Submitted:

06 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Mealybugs

2.3. Biological Effect: Comparing ISR and SAR Efficiency and Application Methods

2.4. Biochemical Effect: Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL) Activity

2.5. Molecular Effect: Candidate Genes as Molecular Markers to Characterize SAR Priming

2.6. Protocols for Enzymatic and Gene Expression Measurements

- -

- Sample Preparation: The samples were rapidly washed under a stream of water, with the roots and the upper parts of the leaves removed. The remaining portions were then rinsed quickly twice—first with 70% ethanol and then with distilled water. For the analyses, the white part of the leaves and an equivalent-sized green portion contiguous to it were frozen in dry ice, ground into powder, freeze-dried, and finally stored in a freezer at -80 °C until protein or RNA extraction.

- -

- Protein extraction: Crude extracts (ce) were obtained from 50 mg of freeze-dried powder in cold 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), containing 40 mM PMSF as protease inhibitor (Sigma), and 62.5 mg.ml-[1] polyvinyl-polypyrrolidone under gentle stirring on ice for one hour. The ‘ce’ were then filtered first on Pall A/E glass-fiber filters (1µ), then on Whatman mini filters (0.45µ PS) to obtain a clear filtrate.

- -

- Enzymatic measurement (biochemical effect): The following procedures for enzymatic measurements were adapted from the protocols developed by the authors cited for microanalysis with reaction volumes of 300µL, each repeated twice. Absorbance was measured on 96-well quartz plates with a Powerwave HT (Biotek).. PAL: Cinnamic acid produced from L phenylalanine with 25µL of ce was measured at 290 nm [[37]]. The blank was modified using D Phenylalanine (ε = 9000 M-1 cm-1), PAL expressed in nKat.100µL-1 ‘ce’.

