1. Introduction

General Relativity and its cosmological extension, the CDM model, represent a monumental achievement in modern physics. For over a century, this framework has successfully described the large-scale structure and evolution of the universe. Yet, this success is built upon two enigmatic pillars: dark matter and dark energy. These components, which together are said to constitute 95% of the universe’s energy budget, remain entirely outside the Standard Model of particle physics. They are placeholders invoked to reconcile theory with observation, but they lack a fundamental physical explanation, forcing the model into a descriptive rather than explanatory role.

In recent years, this foundational uncertainty has been compounded by a series of observational crises. A persistent and sharpening discrepancy in measurements of the Hubble constant—the Hubble Tension

Di Valentino et al. (2021)—now casts doubt on our understanding of the cosmic expansion itself. Simultaneously, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is revealing galaxies in the dawn of time that are far too massive and mature to have formed within the standard model’s timeline

Boylan-Kolchin (2023),

Labbé et al. (2023), presenting a significant challenge to our theories of structure formation. The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) has further reported evidence that dark energy may be evolving over cosmic time

Cortês and Liddle (2024),

Efstathiou (2025), contradicting the static cosmological constant of

CDM.

Together, these tensions suggest that dark matter and dark energy may not be missing substances but indications of a deeper principle—one rooted in the fundamental connection between spacetime, energy, and gravity.

1.1. Time, Gravity and Thermodynamics

The path to this theory may be illuminated by two insights of our current models. The first insight comes from Einstein’s Special and General Relativity: motion, gravity, and time are deeply interconnected. Time dilation shows that mass-energy slows the passage of time. The local rate of time is set by the energy density at that point. This effect may not be a consequence of gravity, but its very origin.

The second insight arises from the intersection of gravity, quantum theory, and thermodynamics. In 1967, Andrei Sakharov

VISSER (2002) proposed the concept of induced gravity, in which spacetime curvature emerges as the macroscopic elasticity of the quantum vacuum, similar to the fluid mechanics. Richard Feynman similarly speculated that spacetime geometry could have a thermodynamic origin, with gravitational dynamics arising from statistical behavior at the microscopic level. Stephen Hawking’s discovery of black hole radiation

Hawking (1975) and Jacob Bekenstein’s formulation of black hole entropy

Bekenstein (1973) revealed a deep and unexpected thermodynamic structure underlying gravitational phenomena. In 1995, Theodore Jacobson demonstrated

Jacobson (1995) that the Einstein field equations themselves can be derived from the Clausius relation,

, applied to local Rindler horizons, framing General Relativity as an equation of state. More recently, Erik Verlinde

Verlinde (2011) has advanced the view that gravity is an entropic force emerging from the statistical behavior of microscopic information. In parallel, Mordehai Milgrom’s Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) (

Milgrom (1983a),

Milgrom (1983b) uncovered a characteristic acceleration scale,

, which not only accounts for galactic rotation curves without dark matter but also intriguingly matches cosmological parameters such as the Hubble constant (

)

Milgrom (2020).

These insights hints that gravitational anomalies may be thermodynamic or informational in origin, rather than the result of unseen matter or arbitrary modifications of Einstein’s equations.

In this paper, we introduce the theory of gravity by modeling spacetime as a thermodynamic medium, grounded on the foundational principles of the invariance of the speed of light and the conservation of energy. Based on these axioms, we introduce two foundational principles. First, the Time-Energy Equivalence Principle posits that all forms of energy are manifestations of a single, underlying scalar field whose value represents the local rate of time. Second, the Law of Entropy Equilibrium states that the universe maintains a constant total entropy, dynamically balancing the disordering drive of heat () against the ordering drive of gravity ().

From these two foundational principles, this paper constructs a complete theory of emergent gravity. With single thermodynamic response function, we will demonstrate that MOND emerges naturally from the thermodynamics of causal horizons, leading to a set of covariant field equations that are shown to be consistent with all classical tests of General Relativity. These equations provide a unified physical mechanism for both galactic dynamics and an evolving cosmic acceleration, eliminating the need for dark matter and a cosmological constant. We then reveal the shared quantum origin of the MOND acceleration scale () and the Hubble constant (), deriving both from the first principles of quantum field theory and calculating their values in close agreement with observation. Subsequently, we develop the cosmological implications of the theory, showing how it provides a natural mechanism for an early inflationary epoch and predicts a cyclic universe. Next, we will show how this framework resolves a host of puzzles within the standard model, including the vacuum catastrophe, the Hubble tension, and the evolving dark energy problem. Finally, the theory makes several falsifiable predictions, which can be tested with future observations.

2. The Time-Energy Equivalence Principle

This theory is built upon the foundational idea that gravity is not a fundamental force, but an emergent thermodynamic phenomenon. To build this case, we first recall the analogy proposed by Jacobson

Jacobson (1995) in his derivation of the Einstein field equations from thermodynamics.

He likened gravitational waves in spacetime to sound waves in a gas—collective, statistical phenomena rather than fundamental fields. Just as the equations of sound describe the thermodynamics of countless molecular collisions, the Einstein equations may describe the statistical behavior of a deeper medium. In this view, spacetime geometry is a macroscopic, emergent observable, with Einstein’s field equations serving as an equation of state valid only under local thermodynamic equilibrium. Inspired by this, we take the next step: identifying the underlying medium as a scalar field whose defining property is the very flow of time.

To define a new spacetime medium, we start by reexamining Einstein’s own equivalence principle. It states that the effects of gravity are locally indistinguishable from acceleration. From this, a universal connection emerges: acceleration causes time dilation (as seen in Special Relativity); gravity, being equivalent to acceleration, must therefore also cause time dilation; mass is the source of gravity, so it is fundamentally a source of time dilation; radiation, being a form of energy (), also gravitates and is therefore also a source of time dilation.

This reveals a universal rule: acceleration, mass, and radiation are all linked by their common ability to alter the local rate of time. This theory elevates this connection to a foundational principle: The presence of any form of energy density within a region of spacetime is physically indistinguishable and equivalent to a localized slowing of the rate of time in that region.

Also, the speed of light, c, is a universal constant for all observers. For c to be an intrinsic property of the universe, spacetime cannot be a passive void but must be a dynamic medium whose properties determine the speed of propagation. We call this medium the Timeflow field.

The spacetime medium is modeled as a fundamental complex scalar field, . The physical phenomena of time and space emerge from the dynamics of this field’s two scalar components: its amplitude A and its phase .

-

Phase (): The Quantum “Tick” of Time.

The phase

is a scalar field, and its gradient defines a fundamental 4-vector, the Timeflow 4-vector:

. This vector covariantly represents the flow of quantum phase in spacetime. The nvariant scalar magnitude of this vector defines the local microscopic frequency,

:

This frequency is a true scalar, invariant for all observers. This scalar is proportional to the local energy density. A high energy density implies a large , which in turn manifests as a slow macroscopic passage of time. The duration of a macroscopic proper time interval () is proportional to the period of this invariant oscillation: .

-

Amplitude (A): The Structural Fabric of Spacetime.

The amplitude of the field, , is a true scalar that represents the local integrity or density of the spacetime medium itself. A high concentration of energy excites the field to a higher amplitude A. We postulate that this amplitude defines the local spatial scale. The length of a macroscopic ruler () is inversely proportional to the amplitude: .

Now, we can state the core postulate of the field’s dynamics. The invariance of the speed of light

c is a fundamental property of the metric

. Our theory postulates that this metric is constructed from

such that the field’s two scalar properties,

and

A, are dynamically locked in a constant ratio:

This ensures that time dilation (driven by

) and length contraction (driven by

A) are not independent phenomena, but are two inseparable and perfectly synchronized consequences of the field’s response to energy.

The microscopic frequency corresponds to a slowing of macroscopic time. The perceived rate of time, which we call the Timeflow factor

, is therefore inversely proportional to this underlying invariant frequency. We define the dimensionless

as the local macroscopic rate of time, normalized to the rate in a vacuum where the microscopic frequency is at its minimum ground-state value,

:

In this view, the continuous passage of time is an emergent property. In empty space, the field is in its low-energy ground state (

), and the rate of time is at its maximum (

). In a region of high energy, the field oscillates rapidly (

), which manifests as time flowing more slowly (

). The field’s amplitude,

, similarly defines the local spatial scale, such that the constancy of the speed of light emerges as a fundamental symmetry of the field, reflecting the invariant ratio between its microscopic frequency and amplitude Equation (

2).

