1. Introduction

Cowpea (

Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) is an annual legume native to Africa and cultivated worldwide, with a particular emphasis on tropical regions [

1]. This crop is recognized for its high nutritional potential and plays a fundamental role in food security across various countries, serving as a rich source of proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals for human consumption and an important forage source for animal feed [

2]. Another relevant aspect is its contribution to soil ecological balance, as it promotes biological nitrogen fixation associated with nodulating bacteria [

3].

In Brazil, cowpea is widely cultivated in the northeastern region, playing a significant role in job creation and income generation for family farming [

4]. In the 2023/2024 growing season, national cowpea production reached 691.8 thousand tons, accounting for approximately 21.3% of the country's total bean production [

5]. However, despite its socio-economic importance, cowpea still exhibits relatively low yield compared to other bean species, primarily due to the predominance of cultivation under limited water availability [

5,

6,

7].

Water deficit is one of the main abiotic factors negatively impacting global agriculture, particularly in semi-arid regions where cowpea cultivation is predominant [

3]. This type of stress affects various morphological, physiological, biochemical, and molecular traits, leading to significant reductions in crop growth and yield [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Management strategies to increase plant tolerance to water deficit have been widely studied in this context.

Among the promising alternatives, silicon (Si) application stands out as a beneficial element that, although not essential, has great potential to mitigate abiotic stresses such as drought. Studies indicate that silicon can stimulate the accumulation of osmoregulators, enhance antioxidant capacity, optimize photosynthesis, improve nutrient uptake, and preserve the structural integrity of plant cells, resulting in benefits for various crops [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Despite these advancements, knowledge gaps remain regarding the impact of silicon fertilization on cowpea genotypes under water deficit conditions in semi-arid environments.

Understanding the mechanisms of water deficit tolerance in this species is essential, particularly regarding foliar silicon application combined with different irrigation depths. Applying silicon-based compounds to leaves aims to compensate for the low root uptake in soils with limited silicon availability, promoting greater absorption and enhancing silicon's beneficial effects [

17]. By activating physiological processes, this practice can increase plant tolerance to water stress, providing valuable insights for optimizing management practices. As a result, improving water use efficiency and, consequently, enhancing crop yield and farmers' profitability is possible.

Given this context, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of foliar silicon application on cowpea cultivars subjected to both deficit and adequate irrigation regimes. The focus was on analyzing foliar nutrient concentrations, proline accumulation, antioxidant enzyme activity, vegetative growth, water use efficiency, and crop yield performance.

3. Discussion

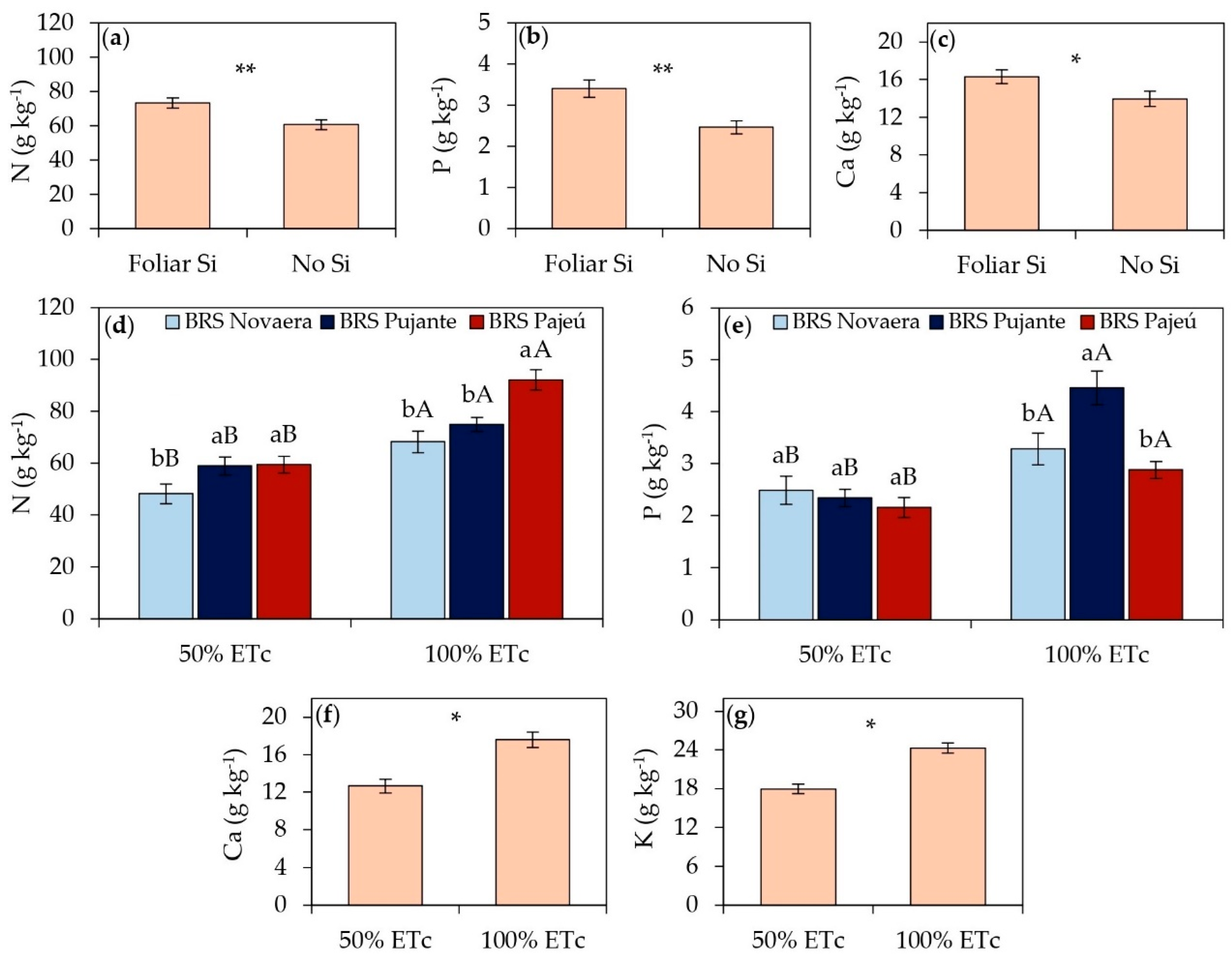

The foliar application of silicic acid significantly increased foliar nitrogen (

Figure 1a), phosphorus (

Figure 1b), and calcium (

Figure 1c) contents in cowpea cultivars, supporting studies that highlight the role of silicon in nutrient uptake and accumulation in plants [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Among these nutrients, the increase in foliar N content may be associated with silicon's influence on nitrogen metabolism regulation and its enhancement of biological nitrogen fixation [

18,

22]. Hao et al. [

22] reported that nano-SiO₂ application in maize stimulated the activity of enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism, such as glutamine synthetase, glutamate decarboxylase, and glutamate dehydrogenase, promoting greater efficiency in nitrogen assimilation in both leaves and roots.

