Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Experimental Design and Sources of Trichoderma, Meloidogyne javanica and Fusarium oxysporum Isolates

2.3. Experimental Procedures for the Laboratory Experiments

2.3.1. Evaluating the Degree of Antagonism by Trichoderma Isolates in Suppressing Fusarium oxysporum Growth

2.3.2. Evaluating the efficacy of Trichoderma isolates in suppressing RKN egg hatching

2.3.3. Evaluating the Efficacy of Trichoderma Isolates in Causing Mortality in RKN Juveniles

2.4. Field Evaluation of the Efficacy of Trichoderma Isolates in Controlling FW-RKN Disease Complex and Impact on Plant Growth

2.4.1. Experimental Design

2.4.2. Experimental Procedure

2.4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identity of the Trichoderma Isolates Used in this Study

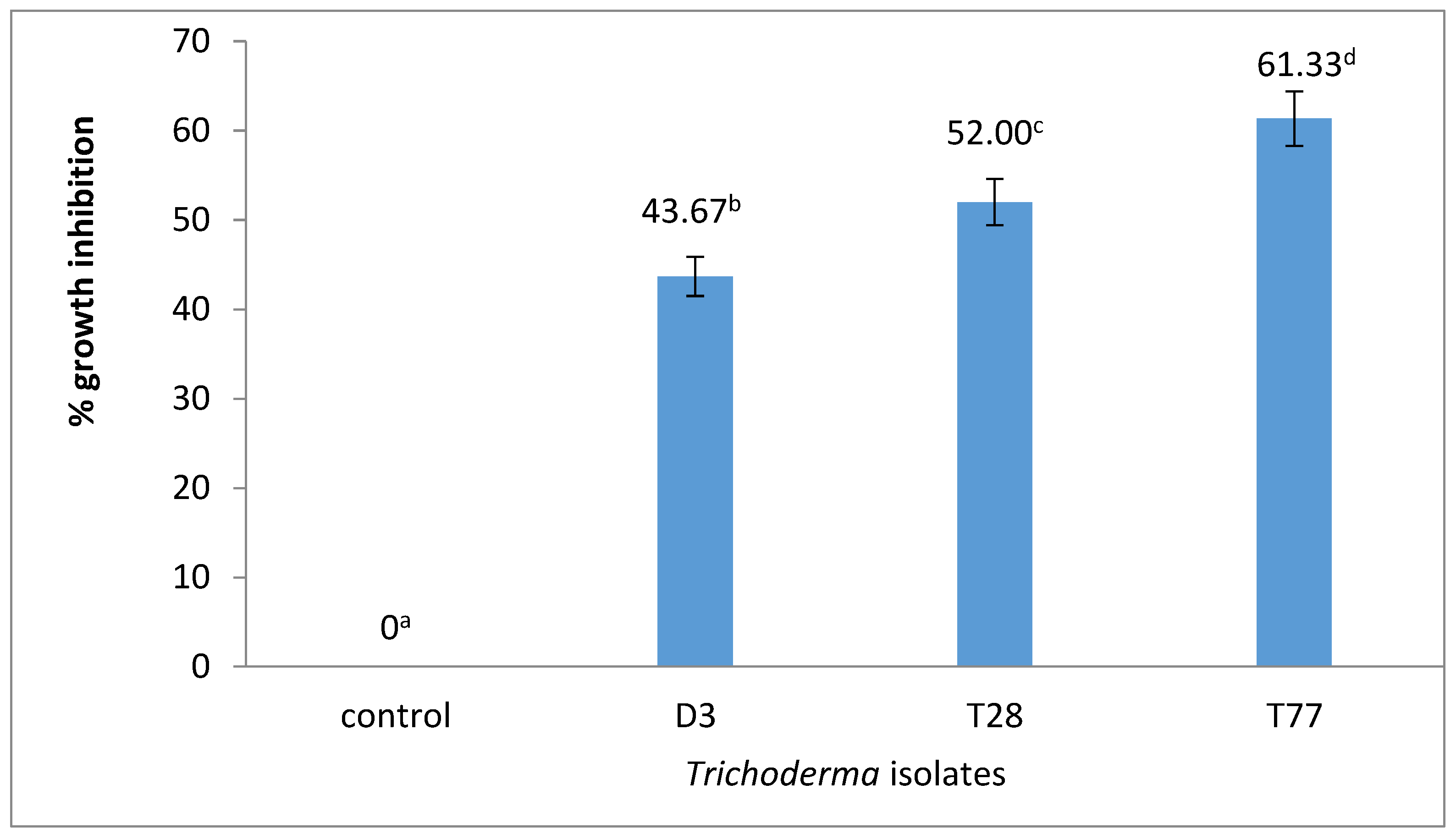

