1. Introduction

Wind power, as a clean and renewable energy option, holds crucial significance for alleviating climate change and boosting global initiatives aimed at achieving carbon neutrality [

1]. Over the past few years, the fast-paced growth of wind power programs has led to a notable rise in the proportion of renewable energy in the world’s overall energy structure [

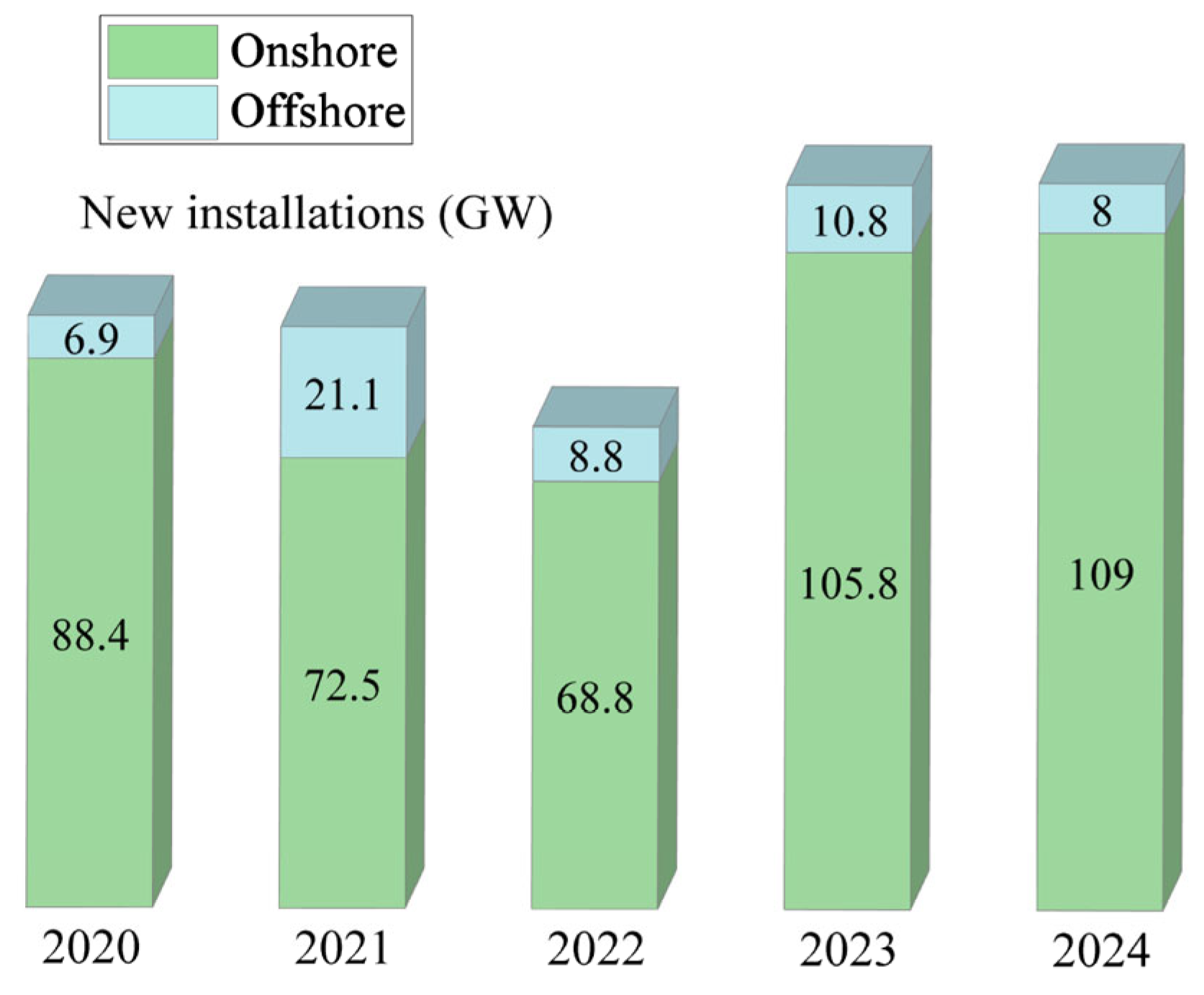

2]. According to the Global Wind Energy Council’s Global Wind Report 2025 [

3], newly installed global wind capacity reached a record 117 GW in 2024, while cumulative grid-connected offshore wind capacity reached 83.2 GW (

Figure 1). The offshore wind industry is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 21% over the next decade (2025–2034), demonstrating strong long-term potential.

Compared with onshore wind power, offshore wind power offers higher power generation efficiency owing to greater wind speed and stability. However, the expansion of offshore wind capacity faces significant challenges, including delays in grid infrastructure development and the inherent volatility and intermittency of wind power [

4], both of which threaten grid stability, a persistent issue for the sector.

Hydrogen, as an emerging energy carrier, provides distinct advantages given its high energy density and ease of storage. The combination of offshore wind power and water electrolysis technology for hydrogen generation offers three key advantages [

5,

6]:

- (1)

Wind energy, characterized as an “immediate” energy source, is convertible into hydrogen. When stored long-term as high-pressure gas or cryogenic liquid, this conversion incurs only slight energy loss.

- (2)

The process of hydrogen production can alleviate grid instability brought about by wind variability. Functioning as a “peak-shaving and valley-filling” asset, it also helps decrease the curtailment of wind energy [

7].

- (3)

Hydrogen transportation is feasible via ships or repurposed oil and gas pipelines. This not only lessens the need for expensive submarine cables [

8] but also facilitates the development of large-scale deep-sea wind initiatives.

