Appendix A. Derivation of the Λ-Scale

We build natural units from

by writing any target unit

X as a monomial

with exponents

to be determined from dimensional balance in base units

(cf. Planck’s 1899 dimensional construction; here extended to include

[

16]):

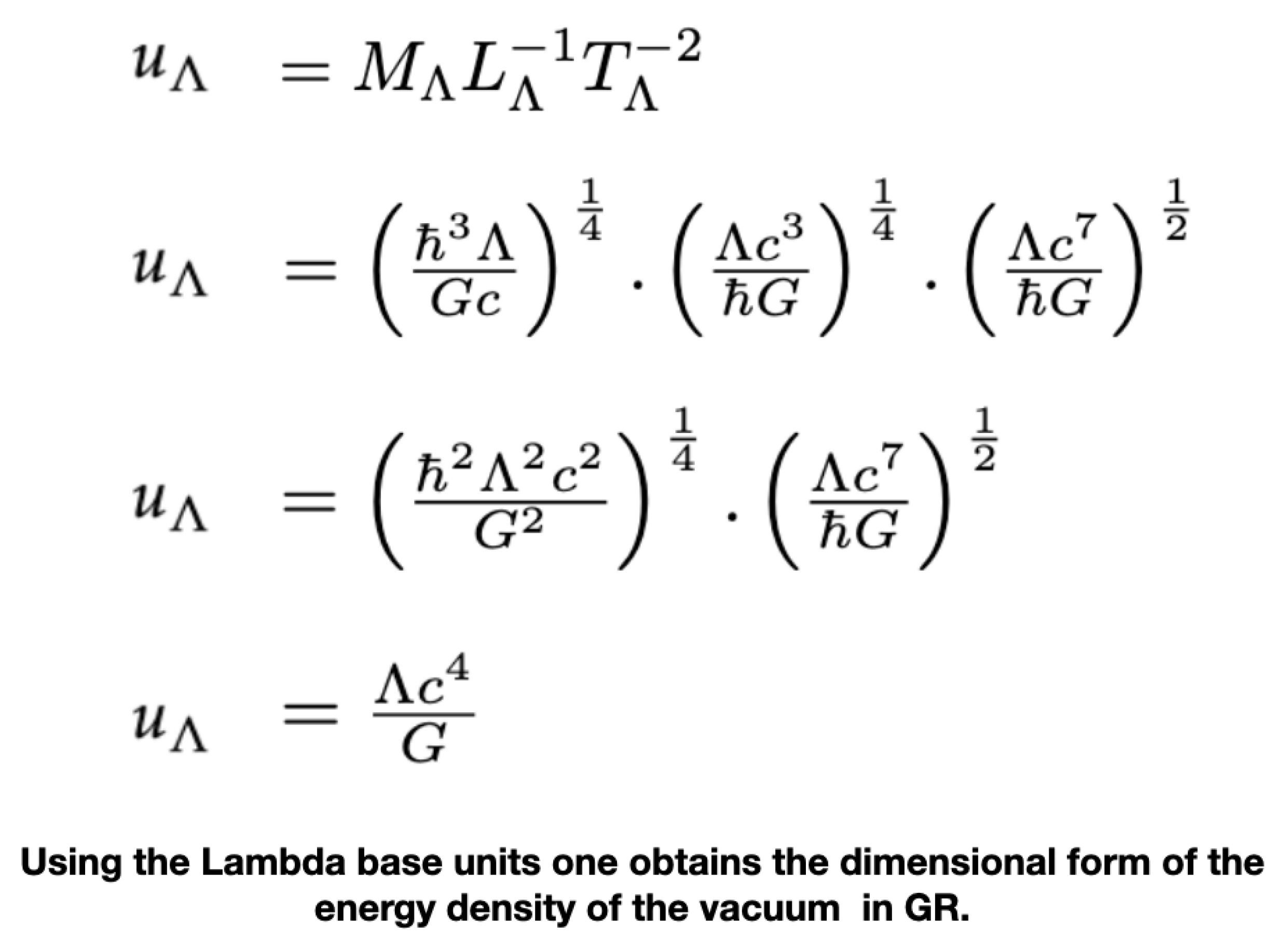

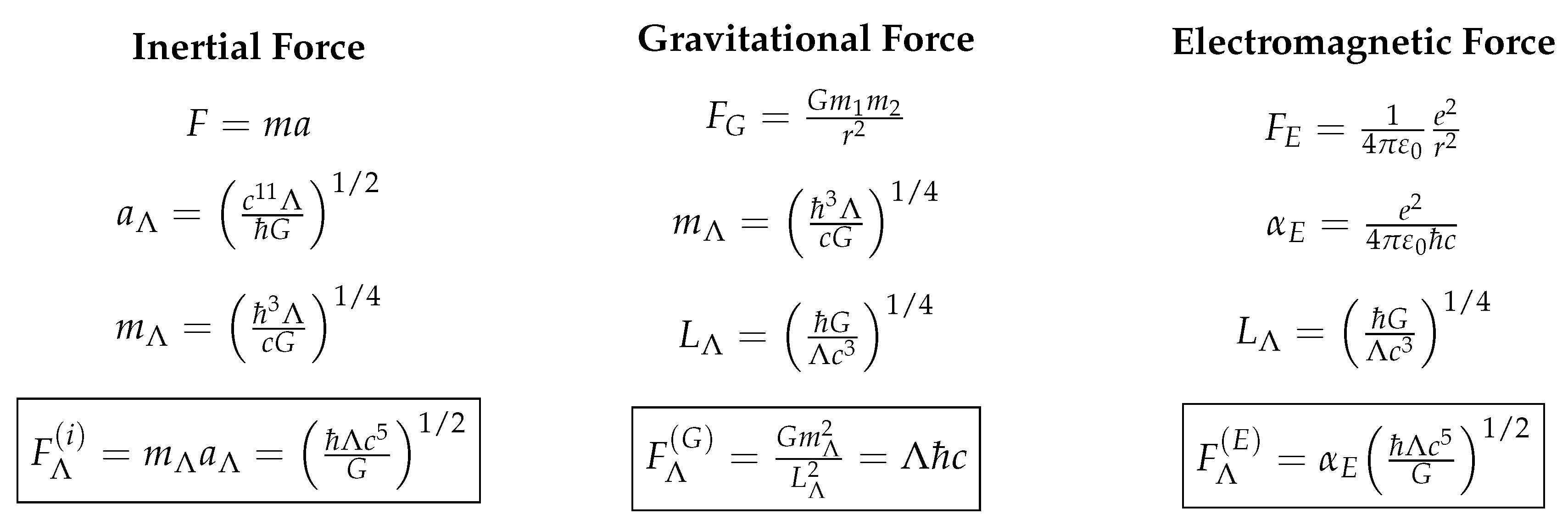

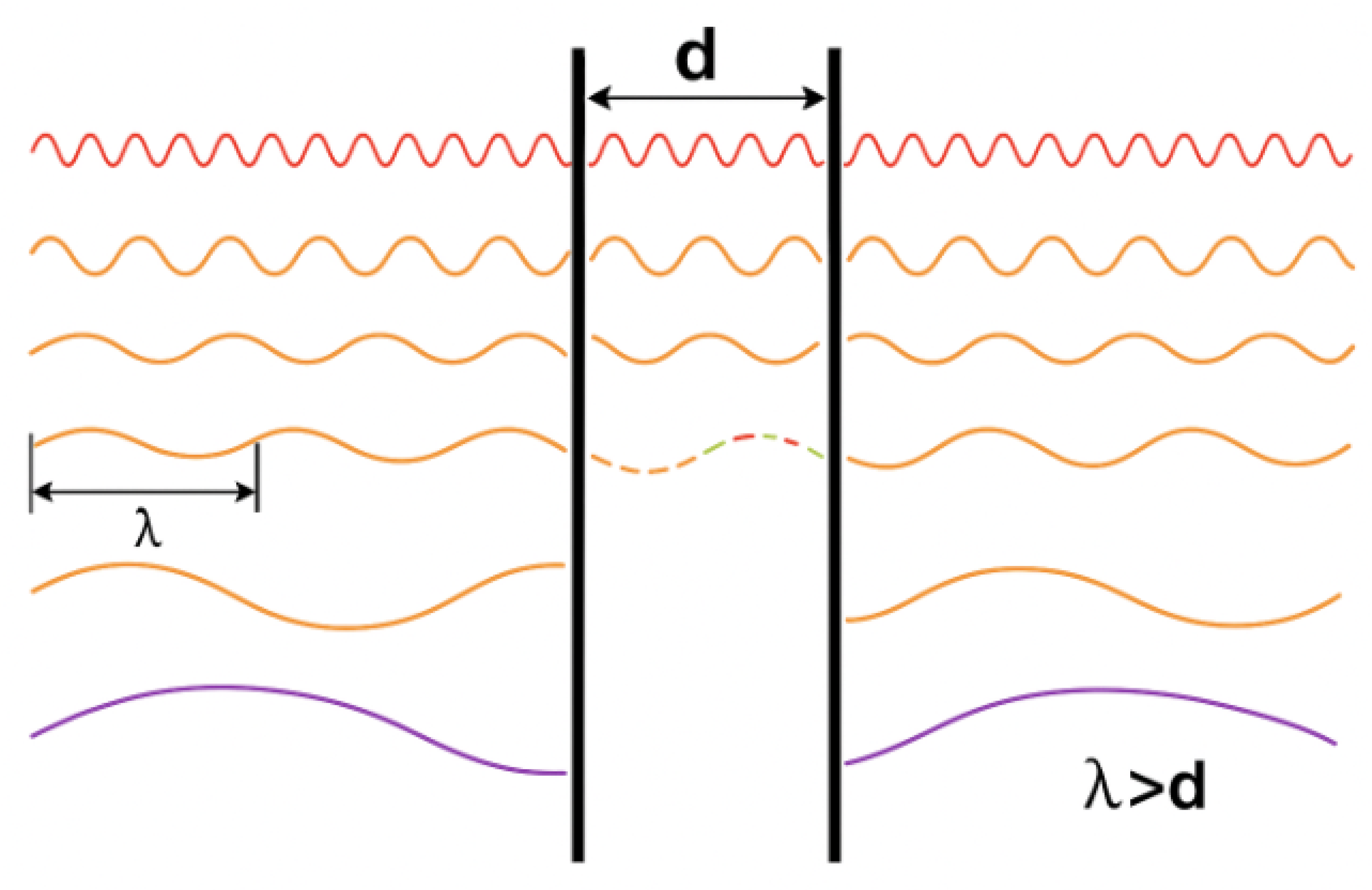

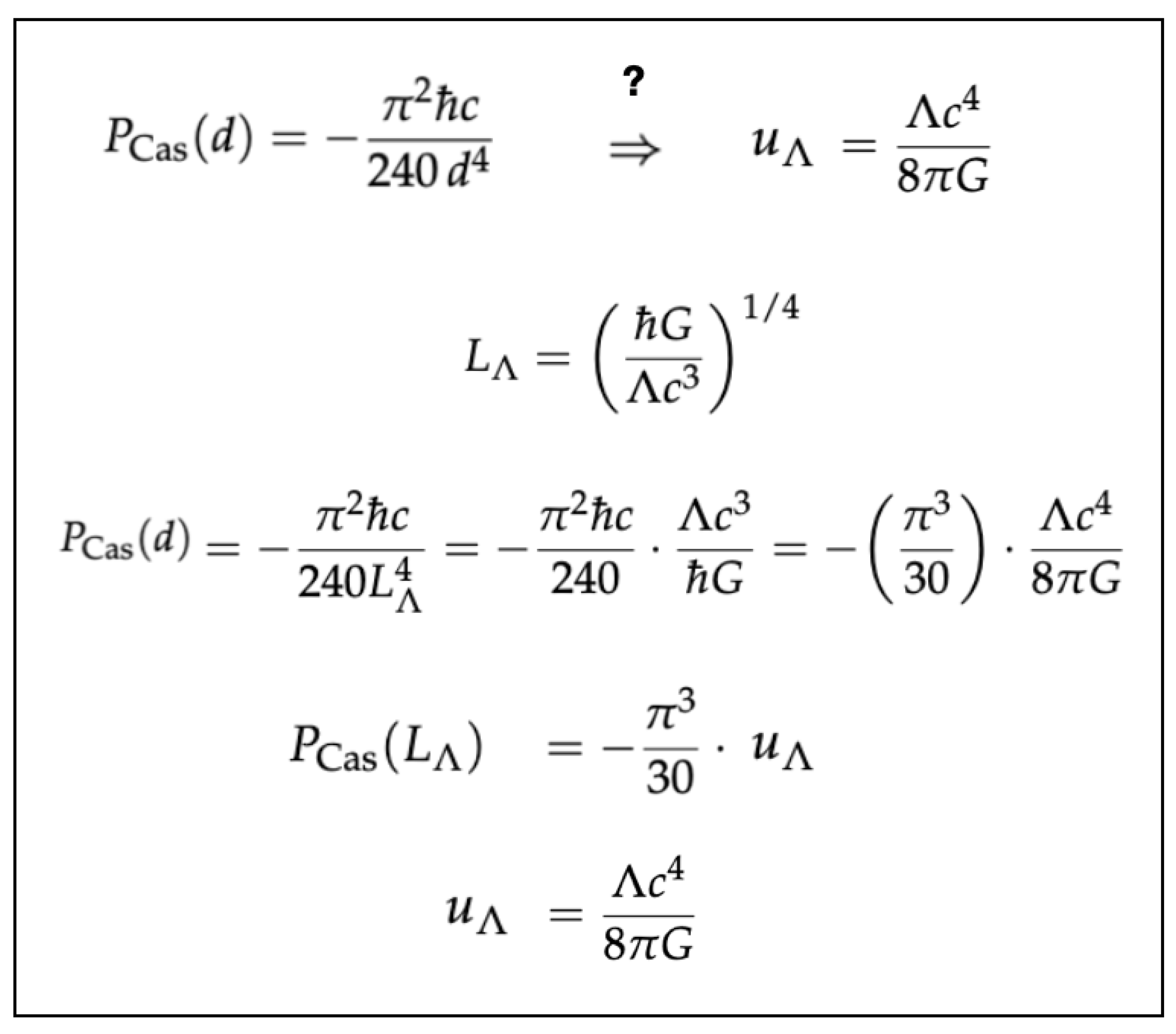

Hence the dimension of

is

The three exponents are exactly the three linear forms that will become the rows of the matrix in the formal derivation.

For a length unit we require

, i.e.

Thus the general solution is a one-parameter family

Two instructive choices:

For a time unit we require

, hence

So the family is

Two instructive choices:

For a mass unit we require

, i.e.

Therefore

Two instructive choices:

By–inspection solutions (one–parameter families). For the required exponents for the base units are:

Two instructive choices.

|

The three blocks above are the three row-constraints we shall later collect into the matrix. Solving each target dimension exposes the same one-dimensional affine freedom: dimensional analysis alone leaves a free parameter p (a nullspace direction). In practice, this means there is a whole family of possible “natural units.” Choosing reproduces the Planck units, while yields the -units with their characteristic quarter-powers.

This inspection method already shows that dimensional analysis by itself cannot uniquely fix the scale: the affine parameter simply shifts weight among

. To determine which member of the family Nature selects, one must go beyond inspection. [

16,

70].

Appendix A.1. Deriving and Fixing the Λ-Unit System

To formalize the inspection analysis above, we now write out the dimensional algebra explicitly. Using our four constants are defined in (A2), we consider a monomial

and demand

. Matching exponents of

gives the linear system

This

matrix has rank 3, hence a

1-dimensional nullspace. A basis vector is

Therefore any particular solution

can be shifted by

for arbitrary

:

Dimensional analysis leaves the affine family (A13).

Physics fixes λ by the vacuum–matching postulate (QFT cutoff = GR vacuum):

In exponent space (order

) this requires

so the unique length exponents are

With the kinematic anchors

