Introduction

The oral cavity offers several habitats for microbial colonization, such as the saliva, teeth, tongue, gingival sulcus, palate, and other epithelial surfaces of the oral mucosa [

1]. The knowledge of oral microbiome has sharply increased after the development of culture-independent study methods, such as 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene community profiling, which revolutionized the detection and identification of microorganisms in the oral microbiome [

2]. The oral microbiome mainly consists of bacteria, fungi, and viruses; archaea and protozoa are present in lower proportions [

3]. Over 700 bacterial species have been identified, making the oral microbiota the second most diverse microbiota in humans.

Streptococcus is the genus found in greatest quantity in the microbiome of adult subjects, followed by

Gemella, Veillonella, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Neisseria, Capnocytophaga, Corynebacterium and

Actinomyces [

4]. The bacteria of the oral microbiota form the dental plaque biofilm, embedded in an extracellular matrix at the interface between the tooth surface and saliva or Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) [

5]. A balanced and stable state of microbiota (symbiosis) is essential for maintaining oral health [

6]. Changes in the oral environment and the interference of certain low-abundance microbial pathogens with the host immune system may alter the diversity and relative proportions of species or taxa within the microbiota, leading to the overgrowth of pathogenic species. Consequently, the lack of stability and the disequilibrium state of the oral microbiota (dysbiosis), lead to conditions such as caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis [

7], which are among the most prevalent diseases globally [

8].

A proper oral hygiene is essential to favor the symbiosis of the oral microbiota. The ability and willingness of users to maintain plaque control is the foundation for the prevention and treatment of oral diseases [

9]. Toothbrushing is the mainstay of oral hygiene, although several procedures are available for the mechanical removal of the plaque [

10], such as interdental cleaning devices (dental floss, interdental brushes, oral irrigators, woodsticks [

11]) and scaling [

12]. Manual- and battery-powered toothbrushes have been shown to effectively reduce the amount of dental plaque [

13]. Proper use and storage of toothbrushes are crucial to avoid gingival recession and contamination from several sources (oral cavity, environment, hands, aerosols, blood, skin, and containers).

Toothpastes, mouthwashes, gels [

14], or sprays [

15] are used as adjuvants for conventional tooth brushing. These products may contain ingredients with antimicrobial action (e.g., chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride, fluorides, and natural substances) that exert anti-plaque and/or anti-gingivitis and anti-periodontitis actions [

16]. Oral cleansing products should not abrade the tooth enamel or alter its color [

17]. Moreover, they should be accepted by the user (flavor, texture, and feeling of freshness).

Recently, interest in probiotic supplementation for the prevention and treatment of oral diseases has emerged. Supplementation with viable microorganisms favors the symbiosis of oral microbiota [

18] and has shown promising results in reducing dental plaques and the risks of caries [

19], improving periodontal clinical parameters [

20]. Products based on

Lactobacillus plantarum demonstrated beneficial effects on the oral microbiota in preclinical studies [

21,

22] and in a randomized clinical trial [

23].

A complete line of cosmetic products (“

tau-marin® Protezione e Prevenzione”) with the innovative formulation containing a prebiotic (Bioecolia

®) [

24] and a paraprobiotic based on

Lactobacillus plantarum (Symreboot

TM OC) [

25]was launched in the Italian market in 2023. The products were the toothpastes "

Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta Delicata” and "

Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta" and the mouthwash "

Collutorio tau-marin® Menta.” The cosmetic manufacturer (Biokosmes S.r.l., Lecco, Italy) recommends the use of the above-mentioned products with a toothbrush "

Spazzolino tau-marin®", which can eliminate

Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA),

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Escherichia coli bacteria thanks to the silver ions [

26] placed on the bristles, handle and toothbrush head [

27]. Bioecolia

® is an alpha-glucan-oligosaccharide that constitutes a preferential substrate for commensal bacteria and selectively stimulates their growth. Symreboot

TM OC belongs to the class of paraprobiotics, non-viable microbial cells (either intact or broken), or crude cell extracts, which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the user [

28]. Symreboot

TM OC consists of heat-treated

Lactobacillus plantarum HEAL19. Preclinical studies have shown that Symreboot

TM OC favors the expression of antimicrobial peptides, soothes the oral cavity, and promotes a healthy oral microbiota. Moreover, Symreboot

TM OC supports the production of filaggrin, a protein that facilitates the aggregation of keratin filaments [

29], thus strengthening the oral mucosa barrier. The combined action of prebiotics and paraprobiotics restored symbiosis. The stability and preclinical tests confirmed the safety of these products.

