1. Introduction

The accelerating global demand for food, fiber, and bioenergy has intensified the expansion of agricultural production and trade, especially in emerging economies across Latin America. This region has consolidated its position as the world’s leading food exporter, largely due to sustained gains in productivity, technological innovation, and land use expansion [

1,

2]. Within this context, Brazil emerges as a dominant actor, underpinned by extensive reserves of arable land, ample freshwater resources, and a diverse range of biomes conducive to agricultural intensification [

3,

4]. Among these, soybean (

Glycine max L.) has become the most prominent crop in Brazil, both in terms of cultivated area and total production, reflecting its strategic economic role in both domestic markets and international trade [

5,

6]. Its rapid expansion has been supported by decades of public-sector incentives, sustained investment in agronomic research, genetic improvement, and the development of logistics and export infrastructure [

7]. Coupled with favorable soil and climatic conditions—particularly in the Cerrado and Southern regions—these factors have positioned Brazil as the world’s leading soybean producer. In the 2021/2022 growing season, national output reached approximately 168.3 million tons, cultivated over 47.6 million hectares, further consolidating Brazil’s influence on global food and biofuel supply chains [

7,

8,

9].

Due to substantial advances achieved through decades of conventional breeding and the integration of omics-based approaches—such as genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics—soybean has successfully expanded into diverse environments and become one of the most productive and economically important crops worldwide [

10,

11,

12,

13]. However, climate change now represents a major threat to the stability of global soybean production systems. Increasing air temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and a higher frequency of extreme weather events—such as droughts, floods, and heatwaves—pose significant risks to soybean growth and yield potential across a wide range of agroecosystems [

14,

15,

16].

To overcome this threat, the use of a chitosan-based biostimulant emerges as a promising alternative for enhancing soybean productivity through improved physiological resilience under field-relevant drought scenarios. Chitosan has demonstrated considerable efficacy in enhancing drought tolerance in a variety of plant systems—including apple, sunflower, wheat, barley, Catharanthus roseus, maize, rice, and soybean—by engaging multiple physiological mechanisms [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. These mechanisms include upregulation of antioxidant defense activities, increased endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) production, improved gas exchange parameters, and elevated accumulation of stress-protective metabolites, all of which contribute to enhanced cellular resilience under water-limited conditions.

A growing body of empirical evidence supports the positive role of chitosan in improving key physiological traits across diverse crops. For instance, application of chitosan has been shown to enhance vegetative growth, nutrient uptake efficiency, chlorophyll concentration, chlorophyll stability index, and drought tolerance in species such as cowpea, potato, common bean, sugarcane, basil, milk thistle, lettuce, and soybean [

16,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Beyond its intrinsic biological activity, chitosan offers substantial versatility due to its capacity for chemical and enzymatic modification. Under acidic conditions, its cationic nature enables electrostatic interactions with anionic molecules, such as components of pyroligneous extract in FF-BR formulation (patent number US 9,868,677 B2) [

27,

28]. This interaction facilitates the development of synergistic formulations with significant agricultural utility. Of particular interest is the formulation known as FF-BR, developed by [

27], which integrates chitosan with pyroligneous extract. This compound has been shown to form a vapor-permeable protective film capable of attenuating UV-B and UV-C radiation, suppressing fungal pathogens, and activating systemic resistance in plants [

27,

28]. Despite this extensive knowledge on chitosan's effects, there remains a significant gap in understanding the physiological mechanisms and plant responses when grown under field conditions, and subjected to water deficit stress, particularly concerning formulations combining chitosan with pyroligneous acid, such as FF-BR. While individual components like chitosan have been studied, the synergistic effects and specific physiological responses elicited by such combined formulations under water deficit conditions are not well-documented in studies conducted in realistic field conditions. This lack of information is especially pertinent for soybean cultivation, where understanding the interaction between such biostimulant formulations and plant physiological responses under erratic rainfall distribution is crucial for developing effective agronomic practices. Therefore, further research is essential to elucidate the mechanisms by which FF-BR influences plant physiology during water deficit, aiming to optimize its application for improved drought tolerance in soybean and potentially other crops.

Building upon the original findings of [

16], who first reported FF-BR’s ability to modulate the soybean stomatal closure, carbon assimilate rate and intrinsic water use efficiency, besides the enhanced grain yield, the present research phase was designed to deepen the understanding of FF-BR’s effects on soybean water use modulation and its consequences on carbon fixation, and their impacts on grain yield components. Specifically, this study aimed to validate prior findings and deepen the understanding of FF-BR’s physiological effects under both controlled field conditions and commercial farming environments. Field experiments allowed for precise measurements of gas exchange and yield-related traits across soybean cultivars with varying maturity groups. Simultaneously, on-farm trials evaluated the performance of FF-BR under real-world management practices, which reflected the diverse edaphoclimatic and operational conditions prevalent in Brazilian soybean production. By integrating physiological and agronomic assessments across experimental and commercial setting, these efforts sought to confirm the formulation’s consistency and clarify its mode of action, supporting its broader use as a drought resilience technology. These efforts contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting FF-BR’s potential to enhance drought resilience, optimize water use, and improve productivity in modern soybean production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Invention Description

The present invention, patent number US 9,868,677 B2, Jan, 16, 2018 falls into the context of green chemistry and generically relates to a fertilizing and phytoprotective formulation and, in particular embodiment, to a film forming formulation that induces resistance to plants [

27]. The respective formulation, when applied to plants and/or fruits, results in the formation of a film on the surface of the material, which has a characteristic of photoprotection against UV-B and UV-C radiations, resistance kept in water, even after high hygroscopicity, greater stability at high ambient temperatures, formation of desired porosity and surface homogeneity.

2.2. Sites and General Climatic Conditions of Conducting the Experiments

Field experiments were carried out over two consecutive growing seasons (2023/2024 and 2024/2025) in the west-central region of Paraná State, Brazil—a prominent area for integrated grain production systems. This region plays a key role in national soybean output, where soybean is typically sown in mid-September and harvested by mid-February. Following the soybean cycle, many farmers adopt an off-season crop, commonly planting maize or wheat. This rotation is particularly strategic for farmers who initiate soybean sowing later in the season, under a no-tillage system, as it helps preserve soil moisture through crop residue cover from the previous harvest, while also optimizing land use and profitability across both cropping cycles.

