1. Introduction

Climate change across the globe is causing damage due to the reduction in productivity of various crops, reflecting negative ecological, economic and social impacts [

1]. Water scarcity is one of the consequences of these changes, characterized as a primary abiotic stress, thus constituting one of the main challenges to be faced by society in the 21st century, given that its negative impacts will reflect on various human activities on the planet [

2], with agriculture being the most affected, as it compromises above all the food security and nutrition of the population [

3].

In this sense, as a strategy for adapting to adverse conditions, a better understanding of plant plasticity will increase the possibility of selecting plants that are resilient to the predicted climate fluctuations [

4]. Thus, there is a need to cultivate species with a diversity of improved genotypes for adaptation to growing environments, for example, cowpea [

Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.], with attributes of interest to farmers [

5,

6].

The cowpea is a species characterized by its high productive potential, possessing essential nutrients for health, such as: proteins, amino acids, carbohydrates, minerals, fibers and vitamins, as well as containing bioactive compounds with anti-inflammatory, immunostimulant, neuroprotective, anticancer, antioxidant and cardioprotective properties [

7,

8]. In addition, its low cultivation cost and moderate tolerance to water deficit make this crop widely used by small, medium and large farmers [

9].

However, even though it has moderate tolerance to several factors, drought is one of the most limiting to its productivity [

10,

11]. It is therefore necessary to implement technologies to make cowpea production viable even under adverse conditions, in order to provide farmers with food security and a source of income.

Among the various technologies, seed priming stands out for inducing tolerance to deleterious biotic and abiotic effects, through the stress memory imposed during the seed conditioning process, which causes physiological and metabolic improvements in the seeds [

12]. Research indicates that the seed priming technique has shown excellent results in cowpeas [

13,

14].

In addition to the information mentioned above, it is worth noting that various inducing agents can be used in seed priming, particularly silicon [

15], spectral light radiation [

16] and polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000) [

17]. It should also be noted that little is known about the combination of these factors in conditioning cowpea seeds, and more studies are needed to elucidate the effectiveness of this treatment.

Given the above information, the aim of this study was to induce tolerance to water deficit in cowpeas by priming seeds with polyethylene glycol 6000 and silicic acid.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Conduct of the Experiment

The experiment was conducted in two stages, with Stage I (application of seed conditioning) being carried out at the Cultivated Plant Ecophysiology Laboratory - ECOLAB/UEPB, located in the state of Paraíba. Stage II of the experiment (plant development in a phytotron growth chamber) was carried out at the Experimental Station located at 07° 12' 42, 99'' South latitude, 35° 54' 36, 27'' West longitude and an altitude of 521 m, belonging to the State University of Paraíba - UEPB.

2.2. Application of Seed Priming (Stage I)

The BRS Pingo de Ouro seeds made available by the Cultivated Plant Ecophysiology Laboratory - ECOLAB/UEPB were used. Initially, the seeds were sorted, discarding those containing physical, biological and/or malformation damage. After sorting, the seeds were sterilized in a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution (NaClO) for 3 min followed by washing with distilled water for 1 min, after which the seeds were briefly dried for priming [

18].

Immediately after this process, 50 seeds were placed in plastic Gerbox® boxes measuring 11 × 11 × 3.5 cm in length, width and height, in the appropriate order. The substrate inside the boxes consisted of two layers of 'germitex' paper (non-toxic, neutral pH, grammage of 65 g m

-2), autoclaved and moistened with the appropriate solutions for each conditioning, in a volume corresponding to approximately 2.5 times their dry mass [

16].

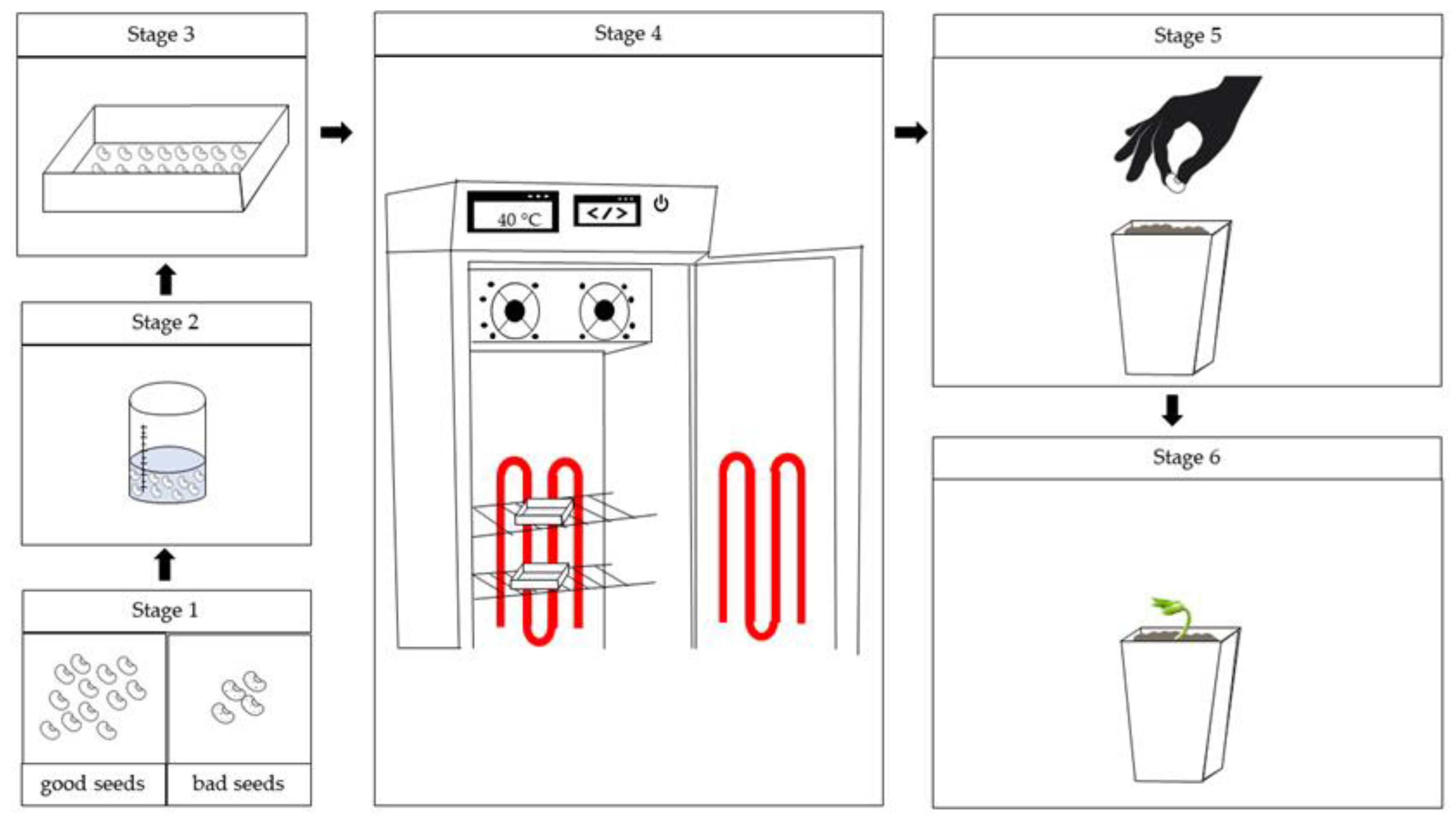

The boxes containing the seeds were placed in B.O.D. germination chambers adapted with LED strips to provide the light condition. The conditioning time was 5 hours. Afterwards, the seeds were transferred to Gerbox® boxes with two layers of dry germite paper and dried under the same light and temperature conditions used during conditioning (

Figure 1).

Seed priming (SP) was made up of combinations of three water potentials induced by polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG 6000): no water deficit (Ψw 0 MPa), moderate (Ψw -0.4 MPa) and high (Ψw -0.8 MPa) and two concentrations of silicic acid (commercial product with 42% silicon) (0 and 200 mg L

-1). The application of SP was carried out in bright conditions with red light with a wavelength of 600 to 680 nm (RL) for the activation of phytochrome responses [

16], at a constant temperature of 40ºC (

Table 1).

