Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain, Fungal Plant Pathogens and Seeds

2.2. Screening of Actinobacterias with Antagonistic Properties

2.4. Antifungal Activity In Vitro

2.5. VOCs-Mediated Antifungal Activity

2.3. Morphological and Culture Characterization

2.6. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.7. Production of Extracellular Enzymes and Biochemical Characterization

2.8. VOC-Mediated Plant Growth Promotion

2.9. Inoculation of Bell Pepper Plants with Streptomyces sp. PR69 and Phytophthora capsici

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

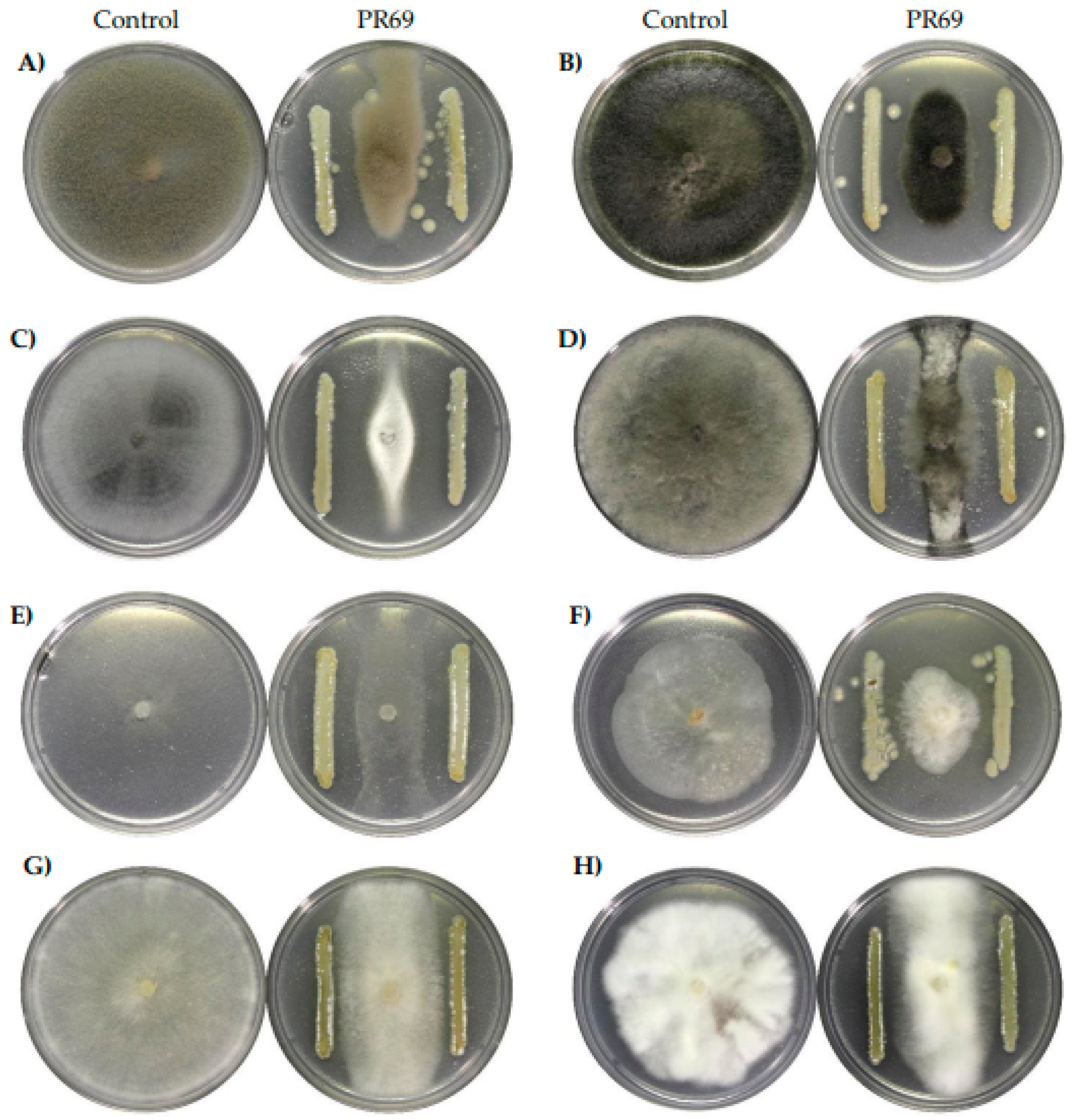

3.1. Antifungal Activity In Vitro

3.2. Media-Dependent Growth and Biomass Optimization of Strain PR69

