1. Introduction

According to FAOSTAT (2016), China has become the largest consumer of chemical fertilizers worldwide. The application of nitrogen fertilizer in China accounts for 30% of the worldwide total; however, the utilization rate is only about 35% [

1,

2]. For example, the nitrogen application rate in Chinese apple orchards is approximately 400–600 kg·hm⁻², which is substantially higher than that in other countries [

3,

4]. Moreover, previous studies have indicated that many orchards primarily rely on chemical fertilizers with limited organic inputs [

5,

6]. This unbalanced fertilization practice leads to resource wastage and contributes to a range of soil pollution issues [

7,

8].

Furthermore, the application of livestock and poultry manure is considered an environmentally sustainable agricultural practice, and many fruit growers prefer manure over commercial fertilizers [

9,

10]. However, the long-term application of manure can elevate the concentrations of toxic heavy metals such as Hg, Cu, Zn, and Cr and may lead to the accumulation of allelochemicals [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Allelopathy is the phenomenon where an organism produces biochemicals that influence the growth, development, and reproduction of itself as well as neighboring plants. It is considered an indirect cause of continuous cropping obstacles in agriculture [

16,

17]. Allelopathic effects are primarily attributed to allelochemicals, such as secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, phenolic compounds, fatty acids, alkanes, and terpenoids. Therefore, analyzing the allelochemical varieties and their effects on plant growth is of great importance.

Pears are one of the most important economic fruit crops worldwide. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [

18], China accounts for 67.3% of the worldwide pear cultivation area. The “Dangshansuli” pear, a local cultivar in Dangshan County, Anhui Province, has a cultivation history of more than 200 years and is renowned for its juiciness, pleasant flavor, and sweet aroma. Currently, the “Dangshansuli” pear represents one-quarter of China’s total pear production ]19]. However, the widespread misuse of fertilizers has resulted in altered soil physicochemical properties and a series of soil-related issues [

20]. Despite this, the long-term effects of fertilization on the soil in “Dangshansuli” pear orchards remain poorly understood.

This study investigated the effects of long-term fertilization on the mineral elements, heavy metals, and compound content in the different soil layers and then aimed to explore the scientific fertilization principles for “Dangshansuli” pear orchards. We hypothesized that long-term inefficient fertilization results in soil acidification, soil structure deterioration, and the excessive accumulation of heavy metals. To evaluate this hypothesis, we analyzed the soil physical and chemical properties across different soil layers, using samples from a “Dangshansuli” pear orchard that had received long-term fertilization and a control area that had been unfertilized for more than 30 years. Understanding the impact of long-term fertilization on the soil properties will aid in developing optimal fertilization strategies for the sustainable development of the “Dangshansuli” pear industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

The experiment was performed at the Dangshan County Fruit Germplasm Resource Garden (34°42′ N, 116°35′ E; 47.8 m above sea level) in Suzhou City, Anhui Province, China. The region experiences a monsoon-influenced humid subtropical climate, with a mean annual temperature of 14.1°C and mean annual precipitation of 743.3 mm. The primary fruit tree cultivated is the “Dangshansuli” pear, which accounts for 71.4% of the total fruit planting area.

