1. Introduction

Tomato (

Solanum lycopersicum L.) is one of the most widely cultivated vegetable crops worldwide, with global production exceeding 180 million tons annually. This remarkable production level highlights the crop’s importance not only for global food security but also for the economic stability of agricultural systems [

1,

2,

3]. Beyond its economic value, tomato is a nutritionally significant crop, providing essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that contribute to human health, improve dietary quality, and play roles in preventing chronic diseases [

4,

5]. Despite these benefits, tomato production is highly vulnerable to a broad spectrum of pathogens, including fungi, bacteria, and viruses, which can drastically reduce yields and compromise fruit quality. Managing these pathogens is therefore critical to maintaining both productivity and the nutritional value of the crop [

6,

7]

The global expansion of greenhouse production has enabled year-round cultivation of tomatoes under controlled environmental conditions. This approach allows farmers to optimize growth factors such as temperature, light, and humidity, improving productivity and efficiency. However, greenhouse environments are often conducive to the rapid development of pathogens because they combine high humidity, moderate temperatures, and dense plant populations. These conditions can favor the rapid spread of diseases, and even minor infections can quickly escalate into severe outbreaks, leading to significant economic losses. Traditional disease management strategies have relied heavily on chemical pesticides, which, although effective in the short term, raise serious concerns regarding environmental contamination, human health risks, and the development of pathogen resistance. Such limitations emphasize the need for more sustainable and ecologically safe approaches to disease control in tomato production systems [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Foliar-applied elicitors have emerged as a promising alternative for enhancing plant immunity and reducing disease pressure. Elicitors, which may be derived from biotic or abiotic sources, stimulate a wide range of plant defense mechanisms, including the production of pathogenesis-related proteins, phytoalexins, and antioxidant enzymes. They can also strengthen structural barriers such as cell walls, making plants less susceptible to pathogen penetration and colonization [

11,

12,

13]. By activating these defense responses, elicitors provide broad-spectrum resistance against diverse pathogens while minimizing the negative effects associated with chemical control methods. These responses are often systemic, enhancing overall plant resilience and offering an environmentally friendly approach to disease management [

14,

15].

Research has demonstrated that various elicitors can effectively enhance tomato resistance to specific pathogens. For instance, polysaccharide- and oligosaccharide-based elicitors have been shown to reduce disease severity caused by

Oidium neolycopersici and other foliar pathogens through the induction of systemic acquired resistance [

3,

16,

17]. Similarly, elicitors such as salicylic acid, β-glucans, and microbial compounds like acetoin and Hrip1 prime plants to respond more efficiently to pathogen attacks, reducing symptom development and limiting pathogen proliferation. These treatments also influence key hormonal pathways, including jasmonic acid and salicylic acid signaling, which are critical for coordinating defense responses against multiple pathogen types and ensuring timely activation of protective mechanisms [

14,

18,

19,

20].

The integration of elicitor applications with molecular diagnostic techniques enhances disease management further by enabling precise pathogen detection and monitoring. Molecular tools such as PCR amplification of conserved genetic regions, including 16S rDNA for bacteria, ITS or TEF1α for fungi, and degenerate primers for viruses, allow accurate identification of pathogens and evaluation of elicitor effectiveness. This integration supports proactive, evidence-based disease management strategies that optimize crop health, reduce losses, and minimize unnecessary chemical inputs [

21,

22,

41].

Despite the demonstrated benefits of elicitors, there remain significant knowledge gaps regarding their comparative effectiveness, optimal application timing and frequency, and specific impacts on disease incidence, severity, and pathogen diversity. Filling these gaps is critical for translating elicitor research into practical, scalable solutions for greenhouse tomato production. In this study, we evaluated the effects of three foliar-applied elicitors, Activane®, Micobiol®, and Stemicol®, applied every fifteen days, on disease incidence and severity in two tomato varieties grown under greenhouse conditions. Symptomatic tissues were collected for molecular identification of causal agents, and the relationship between pathogen presence and disease severity was assessed. The results provide insights into sustainable crop protection strategies and support the broader adoption of elicitor-based interventions to improve tomato health and productivity in greenhouse systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Plant Material

Experiments were conducted under greenhouse conditions at the Israelita greenhouse of the Protected Agriculture Center (CAP), Faculty of Agronomy, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL), located in Gral. Escobedo, Nuevo León, Mexico, during the summer 2019 to spring 2020 cycle. The greenhouse covered 1,000 m2 with a gothic-style structure, sidewall height of 4.6 m, and maximum height of 7 m, providing medium-low technology environmental control suitable for tomato growth and disease evaluation. Two tomato (S. lycopersicum L.) varieties, Saladette (Potosí) and Bola (Arameo), were used.

2.2. Experimental Design and Elicitor Treatments

A completely randomized design was employed with four treatments and four replications per treatment. Each experimental unit consisted of eight plants, totaling 128 plants per variety. Treatments included: T1, Control (no elicitor); T2, Activane

® (1.8 g L⁻¹); T3, Micobiol

® (3 mL L⁻¹); and T4, Stemicol

® (2.5 g L⁻¹). Foliar applications were administered every 15 days according to manufacturer recommendations (

Table 1). For foliar application, elicitors were dissolved in clean water and the solution adjusted to an appropriate pH (6.0–6.5) to optimize uptake. A non-ionic surfactant was added at 0.05 percent (v/v) to improve leaf surface coverage and adherence. Solutions were freshly prepared prior to each application and applied uniformly until runoff using a hand-held sprayer.