3.3. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Bioinformatics Analysis

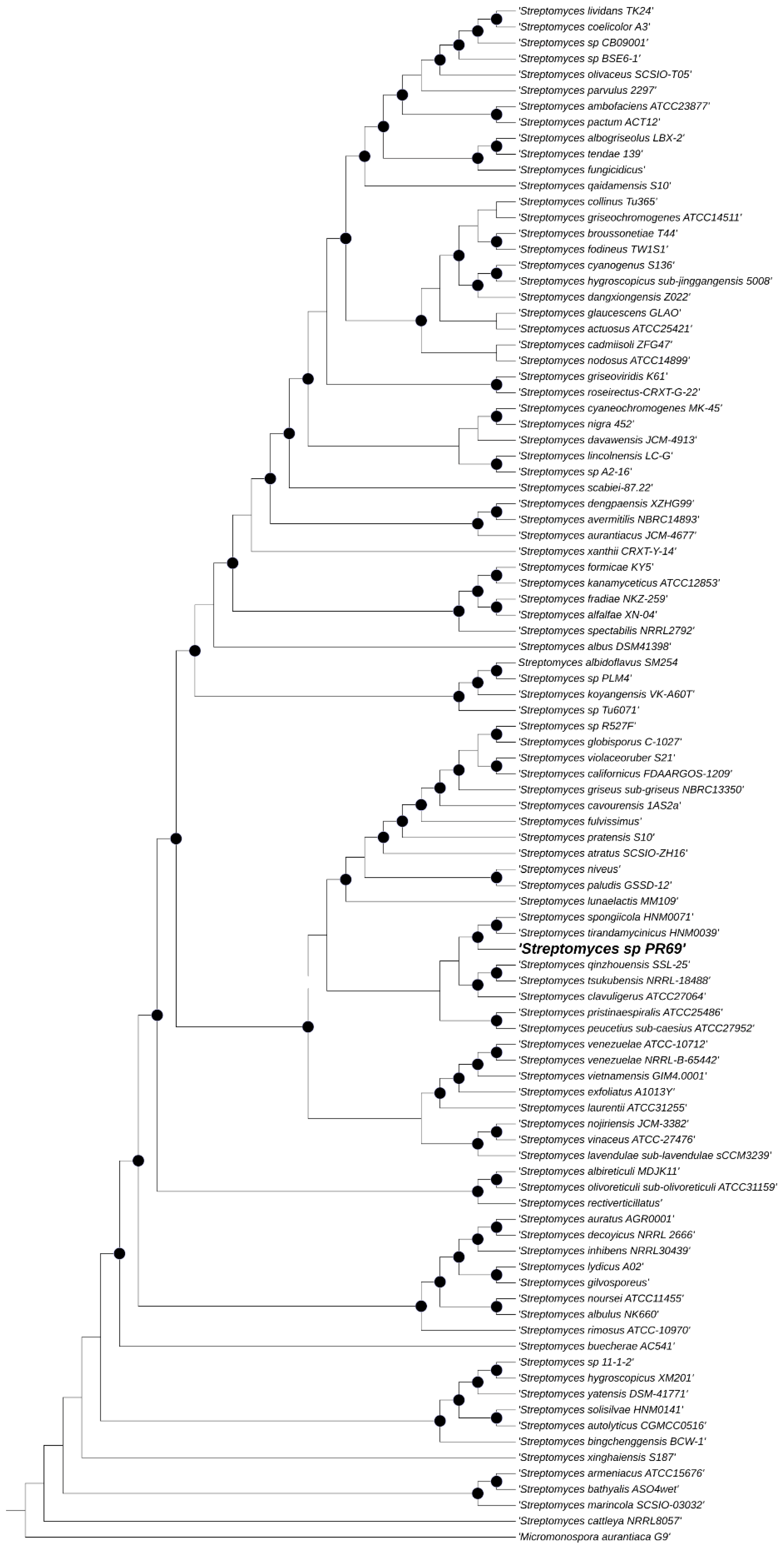

3.4. Production of Extracellular Enzymes and Biochemical Characterization

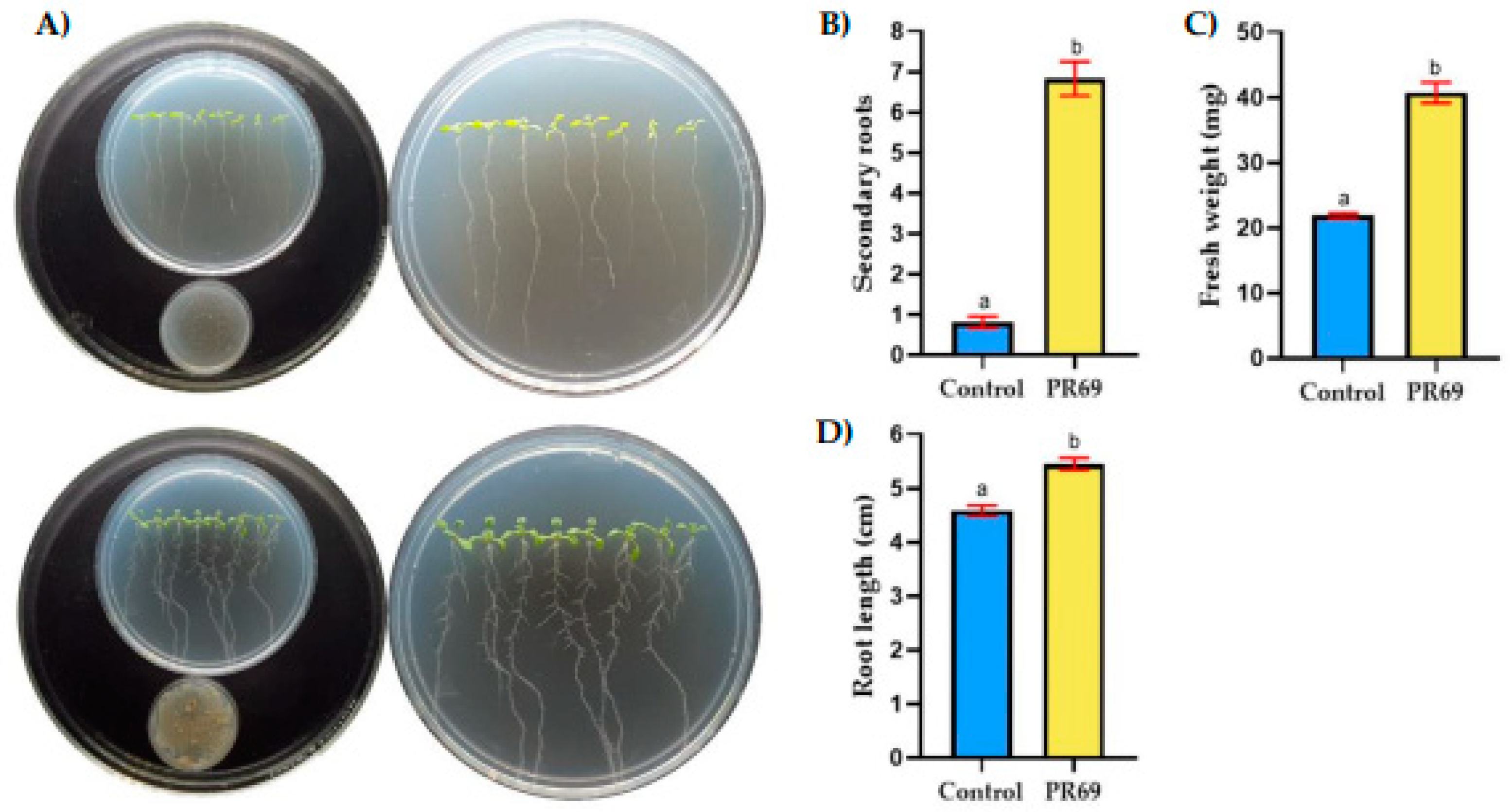

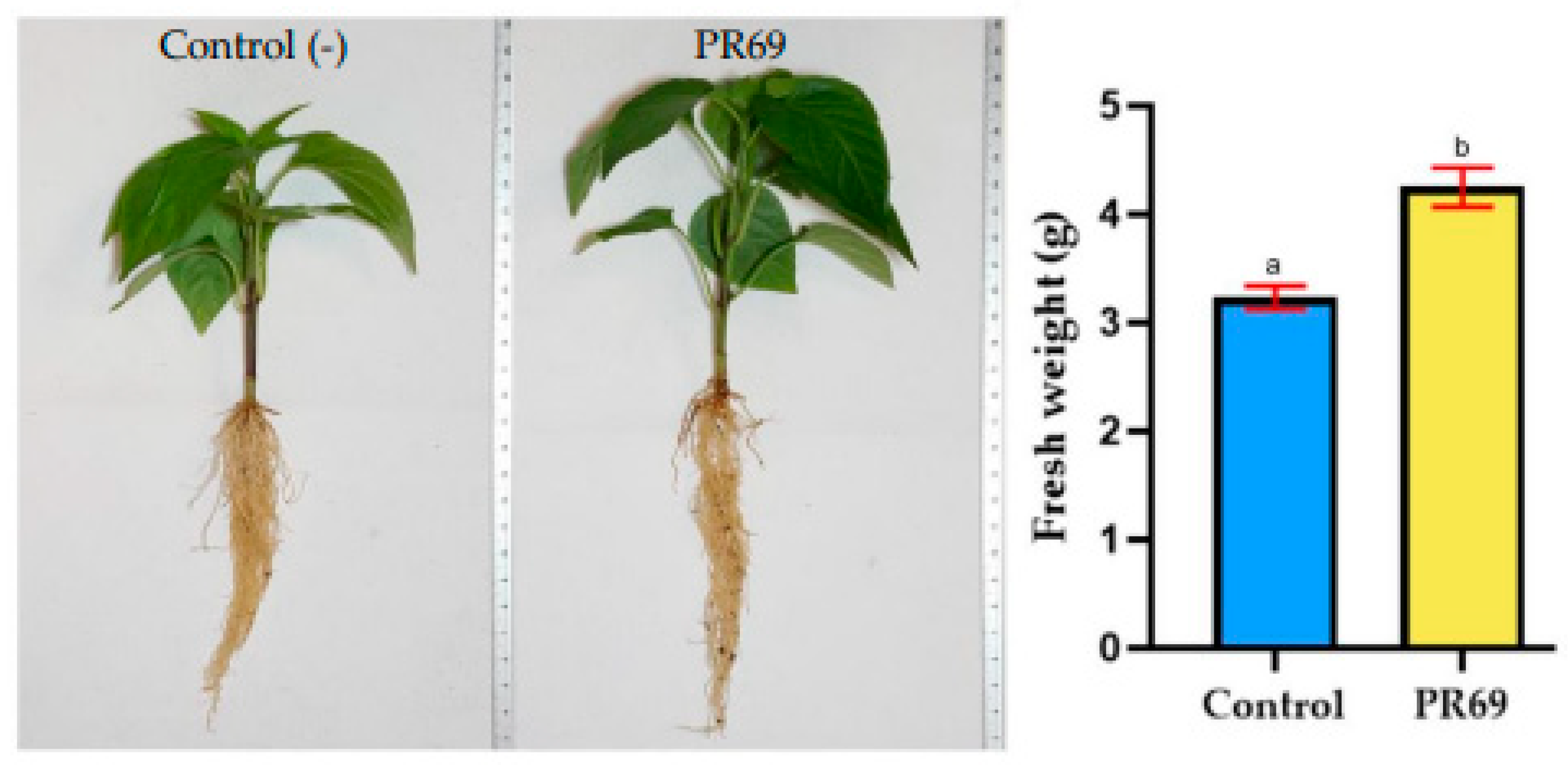

3.5. Effect of Streptomyces sp. PR69 on Arabidopsis thaliana Growth and Root Development

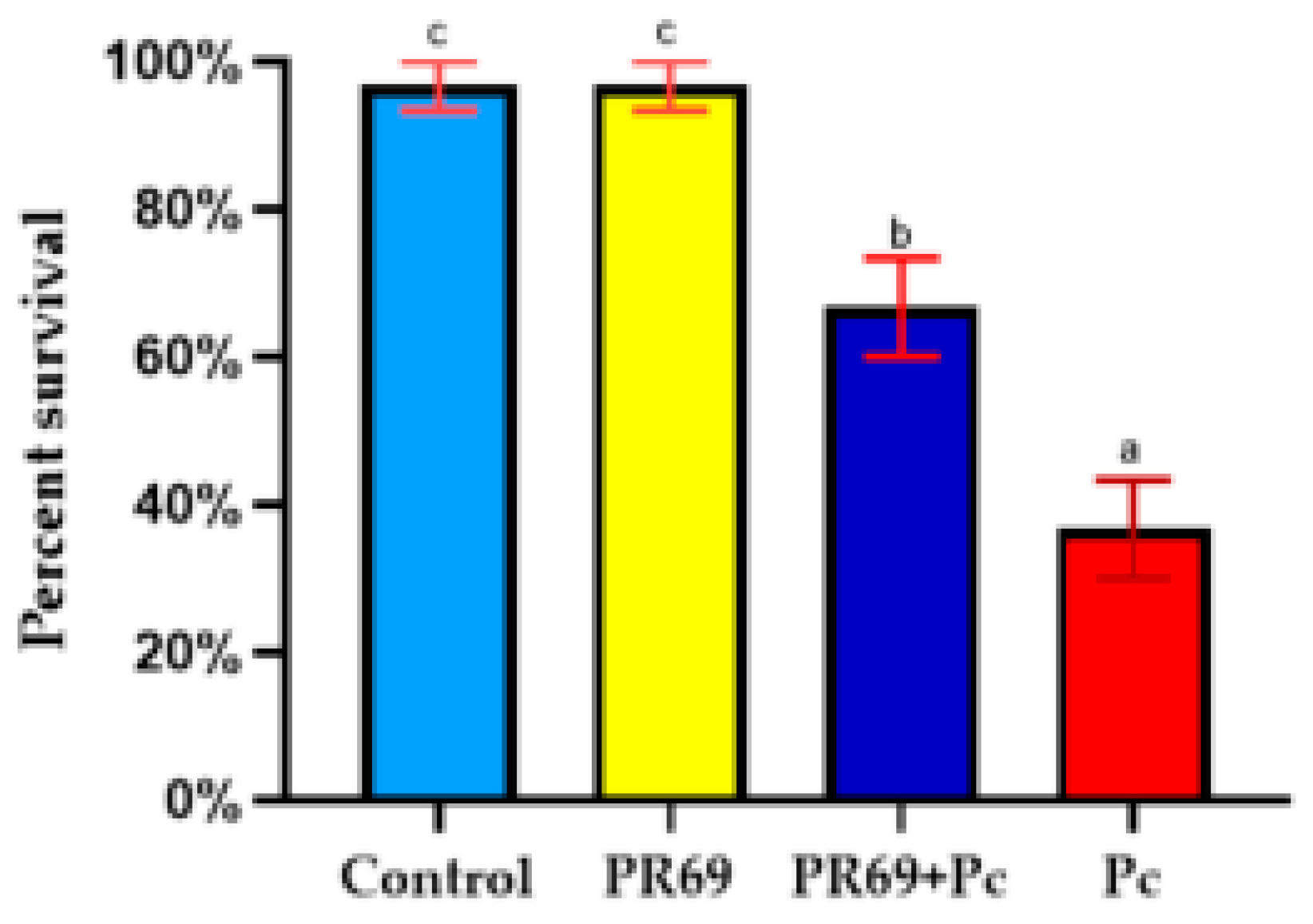

3.6. Biocontrol of P. capsici in Bell Pepper Plants by Streptomyces sp. PR69

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saltos, L.A.; Corozo-Quiñones, L.; Pacheco-Coello, R.; Santos-Ordóñez, E.; Monteros-Altamirano, Á.