1. Introduction

Environmental degradation, restricted agricultural development, and poverty resulting from increasing soil salinization have profoundly affected human society, particularly in the face of escalating global greenhouse gas emissions. (Upasana et al., 2017). Effective restoration strategies and the judicious utilization of saline-alkali land are paramount for halting the salinization process, rectifying the issue of insufficient arable land, and augmenting agricultural efficiency and livestock growth. However, previous research on the restoration of saline-alkali land has primarily centered on plant yield and soil properties, often neglecting an evaluation of plant intrinsic response mechanisms.

Engineering, chemical, biological, and integrated approaches can rectify soil structure, enhance its physical and chemical attributes, bolster nutrient accumulation, and amplify crop yield, production performance, and plant nutrient quality (Zhao et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Flue gas desulfurization (FGD) gypsum, a prominent by-product of power generation plants and a chemical amendment for saline-alkali land, has shown promise. Recent studies indicate that FGD gypsum can lower soil pH and exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP), thereby expediting plant growth and improving salt tolerance (Mao et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2018). Combining FGD gypsum with other soil-conditioning materials such as organic matter and humic acid can decrease soil pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and Na+ content, while increasing soil porosity and Mg2+ content, consequently boosting crop yield (Zhao et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2020). Targeted biological interventions, such as planting salt-tolerant species on saline-alkali land and applying microbial materials, are currently deemed the most effective and secure means of restoring saline-alkali lands (Hidri et al., 2016; Sun, 2017). Studies have demonstrated that biological measures not only diminish soil salinity during plant growth but also enhance the physicochemical properties of saline soils and facilitate the recovery of soil microbiomes (Hu et al., 2008; Wang, 2018). Nevertheless, each of these engineering, chemical, and biological measures possesses its own set of drawbacks. For instance, engineering measures entail substantial human and material resources. Excessive application of chemical substances as soil conditioners may lead to secondary contamination of soil or plants, or both. Biological measures often entail an unpredictable and protracted duration of persistent effects effects (Alvarez et al., 2006; E et al., 2014). Thus, adopting an integrated and systematic approach, wherein various measures are applied judiciously and scientifically, is imperative to surmount these limitations. Employing both chemical and biological measures in tandem to reduce the quantity of chemical conditioning agents used, while maximizing overall improvement through synergistic effects, could represent an efficient strategy for capitalizing on the benefits of both methods while minimizing associated risks and addressing their respective weaknesses. In China, FGD gypsum and humic acid have been extensively researched and employed in saline land restoration, with growing interest in microbial-mediated restoration of saline land. However, there has been relatively scant research on the combined use of these methods, especially in realistic field settings for saline-alkali grassland.

Plants employ a mechanism wherein they selectively absorb K+ and Ca2+ to elevate their internal K+/Na+ and Ca2+/Na+ ratios, maintaining heightened levels of K+ and Ca2+. This, in turn, mitigates the detrimental impact of Na+ on the plant, thereby enhancing its salt resistance (Shen et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2021). Despite various restoration measures potentially causing differential alterations in the ionic content and balance of plants, the underlying patterns and mechanisms remain poorly elucidated.

Medicago sativa L., known for its salinity tolerance, plays a pivotal role in enhancing the characteristics of saline-alkali soils (Hu et al., 2008; Wang, 2018; LIU et al., 2021). Unsurprisingly, it finds widespread application in establishing artificial grasslands and fortifying the resilience of natural grasslands. As a result, it holds significant importance in both grassland ecosystem restoration and sustainable livestock development. However, the growth of M. sativa can be impeded under escalating salinity stress (Wang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021).

Recent research predominantly focuses on the impact of intervention measures on soil properties, plant growth, and crop quality. Rarely has there been reporting on the distribution or transport of cations within plants under varying restoration measures, leaving the mechanisms behind most vegetation restoration largely unexplored. Hence, this study seeks to examine the effects of combined biological and chemical restoration measures on soil properties, as well as the characteristics of ion distribution and transport in plants. This knowledge can be harnessed to enhance the salt tolerance of plants and expand the range of salt-tolerant species based on recommended practices. This, in turn, could optimize the benefits of saline-alkali land restoration and utilization while mitigating the risk of secondary contamination.

With this objective in mind, the study aimed to assess the effects of FGD gypsum in conjunction with humic acid and bio-fertilizer on soil properties, plant growth, and the distribution and transport of ions in M. sativa. Additionally, it seeks to unravel the interplay between measures, soil, and plants. Three hypotheses were tested: (1) the applied restoration measures can variably reduce soil pH, ESP, and SAR, thereby improving the soil environment; (2) the application of bio-fertilizer combined with FGD gypsum and humic acid amplifies the positive effects and is more conducive to plant growth; and (3) the restoration measures promote plant growth by facilitating the distribution of beneficial ions within plants and their subsequent transport to leaves.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The experimental saline-alkali soil was collected from Toketo County, Hohhot City, in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Toketo County is situated on the Tumocheon Plain at the southern foot of the Yin Mountains and on the northern bank of the upper and middle parts of the Yellow River (111°2′30′′~111°32′21′′E, 40°5′55′′~40°35′15′′ N). It falls within a temperate continental monsoon climate zone, with an average annual temperature of 9°C and an active accumulated temperature (≥10°C) of 2961°C. The average annual precipitation in this area is 316 mm, with 70% falling between July and September, and the average annual evaporation is 1938.2 mm.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted at the Shaerqin Experimental Station of the Institute of Grassland Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, from June to October 2021. The

M. sativa cultivar employed in the experiment was “Zhongmu No. 1.” Saline-alkali soil was collected from a depth of 40 cm in Manshui Village (Gucheng Town, Tokoto County) over a 25-m

2 surface area (5 m × 5 m). After removing contaminants such as plant roots, the soil was thoroughly mixed and packed into plastic pots with a top diameter of 28 cm, a bottom diameter of 20 cm, and a height of 28 cm. Each pot was filled with 10 kg of soil, and all pots (n = 40) were buried in the experimental area. The basic properties of the soil and FGD gypsum used in the experiment are detailed in

Table 1. The humic acid was manufactured by Dalian Jiucheng Products Co., Ltd., containing 75% humic acid content; the bio-fertilizer was produced by Shandong Jinyao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., with an effective live bacterial count of ≥200 × 10

8·g

−1.

The field experiment utilized a two-factor split-plot design, with the main plot receiving the applied bio-fertilizer (B) factor at two levels, while the subplot received FGD gypsum with humic acid (D) at four levels. The dosage and ratio of FGD gypsum to humic acid (10:1) were determined based on relevant research. The dosage levels for each treatment are detailed in

Table 2, with five replicates used for each. Each pot was sown with 20 fully developed

M. sativa seeds and watered twice or three times daily in small amounts during the first week post-sowing, and as needed afterward until seedling emergence. All treatments and their levels were managed uniformly in the field, and no additional fertilizer was applied during the experiment.

2.3. Sampling and Measurements

After harvesting the plants in pots, soil samples were collected. Initially, any debris was removed, followed by air-drying, grinding, and passing through a 1-mm aperture sieve. The soil was then shaken in a 5:1 ratio of water-to-soil and allowed to stand before being filtered. Soil pH was measured using the potentiometry method, soil EC was determined using the electrode method, and soil salinity was derived using Pang et al.’s method (Pang et al., 2010). For the quantification of soil water-soluble HCO3− and CO32−, the double-indicator titration method was employed; Cl− was assessed using the AgNO3 titration method; SO42− was determined using the EDTA indirect titration method; Ca2+ and Mg2+ were measured using the EDTA complex titration method; and, Na+ and K+ were quantified using the flame photometry method (Bao, 2000). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was assessed via spectrophotometry, and exchangeable sodium (ES) was determined using flame photometry with NH4 OAc-NH4 OH (Yang et al., 2020).

2.3.1. Plant Growth and Biomass Variables

Before harvesting, five plants of similar size (i.e., growth) were selected from each pot to determine individual plant height, with the average value per pot calculated. Similarly, five plants of average growth were chosen to measure alfalfa’s root diameter with vernier calipers, and the average value per pot was determined. Biomass was harvested using the total harvest method, and the removed plants were divided into leaves, stems, and roots. These samples were weighed, and after bringing them back to the laboratory, they were heated at 105°C for 30 minutes, followed by further drying at 65°C until a constant weight was achieved. They were then re-weighed (dry), and the biomass of each plant organ per treatment level was calculated.

2.3.2. Plant Ion Content

For each sample, 0.2 g was weighed and dried following the method described in the Plant growth and biomass variables section. Subsequently, 8 mL of HNO3 was added. The mixture was boiled using a graphite digestion apparatus until about 1 mL of liquid remained, after which 2 mL of H2O2 was introduced. The resulting digested solution was brought to a 50-mL volume with ultrapure water, and passed through a 0.45-μm filter membrane. Finally, an inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, Thermo Fisher Scientific, ICAP6300Duo, Waltham, MA, USA) was utilized to measure the contents of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+.

2.4. Data Analysis

The sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) was calculated using the following formula:

where Na

+, Ca

2+, and Mg

2+ are the amounts of water-soluble Na

+, Ca

2+, and Mg

2+ in a soil sample.

The transport selectivity ratio (TS) indicates whether cations in transport are behaving synergistically or antagonistically. A greater TS value suggests that organ b is more effective in regulating Na

+ and facilitating the transport of Y ions to organ a. The equation for TS is as follows:

where: Y is the ion content; a, b are the leaf, stem, and/or root organ of the plant sample.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To test the effects of both treatments on plant attributes (height, root length, root diameter, biomass, ion content, and ion transport indicators) and soil properties (pH, salinity, SAR, ESP, and amounts of water-soluble ions), a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. This was followed by Tukey’s HSD test (at P < 0.05), implemented in SPSS software (v23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Each reported value represents the mean ± standard deviation of five individuals (n = 5). Pearson correlation tests were utilized to identify the relationships between plant and soil properties. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was employed to establish the relationships among soil properties, plant growth indicators, and the biomass, ion content, and transport indicators of plants, using Canoco 5.0 software. Linear Regression analysis was performed to quantify the relationship between soil environmental factors and the biomass of plants. For evaluating direct or indirect effects, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed using AMOS 24 software.

