Submitted:

24 September 2023

Posted:

25 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Host Plant and Infection

2.2. Spore Germination

2.3. qRT-PCR

2.4. Extraction and Measurement of SA from Cucumber Leaves

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

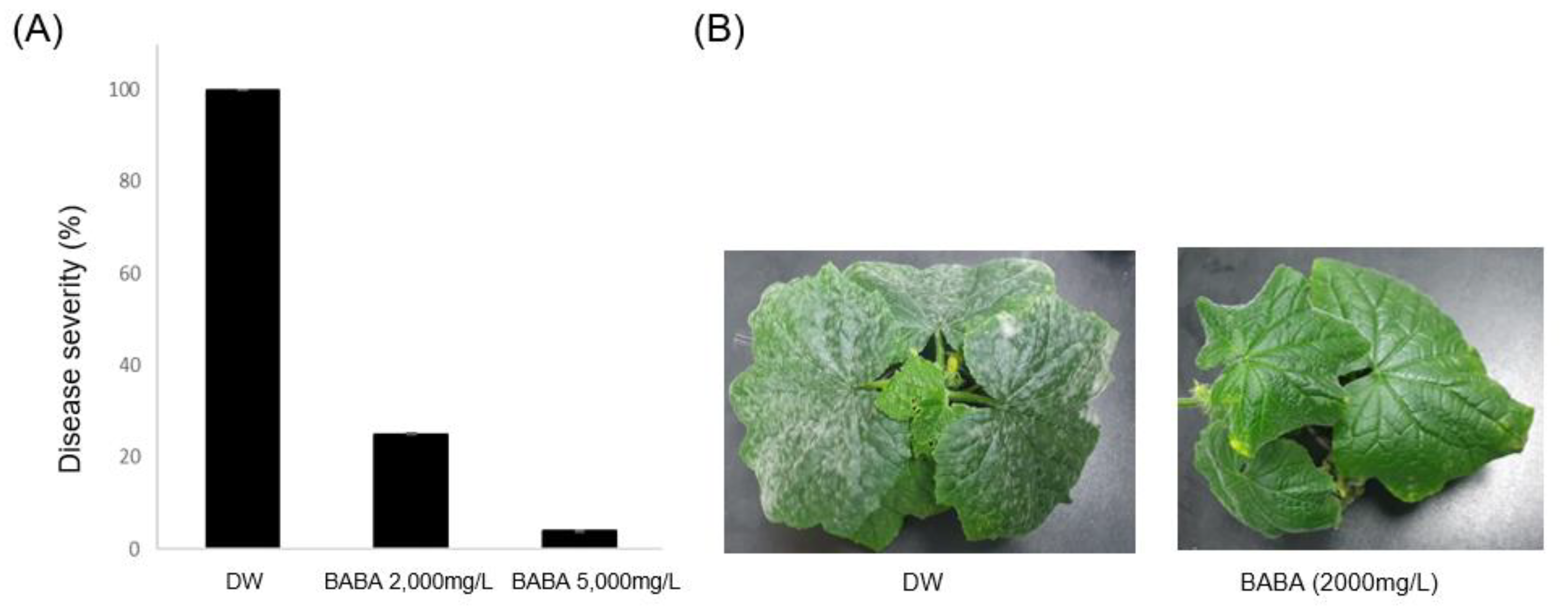

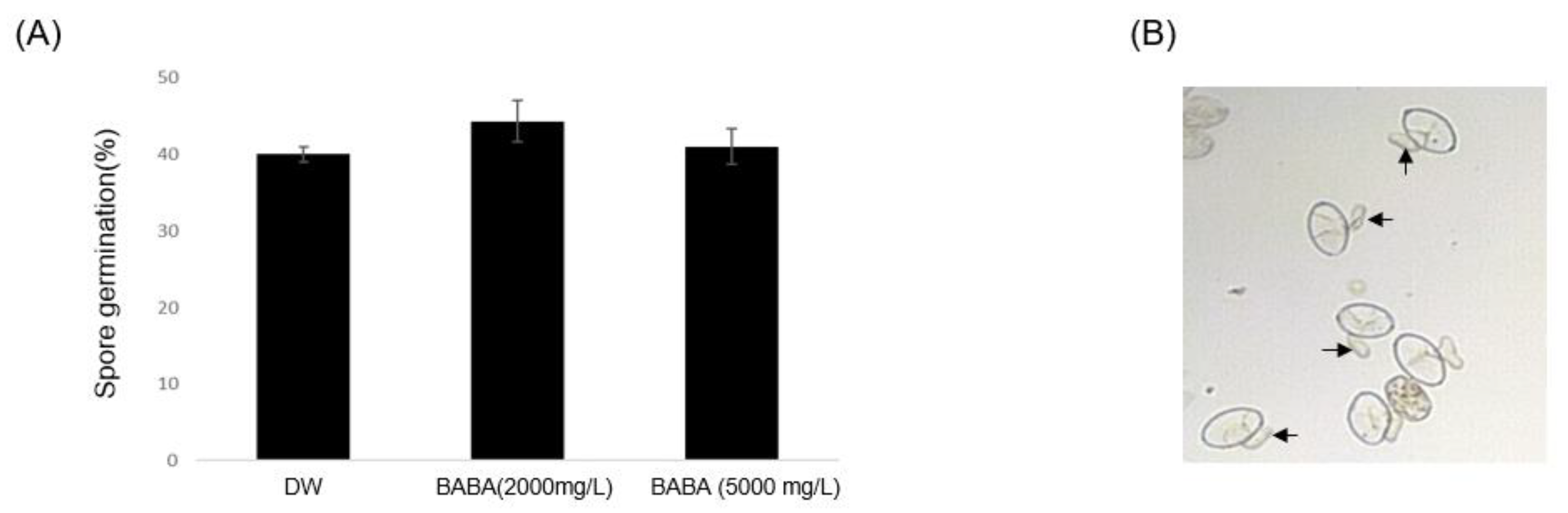

3.1. BABA Inhibits Cucumber PM Disease

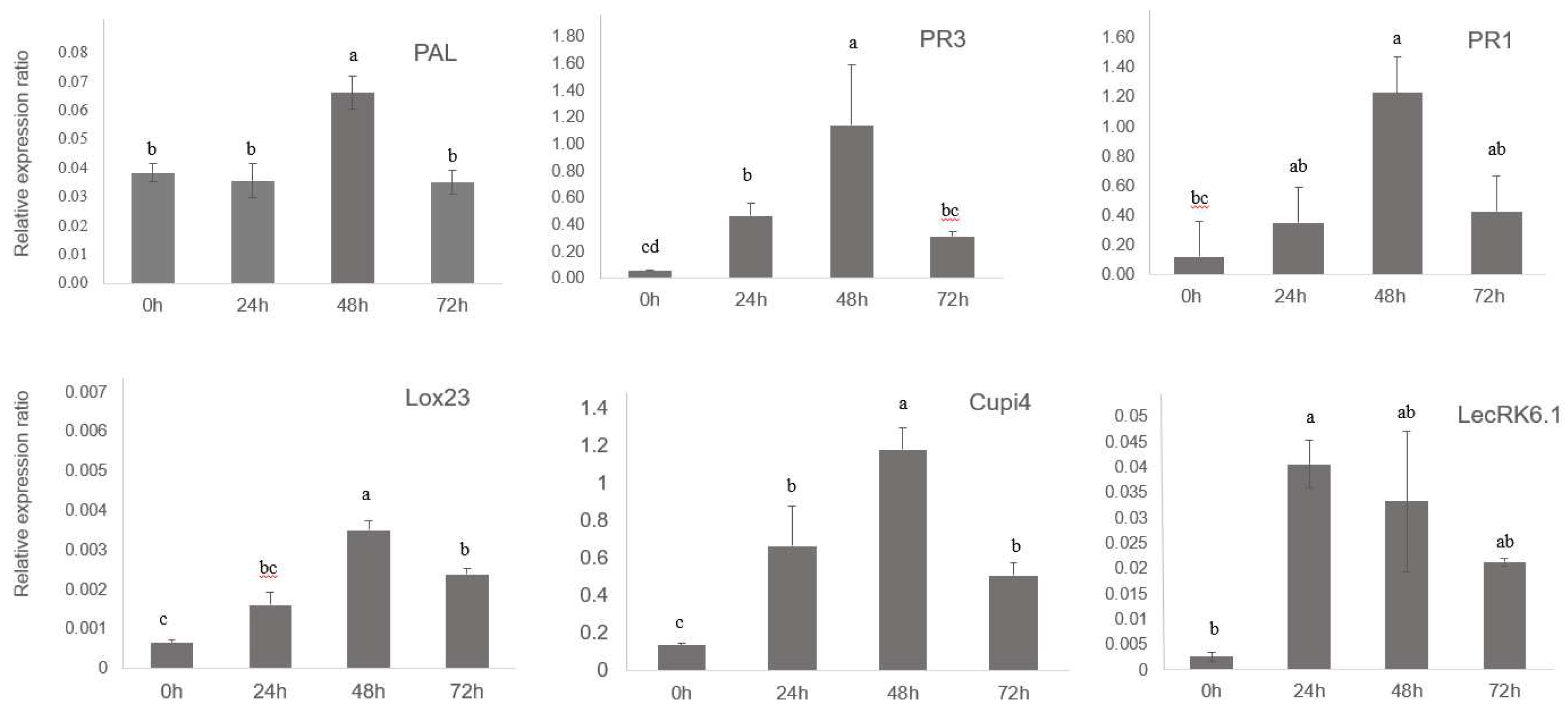

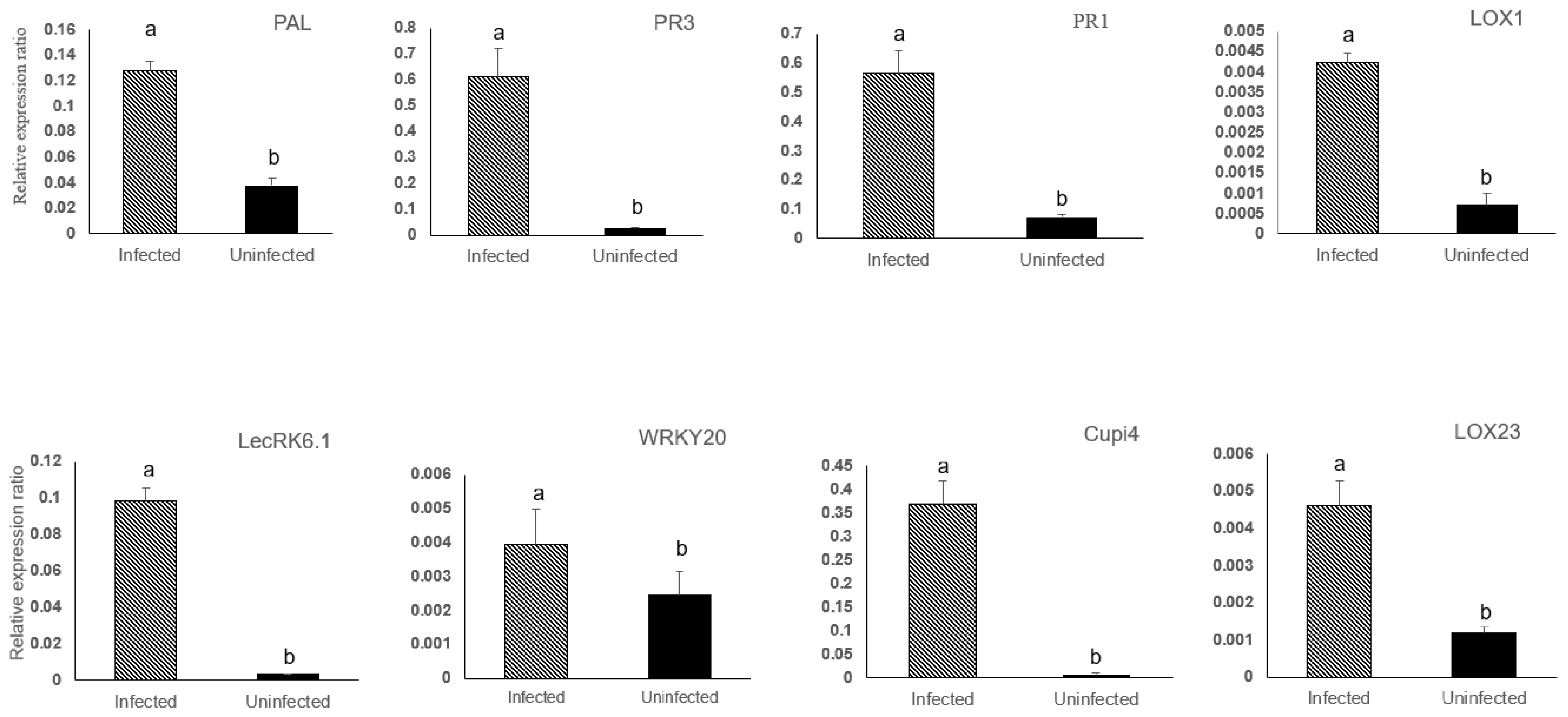

3.2. Defense Genes in Cucumber Were Upregulated by BABA and PM Infection

