Submitted:

16 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

• Jasmonates (JAs)-mediated pathways are central signaling hubs in plant defense response. However, the identification of mobile and non-mobile signals involved in downstream systemic signaling is still less studied. • Here, we investigate the role of the jasmonic acid-isoleucine conjugating enzyme, JAR1, and the mobility of jasmonic acid-isoleucine (JA-Ile) in wound-induced local and systemic defense using LC-MS/MS for targeted jasmonate analysis and untargeted metabolomics in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. • The use of jarin-1, a specific inhibitor of JA-Ile biosynthesis, suggested that JA-Ile is synthesized de novo in the particular tissues, rather than being a mobile signal. In addition, inhibition of JAR1 enzyme activity affected an array of downstream metabolic pathways, locally and systemically, such as amino acids and carbohydrate metabolism. • This study demonstrates that the occurrence and spread of local and systemic downstream signals depend on JAR1 activity, and this enzyme exclusively regulates a series of metabolic pathways under both wounding and non-wounding conditions.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

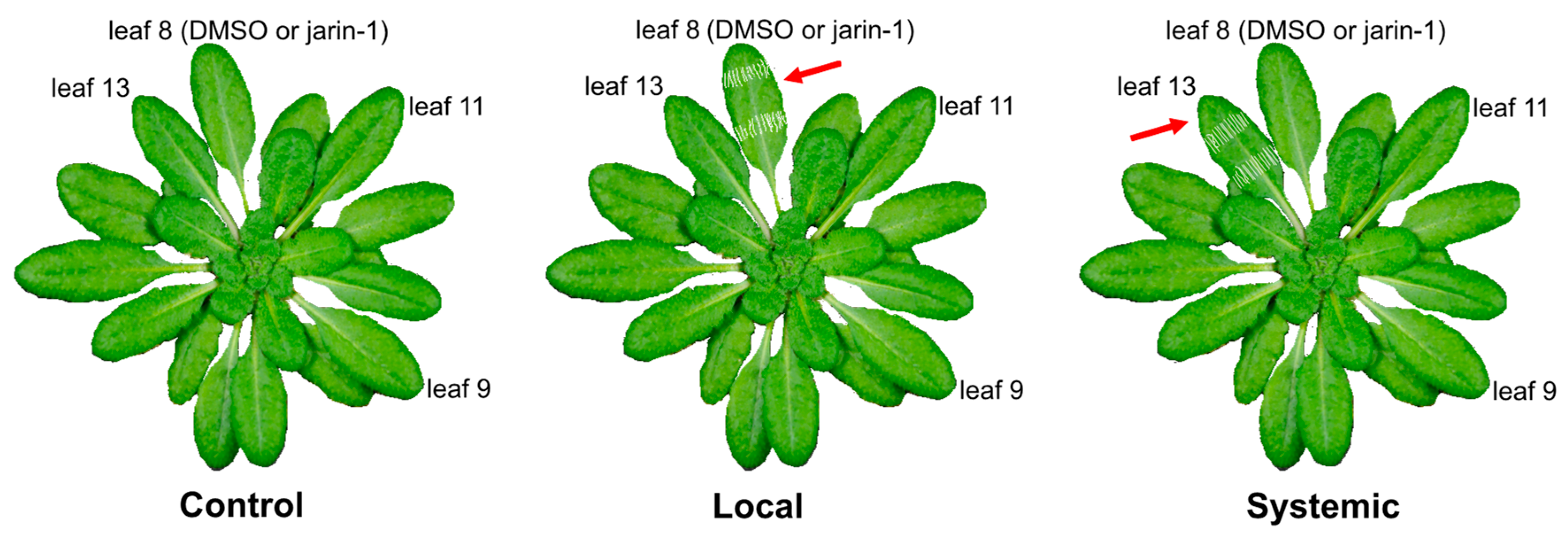

Application of Jarin-1 and Wounding

Phytohormone Measurements

Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

Metabolite Extraction

LC-MS Measurements

LC-MS analysis was performed following the methods described in Weinhold et al., (2022).

