Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

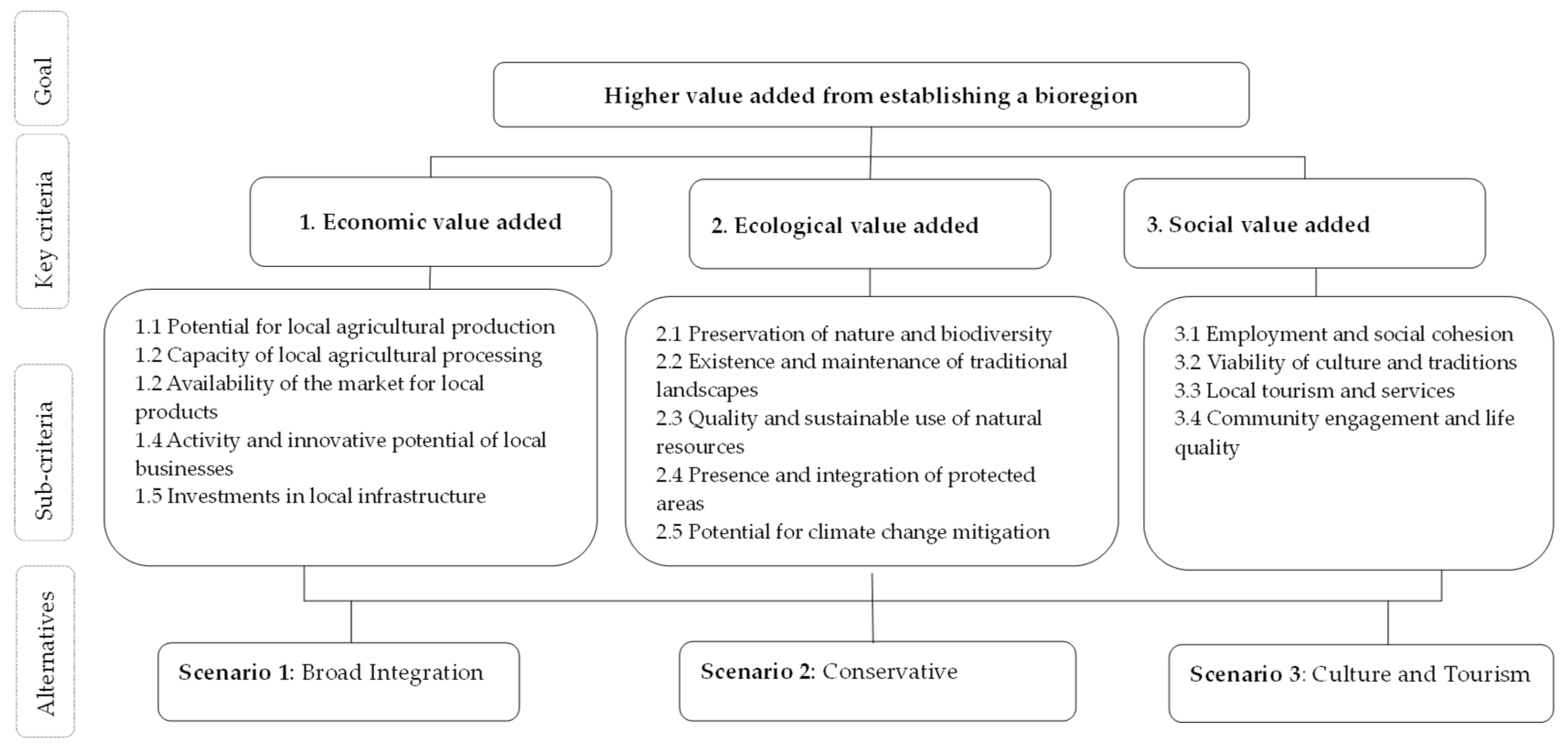

2. Materials and Methods

- • if CR≤0.10, comparisons are considered coherent and are used without further verification;

- • if 0.10<CR≤0.20, an expert's rating was re-discussed, paying attention to the contradictions identified. If the expert reasonably justified their vision and the logic of the comparison, the respective rating was considered acceptable and included in the subsequent analysis;

- • if CR>0.20, an expert was asked to redo their pair comparison matrix to find discrepancies and reach greater coherence.