3. Results

3.1. pH, Salinity, SAR, ESP, and Water-Soluble Ion Content in the Soil

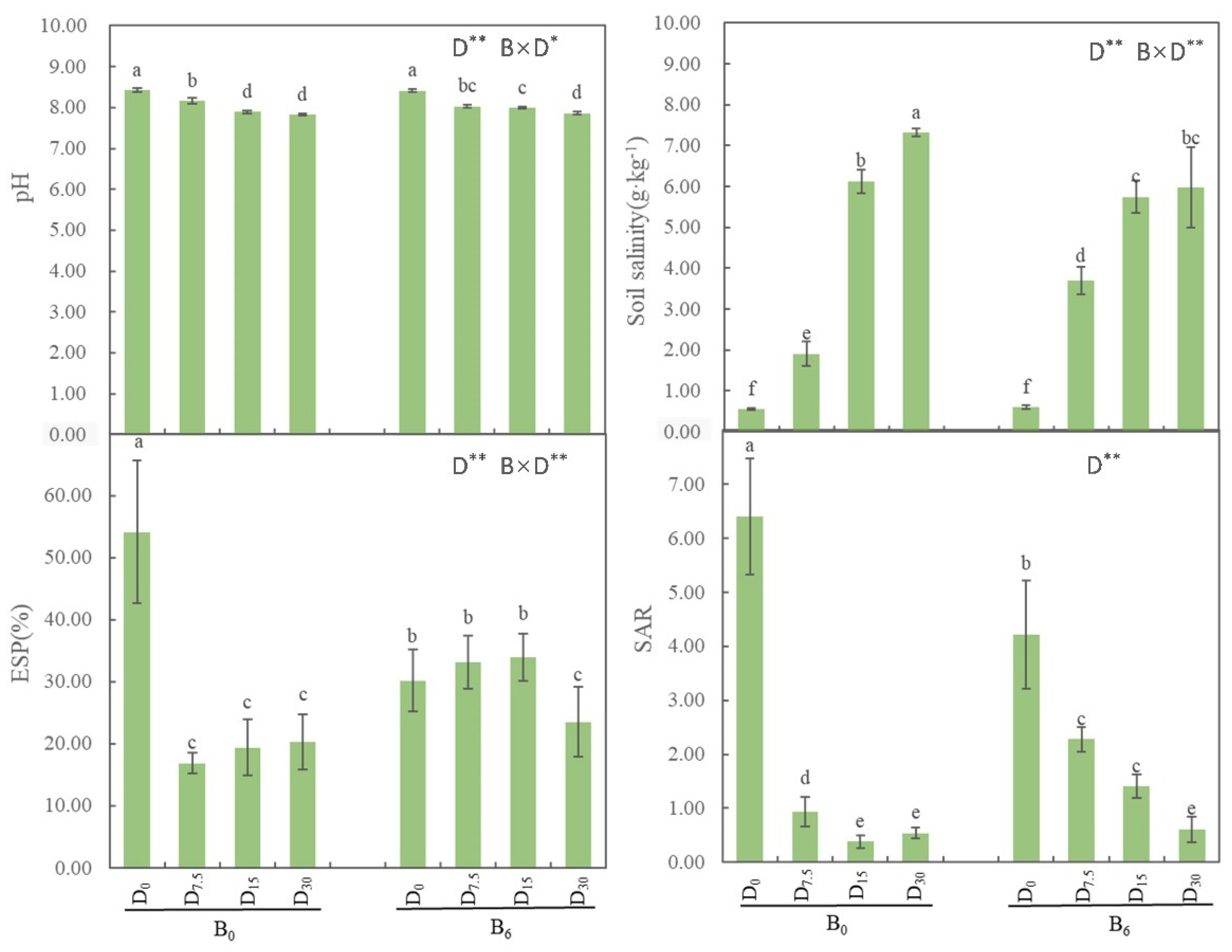

All treatments led to a significant decrease in pH and SAR (

P < 0.05; see

Figure 1), while significantly increasing soil salinity (

P < 0.05; see

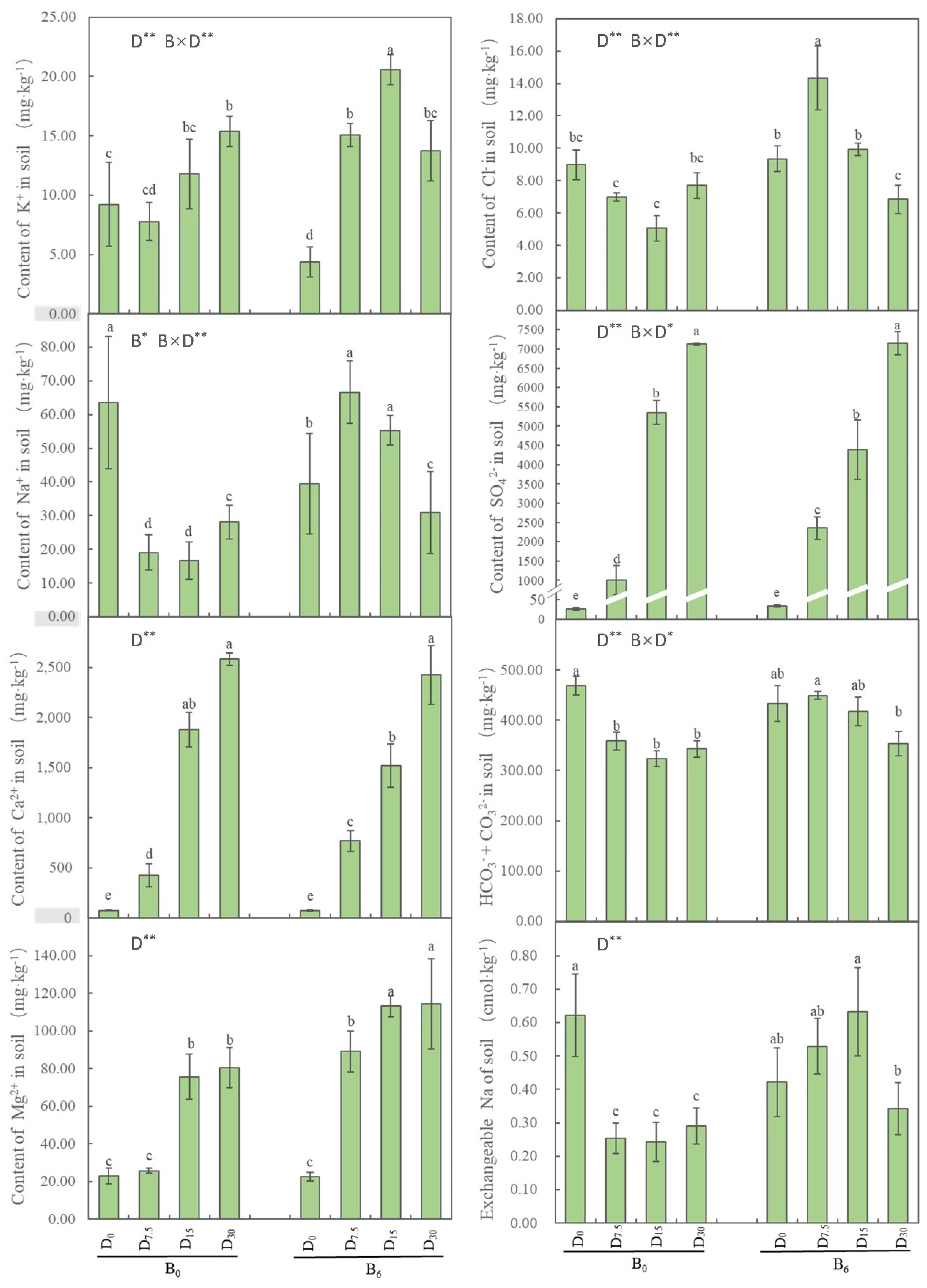

Figure 1). The water-soluble Na

+ content and ES were notably higher after the application of bio-fertilizer (

P < 0.05; see

Figure 2). Meanwhile, the water-soluble K

+ content exhibited a highly significant difference under the treatment of FGD gypsum with humic acid and bio-fertilizer (

P < 0.05; see

Figure 2). As for water-soluble Ca

2+, Mg

2+, Cl

−, SO

42−, HCO

3−, and CO

32−, all their contents displayed significant variations under different applications of FGD gypsum with humic acid (

P < 0.05; see

Figure 2).

