1. Introduction

Ustilago maydis (

U. maydis) is a significant disease that seriously endangers maize production. It is prevalent in major maize-producing areas and significantly affects maize yield and quality [

1]. This pathogen has unique infection characteristics, infecting throughout the entire growth period of maize, with a preference for young tissues. The most typical symptom is the formation of characteristic tumor-like protrusions on the ear [

2]. The development of the tumor shows a distinct dynamic change process: initially, it presents as a white fleshy structure. As it develops, it gradually turns black and eventually forms a black powdery winter spore mass. After maturation, it releases spores for secondary transmission [

3]. It is worth noting that this pathogen has a wide range of infection and can infect multiple organs of maize such as roots, stems and leaves. Among them, the period from the emergence stage to the three-leaf stage is the most susceptible and dangerous period [

4]. Its teliospores have special biological characteristics, without a dormant period and can directly germinate under suitable temperature and humidity conditions, invading maize tissues through wounds to complete the infection cycle [

5]. Currently, the prevention and control of this disease mainly adopt comprehensive prevention and control strategies, including agricultural measures such as the selection and breeding of disease-resistant varieties, the removal of diseased and dead plants, reasonable crop rotation and the optimization of field cultivation management [

6,

7,

8]. Although chemical control has been widely adopted in production due to its simple operation and quick effect, the problem of pesticide residues caused by the long-term use of chemical pesticides, as well as the potential risks to the ecological environment and the safety of agricultural products, have become increasingly prominent [

9]. This situation has prompted researchers to actively seek more environmentally friendly, efficient and sustainable new disease prevention and control methods. Under this background, in-depth research on the self-defense mechanism of plants and the development of green prevention and control technologies based on plant immune induction and resistance have important theoretical and practical significance.

The formation of plant disease resistance is a complex and long-term evolutionary process, with different plant species exhibiting diverse resistance mechanisms in response to pathogen infection. Induced resistance refers to the systemic defense response activated in plants after being infected by pathogens or stimulated by specific inducers. This phenomenon was first discovered in research on plant-virus interactions [

10]. Studies have shown that certain beneficial microorganisms, such as

Pseudomonas spp., can induce broad-spectrum resistance in plants and significantly enhancing the host's defense against various pathogens [

11,

12]. The molecular mechanisms of plant induced resistance mainly include the following four aspects: (1) Reinforcement of cell wall structure, such as callose deposition and lignification enhancement; (2) The outbreak of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activation of the antioxidant system significantly increased the activities of related defense enzymes (such as POD, PPO, PAL, chitinase, etc.). (3) Induced synthesis of phytoalexins, such as the accumulation of secondary metabolites like capsaicin and maize terpenoids; (4) The outbreak of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activation of the antioxidant system significantly increased the activities of related defense enzymes (such as POD, PPO, PAL, chitinase, etc.). According to the nature of the inducers, plant induced resistance can be divided into two major categories: abiotic induction (such as chemical substances, physical stimuli) and biotic induction (such as microorganisms, pathogen-related molecular patterns). Currently, various efficient and safe disease resistance inducers have been applied in agricultural production [

13].

In recent years, the use of exogenous plant hormones to induce disease resistance has become a research hotspot in maize disease prevention and control. Plant hormones, as key signaling molecules, can regulate plant physiological responses at extremely low concentrations and trigger endogenous synthesis through environmental stimuli [

14]. When pathogens infect, the plant hormone network precisely regulates defense signal transduction through antagonistic, synergistic, or temporal regulation, activating the expression of disease resistance-related genes [

15], thereby coordinating the adaptability of plant to biological stress [

16]. Among them, jasmonic acid (JA) plays a central role as an important endogenous signaling molecule in plant disease resistance, especially in the defense against necrotrophic pathogens [

17,

18]. JA and its methyl ester derivatives (such as methyl jasmonate, MeJA) can induce the synthesis of various defense-related secondary metabolites, including nicotine, alfalfa alkaloids and other alkaloids [

19,

20]. Research by Zou Zhiyan [

21] shows that exogenous JA treatment can significantly enhance rice resistance to rice blast disease, and the mechanism involves the systematic enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities (such as SOD, CAT, POD). At the molecular level, the JA signaling pathway can be divided into three key stages: (1) JA signal perception mediated by the receptor COI1 (CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1); (2) Signal transduction and inhibitor degradation involving JAZ (JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN) proteins; (3) Activation of downstream transcriptional regulatory networks, ultimately achieving various physiological functions mediated by JA, including disease resistance defense, growth and development, and environmental adaptation, etc. [

22]. The clarification of this signaling pathway provides an important theoretical basis for using JA to induce plant disease resistance.

However, the molecular mechanism by which JA regulates maize resistance to U. maydis infection has not been fully clarified. This study selected the disease-resistant variety Qi319 and the disease-susceptible variety Ye478 as experimental materials to systematically investigate the regulatory role of JA in the maize-U. maydis interaction. Initially, the optimal treatment concentrations of JA and acid inhibitor ibuprofen (IBU) were determined through a concentration gradient experiment. Based on this, a comprehensive approach involving cytological observation, physiological and biochemical analysis and molecular biology techniques was employed to explore the effects of JA treatment on maize defense enzyme activity, cell structure integrity and disease resistance-related gene expression. Furthermore, by combining transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), the JA-mediated disease resistance signaling pathway was deeply analyzed and key regulatory genes were identified. This study not only provides a new theoretical basis for elucidating the mechanism of JA-induced maize resistance to U. maydis, but also lays an important foundation for the development of green prevention and control technologies based on plant immune induction of resistance.

3. Discussion

Jasmonic acid substances (JAs), as important plant defense signaling molecules, have a dual mechanism of action in regulating plant disease resistance. On the one hand, JAs function by activating the endogenous defense system of plants, including promoting the biosynthesis of disease-resistant secondary metabolites (such as phenols, terpenes, etc.) and regulating the expression of disease-resistant genes (such as

PR genes, defense enzyme genes, etc.) [

23,

24]. On the other hand, our experiments confirmed that exogenous JA (0.1 mmol/L) could directly inhibit the mycelial growth of

U. maydis (inhibitory rate up to 19.0%), which is consistent with previous research findings that plant hormones such as salicylic acid (SA), auxin (IAA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) could directly inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria [

25,

26,

27,

28]. It is worth noting that this dual mechanism of action (host defense activation and direct pathogen inhibition) makes JA a highly potential plant immune inducer. Especially in the maize-

U. maydis interaction system. JA may achieve effective prevention and control of

U. maydis by regulating the expression of transcription factors such as WRKY (such as

Zm00001d043062 identified in this study) and glycosyltransferases (such as

Zm00001d052209), simultaneously activating the plant immune system and inhibiting the development of pathogens. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the development of green prevention and control technologies for maize diseases based on JA.

