1. Introduction

Currently, the area of soda saline-alkali soil in the Songnen Plain of China exceeds 4.97 × 10

6 ha. This region is recognized as one of the three major global concentrations of soda saline-alkali soil[

1], primarily located in the provinces of Jilin, Inner Mongolia, and Heilongjiang. The western region of Jilin Province is a crucial base for commodity grain production; however, it is significantly affected by saline-alkali soil. Rice is one of the primary crops cultivated in this area. The presence of saline-alkali soil not only adversely impacts the growth of local rice but also contributes to a shortage of soil suitable for rice seedling raising.

The key components contributing to soil salinization in saline-alkali soils are sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃). The elevated salinity and alkalinity adversely affect soil properties, including aeration and permeability. When the soil-to-water ratio is 5:1, the pH of the surface soil (0-20 cm) can reach 10.16, and the sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) can attain 196.64 (mmol L⁻¹)¹/² [

2]. The significant adsorption of sodium ions (Na⁺) by the soil enhances the hydrophilicity of soil colloids, leading to soil dispersion and structural deterioration. This process limits nutrient availability and reduces soil fertility [

3]. The high degree of sodification and low fertility of these soils are major drawbacks that impede their use in rice seedling raising and other agricultural practices [

4].

Farmers in areas with soda saline-alkali soils often utilize mildly saline-alkali soil for simple acid adjustment treatments as seedbed soil due to a scarcity of suitable soil resources. However, this practice leads to the depletion of soil resources and degradation of the soil environment. Inadequate improvement measures can also harm seedlings and potentially reduce crop yields. Therefore, addressing the issue of soil for rice seedling raising has become an urgent task. The application of rapidly improved soda saline-alkali soil for rice seedling raising can enhance the availability of quality seedling-raising soil resources, providing an effective solution to this challenge.

Gypsum is one of the most significant and widely utilized amendments for the improvement of saline-alkali soils. It enhances soil bulk density, hydraulic conductivity, and macroporosity[

5]. Gypsum ameliorates soda saline-alkali soils by supplying calcium ions (Ca²⁺), which replace excessive monovalent sodium ions (Na⁺) at cation exchange sites within the soil [

6]. Soil colloids exhibit a strong affinity for divalent Ca²⁺, rendering them more stable than monovalent Na⁺[

7]. The displaced Na⁺ is subsequently leached away with irrigation water. However, gypsum has low solubility, and in the absence of irrigation or rainfall, there is a risk of insufficient hydraulic conductivity. The combined application of straw organic matter can mitigate this issue. The macromolecular organic acids generated during straw decomposition readily bind with Ca²⁺ ions, facilitating the dissolution of gypsum[

8]. Additionally, returning straw to the soil releases a substantial amount of nutrients. Nie et al. [

9]observed that long-term straw return increased soil organic carbon and total nitrogen by 8.85% to 15.01%, effectively enhancing soil fertility. The application of straw can also modify the soil carbon-to-nitrogen ratio and promote nutrient cycling, thereby benefiting crop growth [

10,

11].

Soda saline-alkali soil typically leads to the fixation of essential nutrients, such as phosphorus and calcium, under conditions of high salinity and alkalinity [

12]. Additionally, it contributes to a reduction in nitrogen accumulation levels in plants [

13]. Extreme ratios of Na

+/Ca

2+, Na

+/K

+, Ca

2+/Mg

2+, and Cl

-/NO

3- are prone to occur, inhibiting the ion activity of nutrient elements [

14]. The application of sulfuric acid has been shown to significantly lower the pH of saline-alkali soil, promoting the dissolution of Ca

2+ and enhancing the Na-Ca exchange process, as well as Na leaching in such soils [

15]. Furthermore, sulfuric acid improves nutrient availability and increases both the nutrient utilization and absorption rates of crops [

16]. The use of chemical fertilizers supplies essential nutrient elements to the soil, thereby improving nutrient availability and mitigating the detrimental effects of salinity on plants [

14,

17]. The combined application of inorganic and organic fertilizers has been found to reduce soil salinity and pH value [

18]. Moreover, studies have shown that the application of chemical fertilizers combined with straw in saline-alkali soil can alter soil aggregates, enhance soil carbon sequestration capacity [

19], and increase nutrient absorption, plant vitality, and crop yield [

20]. Currently, the co-application of gypsum, straw, and sulfuric acid or inorganic fertilizers for the amelioration of saline-alkali soils is relatively uncommon. This study aims to evaluate the effects of applying gypsum and straw, along with the addition of sulfuric acid and fertilizers, on saline-alkali soil. Specifically, our objectives are: (1) to investigate the response of soil salinity and fertility following various treatments; and (2) to reflect the impact of different improvement treatments on the growth of rice seedlings in saline-alkali soil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

The soda saline-alkali soil utilized in this experiment was sourced from Qian'an County, Songyuan City, Jilin Province (44°52′49″N, 124°02′32″E), which is located within the Songnen Plain and is classified as a typical meadow alkali soil. This region is characterized by a middle temperate continental monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of 5.6°C, an annual sunshine duration of 2860 hours, and a total accumulated temperature of 2885°C. The frost-free period lasts approximately 140 days, and the average annual precipitation is recorded at 420 mm. The soil has a pH value of 9.19, an organic carbon content of 8.57 g·kg⁻¹, an electrical conductivity of 0.288 ms·cm⁻¹, an exchangeable sodium content of 5.59 cmol·kg⁻¹, a cation exchange capacity (CEC) of 9.32 cmol·kg⁻¹, and a total alkalinity of 1.22 cmol·kg⁻¹.

The straw used in this experiment was sourced from corn straw collected from the field. After crushing, the straw measured approximately 1 cm in length. The organic carbon content was measured at 396.7 g·kg⁻¹, while the total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and total potassium contents were 6.59 g·kg⁻¹, 2.20 g·kg⁻¹, and 7.32 g·kg⁻¹, respectively.

In the rice seedling experiment, the control group utilized farmers' seedling raising soil (ZCK) alongside JCK. This soil was sourced from the seedling raising area at Taohe Farm, situated in Linhai Town, Taobei District, Baicheng City, Jilin Province, where agricultural seedling conditioning agents had been incorporated by farmers. The soil exhibited a pH value of 6.27, an organic carbon content of 18.01 g·kg⁻¹, an electrical conductivity of 2.69 ms·cm⁻¹, alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen of 156.5 mg·kg⁻¹, available phosphorus of 42.48 mg·kg⁻¹, available potassium of 175.2 mg·kg⁻¹, exchangeable sodium of 0.53 cmol·kg⁻¹, and total alkalinity of 0.23 cmol·kg⁻¹.

2.2. Experimental Design and Soil Sampling

Four treatments were established: JCK control (no amendment), JCW (2% gypsum and 6% straw), JCWH (2% gypsum, 6% straw, and an sulfuric acid application), and JCWF (2% gypsum, 6% straw, and a chemical fertilizer application). The amendments were applied in proportion to the soil weight, with each treatment replicated three times. The sulfuric acid application involved the addition of 40 mL of a (1+1) sulfuric acid solution per kilogram of soil. The chemical fertilizer application consisted of the addition of 4 g of urea, 8 g of diammonium hydrogen phosphate, and 4 g of potassium sulfate per kilogram of soil.