3.2. Plant Growth Indicators and Biomass

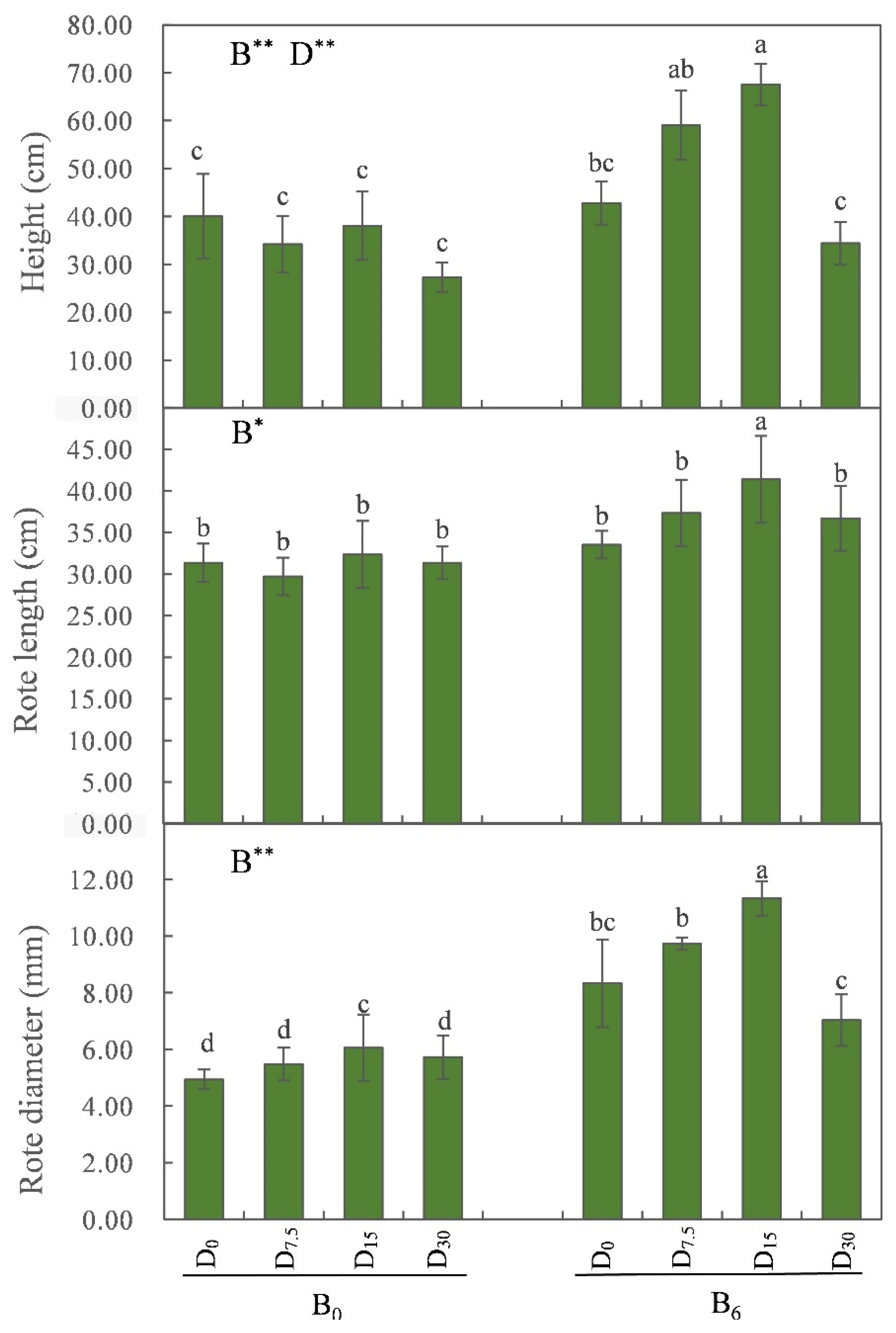

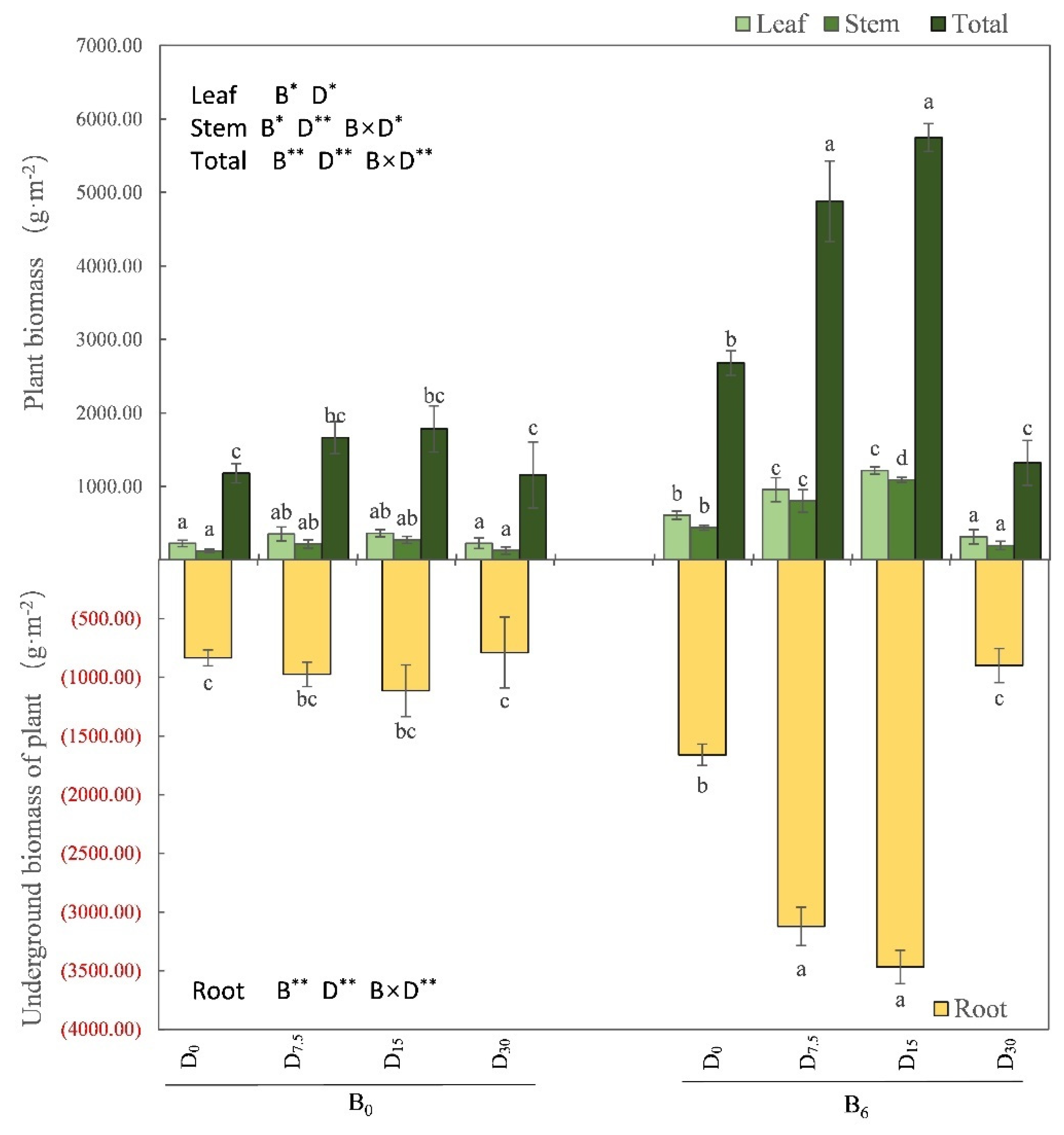

Application of bio-fertilizer significantly enhanced plant height, root length, and root diameter (

P < 0.05; see

Figure 3), along with the biomass of each organ, as well as the overall biomass, of

M. sativa plants (

P < 0.05; see

Figure 4).

3.3. Ionic Effects in M. sativa

3.3.1. Concentrations of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+

Leaf K

+ levels were notably affected by the doses of FGD gypsum with humic acid. Additionally, the application of bio-fertilizer significantly increased leaf Mg

2+ while decreasing stem K

+. The combined use of FGD gypsum with humic acid and bio-fertilizer substantially reduced the Na

+ content in leaves (

Figure 5).

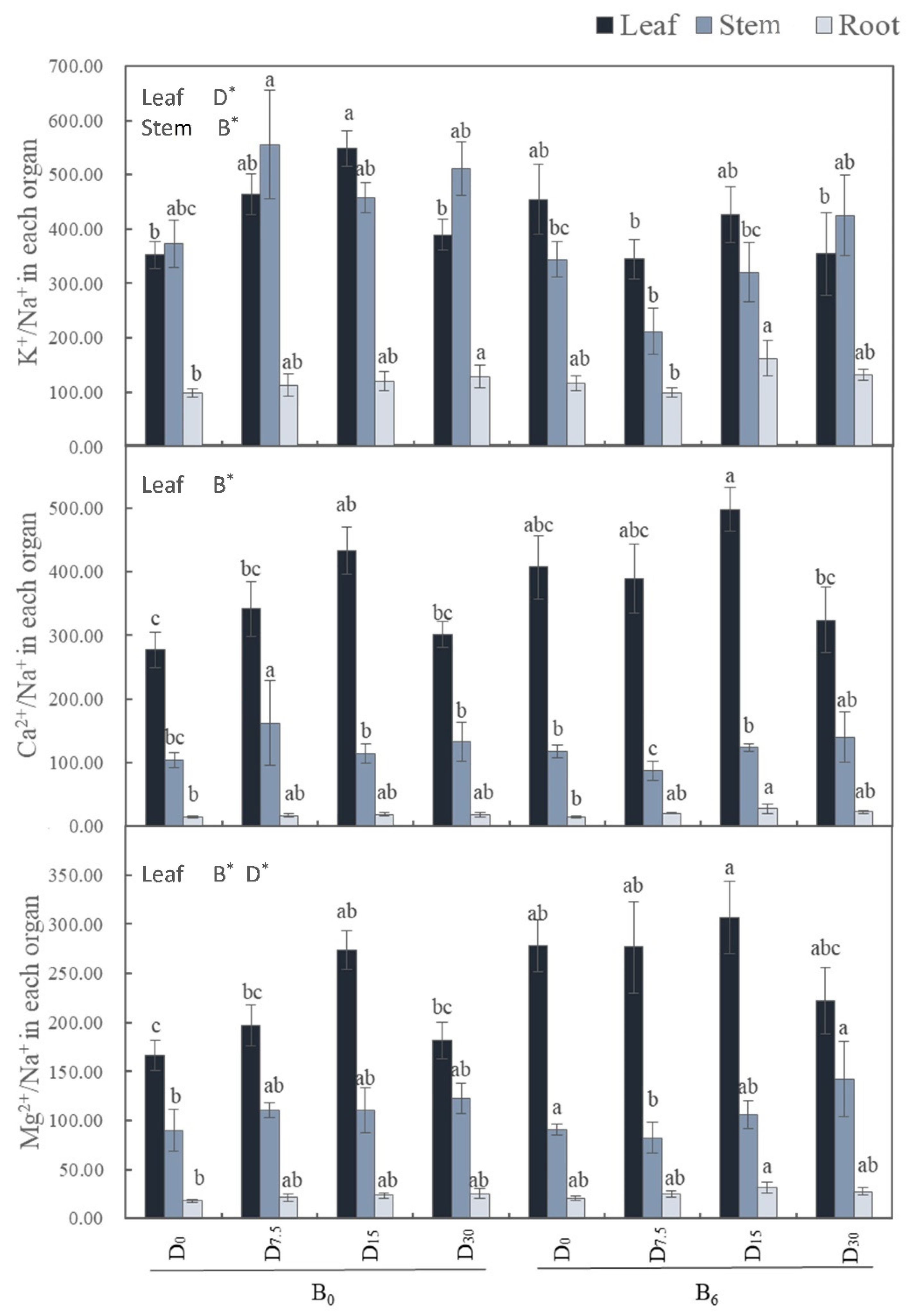

3.3.2. Ratios of K+/Na+, Ca2+/Na+, Mg2+/Na+in Plant Organs

Both leaf K

+/Na

+ and Mg

2+/Na

+ ratios saw significant increases under the medium dose of FGD gypsum with humic acid. However, the application of bio-fertilizer significantly increased the leaf Ca

2+/Na

+ and Mg

2+/Na

+ ratios while lowering the stem K

+/Na

+ ratio (

Figure 6).