2.2. Sample Collection and Physicochemical Property Analysis

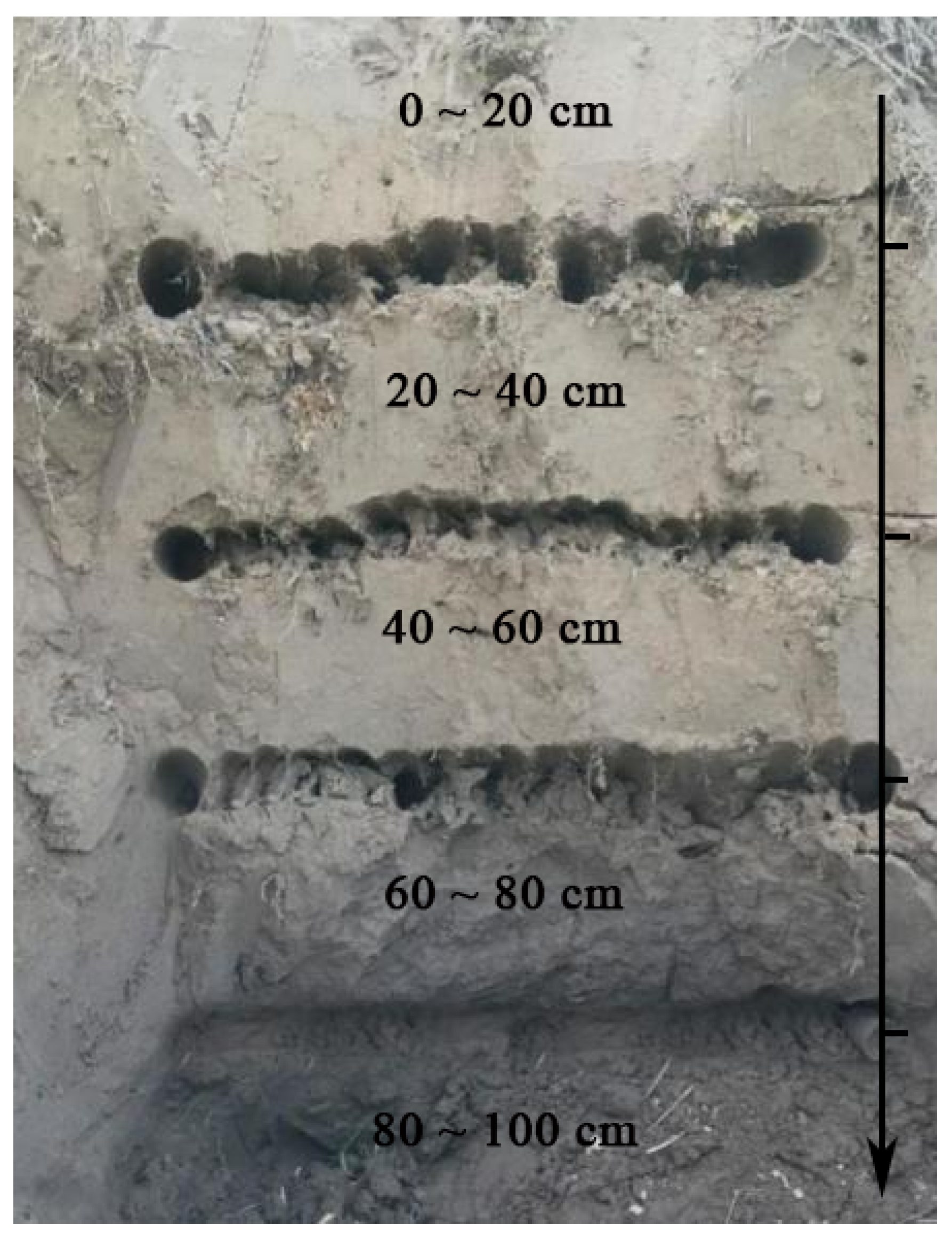

Soil sampling was performed in May 2020. The treatment group consisted of a “Dangshansuli” pear orchard that was subjected to long-term fertilization for 30 years, while an unfertilized area served as the control. Each treatment included three uniformly growing pear trees. Soil samples were collected from each tree using a five-point excavation method. A total of 1 kg of soil was collected from each of five depth layers: 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, 40–60 cm, 60–80 cm, and 80–100 cm (

Figure 1). The soil samples from the five points per tree were thoroughly mixed to form a composite sample, and each treatment included three biological replicates. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory, where 500 g of soil from each composite sample was air-dried and passed through a 60-mesh sieve for subsequent physical and chemical property analysis.

2.3. Soil pH and Mineral Element Determination

Soil pH was measured by potentiometry, with a soil-to-water ratio of 1:5. The soil organic matter content was determined using the potassium dichromate method with 1 g of naturally air-dried soil [

21]. Furthermore, the mineral element and heavy metal contents were analyzed at the Institute of Geological Experiment of Anhui Province.

2.4. Soil Organic Compounds Determination and Analysis

For the extraction of soil organic compounds, 50 g of soil was accurately weighed into a 250 mL triangular flask, to which 150 mL of ethyl acetate was added. The mixture was shaken overnight in an oscillating incubator at 25°C. The sample was then ultrasonicated for 1 h and kept in the dark for 24 h. The extract was then filtered through filter paper in a vacuum filtration system, and the process was repeated three times. The combined extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 40°C and passed through a 0.22-μm membrane filter [

22]. Analysis was performed using an Agilent 7890B gas chromatography system coupled with an Agilent 7000 mass spectrometer, and a 1 μL aliquot was injected via an Agilent autosampler. The column temperature was programmed as follows: initial temperature 50°C, increased to 280°C at a rate of 10°C/min, and held at 280°C for 15 min. The carrier gas was helium at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Electron ionization was applied with the following settings: interface temperature 250°C, ion source temperature 230°C, and quadrupole temperature 150°C. The mass scanning range was m/z 35–500 with a scan speed of 0.3 s per full scan.

2.5. Seeds Germination Assay

For the soil extract bioassay, 100 g of air-dried soil was used from each of the 30 samples. Fertilized and unfertilized soil samples were separately combined, placed in a triangular flask with 2 L of distilled water, and shaken overnight at 25°C. After full extraction, the mixture was filtered and concentrated to obtain a 1 g/mL extract. Moreover, Pyrus betulifolia Bunge seeds of uniform size and plumpness were selected for the germination tests. Each treatment included five replicates, with 25 seeds per replicate. The seeds were surface sterilized with 75% ethanol and rinsed three times with sterile water. The sterilized seeds were then placed in Petri dishes lined with filter paper, and 3 mL of the soil extract was added. The control group received the same volume of distilled water. All dishes were incubated in a climate-controlled chamber at 25 ± 2°C, and the extract was replenished daily. Seed germination was recorded daily for 7 days, and on the eighth day, the radicle and hypocotyl lengths were measured. The germination rate, germination potential, germination index, and vitality index were calculated as previously described by Toscano et al. (2017).

