1. Introduction

In modern orthodontics, fixed appliance therapy is a crucial component. Even though orthodontic treatment has many advantages for the patient, fixed appliances can harm the dentition and supporting tissues if proper and consistent oral hygiene is not maintained [

1].

The primary cause of tooth demineralization and the development of cavities is plaque buildup and retention in the vicinity of fixed orthodontic appliance [

2]. Plaque retention can be managed in a variety of ways, including brushing teeth and using mouthwashes containing fluoride and chlorhexidine. However, because it is a chemical substance, it typically has negative consequences like dry mouth and tooth discoloration [

3,

4]. Antibiotics, antimicrobial medication with chlorhexidine, fluoride, and other biological techniques are typically employed to manage plaque. At the moment, these techniques can reduce the caries infection but never completely eradicate it [

5].

Probiotics are good microorganisms that can help the host's micro-ecological balance [

6] .The Food Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization described it as live microorganisms that, when given in sufficient quantities (in food or as a dietary supplement), promote the host's health by enhancing the digestive tract's microbiological balance [

7]. Although probiotics have long been employed in fermented foods, its promise as a nutritional therapy has just lately been officially recognized [

8].

The majority of probiotic bacteria are found in yoghurt products and probiotic drinks, and they are classified under the genera Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium. According to recent research, probiotics improve oral health and have the ability to modify the protein makeup of dental plaque, which in turn can impact the oral micro-ecology [

9]. Research on the anti-plaque and anti-caries effects of probiotics has increased as a result of this [

10].

Lactobacilli probiotics produce antifungal compounds such as fatty acids and bactriocins, which exhibit bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects, along with antimicrobial agents including organic acids and hydrogen peroxide [

11,

12] assert that

S. mutans is the most recognized pathogenic bacterium responsible for dental caries due to its acidogenicity, aciduric characteristics, and ability to generate an extracellular matrix that is the fundamental component of dental plaques and biofilms [

13].While numerous research on the use of probiotics have shown that Lactobacillus inhibits

S. mutans in dental plaque, there aren't many that compare the use of probiotics with chemical mouthwashes like Orth Kin and Corsodyl over the same time period. We believe that prolonged usage of probiotics produces superior benefits than the two chemical mouthwashes (Corsodyl and Orthokin). This study aims to compare the efficacy of Orthkin and Corsodyl mouthwashes with probiotic mouthwashes on

S. mutans and

Lactobacillus spp in the oral cavity by counting the number of bacterial colonies and measuring the pH of saliva.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