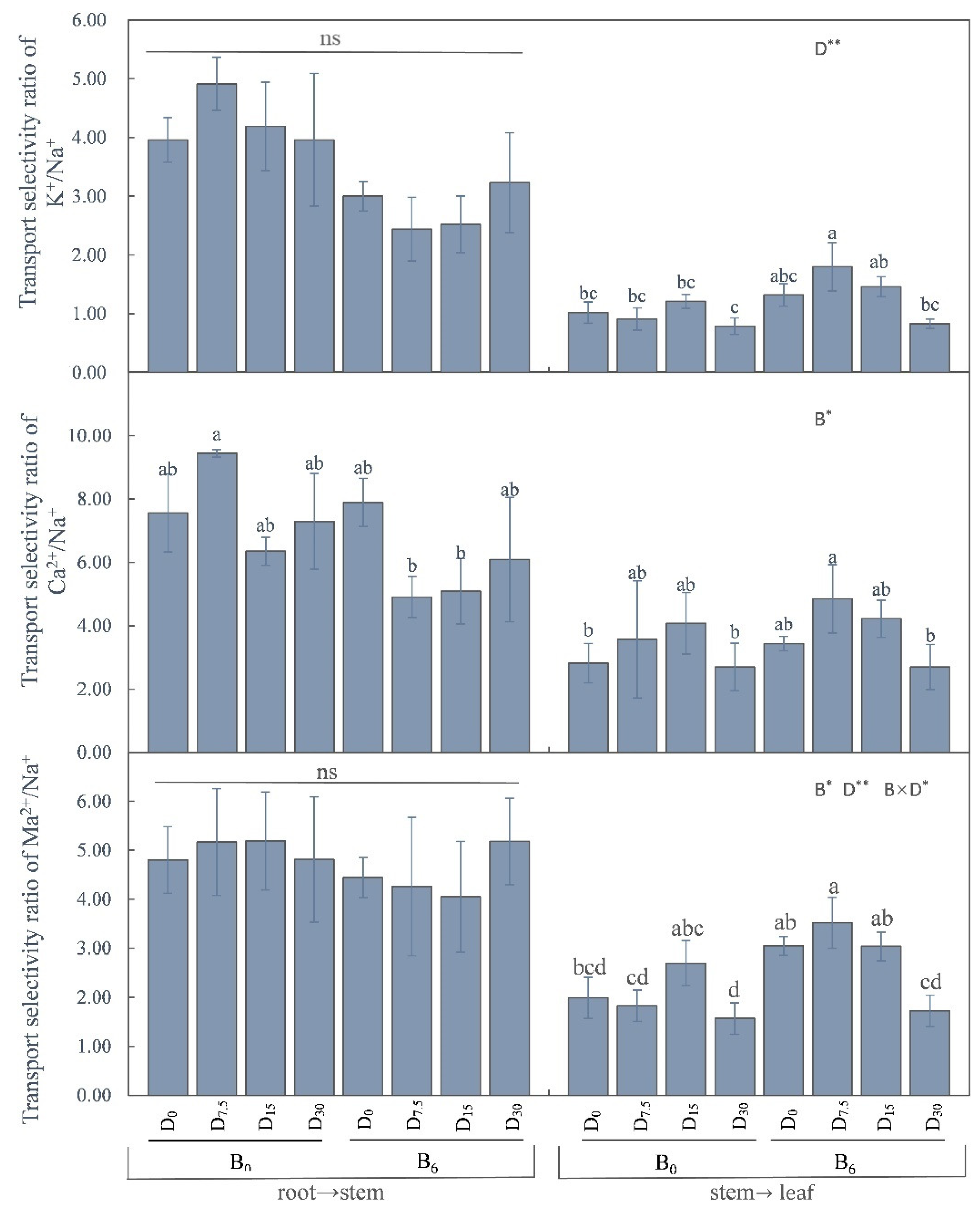

3.3.3. Cation TS Ratio of M. sativa

The stem-to-leaf selectivity ratio of K

+ showed significant variation under subplot treatments, with the highest ratio observed at D

7.5. Furthermore, the stem-to-leaf selectivity ratio of Ca

2+ was significantly elevated by the application of bio-fertilizer. As for Mg

2+, its ratio was notably affected by both the primary and secondary zones. Specifically, the application of bio-fertilizer substantially increased the ratio for Mg

2+ (

Figure 7).

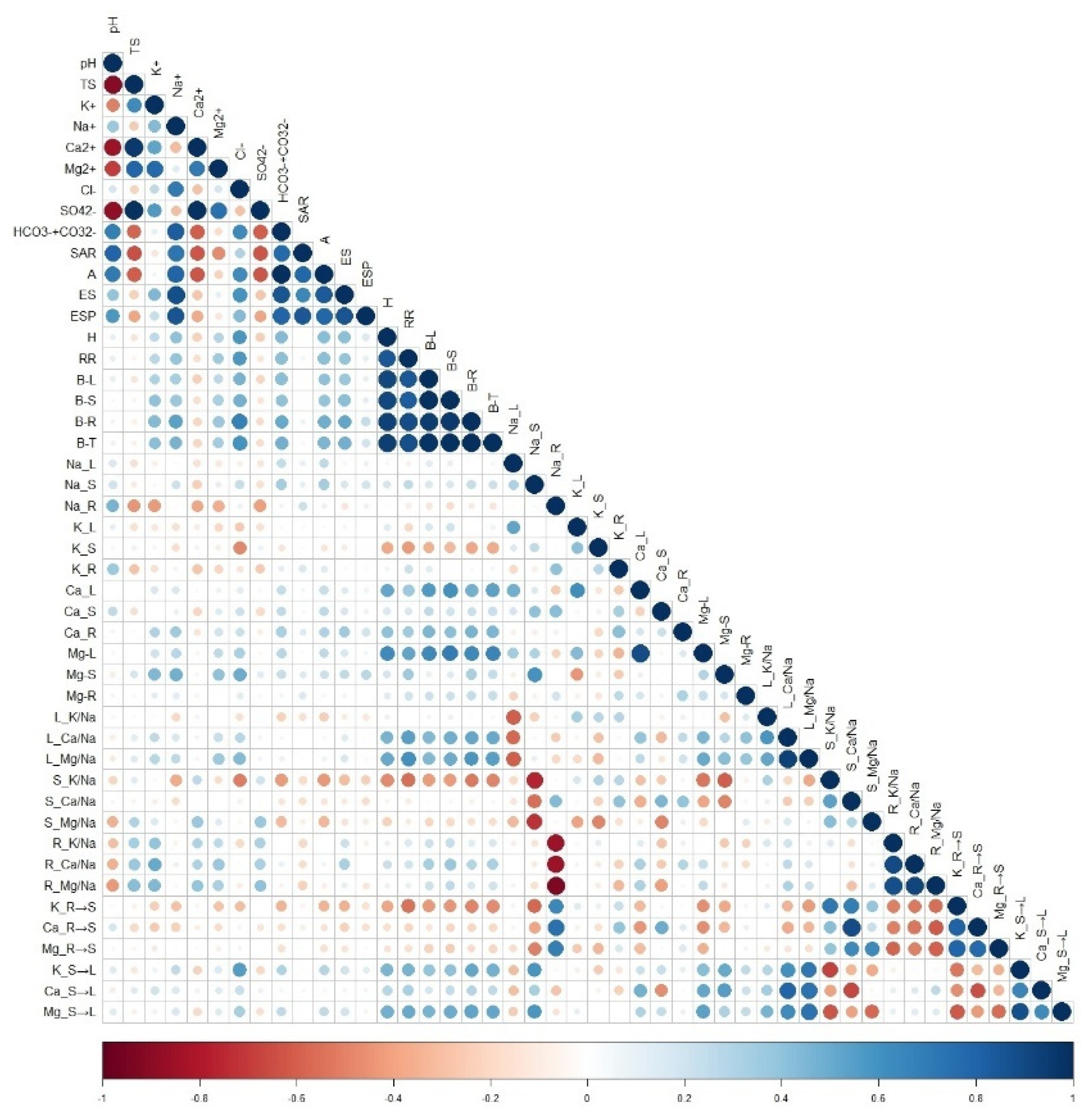

3.4. Correlation Analysis

According to the Pearson correlation coefficients, the biomass of

M. sativa showed significant correlations with soil Na

+, Cl

−, HCO

3−, and ESP. Plant height and biomass exhibited positive correlations with leaf Ca

2+ and Mg

2+ contents, leaf Ca

2+/Na

+ and Mg

2+/Na

+ ratios, and the stem-to-leaf selectivity ratio of K

+ as well as Mg

2+. The biomass values of different organs were significantly and negatively correlated with the root-to-stem selectivity ratios of K

+, Ca

2+, and Mg

2+ (see

Figure 8).

