Submitted:

16 February 2024

Posted:

16 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Material

2.1. Isolation of Bacteria from Sugar Beet Rhizosphere Soil

2.2. Screening of Antagonistic Activity among Rhizosphere Bacteria

2.2.1. Dual-Culture Setup for Confrontation Testing

2.2.2. Antibiotic Activity through Bacterial Supernatant Analysis

2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis.

2.4. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification of 16S rDNA and Sanger Sequencing

2.5. PCR Amplifications Lipopeptide-Encoding Genes

2.6. Biochemical and Plant-Growth Promotion Tests

2.7. Effects of Bacterial Isolates on Sugar Beet Growth in Greenhouse Conditions

2.8. Effects of Four Bacterial Isolates on Sugar Beet Growth in the Field

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolating and Identifying Bacteria from the Rhizosphere Soil of Sugar Beet

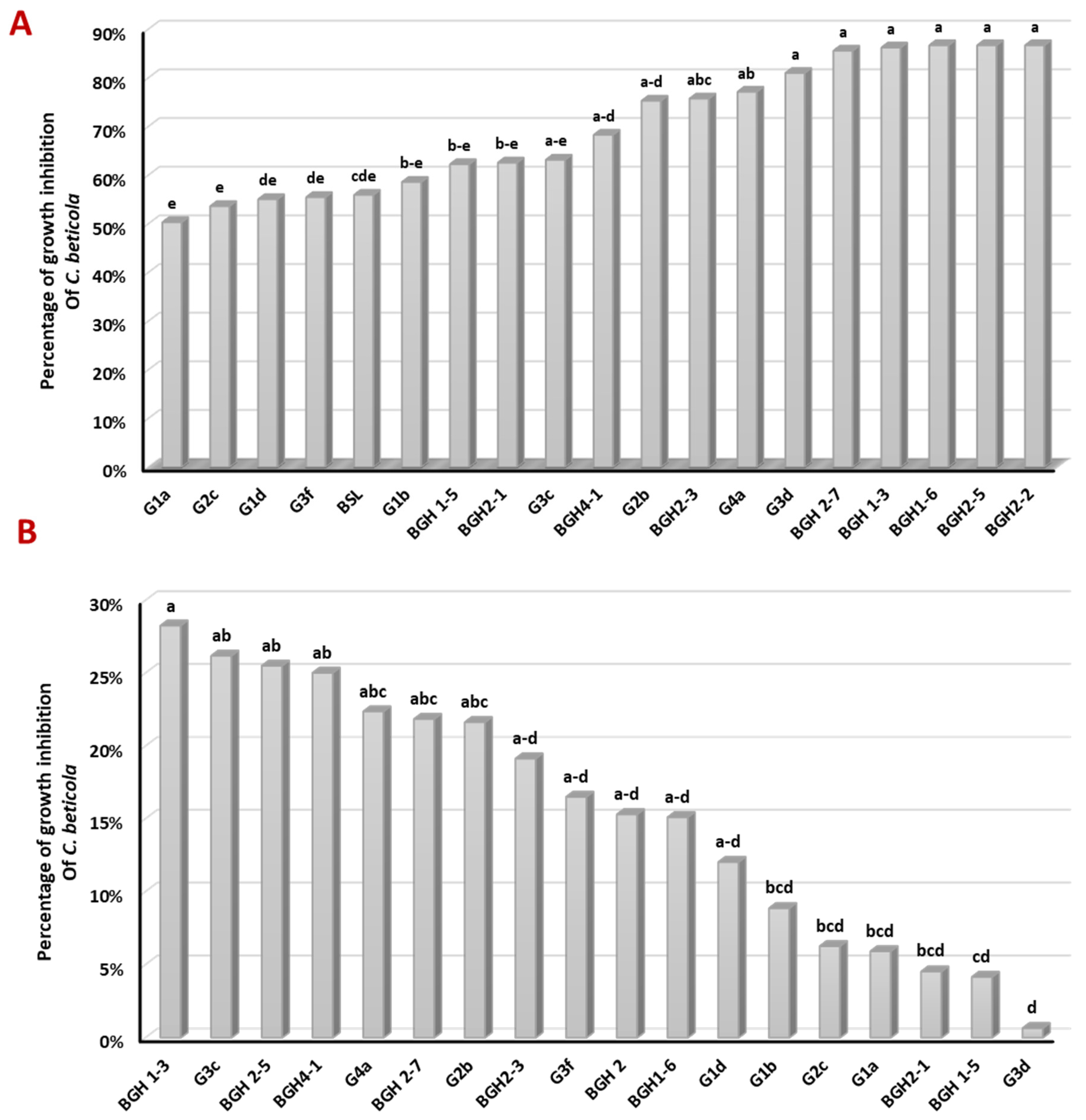

3.2. Antagonism against C. beticola in Confrontation Assay in PDA Medium and PDA Amended with Supernatant

3.3. PCR Detection of Lipopeptide Genes

3.4. Biochemical and Plant-Growth Promotion Tests

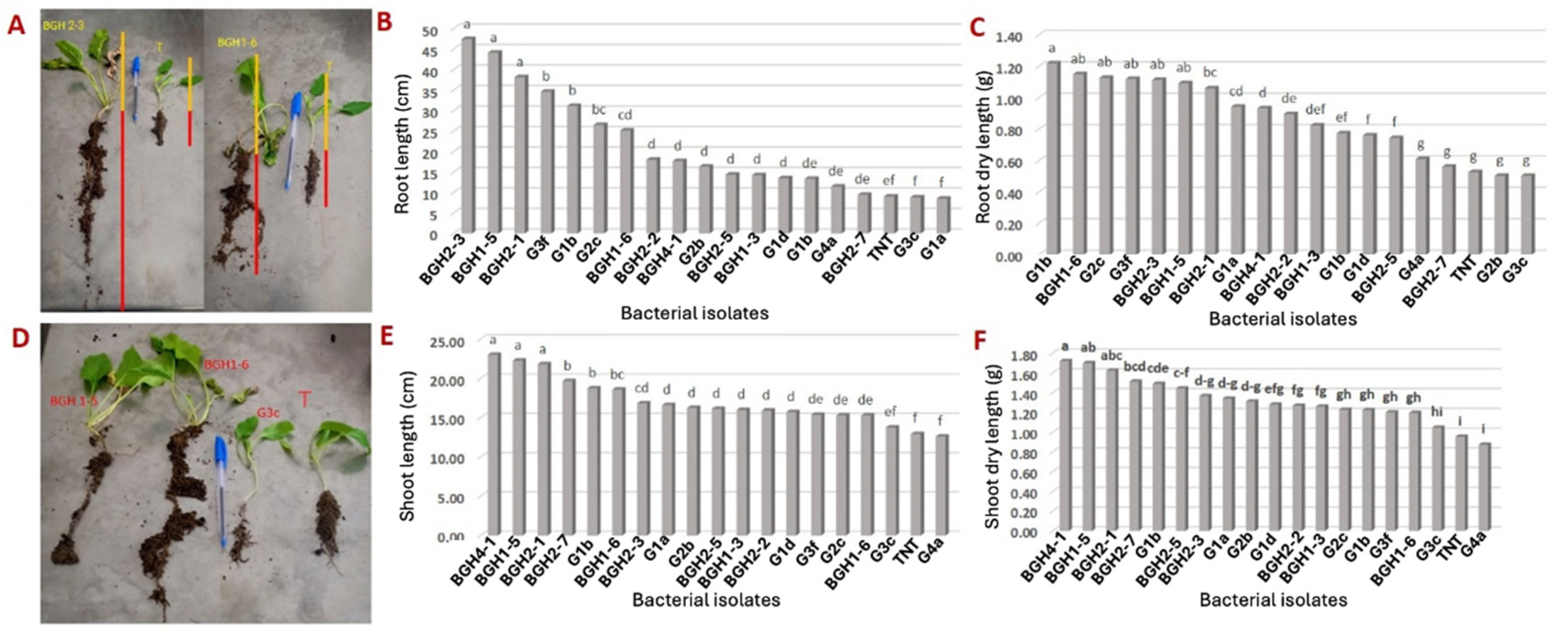

3.5. Effects of Bacterial Isolates on Sugar Beet Growth in Controlled Conditions

3.6. Effects of Four Bacterial Isolates on Sugar Beet Growth in the Field

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, W.; Li, K.; Liu, D.; Xing, W. Cercospora leaf spot disease of sugar beet. Plant Signal Behav 2023, 18, 2214765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, L.I.; Spanner, R.E.; Ebert, M.K.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Stukenbrock, E.H.; de Jonge, R.; Secor, G.A.; Bolton, M.D. Cercospora beticola: The intoxicating lifestyle of the leaf spot pathogen of sugar beet. Molecular Plant Pathology 2020, 21, 1020–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaracis, G.N.; Biancardi, E. Breeding for Cercospora resistance in sugarbeet. In Cercospora beticola Sacc. biology, agronomic influence and control measures in sugar beet., 2nd Edition ed.; Asher, M.J.C., Ed.; Advances in Sugar Beet Research; International Institute for Beet Research: 2000; pp. 177-195.