Data Processing

Compound Annotation

Data Analysis

Results

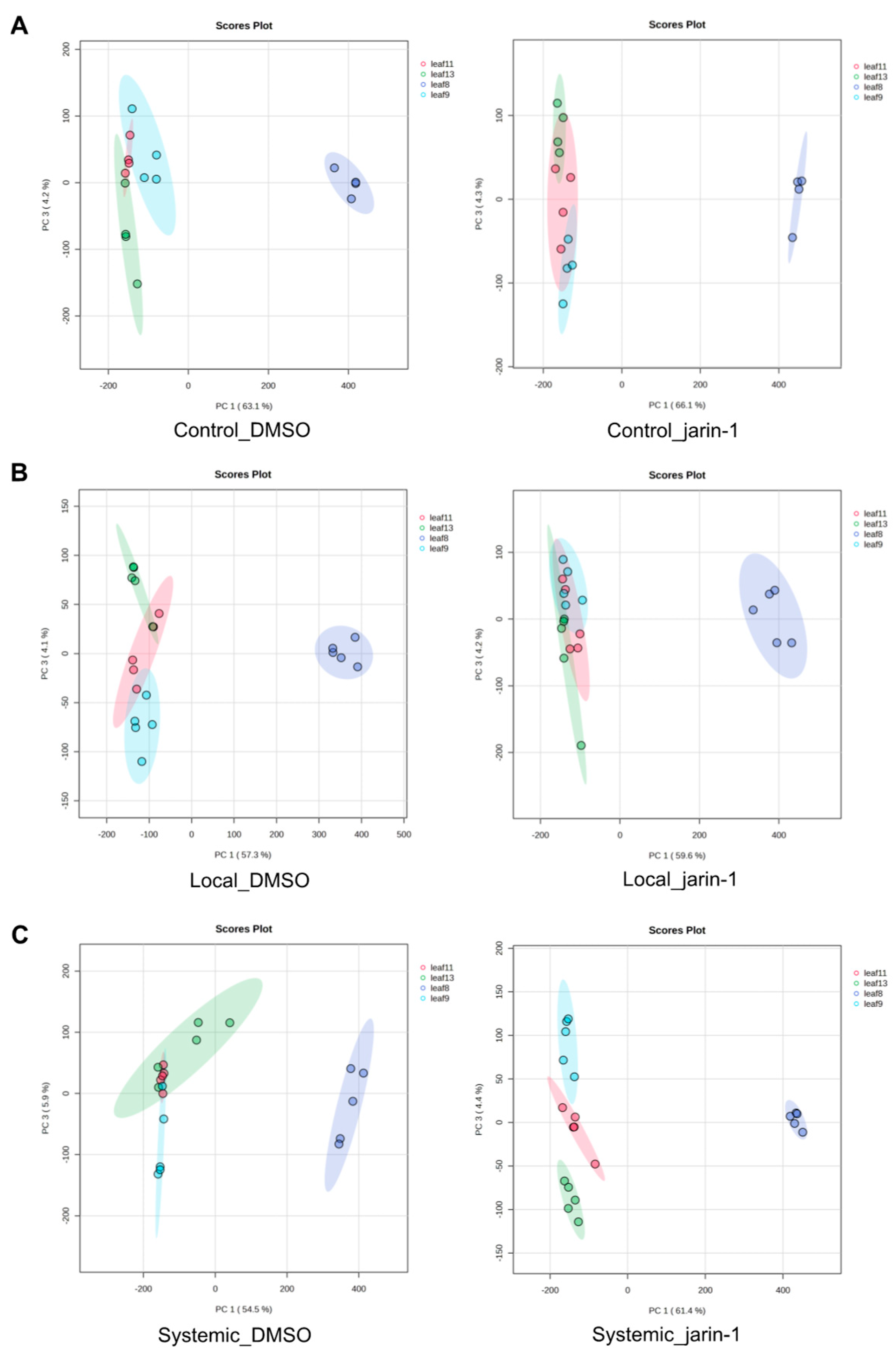

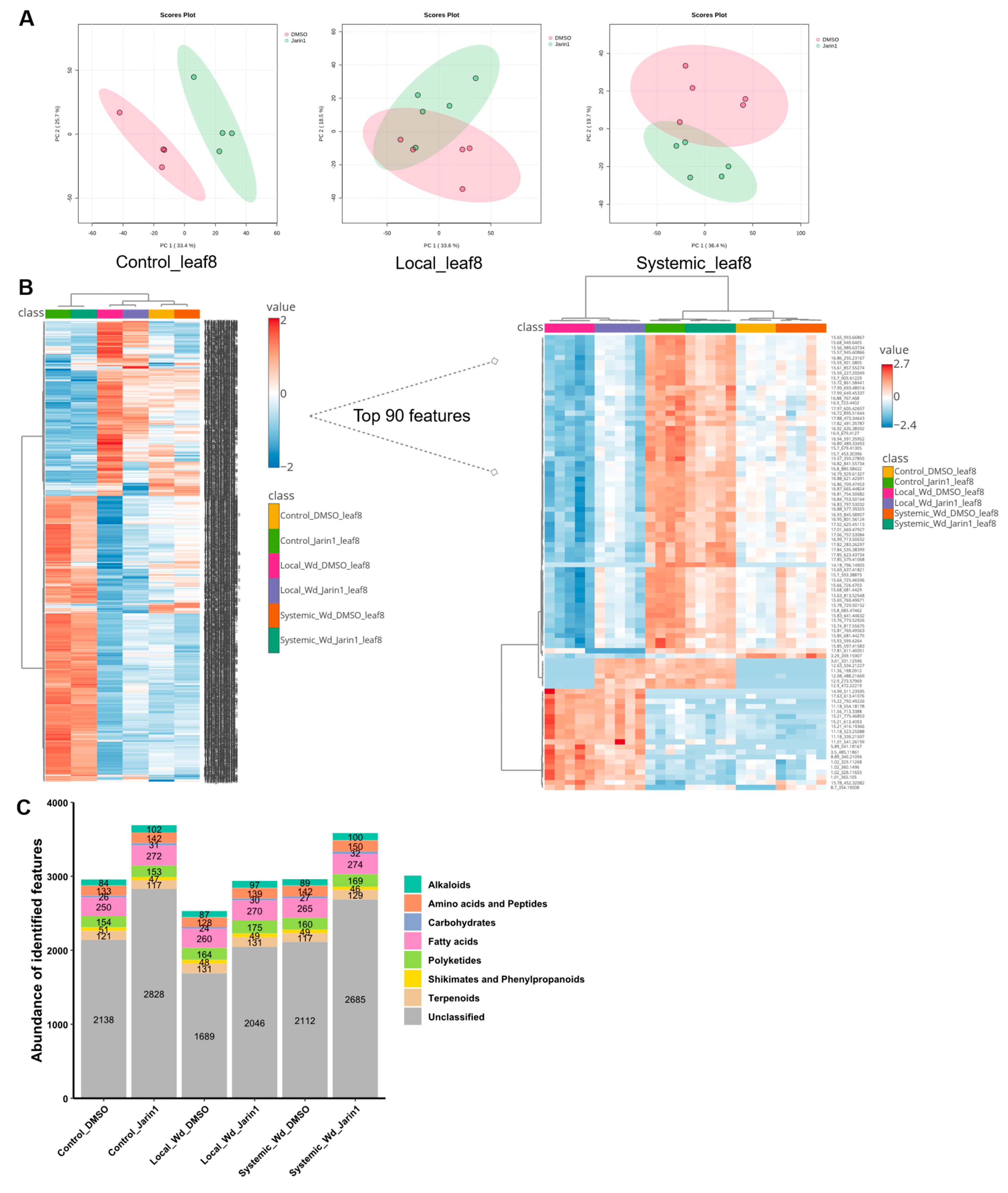

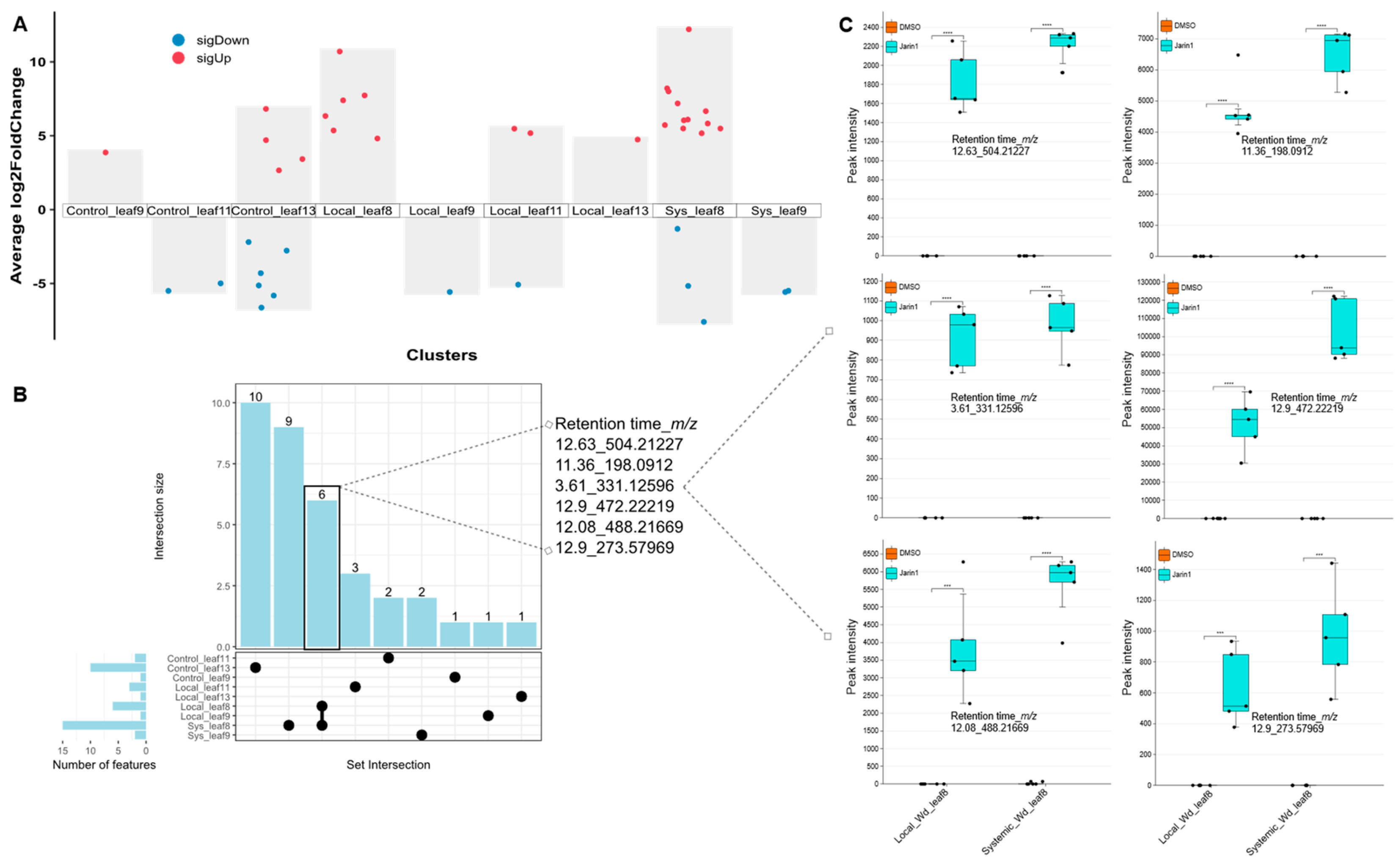

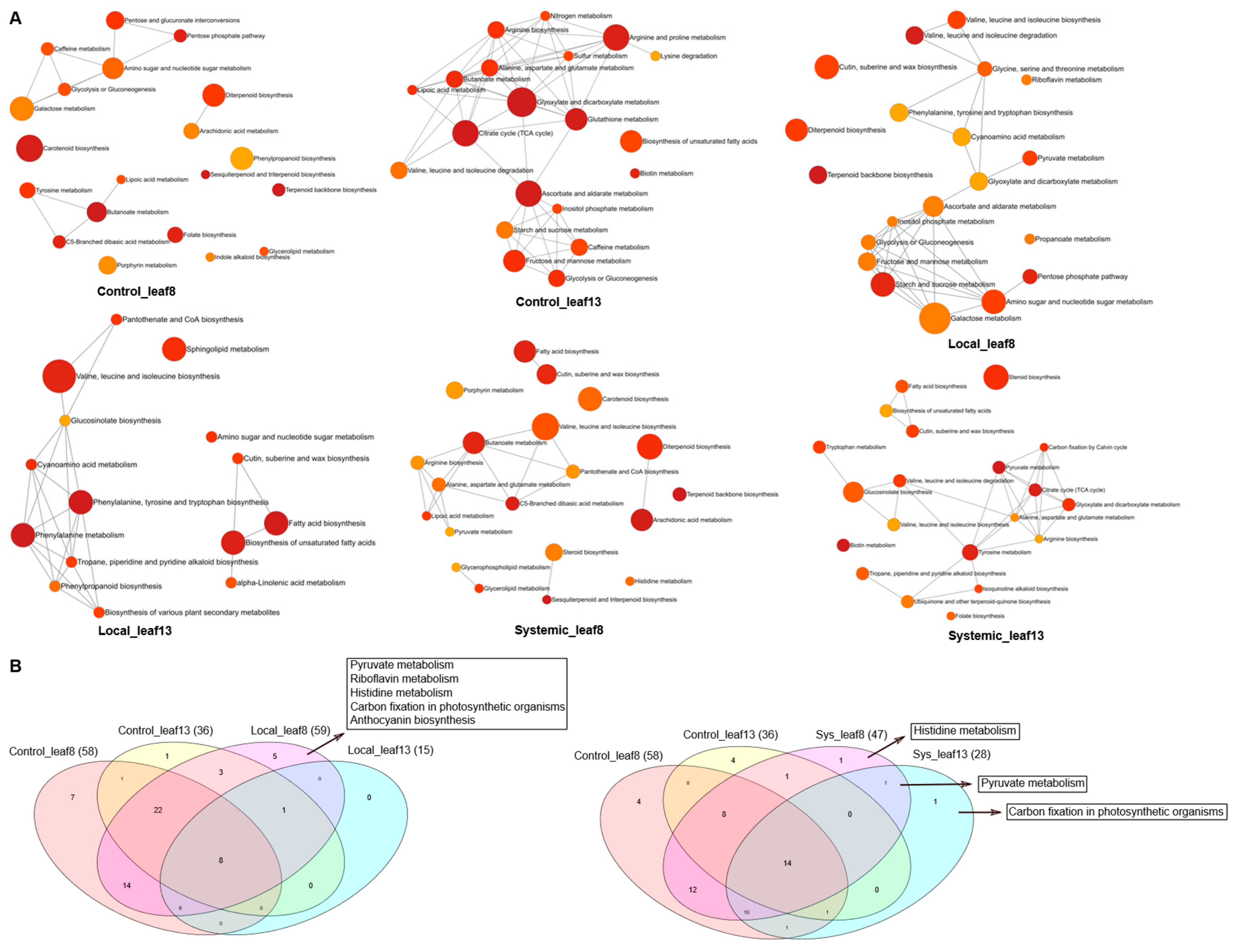

Inhibition of JAR1 Alters the Local and Systemic Leaf Metabolic Profiles

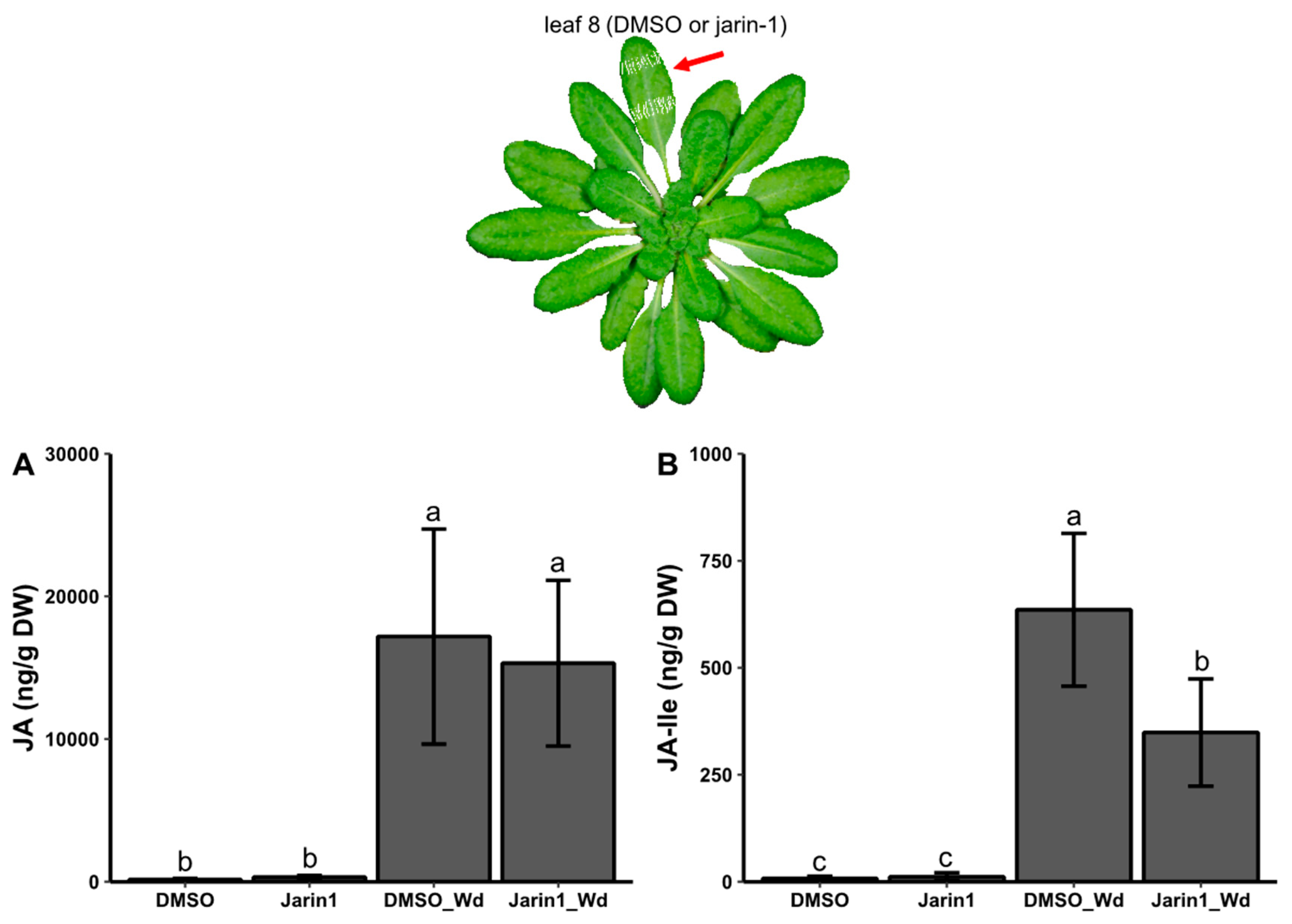

Jarin-1 Partly Inhibits Wound-Stimulated JA-Ile Biosynthesis in a Local Manner

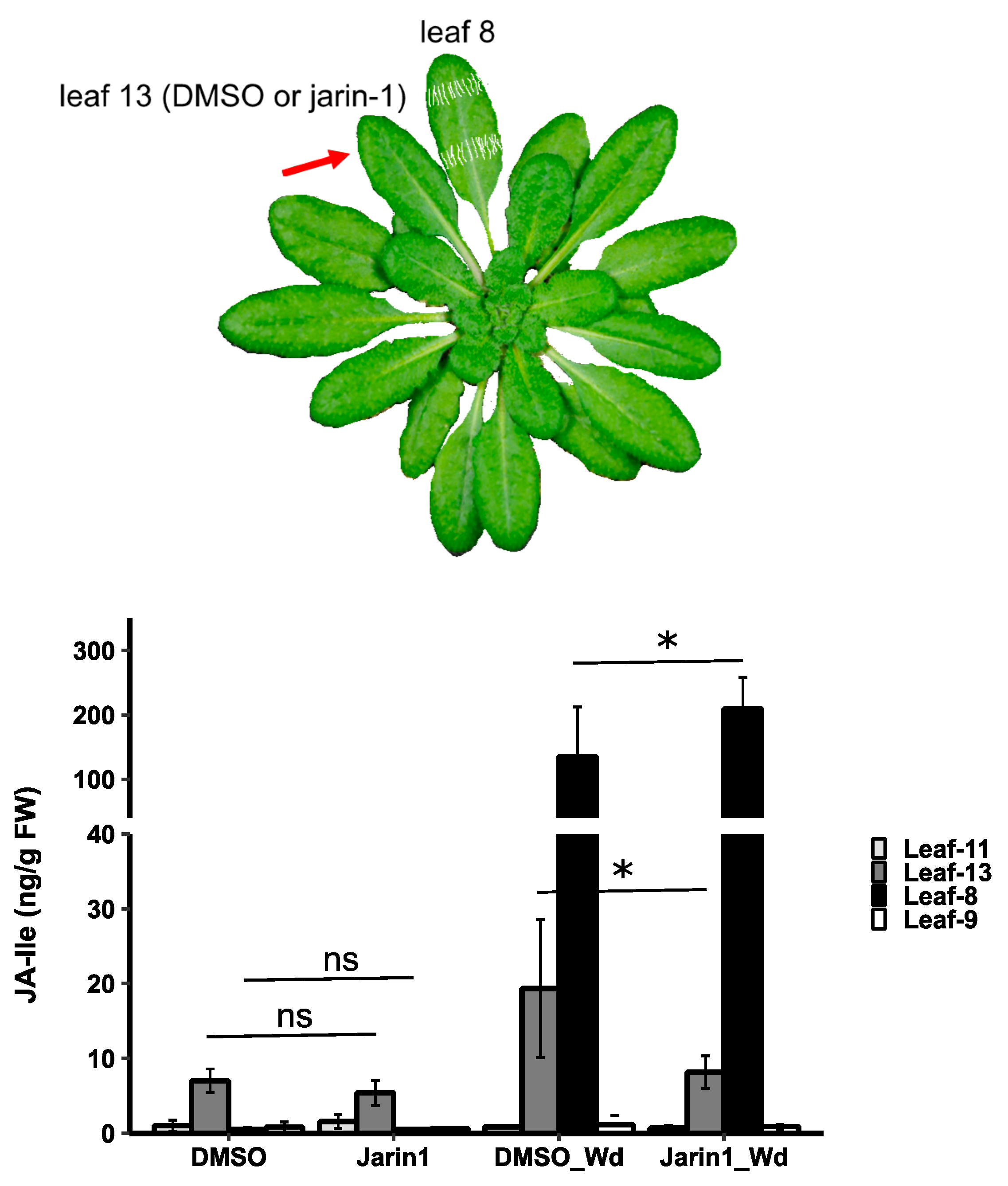

Jarin-1 Inhibits Wound-Stimulated JA-Ile Biosynthesis in a Systemic Manner

Discussion

Inhibition of JAR1 Alters the Leaf Metabolic Profile

JA-Ile is Probably Not a Mobile Signal in This Context

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

Author Contributions

Data availability statement

References

- Bozorov, T.A.; Dinh, S.T.; Baldwin, I.T. JA but not JA-Ile is the cell-nonautonomous signal activating JA mediated systemic defenses to herbivory in Nicotiana attenuata. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2017, 59, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, P.; Li, Z. Effects of MeJA on Arabidopsis metabolome under endogenous JA deficiency. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, M.C.; MacLean, B.; Burke, R. A Cross-platform Toolkit for Mass Spectrometry and ProteomicsZwane’s mining charter lunacy. Nature Biotechnology 2012, 30, 918–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehab, E.W.; Yao, C.; Henderson, Z.; Kim, S.; Braam, J. Arabidopsis Touch-Induced Morphogenesis Is Jasmonate Mediated and Protects against Pests. Current Biology 2012, 22, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Devireddy, A.R.; Azad, R.K.; Shulaev, V.; Mittler, R. Local and systemic metabolic responses during light-induced rapid systemic signaling. Plant Physiology 2018, 178, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concha, C.M.; Figueroa, N.E.; Poblete, L.A.; Oñate, F.A.; Schwab, W.; Figueroa, C.R. Methyl jasmonate treatment induces changes in fruit ripening by modifying the expression of several ripening genes in Fragaria chiloensis fruit. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2013, 70, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.Y.; Huo, X.W.; Li, J.W.; An, J.B.; Mi, F.G.; Shi, F.L.; Zhang, Z.Q. Overexpression MsJAR1 gene increased lateral branches and plant height in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 16956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dávila-Lara, A.; Rahman-Soad, A.; Reichelt, M.; Mithöfer, A. Carnivorous Nepenthes x ventrata plants use a naphthoquinone as phytoanticipin against herbivory. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfin, J.C.; Kanno, Y.; Seo, M.; Kitaoka, N.; Matsuura, H.; Tohge, T.; Shimizu, T. AtGH3.10 is another jasmonic acid-amido synthetase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Journal 2022, 110, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.D.; Zúñiga, P.E.; Figueroa, N.E.; Pastene, E.; Escobar-Sepúlveda, H.F.; Figueroa, P.M.; Garrido-Bigotes, A.; Figueroa, C.R. Application of a JA-Ile biosynthesis inhibitor to methyl jasmonate-treated strawberry fruit induces upregulation of specific MBW complex-related genes and accumulation of proanthocyanidins. Molecules 2018, 23, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengler, N.G. The shoot apical meristem and development of vascular architecture. Canadian Journal of Botany 2006, 84, 1660–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Fleischauer, M.; Ludwig, M.; Aksenov, A.A.; Melnik, A.V.; Meusel, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. SIRIUS 4: A rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nature Methods 2019, 16, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dührkop, K.; Nothias, L.; Fleischauer, M.; Reher, R.; Ludwig, M.; Hoffmann, M.A.; Petras, D.; Gerwick, W.H.; Rousu, J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; et al. Systematic classification of unknown metabolites using high-resolution fragmentation mass spectra. Nature Biotechnology 2021, 39, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dührkop, K.; Shen, H.; Meusel, M.