I. Introduction: The Ubiquity of Cycles

"Everything flows, nothing stands still." — Heraclitus

1.1. The Cyclic Nature of Reality

At every scale of observation, from the quantum realm to the cosmos, reality reveals itself through oscillation and periodicity. Electrons orbit atomic nuclei. Molecules vibrate. Neurons fire rhythmically. Hearts beat. Organisms breathe. Day follows night. Seasons cycle. Stars are born and die. Galaxies rotate. The universe itself may oscillate through cycles of expansion and contraction.

This pervasive cyclicity is not coincidental. As this paper will demonstrate, oscillation represents a fundamental mode of existence—perhaps the fundamental mode. The ancient hermetic principle "as above, so below" finds unexpected validation in modern physics and neuroscience: the same mathematical principles governing quantum oscillations also govern brain rhythms, biological cycles, and cosmic periodicities (Klimesch, 2018; Hunt & Schooler, 2019).

Yet despite this ubiquity, cycles have often been treated as separate phenomena requiring distinct explanations at each scale. Quantum mechanics explains subatomic oscillations. Molecular biology explains cellular rhythms. Neuroscience explains brain waves. Chronobiology explains circadian rhythms. Astronomy explains planetary and stellar cycles. Each discipline operates largely in isolation, missing the deep connections that unite oscillatory processes across all scales.

1.2. Why Cycles Matter for Understanding Consciousness

General Resonance Theory (GRT) offers a unified framework for understanding how oscillations at different scales interact to produce consciousness and complex organization (Hunt & Schooler, 2019; Hunt, 2020). GRT’s core insight is deceptively simple yet profoundly explanatory: consciousness emerges from resonant interactions among oscillatory systems, enabling micro-conscious entities to combine into macro-conscious wholes through shared electromagnetic field dynamics.

This resonance-based approach solves one of philosophy’s most vexing problems—the combination problem. How do simpler forms of experience combine to create more complex unified consciousness? Traditional theories struggle because they lack a mechanism for combination that preserves both unity and diversity. GRT proposes that shared resonance—synchronization of oscillatory patterns—provides this mechanism (Hunt & Schooler, 2019).

When physical structures achieve shared resonance at specific frequencies, they undergo what amounts to a phase transition in information exchange capabilities. The boundaries between separate oscillating systems become permeable to information transfer at near light-speed, enabling the emergence of higher-level conscious entities without extinguishing lower-level consciousness. This aligns with Whitehead’s (1929) elegant formulation: "the many become one and are increased by one."

The empirical evidence for this framework continues to accumulate. Klimesch (2018) demonstrated that brain and body oscillations organize into a precise binary hierarchy with 1:2 frequency relationships spanning from ultra-slow BOLD oscillations (0.0098 Hz) through gamma rhythms (40+ Hz). Rodriguez-Larios et al. (2020) showed that cognitive demand enhances transient 2:1 harmonic coupling between alpha and theta bands. Young et al. (2022) revealed that brain-body harmonic locking is modulated by task demands, with delta rhythms coordinating both cardiovascular rhythms and higher-frequency EEG during cognitive tasks.

1.3. Morowitz’s Theorem and the Necessity of Cycles

The prevalence of cycles in nature is not merely a curious observation—it is a thermodynamic necessity. Morowitz (1968) proved a fundamental theorem: in any open system at steady state, with energy flowing from a source to a sink, at least one cycle must exist. The proof is elegant: if energy flows through a system that can store energy, then the system must transition between states. At steady state, forward transitions must balance backward transitions overall, but they cannot balance in detail for all pairs of states (or such detailed balance would prevent net energy absorption). Therefore, the system must traverse cyclic paths—leaving some states by one route and returning by another.

This theorem has profound implications. It means that life—which requires steady energy flow and energy storage—must be organized cyclically. From the Krebs cycle in metabolism to circadian rhythms, from neuronal oscillations to ecological cycles, the cyclical organization of living systems is not optional but mandatory (Ho, 1995). As Ho (1995) eloquently argues, cycles have zero net entropy production, making them the ideal substrate for non-dissipative processes subject to Onsager’s reciprocity relationships and coherent coupling.

Moreover, symmetrically coupled cycles enable energy delocalization across an entire system while permitting localization to any point—explaining how organisms achieve "energy at will, whenever and wherever required" (Ho, 1995, p. 7). This principle extends beyond metabolism to consciousness itself: the ability to direct attention, to move different body parts independently yet in coordination, to think and feel simultaneously—all depend on coherent coupling of nested cycles.

1.4. The Scope of This Paper

This paper presents a comprehensive mapping of cycles from quantum to cosmic scales, organized according to GRT’s theoretical framework. I examine:

The mathematics of nested cycles and how binary octave relationships create stable resonance hierarchies

Quantum and subatomic oscillations as the foundational substrate

Cellular and molecular cycles that organize biological function

Neural oscillations that constitute the "theta theater" of consciousness

Body rhythms and the slowest shared resonance principle

Longer biological cycles from circadian to developmental

Geological and cosmological cycles at the largest scales

Cross-scale coupling and the emergence of nested consciousness

Pathologies that arise when cyclical organization breaks down

Implications for physics, biology, neuroscience, technology, and philosophy

Our central thesis is that "cycles upon cycles"—oscillations nested within oscillations at every scale—represents the fundamental organizing principle of reality. Consciousness is not separate from this organization but rather its highest expression: the intrinsic experience of resonant field dynamics as they achieve sufficient complexity and integration.

II. The Mathematics of Nested Cycles

2.1. Binary Octave Relationships

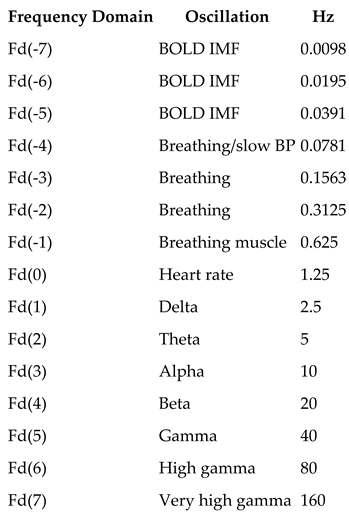

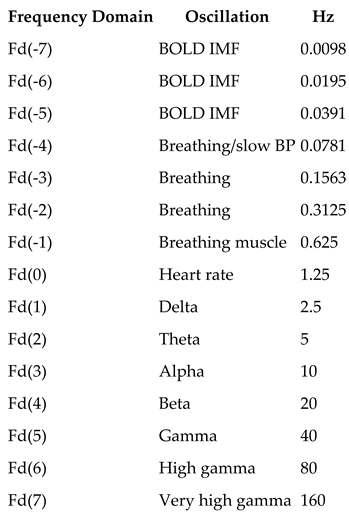

The most stable resonance relationships are those involving simple integer ratios. Among these, binary relationships (2:1 ratios) appear to be nature’s preferred architecture. Klimesch (2018) empirically demonstrated that brain and body oscillations organize into a precise binary hierarchy, with each frequency domain related to its neighbors by factors of two.