2.3. Disease Incidence and Severity Assessment

Disease incidence (%) was calculated as the proportion of symptomatic plants within each experimental unit. Disease severity was visually evaluated using a 0–5 scale based on leaf area affected, where 0 indicated healthy plants and 5 indicated complete leaf damage or wilting [

23,

24] (

Table 2). Evaluations were conducted at vegetative, flowering, and fruiting stages.

2.4. Sample Collection and Preparation

Samples of symptomatic tomato plants, including leaves and fruits, were collected from greenhouse-grown plants. For bacterial and fungal isolation, tissues showing necrotic or chlorotic lesions were selected. For viral detection, approximately 2 g of the youngest symptomatic apical leaves showing interveinal chlorosis, mottling, or deformation were sampled. All plant materials were transported on ice to the Phytopathology Laboratory for further processing.

2.5. Isolation and Identification of Phytopathogenic Bacteria

Tissue fragments (~1 cm) from symptomatic samples were surface-sterilized in 10% Cloralex® for 2 minutes, rinsed with sterile distilled water, and transferred to potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates (3–4 pieces per dish). Plates were incubated at 24–28°C for 24–48 hours until colonies emerged. Morphological characteristics were examined under both stereoscopic and compound microscopes. Bacterial isolates suspected to be Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas syringae, and Xanthomonas campestris were confirmed by PCR amplification of the 16S rDNA gene using primers 8F (5’-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3’) and 1492R (5’-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3’). The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 48°C for 50 s, and 72°C for 80 s; followed by a final extension at 74°C for 4 min. Amplicons were visualized on 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/μL) using a 100 bp DNA ladder. The expected product size was ~1484 bp.

2.6. Isolation and Identification of Phytopathogenic Fungi

Fungal pathogens were isolated from necrotic lesions by plating surface-sterilized tissue on PDA and incubating at 25°C for 5–7 days. Emerging colonies were examined morphologically, and microscopic features were compared with published descriptions. Target fungi included Oidiopsis taurica, Alternaria solani, Fusarium oxysporum, and Cladosporium fulvum. Molecular confirmation was performed by amplifying the ITS region of rDNA using primers ITS1 (5’-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G-3’) and ITS4 (5’-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3’). PCR conditions included initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 60 s; followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels and visualized under UV illumination.

2.7. Extraction of Viral Nucleic Acids (DNA and RNA)

Viral DNA was extracted from symptomatic tomato leaves using the DNAzol method according to manufacturer protocols. For RNA viruses or to exclude mixed viral infections, total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of symptomatic leaf tissue using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, USA). RNA integrity was assessed on 1% agarose gels, and concentrations were measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from RNA templates using random hexamers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA). Extracted nucleic acids were subsequently used for PCR and RT-PCR assays.

2.8. Detection of Viruses by Generic Begomovirus PCR

Detection of begomoviruses including

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), and

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus, Tomato mottle virus (ToMoV) was performed using degenerate primers prV324/prC889 (prC-889: 5’-GGR TTD GAR GCA TGH GTA CAT G-3’ and prV-324: 5’-GCC YAT RTA YAG RAA GCC MAG-3’). The PCR program included initial denaturation at 92°C for 1 min; 35 cycles of 92°C for 60 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 74°C for 30 s; followed by a final extension at 74°C for 4 min. Amplified products were separated on 1% agarose gels at 60 V for 5 min, then 100 V for 40 min, visualized under UV light, and sequenced for confirmation [

25].

2.9. Sequencing and Data Analysis

PCR products from bacteria (16S rDNA), fungi (ITS region), and viruses (begomovirus fragments) were purified using a commercial PCR clean-up kit (Qiagen, USA) and sequenced at Eurofins Genomics using an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer. Raw chromatograms were trimmed and assembled using BioEdit and MEGA software. Consensus sequences were compared against reference sequences in the NCBI GenBank database using BLASTn. Fungal ITS sequences were additionally verified with the UNITE fungal ITS database. Pathogen identity was confirmed when sequences shared ≥97% similarity with reference strains. A correlation heatmap was then generated to show the relative contributions (%) of nine pathogens to disease severity under four treatments (Control, Activane, Micobiol, Stemicol). Pairwise correlation coefficients (e.g. Pearson’s r) between pathogen severity and treatment-group metrics were computed, then visualized in the heatmap to highlight which pathogens contributed most strongly under each treatment.