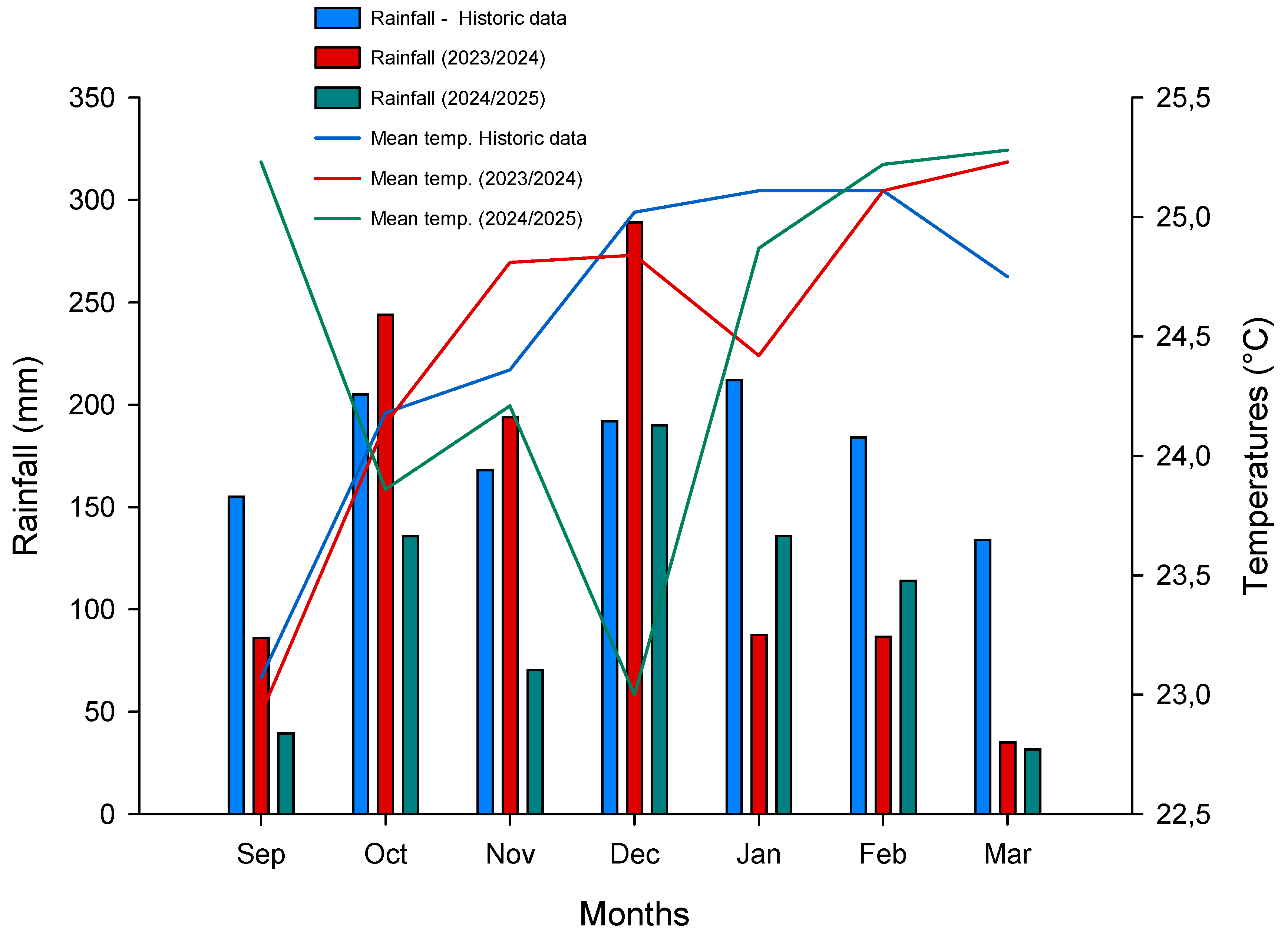

The 2023/2024 experiment was conducted at a private experimental station operated by Agroensaio Pesquisa e Consultoria Agro Ltda., located 5 km from the urban center of Campo Mourão, PR (latitude 23° 98' 82” S, longitude 52° 43' 64” W; altitude 630 m). In the following season (2024/2025), the study was replicated on São Domingos Farm, situated 23 km from Campo Mourão, PR (latitude 24° 35' 9” S, longitude 52° 28' 14.8” W; altitude 650 m). Both experimental sites are located in regions of high agricultural productivity, particularly under no-tillage and crop rotation systems involving soybean, maize, wheat, and oats. Historically, soybean crops in this region have been exposed to erratic rainfall distribution. During the 2024/2025 growing season, this resulted in an estimated 13% reduction in grain yield due to irregular precipitation and the occurrence of heatwaves. (Communication by Deral/Seab, PR).

The region’s climate is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa) under the Köppen–Geiger’s climate classification system [

29], characterized by hot, humid summers and mild winters. Rainfall is concentrated between October and March, with a well-defined dry season from April to September. Historical climate data, including average monthly precipitation and air temperature, were obtained from the Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia (INMET) and are presented in

Figure 1. Average monthly precipitation and temperatures during the experiments was recorded by an automatic weather station located 350 meters from the experimental site.

2.3. Soil Characteristics and Area Usage History in the Experimental Sites

At the 2023/2024 site, the soil was classified as Latossolo Vermelho distroférrico according to the Brazilian Soil Classification System [

30], which corresponds to a Rhodic Hapludox in the USDA Soil Taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff, 2010). Prior to the establishment of the experiment, composite soil samples from the 0–20 cm layer were collected and analyzed, revealing the following properties: clay content of 580 g kg

−1, organic carbon concentration of 27.2 g dm

−3, pH of 5.5 (CaCl

2), available phosphorus (P-Mehlich) of 27.7 mg dm

−3, and exchangeable potassium, calcium, and magnesium concentrations of 0.76, 6.41, and 3.03 cmolc dm

−3, respectively. The base saturation (V%) was 71%, indicative of high fertility.

This experimental area had been managed under a no-tillage system for five consecutive years, with a typical crop rotation that included wheat or oat during the winter, followed by soybean as the main summer crop, and maize as off-season crop (second growth season). The 2023/2024 trial was implemented in adjacent plots to ongoing studies, differing only in the soybean cultivar used. The selected cultivar was Soytech ST 641 I2X, belonging to the 6.4 Relative Maturity Group (RMG), a genotype commonly cultivated in the region. The experimental treatments are detailed in

Table 1.

At the 2024/2025 site, the soil was similarly classified as a Latossolo Vermelho distrófico (Dystrophic Red Latosol), also corresponding to a Rhodic Hapludox in the USDA classification. These soils are highly weathered, deep, and exhibit a well-developed structure, predominantly clayey in texture with clay content frequently exceeding 600 g kg

−1. The mineralogical composition of the clay fraction is dominated by kaolinite and gibbsite, with lesser quantities of hematite and goethite [

31], consistent with the advanced weathering stage typical of tropical Oxisols [

30].

Initial soil characterization at this site, also based on 0–20 cm composite samples, revealed similar properties to the 2023/2024 site, confirming high consistency between locations: clay content of 593 g kg−1, organic carbon concentration of 29.1 g dm−3, pH (CaCl2) of 5.64, available phosphorus of 6.54 mg dm−3, and exchangeable K, Ca, and Mg levels of 0.33, 6.27, and 2.40 cmolc dm−3, respectively, with a base saturation of 67%.

2.4. Experiments Design in the 2023/2024, FF-BR Applications, Gas Exchange Analyzes and Yield Components Measurements

In the 2023/2024 growing season, the field experiment was conducted using a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replications. Each experimental unit received two foliar applications of the bioactivator FF-BR, applied at an intervals of seventeen days, during the R1–R2 reproductive stages, a critical window in soybean development marked by early flowering and initial pod set. The experimental plots measured 3.0 × 9.0 meters (27 m2), and were arranged with 1-meter buffer zones to facilitate in-plot sampling, minimize treatment interference, and ensure effective mechanical harvesting at physiological maturity.

The indeterminate-growth soybean cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X was sowed on November 10, 2023. A six-row no-till seed-cum-fertilizer drill was used, but the ridger mechanism was removed to avoid potential soil compaction issues. The seeds were sown at a density of 16 seeds per meter, with a row spacing of 0.50 meters, using only the cutting disc of the seed metering. The soil was fertilized with 150 kg ha−1 of a 02-23-23 fertilizer.

