Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Photosynthetic Efficiency in Peas

3.2. Yield and Photosynthetic Efficiency in Faba Bean

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| E | transpiration intensity |

| PN | photosynthesis intensity |

| Fv/Fm | maximum quantum efficiency of PSII |

| PI | PSII Performance Index |

| SY | seed yield |

| NP | number of pods per plant |

| NS | number of seeds per plant |

| WS | weight of seeds per plant |

| TSW | thousand seed weight |

References

- Adireddy, R. G.; Manna, S.; Patanjali, N.; Singh, A.; Dass, A.; Mahanta, D.; Singh, V. K. Unveiling Superabsorbent Hydrogels Efficacy Through Modified Agronomic Practices in Soybean–Wheat System Under Semi--Arid Regions of South Asia. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2024, 210(4), e12730. [CrossRef]

- adeem, M.; Li, J.; Yahya, M.; Sher, A.; Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Qiu, L. Research progress and perspective on drought stress in legumes: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20(10), 2541. [CrossRef]

- Tawaha, A. R. M.; Alatrash, H.; Jabbour, Y.; Al-Tawaha, A. R.; Qaisi, A. M.; Jammal, R.; Karnwal, A.; Shatnawi, M.; Saranraj, P.; Rammal, J. Drought stress and sustainable legume production. In Marker-Assisted Breeding in Legumes for Drought Tolerance; Springer, 2025; pp. 23–40. [CrossRef]

- Roman, G. V.; Epure, L. I.; Toader, M.; Lombardi, A. R. Grain legumes-main source of vegetal proteins for European consumption. Agrolife Sci. J. 2016, 5(1).

- Florek J., Czerwińska-Kayzer D., Jerzak M. Current state of production and use of leguminous crops. Fragm. Agron. 2012, 29(4), 45-55. (In Polish).

- Bhattacharya, A. Effect of soil water deficit on growth and development of plants: a review. In Soil water deficit and physiological issues in plants; Springer Singapore, 2021; pp. 393-488. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, B.; Ji, J. Effects of drought stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence images of soybean (Glycine max L.) seedlings. Int. J. Agric. & Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniak, M;, Bojarszczuk, J.; Księżak, J. Changes in yield and gas exchange parameters in Festulolium and alfalfa grown in pure sowing and in mixture under drought stress. Acta Agric. Scand. 2018, 68(3), 255-263. [CrossRef]

- Starck, Z.; Chołuj, D.; Niemyska, B. Physiological responses of plants to unfavorable environmental factors: Publisher SGGW, Warsaw, 1995; pp. 27–47. (In Polish).

- Olszewska, M. Reaction of selected meadow fescue and Timothy cultivars to water stress. Acta Sci. Pol., Agric. 2003, 2(2), 141–148.

- Kalaji, H.M.; Jajoo, A.; Oukarroum, A.; Brestic, M.; Zivcak, M.; Samborska, I.A.; Cetner, M.D.; Łukasik, I.; Goltsev, V.; Ladle, R.J. Chlorophyll a fluorescence as a tool to monitor physiological status of plants under abiotic stress conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Wi, S.; Chung, H.; Lee, H. Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging for environmental stress diagnosis in crops. Sensors 2024, 24(5), 1442.

- Šesták, Z.; Šiffel, P. Leaf-age related differences in chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynthetica 1997, 33, 3/4, 347–369. [Google Scholar]