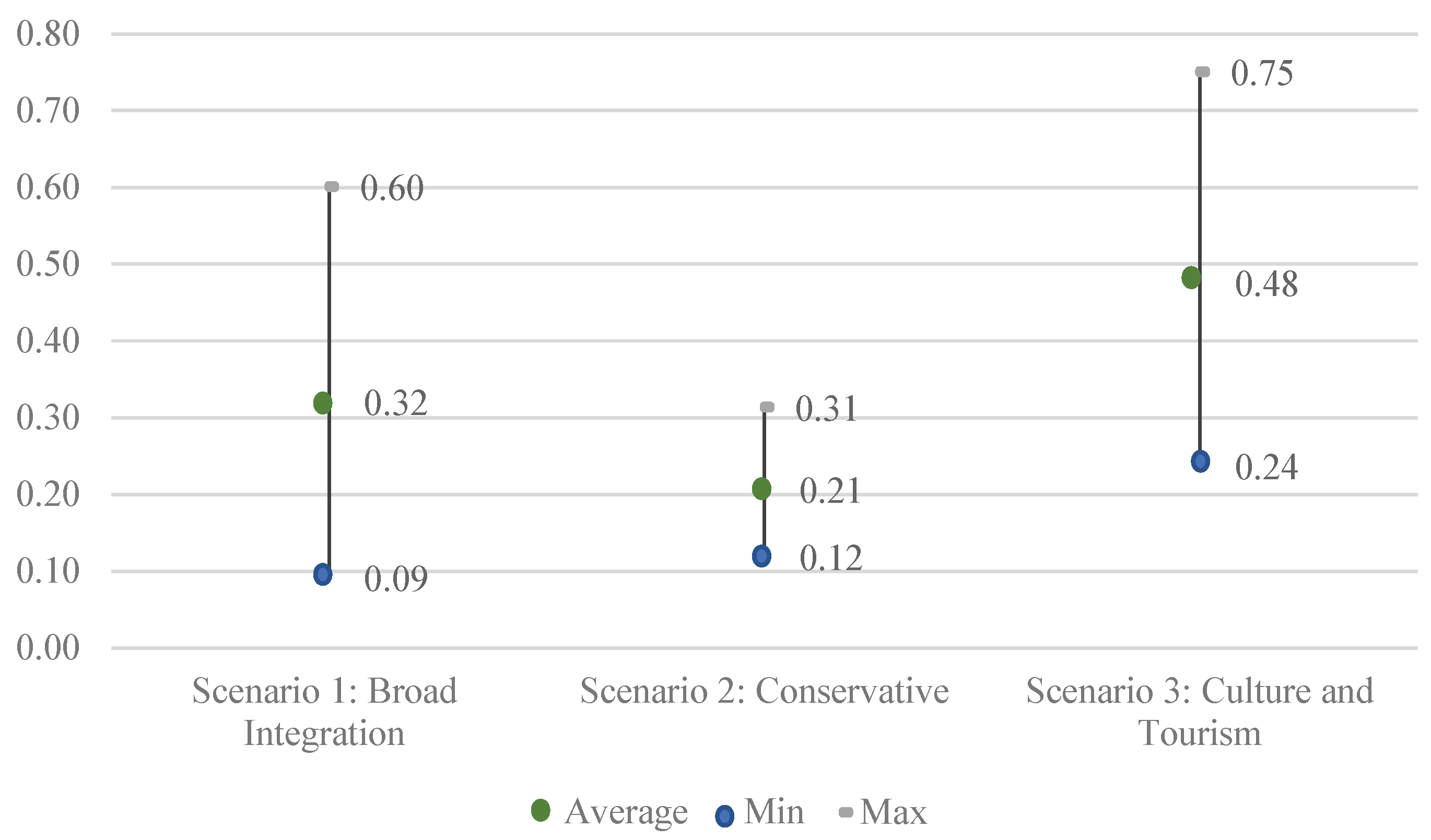

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AREI | Institute of Agricultural Resources and Economics |