2.3. Growing in a Fitotron-Type Growth Chamber (Stage II)

The seeds obtained from the conditioning in Stage I were sown in polyethylene pots with a capacity of 0.8 L, filled with 1 kg of substrate, in the proportion of 75% soil homogenized with 25% cattle manure. After sowing, the pots were transferred to a Fitotron-type growth chamber (

Figure 1), with the temperature set at 32 °C during the day and 28 °C at night, and the relative humidity kept constant at 60%, with a 12-hour photoperiod.

Water replacement levels were managed normally, using 100% of ETc (crop evapotranspiration), until 20 days after sowing. Water stress began at 21 DAS, when the irrigation rates were differentiated. Irrigation was daily, using the method of weighing the pots [

19]. The water used was public supply water from CAGEPA (Companhia de Água e Esgotos da Paraíba).

2.4. Variables Analyzed

The Materials and Methods should be described with sufficient details to allow others to replicate and build on the published results. Please note that the publication of your manuscript implicates that you must make all materials, data, computer code, and protocols associated with the publication available to readers. Please disclose at the submission stage any restrictions on the availability of materials or information. New methods and protocols should be described in detail while well-established methods can be briefly described and appropriately cited.

2.5. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

The experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design (DIC), in a 6 x 2 factorial scheme. The factors consisted of six seed conditionings: control (40 °C + Ψw 0 MPa + 0 mg L-1 of Si + RL), seed priming 2 (40 °C + Ψw 0 MPa + 200 mg L-1 of Si + RL), Seed priming 3 (40 °C + Ψw -0.4 MPa + 0 mg L-1 of Si + RL), Seed priming 4 (40 °C + Ψw -0.4 MPa + 200 mg L-1 Si + RL), Seed priming 5 (40 °C + Ψw -0.8 MPa + 0 mg L-1 Si + RL) and Seed priming 6 (40 °C + Ψw -0.8 MPa + 200 mg L-1 Si + RL) and two levels of crop evapotranspiration water replacement (100 and 50% of ETc), with four replications. The combination of these two factors resulted in 12 treatments, making up 48 experimental units.

The data obtained was subjected to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test [

20], and when the assumptions of normality were met, analysis of variance was carried out (F test up to 5% probability). The t-test (LSD) was used to compare the means of reference evapotranspiration in order to assess the performance of the treatments when water restriction was imposed. And Tukey's test to analyze the difference between the different seed priming combinations. The statistical software Sisvar 5.6 [

21] was used to carry out the analyses.

3. Results

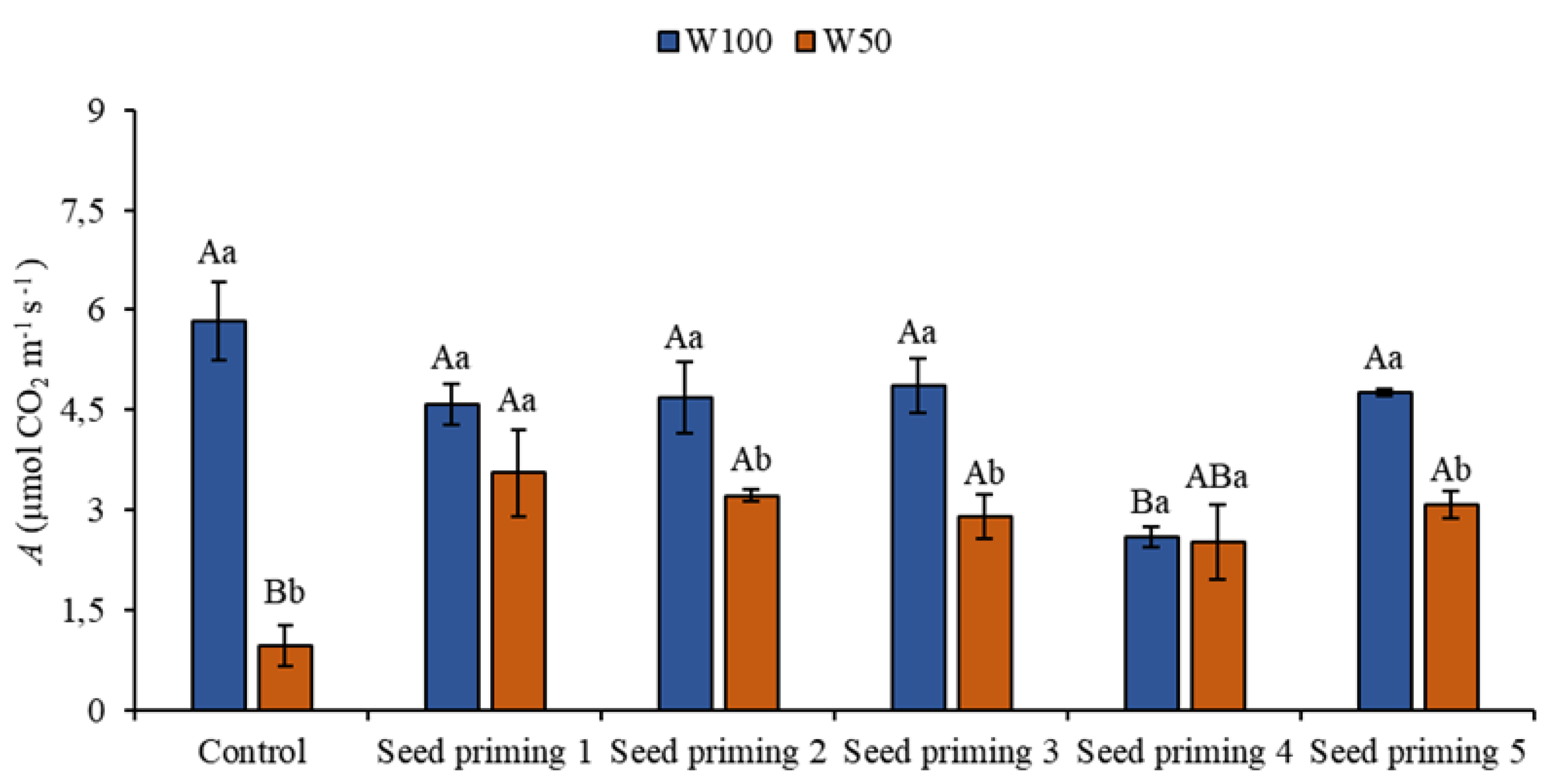

3.1. Photosynthetic Rate

The plants that were under water restriction (W50) showed reductions in photosynthesis regardless of the treatment when compared to the control (W100), corresponding to 84, 39, 45, 50, 57 and 47% (

Figure 2).

However, the plants that underwent treatment under water restriction, there were increases of 272, 236, 204, and 221% in seed priming 2, 3, 4, and 6 (

Table 1), respectively, when compared to the control under stress, reducing the effects of water restriction. Still evaluating carbon assimilation, there were decreases in the plants that underwent priming but received W100 water replenishment (

Figure 2).

