1. Introduction

Marginal periodontitis is a chronic, inflammatory, nontransmissible disease that affects all parts of the periodontium and causes largely irreversible damage to the periodontium [

1]. This destructive process can be explained by the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis model [

2]. The model describes marginal periodontitis as a continuous cyclic process in which dysbiotic polymicrobial communities in the subgingival biofilm trigger an immune response that is ineffective, uncontrolled, and destructive to a susceptible host. The resulting inflammatory environment and tissue destruction exacerbates dysbiosis by selectively providing nutrients to pro-inflammatory bacteria, creating a self-perpetuating feedback loop that perpetuates the disease [

3]. Marginal periodontitis is thus an inflammatory disease induced by the subgingival biofilm that triggers destruction of the periodontium. Although subgingival biofilm is the primary cause of the development of marginal periodontitis, it is not sufficient to trigger the disease. The inflammatory response of the host to the microbial load can lead to the destruction of the periodontium, depending on the immunological situation [

4]. Thus, the primary etiological factor in the development of inflammatory marginal periodontal disease is the accumulation of microorganisms that colonize the surfaces of the oral hard and soft tissues and form a subgingival biofilm. This inflammation leads to pocket formation, attachment and bone loss and may result in tooth loss [

5]. It is now believed that the pathogenesis of marginal periodontitis is a multifactorial process based on dysbiosis, which involves both qualitative and quantitative deviations of the subgingival biofilm community from a health-related norm. This favors the proliferation of the subgingival biofilm, resulting in an immunoinflammatory host response that ultimately contributes to the destruction of the periodontium-forming structures, as postulated by the research group of Prof. Grimm (UW/H) in 2004 [

6,

7,

8]. However, more recent studies have shown that the spectrum of bacterial species that promote biofilm proliferation is much broader than previously thought [

9].

Current periodontal research focuses on species of the Bacteroidaceae family, which are endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) and ceramide producers. This family of bacteria is therefore able to induce the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins (mainly PGE

2), as well as interleukins (mainly Il-1) and tumor necrosis factor α. Therefore, the subgingival biofilm is characterized by a specific structure. Kolenbrander et al. (2002) [

10] consider the periodontopathogenic species as so-called “late colonizers” (

Figure 1), which are deposited on the underlying layers of the bacterial accumulation of the root surface in the form of a co-aggregation. These are mainly factors of bacterial co-adhesion and co-aggregation. The spatial arrangement changes at the beginning of subgingival biofilm formation along the substrate surface, and the pioneer bacteria obviously make the largest contribution to this community. The multi-species biofilm on the root surface demonstrates the importance of the surface morphology and chemical composition of the root surfaces for communication (“signaling”, “quorum sensing”) between the genetically distinct species within the subgingival biofilm [

11]. The virulence mechanisms involved in periodontal disease are multifactorial, with a focus on colonization, systemic dissemination, and induction of inflammatory and tumor responses in the host [

12,

13].

Aims

For decades, researchers have been intrigued by the question of whether there is a relationship between oil pulling therapy and marginal periodontitis. An extensive pubmed literature review has shown that even systematic reviews or quantitative meta-analyses of clinically controlled studies of oil pulling methods cannot fully prove the effect of oil pulling. Therefore, there is still no quantitative data-based analysis of the oral health effects of the organic oils commonly used in oil pulling [

14]. Oil pulling is an easy and available treatment. Central factors in the relationship between oil pulling therapy and periodontal disease include volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs), the oral microbiota that produce VSCs, and the inflammatory response. Oil pulling, as traditionally practiced, aims to reduce lipid-soluble bacteria and their VSC complexes. This process contributes to the reduction of the subgingival biofilm and allows for the formation of a physiological subgingival biofilm when the immune system is stabilized. However, all clinically controlled studies published to date on the effect of oil pulling on periodontal disease have consistently shown a large number of known biases [

15]. Therefore, the present study aims to compare the efficacy of commercially available oils as mouth rinses with the Air Flow treatment system (Air N Go Perio

® easy system) in subgingival biofilm management.

The clinical controlled study will analyze the effects of this oil mouthrinse in a simplified form compared to the conventional air flow treatment on subgingival biofilm management parameters. Both clinical and microbiological aspects will be addressed to provide a comprehensive insight into the efficacy of both methods [

16].

2. Material and Methods:

All examinations were performed in accordance with the examination protocol. The clinical and microbiological examinations were defined as follows: “Pre” refers to the time of completion of conservative periodontal therapy. Here, suitable patients were selected and pretreated. The time interval between the completion of conservative periodontal therapy and the “baseline” examination should be at least two to a maximum of six weeks. Baseline (BL) is the time point 0 of the study. Here, the group-specific therapy was carried out. The study comprised 32 test subjects, divided into an “experimental group” (oil mouthwash) and a “comparison group” (Air N Go Perio

® easy system). The clinical and microbiological parameters were recorded before the start, immediately after the clinical intervention, after 4 weeks and after 6 weeks using the results indicating in the publication of Nossek et al. [

16]. The analysis focused on statistical comparisons between the groups.

2.1. Study Design

The present study was designed according to best practice for clinical trials evaluating oral care practices. Blinding of the study was not possible because all participants were patients of the study practice and had undergone four recall visits due to previous periodontal therapy. The study comprised a randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) to evaluate the efficacy of G1 (oil mouth rinse) versus G2 (air flow treatment system [Air N Go Perio® easy system]) in subgingival biofilm management.

2.2. Participants

The sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome, which is the antimicrobial efficacy of commercial essential oils in saliva, measured as the reduction in microbial colony-forming units (CFU/mL) after treatment.

Assumptions:

Effect Size: Based on previous studies, we anticipate a mean difference (Δ) of 1.5 log₁₀ CFU/mL between the essential oil group and the control group. Standard Deviation (σ): Estimated at 1.2 log₁₀ CFU/mL (from pilot data or similar studies). Power (1-β): 80% (to detect a true effect if it exists). Significance Level (α): 0.05 (two-tailed). Adjusted for 20% dropout rate. After adjustment for dropouts: 32 participants (16 per group). A total of 32 subjects were included in the study. The test subjects were divided into two groups after prior pre-treatment:

and

The selection was based on defined inclusion criteria, which considered, among other things, the state of oral health and the exclusion of serious systemic diseases.

2.3. Interventions

Oil pulling treatment group (G1): The test subjects performed the oil rinse individually in a simplified manner. The patients were instructed to rinse their mouths with the oil for 5-10 minutes a day. The treatment lasted for 6 weeks. The product used was Araschied®. The oil mouthwash consists of sunflower, sage, and black cumin oil.

