1. Introduction

Baldios (Portugal) and

montes veciñais en man común (MVMC) (Galicia, northwest Spain) are privately-owned lands characterized by collective ownership by the resident community who live in a particular location [

1,

2]. This type of property of Germanic origin and unique in Europe, dates back to a time before the development of agriculture and livestock [

3,

4]. Both persisted and continued throughout and after the time of the pre-Roman

castros, or fortified settlements, survived the numerous occupations of the Iberian Peninsula, and outgrew the Formation of European Nations [

5]. They continued to exist and were acknowledged or allocated during the evolving process from the medieval economy to the modern capitalist-type economy. Having been subjected to the so-called Spanish Mendizábal confiscation that took place in the 18th century, communal land survived the 20th century authoritarian interventions by the regimes of Franco (Spain) and Salazar (Portugal) and have remained to the present [

6].

Land ownership is atypical in that it is both private and collective, belonging to residents, known as commoners (

comuneros in Spanish), who form the Common Land Community, a community of land users based on a unique system of collective ownership. The communal lands cannot be divided, sold, or transferred, and the only way to become a commoner is by living in that location [

5,

7]. Communal lands are very important in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. On the one hand, because they occupy an area of almost one million hectares, i.e. more than a quarter of the region’s total area [

2,

4]. On the other hand, due to the incredible historical strength shown, since local communities had to manage their properties in the face of different external agents with a great capacity for land intervention and planning [

1,

3]. The region is home to small properties with about 400,000 ha of

baldios in northern Portugal and 600,000 of MVMC in Galicia. The average size of the individual parcels’ ranges between 200 ha in Galicia and 500 ha in Portugal. Nearly 3,000 communities in Galicia and 1,000 in northern Portugal own communal lands [

8,

9]. Due to the policies developed during the dictatorial regimes, both in Spain and Portugal, which converted the ownership of communal land into public land, now the main use is forestry [

5,

8]. However, since the property was restored to the communities, many traditional uses were recovered (e.g. extensive grazing, subsistence agriculture, use of firewood...) [

3,

9]. Now, the natural resources are underutilized for various reasons. Nevertheless, the area occupied by communal lands, the heterogeneity of forest and non-forest resources, and the non-transferable nature of ownership have made communal lands a model territory to carry out rural development projects based on sustainable agricultural and forestry exploitation [

10]. There continues to be a strong relationship between local people and the land, while the nature of that relationship is very different from when agriculture was the central, sometimes the only, activity [

9].

As we have commented, now the main use of the communal lands is forestry. So, there are two main types of management: direct by the local communities and co-management with the State and the Autonomous Community, in Portugal and Galicia respectively [

1,

11]. Mainly due to the depopulation of rural areas and a change in social behaviour, the participation of local population in the management of communal lands has been reduced [

12]. Attendance at the annual meetings of the owners is very low, which negatively affects decision-making for the land sustainable management [

13]. The number of communities that delegate the supervision of their land is increasing (in the Portuguese case by delegating to Parish Committees). Examples of successful management of communal land are mostly dependent on the strong leadership of one or more community members [

8,

14]. In the co-management system, the main decisions (i.e. timber harvesting, forestation or reforestation and other silvicultural treatments) are taken by the Forestry Services. Any income obtained from harvesting the timber is shared between the Forestry Services and the communities, according to rates established by law. Although Forestry Service’s dominate the technical aspects of forest harvesting, the slow and routine operating style is not coherent with the required dynamic administration responses [

2,

9].

The aim of the study was to apply a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to evaluate the opinion and preferences of stakeholders in relation to the best land management alternatives and associated trade-offs. The need for and the advantages of stakeholder participation in a multi-criterion decision-aid have been increasingly acknowledged and valued [

8,

11,

12]. Given the versatility, it is complicated to use another viable alternative to the pairwise comparison methods for the development of public policies [

15].