| ChatGPT | Large language model developed by OpenAI |

| CR | Coherence Ratio |

| EVI | Ecoregional Vocation Index |

| LOSP | Cooperation Council of Agricultural Organisations |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| OpenAI | Artificial intelligence research organization developing large language models |

| PGI | Protected Geographical Indication |

| PDO | Protected Designation of Origin |

| RoL | Republic of Latvia |

Appendix A

| Criteria | Individual Expert Evaluations | Minimum, Average, and Maximum Values of Individual Expert Evaluations | Combined Expert Group Evaluation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert A | Expert B | Expert C | Expert D | Expert E | Expert F | ||||||

| Main criteria | Weight vector | Weight vector | Weight vector | Weight vector | Weight vector | Weight vector | Aver | Min | Max | Weight vector | Global Weight |

| 1. Economic Added Value (AV) | 0.091 | 0.333 | 0.088 | 0.321 | 0.083 | 0.225 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.173 | na* |

| 2. Ecological Added Value (AV) | 0.455 | 0.333 | 0.243 | 0.225 | 0.724 | 0.321 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.72 | 0.387 | na |

| 3. Social Added Value (AV) | 0.455 | 0.333 | 0.669 | 0.454 | 0.193 | 0.454 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.439 | na |

| 1. Economic Sub-criteria | |||||||||||

| 1.1. Agricultural Potential | 0.142 | 0.073 | 0.058 | 0.419 | 0.182 | 0.050 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.133 | 0.023 |

| 1.2. Food Processing | 0.166 | 0.162 | 0.058 | 0.226 | 0.137 | 0.075 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.146 | 0.025 |

| 1.3. Market Accessibility | 0.214 | 0.377 | 0.170 | 0.048 | 0.069 | 0.134 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.160 | 0.028 |

| 1.4. Entrepreneurial Activity | 0.404 | 0.218 | 0.163 | 0.164 | 0.275 | 0.237 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.275 | 0.048 |

| 1.5. Infrastructure Investments | 0.074 | 0.171 | 0.550 | 0.143 | 0.336 | 0.504 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.287 | 0.050 |

| 2. Ecological Sub-criteria | |||||||||||

| 2.1. Biodiversity | 0.247 | 0.253 | 0.467 | 0.249 | 0.085 | 0.064 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.228 | 0.088 |

| 2.2. Traditional Landscapes | 0.159 | 0.069 | 0.236 | 0.367 | 0.183 | 0.076 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.37 | 0.187 | 0.072 |

| 2.3. Quality of Natural Resources | 0.247 | 0.226 | 0.091 | 0.266 | 0.342 | 0.071 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.212 | 0.082 |

| 2.4. Integration of Protected Areas | 0.159 | 0.226 | 0.154 | 0.078 | 0.262 | 0.283 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.212 | 0.082 |

| 2.5. Climate Change Mitigation | 0.189 | 0.226 | 0.052 | 0.040 | 0.129 | 0.506 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.161 | 0.062 |

| 3. Social Sub-criteria | |||||||||||

| 3.1. Employment and Social Cohesion | 0.100 | 0.192 | 0.058 | 0.300 | 0.077 | 0.325 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.154 | 0.068 |

| 3.2. Cultural and Traditional Vitality | 0.300 | 0.242 | 0.282 | 0.325 | 0.159 | 0.192 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.261 | 0.115 |

| 3.3. Local Tourism and Services | 0.300 | 0.242 | 0.145 | 0.051 | 0.263 | 0.242 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.196 | 0.086 |

| 3.4. Community Engagement and Quality of Life | 0.300 | 0.325 | 0.515 | 0.325 | 0.501 | 0.242 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 0.389 | 0.171 |

| Scenario Evaluation According to Main Criterion 1 – Economic Added Value (AV) | |||||||||||