- Linn, A. I.; Zeller, A. K.; Pfündel, E. E.; Gerhards, R. Features and applications of a field imaging chlorophyll fluorometer to measure stress in agricultural plants. Precision Agric. 2021, 22(3), 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkari, A. Effect of superabsorbent polymer on photosynthetic traits, chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence indices of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under drought stress. J. Plant Environ. Physiol. 2022, 17(66), 57–73. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, S.; Riad, G.; Abu El-Azm, N.A.I.; Ahmed, E. Amending sandy soil with biochar or/and superabsorbent polymer mitigates the adverse effects of drought stress on green pea. Egypt. J. Hort. 2018, 45, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowera, B. Changes in hydrothermal conditions in Poland (1971–2010). Fragm. Agron. 2014, 31, 74–87. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bleiholder, H.; Buhr, L.; Feller, C.; Hack, H.; Hess, M.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Stauss, R.; van den Boom, T.; Weber, E.; Lancashire, P.D.; Munger, P. Compendium of growth stage identification keys for mono- and dicotyledonous plants. BASF 2011, 31–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Jiao, X.; Xu, J. Responses of rice yield, irrigation water requirement and water use efficiency to climate change in China: historical simulation and future projections. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 146, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S.; Qiao, Y.; Baodi, D.; Shi, C.; Liu, M. Effect of water stress on leaf level gas exchange capacity and water-use efficiency of wheat cultivars. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 21, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labidi, N.; Mahmoudi, H.; Dorsaf, M.; Slama, I.; Abdelly, C. Assessment of intervarietal differences in drought tolerance in chickpea using both nodule and plant traits as indicators. J. Plant Breed. Crop Sci. 2009, 1, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rahbarian, R.; Khavari-Nejad, R.; Ganjeali, A.; Bagheri, A.; Najafi, F. Drought stress effects on photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and water relations in tolerant and susceptible chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes. Acta Biol. Cracov. Bot. 2011, 53, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, C.; Çağirgan, M.İ. Assessment of response to drought stress of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) lines under rainfed conditions. Turk. J. Agric. For. 1998, 22, 615–622. [Google Scholar]

- Magyar-Tábori, K.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N.; Dobránszki, J. Models and tools for studying drought stress responses in peas. OMICS 2011, 15, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parameshwarappa, S.G.; Salimath, P.M. Field screening of chickpea genotypes for drought resistance. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 21, 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mandić, V.; Krnjaja, V.; Tomić, Z.; Bijelić, Z.; Simić, A.; Đorđević, S.; Stanojković, A.; Gogić, M. Effect of water stress on soybean production. Proc. 4th Int. Congr. New Perspect. Chall. Sustain. Livest. Prod. Belgrade 2015, pp. 405–414.

- Shankarappa, S.K.; Muniyandi, S.J.; Chandrasheka, A.B.; Singh, A.K.; Nagabhushanaradhya, P.; Shivashankar, B.; El-Ansary, D.O.; Wani, S.H.; Elansary, H.O. Standardizing the hydrogel application rates and foliar nutrition for enhancing yield of lentil (Lens culinaris). Processes 2020, 8, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaeil, P.; Habibi, D.; Boojar, M.M.A. Yield and yield component quality of red bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars in response to water stress and super absorbent polymer application. Ann. Biol. Res. 2012, 3, 5701–5704. [Google Scholar]

