Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Characteristics

2.2. Greenhouse Experiment

2.3. Soil Sampling

2.4. Laboratory Analyses

2.4.1. Humic Acid and Flue Gas Desulfurization Gypsum Analyses

2.4.2. Soil Analyses

2.4.3. Plant Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

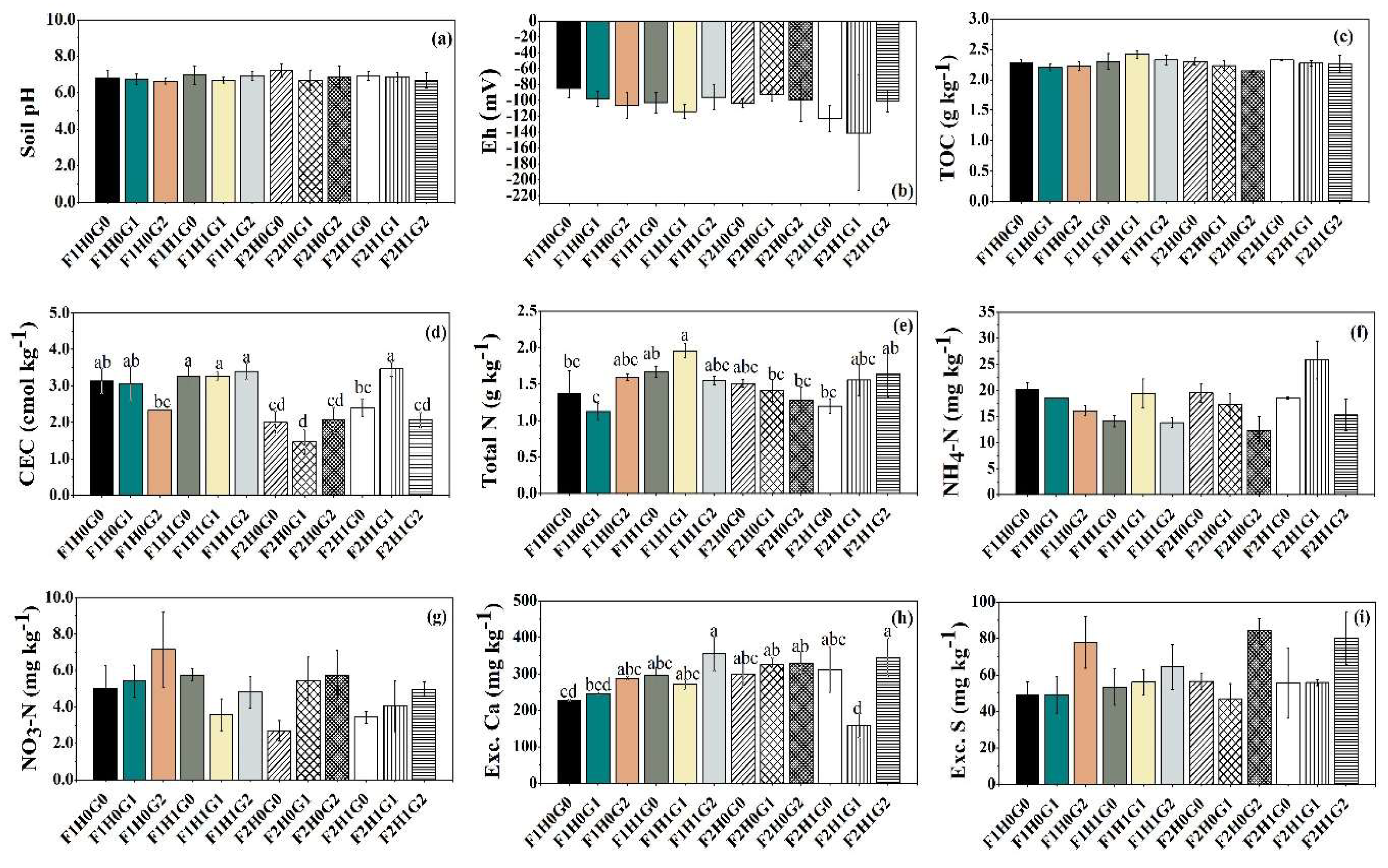

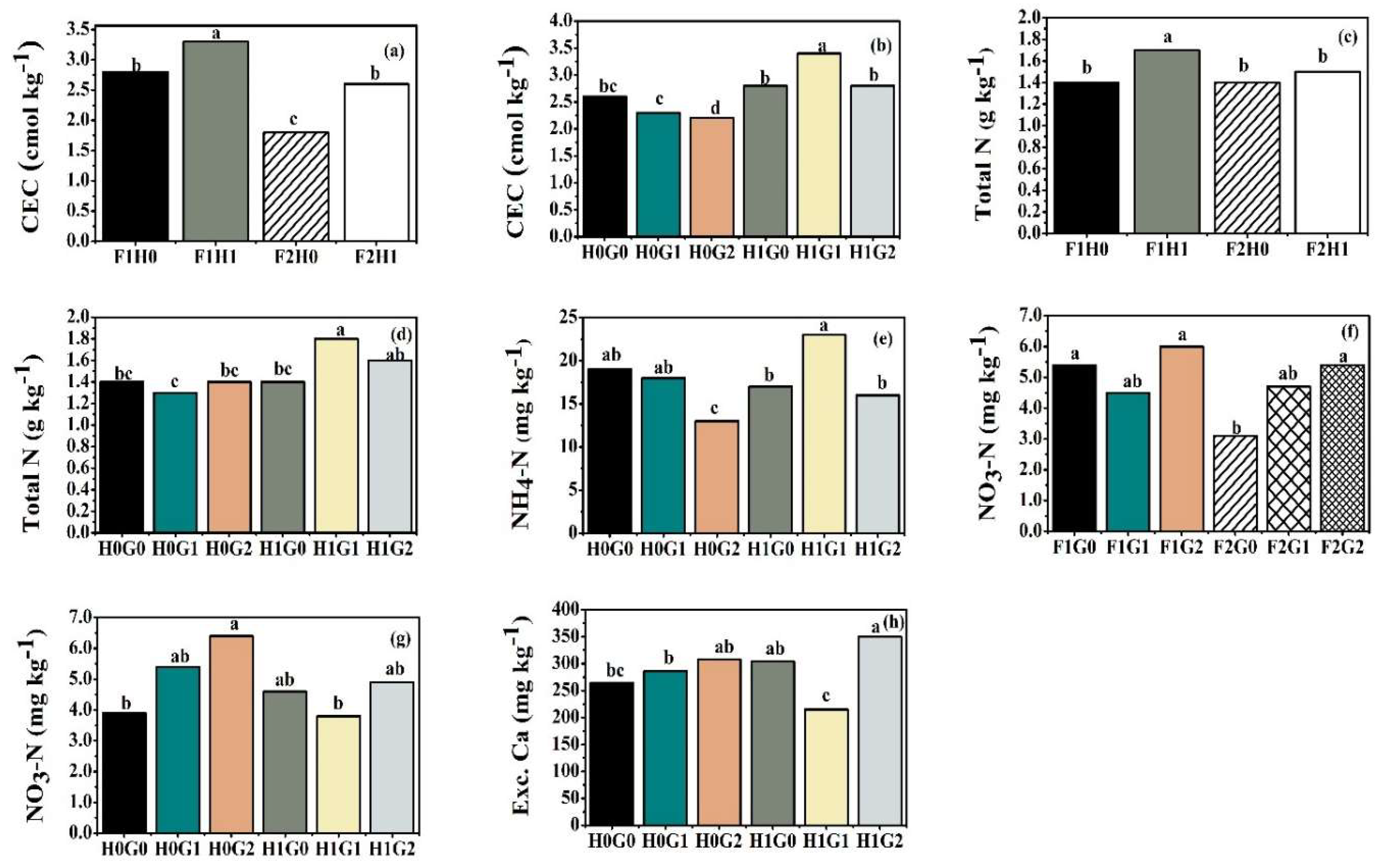

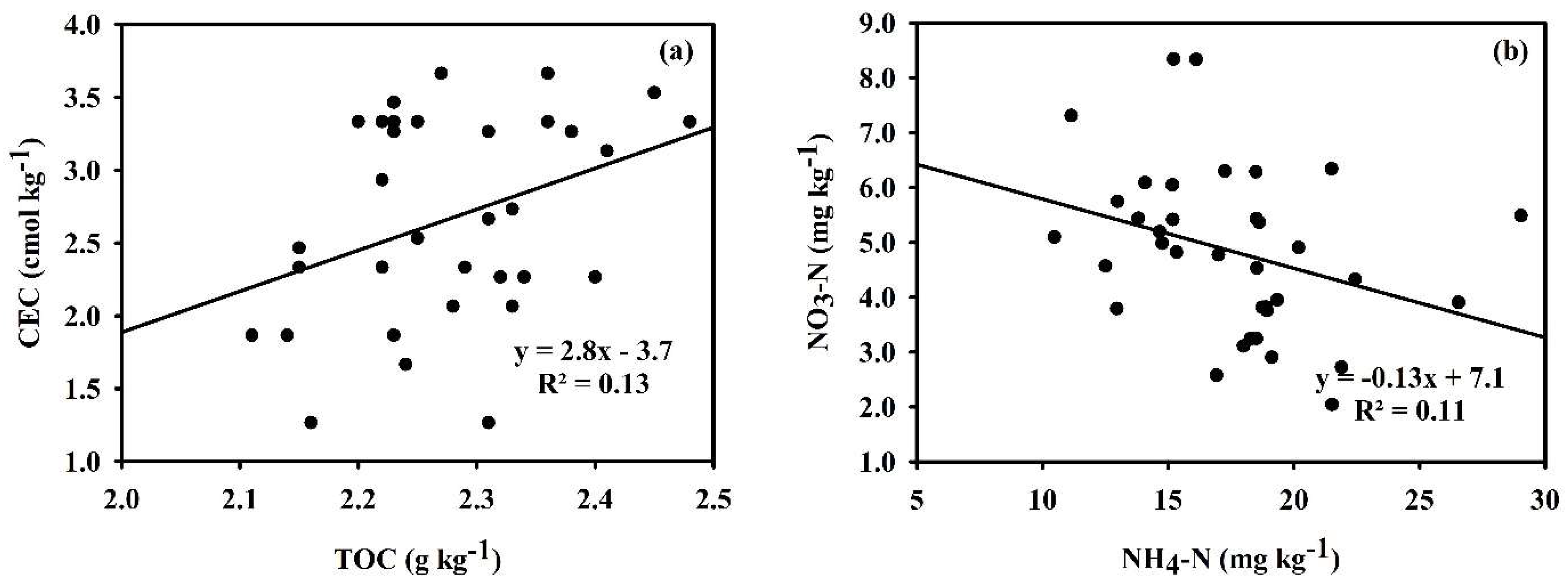

3.1. Effects of Fertilizer, Humic Acid, and Gypsum Applications on Soil Properties

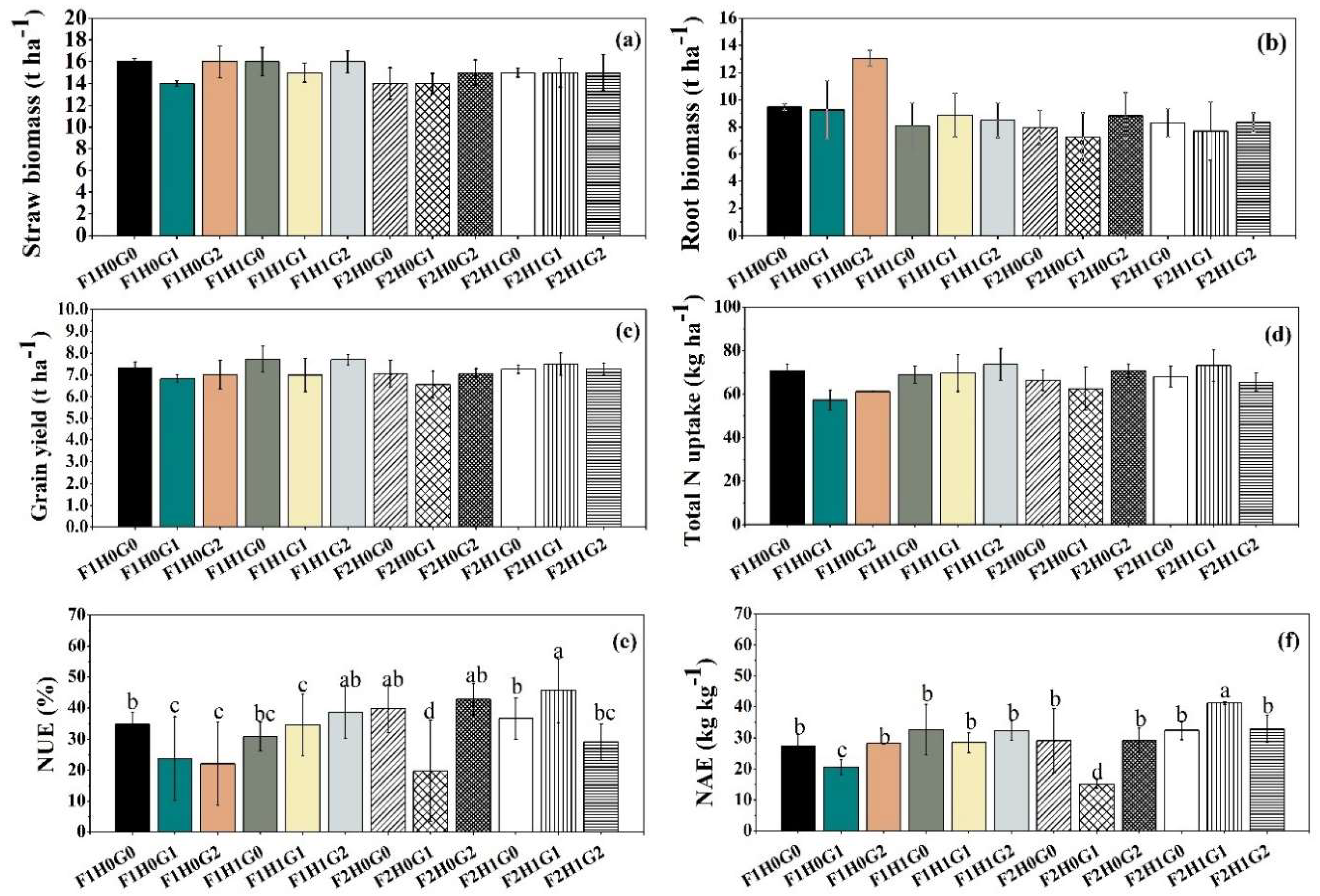

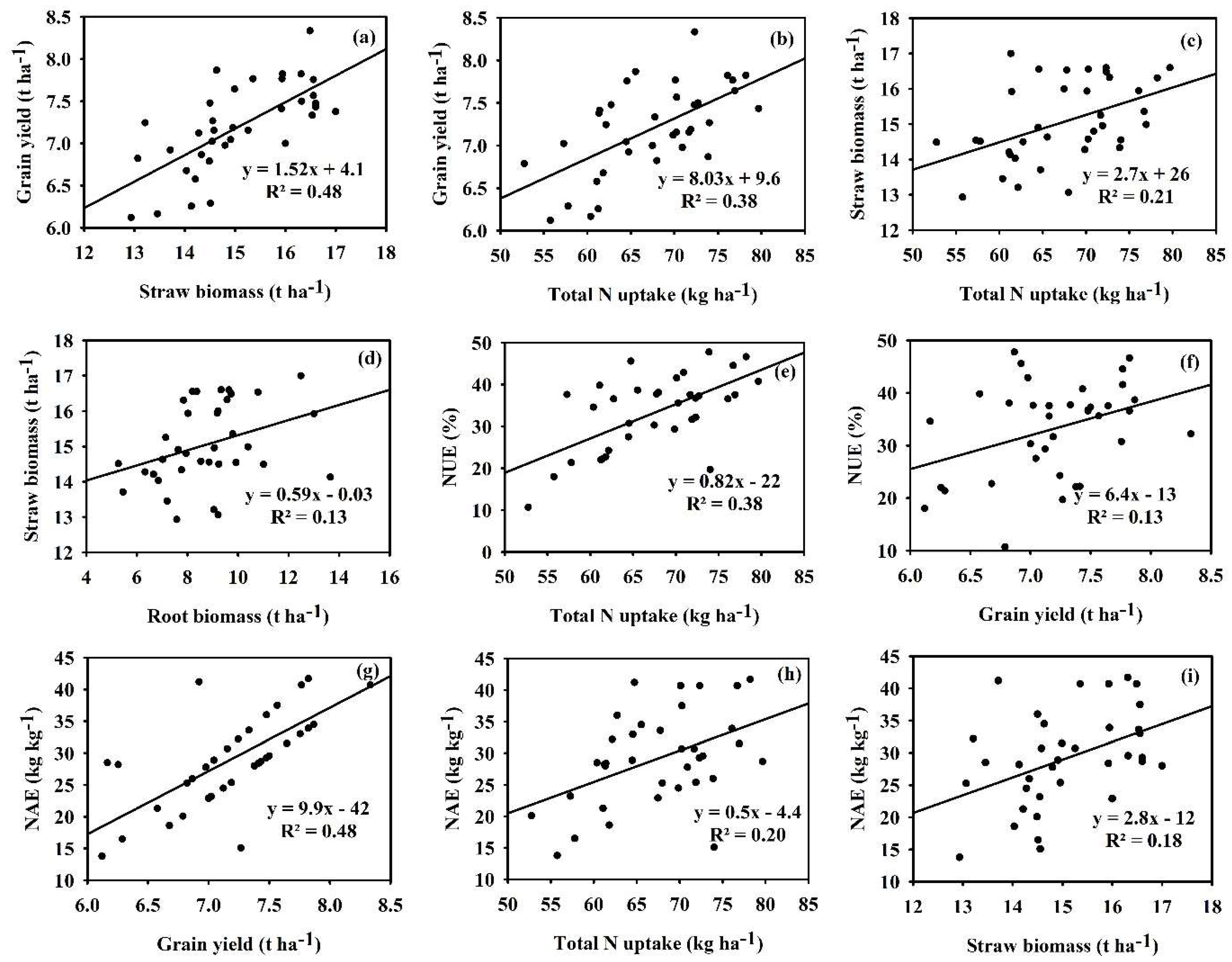

3.2. Yield, Nitrogen Uptake, Nitrogen Use Efficiency, and Nitrogen Agronomic Efficiency of Rice

3.3. Relationship Between Rice Yield, Nitrogen Uptake, Nitrogen Use Efficiency, and Nitrogen Agronomic Efficiency

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, S.; Stuart, A.M.; Laborte, A.G.; Rattalino Edreira, J.I.; Dobermann, A.; Kien, L.V.N.; Thúy, L.T.; Paothong, K.; Traesang, P.; Tint, K.M.; et