Aim of the Study

The aim of this pilot study was to provide preliminary clinical data (efficacy on plaque and gingival sensitivity, safety and tolerability of the products), the recruitment monthly rate, and patient acceptability as well as descriptive data on the effects of the products on oral microbiota rebalancing. The data obtained from this study will form the basis of a future larger confirmatory study on the feasibility of a standard daily hygiene model, including the use of toothpaste, mouthwash, and toothbrush marketed with the claim of improving oral prevention and protection.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a 28-days interventional, randomized, prospective, open-label, parallel-group study on 84 healthy volunteers who did not perform proper oral hygiene. All subjects who had a routine dental visit at the author DC's private dental clinic in Pavia (Italy) between May and July 2022 were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria and evaluated for oral hygiene compliance. Only subjects who signed the informed consent form could potentially be included in the study and were first interviewed about their oral health habits, including frequency of toothbrushing (score 0: more than once a day, 1: once a day, not every day), self-diagnosis of oral malodor awareness (score 0, rarely or never self-conscious; 1, sometimes; 2, often), and self-assessment of subjects’ compliance with regular oral hygiene (score 0: optimal, 1: mild, 2: bad). The total score should be 4 or higher. In addition, the Simplified Oral Hygiene Index (OHI-S) proposed by Greene and Vermillion [

30] was applied. A score ≥ 2 was necessary for inclusion in the trial. Patients who met the eligibility criteria (

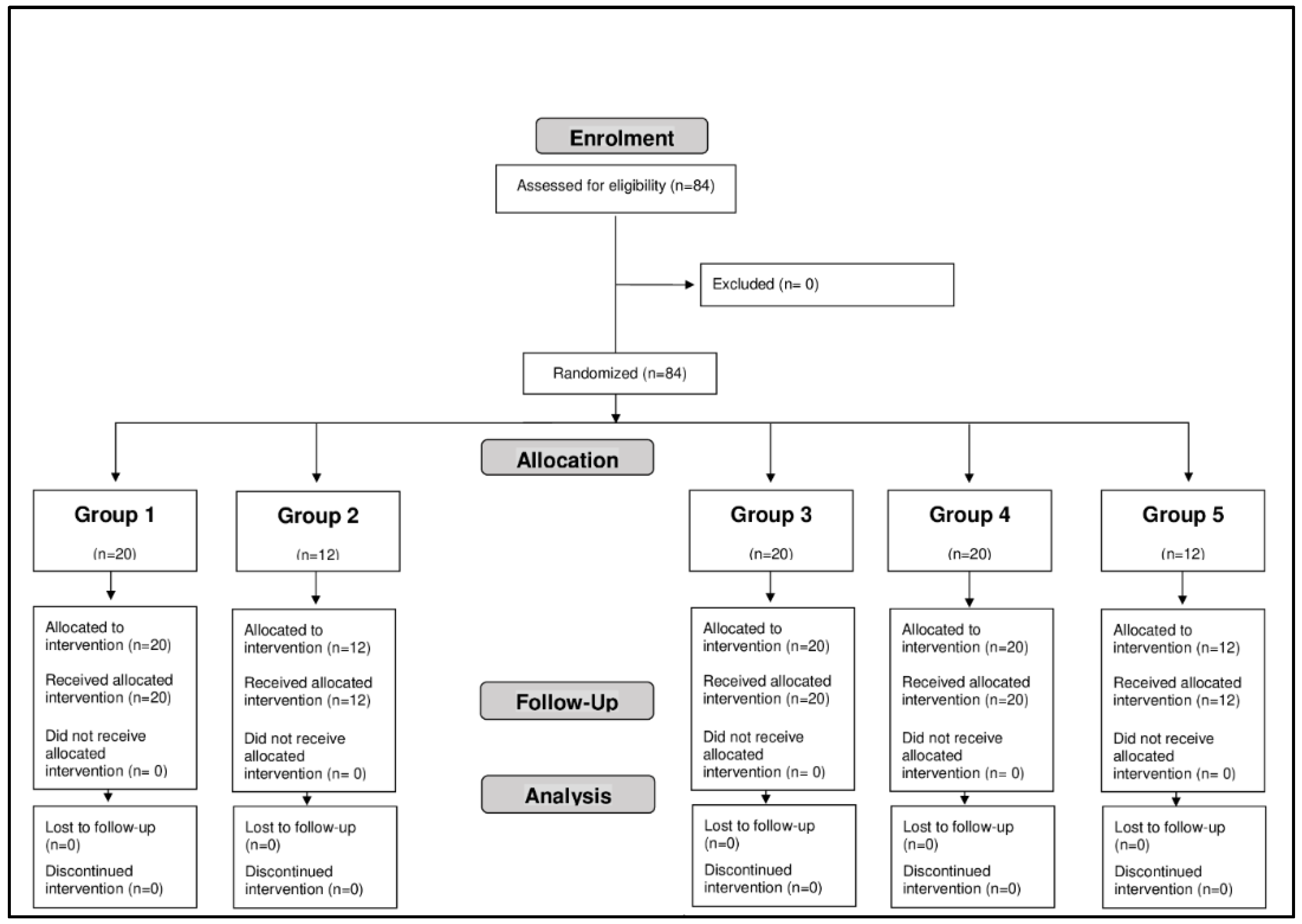

Table 1) and assured that they would not change their daily routine or lifestyle during the study period were enrolled. When recruiting a patient in his private clinic in Pavia, the investigator should call the central randomization service located at the Complife Italia Clinical Center (San Martino Siccomario, Pavia, Italy), which should obtain basic patient information and then assign treatment following a computer-generated list. The patients were allocated to one of the following groups: Group 1 (20 subjects) used the delicate mint toothpaste "

Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta Delicata"; Group 2 (12 subjects) mint toothpaste "

Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta"; Group 3 (20 subjects) mint mouthwash "

Collutorio tau-marin® Menta". The 20 subjects of Group 4 utilized delicate mint toothpaste "

Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta Delicata" and mint mouthwash "

Collutorio tau-marin® Menta". These products were applied with tau-marin

® scalar toothbrush 33 medium with antibacterial

"Spazzolino tau-marin®" three times a day after the main meals for 28 days. Group 5 (12 subjects) continued to use routine oral hygiene products for 28 days. Groups 1 to 3 were provided with a standard toothbrush (without any claims of efficacy) to be used three times a day after the main meals for 28 days. As this was a pilot study, and for logistical reasons, the size of the treatment groups was not equal; thus, the reduced number of subjects included in the mint toothpaste group was only used to verify the effect of sugar concentration compared to the mild mint product, and the 12 subjects in the control group were included in the study only to assess the variations in oral microbiota. It should be noted that no patients, nor Investigator were blinded to the treatment they were allocated. The screening visit was performed at the Investigator's private dental clinic in Pavia, while the patients underwent the examinations required by the study protocol at the Complife Italia Clinical Center (T0 visit). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as amended by the 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013) and following Italian regulations on clinical trials on cosmetics. The reporting of the study conforms to the CONSORT pilot and feasibility trials checklist [

31]. The protocol was approved by the Internal Ethics Committee (IEC) of Complife Italia, the institute involved, with #05 on April 29, 2022. The study protocol was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov at NCT05999175. The first subject was enrolled on May 17, 2022, the end of enrolment period was on June 28, 2022. and the last subject’s last visit was performed on July 26, 2022. The tested products were provided by Biokosmes S.r.l. (Lecco, Italy).

Data Collection Specifications and Time Points

The clinical data required by the study protocol were collected immediately before the use of the product (T0), and after 14 (T14) and 28 (T28) days. Visits were performed at least 4 h after the subject's last oral activity (eating, drinking, brushing teeth, etc.). An additional visit was made immediately after the first use of the products (Timm) to test the dental plaque and complete the self-assessment questionnaire.

The following data were collected at the planned time points:

The presence of caries and/or tartar and gingival recession evaluated at T0 by clinical assessment (yes = presence; no = absence).

Dental plaque assessed at T0 (three hours after the last tooth brushing) and Timm using a disclosing tablet based on erythrosine. The total plaque score [

30] was calculated by summing the tooth surface area scored (0-3 = excellent; 4-7 = good; 8-11 = fairly good; 12-18 = poor).

Gum sensitivity evaluated at T0, T14 and T28 using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 0 = no sensitivity - 10 = highest sensitivity).

Rising of gingival lesions or irritations (reddening, burning sensation, swelling, bleeding) and rising of ulcers, lesions of the oral mucosa assessed at T0, T14, and T28 by clinical assessment (yes = rising; no = absence of rising).

Teeth color evaluated at T0 and T28 using the VITAPAN® scale (four families of shades: reddish-brownish A1, A2, A3, A3.5, A4, reddish-yellowish B1, B2, B3, B4, greyish C1, C2, C3, C4, and reddish-grey D2, D3, D4).

Oral microbiota. Twelve subjects belonging to Groups 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were selected according to a randomization list. Their samples were collected and analyzed by the Laboratory of Genomics & Transcriptomics, Center for Translational Research on Autoimmune and Allergic Disease (CAAD) and Department of Health Sciences, University of Piemonte Orientale (Novara, Italy) at T0 and T28 by metagenomic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene. Microbiota was collected by brushing the oral mucosa surface with a swab. Bacterial DNA was isolated from the components of the sample, purified, and subjected to 16S rRNA gene amplification. Analysis was completed by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene pool using bioinformatics tools. The influence of the treatment on diversity within the samples (alpha-diversity) was evaluated using the biodiversity index (Shannon index) [

31]. Beta-diversity analysis was used to compare the composition of microbial communities between groups by generating a dissimilarity matrix.

Self-assessment questionnaire filled in by the participants at Timm, T14, and T28 to evaluate the opinion on the tested products focused on the self-perceived efficacy and sensory properties of the products. Data were expressed as the percentage of participants who gave the same opinion as those proposed. Positive answers corresponded to the percentage of participants who provided positive judgments.

The participants were also provided with a diary in which they recorded product applications, study deviations, and adverse events (AEs). Participants were instructed to discontinue the use of the products and contact the Investigator immediately if undesirable side effects/ì or discomfort occurred. The study schedule is shown in

Table 2.

Study Outcomes

The study outcomes were gum sensitivity, dental plaque reduction, recruitment monthly rate, oral microbiota analysis, patient satisfaction on the tested products, tolerability, and tooth color. AEs were described by the participants in the diary.