FF-BR applications were performed using a pressurized CO

2 backpack sprayer, calibrated to deliver a spray volume of 200 L ha

−1. The operating pressure was maintained at approximately 2.8 bar (40 psi), consistent with standard agronomic practices for foliar application in soybean. The sprayer was equipped with flat-fan nozzles producing medium-sized droplets to ensure adequate canopy coverage and minimize drift under field conditions. This configuration ensured uniform and efficient application of the biostimulant across all treatment plots (

Figure 2).

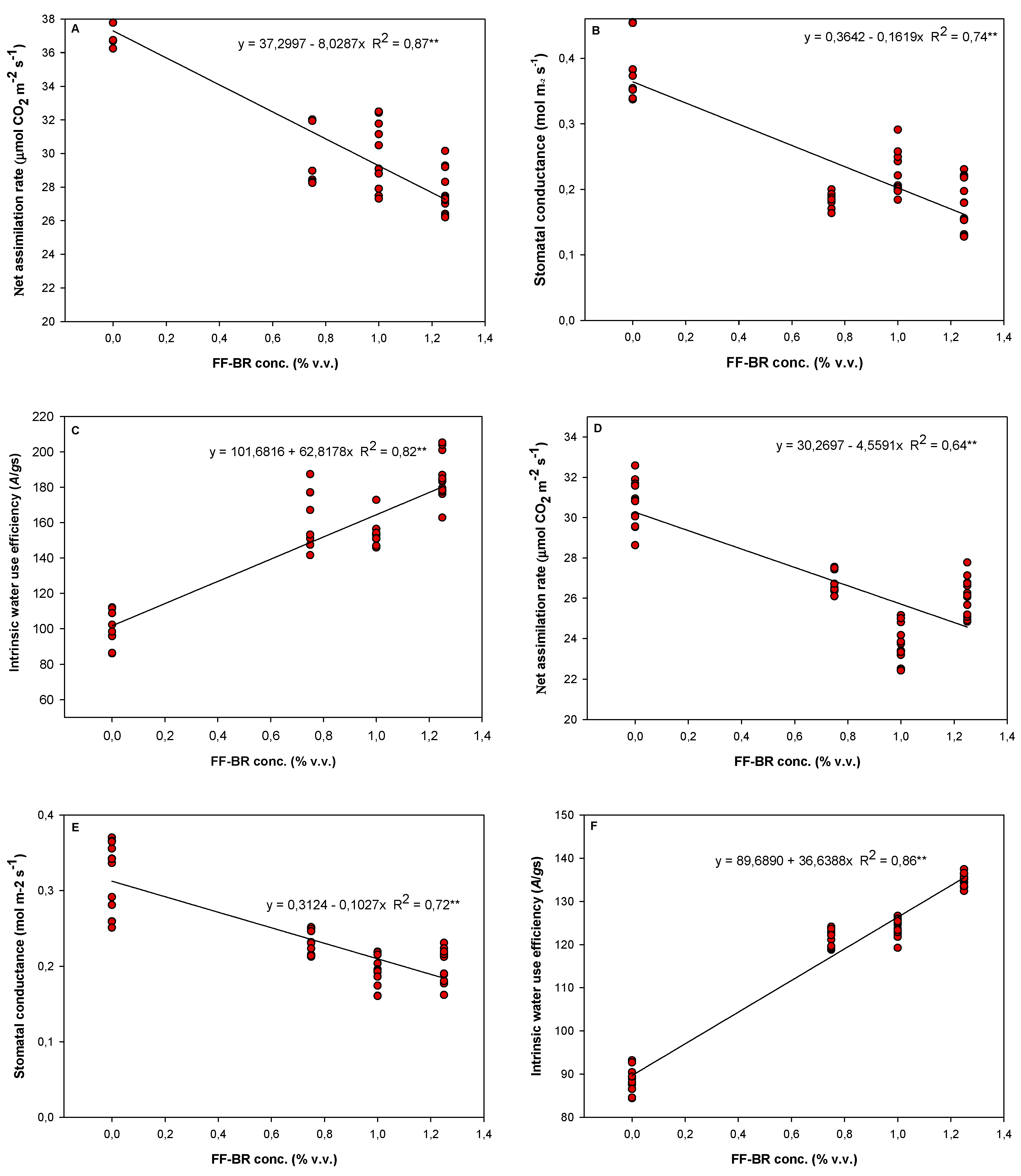

The gas exchange analysis was conducted at six and nine days after the second foliar spraying. The choice to start gas exchange analysis after the second application was made to ensure that all plant defense mechanisms were fully activated by the foliar spraying of FF-BR. Chitosan elicits a phasic plant defense response—with early gene activation (e.g., PAL, chitinase, peroxidase) occurring within minutes (e.g., 10 min), followed by enzyme activity changes (ROS, MAPKs) and secondary metabolite accumulation within hours to days [

32]. However, more sustained physiological and biochemical changes, including those that affect gas exchange parameters, are typically observed after repeated applications over several days [

33,

34,

35]. By the second application, which was followed by the gas exchange analysis after six and nine days, it was expected that these cumulative effects would be fully realized, providing a more accurate measure of the plant’s physiological responses and ensuring that the analysis captured the maximum impact of the chitosan treatment.

Gas exchange analyses were conducted on two plants per plot, located in the central region of each plot. Measurements were taken on the fourth leaves (central leaflet) from the top of soybean plants at two phenological stages: R2-R3 (beginning pod). A portable open-system gas exchange analyzer (LI-6400xt, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) programmed to provide an artificial photosynthetic photon flux (PPF) of 1,100 µmol m-2 s-1 and equipped with a CO2 injector system (6400-01) to maintain a constant internal CO2 concentration of 430 µmol mol-1 within the measurement chamber, was used for these measurements. A CO2 cartridge provided a controlled source of CO2, allowing for precise regulation of the CO2 partial pressure (Ca) entering the cuvette. Measurements were taken between 8:30 and 10:30 AM to capture a wider range of light and temperature conditions, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the plants' photosynthetic performance. Conversely, to ensure similar environmental conditions within each randomized block, gas exchange measurements were conducted within approximately 30 minutes for each block. The intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUE) was calculated by the ratio between the net assimilation of CO2 and the stomatal conductance (A/gs).