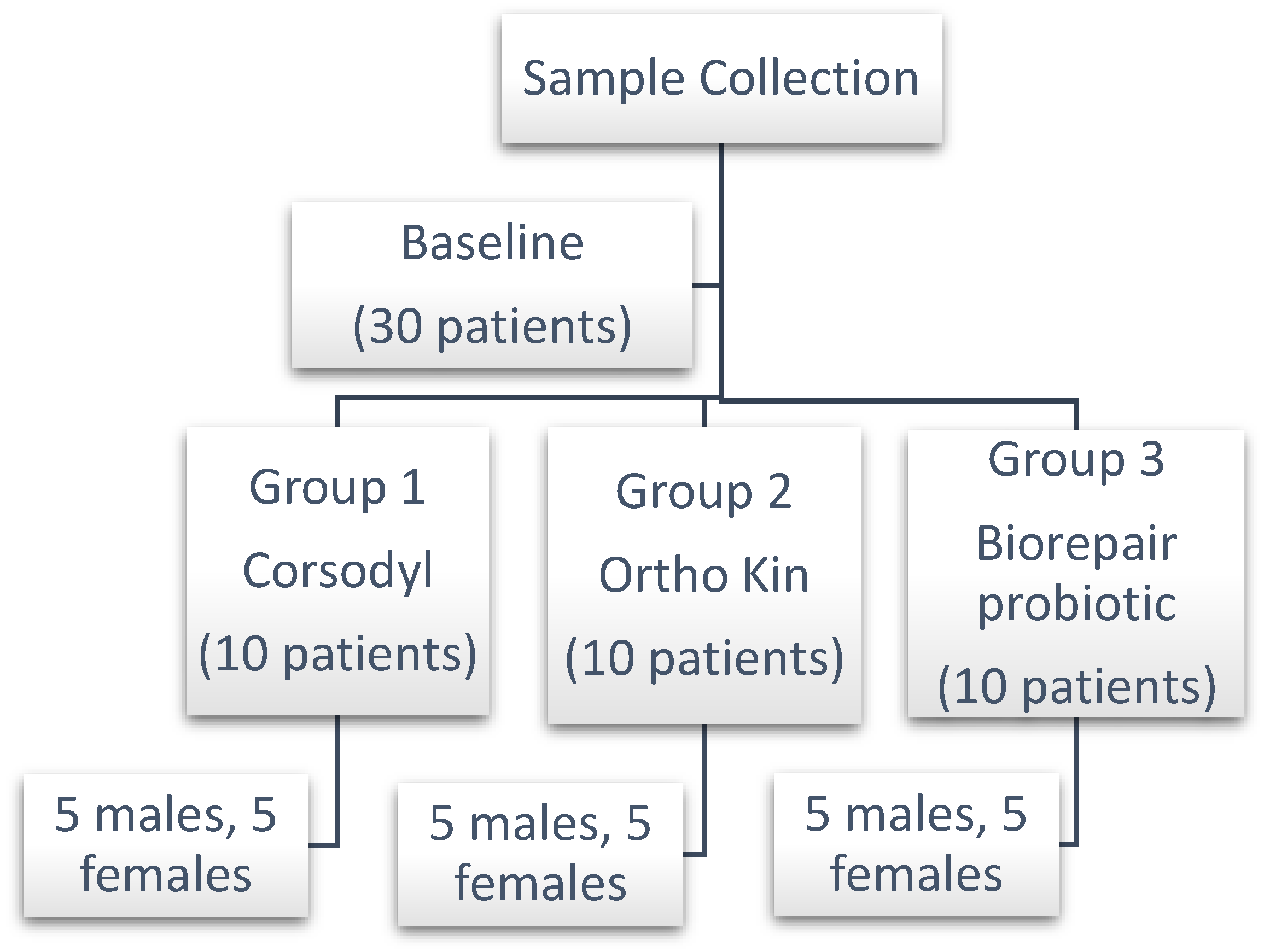

At the private orthodontic clinic in Baghdad, Iraq, 30 patients (15 males and 15 female) between the ages of 14 and 21 who were receiving treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances, the goal of the study was explained to the participants, and informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Ethical approval for this study (Ethical Committee No. 5) was provided by the Ethical Committee in collage of dentistry, Dijlah university, Baghdad, Iraq, on 17 October 2024.

The following criteria were used to select patients: the patient had to have a complete permanent dentition, be free of caries, systemic diseases, or allergic conditions, brush their teeth twice a day, and not have taken any medication, including corticosteroids or systemic antibiotics, for at least four weeks prior to the study. The materials utilized were Corsodyl mouthwash (containing chlorhexidine, Germany), Orthokin mouthwash (containing fluoride, Spain), and Biorepair probiotic mouthwash (Italy)

Figure 1.

Following the manufacturer's recommendations, the patients were told to use the mouthwash after cleaning their teeth. The samples were split up into three groups, and each group received three different treatment times: baseline, two weeks later, and one month later (each group had 10 patients) as in

Figure 2. Ortho Kin mouthwash was used by Group 1, Corsodyl mouthwash by Group 2, and Biorepair probiotic mouthwash by Group 3 (10 patients). At least an hour after the meal, between 4-5 pm, salivary and plaque samples were collected. Using a sterile instrument, a swab was taken between the orthodontic brackets on the buccal and labial surfaces of the upper teeth close to the bracket base in order to capture the plaque, while for saliva collection, 2 ml was collected then both samples added into a separated sterile, plastic capped tube with a normal saline to have tenfold dilutions and transferred to the microbiology laboratory.