- Księżak, J. Evaluation of faba bean productivity depending on hydrogel rate and humidity soil level. Fragm. Agron. 2018, 35, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Q.; Geetha, K.N.; Hashimi, R.; Atif, R.; Habimana, S. Growth and yield of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] as influenced by organic manures and superabsorbent polymers. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2020, 42, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, F.; Allahdadi, I.; Akbari, G.A. Impact of superabsorbent polymer on yield and growth analysis of soybean (Glycine max L.) under drought stress condition. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 4190–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasiewicz, K.; Faligowska, A.; Szymańska, G.; Szukała, J.; Koziara, W.; Ratajczak, K. The effects of using hydrogel in pea cultivation (Pisum sativum L.). Biul. Inst. Hod. Aklim. Rośl. 2019, 285, 235–236. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Faligowska, A.; Szukała, J. Influence of irrigation, soil tillage systems and polymer on yielding and sowing value of pea. Fragm. Agron. 2011, 28, 15–22. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Faligowska, A.; Szukała, J. Influence of organic polymer on yield components and seed yield of soybean. Nauka Przyr. Technol. 2014, 8, 9. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Arve, L.; Torre, S.; Olsen, J.; Tanino, K. Stomatal responses to drought stress and air humidity. In: Abiotic Stress in Plants – Mechanisms and Adaptations. IntechOpen, Rijeka 2011, pp. 267–280. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. , Nawata E., Hosokawa M., Domae Y., Sakuratani T. Alterations in photosynthesis and some antioxidant enzymatic activities of mungbean subjected to waterlogging. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeEll, J.R.; Van Kooten, O.; Prange, R.K.; Murr, D.P. Applications of chlorophyll fluorescence techniques in postharvest physiology. Hortic. Rev. 1999, 23, 69–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.F.; Ribeiro Júnior, W.Q.; Ramos, M.L.G.; Soares, G.F.; de Lima Guimarães, C.A.; da Silva Neto, S.P.; Williams, T.C.R. The impact of polymer on the productivity and photosynthesis of soybean under different water levels. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ahmad, R.; Safdar, M. Effect of hydrogel on the performance of aerobic rice sown under different techniques. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 57, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M.A. Plant drought stress: effects, mechanisms and management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, O.H. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool in cereal crop research. Photosynthetica 2003, 41, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M.; El-Tohamy, W.A.; El-Abagy, H.M.H.; Aggor, F.S.; Nada, S.S. Response of snap bean plants to super absorbent hydrogel treatments under drought stress conditions. Curr. Sci. Int. 2015, 4, 467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, M.M.; Alharbi, B.M.; Alzahrani, Y.M.; Alghamdi, A.G.; Alzahrani, M.M. Influence of super-absorbent polymer on growth and productivity of green bean under drought conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