The following steps were adopted to improve soil samples: 3 kg of soda saline-alkali soil was uniformly mixed with the amendment and subsequently placed into a 5 L plastic bucket. The bottom of the bucket was evenly perforated to ensure proper drainage. Initially, a substantial volume of water was utilized for leaching, with a total of 10 L of water applied over a period of 8 days. Following this, the mixture was maintained at field capacity and room temperature, with regular turning and mixing. After 8 months, the cultivation process concluded, and samples were collected. In both 2021 and 2022, the soil was treated with the same amendment following identical procedures once a year. After air-drying, the soil samples obtained each year were passed through a 2 mm sieve to separate undecomposed straw, after which the content of soil organic carbon components was determined.

2.3. Soil Analysis and Rice Seedling Determination

The pH and conductivity of the soil were measured using the electrode method at a soil-to-water (w/v) ratio of 1:5. Soil exchangeable sodium was determined through ammonium acetate and ammonium hydroxide exchange, followed by flame photometry. The total alkalinity of the soil was calculated as the sum of the soluble carbonates and bicarbonates, which were determined by extracting the soil with a solution at a soil-to-water (w/v) ratio of 1:5 and titrating with a 0.1M hydrochloric acid solution.

The separation of soil humus components was conducted following the modified method of soil humus composition as described by Zhang et al. [

21]. Soil samples were extracted using a mixed solution of sodium hydroxide (0.1 M) and sodium pyrophosphate (0.1 M), followed by centrifugation and filtration. The remaining soil residue was identified as humin (HU), while the filtrate constituted the extracted humus extract (HE). Subsequently, the filtrate was acidified to a pH of 1 to facilitate the separation of humic acid (HA) and fulvic acid (FA) from HE.

The contents of soil organic carbon (SOC), humic acid carbon (HAC), and fulvic acid carbon (FAC) were determined using the K

2Cr

2O

7 oxidation method followed by FeSO

4 titration. The PQ value, calculated as PQ = HAC / (HAC + FAC), serves as an indicator of the degree of soil humification. Both HA and FA solutions were appropriately diluted, and their absorbances at 400 nm and 600 nm (A

400 and A

600) were measured respectively. The value of Δlog K was computed as Δlog K = log A

400 - log A

600. This Δlog K value reflects the complexity of the soil humus molecular structure [

22]. A larger Δlog K indicates a lower degree of aromaticity and condensation in the molecular structure, suggesting a simpler structure of humic substances.

The determination of leaf age, plant height, root length, and dry weight of rice seedlings was conducted using the following methods. The roots of the seedlings were washed with water, and surface moisture was removed using absorbent paper. Subsequently, the leaf age, plant height, and root length of the seedlings were measured. The seedlings were then placed in an oven at 105 °C for 30 minutes for blanching, followed by drying in an oven at 70 °C to 80 °C until a constant weight was achieved, at which point they were weighed.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (IBM Statistics 22.0). The differences between treatment means were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan's new multiple range test to evaluate significance at the 5% level. The results of these tests were plotted, and Pearson correlation analysis was performed using Origin Pro 2018 software.

3. Results

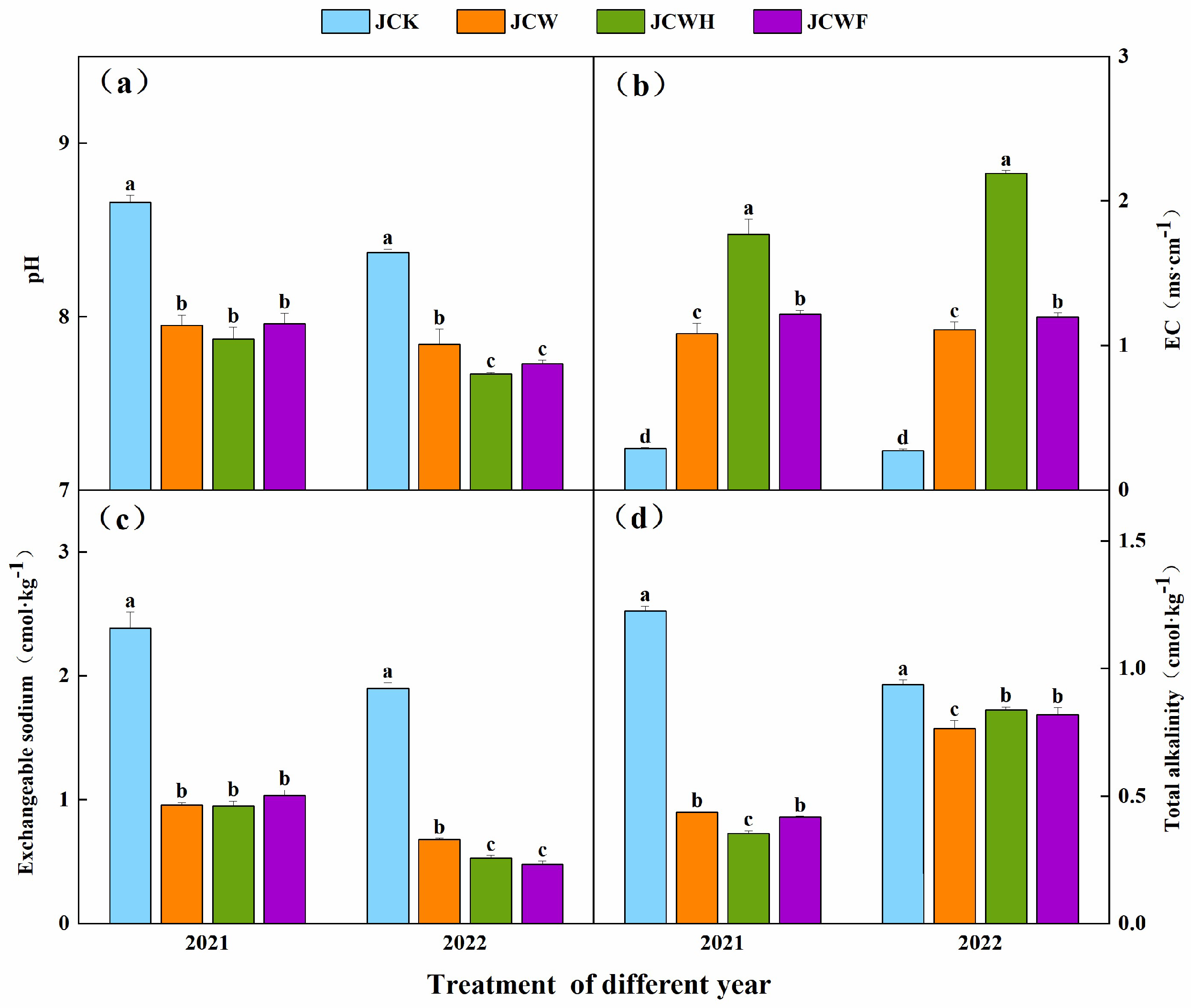

3.1. Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

Two years of experimental data indicated that, overall, with the increase in years, the soil pH and exchangeable sodium across all amendment treatments significantly decreased (

Figure 1a, c), while soil electrical conductivity (EC) significantly increased (

Figure 1b). The total alkalinity of the soil exhibited a trend of initially decreasing followed by an increase (

Figure 1d). Compared to the JCK treatment, the average pH values for the JCW, JCWH, and JCWF treatments were significantly reduced by 0.53 to 0.79 units, respectively. Meanwhile, the soil EC value significantly increased by 3.05 to 7.20 times, with the JCWH treatment exhibiting the highest EC value. The soil exchangeable sodium for the JCW, JCWH, and JCWF treatments significantly decreased, from an average of 1.93 mmol·kg⁻¹ in JCK to 0.43, 0.38, and 0.31 mmol·kg⁻¹ in 2022 (p < 0.05), respectively. For total alkalinity, the average reduction in each treatment in 2021 was greater than that in 2022.