Air Flow group (G2): The subjects received treatment with the Air N Go Perio

® easy system, which enabled thorough subgingival debridement and removal of biofilm from the root surface. The new Perio

® easy nozzle was used in both groups. The working tip of the subgingival attachment was inserted into the gingival sulcus up to the pocket fundus, like a periodontal probe. The average treatment time was 30 seconds per tooth. The disease status of this group was “maintenance patients”, who received preventive treatment four times a year in accordance with the Lang risk assessment [

22]. This study group (G2) received only Air Flow treatment without oil pulling treatment.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Clinical Parameters:

Probing Depth (PD), Gingival Recession (GR), Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL), Bleeding on Probing (BOP) were measured at t1 (pre-intervention), t2 (immediate post-intervention), t3 (4 weeks post-intervention) and t4 (6-week observation period).

2.4.2. Microbiological Samples:

Modern microbiological diagnostics play an important role in a risk factor-oriented marginal periodontitis treatment concept. As the microbiological test was used the IAI Pado Test 4-5

® for each specific sample tooth. First, the periodontium is selected with the deepest pocket (>4 mm or deeper) after prior drying (microbiological examination tooth) [

21]. The microbiological parameters were recorded pre-interventional (t1), immediately post-intervention (t2) and 6 weeks (t4) months to analyze changes in the total bacterial load (TBL) and the changes for typical bacterial species of the subgingival biofilm.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using appropriate methods such as t-test and ANOVA to determine significant differences between groups.

The endpoint of this evaluation is the comparison of two treatment modifications of periodontal maintenance therapy in the two treatment groups. The significance level for parameter tests is set at α = 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics 19, IBM Corporation, US.

Clinical Endpoints:

After completion of the examinations, the clinical parameters collected were evaluated descriptively. The mean values of the variables Clinical Attachment Level (CAL), Bleeding on Probing (BOP), Probing Depth (PD) and Gingival Recession (GR) were determined.

Descriptive statistics of the continuous data (metric recording) Clinical Attachment Level (CAL), Probing Depth (PD) and Gingival Recession (GR) were performed using the median characteristic values in box plots. As a significant test for the comparison of the continuous data, analytical statistics were performed using Wilcoxon tests.

For categorical data, e.g., for the categorical value Bleeding on Probing (BOP), frequency tables or cross tables with frequencies were generated (descriptive statistics).

The differences in the analysis parameters over the periods of the study t1 (“baseline”), t3 (4 weeks after intervention), and t4 (after 6 weeks) were selected as secondary endpoints for the clinical values.

Microbiological Endpoints

The evaluation was like that for the clinical parameters (see above). Additional evaluations were also carried out:

Evaluation of the baseline measurement (t1)

Evaluation of the measurement immediately post-intervention (t2)

Evaluation of the measurement 6 weeks after intervention (t4)

Difference comparison of the measurement immediately after post-intervention to the baseline measurement (t2-t1)

Difference comparison of the measurement 6 weeks after intervention to the baseline measurement (t4-t1)

2.6. Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for clinical trials and all participants gave their informed written consent. The ethics committee of the Medical Association of Westphalia-Lippe and the University of Westphalia Wilhelms University approved the study in a letter dated June 23, 2016 with the file number 2015-530-f-S.

3. Results

A significant reduction in the Total Bacterial Load (TBL) was achieved in both groups. Clinical parameters, such as Probing Depth and BOP, showed a slightly non-significant improvement in both study groups, particularly after 6 weeks.

Overview of the Patient Population

The comparison groups were identical in terms of possible influencing factors, e.g., health or genetic factors. This relates to the parameters “age” and “gender” and refers to the homogeneous structure of both test groups.

Clinical Parameters

The analysis of the clinical parameters showed positive changes in both groups over the observation period. A statistically slightly non-significant decrease in Probing Depth (PD) and Bleeding on Probing (BOP) was observed in both G1 and G2. These improvements were particularly clear after 6 weeks of observation (T4).