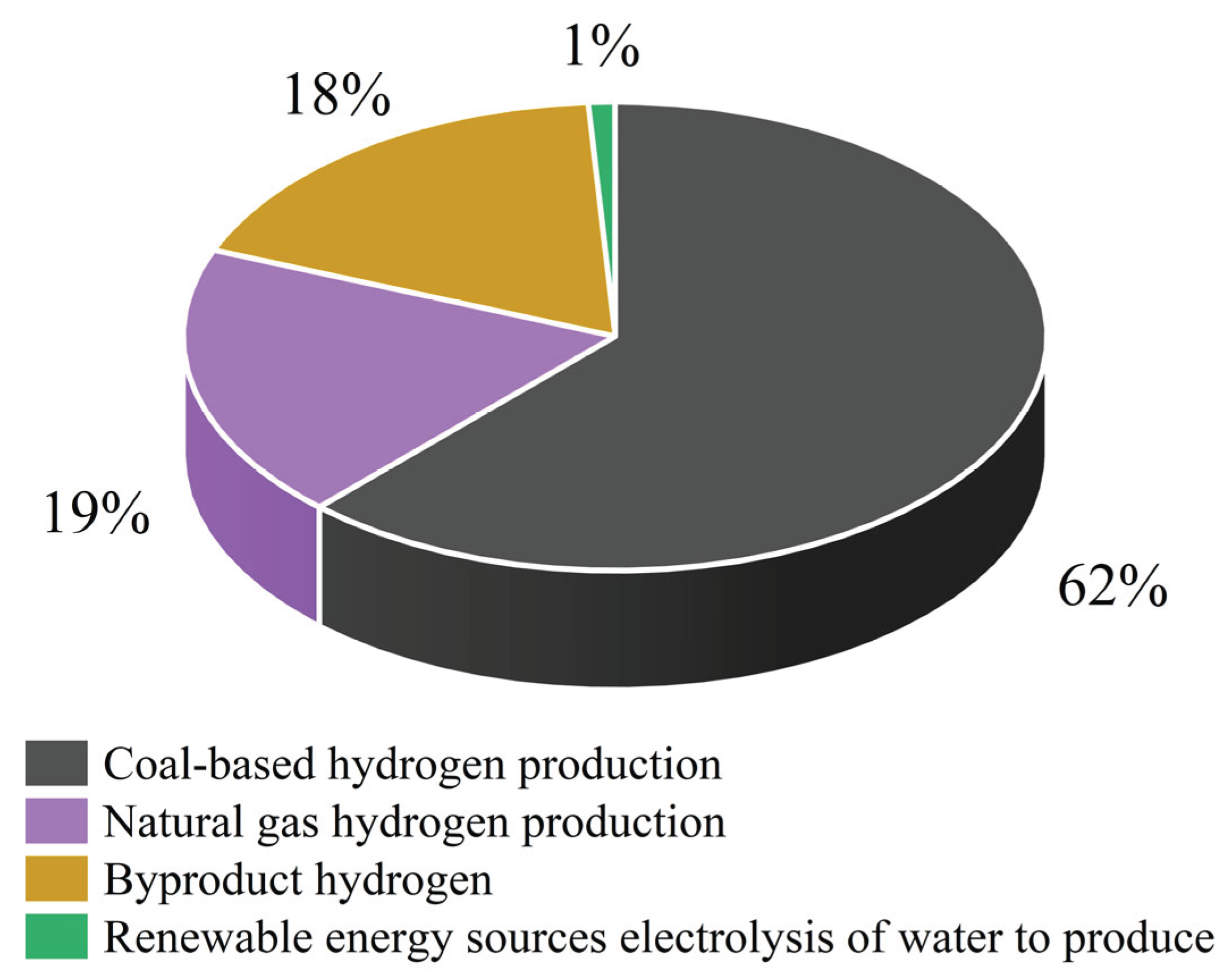

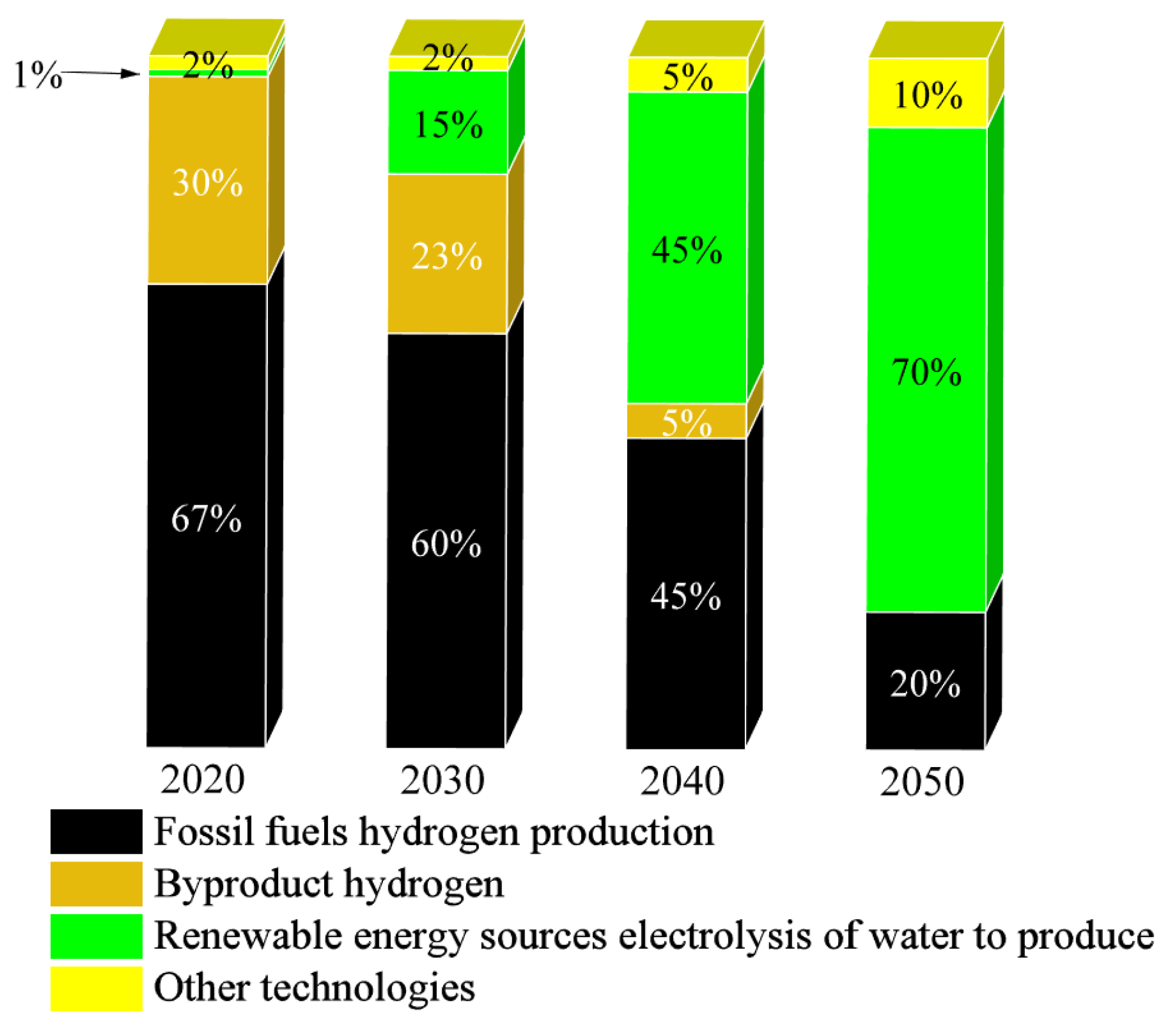

By the end of 2024, global hydrogen production had reached approximately 150 million tons per year, a 2.9% year-on-year increase. Currently, about 62% of hydrogen is produced as “grey hydrogen” from fossil fuels, 19% from natural gas reforming, 18% from industrial by-products, and only 1% as “green hydrogen” derived from renewable energy [

9] (

Figure 2). With the global push for carbon neutrality, green hydrogen is projected to account for 15% of total production by 2030 and over 70% by 2050 [

10] (

Figure 3).