This study found that exogenous JA has a significant inducing effect on maize resistance to

U. maydis and its effect exhibits a clear concentration dependence. By setting up a concentration gradient experiment of 0.01-1 mmol/L, it was confirmed that the 0.1 mmol/L JA treatment showed the optimal inductance effect, and its resistance induction ability was 0.1 mmol/L > 0.5 mmol/L > 1 mmol/L > 0.01 mmol/L in sequence. This result is consistent with the research of Su et al. [

29] on the regulation of defense enzyme activity by JA to inhibit diseases. It is worth noting that the antibody-inducing effect of JA at an excessively high concentration (1 mmol/L) decreased instead, suggesting that there may be a feedback regulation mechanism in the JA signaling pathway. To verify the necessity of the JA signaling pathway, treatment with IBU revealed that 3 mmol/L IBU significantly inhibited plant disease resistance (

p<0.01), and significant increase in disease index. These positive and negative experimental evidences collectively indicate that the integrity of the endogenous JA signaling pathway is crucial for maize resistance to

U. maydis. Exogenous application of JA at appropriate concentrations (especially 0.1 mmol/L) can effectively activate the plant defense system, but its inducing effect is concentration-specific, and too high a concentration may lead to downregulation of the defense response, providing an important theoretical basis for the precise application of JA in maize disease prevention and control.

Research has shown that when plants are infected by pathogenic bacteria, they enhance their disease resistance by activating the defense enzyme system [

30]. As a core component of the plant defense signaling network, JA can effectively regulate the synthesis of various defense-related substances [

31,

32]. This experiment found that after treating maize plants with 0.1 mmol/L JA, the activities of PPO, POD, and β-1,3-GA enzymes in the leaves were significantly increased compared to the CK (

P<0.05), while the PAL activity increased but did not reach a significant level. This is consistent with the previous research results that JA can induce an increase in the activities of defense enzymes such as PPO and PAL [

33]. In addition, MDA, as a key indicator of membrane lipid peroxidation, its content changes can reflect the degree of damage to plant cell membranes. This experiment found that JA treatment significantly reduced the MDA content in maize leaves, which is consistent with Gao Qianqian's research on the reduction of MDA content in non-heading Chinese cabbage by salicylic acid (SA) treatment [

34], indicating that JA at an appropriate concentration can enhance maize resistance to

U. maydis by reducing membrane lipid peroxidation damage. These results collectively demonstrate that JA enhances maize disease resistance through a dual mechanism (activating the defense enzyme system and reducing membrane damage), providing new experimental evidence for a deeper understanding of JA-induced plant immune mechanisms.

The structural characteristics of plant cell tissues serve as important physical defense barriers, playing a crucial role in the early stages of disease resistance [

35]. Through paraffin section observation in this study, it was found that after maize was infected by

U. maydis, the susceptible material 478 exhibited typical susceptible tissue structure characteristics: abnormal enlargement of mesophyll cells, disordered garland structure, division of bundle sheath cells, and thickening of spongy tissue. However, the disease-resistant material Qi 319 maintained a tight and orderly arrangement of palisade tissues and a complete garland structure. This result is highly consistent with the discovery made by Pu [

36] in the powdery mildew system. It is worth noting that JA treatment can significantly alleviate the structural damage caused by pathogen infection. The mechanism of action may involve: (1) Promoting the growth of epidermal cells to form a physical barrier, hindering the infection of mycelium into the vascular bundle sheath and mesophyll tissue. (2) Maintain the tight arrangement of the palisade tissue and enhance the mechanical strength of the cell wall. (3) Inhibit the excessive proliferation of spongy tissue and maintain the normal morphology of mesophyll cells. These findings not only confirm the significant role of cellular tissue structure characteristics in maize resistance to

U. maydis, but also provide histological evidence for analyzing the disease resistance mechanism induced by JA, laying an important foundation for subsequent in-depth studies. Ghareeb et al. [

37]'s study on inflorescence regeneration also suggests that plants may respond to pathogen infection by restructuring their tissue structure, which is consistent with the findings of this study.

In terms of disease resistance regulatory mechanisms, the PP2C family protein phosphatase gene

Zm00001d009620 specifically upregulated in disease-resistant varieties may indirectly inhibit reactive oxygen species production by negatively regulating the ABA signaling pathway. This finding is consistent with the functions of

PP2C genes (such as

ABI1 and

HAB1) in Arabidopsis thaliana [

38,

39,

40]. In terms of the molecular strategies by which pathogenic bacteria interfere with host defense, the significantly downregulated WRKY transcription factor gene

Zm00001d043062 in the susceptible species suggests that the

U. maydis may target and inhibit the expression of related disease-resistant genes activated by this factor through the secretion of effector proteins [

41,

42]. Thereby blocking the expression of the activated PTI/ETI defense genes [

43,

44], this discovery provides a new perspective on the mechanism of action of pathogenic effectors.

In the JA-induced defense network, the upregulated cytokinin-O-glucosyltransferase gene

Zm00001d052209 of the susceptible varieties may regulate hormone homeostasis through glycosylation modification and affect JA signaling efficiency [

45,

46]. Meanwhile, the β-glucuronosyltransferase gene

Zm00001d040047 may be involved in the synthesis of cell wall polysaccharides or defend against metabolite modification [

47,

48], and it is speculated that it regulates disease resistance by promoting the thickening of the cell wall. It is particularly worth noting the upregulated expression of the RING zinc finger protein gene

Zm00001d051460 in disease-resistant varieties. Considering the key role of Ring-like E3 ubiquitin ligases in regulating the stability of COI1 protein, a core component of JA signaling [

49,

50], we speculate that this gene may precisely regulate the intensity and temporal dynamics of the JA signaling pathway through the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and this mechanism may be an important factor determining the differences in disease resistance among varieties. Additionally, the upregulated expression of the calmodulin gene

Zm00001d047618 in susceptible varieties indicates that disease resistance-related calcium signaling is activated. This gene is associated with promoting the increase of calcium ions, which interact with the production of reactive oxygen species. Furthermore, this gene is involved in the expression of

LOX gene in the JA synthesis pathway [

51]. These findings construct an innovative theoretical framework: JA forms a precisely coordinated disease resistance defense system by integrating multi-level networks such as PP2C-mediated ABA signal regulation, WRKY transcriptional cascade, metabolic remodeling involving glycosyltransferases, ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation and calcium signal activation. This provides a new theoretical paradigm for understanding plant immune mechanisms and lays a molecular foundation for the design of disease-resistant breeding strategies.