- Jacobsen, B.J.; Franc, G.D.; Harveson, R.M.; Hanson, L.E.; Hein, G.L. Foliar disease casused by fungi and Oomycetes. In Compendium of beet diseases and pests: The Cercospora leaf spot, 2nd Edition ed.; Harveson, R.M., Hanson, L.E., Hein, G.L., Eds.; American Phytopathological Society: 2009; pp. 7-10.

- Rossi, V.; Meriggi, P.; Biancardi, E.; Rosso, F. Effect of Cercospora leaf spot on sugarbeet growth, yield and quality. Cercospora beticola Sacc. biology, agronomic influence and control measures in sugar beet. 2000, 49-76. [CrossRef]

- Lartey, R.T.; Weiland, J.J.; Bucklin-Comiskey, S. A PCR protocol for rapid detection of Cercospora beticola in sugarbeet tissues. Journal of sugar beet research 2003, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.K.M. Yield penalties of disease resistance in crops. Current opinion in plant biology 2002, 5, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummert, A.; Ladewig, E.; Bürcky, K.; Märländer, B. Variety resistance to Cercospora leaf spot and fungicide application as tools of integrated pest management in sugar beet cultivation–A German case study. Crop Protection 2015, 72, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.; Kenter, C.; Holst, C.; Marlander, B. New Generation of Resistant Sugar Beet Varieties for Advanced Integrated Management of Cercospora Leaf Spot in Central Europe. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panella, L.; Lewellen, R.T. Broadening the genetic base of sugar beet: introgression from wild relatives. Euphytica 2007, 154, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.M.; Hanson, L.E.; Franc, G.D.; Panella, L. Analysis of β-tubulin gene fragments from benzimidazole-sensitive and-tolerant Cercospora beticola. Journal of Phytopathology 2006, 154, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, G.A.; Rivera, V.V.; Khan, M.F.R.; Gudmestad, N.C. Monitoring Fungicide Sensitivity of