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The

Galicia-North Portugal region, located in the northwest Iberian Peninsula, covers a surface area of more than 5 million hectares (

Figure 1). The lithology is very heterogeneous with granite, schist, slate and quartzite parent material giving rise to acidic soils. The climate is Humid Oceanic with Mediterranean influence in the most continental zone. The annual precipitation ranges between 1100 to over 2000 mm, with summer precipitation around of 200 mm, occasionally 300 mm, due to the Atlantic influence at various places [

3,

5,

16]. The potential vegetation is made up of different species of deciduous and marcescent oaks, mainly

Quercus robur L. and

Q. pyrenaica Willd., as well other species such as chestnut, birch and even beech. They form different phytosociological associations included in the order

Quercetalia robori-petraeae [

16].

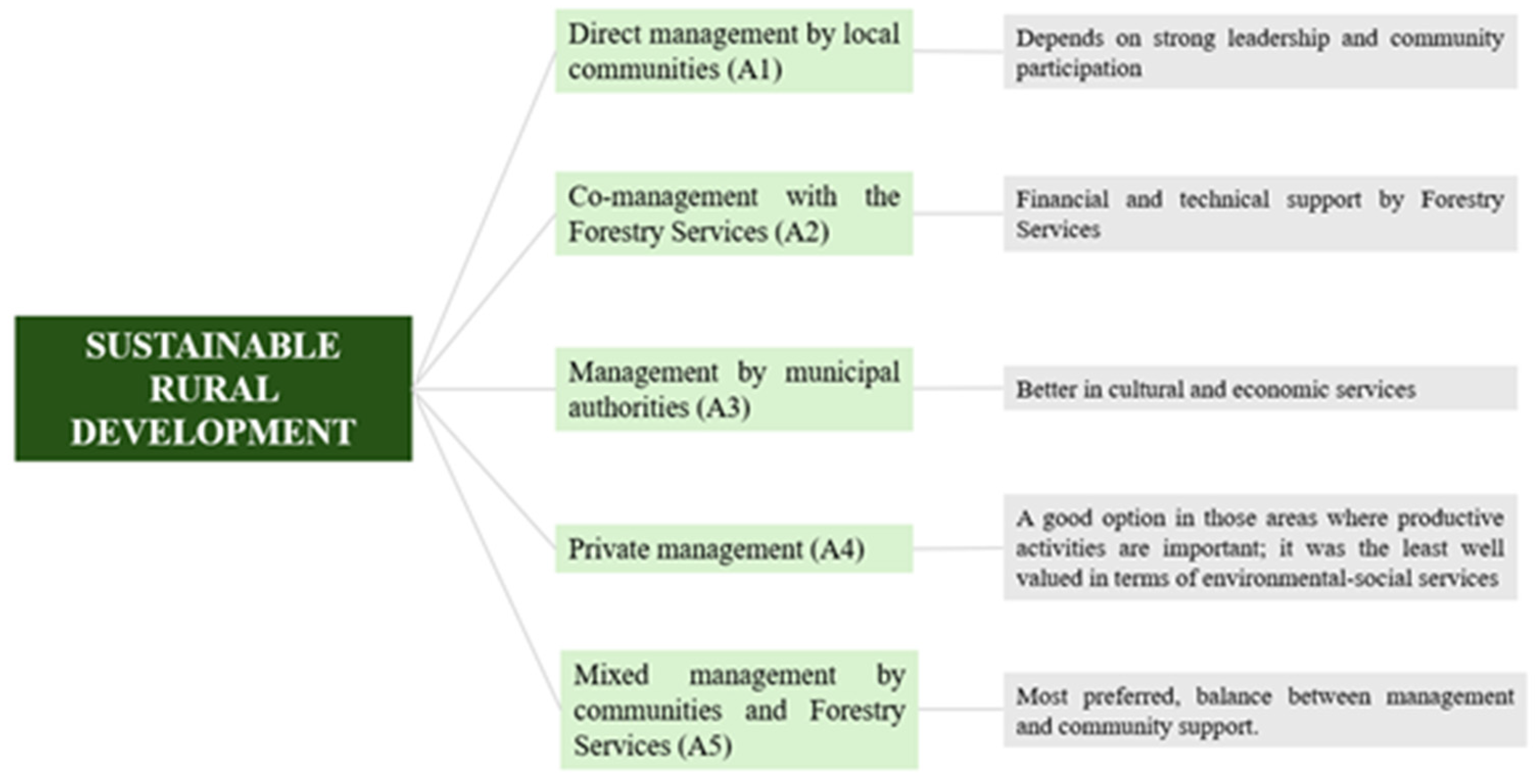

2.2. Different Alternatives for Managing Communal Land

The following five alternative of management were considered [

9,

13]: 1) direct management by local communities (A

1); 2) co-management with the Forestry Services (A

2); 3) management by municipal authorities (A

3); 4) private management (A

4); and 5) mixed management by communities and Forestry Services (A

5). The first two models of management are those that are now most used in communal lands.

To determine the criteria/services utilized to evaluate the different alternatives of management we reviewed previous studies that assessed the contribution of communal land management to rural development [

5,

10,

13] (

Table 1). The above-mentioned studies were carried out by interviewing members of five stakeholder groups: (1) members of the owner communities, (2) elected local authorities, (3) Forest Service technicians, (4) forestry experts, and (5) local development agents. The services and management alternatives were analysed using an

Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) a specific form of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) and pairwise comparison. In total, thirty-seven randomly sampled stakeholders were interviewed. Each stakeholder expressed their level of preference on a scale of 1 to 9, where a score of 1 indicates that the two services considered are equally important and a score of 9 indicates a total preference for one service over the other. To determine the relative importance of decision services, the composite scores (i.e., single variables or data point representing a combination of information from multiple variables) were calculated (

Table 2) [

17]. Later relative importance/preferences were analysed using pairwise reciprocal matrices [

18], as shown in

Table 3, where

‘bi’ is the importance of the decision service

‘i’.

3. Results

The individual comparison of ecosystem services according to the composite scores showed environmental ones are the most highly valued while social-cultural are the least valued (

Table 2). Regarding social services,

job creation was the most highly rated, highlighting the problem related to job creation in rural areas. The numerous economic and management services were rated very similar, with

diversification of income sources being the most highly valued.

Soil and water protection was the most important of environmental services. When analysed collectively,