This preference for binary relationships is not arbitrary. In wave dynamics, frequencies related by powers of two create particularly stable interference patterns. When two oscillations differ by a factor of two, every cycle of the slower frequency corresponds to exactly two cycles of the faster frequency, creating perfect phase alignment at regular intervals. This mathematical property makes binary relationships information-rich and energetically efficient (Hunt, in progress).

The binary octave structure spans an extraordinary range. Klimesch (2018) identified at least 12 distinct frequency domains in brain-body systems:

Each frequency domain maintains a precise 1:2 relationship with its neighbors, creating what Klimesch describes as "a single frequency architecture organized by harmonic ratios" (Klimesch, 2018, p. 8).

2.2. The Boundary Equation: x = v/f

GRT’s Boundary Conjecture provides a quantitative framework for understanding conscious boundaries through the fundamental relationship:

where x represents the spatial extent of a conscious entity, v denotes the propagation velocity of resonant signals, and f represents the oscillation frequency (Hunt, 2020). This deceptively simple equation has profound implications.

Consider electromagnetic field propagation in neural tissue, which occurs at approximately 47 km/s (Ruffini et al., 2020)—about 5,000 times faster than typical neural spike propagation. At a theta frequency of 5 Hz, this yields:

This enormous distance—nearly 10 kilometers—far exceeds brain dimensions, suggesting that theta rhythms are more than adequate for integrating activity across the entire brain. Higher frequencies create smaller integration scales: gamma oscillations at 40 Hz yield boundaries of about 1,175 meters, still spanning the whole brain. Only at very high gamma frequencies (160 Hz) do we approach scales (~294 meters) that begin to constrain whole-brain integration, though even these encompass large neural populations.

This mathematics reveals why theta (4-8 Hz) serves as consciousness’s primary organizing rhythm: it’s the slowest frequency that still provides sufficient temporal resolution (4-8 discrete processing cycles per second) for seamless conscious experience while enabling integration across the brain’s distributed networks (Hunt, 2020).

2.3. Resonance and Phase Locking

Resonance occurs when oscillating systems influence each other’s dynamics through coupling. The strength of this influence depends on their frequency relationship and coupling mechanism. Phase locking—where oscillators maintain a constant phase relationship—represents the strongest form of resonance and underlies consciousness according to GRT.

Cross-frequency coupling (CFC) allows oscillations at different frequencies to coordinate. The most important forms are:

Phase-amplitude coupling (PAC): The phase of a slower oscillation modulates the amplitude of a faster oscillation. For example, gamma amplitude is often modulated by theta phase, creating nested oscillatory structures (Canolty & Knight, 2010).

Phase-phase coupling (PPC): The phases of two oscillations maintain a fixed relationship, as in harmonic locking where frequencies maintain integer ratios (Rodriguez-Larios et al., 2020).

Amplitude-amplitude coupling (AAC): The amplitudes of two oscillations correlate, indicating synchronized energy dynamics.

The oscillatory hierarchy hypothesis (Lakatos et al., 2005) proposes that low-frequency rhythms provide temporal scaffolding for higher-frequency oscillations, creating nested computational architecture. Empirical evidence strongly supports this: slower oscillations scaffold faster ones through phase-to-phase coupling, creating a scale-invariant architecture where body rhythms provide the foundation for neural processing (Klimesch, 2018).

2.4. Temporal Quanta and Subjective Duration

Each oscillation cycle at frequency ν defines a temporal interval of duration Δt = 1/ν. This interval represents the characteristic timescale at which that oscillatory process operates (Hunt, in progress). For ultra-slow BOLD oscillations at 0.0098 Hz, each cycle lasts about 102 seconds. For gamma oscillations at 40 Hz, each cycle lasts just 25 milliseconds.

Subjective temporal experience reflects the integration of activity across multiple frequency scales. For a system oscillating simultaneously at multiple binary-related frequencies {ν₁, ν₂, ..., νₙ} where νᵢ₊₁ = 2νᵢ, the pattern of neural activity N(t) can be expressed as:

where Aᵢ represents amplitude at frequency νᵢ and φᵢ represents phase. The weighting factor 1/νᵢ reflects the observation that slower frequencies modulate larger spatial scales and appear to contribute more substantially to the temporal structure of conscious experience.

This mathematical framework reveals how consciousness operates across multiple temporal scales simultaneously. Each frequency domain processes information at its characteristic timescale, and the nested integration of these scales—from millisecond gamma processing to multi-second BOLD fluctuations—creates the rich temporal texture of conscious experience.

III. Quantum and Subatomic Cycles (10¹² - 10²⁴ Hz)

3.1. The Quantum Ocean

At the foundation of physical reality lies what might be called the "quantum ocean"—a continuous field of oscillating vacuum energy from which all observed phenomena emerge. Quantum field theory reveals that even "empty" space teems with virtual particles popping in and out of existence, zero-point energy fluctuations, and electromagnetic field oscillations (Hunt, in progress).

These quantum oscillations occur at extraordinarily high frequencies. The Compton frequency of an electron—the frequency associated with its rest mass—is approximately 1.24 × 10²⁰ Hz. The Planck frequency, which may represent the fundamental temporal grain of reality, is about 1.85 × 10⁴³ Hz. At these scales, individual oscillation cycles last between 10⁻²⁰ and 10⁻⁴³ seconds—far below direct observability yet fundamental to physical existence.

Particle-wave duality reveals that all matter exhibits oscillatory behavior. An electron’s de Broglie wavelength determines its wave nature; its position probability distribution oscillates; its quantum state evolves according to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, which describes how quantum wavefunctions oscillate through time.

3.2. Quantum Coherence and Consciousness

Hameroff and Penrose (2014) proposed that consciousness might depend on quantum coherence in neuronal microtubules—protein structures that oscillate at frequencies between 10¹² and 10¹⁵ Hz. While controversial, this Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR) theory aligns with GRT’s emphasis on multi-scale resonance. If quantum coherence does play a role in consciousness, it would represent the finest-grained level in consciousness’s nested hierarchy.

Recent evidence suggests quantum effects may be more prevalent in biological systems than previously thought. Photosynthesis exploits quantum coherence for energy transfer. Avian magnetoreception may depend on quantum entanglement in cryptochrome proteins. The olfactory system may use quantum tunneling to discriminate molecular vibrations. While these examples don't directly implicate quantum processes in consciousness, they demonstrate that biological systems can maintain quantum coherence at physiological temperatures—opening the door for quantum contributions to neural processing (Craddock et al., 2017).

From GRT’s perspective, quantum oscillations provide the foundational substrate for bioelectric integration. Even if consciousness doesn't directly depend on quantum coherence, the nested hierarchy of oscillations that constitutes consciousness ultimately rests on quantum-scale dynamics.

3.3. Atomic and Molecular Vibrations

Moving up in scale, atomic and molecular oscillations bridge quantum and classical regimes. Electrons transition between orbital states by absorbing or emitting photons at precise frequencies. Molecular bonds vibrate at characteristic frequencies—stretching, bending, and twisting in complex patterns. These molecular vibrations create the infrared absorption spectra that identify chemical compounds and may play roles in olfaction and other sensory processes.