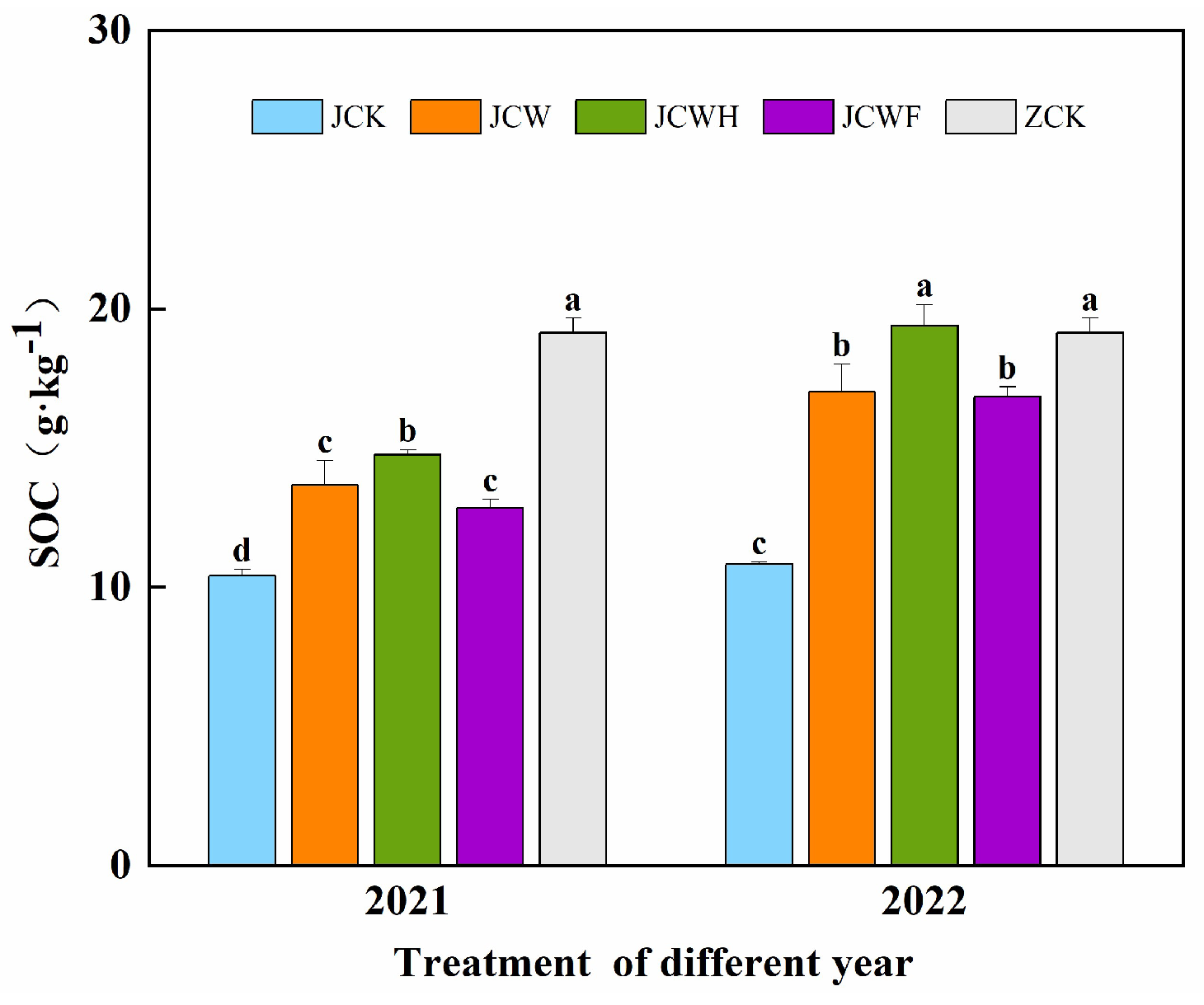

3.2. Soil Organic Carbon Components and Humification Degree

In this study, we applied the improved soil obtained over two years to rice seedling raising. We investigated the organic carbon content and the degree of humification of the seedling raising soil, comparing it with the farmer's seedling raising soil (ZCK). The average soil organic carbon (SOC) of the seedling raising soil across all improved treatments ranged from 10.42 to 19.39 g·kg⁻¹ (

Figure 2). Overall, the average SOC for each treatment in 2022 was 24.4% to 31.4% higher than that in 2021. Compared to JCK, the amendment treatments significantly increased the soil SOC by 23.3% to 78.9% (p < 0.05). Among all the amendment treatments, the JCWH treatment, which included additional sulfuric acid, exhibited the highest SOC levels over the two years, measuring 14.76 and 19.39 g·kg⁻¹, respectively. Notably, we found no significant difference in SOC content between the JCWH treatment soil over the two years and the ZCK soil.