al. Southeast Asia must narrow down the yield gap to continue to be a major rice bowl. Nat Food 2022, 3, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assessment of farmers’ water and fertilizer practices and perceptions in the North China Plain - Sun - 2022 - Irrigation and Drainage - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ird.2719 (accessed on Mar 19, 2025).

- C. Virochsaengaroon, C. C. Virochsaengaroon, C. Piratanatsakul, P. Lawongsa, T.-S. Sukitprapanon Rice farmers’ perceptions and behaviors on nitrogen fertilizer applications for RD6 glutinous rice cultivation in Northeast Thailand.; Chiangmai, Thailand, 2022; pp. 340–351.

- Xu, Z.; He, P.; Yin, X.; Struik, P.C.; Ding, W.; Liu, K.; Huang, Q. Simultaneously improving yield and nitrogen use efficiency in a double rice cropping system in China. European Journal of Agronomy 2022, 137, 126513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsina, J.; Dutta, S.; Devkota, K.P.; Chakraborty, S.; Neupane, R.K.; Bishta, S.; Amgain, L.P.; Singh, V.K.; Islam, S.; Majumdar, K. Improved nutrient management in cereals using Nutrient Expert and machine learning tools: Productivity, profitability and nutrient use efficiency. Agricultural Systems 2021, 192, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; He, P.; Xu, X.; Qiu, S.; Ullah, S.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, W. Estimating Nutrient Uptake Requirements for Potatoes Based on QUEFTS Analysis in China. Agronomy Journal 2019, 111, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, B.M.; Lawan, B.A.; Jibrin, J.M.; Kamara, A.Y.; Mohammed, I.B.; Rurinda, J.; Zingore, S.; Craufurd, P.; Vanlauwe, B.; Adam, A.M.; et al. Balanced nutrient requirements for maize in the Northern Nigerian Savanna: Parameterization and validation of QUEFTS model. Field Crops Research 2019, 241, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, S.; Yan, L.; Feng, G.; Gao, Q. Agronomic and environmental benefits of nutrient expert on maize and rice in Northeast China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020, 27, 28053–28065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yang, X.; Tang, S.; Han, K.; He, P.; Wu, L. Genotypic Variation in Nutrient Uptake Requirements of Rice Using the QUEFTS Model. Agronomy 2021, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Yang, S.; Huo, L.; He, P.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W. Estimating Nutrient Uptake Requirements for Melon Based on the QUEFTS Model. Agronomy 2022, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabhat-sakorn Sukitprapanon; Patcharee Suriya; Tidarat Monkham; Patimakorn Pasuwan; Patma vityakon Effect of humic acid application on residual phosphorus availability and phosphorus use efficiency of glutinous rice cultivated in paddy soils in Northeast Thailand; Research report, 2020.