job creation,

diversification of income sources, and

forestry production were highly valued by all stakeholders. However, environmental services particularly

soil and water protection, were rated the highest (

Table 2).

The final decision regarding communal land management identified the

mixed option, co-management with the Forestry Services (A

2), as the best for fulfilling the aim of rural sustainable development. By contrast, management by private entities was the least preferred option by the stakeholders. When analysed separately the management various alternatives, the opinion differed between groups, although three of the five stakeholders also chose mixed management. The stakeholders considered management by private entities a good option in those areas where productive activities are important, taking into account the efficiency of management. However, management by private entities was the least well valued in terms of environmental and social services. The low level of stakeholder participation in the communal land management is partly due to the co-management model;

‘selflessness is often an unacceptable waiver to decision making’ [

19,

20] (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The importance of biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services is often assumed in rural areas. This may explain the contrast between the opinion of stakeholders and urban thinking, according to which environmental services are at risk and, so it is mandatory to act to preserve them [

21,

22].

The

mixed management model was chosen as the most suitable to meet the objectives of rural development [

23,

24]. This type of management is like existing models; it is covered by current legislation and has the advantage of combining the financial and technical support of the Forestry Administration, as well as knowledge about land [

25]. Likewise, professional management of communal lands would enable proper reply to market demands and to the maintenance and conservation of ecosystem services [

26].

As previously mentioned, in those communal lands where the primary use is for wood and non-wood products supply,

private management was regarded as the optimal alternative [

27]. Private entities only rent parcels of communal land suitable for forest exploitation or with appropriate characteristics to locate, communication antennas, wind farms, quarries... Both in Portugal and Galicia, enterprises that rent parcels for forestry production are usually linked to paper-mill industries [

27].

Municipalities were rated better than private management in relation to economic and management services. Municipal authorities would ensure local jobs and are recognized for the interest in local development through promoting of the different social-cultural services, e.g. recreational use, tourism, hunting... In fact, numerous municipalities look at forests as key elements for sustainable rural development [

28,

29]. Finally, management by

local communities was well evaluated, however,

co-management with the Forest Services was not well evaluated because the scepticism of the communities about this alternative of management. The main problems of the co-management model in communal lands are delays in the silvicultural treatments and in the sale of wood. It results in unsuccessful management by the Forest Services [

2].