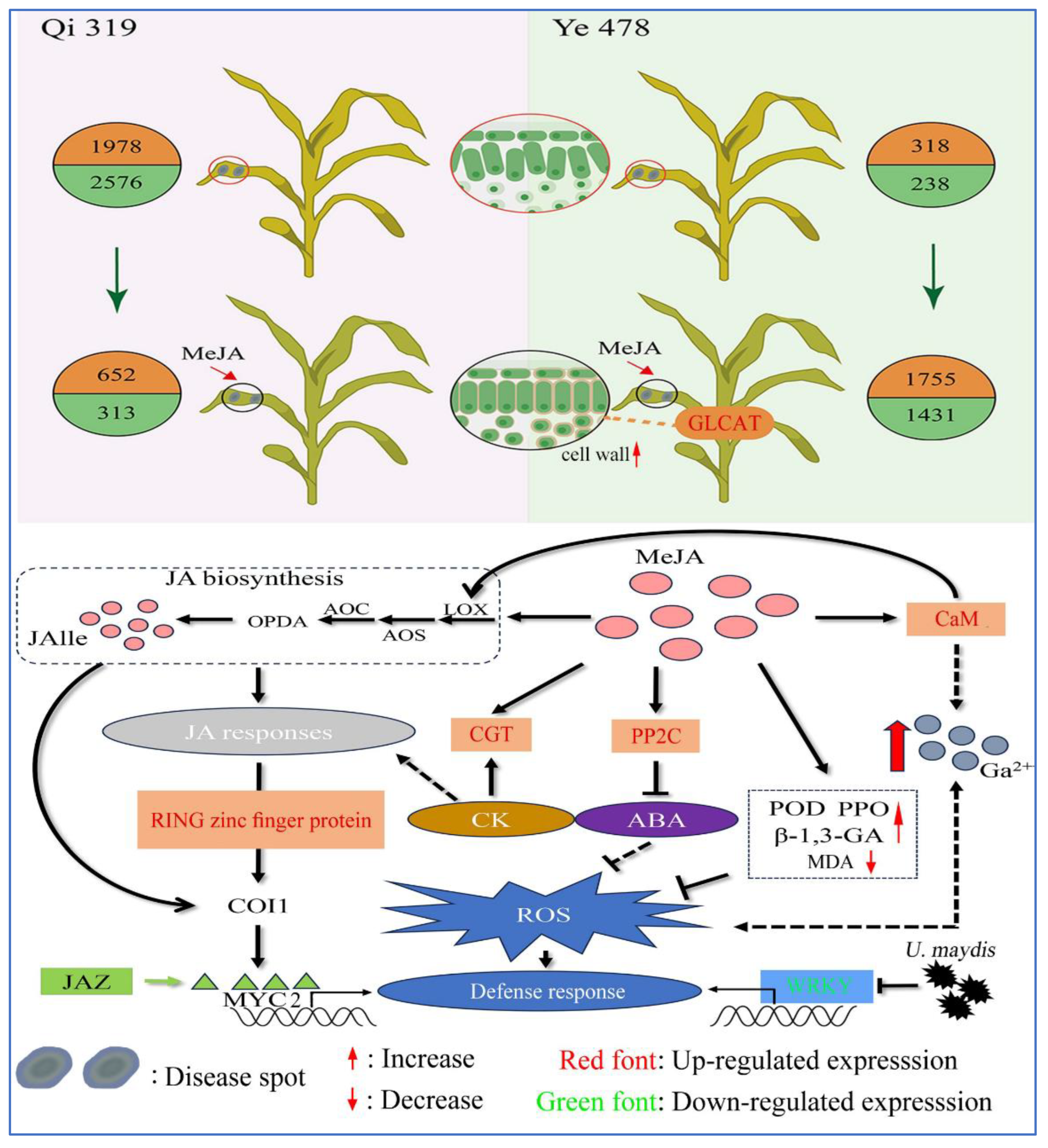

4. Conclusion

At the cellular tissue structure level, JA treatment can maintain the tight arrangement of palisade tissue and induce

GLCAT expression to strengthen the cell wall, forming an effective physical barrier (

Figure 10). This discovery provides direct evidence for understanding plant structural resistance. At the molecular regulation level, omics analysis revealed that JA coordinates disease resistance through a complex gene expression regulatory network. Two important findings deserve special attention: (1) Under the stress of

U. maydis, the resistant variety Qi319 demonstrates its inherent resistance advantage through more significant transcriptome reprogramming (1978 genes up-regulated and 2576 genes down-regulated). (2) Under JA induction, the susceptible variety Ye478 exhibits a stronger transcriptome response (1755 genes up-regulated and 1431 genes down-regulated), suggesting that JA may enhance resistance by compensating for the defects in defense signal transduction in susceptible varieties. In-depth analysis revealed that MeJA enhances maize defense capabilities through a triple-action mechanism: on the one hand, it induces the synthesis of endogenous JA to activate the JA signaling pathway, leading to the expression of disease resistance genes under the JA synthesis pathway [

52]. On the other hand, JA mainly induces the upregulation of genes related to ABA and CK pathways, activating the defense enzyme system (PPO, POD, and β-1,3-GA enzyme activities significantly increased), effectively reducing membrane lipid peroxidation damage (MDA content significantly decreased), and activate the calcium signaling disease resistance system. These pathways work synergistically and the three hormone pathways interact with each other to eliminate or affect the production of reactive oxygen species, thereby enhancing antioxidant resistance, including negatively regulating the ABA signaling pathway (

PP2C gene), activating defense-related transcription factors (

WRKY gene), modifying hormone activity (

CGT gene), regulating protein stability (

RING zinc finger protein), and activating the calcium signaling system (

CaM gene); On the other hand, it promotes disease resistance by downregulating pathogen-induced related transcription factors to negatively activate the expression of related disease resistance genes. These findings not only confirm the importance of JA as a core defense hormone but also reveal the molecular basis of variety resistance differences. Based on these results, we propose an innovative hypothesis: JA may partially compensate for the inherent defects in the defense pathways of susceptible varieties through a "signal compensation mechanism," providing new ideas for crop disease resistance improvement. Future research should focus on: (1) Functional verification of key candidate genes (2) The cross-regulation mechanism of the JA signal network and other defense pathways; (3) The genetic basis of species-specific defense responses. These works will promote the further development of theoretical and applied research on crop disease resistance.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Experimental Materials

The maize materials used were the susceptible variety Ye478 and the resistant variety Qi319, provided by the Maize Research Group of Gansu Agricultural University.

