Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Sample Size Calculation

Specimen Preparation

Polishing Procedures

Surface Roughness Evaluation

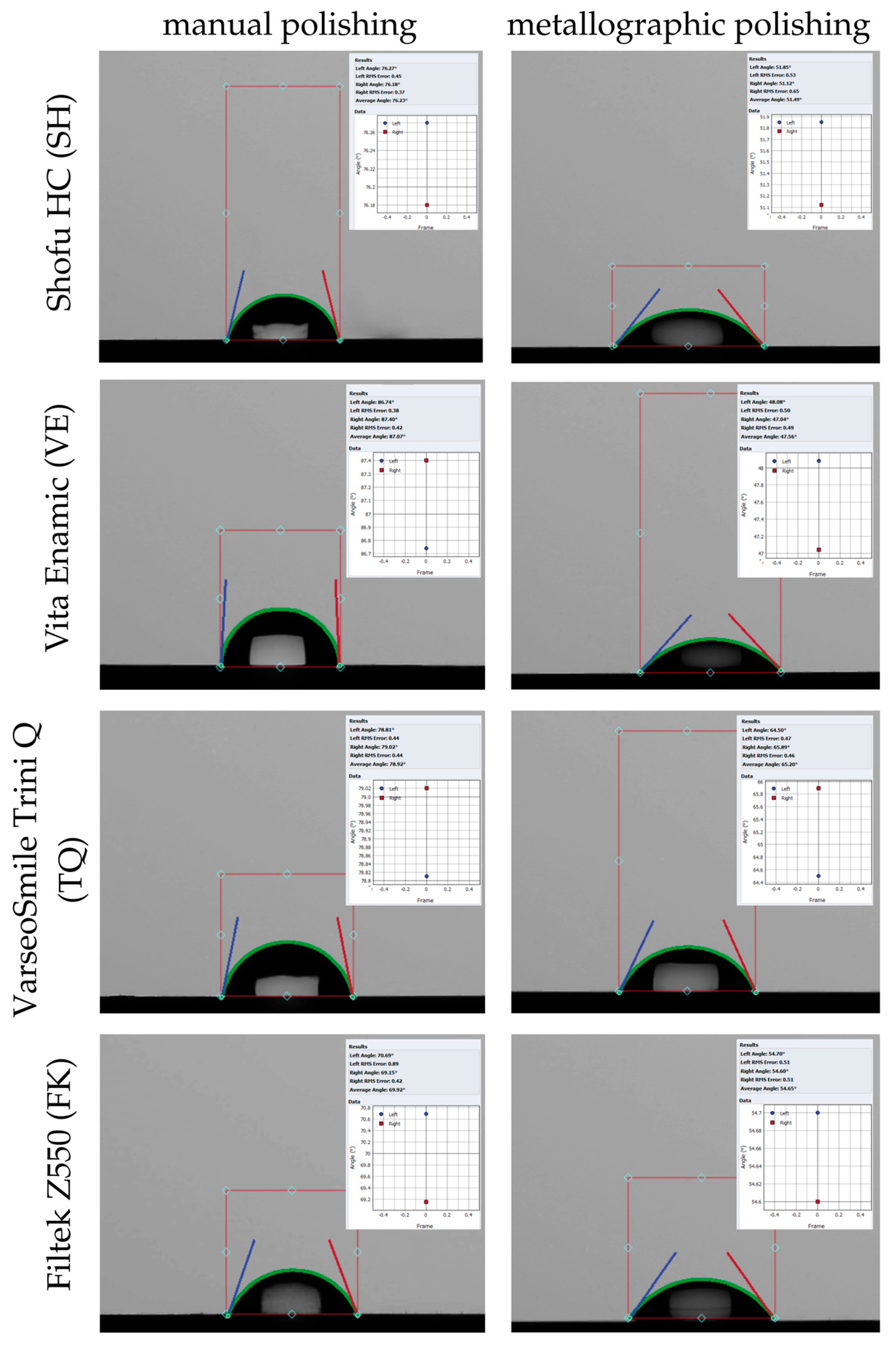

Surface Wettability Assessment

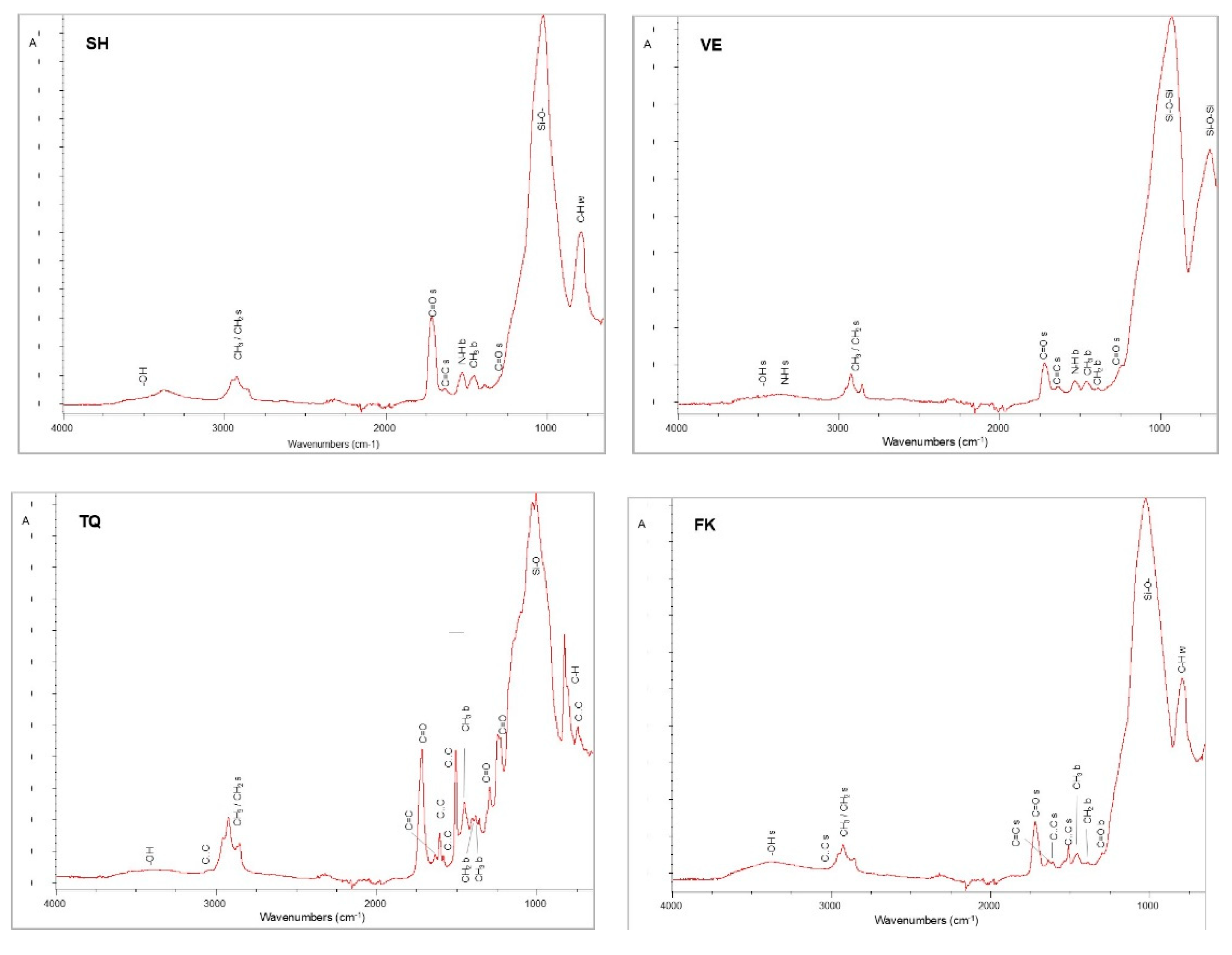