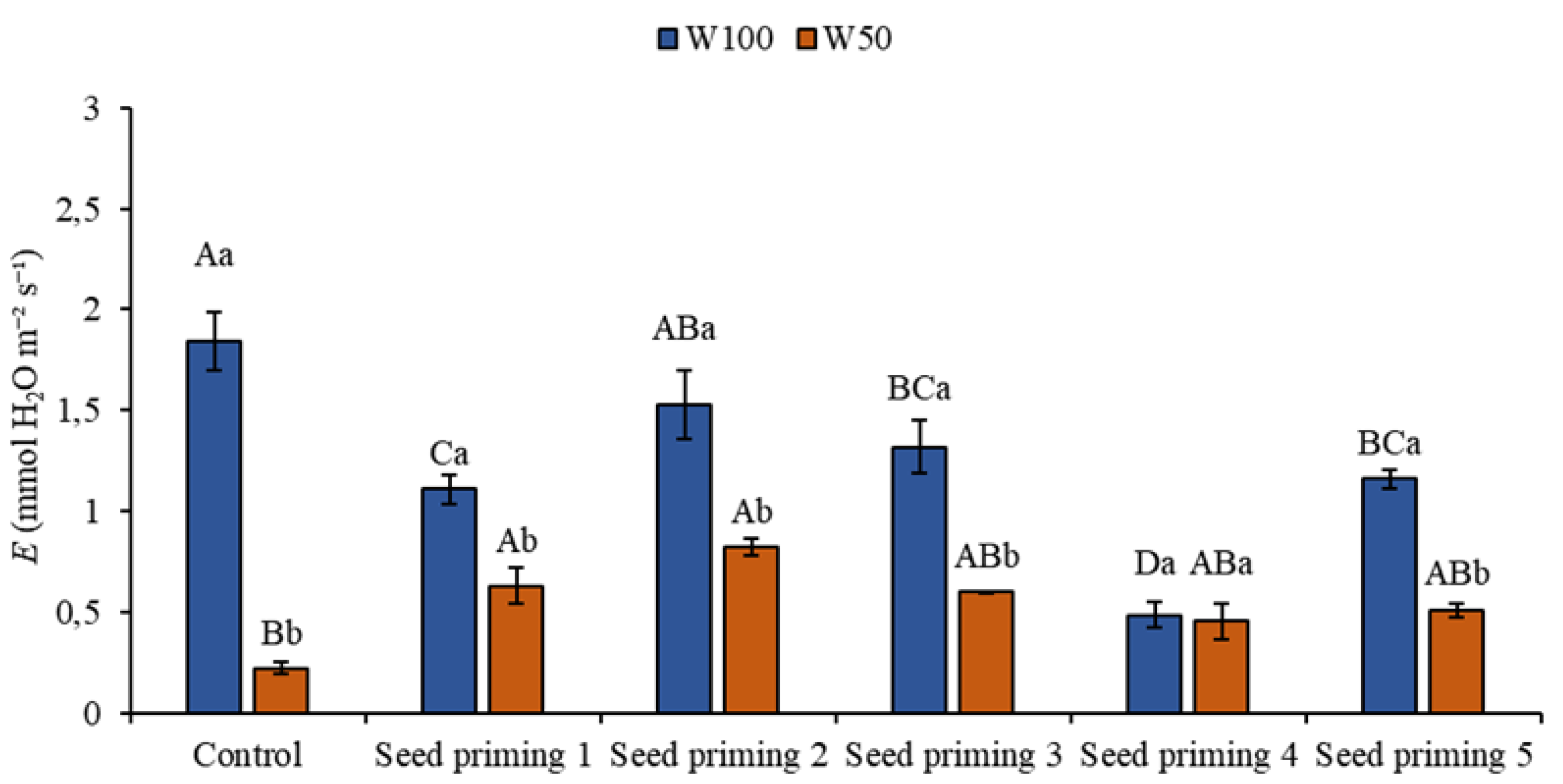

3.2. Transpiration Rate

Transpiration helps the roots absorb water from the soil by means of a negative pressure gradient that occurs in the plant. This gradient maintains the flow of water towards the atmosphere, against the force of gravity, through the conductive vessels, which can indirectly reflect the soil's water status. In the present study, when evaluating this variable, plants in the W50 layer had reductions in transpiration regardless of the treatments when compared to the control in the W100, this decrease constituting 88, 66, 55, 68, 75, and 72 % respectively in the primings.

However, there were notable increases of 187, 274, 173, 106, and 132 % in primings 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (

Figure 3) respectively. There was a statistical difference in primings 2 and 3 compared to the control on the same blade. When analyzing the behavior of the treatments under optimum irrigation conditions, there were reductions of 39, 16, 28, 73, and 37 % in this variable, which can be justified by the stomatal adjustment caused by the effect of seed priming, aiming for an improvement in water use efficiency (

Figure 3).

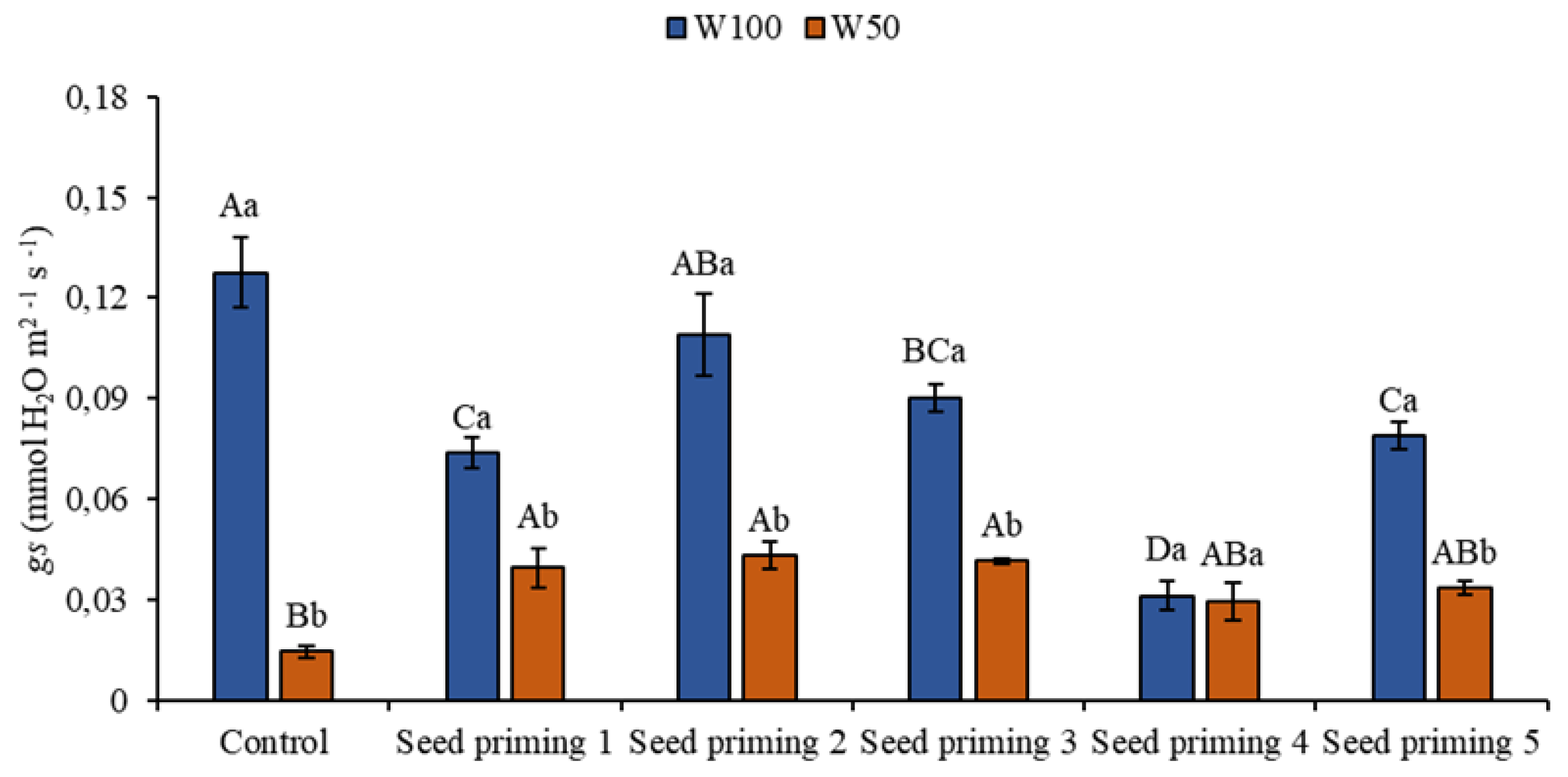

3.3. Stomatal Conductance

Water restriction also caused reductions in stomatal conductance (

gs) when the stressed plants were compared to the control plant at W100. These reductions amounted to 89, 69, 66, 67, 77, and 74% (

Figure 4). At W100, there were decreases in this parameter in all the plants that underwent priming, of 42, 15, 29, 76, and 38% (

Figure 4), when compared to the control plant at the same level.