Test strain: U. maydis, strain number 5.208, purchased from the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. U. maydis powder was provided by the Maize Research Group of Gansu Agricultural University.

Preparation of inoculum: The teliospores are crushed, collected through a 100-mesh sieve to obtain fungal powder and 10 mL of water is added per 1 g of fungal powder. Then, it is filtered through a 300-mesh sieve, and it should be prepared immediately before use.

PDA medium: 500 mL of potato extract, 10.0 g of glucose, 1.5 g of KH2PO4, 1.5 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 7.5 g of agar and trace vitamin B1, adjusted to pH 6.0.

JA: liquid, purity 98%, purchased from Gansu Yuanxin Biotechnology.

IBU: solid, purchased from Gansu Aierwei Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.

5.2. Treatment Methods with JA and IBU

Experimental study on the inhibitory effect of JA on the mycelial growth of

U. maydis: Prepare JA solutions of different concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mmoL/L), sterilize them through a 0.22 μm bacterial filter, then add them to PDA medium and mix well. Use the same amount of sterile as the control (CK). In the ultra-clean workbench, bacterial plates with a diameter of 5 mm were inoculated in the center of the culture medium and placed in an artificial climate chamber at 25℃ for cultivation. The colony expansion area was measured at 24 h and 48 h respectively and the inhibition rate was calculated [

53].

Plant treatment experiment: prepare JA solutions (0.01, 0.1, 0.5 and 1 mmoL/L) and IBU solutions (0.1, 1, 3, and 5 mmoL/L), and add 0.05% Tween 20 as a surfactant. When the maize plants reach the six-leaf stage, inoculate with

U. maydis by injection [

54]. After 6 hours of inoculation, treat with JA solution and IBU solution, using a sprayer to evenly spray the leaves until they are wet. The control group is sprayed with an equal amount of distilled water containing 0.05% Tween 20. After 7 days of treatment, assess the disease incidence in the maize plants and calculate the disease index (DI) and the induced resistance effect [

55]. Each treatment has three biological replicates, with 10 plants in each replicate. The grading criteria for

U. maydis are shown in

Supplementary Table S5.

Disease index(DI=∑(number of diseased plants at each level ×level of disease)×100/ (highest level of disease×total number of plants surveyed) (1)

Induced resistance effect(%)= (control disease index−treated disease index)/ (control disease index) ×100 (2)

5.3. Determination of Maize Defense-Related Enzyme Activity

Maize plants at the six-leaf stage were inoculated with

U. maydis. Six hours after inoculation, 0.1 mmoL/L JA (determined to have the best resistance effect through preliminary screening) is sprayed on the maize leaves. The experiment includes six treatments: Qi319 uninoculated control (QCK-U), Qi319 inoculated control (QCK-I), Qi319 inoculated + JA treatment (QJA-I), Ye478 uninoculated control (YCK-U), Ye478 inoculated control (YCK-I) and Ye478 inoculated + JA treatment (YJA-I). Each treatment has three biological replicates. Samples were collected at five time points after treatment: 0 h, 12 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent enzyme assays. The extraction of crude enzyme solution follows the method of Kibiza et al. [

56]. Peroxidase (POD) activity is measured using the guaiacol method [

57], phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity is determined using the phenylalanine colorimetric method [

58], polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity is measured using the catechol method [

59], malondialdehyde (MDA) content is determined by referring to the method of Chen et al. [

60], β-1,3 Glucanase (β-1,3-GA) activity is measured using the Solarbio β-1,3 glucanase activity detection kit.

5.4. Cytological Analysis of Maize Leaves

To analyze the effects of JA treatment on the cellular structure of maize leaves, we performed cytological observations using paraffin sectioning coupled with hexamine silver staining [

61]. The focus was on observing the morphology of mesophyll cells, vascular bundle structure and pathogen infection. This method can clearly show the impact of JA treatment on the cellular structure of maize leaves and the progression of pathogen infection.

5.5. Total RNA Extraction and RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from maize leaves using the AccuRNA RNA Extraction Kit (Hunan AccuRNA Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). After passing the quality control, samples were submitted to Biomarker Technologies Corporation (Beijing) for transcriptome sequencing analysis. The experimental workflow consisted of: (1) Library preparation using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit; (2) Paired-end sequencing (150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform; (3) Raw data quality control using Fastp software. High-quality clean data were then aligned to the maize reference genome (ZmB73_5a.59) using HISAT2 software. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified with DESeq2 (thresholds: |log2FC|≥1 and FDR<0.01). Functional annotation was performed through GO analysis using EggNOG-mapper and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using KOBAS (P-value<0.05). Finally, a gene co-expression network was constructed using Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), with key modules (correlation >0.7) selected and visualized using Cytoscape (3.10.0) software.

5.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

To verify the reliability of the transcriptome sequencing results, six randomly selected genes were subjected to qRT-PCR verification. The experimental procedure was conducted as follows: First, using maize Actin gene as the internal reference, total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA reference using the AccuRT Reverse Transcription Kit (Cat. No. ACCRT-002; Hunan AccuRNA Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer 5.0 software (primer sequences listed in

Table 2), with three biological replicates performed for each gene. qRT-PCR reactions were carried out on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System under the following thermal cycling conditions: 95℃ pre-denaturation for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95℃ denaturation for 5 sec and 60℃ annealing/extension for 30 sec. Finally, the relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

-ΔΔCT method and correlated with RNA-seq data (R² > 0.85). The results demonstrated strong concordance between qRT-PCR and RNA-seq data, confirming the reliability of the transcriptome sequencing results.

5.7. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD post-hoc test (P<0.05) was conducted to determine significant differences among treatments. Data visualization was implemented using Origin 2024 (OriginLab, USA) for generating high-quality statistical graphs. The gene co-expression network derived from WGCNA analysis was visualized using Cytoscape 3.10.0 to illustrate interactions among core genes. All statistical analyses were performed with a 95% confidence interval to ensure the reliability and scientific validity of the results.

