate, alcohol, menthol, peppermint oil, tree resin, sage oil, tea tree oil, limonene, linalool, citral, water | 6.8 | One Drop Only GmbH, Berlin, Germany | |

| Agarta Mouthwash |

HR |

CHX/no alcohol mouthwash | Bay leaf, licorice root, sage oil, laurel extract, chamomile flower extract, peppermint oil, green tea, propolis extract, menthol, glycerin, water | 6.8 | Agarta Cosmetics, Ankara, Turkey |

| Source | Sum of squares | df | F | p-value | Partial eta squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | Material | 0.811 | 4 | 25.429 | <0.001 | 0.086 |

| Solution | 1.611 | 5 | 40.415 | <0.001 | 0.158 | |

| Time | 4.737 | 3 | 198.009 | <0.001 | 0.355 | |

| Material-solution | 0.053 | 20 | 0.333 | 0.998 | 0.006 | |

| Material-time | 0.142 | 12 | 1.488 | 0.122 | 0.016 | |

| Solution-time | 0.979 | 15 | 8.182 | <0.001 | 0.102 | |

| Material-solution-time | 0.170 | 60 | 0.354 | 1.000 | 0.019 | |

| ∆E00 | Material | 57.330 | 4 | 53.796 | <0.001 | 0.210 |

| Solution | 175.886 | 5 | 132.035 | <0.001 | 0.449 | |

| Time | 119.740 | 2 | 224.717 | <0.001 | 0.357 | |

| Material-solution | 18.050 | 20 | 3.387 | <0.001 | 0.077 | |

| Material-time | 14.037 | 8 | 6.586 | <0.001 | 0.061 | |

| Solution-time | 23.517 | 10 | 8.827 | <0.001 | 0.098 | |

| Material-solution-time | 8.441 | 40 | 0.792 | 0.819 | 0.038 | |

| ∆WID | Material | 8.067 | 4 | 6.505 | <0.001 | 0.031 |

| Solution | 91.938 | 5 | 59.304 | <0.001 | 0.268 | |

| Time | 448.372 | 2 | 723.042 | <0.001 | 0.641 | |

| Material-solution | 30.041 | 20 | 4.844 | <0.001 | 0.107 | |

| Material-time | 16.662 | 8 | 6.717 | <0.001 | 0.062 | |

| Solution-time | 93.496 | 10 | 30.154 | <0.001 | 0.271 | |

| Material-solution-time | 16.392 | 40 | 1.322 | 0.090 | 0.061 |

| AS | ACV | CXA | CX | HRA | HR | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FU |

T0 | 0.18 ± 0.11 | 0.13 ± 0.05a | 0.18 ± 0.11a | 0.17 ± 0.07a | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.17 ± 0.08a |

| T1 | 0.17 ± 0.04A | 0.27 ± 0.10Ba | 0.25 ± 0.23Bb | 0.22 ± 0.04ABa | 0.22 ± 0.09AB | 0.20 ± 0.08AB | 0.22 ± 0.12b | |

| T2 | 0.20 ± 0.05A | 0.40 ± 0.10Bb | 0.34 ± 0.15Bc | 0.32 ± 0.09Cb | 0.30 ± 0.07C | 0.24 ± 0.05A | 0.30 ± 0.11c | |

| T3 | 0.24 ± 0.06A | 0.43 ± 0.08Bc | 0.38 ± 0.17Bc | 0.33 ± 0.10Cb | 0.33 ± 0.08C | 0.26 ± 0.06A | 0.33 ± 0.11d | |

| Total | 0.20 ± 0.07A | 0.31 ± 0.14B | 0.29 ± 0.18C | 0.26 ± 0.10C | 0.25 ± 0.10D | 0.22 ± 0.07E | 0.25 ± 0.12 | |

|

FUS |

T0 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.05a | 0.16 ± 0.10a | 0.17 ± 0.06a | 0.18 ± 0.05a | 0.18 ± 0.06a | 0.17 ± 0.06a |

| T1 | 0.18 ± 0.06A | 0.28 ± 0.02Bb | 0.25 ± 0.11Ab | 0.22 ± 0.04Ab | 0.23 ± 0.02Aa | 0.19 ± 0.07Aa | 0.22 ± 0.07b | |

| T2 | 0.21 ± 0.03A | 0.40 ± 0.11Bc | 0.35 ± 0.09Bc | 0.32 ± 0.10Bc | 0.28 ± 0.05Ab | 0.26 ± 0.05Ab | 0.30 ± 0.10c | |