Comparing the primings on the W50 blade, there were increases in primers 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, representing 172, 198, 186, 102 and 131% in relation to primer 1 in the same condition (

Figure 4). The positive results of this variable in the treatments were crucial, and reflected on other variables in the study, especially

E and

A. This is because stomatal conductance is a variable related to the stomatal mechanism in the processes of gas exchange, such as carbon dioxide (CO

2) and water vapor (H

2O), between the plant and the environment.

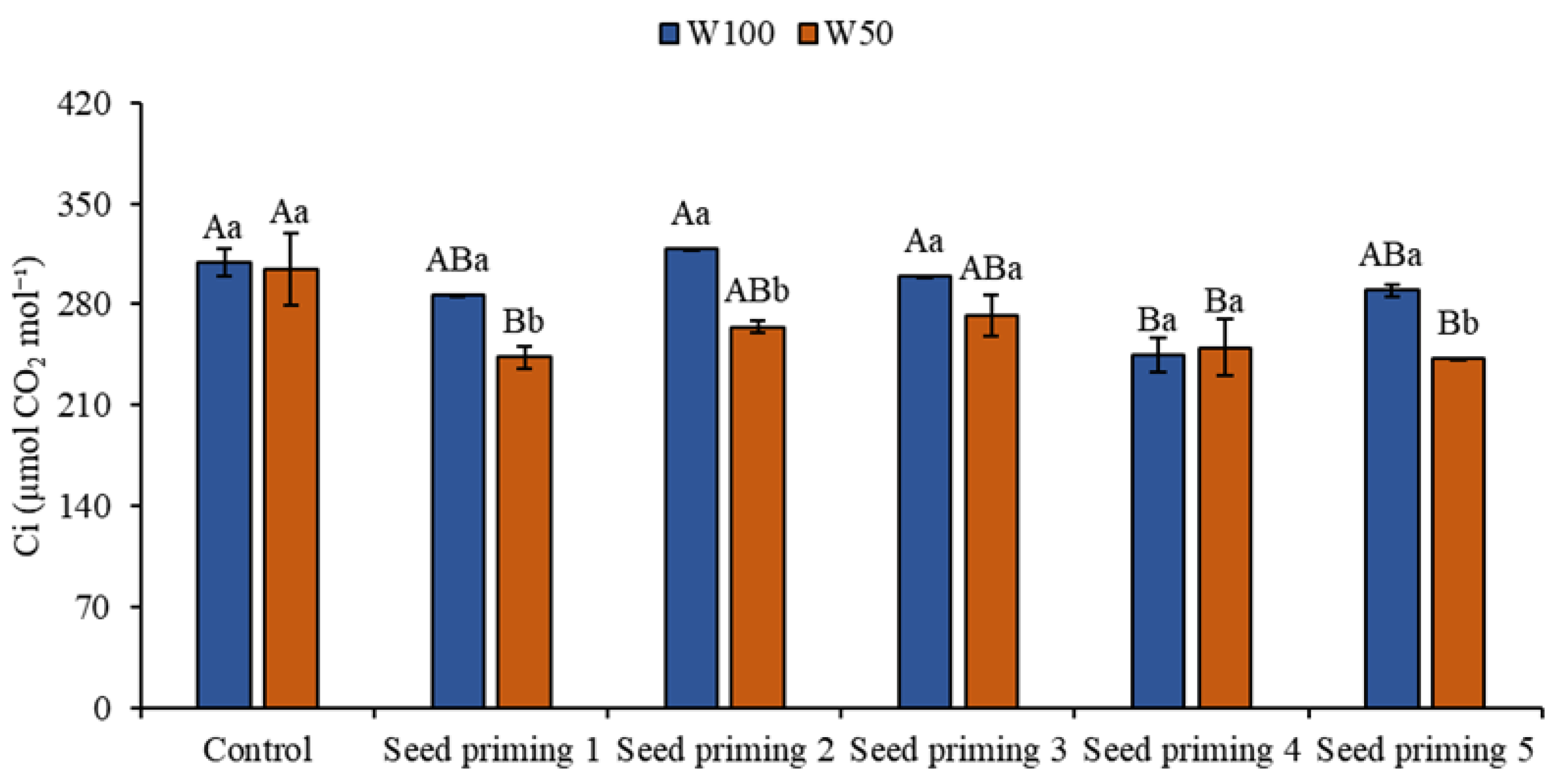

3.4. Intercellular Carbon Concentration

As for internal carbon, which refers to the concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) inside plant cells during the process of photosynthesis. Reductions in internal carbon were seen in all the treatments that underwent water restriction when compared to the W100 control, particularly for primers 2 and 6, with reductions of 21 and 22% respectively.

In the limiting condition, the control plant obtained the best result in this parameter under stress conditions, while the other treatments suffered reductions of 20, 13, 11, 18 and 20% in priming 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 compared to the control at the same level of water replacement. When W100 was analyzed, primings 2, 4, 5 and 6 did not show positive results, but rather decreases of 7, 3, 21 and 6% respectively. However, priming 3 at W100 provided a subtle increase of 3% in this variable when compared to the control at the same level (

Figure 5).