Figure 1.

Changes in the activity of defense enzymes related to maize resistance to U. maydis under different treatments. Different lowercase letters represent the same time with significant difference under different treatments (p< 0.05). QCK-U: Qi319 uninoculated control; QCK-I: Qi319 inoculated control; QJA-I: Qi319 inoculated + JA treatment; YCK-U: Ye478 uninoculated control; YCK-I: Ye478 inoculated control; YJA-I: Ye478 inoculated + JA treatment. A. POD activity; B: PPO activity; C: β-1,3-GA activity; D: PAL activity; E: MDA content.

Figure 1.

Changes in the activity of defense enzymes related to maize resistance to U. maydis under different treatments. Different lowercase letters represent the same time with significant difference under different treatments (p< 0.05). QCK-U: Qi319 uninoculated control; QCK-I: Qi319 inoculated control; QJA-I: Qi319 inoculated + JA treatment; YCK-U: Ye478 uninoculated control; YCK-I: Ye478 inoculated control; YJA-I: Ye478 inoculated + JA treatment. A. POD activity; B: PPO activity; C: β-1,3-GA activity; D: PAL activity; E: MDA content.

Figure 2.

Cell structure of maize leaves under JA treatment. A1-A5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h QJA-I leaf transverse section structure; B1-B5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h YJA-I leaf transverse section structure; C1-C5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h QCK-I leaf transverse section structure; D1-D5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h YCK-I leaf transverse section structure; E1-E5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h QCK-U leaf transverse section structure; F1-F5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h YCK-U leaf transverse section structure; EP: Epidermis; BSC: Bundle sheath cells; MC: Mesophyll cells; Scale bar: 50 μm.

Figure 2.

Cell structure of maize leaves under JA treatment. A1-A5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h QJA-I leaf transverse section structure; B1-B5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h YJA-I leaf transverse section structure; C1-C5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h QCK-I leaf transverse section structure; D1-D5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h YCK-I leaf transverse section structure; E1-E5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h QCK-U leaf transverse section structure; F1-F5: 0, 12, 48, 72, 96 h YCK-U leaf transverse section structure; EP: Epidermis; BSC: Bundle sheath cells; MC: Mesophyll cells; Scale bar: 50 μm.

Figure 3.

Number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs across different treatments and venen analysis. A: Number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs across different treatments; B: Venn analysis of expressed genes in different treatment groups.

Figure 3.

Number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs across different treatments and venen analysis. A: Number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs across different treatments; B: Venn analysis of expressed genes in different treatment groups.

Figure 4.

GO analysis of DEGs between two varieties under different treatments. A: GO analysis of DEGs between QCK-U and QCK-I, and between QCK-I and QJA-I; B: GO analysis of DEGs between YCK-U and YCK-I, and between YCK-I and YJA-I.

Figure 4.

GO analysis of DEGs between two varieties under different treatments. A: GO analysis of DEGs between QCK-U and QCK-I, and between QCK-I and QJA-I; B: GO analysis of DEGs between YCK-U and YCK-I, and between YCK-I and YJA-I.

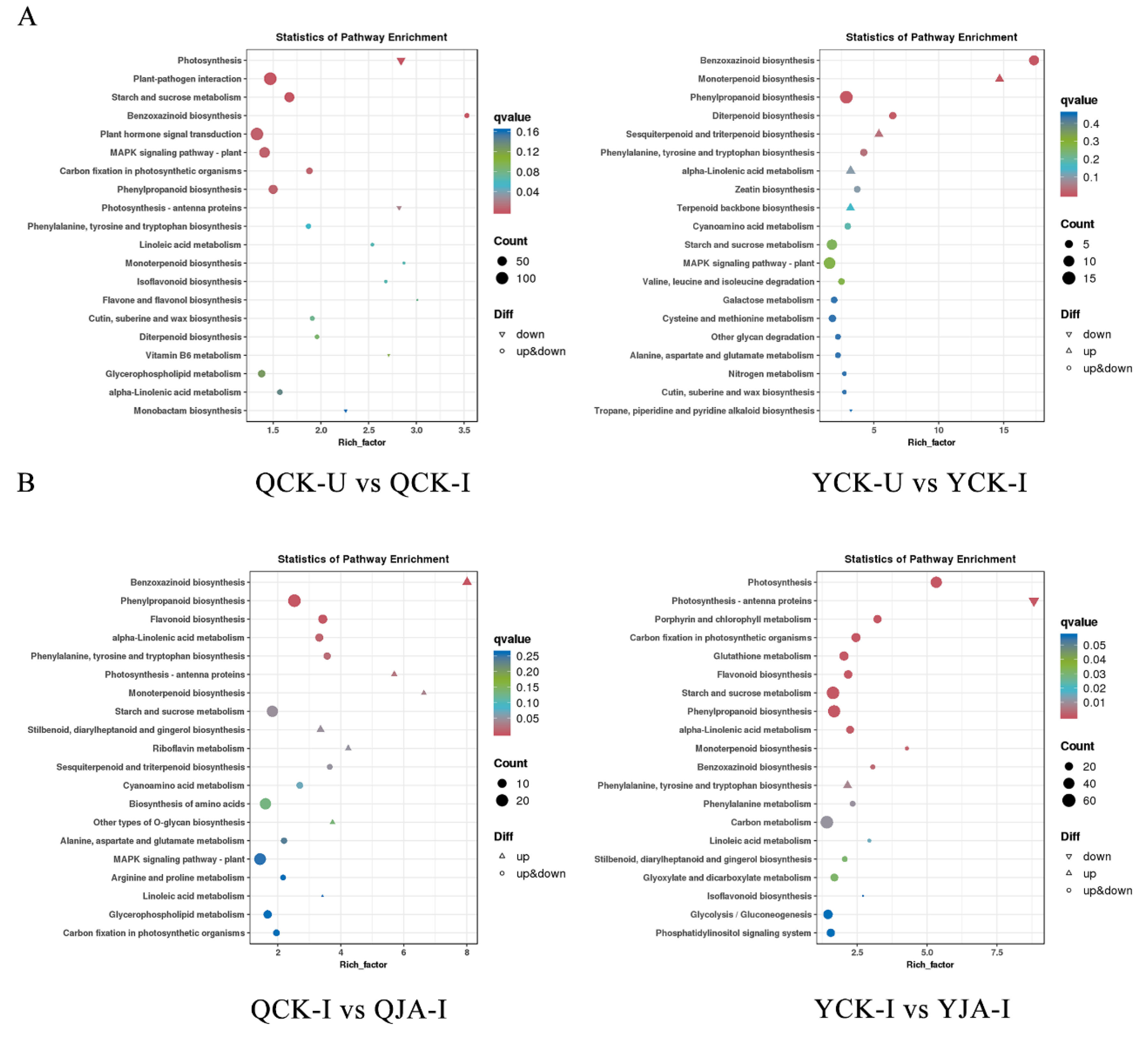

Figure 5.

KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs for two varieties under different treatments. A: KEGG pathways of DEGs for QCK-U vs QCK-I and QCK-I vs QJA-I; B: KEGG pathways of DEGs for YCK-U vs YCK-I and YCK-I vs YJA-I.

Figure 5.

KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs for two varieties under different treatments. A: KEGG pathways of DEGs for QCK-U vs QCK-I and QCK-I vs QJA-I; B: KEGG pathways of DEGs for YCK-U vs YCK-I and YCK-I vs YJA-I.

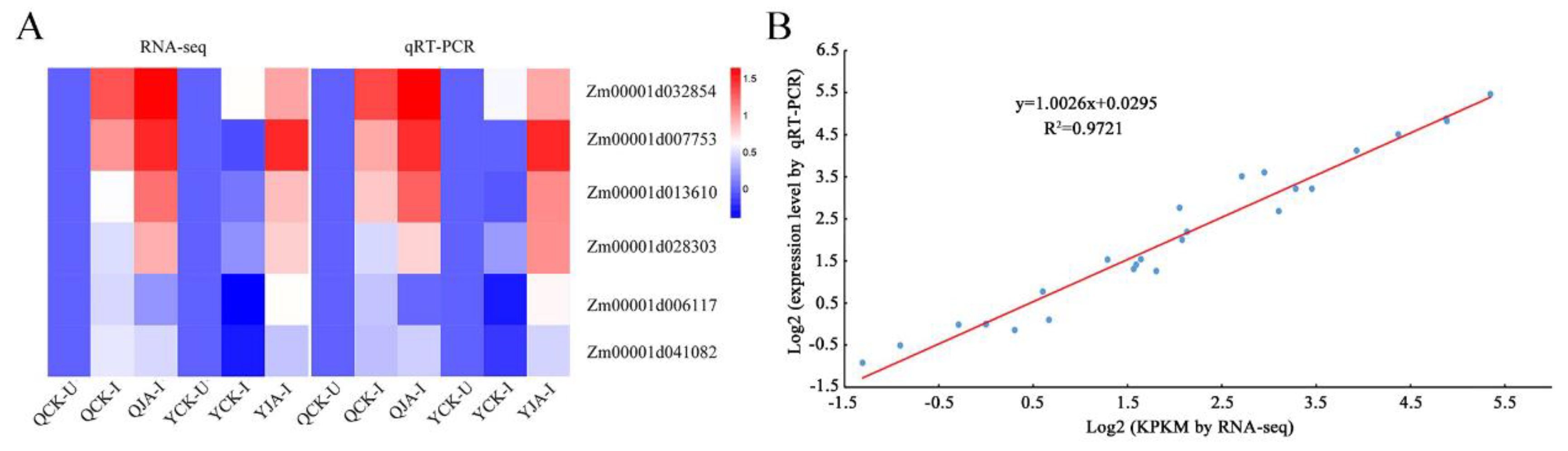

Figure 6.

The expression patterns of 6 selected genes identified by RNA-seq was verified by qRT-PCR. A: Heat map showing the expression changes (logy-fold change) in response to the QCK-U, QCK-I, QJA-I, YCK-U, YCK-I, and YJA-I treatments for each candidate gene as measured by RNA-seq and qRT-PCR; B: Scatter plot showing the changes in the expression (logy-fold change) of selected genes based on RNA-seq via qRT-PCR. Gene expression levels are indicated by colored bars.

Figure 6.

The expression patterns of 6 selected genes identified by RNA-seq was verified by qRT-PCR. A: Heat map showing the expression changes (logy-fold change) in response to the QCK-U, QCK-I, QJA-I, YCK-U, YCK-I, and YJA-I treatments for each candidate gene as measured by RNA-seq and qRT-PCR; B: Scatter plot showing the changes in the expression (logy-fold change) of selected genes based on RNA-seq via qRT-PCR. Gene expression levels are indicated by colored bars.