and

this yields

Conclusion: with

as bases and four constants

, every target dimension has a

1-parameter family of exponent quadruples. This is the mathematical origin of the “infinitely many

”.

Appendix A.2. Planck, Stoney, and Λ as “nullspace + anchors”

A unit system becomes

unique once we add enough

physical anchors to kill the nullspace freedom(s). With the vacuum matching (A14) selecting

, the dimensionless values of the constants in

-units are summarized in

Table A1.

Table A1.

Dimensionless values in -units. Anchors enforce . Vacuum matching selects the symmetric point, yielding and , where is the GFSC.

Table A1.

Dimensionless values in -units. Anchors enforce . Vacuum matching selects the symmetric point, yielding and , where is the GFSC.

| Constant |

Base dimensions |

in -units |

Note |

| c |

|

1 |

anchor

|

| ℏ |

|

1 |

anchor

|

| G |

|

|

paired with ; product fixed |

|

|

|

symmetric with

|

Planck units {G, ℏ, c} [

16].

Here constants for 3 bases no nullspace. Uniqueness comes for free once we impose the usual identifications and .

Stoney units {G, c, e} (+ EM convention) [

71].

Relativity (), gravity (G), and an electromagnetic normalization (choice of Coulomb constant / rationalization) fix the set. One recovers and a natural charge/action scale (e.g. in SI) by construction.

Now

for 3 bases ⇒

one free parameter (the

in (A13)). Two standard anchors are kept:

A

single -specific anchor removes the remaining freedom:

This fixes the length scale uniquely:

Thus the -triple is unique once (A18) is adopted.

Equivalent algebraic symmetry. For length, write

. Solving (A11) for

gives the family

Imposing the simple

equal-weight symmetry (“give quantum and gravity equal weight, oppose

with equal magnitude”) yields

i.e. exactly (A19). This symmetry condition is just the exponent form of the vacuum matching (A18).

Appendix A.3. Why most choices do not return c and ℏ

Because

live on the affine line (A31), generic choices give

The anchors (A17) pick out the subfamily consistent with relativity and quantum kinematics; the

-anchor (A18) then selects

one point on that subfamily—giving (A19). This mirrors explicit counterexamples: other valid exponent choices produce a different velocity scale and a different action scale.