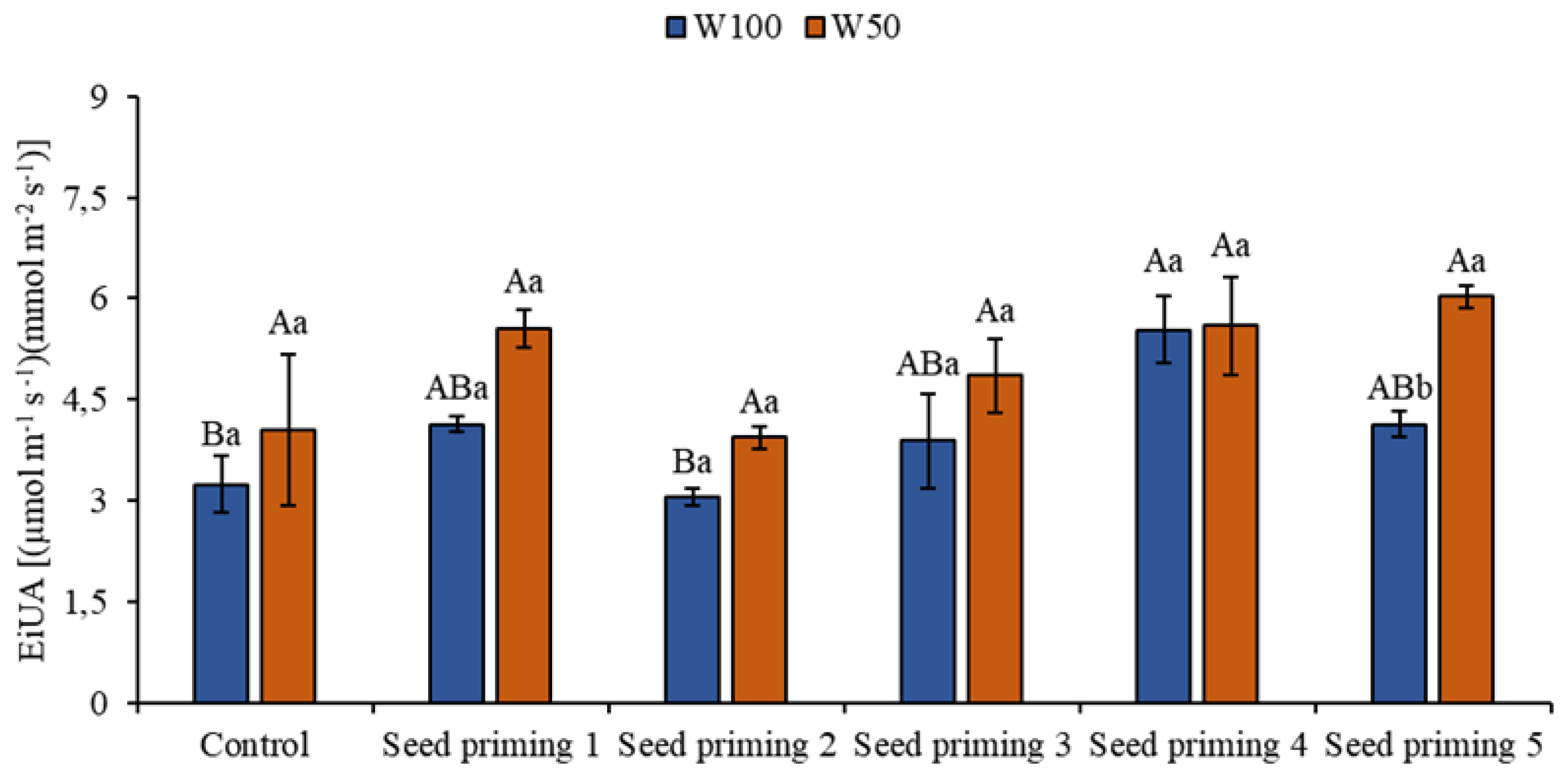

3.5. Instantaneous Efficiency of Water Us

The instantaneous efficiency of water use (EiUA) is a measure that relates a plant's rate of carbon assimilation to the amount of water that is lost through transpiration. It represents the efficiency with which a plant uses available water to produce biomass through photosynthesis. This physiological measure reflects the ability of plants to maximize the use of available water for plant growth and development.

The results of this research indicate that the primers obtained satisfactory results under stress conditions in all treatments, with increases of 72, 22, 50, 73, and 86%. When evaluating the treatments under water restriction, primings 2, 4, 5, and 6 had increases of 37, 20, 38, and 49% in relation to the control under the same water replacement. Similar to this result, priming 2, 4, 5 and 6 on the W100 blade had improvements compared to the control on the same blade, this improvement corresponding to 28, 20, 71, and 28% (

Figure 6).

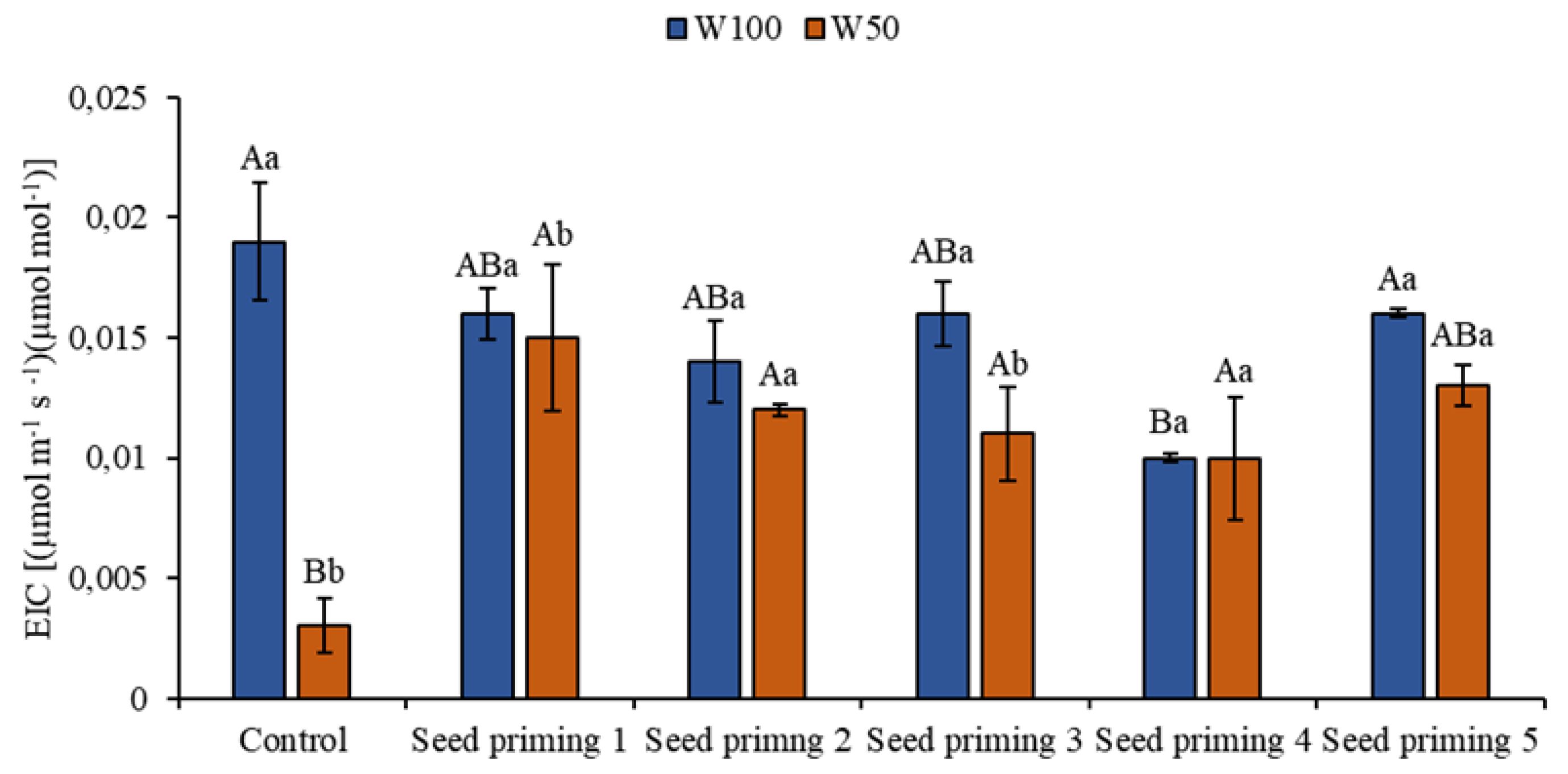

3.6. Instantaneous Carboxylation Efficiency

Water restriction also influenced instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (EiC), with reductions in all primings when compared to the control at W100. These reductions correspond to 84, 21, 37, 42, 47, and 32% for primings 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in the appropriate order. However, when evaluating the effect of the treatments, increases can be seen in primings 2 (400%), 3 (300%), 4 (267%), 5 (233%) and 6 (333%). On the other hand, W100 showed lower EiC values in all treatments when compared to SP1 on the same blade. These values are 16, 26, 16, 47, and 16% for primings 2 to 6 (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

4.1. Photosynthetic Rate

Corroborating the results of present study, negative changes in photosynthesis in cowpea was observed when water restriction was imposed [

22,

23]. These studies emphasize that, even though cowpea may show some tolerance to water restriction, this type of stress compromises the plant's development.

The reductions examined in carbon assimilation are directly linked to stomatal closure. Through this mechanism, plant species are able to restrict water loss and overcome periods of drought, mainly to maintain cell turgor [

22]. However, the plants that underwent priming showed significant increases in the photosynthetic rate, with increases of 272, 236, 204, and 221% in seed priming 2, 3, 4, and 6, respectively, when compared to the control under stress, reducing the effects of water restriction. On the other hand, this contributes to a decrease in CO

2 assimilation and transpiration, as it is a common pathway for both. Furthermore, when this flow is restricted, less CO

2 is available for fixation during photosynthesis, resulting in lower biomass production and limitations in plant growth and development [

24,

25].

4.2. Transpiration Rate

Also, these analyzed reductions in

gs reflect the soil's water status, indicating that the root system was unable to meet the water requirement and as a form of defense the plant develops greater stomatal resistance [

25]. In addition, another explanation for the decrease in the photosynthetic process lies in the fact that water stress can decrease chlorophyll content, resulting in considerable drops in gas exchange [

26].

4.3. Stomatal Conductance

However, the plants that underwent priming showed increases in

A,

E and

gs. This result may be related to the action of PEG 6000, which, during packaging, removes water from the seed's cell wall. This osmotic stress promotes the accumulation of solutes, causing greater cell turgor potential during seed rehydration, resulting in the emergence of the primary root in less time. This process can cause stress memory, thereby keeping the seedling alert to subsequent environmental stresses [

27]. In addition, it can stimulate the production of proline so that the plant can keep its water status regulated, enabling the plant to maintain its photosynthetic activities active [

27].