The mixed management option was also evaluated in relation to the set of ecosystem services and showed to be the management alternative preferred by stakeholders to achieve the goal of sustainable development [

20,

21]. This choice is like the co-management model already applied by the communities and the Forestry Services and has the advantage of providing an equal relationship between co-managers. As it involves professional management, this may be the most attractive option [

30,

31]. In the co-management model, the Forestry Services theoretically make decisions based on general interests, although these are often not discussed with stakeholders [

32,

33]. Some presidents/community leaders react to the lack of interest shown by other community members; so, the leadership being essential to support the sustainable management of communal lands [

34,

35] (

Figure 2).

5. Conclusions

Communal lands persist in times of economic liberalism as a source of wealth and as an example of the multifunctional/sustainable use of forests. This is a specific rural development model that makes it possible to obtain a benefit from natural resources, even those with little market value. Communities and the form of ownership, private but collective, are very attractive for municipalities and for new forms of entrepreneurship. However, there is no doubt that communal lands would prosper more effectively by being actively integrated into development projects that enhance community-associated strengths.

Communal lands endure both in Portugal and Galicia. The importance of these has decreased in number and economic benefit, because they no longer guarantee family incomes. However, some uses, such as timber exploitation, continue to be very profitable, especially in those communities where leaders are committed. The current alternatives of management of communal lands in the Galicia-North Portugal region are not generally considered reasonable by the stakeholders, particularly co-management with the Forestry Services −the most widely implemented model to date. The management by municipalities and the private entities was not considered acceptable by the stakeholders either. Of the five management alternatives studied, the stakeholder groups preferred a mixed model (currently non-existing), since it better shows both the features of communal lands and the current demands of rural areas.

The use of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and pairwise comparison, as a pedagogical and intuitive approach, was proper for the research objectives. The validity of the results obtained could be strengthened by greater participation of external agents with experience in managing development projects adapted to local conditions. However, professionals working in the field of local development projects are scarce in the study area.

The future of communal lands depends mainly on the valorisation of the natural resources they provide, making it necessary to consider their potential in the context of the areas where they are located. The situation in Galicia and northern Portugal is very similar, therefore, social and economic innovation is essential to achieve the goal of sustainable rural development in both areas.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the doctoral thesis “Restless Rural Areas: A contribution for the knowledge of the communal lands of northwest Iberian”, carried out by José A. Lopes PhD, ‘Rest in Peace’, under the guidance of Artur Cristóvão PhD and Ignacio J. Diaz-Maroto PhD. Ignacio J. Diaz-Maroto, co-author of the paper, via a fellowship give under the “OECD Co-operative Research Programme: Sustainable Agricultural and Food Systems”, acknowledgement the OECD for its invaluable support. Through which I am carrying out a research stay at the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague (CZU).

References

- Gómez-Vázquez, I.; Álvarez-Álvarez, P.; Marey-Pérez, M.F. Conflicts as enhancers or barriers to the management of privately owned common land: A method to analyze the role of conflicts on a regional basis. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marey-Pérez, M.; Díaz-Varela, E.; Calvo-González, A. Does higher owner participation increase conflicts over common land? An analysis of communal forests in Galicia (Spain). iForest - Biogeosciences For. 2015, 8, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, F. Os Baldios−Um panorama da região Norte. In: Seminário Desenvolvimento para os Baldios, Baldios para o desenvolvimento, IV Conferência Nacional dos Baldios, Secretariado dos Baldios de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, UTAD, Vila Real, 2001a.

- Baptista, F. Agriculturas e territórios. Oeiras, Celta Editora, 2001b.