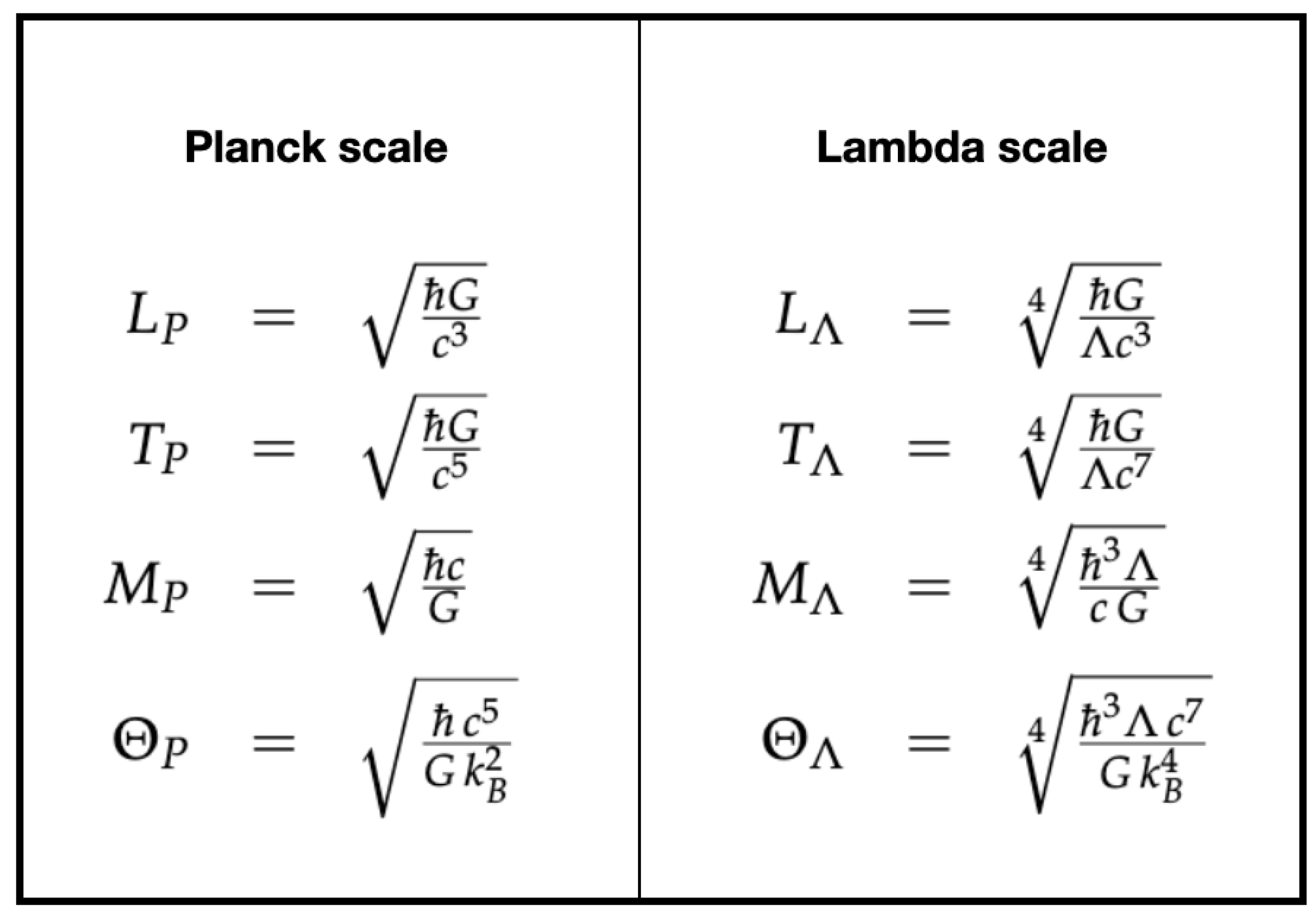

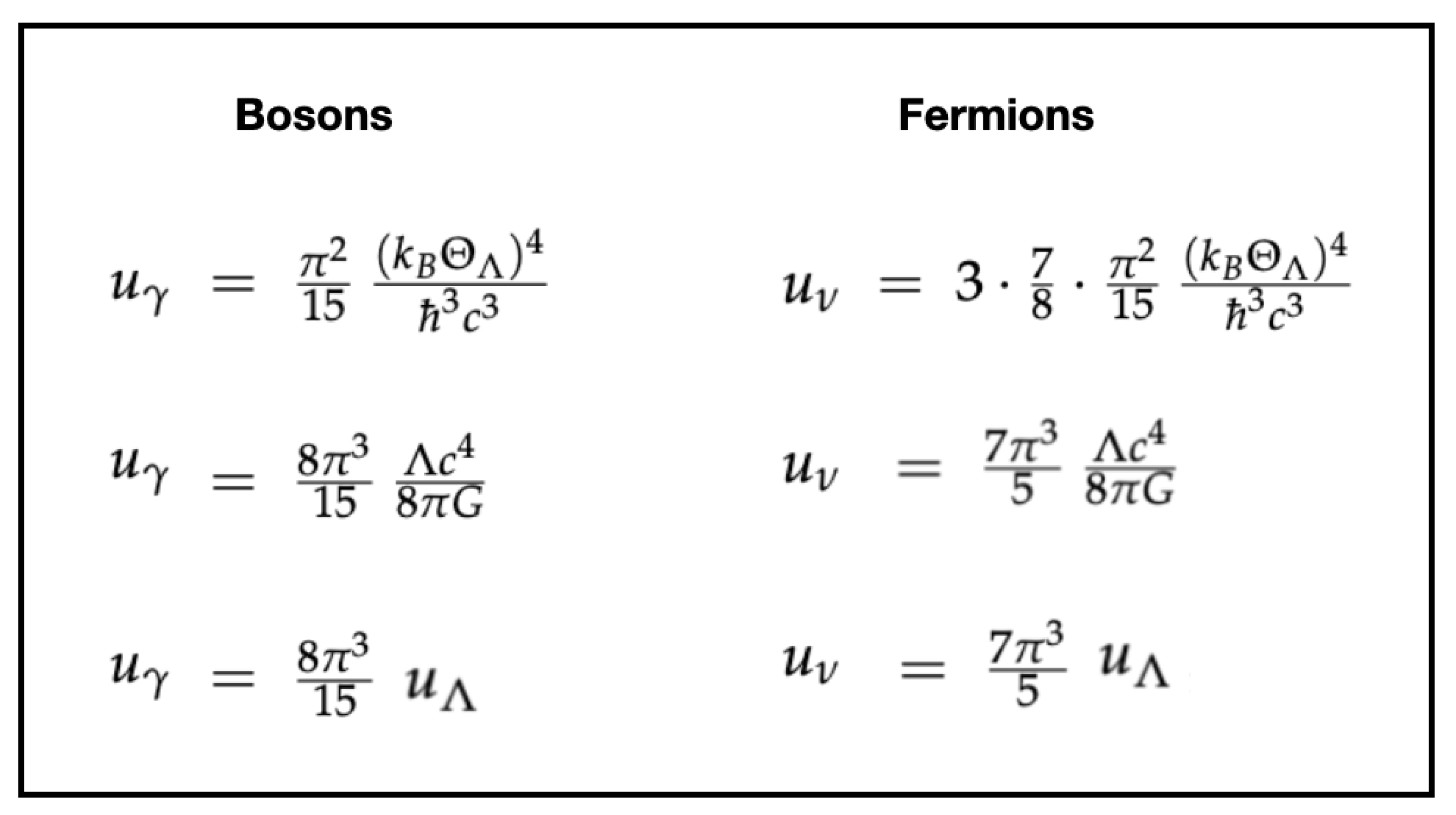

Appendix A.4. Temperature and kB

Historically, Planck [

16] introduced a

fourth base dimension and used

to tie temperature to energy. Two consistent options:

-

With (four bases ). Add

. Then a natural

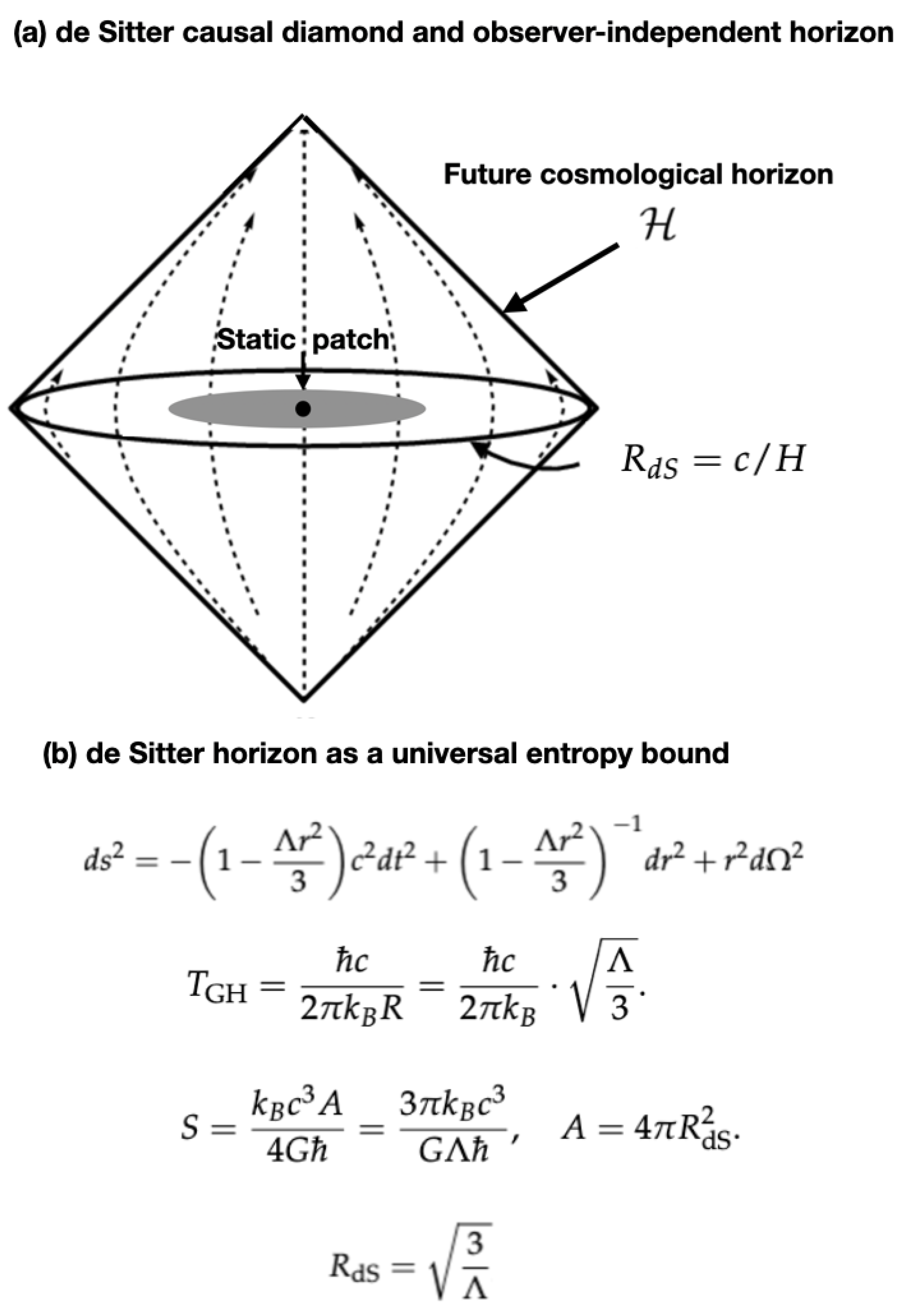

-temperature follows from horizon thermodynamics:

Up to order-unity factors, this is the de Sitter/Gibbons–Hawking scale.

Without (modern HEP convention). Set so temperature is measured in energy; is not an independent base dimension and (A19) suffices.