3.2. Antagonistic Effects of Trichoderma Isolates Against F. oxysporum

3.3. Effect of Isolate Treatments on M. javanica Egg-Hatching

3.4. Effect of Trichoderma Isolates on Mortality of M. javanica Juveniles

3.5. Effects of Trichoderma Isolates on Fusarium Wilt and RKN Disease Prevalence in the Field

3.5.1. Effects on Fusarium wilt Disease Incidence and Severity

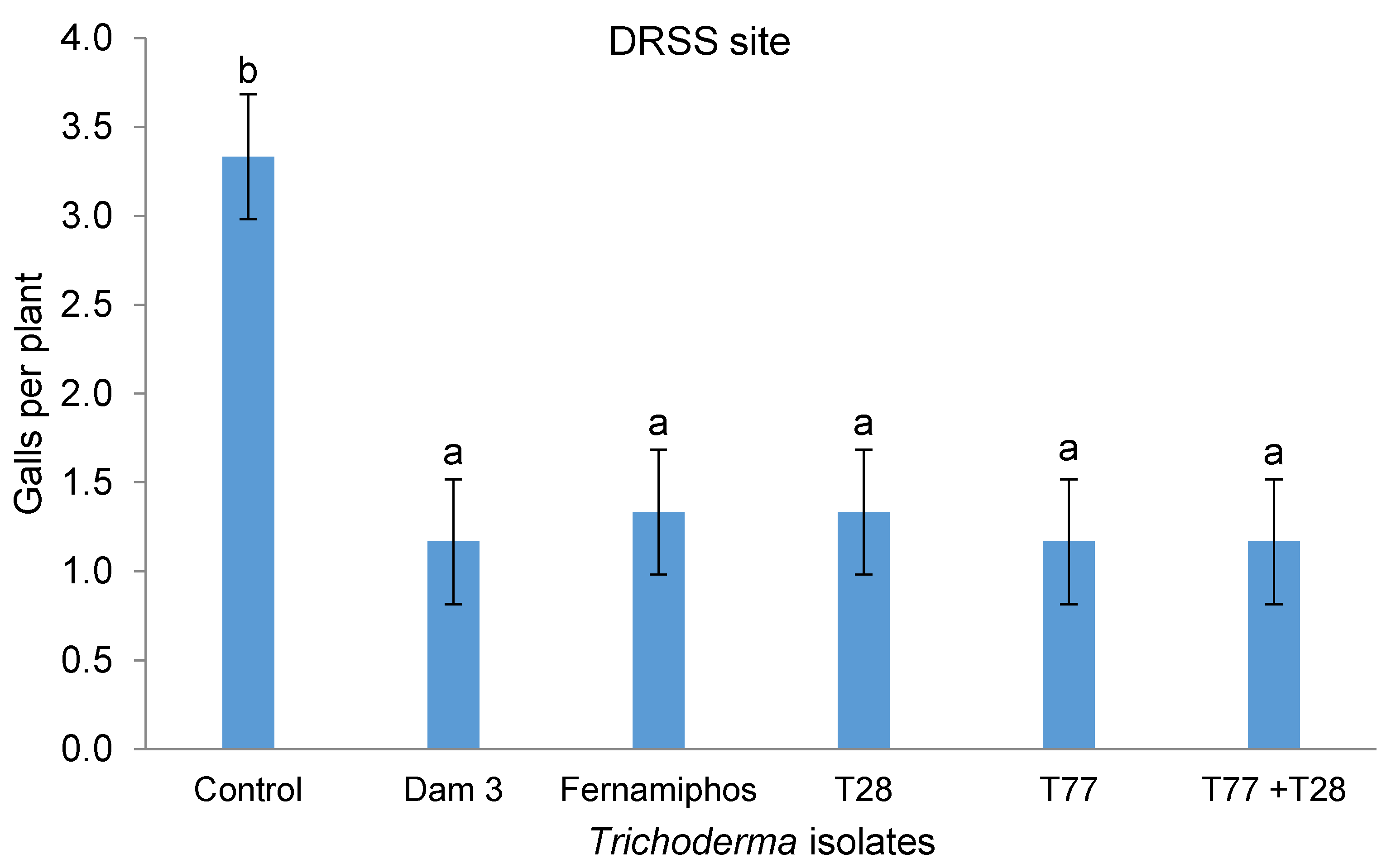

3.5.2. Effects on the Number of Root Knot Nematode Galls

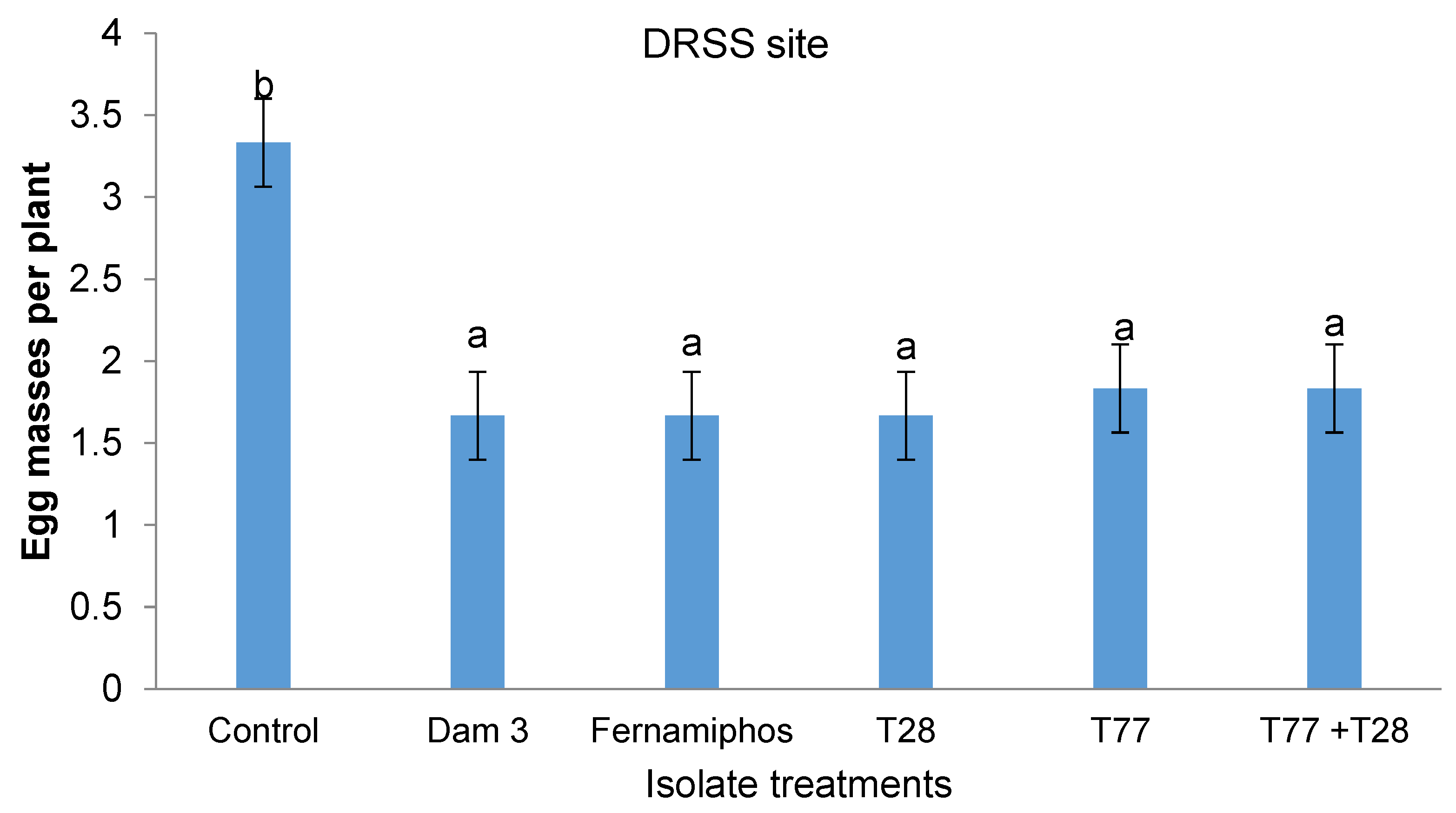

3.5.3. Effect on the Number of RKN Egg Masses

3.6. Effects of Isolate Treatments on Potato Plant Growth and Yield

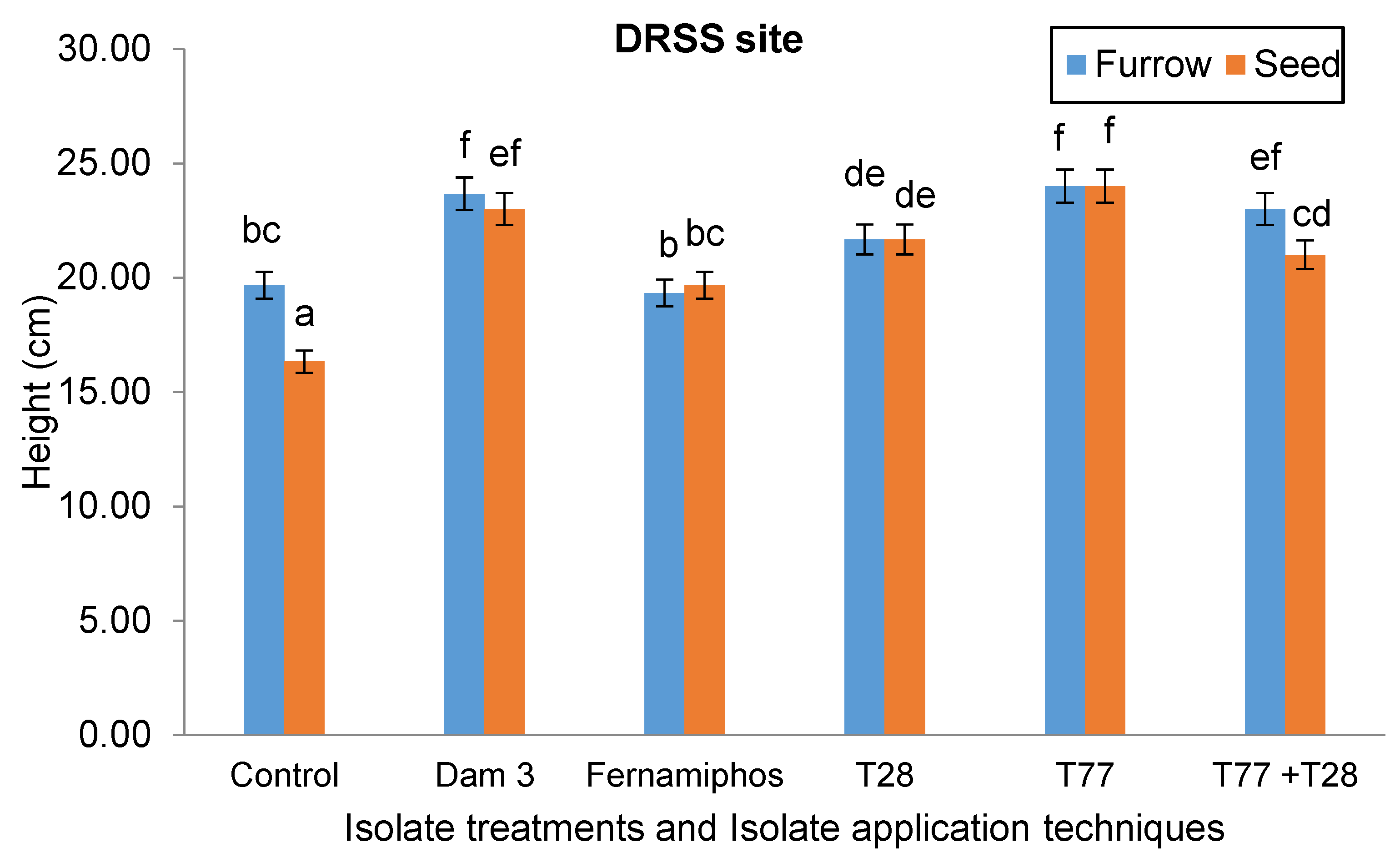

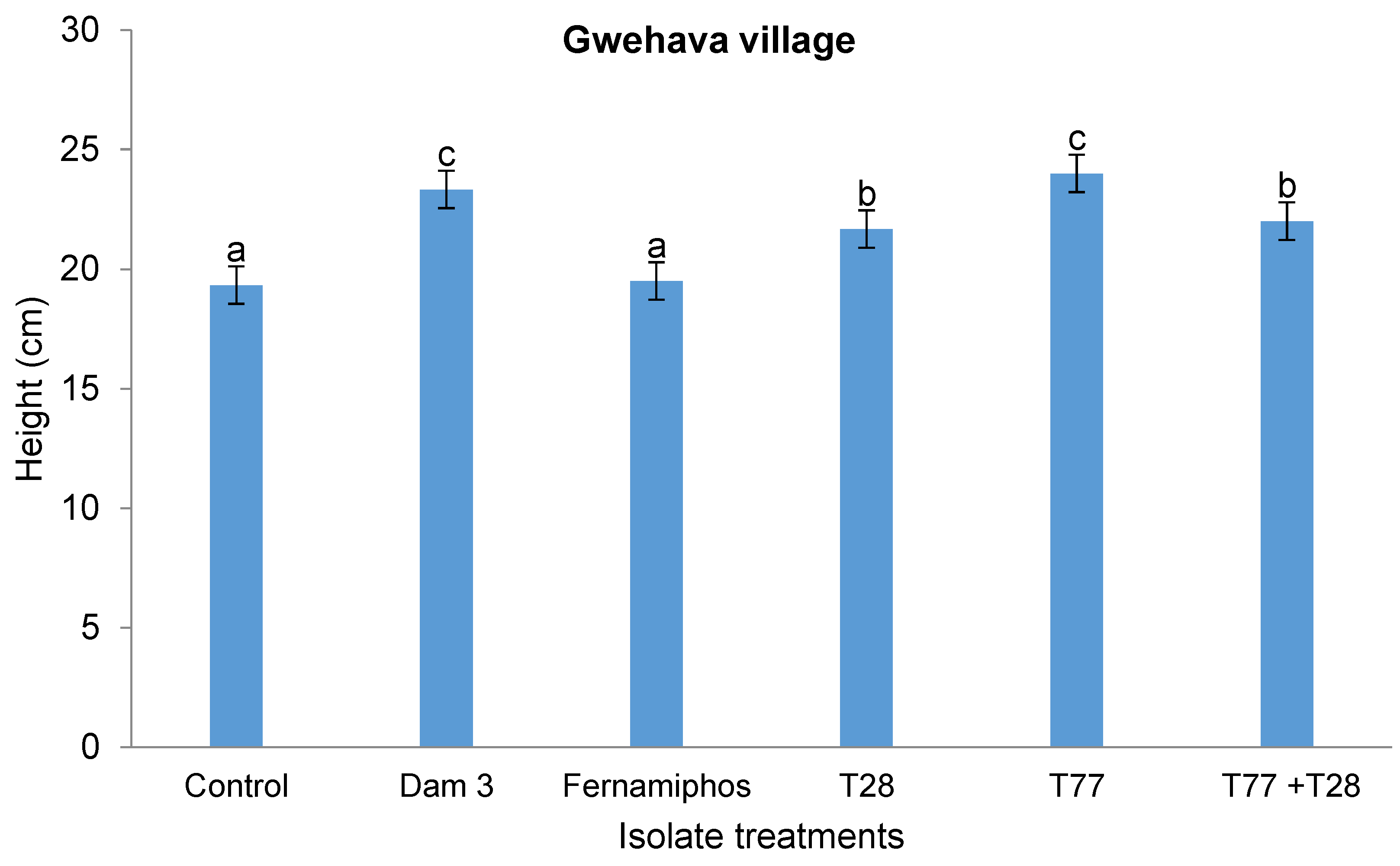

3.6.1. Effects on Plant Height

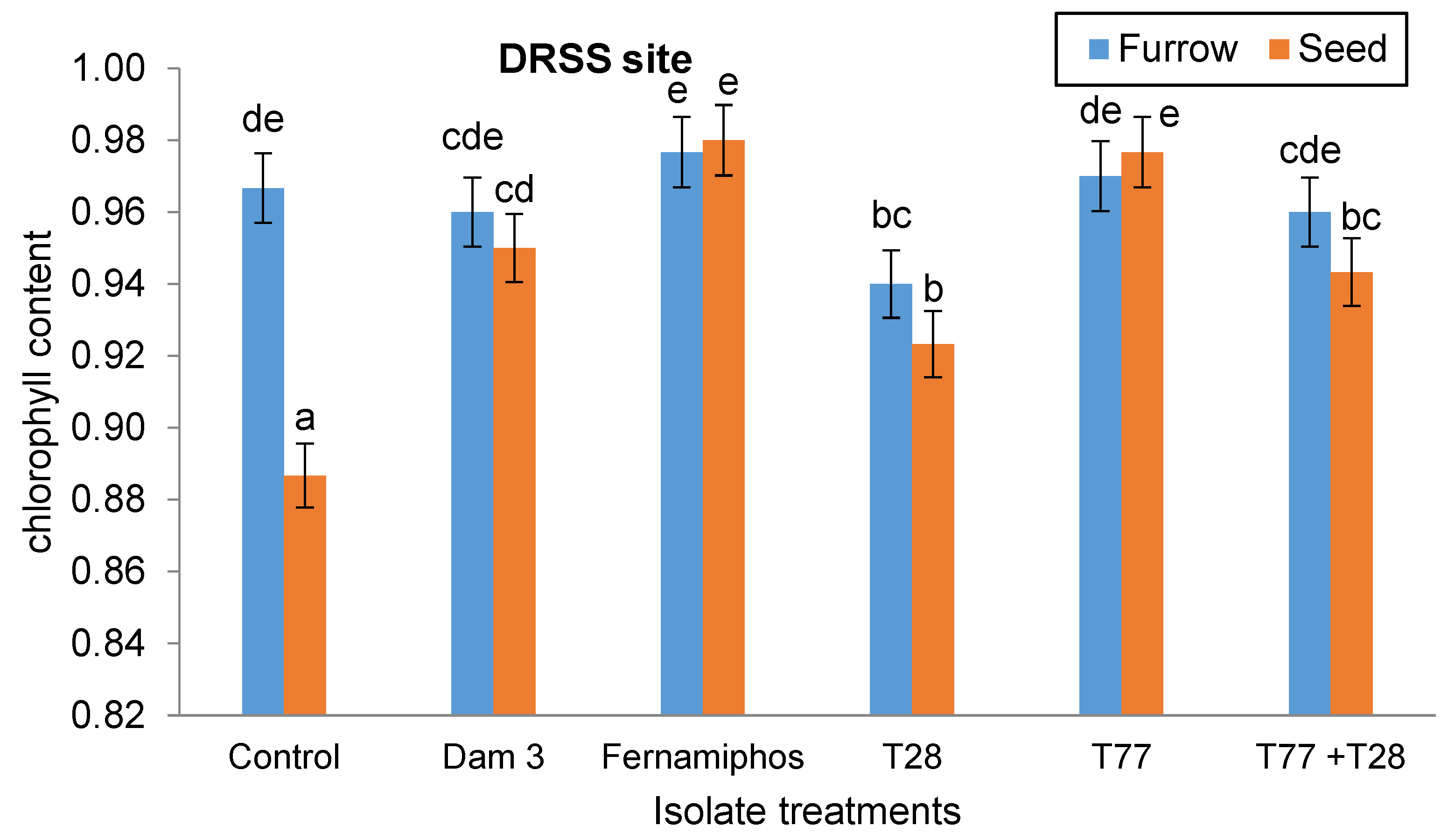

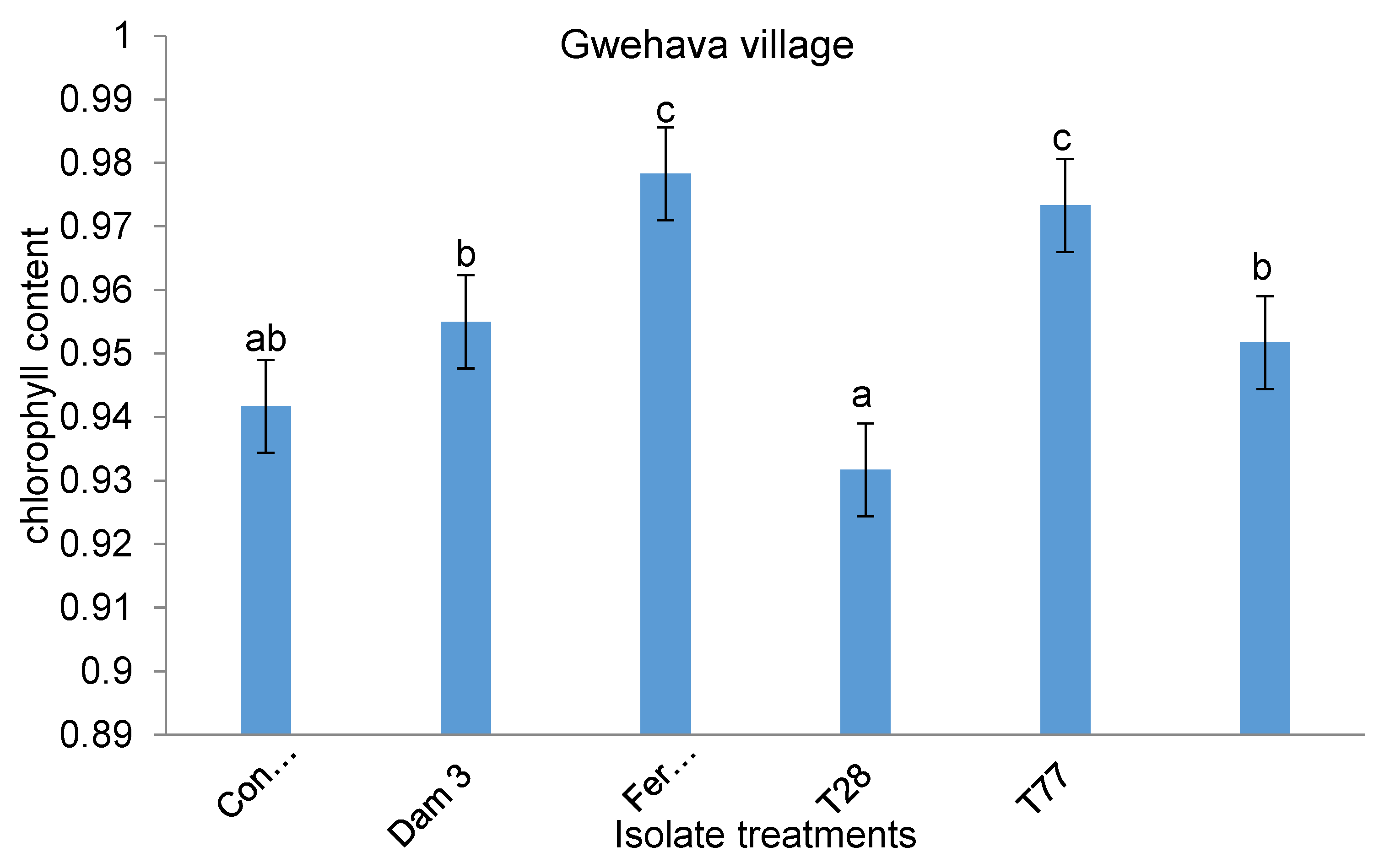

3.6.2. Effects on Potato Chlorophyll Content