Statistical Analysis

We planned to include a minimum of 12 participants per group. Given the descriptive nature of this pilot study, neither intergroup comparison nor a formal estimate of the sample size was planned. The data were analyzed and interpreted using both descriptive and inferential statistical analysis procedures. Statistical analysis was performed using the NCSS 10 Statistical Software (2015) (NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA,

https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca). Intragroup variations in gum sensitivity and dental plaque were analyzed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical significance was set at p value <0.05. For the clinical evaluations, a positive effect of the product on the evaluated parameter was confirmed if more than 50% of the participants registered an improvement. The sensation of effective cleaning and agreeability of the products were considered positive if perceived in this way by at least 60% of the participants. Regarding the oral microbiota analysis, the Shannon index and statistics were calculated using the Microbiome Analyst software (Xia Lab @ McGill,

https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca).

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Eighty-four subjects, 20 males and 64 females, aged between 18 and 64 years, participated in the study (

Figure 1).

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the subjects at baseline.

Gum Sensitivity

The use of the products/treatment resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the VAS score of gum sensitivity at both T14 and T28 compared to the baseline in each study group, as shown in

Table 4. The study protocol did not include any comparisons between the groups.

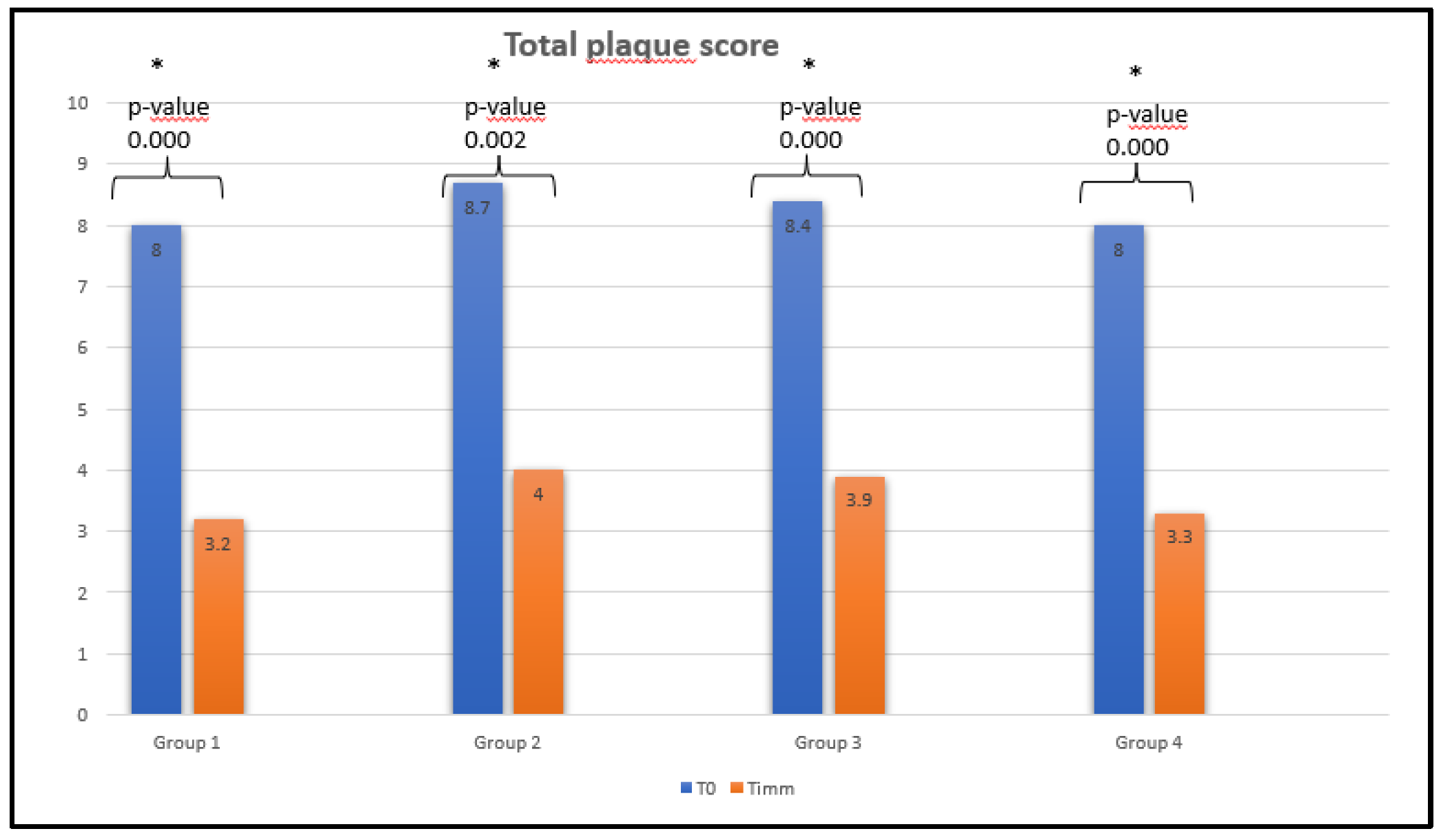

Dental Plaque

Each group showed a statistically significant decrease in dental plaque immediately after the first use of the products (

Figure 2).