In addition to silicon's influence on nitrogen enzyme metabolism, Mali and Aeri [

18] observed that soil silicon application, up to certain doses, stimulated root nodulation in cowpeas, promoting greater biological nitrogen fixation by symbiotic bacteria. This effect may be related to strengthening plant-microorganism interactions, possibly due to the increased availability of organic compounds exuded by roots in response to silicon [

23]. Thus, silicon's role in modulating nitrogen uptake and assimilation and its positive impact on nodulation and biological fixation may have been a key factor in increasing foliar nitrogen content in cowpeas. This effect can be particularly relevant in soils with low nitrogen availability, where biological fixation is essential for an adequate nutrient supply.

In addition to nitrogen, phosphorus also showed a significant increase in silicon-treated plants (

Figure 1b), suggesting a positive effect of Si on P acquisition and translocation, possibly through the regulation of genes involved in nutrient transport, as observed by Kostic et al. [

23] in wheat. In their study, soil silicon application increased the expression of the TaPHT1;1 and TaPHT1;2 genes, which encode inorganic phosphate transporters, promoting phosphorus uptake by plants. Furthermore, these authors reported that silicon enhanced the exudation of carboxylates by roots, potentially increasing phosphorus availability in the rhizosphere and contributing to greater nutrient efficiency. It is hypothesized that a similar mechanism may have contributed to the higher P levels observed in silicon-treated cowpea plants.

The increase in foliar calcium contents (

Figure 1c) further reinforces the role of silicon in nutrient acquisition by cowpeas. This effect may be associated with silicon's ability to mitigate early-stage plant stress by promoting cell membrane stability and stimulating the activity of H⁺-ATPase, an essential enzyme for ion transport [

18,

19]. The regulation of this mechanism may explain the higher Ca accumulation in cowpea leaves observed in the present study.

Although the benefits of silicon in nitrogen, phosphorus, and calcium uptake are evident, potassium contents in treated plants were not significantly influenced by Si application (

Table 1), representing a noteworthy finding. Potassium is essential for transpiration control, stomatal guard cell turgor regulation, carbohydrate translocation, and various enzymatic reactions [

24]. While some studies suggest that silicon may enhance potassium uptake in certain crops, its effects are still not fully understood [

19]. Therefore, other factors may have contributed to the observed results. Narwal et al. [

25] reported antagonism between K and Ca in cowpea plants, where a high concentration of one ion can reduce the uptake of the other. In sorghum, Chen et al. [

26] found that silicon application did not influence K levels in the shoots or roots but increased the photosynthetic rate and plant biomass. A molecular analysis conducted by the same authors in Arabidopsis [

26] showed that Si application did not induce the expression of HAK5 and AKT1 genes responsible for K⁺ uptake.

In the literature, there is extensive evidence that the effects of silicon on nutrient uptake in plants vary widely depending on factors such as plant species, environmental conditions, and the mode of application of the element, among others [

18,

19,

21,

27]. Mali and Aery [

18] observed that soil Si addition increased foliar P and Ca levels up to a certain threshold in cowpeas, but excessive doses reduced nutrient accumulation in plants. In contrast, Jam et al. [

27] reported that in Carthamus tinctorius, foliar application of Si at 2.5 mM increased Ca levels only in plants grown under irrigation with high-quality water, with no significant effect under salt stress. These findings suggest that specific environmental factors in the cultivation system may condition the impact of Si.