- -

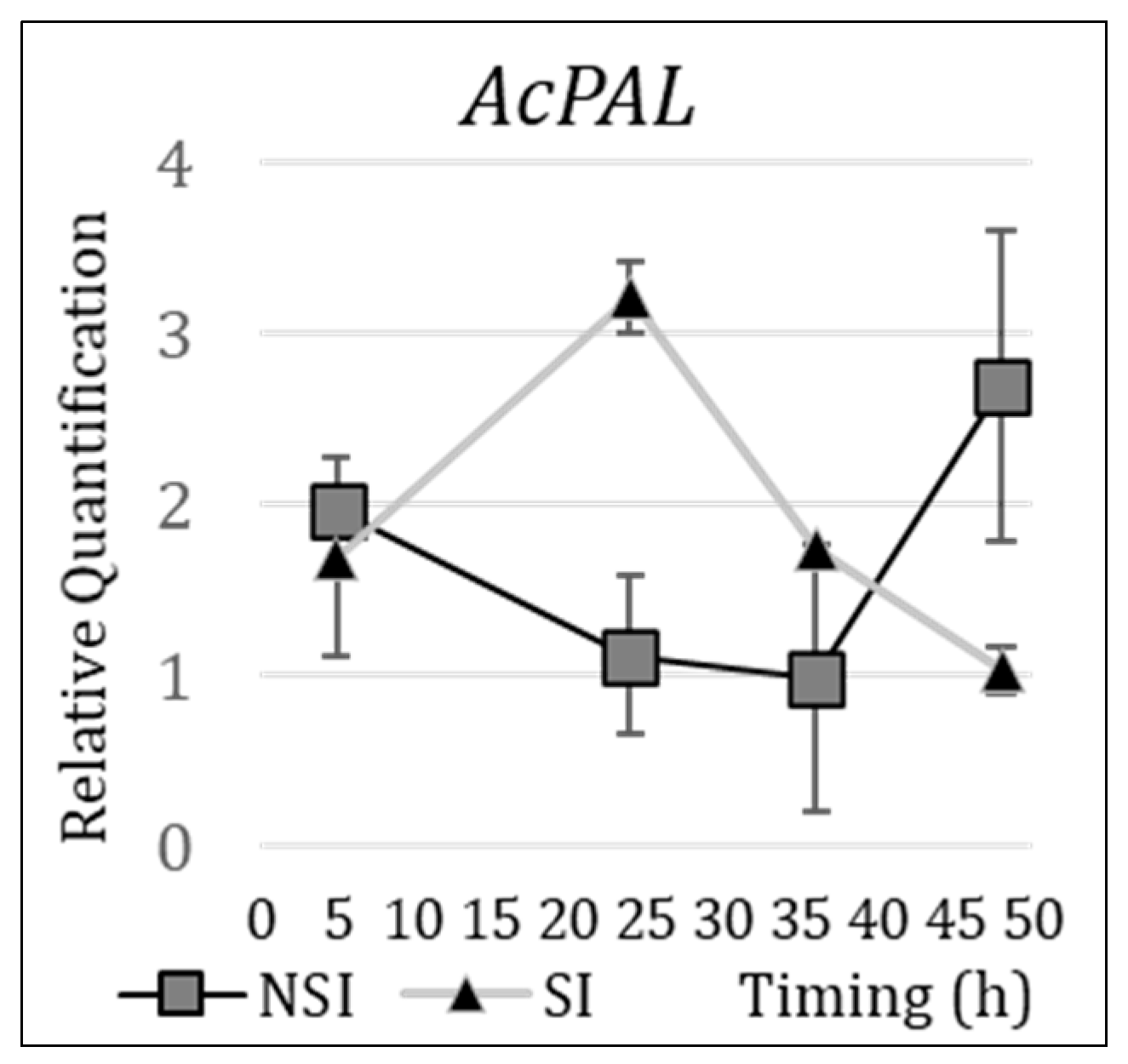

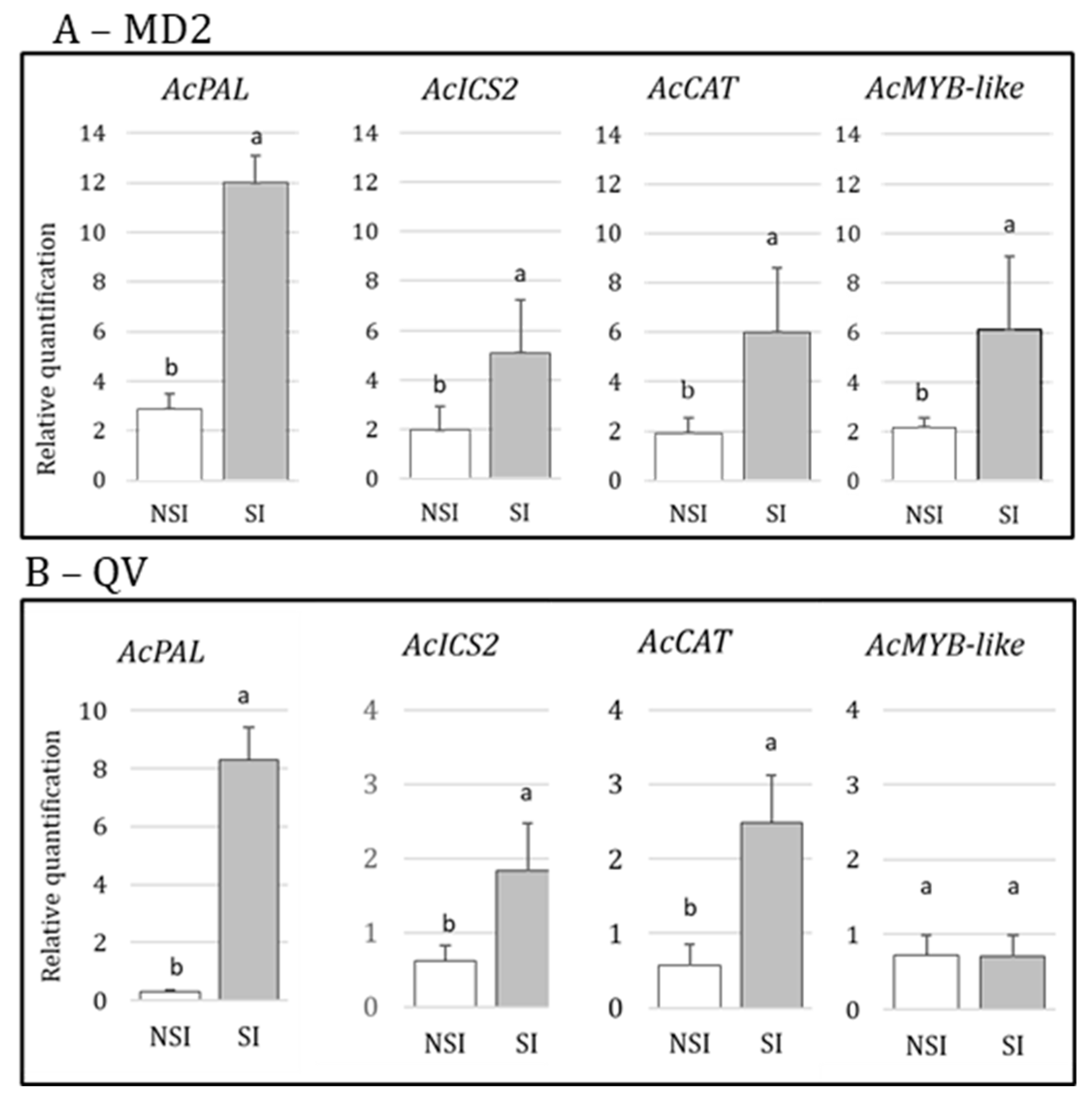

- Expression of defence genes (molecular effect): RNA was extracted on 25mg of lyophilized material using the RNeasy Plant mini kit (Qiagen), and the cDNA was obtained using the Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). RTqPCR with Fast SYBR Green Master Kit (Thermofisher) on Stepone Plus (Applied Biosystem) was done with 20 µL reaction volumes, and RTqPCR according to the recommendations included in the Kit. AcActine genes were used as reference genes. Primers were designed for Ananas comosus and differences in gene expressions between stimulated and unstimulated plants were evaluated for AcPAL, AcCAT, AcMYBlike, AcICS2. The optimal lag time after inoculation for evaluating these differences under our conditions was determined using AcPAL gene in MD2. The RNAs were extracted 5 h, 24 h, 36 h and 48 h after inoculation with mealybugs. Results are expressed as relative quantification by normalization against negative controls (Ctrl<0) that were neither stimulated nor inoculated, using AcActin-leaves as the housekeeping gene.

- -

- Data analyses: The biological effect data were analyzed using Kruskal and Wallis and Dunn tests. Data on biochemical effects, and data on molecular effects were analyzed by comparison of means with standard deviations (all stats performed with XLStat software).