To define the potential of this field, let’s note the recurring role of the natural logarithm in linking microscopic properties to macroscopic potentials in physics. In statistical mechanics, the entropy of a system is given by Boltzmann’s formula, , where the logarithm connects the number of microscopic states () to the macroscopic entropy.

Following this principle, we define the Timeflow thermodynamic potential,

, as the natural logarithm of the Timeflow field, as this provides the most natural connection between the underlying field and its macroscopic potential:

2.1. Energy-Momentum Tensor of the Universe

The mathematical expression of the total energy-momentum tensor of the universe could be expressed as the energy-momentum tensor of the Timeflow Potential field itself:

This implies that what we perceive as "matter" and "spacetime" are not separate entities, but different manifestations of this single, underlying field. For the purpose of constructing a workable physical model, we decompose the total energy of the Timeflow field into two distinct components:

The Matter Component (): This represents the energy of stable, self-sustaining, localized configurations of the Timeflow field. These highly-condensed, persistent "solitons" are what we observe as particles of matter.

The Vacuum Component (): This represents the energy of the field’s potential and gradients between the localized matter configurations. It is the energy of the medium itself—the "elastic tension" of the field as it is stretched and compressed by the presence of matter. This is the component responsible for what is traditionally perceived as vacuum energy.

Therefore, our foundational principle can be expressed as a decomposition:

The terms

and

(where

v now refers to the vacuum/background component) are not fundamentally different substances, but a practical separation of the total field energy into its condensed and diffuse parts. From this perspective, all energy in the universe is ultimately a manifestation of a single conserved quantity: the rate at which the quantum state of the universe evolves.

2.2. Gravity as the Gradient of Time

The core physical mechanism of the theory emerges directly from its fundamental conservation law, which dictates the balance between the local energy density, , and the local rate of time, . This law states that an increase in the concentration of energy must be met with a corresponding decrease in the rate of time. Since what we perceive as matter is simply a stable, localized concentration of the Timeflow field’s energy, it follows that matter is intrinsically a region of slowed time.

What we call gravity is the emergent effect of this principle. The universe is a temporal landscape, where elevation is the local rate of time. Matter creates deep valleys of slow time. Other concentrations of energy are not pulled by a force but are naturally drawn to follow the gradient of this landscape, moving towards the regions where time flows the slowest. This subsection provides the mathematical justification for this physical picture.

Our starting point is the established physics of General Relativity in the weak-field limit, where the proper time,

, experienced by an observer is related to the coordinate time,

, via the Newtonian gravitational potential,

:

The Timeflow factor,

, is fundamentally defined as the local rate of time, meaning it is the conversion factor between proper time and coordinate time:

. By comparing these two relations, we find a direct link between the

and the

:

This demonstrates that in the weak-field limit, the Timeflow factor is equivalent to the time component of the spacetime metric in General Relativity.

To connect this to dynamics, we use the Timeflow thermodynamic potential,

. For weak fields where

is small, we can use the approximation

:

The Newtonian acceleration is defined as the negative gradient of the gravitational potential,

. By substituting our expression for

, we arrive at the fundamental relationship:

This shows that acceleration is directly proportional to the gradient of the Timeflow potential. This is not merely an approximation but the low-energy limit of a more general, fully covariant principle. We therefore elevate this to a fundamental definition of four-acceleration,

:

In this view, a free-falling object follows a geodesic not because it is being acted upon by a force, but because it is following a path of zero acceleration through the landscape defined by the rate of time. Its worldline is one that extremizes the proper time, which corresponds to navigating the gradients of the Timeflow potential. The phenomenon of gravity is thus reduced to the dynamics of a single scalar field, which dictates the local rate of time throughout the universe.

3. The Law of Entropy Equilibrium

If Timeflow is a quantum field, it should obey the laws of thermodynamics. The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, but only transferred or transformed from one form to another. The classical Second Law of Thermodynamics asserts that the entropy of an isolated system cannot decrease

Odintsov et al. (2025).

We consider the entire universe as a single, isolated thermodynamic system. The total energy content of this system is described by the Timeflow field. According to the First Law, the change in the internal energy of an isolated system is zero ().

The First Law is expressed as:

where

Q is the heat added to the system and

W is the work done by the system. In the isolated universe,

, which leads to a fundamental statement of energy balance:

This implies that over any period of cosmic evolution, the total heat energy absorbed or redistributed within the system must equal the total work done by the system. If the Timeflow field represents all energy in the universe and satisfies the most fundamental First Law universally, the Second Law could be satisfied only if heat and work are balanced.

The Second Law is experimentally valid for thermodynamic systems in which gravitational effects are negligible. In such contexts, energy flows primarily through heat and radiation, and the law correctly describes the tendency of energy to spread, equilibrate, and become less available for work.

Howewer, as emphasized by Roger Penrose

Penrose (1980), gravity fundamentally alters the entropy dynamics of the universe. Unlike thermal processes, gravitational interaction concentrates energy, reduces local entropy, and creates ordered configurations. In the interplay of heat and gravity, the universe does not evolve monotonically toward disorder. Instead, it is governed by a dynamic balance between two opposing entropic drives:

The Drive for Chaos (): This is the standard thermodynamic entropy of the system, representing the field’s kinetic energy, or “heat.” It is a measure of the microscopic disorder associated with the field’s temporal oscillations. This disorder is fundamentally quantified by the microscopic frequency (

) of the Timeflow field. A higher frequency corresponds to more rapid phase evolution, and thus higher entropy. The physically consistent definition, following the Boltzmann framework, is:

where

is the ground-state frequency of the vacuum. The relationship to heat is given by the Clausius relation:

-

The Drive for Order (): This is the negentropy of the system, representing the field’s potential energy stored in gravitational structures. It is a measure of structural information (

) and order. This order is fundamentally quantified by the microscopic amplitude (

A) of the Timeflow field. A higher amplitude corresponds to a more energetic, gravitationally bound, and structurally ordered state. The definition is therefore:

where

is the ground-state amplitude of the vacuum. The work done to create this structure is given by:

The negative sign signifies that as the system does positive work to build structure (), its entropy, , must decrease, signifying a greater degree of order.

We then calculate the total entropy that must obey this structural rule. The total entropy is the sum of the chaotic and orderly components:

Substituting the definitions for chaos and order entropy:

Using the properties of logarithms, we can combine these terms:

Now, we apply the invariance of the speed of light axiom from Eq. Equation (

2). Since

, the term inside the logarithm is identically 1:

This yields the final result:

Therefore, to satisfy the First Law of Thermodynamics and the invariance of the speed of light, we propose a more fundamental principle:

The total entropy of the universe is dynamically balanced by an opposing process of structuring and dissipation, such that the sum of chaos and order entropy remains constant.

The dynamics of this evolution are governed by a single, universal non-linear response function, , which dictates how the field responds to gradients in both space and time. This response is characterized by a single fundamental constant, the Timeflow critical temperature, .

This non-linear symmetry provides an explanation of why ordered energy configurations () have an inherent tendency to evolve towards greater complexity, progressing through a hierarchy of emergent structures. In this picture, the growth of complexity is not a violation of thermodynamics, but rather a manifestation of the balance condition, where increases in local order are compensated by corresponding increases in surrounding chaos, preserving the total entropy.

3.1. The Arrow of Time

With this framework we can make a deeper explanation for the observed arrow of time and the Second Law. The relentless tendency of gravity to form structure means that the structural information of the universe is a non-decreasing function of time.

The law of entropy equilibrium is thus stated as an equality between the thermodynamic entropy of the universe,

, and the total information encoded in its gravitational structure,

Substituting these definitions into the equilibrium law Equation (

19) yields:

This directly implies the classical Second Law of Thermodynamics as an emergent consequence of structure formation.