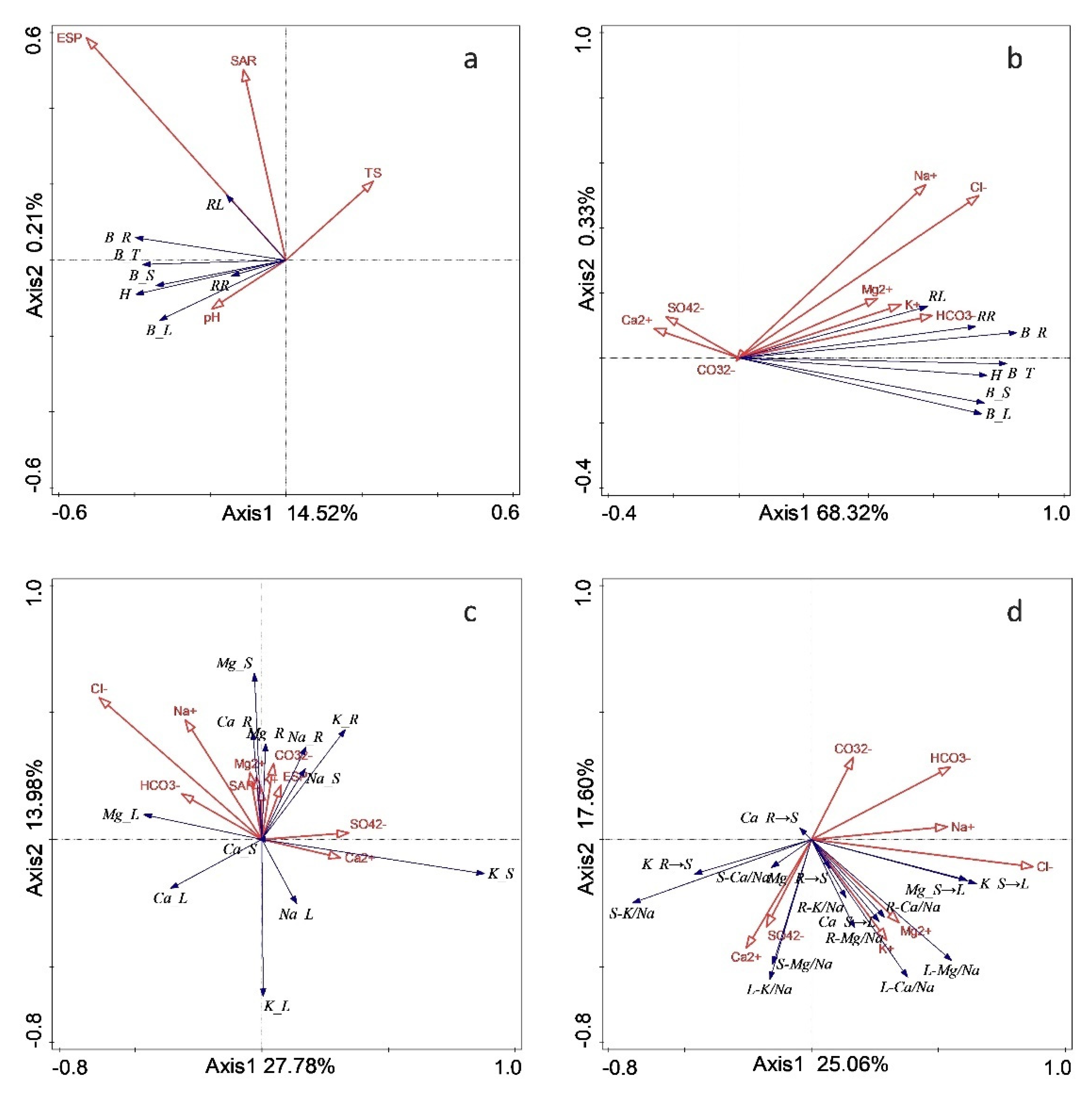

The RDA demonstrated the significant influence of the soil environment on plant growth and biomass. Both responses were highly correlated with ESP. While soil pH positively influenced growth and biomass, soil salinity (TS) had a negative effect. However, neither pH nor TS emerged as crucial environmental factors. The soil contents of Cl

− and Mg

2+ each exerted a significant positive effect on the growth and biomass of

M. sativa (

P < 0.05). Additionally, the length, diameter, and biomass of roots each showed positive correlations with soil K

+, Mg

2+, and HCO

3− (see

Figure 8). The RDA also indicated a strong positive correlation between the ion content of roots and the corresponding ion content of soil. Notably, the Na

+ content in organs was highly correlated with that in the soil. Furthermore, the Mg

2+ content in soil had a robust positive effect on the ion content and transport dynamics in

M. sativa, with a significant positive correlation between the Mg

2+ content in roots or stems and that in the soil. The selective transport ratios of K

+, Ca

2+, and Mg

2+ from stems to leaves, as well as that of Mg

2+ from roots to stems, were positively correlated with the amounts of Na

+, K

+, and Mg

2+ in the soil, whereas those of K

+ and Ca

2+ from roots to stems were negatively correlated with the amounts of Na

+, K

+, and Mg

2+ in the soil (see

Figure 9).

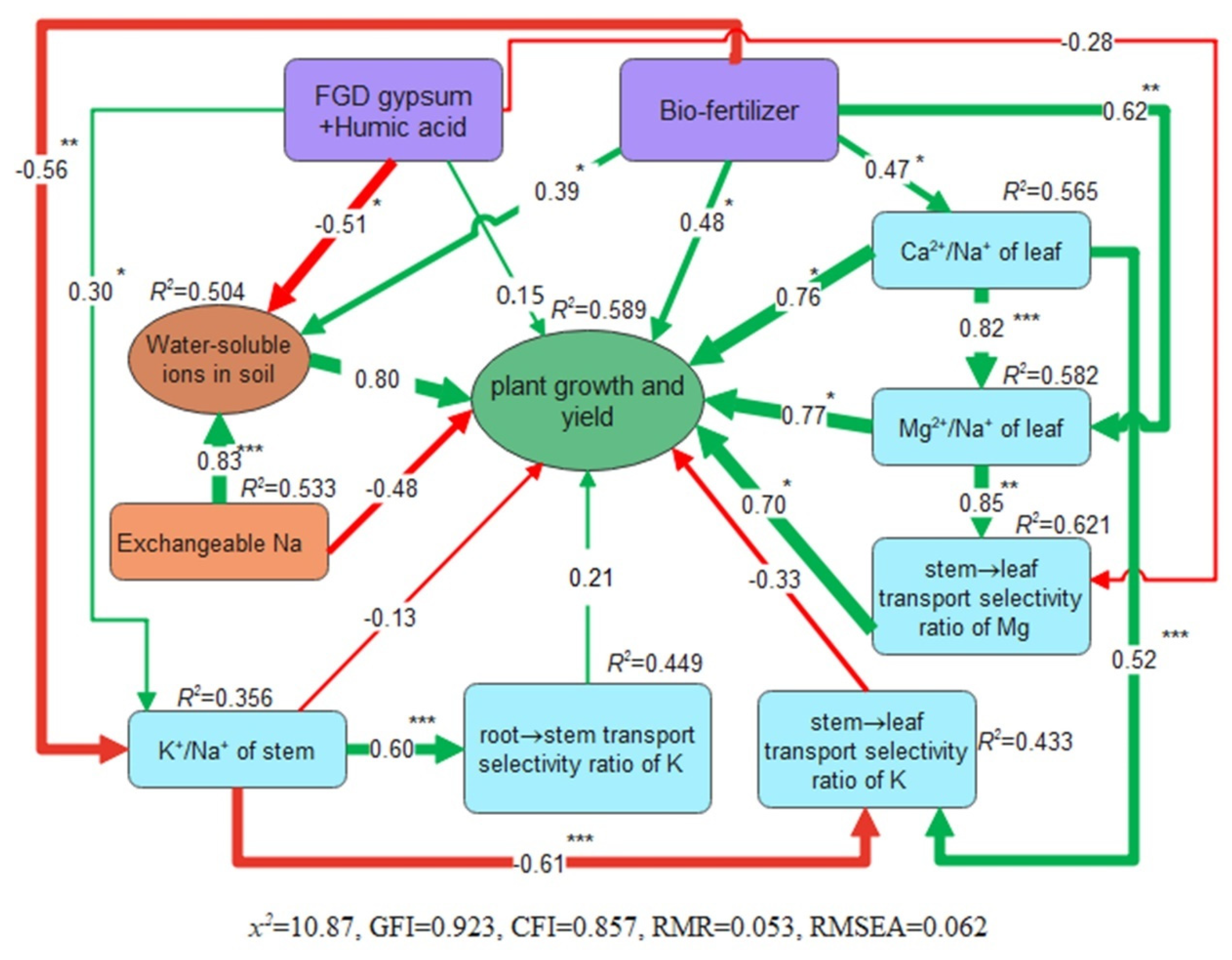

In the SEM conducted in this study, the soil ion latent variables consisted of K

+, Na

+, Cl

−, and HCO

3−, while the plant growth latent variables encompassed plant height, root diameter, leaf, stem, and root biomass. The SEM results illuminated that the combination of FGD gypsum with humic acid and bio-fertilizer significantly influenced plant growth. Furthermore, FGD gypsum with humic acid exhibited a greater impact on soil properties, while bio-fertilizer had a more pronounced effect on ion partitioning and transport in

M. sativa plants (see

Figure 10).

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Different Restoration Measures on Soil

Soil pH, EC, ES, and ESP represent the primary chemical properties that can be influenced by the type of salt. In this study, all restoration measures led to a decrease in soil pH, SAR, and ESP. −−As the dosage of FGD gypsum with humic acid application increased, soil Cl−, HCO3−, pH, SAR, and ESP all exhibited a reduction. These findings align with those of previous research.