| 1.1. Agricultural Potential | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.633 | 0.724 | 0.140 | 0.061 | 0.480 | 0.435 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.391 | 0.009 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.260 | 0.193 | 0.286 | 0.216 | 0.115 | 0.078 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.221 | 0.005 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.106 | 0.083 | 0.574 | 0.723 | 0.405 | 0.487 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.387 | 0.009 |

| 1.2.Food Processing | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.655 | 0.111 | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.429 | 0.480 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.66 | 0.249 | 0.006 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.187 | 0.111 | 0.643 | 0.417 | 0.143 | 0.115 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.64 | 0.252 | 0.006 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.158 | 0.778 | 0.283 | 0.805 | 0.429 | 0.405 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.81 | 0.499 | 0.013 |

| 1.3. Market Accessibility | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.405 | 0.111 | 0.083 | 0.187 | 0.211 | 0.429 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.272 | 0.008 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.480 | 0.111 | 0.724 | 0.158 | 0.102 | 0.143 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.72 | 0.242 | 0.007 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.115 | 0.778 | 0.193 | 0.655 | 0.686 | 0.429 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 0.486 | 0.013 |

| 1.4. Entrepreneurial Activity | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.260 | 0.111 | 0.083 | 0.179 | 0.260 | 0.429 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.241 | 0.011 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.633 | 0.111 | 0.724 | 0.136 | 0.106 | 0.143 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.72 | 0.276 | 0.013 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.106 | 0.778 | 0.193 | 0.685 | 0.633 | 0.429 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 0.483 | 0.023 |

| 1.5. Infrastructure Investments | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.143 | 0.111 | 0.106 | 0.187 | 0.724 | 0.429 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.72 | 0.262 | 0.013 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.429 | 0.111 | 0.633 | 0.158 | 0.083 | 0.143 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.63 | 0.239 | 0.012 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.429 | 0.778 | 0.260 | 0.655 | 0.193 | 0.429 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.499 | 0.025 |

| Scenario Evaluation According to Main Criterion 2 – Ecological Added Value (AV) | |||||||||||

| 2.1. Biodiversity | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.794 | 0.111 | 0.066 | 0.061 | 0.574 | 0.574 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.310 | 0.027 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.139 | 0.111 | 0.623 | 0.216 | 0.140 | 0.140 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.255 | 0.023 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.067 | 0.778 | 0.311 | 0.723 | 0.286 | 0.286 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.435 | 0.038 |

| 2.2. Traditional Landscapes | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.777 | 0.111 | 0.066 | 0.057 | 0.200 | 0.429 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.234 | 0.017 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.155 | 0.111 | 0.623 | 0.649 | 0.200 | 0.143 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.65 | 0.327 | 0.024 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.069 | 0.778 | 0.311 | 0.295 | 0.600 | 0.429 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.439 | 0.032 |

| 2.3. Quality of Natural Resources | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.794 | 0.111 | 0.069 | 0.061 | 0.633 | 0.633 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.347 | 0.028 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.139 | 0.111 | 0.777 | 0.216 | 0.260 | 0.260 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 0.353 | 0.029 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.067 | 0.778 | 0.155 | 0.723 | 0.106 | 0.106 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.300 | 0.025 |

| 2.4. Integration of Protected Areas | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.794 | 0.200 | 0.083 | 0.061 | 0.746 | 0.286 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 0.326 | 0.027 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.067 | 0.200 | 0.724 | 0.216 | 0.134 | 0.140 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.72 | 0.252 | 0.021 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.139 | 0.600 | 0.193 | 0.723 | 0.120 | 0.574 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.72 | 0.422 | 0.035 |

| 2.5.Climate Change Mitigation | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.818 | 0.143 | 0.061 | 0.333 | 0.429 | 0.574 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.375 | 0.023 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.091 | 0.143 | 0.723 | 0.333 | 0.429 | 0.286 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.72 | 0.351 | 0.022 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.091 | 0.714 | 0.216 | 0.333 | 0.143 | 0.140 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.274 | 0.017 |

| Scenario Evaluation According to Main Criterion 3 – Social Added Value (AV) | |||||||||||