3. Results

3.1. Disease Incidence and Severity Across Treatments

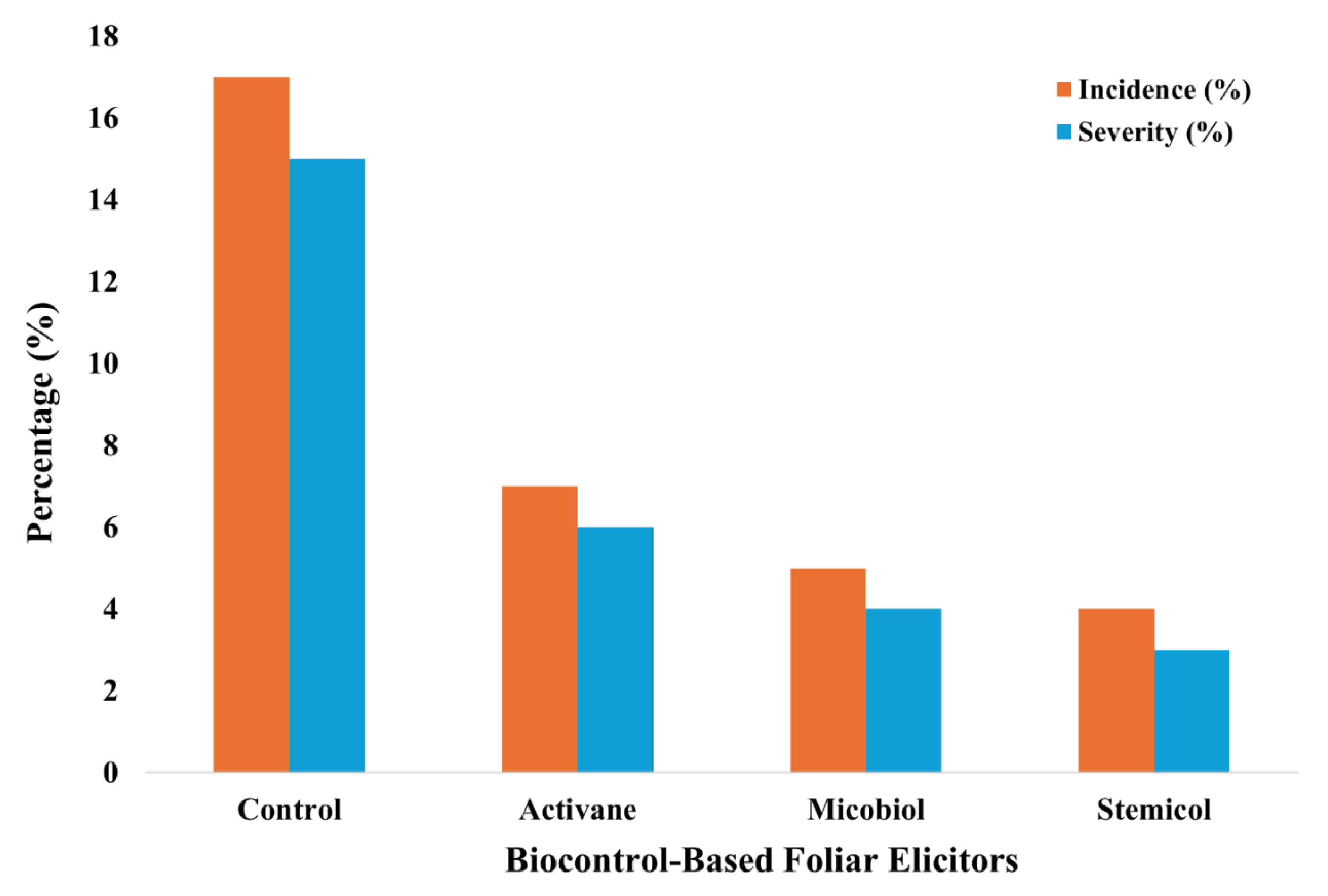

The application of elicitors consistently reduced the presence and severity of disease symptoms in both tomato varieties throughout the crop cycle. Overall, elicitor treatments exhibited lower values of incidence and severity compared with the control. Micobiol and Stemicol produced the most positive effects on both disease incidence and severity. The average disease incidence and severity in tomato plants varied significantly among treatments (

Figure 1). The control group exhibited the highest disease incidence and severity, with values of approximately 17% and 15%, respectively. In contrast, foliar applications of Activane, Micobiol, and Stemicol markedly reduced both disease incidence and severity compared with the untreated control. Specifically, Activane reduced incidence to 7% and severity to 6%, while Micobiol and Stemicol further lowered incidence to 5% and 4%, and severity to 4% and 3%, respectively.