Appendix A.5. Practical “algorithm” (no trial & error)

Write the dimensional matrix (A11); solve once to get a particular solution and the null vector .

Enforce the two standard anchors (A17) so that unit speed is c and unit action is ℏ.

Impose the single -anchor (A18) ⇒ fix the free parameter .

Read off the exponents for as in (A19); if using , define via (A22).

is dimensionless and

not set by units. One may choose EM conventions (e.g. Heaviside–Lorentz [

27,

72,

73]) so that

is absorbed, but the

-unit

uniqueness rests entirely on the mechanical anchors plus the

-postulate, not on EM conventions.

Therefore: Admitting as a fundamental constant introduces one nullspace degree of freedom in the dimensional algebra; a single, physically motivated vacuum-matching postulate removes it and yields a unique -scale. This both explains the infinity of formal solutions and why the physically relevant -triple emerges uniquely.

Table A2.

Comparison of natural unit systems. Enough anchors remove nullspace freedom.

Table A2.

Comparison of natural unit systems. Enough anchors remove nullspace freedom.

| System |

Constants used |

Base dims. |

Anchors imposed |

Unique outcome |

| Stoney (1881) |

(with ) |

|

(i) ; (ii) G; (iii) EM normalisation (Coulomb const.) |

Recovers and natural charge/action scale ( in SI) |

| Planck (1899) |

(opt. ) |

or

|

(i) ; (ii) ; (opt. iii) for

|

Unique ; with , Planck temperature

|

| -scale (present) |

(opt. with ) |

|

(i) ; (ii) ; (iii)

|

Unique ; with ,

|

Once are admitted, dimensional analysis alone leaves a one-parameter family of monomials. A single, physically motivated postulate—matching the QFT cutoff to the GR vacuum density—selects a unique member: the -scale. What looks like algebraic freedom is therefore resolved by thermodynamics, which also explains why the physically relevant -triple emerges uniquely.

Appendix A.6. The Λ Scale as a Geometric Mean

An elegant property of the

scale is that it lies midway, on a logarithmic scale, between the Planck length

and the de Sitter horizon radius

. This can be shown directly by inspection. Define the familiar quantities:

Taking the geometric mean of

and

gives

Hence,

If instead we adopt the common convention (dropping the factor ), then is exactly the geometric mean:

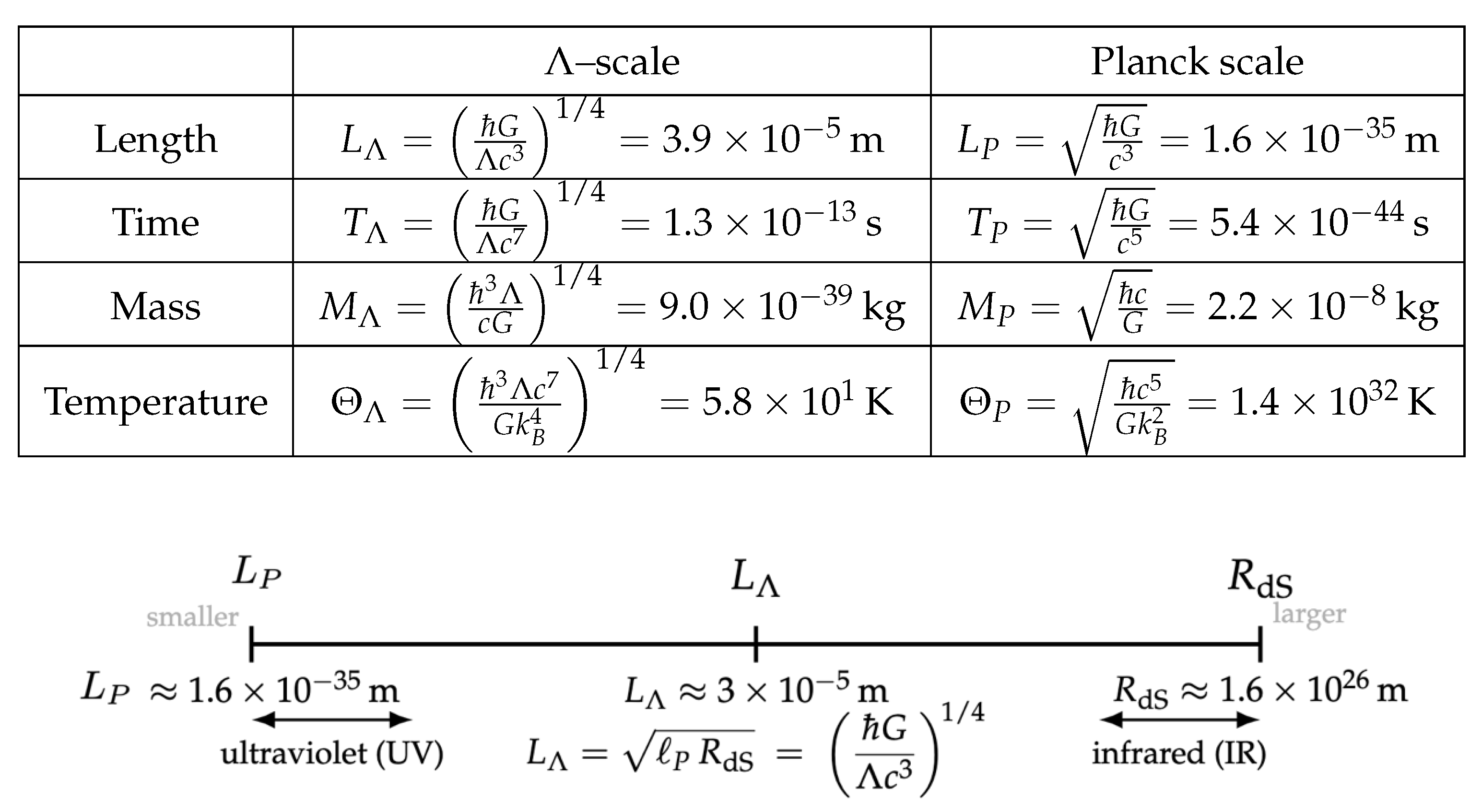

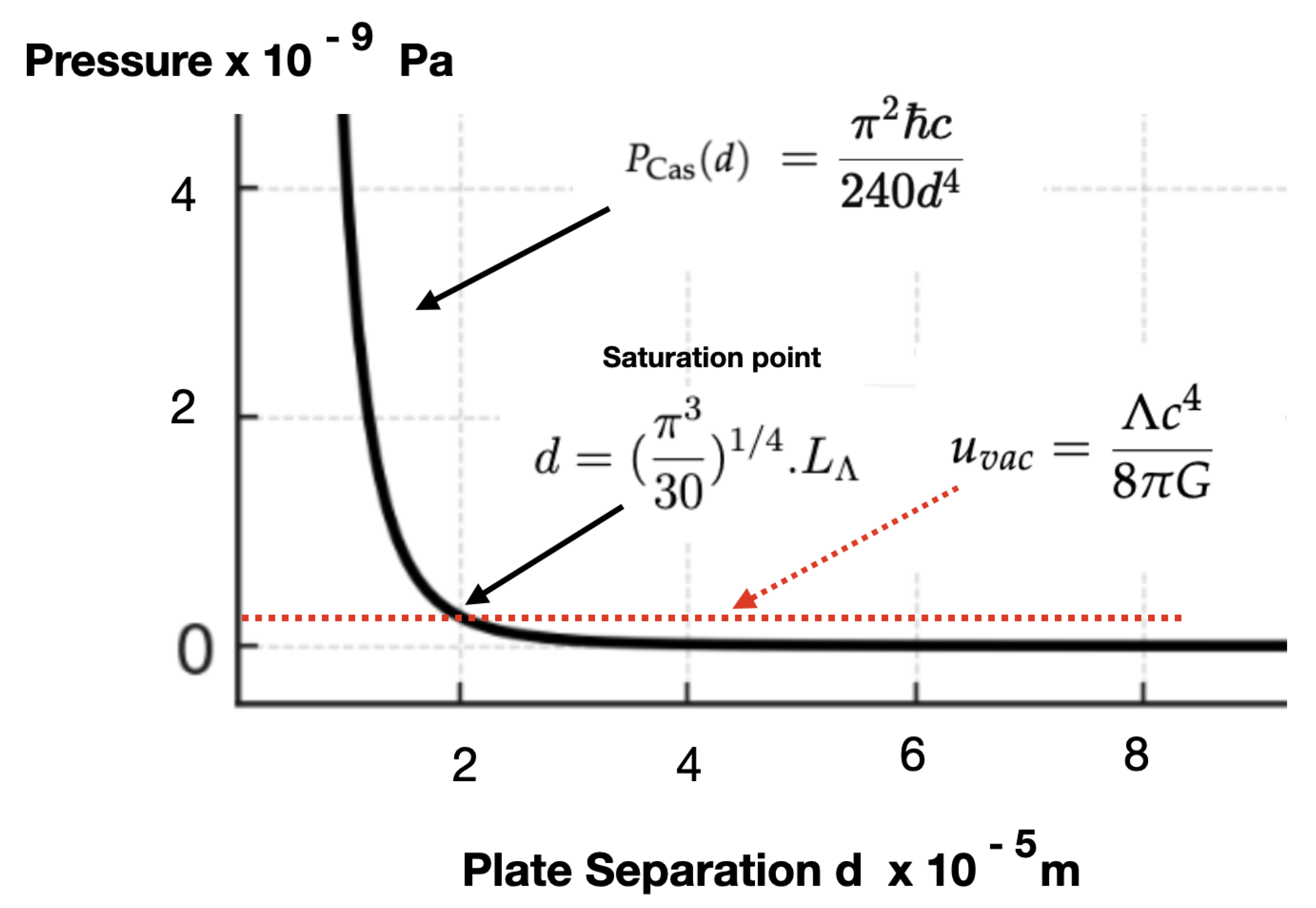

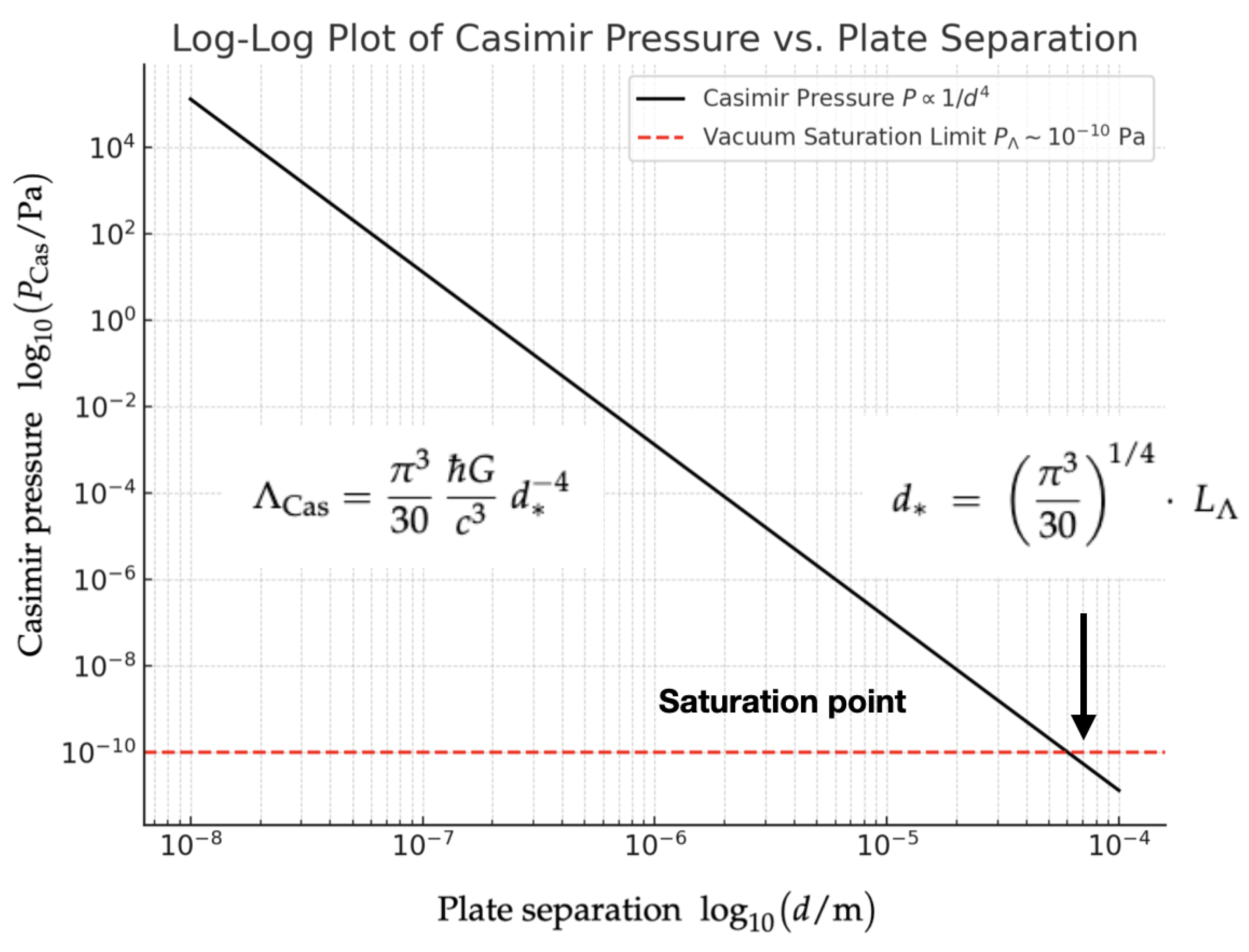

Figure A1.

Hierarchy of fundamental length scales. The Planck length anchors the UV, the de Sitter horizon anchors the IR, and the emergent –scale sits at the geometric mean, . Numerical values shown here are evaluated using CODATA values, with inferred from late–time cosmology.

Figure A1.

Hierarchy of fundamental length scales. The Planck length anchors the UV, the de Sitter horizon anchors the IR, and the emergent –scale sits at the geometric mean, . Numerical values shown here are evaluated using CODATA values, with inferred from late–time cosmology.

Appendix A.7. Dimensionless G and Λ in Λ–units and the role of αΛ

The corresponding

–unit dimensions are

For gravity and the cosmological constant, define the dimensionless values

and

. Evaluated in the

(vacuum–matched)

–units,

so that

More generally, moving along the null direction by

(so

,

,

) gives

The vacuum–matching postulate (A14) fixes the remaining affine freedom by selecting the symmetric point

. In the resulting vacuum–matched

units the quarter–power base scales give

where

is a dimensionless invariant.Along the null rescaling direction one may shift weight between

G and

while keeping the product fixed:

Vacuum matching enforces

, so the chosen units are the symmetric quarter–power ones, with

One may re–scale along the null direction (choose

) to make

either (take

)

or (take

), but not both simultaneously, since the product is invariant:

This parameter is the gravitational analogue of the electromagnetic fine–structure constant : it is dimensionless and invariant under unit choices. Here encodes the simultaneous scaling of both G and alongside c and ℏ. In vacuum–matched –units one has and .

Closing summary. With four constants for three base dimensions, admitting

leaves a one–parameter nullspace freedom in the dimensional algebra. The kinematic anchors

and

fix

, and the vacuum–matching postulate

removes the remaining freedom, selecting the quarter-power length

in (A32) and thereby determining the full

unit set. In these units the dimensionless gravitational and cosmological constants share a single parameter,

so

is the concise condition for

G and

to join

c and

ℏ in the

system.

EM note. The electromagnetic fine-structure constant is dimensionless and invariant under unit choices; the uniqueness of the units arises from the mechanical anchors plus the vacuum-matching postulate (A32), independent of the EM sector.

Appendix B. Natural Units and the Lessons from History

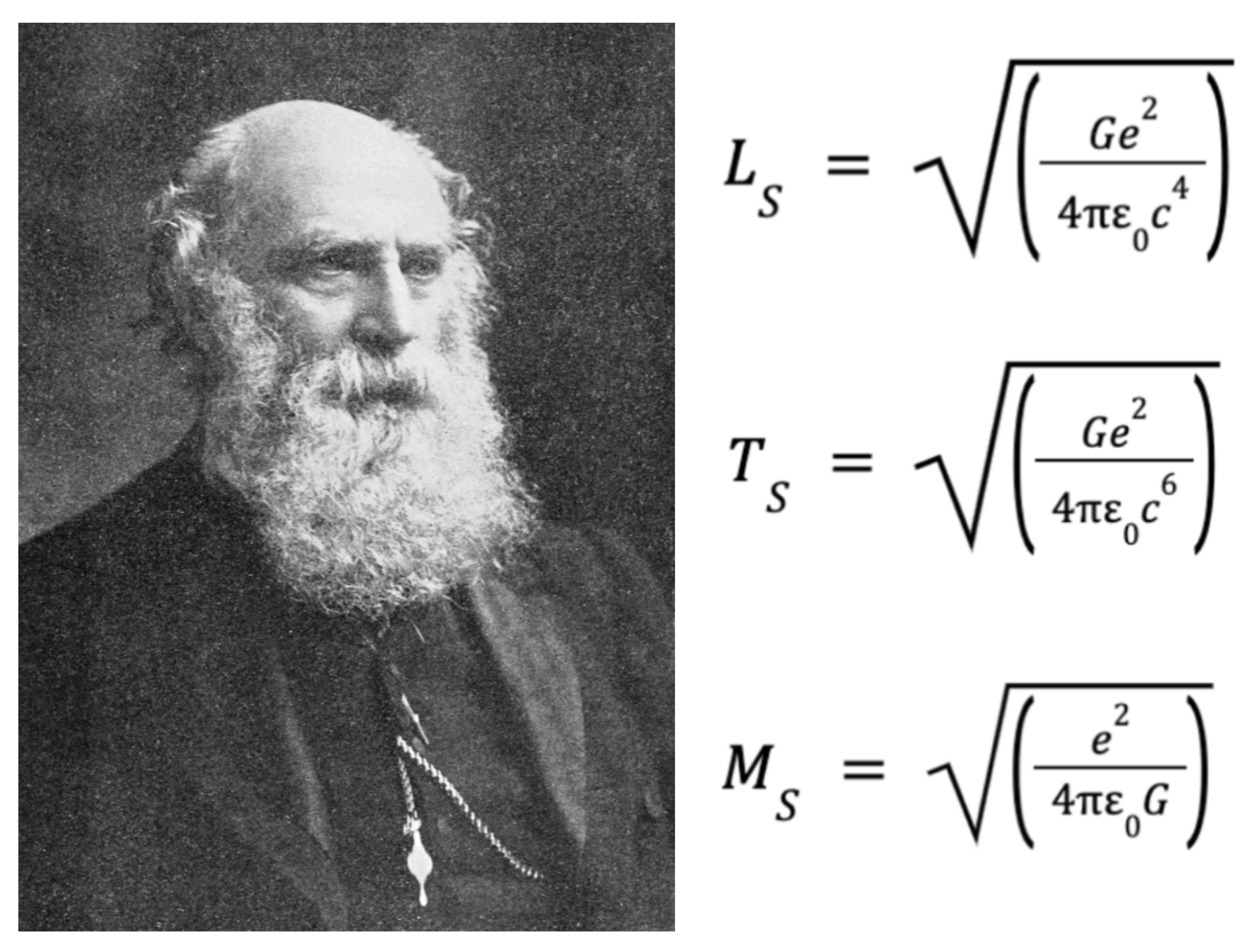

George Stoney [

71] introduced the first system of natural units, based on

and

, it was an early attempt to unify gravitation and electromagnetism. See

Figure B1.

Figure B1.

George Johnstone Stoney devised his system of natural units, prior to the discovery of Planck’s quantum of action. Although not penned by Stoney, the derived unit of angular momentum is just and given by equation (B1). Whilst the FSC entered physics in 1916 by Sommerfeld, it could have emerged much earlier with the discovery of ℏ. Image created by the author using public-domain source material.