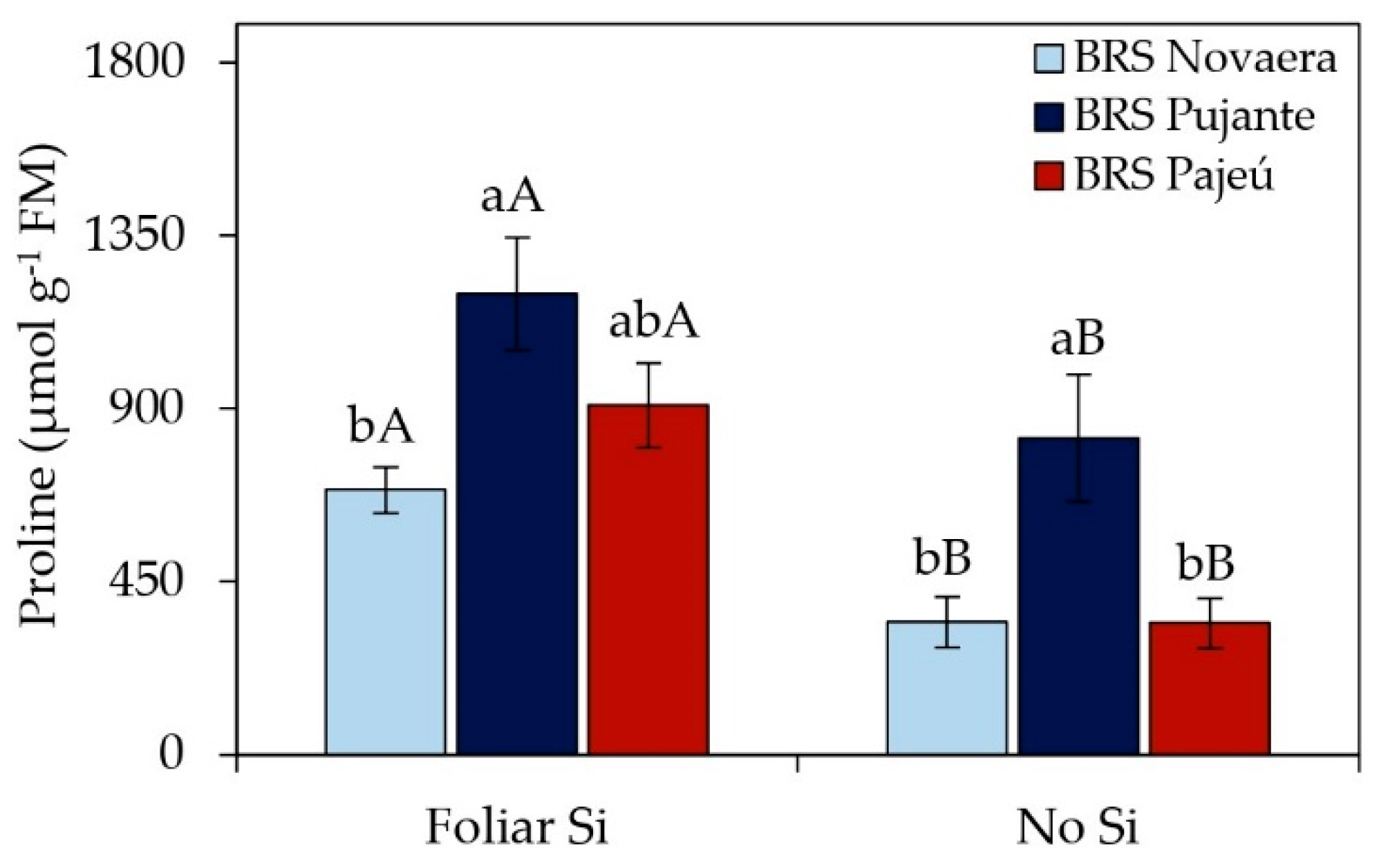

Proline is a key osmolyte in response to abiotic stresses, playing a role in osmoregulation, protection against oxidative damage, regulation of stress tolerance-related gene expression, and maintenance of water balance, among other functions [

28,

29,

30,

31]. In the present study, a significant increase in proline levels was observed in silicon-treated plants (

Figure 2), suggesting that this element may have played a crucial role in activating osmoprotection mechanisms. The rise in proline levels in response to silicon may be associated with its ability to mitigate the effects of water stress by reducing cellular water loss and protecting macromolecules from denaturation and peroxidation [

31,

32].

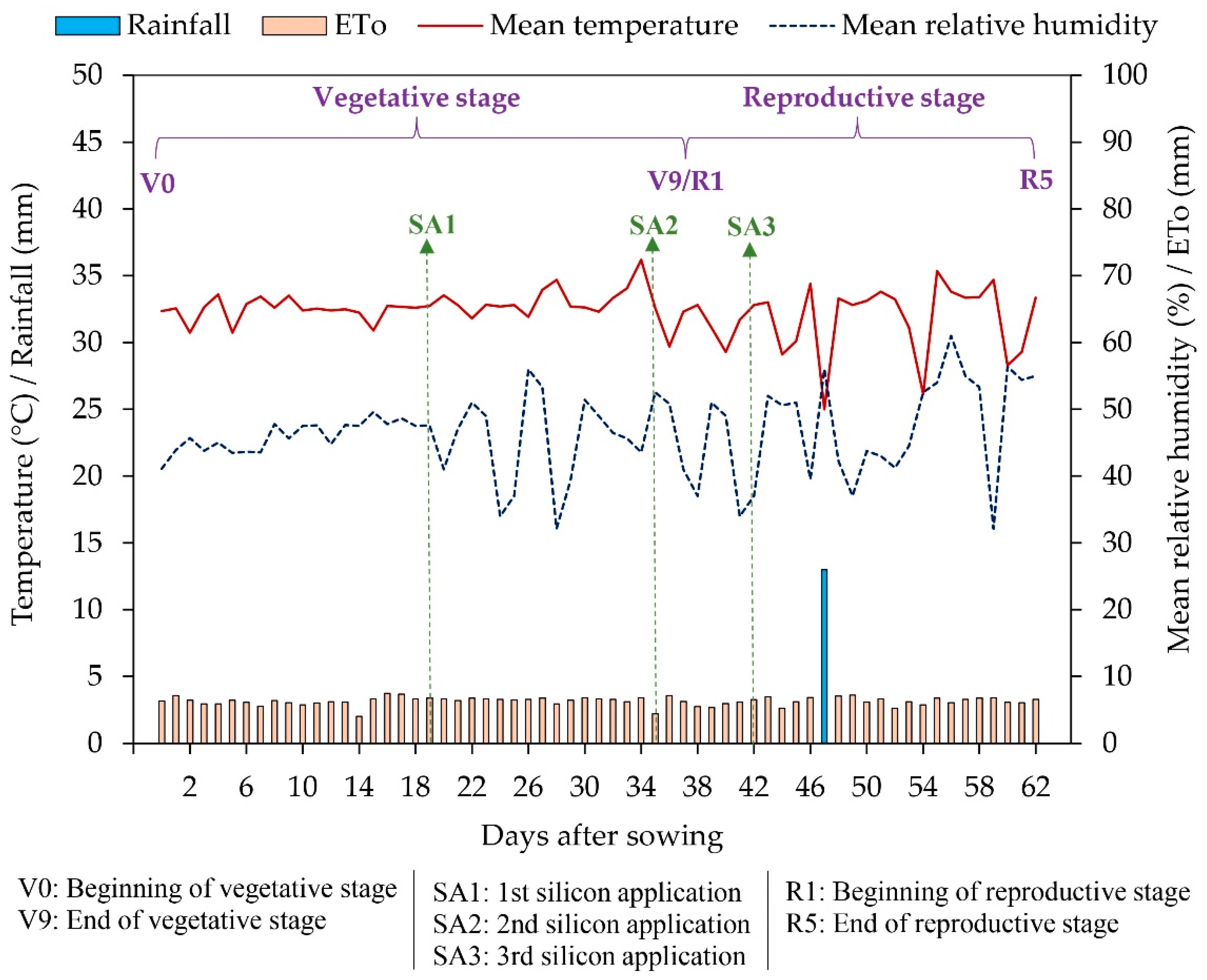

Although irrigation depths did not have a significant effect on proline content (

Table 1), the increase promoted by silicon is relevant for enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stresses, especially considering that the experiment was conducted in a semi-arid region characterized by high temperatures, intense solar radiation, and low relative humidity (

Figure 8). Santos et al. [

31] also reported increased proline levels in cowpea cv. BRS Guariba in response to foliar silicon application, conferring greater tolerance to water stress. However, the specific mechanisms by which silicon stimulates proline synthesis are not fully understood, highlighting the need for further studies.

Based on the results obtained for antioxidant activity (

Figure 3), it is evident that the response of cowpea cultivars is modulated by both water conditions and silicon application, which aligns with previous studies [

31,

32,

33]. The increase in SOD activity under water deficit (

Figure 3a) confirms that water deficiency intensifies the production of reactive oxygen species, thereby stimulating plant antioxidant defense mechanisms [

31]. However, silicon application also influenced the antioxidant response in cowpea, increasing SOD (

Figure 3b) and CAT (

Figure 3c) activities, demonstrating the effectiveness of this element in mitigating oxidative damage. SOD plays a key role in converting superoxide radicals (O₂⁻) into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), while CAT catalyzes the decomposition of H₂O₂ into water and oxygen, preventing the accumulation of reactive oxygen species and subsequent lipid peroxidation in cell membranes [

34].