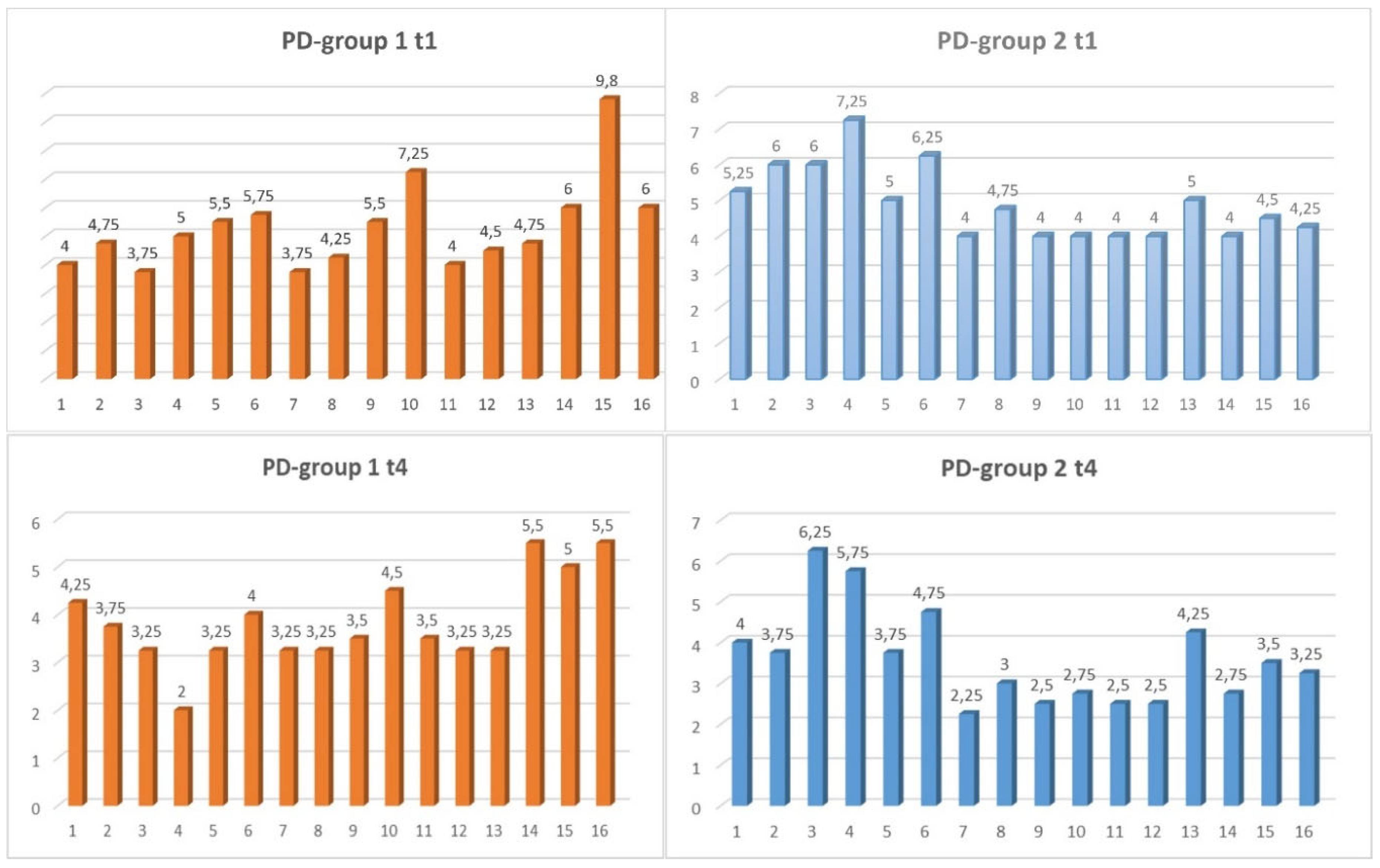

PD (Probing Depth Measurement)

For the statistical evaluation, the lowest measurement points at the time points t0, t3 and t4 of the periodontium was used. The periodontal status was assessed using a 2-point measurement. All measurements were taken with a commercially available periodontal probe (CP 15 UNC

® from HuFriedy

TM). We used the extreme values in accordance with Nossek et al. (1979) [

16].

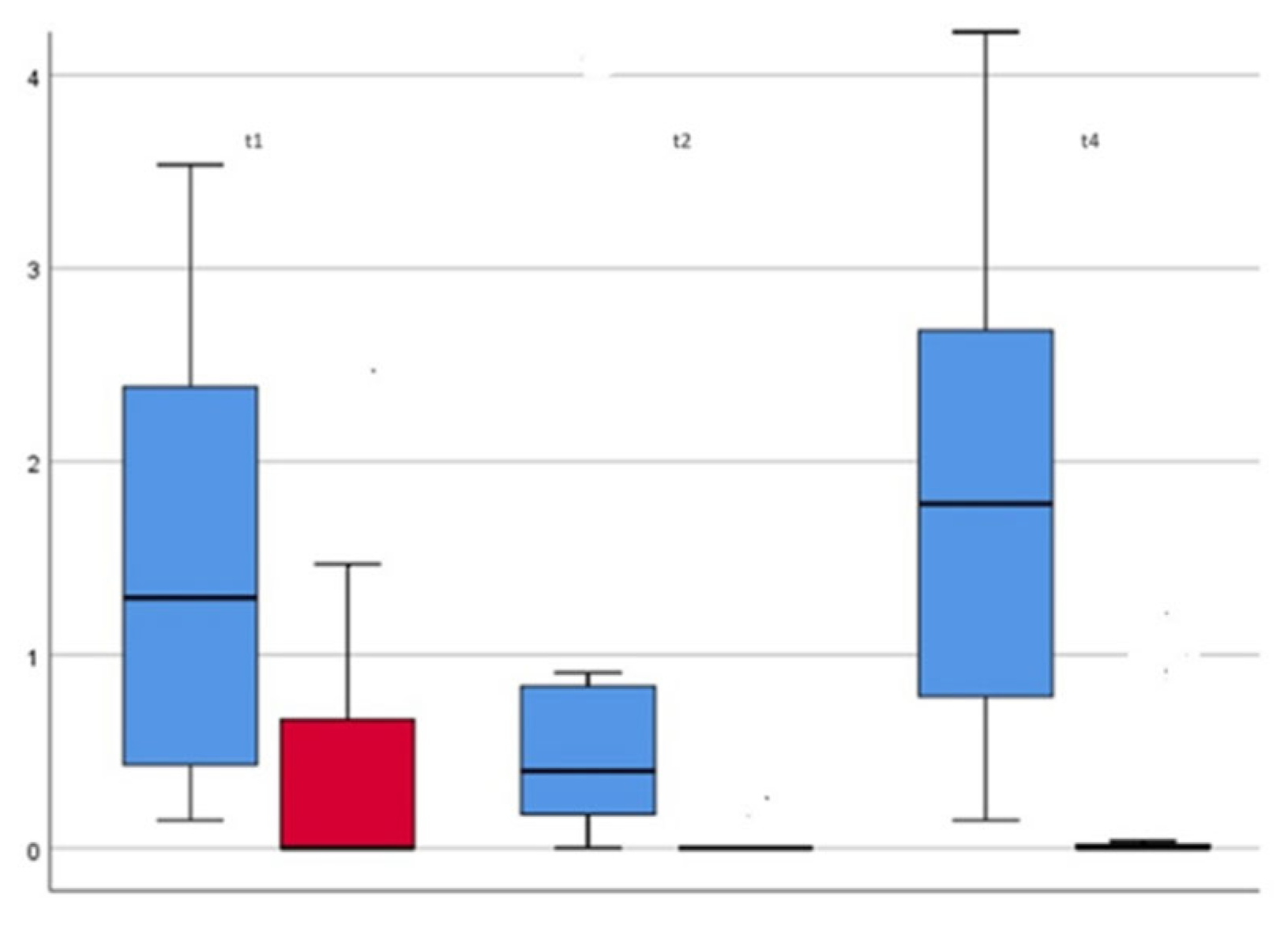

For the PD measurement parameter (

Figure 2), there was a slightly non-significant positive development in both groups for the period t1-t4.