3.2. Cumulative Survival of Tomato Plants

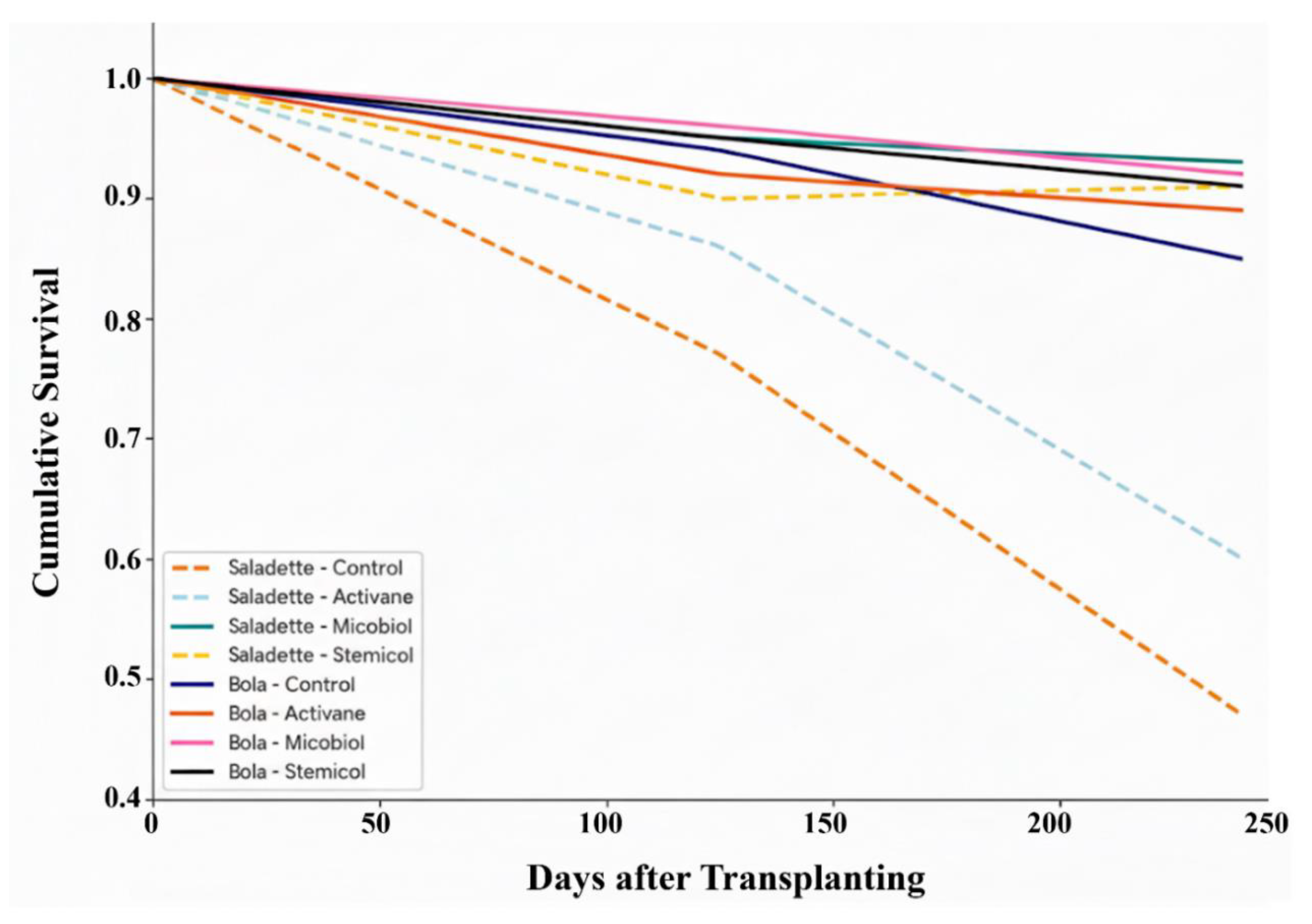

The cumulative survival of tomato plants varied significantly across varieties and treatments over the 240-day period following transplanting (

Figure 2). For both Saladette and Bola varieties, untreated control plants exhibited the lowest survival rates, with the Bola control showing the most pronounced decline, reaching approximately 47% survival by the end of the experiment. In contrast, all elicitor treatments improved plant survival relative to the controls.

Micobiol and Stemicol demonstrated the greatest efficacy in enhancing tomato plant survival across both cultivars. In the Saladette variety, Micobiol treatment resulted in approximately 94% survival, closely followed by Stemicol at 92%. Activane also improved survival, though to a lesser extent (~90%). A similar trend was observed in the Bola variety, where Micobiol and Stemicol maintained survival rates above 90%, whereas Activane-treated plants exhibited intermediate survival (~85%).

3.3. Pathogen Identification and Severity

Pathogen detection in tomato plants revealed the presence of multiple bacterial, fungal, and viral species across treatments (

Table 3). Among bacteria,

Enterobacter cloacae (16S rDNA 97.8%) was primarily isolated from control plants and at lower frequency in T2, with pathogenicity confirmed by re-isolation and inoculation tests.

Pseudomonas syringae pv.

tomato (16S rDNA 98.5%) and

Xanthomonas euvesicatoria (16S rDNA 98.2%) were associated with necrotic leaf lesions and higher severity in untreated Bola plants. Fungal pathogens included

Oidiopsis taurica, which exhibited higher severity in control plants,

Alternaria solani confirmed by ITS and TEF1α sequencing and linked to early blight lesions,

Fusarium oxysporum detected in vascular tissues and rhizosphere and correlated with increased mortality, and

Botrytis cinerea present on fruits and senescent leaves under high humidity. Viral pathogens detected in both varieties included

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV, 99.6% identity) and

Tomato mottle virus (ToMoV), which were associated with leaf deformation and mottling. All pathogen identities were confirmed through sequencing and comparison with GenBank references, showing 97–99% similarity (

Table 3).