The observed increase in thermodynamic entropy is thus driven by, and paid for by, the continuous writing of information into the cosmic web by gravity.

4. Temperature and Acceleration

The background "Drive for Chaos" is identified with the temperature of the cosmological event horizon. In an accelerating universe described by a Hubble constant , this horizon has a characteristic Gibbons-Hawking temperature.

The temperature of the de Sitter cosmological horizon is given by:

where

is the Hubble radius,

. We define the theory’s Critical Temperature (

) as this fundamental background temperature.

This simplifies to a direct relationship between the critical temperature and the rate of cosmic expansion:

The Unruh effect

Unruh (1976) establishes a fundamental equivalence between acceleration and temperature for any observer.

A simple equivalence of these two temperatures () would lead to the relation . However, this fails to account for the crucial geometric difference between the two phenomena. The Unruh effect describes the temperature experienced by a linearly accelerating observer, while the Gibbons-Hawking temperature describes the thermal properties of a spherically symmetric cosmic horizon.

To connect a local, linear phenomenon to a global, spherical one, a geometric factor of

is required. This factor relates the radius of a circle to its circumference and is a fundamental signature of the difference between linear and rotational or spherical geometries. We therefore postulate that the correct relationship between the two temperatures is:

This equation states that the critical local acceleration

is the one whose Unruh temperature matches the effective temperature of the cosmic horizon when viewed from a local, linear frame.

By substituting the expressions for the temperatures Equation (

23) and Equation (

24) into this corrected relationship, we find:

The physical constants cancel, yielding the final connection between the local acceleration scale and the global cosmic scale:

The constant acts as a global parameter because it’s a direct manifestation of a critical background energy density—the vacuum energy of spacetime itself, which in GR is described by the cosmological constant and drives the universe’s expansion .

This background energy density provides a universal "floor" value. Any gravitational interaction with an acceleration significantly above this floor behaves classically Newtonian, while any interaction that falls to the level of this floor enters the modified (MOND) regime.

5. Deriving the and the

The fundamental principle of this theory is that the dynamics of the universe is governed by a fundamental complex scalar field . Therefore, macroscopic cosmological parameters, like the Hubble constant , and galactic dynamical scales, like the MOND acceleration , are emergent properties determined by the quantum nature of this field’s stable vacuum state.

This vacuum state, where the field has a non-zero magnitude , was established via a quantum transition from a primordial, unstable “false vacuum” (). The tunneling rate of this transition set the fundamental residual oscillation frequency of the true vacuum, . This section derives and from this fundamental vacuum frequency.

The stabilization of the

field is modeled as a quantum tunneling process from an unstable false vacuum to the stable true vacuum. In non-perturbative QFT, the decay rate per unit volume for such a transition is given by the Coleman–Callan formula

Callan and Coleman (1977);

Coleman (1977):

where

is the Euclidean action of the instanton solution, and

C is a prefactor determined by fluctuations around this solution.

In general, instanton actions in gauge theories scale as

where

g is the coupling constant of the interaction. This scaling reflects the exponential suppression characteristic of non-perturbative processes. For QED,

is proportional to the fine-structure constant,

. In natural units (

),

Thus, the Euclidean action for the stabilization of the Timeflow field is naturally expressed as

This has the same mathematical form as the Schwinger effect

Schwinger (1951), which describes electron–positron pair creation in a strong electric field.

Dimensional analysis requires the prefactor to carry units of inverse-time per inverse-volume (

). Constructing such a scale from the fundamental constants

uniquely identifies the Planck frequency per Planck volume:

where

is the Planck time,

is the Planck volume, and

K is a dimensionless constant of order unity. The crucial insight is that this calculated transition rate is the fundamental microscopic frequency of the resulting true vacuum. Choosing the natural value

, we therefore identify:

The fundamental microscopic vacuum frequency

must be related to the macroscopic Hubble expansion rate. This requires a geometric scaling factor, analogous to the relation between the Unruh temperature (linear acceleration) and the Gibbons–Hawking temperature (spherical de Sitter horizon), which differ by a factor of

Equation (

27). By the same reasoning, we identify

Substituting Equation (

33), we obtain the final expression:

This result states that the Hubble constant is the fundamental quantum transition frequency of the vacuum, scaled by a geometric factor of

.

This framework provides a deep, quantum-level explanation for the MOND acceleration constant,

, which governs galactic dynamics. By substituting our expression for

Equation (

27), we can find the origin of

:

This reveals that the MOND acceleration scale is simply the fundamental quantum frequency of the vacuum (

) translated into the language of acceleration by the universal conversion factor,

c. This unifies cosmology (

) and galactic dynamics (

), showing that they both stem from the same underlying quantum process.

5.1. Numerical Verification

We calculate the numerical values using the 2022 CODATA

Mohr et al. (2024) values for the fundamental constants:

;

;

.

From Equation (

35), we first find

in SI units:

Converting to standard cosmological units (1 Mpc

km):

Using the relationship Equation (

27) and our calculated SI value for

:

This theoretical value is in remarkable agreement with the empirically established value of

, derived from thousands of galactic rotation curves. And the fact that this framework, starting from first principles of quantum vacuum decay, can derive both the cosmic expansion rate and the galactic acceleration scale to within

and

of their observed values, respectively, provides strong corroborating evidence for its foundational concepts. We interpret these results not as the precisely observed rates, but as the bare, vacuum-driven values which are subsequently modulated by the energy density of matter and radiation in the universe.

6. Non linearity of Equilibrium

The non-linear response of gravity in this framework can be derived as an emergent consequence of viewing spacetime as a thermodynamic medium in a state of entropy equilibrium. We derive our non linear function by modeling the microscopic degrees of freedom on a local Rindler horizon.

The foundation of Jacobson’s thermodynamic gravity

Jacobson (1995) is the relation

applied to a causal horizon. Here,

is the energy flux crossing the horizon, which is sourced by matter and gives rise to the Newtonian gravitational force,

. The temperature

T is the Unruh temperature perceived by an observer experiencing the effective gravitational force,

.

The Principle of Entropy Equilibrium Equation (

19) suggests that the vacuum is not a passive background but possesses an intrinsic "ordering drive", characterized by the fundamental acceleration scale

. This drive competes with the local "chaotic drive," characterized by the effective gravitational acceleration

a, which seeks to activate the horizon’s entropic degrees of freedom.

We model the microscopic bits of information on the horizon as existing in one of two states: ordered bits held in a low-entropy state by the background ordering drive and disordered bits activated by the local acceleration a, which are then able to contribute to the horizon’s entropy.

Let p be the fraction of bits in the disordered state. The fraction in the ordered state is then . This framework employs a simple kinetic model for the transition between two states: the rate of activation (disordered → ordered) is proportional to the strength of the local chaotic drive and the number of ordered sites: and the rate of deactivation (disordered → ordered) is proportional to the strength of the background ordering drive and the number of disordered sites: .

In thermodynamic equilibrium, which a stationary Rindler horizon represents, these two rates must be equal:

where

k is a proportionality constant. This simplifies to:

Solving for

p, the equilibrium fraction of available entropic degrees of freedom, we find:

This fraction,

p, represents the non-linear response of the vacuum to a gravitational field. We therefore identify it with the universal interpolating function

, where

:

Surprisingly, this function looks exactly like MOND interpolating function.

7. Effective Gravitational Coupling

The effective change in the horizon’s entropy,

, is the standard Bekenstein-Hawking entropy change

Bekenstein (1973),

Hawking (1975),

, multiplied by the fraction of degrees of freedom available to participate in the thermodynamic exchange:

Applying the First Law of Thermodynamics,

, to the horizon:

From the Verlinde’s thermodynamic gravity derivation

Verlinde (2011), we know that the heat flow from the matter source,

, is what generates the Newtonian force,

. We also know that the product of the effective temperature and the standard entropy change,

, generates the effective force that the observer feels,

. Therefore, the thermodynamic relation simplifies to a direct relation between the forces:

Dividing by the test mass

m, we arrive at the fundamental relationship between the Newtonian gravitational field (

) and the effective field (

a), we find exactly a MOND formula:

The force law in Eq. Equation (

44) implicitly defines the effective gravitational coupling,

. By writing the fields in terms of the source mass

M and distance

R:

Substituting these into the force law:

Solving for

yields its final form:

Here we can see that this non-linear modification to gravity is inevitable consequence of the Law of Entropy Equilibrium Equation (

19).