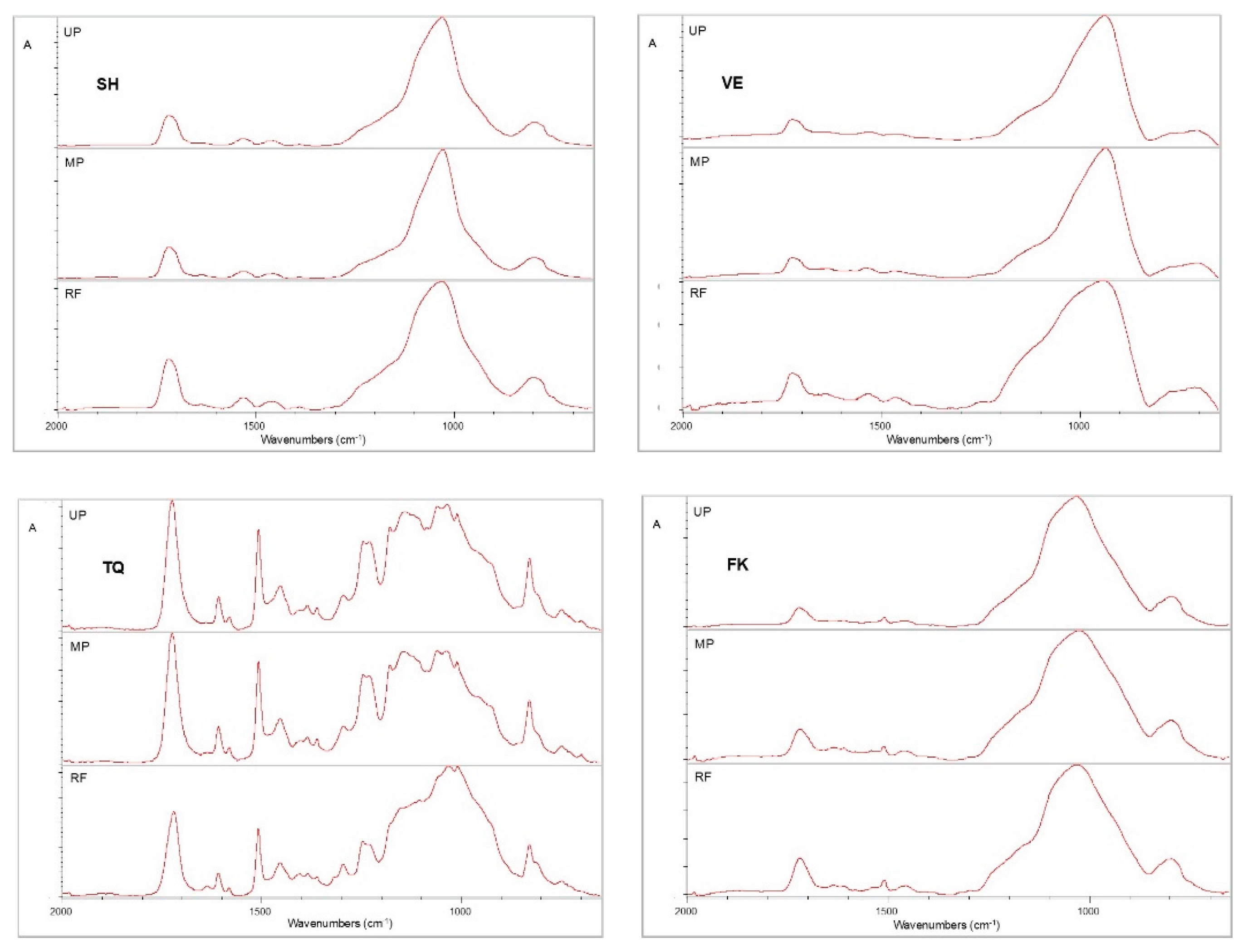

Attenuated Total Reflectance – Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR – FTIR) analysis

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Surface Roughness Evaluation