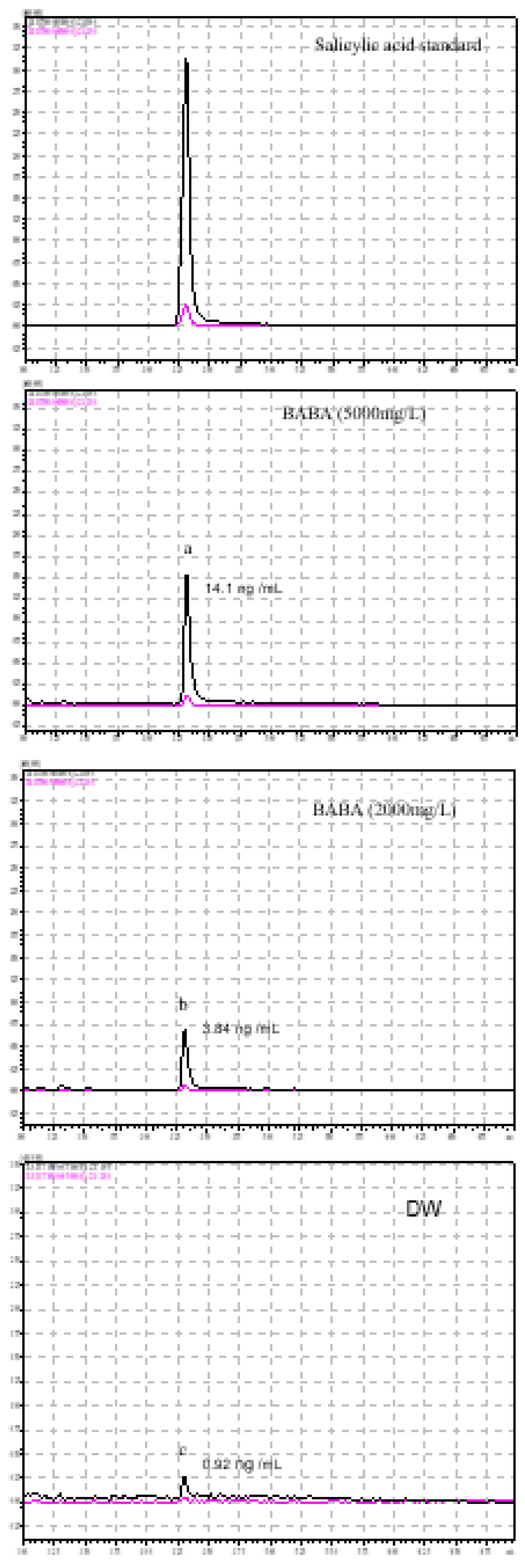

3.3. BABA Iduces SA Accumulation in Cucumber

4. Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Reuveni, M.; Agapov, V.; Reuveni, R.; et al. A foliar spray of micronutrient solutions induces local and systemic protection against powdery mildew (Sphaerotheca fuliginia) in cucumber plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1997, 103, 581-588. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, E.J.; Ali, S.; Byamukama, E.; Yen, Y.; Nepal, M.P.; et al. Disease resistance mechanisms in plants. Genes 2018, 9, 339. [CrossRef]