8. Field Equations

Having derived the effective gravitational coupling

from the statistical mechanics of horizon degrees of freedom, we now generalize this result to a covariant theory. We achieve this by applying our derived

to the thermodynamic argument of Jacobson

Jacobson (1995), which shows that the Einstein Field Equations are the equation of state for spacetime.

Jacobson’s derivation considers an arbitrary point in spacetime and the local Rindler horizon perceived by an accelerating observer. The First Law of Thermodynamics, , is applied to this local horizon.

The heat flux is identified with the energy of matter crossing the horizon, as given by the flux of the matter stress-energy tensor, . The temperature T is the local Unruh temperature. The entropy change is assumed to be proportional to the change in the horizon’s area, , with the standard gravitational constant G as the proportionality factor: .

Demanding that this relation holds for all local observers forces the geometry of spacetime to obey the Einstein Field Equations: .

This theory modifies this derivation at the final step. The entropy of the horizon is not classical; it is determined by the fraction of available microstates,

. This is equivalent to replacing the fundamental constant

G with our derived effective coupling Equation (

47)

The thermodynamic law we enforce is therefore:

When this modified law is required to hold for all observers, the resulting equation of state for spacetime is no longer the standard Einstein Field Equation. Instead, it becomes a modified field equation where the coupling between geometry and matter is state-dependent:

Substituting our derived expression for

Equation (

47):

This can be rearranged into a more suggestive form, which we take as the static thermodynamical equation of gravity of the theory:

Here, the argument of

is implicitly a function of the local geometry, as the effective acceleration

a is determined by the curvature of spacetime.

8.1. The Stress-Energy and Conservation

To better understand the physical content of this equation, we can express it in the standard form of General Relativity by defining an effective stress-energy tensor for the vacuum part of total energy of Timeflow field,

Equation (

6), such that:

By comparing this with Equation (

51), we can directly solve for

:

Alternatively, substituting

, we find its expression in terms of pure geometry:

This tensor represents the energy, momentum, and pressure of the effective scalar degree of freedom. The conservation of this tensor,

, is guaranteed by the Bianchi identity

Wald (1984) (

) and the conservation of matter (

), leading to the same consistency condition as before:

This completes the derivation of the full covariant framework.

9. Consistency with General Relativity

The Timeflow Gravity (TG) field equation Equation (

51) modifies the Einstein Field Equations by introducing the state-dependent thermodynamic function

. A crucial requirement for any viable theory of gravity is that it must reproduce the well-tested predictions of General Relativity (GR) in the appropriate limit, particularly within the Solar System.

The consistency of TG with GR is ensured by the behavior of the function in the high-acceleration regime. The behavior of the theory is determined by the ratio , where a is the local gravitational acceleration and is the critical acceleration scale. The Solar System is a high-acceleration environment (, or ).

The derived interpolating function Equation (

40) is:

In the strong-field limit, the function rapidly approaches unity:

Consequently, the effective gravitational constant converges to the Newtonian constant

G:

In the high-acceleration limit, the Timeflow Gravity field equations become indistinguishable from the standard Einstein Field Equations of General Relativity.

We can quantify the deviation from GR by examining the effective gravitational constant

. In the high-acceleration regime (

):

The relative deviation from GR is characterized by the small parameter

. We evaluate this deviation for the classical tests of GR.

This demonstrates that TG naturally satisfies all Solar System constraints. The modifications to gravity proposed by this theory only become significant in the ultra-low acceleration regimes found on galactic and cosmological scales, ensuring consistency with established gravitational experiments in high-density environments.

10. Emergence of the MOND

The true power of this framework lies in its ability to generate MOND-like phenomenology from its core principles. Here we derive the weak-field limit, explain the crucial role of the environment, and show how the theory naturally accounts for its own applicability at different scales.

We begin with the derived equation Equation (

51). Our goal is to find the non-relativistic, static limit of this equation, which must be consistent with the thermodynamically derived force law relating the effective acceleration (

) to the Newtonian acceleration sourced by baryonic matter (

):

By expressing these accelerations as gradients of their respective potentials (

and

) and taking the divergence of the entire equation, we can formulate a field theory. Using the standard Poisson equation,

, we arrive at:

This is the well-known AQUAL

Bekenstein and Milgrom (1984) formulation of MOND. It demonstrates that the complex covariant field equations of Timeflow Gravity naturally reduce to the successful MOND phenomenology in the appropriate limit.

A key prediction of this theory, arising from the non-linearity of Equation (

63), is the External Field Effect (EFE)

Milgrom (1986). This effect states that the internal dynamics of a gravitational system depend not only on its internal mass but also on the background gravitational field in which it is embedded.

Consider a small dwarf galaxy with low internal acceleration, , orbiting a massive host galaxy that provides a large, nearly constant external field, . The total acceleration experienced by a star in the dwarf is . The behavior of the function is determined by the magnitude of this total field, .

If the external field is strong such that , then it follows that , even if the internal acceleration is weak (). In this scenario, the entire system is forced into the high-acceleration regime where . Consequently, the internal dynamics of the dwarf galaxy will be purely Newtonian, and no MONDian effects (i.e., no need for dark matter) would be observed. The MONDian enhancement of gravity is reduced by the strong external field. This explains why some satellite galaxies appear to have less dark matter than expected—they are simply in a regime where the modified dynamics are suppressed by their environment.

10.1. The Tully-Fisher Relation and RAR

The Timeflow framework, by naturally producing MOND-like dynamics in the weak-field limit, provides a direct theoretical origin for the observed scaling laws in spiral galaxies: the Baryonic Tully-Fisher Relation (BTFR)

Tully and Fisher (1977) and the Radial Acceleration Relation (RAR)

McGaugh et al. (2016). These empirical laws are inevitable consequences of the theory’s fundamental force law.

The BTFR is the observed tight correlation between a galaxy’s total baryonic mass () and its asymptotic flat rotation velocity (), empirically found to be . In the Timeflow theory, this arises directly from the deep-MOND limit.

For a test particle (like a star) in a stable circular orbit at a large radius in a galaxy, the effective gravitational acceleration is given by the centripetal acceleration,

. In the outer regions of galaxies, this acceleration is far below the critical scale,

. In this low-acceleration regime, our derived force law from Equation (

44) simplifies to:

The Newtonian gravitational field,

, is sourced by the total baryonic mass of the galaxy,

. Equating the two expressions for

:

The radial distance term,

, cancels from both sides, leaving a direct relationship between the galaxy’s mass and its flat rotation velocity:

This is precisely the Baryonic Tully-Fisher Relation, with the correct fourth-power dependence. The theory thus provides a first-principles explanation for this fundamental law of galactic dynamics.

The RAR is the tight empirical correlation observed between the acceleration felt by stars () and the acceleration that can be accounted for by the visible baryonic matter alone (). This relation is a direct restatement of the theory’s central force law.

By identifying the effective acceleration (

a) with the total observed acceleration (

), and the Newtonian acceleration (

) with the acceleration sourced by baryons, our fundamental force law from Equation (

44) can be written as:

This equation provides a unique, one-to-one mapping between the baryonic acceleration and the observed acceleration, which is exactly what the RAR shows. The specific functional form of

derived in Equation (

40) dictates the precise shape of the RAR, which has been shown to be an excellent fit to observational data. The RAR is therefore is the most direct observational evidence for the non-linear thermodynamic response of the Timeflow field that underpins the entire theory.

11. Cosmological Equations

In the standard cosmological model, the expansion of the universe is described by the time evolution of a scale factor

, governed by the Friedmann equations

Friedman (1922) of General Relativity. This expansion is often framed as a stretching of space itself, but from the perspective of Timeflow Gravity, the phenomenon has a more direct and unified interpretation: energy density, cosmic expansion and time dilation are representations of the same phenomena.