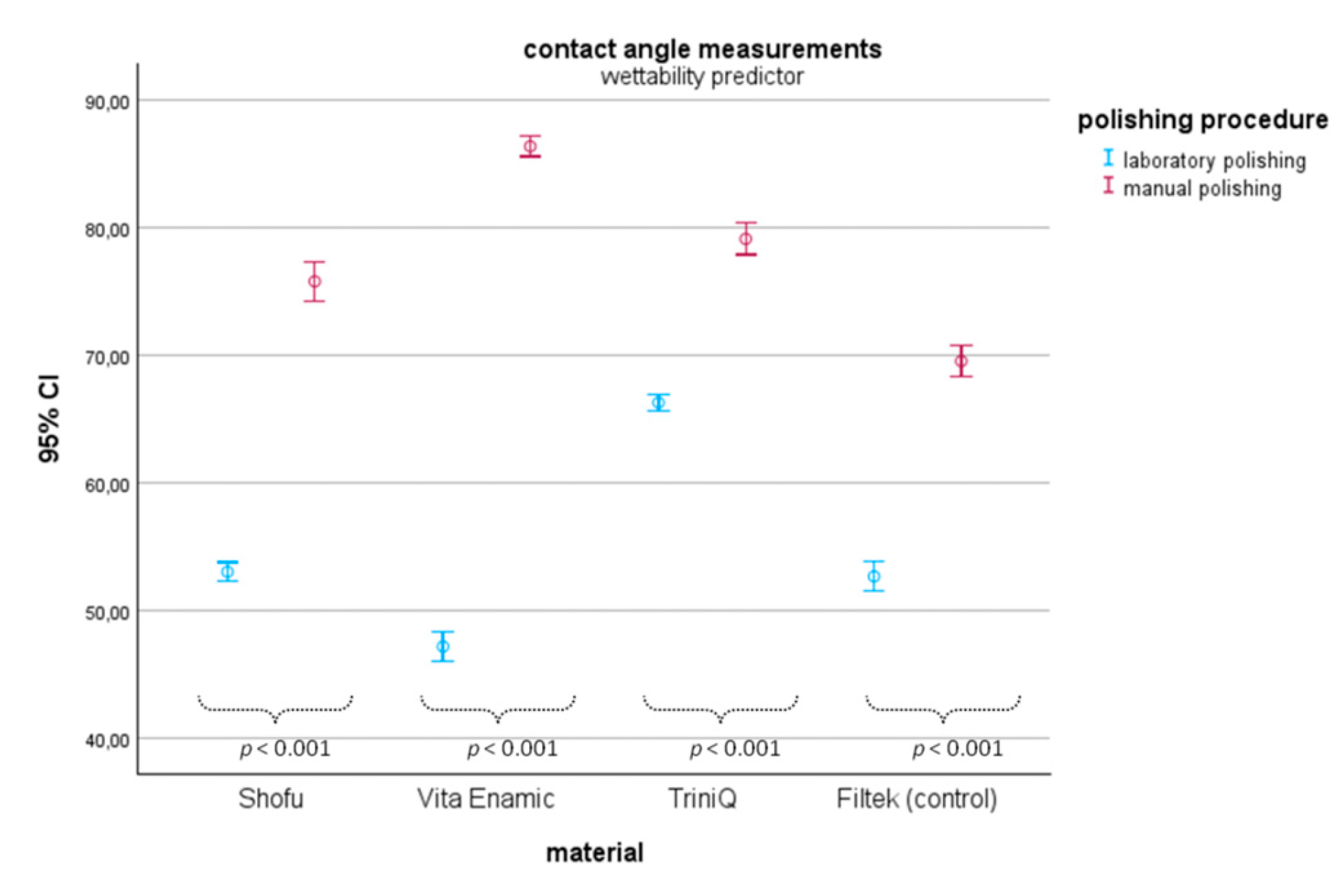

3.2. Surface Wettability

3.3. Interaction Between Surface Roughness Parameters and Surface Wettability

3.4. Development of a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) to Assess the Effect of Material Type and Polishing Procedure on the Measured Surface Characteristics

3.5. ATR-FTIR Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

| Dependent parameter | Predictors | B estimate | Wald χ2 | df | p - value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sa | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 163.45 | 2280.35 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant decrease in Sa relative to the reference group Metallographic polishing resulted in a significant decrease in Sa compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on Sa depended on the material type The reduction effect from metallographic polishing was mitigated depending on the material type, with a greater moderation presented for SH |

|

χ² = 234.37 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 276.22, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 494.00, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 236.71, p < 0.001 | ||||||

| SH | – 102.82 | 451.17 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | –74.73 | 238.36 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| TQ | –59.96 | 153.42 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | –106.26 | 481.85 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | +105.31 | 236.67 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | +52.91 | 59.75 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +51.62 | 56.86 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| Sz | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 1896.26 | 1125.72 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant decrease in Sz relative to the reference group Metallographic polishing resulted in a significant decrease in Sz compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on Sz depended on the material type The reduction effect from metallographic polishing was mitigated depending on the material type, with a greater moderation presented for SH |

|

χ² = 154.35 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 158.17, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 120.20, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 104.84, p < 0.001 | ||||||

| SH | -1241.25 | 241.17 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | -616.14 | 59.42 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| TQ | -852.75 | 113.83 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | -1101.21 | 189.82 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | +1114.82 | 97.27 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | +725.65 | 41.21 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +811.77 | 51.56 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| Sdr | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 5.79 | 1504.22 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant decrease in Sdr relative to the reference group Metallographic polishing resulted in a significant decrease in Sdr compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on Sdr depended on the material type The reduction effect from metallographic polishing was mitigated depending on the material type, with a greater moderation presented for SH |

|

χ² = 233.65 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 419.05, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 262.81, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 316.84, p < 0.001 | ||||||