- Urmi, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, M.A.; Jahan, N.A.; Mia, M.A.B.; Akhter, S.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Kalaji, H.M. Integrated Nutrient Management for Rice Yield, Soil Fertility, and Carbon Sequestration. Plants 2022, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuku, E.A.; Roobroeck, D.; Vanlauwe, B.; Boeckx, P.; Cornelis, W.M. Maize production under combined Conservation Agriculture and Integrated Soil Fertility Management in the sub-humid and semi-arid regions of Kenya. Field Crops Research 2020, 254, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechaiyaphum, K.; Ullah, H.; Shrestha, R.P.; Datta, A. Impact of long-term agricultural management practices on soil organic carbon and soil fertility of paddy fields in Northeastern Thailand. Geoderma Regional 2020, 22, e00307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adem, M.; Azadi, H.; Spalevic, V.; Pietrzykowski, M.; Scheffran, J. Impact of integrated soil fertility management practices on maize yield in Ethiopia. Soil and Tillage Research 2023, 227, 105595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Linna, C.; Ma, S.; Ma, Q.; Song, W.; Shen, M.; Song, L.; Cui, K.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L. Biochar combined with organic and inorganic fertilizers promoted the rapeseed nutrient uptake and improved the purple soil quality. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 997151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liu, S.; Xie, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, C. Dynamic Changes of Humic Acids in Chicken Manure Composting. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanno, M.; Klavins, M.; Purmalis, O.; Shanskiy, M.; Kisand, A.; Kriipsalu, M. Properties of Humic Substances in Composts Comprised of Different Organic Source Material. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrobas, M.; de Almeida, S.F.; Raimundo, S.; da Silva Domingues, L.; Rodrigues, M.Â. Leonardites Rich in Humic and Fulvic Acids Had Little Effect on Tissue Elemental Composition and Dry Matter Yield in Pot-Grown Olive Cuttings. Soil Systems 2022, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xu, S.; Monreal, C.M.; Mclaughlin, N.B.; Zhao, B.; Liu, J.; Hao, G. Bentonite-humic acid improves soil organic carbon, microbial biomass, enzyme activities and grain quality in a sandy soil cropped to maize (Zea mays L.) in a semi-arid region. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2022, 21, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahoun, A.M.M.A.; El-Enin, M.M.A.; Mancy, A.G.; Sheta, M.H.; Shaaban, A. Integrative Soil Application of Humic Acid and Foliar Plant Growth Stimulants Improves Soil Properties and Wheat Yield and Quality in Nutrient-Poor Sandy Soil of a Semiarid Region. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2022, 22, 2857–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Jiang, W. Effect of Humic Acid Addition on Buffering Capacity and Nutrient Storage Capacity of Soilless Substrates. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Wu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhu, T.; Ming, Y.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Wang, F.; Jiao, S.; Shi, L.; et al. The Application of Humic Acid Urea Improves Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Crop Yield by Reducing the Nitrogen Loss Compared with Urea. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhar Shafi, M.; Adnan, M.; Fahad, S.; Wahid, F.; Khan, A.; Yue, Z.; Danish, S.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Brtnicky, M.; Datta, R. Application of Single Superphosphate with Humic Acid Improves the Growth, Yield and Phosphorus Uptake of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in Calcareous Soil. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chen, X.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Hong, J.; Hu, Y.; Mao, X. Effects and Mechanisms of Phosphate Activation in Paddy Soil by Phosphorus Activators. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Gai, S.; Tang, C.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, K.; Antonietti, M.; Yang, F. Artificial humic acid improves maize growth and soil phosphorus utilization efficiency. Applied Soil Ecology 2022, 179, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.M.; Dick, W.A.; Islam, K.R.; Watts, D.B.; Fausey, N.R.; Flanagan, D.C.; Batte, M.T.; VanToai, T.T.; Reeder, R.C.; Shedekar, V.S. Cover crops, crop rotation, and gypsum, as conservation practices, impact Mehlich-3 extractable plant nutrients and trace metals. International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2024, 12, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartina; Monkham, T.; Vityakon, P.; Sukitprapanon, T.-S. Coapplication of humic acid and gypsum affects soil chemical properties, rice yield, and phosphorus use efficiency in acidic paddy soils. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 4350. [CrossRef]

- Minato, E.A.; Brignoli, F.M.; Neto, M.E.; Besen, M.R.; Cassim, B.M.A.R.; Lima, R.S.; Tormena, C.A.; Inoue, T.T.; Batista, M.A. Lime and gypsum application to low-acidity soils: Changes in soil chemical properties, residual lime content and crop agronomic performance. Soil and Tillage Research 2023, 234, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Corbalá, R.; Slater, B.K.; Dick, W.A.; Bigham, J.; Muñoz-Muñoz, M. Gypsum amendment effects on micromorphology and aggregation in no-till Mollisols and Alfisols from western Ohio, USA. Geoderma Regional 2019, 16, e00217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhu, Z.-L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.-Y.; Liu, Z.-X.; Wu, X.-X.; Ge, S.-F.; Jiang, Y.-M. Role of calcium as a possible regulator of growth and nitrate nitrogen metabolism in apple dwarf rootstock seedlings. Scientia Horticulturae 2021, 276, 109740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangkuan, N.; Chen, X.; Lashari, M.; Jianqiang, D.; Du, Z. Impact of flue gas desulfurization gypsum and lignite humic acid application on soil organic matter and physical properties of a saline-sodic farmland soil in Eastern China. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Lashari, M.S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Du, Z. Effects of applying flue gas desulfurization gypsum and humic acid on soil physicochemical properties and rapeseed yield of a saline-sodic cropland in the eastern coastal area of China. J Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, A.I.; Ahmed, K.; Naseem, A.R.; Qadir, G.; Nawaz, M.Q.; Khalid, M.; Warraich, I.A.; Arif, M. Integrated Use of Humic Acid and Gypsum under Saline-Sodic Conditions. PJAR 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Deng, J.; Rao, X.; Zhang, Y. The combined effects of nitrogen fertilizer, humic acid, and gypsum on yield-scaled greenhouse gas emissions from a coastal saline rice field. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 26, 19502–19511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Hu, G.; Wang, H.; Fu, W. Leaching and migration characteristics of nitrogen during coastal saline soil remediation by combining humic acid with gypsum and bentonite. Annals of Agricultural Sciences 2023, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteorological Department Climate of Thailand; Thai Meteorological Department. Ministry of Information and Communication Technology: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022.

- Soil Survey Staffs Keys to Soil Taxonomy; 13th ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2022.

- Fagundes Costa, R.; Firmano, R.; Bossolani, J.; Alleoni, L. Soil Chemical Properties, Enzyme Activity and Soybean and Corn Yields in a Tropical Soil Under No-till Amended with Lime and Phosphogypsum. International Journal of Plant Production 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, J.P. de Q.; Souza, M. de; Nascimento, C.A.C. do; Rosolem, C.A. Soil acidity amelioration improves N and C cycles in the short term in a system with soybean followed by maize-guinea grass intercropping. Geoderma 2022, 421, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puparn Royal Development Study Center Handbook for Cultivating Sakhon Nakon Rice Variety; Royal Irrigation Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives: Bangkok, Thailand, 2012.

- Sukitprapanon, T.-S.; Jantamenchai, M.; Tulaphitak, D.; Vityakon, P. Nutrient composition of diverse organic residues and their long-term effects on available nutrients in a tropical sandy soil. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, G.E., Lyons, D.J. Soil Chemical Methods - Australasia; Csrio publishing, 2011.

- APHA Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater; American Public Health Association-American Water Works Association, Baltimore, 1998.