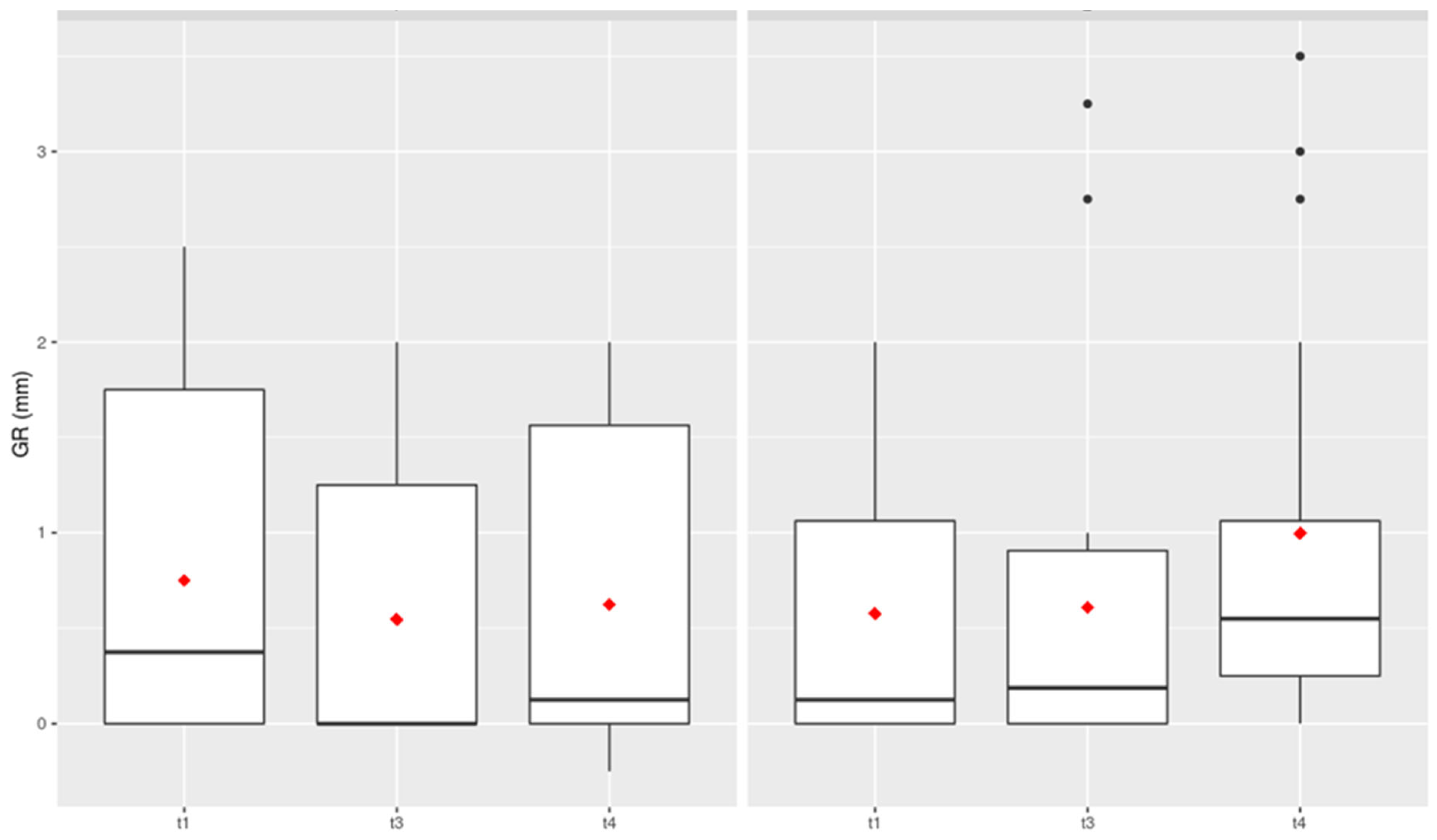

GR (Gingival Recession)

Looking at the clinical examination parameter of gingival recession, there was no significant difference between the two comparison groups at any of the examination times (

Figure 3).

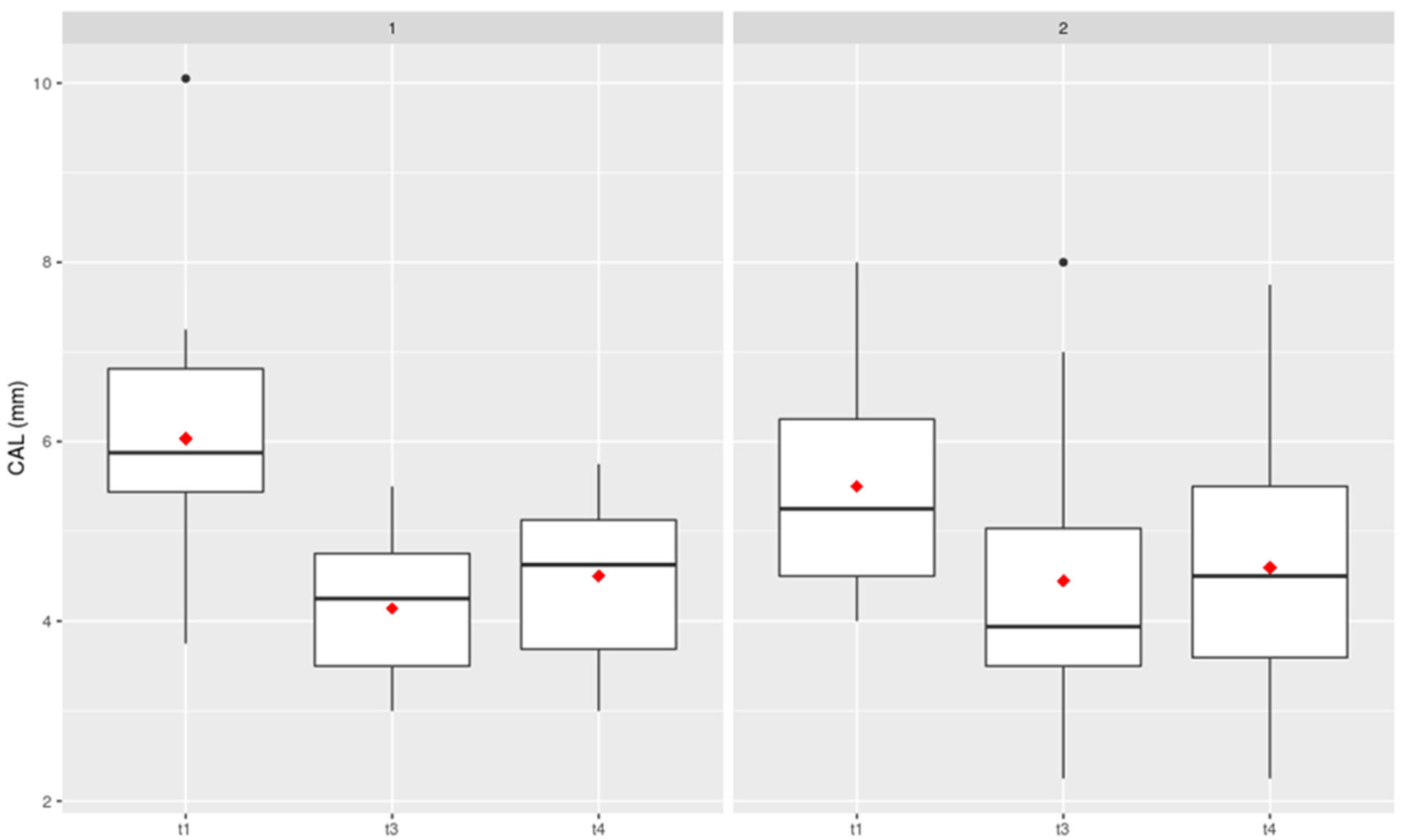

CAL (Clinical Attachment Level)

This parameter can be considered a compositional factor and is made up of PD+GR (

Figure 4). There was no increase in Clinical Attachment Loss in either comparison group, with no significant difference between the oil pulling and air flow treatments.