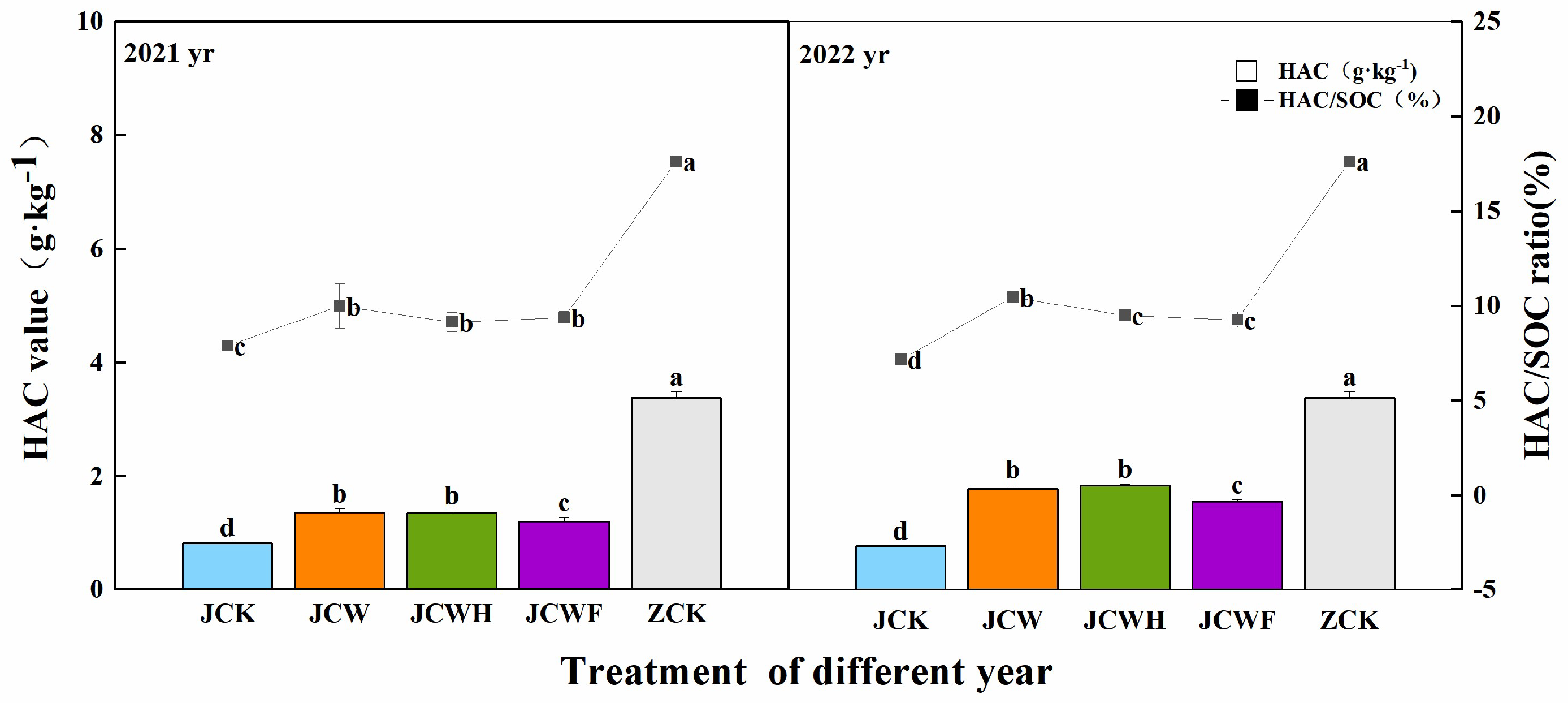

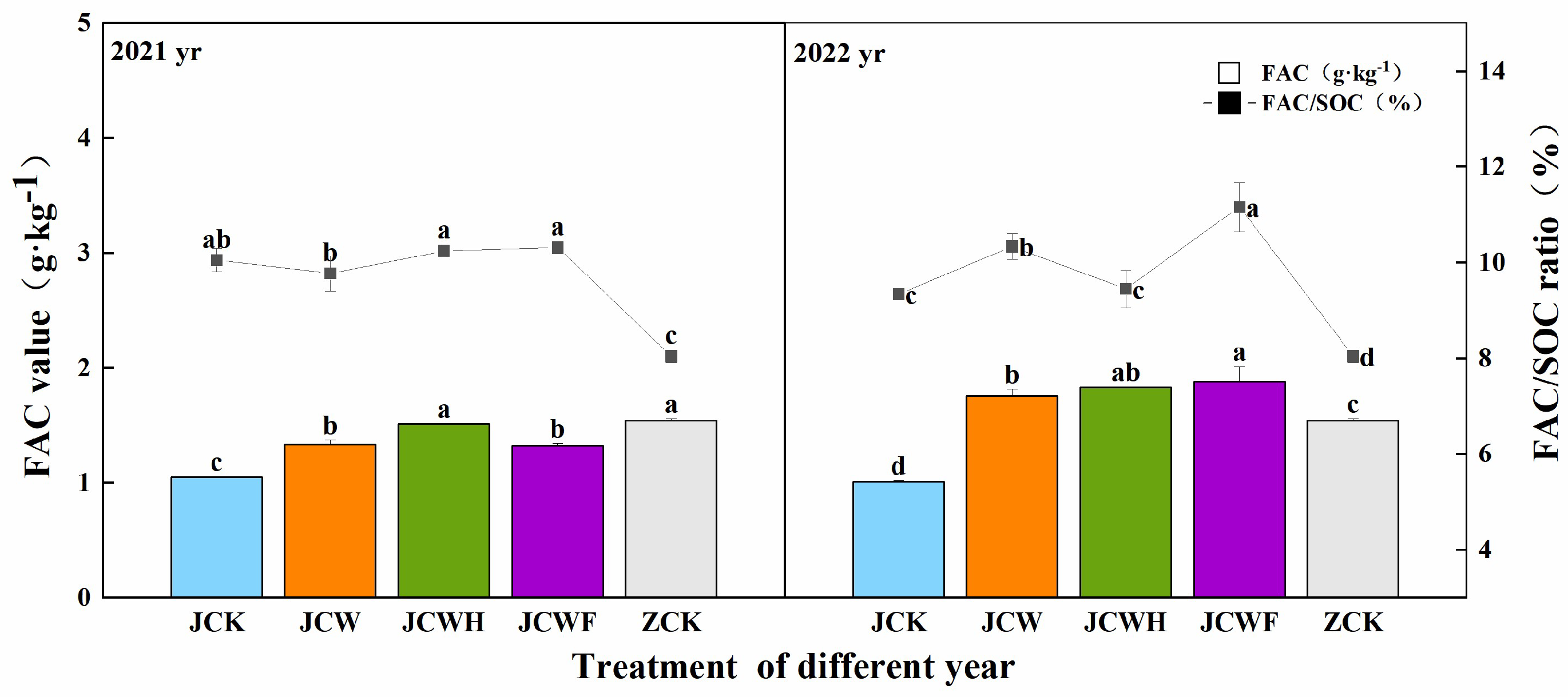

All amendment treatments resulted in a year-on-year increase in both humic acid carbon (HAC) and fulvic acid carbon (FAC) in the soil (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Compared to the control group (JCK), the HAC increased by 46.3%, reaching 137.2%, while the FAC rose by 26.4% to 86.0%. As shown in

Figure 3, the increases in HAC for JCW and JCWH were more pronounced than that of JCWF over the two-year period. However, despite these improvements, a notable disparity remained when comparing the HAC of the farmer's seedling raising soil (ZCK), which was 3.38 g·kg⁻¹, with that of the amendment treatments. In 2022, the HAC/SOC ratios for both JCW and JCWH increased compared to 2021, while JCWF experienced a slight decrease.

Figure 4 illustrates that among the various improved treatments, the increases in FAC for JCWH and JCWF were more significant than that of JCW. Nevertheless, the FAC/SOC ratio for JCWH exhibited a downward trend, decreasing by 7.7% over the two years, whereas the FAC/SOC ratios for JCW and JCWF showed upward trends, increasing by 5.8% and 8.2%, respectively. Importantly, after two years, the FAC of all amendment treatments significantly exceeded that of ZCK soil.

In comparison to JCK, the PQ values of all amendment treatments exhibited an increase over the two-year period (

Table 1). The JCW treatment recorded the highest PQ value, with measurements of 50.46% and 50.30% in the respective years, followed by JCWH. Notably, the JCWH treatment showed an upward trend across the two years, whereas the JCWF treatment showed a downward trend. Compared with JCK, the HA⊿lgK values for the JCW, JCWH, and JCWF treatments significantly increased, ranging from 11.4% to 35.9%, with a consistent year-on-year rise. Among these, the JCWH treatment displayed the highest HA⊿lgK value. Conversely, for FA⊿lgK, the values for each amendment treatment were lower than those of JCK over the two years, reflecting a decrease of 2.3% to 12.9%, which also declined year by year.