- Knoth, C.; Ringler, J.; Dangl, J.L.; Eulgem, T.; et al. Arabidopsis WRKY70 is required for full RPP4-mediated disease resistance and basal defense against Hyaloperonospora parasitica. Molecular plant-microbe interactions, 2007, 20, 120-128. [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Xie, B.; Li, P.; Mao, Z.; Ling, J.; Shen, H.; Lin, B.; et al. Analysis of the defence-related mechanism in cucumber seedlings in relation to root colonization by nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum CS-20. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 2014, 355, 142-151. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, L.; Golparvar, A. R.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.; Golabadi, M.; et al. Expression analysis of defense-related genes in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) against Phytophthora melonis. Mol. Biol. Rep., 2020, 47, 4933-4944. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Fan, A.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. LecRK-V, an L-type lectin receptor kinase in Haynaldia villosa, plays positive role in resistance to wheat powdery mildew. Plant Biotechnol. J., 2018, 16, 50-62. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S. K.; Jang, H. A.; Kim, J.; Choi, D.; Park, Y. I.; Kwon, S. Y.; et al. Expression of cucumber LOX genes in response to powdery mildew and defense-related signal molecules. Can. J. Plant Sci., 2014, 94, 845-850. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D. S.; Min, K. J.; Kwak, A. M.; Lee, S. Y.;Kang, H. W.; et al. Defense response and suppression of Phytophthora blight disease of pepper by water extract from spent mushroom substrate of Lentinula edodes. Plant Pathol. J., 2017, 33, 264. [CrossRef]

- Stamler, R. A.; Holguin, O.; Dungan, B.; Schaub, T.; Sanogo, S.; Goldberg, N.; Randall, J. J. ; et al. BABA and Phytophthora nicotianae induce resistance to Phytophthora capsici in chile pepper (Capsicum annuum).Plos one,2015, 10, e0128327. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S. K.; Jang, H. A.; Kim, J.; Choi, D.; Park, Y. I.; Kwon, S. Y.; et al. Expression of cucumber LOX genes in response to powdery mildew and defense-related signal molecules. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 2014, 94, 845-850. [CrossRef]

- Jakab, G.; Cottier, V.; Toquin, V.; Rigoli, G.; Zimmerli, L.; Métraux, J. P.; Mauch-Mani, B.; et al. β-Aminobutyric acid-induced resistance in plants. European Journal of plant pathology, 2001, 107, 29-37. [CrossRef]

- Zeighaminejad, R.; Sharifi-Sirchi, G. R.; Mohammadi, H.; & Aminai, M. M.; et al. Induction of resistance against powdery mildew by Beta aminobutyric acid in squash.Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality, 2016, 89. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R. K.; PAIVA, N. L.; LAMB, C. J.; DIXON, R. A.; et al. Accumulation of salicylic acid and PR-1 gene transcripts in relation to the systemic acquired resistance (SAR) response induced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato in Arabidopsis. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 1999, 55, 121-130. [CrossRef]

- George N. Agrios, Plant Pathology, 5th ed, ELSEVIER Academic Press, Amsterdam, 2005, pp. 448.

- van Loon, L. C.; Rep, M.; Pieterse, C. M.; et al. ignificance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol., 2006, 44, 135-162.

- Pajot, E., Le Corre, D. & Silué, D. Phytogard® and DL-β-amino Butyric Acid (BABA) Induce Resistance to Downy Mildew (Bremia Lactucae) in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L). European Journal of Plant Pathology 107, 861–869 (2001), 861, 866. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y., & Zhou, S. et al. (2021). Comparative analysis of powdery mildew resistant and susceptible cultivated cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) varieties to reveal the metabolic responses to Sphaerotheca fuliginea infection. BMC plant biology, 21(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kavroulakis, N.; Papadopoulou, K. K.; Ntougias, S.; Zervakis, G. I.; Ehaliotis, C.; et al. Cytological and other aspects of pathogenesis-related gene expression in tomato plants grown on a suppressive compost. Annals of botany, 2006, 98, 555-564. [CrossRef]

- Niderman, T.; Genetet, I.; Bruyere, T.; Gees, R.; Stintzi, A.; Legrand, M.; Mosinger, E.; et al. Pathogenesis-related PR-1 proteins are antifungal (isolation and characterization of three 14-kilodalton proteins of tomato and of a basic PR-1 of tobacco with inhibitory activity against Phytophthora infestans).Plant physiology, 1995, 108, 17-27. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. T. Expression, regulation and functional roles of β-1, 3-glucanase and chitinase in germinating tomato seeds. University of California, Davis. 2003.