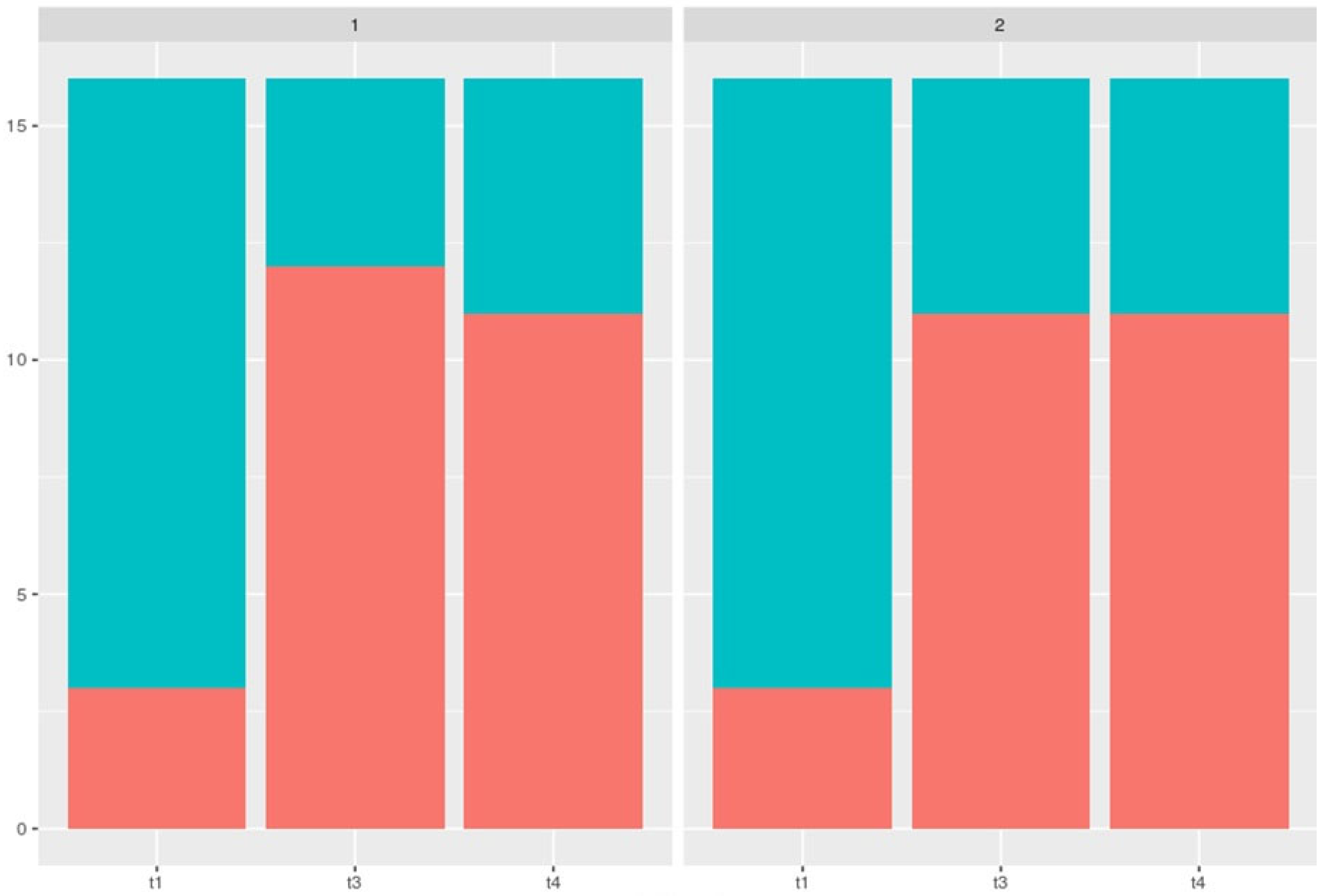

BOP (Bleeding on Probing)

The measurement parameter Bleeding on Probing provides information on the current inflammatory state of the tissue (

Figure 5). For data collection purposes, only a distinction was made between positive and negative. No further gradations were made in relation to the bleeding findings.

Microbiological Parameters

In terms of total bacterial load (TBL), microbiological studies showed a significant reduction in both groups after the intervention. Both G1 and G2 showed comparable efficacy in subgingival biofilm management.

The IAI Pado Test 4-5® was used for each specific sample tooth. Regarding the bacterial counts, it should be noted that the test used has a sensitivity of 104 bacteria. This means that a result of 0 does not indicate the complete absence of the tested bacteria, but only a bacterial concentration lower than the threshold (i.e., <104 bacteria). The presence of species below this detection limit is therefore quite possible. Bacterial counts were reported as the base value n multiplied by 106.

When looking at the microbiological test results at the specified measurement times, there were some significant differences in the analysis of individual measurement parameters. The determination was carried out for the data at the specified times t1, t2 and t4 as well as at the different times. This applies to all microbiological parameters examined in this study.

Primary Microbiological Endpoint - Total Bacterial Load (TBL)