| 3.1. Employment and Social Cohesion | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.686 | 0.111 | 0.083 | 0.158 | 0.600 | 0.454 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 0.325 | 0.022 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.102 | 0.111 | 0.724 | 0.187 | 0.200 | 0.225 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.72 | 0.256 | 0.017 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.211 | 0.778 | 0.193 | 0.655 | 0.200 | 0.321 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.419 | 0.028 |

| 3.2. Cultural and Traditional Vitality | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.286 | 0.111 | 0.081 | 0.071 | 0.633 | 0.231 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.191 | 0.022 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.140 | 0.111 | 0.168 | 0.180 | 0.106 | 0.077 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.137 | 0.016 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.574 | 0.778 | 0.751 | 0.748 | 0.260 | 0.692 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.78 | 0.672 | 0.077 |

| 3.3. Local Tourism and Services | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.286 | 0.091 | 0.081 | 0.069 | 0.633 | 0.155 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.171 | 0.015 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.140 | 0.091 | 0.168 | 0.155 | 0.106 | 0.069 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.127 | 0.011 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.574 | 0.818 | 0.751 | 0.777 | 0.260 | 0.777 | 0.66 | 0.26 | 0.82 | 0.702 | 0.060 |

| 3.4. Community Engagement and Quality of Life | |||||||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.686 | 0.091 | 0.216 | 0.053 | 0.724 | 0.454 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.324 | 0.055 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.102 | 0.091 | 0.061 | 0.474 | 0.083 | 0.225 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.167 | 0.029 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.211 | 0.818 | 0.723 | 0.474 | 0.193 | 0.321 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.82 | 0.509 | 0.087 |

| Criteria | Expert A | Expert B | Expert C | Expert D | Expert E | Expert F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main criteria | Global Weight | Global Weight | Global Weight | Global Weight | Global Weight | Global Weight |

| 1. Economic Added Value (AV) | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 2. Ecological Added Value (AV) | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 3. Social Added Value (AV) | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 1. Economic Sub-criteria | ||||||

| 1.1. Agricultural Potential | 0.013 | 0.024 | 0.005 | 0.134 | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| 1.2. Food Processing | 0.015 | 0.054 | 0.005 | 0.072 | 0.011 | 0.017 |

| 1.3. Market Accessibility | 0.019 | 0.126 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.030 |

| 1.4. Entrepreneurial Activity | 0.037 | 0.073 | 0.014 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.053 |

| 1.5. Infrastructure Investments | 0.007 | 0.057 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.028 | 0.114 |

| 2. Ecological Sub-criteria | ||||||

| 2.1. Biodiversity | 0.112 | 0.084 | 0.114 | 0.056 | 0.061 | 0.021 |

| 2.2. Traditional Landscapes | 0.072 | 0.023 | 0.057 | 0.083 | 0.132 | 0.024 |

| 2.3. Quality of Natural Resources | 0.112 | 0.075 | 0.022 | 0.060 | 0.247 | 0.023 |

| 2.4. Integration of Protected Areas | 0.072 | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.017 | 0.189 | 0.091 |

| 2.5. Climate Change Mitigation | 0.086 | 0.075 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.093 | 0.162 |

| 3. Social Sub-criteria | ||||||

| 3.1. Employment and Social Cohesion | 0.045 | 0.064 | 0.039 | 0.136 | 0.015 | 0.148 |

| 3.2. Cultural and Traditional Vitality | 0.136 | 0.081 | 0.188 | 0.147 | 0.031 | 0.087 |

| 3.3. Local Tourism and Services | 0.136 | 0.081 | 0.097 | 0.023 | 0.051 | 0.110 |

| 3.4. Community Engagement and Quality of Life | 0.136 | 0.108 | 0.345 | 0.147 | 0.097 | 0.110 |

| Scenario Evaluation According to Main Criterion 1 – Economic Added Value (AV) | ||||||

| 1.1. Agricultural Potential | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.097 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| 1.2.Food Processing | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.030 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.002 | 0.042 | 0.001 | 0.058 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| 1.3. Market Accessibility | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.009 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.002 | 0.098 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.013 |