Notably, when treated with silicon, the BRS Novaera cultivar exhibited a substantial 62% increase in APX activity under water deficit (

Figure 3e). APX plays a crucial role in H₂O₂ elimination through the ascorbate-glutathione cycle, a fundamental mechanism for oxidative homeostasis under stress conditions [

34]. These results reinforce that silicon is key in regulating oxidative stress in cowpeas cultivated under adverse conditions, as observed in other studies [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Similarly, studies by Santos et al. [

31] and Silva et al. [

32] also reported increased antioxidant enzyme activities in cowpeas under water stress, confirming the importance of Si in regulating these defense mechanisms.

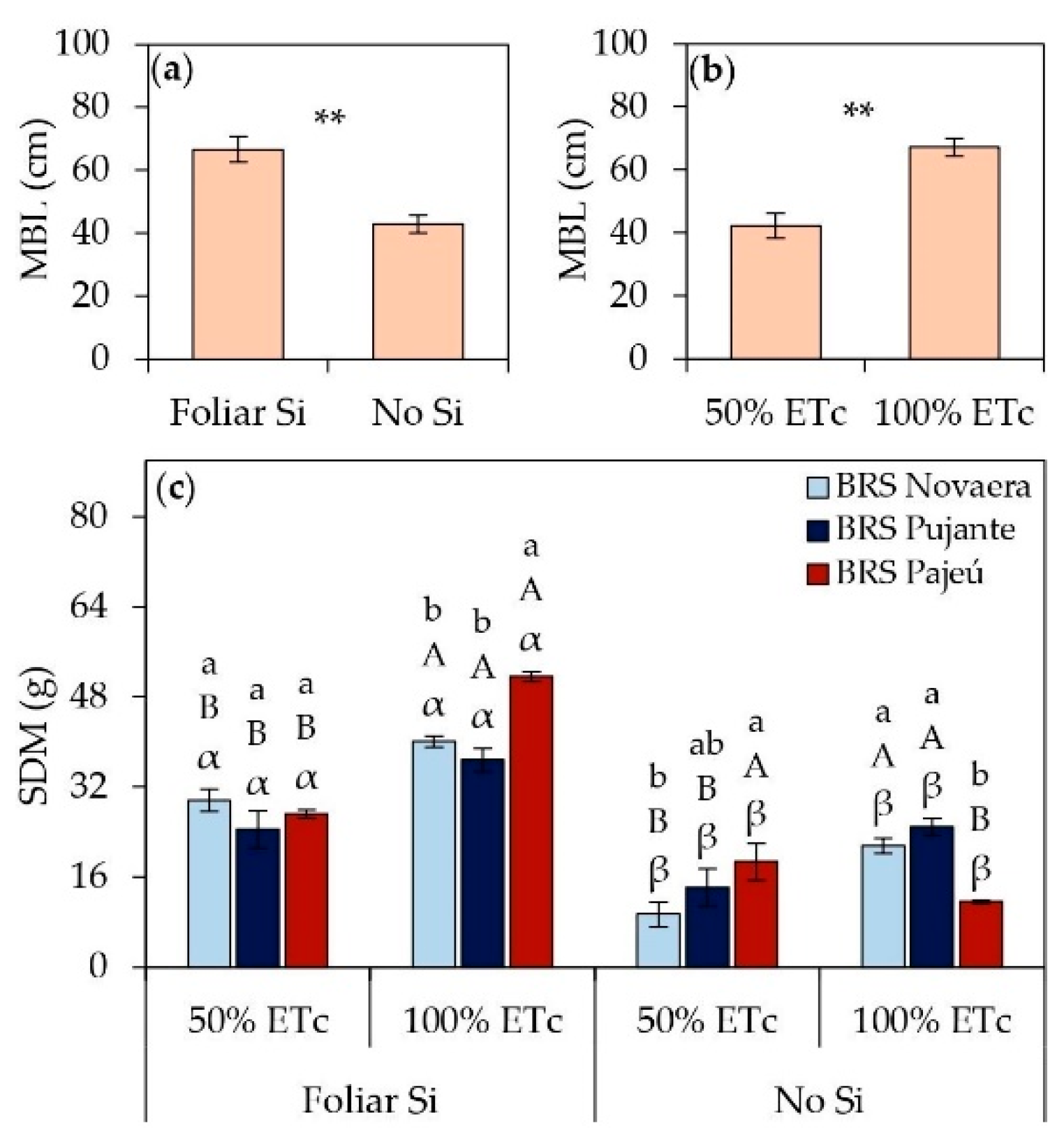

The nutritional, osmoregulatory, and antioxidant improvements promoted by silicon significantly enhanced cowpea vegetative growth, resulting in substantial increases in main branch length (

Figure 4a) and shoot biomass (

Figure 4c). Additionally, studies indicate that the benefits of Si may also be associated with increased photosynthetic activity, silica deposition in the leaf epidermis, strengthening of the plasma membrane, and reduced transpiration rate, all of which collectively enhance plant development [

31,

32,

33,

35,

36]. The notable increases in shoot dry mass, particularly under water deficit conditions (

Figure 4c), highlight silicon's ability to mitigate the negative effects of water restriction in cowpeas. These findings align with Silva et al. [

32], who reported that foliar silicon application in potassium silicate alleviates water stress and improves growth characteristics in cowpea cultivars.