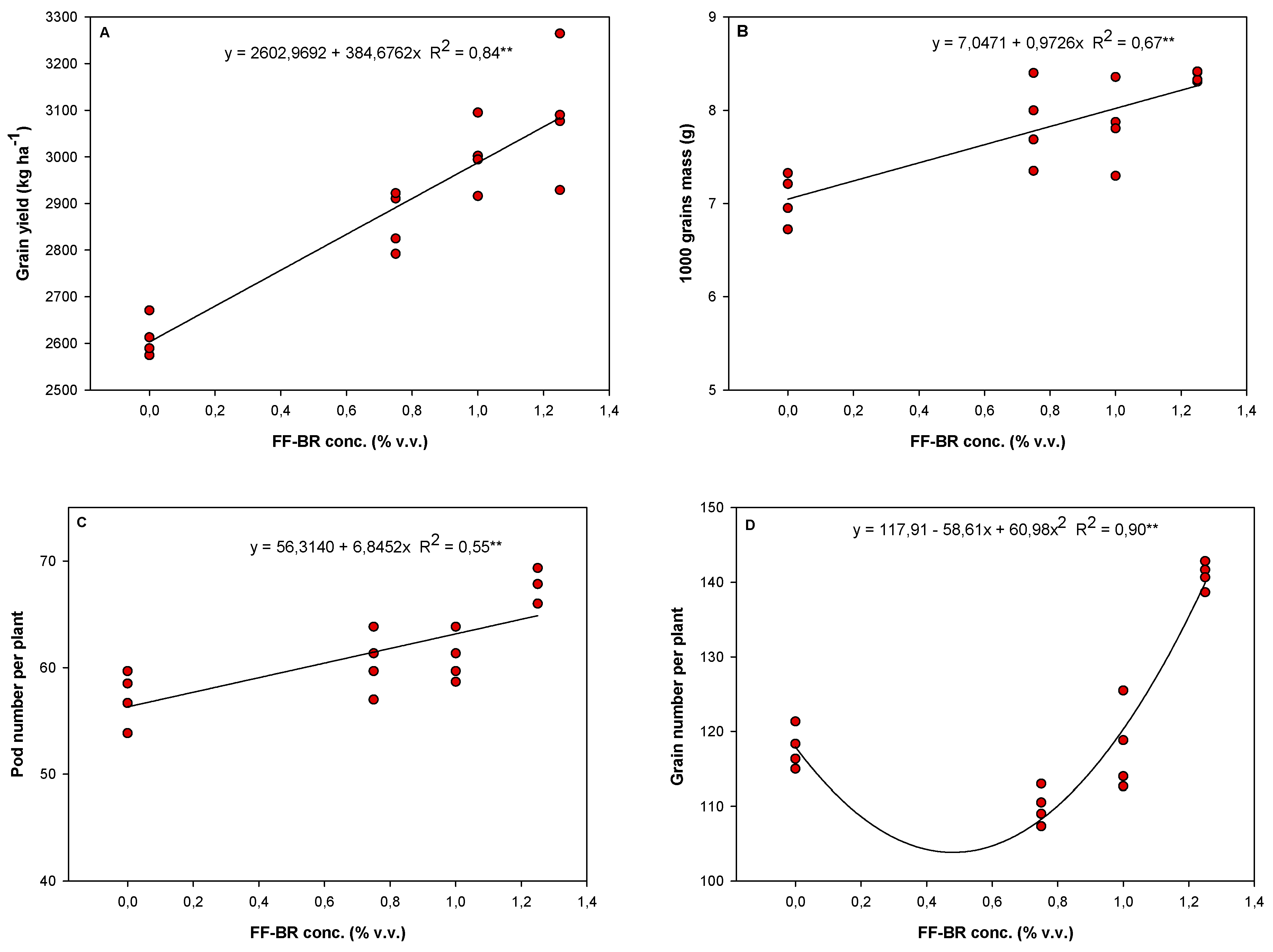

At maturity, each experimental unit was harvested, and the samples were processed and weighed to obtain the grain yield (GY) at 13% humidity. To assess plant architecture and reproductive traits, six representative plants were randomly selected from each plot, totalizing 24 plants per treatment. The 1000-grain weight, pods per plant, grains per plant, and grain yield were determined.

2.5. On Farm Trial Design (2024/2025), FF-BR Applications, Carbon Isotope Fractionation Analysis, and Yield Components Measurements

The indeterminate-growth soybean cultivar Neogen 610 IPRO was sowed on September 30, 2024. A no-till seed-cum-fertilizer drill was used, but the ridger mechanism was removed to avoid potential compaction issues. The seeds were sown at a density of 15 seeds per meter, with a row spacing of 0.45 meters, using only the cutting disc of the seed metering. The soil was fertilized with 150 kg ha−1 of a 02-23-23 fertilizer.

For this growing season, the experiment was established under on-farm conditions using a completely randomized design across three treatment groups: (i) a control (no FF-BR), (ii) three sequential FF-BR applications, and (iii) four sequential FF-BR applications. Treatments started at the R1–R2 growth stages, with subsequent applications made at 18-day intervals. Each treatment was applied to plots comprising three hectares, providing a commercial-scale evaluation of treatment effects. Adjacent to experiment area, approximately 350 hectares of commercial soybean cultivation was grown and managed simultaneously exactly as such experimental area. A fixed concentration of 1.0% (v:v) FF-BR was used for all applications across treatments.

Biostimulant treatments were applied using the farm's standard application system, consisting of a tractor-mounted boom sprayer, calibrated to dispense a spray volume of 200 L ha−1. Applications were performed at an operational pressure of approximately 3.5 bar (50 psi), using standard flat-fan nozzles that produced medium to coarse droplets. This configuration reflects common practices in commercial soybean production and was selected to ensure compatibility with regional agronomic standards and routine farm operations.

The carbon isotope composition (δ13C) of soybean grains was analyzed as an integrative proxy for intrinsic water use efficiency (WUE). Grain samples were collected at the R8 phenological stage and analyzed at the Stable Isotopes Center of Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Brazil, using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). For sampling, seven 1 m2-equivalent areas were randomly selected within each plot. All plants within each selected area were harvested to determine yield components, and representative grain subsamples from these plants were ground and used for δ13C analysis.

Soybean grains were oven-dried at 50 °C for 48 hours and subsequently homogenized in a cryogenic mill (Geno/Grinder 2010—SPEX SamplePrep, USA) with liquid nitrogen at −196 °C. An aliquot of 50 to 70 μg from each sample was weighed into a tin capsule using a microbalance with 1 μg resolution (XP6—Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). Homogenization was performed to ensure the representativeness of the small sample size. The capsules were analyzed using a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry (CF-IRMS) system. This system comprised an IRMS (Delta V Advantage, Thermo Scientific, Germany) connected to an elemental analyzer (Flash 2000, Thermo Scientific, Germany) via a gas interface (ConFlo IV, Thermo Scientific, Germany). The CF-IRMS measured the carbon isotope ratio (R =

13C/

12C), and results were expressed as the relative difference in isotopic ratio (δ

13C), in milliurey (mUr), with respect to the V-PDB standard, following Brand and [

35] and [

35]: δ

13C = [(R_sample / R_VPDB) − 1]. The standard uncertainty of the CF-IRMS was ±0.15 mUr, and results were normalized using the IAEA-NBS-22 standard. Carbon isotope discrimination (Δ) was calculated as: Δ = (δ

13Cₐ − δ

13Cₚ) / (1 + δ

13Cₚ). Where δ

13Cₐ and δ

13Cₚ represent the carbon isotope composition of atmospheric CO

2 and soybean grain samples, respectively [

36]. A δ

13Cₐ value of −8.0 mUr was adopted as a standard, according to Hall et al. (1994). As commonly practiced, δ

13C values are reported in ‘per mil’ (‰), indicating that the original ratios were multiplied by 10

3.

At physiological maturity, prior to mechanical harvest, manual sampling was conducted within each treatment area. Specifically, seven 1 m2 equivalent area were randomly selected per plot, and plants within each area were harvested to assess yield components, including the number of pods per plant, grains per pod, 1000-grain weight, and total grain yield. This dual-scale approach, combining plot-level precision with commercial-scale implementation, provided both controlled experimental insight and real-world validation of FF-BR efficacy.

2.6. Statistical Procedures

Prior to statistical modeling, data from both growing seasons were tested for compliance with the assumptions of analysis of variance. Bartlett’s test was employed to assess the homogeneity of variances, Shapiro–Wilk’s test was used to evaluate the normality of residuals, and the independence of errors was checked using Durbin-Watson test.