Silicon also contributes to this result. Its use in seed treatment has been growing over the years, showing its effectiveness in various crops studied, providing mitigation of the deleterious effects of water restriction [

28]. More specifically, it can help as a barrier, by accumulating in the leaf apoplasts and helping to improve photosynthesis [

29]. In addition, silicon plays an important role in the plant's defense system, which can increase the activity of the enzymes superoxide dismutase and peroxidase, which is an excellent line of defense for the plant against reactive oxygen species by mitigating the adverse effect of drought on plants [

30].

4.4. Intercellular Carbon Concentration

The results obtained for internal carbon (Ci) suggest that the reduction in CO

2 assimilation compromised this variable, which favored carbon accumulation and negatively influenced photosynthetic rates, as well as contributing to a decrease in instantaneous carboxylation efficiency. The increase in Ci can cause stomatal limitations, such as changes in their behavior and density [

31]. Therefore, the internal concentration of CO

2 in the leaf mesophyll is reduced by stomatal closure, with a consequent decrease in the rate of carbon assimilation [

23].

4.5. Instantaneous Efficiency of Water Use

The relationship between carbon assimilation and transpiration, known as instantaneous efficiency of water use (EiUA), expresses the acquired values of the amount of carbon that the plant fixes for each unit of H

2O that it releases through the stomata [

32]. Similarly, the instantaneous carboxylation efficiency, which reflects how efficient the metabolic reactions of carbon fixation are, through the relationship between internal carbon and carbon assimilation [

33].

These variables are of the utmost importance, as they reveal important mechanisms that allow plants to thrive even under adverse conditions. In this study, these two variables changed under the influence of water restriction. The lowest values for the EiUA rate were observed at W100. This type of response is reflected in increases in assimilation and transpiration rates [

34].

4.6. Instantaneous Carboxylation Efficiency

On the other hand, the decreases in EiC may have occurred due to a reduction in stomatal conductance, causing damage to its physiological processes, directly influencing CO

2 assimilation and impairing instantaneous carboxylation efficiency [

33].

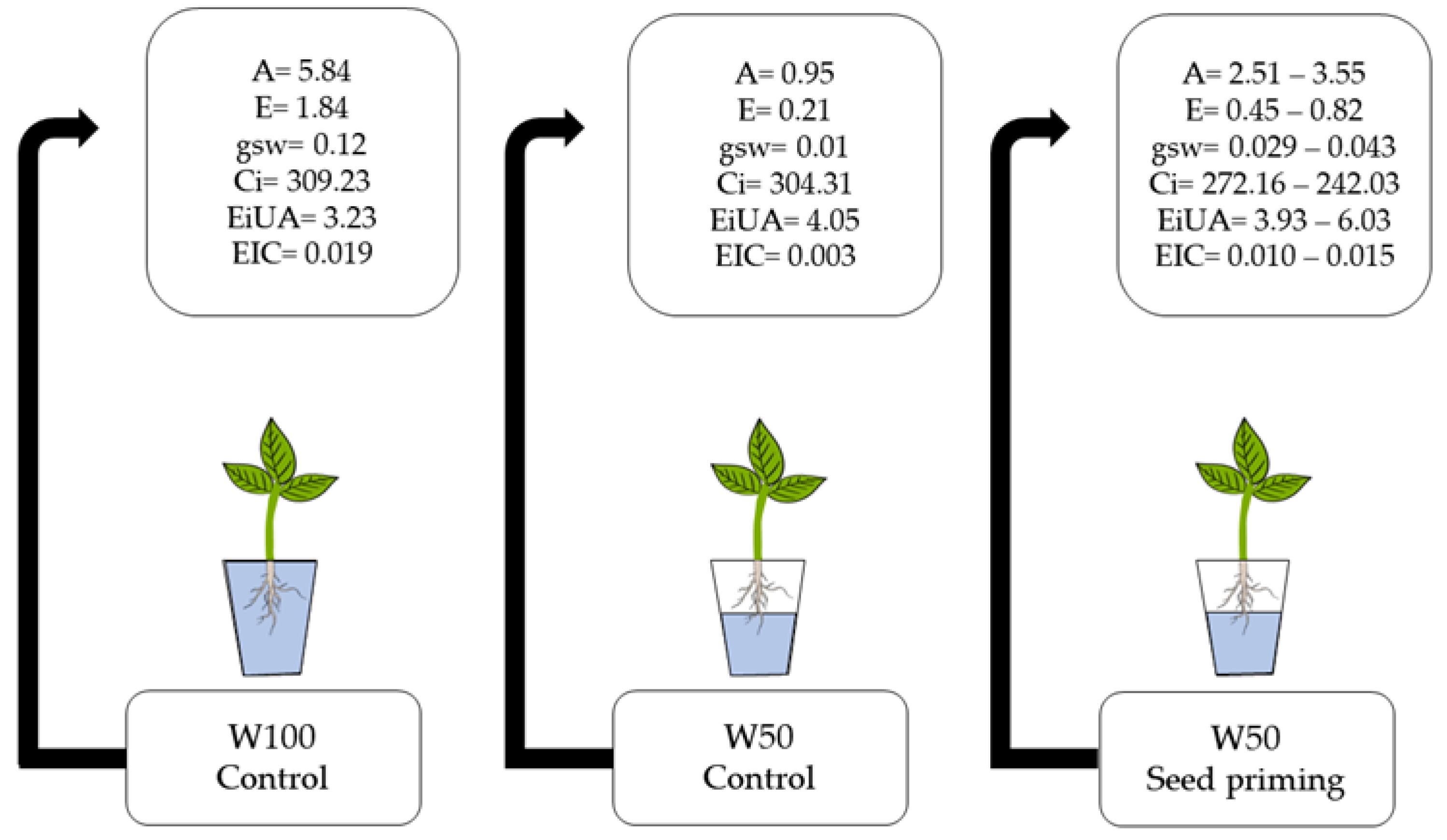

However, it is notorious that plants obtained from conditioned seeds acquire some kind of memory, standing out for being more tolerant to abiotic stress. The increases in EiUA under water restriction may have occurred as a result of greater proline production induced by PEG 6000 and enhanced by the action of silicon, given that osmoregulation is a key mechanism for improving this variable [

35]. On the other hand, the increases in instantaneous carboxylation efficiency are mainly due to the increases in internal carbon dioxide concentration and gains in CO

2 assimilation rates seen in this study [

23].

In addition, plants treated with PEG 6000 can trigger an improvement in the antioxidant defense system, acting against reactive oxygen species [

36]. This antioxidant process intensified by Si attenuates the negative effects of water stress, reducing lipid peroxidation and plasma membrane permeability [

37]. Generally speaking, the seeds obtained from PEG 6000 and silicon solutions performed better even under limiting water conditions (

Figure 8).

However, little is known about the combination of PEG 6000 and silicon in seed conditioning, although the action of silicon in seed conditioning was found by Özdemir [

38] in purple maize, which led to improvements in gas exchange, especially net carbon assimilation and transpiration. Bourioug et al. [

39] highlighted the increase in photosynthesis and transpiration of sunflower plants grown under water stress and conditioned with PEG 6000.

These studies reinforce the hypothesis that these materials can be used to induce tolerance to water stress. In addition, other factors can enhance the positive effects of seed priming, such as light conditions [

16]. However, it should be noted that few studies have been published on these combined factors in seed treatment.

5. Conclusion

In view of the above, it can be concluded that seed priming with PEG 6000 and silicic acid in the BRS Pingo de Ouro cultivar can provide increases in photosynthetic rates even when water restriction is imposed, mainly inducing better instantaneous water use efficiency and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency. Seed priming 2 (40 °C + Ψw 0 MPa + 200 mg L-1 Si + RL), 3 (40 °C + Ψw -0.4 MPa + 0 mg L-1 Si + RL) and 4 (40 °C + Ψw -0.4 MPa + 200 mg L-1 Si + RL) proved to be more efficient in improving gas exchange. This may reveal a possible ideal combination for this type of treatment, with a view to making it viable to grow cowpeas under conditions of water restriction, guaranteeing food security.