| T3 | 0.24 ± 0.04A | 0.45 ± 0.09Bd | 0.37 ± 0.06Cd | 0.36 ± 0.08Cd | 0.31 ± 0.06Ac | 0.29 ± 0.09Ac | 0.34 ± 0.10d | |

| Total | 0.20 ± 0.05A | 0.33 ± 0.13B | 0.28 ± 0.12C | 0.27 ± 0.10C | 0.25 ± 0.07D | 0.23 ± 0.08E | 0.26 ± 0.10 | |

|

FUM |

T0 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 0.14 ± 0.04a | 0.16 ± 0.04a | 0.17 ± 0.04a | 0.16 ± 0.06a | 0.16 ± 0.09a | 0.16 ± 0.06a |

| T1 | 0.17 ± 0.03A | 0.28 ± 0.04Bb | 0.25 ± 0.09Ab | 0.22 ± 0.04Aa | 0.20 ± 0.06Aa | 0.18 ± 0.06Aa | 0.22 ± 0.06b | |

| T2 | 0.20 ± 0.06A | 0.36 ± 0.11Bc | 0.37 ± 0.09Bc | 0.29 ± 0.07Bb | 0.28 ± 0.16Ab | 0.26 ± 0.13Ab | 0.29 ± 0.12c | |

| T3 | 0.23 ± 0.03A | 0.41 ± 0.07Bd | 0.36 ± 0.07Bc | 0.30 ± 0.11Ac | 0.33 ± 0.13Bc | 0.32 ± 0.12Cc | 0.32 ± 0.11d | |

| Total | 0.19 ± 0.06A | 0.30 ± 0.12B | 0.28 ± 0.11C | 0.25 ± 0.09C | 0.24 ± 0.12D | 0.23 ± 0.12E | 0.25 ± 0.11 | |

|

CS |

T0 | 0.21 ± 0.14 | 0.18 ± 0.11a | 0.18 ± 0.05a | 0.18 ± 0.06a | 0.15 ± 0.03a | 0.27 ± 0.39a | 0.19 ± 0.17a |

| T1 | 0.22 ± 0.05A | 0.35 ± 0.03Bb | 0.32 ± 0.04Bb | 0.30 ± 0.01Ab | 0.27 ± 0.05Ab | 0.26 ± 0.02Aa | 0.29 ± 0.05b | |

| T2 | 0.23 ± 0.03A | 0.44 ± 0.08Bc | 0.40 ± 0.09Bc | 0.37 ± 0.04Bc | 0.35 ± 0.10Cc | 0.31 ± 0.08Ca | 0.35 ± 0.10c | |

| T3 | 0.28 ± 0.05A | 0.47 ± 0.06Bd | 0.44 ± 0.10Bd | 0.39 ± 0.05Cd | 0.42 ± 0.14Bd | 0.35 ± 0.08Ab | 0.39 ± 0.10d | |

| Total | 0.23 ± 0.08A | 0.36 ± 0.13B | 0.33 ± 0.12C | 0.31 ± 0.09C | 0.30 ± 0.13C | 0.30 ± 0.20D | 0.30 ± 0.14 | |

|

VE |

T0 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.05a | 0.19 ± 0.12a | 0.19 ± 0.13a | 0.18 ± 0.03a | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.07a |

| T1 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.04a | 0.21 ± 0.06a | 0.19 ± 0.06a | 0.17 ± 0.02a | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.04a | |

| T2 | 0.17 ± 0.06A | 0.35 ± 0.04Bb | 0.31 ± 0.05Bb | 0.26 ± 0.03Ba | 0.25 ± 0.06Bb | 0.21 ± 0.02C | 0.26 ± 0.07b | |

| T3 | 0.22 ± 0.06A | 0.37 ± 0.03Bb | 0.34 ± 0.07Bc | 0.30 ± 0.05Bb | 0.29 ± 0.09Cc | 0.23 ± 0.06D | 0.29 ± 0.08c | |

| Total | 0.18 ± 0.05A | 0.27 ± 0.10B | 0.26 ± 0.10C | 0.23 ± 0.09C | 0.22 ± 0.07D | 0.19 ± 0.05E | 0.22 ± 0.08 | |

|

Total |

T0 | 0.18 ± 0.09a | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.09a | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.18a | 0.17 ± 0.10a |

| T1 | 0.18 ± 0.05Ab | 0.28 ± 0.07B | 0.25 ± 0.12Ba | 0.23 ± 0.05B | 0.22 ± 0.06C | 0.20 ± 0.06Bb | 0.23 ± 0.08b | |