This paper examines offshore wind-to-hydrogen production, reviewing three technical routes and their defining characteristics through global case studies. In this study, we identify key challenges, including the immaturity of electrolysis technologies, high production costs, and bottlenecks in storage and transport, and propose future development pathways to support innovation and large-scale application.

2. Engineering Cases of Offshore Wind-to-Hydrogen Production

As indicated in the

China Hydrogen Energy Development Report (2025) [

11], by the close of 2024, the global annual production of renewable hydrogen through electrolysis surpassed 250,000 tons. Notably, in 2024 alone, the increment reached 70,000 tons, marking a 42% year-on-year growth. Furthermore, the International Hydrogen Energy Commission’s

Global Green Hydrogen Energy Development Report (2025) [

12] indicates that global electrolyzer capacity had surpassed 30 GW by mid-2025, driven mainly by large-scale offshore projects in China, the United States, and Europe. Current leading offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1 presents ten representative global offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects, which can be divided into three technical approaches: hydrogen production via offshore distributed wind power, hydrogen production via offshore centralized distributed wind power, and hydrogen production from offshore wind power transported to onshore locations. Among these pathways, three projects adopt the first route, three the second, and four the third, indicating a relatively balanced distribution across the different approaches.

In terms of installed capacity, projects under development are significantly larger in scale compared with those already in operation. For example, the PosHYdon project in the world’s very first offshore wind-to-hydrogen initiative, located in the Netherlands, has an installed capacity of just 1 MW. In contrast, another Dutch project, NortH2, which is set to be rolled out by 2030, is projected to have an installed capacity of 4000 MW. This shift reflects a trend in the industry toward large-scale deployment and the establishment of base-type projects.

When viewed from the lens of water electrolysis methodologies, half of the projects documented in

Table 1 utilize ALK electrolysis technology, 40% rely on PEM technology, and a mere 10% adopt SOEC technology for high-temperature electrolysis processes. At present, ALK technology stands out as the most technically mature and economically viable option. However, its ability to adjust to fluctuations in wind power is constrained, primarily due to its relatively high minimum operating load range (20%–100%). As a result, ALK technology is more frequently deployed in stable operational settings—such as onshore hydrogen production scenarios—though it also holds potential for expansion to offshore applications in the short term. PEM electrolyzers, by contrast, have a minimum operating load of just 5%–10% and can start and stop quickly, making them well-suited to the intermittency of renewable energy sources [

17]. The outlet pressure of PEM electrolyzers is also compatible with pipeline transport; however, high costs remain a major barrier. Over the long term, PEM is expected to become the preferred technology for offshore wind-to-hydrogen production. At present, only the Deep Purple project in Norway is exploring the SOEC technology. Although SOEC offers the potential for high operating temperatures (500 °C–1000 °C), stringent material constraints currently limit large-scale deployment [

18].

Europe leads in multi-technology exploration, with a focus on PEM and deep-sea centralized projects. In contrast, China relies mainly on ALK technology and onshore hydrogen production, offering rapid scaling but with less technological diversity. As PEM costs decrease and offshore wind projects extend into deeper waters, centralized PEM-based hydrogen production is likely to become mainstream. For China, accelerating PEM localization will be critical to enhancing adaptability to offshore wind fluctuations.

3. Technical Routes for Offshore Wind-to-Hydrogen Production

Case analysis reveals that all three technical routes are being actively explored, with applications distributed relatively evenly. This balance indicates that each pathway has distinct advantages and suitable scenarios at the current stage while also highlighting that the industry has not yet converged on a single dominant approach. Instead, the industry remains in a state of parallel exploration across multiple paths.

As outlined above, offshore wind-to-hydrogen production is mainly divided into three categories: offshore distributed wind power hydrogen production, offshore centralized wind power hydrogen production, and offshore wind power for onshore hydrogen production [

19].