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R. Tissue specific colonization of Phytophthora capsici in Capsicum spp.: molecular insights over plant-pathogen interaction. Phytoparasitica 2021, 49, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Han, T.; Li, K.; Qu, Y.; Gao, Z. Differential Potential of Phytophthora capsici Resistance Mechanisms to the Fungicide Metalaxyl in Peppers. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 278. [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, T.B.; Hansen, Z.R. Sensitivity of Phytophthora capsici from Tennessee to Mefenoxam, Fluopicolide, Oxathiapiprolin, Dimethomorph, Mandipropamid, and Cyazofamid. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 3000-3007. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. What Socio-Economic and Political Factors Lead to Global Pesticide Dependence? A Critical Review from a Social Science Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Bonaterra, A.; Badosa, E.; Daranas, N.; Francés, J.; Roselló, G.; Montesinos, E. Bacteria as Biological Control Agents of Plant Diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1759. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, A.; Malannavar, A.B.; Salwan, R. Molecular aspects of biocontrol species of Streptomyces in agricultural crops. In Molecular Aspects of Plant Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture, Sharma, V., Salwan, R., Al-Ani, L.K.T., Eds.; Elsevier: 2020; pp. 89-109.

- Sivakala, K.K.; Gutiérrez-García, K.; Jose, P.A.; Thinesh, T.; Anandham, R.; Barona-Gómez, F.; Sivakumar, N. Desert Environments Facilitate Unique Evolution of Biosynthetic Potential in Streptomyces. Molecules 2021, 26, 588. [CrossRef]

- Arocha-Garza, H.F.; Canales-Del Castillo, R.; Eguiarte, L.E.; Souza, V.; De la Torre-Zavala, S. High diversity and suggested endemicity of culturable Actinobacteria in an extremely oligotrophic desert oasis. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3247. [CrossRef]

- Liotti, R.G.; da Silva Figueiredo, M.I.; Soares, M.A. Streptomyces griseocarneus R132 controls phytopathogens and promotes growth of pepper (Capsicum annuum). Biological Control 2019, 138, 104065. [CrossRef]