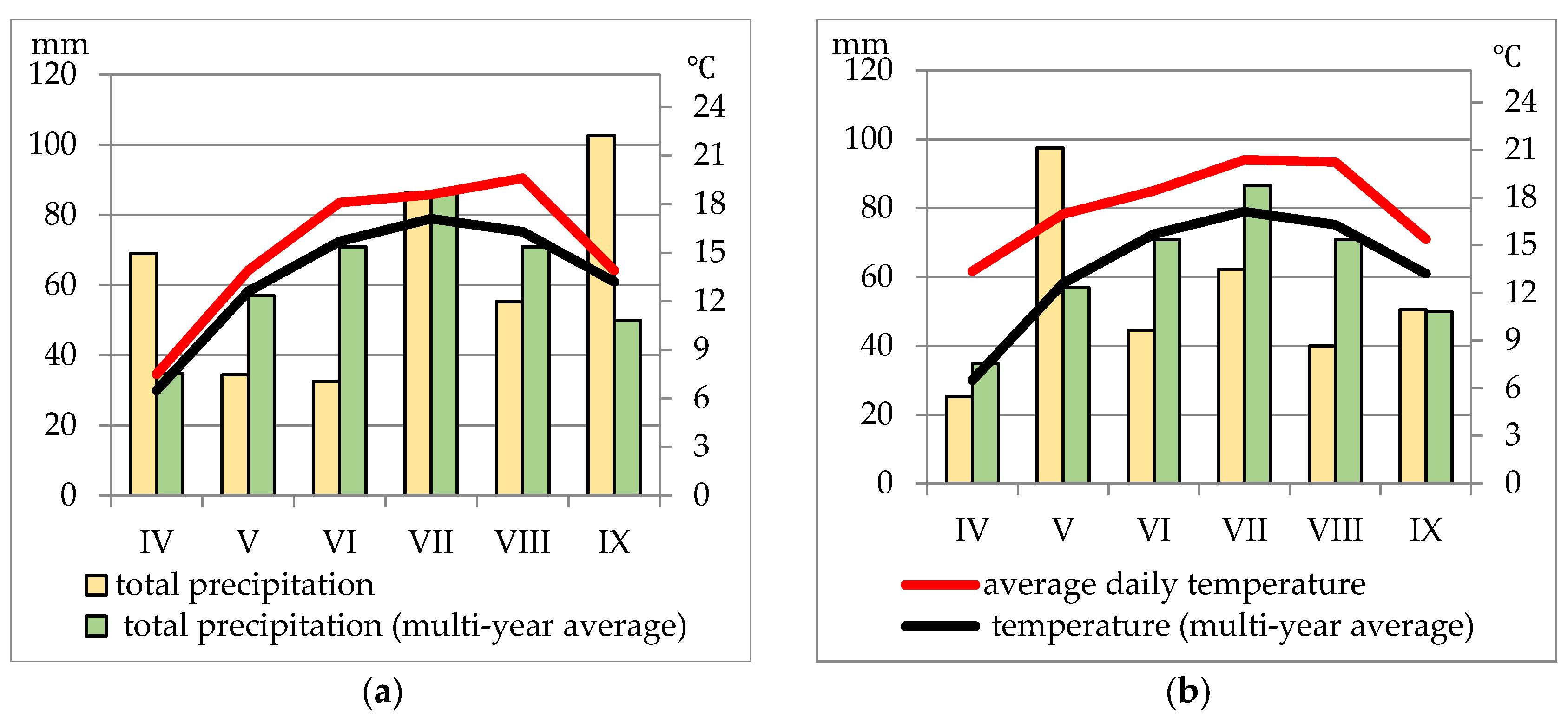

| Month | Years of study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | 2017 | k | 2018 | |

| April | 3.11 | extremely wet | 0.63 | very dry |

| May | 0.8 | dry | 1.85 | moderately wet |

| June | 0.6 | very dry | 0.81 | dry |

| July | 1.5 | optimal | 0.99 | dry |

| August | 0.91 | dry | 0.64 | very dry |

| September | 2.45 | wet | 1.09 | fairly dry |

| Factor | Source of variation | Number of pods per plant | Number of seeds per plant | Weight of seeds per plant (g) | Seed yield (t ha-1) | TSW(g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose of SAP (D) | SAP0 | 5.16 ab | 21.6 ab | 4.59 a | 2.02 a | 207.6 a |

| SAP20 | 4.81 a | 18.9 a | 4.10 a | 2.37 b | 208.7 a | |

| SAP30 | 5.69 b | 23.8 b | 5.09 a | 2.42 b | 209.2 a | |

| p-value | * | * | ns | *** | ns | |

| Year (Y) | 2017 | 4.04 a | 17.0 a | 3.09 a | 1.91 a | 181.1 a |

| 2018 | 6.40 b | 25.8 b | 6.09 b | 2.63 b | 235.9 b | |

| p-value | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| D x Y | p-value | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