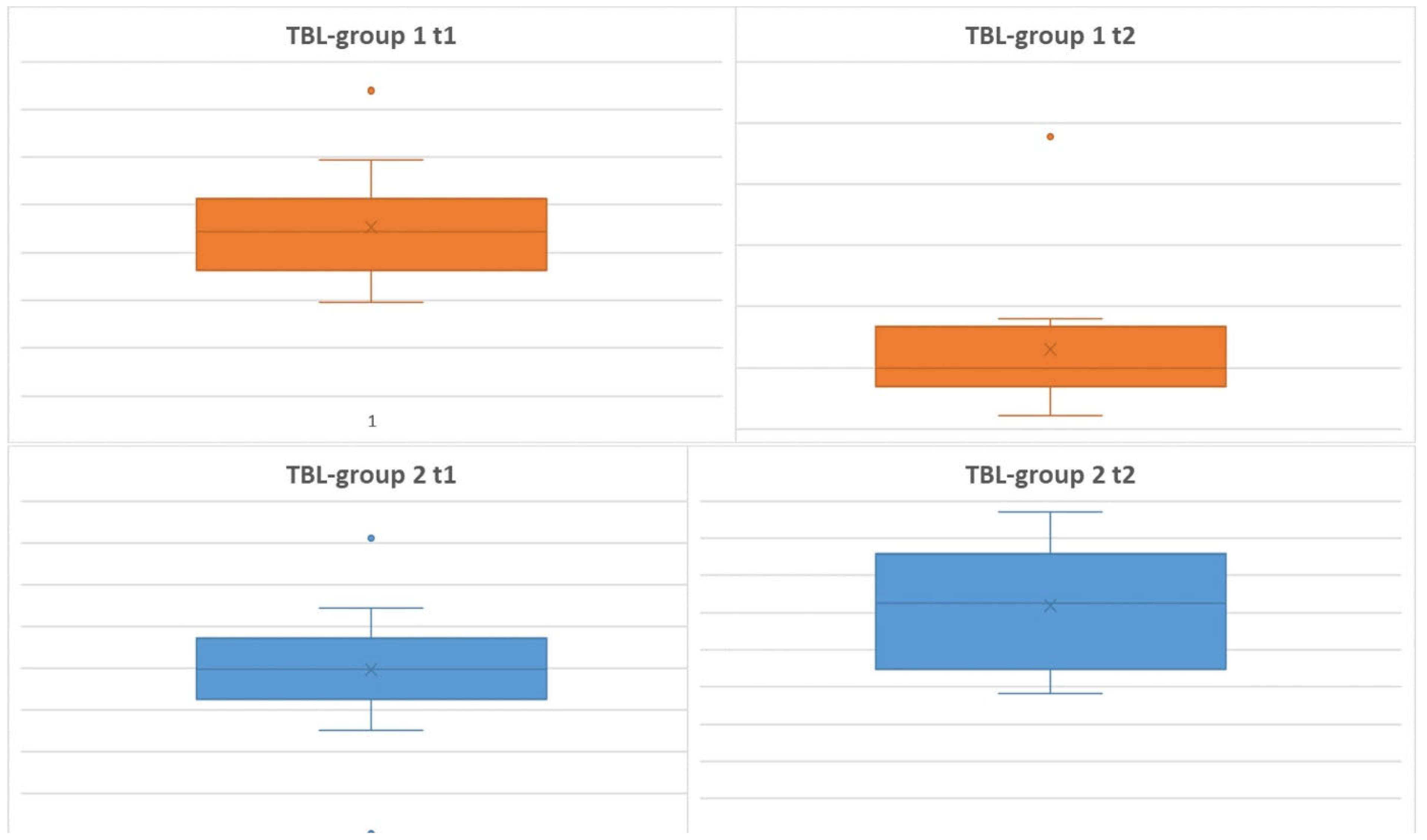

The measurements taken at the specified times were used to plot TBL (

Figure 6). The data shown in the box plots indicate that the median distribution of TBL at time 2 was slightly higher for Group 2 than for Group 1. This means that for the period t1-t2, there is an even greater decrease in TBL for Group 1. This can be explained by the apparently lower root surface erosion due to oil pulling compared to airflow-induced abrasion. In addition, there was an absolute improvement in TBL for both groups over the course of the study.

Looking at the data compared to time t4, i.e., after 6 weeks, it is noticeable that the medians have returned to approximately the initial value. Again, however, the result was not significant.

In summary, the following can be stated for the development of TBL over the 6-week period in our clinically controlled study:

The total bacterial count for the observation periods t1 and t2 differs significantly between the two groups.

When comparing the development of the two groups over the observation period, there were no significant differences.

The total bacterial count at the end of the observation period t4 was approximately the same as at time t1.

Secondary Microbiological Endpoints: Detection of the Individual Marker Bacteria

1. AA (Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans)

The measurement parameter AA could not be included in the evaluation. At no time did the bacterial count reach the threshold value of 104 bacteria in any of the test subjects. Nevertheless, a complete absence cannot be assumed.

2. PG (Porphyromonas gingivalis)

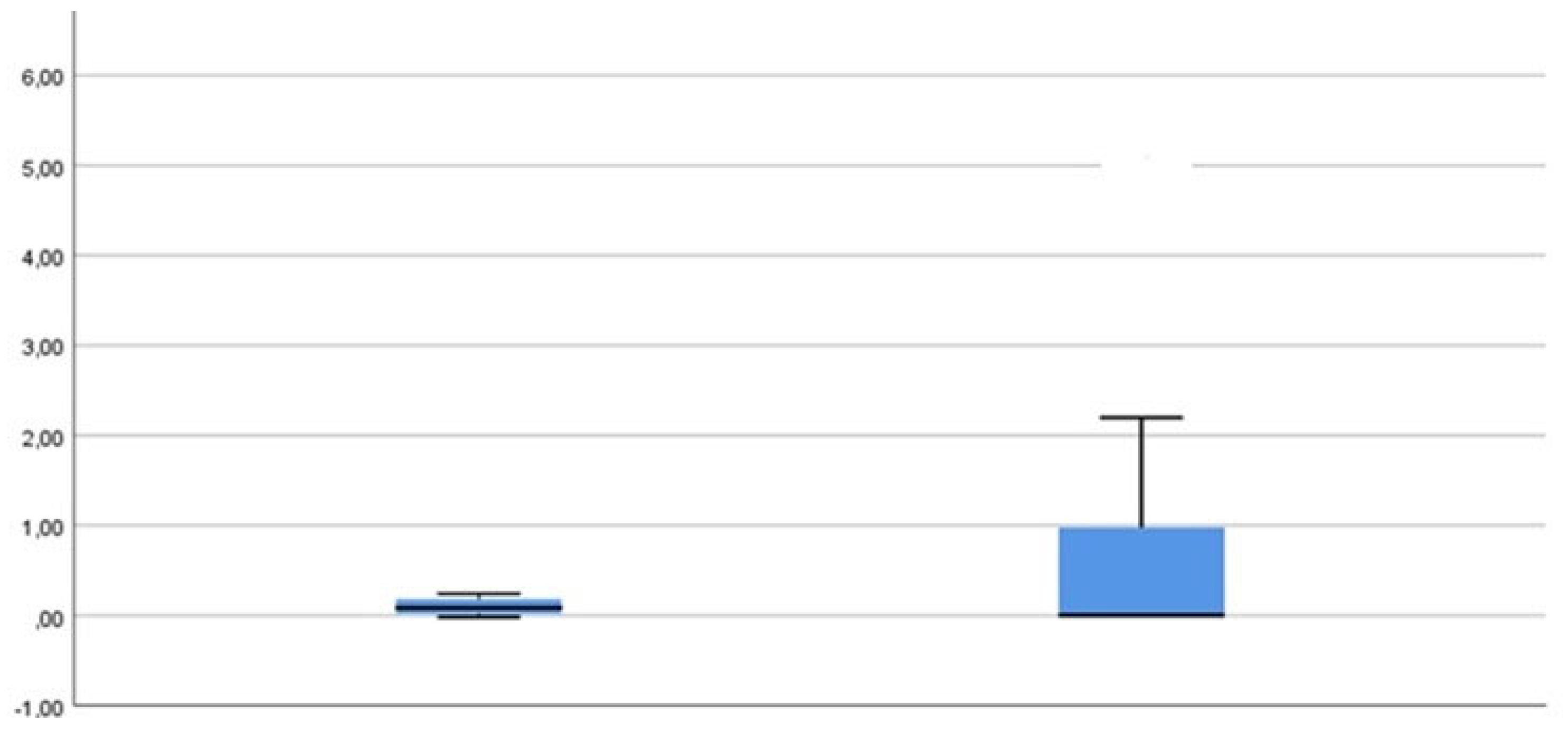

The following results can be determined for the PG measurement parameter (

Figure 7):

PG was only detectable in small numbers in both groups at all time points.