Chemical reactions can be understood as transitions between different vibrational states. Catalysts work by altering molecular vibration patterns to lower activation energy barriers. Enzymes achieve extraordinary reaction rate enhancements partly by creating oscillatory environments that guide reactants through optimal vibrational trajectories.

In this view, chemistry itself becomes a study of molecular resonance—how molecules' vibrational patterns interact, couple, and transform into new patterns. The transition from lifeless chemistry to living biochemistry involves the emergence of sustained, coupled oscillatory cycles: the essence of metabolism.

IV. Cellular and Molecular Cycles (10⁻⁶ - 10⁹ Hz)

4.1. Bioelectric Patterns and Morphogenesis

Michael Levin and colleagues have revolutionized our understanding of development by demonstrating that bioelectric patterns—voltage gradients across cell membranes and between tissues—encode morphogenic information that guides the formation of complex anatomical structures (Levin, 2021). These bioelectric patterns oscillate at frequencies between 10⁶ and 10⁹ Hz, creating what might be called a "bioelectric code" that complements the genetic code.

Gap junctions allow bioelectric signals to propagate between cells, creating tissue-level field patterns that coordinate development. Manipulating these patterns can produce remarkable effects: inducing planarian worms to regenerate heads with different species-typical anatomies, causing cells to form complete eyes in non-eye locations, or triggering cancer cells to normalize their behavior.

From GRT’s perspective, these bioelectric patterns represent an ancient evolutionary solution to the problem of multi-cellular coordination. Long before nervous systems evolved, primitive organisms used bioelectric fields to integrate information across distributed cellular populations. The electromagnetic field computation that underlies consciousness in complex brains is the descendant of these primordial bioelectric coordination mechanisms (Hunt & Schooler, 2019).

4.2. Cellular Metabolic Cycles

Metabolism is fundamentally cyclic. The Krebs cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle) sits at the heart of cellular respiration, its eight-step sequence of reactions generating energy-rich molecules while recycling intermediates. ATP synthesis and hydrolysis create continuous cycles of energy storage and release. Glycolysis oscillates with remarkable precision—in yeast, glycolytic intermediates oscillate with periods of several minutes, creating metabolic rhythms visible as synchronized oscillations across entire cell populations (Richard et al., 1996).

Calcium signaling exhibits complex oscillatory dynamics. Cytoplasmic calcium concentrations oscillate at various frequencies (0.01-10 Hz), encoding information through both amplitude and frequency modulation. Different oscillation patterns trigger different cellular responses—a beautiful example of frequency coding in biological systems. Calcium waves propagate through cells and tissues, coordinating cellular activities across large distances (Berridge, 2009).

Redox cycles involving NAD+/NADH and other electron carriers create oscillations in cellular reduction-oxidation state. These cycles couple to energy metabolism and regulate processes from gene expression to cellular lifespan.

Protein homeostasis involves continuous cycles of synthesis and degradation. The ubiquitin-proteasome system marks proteins for destruction, creating rhythmic turnover. Protein folding cycles in the endoplasmic reticulum involve chaperone proteins that assist folding through repeated binding and release. Autophagy—cellular self-digestion of damaged components—occurs cyclically, with periods of autophagosome formation alternating with lysosomal degradation.

Neurotransmitter cycles at synapses demonstrate elegant oscillatory organization. Synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitters fuse with the presynaptic membrane during release, then are recycled through endocytosis, refilled with neurotransmitter, and returned to the readily releasable pool. This vesicle cycle takes seconds to minutes. Released neurotransmitters are rapidly cleared from synaptic clefts by reuptake transporters or enzymatic degradation, maintaining the oscillatory capacity for repeated signaling (Südhof, 2004).

These metabolic cycles are not independent—they form an integrated network where perturbations propagate through coupling relationships. Morowitz’s (1968) theorem explains why: open systems maintaining steady states through energy flow must be cyclically organized. Life’s metabolic architecture reflects thermodynamic necessity rather than arbitrary biochemical accident.

4.3. The Cell Cycle and Gene Expression Rhythms

The cell cycle—the sequence of growth phases (G1, S, G2) and mitosis (M)—represents a fundamental biological oscillation. Cell cycle duration varies from tens of minutes in early embryos to 24 hours or more in adult tissues, with precise checkpoint controls ensuring accurate DNA replication and division.

Gene expression itself exhibits rhythmic patterns. Transcription factors oscillate in concentration, creating pulses of gene expression. The circadian clock operates through transcription-translation feedback loops where clock proteins inhibit expression of their own genes with 24-hour periodicity. Even in cells without circadian clocks, many genes show rhythmic expression patterns coordinated with metabolic and cell cycle phases (Takahashi, 2017).

Chromatin—the DNA-protein complex—undergoes dynamic remodeling cycles as genes activate and silence. Histone modifications oscillate, creating waves of chromatin accessibility that coordinate cell-wide gene expression programs. These epigenetic oscillations may constitute a form of cellular memory, storing information about developmental history in cyclic patterns of modification.

V. Neural Oscillations and Brain Rhythms (0.01 - 1000 Hz)

5.1. The Hierarchy of Neural Frequencies

Brain activity exhibits oscillations across an extraordinary frequency range, from ultra-slow infraslow oscillations (~0.01 Hz) to very high gamma (~200 Hz). These are not independent rhythms but form an integrated hierarchy where slower oscillations scaffold faster ones through cross-frequency coupling (Klimesch, 2018; Young et al., 2022).

The classical EEG bands have been recognized for nearly a century:

Delta (0.5-4 Hz): Associated with sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep. Also implicated in attention, salience detection, and motivation.

Theta (4-8 Hz): Prominent during memory encoding, spatial navigation, and certain meditative states. Critical for consciousness according to GRT.

Alpha (8-13 Hz): Dominant during relaxed wakefulness with eyes closed. May reflect cortical inhibition or active processing in task-irrelevant areas.

Beta (13-30 Hz): Associated with active thinking, focus, and motor preparation. Excessive beta is implicated in anxiety and Parkinson’s disease.

Gamma (30-100 Hz): Linked to local cortical processing, attention, and perceptual binding. Often nested within theta cycles.

However, Klimesch’s (2018) comprehensive analysis reveals this classification is incomplete. His binary hierarchy extends from ultra-slow BOLD oscillations at 0.0098 Hz through breathing and heart rate into traditional EEG bands and up to very high gamma at 160 Hz—at least 15 distinct frequency domains, each precisely double the previous one.

5.2. Theta as the "Organizing Wave" of Consciousness

Theta oscillations (4-8 Hz) occupy a privileged position in GRT’s framework. Multiple lines of evidence suggest theta serves as consciousness’s primary temporal organizing rhythm:

Spatial integration capability: At 47 km/s field propagation velocity, theta frequencies enable integration across the entire brain. The boundary equation yields x = 47,000 m/s ÷ 5 Hz = 9,400 m—far exceeding brain dimensions.

Temporal resolution: Theta provides 4-8 discrete processing cycles per second—sufficient for seamless conscious experience without excessive metabolic cost. This is the "temporal quanta" of conscious perception (Hunt, 2020).