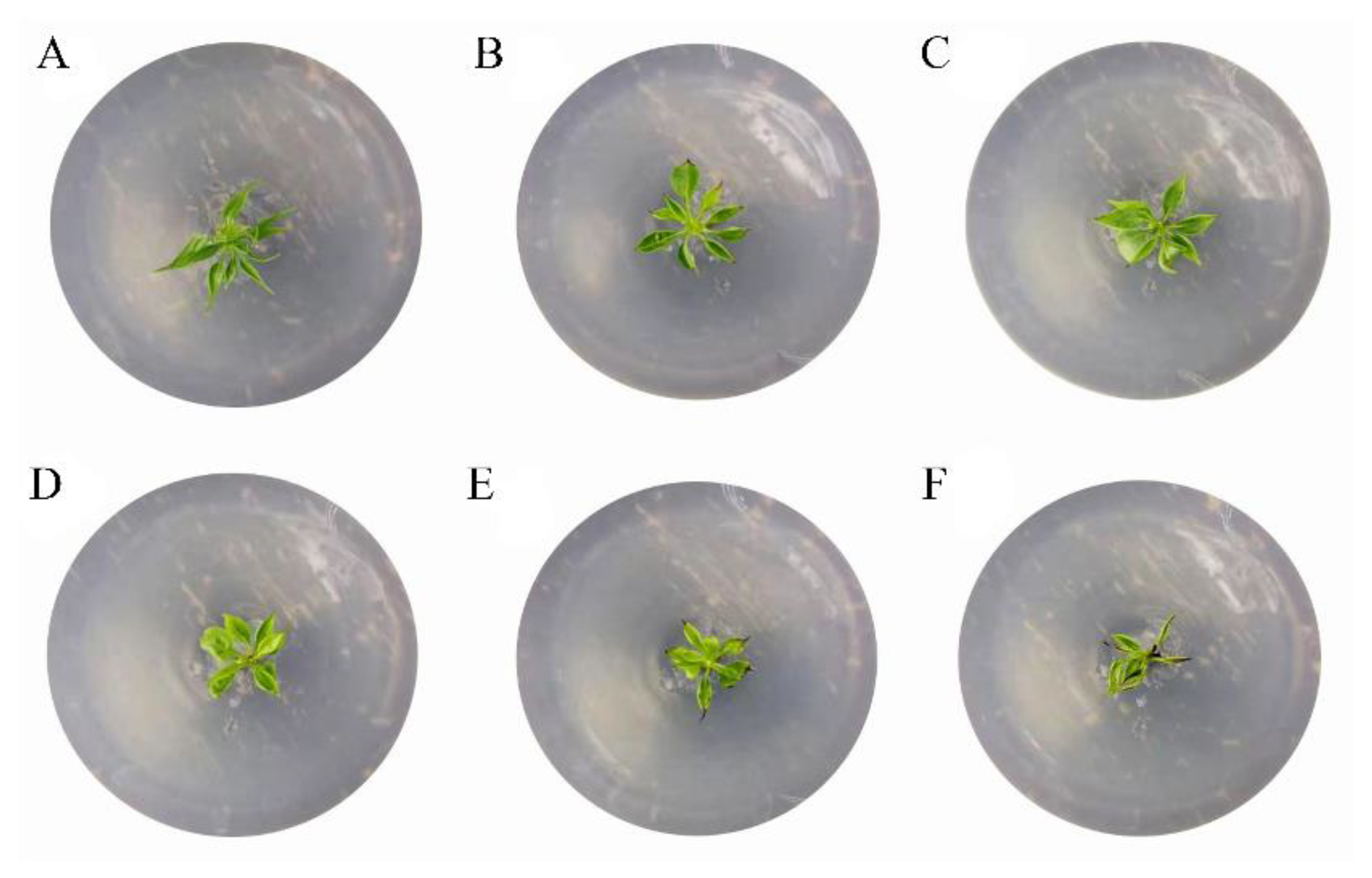

2.5. Allelopathy Assay on Pear Seedlings

For the exogenous stress experiment on “Shanli” (Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim) seedlings, uniformly grown tissue-cultured seedlings were selected. Thereafter, benzoic acid and octadecane were applied at concentrations of 0, 0.03, 0.06, 0.12, 0.18, and 0.30 mmol/L. These compounds were incorporated into MS (Murashige and Skoog) medium, and the seedlings were transferred to the respective media. Phenotypic observations were recorded on the seventh day.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data were compiled using Microsoft Excel and analyzed with SPSS software. Variance analysis was performed to evaluate the treatment effects. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) data were processed using the NIST2008 mass spectral library. Compounds with a similarity match greater than 80% were considered identified. The content of each compound was quantified using the internal standard method.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Soil pH and Organic Matter Following Fertilization in a “Dangshansuli” Pear Orchard

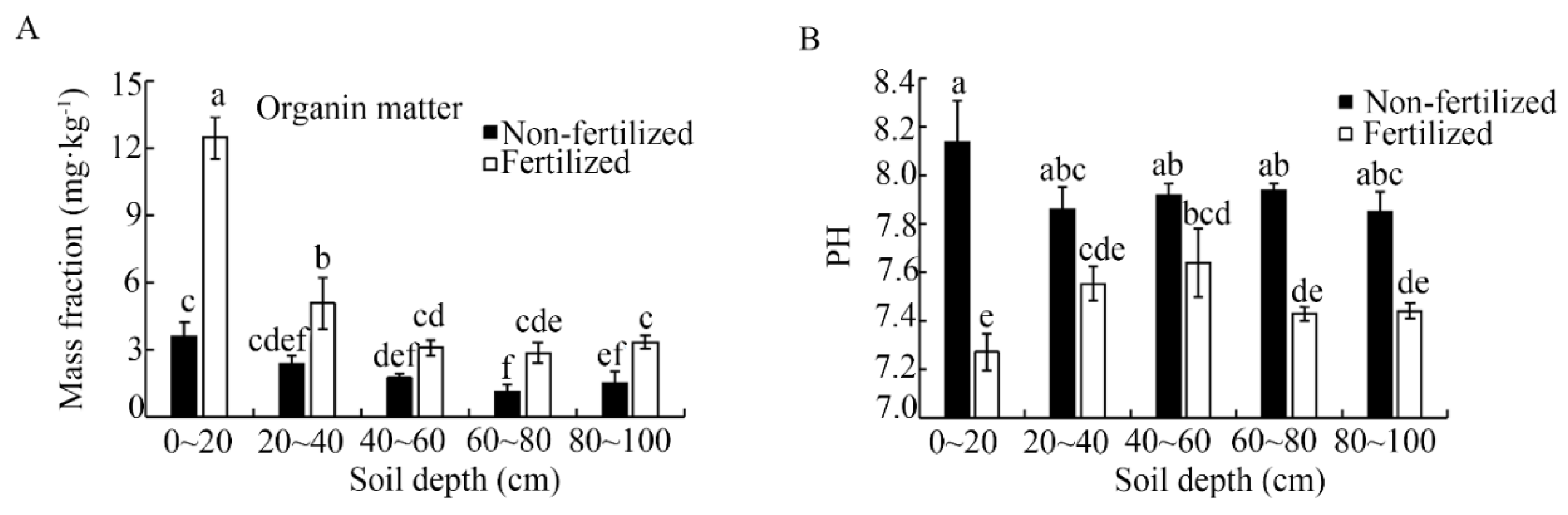

Soil organic matter consists largely of acidic compounds, and the contents thereof can directly influence the soil pH. Our results indicated that the organic matter content was higher in the soils subjected to long-term fertilization compared to that of unfertilized soils, particularly in the surface layer (0–20 cm) (

Figure 2A). Correspondingly, the soil pH decreased under long-term fertilization conditions, with the difference being most significant in the surface layer. In contrast, the soil pH and organic matter content exhibited no significant differences among soil layers in the unfertilized treatment control (

Figure 2B).