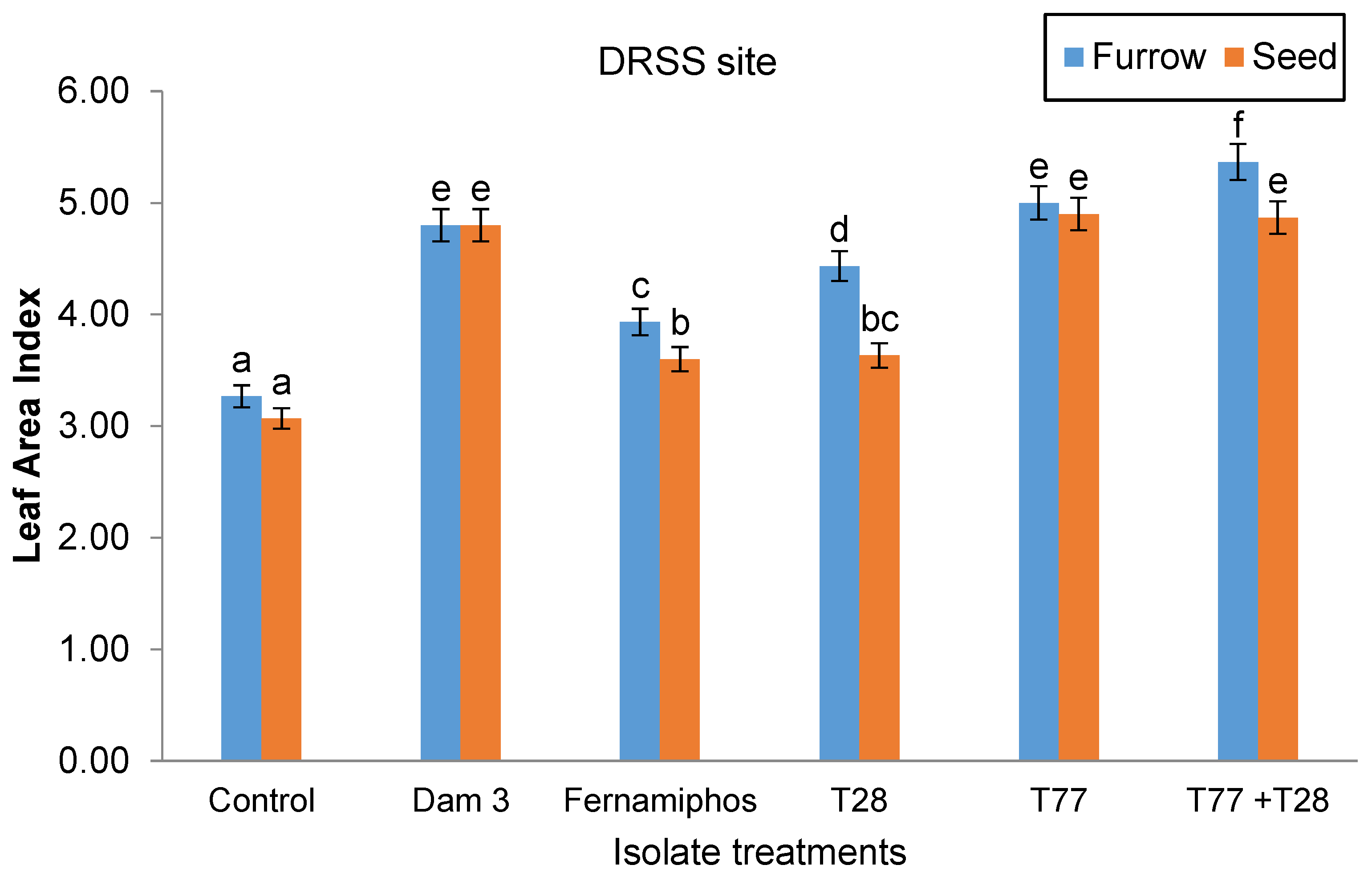

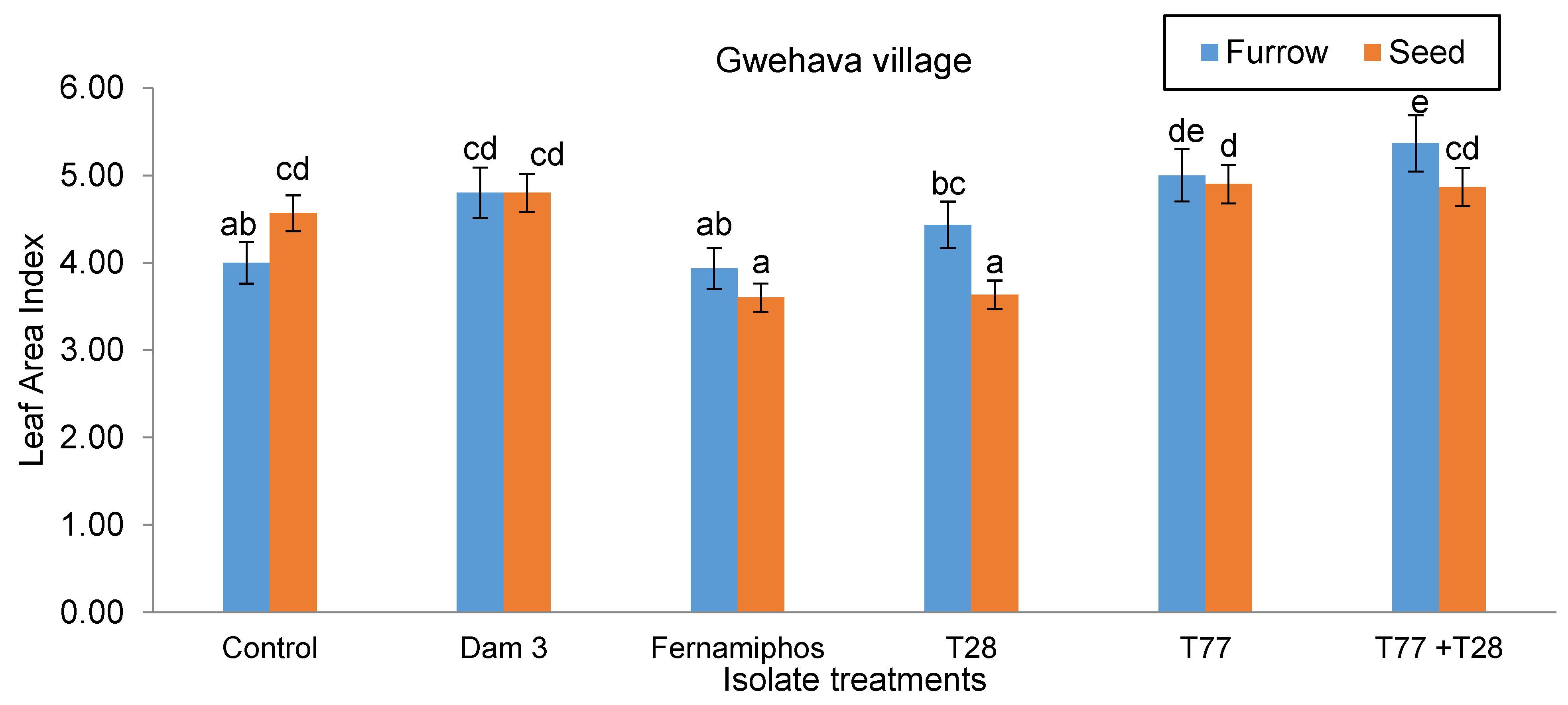

3.6.3. Effects on Leaf Area Index

3.6.4. Effect on Potato Tuber Size and Yield

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Trichoderma isolates on F. oxysporum growth and Fusarium wilt disease prevalence

4.2. Effect of Trichoderma Isolates on Nematode Egg Hatching, Juvenile Mortality and Galling

4.3. Effect of Trichoderma Isolates on Potato Growth and Yield

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DRSS | Department of Research and Specialist Services |

| FW-RKN | Fusarium wilt -root knot nematode |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| LSD | Least Significant Difference |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| RKN | Root knot nematode |

References