During the 2023/2024 growing season, physiological variables related to gas exchange and yield components were analyzed using regression models to characterize response patterns across different concentrations of FF-BR. Model selection was guided by statistical significance (p < 0.05), coefficient of determination (R2), and the examination of residual distributions to ensure an accurate representation of dose–response relationships. In the subsequent 2024/2025 season, carbon isotope discrimination, grain yield, and its related traits were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Treatment means were compared using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test at a 5% significance level (p < 0.05). In parallel, Dunnett’s test was employed to enable direct comparisons between each treatment and the control (no FF-BR), allowing the identification of statistically superior or inferior responses relative to the standard reference.

A heat map was constructed to visualize the spatial distribution of filled locules across plant nodes. All statistical analyses and graphical outputs were generated using SigmaPlot version 15 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA, 2022).

4. Discussion

Water deficit—whether caused by irregular rainfall patterns or deficit irrigation—remains a major constraint to agricultural productivity, exerting complex and often deleterious effects on plant physiological function. Among the primary stress responses is the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can lead to oxidative damage of cellular membranes through lipid peroxidation and interact detrimentally with proteins and nucleic acids. These disruptions compromise key photochemical and biochemical processes in the photosynthetic apparatus, ultimately impairing carbon assimilation, reducing biomass accumulation, and limiting yield potential [

16,

38,

39]. In response, foliar-applied biostimulants like FF-BR, a chitosan-based formulation, offer critical insights into enhancing crop resilience and mitigating these negative effects. Recent developments in plant stress physiology emphasize the promising role of chitosan-based formulations in enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stressors [

39]. FF-BR contains two main functional components: chitosan and pyroligneous acid (PA). Chitosan, a key active constituent, acts as a potent elicitor of defense signaling networks, modulating multiple biochemical and molecular pathways central to stress adaptation [

40,

41,

42]. Upon foliar application, chitosan is perceived by specific pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) located in the plant plasma membrane, initiating a rapid cascade of intracellular responses. Among these, the production of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) through the chloroplast-localized octadecanoid pathway plays a pivotal role as a secondary messenger. H

2O

2 acts not merely as a reactive species, but as a finely tuned signal transducer that orchestrates the transcriptional upregulation of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, CAT, APX), stress-related transcription factors, and osmoprotectant biosynthesis. Through these coordinated responses, chitosan enhances redox homeostasis, preserves membrane integrity, and safeguards metabolic functions, thereby promoting sustained photosynthetic activity, reproductive stability, and overall resilience under drought and temperature stress [

43].

Complementing chitosan’s biochemical mode of action, pyroligneous acid (PA)—the second functional component of the FF-BR formulation—also contributes significantly to stress mitigation and productivity enhancement. PA, a byproduct of biomass pyrolysis, is chemically rich in organic acids, phenols, ketones, and esters, which are known to act as signaling molecules and metabolic modulators in plants [

44]. Recent metabolomic and transcriptomic studies have shown that PA can activate hormonal signaling cascades, particularly those related to abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), and secondary metabolism, thereby priming the plant for enhanced tolerance to abiotic challenges [

45,

46]. According to these authors, in rapeseed, PA treatments under low-temperature stress led to the differential expression of key genes associated with stress perception, antioxidant defense, and carbon/nitrogen partitioning, resulting in improved energy balance and membrane protection. Moreover, PA has been shown to modulate the rhizosphere microbiome, improve nutrient availability, and stimulate enzymatic pathways involved in photosynthesis and detoxification. Through this multilayered and synergistic biochemical action, PA not only strengthens plant defense but also enhances physiological performance under constrained environmental conditions. Together, chitosan and pyroligneous acid in the FF-BR formulation act as biochemically complementary elicitors, stimulating both systemic defense responses and metabolic optimization pathways. Their integration offers a robust and field-relevant strategy to promote water use efficiency, photosynthetic stability, and yield preservation under water deficit and thermal stress—providing a scientifically grounded solution for climate-resilient crop production [

16].

A notable insight from the 2023/2024 data was that optimal FF-BR benefit did not require maximizing carbon assimilation. Rather, a moderate photosynthetic rate coupled with significantly improved iWUE at 1.00% FF-BR application enabled plants to maintain growth with lower transpirational cost. This effect likely results from partial stomatal closure, possibly mediated by ABA-related or ROS-scavenging pathways commonly associated with chitosan and pyroligneous formulations [

40,

47]. By reducing stomatal aperture without collapsing photosynthetic metabolism, the plant conserves soil moisture for critical reproductive functions, which aligns with the observed increase in pod number and grain set under the most effective treatment. This finding resonates with modern physiological water deficit adaptation theory: the most successful plants are not those that grow fastest under ideal conditions, but those that adjust gas exchange most efficiently when water becomes limiting. FF-BR thus acts not as a growth stimulant per se, but as a precision stress modulator—delaying the onset of hydraulic stress while supporting yield continuity.

The physiological effects of chitosan-based biostimulants on net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and their antitranspirant properties have been widely documented [

16,

40,

48,

49]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying chitosan-induced stomatal regulation remain only partially understood. A key contribution by [

50] demonstrated that foliar application of chitosan significantly reduced transpiration and stomatal aperture in bean plants. Their results showed that chitosan treatment triggered a threefold increase in endogenous abscisic acid (ABA) levels within 24 hours of application, a response associated with its antitranspirant activity. According to these authors, stomatal behavior was mediated via a hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2)-dependent signaling pathway, confirmed through scanning electron microscopy and histo-cytochemical techniques. Moreover, the study revealed that chitosan enhanced guard cell sensitivity to ABA, effectively priming the stomatal complex for a more responsive closure under water-limiting conditions.

In our study, foliar applications of FF-BR, a chitosan-based formulation, led to consistent improvements in intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE) across treatments, regardless of product concentration, in 2023/2024 growth season. This enhancement in iWUE was attributed to subtle reductions in stomatal conductance that occurred without significant impairment of net photosynthetic rate, thereby maintaining carbon gain while reducing water loss. These optimized gas exchange dynamics translated into measurable increases in soybean grain yield, demonstrating the physiological and agronomic value of targeted chitosan application under field conditions prone to water deficit. Recent research has advanced our understanding of chitosan-induced abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis and its role in stomatal regulation under stress conditions. Chitosan-based product application has been shown to increase endogenous ABA levels, which are critical for triggering stomatal closure, particularly during drought, thereby minimizing transpirational water loss while preserving photosynthetic capacity [

49]. A 2024 study demonstrated that chitosan application in

Arabidopsis thaliana leads to stomatal closure, mediated by ABA but negatively regulated by glutathione (GSH), suggesting a complex interplay between chitosan treatment and plant hormonal responses [

51]. This regulatory mechanism was likely operative in our study as well, where foliar application of FF-BR—a chitosan-based bioproduct—resulted in high net assimilation rates despite modest reductions in stomatal conductance, indicative of an improved intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE). Further mechanistic insights are provided by [

40], who reported that chitosan nanoparticles enhance photosynthetic efficiency not only through ABA induction but also by stimulating antioxidant defense pathways, which collectively mitigate oxidative stress and enhance plant resilience. These findings help explain the physiological stability observed in our trials, where FF-BR enabled soybean plants to optimize water use and maintain metabolic function under field-imposed water deficit. Rainfall distribution during the two study seasons shaped not only the intensity of water deficit but its physiological consequences. In 2023/2024, the late onset of water deficit, coinciding with flowering to grain filling, imposed a terminal water deficit, traditionally recognized as the most yield-limiting phase due to its overlap with irreversible reproductive processes. In contrast, the 2024/2025 season brought chronic, moderate moisture restriction beginning during early vegetative stages and persisting into the reproductive window. Though less intense, this prolonged deficit aligned with the entire developmental cycle of the early-maturing Neogen 610 IPRO, a cultivar inherently more vulnerable to brief resource disruptions. These divergent patterns illustrate the concept of phenological water deficit matching—where the alignment between stress timing, severity and crop sensitivity phase determines the potential for yield rescue. The evidence here supports that terminal stress in longer-cycle cultivars (e.g., Soytech ST 641 I2X) can be mitigated by strategic intervention during flowering, while prolonged stress in early-cycle genotypes may require repeated bioactivation to sustain performance.