Special Relativity already teaches us that energy, time and space are inseparably linked. A moving clock runs slower relative to a stationary observer, and moving rulers contract in length. These effects are not separate phenomena: they are complementary manifestations of the Lorentz transformation, which preserves the spacetime interval between events. In TG, this principle is extended to the entire cosmos: just as velocity in SR changes the relationship between time and space for a moving observer, cosmic energy density changes the relationship between time and space for every observer in the universe. When the rate of time changes, space must expand or contract to preserve the overall entropy and structure of spacetime.

In this view, the scale factor and the global timeflow rate are two sides of the same coin. In a denser early universe, was lower, meaning that proper time ran more slowly everywhere. As the universe diluted, increased, and this relative speeding-up of time manifests as the observed expansion of space. Cosmological redshift is therefore both a record of the change in spatial scale and a record of the change in the Timeflow field between emission and observation.

From the TG standpoint, the large-scale cosmic acceleration is not driven by an arbitrary cosmological constant, but emerges naturally from the vacuum component of the Timeflow field. The same non-linear thermodynamic law that modifies gravity at galactic scales also governs the global evolution of , and hence . This directly links the cosmic acceleration observed today to the critical acceleration scale measured from galaxy rotation curves, providing a symmetry between local gravitational physics and global cosmological dynamics.

Here we derive the cosmological field equations by applying the covariant TG framework to a homogeneous and isotropic Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW)

Robertson (1935) spacetime. We begin with the two necessary components:

FLRW metric, where

is the scale factor and

k is the curvature parameter (

for a flat universe).

And we model the contents of the universe (matter and radiation) as a perfect fluid with a total energy density

and pressure

. Its stress-energy tensor is:

The argument for the function

is based on the horizon temperature, which in cosmology corresponds to the Hubble rate

. So, we have

.

11.1. First Modified Friedmann Equation

The first equation, which relates the expansion rate to the energy density, comes from the "time-time" (00) component of the field equation.

For the FLRW metric, the 00 component of the Einstein Tensor

is a standard result:

Multiplying by

gives:

The 00 component of the stress-energy tensor for a perfect fluid is its energy density:

Multiplying by the constants gives:

Setting the two sides equal and simplifying yields the First Modified Friedmann Equation:

For a flat universe (

), this simplifies to the final form:

11.2. Second Modified Friedmann Equation

Derivation of the second equation reveals the crucial role of the Timeflow field’s vacuum component, which drives cosmic acceleration.

The theory’s covariant field equation states that spacetime geometry is sourced by the total stress-energy of the Timeflow field, which is the sum of the matter component (

) and the vacuum component (

) Equation (

51). The vacuum component is sourced by matter via the MOND function,

Equation (

53) This allows us to define the total effective energy density (

) and pressure (

) that govern the expansion.

The total energy density is the sum of the matter and vacuum components.

The vacuum component, as the "elastic tension" of the field, must have a negative pressure, with an equation of state

. The total pressure is therefore:

We now use these total quantities in the standard acceleration equation from General Relativity:

Substituting our expressions for

and

:

Rearranging to make the terms clear, we arrive at the final, Second Modified Friedmann Equation:

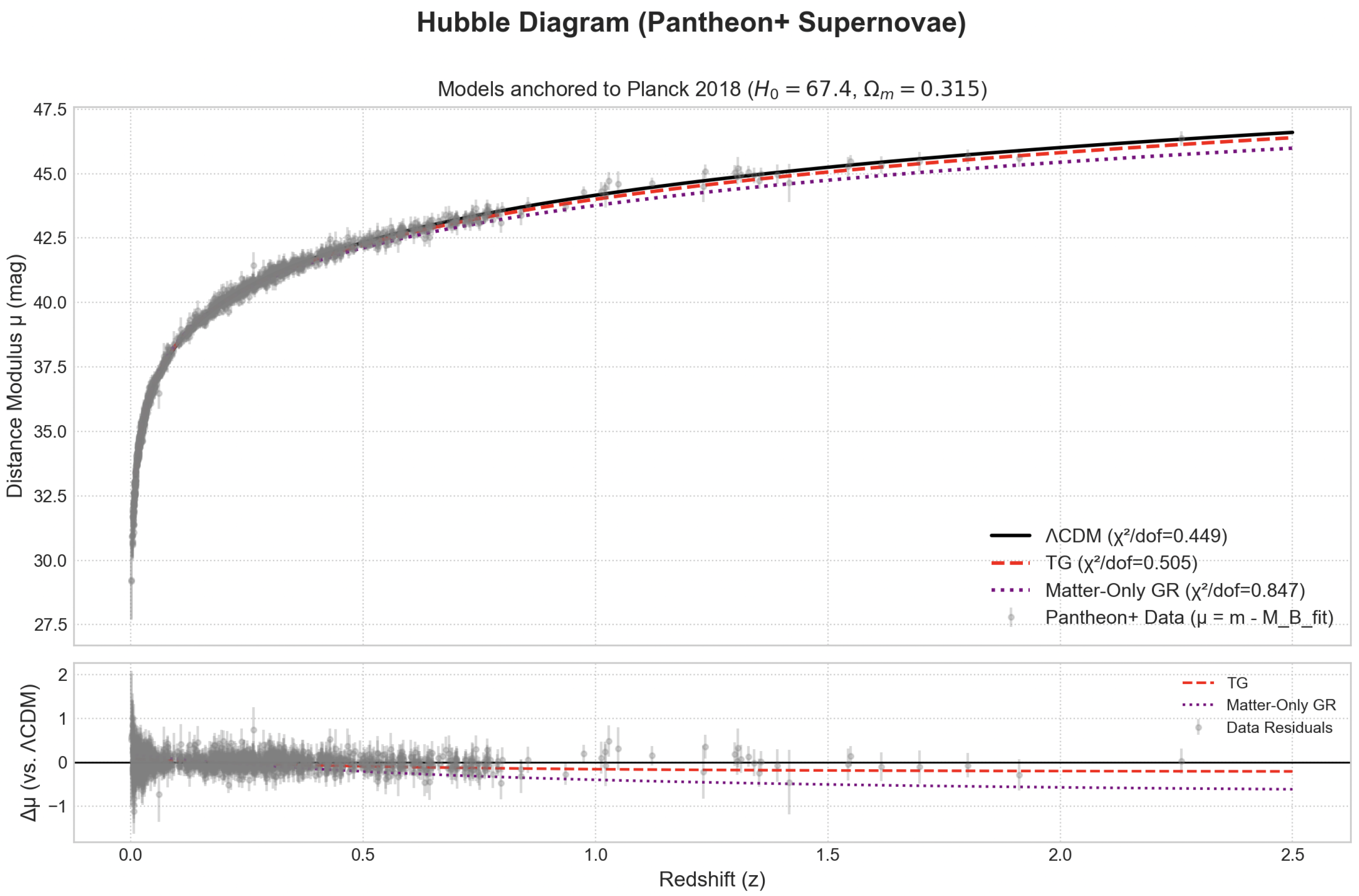

12. Cosmological Tests

To test the viability of the Timeflow Gravity model, we compare its predictions for key cosmological observables against the standard CDM model. The following figures were generated by numerically solving the cosmological equations for both models. For a direct and fair comparison, both models were initialized with the same standard observational parameters from the Planck 2018 data release: Present-day Hubble Constant: km/s/Mpc Present-day Matter Density Parameter:

The CDM model additionally uses , while the TG model uses the matter density as its sole input, with the effective dark energy component emerging naturally from the theory’s equations.

12.1. Data Samples and Methodology

The primary observational dataset used for this initial test is the Pantheon+ compilation of Type Ia supernovae

Scolnic et al. (2022). By measuring their apparent brightness (magnitude,

) across a range of redshifts (

z), we can determine their luminosity distance (

) and construct a Hubble diagram, which maps the expansion history of the universe. The Pantheon+ dataset provides high-quality light curves and distance estimates for over 1700 supernovae, spanning redshifts from

to

, making it ideal for probing the late-time accelerated expansion.