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.-P.; Kromann, P.; Andrade-Piedra, J.; Polar, V.; Hareau, G. The potato of the future: opportunities and challenges in sustainable agri-food systems. Potato Res 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gikundi, E.K.; Buzera, A.K.; Orina, I.N.; Sila, DN. Storability of Irish potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) varieties grown in Kenya, under different storage conditions. Potato Res 2022, 66, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Rauf, A.; Abbas, M.F.; Rehman, R. Isolation and identification of Verticillium dahliae causes wilt on potato in Pakistan. Pak. J. Phytopathol. 2012, 24, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gondal, A.S.; Javed, N.; Khan, S.A.; Hyder, S. Genotypic diversity of potato germplasm against root knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) infection in Pakistan. Int. J. Phytopathol. 2012, 1, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.F.; Aziz-ud-Din, G.A.; Qadir, A.; Ahmed, R. Major potato viruses in potato crops of Pakistan: a brief review. Int. J. Biol. Biotechnol 2013, 10, 425–430. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shennawy, M.Z.; Khalifa, E.Z.; Ammar, M.M.; Mousa, E.M.; Hafez, S.L. Biological control of the disease complex on potato caused by root-knot nematode and Fusarium wilt fungus. Nematol. Mediterr 2012, 40, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, F.S.O.; Mattos, V.S.; Silva, E.S.; Carvalho, M.A.S.; Teixeira, R.A.; Silva, J.C.; Correa, V.R. Nematodes affecting potato and sustainable practices for their management. “Potato: from Incas to all over the world. 2018, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkendi, E.M.; Kariuki, G.M.; Marais, M.; Moleleki, L.N. The threat of root-knot nematodes and fitness consequences. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 211, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar]

- Kassie, Y.G. Status of root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne species) and Fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum) disease complex on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in the Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia. Agric. Sci 2019, 10, 1090–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagawati, B.; Das, B.C.; Sinha, A.K. Interaction of Meloidogyne incognita and Rhizoctonia solani on okra. Ann. Plant Prot. Sci. 2007, 1, 533–535. [Google Scholar]

- Manzira, C. Potato production handbook. Potato Seed Association Zimbabwe. Jongwe Printers, Harare, Zimbabwe. 2010.