Beyond the biostimulants effects, cultivar maturity group remains a fundamental determinant of drought response in soybean. The relative length of the growth cycle influences not only biomass accumulation and canopy architecture, but also the timing and duration of exposure to seasonal water deficits [

52]. In our study, two cultivars with differing relative maturity groups— Soytech ST 641 I2X (MG 6.4) and Neogen 610 IPRO (MG 6.1)—exhibited distinct physiological behaviors and yield responses when subjected to differing rainfall patterns over two growing seasons. Long-cycle cultivars, such as Soytech ST 641 I2X, typically invest heavily in vegetative and root growth prior to flowering, promoting a deep and expansive root system. This trait enhances the plant’s ability to capture water from deeper soil layers, supporting transpiration and carbon assimilation even under late-season drought [

52]. Additionally, these genotypes tend to have greater capacity for stem carbohydrate storage and remobilization, which can sustain reproductive development and grain filling under restricted water availability [

53]. In the 2023/2024 season, despite a terminal drought during flowering and pod-filling, Soytech ST 641 I2X maintained physiological stability and reproductive output, confirming its resilience to acute water stress. The physiological modulation induced by FF-BR application in this cultivar—characterized by improved intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE) via slight reductions in stomatal conductance with minimal impact on net photosynthesis—resulted in moderate but consistent yield increases. The evidence supports that terminal stress in longer-cycle cultivars can be mitigated by strategic intervention during flowering.

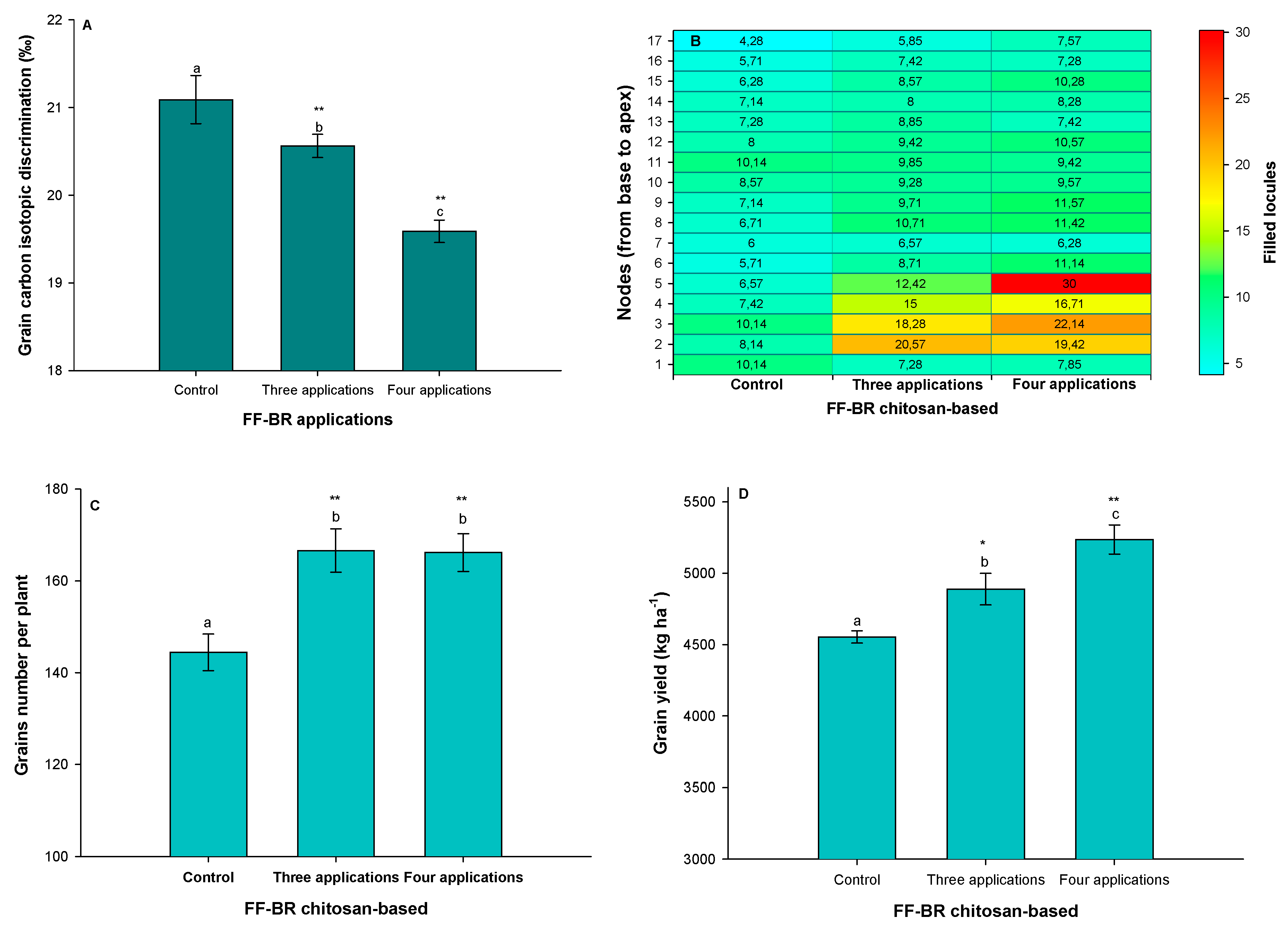

In contrast to the abrupt and severe terminal drought experienced by the more long-cycle cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X in the 2023/2024 season, the early-maturing cultivar Neogen 610 IPRO experienced a more gradual yet prolonged water deficit during the 2024/2025 cycle. This stress began early in the vegetative stage and persisted throughout reproductive development. Although the intensity of this moisture limitation was moderate, its extended period provided conditions conducive to progressive physiological acclimation. Such acclimation likely involved a coordinated modulation of stomatal conductance, osmotic balance, and hormonal signaling pathways, particularly those mediated by abscisic acid (ABA) [

40,

49], enabling Neogen 610 IPRO to sustain metabolic function across critical growth stages. Support for this interpretation is found in

Figure 6A, where a significant reduction in grain carbon isotope discrimination (Δ

13C) was observed under FF-BR treatment, especially following four sequential applications. This decline in Δ

13C reflects an increase in intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE), a physiological adjustment wherein plants optimize carbon fixation while minimizing transpirational water loss. The inverse relationship between Δ

13C and iWUE is well-established: under water-deficit conditions, partial stomatal closure limits CO

2 diffusion into the leaf, decreasing the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO

2 concentration (Cᵢ/Cₐ). As a result, discrimination against the heavier carbon isotope (

13C) during photosynthesis is reduced, yielding lower Δ

13C values. Thus, the Δ

13C response in Neogen 610 IPRO under FF-BR treatment provides a robust integrative indicator of improved stomatal regulation and water conservation. [

16,

46,

54].