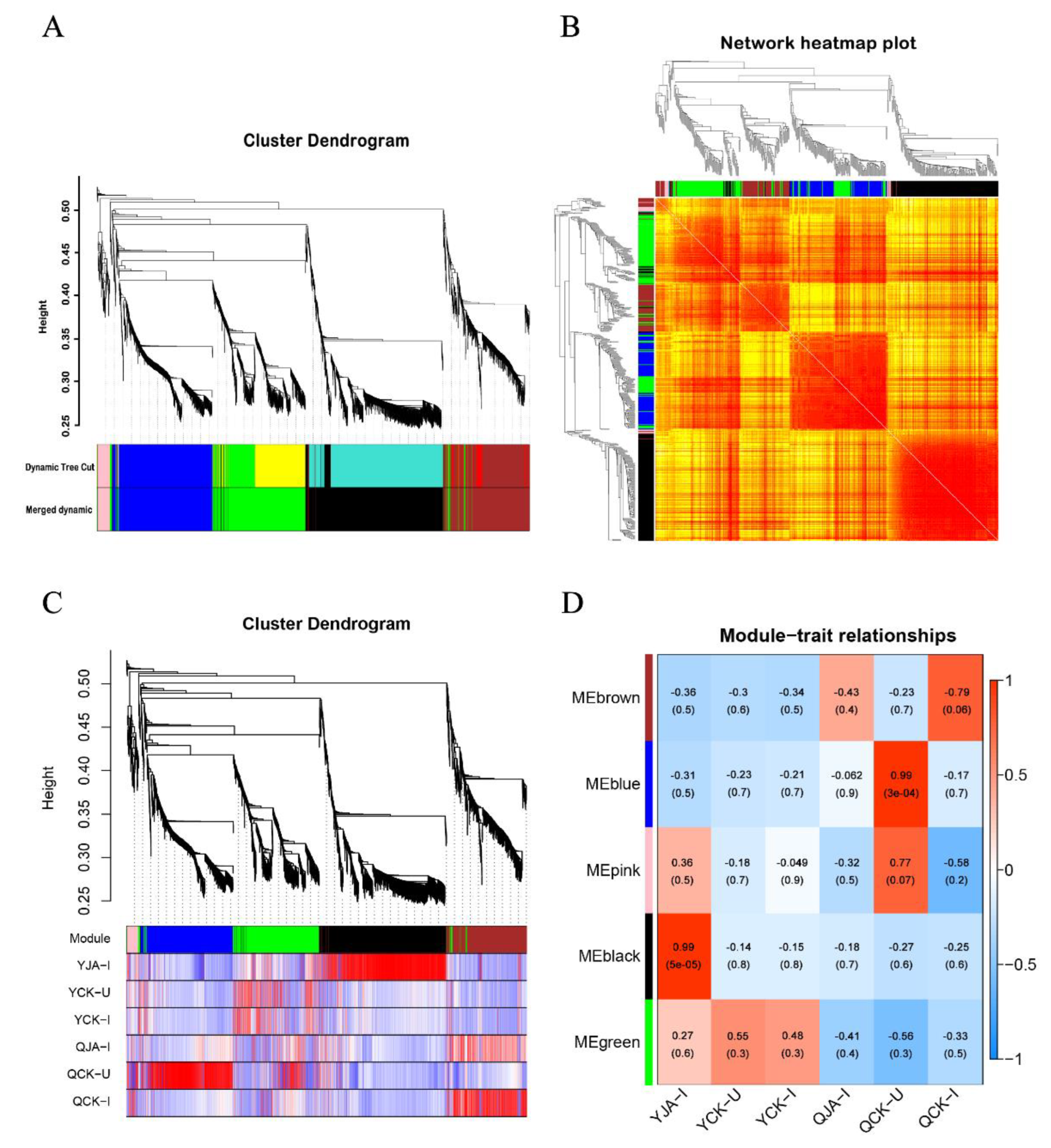

Figure 7.

Module construction based on WGCNA. A: Gene module clustering analysis; B: Module gene clustering heatmap; C: Gene dendrogram and correlation heatmap between samples; D: Correlation heatmap between modules and samples.

Figure 7.

Module construction based on WGCNA. A: Gene module clustering analysis; B: Module gene clustering heatmap; C: Gene dendrogram and correlation heatmap between samples; D: Correlation heatmap between modules and samples.

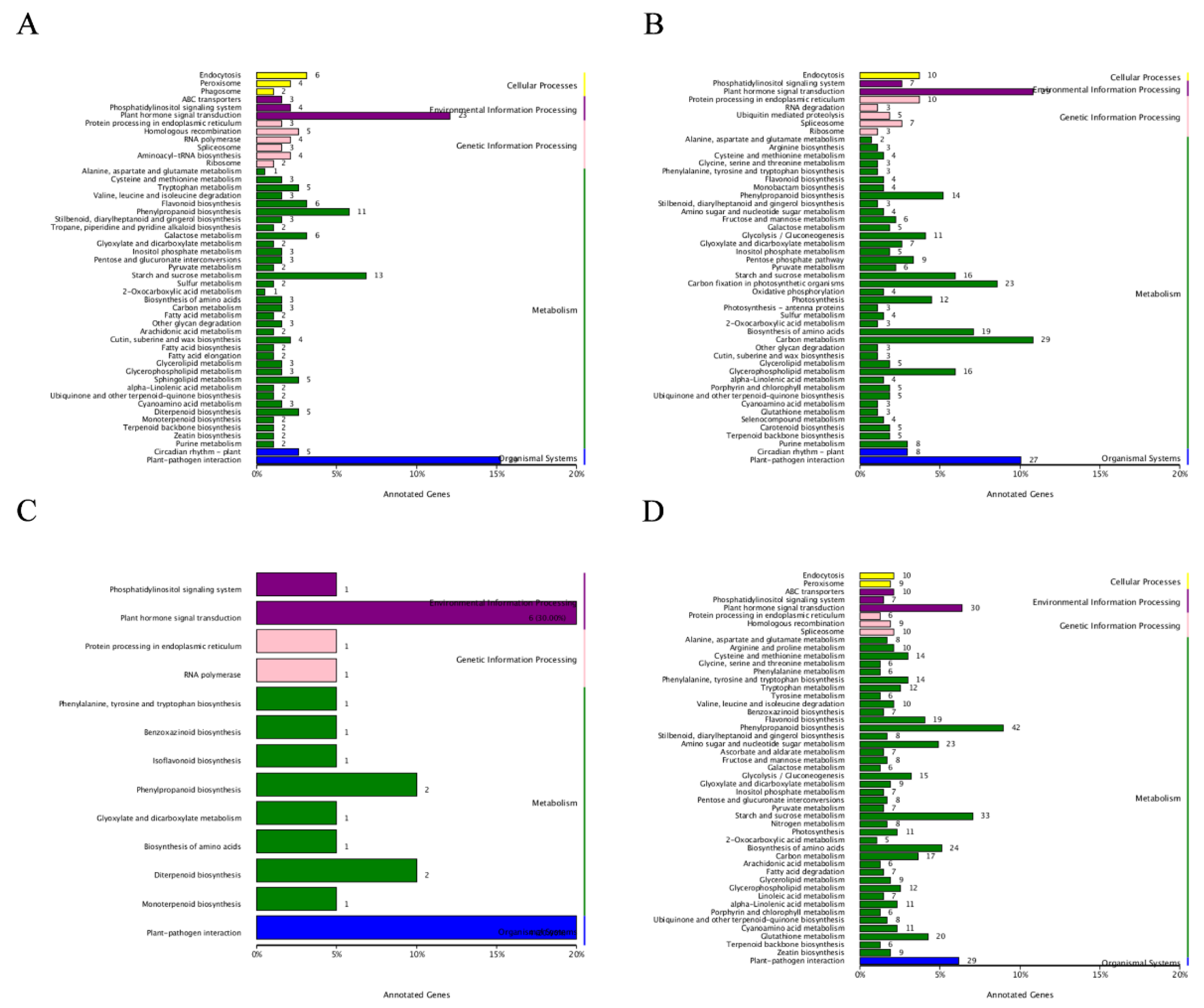

Figure 8.

KEGG enrichment analysis of target modules. (A): Brown module KEGG; (B): Blue module KEGG; (C): Pink module KEGG; (D): Black module KEGG.