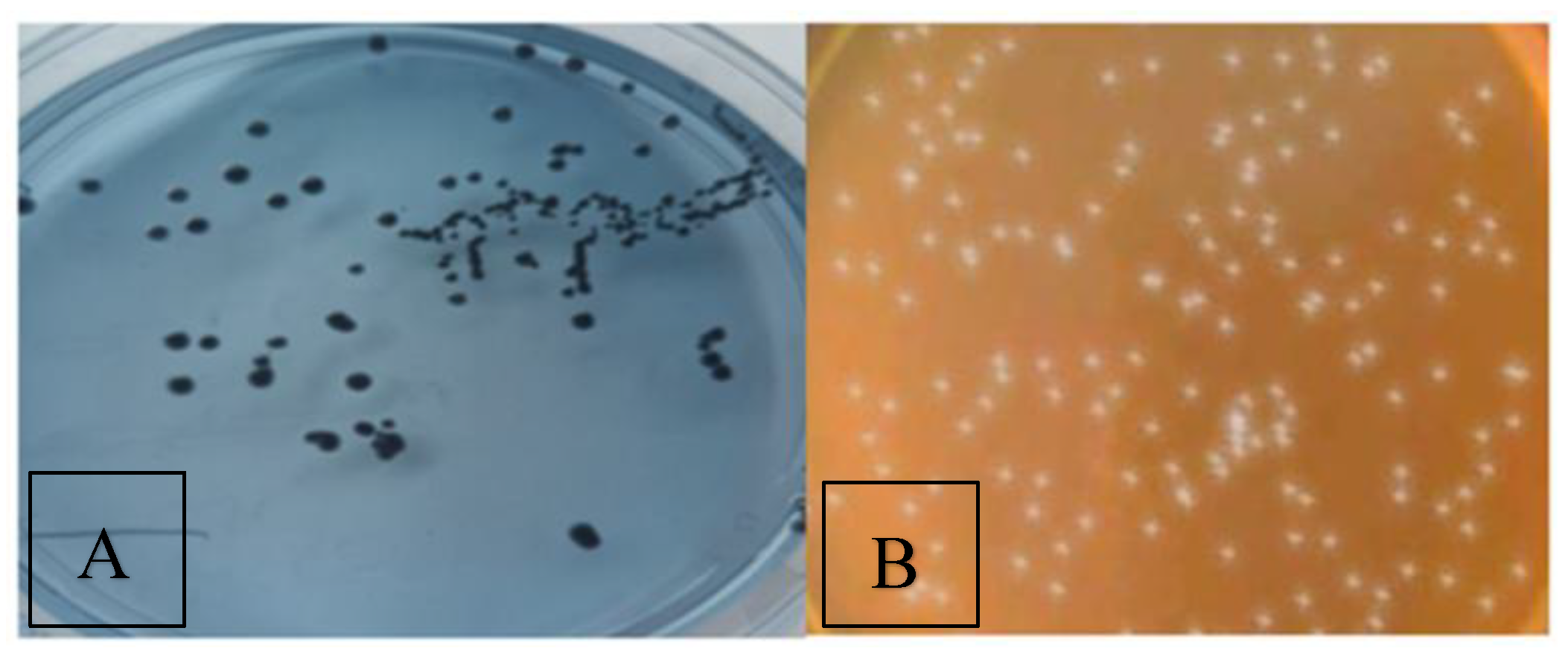

2.2. Assessment of S. mutans and Lactobacillus spp Colony Counts

For the purpose of full colony counting of related microorganisms (S. mutans and Lactobacillus spp), the special selective media were used (Mitis-Salivarius-Bacitracin (MSB) agar (HiMedia, Indian origin Bioscience company) for S. mutans and De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) agar (HiMedia, Indian origin Bioscience company) for Lactobacillus spp. Lactobacillus spp colonies were counted by pouring 1×101 on plates contain MRS agar and incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 3 days, the isolates were on the basis of colony morphology, gram staining (rod-shaped gram positive bacteria, non-spore forming,) and basic biochemical tests (catalase-positive and oxidase-negative).

Same procedure was followed for S. mutans, one ml of 1× 101 dilute was poured on plates contain MSB agar at 37 Cº in a microaerophilic atmosphere (5% O2, 10% CO2) for 24 hr.

2.3. Measurement of Salivary pH

A pH meter was used right away to assess the salivary pH (Radiometer, Crawley, UK). Freshly made pH 7 buffers were used to calibrate the pH meter, and while not in use, the electrode was kept immersed in double-distilled water. Following pH analysis, the electrode tip was once more cleaned with a mild stream of distilled water before being dipped in double-distilled water.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All of the study's parameters were examined in order to find the effects of different factors using the Statistical Analysis System-SAS-18 application. Significant mean comparisons were also made using the LSD test (Analysis of Variation-ANOVA), which measures the least significant difference at p≤0.05.

3. Results

3.1. The Distribution of Bacteria

The distribution of S.mutans and Lactobacillus in plaque and saliva represented as: distribution of bacteria according the gender , distribution of bacteria according to the plaque and saliva samples, and distribution according the age as in

Figure 3.