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. Searching molecular structure databases with tandem mass spectra using CSI : FingerID. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 12580–12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, E.; Farmer, E.; Mousavi, S.; Lenglet, A. Leaf numbering for experiments on long distance signalling in Arabidopsis. Protocol Exchange 2013, 071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fataftah, N.; Mohr, C.; Hajirezaei, M.R.; Wirén Nvon Humbeck, K. Changes in nitrogen availability lead to a reprogramming of pyruvate metabolism. BMC Plant Biology 2018, 18, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feunang, Y.D.; Eisner, R.; Knox, C.; Chepelev, L.; Hastings, J.; Owen, G.; Fahy, E.; Steinbeck, C.; Subramanian, S.; Bolton, E.; et al. ClassyFire : Automated chemical classification with a comprehensive, computable taxonomy. Journal of Cheminformatics 2016, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; Chini, A.; Hamberg, M.; Adie, B.; Porzel, A.; Kramell, R.; Miersch, O.; Wasternack, C.; Solano, R. (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine is the endogenous bioactive jasmonate. Nature Chemical Biology 2009, 5, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasperini, D.; Chételat, A.; Acosta, I.F.; Goossens, J.; Pauwels, L.; Goossens, A.; Dreos, R.; Alfonso, E.; Farmer, E.E. Multilayered Organization of Jasmonate Signalling in the Regulation of Root Growth. PLoS Genetics 2015, 11, e1005300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilleary, R.; Gilroy, S. Systemic signaling in response to wounding and pathogens. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2018, 43, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.A.; Nothias, L.; Ludwig, M.; Fleischauer, M.; Emily, C.; Witting, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Dührkop, K.; Böcker, S. Assigning confidence to structural annotations from mass spectra with COSMIC. bioRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, L.; Xu, F. JASMONATE RESISTANT 1 negatively regulates root growth under boron deficiency in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2021, 72, 3108–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Fukaki, H.; Prusinska, J.; Meester, C.; Quareshy, M.; Egoshi, S.; Matsuura, H.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Jasmonic acid inhibits auxin-induced lateral rooting independently of the CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 receptor. Plant Physiology 2018, 177, 1704–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jez, J.M. Connecting primary and specialized metabolism: Amino acid conjugation of phytohormones by GRETCHEN HAGEN 3 (GH3) acyl acid amido synthetases. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2022, 66, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiep, V.; Vadassery, J.; Lattke, J.; Maaß, J.P.; Boland, W.; Peiter, E.; Mithöfer, A. Systemic cytosolic Ca2+ elevation is activated upon wounding and herbivory in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist 2015, 207, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Wang, M.; Leber, C.A.; Nothias, L.; Reher, R.; Kang KBin Hooft JJJVan Der Dorrestein, P.C.; Gerwick, W.H.; Cottrell, G.W. NPClassi fi er : A Deep Neural Network-Based Structural Classi fi cation Tool for Natural Products. Journal of natural products 2021, 84, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, A.J.K.; Gao, X.; Daniel Jones, A.; Howe, G.A. A rapid wound signal activates the systemic synthesis of bioactive jasmonates in Arabidopsis. Plant Journal 2009, 59, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, R.; Schaarschmidt, S.; Hause, B. Repeated leaf wounding