- Bairwa, A.; Venkatasalam, E.P.; Mhatre, P.H.; Bhatnagar, A.; Sharma, A.K.; et al. Biology and management of nematodes in potato. In: S Kumar et al. (eds). Sustainable management of potato pests and diseases. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jahanshir, A.; Dzhalilov Fevzi, S. The effects of fungicides on Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici associated with fusarium wilt of tomato. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2010, 50, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Barari, H. Biocontrol of tomato Fusarium wilt by Trichoderma species under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Cercetări Agronomice în Moldova 2016, 1, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyisa, B.; Lencho, A.; Selvaraj, T.; Getaneh, G. Evaluation of some botanicals and Trichoderma harzianum for the management of tomato root knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita (Kofoid and White) Chitwood). ACST. 2015, 4, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Askar, A.A.; Rashad, Y.M. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: a biocontrol agent against common bean Fusarium root rot disease. Plant Pathol. J. 2010, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.O. Beneficial bacteria of agricultural importance. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, E.K.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Nakazato, G. Quorum sensing system: Target to control the spread of bacterial infections. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzand, A.; Moosa, A.; Zubair, M.; Khan, A.R.; Massawe, V.C.; Tahir, H.A.S.; Sheikh, T.M.M.; Ayaz, M.; Gao, X. Suppression of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum by the induction of systemic resistance and regulation of antioxidant pathways in tomato using fengycin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Biomol. 2019, 9, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Farzand, A.; Mumtaz, F.; Khan, A.R.; Sheikh, T.M.M.; Haider, M.S.; Yu, C.; Wang, Y.; Ayaz, M.; Gu, Q.; et al. Novel genetic dysregulations and oxidative damage in Fusarium graminearum induced by plant defense eliciting psychrophilic Bacillus atrophaeus Ts1. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22, 12094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Yan, W.; Wei, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Cao, L.; et al. Nematicidal metabolites from endophytic fungus Chaetomium globosum YSC5. FEMS. Microb. Lett 2019, 366, fnz169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, B.K.; Pandey, R.K.; Goswami, J.; Tewari, D.D. Management of disease complex caused by root knot nematode and root wilt fungus on pigeon pea through soil organically enriched with vesicular arbuscular mycorrhiza, karanj (Pongamia pinnata) oilseed cake and farmyard manure. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B. 2007, 8, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawi, M.J. Tagetes erecta with native isolates of Paecilomyces lilacinus and Trichoderma hamatum in controlling root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica on tomato. IJAIEM. 2016, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo, A.F.; Lopes, E.A.; Fernandes, R.H.; Freitas, L.G.D.E.; Dallemole-Giaretta, R. Dose-response effect of Pochonia chlamydosporia against Meloidogyne incognita on carrot under field conditions. Rev. Caatinga. 2017, 30, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E.; Rabeendran, N.; Stewart, A. Biocontrol of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum infection of cabbage by Coniothyrium minitans and Trichoderma spp. Biocontrol Sci. Tech. 2014, 24, 1363–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Ahmad, I.; Ahamad, F. Effect of pure culture and culture filtrates of Trichoderma species on root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita infesting tomato. Indian Phytopathol. 2018, 71, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.P.; Kaur, I.; Masih, H.; Singh, A.K.; Singla, A. Efficacy of Trichoderma in controlling Fusarium wilt in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Res. Environ. Life Sci 2017, 10, 636–639. [Google Scholar]

- Martinuz, A.; Zewdu, G.; Ludwig, N.; Grundler, F.; Sikora, R.A.; Schouten, A. The application of Arabidopsis thaliana in studying tripartite interactions among plants, beneficial fungal endophytes and biotrophic plant-parasitic nematodes. Planta. 2015, 241, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poveda, J. Trichoderma parareesei favors the tolerance of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) to salinity and drought due to a chorismate mutase. Agron 2020, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiddin, F.A.; Khan, M.R.; Khan, S.M.; Bhat, B.H. Why Trichoderma considered a super hero (super fungus) against the evil parasites. Plant Pathol. J. 2010, 9, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebani, N.; Hadavi, N. Biological control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica by Trichoderma harzianum. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2016–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Medina, A.; Appels, F. V.; van Wees, S.C. Impact of salicylic acid- and jasmonic acid-regulated defences on root colonization by Trichoderma harzianum T-78. Plant Signal. Behav 2017, 12, e1345404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamapfene, K.W. Soils of tobacco. Nehanda Publishers. Harare, Zimbabwe. 1991.

- Hussey, R.S.; Barker, K.R. Comparison of methods for collecting inocula of Meloidogyne spp., including a new technique. Plant Dis Rep 1973, 57, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Colyer, P.D.; Kirkpatrick, T.L.; Caldwell, W.D.; Vernon, P.R. Root-knot nematode reproduction and root galling severity on related conventional and transgenic cotton cultivars. J. Cotton Sci. 2008, 4, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Southey, J.F. Laboratory Methods for Work with Plant and Soil Nematodes. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London, Great Britain. 1986.

- De Palma, M.; Salzano, M.; Villano, C.; Aversano, R.; Lorito, M.; Ruocco, M.; et al. Transcriptome reprogramming, epigenetic modifications and alternative splicing orchestrate the tomato root response to the beneficial fungus Trichoderma harzianum. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Mfarrej, M.F.B.; Nadeem, H.; Ahamad, L.; Hashem, M.; Alamri, S.; Gupta, R.; Ahmad, F. Trichoderma virens mitigates the root-knot disease progression in the chickpea plant. Acta Agri. Scand. Section B — Soil. Plant Sci. 2022, 72, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theradimani, M.; Thangaselvabai, T.; Swaminathan, V. Management of tuberose root rot caused by Sclerotium rolfsii by biocontrol agents and fungicides. Advances in Floriculture and Urban Horticulture, ICAR, New Delhi. 2018, 308-311.