- Rawat, S.; Ali, S.; Mittra, B.; & Grover, A.; et al. Expression analysis of chitinase upon challenge inoculation to Alternaria wounding and defense inducers in Brassica juncea. Biotechnology reports, 2017, 13, 72-79. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Y.; Jiang, W. J.; & Yu, H. J.; et al. The expression profiling of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family genes during fruit development, abiotic stress and hormonal treatments in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). International journal of molecular sciences, 2012, 13, 2481-2500. [CrossRef]

- Kawatra, Anubhuti & Dhankhar, Rakhi & Mohanty, Aparajita & Gulati, Pooja. Biomedical applications of microbial phenylalanine ammonia lyase: Current status and future prospects. Biochimie. 2020. 177. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Fan, A.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.’ Wang, X; et al. LecRK-V, an L-type lectin receptor kinase in Haynaldia villosa, plays positive role in resistance to wheat powdery mildew. Plant biotechnology journal, 2018, 16, 50-62.

- Wang, J.; Tao, F.; Tian, W.; Guo, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Hu, X. The wheat WRKY transcription factors TaWRKY49 and TaWRKY62 confer differential high-temperature seedling-plant resistance to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. PloS one, 2017,12, e0181963. [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, J.; Li, T.; Jia, M.; et al. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of WRKY12, A Pathogen Induced WRKY Transcription Factor from Akebia trifoliata.Genes,14, 1015.

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Qiao, Q.; Guo, X.; & Ma, Y.; et al. The WRKY transcription factor PlWRKY65 enhances the resistance of Paeonia lactiflora (herbaceous peony) to Alternaria tenuissima. orticulture Research, 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Phuntumart, Vipa & Marro, Pascal & Metraux, Jean-Pierre & Sticher, Liliane. A novel cucumber gene associated with systemic acquired resistance. Plant Science. 2006. 171. 555-564. [CrossRef]

| Genes | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| CsActin | F : 5′-TCG TGC TGG ATT CTG GTG-3′ |

| R : 5′-GGC AGT GGT GGT GAA CAT-3′ | |

| CsPAL | F : 5′-AAA CAC GTC GGA TAA ATA TGG CTT -3′ |

| R : 5′-CAT CCA TTC AGG CGT TCC AG -3′ | |

| CsPR3 | F : 5′-CAC TGC AAC CCT GAC AAC AAC G -3′ |

| R :5′-AAG TGG CCT GGA ATC CGA CTG -3′ | |

| CsPR1 | F : 5′-CTC AAG ACT TCG TCG GTG TCC A -3′ |

| R : CGC CAG AGT TCA CTA GCC TAC | |

| CsLOX1 | F : 5′-TCT TTG CTT CAG GGT ATC AC -3′ |

| R : 5′-GCA AAT TCT TCA TCA CTA CTC C -3′ | |

| LOX23 | F : 5′-TGC CTC CAA CAC CTT CTT CAA -3′ |

| R : 5′-CTT CCA TAT CAA ATC GCC ACA -3′ | |

| CsLecRK6.1 | F : 5′-CGA CCA CAA CGA AAT GTC ACA C -3′ |

| R : 5′- TTT CTT CCA CAC GCC ACT TCC -3′ | |

| CsWRKY20 | F : 5′-GAA ATA ACG TAC AGA GGG AAG C -3′ |

| R : 5′-CAG GTG CTG TTT GTT GGT TAT G -3′ | |

| Cupi4 | F : 5′-TCA CTG TGG TGT GTG CTC TC -3′ |

| R : - ACT CAA GCC ATT GCC TTC CA-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).