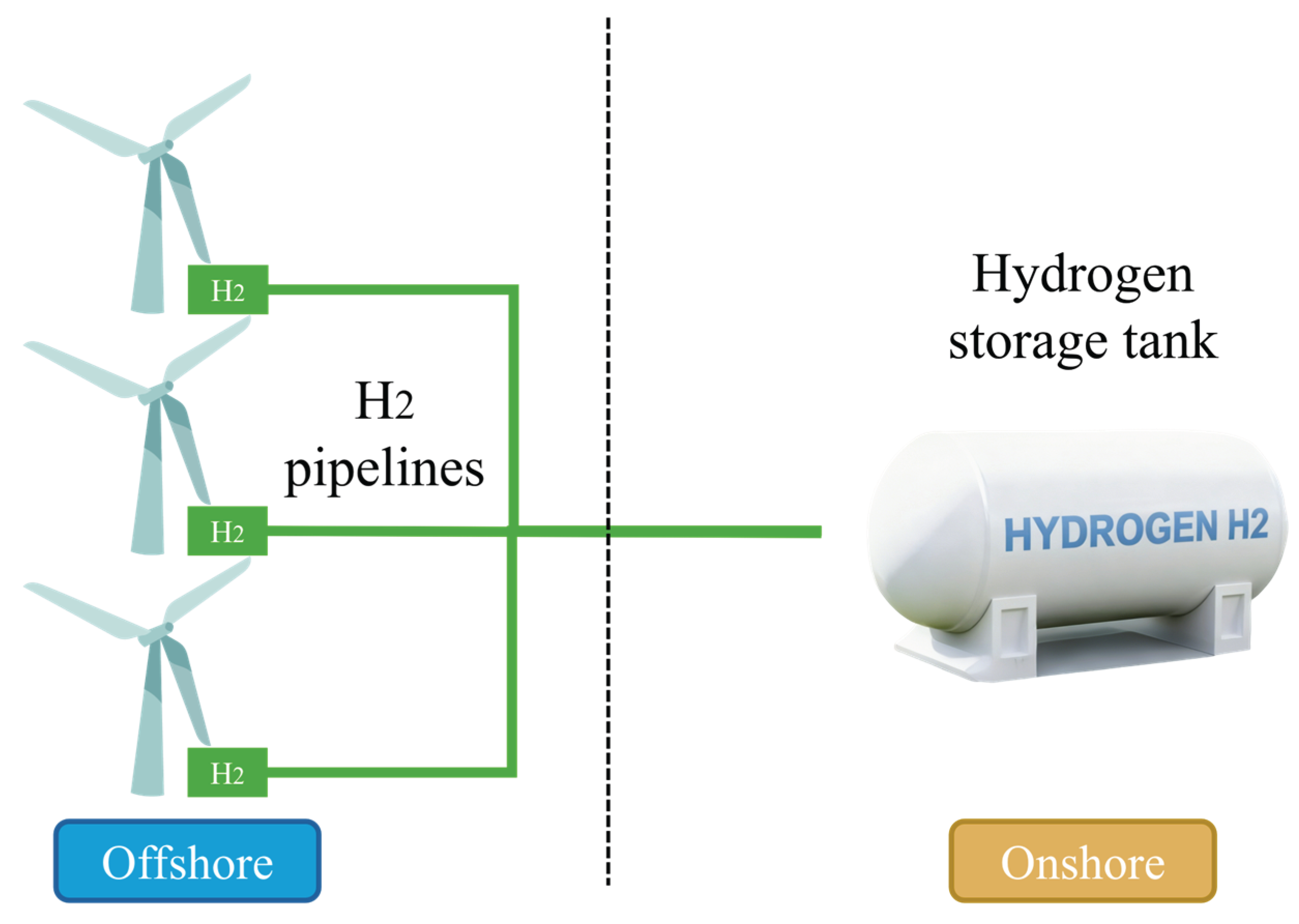

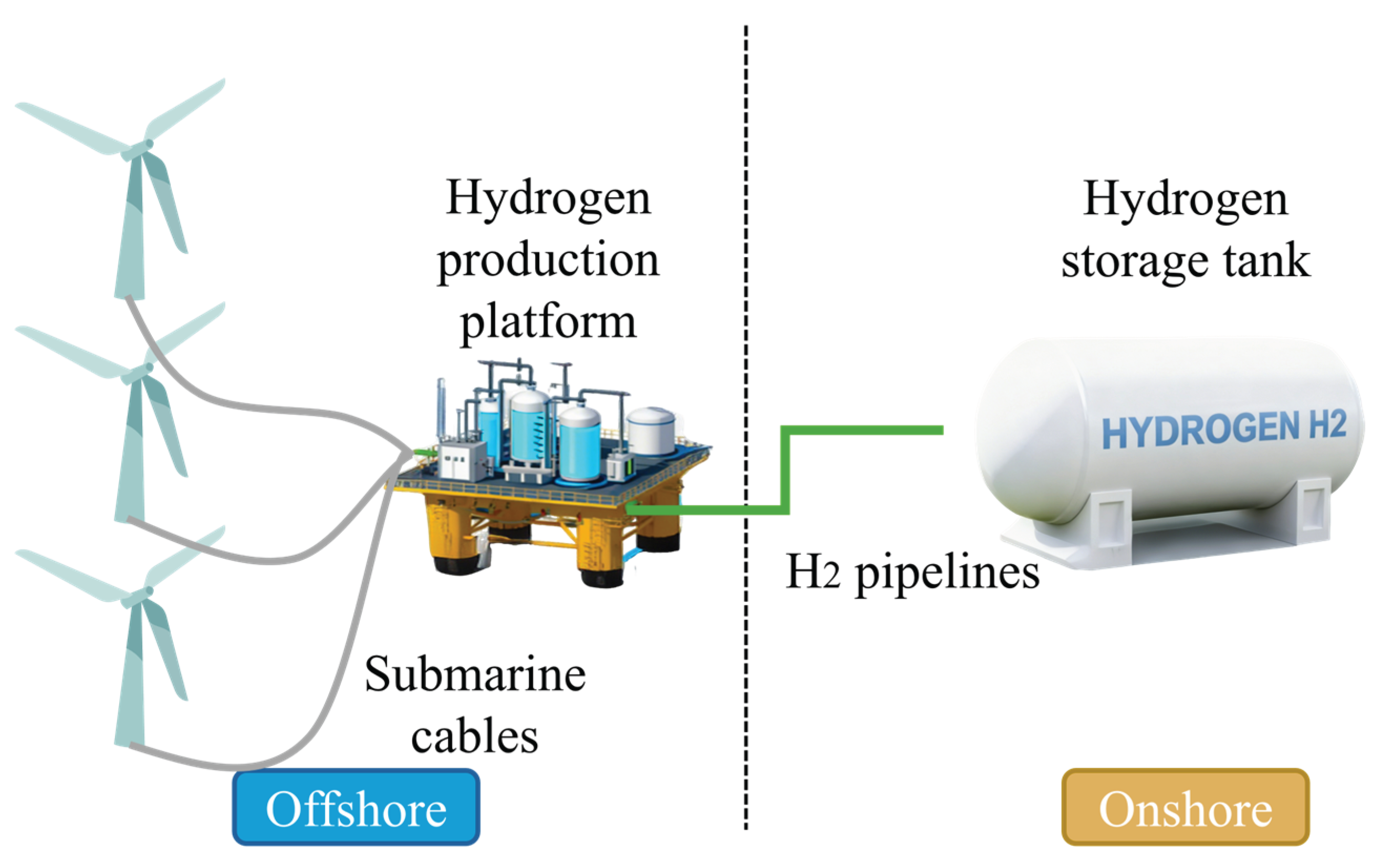

The first approach, the offshore distributed wind-to-hydrogen system, is illustrated in

Figure 4. In this configuration, each wind turbine’s floating platform is equipped with dedicated electrolysis units. After wind turbines capture offshore wind energy and convert it into electrical energy, instead of transmitting it through long-distance grid connection, the electrical energy is directly input into the electrolysis device on the platform. The produced hydrogen is then transported to onshore storage via hydrogen pipelines [

20]. The advantage of this technical route is that each electrolyzer and wind turbine are paired and independent of each other. The unitized design ensures that when any electrolyzer cannot operate due to a malfunction of the wind turbine or when the power generation is lower than the minimum operating level of the electrolyzer, other electrolyzers and wind turbines can still produce hydrogen, which greatly improves the stability and fault tolerance of hydrogen production. However, this operating mode also faces two core issues. Firstly, the offshore wind power platform itself is in a dynamic operating state. Wind turbines generate continuous vibrations when capturing wind energy, while electrolysis devices (especially proton exchange membrane electrolyzers, which have high requirements for operational stability) are extremely sensitive to vibrations and tilt angles [

21]. Long-term vibrations may cause loosening of the internal electrode structure of the electrolyzer and electrolyte leakage, significantly reducing the service life of the equipment [

22]. Secondly, the costs of laying and maintaining hydrogen pipelines remain high. Complex hydrogen pipelines also result in high laying costs, and in the event of a leak, not only are the repair costs high, but there may also be a risk of marine environmental pollution, further increasing maintenance costs. The economic viability of this hydrogen production mode needs further verification and optimization.