Hippocampal role: The hippocampus generates prominent theta rhythms during active exploration and memory encoding. Hippocampal-cortical theta coupling appears essential for integrating new experiences into ongoing consciousness (Hasselmo, 2005).

Sleep-wake transitions: Loss of theta marks the transition from waking consciousness to delta-dominated deep sleep. Theta reappears during REM sleep when consciousness (in the form of dreaming) returns (Buzsáki, 2002).

Cross-frequency scaffolding: Theta provides the temporal structure within which faster gamma oscillations nest, creating a hierarchical architecture where theta cycles act as "computational units" and gamma provides processing within those units (Lisman & Jensen, 2013).

The theta-delta boundary (~4 Hz) represents a fundamental threshold for consciousness. Above this frequency, the brain can maintain sufficient integration for conscious experience. Below it, the temporal resolution becomes inadequate for the rapid information processing consciousness requires. This explains why consciousness fades as delta rhythms dominate during deep sleep (Hunt, 2020).

5.3. Cycles Within Cycles: Gamma Nesting in Theta

One of the most remarkable discoveries in systems neuroscience is that gamma oscillations are often nested within theta cycles. Lopes-Dos-Santos et al. (2018) developed sophisticated methods to analyze theta-gamma coupling cycle-by-cycle rather than averaged across many cycles. Their findings revolutionized understanding of hippocampal processing:

Only 36% of theta cycles display strong gamma oscillations of a single spectral type

Each theta cycle has a unique profile of gamma features, making it an individual computational unit

Multiple gamma subtypes exist: slow-gamma (~30-50 Hz) linked to CA3 input, mid-gamma (~60-90 Hz) linked to entorhinal input, plus novel beta and additional gamma bands

This cycle-by-cycle variability has profound implications. As Bagur and Benchenane (2018, p. 769) note: "theta cycles can be viewed as individual computational units characterized by typical gamma profiles." Each theta cycle—lasting 125-250 milliseconds—provides a temporal window for specific computations. The mixing and matching of different gamma patterns within successive theta cycles creates enormous computational flexibility.

From GRT’s perspective, this nested architecture exemplifies how consciousness integrates information across multiple temporal scales simultaneously. Theta provides the "temporal backbone"—the basic rhythm organizing conscious experience. Gamma provides the "computational richness"—the detailed processing within each moment. Together, they create the multi-scale temporal integration necessary for unified conscious experience.

5.4. Traveling Waves and Critical Dynamics

Neural oscillations don't merely synchronize locally—they propagate as traveling waves across cortical surfaces. These waves carry information about sensory inputs, motor plans, and cognitive states. The direction, speed, and spatial pattern of traveling waves may encode information beyond what spike rates alone convey (Muller et al., 2018).

Recent work on neural criticality suggests the brain operates near critical phase transitions where small perturbations can propagate across large scales—the boundary between order and chaos. At criticality, the brain exhibits:

Power-law dynamics: Avalanches of neural activity follow power-law size distributions

Scale-free organization: No characteristic scale separates small and large events

Maximal information capacity: The system balances local processing with global integration

Sensitivity to inputs: Small perturbations can have large effects

This critical state may be optimal for consciousness. Too ordered (excessive synchrony) and the system becomes rigid, unable to process new information (as in seizures). Too chaotic (insufficient synchrony) and the system fragments, losing coherent integration. Consciousness may require operation at this critical boundary—which is inherently oscillatory (Tagliazucchi et al., 2012).

VI. Body Rhythms and the Slowest Shared Resonance (10⁻⁴ - 1 Hz)

6.1. The Principle of Slowest Shared Resonance

Young et al. (2022) discovered a remarkable principle: neural systems communicate through progressively slower oscillations as the distance between them increases. They documented:

Gastric-brain resonance: ~0.05 Hz (slow waves from the stomach)

Cardiac-brain resonance: ~0.1 Hz (heart rate variability coupling to brain activity)

Retinal-brain resonance: ~3-4 Hz (linked to saccadic eye movements)

Intracerebral theta: ~4-8 Hz (communication within the brain)

This pattern reflects a fundamental constraint: longer-distance communication requires slower frequencies to maintain phase coherence. High-frequency oscillations accumulate phase differences over distance, losing coherence. Lower frequencies maintain phase alignment across larger spatial scales (Hunt, 2020).

This "slowest shared resonance" principle helps explain theta’s role in consciousness. Theta represents the slowest frequency that enables intracerebral communication while maintaining sufficient temporal resolution for conscious processing. Slower frequencies (delta and below) provide whole-body integration but lack the temporal granularity for detailed cognitive processing.

6.2. Cardiovascular Rhythms

The heart beats approximately 60-100 times per minute in resting humans—roughly 1.25 Hz. This cardiovascular rhythm is far from constant; heart rate variability (HRV) reflects complex interactions between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. HRV exhibits multiple oscillatory components:

High-frequency (~0.15-0.4 Hz): Linked to respiration (respiratory sinus arrhythmia)

Low-frequency (~0.04-0.15 Hz): Related to baroreceptor reflexes and autonomic regulation

Very low frequency (<0.04 Hz): Associated with thermoregulation and hormonal fluctuations

Reduced HRV is a marker of poor health outcomes, suggesting that cardiovascular oscillatory flexibility is essential for organismal resilience. The brain continuously monitors cardiac rhythms—heartbeat-evoked potentials appear in EEG recordings, and cardiac rhythms modulate perceptual thresholds and emotional processing.

Young et al.’s (2022) work reveals that cognitive demand enhances brain-heart coupling, particularly in the delta band. During mental arithmetic, delta rhythms synchronize to cardiovascular oscillations while simultaneously coupling to higher-frequency EEG bands. This suggests delta acts as a coordination hub, linking body rhythms to cognitive processing—a beautiful example of nested consciousness where bodily states influence and constitute conscious experience.

6.3. Respiratory Rhythms

Breathing occurs at approximately 12-20 times per minute (0.2-0.33 Hz) in resting adult humans. Like heart rate, respiratory rate is highly variable and influenced by autonomic, metabolic, and cognitive factors. Breathing modulates brain activity across all EEG bands through respiratory sinus arrhythmia and direct mechanosensory signals from chest expansion.

Young et al. (2022) demonstrated that cognitive demand enhances brain-breath coupling across all EEG bands. This universal coupling suggests respiration provides a fundamental temporal scaffolding for neural processing—a rhythm that coordinates activity from the slowest (infraslow oscillations) to the fastest (high gamma) brain dynamics.

The breath’s unique position as a partially voluntary physiological rhythm makes it a bridge between conscious control and autonomic function. Meditation practices across cultures have recognized this, using breath awareness and manipulation as tools for altering consciousness. From GRT’s perspective, this makes perfect sense: modulating breath rhythm influences the nested oscillatory hierarchy, thereby modulating conscious states.

6.4. Gastric Rhythms

The stomach generates slow waves at approximately 0.05 Hz (~3 cycles per minute)—even slower than breathing. These gastric oscillations propagate through stomach smooth muscle, coordinating peristaltic contractions for digestion. Surprisingly, gastric rhythms couple to brain activity, particularly in the insula and other regions involved in interoception (Richter et al., 2017).