- Gee, G.W; Bauder, J.W Particle-size analysis. In: Klute, A. (Ed.), Methods of Soil 759 Analysis: Part 1. Physical and Mineralogical Methods; Second ed.; Agronomy, pp., 1986.

- Tropical soil biology and fertility: a handbook of methods; Anderson, J.M., Ed.; 2. ed., repr.; C.A.B. International: Wallingford, 1996; ISBN 978-0-85198-821-4.

- Ding, C.; Du, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Changes in the pH of paddy soils after flooding and drainage: Modeling and validation. Geoderma 2019, 337, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahrawat, K.L. Fertility and organic matter in submerged rice soils. CURRENT SCIENCE 2005, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Sukitprapanon, T.; Suddhiprakarn, A.; Kheoruenromne, I.; Anusontpornperm, S.; Gilkes, R.J. Forms of Acidity in Potential, Active and Post-Active Acid Sulfate Soils in Thailand. 2015, 48.

- Varadachari, C.; MONDAL, A.; Ghosh, K. Some Aspects of Clay-Humus Complexation: Effect of Exchangeable Cations and Lattice Charge. Soil Science 1991, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, F.J.; Butler, J.H.A. Chemistry of Humic Acids and Related Pigments. In Organic Geochemistry: Methods and Results; Eglinton, G., Murphy, M.T.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1969; pp. 534–557. ISBN 978-3-642-87734-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rampim, L.; Lana, M.C. Ion mobility and base saturation after gypsum application in continuous soybean-wheat cropping system under no-till. Australian Journal of Crop Science 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Febrisiantosa, A.; Ravindran, B.; Choi, H.L. The Effect of Co-Additives (Biochar and FGD Gypsum) on Ammonia Volatilization during the Composting of Livestock Waste. Sustainability 2018, 10, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartina, H.; Monkham, T.; Wisawapipat, W.; Vityakon, P.; Sukitprapanon, T.-S. Influence of Humic Acid and Gypsum on Phosphorus Dynamics and Rice Yield in Acidic Paddy Soil: Insights from Sequential Extraction and Xanes Spectroscopy 2025. [CrossRef]

- Attanayake, C.P.; Dharmakeerthi, R.S.; Kumaragamage, D.; Indraratne, S.P.; Goltz, D. Flooding-induced inorganic phosphorus transformations in two soils, with and without gypsum amendment. Journal of Environmental Quality 2022, 51, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fageria, N.K.; Carvalho, G.D.; Santos, A.B.; Ferreira, E.P.B.; Knupp, A.M. Chemistry of Lowland Rice Soils and Nutrient Availability. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2011, 42, 1913–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaganti, V.N.; Culman, S.W.; Dick, W.A.; Kost, D. Effects of Gypsum Application Rate and Frequency on Corn Response to Nitrogen. Agronomy Journal 2019, 111, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Li, H.; Ren, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L. Calcium Regulates Growth and Nutrient Absorption in Poplar Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossolani, J.W.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; Garcia, A.; Moretti, L.G.; Portugal, J.R.; Rodrigues, V.A.; da Fonseca, M. de C.; Calonego, J.C.; Caires, E.F.; Amado, T.J.C.; et al. Long-Term Lime and Phosphogypsum Amended-Soils Alleviates the Field Drought Effects on Carbon and Antioxidative Metabolism of Maize by Improving Soil Fertility and Root Growth. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 650296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Bin, S.; Iqbal, A.; He, L.; Wei, S.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, P.; Liang, H.; Ali, I.; Xie, D.; et al. High Sink Capacity Improves Rice Grain Yield by Promoting Nitrogen and Dry Matter Accumulation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, C.; Kong, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Canopy light and nitrogen distributions are related to grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Field Crops Research 2017, 206, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghari, S.J.; Wahocho, N.; Laghari, G.; Laghari, A.; Banbhan, G.M.; Talpur, K.; Ahmed, T.; Wahocho, S.; Lashari, A. Role of Nitrogen for Plant Growth and Development: A review. Advances in Environmental Biology 2016, 10, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Zou, P.; Jiang, L. Impact of controlled-release urea on rice yield, nitrogen use efficiency and soil fertility in a single rice cropping system. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Zhang, W.; Gao, J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.; He, D.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S. Improvement of Root Characteristics Due to Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Interactions Increases Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Yield and Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Agronomy 2022, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. The effects of biochar, compost and their mixture and nitrogen fertilizer on yield and nitrogen use efficiency of barley grown on a Nitisol in the highlands of Ethiopia. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 569–570, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanlauwe, B.; Bationo, A.; Chianu, J.; Giller, K.E.; Merckx, R.; Mokwunye, U.; Ohiokpehai, O.; Pypers, P.; Tabo, R.; Shepherd, K.D.; et al. Integrated soil fertility management: Operational definition and consequences for implementation and dissemination. Outlook on Agriculture 2010, 39, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, E.; Qin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, T. Humic Acid Fertilizer Incorporation Increases Rice Radiation Use, Growth, and Yield: A Case Study on the Songnen Plain, China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xiong, Q.; Zhao, B. Combining humic acid with phosphate fertilizer affects humic acid structure and its stimulating efficacy on the growth and nutrient uptake of maize seedlings. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 17502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.C.; Nico, P.S.; Bone, S.E.; Marcus, M.A.; Pegoraro, E.F.; Castanha, C.; Kang, K.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Torn, M.S.; Peña, J. Association between soil organic carbon and calcium in acidic grassland soils from Point Reyes National Seashore, CA. Biogeochemistry 2023, 165, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Initial soil | Humic acid | FG |