Next is the offshore centralized wind-to-hydrogen system. The hydrogen production process is completed on independent floating platforms or dedicated hydrogen production ships, with a typical system configuration shown in

Figure 5. In this technical architecture, the electrical energy generated by each wind turbine in the offshore wind farm is first collected and transmitted to the offshore substation through the collector system. The AC power is rectified into DC power by the converter equipment in the substation, and then the low-loss long-distance transmission of electrical energy is realized by means of large-capacity high-voltage direct current (HVDC) cables [

23,

24], which is finally supplied to the water electrolysis hydrogen production device carried by the floating hydrogen production platform. The produced high-purity hydrogen is then transported to onshore storage, processing or application terminals through dedicated hydrogen pipelines or ships. This system scheme has significant technical and economic advantages: First, compared with the distributed offshore wind power-to-hydrogen system, it can be deployed in far-reaching sea areas, making full use of the characteristics of richer wind energy resources and more stable wind directions in offshore areas [

25]; Second, the centralized hydrogen production layout eliminates the cost of supporting booster equipment for each turbine in the distributed system, simplifies the topology of the offshore power system, and reduces the difficulty of equipment maintenance [

26]; Third, it has good resource integration. It can rely on the infrastructure of existing offshore oil and gas platforms for transformation and upgrading, converting them into hydrogen production platforms, effectively reusing the platform’s pile foundations, power transmission channels, personnel operation and maintenance facilities, etc., which significantly reduces the initial investment and construction cycle of the project [

27]. This scheme enables large-scale wind-to-hydrogen production in far-offshore areas and represents a promising direction for the future development of the offshore hydrogen production industry.

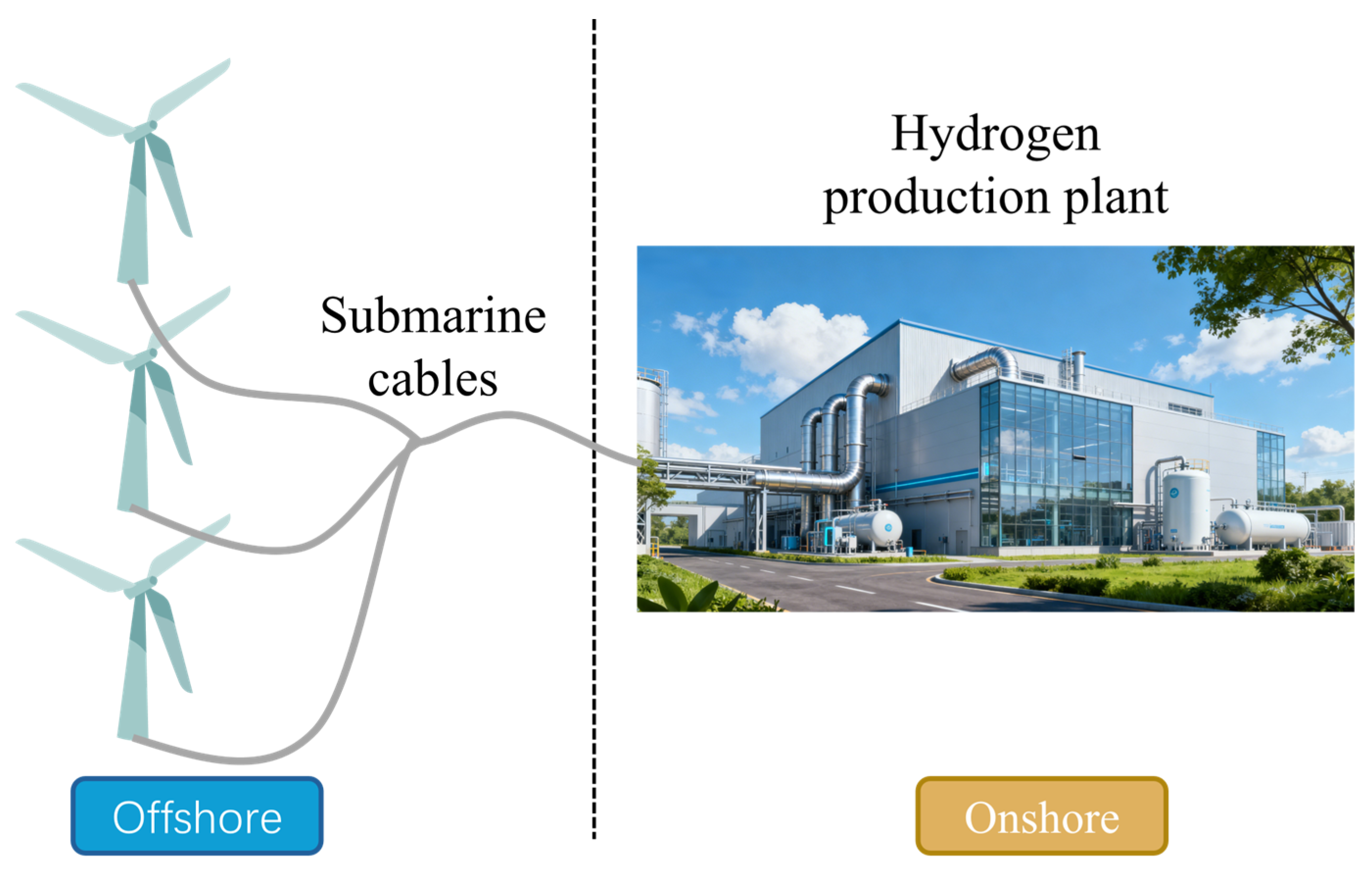

The third route is the onshore hydrogen production system powered by offshore wind power (

Figure 6). The electricity generated by offshore wind turbines is first transmitted via submarine AC cables to an offshore substation. After voltage boosting and conversion to high-voltage direct current (HVDC), the electricity is delivered through high-voltage cables to onshore electrolyzers. This system demonstrates significant technical advantages: First, all core hydrogen production equipment is deployed on land. Compared with offshore hydrogen production models, this can greatly reduce the difficulty of offshore hoisting during equipment installation and make daily maintenance more convenient. Second, the layout of onshore sites is not restricted by marine space resources, making it easy to flexibly expand equipment capacity according to the scale of hydrogen production, and it can also achieve coordinated layout with existing industrial parks or hydrogen energy infrastructure [

28]. Third, it absorbs surplus wind power to produce hydrogen during the low-load period of the power grid, and realizes energy feedback through hydrogen fuel cell power generation or hydrogen chemical utilization during peak periods, forming an effective power grid peak regulation buffer mechanism [

29]. However, the economic efficiency of the system is significantly affected by the offshore distance. As the offshore distance of the offshore wind farm increases, the material cost and laying cost of submarine cables will increase linearly. At the same time, the construction scale of offshore booster stations needs to be expanded accordingly to meet the insulation and heat dissipation requirements of long-distance power transmission. In addition, during the transmission of electricity through submarine cables, the loss rate increases with the increase of transmission distance and current intensity. The superposition of these two factors causes the cost of hydrogen production per kilowatt-hour of the system to rise, weakening its market competitiveness.