The presence of Ca2+ in FGD gypsum allows it to replace exchangeable Na+ in soil colloids. Additionally, Ca2+ can engage in a precipitation reaction with water-soluble CO32− and HCO3− in saline-alkaline soil (Zhao et al. 2018). The inclusion of humic acid enhances the dissolution of gypsum (Agbede et al. 2013; Arai et al. 2018), thereby augmenting the Na+ replacement capacity. Although the dissolution rate of FGD gypsum is modest, the chemical reaction between Ca2+ and water-soluble CO32− and HCO3− is relatively swift. This results in a sharp decline in soil pH during the year of application, which corroborates our current findings. This study highlights that the triple combination of FGD gypsum with humic acid and bio-fertilizer significantly diminishes Na+, HCO3−, and CO32− levels in the soil. The joint application of FGD gypsum and bio-fertilizer exerts a more potent influence on ameliorating saline-alkali soil compared to their individual applications.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the application of bio-fertilizers can expedite the dissolution of desulphurization gypsum by enhancing soil structure, providing a beneficial complementary effect for the enhancement of saline soils (Wang et al. 2015). Furthermore, the use of microbial mycorrhizal agents activates soil nutrients (Pang et al., 2009; Pang et al., 2011), intensifying the desalination effect on soil and fostering crop growth. This establishes favorable conditions for the improvement of salinized arable land through the use of desulphurization gypsum. Concurrently, the application of desulphurization gypsum bolsters soil structure (Chen et al.2009; Liu et al., 2011) and lowers the soil’s pH value, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of bacterial fertilization.

In this study, the addition of FGD gypsum with humic acid led to an increase in soil salinity. This outcome aligns with the findings reported by Zheng et al. and Tian et al. (Zheng et al., 2012; Tian et al., 2018) We conducted a potted experiment without irrigation during the plant-growing period, resulting in inadequate drainage of salts and an overall elevation in the total salinity of the potted soil. In this process, Ca2+, acting as a salt, reacts with free NaHCO3 and Na2CO3 in the soil, resulting in the formation of CaCO3, CaHCO4, and Na2SO3. While Na2SO3 can be leached through drenching, insufficient drenching can lead to an increase in the overall soil salinity (Mao et al., 2016; Tian et al., 2018). Despite the rise in total water-soluble salts caused by the application of an appropriate dose range of FGD gypsum, it did not negatively impact plant growth. On the contrary, reductions in soil salinity and alkalinity notably enhanced plant growth (Mao et al., 2016).

4.2. Effects of Different Restoration Measures on Plant Growth and Yield

In this study, the application of bio-fertilizer notably enhanced plant height, root length, and root diameter. Under the conditions of bio-fertilizer application, the use of medium and low doses of FGD gypsum with humic acid proved to be more beneficial for plant growth and development. This underscores that the combined application of FGD gypsum and bio-fertilizer is more effective, in line with the findings of Wang (Wang et al., 2015). The application of FGD gypsum leads to improvements in soil organic matter, soil physical properties, and soil microbial communities (Li et al., 2012; Nan et al., 2016), in addition to promoting plant growth and enhancing plant stress tolerance (Sun 2013; Mao 2016). Macromolecular humic substances exhibit the capacity to bind ions. These substances, rich in oxygen-containing acidic functional groups, possess robust ion exchange and complexation capabilities. They may also interact with salt separation agents, thereby diminishing the latter’s effectiveness (Rajapaksha et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016). Humic acid further fosters the formation of soil aggregates, enhancing the aggregate structure of the soil, and regulating water, fertilizer, gas, and heat conditions in the soil, thereby enhancing the growth environment for crops. The addition of humic acid to desulfurized gypsum alleviates the detrimental effects of salt stress on plants. It reduces the binding rate of Na+ to the plant cell wall membrane and improves the functioning of cell plasma membranes. This, in turn, enhances salt tolerance and yield of plants (Agbede et al., 2013; Arai et al., 2018). Additionally, it promotes root growth by increasing the concentration of essential mineral nutrients in plants, along with the organic acids and residues secreted by their roots. The organic acids secreted by roots, as well as those produced by microbial decomposition, also neutralize soil alkalinity. Moreover, the return of litter (roots, stems, leaves) to the soil enhances soil structure, augments soil organic matter, and boosts soil fertility (Vishnu et al., 2016).

4.3. Effects of Different Restoration Measures on Plant Ion Content and Transport

We observed that bio-fertilizer significantly increased the leaf content of Mg2+ and the leaf ratios of Ca2+/Na+ and Mg2+/Na+. It also facilitated the transport of Ca2+ and Mg2+ from stems to leaves. The application of FGD gypsum with humic acid significantly raised the leaf content of K+ and the ratios of K+/Na+ and Mg2+/Na+ in leaves, and it promoted the transport of Mg2+ from stems to leaves. Overall, these findings suggest that the selective uptake of K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ by M. sativa leaves significantly increased due to the restoration measures, as did the transport of beneficial ions from roots and stems to leaves. This coordinated physiological response should alleviate the ion toxic effects of saline-alkali soils on plants, ensuring the normal functioning of their leaves (Wang et al., 2018).

Salinity and alkalinity stress primarily affect plants by disrupting osmosis, leading to physiological drought, ionic poisoning of tissues and cells, and hindering nutrient uptake (Sun 2017). Maintaining the ionic equilibrium within plant cells is crucial for stabilizing the intracellular environment. However, adverse abiotic conditions such as high temperature, salinity, and frost damage can disrupt this balance, impairing normal metabolic processes (Tang et al., 2017). Elevated levels of Na in the soil solution can hinder the K nutrition of plants (Cakmak, 2005). Therefore, it is recommended to maintain an optimal K level in salt-affected soils for optimal plant growth (Wakeel, 2013), development, and yield. In this context, K+ plays a critical role as an osmoregulatory ion. A higher concentration of K+ can mitigate the osmotic stress effect in saline soil, enhancing the salt tolerance of plants. Ca2+ acts as an essential signaling molecule, contributing to cellular stability and safeguarding cell membrane structure under salt stress without affecting K+ quality in plants. This helps alleviate the effects of salt stress and even enhances the selective uptake and transport of K+ to reinforce the ionic balance (Ye et al., 2020). Another cation, Mg2+, proves advantageous in enhancing photosynthesis in leaves, improving light energy utilization, and meeting the light energy requirements for plant growth, thereby boosting salt tolerance. Upon absorption of Na+ from saline soils with high Na+ concentrations and subsequent accumulation in saline environments, plants face reduced ability to absorb K, P, Ca, and other nutrients due to the competition for Na+ (Lashari et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2018). By regulating ion distribution and transport processes in plants, effective restoration measures for saline-alkali land can mitigate osmotic stress and ion toxicity. This, in turn, promotes plant growth, development, and enhances salinity tolerance. When applied to saline sites, the Ca2+-rich FGD gypsum supports the “potassium enrichment and sodium rejection” process in plants through Ca2+ aggregation (Peter 2012). Our research aligns with the findings of the aforementioned literature. Comparatively, the selective transport ratios of beneficial ions, namely K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, from roots to stems and subsequently from stems to leaves were generally higher post-restoration, especially from roots to stems. This suggests that the experimental measures bolstered the ability of roots and stems to trap Na+ and thereby inhibit the internal transport of Na+ within plants. This, in turn, reduces the damage incurred by excess Na+ exposure and input to plants.

In this study, we observed a strong correlation between plant growth and the content and transport of Mg2+ within the plant body. The Mg2+/Na+ ratio and the selective transport ratios from roots or stems to leaves of all organs showed varying degrees of increase under different treatments. This indicates that these interventions enhanced the plant’s ability to selectively absorb Mg2+ in its leaves, ultimately improving salt tolerance and promoting healthy growth. Mg2+ plays a crucial role in numerous physiological and biochemical processes during plant development and growth. Approximately 35% of atmospheric Mg2+ is transported to chloroplasts for photosynthesis. Beyond its role in light reactions as a component of chlorophyll, Mg2+ also activates photosynthetic enzymes for carbon fixation (Marschner 1995; Horlitz et al., 2000; Karley et al., 2009; White et al., 2009). Moreover, Mg2+ acts as an activator for many enzymes in plants, and a deficiency in Mg can reduce the efficiency of carbon assimilation, subsequently lowering photosynthetic efficiency (Riens et al., 1992). Additionally, Mg2+ supports protein synthesis and nitrogen metabolism, both of which are integral processes for plant growth. In particular, Mg2+ influences nitrogen metabolism by regulating the activity of key enzymes such as nitrate reductase (Chen et al., 2021). The effective restoration measures, such as B6D15 and B6D7.5, demonstrated in this study undoubtedly enhance these functions.

4.4. Restoration Measure–Soil–Plant Correlations

Our results revealed a close correlation between the content and transport of Ca

2+, Mg

2+, and, to a lesser extent, K

+ within the body of

M. sativa and its growth in response to the restoration measures (see

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). The modification of FGD gypsum with humic acid and bio-fertilizer notably increased the transport of these beneficial ions (see

Figure 9), with the addition of bio-fertilizer significantly amplifying this effect.

In this study, soluble K

+, Mg

2+, and HCO

3− in the soil had notable effects on root growth, with soluble K

+ exhibiting the most pronounced impact (see

Figure 8). The application of FGD gypsum with humic acid significantly increased the amounts of K

+, Mg

2+, and Ca

2+ ions in the soil. This facilitated the root uptake of these beneficial ions, thereby safeguarding their normal transport within the

M. sativa plant and supporting their corresponding physiological functions (see

Figure 9). Both Mg

2+ and Cl

− in the soil play a role in promoting plant growth by facilitating the selective uptake of Ca

2+ and Mg

2+ by organs and their subsequent transport to leaves.

5. Conclusions

In this study, saline-alkali soil was improved through a combination of biological and chemical methods. FGD gypsum with humic acid contributed to the reduction of soil alkalinity and the increase in the content of beneficial ions in the soil. Additionally, bio-fertilizer clearly enhanced the growth and production indicators of M. sativa. Furthermore, applying FGD gypsum in combination with humic acid and bio-fertilizer improved soil conditions, enhancing the absorption and transport capacity of organs, particularly leaves, for beneficial ions such as K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. This facilitated the ions’ physiological functions more efficiently, mitigating the toxic effects of soil salinization on plants, increasing saline-alkali tolerance, and stimulating plant growth. Under the bio-fertilizer condition, the growth indicators and biomass of M. sativa were higher at the doses of D15 and D7.5. However, B6D7.5 and B6D15 were evidently more conducive to the transport of K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ from the stem to the leaves in M. sativa plants. In terms of M. sativa’s growth, the most beneficial treatment combinations were found to be 15.0 g·kg−1 of FGD gypsum with 1.5 g·kg−1 of humic acid and 6.0 g·kg−1 of bio-fertilizer, or 7.50 g·kg−1 of FGD gypsum with 0.75 g·kg−1 of humic acid and 6.0 g·kg−1 of bio-fertilizer.