Author Contributions

Guilherme Felix Dias: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Rayanne Silva de Alencar – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Priscylla Marques de Oliveira Viana: Resources, Formal analysis. Igor Enes Cavalcante: Resources, Formal analysis. Emmanuelly Silva Dias de Farias: Resources, Formal analysis. Semako Ibrahim Bonou: Resources, Formal analysis. Jonnathan Richeds da Silva Sales: Writing – review & editing. Hermes Alves de Almeida: Resources, Formal analysis. Rener Luciano de Souza Ferraz: Resources, Formal analysis. Claudivan Feitosa de Lacerda: Writing – review & editing. Sérgio de Faria Lopes: Resources, Formal analysis. Alberto Soares de Melo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) Brazil, finance code 001. To the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq, for granting financial aid (Proc. 408952/2021-0 and 307559/2022-0) and the Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado da Paraíba (Edital Fapesq-PB/CNPq no. 77/2022 and Edital no. 004/2018 – SEIRHMACT/Fapesq-PB).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ferguson, J. N. Climate change and abiotic stress mechanisms in plants. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences 2019, 3, 165-181. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L. I. S.; Brito, A. E. A.; Souza, L. C.; Teixeira, K. B. S.; Nascimento V. R.; Albuquerque, G. D. P.; Oliveira Neto, C. F.; Okumura, R. S.; Nogueira, G. A. S.; Freitas, J. M. N.; Monteiro, G. G. T. N. Does silicon attenuate PEG 6000-induced water deficit in germination and growth initial the seedlings corn. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2023, 83, e265991. [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, T. W.; Gerrano, A. S.; Mbuma, N. W.; Labuschagne, M. T. Breeding of vegetable cowpea for nutrition and climate resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa: Progress, Opportunities, and Challenges. Plants 2022, 12, e1583. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R.; Brown, L. K.; George, T. S.; Pakeman, R. J.; Palmer, S.; Ramsay, L.; Schöb, C.; Schurch, N.; Wilkinson, M. J. Active and adaptive plasticity in a changing climate. Trends in Plant Science 2022, 27, 717-728. [CrossRef]

- Melo, A. S.; Silva, A. R. F.; Dutra, A. F.; Dutra, W. F.; Brito, M. E. B.; Sá, F. V. S. Photosynthetic efficiency and production of cowpea cultivars under deficit irrigation. Revista Ambiente & Água 2018, 13, e2133. [CrossRef]

- Martey, E.; Etwire, P. M.; Adogoba, D. S.; Tengey, T. K. Farmers’ preferences for climate-smart cowpea varieties: implications for crop breeding programmes. Climate and Development 2021, 14, 105-120. [CrossRef]

- Collado, E.; Klug, T. V.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Aguayo, E.; Artés, F.; Fernández, J. A.; Gómez, P. A. Quality changes in nutritional traits of fresh-cut and then microwaved cowpea seeds and pods. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2019, 12, 338-346. [CrossRef]

- Fasuan, T. O.; Chukwu, C. T.; Uchegbu, N. N.; Olagunju, T. M.; Asadu, K. C.; Nwachukwu, M. C. Effects of pre-harvest synthetic chemicals on post-harvest bioactive profile and phytoconstituents of white cultivar of Vigna unguiculata grains. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2022, 46, e16187. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, D. G.; Oliveira, L. M.; Guedes, M. O.; Ferreira, G. F. P.; Prado, T. R.; Amaral, C. L. F. Desempenho da cultivar de feijão-caupi BRS Novaera sob níveis de irrigação e adubação em ambiente protegido. Revista Cultura Agronômica 2020, 29, 61. [CrossRef]

- Boukar, O.; Belko, N.; Charmarthi, S.; Togola, S.; Batieno, J.; Owusu, E.; Haruna, M.; Diallo, S.; Umar, M. L.; Olufajo, O.; Fatokun, C. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata): Genetics, genomics and breeding. Plant breeding 2019, 138, 415-424. [CrossRef]

- Saka, J. O.; Agbeleye, O. A.; Ayoola, O. T.; Lawal, B. O.; Adetumbi, J. A.; Oloyede-Kamiyo, Q. O. Assessment of varietal diversity and production systems of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) in Southwest Nigeria. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics 2019, 119, 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Arnott, A.; Galagedara, L.; Thomas, R.; Cheema, M.; Sobze, J. M. The potential of rock dust nanoparticles to improve seed germination and seedling vigor of native species: A review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 775, 145139. [CrossRef]

- Boucelha, L.; Djebbar, R.; Abrous-Belbachir, O. Vigna unguiculata seed priming is related to redox status of plumule, radicle and cotyledons. Functional Plant Biology 2019, 46, 584-594. [CrossRef]

- Nabi, F.; Chaker-Haddadj, A.; Chebaani, M.; Ghalem, A.; Mebdoua, S.; Ounane, S. M. Influence of seed priming on early stages growth of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.] grown under salt stress conditions. Legume Research: An International Journal 2020, 43, 665-671. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. A.; Paiva, E. P.; Torres, S. B.; Souza-Neta M. L.; Pereira, K. T. O.; Leite, M. S.; Sá, F. V. S.; Benedito, C. P. Osmoprotection in Salvia hispanica L. seeds under water stress attenuators. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2022a, 82, e233547. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. S.; Ferraz, R. L. S.; Dantas-Neto J.; Martins, V. D.; Viégas, P. R. A.; Meira, K. S.; Ndhlala, A. R.; Azevedo, C. A. V.; Melo, A. S. Seed priming with light quality and Cyperus rotundus L. extract modulate the germination and initial growth of Moringa oleifera Lam. seedlings. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2024, 84, e255836. [CrossRef]

- Vidak, M.; Lazarević, B.; Nekić, M.; Šatović, Z.; Carović-Stanko, K. effect of hormonal priming and osmopriming on germination of winter savory (satureja montana L.) natural population under drought stress. Agronomy 2022, 12,1288. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, R. S.; Dias, G. F.; Araujo, Y. M. L.; Oliveira-Viana, P. M.; Borborema, D. A.; Bonou, S. I.; Sales, J. R. S.; Cavalcante, I. E. Barroso, V. S. F.; Schneider, R. Ferraz, R. L. S.; Melo, A. S. Seed priming with residual silicon-glass microparticles mitigates water stress in cowpea. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 328, 112933. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. E. S.; Ferraz, R. L. S.; Silva, J. P.; Costa, P. S.; Viegas, P. R. A.; Brito Neto, J. F.; Melo, A. S.; Meira, K. S.; Soares, C. S.; Magalhaes, I. D.; Medeiros, A. S. Microclimate changes, photomorphogenesis and water consumption of Moringa oleifera cuttings under different light Spectrums and exogenous phytohormone concentrations. Australian Journal Crop Science 2020, 14, 751-760. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S. S.; Wilk, M. B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika Trust 1965, 52, 591-609. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. F. SISVAR: A computer analysis system to fixed effects split plot type designs. Brazilian Journal of Biometrics 2019, 37, 529-535. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D. P.; Sousa, D. P.; Nunes, H. G. G. C.; Pinto, J. V. N.; Farias, V. D. S.; Costa, D. L. P.; Moura, V. B.; Teixeira, E.; Sousa, A. M. L.; Pinheiro, H. A.; Souza, P. J. d. O. P. Cowpea ecophysiological responses to accumulated water deficiency during the reproductive phase in northeastern Pará, Brazil. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 116. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A. P. S.; Melo, Y. L.; Alencar, R. S.; Viégas, P. R. A.; Dias, G. F.; Ferraz, R. L. S.; Sá, F. V. S.; Dantas Neto, J.; Magalhães, I. D.; Gheyi, H. R.; Lacerda, C. F.; Melo, A. S. Osmoregulatory and antioxidants modulation by salicylic acid and methionine in cowpea plants under the water restriction. Plants 2023, 12, 1341. [CrossRef]