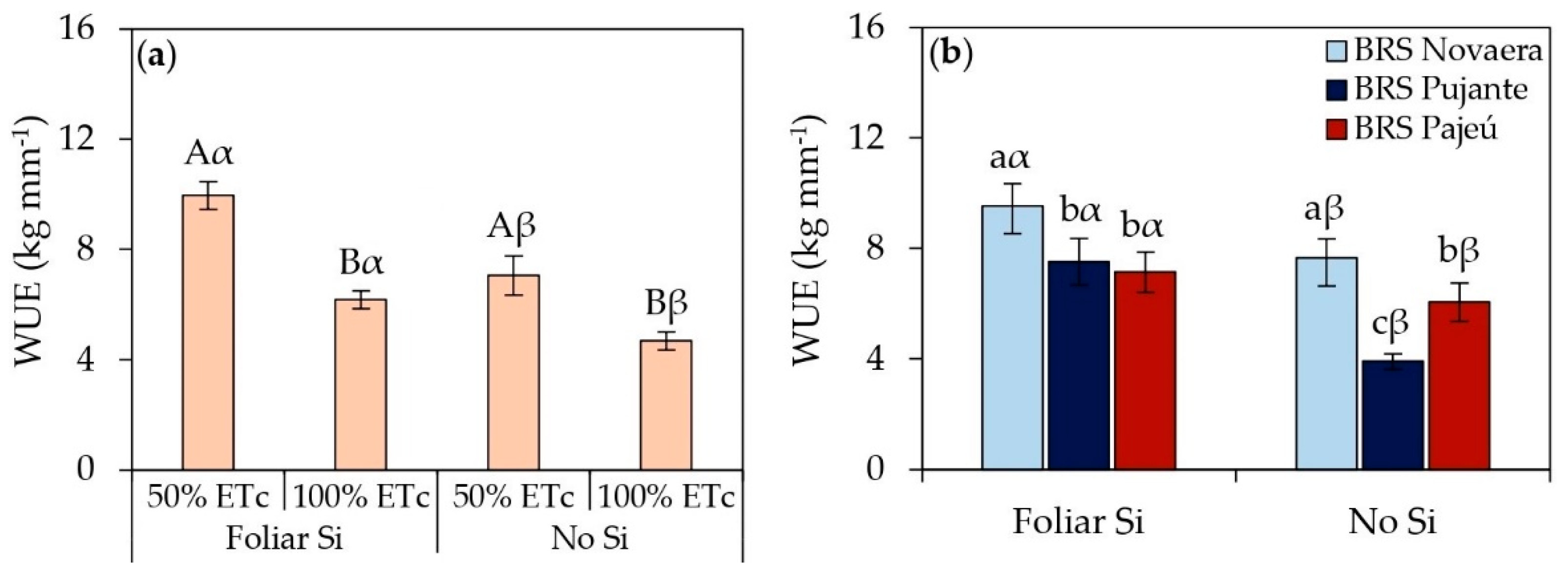

In addition to biochemical benefits and plant growth improvements, silicon application significantly enhanced the evaluated yield parameters, as demonstrated in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The increase in WUE in plants subjected to 50% of ETc and treated with silicon (

Figure 5a) highlights the role of this element in maintaining yield even under water restrictions. Additionally, the increase in WUE under full irrigation with silicon application (

Figure 5a) demonstrates that the benefits of this element are not limited to stress conditions but also contribute to more efficient water use under adequate moisture availability. The superior performance of the BRS Novaera cultivar across all evaluated conditions (

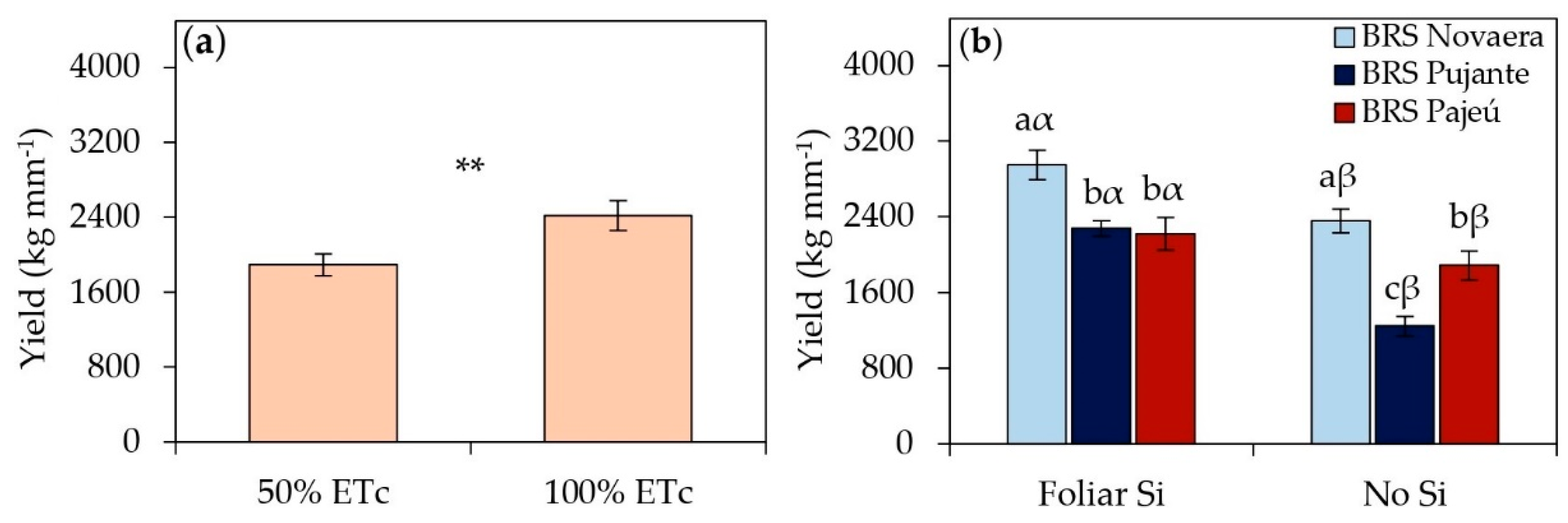

Figure 5b) reinforces the influence of genetic factors on water use efficiency, possibly associated with intrinsic traits that promote higher yield with lower water consumption.

Silicon application also minimized the effects of water deficit on pod production, with the BRS Novaera cultivar standing out for its superior performance under all evaluated conditions (