Figure B1.

George Johnstone Stoney devised his system of natural units, prior to the discovery of Planck’s quantum of action. Although not penned by Stoney, the derived unit of angular momentum is just and given by equation (B1). Whilst the FSC entered physics in 1916 by Sommerfeld, it could have emerged much earlier with the discovery of ℏ. Image created by the author using public-domain source material.

In this first system of natural units, the fundamental natural Stoney unit of angular momentum

is given by,

Once Planck uncovered

ℏ, his quantum of action [

41], denoting a universal lower bound on angular momentum

where,

the Stoney system became subsumed into the Planck scale. See

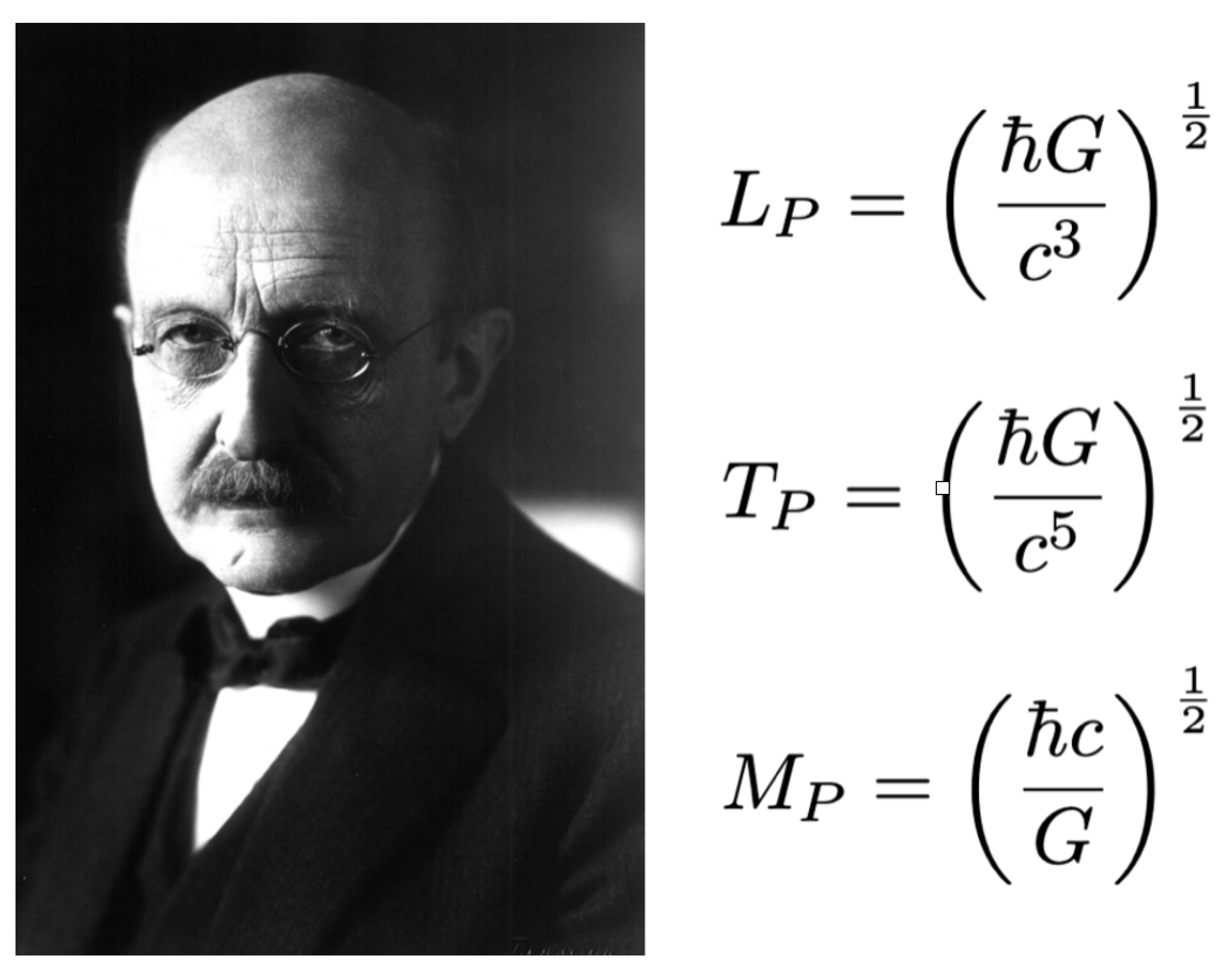

Figure B2.

Figure B2.

Max Planck’s discovery of his quantum of action,

ℏ subsumed the existing Stoney system of natural units, into the Planck scale. Yet, the scale is the theoretical source of the catastrophic energy density of the vacuum (See

Section 8); a universal expansion rate in which the universe should double in size every

[

4,

33,

38,

52]. The observation of an accelerated expansion[

1,

2] and the realisation that

, suggests such Planckian pathologies result from an incomplete quantum scale, without

, setting a fundamental entropic bound and limit in nature (See

Section 2.2). Just as the emergence of the FSC,

reflected the emergence of Planck’s new scale from the Stoney system, the dimensionless GFSC,

becomes its gravitational analogue, pointing to a more fundamental quantum scale in nature, the

-scale.

Image created by the author using public-domain source material.

Figure B2.

Max Planck’s discovery of his quantum of action,

ℏ subsumed the existing Stoney system of natural units, into the Planck scale. Yet, the scale is the theoretical source of the catastrophic energy density of the vacuum (See

Section 8); a universal expansion rate in which the universe should double in size every

[

4,

33,

38,

52]. The observation of an accelerated expansion[

1,

2] and the realisation that

, suggests such Planckian pathologies result from an incomplete quantum scale, without

, setting a fundamental entropic bound and limit in nature (See

Section 2.2). Just as the emergence of the FSC,

reflected the emergence of Planck’s new scale from the Stoney system, the dimensionless GFSC,

becomes its gravitational analogue, pointing to a more fundamental quantum scale in nature, the

-scale.

Image created by the author using public-domain source material.

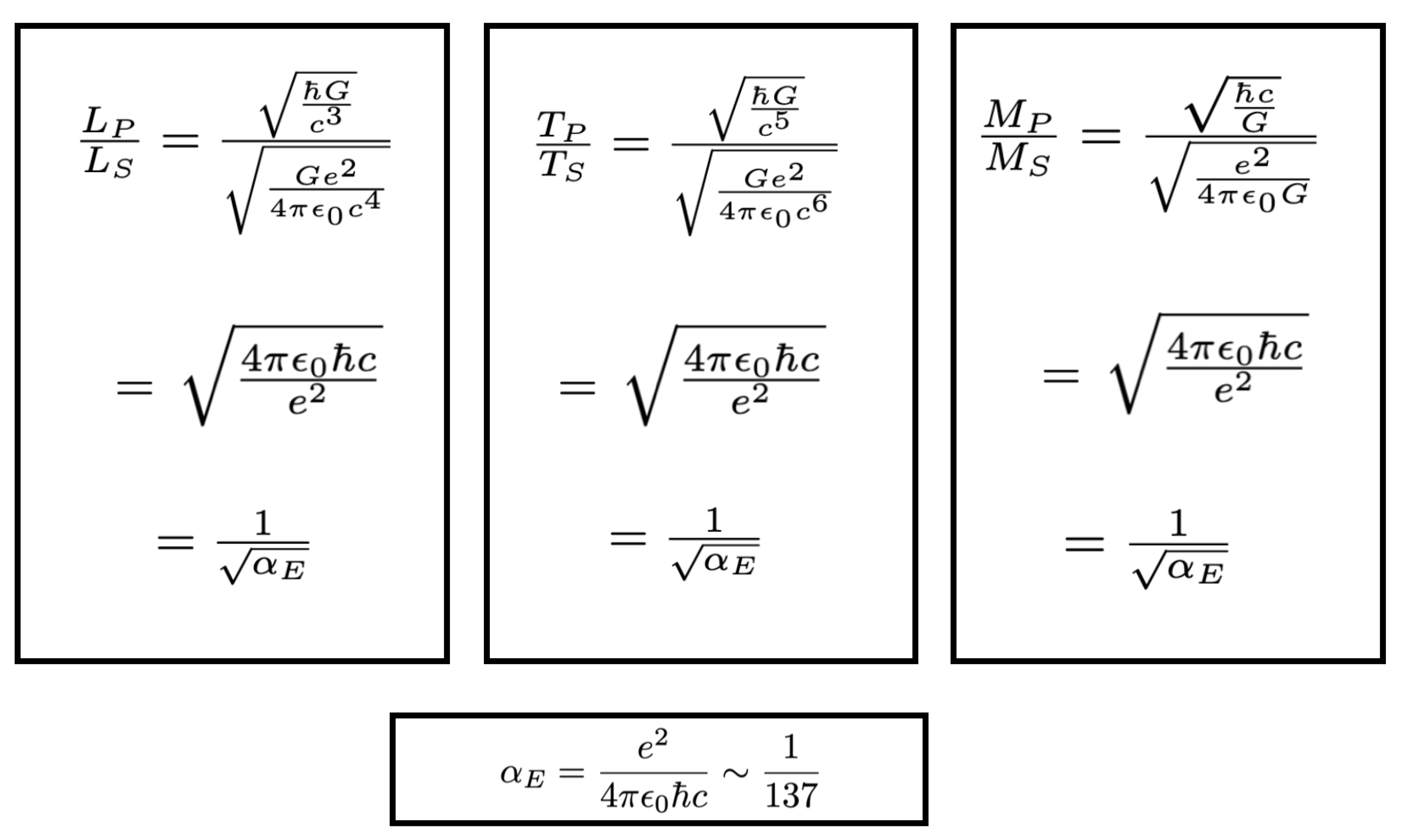

The ratio between the two angular momenta, both in units of

is simply the FSC given by,

Although the world of physics was introduced to the FSC in 1916 when Sommerfeld observed the fine splitting of hydrogen spectral lines [

74], it could have in theory been introduced much earlier by Planck himself once his quantum of action was discovered. The FSC is therefore a ratio of two like dimensioned quantities - angular momentum in Stoney units and that of