3.2. Changes in Soil Major and Medium Element Content with Fertilization

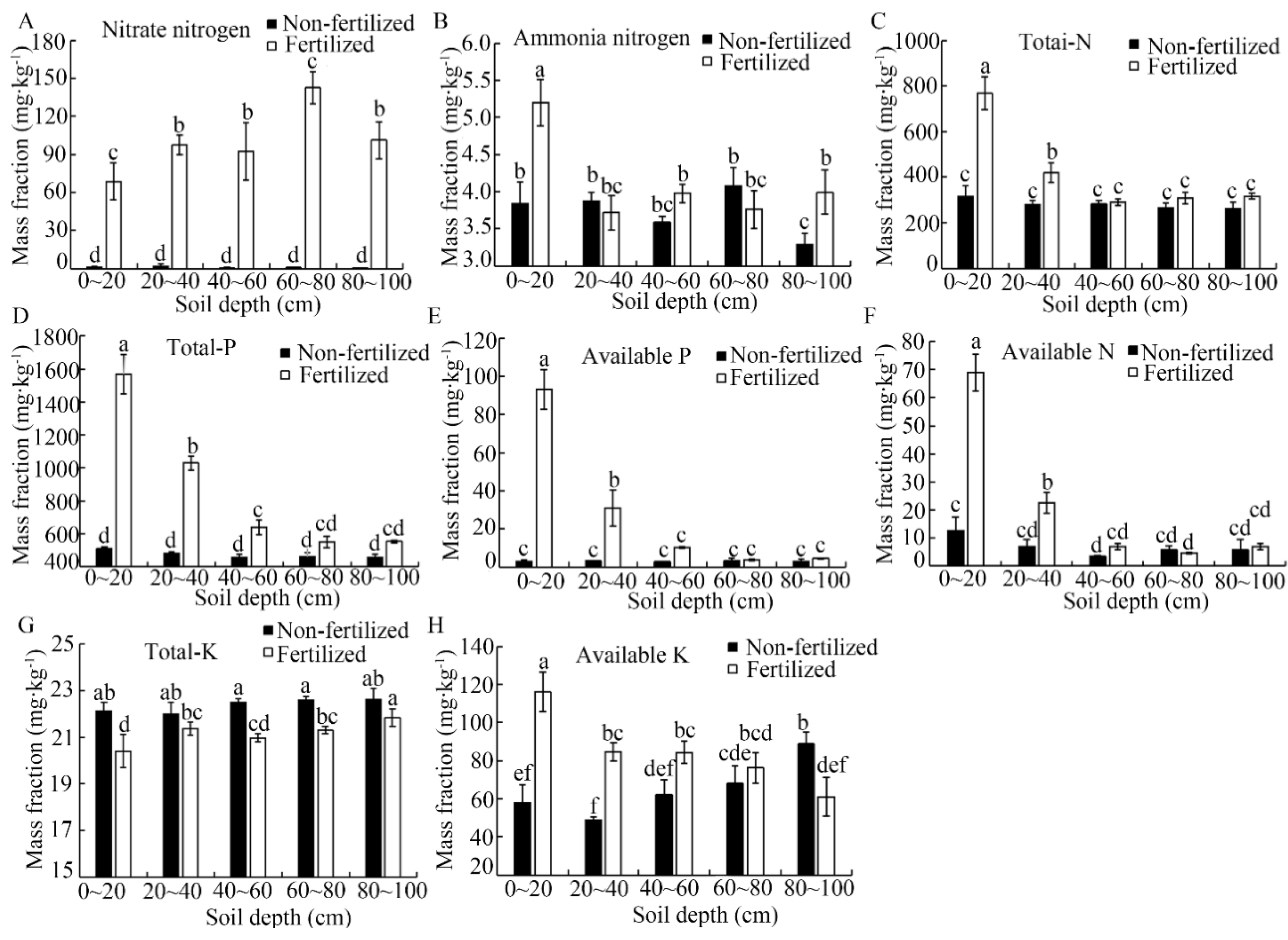

Soil NO

3⁻ content was significantly higher under long-term fertilization conditions than in the unfertilized control. Similarly, the NH₄⁺ content was significantly elevated in the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm soil layers under long-term fertilization, but no significant differences were observed in the deeper layers. The total and available nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) were also significantly higher in fertilized soils within the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers compared to unfertilized control soil (

Figure 3A–B), but no significant differences were observed for the deeper layers (

Figure 3C–D).