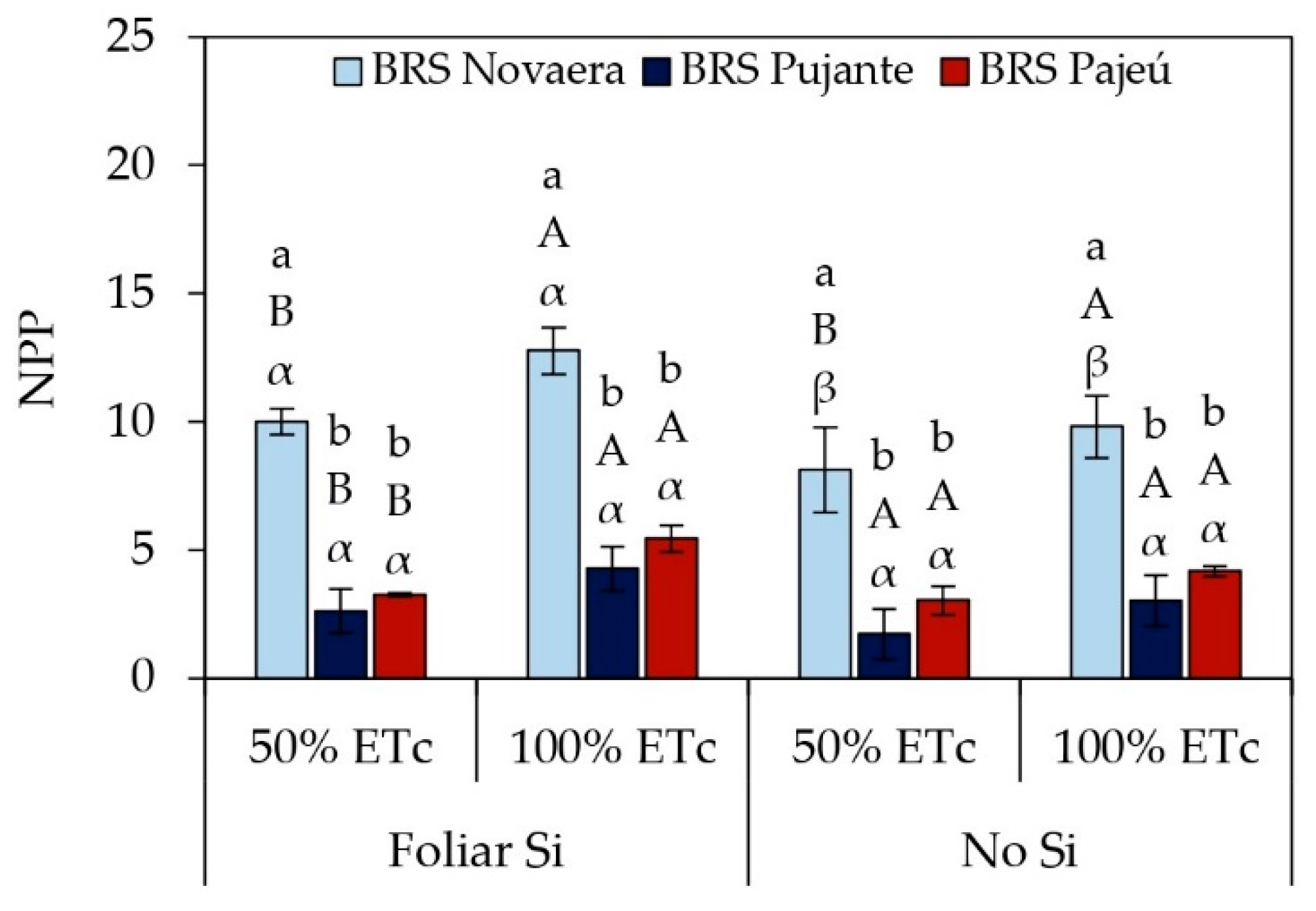

Figure 6). The increase in NPP promoted by silicon application under irrigation at 50% of ETc demonstrates this element's ability to mitigate the impacts of water deficiency, contributing to the maintenance of reproductive structure development even under adverse conditions. Furthermore, the increase in NPP under full irrigation indicates that silicon reduces the effects of water stress and maximizes yield potential when adequate water availability is ensured.

Regardless of the water regime, silicon application significantly increased yield in the evaluated cultivars (

Figure 7a). The BRS Novaera cultivar, which reached a yield of 2952 kg ha⁻¹ with silicon application (

Figure 7b), stood out for its high yield potential and strong responsiveness to silicon, establishing itself as a promising option for cultivation in semi-arid regions. Furthermore, the observed yield values far exceeded the national average for the crop, estimated at 542 kg ha⁻¹ in the 2023/2024 growing season [

5], reinforcing the feasibility of using silicon as a strategy to optimize cowpea agronomic performance, particularly in systems subject to water restrictions.

The efficiency of foliar application of silicic acid compared to soil application has been widely debated. According to Laane [

16], the foliar form can be highly efficient since silicates applied to the soil require large amounts to release monosilicic acid, the only form assimilable by plants. This process depends on factors such as pH, soil composition, and microbial activity, which can limit the immediate availability of silicon for root uptake. In contrast, Si supplied via spraying is already bioavailable, allowing for faster and more direct absorption by foliar tissues. However, according to the authors, the specific mechanism by which monosilicic acid penetrates the leaf epidermis and is redistributed within plant tissues is not yet fully elucidated. Further studies are needed to understand the factors regulating this absorption and subsequent translocation, particularly in different species and environmental conditions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Location, Treatments, and Statistical Design

A field experiment was conducted between September and December 2021 at the Center for Human and Agricultural Sciences of the State University of Paraíba, located in the municipality of Catolé do Rocha, PB, Brazil (6º 20' 38" S, 37º 44' 48" W, and altitude of 275 m). The climate of the region is classified as BSh-type, a hot semi-arid climate with summer rainfall [

37]. The climatic data recorded during the experiment is presented in

Figure 8.

The experiment was arranged in a split-plot design, with the plots corresponding to two irrigation depths (50% and 100% of crop evapotranspiration - ETc) and the subplots consisting of the combination of three cowpea cultivars (BRS Novaera, BRS Pujante, and BRS Pajeú) and the application or not of foliar silicon fertilization (with and without application). A randomized block design was adopted with four replications. The main plot consisted of six subplots spaced 0.5 m apart. Each subplot contained three planting rows, with 10 plants per row (spacing of 0.1 m between plants × 0.5 m between rows), totaling 30 plants per subplot.

Silicon solutions were prepared by dissolving silicic acid [Si(OH)₄] in water, resulting in a 10 mg Si L⁻¹ concentration. Three foliar applications were performed on the abaxial and adaxial leaf surfaces until runoff at 19, 35, and 42 days after sowing (DAS), as shown in

Figure 8.

4.2. Irrigation Management

The plants were irrigated daily with water from a well, which had the following characteristics: electrical conductivity = 1.01 dS m⁻¹; pH = 6.9; concentrations of K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, and SO₄²⁻ of 1.21, 2.5, 1.48, 6.45, 8.1, 2.75, and 0.18 mmolc L⁻¹, respectively; and sodium adsorption ratio = 4.57 (mmol L⁻¹)¹/². Irrigation was performed via a drip system using drip tapes with emitters spaced every 0.2 m and a flow rate of 1.6 L h⁻¹, operating at a service pressure of 0.1 MPa.

Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) was determined by multiplying reference evapotranspiration (ETo, mm d⁻¹) by crop coefficients (Kc), which varied according to the plant phenological stages. ETo was estimated based on Class 'A' pan evaporation, corrected using a coefficient of 0.75. The plants' consumptive water use (CU) was considered, assuming 100% of the wetted area (P). To determine the daily net irrigation depth (DLD), the equation DLD = CU × P/100 (mm d⁻¹) was used. The applied irrigation depths corresponded to 50% and 100% of the DLD, with adjustments based on irrigation time. The irrigation depths applied at each phenological stage of the plants are presented in

Table 3, allowing for an assessment of water management over the crop development cycle.