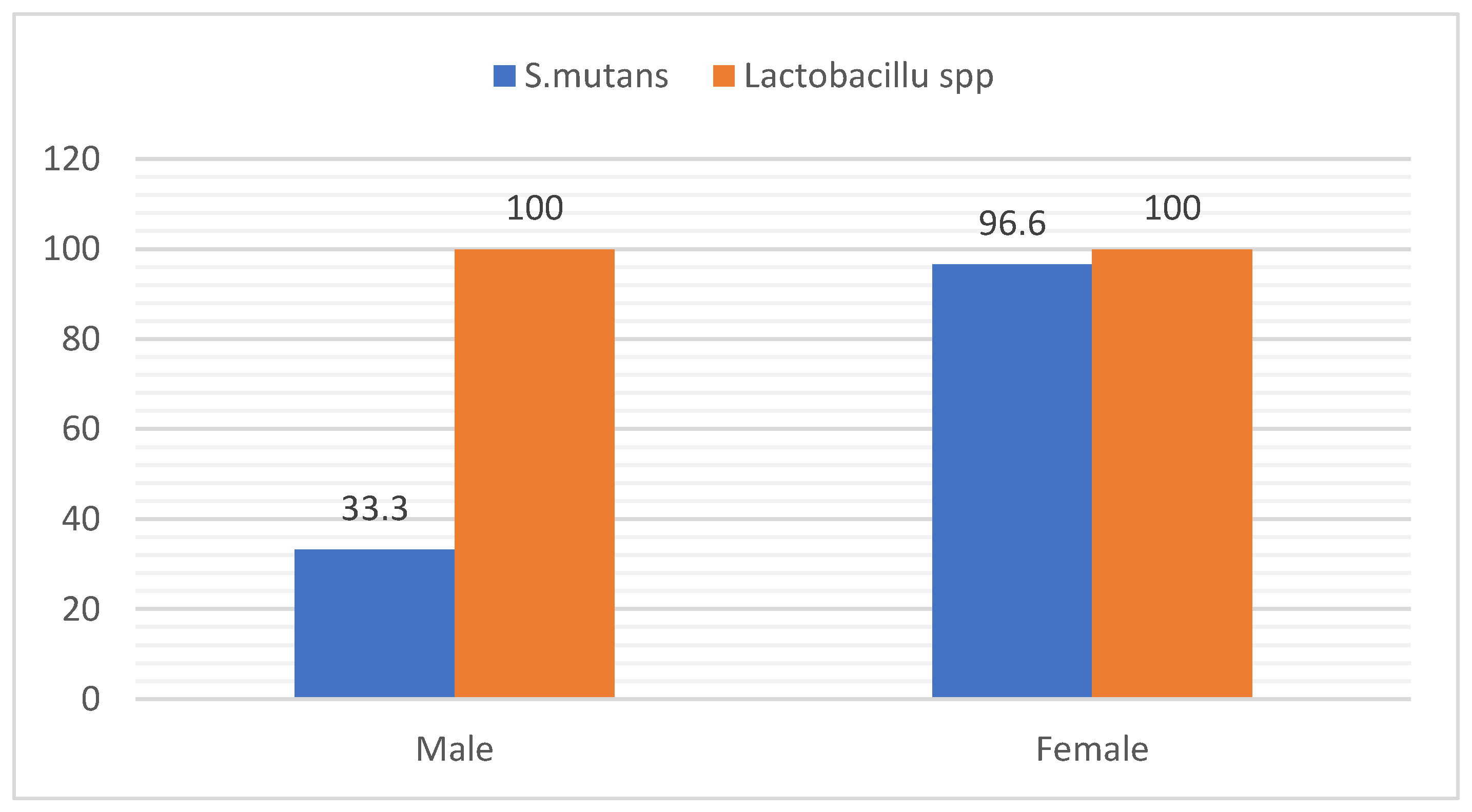

3.2. Distribution of Bacteria According to Gender

The results of this study revealed that (33.3%) of samples was positive for

S. mutans in male and (96.6%) in female, while

lactobacillus spp showed (100%) in male and female as in

Figure 4.