3.4. Pathogen–Elicitor Interaction

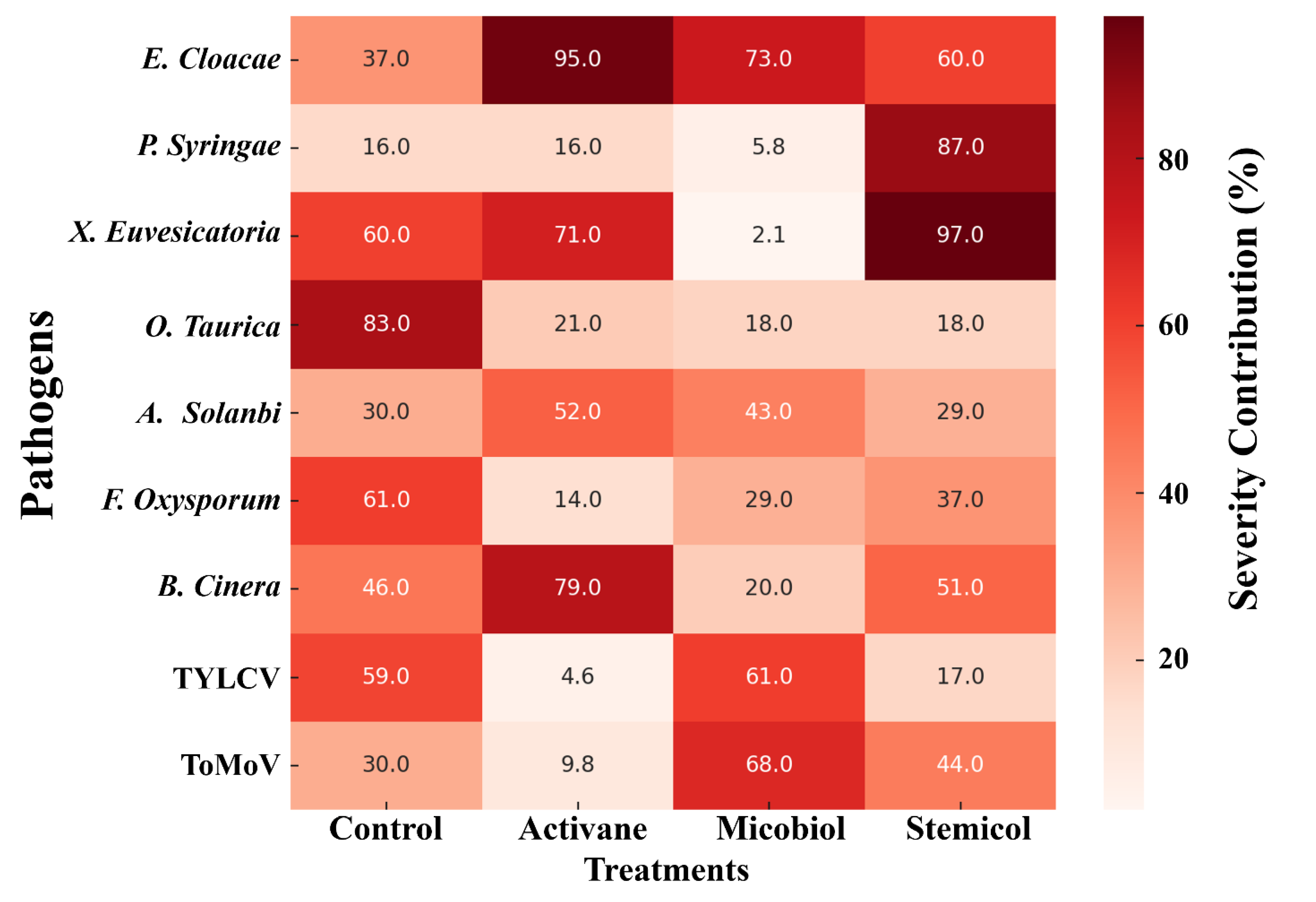

The correlation heatmap (

Figure 3) illustrates variation in disease severity contributions (%) across nine pathogens under four treatments: Control, Activane, Micobiol, and Stemicol. Untreated control plants showed the highest severity from

Oidiopsis taurica (83%) and

Fusarium oxysporum (61%), highlighting the susceptibility of plants in the absence of elicitors. Treatments altered severity patterns unevenly; for example,

Enterobacter cloacae severity remained high under Activane (95%), while

Xanthomonas euvesicatoria exhibited maximum severity under Stemicol (97%).

Stemicol and Micobiol reduced severity of several pathogens, including O. taurica (18–21%) and TYLCV (17–61%), indicating their potential role in suppressing foliar diseases. Conversely, Botrytis cinerea showed elevated severity under Activane (79%), and E. cloacae persisted at high levels under multiple treatments, suggesting incomplete pathogen suppression.