alters the colonization of Medicago truncatula roots by beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms. Plant Cell and Environment 2012, 35, 1344–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, F.; Li, S.; Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Yuan, L.; Liu, P. Importers Drive Leaf-to-Leaf Jasmonic Acid Transmission in Wound-Induced Systemic Immunity. Molecular Plant 2020, 13, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, R.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, X.; Dong, X.; Qi, M.; Jiang, C.Z.; Xu, T.; et al. The HD-Zip transcription factor SlHB15A regulates abscission by modulating jasmonoyl-isoleucine biosynthesis. Plant Physiology 2022, 189, 2396–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, M.; Nothias, L.; Dührkop, K.; Koester, I.; Fleischauer, M.; Hoffmann, M.A.; Petras, D.; Vargas, F.; Morsy, M.; Böcker, S.; et al. Database-independent molecular formula annotation using Gibbs sampling through ZODIAC. Nature Machine Intelligence 2020, 2, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, H.; Takeishi, S.; Kiatoka, N.; Sato, C.; Sueda, K.; Masuta, C.; Nabeta, K. Transportation of de novo synthesized jasmonoyl isoleucine in tomato. Phytochemistry 2012, 83, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meesters, C.; Mönig, T.; Oeljeklaus, J.; Krahn, D.; Westfall, C.S.; Hause, B.; Jez, J.M.; Kaiser, M.; Kombrink, E. A chemical inhibitor of jasmonate signaling targets JAR1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Chemical Biology 2014, 10, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithöfer, A.; Wanner, G.; Boland, W. Effects of feeding Spodoptera littoralis on lima bean leaves. II. Continuous mechanical wounding resembling insect feeding is sufficient to elicit herbivory-related volatile emission. Plant Physiology 2005, 137, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.A.R.; Chauvin, A.; Pascaud, F.; Kellenberger, S.; Farmer, E.E. GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE genes mediate leaf-to-leaf wound signalling. Nature 2013, 500, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, A.; Xu, Y.; Abou El-Ela, A.S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Mao, Z.; Chen, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; et al. Tissue-specific regulation of volatile emissions moves predators from flowers to attacked leaves. Current Biology 2023, 33, 2321–2329.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.M.; Chamel, A. Comparative Phloem Mobility of Nickel in Nonsenescent Plants. Plant Physiology 1986, 81, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Kurenda, A.; Stolz, S.; Chételat, A.; Farmer, E.E. Identification of cell populations necessary for leaf-to- leaf electrical signaling in a wounded plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 10178–10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.; Klein, M.; Hossbach, B.; Feussner, K.; Hornung, E.; Herrfurth, C.; Hamberg, M.; Feussner, I. Arabidopsis GH3.10 conjugates jasmonates. Plant Biology 2025, 27, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Chen, D.; Hu, T.; Zhang, S.; Qu, G. A Review: The Role of Jasmonic Acid in Tomato Flower and Fruit Development. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 2025, 43, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, K.; Enoki, A.; Yokota, Y.; Kurihara, T.; Shimizu, T.; Saburi, W.; Tohge, T.; Mori, H.; Van den Ackerveken, G.; Kitaoka, N.; et al. AtGH3.10 and JAR1 Produce 12-Hydroxyjasmonoyl-l-isoleucine from 12-Hydroxyjasmonic Acid in Arabidopsis thaliana. ChemBioChem 2025, 26, e202500151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; Macdonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, W398–W406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posit Software, P.B.C. 2024. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Boston, MA, USA: Posit Software, PBC. https://posit.co/.