3. Results

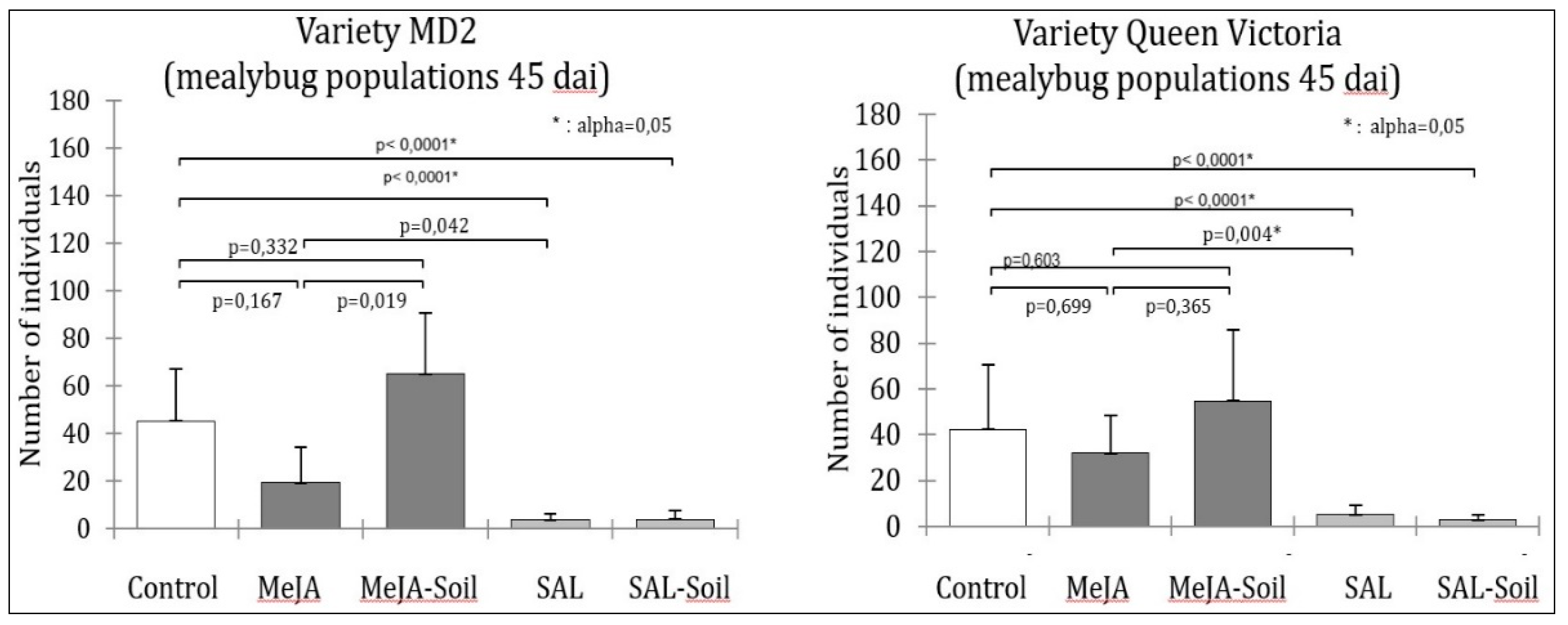

3.1. Biological Effect: Comparison of Stimulation with Salicylic Acid or Methyl Jasmonate

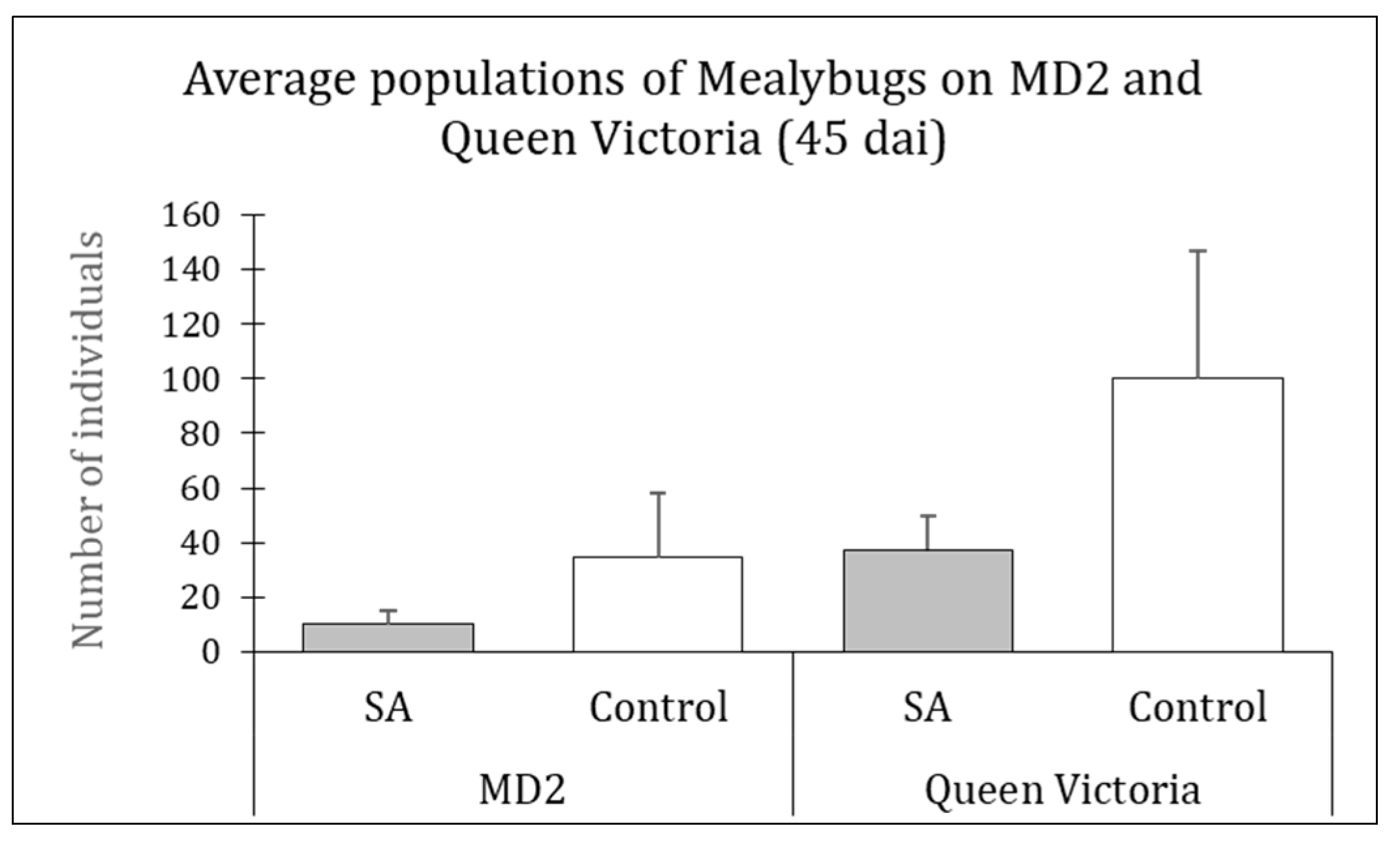

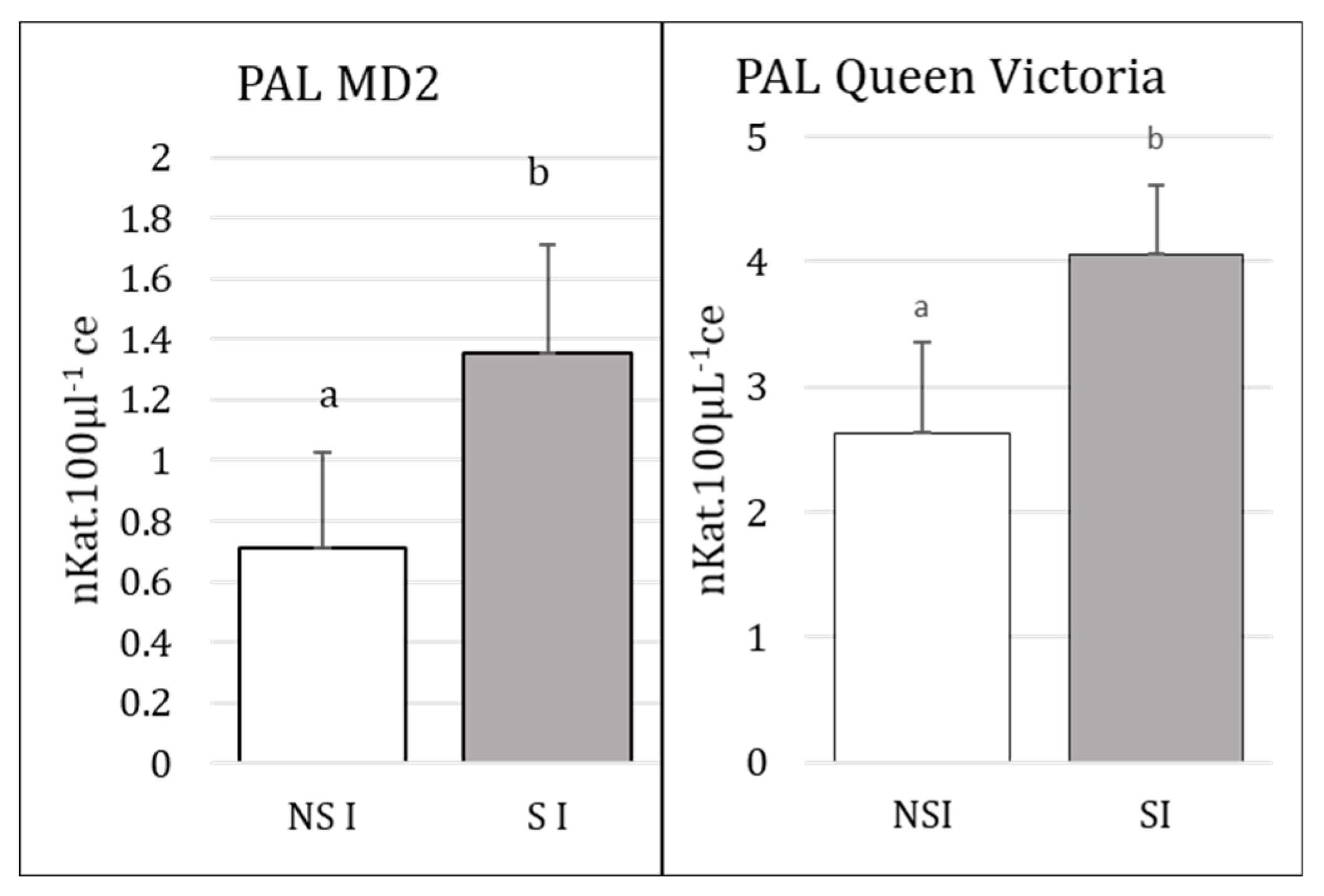

3.2. Biochemical Effects: Enzymatic Markers of SAR Defence

3.3. Molecular Effects

3.3.1. Timing Between Mealybug Inoculation and AcPAL Gene Expression in Stimulated vs. Unstimulated MD2 Plants

3.3.2. Molecular Markers of SAR Defence in MD2 and Queen Victoria

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Effect: Reducing Mealybug Multiplication

4.2. Biochemical and Molecular Effect of Salicylic Acid (SA) Treatment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, J.S.; Sether, D.M.; Metzer, M.J.; Pérez, E.; Gonsalves, A.; Karasev, A.V.; Nagai, C. Pineapple mealybug wilt associated virus and mealybug wilt of pineapple. Acta Hort. (ISHS) 2005, 666, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rodriguez, L.; Ramos-Gonzalez, P.L.