| SH | -5.37 | 648.09 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | -3.98 | 356.63 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| TQ | -4.10 | 378.30 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | -4.87 | 533.62 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | +4.93 | 272.44 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | +3.79 | 161.55 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +3.94 | 174.10 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| Sds | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 18568.53 | 600.47 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant increase in Sds relative to the reference group No statistically significant increase in Sds for metallographic polishing compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on Sds depended on the material type for SH and TQ, but not for VE |

|

χ² = 71.61 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 79.13, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 15.72, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 11.56, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| SH | +4779.69 | 19.90 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | +3952.56 | 13.60 | 1 | p < 0.01 | ||

| TQ | +2757.03 | 6.62 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | +229.06 | 0.05 | 1 | p > 0.05 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | +3463.54 | 5.22 | 1 | p < 0.05 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | +164.46 | 0.01 | 1 | p > 0.05 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +3952.42 | 6.80 | 1 | p < 0.01 | ||

| Sc | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 251.83 | 1739.39 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant decrease in Sc relative to the reference group Metallographic polishing resulted in a significant decrease in Sc compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on Sc depended on the material type The reduction effect from metallographic polishing was mitigated depending on the material type, with a greater moderation presented for SH |

|

χ² = 217.42 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 299.50, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 354.91, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 173.98, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| SH | -165.17 | 374.10 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | -141.00 | 272.63 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| TQ | -107.25 | 157.74 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | -164.92 | 372.67 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | +158.42 | 172.07 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | +93.50 | 59.94 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +86.00 | 50.71 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| Sv | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 22.92 | 1104.36 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant decrease in Sv relative to the reference group Metallographic polishing resulted in a significant decrease in Sv compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on Sv depended on the material type The reduction effect from metallographic polishing was mitigated depending on the material type, with a greater moderation presented for SH |

|

χ² = 163.74 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 62.47, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 247.34, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 122.68, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| SH | -12.92 | 175.42 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | -5.08 | 27.17 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| TQ | -5.75 | 34.76 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | -14.08 | 208.54 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | +14.97 | 117.76 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | +5.11 | 13.72 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +5.58 | 16.39 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| Water contact angles | Intercept (manually polished FZ) | 69.51 | 21428.78 | 1 | p < 0.001 | SH, VE and TQ show a significant increase in contact angles relative to the reference group Metallographic polishing resulted in a significant decrease in contact angles compared to manual polishing The effect of polishing on contact angles depended on the material type |

|

χ² = 401.25 , df = 7, p < 0.001 material (main effect): Wald χ² = 635.56, p < 0.001 polishing procedure (main effect): Wald χ² = 4648.74, p < 0.001 material and polishing procedure (interaction): Wald χ² = 892.91, p < 0.01 | ||||||

| SH | +6.24 | 86.42 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| VE | +16.82 | 627.00 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| TQ | +9.57 | 203.06 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographic polishing | -16.86 | 630.05 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished SH | -5.88 | 38.35 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished VE | -22.31 | 551.67 | 1 | p < 0.001 | ||

| metallographically polished TQ | +4.04 | 18.08 | 1 | p < 0.001 |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD/CAM | Computer Aided Design/Computer Aided Manufacturing |

| FK | Filtek Z550 |

| VE | Vita Enamic |

| SH | Shofu HC |

| TQ | VarseoSmile TriniQ |

| SM | Subtractive manufacturing |

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| PICN | Polymer Infiltrated Ceramic Network |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| DLP | digital light processing |

| LCD | liquid crystal display |

| BisGMA | Bisphenol glycidyl dimethacrylate |

| BisEMA | Bishenol ethylene glycol diether dimethacrylate |

| TEGDMA | Triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate |

| PEGDMA | Polyethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

| SiC | Silicon Carbide |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| ATR-FTIR | Attenuated Total Reflectance – Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GLM | Generalized linear model |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning Electron Microscopy- Energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| Micro-CT | Micro-computed Tomography |