- R Core Team. 2024. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Santino, A.; Taurino, M.; De Domenico, S.; Bonsegna, S.; Poltronieri, P.; Pastor, V.; Flors, V. Jasmonate signaling in plant development and defense response to multiple (a)biotic stresses. Plant Cell Reports 2013, 32, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, C.; Aikawa, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Nabeta, K.; Masuta, C.; Matsuura, H. Distal Transport of Exogenously Applied Jasmonoyl—Isoleucine with Wounding Stress. Plant & cell physiology 2011, 52, 509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, S.S.; Malabarba, J.; Reichelt, M.; Heyer, M.; Ludewig, F.; Mithöfer, A. Evidence for GABA-induced systemic GABA accumulation in arabidopsis upon wounding. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Zimmer, M.; Mielke, S.; Stellmach, H.; Melnyk, C.W.; Hause, B.; Gasperini, D. Wound-Induced Shoot-to-Root Relocation of JA-Ile Precursors Coordinates Arabidopsis Growth. Molecular Plant 2019, 12, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, M.C.; Meldau, S.; Gaquerel, E.; Diezel, C.; McGale, E.; Greenfield, S.; Baldwin, I.T. The active jasmonate JA-Ile regulates a specific subset of plant jasmonate-mediated resistance to herbivores in nature. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Xie, D. Molecular mechanism for jasmonate-induction of anthocyanin accumulation in arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2009, 60, 3849–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Choi, M.G.; Lee, H.K.; Cho, M.; Choi, S.B.; Choi, G.; Park, Y.I. Calcium dependent sucrose uptake links sugar signaling to anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2013, 430, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staswick, P.E.; Tiryaki, I. The oxylipin signal jasmonic acid is activated by an enzyme that conjugate it to isoleucine in Arabidopsis W inside box sign. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staswick, P.E.; Tiryaki, I.; Rowe, M.L. Jasmonate response locus JAR1 and several related Arabidopsis genes encode enzymes of the firefly luciferase superfamily that show activity on jasmonic, salicylic, and indole-3-acetic acids in an assay for adenylation. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suza, W.P.; Staswick, P.E. The role of JAR1 in Jasmonoyl-l-isoleucine production during Arabidopsis wound response. Planta 2008, 227, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svyatyna, K.; Jikumaru, Y.; Brendel, R.; Reichelt, M.; Mithöfer, A.; Takano, M.; Kamiya, Y.; Nick, P.; Riemann, M. Light induces jasmonate-isoleucine conjugation via OsJAR1-dependent and -independent pathways in rice. Plant, Cell and Environment 2014, 37, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tautenhahn, R.; Patti, G.; Rinehart, D.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomic Data. Analytical Chemistry 2012, 84, 5035–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota, M.; Spencer, D.; Sawai-toyota, S.; Jiaqi, W.; Zhang, T.; Koo, A.J.; Howe, G.A.; Gilroy, S. Glutamate triggers long-distance, calcium-based plant defense signaling. Science 2018, 361, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadassery, J.; Reichelt, M.; Hause, B.; Gershenzon, J.; Boland, W.; Mithöfer, A. CML42-Mediated Calcium Signaling Coordinates Responses to Spodoptera Herbivory and Abiotic Stresses. Plant Physiology 2012, 159, 1159–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadassery, J.; Reichelt, M.; Jimenez-Aleman, G.H.; Boland, W.; Mithöfer, A. Neomycin Inhibition of (+)-7-Iso-Jasmonoyl-L-Isoleucine Accumulation and Signaling. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2014, 40, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hu, C.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J.; Pan, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Shi, K.; Xia, X.; et al. Systemic Root-Shoot Signaling Drives Jasmonate-Based Root Defense against Nematodes. Current Biology 2019, 29, 3430–3438.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, J.M.; Cazzonelli, C.I.; Hartley, S.E.; Johnson, S.N. Simulated Herbivory: The Key to Disentangling Plant Defence Responses. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 34, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, A.; Döll, S.; Liu, M.; Schedl, A.; Pöschl, Y.; Xu, X.; Neumann, S.; Dam, N.M.V. Tree species richness differentially affects the chemical composition of leaves, roots and root exudates in four subtropical tree species. Journal of Ecology 2022, 110, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tao, Z.; Jin, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Gong, A.G.W.; Yuan, Y.; Dong, T.T.X.; Tsim, K.W.K. Jasmonate-Elicited Stress Induces Metabolic Change in the Leaves of Leucaena leucocephala. Molecules 2018, 23, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, M.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, G. Transcriptome analysis of calcium-induced accumulation of anthocyanins in grape skin. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 260, 108871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Sengupta, S.; Burks, D.; Azad, R.K.; Mittler, R. Identification and characterization of a core set of ROS wave-associated transcripts involved in the systemic acquired acclimation response of Arabidopsis to excess light. Plant Journal 2019, 98, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Krajinski, F.; van Dam, N.M.; Hause, B. Jarin-1, an inhibitor of JA-Ile biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana, acts differently in other plant species. Plant Signaling and Behavior 2023, 18, e2273515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).