The only statistically significant development for PG can be seen when looking at the mean values from t1-t2.

A slight increase in the bacterial concentration for group 1 after 6 weeks can be observed but does not represent statistically significant information (data not shown).

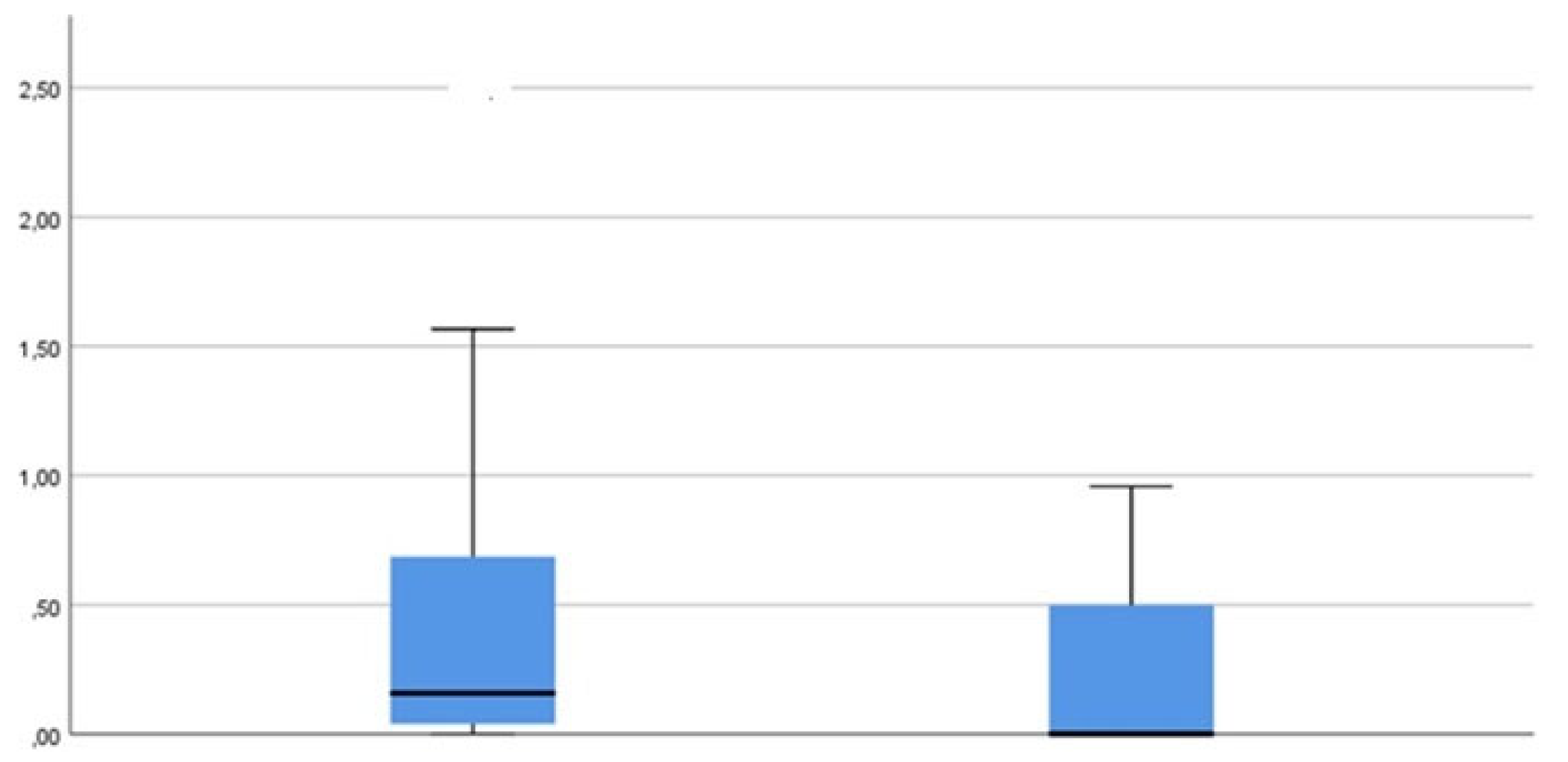

TD (Treponema denticola)

A similar development can be observed as for measurement parameter PG (

Figure 8).

TF (Tannerella forsythia)

Overall, the results correspond to those of the previously evaluated measurement parameters TBL, PG and TD (

Figure 9).

4. Discussion

Periodontal disease continues to be a serious challenge on a global scale [

17]. The exact mechanism of oil pulling on periodontal disease is not clear [

18]. Three possible mechanisms have been described in the literature. The first is alkaline lipid hydrolysis, which ultimately leads to “saponification”. The alkaline hydrolysis process emulsifies the fat contained in the pulling oil into bicarbonate ions, which are normally present in saliva [

19]. This means that subgingival biofilm is inhibited by the viscous properties of the oil [

20]. The third theory attempts to prove that the antioxidants contained in the oil prevent lipid peroxidation and produce antibiotic-like substances, thus contributing to the disruption of the subgingival biofilm [

14].

Our results confirm the efficacy of the Air N Go Perio® easy system in subgingival biofilm management. The oil mouthrinse achieved comparable results, especially in terms of total bacterial load. Despite positive effects on clinical parameters, there was no significant gain in clinical attachment loss (CAL). It should be emphasized that despite the proven efficacy of powder jet devices and the comparable performance of oil mouth rinses, there is no single “golden standard” in conservative periodontal therapy. The present study compared the efficacy of the “oil pulling cure” with the established air flow treatment in subgingival biofilm management. The results show positive effects on clinical parameters such as probing depth (PD) and bleeding on probing (BOP) in both groups. The reduction in total bacterial load (TBL) was also comparable between the oil pulling group and the airflow group.

Clinical Parameters

The improvement in Probing Depth and the reduction in Bleeding on Probing after application of the oil rinse indicate positive changes in periodontal health. These results are in line with previous research on oil-pulling studies indicating the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties of oils [

14,

15,

18,

19,

20].