Cercospora beticola of Sugar Beet for Disease Management Decisions. Plant Disease 2010, 94, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoglanidis, G.S.; Thanassoulopoulos, C.C. Cross-resistance patterns among sterol biosynthesis inhibiting fungicides (SBIs) in Cercospora beticola. European journal of plant pathology 2003, 109, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Housni, Z.; Ezrari, S.; Tahiri, A.; Ouijja, A. Resistance of Cercospora beticola Sacc isolates to thiophanate methyl (benzimidazole), demethylation inhibitors and quinone outside inhibitors in Morocco. EPPO Bulletin 2020, epp.12673-epp.12673. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, W.W.; Hanson, L.E.; Franc, G.D.; Stump, W.L.; Gachango, E.; Clark, G.; Stewart, J. First report of strobilurin resistance in Cercospora beticola in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) in Michigan and Nebraska, USA. New Disease Reports 2012, 26, 3-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, K.; Mihók, M.; Roháčik, T.; Mišľan, Ľ. Sensitivity of Cercospora beticola to fungicides in Slovakia. Acta Fytotech. Et Zootech 2020, 23, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trkulja, N.; Hristov, N. Morphological and genetic diversity of Cercospora beticola isolates. In Proceedings of the International Conference on BioScience: Biotechnology and Biodiversity-Step in the Future, The Fourth Joint UNS-PSU Conference, Book of Proceedings, 2012; pp. 18-20. 2012; 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.F.A.; Mikhail, S.P.H.; Shaheen, S.I. Performance efficiency of some biocontrol agents on controlling Cercospora leaf spot disease of sugar beet plants under organic agriculture system. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2023, 167, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaterra, A.; Badosa, E.; Daranas, N.; Frances, J.; Rosello, G.; Montesinos, E. Bacteria as Biological Control Agents of Plant Diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, R.; Aksissou, W.; Lyousfi, N.; Ezrari, S.; Blenzar, A.; Tahiri, A.; Ennahli, S.; Hrustić, J.; MacLean, D.; Amiri, S. Biocontrol activity and putative mechanism of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (SF14 and SP10), Alcaligenes faecalis ACBC1, and Pantoea agglomerans ACBP1 against brown rot disease of fruit. Microbial Pathogenesis 2020, 139, 103914-103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezrari, S.; Mhidra, O.; Radouane, N.; Tahiri, A.; Polizzi, G.; Lazraq, A.; Lahlali, R. Potential role of rhizobacteria isolated from citrus rhizosphere for biological control of citrus dry root rot. Plants 2021, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radouane, N.; Adadi, H.; Ezrari, S.; Kenfaoui, J.; Belabess, Z.; Mokrini, F.; Barka, E.A.; Lahlali, R. Exploring the Bioprotective Potential of Halophilic Bacteria against Major Postharvest Fungal Pathogens of Citrus Fruit Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 922-922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambugala, K.M.; Daranagama, D.A.; Phillips, A.J.L. Fungi vs. Fungi in Biocontrol : An Overview of Fungal Antagonists Applied Against Fungal Plant Pathogens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimkić, I.; Janakiev, T.; Petrović, M.; Degrassi, G.; Fira, D. Plant-associated Bacillus and Pseudomonas antimicrobial activities in plant disease suppression via biological control mechanisms-A review. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2022, 117, 101754-101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzanlou, M.; Mousavi, S.; Bakhshi, M.; Khakvar, R.; Bandehagh, A. Inhibitory effects of antagonistic bacteria inhabiting the rhizosphere of the sugarbeet plants, on Cercospora beticola Sacc., the causal agent of Cercospora leaf spot disease on sugarbeet. Journal of Plant Protection Research 2016, 56, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervišević, M.; Đorđević, N.; Knežević, I.; Đorđević, S. Antagonistic activity of bacterial isolates against Cercospora beticola in laboratory conditions. 2021, 2021; pp. 47-47.