| T2 | 0.20 ± 0.05Ac | 0.39 ± 0.09B | 0.35 ± 0.10Bb | 0.31 ± 0.08B | 0.29 ± 0.10C | 0.26 ± 0.08Da | 0.30 ± 0.10c | |

| T3 | 0.24 ± 0.05Ab | 0.43 ± 0.07B | 0.38 ± 0.10Ba | 0.34 ± 0.09B | 0.34 ± 0.11C | 0.29 ± 0.09Da | 0.33 ± 0.10d | |

| Total | 0.20 ± 0.06A | 0.31 ± 0.13B | 0.29 ± 0.13B | 0.26 ± 0.10B | 0.25 ± 0.10C | 0.23 ± 0.12C | 0.26 ± 0.11 |

| AS | ACV | CXA | CX | HRA | HR | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FU | T0–T1 | 1.47 ± 0.26Aa | 2.19 ± 0.83Ba | 2.01 ± 0.49Ba | 1.71 ± 0.55Aa | 1.70 ± 0.53Aa | 1.19 ± 0.65Aa | 1.71 ± 0,64a |

| T0–T2 | 1.95 ± 0.34Ab | 2.68 ± 0.79Bb | 2.51 ± 0.46ABb | 2.19 ± 0.42Bb | 1.99 ± 0.63ABa | 1.56 ± 0.35Ca | 2.15 ± 0.63b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.75 ± 0.38Ac | 0.98 ± 0.23ABc | 0.88 ± 0.55ABc | 1.08 ± 0.15ABc | 1.01 ± 0.21ABb | 0.41 ± 0.14Bb | 0.85 ± 0.37c | |

| Total | 1.39 ± 0.59A | 1.95 ± 0.98B | 1.79 ± 0.84BC | 1.66 ± 0.61C | 1.56 ± 0.63AC | 1.06 ± 0.64D | 1.57 ± 0.78 | |

| FUS | T0–T1 | 0.37 ± 0.22A | 1.69 ± 0.88Ba | 1.73 ± 0.68Ba | 1.23 ± 0.95C | 0.32 ± 0.37A | 0.25 ± 0.15A | 0.93 ± 0.88a |

| T0–T2 | 0.78 ± 0.47A | 2.18 ± 1.02Bb | 2.08 ± 0.66Bb | 1.60 ± 0.65C | 0.75 ± 0.38A | 0.61 ± 0.36A | 1.33 ± 089b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.37 ± 0.35A | 1.05 ± 0.49Bc | 1.15 ± 0.18Bc | 0.92 ± 0.62B | 0.33 ± 0.26A | 0.28 ± 0.17A | 0.68 ± 052c | |

| Total | 0.51 ± 0.40A | 1.64 ± 0.92B | 1.65 ± 0.66B | 1.25 ± 0.78C | 0.47 ± 0.39A | 0.38 ± 0.29A | 0.98 ± 0.8 | |

| FUM | T0–T1 | 0.57 ± 0.31Aa | 2.08 ± 0.93Ba | 1.97 ± 0.66Ba | 1.33 ± 0.60Ca | 0.61 ± 0.46Aa | 0.27 ± 0.14A | 1.14 ± 0.9a |

| T0–T2 | 1.06 ± 0.40Ab | 2.40 ± 0.49Ba | 2.34 ± 0.69Ba | 1.79 ± 0.36Cb | 0.91 ± 0.60Ab | 0.64 ± 0.46A | 1.52 ± 085b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.57 ± 0.43Aa | 0.96 ± 0.32Bb | 0.91 ± 0.67Bb | 0.40 ± 0.14Bc | 0.36 ± 0.17Ba | 0.27 ± 0.10B | 0.58 ± 0.44c | |

| Total | 0.73 ± 0.44A | 1.81 ± 0.88B | 1.74 ± 0.89B | 1.17 ± 0.71C | 0.63 ± 0.49A | 0.39 ± 0.33A | 1.08 ± 0.85 | |

| CS | T0–T1 | 0.65 ± 0.31Aa | 1.82 ± 0.57Ba | 1.74 ± 0.96Ba | 1.45 ± 1.16Ca | 0.75 ± 0.32Aa | 0.67 ± 0.40Aa | 1.18 ± 0.84a |