However, it should be noted that oil irrigation did not show any significant disadvantages in terms of Gingival Recession (GR) and Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL) compared to air flow treatment. In addition, no removal of substance from the root surface can be observed with adjunctive treatment with oil compared to minimally invasive air flow treatment. It is known that every Air Flow treatment results in a slight loss of the root-cement surface. This loss of structure has been reduced with the introduction of less abrasive powders and a new design of the head pieces, which allow gentle insertion into the periodontal pocket [

21].

Microbiological Parameters

The comparable reduction in total bacterial load in both groups confirms the effectiveness of oil rinsing in subgingival biofilm management. This supports that lipid-soluble bacteria, which are reduced by oil rinsing, contribute to the total bacterial load in the subgingival space.

Further Considerations

The results of this study indicate that oil rinsing can be considered a promising addition to established oral care practices. The positive changes in clinical and microbiological parameters support the potential benefits of this traditional method.

Conclusion and Outlook

The present study contributes to a better understanding of the effects of oil pulling on periodontal health. Although the results are promising, further research is needed to clarify the long-term effects and the full extent of the potential benefits. Future studies could also further investigate specific mechanisms of action of the oil pulling regimen and evaluate the method in different patient populations.

Overall, the results of this study confirm the potential efficacy of oil pulling as an alternative method of subgingival biofilm management. This traditional treatment method could play an important role in future oral care protocols, although the needs and preferences of patients and their individual oral health must be taken into account.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Clinical Relevance

Scientific rationale for studyOverall, the results of this study confirm the potential efficacy of the oil pulling regimen as an alternative method in subgingival biofilm management. Principal findings: The efficacy of the “experimental group” and the “comparison group” was compared. 32 subjects were clinically and microbiologically evaluated at four different time points: t1 (pre-intervention), t2 (immediately post-intervention), t3 (4 weeks post-intervention) and t4 (6-week observation period). A statistically significant reduction in total bacterial load (TBL) was achieved in both groups. Practical implications: This traditional treatment method could play a significant role in future oral care protocols.

Author’s contribution

WDG: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, software, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, supervision. TF: conceptualization, supervision.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. MA Vukovic and his team for their generous support in conducting the study.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Ethics Statement

The ethics committee of the Medical Association of Westphalia-Lippe and the University of Westphalia Wilhelms University approved the study in a letter dated June 23, 2016 with the file number 2015-530-f-S.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Dannewitz B, Holtfreter B, Eickholz P. Parodontitis – Therapie einer Volkskrankheit [Periodontitis-therapy of a widespread disease]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2021 Aug; 64(8):931-940.

- Herrera D, Sanz M, Kebschull M, Jepsen S, Sculean A, Berglundh T, Papapanou PN, Chapple I, Tonetti MS; EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultant. Treatment of stage IV periodontitis: The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2022; Jun; 49 Suppl 24:4-71.

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T, Lambris JD. Current Understanding of Periodontal Disease Pathogenesis and Targets for Host-Modulation Therapy. Periodontol 2000 2020; 84(1):14–34.

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012;10:717–725.

- Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:30-44.

- von Moeller, S., Entschladen, F., Gaßmann, G., Zänker, K., Grimm, WD. Activation and migration of CD4+ lymphocytes induced by different “foreign bodies”. Parodontologie 2004;432-433.

- Gassmann, G., Schwenk, B., Entschladen, F., Grimm, WD. Influence of enamel matrix derivative on primary CD4+ T-helper lymphocyte migration, CD25 activation, and apoptosis. J Periodontol 2009;80:1524-33.

- Keeve, P. L., Dittmar, T., Gassmann, G., Grimm, WD., Niggemann, B., Friedmann, A. Characterization and analysis of migration patterns of dentospheres derived from periodontal tissue and the palate. J Periodontal Res 2013;48:276-85.

- Hagi, T. T., Klemensberger, S., Bereiter, R., Nietzsche, S., Cosgarea, R., Flury, S., Lussi, A., Sculean, A., Eick, S. A Biofilm Pocket Model to Evaluate Different Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment Modalities in Terms of Biofilm Removal and Reformation, Surface Alterations and Attachment of Periodontal Ligament Fibroblasts. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131056.

- Kolenbrander, P. E., Andersen, R. N., Blehert, D. S., Egland, P. G., Foster, J. S., & Palmer Jr, R. J. Communication among oral bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews: MMBR 2002; 66(3):486–505.

- Hajishengallis, G., Darveau, R. P., Curtis, M. A. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012;10:717-25.

- Hajishengallis, G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol 2014;35:3-11.

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012;10:717–725.

- Jong FJX, Ooi J, Teoh SL. The effect of oil pulling in comparison with chlorhexidine and other mouthwash interventions in promoting oral health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg 2024;Feb;22(1):78-94.

- Peng, T.-R.; Cheng, H.-Y.;Wu, T.-W.; Ng, B.-K. Effectiveness of Oil Pulling for Improving Oral Health: A Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022;10:1-9.

- Nossek, H., WD Grimm, K Gäbler. Studies of periodontal results obtained for selected teeth and groups of teeth with particular reference to their predictive potential regarding an overall assessment. Zahn Mund Kieferheilkd Zentralbl 1979;67(3):246-255.

- World Health Organization. WHO Oral Health CAPP (Country/Area Profile Programme). https://capp.mau.se/download.

- Marcelo W.B. Araujo; Christine A. Charles; Rachel B. Weinstein; James A. McGuire; Amisha M. Parikh-Das; Qiong Du; Jane Zhang; Jesse A. Berlin; John C. Gunsolley. Meta-analysis of the effect of an essential oil–containing mouthrinse on gingivitis and plaque. JADA 2015;146(8): 610-22.

- Asokan, S.; Rathinasamy, T.K.; Inbamani, N.; Menon, T.; Kumar, S.S.; Emmadi, P.; Raghuraman, R. Mechanism of oil-pulling therapy-in vitro study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2011, 22, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, P.; Hongal, S.; Jain, M.; Rana, K.; Saxena, V. Oil pulling and oral health: A review. Int. J. Sci. Study 2014, 1, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Meerman, D.; Sh. Nameni; MA Vukovic; WD Grimm. Retrospektive Patientenbeobachtungs-Studie für die antimikrobielle Photodynamische Therapie von parodontalen Entzündungen. Jahrestagung der AfG am 14.01.2022, Kurzvortrag, 3120.

- Lang NP, Tonetti MS. Periodontal Risk Assessment (PRA) for Patients in Supportive Periodontal Therapy (SPT). Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry 1/2003, S. 7-16.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).