3.5. Frequency and Severity by Pathogen Type

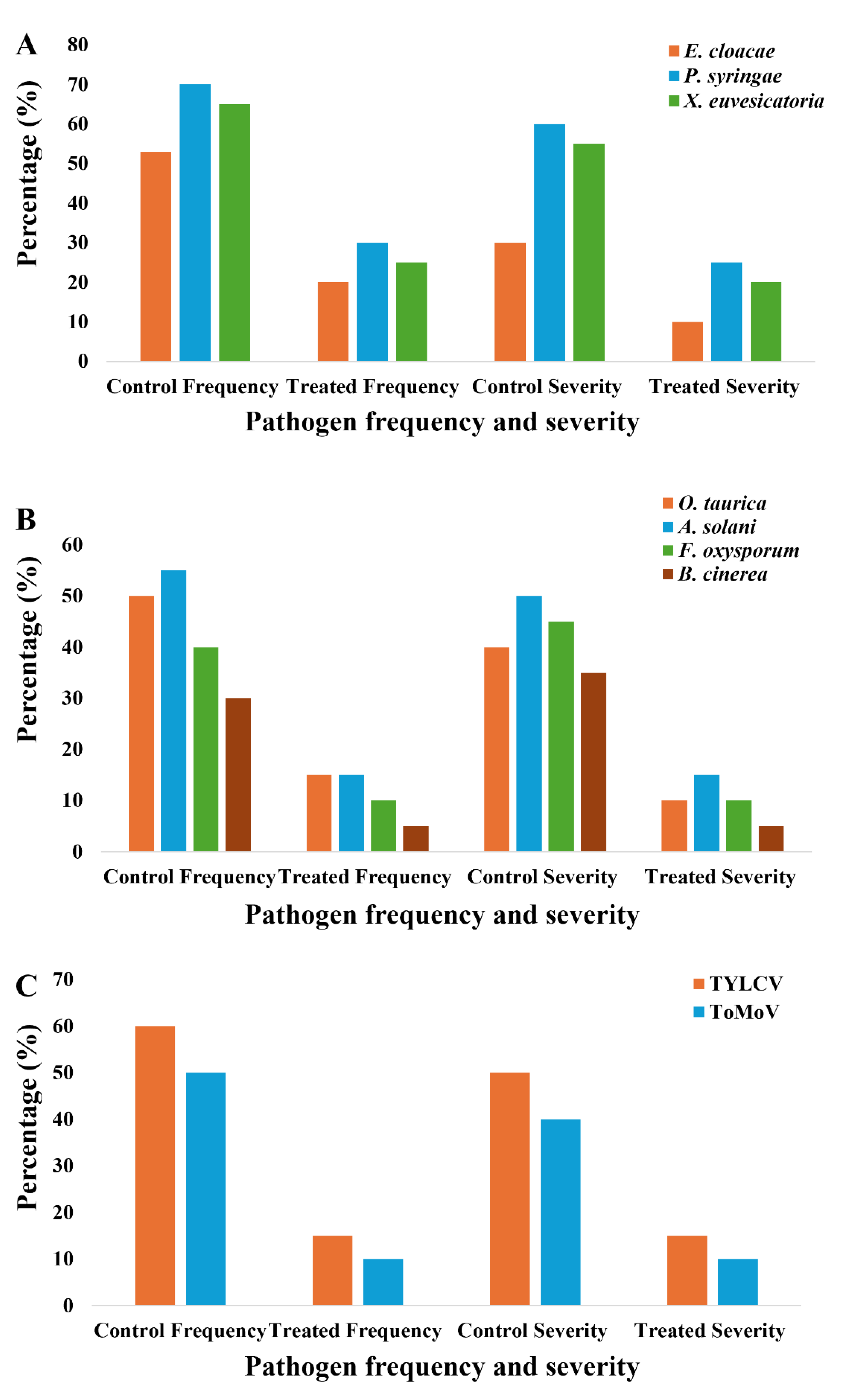

Pathogen detection revealed marked differences in pathogen incidence and disease severity between control and elicitor-treated plants (

Figure 4). In untreated controls, bacterial pathogens (

E. cloacae,

P. syringae pv.

tomato, and

X. euvesicatoria) occurred at high frequencies (50–70%) with moderate to high severities (30–55%), whereas elicitor treatments substantially reduced both frequency (10–30%) and severity (5–25%), with the strongest suppression observed for

E. cloacae and

P. syringae. Fungal pathogens presented the greatest overall burden, with

A. solani and

O. taurica reaching frequencies of 50–55% and severities of 40–50%, while

F. oxysporum and

B. cinerea were also prevalent, contributing to vascular wilt and fruit or leaf rots. Elicitor treatment consistently lowered fungal incidence (10–15%) and severity (5–15%), with

F. oxysporum showing the largest decline. Viral pathogens (TYLCV and ToMoV) were detected at high frequencies (50–60%) in controls, but elicitor application reduced both frequency and severity to 10–15%.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that foliar elicitors significantly reduced disease incidence, severity, and plant mortality while enhancing survival in both tomato varieties. These findings highlight the efficacy of biocontrol-based foliar treatments in mitigating tomato disease development through activation of plant defense mechanisms. The consistent improvement in plant health across treatments supports the growing body of evidence that elicitor-based applications can effectively enhance innate immunity and resilience in crop plants.

The observed reductions in disease metrics suggest that elicitor treatments activated both systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR), the two major defense pathways that underlie plant immune responses. SAR is commonly mediated by salicylic acid (SA) and leads to the accumulation of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, whereas ISR is triggered by jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signaling, leading to enhanced activity of peroxidases, phenylalanine ammonia lyase, and other defense-related enzymes [

9,

26]. These pathways confer broad-spectrum resistance by priming the plant to respond more rapidly and robustly upon pathogen attack. Elicitors such as chitosan, β-glucans, and microbial-derived compounds are known to mimic pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), thereby triggering these defense cascades [

27,

28].

Varietal differences observed between Saladette and Bola tomatoes further demonstrate the role of host genotype in modulating elicitor responsiveness. Saladette plants displayed higher survival and lower disease severity, which may reflect a stronger basal immunity or greater sensitivity to defense priming signals. Similar genotype-dependent variations in elicitor response have been reported in other crops, where differences in receptor sensitivity, defense gene expression, and secondary metabolite accumulation contributed to variable protection levels [

29,

30]. Among the tested products, Micobiol and Stemicol were particularly effective, possibly due to their combined effects on ISR activation, antioxidant enhancement, and suppression of oxidative stress during infection [

31].

Pathogen identification revealed a diverse complex of bacterial, fungal, and viral agents contributing to disease in tomato plants. The predominance of

Fusarium oxysporum and

Oidiopsis taurica in untreated plants underscores their importance as major yield-limiting pathogens under field conditions. These pathogens are known to exploit weakened or unprimed hosts, whereas elicitor treatments appeared to disrupt their infection processes, likely through reinforcement of cell walls, enhanced production of phenolic compounds, and increased activity of defensive enzymes [

32,

33,

34]. Such multifaceted defense responses are essential for managing soilborne and foliar pathogens simultaneously, especially under polyetiological conditions typical of open-field tomato cultivation. The pathogen-elicitor interaction patterns revealed selective suppression across pathogens, supporting the concept of defense priming [

35,

36]. Priming does not necessarily eliminate pathogen presence but prepares plants to contain infection more effectively, reducing both colonization and symptom expression. The incomplete suppression of certain bacterial species, such as

Enterobacter cloacae, suggests that elicitor effectiveness may vary with pathogen lifestyle, tissue specificity, or interference with host signaling pathways [

37,

38]. Opportunistic pathogens that exploit weakened tissues or persist epiphytically may be less affected by elicitor-induced responses, highlighting the need to integrate elicitors with other management strategies such as beneficial microbes or soil amendments.