Our methodology involves the following steps for each cosmological model (

CDM, TG, Matter-Only GR). We fix the present-day Hubble Constant to

km/s/Mpc based on Planck 2018 data for all models. We also fix the present-day matter density parameter

according to the model being tested (

for

CDM and the empirical TG test,

for Matter-Only GR). Using the Friedmann equations specific to each model, we numerically integrate to find the predicted luminosity distance

for every supernova in the Pantheon+ sample. Then we convert the luminosity distances to theoretical distance moduli using the standard formula:

. The observed quantity is the apparent magnitude

, which is related to the distance modulus by

, where

is the absolute magnitude of the supernova. Since

is assumed to be constant for all Type Ia supernovae but has some uncertainty, we treat it as a free parameter. For each model, we find the single value of

that minimizes the chi-squared (

) statistic between the model prediction (

) and the observed magnitudes (

) with their associated errors (

):

We calculate the reduced chi-squared, (where dof is the number of data points minus the number of fitted parameters, which is 1 for ), for each model. This value quantifies how well the model’s predicted expansion history fits the Pantheon+ data, with values closer to 1 generally indicating a better fit.

This procedure allows for a direct, quantitative comparison of the models’ ability to explain the observed supernova brightnesses, providing a robust test of their viability.

12.2. Results and Interpretation

The cosmological tests performed in this section against the Pantheon+ Type Ia supernova dataset yield insightful comparisons between the models.

CDM achieves an excellent fit to the Pantheon+ data, with a reduced chi-squared . It predicts a universe age of 13.81 Gyr and a present-day deceleration parameter . This serves as our benchmark for a successful cosmological model.

This version of Timeflow Gravity, initialized with the same matter density as CDM, also provides a very good fit to the supernova data, with . While statistically slightly less preferred than CDM according to this dataset, it demonstrates that the theory naturally produces an accelerating expansion consistent with observations. It predicts a slightly older universe than CDM at 14.17 Gyr and a gentler present-day acceleration with .

Matter-Only GR model is strongly disfavored by the data, yielding a much poorer fit with . Its prediction of a decelerating universe () and a significantly younger age (9.68 Gyr) is inconsistent with the supernova observations, reaffirming the need for a mechanism driving cosmic acceleration.

As the

Figure 1 clearly demonstrate, both

CDM and the empirical TG model successfully reproduce the cornerstone observation of modern cosmology—the late-time accelerated expansion, standing in stark contrast to the Matter-Only GR model. The ability of the TG framework to achieve this using

as its sole input, with the acceleration that naturally emerges from its thermodynamic principles, highlights its potential. Furthermore, the TG model provides a compelling physical explanation for the overly massive galaxies observed at high redshift by JWST

Boylan-Kolchin (2023),

Labbé et al. (2023), as its modified dynamics can accelerate structure formation in the early universe.

However, it must be emphasized that these initial tests using only supernovae are intended to establish the theory’s plausibility. A full, rigorous comparison will require a detailed statistical analysis against the complete cosmological datasets, including the Cosmic Microwave Background anisotropies from Planck and Baryon Acoustic Oscillation measurements from large-scale galaxy surveys.

Nevertheless, the ability of this framework to match the fundamental features of cosmic evolution—while emerging from a deeper thermodynamic principle, provides strong evidence that Timeflow Gravity is a compelling alternative to the standard cosmological model.

13. Emergent Inflation

In this framework, the Big Bang is not an explosion in spacetime but the explosion of spacetime itself. The conservation constraint,

acts as the trigger for the universe’s birth. Inflation then appears as the only self-consistent solution once the perfect symmetry of the vacuum is broken.

Before matter or radiation existed (

), the universe could in principle remain in a trivial static state with

This satisfies the constraint, but such a perfectly symmetric vacuum is unstable

Linde (1982) to quantum fluctuations. Any disturbance creates a small curvature or expansion, forcing the system away from

.

The conservation law can be expanded as

By the Bianchi identity,

, so it reduces to

This admits two possibilities: 1.

(flat spacetime, unstable vacuum), or 2.

(constant

, hence constant

H).

The second case requires

which makes

constant and the constraint identically satisfied. A constant

H corresponds to de Sitter space with

that is, exponential inflation.

This provides a natural mechanism for the originate of the universe. The universe bursts into existence and inflates exponentially

Starobinsky (1980),

Guth (1981) because this is the only way it can obey its own most fundamental conservation law.

The intense curvature of the de Sitter phase will inevitably lead to quantum particle creation from the vacuum itself, a process analogous to reheating in standard inflationary models. As soon as particles are created, a non-zero matter component appears ().

The presence of this new matter component fundamentally alters the dynamics. The universe must now obey the full Timeflow Gravity field equation Equation (

51)

The perfect symmetry of the vacuum solution is now broken by the matter source term on the right-hand side. The Hubble parameter is no longer required to be constant. Instead, the presence of the newly created matter and radiation acts as a dynamic "friction" that causes the expansion rate to decrease slowly over time. The deceleration parameter, , which was exactly during the pure de Sitter phase, now becomes slightly greater than .

This slow decrease in the Hubble parameter,

, is the definition of a quasi-de Sitter inflation

Linde (1983). The TG framework thus contains a built-in, natural mechanism to transition from a pure exponential expansion to the slow-roll phase required for a successful inflationary model.

The transition to a quasi-de Sitter phase is a critical prediction that makes the theory consistent with high-precision cosmological data from observers like the Planck satellite

Aghanim et al. (2020). The small deviation from a perfect de Sitter expansion results in a spectrum of primordial density fluctuations that is nearly, but not perfectly, scale-invariant. This leads to a predicted scalar spectral index,

, that is slightly less than one (

), in excellent agreement with the values measured from the Cosmic Microwave Background.

The existence of the universe and its initial inflationary epoch are not two separate events in this framework, but a single, continuous process. The universe emerges in a pure de Sitter state, which is inherently unstable and naturally decays into a quasi-de Sitter phase through particle creation, setting the stage for the subsequent hot Big Bang era.

14. The Big Crunch and a Cyclic Universe

The principles of Timeflow Gravity, when taken to their logical conclusion, predict that the universe is not destined for eternal expansion, but rather follows a cosmic cycle of expansion and collapse.

The Law of Entropy Equilibrium states that the universe maintains a dynamic balance between its thermodynamic entropy (chaos) and its negentropy of order Equation (

19)

The entropy of order,

, is a finite and bounded quantity. This negentropy reaches its absolute minimum,

, in the far future when all baryonic matter has collapsed into black holes, representing the state of maximum possible order. At this point, the "drive for order" is exhausted, and the rate of change of the entropy of order becomes zero:

The dynamic form of the equilibrium law,

, therefore forces the universe into a state where the total rate of change of thermodynamic entropy must also be zero:

However, at this late epoch, the dominant physical process is the evaporation of black holes via Hawking radiation. This process continuously generates new thermodynamic entropy, meaning its contribution is always positive:

This creates a direct conflict with the stasis condition required by Eq. Equation (

76). To resolve this, the universe must initiate a new physical process that generates negative entropy to precisely balance the positive entropy from Hawking radiation. The only available mechanism is a change in the geometry of spacetime itself.

The total thermodynamic entropy of the cosmos is the sum of the entropy generated by local processes (like Hawking radiation) and the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy of the cosmological event horizon,

. The equilibrium condition thus becomes:

This implies that the change in the horizon’s entropy must be negative:

The entropy of the cosmic horizon is proportional to its area, which is inversely proportional to the square of the Hubble parameter: . For the rate of change of this entropy to be negative, the area of the horizon must shrink. A shrinking cosmic horizon is the definition of a contracting universe.

This forces the Hubble parameter to slow its expansion, stop (), and then reverse sign (), initiating a rapid cosmic collapse. This "Big Crunch" is an emergent phenomenon, triggered by the universe’s need to maintain its fundamental law of entropy equilibrium against the disordering effects of black hole evaporation. This collapse resets the cosmos to a hot, dense state, providing the initial conditions for a subsequent Big Bang and establishing an eternal cosmic cycle.