- Forghani, F.; Hajihassani, A. Recent advances in the development of environmentally benign treatments to control root-knot nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galletti, S.; Paris, R.; Cianchetta, S. Selected isolates of Trichoderma gamsii induce different pathways of systemic resistance in maize upon Fusarium verticillioides challenge. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 233, 126406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, E.; Chet, I.; Viterbo, A.; Bar-Egal, M.; Nagan, H.; Samuels, G.J.; Spiegel, Y. Parasitism of Trichoderma on Meloidogyne javanica and role of the gelatinous matrix. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2007, 118, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Shakeel, A.; Waqar, S.; Handoo, Z.A.; Khan, A.A. Microbes vs. Nematodes: Insights into biocontrol through antagonistic organisms to control root-knot nematodes. Plants 2023, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompali, R.; Mehendrakar, S.S.; Venkata, P.K. Evaluation of biocontrol agents on root knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita and wilt causing fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. conglutinans in vitro. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, T.; Rajan, S.; Muthukumar, M.; Gopal, R.; Yadav, K.; Kumar, S.; et al. Biological management of banana Fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 using antagonistic fungal isolate CSR-T-3 (Trichoderma reesei). Front. Microbiol 2020, 11, 595845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Saha, K.; Dave, R.; Nidhin, P.; Murugesan, A. Estimation of leaf area index of mustard and potato from Sentinel-2 data using parametric, non-parametric and physical retrieval models. RSASE. 2025, 37, 101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J. Trichoderma and its role in biological control of plant fungal and nematode disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ul Haq, I.; Rahim, K.; Yahya, G.; Ijaz, B.; Maryam, S.; Paker, N.P. Eco-smart biocontrol strategies utilizing potent microbes for sustainable management of phytopathogenic diseases. Biotechnol Rep. 2024, 44, e00859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubheka, B.P.; Ziena, L.W. Trichoderma: A Biofertilizer and a Bio-Fungicide for Sustainable Crop Production. In. Trichoderma - Technology and Uses. F.P. Juliatti (Ed), IntechOpen. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Score | Degree of severity |

| 0 | No symptoms |

| 1 | 5% leaves yellow and wilted, very limited |

| 2 | 6-10% leaves yellow and wilted, limited wilting |

| 3 | 11-20% leaves yellow and wilted, moderate wilting |

| 4 | 21-50% leaves yellow and severe wilting |

| 5 | More than 50% of leaves are yellow, severe wilting and/or plant deaths |

| Score | Number of egg masses |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1-2 |

| 2 | 3-10 |

| 3 | 11-30 |

| 4 | 31-100 |

| 5 | 100 |

| Score | Degree of galling |

| 0 | Free from galls |

| 1 | < 5 galls |

| 2 | Trace to 25 galls |

| 3 | 20-100 galls |

| 4 | Numerous galls, mostly discrete |

| 5 | Numerous galls, many coalesced |

| 6 | Heavy, mostly coalesced |

| 7 | Very heavy, mass invasion, slight root growth |

| 8 | Mass invasion, no root development |

| Isolate treatment | Number of hatched eggs per 1.0 ml treatment solution | ||||

| Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | ||

| T77 T28 Dam 3 Control |

0a 0a 0a 69.34b |

4.00a 6.66a 10.66a 89.34b |

8.00a 16.00b 18.00b 132.66c |

12.00a 20.00b 24.00b 193.34c |

|

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| LSD0.05 | 9.476 | 9.964 | 5.752 | 4.348 | |

| CV (%) | 29.00 | 19.10 | 7.10 | 3.70 | |

| Isolate | Nematode mortality (%) | ||||

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | |

| T77 T28 Dam 3 Control |

38.00c 26.67a 32.67b 0d |

50.00b 41.33a 44.00a 0d |

66.67a 55.33a 60.00a 0d |

80.67b 70.67a 75.33a 0d |

96.00c 92.67a 94.00b 0d |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| LSD0.05 | 4.482 | 4.348 | 13.13 | 6.79 | 1.087 |

| CV (%) | 9.8 | 6.80 | 15.30 | 6.40 | 0.80 |

| Isolate treatment | Disease incidence (%) | Disease severity | ||

| DRSS site | Gwehava village | DRSS site | Gwehava village | |

| Control Dam 3 Fenamiphos T28 T77 T28 + T77 |

27.83d 15.17abc 16.83bc 17.17c 14.83ab 14.50a |

21.17c 17.17a 18.83b 19.17b 16.83a 16.50a |

3.167c 0.500ab 0.667ab 1.000b 0.333a 0.667ab |

2.000c 0.550ab 0.717ab 1.050b 0.387a 0.717ab |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| LSD0.05 | 2.183 | 1.798 | 0.6564 | 0.6136 |

| CV (%) | 10.30 | 9.00 | 21.90 | 19.50 |

| Isolate application technique (number of galls per plant) | ||

| Isolate treatment | Furrow | Seed |

| Control Dam 3 Fenamiphos T28 T77 T28 + T77 |

2.000b 1.000a 1.333a 1.333a 1.333a 1.333a |

3.000c 1.333a 1.667a 1.330a 1.000a 1.000a |

| P-value | 0.047 | |

| LSD0.05 | 0.6368 | |

| CV (%) | 25.5 | |

| Isolate Treatment | Tuber size (g) | Tuber yield (t/ha) | ||

| DRSS site | Gwehava village | DRSS site | Gwehava village | |

| Control Dam 3 Fenamiphos T28 T77 T28 + 77 |

119.17a 127.33bc 129.27cd 125.80b 129.20cd 130.12d |

115.50a 123.67b 126.13c 122.40b 128.12d 129.23e |

12.08a 27.43bc 30.58cd 25.13b 34.50e 33.40de |

15.18a 29.54bc 32.08c 28.43b 32.50c 32.00c |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| LSD | 2.201 | 1.904 | 3.165 | 3.128 |

| CV (%) | 14.00 | 12.00 | 10.50 | 9.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).