| Soil classification | Aeric Kandiaquult | - | - |

| Soil texture | Sandy loam | - | - |

| Sand (g kg-1) | 583 | - | - |

| Silt (g kg-1) | 359 | - | - |

| Clay (g kg-1) | 58 | - | - |

| pH | 4.7 | 9.8 | 7.7 |

| EC (mS cm-1) | 0.08 | 8.3 | 3.3 |

| TOC (g kg-1) | 1.6 | 291 | - |

| CEC (cmol kg-1) | 2.6 | 57 | - |

| NH4-N (mg kg-1) | 23 | - | - |

| NO3-N (mg kg-1) | 12 | - | - |

| Exchangeable Ca (mg kg-1) | 95 | - | - |

| Exchangeable S (mg kg-1) | 37 | - | - |

| Total N (g kg-1) | 0.56 | 11 | 0.12 |

| Total Ca (g kg-1) | 0.28 | 9.4 | 388 |

| Total S (g kg-1) | 0.14 | 6.7 | 199 |

| Treatment | Nitrogen input (kg ha-1) | |||

| Fertilizer | HA | FG | Total | |

| F1H0G0 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| F1H0G1 | 75 | 0 | 0.08 | 75.08 |

| F1H0G2 | 75 | 0 | 0.003 | 75.003 |

| F1H1G0 | 75 | 10.68 | 0 | 85.68 |

| F1H1G1 | 75 | 10.68 | 0.08 | 85.76 |

| F1H1G2 | 75 | 10.68 | 0.003 | 85.683 |

| F2H0G0 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 61 |

| F2H0G1 | 61 | 0 | 0.08 | 61.08 |

| F2H0G2 | 61 | 0 | 0.003 | 61.003 |

| F2H1G0 | 61 | 10.68 | 0 | 71.68 |

| F2H1G1 | 61 | 10.68 | 0.08 | 71.76 |

| F2H1G2 | 61 | 10.68 | 0.003 | 71.683 |

| Soil Properties | Soil pH | Eh | TOC | CEC | Total N | NH4-N | NO3-N | Exc. Ca | Exc. S |

| (mV) | (g kg-1) | (cmol kg-1) | (g kg-1) | (------------------------mg kg-1--------------------) | |||||

| Fertilizer (F) | |||||||||

| F1 | 6.8 | -100 | 2.3 | 3.1a | 1.5a | 16b | 5.2a | 280 | 57 |

| F2 | 6.9 | -110 | 2.3 | 2.2b | 1.4b | 19a | 4.4b | 295 | 63 |

| P value | 0.448 | 0.217 | 0.168 | <0.001 | 0.052 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.173 | 0.167 |

| Humic acid (HA) | |||||||||

| H0 | 6.8 | -97 | 2.2b | 2.3b | 1.4b | 17 | 5.2a | 286 | 60 |

| H1 | 6.8 | -113 | 2.3a | 3.0a | 1.6a | 19 | 4.4b | 290 | 60 |

| P value | 0.913 | 0.064 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.109 | 0.038 | 0.741 | 0.928 |

| Gypsum (FG) | |||||||||

| G0 | 7.0 | -104 | 2.3 | 2.7ab | 1.4 | 18a | 4.2b | 284b | 54b |

| G1 | 6.8 | -111 | 2.3 | 2.8a | 1.5 | 20a | 4.6ab | 250b | 50b |

| G2 | 6.8 | -101 | 2.2 | 2.4b | 1.5 | 15b | 5.7a | 329a | 77a |

| P value | 0.122 | 0.514 | 0.136 | 0.023 | 0.404 | 0.001 | 0.012 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Interactions (P value) | |||||||||

| F × HA | 0.238 | 0.343 | 0.320 | 0.099 | 0.01 | 0.089 | 0.362 | <0.001 | 0.751 |

| F × FG | 0.721 | 0.577 | 0.143 | 0.450 | 0.696 | 0.116 | 0.028 | 0.085 | 0.352 |

| HA × FG | 0.802 | 0.174 | 0.319 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.024 | <0.001 | 0.158 |

| F × HA × FG | 0.313 | 0.697 | 0.379 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.267 | 0.681 | 0.018 | 0.682 |