- Cordovez, V.; Carrion, V.J.; Etalo, D.W.; Mumm, R.; Zhu, H.; van Wezel, G.P.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Diversity and functions of volatile organic compounds produced by Streptomyces from a disease-suppressive soil. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 6, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Na, S.-I.; Kim, D.; Chun, J. UBCG2: Up-to-date bacterial core genes and pipeline for phylogenomic analysis. Journal of Microbiology 2021, 59, 609-615. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Ha, S.-m.; Lim, J.; Kwon, S.; Chun, J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 1281-1286. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Konstantinidis, K.T. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ Preprints 2016, 4, e1900v1901. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: a database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D801-D807. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 75. [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, W46-W50. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Lechuga, E.G.; Quintero Zapata, I.; Arévalo Niño, K. Detection of extracellular enzymatic activity in microorganisms isolated from waste vegetable oil contaminated soil using plate methodologies. African Journal of Biotechnology 2016, 15, 408-416. [CrossRef]

- Mun, B.G.; Lee, W.H.; Kang, S.M.; Lee, S.U.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Shahid, M.; Yun, B.W.; Lee, I.J. Streptomyces sp. LH 4 promotes plant growth and resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in cucumber via modulation of enzymatic and defense pathways. Plant and Soil 2020, 448, 87-103. [CrossRef]

- Joe, S.; Sarojini, S. An Efficient Method of Production of Colloidal Chitin for Enumeration of Chitinase Producing Bacteria. Mapana - Journal of Sciences 2017, 16, 37-45. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.-P.; Xu, J.-G. A simple double-layered chrome azurol S agar (SD-CASA) plate assay to optimize the production of siderophores by a potential biocontrol agent Bacillus. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2011, 5. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Safaie, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Shamsbakhsh, M. Streptomyces Strains Induce Resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. Lycopersici Race 3 in Tomato through Different Molecular Mechanisms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.; Moreno-Letelier, A.; Travisano, M.; Alcaraz, L.D.; Olmedo, G.; Eguiarte, L.E. The lost world of cuatro ciénegas basin, a relictual bacterial niche in a desert oasis. eLife 2018, 7, e38278. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.H.; Naing, K.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Tindwa, H.; Lee, G.H.; Jeong, B.K.; Ro, H.M.; Kim, S.J.; Jung, W.J.; Kim, K.Y. Biocontrol potential of streptomyces griseus H7602 against root rot disease (Phytophthora capsici) in pepper. Plant Pathology Journal 2012, 28, 282-289. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Safaie, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Shamsbakhsh, M. Tissue-specific synergistic bio-priming of pepper by two streptomyces species against phytophthora capsici. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230531. [CrossRef]

- Trinidad-Cruz, J.R.; Rincón-Enríquez, G.; Evangelista-Martínez, Z.; Quiñones-Aguilar, E.E. Control biorracional de Phytophthora capsici en plantas de chile mediante Streptomyces spp. Revista Chapingo Serie Horticultura 2021, 27, 85-99. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.J.; Wang, J.H.; Bu, X.L.; Yu, H.L.; Li, P.; Ou, H.Y.; He, Y.; Xu, F.D.; Hu, X.Y.; Zhu, X.M.; et al. Deciphering the streamlined genome of Streptomyces xiamenensis 318 as the producer of the anti-fibrotic drug candidate xiamenmycin. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 18977. [CrossRef]

- Caicedo-Montoya, C.; Manzo-Ruiz, M.; Ríos-Estepa, R. Pan-Genome of the Genus Streptomyces and Prioritization of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters With Potential to Produce Antibiotic Compounds. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zaburannyi, N.; Rabyk, M.; Ostash, B.; Fedorenko, V.; Luzhetskyy, A. Insights into naturally minimised Streptomyces albus J1074 genome. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 97. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Kaur, R.; Salwan, R. Streptomyces: host for refactoring of diverse bioactive secondary metabolites. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 340. [CrossRef]

- Weissman, J.L.; Fagan, W.F.; Johnson, P.L.F. Linking high GC content to the repair of double strand breaks in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Genetics 2019, 15, e1008493. [CrossRef]

- Lacey, H.J.; Rutledge, P.J. Recently Discovered Secondary Metabolites from Streptomyces Species. Molecules 2022, 27, 887. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kong, F.; Zhou, S.; Huang, D.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, W. Streptomyces tirandamycinicus sp. Nov., a novel marine sponge-derived actinobacterium with antibacterial potential against streptococcus agalactiae. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xiao, K.; Huang, D.; Wu, W.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W.; Huang, X. Complete genome sequence of Streptomyces spongiicola HNM0071 T , a marine sponge-associated actinomycete producing staurosporine and echinomycin. Marine Genomics 2019, 43, 61-64. [CrossRef]