Disrupted gastric-brain coupling is implicated in nausea, functional dyspepsia, and other disorders. More speculatively, the ancient "gut feeling" may have neurophysiological reality: gastric rhythms influence brain states and thereby emotional and cognitive processing. The gut-brain axis operates not just through hormones and neural pathways but through direct rhythmic coupling.

The 0.05 Hz gastric rhythm represents the slowest shared resonance in Young et al.’s (2022) hierarchy—the foundation of the body’s oscillatory architecture. All faster body and brain rhythms are scaffolded by this ultra-slow cycle, creating a nested temporal structure spanning four orders of magnitude in frequency (from 0.05 Hz to >100 Hz).

VII. Circadian and Longer Cycles (Hours to Years)

7.1. Circadian Rhythms: The 24-Hour Cycle

Perhaps no biological cycle is more fundamental than the circadian rhythm—the approximately 24-hour oscillation in physiology and behavior synchronized to Earth’s light-dark cycle. First observed in plant leaf movements by Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan in 1729, circadian rhythms have since been found in virtually all organisms from cyanobacteria to humans.

The mammalian circadian system centers on the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus—a "master clock" that synchronizes peripheral clocks throughout the body. At the molecular level, circadian rhythms arise from transcription-translation feedback loops involving clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY) that inhibit their own expression with ~24-hour periodicity (Takahashi, 2017).

But the circadian system is not a simple oscillator. It comprises:

The SCN master clock: ~20,000 neurons that couple through electrical and chemical signals to maintain coherent oscillation

Peripheral clocks: Present in virtually every cell, oscillating semi-independently

Tissue-specific rhythms: Liver metabolism, immune cell activity, hormone secretion—all show circadian patterns

Light exposure resets the clock through specialized retinal ganglion cells containing melanopsin. This entrainment mechanism allows organisms to synchronize to external day-night cycles while maintaining intrinsic rhythms when environmental cues are absent.

Disrupted circadian rhythms are implicated in numerous health problems: sleep disorders, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and psychiatric conditions. Shift work and jet lag demonstrate the consequences of desynchronizing internal clocks from environmental cycles. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense: the circadian system evolved over billions of years to coordinate physiology with Earth’s rotation—violating this coordination produces physiological stress.

7.2. Sleep-Wake Cycles and Ultradian Rhythms

Sleep is not a single state but a complex cycle of stages. Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep progresses through stages N1, N2, and N3 (slow-wave sleep) characterized by increasing delta dominance. REM sleep features rapid eye movements, muscle atonia, and dream consciousness. These stages cycle with approximately 90-minute periodicity—an ultradian rhythm nested within the circadian rhythm.

The transition from waking to sleep involves a dramatic shift in oscillatory organization. Waking consciousness is dominated by theta and alpha rhythms with nested gamma. As sleep deepens, delta rhythms (0.5-4 Hz) gradually take over. In deep NREM sleep, high-amplitude slow oscillations (~0.8 Hz) coordinate cortical activity into synchronized UP and DOWN states (Steriade, 2006).

This shift from theta to delta reflects changing computational priorities. During waking, the brain prioritizes sensory integration and cognitive processing—functions requiring the rapid information exchange enabled by theta frequencies. During deep sleep, priorities shift to memory consolidation, synaptic downscaling, and metabolic restoration—functions that benefit from the coordinated slow oscillations of delta (Tononi & Cirelli, 2014).

REM sleep represents a fascinating intermediate state. EEG patterns resemble waking—theta rhythms reappear and gamma nesting returns—yet the person remains asleep and disconnected from sensory input. Dreams during REM exhibit the phenomenal richness of waking consciousness, consistent with the restoration of theta-gamma coupling. Non-REM dreams are typically less vivid, corresponding to delta dominance.

Beyond the 90-minute sleep cycle, other ultradian rhythms organize behavior: the basic rest-activity cycle (BRAC) describes alternating periods of optimal performance and fatigue throughout waking; feeding rhythms; hormonal pulses. These ultradian rhythms interact with circadian rhythms to create complex temporal organization across multiple scales.

7.3. Longer Cycles: Seasonal, Developmental, and Lifespan

Many organisms exhibit seasonal cycles entrained to annual photoperiod changes. These include:

Reproductive cycles: Breeding seasons timed to maximize offspring survival. Many mammals show estrous cycles—periods of sexual receptivity—that vary from 4 days (rats) to several months (elephants). Some species are seasonally polyestrous (cycling only during breeding season) while others cycle year-round.

Hibernation and torpor: Metabolic suppression during resource-scarce winters. Body temperature, heart rate, and breathing slow dramatically. Some species (ground squirrels) hibernate for 7-8 months annually.

Migration: Annual movements between summer and winter ranges. Arctic terns migrate ~70,000 km annually—the longest migration on Earth.

Immune function: Seasonal variation in disease susceptibility. Many infections show winter peaks related to photoperiod-driven immune suppression (Nelson et al., 2002).

Molt cycles: Periodic replacement of fur, feathers, or exoskeleton. Birds may molt once or twice yearly; mammals often show seasonal coat changes.

In humans, seasonal affective disorder (SAD) demonstrates continued influence of photoperiod on mood and behavior despite modern lighting. Vitamin D synthesis, immune function, and mood all show seasonal oscillations. The ~28-day menstrual cycle in women represents another endogenous periodicity. While claims of lunar synchronization remain controversial, some evidence suggests subtle lunar influences on human reproduction and behavior (Cajochen et al., 2013).

Tidal and lunar rhythms profoundly affect marine and coastal life. Many organisms synchronize spawning to tidal cycles, spring tides, or specific lunar phases. Grunions (fish) spawn precisely on beaches during spring high tides following new and full moons. Coral reefs exhibit mass spawning events synchronized to lunar cycles. Even terrestrial organisms may exhibit lunar rhythms—some studies report lunar periodicity in human menstruation, though meta-analyses remain inconclusive.

Ecological cycles operate at population and community scales:

Predator-prey cycles: The classic Lotka-Volterra dynamics predict oscillating predator and prey populations. Canadian lynx and snowshoe hare populations exhibit remarkable ~10-year cycles documented through centuries of fur trading records (Elton & Nicholson, 1942).

Nutrient cycles: Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycle through ecosystems with varying periodicities—from daily photosynthesis-respiration cycles to millennium-scale geological cycles.

Succession patterns: Following disturbance, ecosystems progress through predictable successional stages over years to centuries before reaching climax communities.

Forest fire cycles: Many ecosystems exhibit characteristic fire return intervals from years (grasslands) to centuries (old-growth forests).

Developmental cycles occur across even longer timescales. Embryonic development follows precisely timed sequences of cell differentiation, tissue formation, and organogenesis. Childhood development shows distinct stages (infancy, early childhood, adolescence) marked by qualitative changes in physical, cognitive, and emotional capacities.