4. Bottlenecks in Offshore Wind-to-Hydrogen Production

4.1. Need for Breakthroughs in Water Electrolysis and Adaptation Technologies

Wind power generation exhibits significant characteristics of intermittency, volatility, and randomness. Its intraday power output fluctuates drastically, with variations ranging from 0% to 100% under extreme conditions [

30,

31]. Moreover, the safe and efficient operation of hydrogen production systems is highly dependent on a stable and continuous power supply. Currently, ALK, the most cost-effective technology, has notable limitations. The load adjustment range of alkaline electrolyzers is limited to 20%–100%, and their response to rapid start-stop or variable loads is relatively poor; thus, ALK is not well adapted to the unstable operating conditions of offshore wind power [

32]. PEM hydrogen production technology has become the mainstream pathway in the international hydrogen industry, owing to its fast response characteristics and high efficiency advantages. However, PEM electrolyzers rely on precious-metal catalysts such as iridium, which results in high system costs [

33]. In addition, when deployed in offshore environments, they exhibit relatively high failure rates: electrodes and mechanical components are extremely vulnerable to seawater corrosion, which in turn leads to a short service life. These factors currently represent major barriers restricting the large-scale industrial application of PEM technology in offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects.

4.2. High Costs Across the Entire Project Life Cycle

In the cost structure system of hydrogen production via water electrolysis, electricity costs occupy a dominant position. Estimates from China New Energy Network suggest that electricity typically represents 40%–60% of total costs [

34]. Under current technical conditions, using alkaline electrolyzers to produce 1 cubic meter of hydrogen requires a comprehensive system power consumption of approximately 4.5–5.5 kWh. Given the existence of phased bottlenecks in hydrogen production processes, significant reductions in this energy demand are unlikely in the short term. Therefore, the electricity price level has become a core factor determining the cost of power consumption. Moreover, offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects require a continuous and substantial supply of freshwater for electrolysis. Conventional seawater desalination technologies, however, present major challenges in terms of energy intensity. Their operation remains heavily dependent on fossil fuels, resulting in high costs for desalinated water, typically in the range of 5–10 US dollars per ton.

Submarine cables serve as the main channels for power transmission in offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects and account for a considerable proportion of the total project investment. HVDC cables are even more expensive owing to their stringent requirements for materials and manufacturing processes. In terms of materials, high-purity copper is required as the conductor to ensure low resistance and efficient power transmission. In terms of manufacturing processes, HVDC cable production involves multiple complex procedures, each requiring high-precision equipment and strict quality control. These factors collectively result in the unit price of HVDC cables reaching 8–13 million yuan per km.

As offshore wind power resources in coastal areas are gradually developed and saturated, wind power development is shifting toward far-offshore areas. However, these environments bring substantial technical and economic challenges that lead to a significant increase in project costs [

35]. For projects located more than 30 km offshore, construction difficulty increases exponentially. Advanced and more powerful offshore construction platforms are needed to withstand harsh sea conditions, significantly increasing equipment rental costs. In addition, the long distance from shore extends the time and expenses associated with transporting construction materials, further pushing up construction costs.

4.3. Lag in Storage and Transportation Technologies and Facilities

Owing to its small molecular size and active chemical properties, hydrogen exhibits high permeability and induces hydrogen embrittlement, which places extremely high demands on the selection and performance of pipeline materials. Although large-scale hydrogen pipeline transportation has entered the demonstration stage, the problem of material performance degradation caused by hydrogen embrittlement has not yet been effectively resolved, and protective technologies are still in the exploration stage [

36]. Hydrogen storage technologies also face significant challenges. Liquid hydrogen storage requires maintaining an extremely low temperature environment of −253 °C, resulting in high energy consumption costs and poor economic efficiency [

37]. Solid-state hydrogen storage materials offer the advantage of high volumetric density, but large-scale commercialization has not yet been achieved. These technical bottlenecks in both storage and transportation continue to hinder the industrial development of offshore wind-to-hydrogen projects [

38].

5. Outlook for Hydrogen Production from Offshore Wind Power

Offshore wind-to-hydrogen production, as an important pathway for reducing wind power curtailment and promoting energy system transformation, holds broad prospects for future development. To address the bottlenecks described above, progress will be required in several areas to promote the scaling up and commercialization of this technology.

5.1. Electrolyzer Technology Upgrade

For ALK electrolyzers, research should prioritize the development of wide-load adjustment technologies capable of adapting to wind power volatility. Key goals include overcoming the current limitation of low-load operation below 20%, enhancing rapid start-stop performance, and improving variable load response speed by optimizing electrode materials and diaphragm performance, thereby reducing the difficulty of adapting to fluctuating wind power conditions. For PEM electrolyzers, efforts should focus on reducing dependence on precious-metal catalysts. This reduction can be accomplished by lowering iridium loading through catalyst structure design and carrier modification. A collaborative team from the German Aerospace Center and the Spanish Institute of Materials Science recently developed a novel double-perovskite catalyst, Sr

2CaIrO

6, which successfully reduced anode iridium loading to 0.2mg/cm

2 [

39]. In addition, research should be strengthened on seawater corrosion resistance, with emphasis on developing electrode and equipment materials resistant to salt spray and vibration, thereby extending the service life of PEM electrolyzers in marine environments. For SOEC technology, the focus should be on improving the performance of high-temperature materials. This improvement includes developing electrolyte and electrode materials that are resistant to high temperatures and performance attenuation, reducing dependence on extreme working conditions, and accelerating progress from laboratory-scale research to industrial demonstration projects.

5.2. Optimizing Energy Utilization Efficiency

Optimizing renewable energy storage systems holds unique strategic importance [

40]. Advanced energy storage systems and energy management technologies play a critical role in mitigating the inherent instability of wind power. Optimal allocation of operating power across different stages of the wind-to-hydrogen process allows wind energy to be converted into hydrogen during off-peak hours and utilized during peak demand periods. This time-shifted conversion enables more effective management of energy production and storage across different time scales, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, and promotes the widespread integration of renewable energy sources [

41].

To further improve system performance, intelligent offshore wind-to-hydrogen control systems should be developed. These systems would dynamically adjust electrolyzer operating parameters based on real-time wind power input, thereby achieving higher conversion efficiency and maximizing equipment utilization. In addition, expanding the use of waste heat recovery technologies could enhance overall system efficiency. For example, waste heat generated during hydrogen production could be repurposed for seawater desalination or other auxiliary processes, ultimately lowering the energy consumption per unit of hydrogen produced.