What is particularly noteworthy is that this enhancement in water use efficiency was not accompanied by trade-offs in reproductive development. On the contrary, the

Figure 6B clearly illustrate improve in reproductive resilience, with increased locule filling observed from node two upward along the main stem. Although the response magnitude varied, both the three- and four-application treatments consistently sustained higher locule filling compared to the untreated control, indicating a robust and dose-responsive preservation of reproductive sink strength under prolonged water deficit. This spatial pattern of pod development suggests that photoassimilate allocation to reproductive sinks was sustained, even under prolonged water deficit. This outcome likely reflects the synergistic effects of improved stomatal control and carbon assimilation, enabling a steady supply of assimilates to support pod retention and grain filling. In summary, the reduced Δ

13C values observed in Neogen 610 IPRO under FF-BR treatment indicate that the chitosan-based formulation promoted a physiologically conservative strategy: moderating stomatal aperture to conserve water, while preserving photosynthetic activity and maintaining sink strength. This finely tuned response illustrates how bioactivation with FF-BR enabled the plant to stabilize its metabolism under chronic stress, translating into higher reproductive success and grain yield despite prolonged water deficit conditions. From a yield component perspective,

Figure 6C shows that the most significant gain in grain number per plant occurred with four FF-BR applications—an outcome that likely stems from improved flower retention and grain filling capacity rather than set pod and increased grain size, as 1000-grain weight which remained statistically unchanged, data not shown. Ultimately, these gains translated into a statistically significant yield increase of 682 kg ha

−1 relative to the control, confirming the efficacy of repeated physiological priming under prolonged stress conditions.

Together, these findings emphasize the need to match biostimulant strategies to cultivar-specific physiology and environmental context. For long-cycle cultivars like Soytech ST 641 I2X, a well-timed FF-BR application during early reproductive stages can optimize gas exchange and preserve yield under terminal drought. Conversely, for early-cycle genotypes like Neogen 610 IPRO, multiple applications are necessary to provide continuous physiological support throughout a more extended period of water limitation. Moreover, the physiological data suggest that application should target periods when stomatal function is beginning to constrain carbon assimilation, but before irreversible reproductive losses occur. This aligns with recent literature emphasizing “priming” rather than “boosting” as the core mechanism of effective biostimulants under abiotic stress.

In the broader context of climate-smart agriculture, the consistent yield improvements achieved through FF-BR application across both growing seasons—despite variability in rainfall patterns and cultivar maturity—are agronomically and economically significant. During 2023/2024 season, under a terminal water deficit scenario, the long-cycle cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X showed an average grain yield increase across all FF-BR concentrations in the long-cycle cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X reached 385 kg ha−1. In the 2024/2025 season, under prolonged but moderate water stress, FF-BR applications in the early-cycle cultivar Neogen 610 IPRO resulted in gains of 335 kg ha−1 with three applications and 682 kg ha−1 with four applications. When averaged across seasons, cultivars, concentrations, and application frequencies, FF-BR delivered a mean grain yield gain of 463 kg ha−1, with no observed yield penalties or adverse metabolic trade-offs.

Such yield stability under veranic-prone conditions could substantially enhance system resilience and profitability in the Midwest Paraná’s rainfed soybean production, which covers approximately 1.2 million hectares [

9]—the specific scope area where the FF-BR experiments were conducted. With the application of FF-BR biostimulant, an average yield gain of 463 kg per hectare could be achieved across this region, resulting in an additional production of about 555,600 tons of soybean. At a three-year average market price of

$498 per tonne [

55], this translates into an estimated monetary gain of approximately

$276.7 million USD. It is important to highlight that this estimate considers only the constituent area where experiment were conducted, while the total soybean area cropped in Paraná state is about 5.7 million hectares in the 2024/2025 growing season [

9]. These projections demonstrate the significant potential of FF-BR to improve regional productivity and profitability, while supporting climate-resilient and sustainable intensification strategies in key soybean-producing areas.

Furthermore, FF-BR’s benefits were achieved with a biogenic, low-risk input, aligning with sustainability mandates for low-residue, low-input cropping systems. Future research should explore the molecular basis of FF-BR action (e.g., ABA biosynthesis, aquaporin expression), interaction with root water uptake dynamics and canopy temperature regulation, under multi-year, multi-environment trials to assess robustness across varying climatic zones.

Figure 1.

Monthly precipitation and average air temperature recorded by an automatic weather station located near the experimental sites during the 2023/2024 and 2024/2025 growing seasons. Historical climate data (2000–2019) from this region are included for reference, providing context for seasonal variation relative to long-term regional patterns.

Figure 1.

Monthly precipitation and average air temperature recorded by an automatic weather station located near the experimental sites during the 2023/2024 and 2024/2025 growing seasons. Historical climate data (2000–2019) from this region are included for reference, providing context for seasonal variation relative to long-term regional patterns.

Figure 2.

Soybean field trial overview and gas exchange measurements conducted during the 2023/2024 growing season with the Soytech ST 641 I2X. Shows the experimental field layout immediately after the first foliar application of FF-BR, performed at the R1 developmental stage (beginning bloom) in panel A. Illustrates the setup for physiological assessments, depicting gas exchange measurements conducted at six and nine days after FF-BR application using an infrared gas analyzer in B.

Figure 2.

Soybean field trial overview and gas exchange measurements conducted during the 2023/2024 growing season with the Soytech ST 641 I2X. Shows the experimental field layout immediately after the first foliar application of FF-BR, performed at the R1 developmental stage (beginning bloom) in panel A. Illustrates the setup for physiological assessments, depicting gas exchange measurements conducted at six and nine days after FF-BR application using an infrared gas analyzer in B.

Figure 3.

Regression models and coefficients of determination (R2) describing the soybean cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X responses to increasing of foliar-applied FF-BR biostimulant concentrations. Panels A, B, and C correspond to net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and intrinsic water use efficiency, measured six days after application. Panels D, E, and F represent the same respective physiological parameters, assessed nine days after application.

Figure 3.

Regression models and coefficients of determination (R2) describing the soybean cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X responses to increasing of foliar-applied FF-BR biostimulant concentrations. Panels A, B, and C correspond to net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and intrinsic water use efficiency, measured six days after application. Panels D, E, and F represent the same respective physiological parameters, assessed nine days after application.

Figure 4.

Regression models and respective coefficients of determination (R2) depicting the response of grain yield and its components in the soybean cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X to increasing concentrations of foliar-applied FF-BR biostimulant during the 2023/2024 growing season. Panel A represents grain yield (kg ha−1), derived from the mean of four replicates, each corresponding to a 27 m2 plot. Panels B, C, and D correspond to the 1000-grain weight (g), number of pods per plant, and number of grains per plant, respectively. These measurements were based on four replicates per treatment, each composed of six plants, totaling 24 plants per treatment. The fitted regression models describe the magnitude and direction of the responses of yield components to FF-BR application rates, offering insights into the bioactivator's dose-dependent effects on soybean productivity.

Figure 4.

Regression models and respective coefficients of determination (R2) depicting the response of grain yield and its components in the soybean cultivar Soytech ST 641 I2X to increasing concentrations of foliar-applied FF-BR biostimulant during the 2023/2024 growing season. Panel A represents grain yield (kg ha−1), derived from the mean of four replicates, each corresponding to a 27 m2 plot. Panels B, C, and D correspond to the 1000-grain weight (g), number of pods per plant, and number of grains per plant, respectively. These measurements were based on four replicates per treatment, each composed of six plants, totaling 24 plants per treatment. The fitted regression models describe the magnitude and direction of the responses of yield components to FF-BR application rates, offering insights into the bioactivator's dose-dependent effects on soybean productivity.