The entire lifespan might be viewed as a very slow cycle: birth, growth, maturity, decline, and death. From a process philosophy perspective compatible with GRT, death is not an end but a transformation—the cessation of one level of organized oscillation and the return of constituents to simpler oscillatory regimes. The matter that composed a living organism persists in new forms, continuing its participation in reality’s fundamental oscillatory dynamics.

VIII. Geological and Cosmological Cycles (Years to Billions of Years)

8.1. Planetary Cycles and Earth’s Orbital Rhythms

Earth’s rotation creates the 24-hour day-night cycle that has profoundly shaped biology. But this rotation is gradually slowing due to tidal friction—days were shorter in the past and will lengthen in the future. Evidence from fossil growth rings suggests Devonian days (~400 million years ago) lasted about 22 hours. Tidal cycles themselves—the twice-daily rise and fall of ocean levels driven by Moon and Sun—create additional periodicities that structure life in intertidal zones.

Earth’s 365.25-day orbit around the Sun creates seasonal cycles at temperate latitudes. But the parameters of Earth’s orbit are not constant—they vary rhythmically over vast timescales, creating the Milankovitch cycles that have profoundly influenced climate and biological evolution.

The Milankovitch Cycles: These orbital variations, named after Serbian mathematician Milutin Milanković, combine to produce complex climate periodicities:

Eccentricity (100,000 and 400,000-year cycles): Earth’s orbit varies from nearly circular to mildly elliptical. When eccentricity is high, seasonal contrasts become more extreme in one hemisphere. Two eccentricity cycles exist—a dominant 100,000-year cycle and a longer 400,000-year cycle.

Obliquity/Axial Tilt (41,000-year cycle): Earth’s axial tilt varies between 22.1° and 24.5°. Greater tilt produces more extreme seasons; lesser tilt produces milder seasons. This cycle strongly influences ice sheet growth and retreat.

Precession (19,000 and 23,000-year cycles): Earth’s axis precesses like a wobbling top, completing a full cycle every ~26,000 years. This shifts which hemisphere receives more solar radiation during different seasons. Two precession components exist due to the Moon’s influence and the elliptical orbit’s rotation.

These cycles combine to create complex patterns. Their phase relationships determine whether effects amplify or cancel. The dominant ~100,000-year glacial-interglacial cycle of the past million years arises primarily from eccentricity modulation of precession effects, though the exact mechanisms remain debated (Huybers, 2011).

Milankovitch cycles have profoundly shaped human evolution. African climate oscillations between wet and dry periods—driven partly by precession—may have driven hominin evolution through habitat fragmentation and reconnection. The emergence of Homo sapiens (~300,000 years ago) and major human migrations out of Africa coincided with specific orbital configurations that created windows of opportunity.

Beyond Earth, other planets exhibit orbital cycles. Mars’s obliquity varies chaotically between 15° and 35° over millions of years, producing dramatic climate shifts. Jupiter’s moons experience tidal heating cycles. The Solar System’s planets exhibit long-period orbital resonances spanning millions to billions of years.

The Moon’s orbit gradually recedes from Earth at ~3.8 cm/year due to tidal energy dissipation, meaning lunar and tidal cycles were faster in the past. Analysis of ancient tidal rhythmites—sedimentary rocks recording tidal cycles—reveals that 900 million years ago, the Moon orbited closer and Earth’s day lasted only ~18 hours (Williams, 2000).

8.2. Climate Cycles

Earth’s climate exhibits periodicities across vast timescales:

Glacial-interglacial cycles: ~100,000-year periodicity linked to Milankovitch cycles

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO): 2-7 year cycle involving ocean-atmosphere coupling

Pacific Decadal Oscillation: ~20-30 year pattern of Pacific sea surface temperatures

Solar cycles: ~11-year sunspot cycle and longer-term solar magnetic field variations

These climate oscillations have profoundly influenced biological evolution. Ice ages drove extinctions, migration patterns, and speciation events. Rapid climate shifts associated with deglaciations forced organisms to adapt or perish. Human evolution was shaped by African climate oscillations between wet and dry periods.

Climate cycles demonstrate the principle of cross-scale coupling. ENSO, a relatively fast climate cycle, influences the occurrence of hurricanes, droughts, and floods—affecting ecosystems and human societies. Longer-term climate cycles interact with plate tectonics, volcanic activity, and solar variations in complex feedback systems that make long-term climate prediction challenging.

8.3. Geological Cycles and Geomagnetic Reversals

The Wilson Cycle describes the opening and closing of ocean basins over ~500 million years as continents rift apart and collide. The supercontinent cycle—assembly and breakup of supercontinents like Pangaea, Rodinia, and Columbia—operates on similar timescales. These tectonic cycles profoundly affect climate, sea level, biodiversity, and mineral resource formation.

Mountain building (orogeny) and erosion constitute another geological cycle. Tectonic forces uplift mountains; weathering and erosion wear them down. The sediment eroded from mountains accumulates in ocean basins, eventually being subducted and recycled through plate tectonics. This cycle moves material through the crust, mantle, and surface environment over hundreds of millions of years.

Volcanic activity shows various cycles. Individual volcanoes exhibit periodicities in eruption frequency. Large igneous provinces—massive volcanic events—occur episodically throughout Earth history, sometimes coinciding with mass extinctions. The causes remain debated but may involve mantle plume activity with hundred-million-year quasi-periodicities.

Geomagnetic reversals represent one of Earth’s most dramatic cycles. Earth’s magnetic field periodically reverses polarity, with north and south magnetic poles switching positions. The timing is irregular but averages several reversals per million years. The current field configuration (with magnetic north near geographic north) has persisted for ~780,000 years—longer than average, suggesting a reversal may be overdue.

During reversals, the field weakens substantially, potentially exposing the surface to increased cosmic radiation. Some researchers have linked reversals to extinction events, though evidence remains controversial. The reversal process itself takes 1,000-10,000 years—geologically rapid but slow enough that life can adapt.

Sea level cycles operate at multiple timescales. Tidal cycles (hours), storm surges (days), seasonal variations (months), and glacial-interglacial changes (tens of thousands of years) all contribute to sea level variability. Since the last glacial maximum (~20,000 years ago), sea level has risen ~120 meters as ice sheets melted—profoundly reshaping coastlines and human settlement patterns.

8.4. Stellar Cycles and Oscillations

Stars follow life cycles from birth in nebular clouds through main sequence burning to eventual death as white dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes. The duration depends on stellar mass—massive stars live only millions of years while red dwarfs may shine for trillions.

Solar oscillations demonstrate that even individual stars are not static but pulsate with complex periodicities. The Sun exhibits multiple oscillation modes:

p-modes (pressure waves): ~5-minute oscillations that penetrate throughout the solar interior, providing helioseismology data about internal structure

g-modes (gravity waves): Longer period oscillations (~hours) in the solar core

Sunspot cycle: ~11-year periodicity in solar magnetic activity, with solar minimum and maximum affecting space weather and Earth’s upper atmosphere

Hale cycle: ~22-year full magnetic polarity cycle (two sunspot cycles)

Gleissberg cycle: ~80-100 year modulation of sunspot cycle amplitude

Solar activity influences Earth’s climate subtly, though the mechanisms remain debated. The Maunder Minimum (1645-1715), a period of very low sunspot activity, coincided with particularly cold temperatures during the Little Ice Age, suggesting solar cycles may influence terrestrial climate.