5.3. Technological Innovation in Seawater Utilization

Overcoming the technical bottlenecks of direct seawater electrolysis for hydrogen production is essential. Such progress will require the development of new electrode materials and electrolyzer designs to address the high energy consumption and high cost associated with the seawater desalination process. Notable progress has already been made in this field. In June 2023, the “Dongfu-1” hydrogen production platform, jointly developed by the team of Academician Xie Heping and Dongfang Electric Group, achieved the world’s first medium-scale verification of in situ hydrogen production from non-desalinated seawater using offshore wind power [

42]. Similarly, China’s Fenghai New Energy has adopted an innovative “wind-solar-storage complementary” system, which has reduced desalination costs, controlling the price of desalinated water to approximately 8 yuan per ton (about 1.1 US dollars) [

43]. Globally, the large-scale application of direct seawater utilization technologies needs to be promoted and popularized.

5.4. Improvement of Storage and Transportation Technologies and Facilities

Future efforts should focus on the development of low-cost, high-safety hydrogen storage technologies across multiple pathways. For high-pressure gaseous hydrogen storage, lightweight and high-strength hydrogen storage materials such as carbon fiber composites should be developed to reduce the manufacturing cost and weight of hydrogen storage tanks, while allowing for higher storage pressures and greater hydrogen capacity. For liquid hydrogen storage, the thermal insulation design of storage tanks should be optimized through the adoption of new thermal insulation materials, such as nano-insulation composites, to reduce heat loss and lower energy consumption during liquefaction and storage. For solid-state hydrogen storage, research and development should be accelerated on high-performance hydrogen storage materials, including metal hydrides and chemical hydrides, so that storage density and cycle life can be improved and large-scale application enabled [

44,

45].

In hydrogen transportation, addressing the persistent problem of hydrogen embrittlement is critical. Overcoming this challenge will require the development of hydrogen embrittlement-resistant pipeline materials and optimized design and manufacturing processes to enhance pipeline safety and reliability. Meanwhile, diversified hydrogen transportation methods should be explored, such as hydrogen blending transportation using existing oil and gas pipelines, to reduce infrastructure construction costs and expand delivery options.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides a comprehensive review of offshore wind-to-hydrogen technology, examining its technical routes, engineering practices, economic efficiency, and key challenges. Current global developments reveal a significant trend toward large-scale and base-oriented projects. Europe has more diverse technological explorations, focusing on PEM electrolysis technology and centralized hydrogen production in far-offshore areas. By contrast, China mainly relies on the mature ALK technology, prioritizing onshore hydrogen production from offshore wind power. Although this approach has scale advantages, limitations remain in terms of technological diversity and adaptability to far-offshore areas.

Offshore wind-to-hydrogen technology faces multiple bottlenecks. Electrolysis technologies capable of fully accommodating wind power fluctuations remain immature. Equipment investment, electricity supply, and transmission cables account for a relatively high proportion of project life cycle costs. Furthermore, hydrogen storage and transportation technologies continue to encounter technical challenges, including hydrogen embrittlement in pipelines, high energy consumption in liquid hydrogen storage and transportation, and insufficient large-scale commercialization of solid-state hydrogen storage.

Future developments will depend on advances in three key areas: breakthroughs in core technologies, improvements in system efficiency, and the establishment of a robust industrial ecosystem. Priority directions include the development of wide-load electrolyzers, low-precious-metal catalysts, and corrosion-resistant materials; efficiency improvements through intelligent control systems and waste heat recovery; innovation in direct seawater electrolysis technology; and the practical application of high-pressure, low-temperature, and solid-state hydrogen storage technologies, as well as safer hydrogen pipeline transport. Through collaborative innovation and integrated demonstration in multiple fields, offshore wind-to-hydrogen is expected to move rapidly toward large-scale deployment and commercial application, thereby providing critical support for the realization of a global zero-carbon energy system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J. and B.X.; formal analysis, D.G.; investigation, H.J. and W.C.; resources, H.J. and W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J. and W.C.; writing—review and editing, L.X. and B.X.; visualization, D.G.; project administration, B.X.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feng S, Wang W, Wang Z, Song Z, Yang Q, Wang B. Global wind-power generation capacity in the context of climate change. Engineering, 2024, 51: 86-97. [CrossRef]

- Ji Z, Qin J, Cheng K, Zhang S, Wang Z. A comprehensive evaluation of ducted fan hybrid engines integrated with fuel cells for sustainable aviation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2023, 185, 113567. [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Energy Council, Global Wind Energy Report 2025. Brussels, Belgium: GWEC, 2025.

- Ren G, Liu J, Wan J, Guo Y, Yu D. Overview of wind power intermittency: Impacts, measurements, and mitigation solutions. Applied Energy, 2017, 204: 47-65. [CrossRef]

- He Q, Shen Y. Development status of technology for wind-hydrogen coupled energy storage system. Thermal Power Generation, 2021, 50(08): 9-17.

- Balaji R K, You F. Sailing towards sustainability: offshore wind’s green hydrogen potential for decarbonization in coastal USA[J]. Energy & Environmental Science, 2024, 17(17): 6138-6156.

- Eladl AA, Fawzy S, Abd-Raboh EE, Elmitwally A, Agundis-Tinajero G, Guerrero JM, Hassan MA. A comprehensive review on wind power spillage: Reasons, minimization techniques, real applications, challenges, and future trends. Electric Power Systems Research, 2024, 226, 109915. [CrossRef]

- Schell KR, Claro J, Guikema SD. Probabilistic cost prediction for submarine power cable projects. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 2017, 90: 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Obanor EI, Dirisu JO, Kilanko OO, Salawu EY, Ajayi OO. Progress in green hydrogen adoption in the African context. Frontiers in Energy Research, 2024, 12, 1429118. [CrossRef]

- Tuluhong A, Chang Q, Xie L, Xu Z, Song T. Current status of green hydrogen production technology: A review. Sustainability, 2024, 16(20), 9070. [CrossRef]

- National Energy Administration, China Hydrogen Energy Development Report (2025), National Energy Administration, Beijing, China, 2025.

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Global Green Hydrogen Development Report 2025. IRENA, 2025.

- Li X, Yuan L. Development Status and Suggestions of Offshore Wind Power Hydrogen Production Technology. Power Generation Technology, 2022, 43(02): 198-206.

- Lee J, Choi Y, Che S, Choi M, Chang D. Integrated design evaluation of propulsion, electric power, and re-liquefaction system for large-scale liquefied hydrogen tanker. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2022, 47(6): 4120-4135. [CrossRef]

- People’s Government of Jiangsu Province. (2025, Mar. 13). The 850,000-kilowatt Dafeng Offshore Wind Power Project of Jiangsu Guoxin has fully started construction. [Online]. Jiangsu Provincial People’s Government. Available: https://www.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2025/3/13/art_60085_11515812.html.