ℏ itself, not some ’magical’ relationship between several, seemingly unrelated constants [

75,

76]. We find the

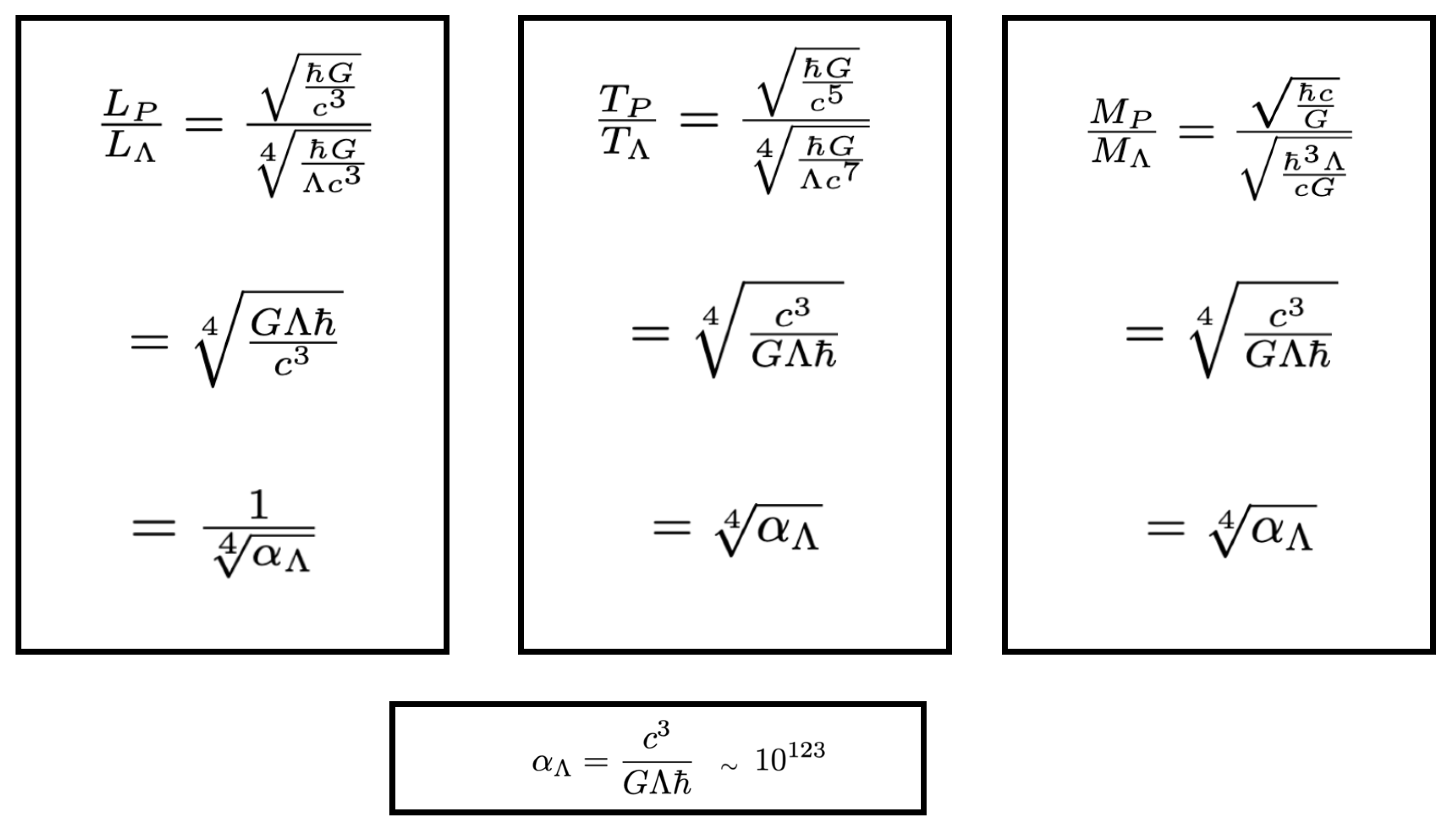

-scale, see

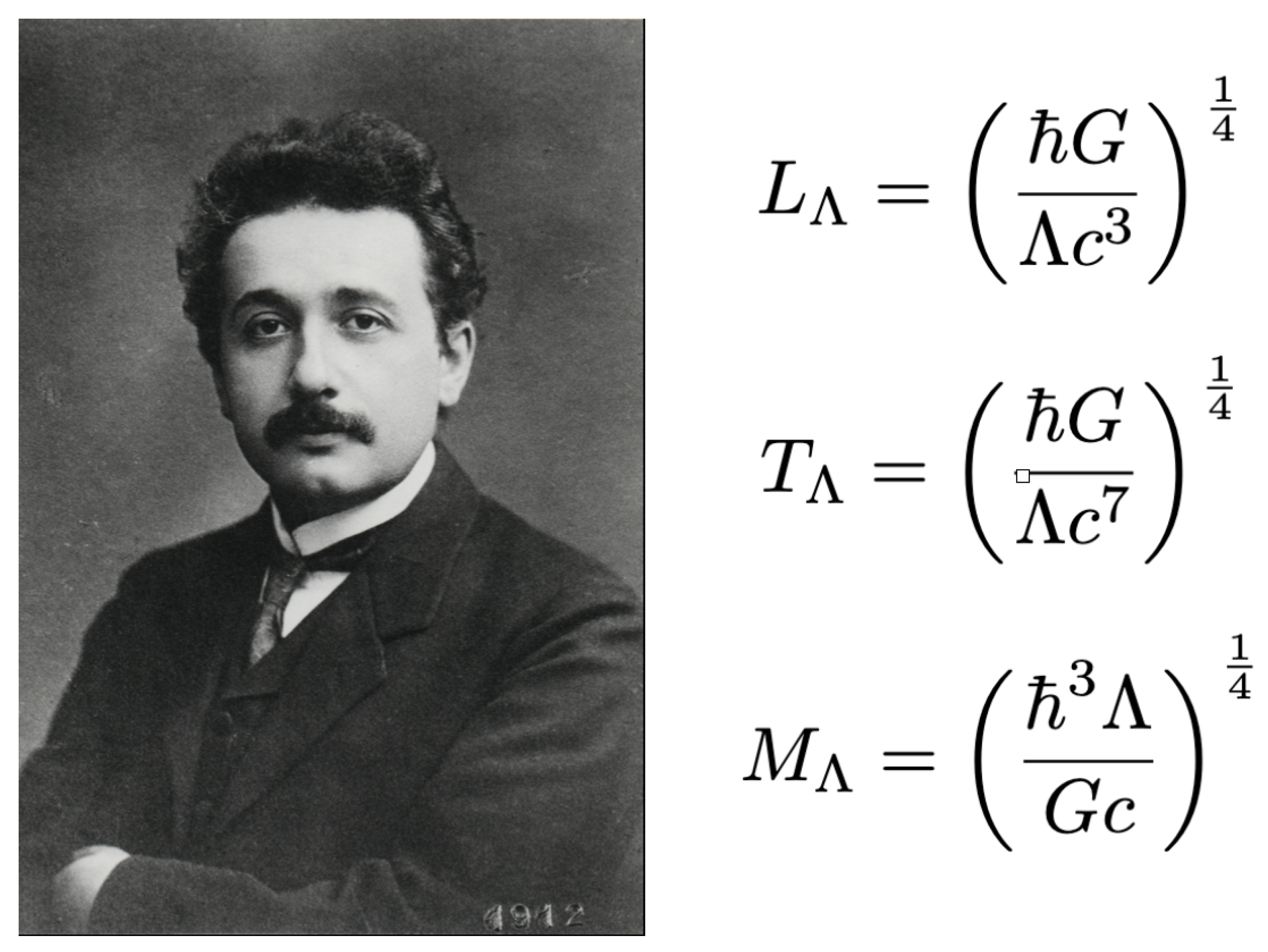

Figure B3, becomes its natural successor.

Figure B3.

The Lambda scale cannot emerge from dimensional analysis alone. An infinite number of possibilities represented by the affine family (A13) is the consequence. Whilst the Planck system maps three constants on to three base dimensions [M],[L],[T], uniqueness comes for free. However, the requirement of mapping four constants and on to the same three base dimensions, leaves an extra degree of freedom () in (A13). Physics fixes by the vacuum–matching postulate: the requirement that the resulting ZPE density, matches the vacuum energy from GR (See Eq. A14). The inclusion of Einstein’s cosmological constant becomes a thermodynamic completion of his gravitational vision, represented in Box 10.1. Rather than a historical blunder, it is simultaneously a necessity and a constraint, an inevitable consequence of its thermodynamic foundation. Image created by the author using public-domain source material.

Figure B3.

The Lambda scale cannot emerge from dimensional analysis alone. An infinite number of possibilities represented by the affine family (A13) is the consequence. Whilst the Planck system maps three constants on to three base dimensions [M],[L],[T], uniqueness comes for free. However, the requirement of mapping four constants and on to the same three base dimensions, leaves an extra degree of freedom () in (A13). Physics fixes by the vacuum–matching postulate: the requirement that the resulting ZPE density, matches the vacuum energy from GR (See Eq. A14). The inclusion of Einstein’s cosmological constant becomes a thermodynamic completion of his gravitational vision, represented in Box 10.1. Rather than a historical blunder, it is simultaneously a necessity and a constraint, an inevitable consequence of its thermodynamic foundation. Image created by the author using public-domain source material.