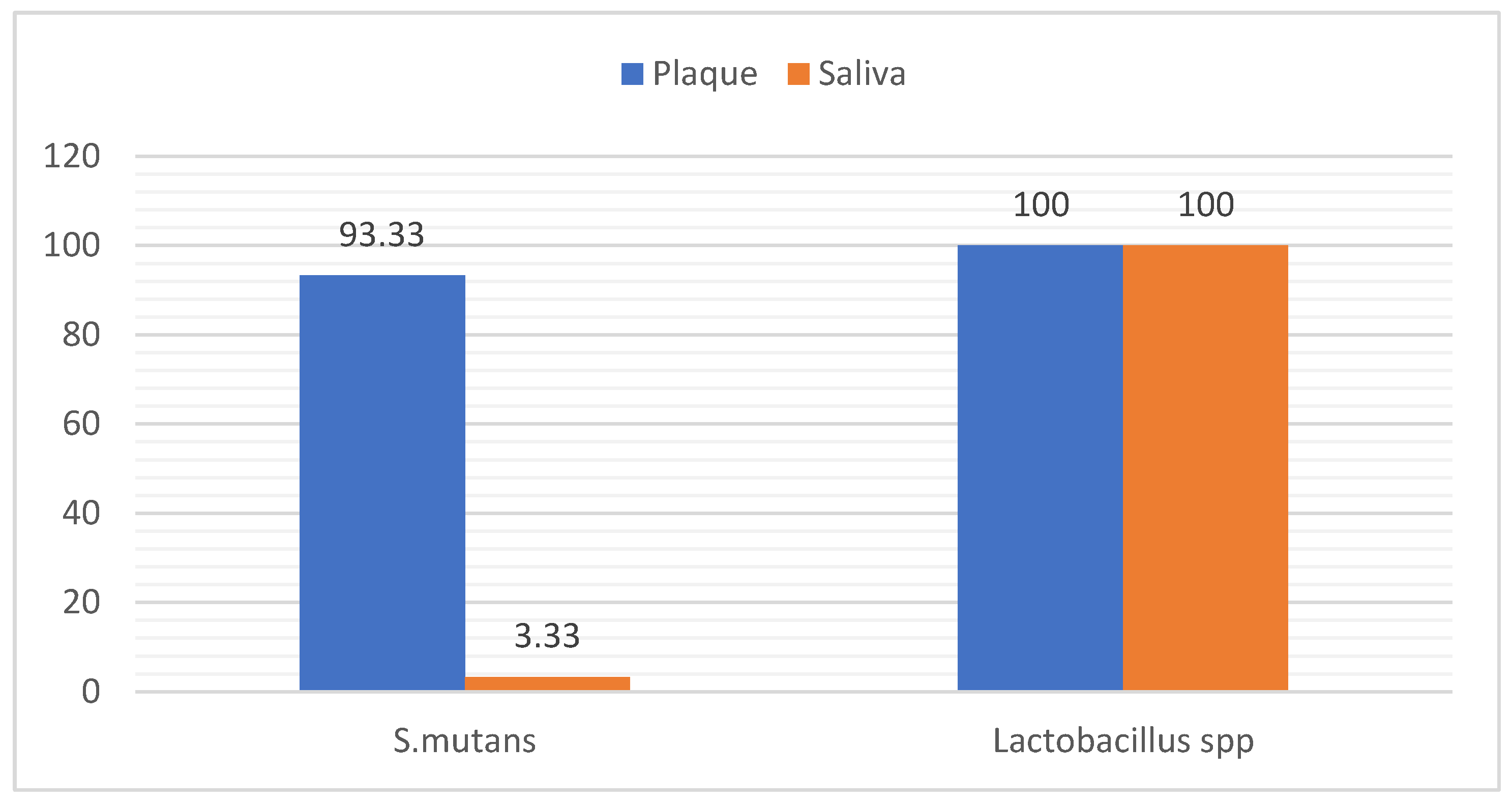

3.3. Distribution of Bacteria in Samples

The results of this study revealed that (93.33%) of plaque samples was positive for

S. mutans , while (3.33 %) of saliva sample was positive

S.mutans , However the results reported that (100.0 %) of plaque and saliva samples was positive for

lactobacillus spp as in

Figure 5.

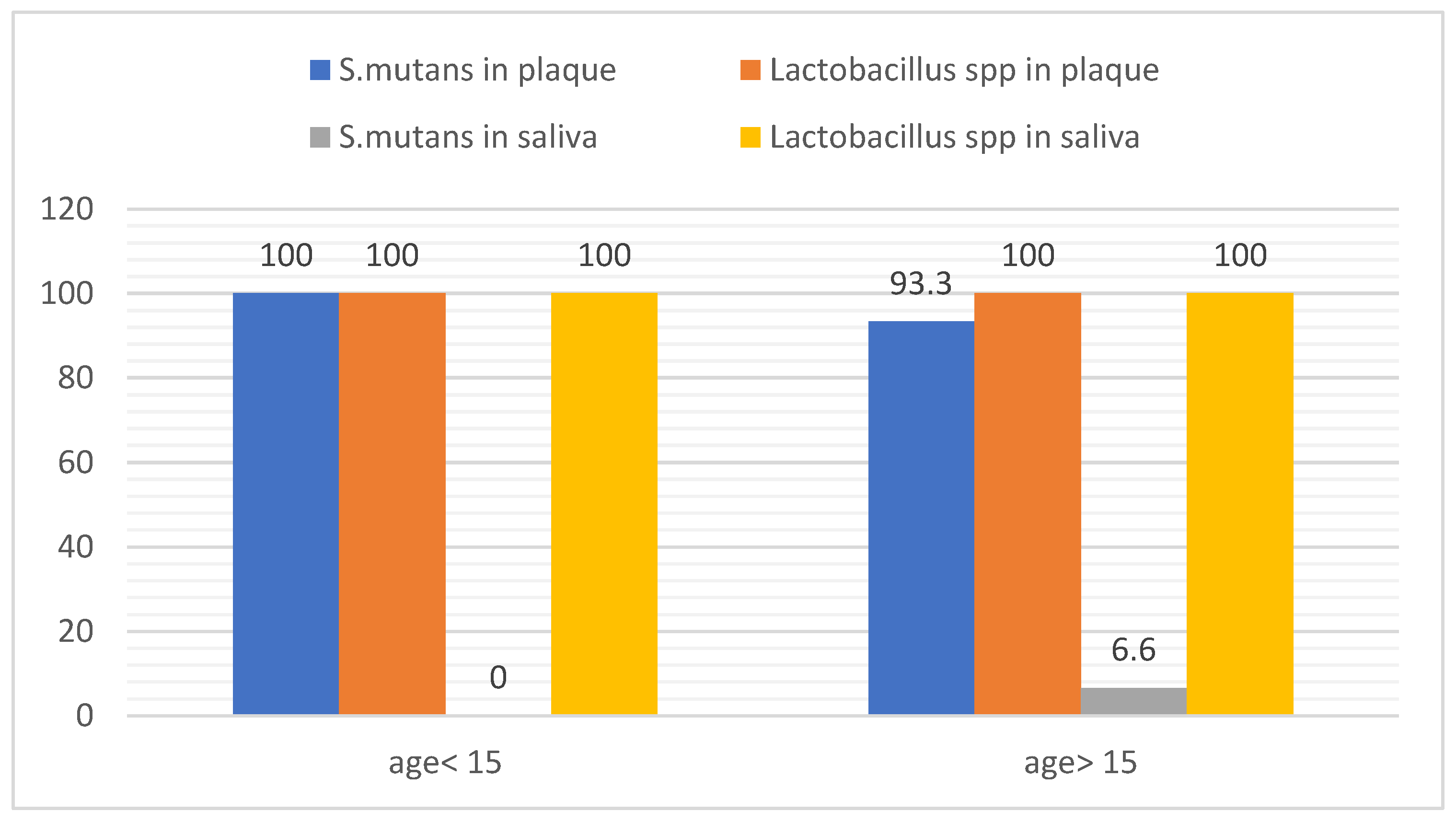

3.4. Distribution of Bacteria According the Age

The findings revealed all subjects showed (100%) positive for

lactobacillus spp of plaque and saliva. Moreover, the saliva sample in subjects age < 15 year showed no S