| T0–T2 | 1.10 ± 0.31Aa | 2.16 ± 0.54Ba | 2.06 ± 0.65Ba | 1.89 ± 1.48Cb | 1.19 ± 0.28Ab | 1.16 ± 0.91Ab | 1.59 ± 090b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.40 ± 0.18Ab | 0.90 ± 0.24Bb | 0.69 ± 0.59Ab | 0.40 ± 0.32Bc | 0.40 ± 0.19Ba | 0.46 ± 0.40Ab | 0.54 ± 0.38c | |

| Total | 0.72 ± 0.39A | 1.63 ± 0.71B | 1.49 ± 0.9B | 1.25 ± 1.24C | 0.78 ± 0.42A | 0.76 ± 0.67A | 1.10 ± 0.86 | |

| VE | T0–T1 | 0.19 ± 0.11A | 1.63 ± 0.42Ba | 0.61 ± 0.54Ba | 1.23 ± 0.36Ca | 0.22 ± 0.12A | 0.18 ± 0.10A | 0.84 ± 073a |

| T0–T2 | 0.44 ± 0.23A | 1.25 ± 0.43Ba | 2.01 ± 0.29Cb | 1.79 ± 0.39Db | 0.49 ± 0.42A | 0.27 ± 0.24A | 1.04 ± 0.76b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.20 ± 0.11A | 0.94 ± 0.33Bb | 0.81 ± 0.31Bc | 0.50 ± 0.26Ac | 0.54 ± 0.29A | 0.26 ± 0.12B | 0.53 ± 036c | |

| Total | 0.27 ± 0.19A | 1.27 ± 0.48B | 1.47 ± 0.63C | 1.17 ± 0.63C | 0.42 ± 0.32A | 0.24 ± 0.17A | 0.81 ± 0.67 | |

| Total | T0–T1 | 0.65 ± 0.51A | 1.88 ± 0.75B | 1.81 ± 0.68B | 1.39 ± 0.77C | 0.72 ± 0.65A | 0.51 ± 0.31A | 1.16 ± 085a |

| T0–T2 | 1.07 ± 0.61A | 2.13 ± 0.82B | 2.20 ± 0.58B | 1.85 ± 0.78C | 1.06 ± 0.69A | 0.85 ± 0.68A | 1.53 ± 0.88b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.46 ± 0.35A | 0.97 ± 0.32B | 0.89 ± 0.50B | 0.66 ± 0.43B | 0.52 ± 0.33B | 0.34 ± 0.22B | 0.64 ± 0.43c | |

| Total | 0.72 ± 0.56A | 1.66 ± 0.83B | 1.63 ± 0.80B | 1.30 ± 0.83C | 0.77 ± 0.62D | 0.57 ± 035E | 1.11 ± 0.83 |

| AS | ACV | CXA | CX | HRA | HR | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FU | T0–T1 | -1.24 ± 0.28Aa | -1.8 ± 0.66Ba | -1.62 ± 0.57Ba | -1.45 ± 0.69Ba | -1.31 ± 0.67Ba | 0.26 ± 0.14C | -1.20 ± 0.86a |

| T0–T2 | -1.60 ± 0.53Aa | -2.38 ± 1.02Bb | -2.17 ± 0.83Cb | -1.82 ± 0.80Da | -1.33 ± 0.58Ea | 0.51 ± 0.28E | -1.46 ± 1.18b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.51 ± 0.28b | 0.69 ± 0.27c | 0.56 ± 0.37c | 0.72 ± 0.23b | 0.55 ± 0.32b | 0.69 ± 0.27 | 0.62 ± 0.29c | |

| Total | -0.77 ± 1.01A | -1.18 ± 1.53AB | -1.07 ± 1.34AB | -0.85 ± 1.29BC | -0.69 ± 1.04BC | 0.48 ± 0.29C | -0.68 ± 1.26 | |

| FUS | T0–T1 | -0.31 ± 0.27Aa | -1.31 ± 0.94Ba | -1.44 ± 0.47Ca | -1.08 ± 0.84Aa | -0.25 ± 0.40Aa | -0.21 ± 0.23Aa | -0.77 ± 0.77a |

| T0–T2 | -0.67 ± 0.53Aa | -1.85 ± 0.82Bb | -1.79 ± 0.96Ba | -1.22 ± 0.75Aa | -0.47 ± 0.42Aa | -0.54 ± 0.51Aa | -1.09 ± 0.87b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.24 ± 0.20Ab | 0.44 ± 0.26Ac | 0.79 ± 0.30Bb | 0.60 ± 0.46Ab | 0.22 ± 0.24Bb | 0.17 ± 0.13Bb | 0.41 ± 0.36c | |