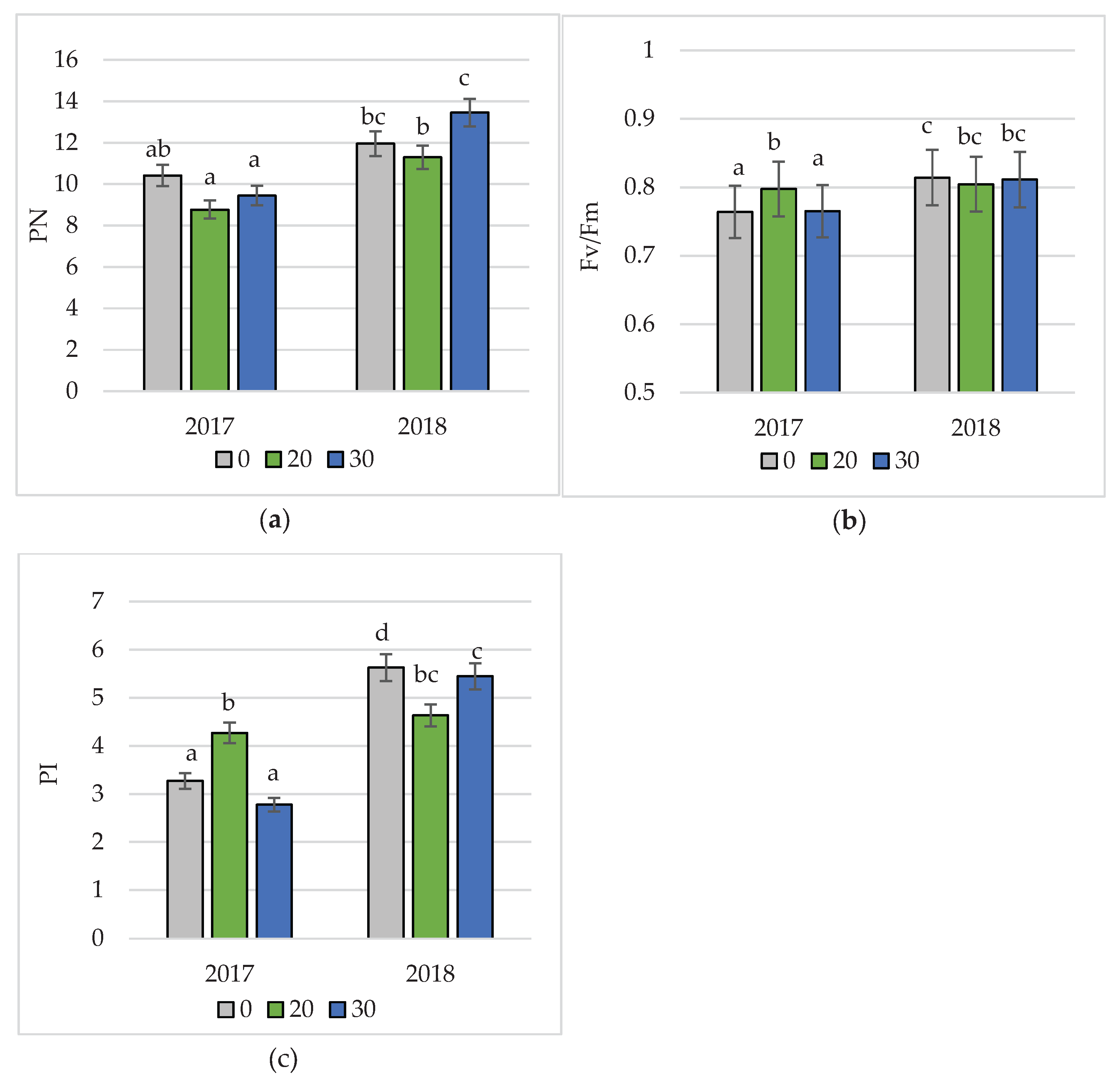

| Factor | Source of variation | E | PN | WUE | Fv/Fm | PI | SPAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose of SAP (D) | SAP0 | 1.36 a | 11.19 b | 9.09 a | 0.789 a | 4.45 a | 575.2 a |

| SAP20 | 1.20 a | 10.03 a | 9.08 a | 0.801 b | 4.45 a | 570.1 a | |

| SAP30 | 1.27 a | 11.45 b | 9.61 a | 0.788 a | 4.11 a | 589.7 a | |

| p-value | ns | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | |

| Year (Y) | 2017 | 1.54 b | 9.54 a | 6.23 a | 0.776 a | 3.44 a | 582.9 a |

| 2018 | 1.01 a | 12.23 b | 12.29 b | 0.810 b | 5.24 b | 573.8 a | |

| p-value | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | |

| D x Y | p-value | ns | * | ns | *** | *** | * |

| E | WUE | Fv/Fm | PI | SY | NP | NS | WS | TSW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | -0.5904 ** |