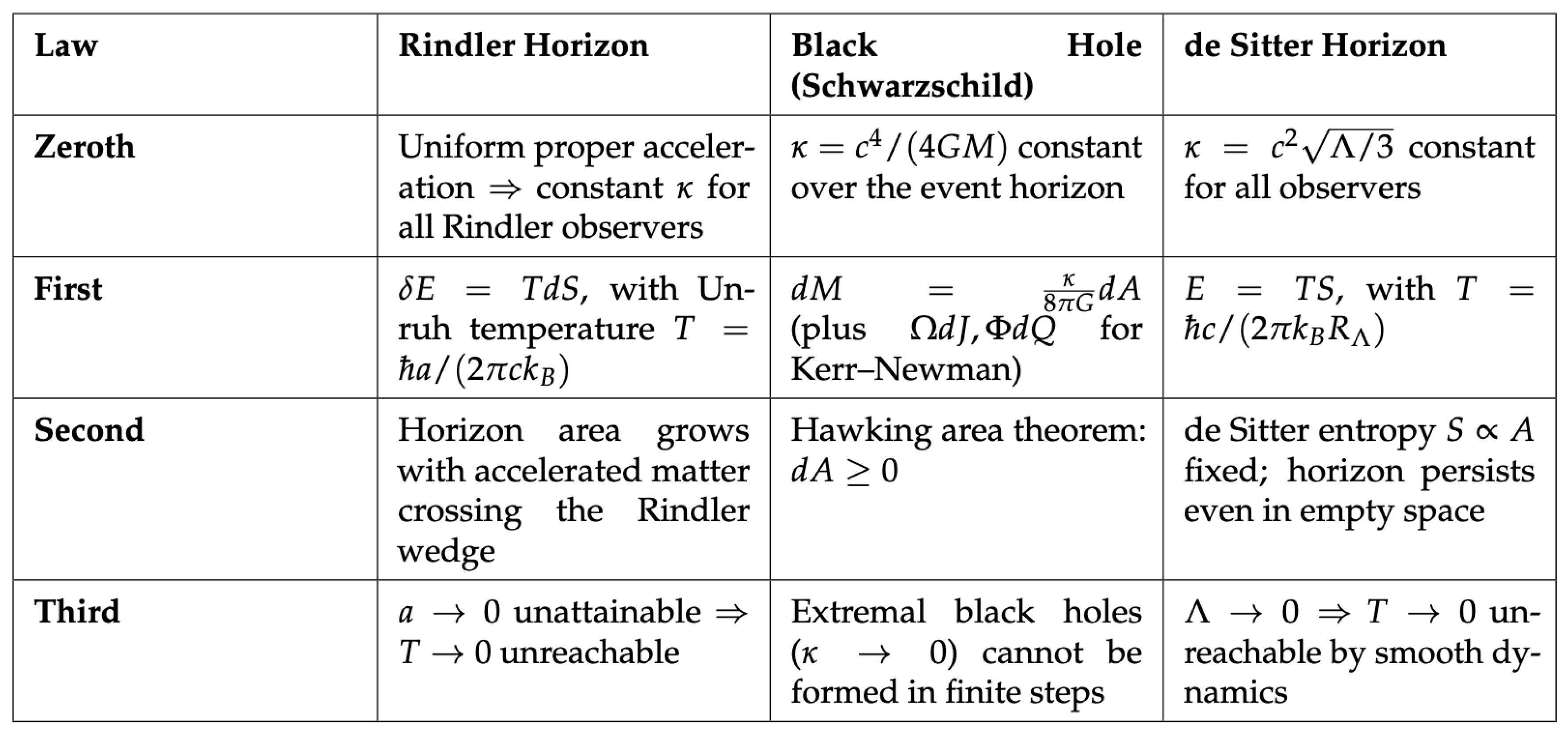

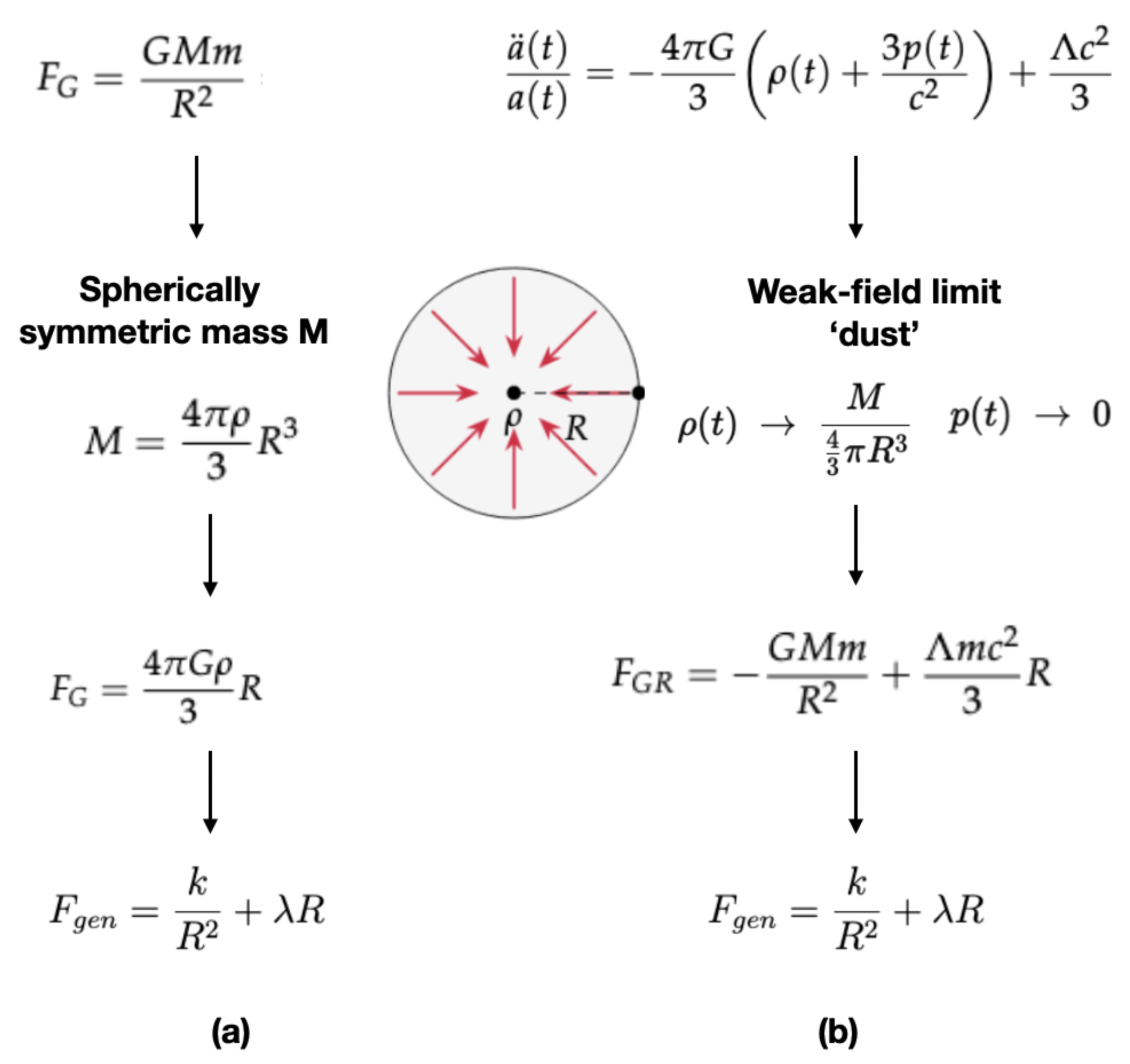

In GR,

has the dimensions of an inverse length squared or simply an inverse unit area in

, thus,

In the Planck system, a unit inverse area is the inverse of the Planck length squared:

Thus the ratio of the two is also a comparison of like dimensions, both inverse unit areas, yields the GFSC

,

In gravitational physics, the cosmological constant is simply interpreted as a vacuum energy density. However, thermodynamics suggests the energy of a system is tied to its entropy (E = TS), thus

is also a measure of entropy, that transforms the Bekenstein-Hawking bound into a fundamental upper limit of entropy for the

-universe.

Where

is just the cosmological constant in its dimensionless form. The consequences of Lambda’s introduction into physics finds a historical parallel with the shift from Stoney to Planck units, once

ℏ was discovered [

16]. If

is considered a fundamental constant of nature and is incorporated into physics, then a new ‘natural scale’ emerges - the

-scale. Like its Planck predecessor whose base and derived quantaties differ by factors of

respectively from their Stoney counterparts, see

Figure B4, the Lambda base and derived units differ from their Planck counterparts by

, see

Figure B5.

Just as encodes a limit on action, encodes a universal bound on gravitational entropy. The Lambda scale is thus not an arbitrary extension, but the natural successor to the Planck system — and the only one consistent with a finite vacuum entropy.

Figure B4.

The Planck scale differs from their Stoney counterparts by factors of the square root of the FSC, .

Figure B4.

The Planck scale differs from their Stoney counterparts by factors of the square root of the FSC, .

With

c,

ℏ, and now

, we arrive at a complete triad of fundamental constants — each defining a domain of limiting behavior: causality, action, and information capacity. A coherent system of natural units must reflect all three. The Lambda system grounded in thermodynamics and quantum field theory, achieves precisely this. See

Figure B5. It not only resolves the vacuum catastrophe, but redefines the conditions under which all physical laws — including gravity — must operate (LoEC).

Figure B5.

The Planck scale differs from the -scale in an analogous manner to the Planck to Stoney ratios, but this time by factors involving the quartic root of the GFSC, .

Figure B5.

The Planck scale differs from the -scale in an analogous manner to the Planck to Stoney ratios, but this time by factors involving the quartic root of the GFSC, .

Historically, Stoney’s units were subsumed once ℏ was recognized as fundamental: adopting the Planck charge rewrites electromagnetism in terms of the dimensionless coupling . Analogously, adding furnishes an IR ingredient: vacuum matching selects the length and packages gravity with the dimensionless . The –framework thus extends Planck’s by incorporating horizon thermodynamics.

In summary, once

is recognised as a fundamental constant fixing a finite upper bound on the universe’s entropy [

10,

11], the Lambda scale emerges naturally as the successor to the Planck system. Dimensional analysis identifies

as the geometric mean of the Planck length

and the de Sitter radius

[

7,

17]. This property, combined with the thermodynamic requirement that

be constant, makes

an inevitable new quantum length. Unlike the Planck scale, which overestimates the vacuum energy, the Lambda scale matches the observed value, aligning GR with thermodynamics and QFT, resolving the vacuum catastrophe [

4].