. mutans, while 6.6% of saliva sample in age > 15 year showed positive for

S. mutans. On the other hands, 93.3 % of plaque samples in subjects with age > 15 year were positive of

S. mutans. Finally,

S. mutans was recorded 100% in plaque samples in subjects with age <15 year as in

Figure 6.

3.5. Distribution of Bacteria in Studied Groups

The finding showed that the treatment with probiotic, Orth Kin and Corsodyl for a month showed a good effect against

S. mutans in plaque (37.00 ±1.41, 79.00 ±0.00, 69.00±0.00) respectively compared to baseline

)95.75±24.94) with significant difference at p< 0.05, with no significant difference recorded between Orth Kin and Corsodyl, but there was a significant difference between probiotic and both Kin and Corsodyl. The findings after two week of the treatment with probiotic, Orth Kin and Corsodyl were (61.50 ±38.89, 88.50 ±0.70, 70.50 ±0.70) respectively reported a significant difference with baseline (95.75±24.94) at p< 0.05, but no significant difference between probiotic and Corsodyl, moreover there was a significant difference between orthokin and both probiotic and Corsodyl at p< 0.05 as in

Table 1. Moreover, only one saliva sample was positive for

S. mutans recorded in male patient age > 15, this was statistically ignored and not taken into consideration in current study.

For Lactobacillus spp in plaque; the findings were recorded that after a month of the treatment with probiotic there was no significant difference with baseline; while both Orth Kin and Corsodyl (52.50±74.24; 79.50±37.47) respectively showed a significant difference at p<0.05 with baseline (124.50 ±4.94); from the other side the probiotic treatment reported the highest value 127±20.01. In addition; for the treatment after two weeks there was significant difference between all treatment with no treatment, but no significant difference between probiotic and Corsodyl treatment at p<0.05 also the probiotic treatment reported the highest value 111.00 ±28.70.

While in saliva sample the treatment after a month with probiotic, Orth kin and Corsodyl (130.50±0.05, 76.00±0.00, 46.00±65.05) respectively showed significant difference with baseline (128 ±29.69), the probiotic treatment recorded the highest value 130.50±0.05 while after two week no significant differences between all treatment with baseline except treatment with OrthoKin 83 ±0.00 showed significant difference with no treatment 128 ±29.69 at p<0.05 as well as the probiotic treatment reported the highest value 117.50 ±0.05 compared with other treatments as in

Table 2.

3.6. Salivary pH

The results showed there was no significant difference in saliva PH in treatment and no treatment period as showed in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

The results were in agreement with those of Toi et al [

14] who examined 83 subjects ranging in age from 3 to 17 years, 45 of whom were female (54.2%) and 38 of whom were male (45.8%). The samples showed positive levels of S. mutans in both saliva and plaque. Additionally, the findings were in agreement with those of Khalaf et al. [

15] who examined 135 children aged 3 to 10 years and discovered that S. mutans was more prevalent in dental plaque. According to Mummolo et al. [

16], 40 people (aged 20.4±1.7 years) had hazardous salivary levels (CFU/ml>105) of both Lactobacilli and S. mutans out of the 80 participants (46 men and 34 females) in the study.

Conversely, using a molecular technique like as PCR analysis, Lee et al. [

17] found S. mutans in 56.8% of plaque samples and 79.7% of saliva samples. Interestingly, children's saliva samples had a much lower percentage of S. mutans (59.1%) than did those from teenagers (88.0%) and adults (88.9%). On the other hand, S. mutans was found far more frequently in the plaque samples taken from children (86.4%) compared to those taken from adolescents (56.0%) and adults (33.3%), suggesting that there is a trend for dental caries to become more common as people age. Interestingly, for each of the three age groups, the value was marginally greater in the female population than in the male population.

Furthermore, our study found that the distribution of bacteria in saliva and plaque varied amongst studies, but this variation was consistent with [

18] who collected different samples from dental plaque (DP), saliva swab (SS), and whole saliva (WS). The SS technique noticed a significantly lower value of cfu/mL in comparison to the DP and WS methods (P < 0.05). Nonetheless, the outcomes of the WS and DP approaches were comparable (P > 0.05). Using the WS (100%) and SS (14.3%) procedures, only seven of the 15 participants in the first sequence of methods had a positive count for Lactobacillus Spp. Based on the study by Seki et al. [

19] which showed that a greater number of locations for dental plaque collection greatly rises, samples from all tooth surfaces were employed for the dental plaque collection method. Nevertheless, occlusal plaque had greater S. mutans counts than saliva samples, indicating that plaque might be a more accurate way to identify high S. mutans levels than saliva. This disparity might be explained by a greater supply of S. mutans in the oral plaque, which is the bacterium's principal home. Saliva may also be a similar proxy because S. mutans isolates from plaque into it during normal salivary clearance. According to Nguyen et al [

20] saliva and occlusal plaque can be regarded as trustworthy sources for S. mutans identification and quantification, irrespective of the state of the teeth.