Highlights

We tested how FGD gypsum+HA (humic acid) with bio-fertilizer (BF) improves soil functioning and plant biomass

FGD gypsum+HA reduced soil alkalinity and increase beneficial ions’ amount in soil

Including BF strongly promoted the growth and yield of Medicago sativa.

The best combination (g kg-1) was 15.0 FGD gypsum (15.0)+HA (1.5) with BF (6.0)

Via ionic changes, FGD gypsum+HA with BF decreased most Na+ transport in M. sativa

Author Contributions

Data curation, Baole Yu; Formal analysis, Baole Yu; Funding acquisition, Taogetao Baoyin; Investigation, Baole Yu; Methodology, Taogetao Baoyin; Project administration, Taogetao Baoyin; Resources, Taogetao Baoyin; Supervision, Taogetao Baoyin; Writing – original draft, Baole Yu; Writing – review & editing, Lingling Chen.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS34).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the help of Dr Fujin Zhang and Mr. Xiliang Li of the Institute of Grassland Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS).

References

- Alvarez-Ayuso, E., Querol, X., Tomás, A., 2006. Environmental impact of a coal combustion-desulphurisation plant: abatement capacity of desulphurisation process and environmental characterisation of combustion by-products. Chemosphere 65, 2009–2017. [CrossRef]

- Agbede, T.M., Adekiya, A.O., Ogeh, J.S., 2013. Effects of organic fertilizers on yam productivity and some soil properties of a nutrient-depleted tropical alfisol. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 59, 803–822. [CrossRef]

- Arai, M., Miura, T., Tsuzura, H., Minamiya, Y., Kaneko, N., 2018. Two-year responses of earthworm abundance, soil aggregates, and soil carbon to no-tillage and fertilization. Geoderma 332, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D., 2000. Soil agro-chemical analysis. 3rd ed. China Agriculture Press. Beijing, China, 265–267.

- Chang, T., Shao, X.-h., Zhang, J., Mao, J.G., Wei, Y.G., Yin, C., et al., 2013. Effects of bioorganic fertilizer application combined with subsurface drainage in secondary salinized greenhouse soil. J. Food Agric. Environ. 11, 457–460.

- Chen, L.M., Ramsier, C., Bigham, J., Slater, B., Kost, D., Lee, Y.B., Dick, W.A., 2009. Oxidation of FGD-CaSO3 and effect on soil chemical properties when applied to the soil surface. Fuel 88, 1167–1172. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.B., Cai, D., Zhang, L.a., Song, Sh.W., Luo, X., Chen, Y.J., Li, J.F., Xu, T., Mao, D.D., 2021. Advances in mechanisms of magnesium transport and response to magnesium stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 25, 442–447. [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.B., Ritchey, K.D., Baligar, V.C., 2001. Benefits and constraints for use of FGD products on agricultural land. Fuel 80, 821–828. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.X., Huang, J.Y., Kang, Y.M., et al., 2018. Effect of desulfurized gypsum and structure amendment application on soil physical and chemical properties of takyr solonetz soil and rice growth. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 38, 46–51, 57.

- E, Sh.Z., Yuan J., Yao J.B., 2014. The study of nutrients and heavy metals content characteristics in desulfurized gypsum of Jiuquan Steel Group. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 30, 193–196.

- Gao, H.M., Wang, X.P., Qu, Z.H.Y., Yang, J.S., Yao, R.J., 2020. Combining desulfurization gypsum and organic materials to improve soil quality and sunflower growth in Hetao irrigation district. J. Irrig. Drain. 39, 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Hidri, R., Barea, J.M., Mahmoud, O.M., Abdelly, C., Azcón, R., 2016. Impact of microbial inoculation on biomass accumulation by Sulla carnosa provenances, and in regulating nutrition, physiological and antioxidant activities of this species under non-saline and saline conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 201, 28–41. [CrossRef]

- Horlitz, M., Klaff, P., 2000. Gene-specific trans-regulatory functions of magnesium for chloroplast mRNA stability in higher plants. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35638–35645. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Shan, N., Zhong, X.C., 2008. Effects of salt-tolerant forage on bioremediating saline-alkali farmland. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 7, 148–149, 151.

- Li, M., Jiang, L., Sun, Z., Wang, J., Rui, Y., Zhong, L., Wang, Y., Kardol, P., 2012. Effects of flue gas desulfurization gypsum by-products on microbial biomass and community structure in alkaline–saline soils. J. Soils Sediments 12, 1040–1053. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Bai, Sh., Yang, Q.SH., et al., 2021. A review on the saline-alkaline tolerance of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). J. Biol. 38, 98–101, 105. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., Yang, J., Lü, Z., et al., 2011. Effects of different adjustment measures on improvement of light moderate saline soils and crop yield. Trans. CSAE 27, 164–169.

- Lu, P.N., Liu, J.H., Zhao, B.P., Yang, Y.M., Mi, J.Z., Ma, B., Liu, M., 2021. Effects of bio-fertilizer and rotten straw on soil salinity and oat quality in saline-alkaline soil. Chin. J. Ecol. 40, 1639–1649.

- Mao, Y.M., Li, X.P., 2016. Effect of flue gas desulfurization gypsum on coastal saline alkali land improvement. China Environ. Sci. 36, 225–231.

- Mao, Y.M., 2016. Flue gas desulfurization gypsum improving St Alice-sodic soil in tidal flats. D. East China Normal University, Shanghai, China.

- Marschner, H., 1995. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. 2nd ed. Academic Press, Pittsburgh, USA.

- Munns, R., Termaat, A., 1986. Whole-plant responses to salinity. Funct. Plant Biol. 13, 143–160. [CrossRef]

- Nan, J., Chen, X., Chen, C., Lashari, M.S., Deng, J., Du, Z., 2016. Impact of flue gas desulfurization gypsum and lignite humic acid application on soil organic matter and physical properties of a saline-sodic farmland soil in Eastern China. J. Soils Sediments 16, 2175–2185. [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, N., Pazira, E., Neshat, A., Mahmoodabadi, M., Rodríguez Sinobas, L., 2013. Reclamation of calcareous saline sodic soil with different amendments (II): Impact on nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium redistribution and on microbial respiration. Agric. Water Manag. 120, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.C., Li, Y.Y., Yan, H.J., et al., 2009. Effects of inoculating different microorganism agents on the improvement of salinized soil. J. Agro Environ. Sci. 28, 951–955.

- Pang, H.C., Li, Y.Y., Yang, J.S., Liang, Y.S., 2010. Effect of brackish water irrigation and straw mulching on soil salinity and crop yields under monsoonal climatic conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 97, 1971–1977. [CrossRef]

- Pang, H., Li, Y., Yu, T.Y., Liu, G.J., Dong, L.H., 2011. Effects of microorganism agent on soil salination and alfalfa growth under different salt stress. Plant Nutr. Fertil. Sci. 17, 1403–1408.

- Kopittke, P.M., 2012. Interactions between Ca, Mg, Na and K: alleviation of toxicity in saline solutions. Plant Soil 352, 353–362. [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.F., Song, H.P., Fan, Y., Cheng, F.Q., 2021. Effects of activated coke on soil properties and growth of two plant species in saline alkali soil in northern Shanxi Province, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 32, 1799–1806. [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, A.U., Chen, S.S., Tsang, D.C.W., Zhang, M., Vithanage, M., Mandal, S., Gao, B., Bolan, N.S., Ok, Y.S.J.C., 2016. Engineered/designer biochar for contaminant removal/immobilization from soil and water: potential and implication of biochar modification. Chemosphere 148, 276–291. [CrossRef]

- Riens, B., Heldt, H.W., 1992. Decrease of nitrate reductase activity in spinach leaves during a light-dark transition. Plant Physiol. 98, 573–577. [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, S., Dahlawi, S., Naeem, A., Rengel, Z., Naidu, R., 2018. Biochar application for the remediation of salt-affected soils: challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 625, 320–335. [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.Y., Feng, Z.J., Qin, W.F., et al., 2020. Growth of ryegrass under salt-alkali stress and characteristics of ion micro-region distribution. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 29, 52–63.

- Huang, Z.B., Sun, Z.J., Lu, Z.H., 2013 Effects of soil amendments on coastal saline-alkali soil improvement and the growth of plants. Adv. Mater. Res. 634, 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.H.J., 2017. Ecological restoration of typical saline lands in northern China. China Science Publishing & Media LTD. (CSPM). Beijing, China.

- Tang, R.J., Luan, S., 2017. Regulation of calcium and magnesium homeostasis in plants: from transporters to signaling network. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 39, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Liu, S.H.J., Feng, H.J., 2018. Effect of applying the desulfurization gypsum combined with polymaleic anhydride on alkali soil improvement. Soils Fertil. Sci. China 1, 114–120.

- Ghosh, U., Thapa, R., Desutter, T., He, Y., Chatterjee, A., 2017. Saline–sodic soils: potential sources of nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide emissions? Pedosphere 27, 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D., Minkina, T., Yaning, C., Sushkova, S., Chapligin, V.A., Mandzhieva, S., 2016. A review on salinity adaptation mechanism and characteristics of Populus euphratica, a boon for arid ecosystems. Acta Ecol. Sin. 36, 497–503. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Xiao, G.J., Mao, G.L., et al., 2010. Effects of coal-fired flue gas desulfurated waste residue application on saline-alkali soil amelioration and oil-sunflower growth. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 34, 1227–1235.