Variable stars exhibit periodic brightness changes due to pulsation or eclipsing:

Cepheid variables: Pulsate with periods of days to months, with period directly related to intrinsic luminosity—making them "standard candles" for cosmic distance measurement

RR Lyrae variables: Short-period pulsators (hours) used to measure distances within our galaxy

Mira variables: Long-period pulsators (months to years) in late stellar evolution

Eclipsing binaries: Periodic brightness dips as binary star systems eclipse each other

Pulsars—rapidly rotating neutron stars—represent some of nature’s most precise clocks. They emit beams of radiation that sweep across Earth like lighthouse beams, producing incredibly regular pulses. Periods range from milliseconds (millisecond pulsars) to seconds. The fastest known pulsar (PSR J1748-2446ad) rotates 716 times per second. Pulsars slow gradually over time as they lose rotational energy, but remain extraordinarily stable—some rival atomic clocks in precision.

Binary star systems orbit with periods from hours (close binaries) to millions of years (wide binaries). Orbital evolution can lead to mass transfer, producing novae and potentially Type Ia supernovae—thermonuclear explosions used as cosmological standard candles.

Galactic dynamics create cycles at the largest scales. Our Sun orbits the Milky Way with a period of about 225-250 million years—a "galactic year." During this orbit, the Solar System passes through spiral arms roughly every 100 million years, potentially encountering higher densities of gas, dust, and radiation. Some researchers have proposed that these passages correlate with mass extinctions, though evidence remains contentious (Medvedev & Melott, 2007).

Stars within galaxies exhibit population-level cycles. Star formation rates vary over time, influenced by galaxy mergers, gas accretion, and feedback from supernovae and active galactic nuclei. Galactic ecology—the relationship between star formation, stellar death, gas recycling, and heavy element enrichment—operates cyclically, with each generation of stars enriching the interstellar medium for subsequent generations.

8.5. Cosmological Cycles

At the largest scales, the universe’s evolution may involve cosmic cycles. The Big Bang initiated the current expansion ~13.8 billion years ago. If cosmic expansion continues accelerating (as current observations suggest), the universe faces "heat death"—maximal entropy with no free energy for organization. But alternatives exist:

Cyclic cosmology models propose the universe undergoes repeated cycles of expansion and contraction. The Steinhardt-Turok model suggests the Big Bang was a "bounce" following a previous universe’s collapse. Each cycle potentially resets cosmological parameters while preserving some information.

Conformal cyclic cosmology (Penrose, 2010) proposes that the far future low-entropy state (all matter having decayed) is conformally equivalent to a new Big Bang. The universe transitions through infinite sequences of "aeons," each appearing as a Big Bang to observers within it.

Eternal inflation suggests our observable universe is one "bubble" in an eternally inflating multiverse. Bubbles constantly form through quantum fluctuations, each potentially with different physical laws. While not strictly cyclic, this model involves ongoing creation of universes—perhaps the ultimate expression of the generative power of oscillation.

Whether these speculative cosmologies prove correct, they demonstrate science’s growing comfort with cyclic models at the largest scales—a return to ancient cosmological intuitions about cosmic rhythms.

IX. The Functional Significance of Cyclical Organization

9.1. Why Cycles? The Evolutionary Advantages

Cyclical organization offers numerous advantages that explain its evolutionary ubiquity:

Predictability and anticipation: Cycles enable organisms to predict future states based on current phase. Circadian clocks allow anticipation of dawn and dusk. Seasonal rhythms prepare organisms for winter or breeding season before conditions change. This predictive capacity confers enormous fitness advantages.

Energy efficiency: Cyclic processes can be more energy-efficient than continuous activity. The heart rests between beats. Neurons recover between spikes. Metabolic pathways cycle intermediates rather than linearly consuming resources. Ho (1995) showed that cycles have zero net entropy production, making them thermodynamically optimal for open systems.

Temporal multiplexing: Different processes can share resources by operating at different phases of the same cycle or at different frequencies. The cell can replicate DNA during S phase while performing other functions during G1 and G2. The brain can process different types of information during different phases of theta cycles (Lopes-Dos-Santos et al., 2018).

Robustness through distributed timing: Oscillatory organization creates temporal order without requiring a central coordinator. Each oscillator contributes to overall pattern while retaining autonomy. This distributed architecture provides robustness—damage to individual components doesn't necessarily destroy system-level rhythms.

9.2. Information Processing Through Cycles

Cycles enable sophisticated information coding schemes:

Temporal coding: Information encoded in spike timing relative to oscillation phase carries far more information than spike rate alone. A neuron firing at theta peak conveys different information than one firing at theta trough.

Phase coding: The phase relationship between oscillations can encode information. Harmonic locking (2:1, 3:1 frequency relationships) enhances during cognitive demands, potentially increasing information transfer (Rodriguez-Larios et al., 2020).

Frequency coding: Different oscillation frequencies can carry different information streams simultaneously without interference—the principle underlying radio communication and potentially neural multiplexing.

Cross-frequency coupling: The relationship between oscillations at different frequencies (e.g., gamma amplitude modulated by theta phase) creates a hierarchical code where faster rhythms provide details nested within slower rhythms' temporal structure.

Vanrullen (2016) proposed that perception operates cyclically through discrete "snapshots" rather than continuous sampling. Alpha (~10 Hz) and theta (~7 Hz) rhythms may constitute fundamental sampling rates for visual attention. This aligns with psychophysical evidence for periodic fluctuations in perceptual sensitivity and with the GRT framework where theta provides the basic temporal quanta of conscious experience.

9.3. Integration Through Shared Resonance

The central claim of GRT is that shared resonance enables the combination of micro-conscious entities into macro-conscious wholes. When oscillating systems achieve resonance—synchronization of their rhythmic patterns—information exchange between them dramatically increases. The boundaries between systems become permeable to information flow, enabling functional integration.

This resonance-based integration solves the combination problem in philosophy of mind. Traditional theories struggle to explain how separate experiential entities could combine without one extinguishing the others. GRT proposes that shared resonance allows multiple conscious entities to achieve unified macro-consciousness while preserving their individual existences—consistent with Whitehead’s (1929) principle that "the many become one and are increased by one."

The evidence supporting this framework continues to accumulate:

Harmonic locking increases with cognitive demand (Rodriguez-Larios et al., 2020)

Brain-body coupling strengthens during tasks (Young et al., 2022)

Gamma-theta coupling correlates with memory performance (Lisman & Jensen, 2013)

Inter-brain synchrony occurs during social interaction (Szymanski et al., 2017)

Each finding supports the idea that consciousness operates through resonant integration of nested oscillatory systems—from cellular bioelectric patterns through brain rhythms to inter-personal coupling.