- Jakubiec-Krzesniak, K.; Rajnisz-Mateusiak, A.; Guspiel, A.; Ziemska, J.; Solecka, J. Secondary metabolites of actinomycetes and their antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties. Polish Journal of Microbiology 2018, 67, 259-272. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Luo, Y. Recent Advances in Silent Gene Cluster Activation in Streptomyces. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.S.; Wan, P.K.; Kondo, A.; Chang, J.S.; Lan, J.C.W. Production and Recovery of Ectoine: A Review of Current State and Future Prospects. Processes 2023, 11, 339. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Soltani, B.M.; Nekouei, M.K.; Jouzani, G.S.; Mirzaei, H.H.; Sadeghizadeh, M. Diversity of the ectoines biosynthesis genes in the salt tolerant Streptomyces and evidence for inductive effect of ectoines on their accumulation. Microbiological Research 2014, 169, 699-708. [CrossRef]

- Pavan, M.E.; López, N.I.; Pettinari, M.J. Melanin biosynthesis in bacteria, regulation and production perspectives. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2020, 104, 1357-1370. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J.R.; Flärdh, K. Signals and regulators that govern Streptomyces development. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2012, 36, 206-231. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; He, X.; Cane, D.E. Biosynthesis of the earthy odorant geosmin by a bifunctional Streptomyces coelicolor enzyme. Nature Chemical Biology 2007, 3, 711-715. [CrossRef]

- Becher, P.G.; Verschut, V.; Bibb, M.J.; Bush, M.J.; Molnár, B.P.; Barane, E.; Al-Bassam, M.M.; Chandra, G.; Song, L.; Challis, G.L.; et al. Developmentally regulated volatiles geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol attract a soil arthropod to Streptomyces bacteria promoting spore dispersal. Nature Microbiology 2020, 5, 821-829. [CrossRef]

- Churro, C.; Semedo-Aguiar, A.P.; Silva, A.D.; Pereira-Leal, J.B.; Leite, R.B. A novel cyanobacterial geosmin producer, revising GeoA distribution and dispersion patterns in Bacteria. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 8679. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Corral, D.A.; Ornelas-Paz, J.d.J.; Olivas, G.I.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.H.; Salas-Marina, M.Á.; Berlanga-Reyes, D.I.; Sepulveda, D.R.; de León, Y.M.P.; Rios-Velasco, C. Growth Promotion of Phaseolus vulgaris and Arabidopsis thaliana Seedlings by Streptomycetes Volatile Compounds. Plants 2022, 11, 875. [CrossRef]

- Dotson, B.R.; Verschut, V.; Flärdh, K.; Becher, P.G.; Rasmusson, A.G. The Streptomyces volatile 3-octanone alters auxin/cytokinin and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana via the gene family KISS ME DEADLY. bioRxiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Strock, C.F.; Lynch, J.P. Root secondary growth: an unexplored component of soil resource acquisition. Annals of Botany 2020, 126, 205-218. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.A.d.J.; Olivares, F.L. Plant growth promotion by streptomycetes: ecophysiology, mechanisms and applications. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 2016, 3, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, P.; Das, P.; Solanki, R.; Kapur, M.K. Proactive role of Streptomyces spp. in plant growth stimulation and management of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 19, 10457-10476. [CrossRef]

- Cocking, E.C. Helping plants get more nitrogen from the air. European Review 2000, 8, 193-200. [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. Bacterial Siderophores: Classification, Biosynthesis, Perspectives of Use in Agriculture. Plants 2022, 11, 3065. [CrossRef]

- Swarnalatha, G.V.; Goudar, V.; Gari Surendranatha Reddy, E.C.R.; Al Tawaha, A.R.M.; Sayyed, R.Z. Siderophores and Their Applications in Sustainable Management of Plant Diseases. In Secondary Metabolites and Volatiles of PGPR in Plant-Growth Promotion, Sayyed, R.Z., Uarrota, V.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 289-302.

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, P.C.; Tsay, T.T. The biocontrol efficacy and antibiotic activity of Streptomyces plicatus on the oomycete Phytophthora capsici. Biological Control 2016, 98, 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Álvarez, R.; Botas, A.; Albillos, S.M.; Rumbero, A.; Martín, J.F.; Liras, P. Molecular genetics of naringenin biosynthesis, a typical plant secondary metabolite produced by Streptomyces clavuligerus. Microbial Cell Factories 2015, 14, 178. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Zucca, P.; Pezzani, R.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. The therapeutic potential of naringenin: A review of clinical trials. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 11. [CrossRef]