References

- Bhargav, A.; Sanjairaj, V.; Rosa, W.; Feng, LW.; Fuh Yh, J. Applications of additive manufacturing in dentistry: A review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018, 106, 2058–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, T.A. Materials in digital dentistry-A review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020, 32, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, J.; Belli, R.; Lohbauer, U. Contemporary CAD/CAM Materials in Dentistry. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2019, 6, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, H.; Durand, J.C.; Jacquot, B.; Fages, M. Dental biomaterials for chairside CAD/CAM: State of the art. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainjot, A.K.; Dupont, N.M.; Oudkerk, J.C.; Dewael, T.Y.; Sadoun, M.J. From Artisanal to CAD-CAM Blocks: State of the Art of Indirect Composites. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexhepi, I.; Santilli, M.; D’Addazio, G.; Tafuri, G.; Manciocchi, E.; Caputi, S.; Sinjari, B. Clinical Applications and Mechanical Properties of CAD-CAM Materials in Restorative and Prosthetic Dentistry: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruse, N.D.; Sadoun, M.J. Resin-composite blocks for dental CAD/CAM applications. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1232–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papathanasiou, I.; Kamposiora, P.; Dimitriadis, K.; Papavasiliou, G.; Zinelis, S. In vitro evaluation of CAD/CAM composite materials. J. Dent. 2023, 136, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, T.; Tarancón, S.; Pastor, J.Y. On the Mechanical Properties of Hybrid Dental Materials for CAD/CAM Restorations. Polymers 2022, 14, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamerschmitt, R.M.; Tomazinho, P.H.; Camporês, K.L.; Gonzaga, C.C.; da Cunha, L.F.; Correr, G.M. Surface topography and bacterial adhesion of CAD/CAM resin based materials after application of different surface finishing techniques. Braz. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 17, e18135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirxen, C.; Blunck, U.; Preissner, S. Clinical performance of a new biomimetic double network material. Open Dent. J. 2013, 7, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, G.; Emir, F.; Doğdu, C.; Demirel, M.; Özcan, M. Effect of repeated millings on the surface integrity of diamond burs and roughness of different CAD/CAM materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5325–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandurino, M.; Cortili, S.; Coccoluto, L.; Greco, K.; Cantatore, G.; Gherlone, E.F.; Vichi, A.; Paolone, G. Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed vs. Subtractively Manufactured Composite Resins for Permanent Restorations: A Systematic Review. Materials 2025, 18, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Hickel, R.; Reymus, M. 3D Printing in Dentistry-State of the Art. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caussin, E.; Moussally, C.; Le Goff, S.; Fasham, T.; Troizier-Cheyne, M.; Tapie, L.; Dursun, E.; Attal, J.-P.; François, P. Vat Photopolymerization 3D Printing in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Review of Actual Popular Technologies. Materials 2024, 17, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Bona, A.; Cantelli, V.; Britto, V.T.; Collares, K.F.; Stansbury, J.W. 3D printing restorative materials using a stereolithographic technique: a systematic review. Dent Mater. 2021, 37, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, K.B. Evaluation of internal ft of interim crown fabricated with CAD/CAM milling and 3D printing system. J Adv Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 265–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktaş, N.; Bal, C.; İnal, C.B.; Kaynak Öztürk, E.; Bankoğlu Güngör, M. Evaluation of the Fit of Additively and Subtractively Produced Resin-Based Crowns for Primary Teeth Using a Triple-Scan Protocol. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, L.H.; Borella, P.S.; Ferraz, D.C.; Pereira, L.M.; Prudente, M.S.; Santos-Filho, P.C. Influence of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing diamond bur wear on marginal misfit of two lithium disilicate ceramic systems. Oper Dent. 2020, 45, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizci, T.; Bozoğulları, H.N. Effect of thermocycling on the mechanical properties of permanent composite-based CAD-CAM restorative materials produced by additive and subtractive manufacturing techniques. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Hou, X.; Li, K.; Lu, X.; Shi, H.; Lee, E.S.; Jiang, H.B. A Review of 3D Printing in Dentistry: Technologies, Affecting Factors, and Applications. Scanning. 2021, 2021, 9950131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestra, D.; Lowther, M.; Goracci, C.; Mandurino, M.; Cortili, S.; Paolone, G.; Louca, C.; Vichi, A. 3D Printed Materials for Permanent Restorations in Indirect Restorative and Prosthetic Dentistry: A Critical Review of the Literature. Materials 2024, 17, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzimas, K.; Rahiotis, C.; Pappa, E. Biofilm Formation on Hybrid, Resin-Based CAD/CAM Materials for Indirect Restorations: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2024, 17, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Koo, H.; Ren, D. Effects of material properties on bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. J Dent Res. 2015, 94, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, A.S.; Kranz, H.T.; Schneider, M.; Tietze, J.P.; Piwowarcyk, A.; Kuzius, T.; Arnold, W.; Naumova, E.A. Biofilm formation on different dental restorative materials in the oral cavity. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzaniga, G.; Ottobelli, M.; Ionescu, A.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Brambilla, E. Surface properties of resin-based composite materials and biofilm formation: A review of the current literature. Am. J. Dent. 2015, 28, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dutra, D.; Pereira, G.; Kantorski, K.Z.; Valandro, L.F.; Zanatta, F.B. Does Finishing and Polishing of Restorative Materials Affect Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation? A Systematic Review. Oper. Dent. 2018, 43, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Roeder, L.B.; Lei, L.; Powers, J.M. Effect of Surface Roughness on Stain Resistance of Dental Resin Composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2005, 17, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, A.I.; Dumitrescu, R.; Balean, O.; Lalescu, D.V.; Buzatu, B.L.R.; Bolchis, V.; Floare, L.; Utu, D.; Jumanca, D.; Galuscan, A. Enhancing Esthetics in Direct Dental Resin Composite: Investigating Surface Roughness and Color Stability. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3M Filtek Z550 Nano Hybrid Universal Restorative Part 1. File Name: 34-8727-0746-7-A_Filtek Z550 Nano Hybrid Univesal Restorative_Part 1_CEE.pdf. Available online: https://eifu.solventum.com/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- SHOFU Block & Disk HC: Instructions for Use. Available online: https://www.shofu.com/wp-content/uploads/SHOFU-Block-HC-IFU-US.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Vita Enamic®. Technical and Scientific Documentation. Available online: https://www.vita-zahnfabrik.com/en/VITA-ENAMIC-24970.html (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- VarseoSmile TriniQ Instruction for Use. Available online: https://www.bego.com/media-library/downloadcenter/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Cohen, D.K. Glossary of Surface Texture Parameters; Michigan Metrology LLC.: Livonra, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bataweel, O.O.; Roulet, J.F.; Rocha, M.G.; Zoidis, P.; Pereira, P.; Delgado, A.J. Effect of Simulated Tooth Brushing on Surface Roughness, Gloss, and Color Stability of Milled and Printed Permanent Restorative Materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2025, 37, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.C.; Hahnel, S.; König, A.; Brambilla, E. Resin composite blocks for dental CAD/CAM applications reduce biofilm formation in vitro. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Guerrero, P.; Ortiz-Magdaleno, M.; Urcuyo-Alvarado, M.S.; Cepeda-Bravo, J.A.; Leyva-Del Rio, D.; Pérez-López, J.E.; Romo-Ramírez, G.F.; Sánchez-Vargas, L.O. Effect of dental restorative materials surface roughness on the in vitro biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans biofilm. Am. J. Dent. 2020, 33, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prause, E.; Hey, J.; Beuer, F.; Yassine, J.; Hesse, B.; Weitkamp, T.; Gerber, J.; Schmidt, F. Microstructural investigation of hybrid CAD/CAM restorative dental materials by micro-CT and SEM. Dent Mater. 2024, 40, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, R.; Habib, S.R.; AlQahtani, A.; AlHelal, A.A.; Alrabiah, M.; Anwar, S. The Surface Roughness of Contemporary Indirect CAD/CAM Restorative Materials That Are Glazed and Chair-Side-Finished/Polished. Materials 2024, 17, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, M.; Maawadh, A.; Labban, N.; Alnafaiy, S.M.; Alotaibi, H.N.; BinMahfooz, A.M. Effect of Different Surface Treatments on the Surface Roughness and Gloss of Resin-Modified CAD/CAM Ceramics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasbinder, D.J.; Neiva, G.F. Surface Evaluation of Polishing Techniques for New Resilient CAD/CAM Restorative Materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2016, 28, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzinger, M.; Hahnel, S.; Preis, V.; Rosentritt, M. Polishing effects and wear performance of chairside CAD/CAM materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Luo, H.; Yap, A.U.; Tian, F.C.; Wang, X.Y. Effects of polishing press-on force on surface roughness and gloss of CAD-CAM composites. J Oral Sci. 2023, 65, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, G.; Donmez, M.B.; de Paula, M.S.; Akay, C.; Fonseca, M.; Kahveci, Ç.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Yilmaz, B. Surface roughness, optical properties, and microhardness of additively and subtractively manufactured CAD-CAM materials after brushing and coffee thermal cycling. J Prosthodont. 2025, 34, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozoğulları, H.N.; Temizci, T. Evaluation of the Color Stability, Stainability, and Surface Roughness of Permanent Composite-Based Milled and 3D Printed CAD/CAM Restorative Materials after Thermocycling. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rueda, S.; Alsahafi, T.A.; Hammamy, M.; Surathu, N.; Surathu, N.; Lawson, N.C.; Sulaiman, T.A. Roughness and Gloss of 3D-Printed Crowns Following Polishing or Varnish Application. Materials 2025, 18, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, L.I.; Alshadidi, A.A.; Porwal, A.; Al Ahmari, N.M.; Al Moaleem, M.M.; Suhluli, A.M.; Shariff, M.; Shami, A.O. Surface roughness and color measurements of glazed or polished hybrid, feldspathic, and zirconia CAD/CAM restorative materials after hot and cold coffee immersion. BMC Oral Health. 2021, 21, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.A.; Beleidy, M.; El-Din, Y.A. Biocompatibility and Surface Roughness of Different Sustainable Dental Composite Blocks: Comprehensive In Vitro Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 34258–34267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.M.; Farahat, D.S.; Eldars, W.; Osman, M.F. Physico-mechanical properties and bacterial adhesion of resin composite CAD/CAM blocks: An in-vitro study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, N.; El Kateb, M.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Holiel, A.A. Surface roughness, wear, and abrasiveness of printed and milled occlusal veneers after thermomechanical aging. J Prosthet Dent. 2024, 132, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özarslan, M.M.; Büyükkaplan, U.Ş.; Barutcigil, Ç.; Arslan, M.; Türker, N.; Barutcigil, K. Effects of different surface finishing procedures on the change in surface roughness and color of a polymer infiltrated ceramic network material. J Adv Prosthodont. 2016, 8, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özarslan, M.; Bilgili Can, D.; Avcioglu, N.H.; Çalışkan, S. Effect of different polishing techniques on surface properties and bacterial adhesion on resin-ceramic CAD/CAM materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5289–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N.E.; Sahin, Z.; Yikici, C.; Duyan, S.; Kilicarslan, M.A. Bacterial adhesion to composite resins produced by additive and subtractive manufacturing. Odontology 2024, 112, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddanna, G.D.; Valcanaia, A.J.; Fierro, P.H.; Neiva, G.F.; Fasbinder, D.J. Surface Evaluation of Resilient CAD/CAM ceramics after Contouring and Polishing. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021, 33, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, K.; Özdemir, E.; Gönüldaş, F. Effects of immersion in various beverages, polishing and bleaching systems on surface roughness and microhardness of CAD/CAM restorative materials. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kara, D.; Tekçe, N.; Fidan, S.; Demirci, M.; Tuncer, S.; Balcı, S. The efects of various polishing procedures on surface topography of CAD/CAM resin restoratives. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, W.S.; Labban, N.; Maawadh, A.; Alsayed, H.D.; Alshehri, H.; Alrahlah, A.; Alnafaiy, S.M. Influence of Acidic Environment on the Hardness, Surface Roughness and Wear Ability of CAD/CAM Resin-Matrix Ceramics. Materials 2022, 15, 6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, K.; Koizumi, H.; Kodaira, A.; Nogawa, H.; Yoneyama, T. Surface properties and gloss of CAD/CAM composites after toothbrush abrasion testing. J Oral Sci. 2019, 61, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, A.; Stellini, E.; Alageel, O.; Alhotan, A. Comparison of mechanical and surface properties of two 3D printed composite resins for definitive restoration. J Prosthet Dent. 2024, 132, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, F.; Schmidtke, J.; Hahnel, S.; Koenig, A. The influence of different storage media on Vickers hardness and surface roughness of CAD/CAM resin composites. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2023, 34, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grymak, A.; Aarts, J.M.; Cameron, A.B.; Choi, J.J.E. Evaluation of wear resistance and surface properties of additively manufactured restorative dental materials. J Dent. 2024, 147, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koizumi, H.; Saiki, O.; Nogawa, H.; Hiraba, H.; Okazaki, T.; Matsumura, H. Surface roughness and gloss of current CAD/CAM resin composites before and after toothbrush abrasion. Dent Mater J. 2015, 34, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Yoon, H.I.; Yeo, I.L.; Han, J.S. Colour stability and surface properties of high-translucency restorative materials for digital dentistry after simulated oral rinsing. Eur J Oral Sci. 2020, 128, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egilmez, F.; Ergun, G.; Cekic-Nagas, I.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L.V.J. Comparative color and surface parameters of current esthetic restorative CAD/CAM materials. J Adv Prosthodont. 2018, 10, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, J.; Xu, S.; Li, P.; Fouda, A.M.; Yilmaz, B.; Alhotan, A. Surface characteristics, cytotoxicity, and microbial adhesion of 3D-printed hybrid resin-ceramic materials for definitive restoration. J Dent. 2025, 152, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ereifej, N.S.; Oweis, Y.G.; Eliades, G. The Effect of Polishing Technique on 3-D Surface Roughness and Gloss of Dental Restorative Resin Composites. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallis, D.; Pachiou, A.; Dimitriadi, M.; Sykaras, N.; Kourtis, S. A Comparative In Vitro Study of Materials for Provisional Restorations Manufactured With Additive (3Dprinting), Subtractive (Milling), and Conventional Techniques. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2025, 37, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlus, P.; Reizer, R.; Wieczorowski, M. Functional Importance of Surface Texture Parameters. Materials 2021, 14, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, R.J.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Hasan, J.; Ivanova, E.P. Surface topographical factors influencing bacterial attachment. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 179-182, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, K.J.; Blunt, L. Three-dimensional surface topography, 2nd ed.; Penton Press: London, England, 2000; pp. 143–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Loch, C.; Waddell, J.N.; Tompkins, G.; Schwass, D. Surface Characteristics and Biofilm Development on Selected Dental Ceramic Materials. Int. J. Dent. 2017, 2017, 7627945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, C.M.; Lambrechts, P.; Quirynen, M. Comparison of Surface Roughness of Oral Hard Materials to the Threshold Surface Roughness for Bacterial Plaque Retention: A Review of the Literature. Dent. Mater. 1997, 13, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzeys, E.; Vercruyssen, C.; Duca, R.C.; Saha, P.S.; Godderis, L.; Vanoirbeek, J.; Peumans, M.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Van Landuyt, K.L. Monomer release from direct and indirect adhesive restorations: A comparative in vitro study. Dent Mater. 2020, 36, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, U.; Rossegger, E.; Schlögl, S. A Review of Multi-Material 3D Printing of Functional Materials via Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.A.; Ahmed, W.; Khalid, M.Y.; Koç, M. Vat photopolymerization of polymers and polymer composites: Processes and applications. Addit Manuf. 2021, 47, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.F.; Migonney, V.; Ruse, N.D.; Sadoun, M. Resin composite blocks via high-pressure high-temperature polymerization. Dent Mater. 2012, 28, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Peng, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, L. Development and status of resin composite as dental restorative materials. J Appl Polym Sci. 2019, 136, 48180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.; Schmidtke, J.; Schmohl, L.; Schneider-Feyrer, S.; Rosentritt, M.; Hoelzig, H.; Kloess, G.; Vejjasilpa, K.; Schulz-Siegmund, M.; Fuchs, F.; et al. Characterisation of the Filler Fraction in CAD/CAM Resin-Based Composites. Materials 2021, 14, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohs Hardness. Available online: https://gnpgraystar.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MohsHardness-1.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- VarseoSmile TriniQ Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://usa.bego.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/VarseoSmile-TriniQ_793559_USA_US_V-1_2_0_SDB.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- VarseoSmile TriniQ Compendium. Available online: https://www.bego.com/fileadmin/user_downloads/Mediathek/3D-Druck/Scientific-Studies/VarseoSmileTriniQ/EN/de_81028_0000_br_en.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Grzebieluch, W.; Kowalewski, P.; Grygier, D.; Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Jurczyszyn, K. Printable and Machinable Dental Restorative Composites for CAD/CAM Application—Comparison of Mechanical Properties, Fractographic, Texture and Fractal Dimension Analysis. Materials 2021, 14, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, N.; Topçu, F.T.; Karaoğlanoğlu, S.; Oktay, E.A.; Erdemir, U. Effect of finishing and polishing systems on the surface roughness and color change of composite resins. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021, 13, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmarsafy, S.M.; Abdelwahab, S.A.; Hussein, F. Influence of polishing systems on surface roughness of four resin composites subjected to thermocycling aging. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2023, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, A.G.; Rocha, R.S.; Spinola, M.D.S.; Batista, G.R.; Bresciani, E.; Caneppele, T.M.F. Surface smoothness of resin composites after polishing-A systematic review and network meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Eur J Oral Sci. 2023, 131, e12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, L.; Martel, C.; Crépeau, H.; Vargas, M.A. Influence of polishing systems on surface roughness of composite resins: polishability of composite resins. Oper Dent. 2019, 44, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, S.R. The art and science of abrasive finishing and polishing in restorative dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 1998, 42, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Hodson, N.; Altaie, A. Polishing systems for modern aesthetic dental materials: a narrative review. Br Dent J. 2024, 237, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flury, S.; Diebold, E.; Peutzfeldt, A.; Lussi, A. Effect of artificial toothbrushing and water storage on the surface roughness and micromechanical properties of tooth-colored CAD-CAM materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2017, 117, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintze, S.D.; Forjanic, M.; Rousson, V. Surface roughness and gloss of dental materials as a function of force and polishing time in vitro. Dent Mater. 2006, 22, 146–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzenbach, T.; Helbig, R.; Hannig, C.; Hannig, M. Bioadhesion in the oral cavity and approaches for biofilm management by surface modifications. Clin Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 4237–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, F.; Gittens, R.A.; Scheideler, L.; Marmur, A.; Boyan, B.D.; Schwarz, Z.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J. A review on the wettability of dental implant surfaces I: Theoretical and experimental aspects. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2894–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, T.; Ye, Z.; Fischer, N.G.; Skoe, E.P.; Echeverría, C.; Wu, J.; Aparicio, C. Physical-chemical interactions between dental materials surface, salivary pellicle and Streptococcus gordonii. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020, 190, 110938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, G.; Eliades, T.; Vavuranakis, M. General aspects of biomaterial surface alterations following exposure to biologic fluids. In Dental Materials In Vivo: Aging and Related Phenomena, 1st ed.; Eliades, G., Eliades, T., Brantley, W.A., Walts, D.C., Eds.; Quintessence Publishing Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cassie, A.B.D.; Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans Faraday Soc. 1944, 40, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, R.N. Resistance of solid surfaces to wetting by water. Ind Eng Chem. 1936, 28, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Bawazir, M.; Dhall, A.; Kim, H.E.; He, L.; Heo, J.; Hwang, G. Implication of Surface Properties, Bacterial Motility, and Hydrodynamic Conditions on Bacterial Surface Sensing and Their Initial Adhesion. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 643722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Abbreviation | Shade | Composition | Manufacturer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filtek Z550 Direct composite restorative LOT: 11225283 [30] |