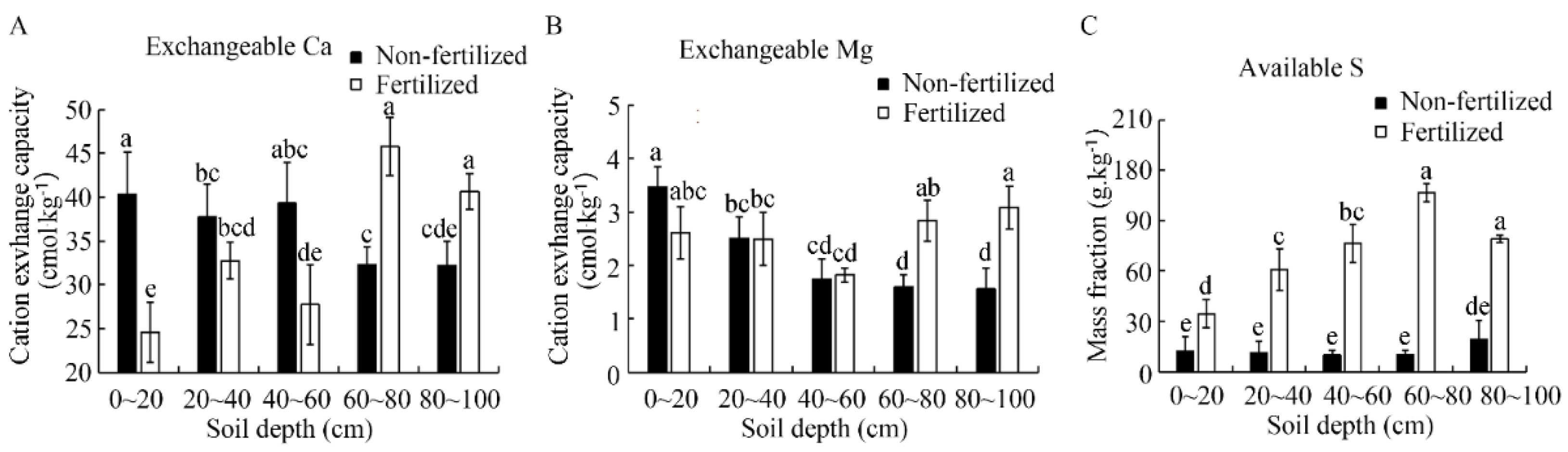

In contrast, total potassium (K) was lower in the fertilized soil than in the unfertilized control (

Figure 3E–F), whereas available K was significantly higher in the 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm layers under long-term fertilization conditions (

Figure 3G–H). With long-term fertilization, the exchangeable Ca and Mg were decreased in the 0–20 cm layer and were only significantly higher in deeper soil layers (60–80 cm and 80–100 cm) compared to unfertilized soil. As the soil depth increased, the available S content rose in fertilized soil and was significantly higher than that in the unfertilized control soil (

Figure 4F).

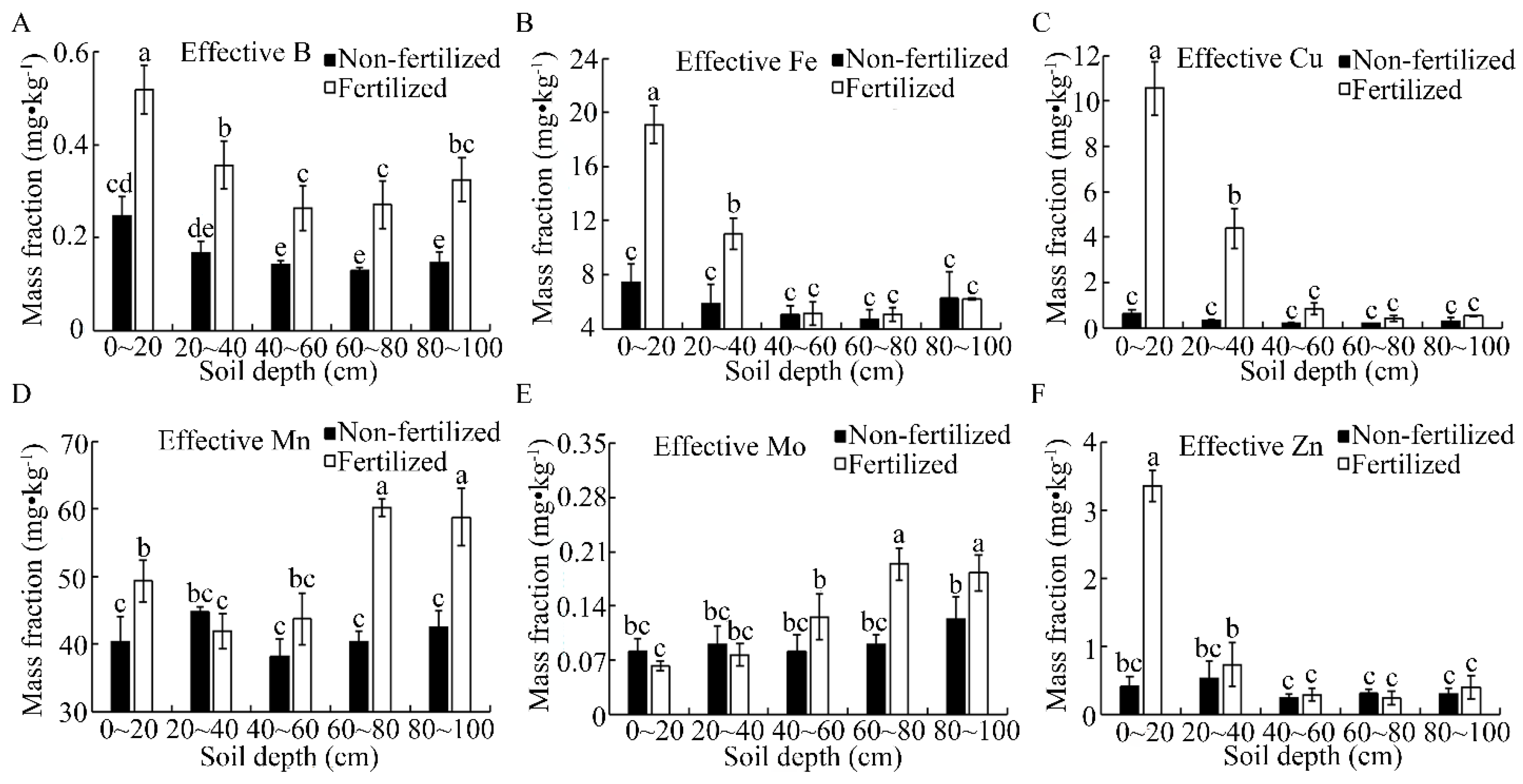

3.3. Trace Element Content Under Long-Term Fertilization

Trace elements are essential for normal plant growth, and their availability in soil can be altered through long-term fertilization practices. In this study, the content of available B was significantly higher under long-term fertilization conditions than in the unfertilized control across all soil layers (

Figure 5A). Similarly, available Fe and Cu were significantly elevated in the fertilized soil within the 0–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers, although no significant differences were observed in soil at deeper layers (

Figure 5B–C). The increase in available Fe and Cu in surface soils because of long-term fertilization may increase the potential risk of heavy metal accumulation.