Recruitment Monthly Rate

Participants were recruited from May 17th, 2022 to June 28th, 2022; July 26th, 2022 was the date for the last visit of the last patient. Therefore, the enrolment rate was 14 patients/week. This value was coherent with the monthly site recruitment rate planned for the main future RCT (between 40 and 45 patients/month/site). It must be emphasized that the result was obtained in standard practice without any advertising.

Oral Microbiota

Microbiota Composition

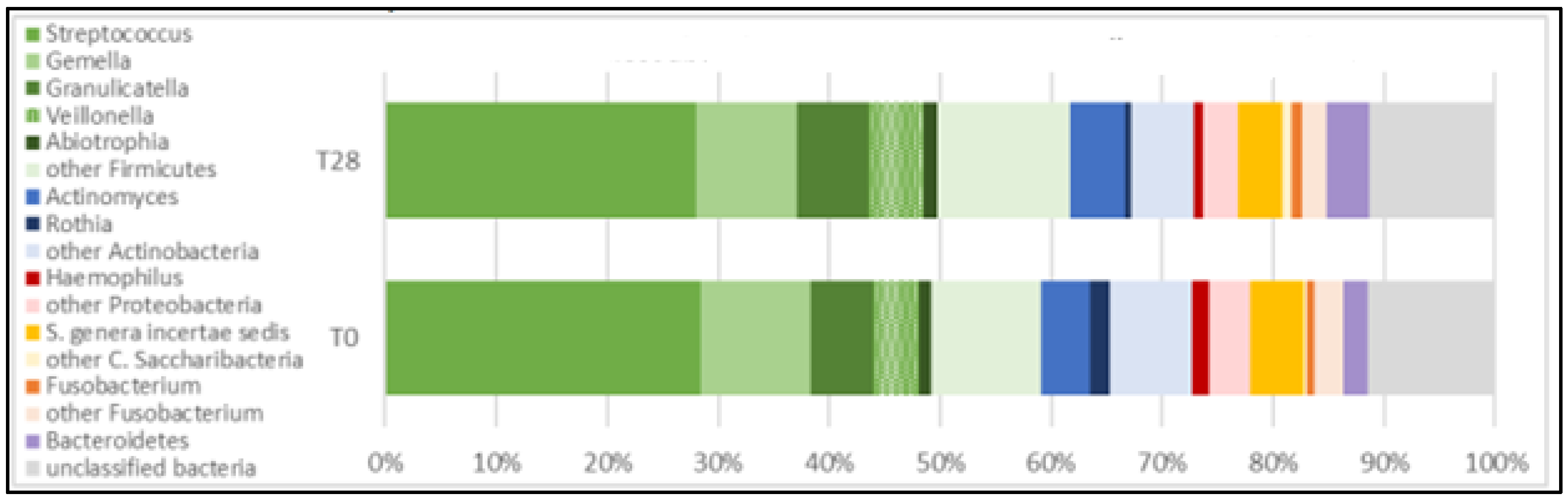

Six phyla, 12 classes, 15 orders, 23 families, and 37 genera were detected in the oral microbiota of participants in the five groups.

Firmicutes (greens),

Actinobacteria (blues),

Saccharibacteria (yellows),

Proteobacteria (reds), and

Fusobacteria (oranges) accounted for over 80% of all phyla present in the oral microbiota of participants examined. Firmicutes exhibited the highest relative abundance over time. The abundance profiles of the ten most represented genera confirmed the trends observed for the phyla. Genera belonging to

Firmicutes (

Streptococcus, Gemella, Granulicatella, Veillonella, Abiotrophia) were the highest abundant, followed by

Actinobacteria (

Actinomyces and Rothia),

Protebacteria (

Haemophilus),

Candidatus Saccharibacteria and

Fusobacteria (

Fusobacterium), as shown in

Figure 3.