FK | A2 | Organic matrix: Bis-GMA, Bis-EMA, TEGDMA, PEGDMA, UDMA Inorganic fillers: 82 wt% inorganic fillers (non-agglomerated/ non-aggregated 20nm surface-modified silica particles, surface-modified zirconia/silica 0.1-10μm) |

3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA |

|

| Shofu HC block CAD/CAM milled, resin-composite LOT: 111501 [31] |

SH | A2 HT |

Organic matrix: UDMA, TEGDMA Inorganic fillers: 61 wt% inorganic fillers (silica, zirconium silicate, and microfumed silica) |

Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan | |

| Vita Enamic CAD/CAM milled, hybrid ceramic LOT: 94630 [32] |

VE | 2M2 HT |

Organic matrix: UDMA, TEGDMA Inorganic fillers: 86 wt% inorganic phase (primarily silicon dioxide and aluminum oxide and secondarily sodium, potassium, calcium oxide, boron trioxide and zirconia) |

VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany |

|

| VarseoSmile TriniQ CAD/CAM 3D-printed esin-composite LOT: 601372 [33] |

TQ | A2 Dentin |

Organic matrix: Esterification products of 4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol, ethoxylated, and 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid: 55–80 wt%, benzeneacetic acid, alpha-oxo-, methyl ester < 5 wt%, diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide < 2.5 wt% Inorganic fillers: ceramic fillers |

Bego, Bremen, Germany |

| Polishing Systems | Composition | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Sof-Lex Finishing and Polishing System | Aluminum oxide abrasive particles (coarse, medium, fine, superfine) | 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA |

| Super Snap | Aluminum oxide and silicon carbide particles serving as abrasive grains. | Shofu Inc, Kyoto, Japan |

| DuraPolish | 73% by weight aluminum oxide | Shofu Inc, Kyoto, Japan |

| DuraPolish DIA | 67% diamond powder with ultrafine particle sizes smaller than 1μm | Shofu Inc, Kyoto, Japan |

| VitaEnamic Polishing Set Clinical (two-step polishing system) | Silicon carbide abrasive particles for pre-polishing and diamond particles as abrasive grains for high-gloss polishing | VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany |

| VitaPolish Hybrid | Diamond polishing paste Mixture of fatty acids, paraffin and inorganic abrasive substances |

VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany |

| Opal L | High-luster polishing paste | Renfert GmbH, Hilzingen, Germany |

| Universal Polishing Paste | Water, aluminium oxide abrasives, solvent (hydrocarbons C10-C13), ammonium oleate, cocamide diethanolamine, ammonium hydroxide, pigments | Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Lichtenstein |

| Silicon Carbide papers (800-, 1200-, 2400, 4000-grit) | Adhesive bonded silicon carbide grains | Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| MD-NAP | Synthetic, short nap/diamond or oxide polishing , ≤ 1μm grain size | Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| DiaPro Nap R | Water-based, optimized with polycrystalline diamond solution / 1μm grain size | Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark |

| MATERIAL GROUP | Sa (nm) | Sz (nm) | Sdr (%) | Sds (1/mm2) | Sc (nm3 /nm2) | Sv (nm3 /nm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MANUALLY POLISHED | ||||||

| FK | 163.45 (13.12) a, A | 1896.26 (270.60) a, A |

5.78 (0.89) a, A |

18568.52 (1437.13) a, A |

251.83 (40.11) a, A |

22.92 (4.64) a, A |

| SH | 60.63 (8.73) b, A |

655.01 (103.37) b, A |

0.42 (0.06) b, A |

23348.49 (2443.29) b, A |

86.67 (15.72) b, A |

10.00 (1.41) b, A |

| VE | 88.72 (21.78) c, A |

1280.12 (236.63) c, A |

1.80 (0.92) c, A |

22521.08 (1182.05) b, A |

110.83 (28.25) b, A |

17.83 (3.66) c, A |

| TQ | 103.49 (13.11) c, A |

1043.51 (256.39) c, A |

1.68 (0.64) c, A |

21325.56 (980.33) b, A |

144.58 (19.16) c, A |

17.17 (2.44) c, A |

| METALLOGRAPHICALLY POLISHED | ||||||

| FK | 57.19 (6.67) a, c, B |

795.05 (78.18) a, B |

0.91 (0.17) a, B |

18797.58 (1406.55) a, A |

86.91 (10.86) a, B |

8.83 (0.94) a, B |

| SH | 59.69 (9.24) a, A |

668.62 (107.13) b, A |

0.46 (0.11) b, A |

27041.08 (2844.27) b, B |

80.17 (15.02) a, c, A |

10.80 (1.14) b, A |

| VE | 35.37 (9.82) b, B |

904.57 (262.69) a, B |

0.72 (0.36) a, b, B |

22914.60 (4691.69) b, A |

39.41 (11.97) b, B |

8.86 (1.93) a, B |

| TQ | 48.86 (10.30) c, B |

754.08 (205.63) a, b, B |

0.74 (0.32) a, b, B |

25507.03 (4202.46) b, B |

65.66 (17.61) c, B |

8.67 (0.98) a, B |

| MATERIAL GROUP | Contact angle (o) Manually polished |

Contact angle (o) Metallographically polished |

|---|---|---|

| FK | 69.51 (1.87) a, A | 52.65 (1.80) a, B |

| SH | 75.75 (2.39) b, A | 53.02 (1.19) a, B |

| VE | 86.32 (1.23) c, A | 47.16 (1.80) b, B |

| TQ | 79.08 (1.96) d, A | 66.26 (1.06) c, B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).