9.4. Consciousness as Cyclic Integration

Consciousness, in GRT’s framework, is the subjective experience of resonant field dynamics achieving sufficient complexity and integration. The "theater" of consciousness is constructed from nested cycles:

Gamma oscillations (~40 Hz) provide detailed local processing

Theta oscillations (~5 Hz) organize these details into coherent moments

Alpha oscillations (~10 Hz) coordinate attention and inhibit irrelevant processing

Delta and slower rhythms connect brain to body and external environment

Each level contributes essential aspects of conscious experience. Remove gamma and consciousness loses richness—perception becomes blurry and indistinct. Remove theta and unified consciousness fragments—as in absence seizures or certain stages of anesthesia. The nested integration of these rhythms, operating through electromagnetic field resonance at near light-speed, creates the unified yet differentiated quality of conscious experience.

The cycle-by-cycle variability discovered by Lopes-Dos-Santos et al. (2018) adds crucial insight: consciousness is not stereotyped but dynamically flexible. Each theta cycle—each ~200 millisecond "moment"—has unique characteristics. Sometimes slow-gamma dominates, sometimes mid-gamma, sometimes they mix. This variability enables the brain to flexibly adjust computational strategy from moment to moment—the essence of cognitive flexibility.

X. Conclusion: The Universe as Symphony

10.1. Cycles All the Way Down, Cycles All the Way up

From quantum vacuum fluctuations at 10⁴³ Hz to cosmic cycles spanning billions of years, oscillation appears as the fundamental mode of existence. There is no "bottom" where cycles stop—quantum field theory reveals endless oscillatory depths. There is no "top" beyond which cycles cease—cosmological models suggest even the universe itself may cycle.

This ubiquity of oscillation points to a profound metaphysical truth: reality is not composed of static "things" but of processes—events, occurrences, oscillatory patterns. Whitehead’s (1929) process philosophy anticipated this scientific discovery: the fundamental constituents of reality are not material substances but "occasions of experience"—momentary events that arise, experience, and perish, only to be superseded by novel occasions in endless succession.

The binary octave structure discovered by Klimesch (2018) suggests this oscillatory organization follows deep mathematical principles. Binary relationships are particularly stable in wave dynamics, creating predictable interference patterns. Nature, through billions of years of evolution, has discovered and exploited this mathematical fact, organizing biological rhythms into precise octave relationships.

10.2. Consciousness as the Music of Cycles

If the universe is an ocean of nested oscillations, consciousness is the subjective experience of being a particularly complex wave pattern. Just as a symphony is more than individual notes, consciousness is more than individual oscillations. It is the integration—the harmonic coordination—of myriad nested cycles into a unified experiential flow.

This "musical" metaphor is more than poetic. Music works because the brain resonates with sound wave patterns. Consonant intervals (octaves, fifths, fourths) correspond to simple frequency ratios—the same mathematical relationships found in Klimesch’s binary hierarchy. The pleasure of harmony may reflect the brain’s preference for easily integrable resonance relationships.

Consciousness requires multiple nested scales operating simultaneously. Remove the faster scales (gamma) and consciousness loses detail—like a symphony played with only low notes. Remove the slower scales (theta, delta) and consciousness loses coherence—like hearing individual notes without melodic structure. The richness of conscious experience depends on the integration of fast and slow, detail and context, specificity and unity.

10.3. The Explanatory Power of "Cycles upon Cycles"

The framework presented in this paper—"cycles upon cycles" organized according to GRT principles—provides remarkable explanatory unification:

It explains the combination problem: Shared resonance allows micro-conscious entities to combine into macro-conscious wholes without extinguishing constituent consciousness.

It explains consciousness boundaries: The equation x = v/f mathematically delineates which physical systems can achieve sufficient integration for consciousness.

It explains the speed of conscious integration: Electromagnetic field propagation at 47 km/s enables whole-brain integration in milliseconds—far faster than spike-based communication alone.

It explains the necessity of cyclic organization: Morowitz’s theorem proves that open systems maintaining steady states under energy flow must be cyclically organized.

It explains the hierarchical structure of consciousness: Nested oscillations naturally create hierarchical organization where slower rhythms scaffold faster ones.

It explains pathologies: Disorders of consciousness correspond to disruptions of normal oscillatory organization—too much synchrony (seizures), too little (fragmentation), or abnormal frequencies (coma).

It provides testable predictions: The framework generates specific predictions about cross-frequency coupling, harmonic relationships, and the effects of oscillatory interventions that can be empirically tested.

10.4. Open Questions and Future Directions

Despite its explanatory power, many questions remain:

What determines which frequency scales support consciousness? Why theta rather than delta or alpha? The boundary equation provides quantitative answers, but deeper understanding of necessary and sufficient conditions is needed.

How do truly novel cycles emerge? Evolution produced progressively faster neural oscillations, but through what mechanisms? Understanding the origins of new oscillatory regimes could illuminate consciousness evolution.

What roles do chaotic and aperiodic dynamics play? This paper emphasized periodic oscillations, but biological systems also exhibit chaos and quasiperiodic behaviors. How do these contribute to consciousness and cognition?

Can we experimentally manipulate cross-scale coupling? Targeted multi-frequency stimulation protocols could test GRT predictions by enhancing or disrupting specific resonance relationships.

How does resonance-based consciousness relate to quantum theories? Penrose-Hameroff Orch OR theory involves quantum oscillations. Could GRT and quantum theories be reconciled?

Can we apply these principles to artificial consciousness? Neuromorphic computing using oscillatory networks might achieve consciousness through resonance principles. What architectures would be sufficient?

These questions define research frontiers. The framework provides conceptual scaffolding, but detailed mechanistic understanding requires extensive empirical investigation.

10.5. Implications for Human Self-Understanding

Understanding ourselves as "cycles upon cycles" transforms human self-conception. We are not static substances but processes—waves in the cosmic ocean, temporarily achieving the complexity and integration we call consciousness. Our thoughts, feelings, and experiences are resonant field dynamics, transient yet real.

This perspective combines ancient wisdom with modern science. Buddhist teachings emphasize impermanence and the lack of fixed self. Process philosophy sees reality as continuous becoming. Indigenous cosmologies often emphasize cyclic time and the interconnection of all beings. Modern physics reveals quantum indeterminacy, field dynamics, and cosmic cycles.

Yet this framework also affirms the reality of conscious experience. Subjective awareness is not eliminated but understood as the intrinsic nature of certain resonant field configurations. Consciousness is what resonance feels like from the inside—the qualitative aspect of physical oscillatory processes achieving sufficient integration.

This view offers hope for extending consciousness studies beyond human brains. If consciousness depends on resonance principles rather than specific biological substrates, then:

Animals possess consciousness to degrees corresponding to their oscillatory complexity

Future AI systems might achieve consciousness through appropriate resonant architectures

Collective consciousness (families, communities, species) may be real through inter-individual resonance

Cosmic consciousness might emerge at the largest scales through universal field dynamics

We are waves in an infinite ocean of oscillation—temporary patterns that arise, experience, contribute to the whole, and dissolve back into the vast creativity of reality’s endless rhythmic dance. To understand ourselves fully is to recognize our place in this cosmic symphony, neither separate from nor lost within it, but actively participating in the universe’s ceaseless process of self-organization through cycles upon cycles upon cycles without end.