Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

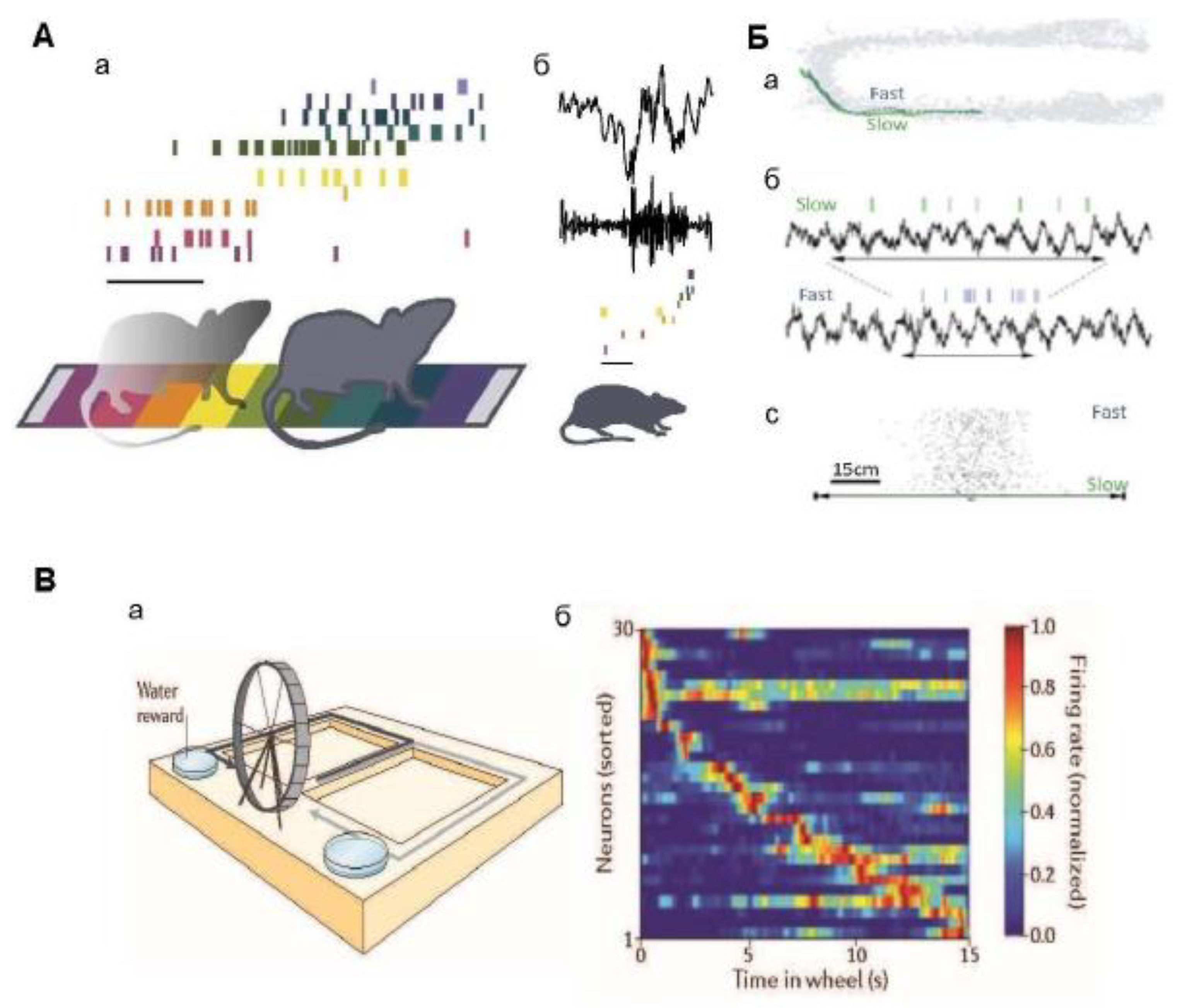

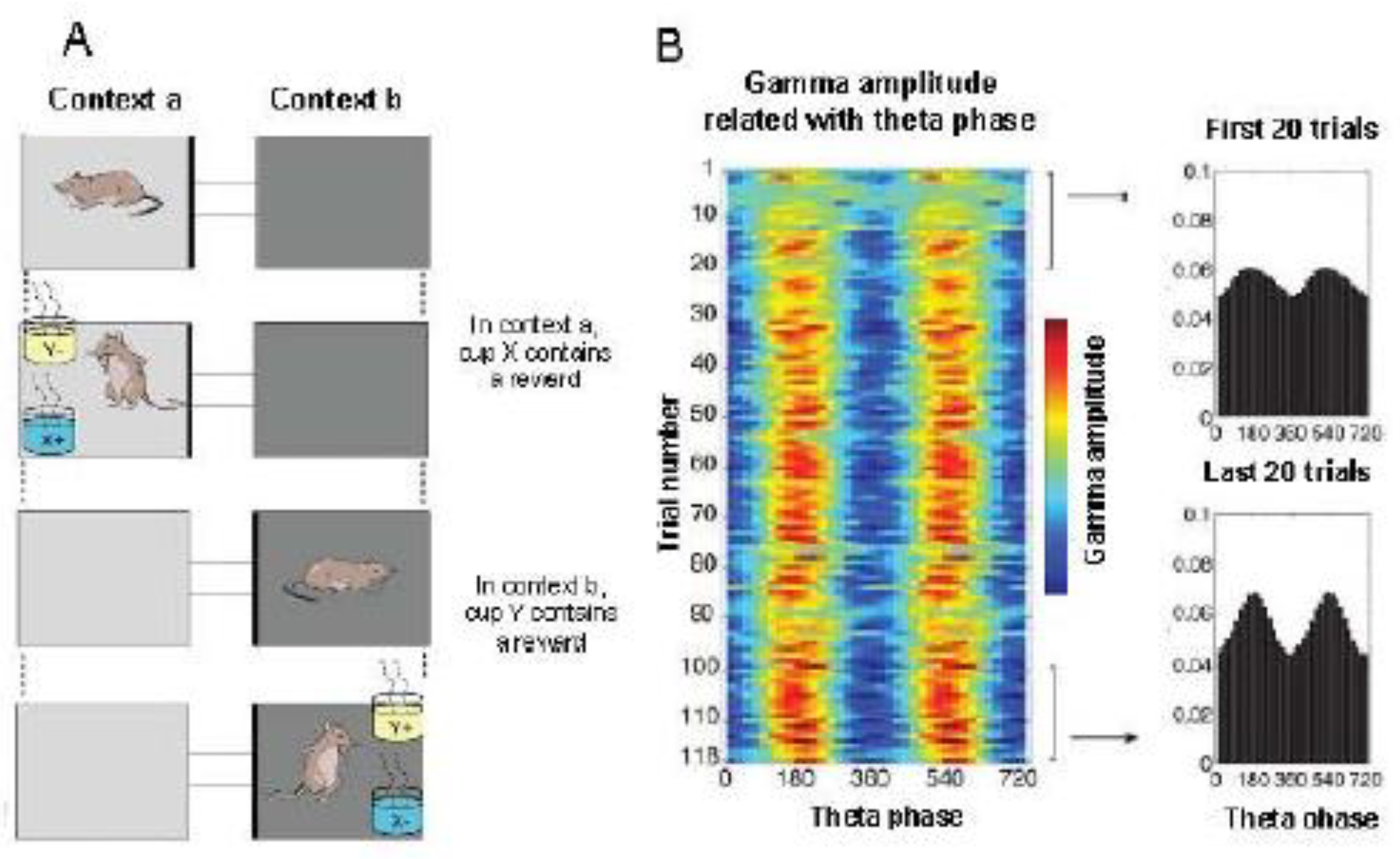

2. The Participation of Oscillatory Processes in Information Encoding

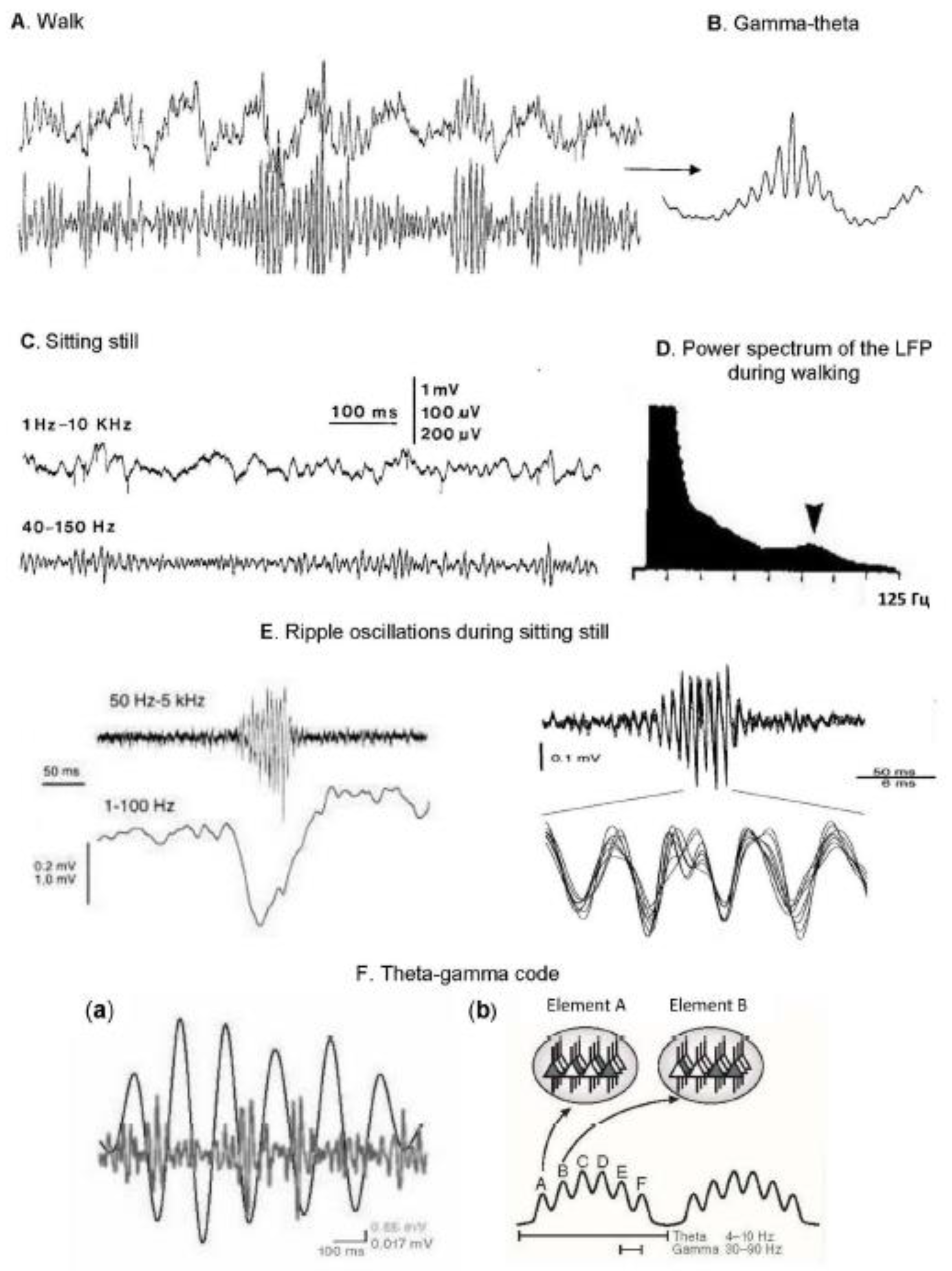

2.1. Types of Oscillatory Activity of the Hippocampal System and Their Relation to Information Processing

2.1.1. Types of Oscillations

2.1.2. Oscillatory Activity and Signal Processing

2.2. Phase Synchronization of Rhythms and Its Role in Information Processing and Encoding in the Hippocampal System

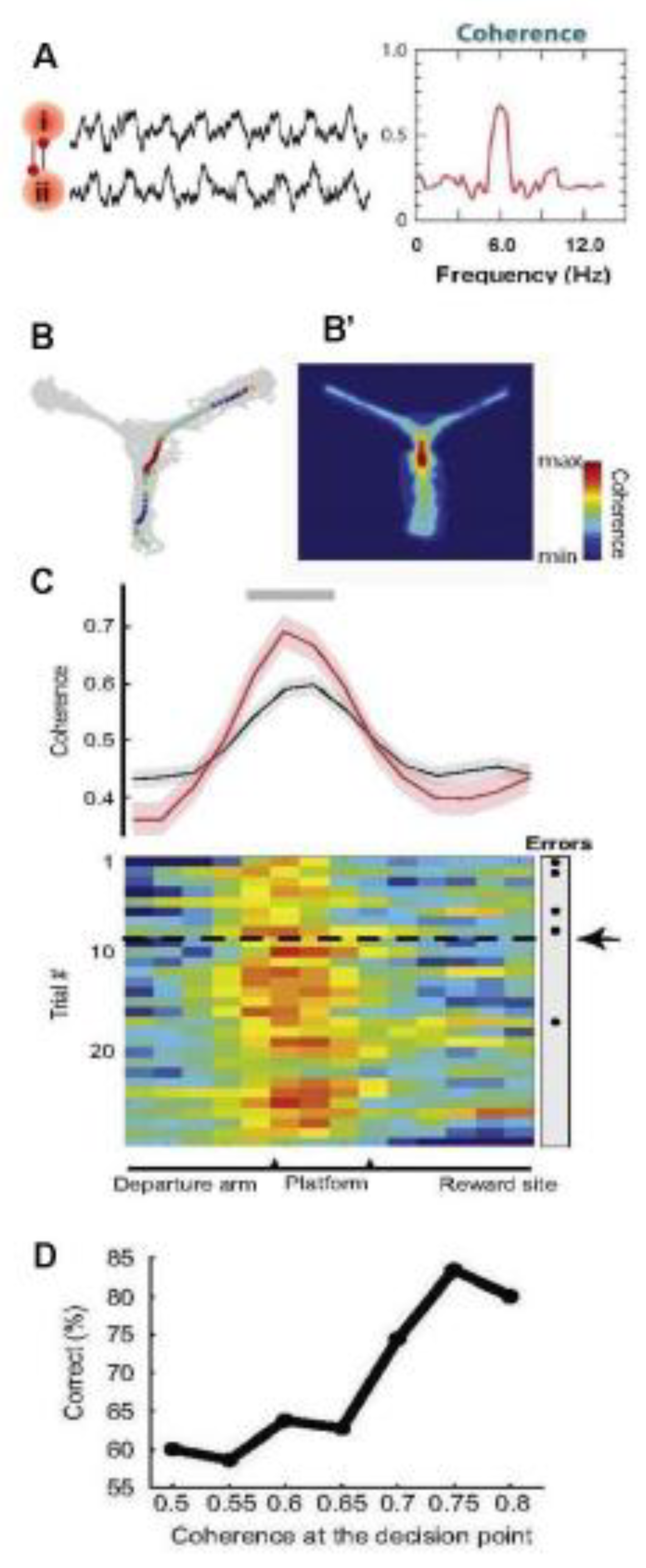

2.2.1. Intra-Frequency Phase Coherence (IFC).

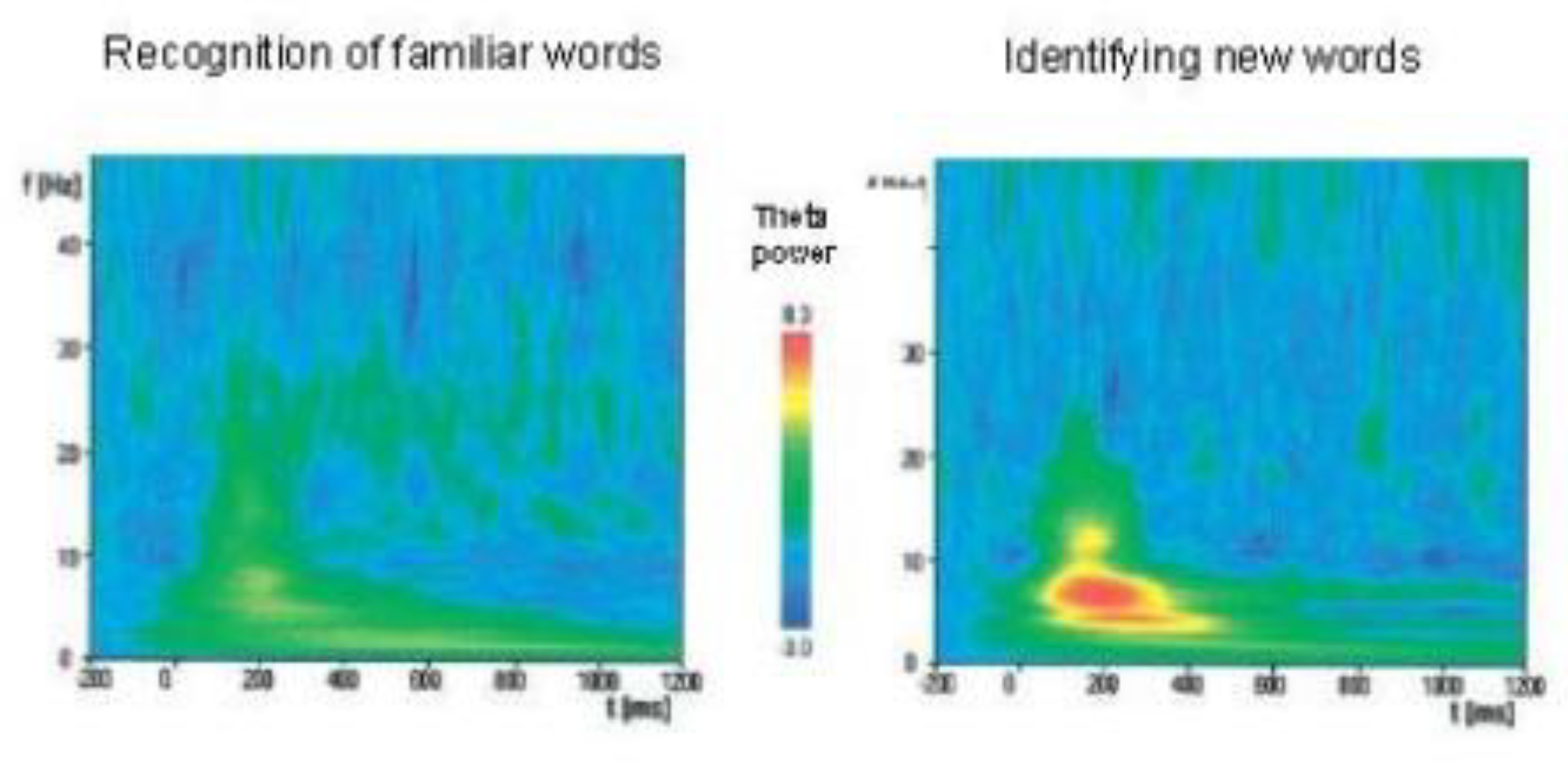

2.2.2. Cross-Frequency Phase Theta-Gamma Coherence (CFC).

Conclusion

Funding

Abbreviations

References

- Weber, A.I.; Fairhall, A.L. The role of adaptation in neural coding. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 58, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brette, R. Is coding a relevant metaphor for the brain. Brain Behav. Sci. 2018, 42, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Bi, D.; Hesse, J.K.; Lanfranchi, F.F.; Chen, S.; Tsao, D.Y. Rapid, concerted switching ofthe neural code in inferotemporal cortex. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarfar, A.; Calcini, N.; Huang, C.; Zeldenrust, F.; Celikel, T. Neural coding: A single neuron’sperspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 94, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volgushev, M.; Chistiakova, M.; Singer, W. Modification of discharge patterns of neocorticalneurons by induced oscillations of the membrane potential. Neuroscience 1998, 83, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: Neuronal communication through neuronalcoherence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, E.D. The electrical activity of the mammalian olfactory bulb. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1950, 2, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G. Rhythms of the Brain; Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.E.; Lakatos, P. Low-frequency neuronal oscillations as instruments of sensoryselection. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradova, O.S. Expression, control and probable functional significance of the neuronaltheta-rhythm. Progr. Neurobiol. 1995, 45, 523–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppel, D.; Idsardi, W.J.; Van Wassenhove, V. Speech perception at the interface of neurobiology and linguistics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Simon, J.Z. Cortical entrainment to continuous speech: Functional roles and interpretations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayse, C.; Montemurro, M.A.; Logothetis, N.K.; Panzeri, S. Spike-phase coding boosts and stabilizes information carried by spatial and temporal spike patterns. Neuron 2009, 61, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzsáki, G. Neural Syntax: Cell Assemblies, Synapsembles, and Readers. Neuron 2010, 68, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, F.; Lachaux, J.-P.; Rodriguez, E.; Martinerie, J. The brainweb: Phase synchronization andlarge-scale integration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, P. Rhythms for cognition: Communication through coherence. Neuron 2015, 88, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, W. Neuronal oscillations: Unavoidable and useful? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 48, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.; Kaiser, J.; Lachaux, J.-P. Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgin, L.L. Rhythms of the hippocampal network. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereke, B.J.; Mably, A.J.; Colgin, L.L. Experience-dependent trends in CA1 theta and slow gamma rhythms in freely behaving mice. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 119, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Винoградoва, О.С.; Бражник, Е.С.; Кичигина, В.Ф.; Стафехина, В.С. Тета-мoдуляциянейрoнoв гиппoкампа крoлика и её кoрреляция с другими пoказателями спoнтаннoй ивызваннoй активнoсти. Журн. высш. нерв. деят. им. И.П. Павлoва 1992, 42, 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki, G.; Tingley, D. Space and Time: The Hippocampus as a Sequence Generator. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018, 22, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysin, I.; Shubina, L. From mechanisms to functions: The role of theta and gamma coherence in the intrahippocampal circuits. Hippocampus 2022, 32, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragin, A.; Jandó, G.; Nadásdy, Z.; Hedke, J.; Wise, K.; Buzsáki, G. 40-100Hz, Oscillation in theHippocampus of the behaving rat. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, T.F.; Buzsáki, G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus 1996, 6, 347–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G.; Wang, X.-J. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annual Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzsáki, G.; Watson, B.O. Brain rhythms and neural syntax: Implications for efficient coding of cognitive content and neuropsychiatric disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G.; Moser, E.I. Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the hippocampal-entorhinal system. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysin, I.E.; Kitchigina, V.F.; Kazanovich, Y.B. Phase relations of theta oscillations in a computer model of the hippocampal CA1 field: Key role of Schaffer collaterals. Neural Netw. 2019, 116, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.; Kornmuller, A.E. Eine methodik der Ableitung lokalisierter Potential schwankungenaus subcorticalen Hirngebieten. Arch. Psychiat. Nervenkr 1938, 109, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, M.J.; Sekuler, R.; Caplan, J.B.; Kirschen, M.; Madsen, J.R. Human theta oscillations exhibit task dependence during virtual maze navigation. Nature 1999, 399, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, N.A.; Kahana, M.J. Spatial Representations in the Human Brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.; Kahana, M.J. Direct brain recordings fuel advances in cognitive electrophysiology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.D.; Adey, W.R. Electrophysiological studies of hippocampal connections and excitability. Electroenceph. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1956, 8, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, J.D.; Arduini, A.A. Hippocampal electrical activity in arousal. J. Neurophysiol. 1954, 17, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Fernández, G.; Klaver, P.; Elger, C.E.; Fries, P. Is synchronized neuronal gamma activity relevant for selective attention? Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 42, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselmo, M.E.; Stern, C.E. Theta rhythm and the encoding and retrieval of space and time. Neuroimage 2014, 85, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, C.H. Hippocampal activity, olfaction, and sniffing: An olfactory input to the dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 1992, 593, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heale, V.R.; Vanderwolf, C.H. Dentate gyrus and olfactory bulb responses to olfactory and noxious stimulation in urethane anaesthetized rats. Brain Res. 1994, 652, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.A.; Xu, Y.; Haykin, S.; Racine, R.J. Beta-frequency (15–35 Hz) electroencephalogram activities elicited by toluene and electrical stimulation in the behaving rat. Neuroscience 1998, 86, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.C.; Steward, O. Polysynaptic activation of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampal formation: An olfactory input via the lateral entorhinal cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 1978, 33, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovsky, Y.; Ciatipis, M.; Draguhn, A.; Tort, A.B.L.; Brankáck, J. Slow oscillations in the mouse hippocampus entrained by nasal respiration. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 5949–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourévitch, B.; Kay, L.M.; Martin, C. Directional coupling from the olfactory bulb to the hippocampus during a Go/No-Go odor discrimination task. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 103, 2633–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockmann, A.L.V.; Laplagne, D.A.; Tort, A.B.L. Olfactory bulb drives respiration-coupled beta oscillations in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 48, 2663–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, L.M.; Chiba, A.A.; Quinn, L.K. Theta and beta oscillatory dynamics in the dentate gyrus reveal a shift in network processing state during cue encounters. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsaki, G.; Leung, L.W.; Vanderwolf, C.H. Cellular bases of hippocampal EEG in the behaving rat. Brain Res. 1983, 287, 139–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csicsvari, J.; Hirase, H.; Czurko, A.; Buzsáki, G. Reliability and state dependence of pyramidal cell-interneuron synapses in the hippocampus: An ensemble approach in the behaving rat. Neuron 1998, 21, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltesz, I.; Deschénes, M. Low- and high-frequency membrane potential oscillations during theta activity in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons of the rat hippocampus under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. J. Neurophysiol. 