4.3. Soil Characteristics and Preparation of the Experimental Area

The soil in the experimental area was classified as an Entisol (Fluvent) [

38], with a sandy clay loam texture, and had the following physical properties: 831.5, 100.0, and 68.5 g kg⁻¹ of sand, silt, and clay, respectively; soil bulk density = 1.53 g cm⁻³; particle density = 2.61 g cm⁻³; total porosity = 0.42 m³ m⁻³; flocculation degree = 1,000 kg dm⁻³; and moisture content at tensions of -0.01, -0.03, and -1.50 MPa of 65, 49, and 28 g kg⁻¹, respectively. Regarding fertility, the soil had the following characteristics: pH = 6.0; P = 16.63 mg dm⁻³; concentrations of K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Na⁺ of 0.08, 1.09, 1.12, and 0.05 cmol

c dm⁻³, respectively; sum of exchangeable bases = 2.34 cmol

c dm⁻³; H⁺ + Al³⁺ = 1.24 cmol

c dm⁻³; Al³⁺ = 0 cmol

c dm⁻³; cation exchange capacity (CEC) = 3.58 cmol

c dm⁻³; base saturation (V) = 65.36%; and organic matter content = 13.58 g kg⁻¹.

Soil preparation consisted of plowing to a depth of 50 cm. The fertilization at the sowing furrow and in top-dressing followed the recommendations of Cavalcanti [

39]. Before sowing, the soil was irrigated until it reached field capacity moisture. Subsequently, sowing was carried out using two seeds per hole at a depth of 3 cm. Five days after seedling emergence, thinning was performed, leaving one plant per hole.

4.4. Experimental Analysis

For foliar nutrient analysis, four leaves from the middle section of the three central plants in each subplot were collected 45 days after sowing (DAS). After being washed with distilled water, the leaves were dried in a forced-air circulation oven at 60 °C until reaching a constant mass, ground in a stainless steel knife mill (Willey-type), and stored in hermetically sealed containers for the determination of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and calcium (Ca) concentrations, following the methodologies proposed by Silva [

40].

Nitrogen (N) content was determined using the Kjeldahl method (dry digestion); phosphorus content was measured by molybdenum blue spectrophotometry; potassium (K) content was determined by flame photometry; and calcium (Ca) content was analyzed using atomic absorption spectrometry at a wavelength of 422.7 nm.

At 45 DAS, the main stem length (MSL) was also analyzed, measured from the base of the stem to the base of the youngest leaf. During the same period, the shoot of three plants per subplot was collected, placed in paper bags, and dried in a forced-air circulation oven at 65 °C. After reaching a constant mass, the material was weighed using a precision balance (0.0001 g) and shoot dry mass (SDM) was determined.

At 45 DAS, the youngest fully expanded leaves from three plants per subplot were also collected for the analysis of proline content and the activities of antioxidant enzymes: superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX). The plant material was collected in the morning, stored in ice-filled containers, and immediately transported to the laboratory, where it was kept in a freezer until analysis.

Proline concentration was determined using the method of Bates et al. [

41], with absorbance measured at 520 nm. The activities of SOD, CAT, and APX enzymes were measured using the methods of Beauchamp and Fridovich [

42], Sudhakar et al. [

43], and Nakano and Asada [

44], respectively.

At the end of the cycle, between 56 and 62 DAS, pod harvesting was carried out on the remaining plants in the subplot, recording the number of pods per plant (NPP) and grain yield (kg ha⁻¹). Additionally, water use efficiency (WUE) was evaluated based on the ratio between grain yield (kg ha⁻¹) and the irrigation depth (mm), as described by Souza et al. [

45].

4.5. Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were subjected to normality and homoscedasticity tests using the Shapiro-Wilk method (p < 0.05) and Bartlett test (p < 0.05), respectively. Subsequently, they were analyzed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the F-test (p < 0.05). Mean comparisons were performed using the Tukey test (p < 0.05).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.G.d.Q, E.F.d.M. and A.S.d.M.; methodology, L.L.G.d.Q, C.d.S.S., R.F.F., V.C.d.S.S., J.P.C.D., R.S.d.A., J.P.M.M.P., S.S.R., G.F.D., P.d.S.C.F., E.F.d.M., and A.S.d.M.; validation, R.F.P., E.F.d.M., A.S.d.M., F.d.O.M., L.K.S.L., and A.d.S.A.; formal analysis, L.L.G.d.Q, C.d.S.S., E.F.d.M., A.S.d.M., and R.F.P.X.X.; investigation, L.L.G.d.Q, C.d.S.S., R.F.P, V.C.d.S.S., J.P.C.D., A.d.S.A., J.P.M.M.P., S.S.R, L.K.S.L., K.T.A.A., F.d.O.M., P.d.S.C.F., R.S.d.A. and G.F.D.; resources, E.F.d.M. and A.S.d.M.; data curation, C.d.S.S., R.F.P, E.F.M., A.S.d.M.; X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.G.d.Q, R.F.P., C.d.S.S. and E.F.M.; writing—review and editing, A.S.d.M., V.C.d.S.S., J.P.C.D., F.d.O.M., L.K.S.L., A.d.S.A., K.T.A.A., J.P.M.M.P., S.S.R, P.d.S.C.F., R.S.d.A. and G.F.D.; supervision, E.F.d.M. and A.S.d.M.; funding acquisition, E.F.d.M. and A.S.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Foliar contents of N (a, d), P (b, e), Ca (c, f), and K (g) in cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application. ** and * indicate significance at p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars, and uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths, according to Tukey's test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 1.

Foliar contents of N (a, d), P (b, e), Ca (c, f), and K (g) in cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application. ** and * indicate significance at p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars, and uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths, according to Tukey's test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Effect of the silicon × cowpea cultivar interaction on free proline content in leaves. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars, and uppercase letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Effect of the silicon × cowpea cultivar interaction on free proline content in leaves. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars, and uppercase letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

Activities of the enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) (a, b), catalase (CAT) (c, d), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) (e) in cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application. ** and * indicate significance at p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to Tukey's test; bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 3.

Activities of the enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) (a, b), catalase (CAT) (c, d), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) (e) in cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application. ** and * indicate significance at p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to Tukey's test; bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Main branch length (MBL) (a, b) and shoot dry mass (SDM) (c) of cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application. ** indicates significance at p < 0.01, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Main branch length (MBL) (a, b) and shoot dry mass (SDM) (c) of cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application. ** indicates significance at p < 0.01, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 5.

Breakdown of the irrigation × silicon × cultivar interaction on the number of pods per plant (NPP) in cowpea. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 5.