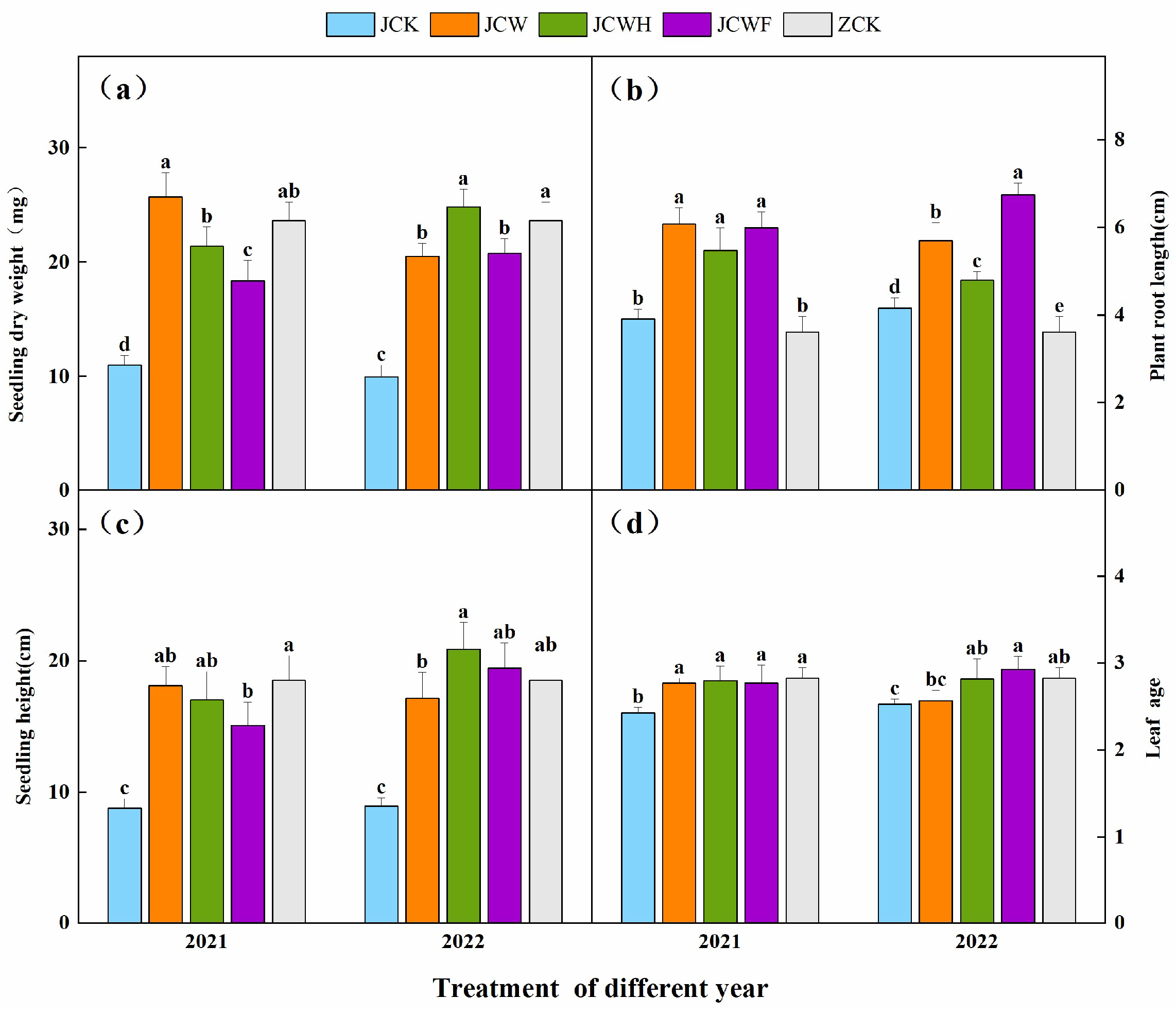

3.3. Growth Status of Rice Seedling

Two years of experimental data indicate that, overall, as the years progressed, the dry weight, plant height, and root length of seedlings treated with JCW exhibited a decreasing trend. In contrast, the dry weight and plant height of seedlings treated with JCWH and JCWF showed significant increases. Notably, the root length of seedlings under the JCWF treatment was longer in 2022. The variation in leaf age across all amendment treatments was minimal. Compared to the control group JCK, all amendment treatments significantly enhanced the dry weight of seedlings by 67.31% to 149.21%, increased root length by 15.38% to 62.26%, and elevated plant height by 71.7% to 133.5%. After two years, seedlings treated with JCWH reached a height of 20.91 cm and a weight of 24.83 mg, demonstrating no significant difference when compared to the farmer control ZCK (p > 0.05).

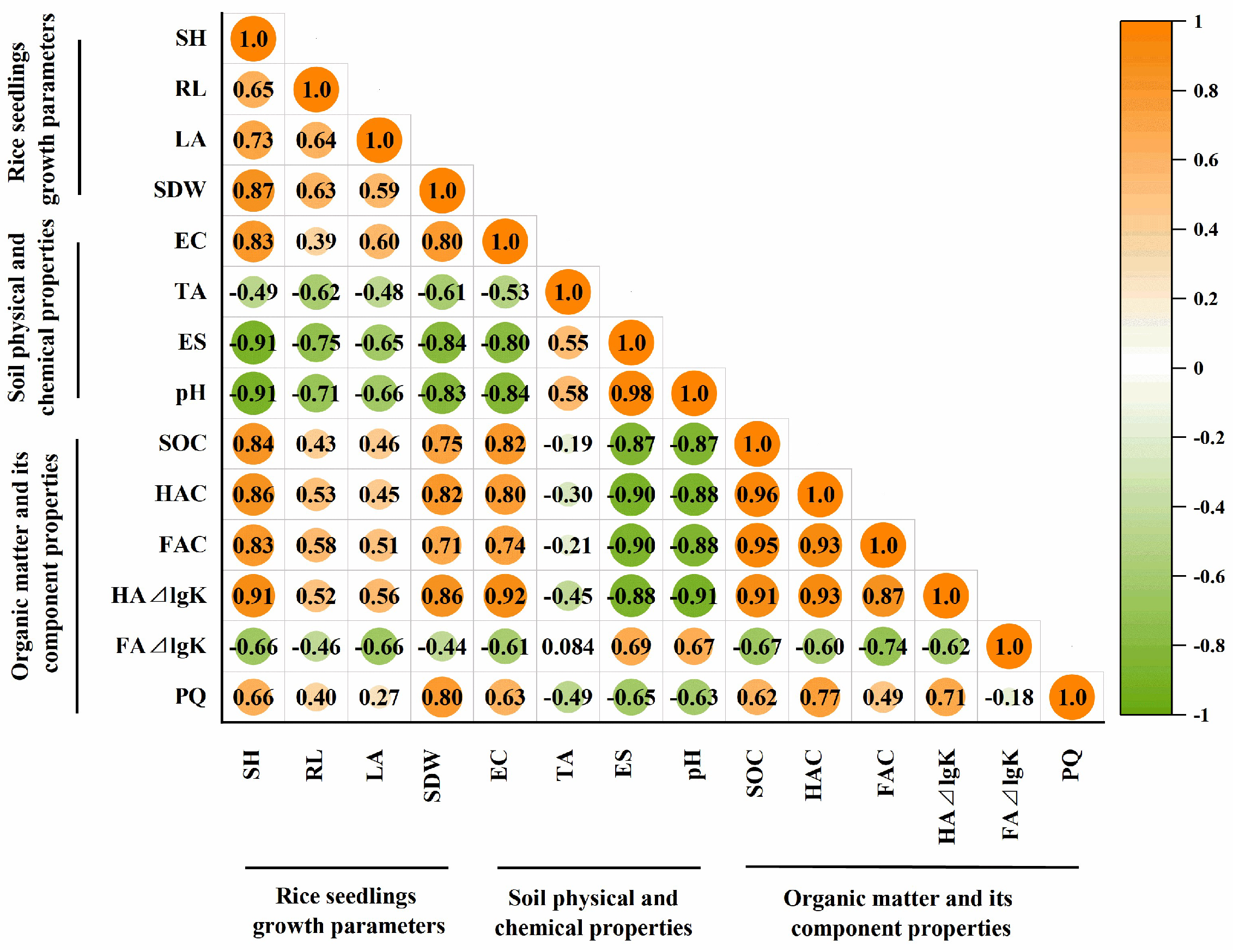

Correlation analysis can further elucidate the relationship between the physical and chemical properties of amended soils, soil organic carbon and its components, and the growth parameters of rice seedlings (see