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Zamora, V.; Peralta-Martin, A.M.; Pena, I.; Perez, J.M.; Ferriol, X. Geographic distribution of mealybug wilt disease of pineapple and genetic diversity of viruses infecting pineapple in Cuba. Crop Prot 2014, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, D.; Cassam, N.; Darnaudéry, M.; Dorey, E.; Hostachy, B.; Tullus, G.; Soler, A. Reunion Island: general survey of pineapple parasites with a focus on wilt disease and associated viruses; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS), Leuven, Belgium: 2024; pp. 67-74.

- Nurbel, T.; Soler, A.; Thuries, L.; Dorey, E.; Chabanne, A.; Tisserand, G.; Hoarau, I.; Darnaudery, M. Concevoir des systèmes de production d’ananas en agriculture biologique. Innovations Agronomiques 2021, 82, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, A.; Marie-Alphonsine, P.A.; Corbion, C.; Fernandes, P.; Portal Gonzalez, N.; Gonzalez, R.; Repellin, A.; Declerck, S.; Quénéhervé, P. A strategy towards bioprotection of tropical crops : Experiences and perspectives with ISR on pineapple and banana in Martinique. In Congrès: 6th meeting of IOBC-WPRS Working Group "Induced resistance in plants against insects and diseases": Induced resistance in plants against insects and diseases: leaping from success in the lab to success in the field, IOBC, Ed. Avignon, France, 2013.

- N’Guessan, L.; Chillet, M.; Chiroleu, F.; Soler, A. Ecologically Based Management of Pineapple Mealybug Wilt: Controlling Dysmicoccus brevipes Mealybug Populations with Salicylic Acid Analogs and Plant Extracts. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie-Alphonsine, P.-A.; Soler, A.; Gaude, J.-M.; Bérimée, M.; Qénéhervé, P. In Effects of cover crops on Rotylenchulus reniformis and Hanseniella sp. populations. IX International Pineapple Symposium, Havana, Cuba, 2019; D. P. Bartholomew, D. H. R., F. V. Duarte Souza, Ed. ISHS: Havana, Cuba, 2019; pp. 185-193.

- Pai Li; Lu, Y.-J.; Chen, H.; Day, B. The Lifecycle of the Plant Immune System. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2020, 1–29.