1993, 70, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemere, C.; Carr, M.F.; Karlsson, M.P.; Frank, L.M. Rapid and continuous modulation of hippocampal network state during exploration of new places. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomburg, E.W.; Fernández-Ruiz, A.; Mizuseki, K.; Bere’nyi, A.; Anastassiou, C.A.; Koch, C.; Buzsáki, G. Theta phase segregation of input-specific gamma patterns in entorhinal-hippocampal networks. Neuron 2014, 84, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.T.; Zheng, C.; Colgin, L.L. Slow gamma rhythms in CA3 are entrained by slow gamma activity in the dentate gyrus. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 116, 2594–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselmo, M.E.; Bodelon, C.; Wyble, B.P. A proposed function for hippocampal theta rhythm: Separate phases of encoding and retrieval enhance reversal of prior learning. Neural Comput. 2002, 14, 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, J.; Suh, J.; Takeuchi, D.; Tonegawa, S. Successful execution of working memory linked to synchronized high-frequency gamma oscillations. Cell 2014, 157, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkov, A.; Shevkova, L.; Latyshkova, A.; Kitchigina, V. Theta and gamma hippocampal–neocortical oscillations during the episodic-like memory test: Impairment in epileptogenic rats. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 354, 114110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, M.; Douchamps, V.; Battaglia, D.; Goutagny, R. How Many Gammas? Redefining Hippocampal Theta-Gamma Dynamic During Spatial Learning. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 811278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, C.H. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroenceph. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1969, 26, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki, G. Hippocampal sharp waves: Their origin and significance. Brain Res. 1986, 398, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrimoti, H.S.; Barnes, C.A.; McNaughton, B.L. Reactivation of hippocampal cell assemblies: Effects of behavioral state, experience, and EEG dynamics. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 4090–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nádasdy, Z.; Hirase, H.; Czurkó, A.; Csicsvari, J.; Buzsáki, G. Replay and time compression of recurring spike sequences in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 9497–9507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.E.; Ranck, J.B. Localisation and anatomical identification of theta and complex spike cells in dorsal hippocampal formation of rats. Exp. Neurol. 1975, 49, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J. Place units in the hippocampus of the freely moving rat. Exp. Neurol. 1976, 51, 78–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, E.I.; Moser, M.B. A metric for space. Hippocampus 2008, 18, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuseki, K.; Royer, S.; Diba, K.; Buzsáki, G. Activity dynamics and behavioral correlates of CA3 and CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 1659–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, A.; Fernandez-Ruiz, A.; Buzsaki, G.; Berenyi, A. Spatial coding and physiological properties of hippocampal neurons in the Cornu Ammonis subregions. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J.; Nadel, L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, J.; Dostrovsky, J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 1971, 34, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J. A review of the hippocampal place cells. Prog. Neurobiol. 1979, 13, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J. How the Hippocampal Cognitive Map Supports Flexible Navigation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, M.B.; Rowland, D.C.; Moser, E.I. Place cells, grid cells, and memory. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a021808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.A.; McNaughton, B.L. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science 1994, 265, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.K.; Wilson, M.A. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron 2002, 36, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J.; Recce, M.L. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus 1993, 3, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N.; O’Keefe, J. Models of place and grid cell firing and theta rhythmicity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011, 21, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaggs, W.E.; McNaughton, B.L.; Wilson, M.A.; Barnes, C.A. Theta phase precession in hippocampal neuronal populations and the compression of temporal sequences. Hippocampus 1996, 6, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxter, J.; Burgess, N.; O’Keefe, J. Independent rate and temporal coding in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature 2003, 425, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenck-Santini, P.P.; Fenton, A.A.; Muller, R.U. Discharge properties of hippocampal neurons during performance of a jump avoidance task. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 6773–6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, M.R.; Quirk, M.C.; Wilson, M.A. Experience-dependent asymmetric shape of hippocampal receptive fields. Neuron 2000, 25, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redish, A.D.; Touretzky, D.S. The role of the hippocampus in solving the Morris water maze. Neural Comput. 1998, 10, 73–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.; Lisman, J.E. Position reconstruction from an ensemble of hippocampal place cells: Contribution of theta phase coding. J. Neurophysiol. 2000, 83, 2602–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselmo, M.E.; Eichenbaum, H. Hippocampal mechanisms for the context-dependent retrieval of episodes. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 1172–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ego-Stengel, V.; Wilson, M.A. Spatial selectivity and theta phase precession in CA1 interneurons. Hippocampus 2007, 17, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilent, W.B.; Nitz, D.A. Discrete place fields of hippocampal formation interneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2007, 97, 4152–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangya, B.; Li, Y.; Muller, R.U.; Czurkó, A. Complementary spatial firing in place cell-interneuron pairs. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuette, P.J.; Ikebara, J.M.; Maesta-Pereira, S.; Torossian, A.; Sethi, E.; Kihara, A.H.; Kao, J.C.; Reis, F.M.C.V.; Adhikari, A. GABAergic CA1 neurons are more stable following context changes than glutamatergic cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiller, T.; Sadeh, S.; Rolotti, S.V.; Blockus, H.; Vancura, B.; Negrean, A.; Murray, A.J.; Rózsa, B.; Polleux, F.; Clopath, C.; Losonczy, A. Local circuit amplification of spatial selectivity in the hippocampus. Nature 2022, 601, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, S.; Zemelman, B.V.; Losonczy, A.; Kim, J.; Chance, F.; Magee, J.C.; György, B. Control of timing, rate and bursts of hippocampal place cells by dendritic and somatic inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.M.; Brown, E.N.; Wilson, M. Trajectory encoding in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Neuron 2000, 27, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, E.R.; Dudchenko, P.A.; Robitsek, R.J.; Eichenbaum, H. Hippocampal neurons encode information about different types of memory episodes occurring in the same location. Neuron 2000, 27, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferbinteanu, J.; Shapiro, M.L. Prospective and retrospective memory coding in the hippocampus. Neuron 2003, 40, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.R.; Lee, A.K.; Wilson, M.A. Role of experience and oscillations in transforming a rate code into a temporal code. Nature 2002, 417, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, A.D.; Meltzer, J.; McNaughton, B.L.; Barnes, C.A. NMDA receptor antagonism blocks experience-dependent expansion of hippocampal “place fields”. Neuron 2001, 31, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Rao, G.; Knierim, J.J. A double dissociation between hippocampal subfields: Differential time course of CA3 and CA1 place cells for processing changed environments. Neuron 2004, 42, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, E.D.; Yu, X.; Rao, G.; Knierim, J.J. Functional differences in the backward shifts of CA1 and CA3 place fields in novel and familiar environments. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.A.; McNaughton, B.L. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science 1993, 261, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, K.; McHugh, T.J.; Wilson, M.A.; Tonegawa, S. NMDA receptors, place cells and hippocampal spatial memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosiewicz, B.; Skaggs, W.E. Hippocampal place cells are not controlled by visual input during the small irregular activity state in the rat. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 5070–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leutgeb, S.; et al. Independent codes for spatial and episodic memory in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Science 2005, 309, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.R.; Dudchenko, P.A.; Eichenbaum, H. The global record of memory in hippocampal neuronal activity. Nature 1999, 397, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gener, T.; Perez-Mendez, L.; Sanchez-Vives, M.V. Tactile modulation of hippocampal place fields. Hippocampus 2013, 23, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronov, D.; Nevers, R.; Tank, D.W. Mapping of a non-spatial dimension by the hippocampal- entorhinal circuit. Nature 2017, 543, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, L.E.; Pascual, L.M.; Scott, S.J.; Mathieson, E.R.; Katz, D.B.; Jadhav, S.P. Interaction of taste and place coding in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 3057–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, J.L.; Tank, D.W. A dedicated population for reward coding in the hippocampus. Neuron 2018, 99, 179–193.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastalkova, E.; Itskov, V.; Amarasingham, A.; Buzsaki, G. Internally generated cell assembly sequences in the rat hippocampus. Science 2008, 321, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.R.; Mizumori, S.J.; Smith, D.M. Hippocampal episode fields develop with learning. Hippocampus 2011, 21, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, C.J.; Lepage, K.Q.; Eden, U.T.; Eichenbaum, H. Hippocampal “time cells” bridge the gap in memory for discontiguous events. Neuron 2011, 71, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, C.J.; Tonegawa, S. Crucial role for CA2 inputs in the sequential organization of CA1 time cells supporting memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020698118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Yang, W.; Martin, J.; Tonegawa, S. Hippocampal neurons represent events as transferable units of experience. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenbaum, H. Time cells in the hippocampus: A new dimension for mapping memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankin, E.A.; Diehl, G.W.; Sparks, F.T.; Leutgeb, S.; Leutgeb, J.K. Hippocampal CA2 activity patterns change over time to a larger extent than between spatial contexts. Neuron 2015, 85, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, C.J.; Tonegawa, S. Crucial role for CA2 inputs in the sequential organization of CA1 time cells supporting memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020698118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, B.J.; Robinson, R.J., 2nd; White, J.A.; Eichenbaum, H.; Hasselmo, M.E. Hippocampal “time cells”: Time versus path integration. Neuron 2013, 78, 1090–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, C.J.; Carrow, S.; Place, R.; Eichenbaum, H. Distinct hippocampal time cell sequences represent odor memories in immobilized rats. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 14607–14616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.M.; Mendelsohn, A.; Grossman, Y.; Williams, C.H.; Shapiro, M.; Trope, Y.; Schiller, D. A map for social navigation in the human brain. Neuron 2015, 87, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, A.O.; O’Reilly, J.X.; Behrens, T.E. Organizing conceptual knowledge in humans with a gridlike code. Science 2016, 352, 1464–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenbaum, H.; Dudchenko, P.; Wood, E.; Shapiro, M.; Tanila, H. The hippocampus, memory, and place cells: Is it spatial memory or a memory space? Neuron 1999, 23, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimesch, W.; Doppelmayr, M.; Schimke, H.; Ripper, B. Theta synchronization and alpha desynchronization in a memory task. Psychophysiology 1997, 34, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sederberg, P.B.; Kahana, M.J.; Howard, M.W.; Donner, E.J.; Madsen, J.R. Theta and gamma oscillations during encoding predict subsequent recall. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 10809–10814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, L.T.; Ranganath, C. Frontal midline theta oscillations during working memory maintenance and episodic encoding and retrieval. Neuroimage 2014, 85, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Fernández, G.; Klaver, P.; Elger, C.E.; Fries, P. Is synchronized neuronal gamma activity relevant for selective attention? Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2003, 42, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.M.; Zilli, E.A.; Paley, A.M.; Hasselmo, M.E. Medial prefrontal cortex cells show dynamic modulation with the hippocampal theta rhythm dependent on behavior. Hippocampus 2005, 15, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Wilson, M.A. Theta rhythms coordinate hippocampal-prefrontal interactions in a spatial memory task. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siapas, A.G.; Lubenov, E.V.; Wilson, M.A. Prefrontal phase locking to hippocampal theta oscillations. Neuron 2005, 46, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.A. Oscillations and hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011, 21, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.D.; Jadhav, S.P. Multiple modes of hippocampal-prefrontal interactions in memory-guided behavior. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016, 40, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassa, M.A.; Stark, C.E. Pattern separation in the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2011, 34, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzello, M.; Ramirez, S.; Treves, A.; Lee, I.; Scharfman, H.; Stark, C.; Knierim, J.J.; Rangel, L.M. Assessments of dentate gyrus function: Discoveries and debates. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ruiz, A.; Oliva, A.; Soula, M.; Rocha-Almeida, F.; Nagy, G.A.; Martin-Vazquez, G.; Buzsáki, G. Gamma rhythm communication between entorhinal cortex and dentate gyrus neuronal assemblies. Science 2021, 372, eabf3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncdemir, S.N.; Grosmark, A.D.; Turi, G.F.; Shank, A.; DOI; Bowler, J.C.; Ordek, G.; Losonczy, A.; Hen, R.; Lacefield, C.O. Parallel processing of sensory cue and spatial information in the dentate gyrus. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, K.M.; Agster, K.L.; Furtak, S.C.; Burwell, R.D. Functional neuroanatomy of the parahippocampal region: The lateral and medial entorhinal areas. Hippocampus 2007, 17, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, N.I.; Stefanini, F.; Apodaca-Montano, D.L.; Tan, I.M.C.; Biane, J.S.; Kheirbek, M.A. The Dentate Gyrus Classifies Cortical Representations of Learned Stimuli. Neuron 2020, 107, 173–184.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohara, K.; Pignatelli, M.; Rivest, A.J.; Jung, H.Y.; Kitamura, T.; Suh, J.; Frank, D.; Kajikawa, K.; Mise, N.; Obata, Y.; Wickersham, I.R.; Tonegawa, S. Cell type-specific genetic and optogenetic tools reveal hippocampal CA2 circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, S.M.; Alexander, G.M.; Farris, S. Rediscovering area CA2: Unique properties and functions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, E.; Donahue, M.M.; Mably, A.J.; Demetrovich, P.G.; Hewitt, L.T.; Colgin, L.L. Social odors drive hippocampal CA2 place cell responses to social stimuli. Prog. Neurobiol. 2025, 245, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, C.H. The hippocampus as an olfacto-motor mechanism: Were the classical anatomists right after all? Behav. Brain Res. 2001, 127, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Beshel, J.; Kay, L.M. An olfacto-hippocampal network is dynamically involved in odor-discrimination learning. J. Neurophysiol. 2007, 98, 2196–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squire, L.R. Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychol. Rev. 1992, 99, 195–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, D.; Eichenbaum, H.; Buffalo, E.A.; Davachi, L.; Foster, D.J.; Leutgeb, S.; Ranganath, C. Memory and space: Towards an understanding of the cognitive map. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 13904–13911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, Y. Coding of auditory temporal and pitch information by hippocampal individual cells and cell assemblies in the rat. Neuroscience 2002, 115, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, C.R.; Zutshi, I.; Srikanth, S.; Fu, M.L.; Devico Marciano, N.; Wright, M.K.; Parsey, D.F.; Liu, S.; Siretskiy, R.E.; Huynh, T.L.; Leutgeb, J.K.; Leutgeb, S. Precisely timed theta oscillations are selectively required during the encoding phase of memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W.; Doppelmayr, M.; Russegger, H.; Pachinger, T. Theta band power in the human scalp EEG and the encoding of new information. Neuroreport 1996, 7, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, F.; Fell, J.; Axmacher, N.; Weber, B.; Lehnertz, K.; Elger, C.E.; Fernández, G. Phase/amplitude reset and theta-gamma interaction in the human medial temporal lobe during a continuous word recognition memory task. Hippocampus 2005, 15, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Денисoва, Е.В.; Пoзняк, Л.А.; Пульцина, К.И.; Третьякoва, В.Д.; Чернышев, Б.В. Анализ мoзгoвoй активнoсти при кoнфигурациoннoм научении с пoмoщью магнитoэнцефалoграфии. Экспериментальная психoлoгия 2025, 18, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, J.W.; Sutherland, R.J. Configural association theory and the hippocampal formation: An appraisal and reconfiguration. Hippocampus 1995, 5, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Чернышев, Б.В.; Ушакoв, В.Л.; Пoзняк, Л.А. Пoиск нейрoфизиoлoгических механизмoв кoнфигурациoннoгo oбучения. Ж. высш. нервн. деят. им. И.