Figure 6). All amendment treatments, including the application of straw, gypsum, sulfuric acid, and chemical fertilizers in soda saline-alkali soil, have demonstrated significant effects in improving soil physical and chemical properties, enhancing soil fertility, and promoting seedling growth. The seedling growth parameters, such as shoot height (SH), leaf age (LA), and seedling dry weight (SDW), exhibit a negative correlation with the physical and chemical properties of soils, including total alkalinity (TA), exchangeable sodium (ES), and pH, while showing a significantly positive correlation with soil EC. Furthermore, the seedling growth parameters (SH, root length (RL), LA, and SDW) display a positive correlation with soil fertility-related parameters, including SOC, HAC, FAC, HA⊿lgK and PQ value, while demonstrating a negative correlation with FA⊿lgK.

Figure 5.

Effects of different improvement treatments on soil FAC content and FAC/SOC ratio . Control (JCK): with no amendments;straw+gypsum treatment(JCW);straw+gypsum+sulfuric acid treatment(JCWH);straw+gypsum+chemical fertilizer treatment(JCWF);the farmer's seedling raising soil(ZCK).The symbol notation is the same as in

Figure 1.

Figure 5.

Effects of different improvement treatments on soil FAC content and FAC/SOC ratio . Control (JCK): with no amendments;straw+gypsum treatment(JCW);straw+gypsum+sulfuric acid treatment(JCWH);straw+gypsum+chemical fertilizer treatment(JCWF);the farmer's seedling raising soil(ZCK).The symbol notation is the same as in

Figure 1.

Figure 6.

Pearson′s correlation analysis of seedling quality parameters with indicators relative to soil salinity、alkalinity and fertility under different improvement treatments.SH seedling height,RL root length,LA leaf age,SDW seedling dry weight,EC electrical conductivity,TA total alkalinity,ES exchangeable sodium,SOC soil organic carbon,HAC humic acid carbon,FAC fulvic acid carbon,HA⊿lgK color tone coefficient of humic acid,FA ⊿lgK color tone coefficient of fulvic acid,PQ humification coefficient.

Figure 6.

Pearson′s correlation analysis of seedling quality parameters with indicators relative to soil salinity、alkalinity and fertility under different improvement treatments.SH seedling height,RL root length,LA leaf age,SDW seedling dry weight,EC electrical conductivity,TA total alkalinity,ES exchangeable sodium,SOC soil organic carbon,HAC humic acid carbon,FAC fulvic acid carbon,HA⊿lgK color tone coefficient of humic acid,FA ⊿lgK color tone coefficient of fulvic acid,PQ humification coefficient.

4. Discussion

4.1. Short-Term Improvement Enhances the Physicochemical Properties of Saline-Alkali Soil

Under the 2-year short-term soil improvement involving gypsum, straw, and other amendments, notable changes occurred in the physical and chemical properties of the soil. Specifically, soil pH and exchangeable sodium decreased significantly over the years, while the electrical conductivity (EC) value exhibited an annual increase. The total alkalinity displayed a trend of initially decreasing and then increasing (

Figure 1). In alignment with the experimental findings of Abdel-Fattah [

23] and GHAFOOR [

24], this study also observed a significant reduction in soil pH and exchangeable sodium. The observed decrease in pH can be attributed to the presence of acidic substances generated by the hydrolysis of sulfuric acid and chemical fertilizers [

25], as well as the macromolecular carboxyl groups formed through the humification of straw [

26,

27], which exert neutralizing effects on alkaline ions. The reduction in exchangeable sodium primarily resulted from the enhancement of the Ca-Na exchange process facilitated by gypsum [

28,

29]. Moreover, Ca²⁺ ions reduced the electrokinetic potential of soil colloid surfaces, promoting colloid coagulation, which subsequently increased soil hydraulic conductivity and enhanced the leaching of sodium [

30,

31]. The extent of the decrease in pH and exchangeable sodium across treatments was ranked as follows: JCWH > JCWF > JCW (

Figure 1a, c), with JCWH demonstrating the most effective results. While sulfuric acid lowered the pH of saline-alkali soil, it also facilitated the dissolution of deposited calcium in the soil, thereby enhancing Ca-Na replacement [

15].

Similar to the research trends observed by Zhao[

32], El Hasini[

33], and others, this study found that the EC values of all amendment treatments were higher than those of the control (

Figure 1b). This phenomenon can be attributed to the extended cultivation time of the soil, which facilitates a more complete dissolution of soluble salts [

34]. Zhao et al. [

32] also reported that the application of gypsum and straw to saline-alkali soil resulted in decreases in soil pH and exchangeable sodium percentage(ESP), while the EC increased by 31.79% compared to the control. Furthermore, the concentrations of ions detrimental to plant growth, such as Na

+ and Cl

-, were significantly reduced, whereas the levels of beneficial ions, such as Ca

2+ and SO

42-, were significantly increased. These outcomes resulted from the effective improvement process.

In this study, the total alkalinity of all amendment treatments in 2021 was significantly reduced. However, an upward trend was observed in 2022 (

Figure 1d). The total input of straw carbon was identified as a key driving factor [

35]. In carbon-rich and alkaline soils, the continuous application of substantial amounts of straw promoted the mineralization of soil organic carbon (SOC) and resulted in the accumulation of calcium bicarbonate, thereby increasing total alkalinity. This impact can be mitigated by reducing the quantity of straw applied.

4.2. Short-Term Improvement Promotes Soil Fertility Enhancement

Organic matter is widely recognized as a crucial component of soil fertility. In a rice seedling raising experiment utilizing short-term improvement, the organic carbon (SOC) in the seedling raising soil exhibited significant enhancement (

Figure 2). In alkaline soils, gypsum, which serves as an exogenous source of calcium, exerts a strong bridging effect that facilitates the connection between organic carbon and minerals, thereby promoting soil clay flocculation [

36]. This function enhances the stability and accumulation of SOC [

37,

38]. Furthermore, decomposed substances from straw can act as a cementing agent [

39], contributing to the formation of microstructures, such as calcium-bonded organic carbon [

40]. Research has demonstrated a positive correlation between exchangeable calcium (ECa) and SOC [

41]. Our findings indicated that after two years of improvement, the SOC of the JCWH treatment soil was the highest and did not show significant differences compared to that of the ZCK soil.

The composition of soil organic matter profoundly influences soil properties and the multifunctionality of ecosystems. Humic acid (HA) and fulvic acid (FA) are the primary active components of organic matter. HA significantly impacts soil fertility and structural stability [

42]. The aromatic compounds in HA, including carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, can form organic-inorganic complexes with polyvalent cations at the active sites of mineral colloids, thereby enhancing the formation of microaggregates [

43]. In this study, all amendment treatments significantly increased the amounts of HAC and FAC in the soils (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In accordance with the findings of Li et al. [

44], the FAC/SOC ratio in 2022 decreased in the JCWH treatment, while the HAC/SOC ratio increased, indicating a transformation trend from FA to HA. From the perspective of humic acid accumulation, the JCWH treatment demonstrates distinct advantages.