15. Dark Energy Problems

The framework of Timeflow Gravity provides a natural resolution to the cosmological problem

Weinberg (1989), one of the most profound puzzles in modern physics. The problem consists of two parts: the vacuum catastrophe

Adler et al. (1995) (why is the observed vacuum energy

times smaller than the value predicted by Quantum Field Theory) and the cosmic coincidence

Zlatev et al. (1999) problem (why is the density of vacuum energy today of the same order of magnitude as the density of matter). This theory resolves both without any fine-tuning.

15.1. The Vacuum Catastrophe

TG explains the vacuum catastrophe by invoking two foundational principles that redefine the relationship between gravity and vacuum energy.

First, the Time-Energy Equivalence Principle Equation (

4) asserts that gravity, as an emergent thermodynamic phenomenon, does not couple to the absolute potential of the Timeflow field (

), but only to its gradients (

) Equation (

7). The enormous vacuum energy density predicted by Quantum Field Theory,

, corresponds to a massive but uniform baseline potential,

. As this background is spatially constant, its gradient is zero:

Consequently, the raw QFT vacuum energy is gravitationally inert. This principle alone severs the problematic link between standard QFT predictions and gravitational dynamics, explaining why the observed vacuum energy is not catastrophically large.

Second, the Law of Entropy Equilibrium Equation (

19) explains the origin and magnitude of the observed dark energy. As gravity forms structures throughout cosmic history, the entropy of order (

) becomes more negative. To maintain the zero-entropy balance, the universe must generate a corresponding amount of thermodynamic entropy (

). The theory posits that the observed dark energy is precisely the emergent energy required to drive cosmic expansion at a rate that produces the necessary horizon entropy to satisfy this law. The effective vacuum energy density,

, is therefore not a fundamental constant but a dynamic thermodynamic response of the cosmos, whose value is dictated by the need for cosmic balance.

15.2. The Cosmic Coincidence

The standard cosmological model (CDM) offers no explanation for why the energy density of matter () and the energy density of the vacuum () are of the same order of magnitude today. In this theory, this "coincidence" is a direct and necessary consequence of the field equations.

From the derivation of the effective stress-energy tensor of the vacuum Equation (

53), we have:

This equation shows that the effective vacuum energy (

) is not an independent, constant entity like the cosmological constant

. Instead, it is a dynamic quantity that is directly and inextricably linked to the presence of matter (

).

The vacuum energy in this model is a thermodynamic response of the Timeflow field to the presence of matter. It is therefore no coincidence that their energy densities are comparable today; the theory demands that they be fundamentally related at all times. By reframing gravity as an emergent thermodynamic process, the theory resolves both aspects of the vacuum energy problem.

16. Evolving Dark Energy

Recent observational evidence from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) collaboration suggests that the density of dark energy is not constant, but is slowly decreasing over cosmic time

Cortês and Liddle (2024),

Efstathiou (2025). While this finding presents a significant challenge to the standard

CDM model, which is built upon a static Cosmological Constant (

), it serves as powerful corroborating evidence for the TG framework. This evolving behavior is a direct and inevitable consequence of its most fundamental principles.

The key difference from the standard

CDM model is that in TG, "dark energy" is not a fundamental, constant energy of the vacuum. Instead, it is an emergent thermodynamic effect that is dynamically sourced by matter. This is captured in the theory’s central equation for the effective vacuum energy density,

, which is inextricably linked to the matter density,

:

Here, the thermodynamic function

represents the efficiency of the vacuum’s response to the presence of matter at a given cosmic epoch,

z. This equation establishes that the existence of the effective dark energy is not independent, but is a direct consequence of the existence of matter.

This direct coupling to matter is the definitive reason why the dark energy density must decrease over time. The evolution of is governed by a competition between two opposing trends: the relentless dilution of its source, , and the slowly increasing efficiency of the vacuum’s structural response, given by the factor .

The crucial physical insight is that the dilution of the source is the dominant effect. We can demonstrate this by comparing the dark energy density today (

) with its value in the past at

. According to the cosmological solution of this theory, the thermodynamic function at these epochs is approximately

and

. We can therefore calculate the ratio of the dark energy density at

to its value today:

This calculation demonstrates a firm prediction: the effective density of dark energy was approximately twice as high at z=1 as it is today. As the universe evolves and matter thins out, its ability to induce this vacuum energy effect weakens, causing the overall dark energy density to decrease.

The principle is simple and intuitive: dark energy is like the "heat" generated by the "work" of cosmic matter. As the work dies down with cosmic evolution, the heat it produces must also dissipate. This is in stark contrast to CDM, where dark energy is a constant background temperature that never changes.

A finding that is decreasing today is therefore a natural and necessary prediction of the TG framework. For the standard model, it would require new physics to explain; for Timeflow Gravity, it is simply the theory working as expected.

17. The Hubble Tension

The Hubble Tension

Di Valentino et al. (2021) arises from the discrepancy between the Hubble constant measured in the late, local universe (

km/s/Mpc)

Riess et al. (2022) and the value inferred from the early universe via the Cosmic Microwave Background (

km/s/Mpc)

Aghanim et al. (2020). In the Timeflow Gravity framework, this tension is not a contradiction but a fundamental prediction that stems from the different physical natures of cosmic acceleration in TG versus the standard

CDM model.

The core difference lies in the source of acceleration. In CDM, the expansion is driven by the cosmological constant, , which represents a static, constant energy density of the vacuum. Its contribution to the Friedmann equation is independent of redshift. In contrast, the TG model’s acceleration is driven by the thermodynamic function , which is a dynamic, evolving quantity that depends on the state of the universe.

Let’s compare the Friedmann equations for the two models:

We can analyze the behavior of these two distinct cosmic histories at different epochs:

In the Early Universe () in both models, the matter density term, which scales as , becomes overwhelmingly dominant. In CDM, the constant term becomes negligible compared to the matter term. In the TG model, the high matter density forces to be very large, which in turn causes the thermodynamic function to approach unity ().

As a result, both equations converge to the same functional form for a matter-dominated universe: . Because the two models become physically indistinguishable in this early epoch, any measurement of cosmic parameters from the CMB and their extrapolation to the present day will necessarily differ from measurements made in the local, modified-gravity regime.

In the Late Universe () the two models diverge significantly. The constant energy density of drives a strong, exponential acceleration. In the TG model, the acceleration is gentler, governed by the value of as it deviates from unity. The local physics, tied to the MOND acceleration , is in a complex, non-linear relationship with the global expansion. The “tension” is the measurable signature of this difference. It is the discrepancy between the true, local expansion rate driven by the thermodynamics of the present-day vacuum, and the extrapolated value from an early universe that behaved according to a simpler, matter-dominated rule.

Therefore, the Hubble Tension is a key prediction of Timeflow Gravity. It is the observational evidence of the transition from a standard, matter-dominated cosmic history at high redshift to a thermodynamically modified, non-linear history at low redshift.

18. Falsifiability

A scientific theory must be testable, and its predictions must be capable of being confronted with observation in a way that allows for clear falsification. The Timeflow Gravity framework leads to several distinct, quantitative predictions that differ from both CDM and other modified gravity models. Here I highlight three such predictions that are particularly accessible to current and near-future observational programs.

18.1. No Free Parameter Cosmic Expansion

The most direct prediction of this theory is that the laws governing galaxies and the laws governing the cosmos are two sides of the same coin. This allows for a simple, parameter-free test.

The idea is based on the fundamental connection between the critical scales of the two laws. The thermodynamic derivation shows that the critical acceleration for gravity,

, and the critical expansion rate for cosmology,

, are not independent. They are two manifestations of the same underlying critical temperature of spacetime,

, and are related by the speed of light Equation (

27).

We take the well-established value of the MOND constant, , which is measured from the rotation curves of hundreds of nearby galaxies. We use the fundamental relationship to make a direct, a priori calculation for the present-day Hubble constant, . We then take this single predicted value of and use it in the cosmological equations to generate a complete cosmic expansion history. We can then compare this directly against the CMB and supernova dataset, to see if the law measured in galaxies is the same law that created the cosmos and provide comparable results to the standard CDM model.