- Goswami, D.; Thakker, J.N.; Dhandhukia, P.C. Portraying mechanics of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria ( PGPR ): A review. Cogent Food & Agriculture (2016) 2016, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeron, A.; Khare, E.; Jha, C.K.; Meena, V.S.; Mohammed, S.; Aziz, A.; Islam, M.T.; Kim, K.; Meena, S.K.; Pattanayak, A.; et al. Revisiting the plant growth - promoting rhizobacteria : lessons from the past and objectives for the future. Archives of Microbiology 2020, 202, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KaragÖZ, H.; Cakmakci, R.; Hosseinpour, A.; Kodaz, S. Alleviation of water stress and promotion of the growth of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) plants by multi-traits rhizobacteria. Applied Ecology & Environmental Research 2018, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Farhaoui, A.; Adadi, A.; Tahiri, A.; El Alami, N.; Khayi, S.; Mentag, R.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Mokrini, F.; Belabess, Z.; Lahlali, R. Biocontrol potential of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) against Sclerotiorum rolfsii diseases on sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2022, 119, 101829-101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. Journal of pharmaceutical analysis 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llop, P.; Bonaterra, A.; Peñalver, J.; López, M.a.M. Development of a Highly Sensitive Nested-PCR Procedure Using a Single Closed Tube for Detection of Erwinia amylovora in Asymptomatic Plant Material. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2000, 66, 2071–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einloft, T.C.; Hartke, S.; de Oliveira, P.B.; Saraiva, P.S.; Dionello, R.G. Selection of rhizobacteria for biocontrol of Fusarium verticillioides on non-rhizospheric soil and maize seedlings roots. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailadores Bollona, J.P.; Delgado Paredes, G.E.; Wagner, M.L.; Rojas Idrogo, C. In vitro tissue culture, preliminar phytochemical analysis, and antibacterial activity of Psittacanthus linearis (Killip) JK Macbride (Loranthaceae). Revista Colombiana de Biotecnología 2019, 21, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, P.F.J.; Verreet, J.A. An integrated pest management system in Germany for the control of fungal leaf diseases in sugar beet: The IPM sugar beet model. Plant disease 2002, 86, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthipan, P.; Preetham, E.; Machuca, L.L.; Rahman, P.K.S.M.; Murugan, K.; Rajasekar, A. Biosurfactant and degradative enzymes mediated crude oil degradation by bacterium Bacillus subtilis A1. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 193-193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.M.; Mody, K.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. Physicochemical characterization of biosurfactant and its potential to remove oil from soil and cotton cloth. Carbohydrate polymers 2012, 89, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajfarajollah, H.; Mokhtarani, B.; Noghabi, K.A. Newly antibacterial and antiadhesive lipopeptide biosurfactant secreted by a probiotic strain, Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2014, 174, 2725–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramani, K.; Jain, S.C.; Mandal, A.B.; Sekaran, G. Microbial induced lipoprotein biosurfactant from slaughterhouse lipid waste and its application to the removal of metal ions from aqueous solution. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2012, 97, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khmelevtsova, L.E.; Sazykin, I.S.; Azhogina, T.N.; Sazykina, M.A. Influence of Agricultural Practices on Bacterial Community of Cultivated Soils. Agriculture 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, Q.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y. Conservation tillage increases soil bacterial diversity in the dryland of northern China. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarza, P.; Yilmaz, P.; Pruesse, E.; Glockner, F.O.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.H.; Whitman, W.B.; Euzeby, J.; Amann, R.; Rossello-Mora, R. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014, 12, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Kiewnick, A.; Jacobsen, B.J.; Sands, D.C. Biological control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, the causal agent of basal kernel blight of barley, by antagonistic Pantoea agglomerans. Phytopathology 2000, 90, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhegger, R.; Ihring, A.; Gantner, S.; Bahnweg, G.; Knappe, C.; Vogg, G.; Hutzler, P.; Schmid, M.; Van Breusegem, F.; Eberl, L.E.O. Induction of systemic resistance in tomato by N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone-producing rhizosphere bacteria. Plant, Cell & Environment 2006, 29, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, E.; Safaie, N.; Shams-Baksh, M.; Mahmoudi, B. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SB14 from rhizosphere alleviates Rhizoctonia damping-off disease on sugar beet. Microbiological research 2016, 192, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa, N.Đ.; Giàu, N.Đ.N.; Tuấn, T.Q. Effects of Serratia nematodiphila CT-78 on rice bacterial leaf blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Biological Control 2016, 103, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, E.A.D. Induction of induced systemic resistance in fodder beet (Beta vulgaris L.) to Cercospora leaf spot caused by (Cercospora beticola Sacc.). Egyptian Journal of Phytopathology 2018, 46, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehsah, M.D.; El-Kot, G.A.; El-Nogoumy, B.A.; Alorabi, M.