- Boller, T.; Felix, G. A Renaissance of Elicitors: Perception of Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns and Danger Signals by Pattern-Recognition Receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009, 60, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, B.C.; Beattie, G.A. An overview of plant defenses against pathogens and herbivores. The Plant Health Instructor 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithöfer, A.; Boland, W. Recognition of herbivory-associated molecular patterns. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, C. Plant pattern-recognition receptors. Trends Immunol 2014, 35, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klessig, D.F.; Choi, H.W.; Dempsey, D.M.A. Systemic acquired resistance and salicylic acid: past, present, and future. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.; Chen, Y.C.; Sattely, E.; Mudgett, M.B. Conservation of N-hydroxy-pipecolic acid-mediated systemic acquired resistance in crop plants. bioRxiv, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, J.; Kitazawa, H.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Takahashi, H. Receptors and Signaling Pathways for Recognition of Bacteria in Livestock and Crops: Prospects for Beneficial Microbes in Healthy Growth Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2223–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Medina, A.; Flors, V.; Heil, M.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Pozo, M.J.; Ton, J.; van Dam, N.M.; Conrath, U. Recognizing Plant Defense Priming. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrath, U. Molecular aspects of defense priming. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G.J.; Langenbach, C.J.; Jaskiewicz, M.R. Priming for enhanced defense. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015, 53, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehari, Z.H.; Elad, Y.; Rav-David, D.; Graber, E.R.; Harel, Y.M. Induced systemic resistance in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) against Botrytis cinerea by biochar amendment involves jasmonic acid signaling. Plant Soil 2015, 395, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; Ganguly, N.; Chakraborty, B.; Adhya, T.K. Pathogenesis related proteins: milestones in five decades of research. Indian Phytopathology, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, S.; Williams, S.J.; Outram, M.; Kobe, B.; Solomon, P.S. Emerging Insights into the Functions of Pathogenesis-Related Protein 1. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrant, W.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2004, 42, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; Fan, W.; Dong, X. Inducers of plant systemic acquired resistance regulate NPR1 function through redox changes. Cell 2003, 113, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoel, S.H.; Koornneef, A.; Claessens, S.M.C.; Korzelius, J.P.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Mueller, M.J.; Buchala, A.J.; Métraux, J.-P.; Brown, R.; Kazan, K.; et al. NPR1 Modulates Cross-Talk between Salicylate- and Jasmonate-Dependent Defense Pathways through a Novel Function in the Cytosol. The Plant Cell Online 2003, 15, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, J.; Dong, X. Posttranslational modifications of NPR1: a single protein playing multiple roles in plant immunity and physiology. PLoS Path. 2016, 12, e1005707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younus Wani, M.; Mehraj, S.; Rathe, R.A.; Rani, S.; Hajam, O.A.; A, G.N.; Mir, M.R.; Baqual, M.F.; S, K.A. SAR:A novel strategy for plant protection with reference to mulberry. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2018, 6, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Monci, F.; García-Andrés, S.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; Fernández-Muñoz, R.; Díaz-Pendón, J.A.; Moriones, E. Use of Systemic Acquired Resistance and Whitefly Optical Barriers to Reduce Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Disease Damage to Tomato Crops. Plant disease 2019, 103, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Dou, K.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Enhanced biocontrol activity of cellulase from Trichoderma harzianum against Fusarium graminearum through activation of defense-related genes in maize. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 103, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, S.; Thompson, G.A.; Powell, G. Application of DL-[beta]-aminobutyric acid (BABA) as a root drench to legumes inhibits the growth and reproduction of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2005, 95, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, A.; Marie-Alphonsine, P.A.; Quénéhervé, P.; Prin, Y.; Sanguin, H.; Tisseyre, P.; Daumur, R.; Pochat, C.; Dorey, E.; Gonzalez Rodriguez, R.; et al. Field management of Rotylenchulus reniformis on pineapple combining crop rotation, chemical-mediated induced resistance and endophytic bacterial inoculation. Crop Protection 2021, 141, 8p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, P.; Anjana, R.; Soumya, K. Insect Pests of pineapple and management. In Insect Pests Management of FRUIT CROPS Ajay Kumar Pandey, P.M., Ed. BIOTECH BOOKS: India, 2016; pp. 471-492.