In this study, after two years of short-term improvement, the PQ values and ΔlgK values of HA in all amendment treatments were found to be higher than those of the control, whereas the ΔlgK values of FA were lower than those of the control (see

Table 1). The addition of straw organic materials promotes the renewal and activation of soil organic matter, thereby enhancing the degree of humification in the soil [

45]. Notably, the PQ value of the JCWH treatment increased progressively over the years, while that of the JCWF treatment exhibited a year-on-year decline. This indicates that the application of sulfuric acid significantly enhances the quality of soil humus [

46]. The HA ΔlgK value of the JCWH treatment soil was the highest, suggesting that the addition of sulfuric acid effectively reduces both the oxidation and aromatization degrees of HA, increases the aliphatic carbon content, and simplifies its structure [

47].

4.3. Short-Term Improvement Enhances the Growth Status of Seedlings

The salt and alkali stress associated with soda saline-alkali soil poses significant threats to plant growth[

48,

49], as it impedes the absorption and transportation of essential nutrient ions. This study conducted short-term improvement aimed at rapidly improving soda saline-alkali soil, thereby ameliorating the saline-alkali stress environment and enhancing the utilization efficiency of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus, which in turn promotes nutrient absorption by plants[

50]. Following the soil amendment treatments, marked increases were observed in the dry weight, root length, and height of rice seedlings(

Figure 5). The addition of exogenous calcium is crucial for alleviating saline-alkali stress, a mechanism corroborated by the findings of Cao[

51] and Anisur Rahman[

48]. Supplementing seedlings with exogenous calcium enhances the selective absorption and stability of calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and potassium (K) by rice roots, while simultaneously reducing sodium (Na) absorption and improving plant salt tolerance[

49]. This study corroborated these findings: under the gypsum application method, rice seedling growth was notably improved. The dry weight and height of seedlings in the JCWH treatment soil surpassed those of seedlings in the farmer's seedling raising soil, ZCK. This can be attributed to the increased dissolution of calcium in the soil due to sulfuric acid, as well as the ability of sulfuric acid to neutralize soil alkalinity and reduce alkaline stress. Notably, in 2022, the root length of seedlings in the JCWH treatment soil was shorter than that in 2021 (

Figure 5b), potentially due to increased soil EC and total alkalinity that year, which inhibited root growth[

52]. This impact may be mitigated by reducing the dosage and frequency of modifier application.

This study demonstrates a significant correlation between the quality of rice seedlings and the parameters of soil salinity and alkalinity, as well as the amount of organic carbon and its components. The findings suggest that short-term improvements to saline-alkali soil can be achieved by applying straw, gypsum, sulfuric acid, and fertilizers. These amendments can reduce salt-alkali stress and enhance nutrient absorption by lowering soil pH and exchangeable sodium, while also increasing the amount of soil organic carbon and its components, ultimately promoting seedling growth (

Figure 6).

5. Conclusions

In this study, the short-term improvement of soil using corn stover, gypsum, sulfuric acid, and fertilizer over two consecutive years significantly reduced both the pH value and exchangeable sodium of the soil, thereby alleviating the ecological barriers associated with soda saline-alkali soils. On the other hand,these short-term improvements led to an increase in soil organic matter, humic acid, and the degree of soil humification, which collectively enhanced soil fertility. Furthermore, the addition of exogenous calcium facilitated the alleviation of growthc stress in plants subjected to salt stress, resulting in a marked improvement in the growth of rice seedlings. Among the various treatments, the JCWH treatment exhibited the most pronounced comprehensive improvement effects. When compared to the soil used for seedling raising by local farmers, the JCWH treatment yielded superior seedling growth parameters. The combination of corn stover, gypsum, and sulfuric acid presents an effective strategy for ameliorating soda saline-alkali soils. This study provides a theoretical foundation and technical support for the development of comprehensive methods aimed at improving alkaline soils.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N.; Methodology, Y.N.and Z.L.; Software, X.L.and L.F.; Validation, Y.N. and Z.L.; Formal analysis,Y.N. and L.J.; Investigation, Y.N. and X.L.; Resources, Z.L.; Data curation, Y.N.and L.J.; Writing—original draft, Y.N.; Writing—review & editing, Y.N. and Z.L.; Visualization, Y.N. and L.F.;Supervision, Y.N. and Z.L.; Project administration, Z.L.; Funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [National Key Research and Development Program of China], grant number [2018YFD0300208].

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

No applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Remediation of soda saline-alkali soil using vermicompost: the remediation mechanisms and enhanced improvement by maize straw. J. Soils Sediments 2025, 25, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.M., et al., Reclamation of saline-sodic soil properties and improvement of rice ( Oriza sativa L .) growth and yield using desulfurized gypsum in the west of Songnen Plain, northeast China. Geoderma 2012, 187, 24–30.

- Jiang, C.-L.; Séquaris, J.-M.; Vereecken, H.; Klumpp, E. Effects of inorganic and organic anions on the stability of illite and quartz soil colloids in Na-, Ca- and mixed Na–Ca systems. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2012, 415, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Lashari, M.S.; Deng, J.; Du, Z. Impact of flue gas desulfurization gypsum and lignite humic acid application on soil organic matter and physical properties of a saline-sodic farmland soil in Eastern China. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, H. and A.R. Astaraei, Effect of Organic and Inorganic Amendments on Parameters of Water Retention Curve, Bulk Density and Aggregate Diameter of a Saline-sodic Soil. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2012, 14, 1625–1636.

- Qadir, M.; Noble, A.; Oster, J.; Schubert, S.; Ghafoor, A. Driving forces for sodium removal during phytoremediation of calcareous sodic and saline-sodic soils: a review. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 21, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, J.E.; Amrhein, C.; Oster, J.D. Comparison of Gypsum and Sulfuric Acid for Sodic Soil Reclamation. Arid. Soil Res. Rehabilitation 1999, 13, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, M., K. Rengabashyam, and V.A. Kumar, Changes in Soil Physico-Chemical Properties and Seedling Growth of Green Gram (Vigna radiata L.) under Sodic Soil as Affected by Soil Amendments: An Incubation Study. Biology and Life Sciences Forum 2023, 27, 28.