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Salama, N.H.; El-Tahan, A.M. Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis, Moringa oleifera seeds extract and potassium bicarbonate on Cercospora leaf spot on sugar beet. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pethybridge, S.J.; Vaghefi, N.; Kikkert, J.R. Management of Cercospora leaf spot in conventional and organic table beet production. Plant disease 2017, 101, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Y.; Gancel, F.; Béchet, M.; Drider, D.; Jacques, P. Study of the correlation between fengycin promoter expression and its production by Bacillus subtilis under different culture conditions and the impact on surfactin production. Archives of microbiology 2017, 199, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostertz, J.; Scharf, C.; Hecker, M.; Homuth, G. Transcriptome and proteome analysis of Bacillus subtilis gene expression in response to superoxide and peroxide stress. Microbiology 2004, 150, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.; Küster-Schöck, E.; Grossman, A.D.; Zuber, P. Spx-dependent global transcriptional control is induced by thiol-specific oxidative stress in Bacillus subtilis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, 13603–13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Housni, Z.; Tahiri, A.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Ouijja, A. Occurrence of Cercospora beticola Sacc populations resistant to benzimidazole, demethylation-inhibiting, and quinone outside inhibitors fungicides in Morocco. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2023, 165, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Salem, H.M.; Ahmed, A.I.; Mahmood, M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Ebrahim, A.A.M.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Negm, S.H.; et al. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms as biocontrol agents of plant diseases: Mechanisms, challenges and future perspectives. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 923880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÇInar, V.M.; Aydın, Ü. The effects of some biofertilizers on yield, chlorophyll index and sugar content in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris var. saccharifera L.). Ege Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi 2021, 58, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.P.; Jacobsen, B.J. Optimizing a Bacillus subtilis isolate for biological control of sugar beet Cercospora leaf spot. Biological control 2003, 26, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowtham, H.G.; Murali, M.; Singh, S.B.; Lakshmeesha, T.R.; Narasimha Murthy, K.; Amruthesh, K.N.; Niranjana, S.R. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens improves plant growth and induces resistance in chilli against anthracnose disease. Biological Control 2018, 126, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Lu, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Li, S.; Xu, D.; Wu, L. Production exopolysaccharide from Kosakonia cowanii LT-1 through solid-state fermentation and its application as a plant growth promoter. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 150, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, A.; Ali, H.; Javaid, A.; Awan, Z.A. Contending charcoal rot disease of mungbean by employing biocontrol Ochrobactrum ciceri and zinc. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2020, 26, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaras, A.; Roumeliotis, E.; Ntasiou, P.; Karaoglanidis, G. Bacillus subtilis MBI600 promotes growth of tomato plants and induces systemic resistance contributing to the control of soilborne pathogens. Plants 2021, 10, 1113-1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthu Narayanan, M.; Ahmad, N.; Shivanand, P.; Metali, F. The role of endophytes in combating fungal-and bacterial-induced stress in plants. Molecules 2022, 27, 6549-6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ovakim, D.H.; Charles, T.C.; Glick, B.R. An ACC deaminase minus mutant of Enterobacter cloacae UW4No longer promotes root elongation. Current microbiology 2000, 41, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, M.; Bodhankar, S.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, P.; Singh, J.; Nain, L. PGPR mediated alterations in root traits: way toward sustainable crop production. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021, 4, 618230-618230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbrosses, G.; Contesto, C.; Varoquaux, F.; Galland, M.; Touraine, B. PGPR-Arabidopsis interactions is a useful system to study signaling pathways involved in plant developmental control. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2009, 4, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Swapnil, P.; Divyanshu, K.; Kumar, S.; Harish; Tripathi, Y.N.; Zehra, A.; Marwal, A.; Upadhyay, R.S. PGPR-mediated induction of systemic resistance and physiochemical alterations in plants against the pathogens: Current perspectives. Journal of Basic Microbiology 2020, 60, 828–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain ID | Accession number | Length (bp) | Coverage (%) | Identity (%) | Closest taxon (Accession Number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGH2-7 | MT256074 | 1501 | 99 | 95.56 | Bacillus vallismortis (FJ386541) |