| 1.4. Entrepreneurial Activity | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.023 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.008 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.004 | 0.056 | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.015 | 0.023 |

| 1.5. Infrastructure Investments | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.020 | 0.049 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.016 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.003 | 0.044 | 0.013 | 0.030 | 0.005 | 0.049 |

| Scenario Evaluation According to Main Criterion 2 – Ecological Added Value (AV) | ||||||

| 2.1. Biodiversity | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.089 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.035 | 0.012 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.071 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.007 | 0.066 | 0.035 | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.006 |

| 2.2. Traditional Landscapes | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.056 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.010 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.054 | 0.026 | 0.003 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.024 | 0.079 | 0.010 |

| 2.3. Quality of Natural Resources | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.089 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.157 | 0.014 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.064 | 0.006 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.007 | 0.059 | 0.003 | 0.043 | 0.026 | 0.002 |

| 2.4. Integration of Protected Areas | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.057 | 0.015 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.141 | 0.026 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.027 | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.013 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.010 | 0.045 | 0.007 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.052 |

| 2.5.Climate Change Mitigation | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.070 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.040 | 0.093 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.040 | 0.046 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.008 | 0.054 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.023 |

| Scenario Evaluation According to Main Criterion 3 – Social Added Value (AV) | ||||||

| 3.1. Employment and Social Cohesion | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.031 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.009 | 0.067 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.003 | 0.033 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.010 | 0.050 | 0.007 | 0.089 | 0.003 | 0.047 |

| 3.2. Cultural and Traditional Vitality | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.039 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.020 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.027 | 0.003 | 0.007 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.078 | 0.063 | 0.141 | 0.110 | 0.008 | 0.060 |

| 3.3. Local Tourism and Services | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.039 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.017 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.019 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.008 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.078 | 0.066 | 0.073 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.085 |

| 3.4. Community Engagement and Quality of Life | ||||||

| Scenario 1: Broad Integration | 0.094 | 0.010 | 0.074 | 0.008 | 0.070 | 0.050 |

| Scenario 2: Conservative | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.008 | 0.025 |

| Scenario 3: Culture and Tourism | 0.029 | 0.089 | 0.249 | 0.070 | 0.019 | 0.035 |

References

- Cardillo, M.C.; De Felice, P. A potential example of sustainability in the Italian rural landscape: the Valle di Comino biodistrict in southern Lazio. BelGeo. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, C.; Pugliese, P.; Barataud, F.; Berti, G.; Rossi, A. Italian biodistricts and French territorial food projects: how science-policy-experience interplays shape the framings of transitions towards sustainable territorial food systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1223270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovic, L.; Agbolosoo-Mensah, O.A. Biodistricts as a tool to revitalize rural territories and communities: insights from the biodistrict Cilento. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1267985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraljevic, B.; Zanasi, C. Drivers affecting the relation between biodistricts and school meals initiatives: evidence from the Cilento biodistrict. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1235871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, A.; Randelli, F. Spaces of sustainable transformation at territorial level: an analysis of biodistricts and their role for agroecological transitions. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 1198–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, C.; Orsi, L.; Bergamelli, C.; Sturla, A. Bio-districts and the territory: evidence from a regression approach. Aestimum. 2021, 79, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, P.; Antonelli, A.; Basile, S. Full case study report: Bio-Distretto Cliento –Italy. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/29252/7/29252.pdf (accessed on 04.07.2025).

- Favilli, E.; Ndah, T.H.; Barabanova, Y. Multi-actor interaction and coordination in the development of a territorial innovation project: some insights from the Cilento Bio‐district in Italy. In Proceedings of the 13th European IFSA Symposium, Chania, Greece (05.07.2018). Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20183360701 (accessed on 08.03.2024).