- Jilin Electric Power Co., Ltd., Announcement on the investment and construction of the integrated green hydrogen production, storage, transportation, refueling and utilization demonstration project (Phase I) in Yancheng, Shanghai Securities News·China Securities Net, Aug. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://m.10jqka.com.cn/sn/20240828/49029689.shtml.

- Wilberforce T, Olabi AG, Imran M, Sayed ET, Abdelkareem MA. System modelling and performance assessment of green hydrogen production by integrating proton exchange membrane electrolyser with wind turbine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2023, 48(32): 12089-12111. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Ji C, Li R, Song X, Wu K, Yonghong Cheng. Development status of water electrolysis hydrogen production technology and its application progress in the new power system. High Voltage Engineering, 2025, 51(05): 2096-2113.

- Taylor M, Strezov V, Best R, Pettit J, Cho H, Hammerle M, et al. Offshore renewable hydrogen potential in Australia: A techno-economic and legal review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2025, 152, 149923. [CrossRef]

- Oni B A, Sanni S E, Misiani A N. Green hydrogen production in offshore environments: A comprehensive review, current challenges, economics and future-prospects[J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2025, 125: 277-309. [CrossRef]

- Chen R, Yang H, Sun Y, et al. Natural Frequency of Monopile Supported Offshore Wind Turbine Structures Under Long-Term Cyclic Loading [J/OL] 2025, 15(15):10.3390/app15158143. [CrossRef]

- Akpolat A N, Dursun E, Yang Y. Performance Analysis of a PEMFC-Based Grid-Connected Distributed Generation System [J/OL] 2023, 13(6):10.3390/app13063521. [CrossRef]

- Baniamerian Z, Garvey S, Rouse J, et al. Integrated energy storage and transmission solutions: Evaluating hydrogen, ammonia, and compressed air for offshore wind power delivery[J]. Journal of Energy Storage, 2025, 118: 116254. [CrossRef]

- Ligęza K, Łaciak M, Ligęza B. Centralized Offshore Hydrogen Production from Wind Farms in the Baltic Sea Area—A Study Case for Poland [J/OL] 2023, 16(17):10.3390/en16176301. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Xiao X, Li Z, et al. The perspective of offshore wind power: based hydrogen production, hydrogen storage, and hydrogen transportation[J]. Materials Today, 2025, 90: 800-814. [CrossRef]

- Lucas T R, Ferreira A F, Santos Pereira R B, et al. Hydrogen production from the WindFloat Atlantic offshore wind farm: A techno-economic analysis[J]. Applied Energy, 2022, 310: 118481. [CrossRef]

- Franika RV, Ridwan MK, Perdana A. Techno-economic analysis of utilization offshore platform in the java sea to produce hydrogen with offshore wind turbine-based energy sources. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2024, 28(1), 012029-.

- Tahir M M, Abbas A, Dickson R. Green hydrogen and chemical production from solar energy in Pakistan: A geospatial, techno-economic, and environmental assessment[J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2025, 116: 613-626. [CrossRef]

- Calado G, Castro R. Hydrogen production from offshore wind parks: current situation and future perspectives. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2021,11(12), 5561. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan S, Delpisheh M, Convery C, Niblett D, Vinothkannan M, Mamlouk M. Offshore green hydrogen production from wind energy: Critical review and perspective. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 195, 114320. [CrossRef]

- Eniola V, Cimorelli J, Niezrecki C, Willis D, Jin X. Investigating the impact of wind speed variability on optimal sizing of hybrid wind-hydrogen microgrids for reliable power supply. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2025, 106: 834-849. [CrossRef]

- Zheng FY, Yuan BY, Cai YF, Xiang HX, Tang CM, Meng L, et al. Machine learning tailored anodes for efficient hydrogen energy generation in proton-conducting solid oxide electrolysis cells. Nano-Micro Letters, 2025, 17(1), 274. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Wen J, Wang J, Yang B, Jiang L. Water electrolyzer operation scheduling for green hydrogen production: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 203, 114779. [CrossRef]

- China-nengyuan.com, What proportion does the electricity cost account for in hydrogen production by water electrolysis? China Neng Yuan [China Energy Portal], 2021. [Online]. Available: http://www.china-nengyuan.com/baike/6687.html.

- Johnson N, Liebreich M, Kammen DM, Ekins P, McKenna R, Staffell I. Realistic roles for hydrogen in the future energy transition. Nature Reviews Clean Technology, 2025, 1(5): 351-71. [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Rioja A, Puranen P, Järvinen L, Kosonen A, Ruuskanen V, Hynynen K, et al. Baseload hydrogen supply from an off-grid solar PV–wind power–battery–water electrolyzer plant. Energy, 2025, 322, 135304.

- Nicol BC, Bordbar GN, Gianluca V. Assessment of offshore liquid hydrogen production from wind power for ship refueling. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2022, 47(2): 1279-1291.

- Wang X, Cheng T, Hong H, Guo H, Lin X, Yang X, et al. Challenges and opportunities in hydrogen storage and transportation: A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2025, 219, 115881. [CrossRef]

- Shi W, Shen T, Xing C, Sun K, Yan Q, Niu W, et al. Ultrastable supported oxygen evolution electrocatalyst formed by ripening-induced embedding. Science, 2025, 387(6735): 791-796. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz F. Design and performance analysis of hydro and wind-based power and hydrogen generation system for sustainable development. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 2024, 64, 103742. [CrossRef]

- Amirkhalili SA, Zahedi A, Ghaffarinezhad A, Kanani B. Design and evaluation of a hybrid wind/hydrogen/fuel cell energy system for sustainable off-grid power supply. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2025, 100: 1456-1482. [CrossRef]

- Liu T, Zhao Z, Tang W, Chen Y, Lan C, Zhu L, et al. In-situ direct seawater electrolysis using floating platform in ocean with uncontrollable wave motion. Nature Communications, 2024, 15(1), 5305. [CrossRef]

- Lianyungang Municipal Government Office. Lianyungang City Constructs a New Model for Comprehensive Utilization of Seawater: Jiangsu Provincial People’s Government; 2024 [Available from: https://www.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2024/2/6/art_33718_11153306.html.

- Yang M, Hunger R, Berrettoni S, Sprecher B, Wang B. A review of hydrogen storage and transport technologies. Clean Energy, 2023, 7(1): 190-216. [CrossRef]

- Jaber M, Yahya A, Arif AF, Jaber H, Alkhedher M. Burst pressure performance comparison of type V hydrogen tanks: Evaluating various shapes and materials. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2024, 81: 906-917. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).