Interestingly, trade-offs in defense allocation were evident, such as the elevated

Pseudomonas syringae incidence under Stemicol treatments. This reflects the antagonistic crosstalk between SA- and JA/ET-mediated defense pathways, where activation of one pathway can transiently suppress the other [

39,

40]. Such cross-regulation, although evolutionarily conserved, can lead to pathogen-specific vulnerabilities depending on the elicitor formulation and timing of application. Understanding these interactions is crucial for optimizing elicitor use in integrated disease management programs. Beyond disease suppression, elicitor-induced resistance may confer additional physiological benefits. Enhanced photosynthetic performance, increased root vigor, and improved nutrient assimilation have been reported as secondary effects of elicitor use, contributing to overall plant vigor and yield stability under stress [

27,

29]. In this context, the survival advantages observed in elicitor-treated plants may reflect not only reduced disease pressure but also improved systemic tolerance to environmental fluctuations and latent pathogen stress.

5. Conclusions

The application of foliar elicitors, specifically Activane®, Micobiol®, and Stemicol®, significantly reduced disease incidence and severity in Saladette and Bola tomato varieties under greenhouse conditions. Among the treatments, Micobiol® and Stemicol® were the most effective, consistently lowering the frequency and severity of bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens while enhancing cumulative plant survival, reaching up to 94% in Saladette and 92% in Bola. Pathogen identification revealed a diverse range of bacterial, fungal, and viral species, highlighting the complexity of disease dynamics in tomato production. Correlation analyses indicated that elicitor-induced priming selectively enhances plant defenses, with differential suppression of specific pathogens. These findings demonstrate that biocontrol-based foliar elicitors are effective tools for integrated disease management, offering a sustainable alternative to chemical pesticides. Incorporating such treatments into tomato production systems can improve plant health, promote resilience and productivity, and contribute to environmentally friendly crop protection strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.O.Z. A.K.C. and E.O.S.; Methodology, E.O.S. H.L.S and R.E.A.; Formal Analysis, A.K.C. I.D. and J.A.J.; Investigation, A.K.C. M.J.F. A.A. and M.C.O.Z.; Writing Original Draft, A.K.C. and I.D.; Review and Editing, M.C.O.Z. A.K.C. P.T.J. and I.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the support provided by the National Council for the Humanities, Sciences, and Technologies (CONAHCYT); the Faculty of Agronomy of the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon (FAUANL); and Lida de México SA DE CV.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, W.; Liu, K.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; El-Mogy, M.M.; Tian, S.; Chen, T. Solanum Lycopersicum, a Model Plant for the Studies in Developmental Biology, Stress Biology and Food Science. Foods 2022, 11, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyngaard, S.R.; Kissinger, M. Tomatoes from the Desert: Environmental Footprints and Sustainability Potential in a Changing World. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 994920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohoursoleimani, R.; Aeini, M.; Ghodoum Parizipour, M.H. Effects of Abiotic and Biotic Elicitors on Tomato Resistance to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanță, L.C.; Fărcaş, A.C. Exploring the Efficacy and Feasibility of Tomato By-Products in Advancing Food Industry Applications. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Sina, A.A.I.; Khandker, S.S.; Neesa, L.; Tanvir, E.M.; Kabir, A.; Khalil, M.I.; Gan, S.H. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds in Tomatoes and Their Impact on Human Health and Disease: A Review. Foods 2020, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Buenrostro, E.; Rangel-Vargas, E.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Velázquez-Jiménez, R.; Torres-Vitela, M.R.; Castro-Rosas, J. Effective Use of Microbial and Plant-Based Alternatives in Tomato Pathogen Control: A Comprehensive Review. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertical Transmission of Tomato Viruses. In Advances in Virus Research; Elsevier, 2025; Vol. 123, pp. 105–168 ISBN 978-0-443-34493-0.