Figure 8.

KEGG enrichment analysis of target modules. (A): Brown module KEGG; (B): Blue module KEGG; (C): Pink module KEGG; (D): Black module KEGG.

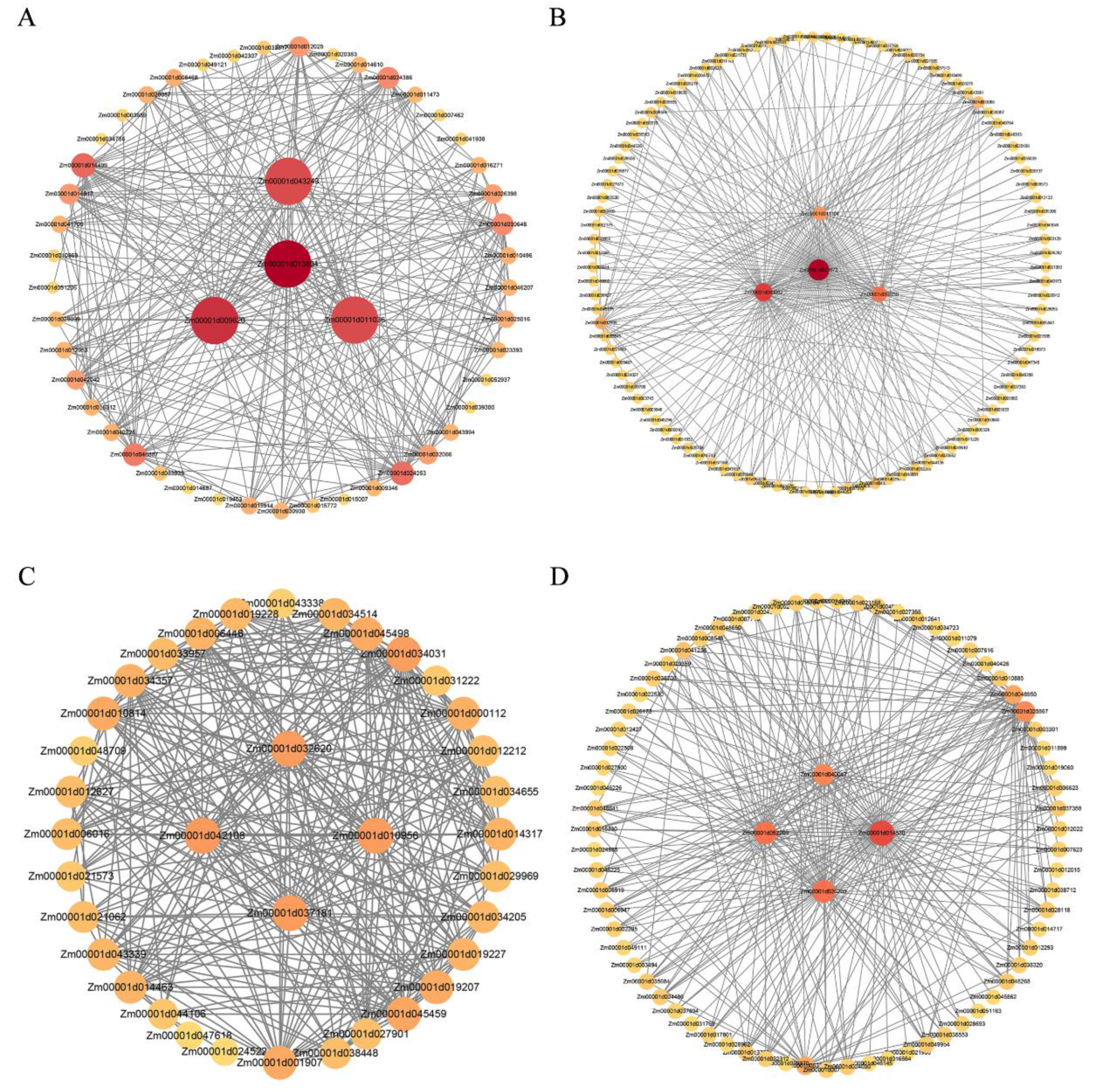

Figure 9.

Co-expression network of target modules. A: Brown module; B: Blue module; C: Pink module; D: Black module. The inner circle represents the core genes within the module, while the outer circle represents the associated genes of the core genes. The correlation between genes is connected by edges (lines).

Figure 9.

Co-expression network of target modules. A: Brown module; B: Blue module; C: Pink module; D: Black module. The inner circle represents the core genes within the module, while the outer circle represents the associated genes of the core genes. The correlation between genes is connected by edges (lines).

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the mechanism of JA regulating maize resistance to U. maydis.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the mechanism of JA regulating maize resistance to U. maydis.

Table 1.

Candidate genes and their functional annotations

Table 1.

Candidate genes and their functional annotations

| Gene ID |

Gene Name |

Gene Annotation |

| Zm00001d009620 |

PP2C |

Protein phosphatase 2C |

| Zm00001d043062 |

WRKY |

transcription factor |

| Zm00001d052209 |

CGT |

Cytokinin-O-glucosyltransferase |

| Zm00001d040047 |

GLCAT |

β-glucuronosyltransferase |

| Zm00001d051460 |

RING zinc finger protein |

RING zinc finger protein |

| Zm00001d047618 |

CaM |

calmodulin |

Table 2.

qRT-PCR primer sequence.

Table 2.

qRT-PCR primer sequence.

| Gene |

Forward primer (5'-3') |

Reverse primer (5'-3') |

| Actin |

TGAAACCTTCGAATGCCCAG |

GATTGGAACCGTGTGGCTCA |

| Zm00001d032854 |

CTATGGAGTCCTCTTTAGCG |

ACTTCTGAATGATGGAGTCG |

| Zm00001d007753 |

GGATTCACCACTTTCCTCAA |

AATACACGGCAGTACAAGTT |

| Zm00001d013610 |

GAGCTACGAGATCACCTTCT |

TATACGTACGCAAACACGAG |

| Zm00001d028303 |

ACCGTGTATAGCTAGTGGTA |

CTCCGGCCGTAGCCA |

| Zm00001d006117 |

TGTGCAAAGACACCTTATGA |

TATTTCCACAGTTCCACCAG |

| Zm00001d047618 |

GTGCGGAGTACTGTATTCTT |

GCCATCATGCGAACTTTTTA |