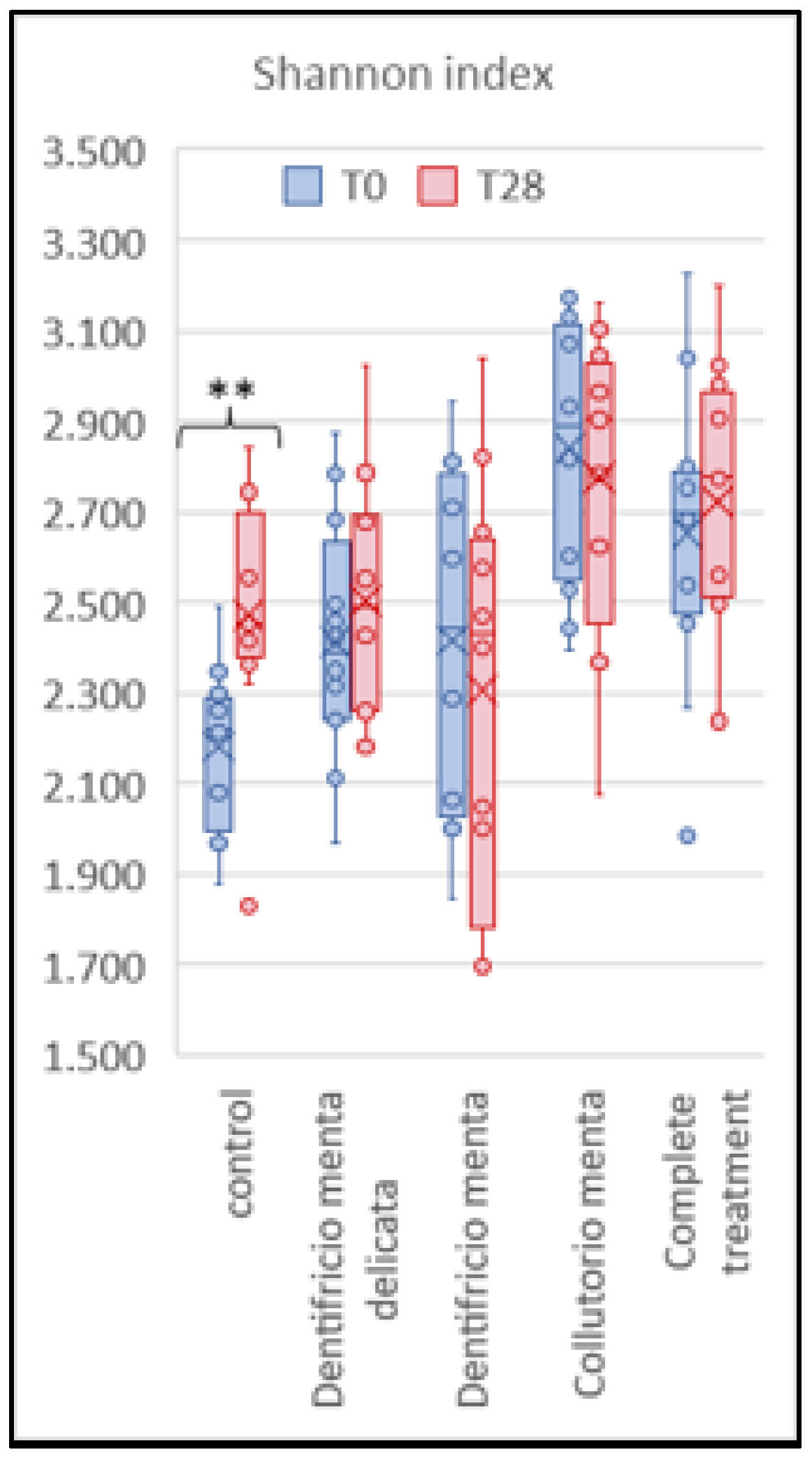

Influence of Treatment on Biodiversity

Alphadiversity

The box plot in

Figure 4 shows a relevant variation in alphadiversity for the control patients (group 5: P<0.01), while all treated groups were statistically stable over time (group 1, P<0.44; group 2, P<0.44; group 3, P<0.62; and group 4, P<0.58).

Betadiversity

The oral microbiota composition of the treated groups was similar before and after the product use and treatment. Small variations over time were observed in Groups 1 and 2, and almost none in Groups 3 and 4. Significant differences in terms of taxa richness, abundance, and bacterial composition of the microbiota were detected in Group 5 (

Table 5).

Self-Assessment Questionnaire

Globally, participants in all groups positively evaluated the test items in the self-assessment of the tested products. The percentage of positive answers ranged from 70.0% to 100.0% at the different time points.

Table 6 displays the answers to a selection of questions (visit T28).

Product Tolerability

The tested products showed good tolerability for all the participants. No adverse reactions or AEs occurred during the study period.

Teeth Color

The tested products did not show a variation in tooth color after 28 days of use compared with the baseline.

Discussion

This pilot study, according to the Ashanti proverb that "no one tests the depth of a river with both feet,"[

32] was planned to avoid starting the future pragmatic clinical trial with unresolved critical logistical issues or potential bias in the selection of endpoints. The data collected on recruitment capability (14 patients/week/site) and study procedures allowed a realistic estimation of time and will be used for the budget calculation of the main study. The extremely positive evaluation of the tested products by the subjects in the self-assessment questionnaire is also a promising factor for the future study: in clinical trials, good patient satisfaction with the tested product is associated with a low dropout rate.

This pilot study showed that the use of the tested products induced a significant reduction in plaque immediately after their use in oral hygiene practices. The magnitude of this result appears almost superimposable for all the products. However, without comparison with the performance obtained in the control group, it cannot be determined how much is attributable to the individual products (delicate mint toothpaste, mint toothpaste, and mint mouthwash) versus when it results from the physical action of the toothbrush. This bias will be eliminated in the future large-population clinical trial, which should also allow the identification of the possible adjuvant action of the products under study.

Figure 4 shows that for alphadiversity, only untreated subjects (those with inadequate oral hygiene) showed a significant increase in the number of taxa from T0 to T28. In addition,

Table 5 shows the divergent trend in betadiversity between the treated and untreated patients from T0 to T28. In fact, the bacterial composition of the oral microbiota composition showed a significant difference in the control group (group 1, P<0.00), while in the other patients (groups 1, 2, 3, and 4), it appeared very similar before and after treatment. These trends support a possible correlation between proper oral hygiene and the stability of the oral microbiota.