In contrast, available Mn and Mo were significantly higher in soil under fertilization conditions only in the deeper soil layers (60–80 cm and 80–100 cm) compared to those of the unfertilized soil. In addition, available Zn was significantly greater in fertilized soil solely within the 0–20 cm layer, with no notable differences in the other depths.

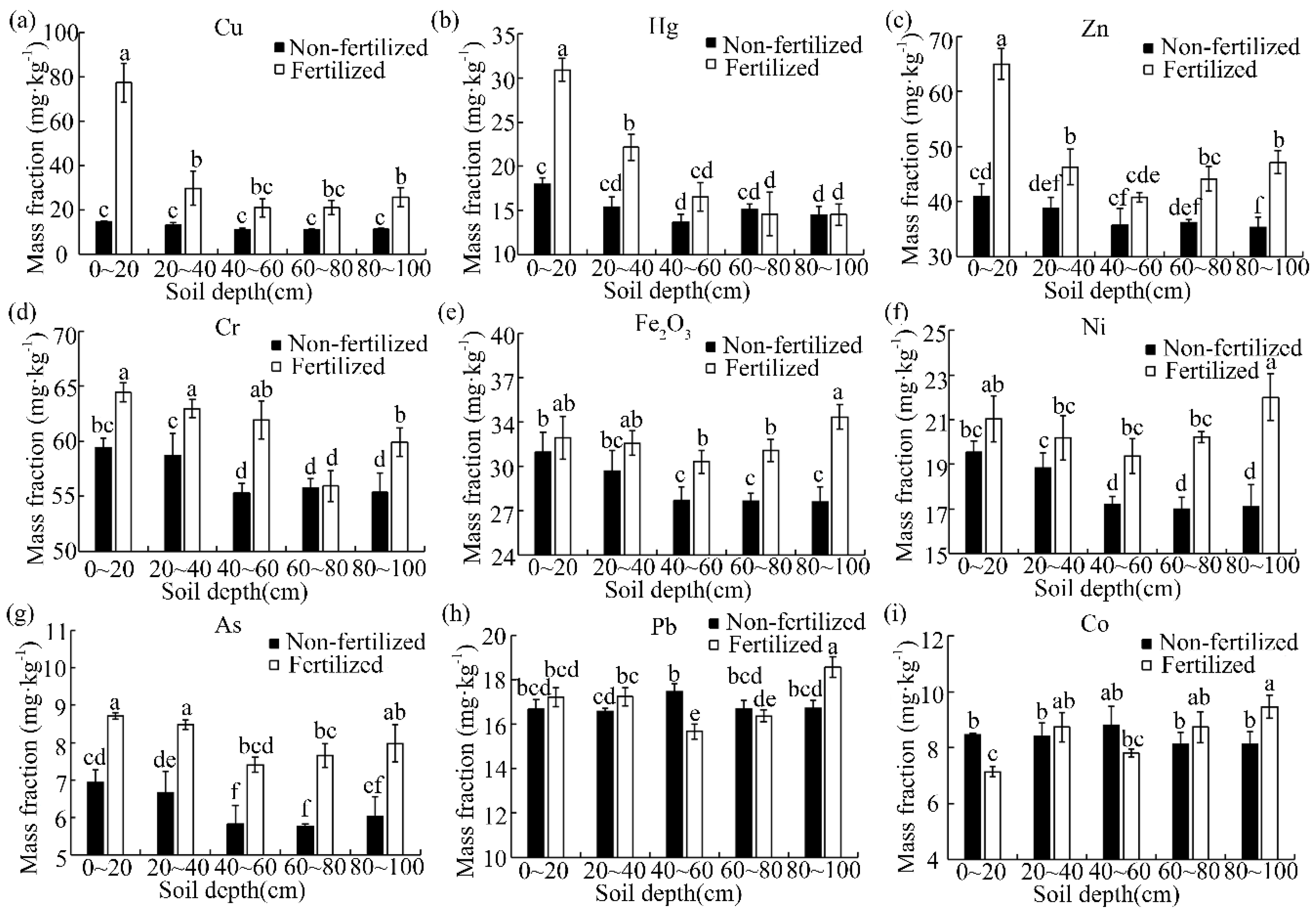

3.4. Soil Heavy Metal Content Under Long-Term Fertilization

Soil heavy metal pollution has become a pressing issue of increasing concern. Understanding the impact of long-term fertilization on heavy metal accumulation is crucial for guiding agricultural practices. Compared with the unfertilized soil, long-term fertilization resulted in elevated contents of Cu, Hg, Zn, Cr, Fe₂O₃, Ni, and As (

Figure 6A–G). Notably, in the 0–20 cm layer, the contents of Cu, Hg, Zn, Cr, and As were significantly higher than those in the control, but they all remained within China’s soil environmental standards. In contrast, no marked changes were observed in Pb and Co content under long-term fertilization, with their levels remaining similar to those of the unfertilized soil across all layers (

Figure 6H–I).

3.5. Soil Compound Profiles in the Fertilized and Unfertilized Soil Layers

Fertilization supplies essential minerals for plant growth but also alters the soil chemical composition. Compared with the unfertilized soil, long-term fertilization increased the diversity and content of the soil compounds, particularly alkanes (

Table S1, S2). To further investigate the phytotoxic effects, we selected two compounds detected in the fertilized soil, benzaldehyde and octadecanoic acid, and evaluated their impact on pear seedling growth. Based on their measured soil concentrations, we designed five gradient levels for each compound. After seven days of tissue culture, only octadecanoic acid exhibited an allelopathic inhibitory effect. At 0.06 mmol·L⁻¹ and 0.12 mmol·L⁻¹, the pear seedlings displayed symptoms such as leaf yellowing and curling compared with those of the control (

Figure 7A–D). At 0.18 mmol·L⁻¹, the leaf tips exhibited pronounced blackening accompanied by slight yellowing in the middle portion of the leaves (

Figure 7E). When the concentration increased to 0.30 mmol·L⁻¹, the leaves were severely shriveled, and some had turned completely black (

Figure 7F).