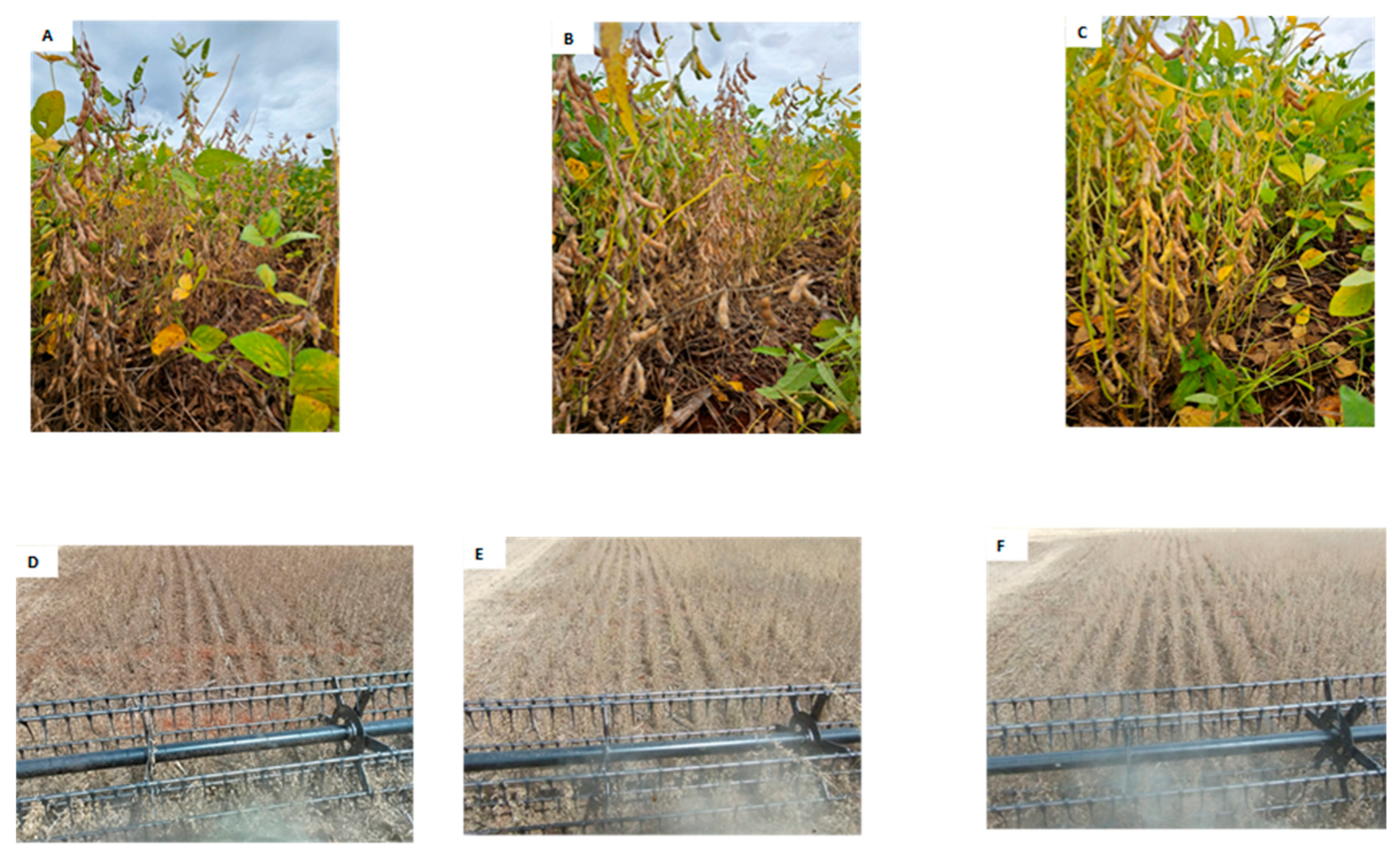

Figure 5.

Photographic records taken at the harvesting time during the reproductive stage (R8) and ground-level, from an on-farm field experiment evaluating soybean response to different application regimes of the bioactivator FF-BR on Neogen 610 IPRO. Panels A–C show images acquired along the planting rows during the final reproductive stage, representing the untreated control (A), three applications (B), and four applications (C) of FF-BR at 1.0% v:v. A progressive enhancement in canopy closure, vegetative vigor, and pod set is evident with increased application frequency. Panels D–F correspond to ground-level views at the time of mechanical harvest for the same treatments, highlighting improvements in plant stand and pod density, besides visual vigor under FF-BR treatments.

Figure 5.

Photographic records taken at the harvesting time during the reproductive stage (R8) and ground-level, from an on-farm field experiment evaluating soybean response to different application regimes of the bioactivator FF-BR on Neogen 610 IPRO. Panels A–C show images acquired along the planting rows during the final reproductive stage, representing the untreated control (A), three applications (B), and four applications (C) of FF-BR at 1.0% v:v. A progressive enhancement in canopy closure, vegetative vigor, and pod set is evident with increased application frequency. Panels D–F correspond to ground-level views at the time of mechanical harvest for the same treatments, highlighting improvements in plant stand and pod density, besides visual vigor under FF-BR treatments.

Figure 6.

Effects of increasing frequencies of foliar-applied FF-BR biostimulant on grain yield and its related physiological traits in the soybean cultivar Neogen 610 IPRO during the 2024/2025 growing season. Asterisks indicate significant differences relative to the control (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; Dunnett’s test), while different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05). Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE) based on seven biological replicates.

Figure 6.

Effects of increasing frequencies of foliar-applied FF-BR biostimulant on grain yield and its related physiological traits in the soybean cultivar Neogen 610 IPRO during the 2024/2025 growing season. Asterisks indicate significant differences relative to the control (p < 0.05; p < 0.01; Dunnett’s test), while different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments (Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05). Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE) based on seven biological replicates.

Table 1.

Classification of cultivars by relative maturity group (RMG), phenological stages at which FF-BR was applied, and the corresponding foliar application concentrations during the 2023–2024 and 2024–2025 growing seasons. In the 2024–2025 season, treatments consisted of three and four foliar applications, initiated at the R1 stage and applied at 18-day intervals, at a fixed concentration of 1.0% (v/v), in addition to a control treatment.

Table 1.

Classification of cultivars by relative maturity group (RMG), phenological stages at which FF-BR was applied, and the corresponding foliar application concentrations during the 2023–2024 and 2024–2025 growing seasons. In the 2024–2025 season, treatments consisted of three and four foliar applications, initiated at the R1 stage and applied at 18-day intervals, at a fixed concentration of 1.0% (v/v), in addition to a control treatment.

| Cultivar |

RMG |

Sowing / Flowering date |

Phenological phase of application |

FF-BR Conc. (v/v) |

| Experiment 2023-2024 |

|

|

|

|

| Soytech ST 641 I2X |

6.4 |

2023-11-10 / 2024-01-04 |

Two FF-BR applic. at 17 days interval at R1-R2 phase |

0, 0.75, 1.0, and 1.25% |

| Experiment 2024-2025 |

|

|

|

|

| Neogen 610 IPRO |

6.1 |

2024-09-30 / 2024-11-07 |

Three and four applications of FF-BR at an interval of 18 days at R1-R2 phase |

1.0% |