0.8389 *** |

0.465 * |

0.5588 ** |

0.5367 ** |

0.135 ns |

-0.052 ns |

0.3042 ns |

0.282 ns |

| E | -0.9125 *** |

-0.7509 *** |

-0.6626 *** |

-0.7833 *** |

-0.5084 * |

0.0435 ns |

-0.434 * |

-0.4552 * |

|

| WUE | 0.6709 *** |

0.649 *** |

0.7116 *** |

0.413 * |

-0.0199 ns |

0.4229 * |

0.3958 ns |

||

| Fv/Fm | 0.8743 *** |

0.7353 *** |

0.4346 * |

-0.0158 ns |

0.4379 * |

0.4956 * |

|||

| PI | 0.5825 ** |

0.3198 ns |

0.0257 ns |

0.4988 * |

0.5044 * |

||||

| SY | 0.4951 * |

0.0436 ns |

0.4505 * |

0.3858 ns |

|||||

| NP | 0.5612 ** |

0.8413 *** |

0.402 ns |

| Factor | Source of variation | Number of pods per plant | Number of seeds per plant | Weight of seeds per plant (g) | Seed yield (t ha-1) | TSW(g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose of SAP (D) | SAP0 | 4.11 a | 11.36 a | 4.83 a | 1.74 a | 420.1 a |

| SAP20 | 3.66 a | 9.26 a | 3.95 a | 2.15 b | 428.5 a | |

| SAP30 | 3.55 a | 9.25 a | 4.09 a | 2.27 b | 440.8 a | |

| p-value | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | |

| Year (Y) | 2017 | 3.87 a | 10.13 a | 4.38 a | 1.58 a | 432.8 a |

| 2018 | 3.68 a | 9.78 a | 4.20 a | 2.53 b | 426.8 a | |

| p-value | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | |

| D x Y | p-value | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Factor | Source of variation | E | PN | WUE | Fv/Fm | PI | SPAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose of SAP (D) | SAP0 | 1.19 a | 9.97 a | 8.40 a | 0.79 a | 3.63 a | 579.9 a |

| SAP20 | 1.26 a | 11.77 b | 9.48 a | 0.80 b | 4.16 b | 580.4 a | |

| SAP30 | 1.13 a | 9.97 a | 8.90 a | 0.79 a | 3.53 a | 579.1 a | |

| p-value | ns | *** | ns | * | ** | ns | |

| Year (Y) | 2017 | 1.29 b | 10.99 b | 8.61 a | 0.81 b | 4.60 b | 569.7 a |

| 2018 | 1.10 a | 10.15 a | 9.24 a | 0.78 a | 2.94 a | 589.9 b | |

| p-value | ** | ** | ns | *** | *** | ** | |

| D x Y | p-value | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| E | WUE | Fv/Fm | PI | SPAD | SY | NS | WS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | 0.6051 ** |

0.3483 ns |

0.2584 ns |

0.3437 ns |

-0.1972 ns |

-0.247 ns |

-0.1371 ns |

-0.1794 ns |

| E | -0.5285 ** |

0.5423 ** |

0.5745 ** |

-0.6838 *** |

-0.5724 ** |

0.0227 ns |

-0 .0174 ns |

|

| WUE | -0.3567 ns |

-0.311 ns |

0.6014 ** |

0.433 * |

-0.2214 ns |

-0.2129 ns |

||

| Fv/Fm | 0.8371 *** |

-0.6362 *** |

-0.7164 *** |

-0.037 ns |

-0.1171 ns |

|||

| PI | -0.6134 ** |

-0.7451 *** |

0.0824 ns |

0.0918 ns |

||||

| SPAD | 0.5436 ** |

-0.0246 ns |

-0.0917 ns |

|||||

| SY | -0.2752 ns |

-0.1804 ns |

||||||

| NP | 0.9022 *** |

0.7733 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).