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Soil Physicochemical Characteristics Under Long-Term Fertilization

The influence of fertilization on soil physicochemical properties is known to vary considerably depending on climatic and site-specific conditions [

23,

24]. In this study, the long-term fertilization conditions significantly improved the soil physicochemical characteristics. Specifically, it resulted in a higher soil organic matter content and a lower pH in the 0–20 cm layer, which aligns with previous findings [

25,

26]. Furthermore, the total nitrogen and phosphorus, alkaline hydrolyzable nitrogen, and available phosphorus contents were significantly increased in the 0–40 cm soil depth of the Dangshan orchard. In contrast, the total and available potassium only increased moderately, while the exchangeable calcium and magnesium ions were lower in the surface layer compared to those of the unfertilized soil. This may be attributed to the long-term application of nitrogen or potassium fertilizers, which increases the NH₄⁺ and K⁺ concentrations. NH₄⁺ nitrification releases H⁺ into the soil, and excess K⁺ and H⁺ can displace Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ from soil colloids, thereby ultimately reducing the levels of exchangeable calcium and magnesium ions [

25,

27].

4.2. Influence of Soil Trace Elements Under Long-Term Fertilization

The availability of trace elements is often influenced by the soil pH. In this study, the available Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn, and B in the 0–40 cm depth of the fertilized soil were significantly higher than in the unfertilized soil. The available Cu content exceeded twice the optimal level for plant growth, which may be related to the lower soil pH [

25,

28]. However, the available Fe content in the fertilized 20–40 cm layer was only 11 mg·kg⁻¹, and this deficiency may be one reason for the persistent Fe chlorosis observed in the pear tree leaves in Dangshan County.

4.3. Influence of Soil Heavy Metals Under Long-Term Fertilization

Previous studies have indicated that long-term fertilization can result in the accumulation of heavy metals in the soil [

14,

26]. Consistent with these reports, our results revealed that the Cu and Hg contents were significantly elevated in the 0–20 cm surface layer of the fertilized soil. Heavy metals such as Ni, Cr, As, and Mn were also higher across all fertilized soil layers compared to those of the unfertilized control soil, with Ni enrichment being particularly notable. Nevertheless, all the measured heavy metal concentrations were within the limits stipulated by China’s soil environmental standards. Moreover, some studies have suggested that the short-term application of pig manure compost does not cause sharp increases in heavy metal accumulation and can enhance soil fertility [

8,

14,

29]. Given that pear roots are mainly distributed within the 0–40 cm layer, and based on our findings, it may be recommended to increase the application of organic fertilizer to improve the physicochemical properties of soil in Dangshan pear orchards.

4.4. Influence of Soil Chemical Compounds Composition Under Long-Term Fertilization

Soil chemical composition can be influenced by various environmental factors, such as microbial activity, rainfall, and fertilization. In this study, long-term fertilization conditions increased the number and total content of chemical compounds within the 0–60 cm soil depths (

Table S1). Furthermore, soil extracts from fertilized plots enhanced seed germination (

Table S3). In addition, several compounds, including 2,6,10-trimethylpentadecane, 2,7,10-trimethyldodecane, 3-methyltetradecane, 5-methyltetradecane, 7-methylheptadecane, octadecane, benzoic acid, dodecanoic acid, N-pentanoic acid, myristic acid-2,3-dipropyl ester, and isobutyl-4-octyl phthalate, were exclusively detected in the fertilized soil (

Table S2). These compounds were likely introduced via fertilization. Octadecane and benzoic acid have been identified as allelopathic substances that inhibit the growth of microalgae, lettuce, and rapeseed, with their effects intensifying at higher concentrations [

30,

31,

32]. Similarly, in this study, octadecane and benzoic acid both exhibited allelopathic effects on the tissue-cultured “Shanli” pear seedlings. Seedlings showed obvious leaf tip blackening and partial leaf folding when treated with octadecane at a concentration of 0.18 mmol·L⁻¹ (

Figure 7).

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that long-term fertilization significantly reduced the soil pH and increased the organic matter content within the topsoil. Furthermore, it led to a rapid increase in alkaline hydrolyzable nitrogen and available phosphorus, while available Cu content exceeded twice the optimal level. Although available potassium, exchangeable calcium, and magnesium levels remained suitable for pear growth, available Fe was insufficient. Moreover, long-term fertilization resulted in the accumulation of heavy metals, such as Cu, Hg, Ni, Cr, As, and Mn, although all the concentrations thereof remained within nationally prescribed standard limits. The diversity and abundance of soil compounds were significantly higher in the fertilized soil than in the unfertilized soil, and allelopathy tests confirmed that 0.18 mmol·L⁻¹ octadecane strongly inhibits the growth of “Shanli” pear tissue-cultured seedlings. Based on these results, we recommend the increased application of organic fertilizers to improve the soil quality in Dangshan pear orchards.