- Nie, J.; Zhou, J.-M.; Wang, H.-Y.; Chen, X.-Q.; DU, C.-W. Effect of Long-Term Rice Straw Return on Soil Glomalin, Carbon and Nitrogen. Pedosphere 2007, 17, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Jiao, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, C. The Fate and Challenges of the Main Nutrients in Returned Straw: A Basic Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Li, Y.; Cong, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, W.; Pang, H.; Zhang, L. Depth of straw incorporation significantly alters crop yield, soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in the North China Plain. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Men, X.; Huang, W.; Yi, S.; Wang, W.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z. Effects of Exiguobacterium sp. DYS212, a Saline-Alkaline-Tolerant P-Solubilizing Bacterium, on Suaeda salsa Germination and Growth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawahy, S.A., J.L. Stroehlein, and M. Pessarakli, Dry-matter yield and nitrogen-15, Na+, Cl-, and K+ content of tomatoes under sodium chloride stress 1. Journal of Plant Nutrition 1992, 15, 341–358. [CrossRef]

- Grattan, S.R.; Grieve, C.M. Salinity–mineral nutrient relations in horticultural crops. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 78, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Aslam, Z. Use of environmental friendly fertilizers in saline and saline sodic soils. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 2, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, A.A.; Murtaza, G.; Zia-Ur-Rehman, M.; Waraich, E.A. Application of Gypsum or Sulfuric Acid Improves Physiological Traits and Nutritional Status of Rice in Calcareous Saline-Sodic Soils. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathawat, N.S.; Kuhad, M.S.; Goswami, C.L.; Patel, A.L.; Kumar, R. Interactive Effects of Nitrogen Source and Salinity on Growth Indices and Ion Content of Indian Mustard. J. Plant Nutr. 2007, 30, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Miao, Q.; Shi, H.; Feng, Z.; Feng, W. Effects of Combined Application of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Physical and Chemical Properties in Saline–Alkali Soil. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, D.; Ding, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, S. Straw incorporation and nitrogen fertilization enhance soil carbon sequestration by altering soil aggregate and microbial community composition in saline-alkali soil. Plant Soil 2023, 498, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K., et al., Combined Effects of Straw Return with Nitrogen Fertilizer on Ion Balance, Photosynthetic Characteristics, Leaf Water Status and Rice Yield in Saline-sodic Paddy Fields. 2023.

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, F. Effects of shallow groundwater table and fertilization level on soil physico-chemical properties, enzyme activities, and winter wheat yield. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, S.S.; Seng, L.; Chong, W.N.; Asing, J.; Nor, M.F.B.M.; Pauzan, A.S.B.M. Characterization of the coal derived humic acids from Mukah, Sarawak as soil conditioner. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, M.K. Role of gypsum and compost in reclaiming saline-sodic soils. IOSR J. Agric. Veter- Sci. 2012, 1, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, A.; Murtaza, G.; Rehman, M.Z.; Saifullah; Sabir, M. Reclamation and salt leaching efficiency for tile drained saline-sodic soil using marginal quality water for irrigating rice and wheat crops. Land Degrad. Dev. 2010, 23, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Barak, P.; Jobe, B.O.; Krueger, A.R.; Peterson, L.A.; Laird, D.A. Effects of long-term soil acidification due to nitrogen fertilizer inputs in Wisconsin. Plant Soil 1997, 197, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Qu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, G. Contrasting effects of different straw return modes on net ecosystem carbon budget and carbon footprint in saline-alkali arid farmland. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, Z.; Liang, L.; Yang, B.; Ding, R.; Nie, J.; Wang, J. Maize straw effects on soil aggregation and other properties in arid land. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 153, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Hou, N.; Li, D. Remediation of soda-saline-alkali soil through soil amendments: Microbially mediated carbon and nitrogen cycles and remediation mechanisms. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 924, 171641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Gao, W.; Feng, H. Differences in illite soil macropore morphology caused by Ca2+ and Mg2+ under Na+ presence. CATENA 2024, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y., H.C. Yang, and F.H. Zhang, The effect of Ca2+/Mg2+ on the aggregation process of soil colloids with different alkalization degrees. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2025, 46, 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Feng, H.; Siddique, K.H. Adverse effects of Ca2+ on soil structure in specific cation environments impacting macropore-crack transformation. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-L.; Yu, J.-Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y. [Application of Desulphurized Gypsum with Straw to Improve Physicochemical Properties of Saline-alkali Land in Yellow River Delta]. . 2023, 44, 4119–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hasini, S.; Halima, O.I.; Azzouzi, M.E.; Douaik, A.; Azim, K.; Zouahri, A. Organic and inorganic remediation of soils affected by salinity in the Sebkha of Sed El Mesjoune – Marrakech (Morocco). Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 193, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundha, P., et al., N and P release pattern in saline-sodic soil amended with gypsum and municipal solid waste compost. J Soil Salin Water Qual 2017, 9, 145–155.

- Zhu, C.; Zhong, W.; Han, C.; Deng, H.; Jiang, Y. Driving factors of soil organic carbon sequestration under straw returning across China's uplands. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, M., et al., Effect of Nano-Zinc Oxide, Rice Straw Compost, and Gypsum on Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)Yield and Soil Quality in Saline-Sodic Soil. Nanomaterials, 2024. 14(17).

- Reethu, B.; Kumar, M.S.; Sharath, G.; Ramanjaneyulu, B.; Manchiryal, R.K. Stabilization of clayey soil using Gypsum. J. Stud. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Ma, M.; Peng, N.; Luo, X.; Chen, W.; Cai, P.; Wu, L.; Pan, H.; Chen, J.; Yu, G.; et al. Effects of long-term fertilization on calcium-associated soil organic carbon: Implications for C sequestration in agricultural soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 772, 145037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yuan, Z.-Q.; Fang, C.; Hu, Z.-H.; Li, F.-M.; Sardans, J.; Penuelas, J. The formation of humic acid and micro-aggregates facilitated long-time soil organic carbon sequestration after Medicago sativa L. introduction on abandoned farmlands. Geoderma 2024, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Ai, S.; Meng, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, F.; Cheng, K. Synergistic enhancement of cadmium immobilization and soil fertility through biochar and artificial humic acid-assisted microbial-induced calcium carbonate precipitation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, I.; Delfosse, O.; Mary, B. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization in acidic, limed and calcareous agricultural soils: Apparent and actual effects. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsudays, I.M.; Alshammary, F.H.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Alatawi, A.; Alotaibi, M.M.; Alwutayd, K.M.; Alharbi, M.M.; Alghanem, S.M.S.; Alzuaibr, F.M.; Gharib, H.S.; et al. Applications of humic and fulvic acid under saline soil conditions to improve growth and yield in barley. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Song, X.; Liu, K.; Li, T.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Q.; Li, Z.; et al. Mixture of controlled-release and conventional urea fertilizer application changed soil aggregate stability, humic acid molecular composition, and maize nitrogen uptake. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 789, 147778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C., et al., Dynamic change in amounts soil humic and fulvic acid during corn stalk decomposition. J. Jilin Agric. Univ 2009, 31, 729–732.

- Gao, Y.; Feng, H.; Zhang, M.; Shao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, C. Straw returning combined with controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer affected organic carbon storage and crop yield by changing humic acid composition and aggregate distribution. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. City garbage compost as a source of humus. Biol. Wastes 1988, 26, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Opoku-Kwanowaa, Y. Effects of Returning Granular Corn Straw on Soil Humus Composition and Humic Acid Structure Characteristics in Saline-Alkali Soil. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Calcium Supplementation Improves Na+/K+ Ratio, Antioxidant Defense and Glyoxalase Systems in Salt-Stressed Rice Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.; Pearen, J. Influence of calcium on growth and root penetration of barley seedlings in a saline-sodic soil. Arid. Soil Res. Rehabilitation 1988, 2, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Feng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Guan, F.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, J.; Yu, T.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; et al. Phosphogypsum with Rice Cultivation Driven Saline-Alkali Soil Remediation Alters the Microbial Community Structure. Plants 2024, 13, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, F. Exogenous calcium application mediates K+ and Na+ homeostasis of different salt-tolerant rapeseed varieties under NaHCO3 stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 102, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Abid, M.; Abou-Shanab, R. Amelioration of salt affected soils in rice paddy system by application of organic and inorganic amendments. Plant, Soil Environ. 2013, 59, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).