| Total | -0.24 ± 0.52A | -0.90 ± 1.22B | -0.81 ± 1.32B | -0.56 ± 1.08B | -0.17 ± 0.46C | -0.19 ± 0.44C | -0.48 ± 0.95 | |

| FUM | T0–T1 | -0.33 ± 0.42Aa | -1.59 ± 1.01Ba | -1.59 ± 0.63Ba | -1.15 ± 0.71Ba | -0.47 ± 0.41Aa | -0.10 ± 0.14Aa | -0.87 ± 0.74a |

| T0–T2 | -0.92 ± 0.37Ab | -2.11 ± 0.38Bb | -2.05 ± 0.84Ba | -1.51 ± 0.44Ca | -0.51 ± 0.45Aa | -0.42 ± 0.34Aa | -1.25 ± 0.84b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.29 ± 0.25Ac | 0.66 ± 0.31Ac | 0.62 ± 0.31Ab | 0.41 ± 0.30Ab | 0.13 ± 0.09Bb | 0.23 ± 0.12Ab | 0.39 ± 0.31c | |

| Total | -0.31 ± 0.61A | -1.02 ± 1.37B | -1.01 ± 1.33B | -0.75 ± 0.98B | -0.28 ± 0.47C | -0.09 ± 0.35C | -0.58 ± 1.01 | |

| CS | T0–T1 | -0.36 ± 0.32Aa | -1.29 ± 1.01Ba | -1.21 ± 1.68Ba | -1.14 ± 0.77Ba | -0.34 ± 0.33Aa | -0.59 ± 0.56Aa | -0.82 ± 0.96a |

| T0–T2 | -0.88 ± 0.28Ab | -1.75 ± 0.54Ba | -1.88 ± 0.79Cb | -1.59 ± 1.43Ba | -0.78 ± 0.43Aa | -0.83 ± 0.77Aa | -1.28 ± 0.88b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.25 ± 0.11c | 0.52 ± 0.26b | 0.60 ± 0.47c | 0.52 ± 0.32b | 0.23 ± 0.16b | 0.36 ± 0.31b | 0.42 ± 0.32c | |

| Total | -0.33 ± 0.53A | -0.83 ± 1.19B | -0.82 ± 1.49B | -0.73 ± 1.31B | -0.29 ± 0.52C | -0.35 ± 077C | -0.56 ± 1.05 | |

| VE | T0–T1 | 0.02 ± 0.12Aa | -1.04 ± 0.47Ba | -1.30 ± 0.80Ca | -1.10 ± 0.72Ba | -0.08 ± 0.12Aa | -0.30 ± 0.35A | -0.63 ± 0.72a |

| T0–T2 | -0.40 ± 0.17Aa | -1.15 ± 0.42Ba | -1.47 ± 0.63Ca | -1.54 ± 0.62Ca | -0.45 ± 0.33Aa | -0.33 ± 0.54A | -0.89 ± 0.69b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.18 ± 0.11b | 0.47 ± 0.32b | 0.59 ± 0.31b | 0.24 ± 0.22b | 0.40 ± 0.33b | 0.08 ± 0.17 | 0.32 ± 0.27c | |

| Total | -0.06 ± 0.28A | -0.57 ± 0.85B | -0.72 ± 1.12B | -0.84 ± 0.94B | -0.04 ± 0.44C | -0.18 ± 0.41C | -0.40 ± 0.80 | |

| Total | T0–T1 | -0.44 ± 0.51Aa | -1.41 ± 0.86Ba | -1.43 ± 0.91Ba | -1.18 ± 0.73Ca | -0.49 ± 0.59Aa | -0.19 ± 0.42Da | -0.86 ± 0.75a |

| T0–T2 | -0.89 ± 0.55Ab | -1.85 ± 0.77Bb | -1.87 ± 0.80Cb | -1.54 ± 0.86Cb | -0.71 ± 0.55Ab | -0.32 ± 0.67Da | -1.20 ± 0.92b | |

| T2–T3 | 0.29 ± 0.23Ac | 0.56 ± 0.29Ac | 0.63 ± 0.35Bc | 0.50 ± 0.35Ac | 0.31 ± 0.28Ac | 0.30 ± 0.29Bb | 0.43 ± 0.33c | |

| Total | -0.34 ± 0.67A | -0.90 ± 1.25B | -0.89 ± 1.32B | -0.74 ± 1.12C | -0.29 ± 0.66A | -0.06 ± 0.56D | -0.54 ± 1.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).