The population enrolled in the study had a history of poor oral hygiene, but no periodontal disease. The medical literature has demonstrated the beneficial effects of different types of toothpaste and mouthwash on the oral microbiota [

33,

34,

35,

36] in patients with periodontal disease or removable partial dentures. Chhaliyil et al. [

37] introduced the concept of “frequent biofilm disruption” to improve oral hygiene; the cleansing protocol proposed included the use of index finger to clean the teeth (Gum and Tooth Rubbing with Index Finger Tongue Cleaning and Water Swishing, GIFT) proved to be difficult to follow for an adequate period. An alternative approach may be frequent brushing and thus frequent biofilm disruption using a mildly flavored toothpaste, such as delicate mint toothpaste, combined with frequent brushing (with mint mouthwash) when brushing is difficult, such as at the workplace or during outdoor activities. This could be a pragmatic and effective strategy, even in the long term, given the positive feedback obtained from our study. The reduction in gum sensitivity observed during the study control visits was consistent with the effective plaque removal. Finally, user acceptance is particularly important because it ensures continuity in oral hygiene practices.

The limitations of our study are related to its descriptive nature; therefore, no comparisons were made between products. However, considering that the tested products should act in a preventive rather than curative approach, the results are of particular interest, demonstrating efficacy in the removal of plaque and in the stabilization of the microbiota. Despite the limitations of the small sample size examined and the consequent descriptive method used for the analysis, the main value of our study is the finding of no variability between baseline and final data in the population that was treated with the products under test. This suggests that the description of substantial stabilization of the microbiota as a result of the use of cleaning methods by a population of non-pathological subjects may emerge as a final consideration of this study.

Conclusion

This study shows that regular oral hygiene with delicate mint toothpaste "Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta Delicata", mint toothpaste " Dentifricio gel tau-marin® Menta", mint mouthwash "Collutorio tau-marin® Menta", and scalar toothbrush "Spazzolino tau-marin®"reduces plaque, promotes symbiosis, and stabilizes the oral microbiota, thus helping to prevent clinical inflammatory conditions. These results, in addition to the proven stabilization of the microbiota, are reasonably related to the specific formulation of the tested products and are in line with previous literature reports on prebiotics (Bioecolia®) and paraprobiotics (SymrebootTM OC), which are the defining elements of the “tau-marin® Protezione e Prevenzione” line of cosmetic products. We believe that a pragmatic clinical trial in a real-world setting could be successfully planned to compare the tested products with alternative hygiene strategies and with other products for the protection and prevention of the oral mucosa. Obviously, an adequate sample size larger than the population enrolled in our study would be needed.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization, VN; methodology, DC; formal analysis, VN, DFB, and SR; investigation, DC, VN, and MM; writing-original draft preparation, SR, SB, VN, and DFB; writing-review and editing, VN, SB, and DFB; visualization, PB; supervision, SR and VN; project administration, DFB and PB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interests

SR, SB, VN, MM, and DC declare no conflicts of interest. DFB is employed at Opera CRO, the Contract Research Organization that analyzed the study; PB is employed at Alfasigma SpA, the Responsible Person of the tested products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. The full protocol can be requested from the authors.

Funding

A grant support was received from Biokosmes S.r.l., Lecco - Italy (

https://biokosmes.it). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, or in the decision to submit the study results for publication.

Acknowledgments

This is the version of the article as submitted to the journal “General Dentistry” on December 11, 2023. Special thanks to Diana Koprivec, Dr. MD, PhD, for her valuable feedback throughout the project.

References

- 1. Costalonga M, Herzberg MC. The oral microbiome and the immunobiology of periodontal disease and caries. Immunol Lett, 2: Pt A). [CrossRef]

- 2. Willis JR, Gabaldon T. The Human Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease: From Sequences to Ecosystems. Microorganisms. [CrossRef]

- 3. Radaic A, Kapila YL. The oralome and its dysbiosis: New insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. [CrossRef]

- 4. Sedghi L, DiMassa V, Harrington A, Lynch SV, Kapila YL. The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontol 2000. [CrossRef]

- Valm, AM. The Structure of Dental Plaque Microbial Communities in the Transition from Health to Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease. J Mol Biol, 2: 2019;431(16), 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6. Abdulkareem AA, Al-Taweel FB, Al-Sharqi AJB, Gul SS, Sha A, Chapple ILC. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: from symbiosis to dysbiosis. J Oral Microbiol, 7779. [CrossRef]

- 7. Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, et al. The oral microbiome - an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J. [CrossRef]

- 8. Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet, 1019. [CrossRef]

- 9. Carra MC, Detzen L, Kitzmann J, Woelber JP, Ramseier CA, Bouchard P. Promoting behavioural changes to improve oral hygiene in patients with periodontal diseases: A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol, 7: 22. [CrossRef]

- 10. Toshniwal SH, Reche A, Bajaj P, Maloo LM. Status Quo in Mechanical Plaque Control Then and Now: A Review. Cureus, 2861. [CrossRef]

- 11. Amarasena N, Gnanamanickam ES, Miller J. Effects of interdental cleaning devices in preventing dental caries and periodontal diseases: a scoping review. Aust Dent J. [CrossRef]