- Tripathi, D.; Raikhy, G.; Kumar, D. Chemical elicitors of systemic acquired resistance—Salicylic acid and its functional analogs. Current Plant Biology 2019, 17, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, A.; Marie-Alphonsine, P.-A.; Corbion, C.; Quénéhervé, P. Differential response of two pineapple cultivars ( Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) to SAR and ISR inducers against the nematode Rotylenchulus reniformis. Crop protection 2013, 54, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, L.A.; Joyce, D.C. Elicitors of induced disease resistance in postharvest horticultural crops: a brief review. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2004, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elicitra. Guide méthodologique d'évaluation de l'efficacité des Stimulateurs des Defenses des Plantes. Elicitra (Colloque Elicitra 13-14 juin): Avignon 2013; p p35.

- Py, C.; Lacoeuilhe, J.J.; Teisson, C. The pineapple: Cultivation and uses; Editions G.-P. Maisonneuve: Paris, 1987; p. 568. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Dahler, J.; Underhill, S.; Wills, R. Enzymes associated with blackheart development in pineapple fruit. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.A.; Rothballer, M.; Chowdhury, S.P.; Nussbaumer, T.; Gutjahr, C.; Falter-Braun, P. Systems biology of plant microbiome interactions. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-L.; Paull, R.E. Genetic Transformation of Pineapple. In Genetics and Genomics of Pineapple, Springer: 2018; pp. 69-86.

- Tanpure, R.S.; Kondhare, K.R.; Venkatesh, V.; Gupta, V.S.; Joshi, R.S.; Giri, A.P. Non-host Armor Against Insect: Characterization and Application of Capsicum annuum Protease Inhibitors in Developing Insect Tolerant Plants. In Genetically Modified Crops: Current Status, Prospects and Challenges Volume 2, Kavi Kishor, P.B., Rajam, M.V., Pullaiah, T., Eds. Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2021; 10.1007/978-981-15-5932-7_4pp. 85-110.

- Raimbault, A.-K.; Zuily-Fodil, Y.; Soler, A.; Mora, P.; Cruz de Carvalho, M.H. The expression patterns of bromelain and AcCYS1 correlate with blackheart resistance in pineapple fruits submitted to postharvest chilling stress. Journal of Plant Physiology 2013, 170, 1442–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson J, N.; Urwin P, E.; Clarke M, C.; McPherson, M., J. Image Analysis of the Growth of Globodera pallida and Meloidogyne incognita on Transgenic Tomato Roots Expressing Cystatins. Journal of Nematology 1996, 28, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Raimbault, A.K.; Zuily-Fodil, Y.; Soler, A.; Mora, P.; Cruz de Carvalho, M.H. Postharvest chilling treatment induces distinct expression in fruit bromelain and cystatin in two pineapple (Ananas comosus (L) Merr.) varieties differing in their susceptibility to blackheart physiopathy, PhD. Paris EST, 2012.

- Soneji, J.R.; Nageswara Rao, M. Genetic engineering of pineapple. Transgenic Plant Journal 2009, 3, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barral, B.; Chillet, M.; Léchaudel, M.; Lugan, R.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Coumaroyl-isocitric and caffeoyl-isocitric acids as markers of pineapple fruitlet core rot disease. Fruits 2019, 74, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Q.; Mou, Z. Redox signaling and oxidative stress in systemic acquired resistance. J Exp Bot, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes. | Accession n° | Front (F) and reverse (R) primers |

|

AcPAL |

Aco010091.1 (Phytozomev3) |

F-AGGTGTTTGACGCCATTTG R-CACCGTTCCAGTCCTTCAA |

|

AcMYB like |

Aco011681.1 (Phytozomev3) |

F-GTTCAAGCAAGTCAAGAACC R-GAGTCCATTGATTCGCATTG |

|

AcICS2 |

XM_020232036 (NCBI) |

F-AGTGAATTTGCTGTCGGTAT R-GCAATCTTGTGAACTGGGA |

| AcCAT | XM_020259660.1 (NCBI) |

F-CAGCTATTGTGGTGCCTGGA R- CTTCCAGAGAGAACGAGGG |

| House keeping Gene | ||

|

AcActin like-fe Housekeeping gene |

XM_020238587.1 (NCBI) |

F-CCTACGTTGCCCTCGACTAC R-GGAAGAGCACTTCAGGACACA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).