Furthermore, the results of Treatment were agreed with several studies as the results of saliva samples were obtained from all 58 pediatric patients without any systemic medical conditions on the day (T0), one month (T1), three months (T2), and six months (T3) following general anaesthesia. by Sakaryalı et al. [

21] were agreed with our findings, even after the probiotic was stopped, the levels of S. mutans decreased in both groups over the course of the follow-up period. This decrease was not statistically significant, though. However, a statistically significant difference was observed as T3 levels of Lactobacillus spp. increased during the follow-up period in both groups, although the probiotics group experienced a statistically significant decrease during the first month of follow-up. Similar findings were reported by Badri and his colleague in 2021 [

22], who discovered that 54 participants, ages 8 to 12, were divided into three groups at random, with 18 youngsters in each group. Children in the CHX group were instructed to utilize CHX mouthwash bi-daily, while those in the probiotic group had one probiotic lozenge (Biogaia prodentis) daily. The results showed that both the CHX mouthwash and the probiotic lozenges dramatically decreased the number of S. mutans. Keller et al. [

23] found that the regrowth of salivary S. mutans levels was unaffected by the daily oral dose of Lactobacillus reuteri. According to a recent study, probiotic toothpaste and curd effectively decreased the quantity of streptococcus mutans in orthodontic patients [

24].

Finally, our findings indicated no significant differences between groups in salivary PH, which contradicts other research, including Badri et al [

22], who demonstrated that probiotic lozenges and CHX mouthwash dramatically decreased plaque index and S. mutans count while increasing salivary pH values. However, no statistical differences between the effect of and CHX mouthwash and probiotic lozenges in PH value. Different studies found there was increasing in salivary PH as According to Srivastava et al. [

25], when compared to regular curd, probiotic curd significantly increased salivary pH and decreased salivary S. mutans count from baseline to seven days. Probiotic curd is preferable to normal curd because it raised salivary pH after consumption. In a different study, Hoorizad et al. [

26] examined the effects of probiotic and non-probiotic yoghurt on orthodontic patients' salivary pH and found that probiotic yoghurt can raise salivary pH, creating an environment that is conducive to the remineralization of tooth substance structures. This suggests that curd does not present a caries risk despite its acidic nature [

27]. The limitations of the current study represented by the limited number of samples during the study period due to lack of commitment, the totals received the prescribed treatments, in addition to the fact that most of them did not attend the clinic at the specified time to take the samples.

5. Conclusions

Using the Probiotic mouthwash for two weeks and a month gave effective results than Orthkin and Corsodyl mouthwashes in which S. mutans level was reduced and at the same time Lactobacillus spp level was increased in group that treated with probiotic mouthwash compared with other mouthwashes. However, the salivary pH of the did not change during the treatment in studied groups in during study period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K.A.-L. and N.N.A.; methodology W.K.A.-L.; formal analysis, W.K.A.-L.; validation, W.K.A.-L. and N.N.A., investigation, N.N.A.; resources, W.K.A.-L.; data curation, L.A.A..; writing—original draft preparation, W.K.A-L..; writing—review and editing, W.K.A.-L. and N.N.A..; visualization, L.A.A.; supervision, L.A.A.; funding acquisition, W.K.A.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of College of Dentistry, Dijlah University (ref. [number 5] on 17 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank College of Dentistry, Dijlah University for their support during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duffy, R.; Maloney, B.; Burns, A. What are the optimum plaque control methods for patients with fixed orthodontic appliances? J. Ir. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UZUNER, F. the relationship between orthodontic treatment and dental caries. 2018.

- Van der Weijden, F.A.; Van der Sluijs, E.; Ciancio, S.G.; Slot, D.E. Can chemical mouthwash agents achieve plaque/gingivitis control? Dent. Clin. North Am. 2015, 59, 799–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deus, F.P.; Ouanounou, A. Chlorhexidine in dentistry: pharmacology, uses, and adverse effects. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.H.; Shi, W. A probiotic approach to caries management. Pediatr. Dent. 2006, 28, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lara-Villoslada, F.; Olivares, M.; Sierra, S.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Boza, J.; Xaus, J. Beneficial effects of probiotic bacteria isolated from breast milk. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, S96–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.C.; Valiere, A. Probiotics and medical nutrition therapy. Nutr. Clin. care an Off. Publ. Tufts Univ. 2004, 7, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Jain, U.; Prakash, A.; Sharma, A.; Shukla, C.; Chhajed, R. Efficacy of probiotic lozenges to reduce Streptococcus mutans in plaque around orthodontic brackets. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2016, 50, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toiviainen, A. Probiotics and oral health: In vitro and clinical studies.; Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, Sarja–Ser. D, Medica-Odontologica, 2015.