- Soberón, J.R.; Sgariglia, M.A.; Carabajal Torrez, J.A.; Aguilar, F.A.; Pero, E.J.I.; Sampietro, D.A.; Fernández de Luco, J.; Labadie, G.R. Antifungal activity and toxicity studies of flavanones isolated from Tessaria dodoneifolia aerial parts. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05174. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Peng, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, W. Isolation and Evaluation of Rhizosphere Actinomycetes With Potential Application for Biocontrolling Fusarium Wilt of Banana Caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense Tropical Race 4. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

| % Inhibition | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pc1 | Cc2 | Mp3 | Fl4 | Br5 | Fs6 | Bc7 | Fo8 | ||

| Isolate PR69 |

71.09±0.18 | 73.63±0.16 | 63.92±0.19 | 52.59±0.12 | 65.46±0.10 | 50.43±0.31 | 69.76±0.13 | 44.85±0.29 | |

| Feature | |

|---|---|

| Contigs | 105 |

| Genome lenght | 6,570,163bp |

| G+C % | 71.51 |

| Contig L50 | 12 |

| ContigN50 | 186,895 |

| CDS | 5,956 |

| tRNA | 63 |

| rRNA | 4 |

| Protein with functional assignments | 3,898 |

| Antibiotic Resistance (source CARD, NDARO,PATRIC) |

43 |

| Type | From-To (location) |

Most similar known cluster | Similarity% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Type | ||||

| Ectoine | 324,766 - 335,164 | Ectoine | Other | 100 | |

| Melanin | 85,744 - 96,241 | Melanin | Other | 100 | |

| Terpene | 223,129 - 244,059 | Geosmin | Terpene | 100 | |

| T3PKS | 1 - 39,280 | Naringenin | Polyketide:Type III polyketide | 100 | |

| Lanthipeptide-class-iii | 28,816 - 51,518 | SapB | RiPP:Lanthipeptide | 100 | |

| Terpene | 1 - 16,602 | Pristinol | Terpene | 100 | |

| NRPS-like,NRPS | 1 - 28,694 | Antipain | NRP | 83 | |

| NRP-metallophore,NRPS,redox-cofactor | 278,062 - 337,959 | Mirubactin | NRP | 78 | |

| Terpene | 263,573 - 290,198 | Hopene | Terpene | 76 | |

| Melanin | 101,546 - 111,953 | Grixazone A | Terpene | 61 | |

| NRP-metallophore,NRPS,T1PKS | 160,886 - 250,379 | Peucechelin | NRP | 55 | |

| T1PKS,T2PKS,RiPP-like | 160,514 - 249,283 | Xantholipin | Polyketide | 51 | |

| NRPS | 1 - 37,748 | Netropsin | NRP | 40 | |

| Phenazine | 20,316 - 40,780 | Endophenazine A/endophenazine B | Other:Phenazine | 33 | |

| Melanin | 170,575 - 180,985 | Melanin | Other | 28 | |

| T3PKS,NRPS | 79,735 - 109,902 | Totopotensamide A/totopotensamide B | NRP+Polyketide | 28 | |

| NRPS,NRPS-like | 1 - 36,960 | Disgocidine/distamycin/congocidine | NRP | 28 | |

| NRPS-like | 12,279 - 53,110 | Lipstatin | NRP | 21 | |

| Terpene | 24,797 - 46,026 | Legonindolizidine A6 | NRP+Alkaloid | 12 | |

| NI-siderophore | 132,640 - 147,396 | Synechobactin C9/ C11/ 13/ 14/ 16/ A/ B/ C | Other | 9 | |

| NRPS-like | 43,673 - 85,050 | Chejuenolide A/chejuenolide B | Polyketide | 7 | |

| RiPP-like | 151,678 - 160,095 | Hexacosalactone A | Other | 4 | |

| NRPS-like | 109,671 - 132,257 | Sanglifehrin A | NRP+Polyketide | 4 | |

| Thioamitides | 1 - 13,147 | Prejadomycin/rabelomycin/gauDimycin C/gaudimycin D/UWM6/gaudimycin A | Polyketide:Type II polyketide+Saccharide:Hybrid/tailoring saccharide | 4 | |

| Other | 90,844 - 113,876 | A-503083 A/A-503083 B/A-503083 E/A-503083 F | NRP | 3 | |

| Terpene | 54,693 - 71,392 | Bombyxamycin A/bombyxamycin B | Polyketide | 3 | |

| CDPS | 66,910 - 87,659 | ||||

| Indole | 1 -19,239 | ||||

| Characteristics | Streptomyces sp. PR69 |

|---|---|

| Cellulase | - |

| Protease | - |

| Chitinase | - |

| Lipase | + |

| Siderophores | + |

| Nitrogen fixation | + |

| Phosphate solubilization | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).