- Belliggiano, A.; Bindi, L.; Ievoli, C. Walking along the sheeptrack: Rural tourism, ecomuseums, and bio-cultural heritage. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 8264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotten, R.; Bui, S.; Pugliese, P.; Schermer, M.; Lamine, C. Organic values-based supply chains as a tool for territorial development: a comparative analysis of three European organic regions. IJSAF. 2017, 24, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuoco, E.; Salvatore, B.; BIO-DISTRICTS to boost organic production. The best practices of BioDistretto Cilento. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/23977/7/23977.pdf (accessed on 09.02.2025).

- Zanasi, C.; Basile, S.; Paoletti, F.; Pugliese, P.; Rota, C. Design of a Monitoring Tool for Eco-Regions. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 536392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poponi, S.; Arcese, G.; Mosconi, E.M.; Pacchera, F.; Martucci, O.; Elmo, G.C. Multi-Actor Governance for a Circular Economy in the Agri-Food Sector: Bio-Districts. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guareschi, M.; Maccari, M.; Sciurano, J.; Arfini, F.; Pronti, A. A methodological approach to upscale toward an agroecology system in EU-LAFSS: the case of the Parma bio-district. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, G.; Licciardo, F.; Verrascina, M.; Zanetti, B. The agroecological approach as a model for multifunctional agriculture and farming towards the European Green Deal 2030: Some evidence from the Italian experience. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Proškina, L.; Paula, L.; Kaufmane, D. Modelling the multiplier effect of a local food system. Agron. Res. 2021, 19, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Paula, L.; Janmere, L.; Kauf-mane, D.; Proškina, L. Local food development perspectives in Latvia: A val-ue-oriented view. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, M.; Barone, V.; Silvestri, F.; Tassinari, M. Planning sustainable development of local productive systems: A methodological approach for the analytical identification of Ecoregions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Megne, I.; Proskina, L.; Paula, L.; Kaufmane, D.; Pelse, M. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Formation of Bioregions. Sustainability. 2025, 17, 8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytic hierarchy process. Publisher: McGraw-Hill International Book Co. New York-London, 1980; p. 287.

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Models, Methods, Concepts & Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process Second Edition. Publisher: Springer Science Business Media, New York, USA, 2012; p. 341. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Z.K.; Szádoczki, Z.; Bozóki, S.; Stănciulescu, G.C.; Szabo, D. An Analytic Hierarchy Process Approach for Prioritisation of Strategic Objectives of Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.; Ferreira, J.C.; Antunes, P. Green Infrastructure Planning Principles: Identification of Priorities Using Analytic Hierarchy Process. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yrlioglu, I.; Kara, C. Sustainable Urban Design Approach for Public Spaces Using an Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). Land. 2025, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltynowski, M.; Szajt, M. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in Rural Land-use Planning in Poland: A Case Study of Zawidz Commune. PPR, 2020, 36, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleniacz, G.; Skrzypczak, I.; Leń, P. Decision-making models using the Analytical Hierarchy Process in the urgency of land consolidation works. J. Water Land Dev. 2019, 43, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palka, G.; Oliveira, E.; Pagliarin, S.; Hersperger, A.M. Strategic spatial planning and efficacy: an analytic hierarchy process (AHP) approach in Lyon and Copenhagen. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 29, 1174–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Babac, A.; Pauer, F.; Damm, K.; von der Schulenburg, J.M. Measuring patients' priorities using the Analytic Hierarchy Process in comparison with Best-Worst-Scaling and rating cards: methodological aspects and ranking tasks. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauer, F.; Schmidt, K.; Babac, A.; Damm, K.; Frank, K.; Graf von der Schulenburg, M. Comparison of different approaches applied in Analytic Hierarchy Process – an example of information needs of patients with rare diseases. BMC med. inform. decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, V.A.P.; Gomes, L.F.A.M. Consistency Improvement in the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Mathematics. 2024, 12, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzins, A. Evaluation and Management of Land Use. Scientific Monograph. Publisher: RTU Izdevniecība, Rīga, Latvia 2016; p.270. https://wpweb2-prod.rtu.lv/ebooks/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2020/02/9789934223921_Zemes-izmantosanas-PDF.pdf.