- Lin, X.; Chen, X.I.; Tu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. Effect of probiotic lactobacilli on the growth of Streptococcus mutans and multispecies biofilms isolated from children with active caries. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2017, 23, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twetman, L.; Larsen, U.; Fiehn, N.-E.; Stecksén-Blicks, C.; Twetman, S. Coaggregation between probiotic bacteria and caries-associated strains: an in vitro study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2009, 67, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Nikitkova, A.; Abdelsalam, H.; Li, J.; Xiao, J. Activity of quercetin and kaemferol against Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 98, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Fadaak, A.; Alomeir, N.; Wu, Y.; Wu, T.T.; Qing, S.; Xiao, J. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum on Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans clinical isolates from children with early childhood caries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. S. Toi, R. C. S. Toi, R. Mogodiri, and P. E. Cleaton-Jones, “Mutans streptococci and lactobacilli on healthy and carious teeth in the same mouth of children with and without dental caries,” Microb. Ecol. Health Dis., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 35–41, 2000.

- M. S. Khalaf, A. A. M. S. Khalaf, A. A. Qasim, Z. J. Jafar, and A. T. Mohammad, “Dental plaque caries related microorganism in relation to demographic factors among a group of Iraqi children,” Folia Med. (Plovdiv)., vol. 66, no. 4, pp. 491–499, 2024.

- S. Mummolo et al., “Salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacilli and other salivary indices in patients wearing clear aligners versus fixed orthodontic appliances: An observational study,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 4, p. e0228798, 2020.

- Y. J. Lee, M.-A. Y. J. Lee, M.-A. Kim, J.-G. Kim, and J.-H. Kim, “Detection of Streptococcus mutans in human saliva and plaque using selective media, polymerase chain reaction, and monoclonal antibodies,” Oral Biol. Res., vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 121–129, 2019.

- C. Motisuki, L. M. C. Motisuki, L. M. Lima, D. M. P. Spolidorio, and L. Santos-Pinto, “Influence of sample type and collection method on Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus spp. counts in the oral cavity,” Arch. Oral Biol., vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 341–345, 2005.

- M. Seki, F. M. Seki, F. Karakama, T. Ozaki, and Y. Yamashita, “An improved method for detecting mutans streptococci using a commercial kit,” J. Oral Sci., vol. 44, no. 3–4, pp. 135–139, 2002.

- M. Nguyen, M. M. Nguyen, M. Dinis, R. Lux, W. Shi, and N. C. Tran, “Correlation between Streptococcus mutans levels in dental plaque and saliva of children,” J. Oral Sci., vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 290–293, 2022.

- D. Sakaryalı Uyar, A. D. Sakaryalı Uyar, A. Üsküdar Güçlü, E. Çelik, B. Memiş Özgül, A. Altay Koçak, and A. C. Başustaoğlu, “Evaluation of probiotics’ efficiency on cariogenic bacteria: randomized controlled clinical study,” BMC Oral Health, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 886, 2024.

- S. M. Badri et al., “Effectiveness of probiotic lozenges and Chlorhexidine mouthwash on plaque index, salivary pH, and Streptococcus mutans count among school children in Makkah, Saudi Arabia,” Saudi Dent. J., vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 635–641, 2021.

- M. K. Keller, P. M. K. Keller, P. Hasslöf, G. Dahlén, C. Stecksén-Blicks, and S. Twetman, “Probiotic supplements (Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 5289) do not affect regrowth of mutans streptococci after full-mouth disinfection with chlorhexidine: a randomized controlled multicenter trial,” Caries Res., vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 140–146, 2012.

- J. E. Jose, S. J. E. Jose, S. Padmanabhan, and A. B. Chitharanjan, “Systemic consumption of probiotic curd and use of probiotic toothpaste to reduce Streptococcus mutans in plaque around orthodontic brackets,” Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop., vol. 144, no. 1, pp. 67–72, 2013.

- S. Srivastava, S. S. Srivastava, S. Saha, M. Kumari, and S. Mohd, “Effect of probiotic curd on salivary pH and Streptococcus mutans: a double blind parallel randomized controlled trial,” J. Clin. diagnostic Res. JCDR, vol. 10, no. 2, p. ZC13, 2016.

- M. Hoorizad, R. M. Hoorizad, R. Rahpeyma, M. Salehi, and S. Zavareian, “Effect of probiotic yoghurt on the salivary PH of orthodontic patients-A clinical trial study,” Res Dent Sci, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 155–159, 2013.

- R. Sudhir, P. R. Sudhir, P. Praveen, A. Anantharaj, and K. Venkataraghavan, “Assessment of the effect of probiotic curd consumption on salivary pH and streptococcus mutans counts,” Niger. Med. J., vol. 53, no. 3, 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).