Breakdown of the irrigation × silicon × cultivar interaction on the number of pods per plant (NPP) in cowpea. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 6.

Effect of the irrigation × silicon × cultivar interaction on the number of pods per plant (NPP) in cowpea. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 6.

Effect of the irrigation × silicon × cultivar interaction on the number of pods per plant (NPP) in cowpea. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars; uppercase letters indicate differences among irrigation depths; and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 7.

(a) Grain yield of cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and (b) the effect of the silicon × cultivar interaction on yield. ** indicates significance at p < 0.01, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars, and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 7.

(a) Grain yield of cowpea cultivars subjected to different irrigation depths and (b) the effect of the silicon × cultivar interaction on yield. ** indicates significance at p < 0.01, according to the F-test. Lowercase letters indicate differences among cultivars, and Greek letters indicate differences between the presence and absence of foliar silicon application, according to the Tukey test. Bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of the weather conditions recorded in the experimental area during the experiment and the time representation of the main experimental events.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of the weather conditions recorded in the experimental area during the experiment and the time representation of the main experimental events.

Table 1.

Summary of the analysis variance for the leaf contents of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and calcium (Ca), free proline content (Proline), and the activity of the enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in cowpea cultivars under different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application.

Table 1.

Summary of the analysis variance for the leaf contents of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and calcium (Ca), free proline content (Proline), and the activity of the enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in cowpea cultivars under different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application.

| Source of variation |

DF |

Mean Square |

| N |

P |

K |

Ca |

Proline |

SOD |

CAT |

APX |

| Block |

3 |

24.32ns

|

0.078ns

|

47.91ns

|

23.47ns

|

89960.80ns

|

6.24ns

|

2198.51ns

|

0.09ns

|

| Irrigation depth (ID) |

1 |

6298.41** |

17.62** |

484.75* |

291.60* |

845365.35ns

|

7020.90** |

5257.19ns

|

0.05ns

|

| Error A |

3 |

34.46 |

0.11 |

47.55 |

15.63 |

88566.39 |

24.47 |

701.05 |

0.09 |

| Silicon (Si) |

1 |

1913.19** |

10.59** |

24.39ns

|

65.26* |

2205125.63** |

290.96* |

12233.66** |

5.46** |

| Cultivar (Cul) |

2 |

1241.71** |

3.14** |

15.28ns

|

22.004ns

|

1078779.33** |

40.04ns

|

4913.51* |

0.79** |

| ID x Si |

1 |

0.02ns

|

0.34ns

|

78.23ns

|

23.78ns

|

316418.53ns

|

0.45ns

|

1029.15ns

|

1.72** |

| ID x Cul |

2 |

304.26** |

2.47** |

64.44ns

|

5.91ns

|

1043897.35** |

79.93ns

|

1503.52ns

|

0.62** |

| Si x Cul |

2 |

33.94ns

|

0.60ns

|

6.08ns

|

1.75ns

|

58459.35ns

|

7.11ns

|

1176.37ns

|

0.08ns

|

| ID x Si x Cul |

2 |

29.72ns

|

0.25ns

|

14.96ns

|

1.51ns

|

247645.19ns

|

55.12ns

|

622.71ns

|

0.89** |

| Error B |

30 |

1249.33 |

0.23 |

47.31 |

12.91 |

76424.02 |

60.15 |

1193.64 |

0.07 |

| CV (A) (%) |

- |

8.76 |

11.49 |

32.61 |

26.13 |

41.47 |

5.85 |

12.79 |

24.71 |

| CV (B) (%) |

- |

9.63 |

16.57 |

32.53 |

23.75 |

38.52 |

9.17 |

16.68 |

22.49 |

Table 2.

Summary of variance analysis for main branch length (MBL), shoot dry mass (SDM), water use efficiency (WUE), number of pods per plant (NPP), and grain yield (Yield) in cowpea cultivars under different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application.

Table 2.

Summary of variance analysis for main branch length (MBL), shoot dry mass (SDM), water use efficiency (WUE), number of pods per plant (NPP), and grain yield (Yield) in cowpea cultivars under different irrigation depths and foliar silicon application.

| Source of variation |

DF |

Mean square |

| MBL |

SDM |

WUE |

NPP |

Yield |

| Block |

3 |

43.05ns

|

61.51ns

|

0.98ns

|

1.31ns

|

42760.63ns

|

| Irrigation depth (ID) |

1 |

7413.99** |

1318.69** |

113.65** |

38.10** |

3298685.88* |

| Error A |

3 |

75.50 |

4.75 |

2.47 |

0.88 |

190185.27 |

| Silicon (Si) |

1 |

6746.20** |

3984.53** |

57.64** |

23.98** |

5140835.70** |

| Cultivar (Cul) |

2 |

15.45ns

|

25.29ns

|

34.65** |

246.48** |

3311895.22** |

| ID x Si |

1 |

225.55ns

|

328.49**

|

5.85* |

2.02ns

|

1459.71ns

|

| ID x Cul |

2 |

48.63ns

|

10.21ns

|

1.86ns

|

0.60ns

|

58972.55ns

|

| Si x Cul |

2 |

216.11ns

|

175.64** |

6.64** |

3.13ns

|

497508.97** |

| ID x Si x Cul |

2 |

297.24ns

|

335.98** |

2.14ns

|

0.16ns

|

52283.23ns

|

| Error B |

30 |

133.05 |

13.85 |

0.88 |

1.04 |

65291.85 |

| CV (A) (%) |

- |

15.85 |

8.44 |

22.57 |

16.57 |

20.22 |

| CV (B) (%) |

- |

21.04 |

14.40 |

13.52 |

17.95 |

11.85 |

Table 3.

Irrigation depths applied at each phenological stage of cowpea cultivars.

Table 3.

Irrigation depths applied at each phenological stage of cowpea cultivars.

| Stages |

Substages |

Irrigation depths (mm stage-1) |

| 50% ETc |

100% ETc |

| Vegetative |

V0 |

7.79 |

15.57 |

| V1 |

4.61 |

9.22 |

| V2 |

9.57 |

19.13 |

| V3 |

11.84 |

23.68 |

| V4 |

9.98 |

19.97 |

| V5 |

14.14 |

28.28 |

| V6 |

18.11 |

36.22 |

| V7 |

17.53 |

35.07 |

| V8 |

17.98 |

35.95 |

| V9 |

12.54 |

25.08 |

| Reproductive |

R1 |

15.83 |

31.66 |

| R2 |

16.84 |

33.69 |

| R3 |

19.42 |

38.84 |

| R4 |

18.56 |

37.13 |

| R5 |

27.96 |

55.92 |

| Total |

222.69 |

445.39 |