- Wang, J.M., Bai, Z. K., Ye, C.Q., Xu CH., 2015. Saline and sodic soils properties as affected by the combined application of desulphurization by-product and microbial agent. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 23, 1080–1087. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L., Li, S.Y., Sun, X.Y., Zhang, T., Fu, Y., Zhang, H.L., 2015. Application of salt-isolation materials to a coastal region: effects on soil water and salt movement and photosynthetic characteristics of Robinia pseudoacacia. Acta Ecol. Sin. 35, 1388–1398. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J., Ma, D.M., Zhao, L.J., Ma, Q.L., 2021. Effect of 2,4-table brassinolide on enzyme activity and root ion distribution and absorption in alfalfa seedlings. Acta Agrestia Sin. 29, 1363–1368. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Sun, Z., Han, L., et al., 2017. Subsurface gravel blind ditch increasing improved effects of takyric solonetz by desulfurized gypsum and yield of oil sunflower. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 33, 143–151.

- Wang, X., Ji, X., Liu, L., Ji, B., Tian, Y., 2018. Effect of epibrassinolide on ion absorption and distribution in Medicago species under NaCl stress. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 27, 110–119. [CrossRef]

- White, P.J., Broadley, M.R., 2009. Biofortification of crops with seven mineral elements of ten lacking in human diets iron, zinc, copper, calcium, magnesium, selenium and iodine. New Phytol. 182, 49–84.

- Yang, L.L., Li, F., Chen, Y., et al., 2020. Optimization and improvement of spectrophotometry method to determine cation exchange capacity in soil. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 36, 119–122.

- Yang, J., Sun, Z., Liu, J., et al., 2015. Effects of saline improvement and leaching of desulphurized gypsum combined with furfural residue in newly reclaimed farmland crack alkaline soil. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 31, 128–135.

- Yang, J.S., Yao, R.J., Wang, X.P., Xie, W.P., 2016. Research on ecological management and ecological industry development model of saline-alkali land in the Hetao Plain, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 36, 7059–7063. [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.T., Zhou, Q.Y., Li, S.M., Ma, B., 2020. Effects of plastic film-mulching and irrigation on the salt ion distribution and biomass of maize in coastal saline-alkali soil. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 38, 74–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.F., Zhou, S., Fan, H., 2002. Addendum of halophyte species in China. Chin. Bull. Bot. 19,611–613,628.

- Zhao, W., Zhou, Q., Tian, Z.Z., Cui, Y.T., Liang, Y., Wang, H.Y., 2020. Apply biochar to ameliorate soda saline-alkali land, improve soil function and increase corn nutrient availability in the Songnen Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 722, 137428. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Wang, S., Li, Y., Liu, J., Zhuo, Y.Q., Zhang, W.K., Wang, J., Xu, L.Zh., 2018. Long-term performance of flue gas desulfurization gypsum in a large-scale application in a saline-alkali wasteland in northwest China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 261, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.SH., Hao, B.P., Feng, Y.CH., Ding, Y.Ch., Li, Y.F., Xue, ZH.Q., Cao, W.D., 2012. Effects of different saline-alkali land amendments on soil physicochemical properties and alfalfa growth and yield. Chin. J. Eco-Agriculture. 20, 1216–1221. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Li, Z., Zhang, Z., You, L., Xu, L., Huang, H., Wang, X., Gao, Y., Cui, X., 2021. Treatment of the saline-alkali soil with acidic corn stalk biochar and its effect on the sorghum yield in western Songnen Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 797, 149190. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Liu, X., Meng, Q., Zeng, X., Zhang, J., Li, D., Wang, J., Du, W., Ma, X., 2019. Additional application of aluminum sulfate with different fertilizers ameliorates saline-sodic soil of Songnen Plain in Northeast China. J. Soils Sediments 19, 3521–3533. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.H., Feng, R.Z., Shi, S.L., Kou, J.T., 2015. Nitric oxide protection of alfalfa seedling roots against salt-induced inhibition of growth and oxidative damage. Acta Ecol. Sin. 35, 3606–3614. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of restoration strategies on soil pH, salinity, SAR, and ESP. B: bio-fertilizer, D: FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of restoration strategies on soil pH, salinity, SAR, and ESP. B: bio-fertilizer, D: FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of restoration strategies on the content of water-soluble ions. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effects of restoration strategies on the content of water-soluble ions. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of restoration strategies on the height, root length and root diameter of Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of restoration strategies on the height, root length and root diameter of Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of restoration strategies on the aboveground biomass and belowground biomass of the Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of restoration strategies on the aboveground biomass and belowground biomass of the Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of restoration strategies on the content of ions in each organ of Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of restoration strategies on the content of ions in each organ of Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of restoration strategies on the K+/Na+, Ca2+/Na+, Mg2+/Na+ in each organ of Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of restoration strategies on the K+/Na+, Ca2+/Na+, Mg2+/Na+ in each organ of Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of restoration strategies on cation transport selectivity ratio of ions in Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters and ns represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of restoration strategies on cation transport selectivity ratio of ions in Medicago sativa. B indicates bio-fertilizer, D indicates FGD gypsum, the superscript indicates application amount. Different letters and ns represent the significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis of plant growth, ion partitioning, transport and soil environmental factors under different remediation measures. TS: soil solidity, B-L, B-S, B-R, B-T: biomass of leaf, stem and root, respectively. Na_L, K_L, Ca_L, Mg-L were content of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in leaf; Na_S, K_S, Ca_S, Mg-S: content of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in stem,Na_R, K_R, Ca_R, Mg_R: content of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in root, respectively. L_K/Na、L_Ca/Na、L_Mg/Na were K+/Na+, Ca+/Na+, Mg+/Na+ of leaf, S_K/Na, S_Ca/Na, S_Mg/Na were K+/Na+, Ca+/Na+, Mg+/Na+ of stem, R_K/Na, R_Ca/Na, R_Mg/Na were K+/Na+, Ca+/Na+, Mg+/Na+ of root, respectively. K_R→S, Ca_R→S, Mg_R→S: transport selectivity ratio of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ from root to stem, K_S→L, Ca_S→L, Mg_S→L: transport selectivity ratio of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ from stem to leaf. Same as below.

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis of plant growth, ion partitioning, transport and soil environmental factors under different remediation measures. TS: soil solidity, B-L, B-S, B-R, B-T: biomass of leaf, stem and root, respectively. Na_L, K_L, Ca_L, Mg-L were content of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in leaf; Na_S, K_S, Ca_S, Mg-S: content of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in stem,Na_R, K_R, Ca_R, Mg_R: content of Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in root, respectively. L_K/Na、L_Ca/Na、L_Mg/Na were K+/Na+, Ca+/Na+, Mg+/Na+ of leaf, S_K/Na, S_Ca/Na, S_Mg/Na were K+/Na+, Ca+/Na+, Mg+/Na+ of stem, R_K/Na, R_Ca/Na, R_Mg/Na were K+/Na+, Ca+/Na+, Mg+/Na+ of root, respectively. K_R→S, Ca_R→S, Mg_R→S: transport selectivity ratio of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ from root to stem, K_S→L, Ca_S→L, Mg_S→L: transport selectivity ratio of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ from stem to leaf. Same as below.

Figure 9.

RDA analysis of plant growth, ion partitioning, transport and soil environmental factors under different remediation measures a. effect of soil salinity- alkalinity properties on plant growth and yield b. effect of soil water-soluble cations on plant growth and yield c. effect of soil water-soluble cations on contents of ions in plant d. effect of soil water-soluble cations on transportation of ions in plant.

Figure 9.

RDA analysis of plant growth, ion partitioning, transport and soil environmental factors under different remediation measures a. effect of soil salinity- alkalinity properties on plant growth and yield b. effect of soil water-soluble cations on plant growth and yield c. effect of soil water-soluble cations on contents of ions in plant d. effect of soil water-soluble cations on transportation of ions in plant.

Figure 10.

Structural equation modeling of the relationship among soil properties, plant growth and ion transport characteristics under different remediation measures. The green arrow represents positive correlation, the red arrow represents negative correlation, the number on the arrow is the normalized path coefficient, and the width of the arrow indicates the path coefficient intensity. * indicates significant difference at 0.05 level. ** indicates significant difference at 0.01 level. *** indicates significant difference at 0.001 level.

Figure 10.

Structural equation modeling of the relationship among soil properties, plant growth and ion transport characteristics under different remediation measures. The green arrow represents positive correlation, the red arrow represents negative correlation, the number on the arrow is the normalized path coefficient, and the width of the arrow indicates the path coefficient intensity. * indicates significant difference at 0.05 level. ** indicates significant difference at 0.01 level. *** indicates significant difference at 0.001 level.

Table 1.

Water-soluble ions in the initial soil and flue gas desulfurization gypsum used in the present study.

Table 1.

Water-soluble ions in the initial soil and flue gas desulfurization gypsum used in the present study.

| Index |

Soil |

FGD Gypsum |

| pH |

8.90 |

7.23±0.06 |

| Water content/% |

|

13 |

| EC/μm·cm-1

|

367.79 |

|

| Na+/ mg·kg-1

|

54.2 |

574.0 |

| K+/ mg·kg-1

|

10.6 |

19.6 |

| Ca2+/ mg·kg-1

|

78.5 |

2731.0 |

| Mg2+/ mg·kg-1

|

24.8 |

55.0 |

| Cl-/ mg·kg-1

|

4.4 |

435.0 |

| SO42-/ mg·kg-1

|

15.6 |

7950.0 |

| HCO3-+ CO32-/ mg·kg-1

|

363.0 |

126.0 |

| Exchangeable Na/ cmol(Na+)·kg-1

|

0.33 |

2.59 |

Table 2.

The treatment scheme of different remediation measurement.

Table 2.

The treatment scheme of different remediation measurement.

| Treatment |

Bio-Fertilizer

/g·kg-1

|

FGD Gypsum+Humic Acid

/g·kg-1

|

| B0

|

D0

|

0 |

0 |

| D7.5

|

0 |

7.5+0.75 |

| D15

|

0 |

15.0+1.5 |

| D30

|

0 |

30.0+3.0 |

| B6

|

D0

|

6.0 |

0 |

| D7.5

|

6.0 |

7.5+0.75 |

| D15

|

6.0 |

15.0+1.5 |

| D30

|

6.0 |

30.0+3.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).