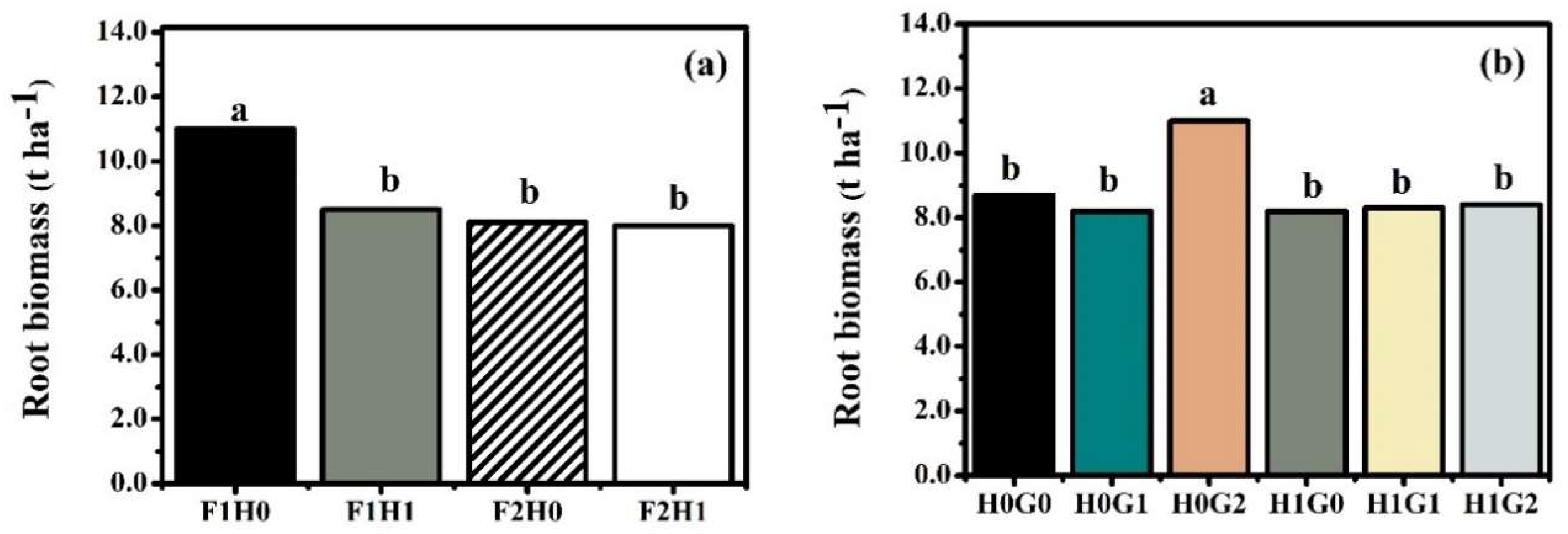

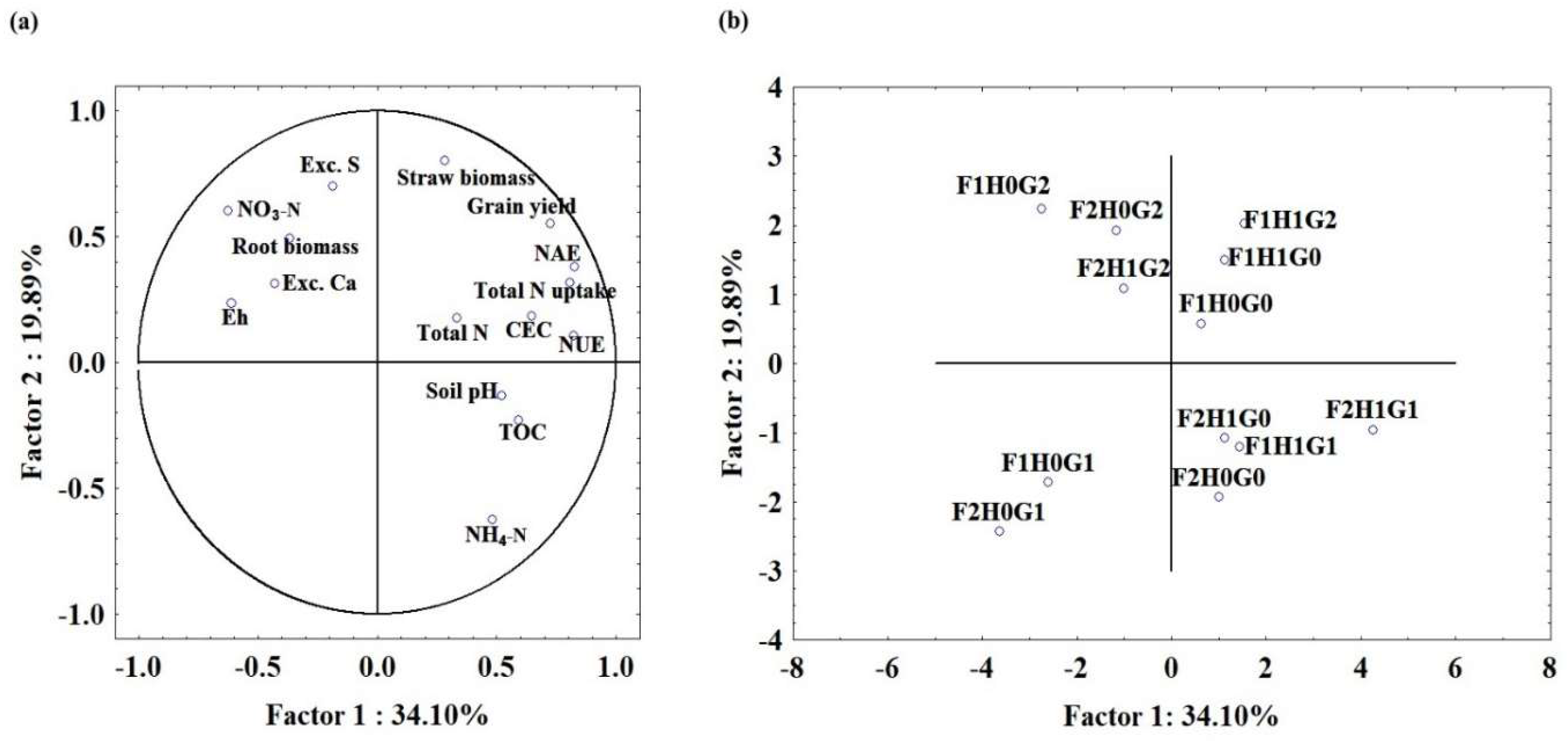

| Treatment | Straw biomass | Root biomass | Grain yield | Total N uptake | NUE | NAE |

| (----------------t ha-1----------------) | (kg ha-1) | (%) | (kg kg-1) | |||

| Fertilizer (F) | ||||||

| F1 | 15 | 9.5a | 7.3 | 68 | 31b | 28 |

| F2 | 15 | 8.1b | 7.1 | 67 | 36a | 30 |

| P value | 0.099 | <0.001 | 0.230 | 0.657 | 0.008 | 0.234 |

| Humic acid (HA) | ||||||

| H0 | 15 | 9.3a | 7.0b | 65b | 30b | 25b |

| H1 | 15 | 8.3b | 7.4a | 70a | 36a | 33a |

| P value | 0.730 | 0.014 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Gypsum (FG) | ||||||

| G0 | 15 | 8.5b | 7.3 | 69 | 36 | 31a |

| G1 | 14 | 8.3b | 6.9 | 66 | 31 | 26b |

| G2 | 15 | 10a | 7.3 | 68 | 33 | 30a |

| P value | 0.120 | 0.011 | 0.094 | 0.429 | 0.101 | 0.034 |

| Interactions (P value) | ||||||

| F x HA | 0.499 | 0.008 | 0.903 | 0.177 | 0.161 | 0.073 |

| F x FG | 0.243 | 0.257 | 0.368 | 0.334 | 0.853 | 0.631 |

| HA × FG | 0.662 | 0.027 | 0.768 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| F × HA × FG | 0.709 | 0.218 | 0.184 | 0.073 | <0.001 | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).