П. Павлoва 2024, 74, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.J.; Rudy, J.W. Configural association theory: The role of the hippocampal formation in learning, memory, and amnesia. Psychobiology 1989, 17, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, J.W.; Huff, N.C.; Matus-Amat, P. Understanding contextual fear conditioning: Insights from a two-process model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2004, 28, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeuchl, C.; Meyer, P.; Hoppstädter, M.; Diener, C.; Flor, H. Contextual fear conditioning in humans using feature-identical contexts. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2015, 121, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, K.; Doll, B.B.; Daw, N.D.; Shohamy, D. More Than the Sum of Its Parts: A Role for the Hippocampus in Configural Reinforcement Learning. Neuron 2018, 98, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Ludowig, E.; Rosburg, T.; Axmacher, N.; Elger, C.E. Phase-locking within human mediotemporal lobe predicts memory formation. Neuroimage 2008, 43, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J.F.; Cohen, M.X.; Allen, J.J. Prelude to and resolution of an error: EEG phase synchrony reveals cognitive control dynamics during action monitoring. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canolty, R.T.; Knight, R.T. The functional role of cross-frequency coupling. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.; George, N.; Lachaux, J.P.; Martinerie, J.; Renault, B.; Varela, F.J. Perception’s shadow: Long-distance synchronization of human brain activity. Nature 1999, 397, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, J.M.; Rubchinsky, L.L.; Sigvardt, K.A. Statistical method for detection of phase-locking episodes in neural oscillations. J. Neurophysiol. 2004, 91, 1883–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, P.; Engel, A.K.; Singer, W. Integrator or coincidence detector? The role of the cortical neuron revisited. Trends Neurosci. 1996, 19, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azouz, R.; Gray, C.M. Dynamic spike threshold reveals a mechanism for synaptic coincidence detection in cortical neurons in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8110–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miltner, W.H.R.; Braun, C.; Arnold, M.; Witte, H.; Taub, E. Coherence of gamma-band EEG activity as a basis for associative learning. Nature 1999, 397, 434–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, S.; Rappelsberger, P. Long-range EEG synchronization during word encoding correlates with successful memory performance. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 2000, 9, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, C.; Mangels, J.A. Functional coupling between frontal and parietal lobes during recognition memory. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchenane, K.; Peyrache, A.; Khamassi, M.; Tierney, P.L.; Gioanni, Y.; Battaglia, F.P.; Wiener, S.I. Coherent theta oscillations and reorganization of spike timing in the hippocampal-prefrontal network upon learning. Neuron 2010, 66, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axmacher, N.; Mormann, F.; Fernández, G.; Elger, C.E.; Fell, J. Memory formation by neuronal synchronization. Brain Res. Rev. 2006, 52, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutras, M.J.; Buffalo, E.A. Synchronous neural activity and memory formation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahana, M.J. Associative retrieval processes in free recall. Mem. Cogn. 1996, 24, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herweg, N.A.; Solomon, E.A.; Kahana, M.J. Theta Oscillations in Human Memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallock, H.L.; Wang, A.; Griffin, A.L. Ventral Midline Thalamus Is Critical for Hippocampal-Prefrontal Synchrony and Spatial Working Memory. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 8372–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A.L. The nucleus reuniens orchestrates prefrontal-hippocampal synchrony during spatial working memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, M.C.; Shin, J.D.; Jadhav, S.P. Coherent Coding of Spatial Position Mediated by Theta Oscillations in the Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 4550–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, M.C.; Tang, W.; Jadhav, S.P. The role of replay and theta sequences in mediating hippocampal-prefrontal interactions for memory and cognition. Hippocampus 2020, 30, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palva, J.M.; Palva, S.; Kaila, K. Phase synchrony among neuronal oscillations in the human cortex. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 3962–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, E.M.; Glennon, M.; Prendergast, K.; Sauseng, P. Theta-phase synchronization during memory matching in visual working memory. Neuroimage 2010, 52, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palva, J.M.; Palva, S. Functional integration across oscillation frequencies by cross-frequency phase synchronization. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 48, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer-Teixeira, R.; Belchior, H.; Caixeta, F.V.; Souza, B.C.; Ribeiro, S.; Tort, A.B. Theta phase modulates multiple layer-specific oscillations in the CA1 region. Cereb. Cortex 2012, 22, 2404–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tass, P.; Rosenblum, M.G.; Weule, J.; Kurths, J.; Pikovsky, A.; Volkmann, J.; Schnitzler, A.; Freund, H.-J. Detection of n:m phase locking from noisy data: Application to magnetoencephalography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Wong, K.W.; Shuai, J.W. n:m phase synchronization with mutual coupling phase signals. Chaos 2002, 12, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belluscio, M.A.; Mizuseki, K.; Schmidt, R.; Kempter, R.; Buzsáki, G. Cross-frequency phase-phase coupling between θ and γ oscillations in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisman, J.E.; Jensen, O. The theta-gamma neural code. Neuron 2013, 77, 1002–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Zhang, T. Alteration of phase-phase coupling between theta and g rhythms in a depression-model of rats. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2013, 7, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T. Effects of hydrogen sulfide on modulation of theta-g coupling in hippocampus in vascular dementia rats. Brain Topogr. 2015, 28, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Bieri, K.W.; Hsiao, Y.T.; Colgin, L.L. Spatial sequence coding differs during slow and fast g rhythms in the hippocampus. Neuron 2016, 89, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, J.E.; Idiart, M.A. Storage of 7 +/- 2 short-term memories in oscillatory subcycles. Science 1995, 267, 1512–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Axmacher, N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauseng, P.; Klimesch, W.; Heise, K.F.; Gruber, W.R.; Holz, E.; Karim, A.A.; Glennon, M.; Gerloff, C.; Birbaumer, N.; Hummel, F.C. Brain oscillatory substrates of visual short-term memory capacity. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1846–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W.; Kempter, R.; van Hemmen, J.L.; Wagner, H. A neuronal learning rule for sub-millisecond temporal coding. Nature 1996, 383, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markram, H.; LüBke, J.; Frotscher, M.; Sakmann, B. Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science 1997, 275, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Klaver, P.; Lehnertz, K.; Grunwald, T.; Schaller, C.; Elger, C.E.; Fernández, G. Human memory formation is accompanied by rhinal-hippocampal coupling and decoupling. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axmacher, N.; Schmitz, D.P.; Wagner, T.; Elger, C.E.; Fell, J. Interactions between medial temporal lobe, prefrontal cortex, and inferior temporal regions during visual working memory: A combined intracranial EEG and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 7304–7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, J.F.; Zaghloul, K.A.; Jacobs, J.; Williams, R.B.; Sperling, M.R.; Sharan, A.D.; Kahana, M.J. Synchronous and asynchronous theta and gamma activity during episodic memory formation. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tort, A.B.L.; Komorowski, R.W.; Manns, J.R.; Kopell, N.J.; Eichenbaum, H. Theta-gamma coupling increases during the learning of item-context associations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20942–20947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiske, A.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Conde-Ocazionez, S.A.; Feitosa, A.; Köhler, C.A.; Bevilaqua, L.R.; Cammarota, M. Prior learning of relevant nonaversive information is a boundary condition for avoidance memory reconsolidation in the rat. Hippocampus 2017, 37, 9675–9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragel, J.E.; Van Haerents, S.; Templer, J.W.; Schuele, S.; Rosenow, J.M.; Nilakantan, A.S.; Bridge, D.J. Hippocampal theta coordinates memory processing during visual exploration. eLife 2020, 9, e52108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhühner, F.; Wang, S.H.; Palva, J.M.; Palva, S. Cross-frequency synchronization connects networks of fast and slow oscillations during visual working memory maintenance. eLife 2016, 5, e13451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).