Author Contributions

Material preparation, data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing were performed by Luoluo Xie, Qingchen Zhao. Data analysis and chart generation were performed by Huihui Zhang, Wei Song, Guoguo Ling, Youyu Wang, Jiayi Zeng, Kelin Li, Yuxuan Jin and Wenxuan Pan. Bing Jia designed the methodology and conducted the critical review. Xiaomei Tang per-formed the critical review, commentary, and revision.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-28-14).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, Z.L.; Chen, D.L. Nitrogen fertilizer use in China – contributions to food production, impacts on the environment and best management strategies. Nutr Cycl Agroecosys 2002, 63, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, J.; Cai, W.; Li, G.; Mei, Y.; Yang, S. Different amounts of nitrogen fertilizer applications alter the bacterial diversity and community structure in the rhizosphere soil of sugarcane. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 721441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.T.; Jiang, Y.M. Characteristics of N, P and K nutrition in different yield level apple orchards. Sci Agric. 2006, Sin 39, 361–367. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Wolf, J.; Zhang, F.S. Towards sustainable intensification of apple production in China — Yield gaps and nutrient use efficiency in apple farming systems. J Integr Agric. 2016, 15, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.H.; Liu, S.L.; Wu, J.S.; Hu, R.G.; Tong, C.L.; Su, Y.Y. Effect of long-term application of inorganic fertilizer and organic amendments on soil organic matter and microbial biomass in three subtropical paddy soils. Nutr Cycling Agroecosystems. 2007, 81, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xiong, W.; Xu, H.; Hang, X.; Liu, H.; Xun, W.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Continuous application of different fertilizers induces distinct bulk and rhizosphere soil protist communities. Eur J Soil Biol. 2018, 88, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Sun, W.; Huang, Y. Changes in soil organic carbon in croplands subjected to fertilizer management: a global meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 27199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.C.; Gao, P.D.; Wang, B.Q.; Lin, W.P.; Jiang, N.H.; Cai, K.Z. Impacts of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic amendments supplementation on soil nutrient, enzyme activity and heavy metal content. J Integr Agric. 2017, 16, 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.T.; Kou, C.L.; Christie, P.; Dou, Z.X.; Zhang, F.S. Changes in the soil environment from excessive application of fertilizers and manures to two contrasting intensive cropping systems on the North China Plain. Environ Pollut. 2007, 145, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boora, R.S. Effect of inorganic fertilizers, organic manure and their time of application on fruit yield and quality in mango (Mangifera indica) cv. Dushehari. Agric Sci Digest. 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, Y.; Vila, B.; Montès, N.; Bousquet-Mélou, A.; Prévosto, B.; Fernandez, C. Fertilization and allelopathy modify Pinus halepensis saplings crown acclimation to shade. Trees. 2011, 25, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, T.C.; Braungardt, C.B.; Rieuwerts, J.; Worsfold, P. Cadmium contamination of agricultural soils and crops resulting from sphalerite weathering. Environ Pollut. 2014, 184, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, H.; Jia, L.; Huang, C.; Qiao, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Wan, Y. Long-term effects of intensive application of manure on heavy metal pollution risk in protected-field vegetable production. Environ Pollut. 2020, 263, 114552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Teng, Y.; Christie, P.; Luo, Y. Effects of long-term fertilizer applications on peanut yield and quality and plant and soil heavy metal accumulation. Pedosphere. 2020, 30, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Li, K.; Diao, T.T.; Sun, Y.B.; Sun, T.; Wang, C. Influence of continuous fertilization on heavy metals accumulation and microorganism communities in greenhouse soils under 22 years of long-term manure organic fertilizer experiment. Sci Total Environ. 2025, 959, 178294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Cheng, Z. Research progress on the use of plant allelopathy in agriculture and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy. Front Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.H.; Xuan, T.D.; Khanh, T.D.; Tran, H.D.; Trung, N.T. Allelochemicals and signaling chemicals in plants. Molecules. 2019, 24, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT FAOSTAT Database. 2016. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RF (accessed 20.12. 2016).

- Heng, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.D.; Jia, B.; Liu, P.; Ye, Z.F.; Zhu, L.W. Differentially expressed genes related to the formation of russet fruit skin in a mutant of ‘Dangshansuli’ pear (Pyrus bretchnederi Rehd.) determined by suppression subtractive hybridization. Euphytica. 2013, 196, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, S.; Kerry, R.G.; Das, G.; Paramithiotis, S.; Shin, H.S.; Patra, J.K. Revitalization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable development in agriculture. Microbiol Res. 2018, 206, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Pan, T.; Chen, J.; Lu, Q. Waveband selection for NIR spectroscopy analysis of soil organic matter based on SG smoothing and MWPLS methods. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2011, 107, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Lees, H. Studies on soil organic matter: Part II. The extraction of organic matter from soil by neutral reagents. Agric Sci. 1949, 39, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscalu, O.M.; Nedeff, V.; Chițimuș, A.D.; Sandu, I.G.; Partal, E.; Moșneguțu, E.; Sandu, I.G.; Rusu, D.I. Influence of fertilization systems on physical and chemical properties of the soil. Revista de Chimie. 2018, 224, 105520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oana.; Nedeff V.; Chiţimus D.; Partal E.; Emilian M.; Sandu I.; Dragos R. Influence of fertilization systems on physical and chemical properties of the soil. Revista de Chimie. 2018, 69:3106-3111. [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Long-term impact of fertilization on soil pH and fertility in an apple production system. Soil sci plant nutr. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shu, A.; Song, W.; Shi, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Z. Long-term organic fertilizer substitution increases rice yield by improving soil properties and regulating soil bacteria. Geoderma. 2021, 404, 115287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbenin, J.; Yakubu, S. Potassium–calcium and potassium–magnesium exchange equilibria in an acid savanna soil from northern Nigeria. Geoderma. 2006, 136, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.R. Effect of soil pH on availability to crops of metals in sewage sludge-treated soils.I. Nickel, copper and zinc uptake and toxicity to ryegrass. Environ Pollut. 1994, 85, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.J.; Zhang, L.F.; Liu, Z.B.; Zhang, W.X.; Lan, X.J.; Liu, X.M.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.R.; Li, Z.Z.; Wang, P. Effects of long-term application of chemical fertilizers and organic fertilizers on heavy metals and their availability in reddish paddy soil. Huan Jing Ke Xue. 2021, 42, 2469–2479. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Inderjit; Kaushik, S. Cellular evidence of allelopathic interference of benzoic acid to mustard (Brassica juncea L.) seedling growth. Plant Physiol and Bioch. 2005, 43, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Takeshita, S.; Kimura, F.; Ohno, O.; Suenaga, K. A novel substance with allelopathic activity in Ginkgo biloba. J Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, H.; Prajapati, S.K. Allelopathic effect of benzoic acid (hydroponics root exudate) on microalgae growth. Environ Res. 2022, 219, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).