- Jeroscenkova, L.; Rivza, B.; Rivza, P. Decision making on the use of cultural heritage in rural tourism development in Latvia. Res. Rural Dev. 2016, 2, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, R. Validation examples of the Analytic Hierarchy Process and Analytic Network Process. Math. Comput. Model. 2007, 46, 840–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabellini, G. Culture and Institutions: Economic Development in the Regions of Europe. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 8, 77–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvāns, Ē. Socially demographic portrait of a happy and unhappy resident of Latgale. Society Integration Education. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. 2018, 7, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, S.; Cuoco, E. Territorial bio-districts to boost organic production. Available online: https://www.ideassonline.org/public/pdf/BrochureBiodistrettiENG.pdf (accessed on 01.08.2025).

| Rating | Relative Significance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Both elements are equally significant | No advantages for either |

| 3 | One of the elements is slightly more significant | Slight advantage |

| 5 | More significant | Clear advantage |

| 7 | Much more significant | Very pronounced advantage |

| 9 | Absolutely more significant | One of the elements clearly prevails |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate values | Used only in the case of an ultimate compromise if the significance is between two degrees |

| Main Criteria | Individual Expert Ratings of Criteria (Weight) | Combined Weight of Expert Group Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | ||

| 1.Economic value added | 0.091 | 0.333 | 0.088 | 0.321 | 0.083 | 0.225 | 0.173 |

| 2.Ecological value added | 0.455 | 0.333 | 0.243 | 0.225 | 0.724 | 0.321 | 0.387 |

| 3.Social value added | 0.455 | 0.333 | 0.669 | 0.454 | 0.193 | 0.454 | 0.439 |

| Criteria | Individual Expert Ratings of Criteria (Weight) | Criterion Weight | Global Criterion Weight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A* | B | C | D | E | F | |||

| Economic value added | ||||||||

| 1.1. Agricultural potential | 0.142 | 0.073 | 0.058 | 0.419 | 0.182 | 0.050 | 0.133 | 0.023 |

| 1.2. Food processing | 0.166 | 0.162 | 0.058 | 0.226 | 0.137 | 0.075 | 0.146 | 0.025 |

| 1.3. Market access | 0.214 | 0.377 | 0.170 | 0.048 | 0.069 | 0.134 | 0.160 | 0.028 |

| 1.4. Entrepreneurial activity | 0.404 | 0.218 | 0.163 | 0.164 | 0.275 | 0.237 | 0.275 | 0.048 |

| 1.5. Infrastructure investments | 0.074 | 0.171 | 0.550 | 0.143 | 0.336 | 0.504 | 0.287 | 0.050 |

| Ecological value added | ||||||||

| 2.1. Biodiversity | 0.247 | 0.253 | 0.467 | 0.249 | 0.085 | 0.064 | 0.228 | 0.088 |

| 2.2. Traditional landscapes | 0.159 | 0.069 | 0.236 | 0.367 | 0.183 | 0.076 | 0.187 | 0.072 |

| 2.3. Quality of natural resources | 0.247 | 0.226 | 0.091 | 0.266 | 0.342 | 0.071 | 0.212 | 0.082 |

| 2.4. Integration of protected areas | 0.159 | 0.226 | 0.154 | 0.078 | 0.262 | 0.283 | 0.212 | 0.082 |

| 2.5. Climate change mitigation | 0.189 | 0.226 | 0.052 | 0.040 | 0.129 | 0.506 | 0.161 | 0.062 |

| Social value added | ||||||||

| 3.1. Employment and social cohesion | 0.100 | 0.192 | 0.058 | 0.300 | 0.077 | 0.325 | 0.154 | 0.068 |

| 3.2. Viability of culture and traditions | 0.300 | 0.242 | 0.282 | 0.325 | 0.159 | 0.192 | 0.261 | 0.115 |

| 3.3. Local tourism and services | 0.300 | 0.242 | 0.145 | 0.051 | 0.263 | 0.242 | 0.196 | 0.086 |

| 3.4. Community engagement and quality of life | 0.300 | 0.325 | 0.515 | 0.325 | 0.501 | 0.242 | 0.389 | 0.171 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).