18.2. The Apparent Evolution of and the Cosmic External Field Effect

A crucial prediction of Timeflow Gravity is the distinction between the fundamental MOND acceleration scale, , and the effective scale, , that would be measured by an observer at a given cosmic epoch z.

The quantum derivation (

36) established that

is a true, unchanging constant of nature, a fundamental property of the modern vacuum. However, the measurable MOND threshold for any galaxy is subject to the theory’s own External Field Effect (EFE). The effective scale

is the sum of the fundamental vacuum “floor” (

) plus the background acceleration from the entire cosmos,

.

In the dense, early universe, the background acceleration from the cosmic matter density was enormous, completely “drowning out” the tiny, fundamental

:

The Hubble parameter

is a direct measure of the total energy density of the universe at epoch

z, and thus serves as the correct proxy for this total background field. The thermodynamic equilibrium condition relates the total effective scale

to the total Hubble expansion

:

This equation describes the evolution of the measurable, effective MOND threshold over cosmic time. We can derive an explicit expression for this evolution by substituting our solution for the Hubble parameter,

, from the First Modified Friedmann Equation:

where

.

This leads to a clear and testable prediction. In the matter-dominated early universe (

),

was enormous, and therefore the effective MOND scale was also enormous, scaling as:

This implies that MOND-like effects were heavily suppressed in the early universe. Gravity behaved classically down to much lower accelerations because the universe itself provided a massive external field.

As the universe expanded and cooled,

decreased, and the background acceleration

faded away. The effective scale

decreased along with it, eventually “settling” at its irreducible minimum value. This minimum is the fundamental, constant floor of the vacuum itself, which we measure today (

):

This unifies the theory’s predictions. The quantum derivation of (Section V) calculates the final, ground-state “room temperature” of the modern vacuum, while this cosmological derivation describes the “cooling” of the effective MOND scale from its hot, dynamic, matter-driven past. High-redshift rotation curve measurements of disk galaxies provide a direct means of testing this predicted evolution.

18.3. The Active Repulsion of Cosmic Voids

In Timeflow Gravity, the faster rate of time in underdense regions creates a dynamically enhanced repulsive gravitational effect. This “active repulsion” is a direct consequence of the entropy-equilibrium law, which leads to steeper curvature gradients across void boundaries. This predicts a measurable increase in the weak gravitational lensing signal produced by cosmic voids compared to the standard CDM model.

The enhancement arises from the theory’s effective gravitational coupling Equation (

47). Since the gravitational lensing potential is proportional to the gravitational constant, the lensing shear (

) predicted by Timeflow Gravity (TG) is enhanced by a factor of

relative to General Relativity (GR):

The value of

is determined by the total gravitational acceleration, which, due to the External Field Effect (EFE), is dominated by the background field from the cosmic web,

, rather than the void’s negligible internal field. For the typical range of external fields found in the environments of large voids,

, we can calculate the predicted enhancement using the function

, where

.

For a stronger external field of

, the enhancement factor is:

For a weaker external field of

, the enhancement factor is:

Therefore, the theory makes a firm prediction of a 1.5x to 2.0x enhancement in the tangential shear amplitude produced by cosmic voids. This provides a clean observational test to distinguish Timeflow Gravity from

CDM, where no such environmental enhancement is expected.

19. Future Directions

The aim of this theory has been to demonstrate that the thermodynamic and informational principles underlying the Timeflow Gravity framework are sufficient to unify the galactic-scale anomalies and the accelerated cosmic expansion without introducing arbitrary free parameters.

However, to fully account for complex astrophysical phenomena, the theory must be expanded beyond its current static limits. The next crucial step is to develop a full fluid dynamics for the Timeflow field. Treating spacetime as a dynamic medium with properties like pressure and inertia would allow it to transport energy and momentum. This provides a compelling, alternative explanation for observations like the Bullet Cluster

Clowe et al. (2004),

Markevitch et al. (2004), where the apparent separation of mass and gravitational lensing could be interpreted not as evidence for collisionless dark matter, but as a hydrodynamic effect in the Timeflow fluid itself during the violent galactic collision.

For now the theory in its current state is classical and macroscopic in nature. The next stage of development must focus on building a rigorous Lagrangian density for the Timeflow field, from which the field equations can be derived via the action principle and which allows for a consistent coupling to matter and radiation. Such a formulation holds the potential to resolve the black hole singularities and will be a necessary prerequisite for quantizing the theory, opening the door to a complete framework of quantum gravity grounded in the same thermodynamic principles.

20. Conclusions

General Relativity and CDM have been remarkably successful, providing a powerful mathematical description of gravity and the universe’s large-scale evolution. However, their success relies on the introduction of two major, unexplained components: dark matter and dark energy. These are essentially placeholders for observed gravitational effects that cannot be accounted for by the visible matter in the universe. While CDM describes what happens with incredible precision, it does not explain why these phenomena occur.

Timeflow Gravity offers a different perspective. Instead of adding new, unseen substances to the cosmos, it proposes a new physical principle: that gravity is not a fundamental force, but an emergent thermodynamic phenomenon arising from a single quantum scalar field—the Timeflow field. This shift from a descriptive to an explanatory framework provides a physical origin for the universe’s most profound puzzles.

Where CDM requires dark matter to explain galactic rotation, TG derives the MOND acceleration scale () and the associated galactic scaling laws (Tully-Fisher, RAR) directly from the thermodynamics of causal horizons. Where CDM requires dark energy to explain cosmic acceleration, TG predicts the Hubble constant from the fundamental transition rate of the quantum vacuum, simultaneously resolving the 120-order-of-magnitude vacuum energy problem. Timeflow Gravity offers a compelling solution to the emerging puzzles from recent JWST observations, as an enhanced effective gravitational constant () in the early universe naturally accelerates the formation of massive galaxies. TG respects the law of energy conservation—an important theoretical advantage over General Relativity. Even the puzzling Hubble tension and evolving dark energy find a natural explanation as a measurement of the universe in two different thermodynamic states. Finally, the theory’s thermodynamic foundation presents a new avenue for explaining the universe’s initial conditions, providing a mechanism for an inflationary-like epoch without requiring a separate inflaton field.

With just a single, minimal modification of General Relativity, Timeflow Gravity accounts for the phenomena attributed to dark matter, dark energy, and inflation within one unified framework. In this sense, TG could be not only more economical than the standard model, but also more predictive, offering testable explanations where CDM introduces additional entities. This suggests that treating gravity as an emergent property of a Timeflow field may represent a significant step towards a more fundamental and complete theory of the cosmos.

A particularly interesting feature of this approach is the environment-dependent drive of energy to preserve ordered states. This principle may extend far beyond gravitation alone, potentially offering a universal mechanism for the emergence of complex structures. From the stability of particles, to the formation of galaxies, and even to the rise of biological life, the same thermodynamic law could be at work: the tendency of spacetime to sustain order against the backdrop of entropy.

This unification opens a path toward a deeper theory of reality, where matter, gravity, space and time are not isolated phenomena but representations of one continuous thermodynamic process. Timeflow Gravity therefore holds the potential not only to resolve the puzzles of dark matter and dark energy, but also to illuminate the fundamental principles that shape the evolution of the Universe.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Rinat Nugayev, Sergei D. Odintsov and Tanmoy Paul for support and valuable feedback.

References

- Di Valentino, E., O. Mena, S. Pan, L. Visinelli, W. Yang, A. Melchiorri, D.F. Mota, A.G. Riess, and J. Silk. 2021. In the realm of the Hubble tension—a review of solutions *. Classical and Quantum Gravity 38: 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan-Kolchin, M. 2023. Stress testing ΛCDM with high-redshift galaxy candidates. Nature Astronomy 7: 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, I., P. van Dokkum, E. Nelson, R. Bezanson, K.A. Suess, J. Leja, G. Brammer, K. Whitaker, E. Mathews, M. Stefanon, and et al. 2023. A population of red candidate massive galaxies 600 Myr after the Big Bang. Nature 616: 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortês, M., and A.R. Liddle. 2024. Interpreting DESI’s evidence for evolving dark energy. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2024: 007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]