- Izuafa, A.; Chimbekujwo, K.I.; Raji, R.O.; Oyewole, O.A.; Oyewale, R.O.; Abioye, O.P. Application of Nanoparticles for Targeted Management of Pests, Pathogens and Disease of Plants. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 13, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Reddy, M.S.; Ryu, C.-M.; McInroy, J.A.; Wilson, M.; Kloepper, J.W. Induced Systemic Protection Against Tomato Late Blight Elicited by Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria. Phytopathology® 2002, 92, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, S.; Calise, F.; Kant, K.; Ahamed, M.S.; Copertaro, B.; Najafi, G.; Zhang, X.; Aghaei, M.; Shamshiri, R.R. A Review on Opportunities for Implementation of Solar Energy Technologies in Agricultural Greenhouses. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektas, Y.; Eulgem, T. Synthetic Plant Defense Elicitors. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D. Elicitation: A Tool for Enriching the Bioactive Composition of Foods. Molecules 2014, 19, 13541–13563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowtham, H.G.; Murali, M.; Shilpa, N.; Amruthesh, K.N.; Gafur, A.; Antonius, S.; Sayyed, R.Z. Harnessing Abiotic Elicitors to Bolster Plant’s Resistance against Bacterial Pathogens. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalupowicz, L.; Manulis-Sasson, S.; Barash, I.; Elad, Y.; Rav-David, D.; Brandl, M.T. Effect of Plant Systemic Resistance Elicited by Biological and Chemical Inducers on the Colonization of the Lettuce and Basil Leaf Apoplast by Salmonella Enterica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e01151–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Samota, M.K.; Choudhary, M.; Choudhary, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Thakur, J. How Do Plants Defend Themselves against Pathogens-Biochemical Mechanisms and Genetic Interventions. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnizo, N.; Oliveros, D.; Murillo-Arango, W.; Bermúdez-Cardona, M.B. Oligosaccharides: Defense Inducers, Their Recognition in Plants, Commercial Uses and Perspectives. Molecules 2020, 25, 5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Xiao, Y.; Yin, H.; Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Oligosaccharide Elicitors in Plant Immunity: Molecular Mechanisms and Disease Resistance Strategies. Plant Commun. 2025, 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, E.A.; Jayaraman, J.; Templeton, M.D.; Rikkerink, E.H.A. Comparison of the Pathway Structures Influencing the Temporal Response of Salicylate and Jasmonate Defence Hormones in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 952301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Ibanez, S.; Solano, R. Nuclear Jasmonate and Salicylate Signaling and Crosstalk in Defense against Pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrappa, T.; Biedrzycki, M.L.; Kunjeti, S.G.; Donofrio, N.M.; Czymmek, K.J.; Paul W., P.; Bais, H.P. The Rhizobacterial Elicitor Acetoin Induces Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2010, 3, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Jin, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y. Advances in the Application of Molecular Diagnostic Techniques for the Detection of Infectious Disease Pathogens (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Karaoz, U.; Volegova, M.; MacKichan, J.; Kato-Maeda, M.; Miller, S.; Nadarajan, R.; Brodie, E.L.; Lynch, S.V. Use of 16S rRNA Gene for Identification of a Broad Range of Clinically Relevant Bacterial Pathogens. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0117617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Moreno, L.; Niño Mendoza, G.H.; Mendoza Celedón, B.; León Galván, Ma.F.; Robles Hernández, L.; González Franco, A.C. Pathogenic Viruses Incidence, Severity and Detection in Lettuce, in the State of Queretaro, Mexico. Acta Univ. 2016, 26, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Enciso, E.L.; Robledo Olivo, A.; Benavides Mendoza, A.; Solís Gaona, S.; González Morales, S. Efecto de Elicitores de Origen Natural Sobre Plantas de Tomate Sometidas a Estrés Biótico. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, D.T.; Güerere, P.; Geraud-Pouey, F.; Romay, G.; Santana, M.A.; Bastidas, L. Transmisión experimental de Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) por Bemisia tabaci (Aleyrodidae) a solanáceas. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2009, 35, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, D.K.; Prakash, A.; Johri, B.N. Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) in Plants: Mechanism of Action. Indian J. Microbiol. 2007, 47, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pršić, J.; Ongena, M. Elicitors of Plant Immunity Triggered by Beneficial Bacteria. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 594530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Fernandez, M.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Arnao, M.B.; Cabrera-Escribano, F.; Nueda, M.J.; Gunsé, B.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V. Chitosan Induces Plant Hormones and Defenses in Tomato Root Exudates. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 572087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.R.; Ratsep, J.; Havis, N.D. Controlling Crop Diseases Using Induced Resistance: Challenges for the Future. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthee, D.R.; Pandey, A.; Paudel, R. Multiple Foliar Fungal Disease Management in Tomatoes: A Comprehensive Approach. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Sohal, B.S. Role of Elicitors in Inducing Resistance in Plants against Pathogen Infection: A Review. ISRN Biochem. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmey, T.; Tominello-Ramirez, C.S.; Brune, C.; Stam, R. Alternaria Diseases on Potato and Tomato. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvucci, A.; Aegerter, B.J.; Miyao, E.M.; Stergiopoulos, I. First Report of Powdery Mildew Caused by Oidium Lycopersici in Field-Grown Tomatoes in California. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1497–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarven, Most. S.; Hao, Q.; Deng, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, X. Biological Control of Tomato Gray Mold Caused by Botrytis Cinerea with the Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium Anisopliae. Pathogens 2020, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Baccelli, I.; Luna, E.; Flors, V. Defense Priming: An Adaptive Part of Induced Resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G.J.M.; Flors, V.; García-Agustín, P.; Jakab, G.; Mauch, F.; Newman, M.-A.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Poinssot, B.; Pozo, M.J.; et al. Priming: Getting Ready for Battle. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2006, 19, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van Der Does, D.; Zamioudis, C.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Hormonal Modulation of Plant Immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012, 28, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Doornbos, R.F.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Induced Systemic Resistance and the Rhizosphere Microbiome. Plant Pathol. J. 2013, 29, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, J.; Lu, X.; Zhou, C. Development of Plant Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Rhizobacteria: Recognition, Initiation, Elicitation and Regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 952397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Song, S. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Signaling by Proteins Activating and Repressing Transciption. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, erw443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cham, A.K.; Ojeda Zacarías, M.D.C.; Lozoya Saldaña, H.; Saenz, E.O.; Alvarado Gomez, O.G. Effects of Elicitors on the Growth, Productivity and Health of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under Greenhouse Conditions. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 24, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).