| BGH4-1 | MW002558 | 559 | 100 | 96.08 | Bacillus halotolerans (MT271912) |

| G1B | MT256075 | 1477 | 99 | 97.35 | Bacillus subtilis (KP876486) |

| G2B | MT256077 | 1495 | 99 | 96.45 | Bacillus halotolerans (MF417800) |

| G3C | MT256076 | 1483 | 99 | 96.46 | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (PP125657) |

| G1D | MW002221 | 1019 | 99 | 97.84 | Bacillus subtilis (KY818937) |

| G3F | MT254817 | 1524 | 99 | 94.72 | Bacillus subtilis (OM978656) |

| G3D | MT256072 | 1500 | 98 | 95.29 | Bacillus subtilis (KY652939) |

| BGH2-3 | MW086541 | 536 | 99 | 95.86 | Enterobacter sp. (JX103562) |

| BGH1-5 | MW092092 | 1000 | 100 | 93.47 | Kosakonia cowanii MG871199 |

| BGH2-5* | MT254758 | 1513 | 98 | 94.16 | Pantoea agglomerans MZ647535 |

| BGH1-6* | MT254751 | 576 | 100 | 100 | Pantoea agglomerans (OQ202156) |

| BGH2-1 | MT254818 | 903 | 98 | 91.12 | Pantoea conspicua (MW568057) |

| G4A | MW092005 | 555 | 99 | 99.29 | Pantoea sp. (JN853255) |

| G1A | MW079530 | 539 | 100 | 99.63 | Pseudomonas azotoformans (MK883209) |

| BGH1-3 | MW079843 | 559 | 100 | 97.50 | Serratia liquefaciens (MN326772) |

| BGH2-2 | MW008870 | 301 | 99 | 97.00 | Serratia nematodiphila (MH669373) |

| G2C | MW008604 | 645 | 99 | 96.57 | Serratia nematodiphila (MN691578) |

| Bacterial isolates | Leptopetide encoding genes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BamC | Itup | fend | Sfp | |

| G1A | + | + | + | - |

| G2C | + | - | + | + |

| G1D* | + | + | + | + |

| G3F | + | + | - | + |

| G1B* | + | + | + | + |

| BGH 1-5 | + | - | + | - |

| BGH2-1 | + | + | + | + |

| G3C | - | + | + | - |

| BGH4-1 | - | + | + | + |

| G2B | - | + | + | + |

| BGH2-3 | + | - | + | - |

| G4A | + | + | + | - |

| G3D | + | - | + | + |

| BGH 2-7 | + | + | + | - |

| BGH 1-3* | + | + | + | + |

| BGH1-6 | + | + | - | - |

| BGH2-2* | + | + | + | + |

| BGH2-5 | + | + | + | - |

| Bacteria isolates | ICLa | IPCa | IPRa | ISPa | IAMa | ICHa | AIA | HCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2c | 0 | 1.37±0.08 | 4.12±0.28 | 1.02±0.16 | 1.26±0.06 | 0 | +++ | ++ |

| BGH 1-5 | 0 | 0 | 1.17±0.41 | 1.49±0.16 | 0 | 5.21±0.71 | +++ | - |

| BGH 2-1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.94±0.47 | +++ | +++ |

| BGH 2-5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.01±0.43 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + |

| BGH 1-6 | 1.5±0.04 | 1.98±0.79 | 0 | 1.16±0.62 | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| G3f | 0 | 0 | 3.76±0.22 | 1.37±0.08 | 0 | 0 | + | - |

| G2b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.40±0.12 | 0 | 0 | + | ++ |

| BGH 2-2 | 0 | 0 | 1.21±0.46 | 1.25±0.19 | 0 | 0 | + | ++ |

| BGH 1-3 | 1.61±0.09 | 1.36±0.34 | 4.12±0.30 | 0 | 1.28±0.04 | 1.53±0.01 | + | +++ |

| G3d | 1.57±0.06 | 0 | 3.09±1.45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + |

| G4a | 1.54±0.01 | 1.58±0.11 | 1.82±0.10 | 0 | 1.14±0.00 | 0 | + | + |

| BGH 2-7 | 0 | 2.03±0.24 | 5.0±0.21 | 1.41±0.26 | 1.06±0.00 | 0 | + | ++ |

| G1b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.19±0.01 | 0 | - | - |

| BGH 2-3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.55±0.01 | 0 | 0 | - | + |

| BGH 4-1 | 0 | 0 | 4.85±0.10 | 1.14±0.20 | 1.24±0.05 | 0 | - | +++ |

| G1d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.19±0.47 | 0 | 0 | - | + |

| G1a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | + |

| G3c | 1.62±0.05 | 0 | 1.42±0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Treatments | Identity (closest BLAST match)a | AUDPCb | Efficiency (%) | signification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGH 2-7 | Bacillus vallismortis | 10.31±0.12 | 77.42% | b |

| BGH 1-3 | Serratia liquefaciens | 11.94±0.14 | 73.86% | b |

| BGH 2-2 | Serratia nematodiphila | 17.61±0.24 | 61.45% | c |

| BGH 1-6 | Pantoea agglomerans | 10.91±0.33 | 76.10% | b |

| Difenoconazole | 5.25±0.43 | 88.51% | a | |

| Control | 45.68±0.96 | d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).