- 12. Zhang X, Hu Z, Zhu X, Li W, Chen J. Treating periodontitis-a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing ultrasonic and manual subgingival scaling at different probing pocket depths. BMC Oral Health. [CrossRef]

- 13. Salzer S, Graetz C, Dorfer CE, Slot DE, Van der Weijden FA. Contemporary practices for mechanical oral hygiene to prevent periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. [CrossRef]

- 14. Fatima F, Taha Mahmood H, Fida M, Hoshang Sukhia R. Effectiveness of antimicrobial gels on gingivitis during fixed orthodontic treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthod. [CrossRef]

- 15. Zhang J, Ab Malik N, McGrath C, Lam O. The effect of antiseptic oral sprays on dental plaque and gingival inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. [CrossRef]

- 16. Rajendiran Meenakshi TH, Chen Dandan , Gajendrareddy Praveen , Chen Lin. Recent Development of Active Ingredients in Mouthwashes and Toothpastes for Periodontal Diseases. Molecules. [CrossRef]

- 17. Aspinall SR, Parker JK, Khutoryanskiy VV. Oral care product formulations, properties and challenges. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces, 1115. [CrossRef]

- 18. Patel RM, Denning PW. Therapeutic use of prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics to prevent necrotizing enterocolitis: what is the current evidence? Clin Perinatol. [CrossRef]

- 19. Sivamaruthi BS, Kesika P, Chaiyasut C. A Review of the Role of Probiotic Supplementation in Dental Caries. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins, 1300. [CrossRef]

- 20. Gheisary Z, Mahmood R, Harri Shivanantham A, et al. The Clinical, Microbiological, and Immunological Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- Kistler J PM, Goetz M, Wade W. The Effect of Probiotic Treatments on the Composition of In-Vitro Oral Biofilms. presented at: IADR/AADR/CADR General Session; , 2017 2017; San Francisco, CA. Accessed July 5, 2023. https://iadr.abstractarchives. 25 March 2629.

- 22. Schmitter T, Fiebich BL, Fischer JT, et al. Ex vivo anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics for periodontal health. J Oral Microbiol, 5020. [CrossRef]

- 23. Volgenant CMC, van der Waal SV, Brandt BW, et al. The Evaluation of the Effects of Two Probiotic Strains on the Oral Ecosystem: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Front Oral Health. [CrossRef]

- Bioecolia®. Solabia Group. Accessed , 2023. https://www.solabia.com/ww/Produto_4,1/Cosmetics/Bioecolia. 5 July.

- Symrise launches SymReboot™ OC, its first processed probiotic dedicated to oral care. Symrise. Updated , 2021. Accessed July 5, 2023. https://www.symrise. 7 August.

- 26. Talapko J, Matijevic T, Juzbasic M, Antolovic-Pozgain A, Skrlec I. Antibacterial Activity of Silver and Its Application in Dentistry, Cardiology and Dermatology. Microorganisms. [CrossRef]

- Protezione antibatterica. tau-marin. Accessed July, 5, 2023. https://www.tau-marin.

- 28. Siciliano RA, Reale A, Mazzeo MF, Morandi S, Silvetti T, Brasca M. Paraprobiotics: A New Perspective for Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- 29. De Benedetto A, Qualia CM, Baroody FM, Beck LA. Filaggrin expression in oral, nasal, and esophageal mucosa. J Invest Dermatol, 1594. [CrossRef]

- 30. Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. J Am Dent Assoc. [CrossRef]

- Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, Lancaster GA; PAFS consensus group. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016 Oct 21;2:64. [CrossRef]

- 32. Lahti L BT, Eckermann H, Shetty S, Ernst FGM. Orchestrating Microbiome Analysis with R and Bioconductor, /: , 2023. https, 5 July 2023.

- Proverb resources: ashanti proverbs from ghana in: http://cogweb.ucla.edu/Discourse/Proverbs/Ashanti. 1 August 2023.

- 34. Silin AV SE, Reutskaya KV. Otsenka éffektivnosti zubnoĭ pasty Parodontax u patsientov, nakhodiashchikhsia na ortodonticheskom lechenii [Effectiveness of Paradontax toothpaste in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment]. Stomatologiia (Mosk). [CrossRef]

- 35. Precheur I, Rolland Y, Hasseine L, Orange F, Morisot A, Landreau A. Solidago virgaurea L. Plant Extract Targeted Against Candida albicans to Reduce Oral Microbial Biomass: a Double Blind Randomized Trial on Healthy Adults. Antibiotics (Basel). [CrossRef]

- 36. Saeed MA KA, Faridi MA, Makhdoom G. . Effectiveness of propolis in maintaining oral health: a scoping review. Can J Dent Hyg.

- 37. Wiatrak K, Morawiec T, Roj R, et al. Evaluation of Effectiveness of a Toothpaste Containing Tea Tree Oil and Ethanolic Extract of Propolis on the Improvement of Oral Health in Patients Using Removable Partial Dentures. Molecules. [CrossRef]

- 38. Chhaliyil P, Fischer KF, Schoel B, Chhalliyil P. A Novel, Simple, Frequent Oral Cleaning Method Reduces Damaging Bacteria in the Dental Microbiota. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).