- Costa, D. L. P.; Takaki, A. Y.; Silva Farias, V. D.; Oliveira Teixeira, E.; Nunes, H. G. G. C.; Souza, P. J. O.P. Stomatal Conductance of Cowpea Submitted to Different Hydric Regimes in Castanhal, Pará, Brazil. Journal of Agricultural Studies 2019, 8, 138-149. [CrossRef]

- Mndela, M.; Tjelele, J. T.; Madakadze, I. C.; Mangwane, M.; Samuels, I. M.; Muller, F.; Pule, H. T. A global meta-analysis of woody plant responses to elevated CO2: implications on biomass, growth, leaf N content, photosynthesis and water relations. Ecological Processes 2022, 11, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Ashraf, M. A.; Hussain, I.; Parveen, S.; Rasheed, R.; Mahmood, Q. Promotion of growth and physiological characteristics in water-stressed Triticum aestivum in relation to foliar-application of salicylic acid. Water 2021, 13, 1316. [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. S.; Ferraz, R. L. S.; Dantas Neto, J.; Bonou, S. I.; Cavalcante, I. E.; Alencar, R. S.; Melo, Y. L.; Magalhães, I. D.; Ndhlala, A. R.; Schneider, R.; Azevedo, C. A. V.; Melo, A. S. Seed Priming with Glass Waste Microparticles and Red Light Irradiation Mitigates Thermal and Water Stresses in Seedlings of Moringa oleifera. Plants 2022b, 11, 2510. [CrossRef]

- Dias, G. F.; Alencar, R. S.; Araújo, Y. M. L.; Oliveira-Viana, P. M.; Costa, D. T.; Melo, A. S. Seed priming com silício para indução de tolerância a estresses abióticos: uma revisão sistemática. ed. COELHO, B. E. S. Pesquisa Científica e Inovação em Ciências Agrárias. São Paulo/SP: ISTC Assessoria e Consultoria. 2022, 483-493.

- Merwad, A. R. M. A.; Desoky, E. S.; Rady M. M. Response of water deficit-stressed Vigna unguiculata performances to silicon, proline or methionine foliar application. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 228, 132-144. [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. A. S.; Zulfiqar, B.; Iqbal, R.; Muzamil, M. N.; Aslam, M. U.; Muhammad, F.; Amin, J.; Aslam, H. M. U.; Ibrahim, M. A.; Uzair, M.; Habib-ur-Rahman, M. Morpho-physiological and biochemical response of wheat to various treatments of silicon nano-particles under drought stress conditions. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 2700. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, T.; Milliken, A. L. Photosynthesis–beyond the leaf. New Phytologist 2023, 238, 55-61. [CrossRef]

- Freire, M. H. C.; Sousa, G. G.; Ceita, E. D. A. R.; Barbosa, A. S.; Goes, G. F.; Lacerda, C. F. Gas exchange of fava bean varieties under salinity conditions of irrigation water. Agrarian 2021, 14, 61-70. [CrossRef]

- Jacinto Júnior, S. G.; Moraes, J. G. L.; Silva, F. B.; Silva, B. N.; Sousa, G. G.; Oliveira, L. L. B.; Mesquita, R. O. Respostas fisiológicas de genótipos de fava (Phaseolus lunatus L.) submetidas ao estresse hídrico cultivadas no Estado do Ceará. Revista Brasileira de Meteorologia 2019, 34, 413-422. [CrossRef]

- Jayawardhane, J.; Goyali, J. C.; Zafari, S.; Igamberdiev, A. U. The response of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) plants to three abiotic stresses applied with increasing intensity: hypoxia, salinity, and water deficit. Metabolites 2022, 12, 38. [CrossRef]

- Melo, A. S.; Melo, Y. L.; Lacerda, C. F.; Viégas, P. R.; Ferraz, R. L. S.; Gheyi, H. R. Water restriction in cowpea plants [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.]: Metabolic changes and tolerance induction. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental 2022, 26, 190-197. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Ullah, S.; Nafees, M. Effect of seed priming on growth and performance of Vigna radiata L. under induced drought stress. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 4, e100140. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, A. L.; Muneer, S.; Kim, Y. H.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Al-Harrasi, A. Silicon and salinity: crosstalk in crop-mediated stress tolerance mechanisms. Frontiers in plant Science 2019, 10, 1429. [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, E. Silicon stimulated bioactive and physiological metabolisms of purple corn (Zea mays indentata L.) under deficit and well-watered conditions. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Bourioug, M.; Ezzaza, K.; Bouabid, R.; Alaoui-Mhamdi, M.; Bungau, S.; Bougead, P.; Alaoui-Sossé, L.; Alaoui-Sossé, B.; Aleya, L. Influence of hydro-and osmo-priming on sunflower seeds to break dormancy and improve crop performance under water stress. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 13215-13226. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Methodological flowchart for stage 1. Stage 1: Sorting the seeds; stage 2: sterilization of the seeds in sodium hypochlorite solution; stage 3: Seeds placed in the substrate with the appropriate treatments; stage 4: Gerboxes containing the seeds conditioned in a B.O.D. germination chamber adapted with LED strips; stage 5: Seeds obtained from the conditioning are sown in the pots and stage 6: Conducting the experiment (Stage II).

Figure 1.

Methodological flowchart for stage 1. Stage 1: Sorting the seeds; stage 2: sterilization of the seeds in sodium hypochlorite solution; stage 3: Seeds placed in the substrate with the appropriate treatments; stage 4: Gerboxes containing the seeds conditioned in a B.O.D. germination chamber adapted with LED strips; stage 5: Seeds obtained from the conditioning are sown in the pots and stage 6: Conducting the experiment (Stage II).

Figure 2.

Carbon assimilation (A) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2.

Carbon assimilation (A) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Transpiration (E) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and combinations of seed priming. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Transpiration (E) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and combinations of seed priming. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Stomatal conductance (gs) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Stomatal conductance (gs) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5.

Internal carbon (Ci) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5.

Internal carbon (Ci) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 6.

Instantaneous water use efficiency (EiUA) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 6.

Instantaneous water use efficiency (EiUA) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 7.

Instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (EiC) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 7.

Instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (EiC) of the cowpea cultivar BRS Pingo de ouro, conditioned to two irrigation rates (W100 and W50, corresponding to 100 and 50% of crop evapotranspiration water replacement) and seed priming combinations. Ψw: water potential in Mega Pascal (MPa); and Si: silicon in milligrams per liter (mg L-1). Capital letters differentiate between seed priming combinations (Tukey P ≤ 0.05). Lowercase letters differentiate between irrigation rates (t-student P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 8.

Summary of results, W100 Control: Shows the values obtained from the control under normal irrigation conditions; W50 control: Shows the values obtained from the control under limiting irrigation conditions and W50 Seed priming: Shows the minimum and maximum value of each independent variable of the treatment under limiting irrigation conditions.

Figure 8.

Summary of results, W100 Control: Shows the values obtained from the control under normal irrigation conditions; W50 control: Shows the values obtained from the control under limiting irrigation conditions and W50 Seed priming: Shows the minimum and maximum value of each independent variable of the treatment under limiting irrigation conditions.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of the treatments used in the experiment.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of the treatments used in the experiment.

| Identification |

Seed priming combinations |

| Control |

Ψw 0 MPa + 0 mg L-1 of Si + RL |

| Seed priming 2 |

Ψw 0 MPa + 200 mg L-1 of Si + RL |

| Seed priming 3 |

Ψw -0.4 MPa + 0 mg L-1 of Si + RL |

| Seed priming 4 |

Ψw -0.4 MPa + 200 mg L-1 of Si + RL |

| Seed priming 5 |

Ψw -0.8 MPa + 0 mg L-1 of Si + RL |

| Seed priming 6 |

Ψw -0.8 MPa + 200 mg L-1 of Si + RL |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).