- Bastida, M.; García, A.V.; Taín, M.V. A New Life for Forest Resources: The Commons as a Driver for Economic Sustainable Development—A Case Study from Galicia. Land 2021, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijas-Montero, M. The Assistance Work of Religious Orders in the South Galicia during the Modern Age. Stud. Monastica 2019, 61, 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Cristóvão, A.; Miranda, R. Organizações Locais e Desenvolvimento Rural. In: Cristóvão, A., Cabero Diéguez, V., Baptista, A. (Coords.), Dinâmicas Organizacionais e Desenvolvimento Local no Douro, UTAD, Vila Real, 2006.

- Skulska, I.; Montiel-Molina, C.; Germano, A.; Rego, F.C. Evolution of Portuguese community forests and their governance based on new institutional economics. Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, G. Community-based forest management institutions in the Galician communal forests: A new institutional approach. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 50, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, G.A.; Prabhu, R. Multiple criteria decision making approaches to assessing forest sustainability using criteria and indicators: A case study. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 131, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.S.; Mattor, K.M. Why Won’t They Come? Stakeholder Perspectives on Collaborative National Forest Planning by Participation Level. Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.; Tuler, S.; Webler, T. What Is a Good Public Participation Process? Five Perspectives from the Public. Environ. Manag. 2001, 27, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Videira, N. Participatory decision making for sustainable development—The use of mediated modelling techniques. Land Use Policy 2004, 23, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. Trial by space for a ‘radical rural’: Introducing alternative localities, representations and lives. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, G.; Martins, H. Multi-criteria decision analysis in natural resource management: A critical review of methods and new modelling paradigms. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 230, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso-Arribe, O.; Díaz-Maroto, I.J.; Vila-Lameiro, P.; Díaz-Maroto, M.C. Influence of the canopy in the natural regeneration of Quercus robur in NW Spain. Biologia 2014, 69, 1678–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D., Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 11.0 update (14th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2016.

- Banville, C.; Landry, M.; Martel, J.M.; Boulaire, C. A Stakeholder Approach to MCDA. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 1998, 14, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A. Analysis, participation and power: Justification and closure in participatory multi-criteria analysis. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Antunes, P.; Baptista, G.; Mateus, P.; Madruga, L. Stakeholder participation in the design of environmental policy mixes. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossel, H. Deriving indicators of sustainable development. Environ. Model. Assess. 1996, 1, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators. Measuring the immeasurable? Earthscan Publications Ltd., London, 1999.

- Cornforth, I.S. Selecting indicators for assessing sustainable land management. J. Environ. Manag. 1999, 56, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, V.K.; Ferguson, I.; Wild, I. Decision support system for the sustainable forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 128, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, E.W. Sustainable forest management for Galicia. For. Chron. 2008, 84, 530–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.; Ferreira, J.C.; Antunes, P. Green Infrastructure Planning Principles: An Integrated Literature Review. Land 2020, 9, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitsch, D.; Abruscato, S.; Lovrić, M.; Lindner, M.; Orazio, C.; Winkel, G. Close-to-nature forestry and intensive forestry—Two response patterns of forestry professionals towards climate change adaptation. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilova, G.; Khadka, C.; Vacik, H. Developing criteria and indicators for evaluating sustainable forest management: A case study in Kyrgyzstan. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 21, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H.; Schandl, H. Indicators of sustainable land use: Concepts for the analysis of society-nature interrelations and implications for sustainable development. Environ. Manag. Health 1999, 10, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Maroto, I.J.; Fernández-Parajes, J.; Vila-Lameiro, P.; Barcala-Pérez, E. Site index model for natural stands of rebollo oak (Quercus pyrenaica Willd.) in Galicia, NW Iberian Peninsula. Cienc. Florest. 2010, 20, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldea, J.; Martínez-Peña, F.; Romero, C.; Diaz-Balteiro, L. Participatory Goal Programming in Forest Management: An Application Integrating Several Ecosystem Services. Forests 2014, 5, 3352–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantiani, M. Forest planning and public participation: A possible methodological approach. iForest - Biogeosciences For. 2012, 5, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, A.; Saarinen, N.; Saarikoski, H.; Leskinen, L.A.; Hujala, T.; Tikkanen, J. Stakeholder perspectives about proper participation for Regional Forest Programs in Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, C. Cultural heritage, sustainable forest management and property in inland Spain. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 249, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).